ABSTRACT

Background:

There are many diverging views regarding the role and purpose of Physical Education (PE) in secondary schools within the UK. However, very few studies have explored PE processes through the eyes of young people. Adolescence represents a critical time period when physical activity (PA) behaviour patterns are often established. Student disengagement in PE is therefore a concern, as PE has the potential to play an important role in influencing adolescents to develop lifelong PA habits. Secondary school PE is compulsory in the UK until the age of 16, therefore PE teachers have a captive audience who they can influence positively or negatively. Understanding of students’ experiences and perceptions of PE could help inform future PE provision.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to explore students’ perceptions of PE throughout secondary school (age 11–16) in England, UK. This study aims to explore students’ views concerning changes and continuities from Key Stage (KS3) (age 11–14) to KS4 (age 14–16). We are also interested in the meanings that students attach to their PE experiences, identifying the social structures and processes that shape these meanings.

Methods:

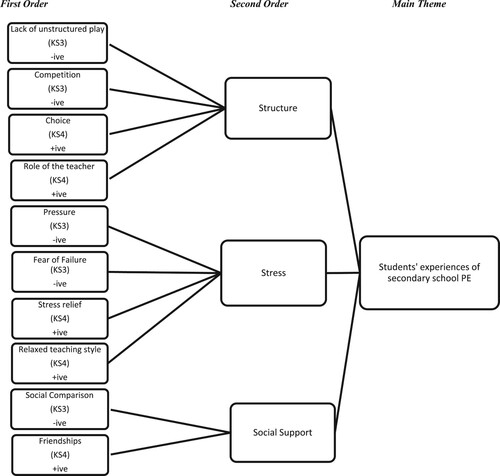

Using a social constructionist framework, semi-structured interviews were conducted at eight secondary schools across Yorkshire, England. A convenience sample of eligible schools was used to recruit the study participants. Two participants aged 15–16 (Year 11, KS4) were interviewed at each school (N = 16). Inductive and deductive thematic analysis informed by self-determination theory guided the analysis. Thematic analysis comprised three second-order themes which were generated by ten first-order themes drawing students’ experiences of PE.

Results:

Perceptions of PE throughout KS3 (age 11–14) were perceived as unfavourable, owing to too much structure and social comparisons. However, perceptions of KS4 (age 14–16) PE lessons were positive, with students enjoying increased choice, less structure, and an opportunity to relieve the stress and pressure of school life. Students identified the role of the teacher to be significant in enhancing student experience throughout secondary school. However, students acknowledged that the student–teacher relationship changed across secondary school, suggesting a need for numerous pedagogical approaches to be adopted through secondary school PE. In addition, PE is recognised by some students as an opportunity to improve their wellbeing, advocating the need for PE teachers to consider employing more holistic outcomes within PE lessons.

Conclusions:

The findings of this study suggest that there is a noticeable difference between students’ experiences of PE at KS3 (age 11–14) compared to KS4 (age 14–16), questioning if the KS3 curriculum is conducive to support student engagement in PE. The results also indicate that PE teachers could widen the learning of PE beyond the physical domain and incorporate a more holistic approach when planning and delivering PE lessons. The long-term implications of engaging more students in PE is that we may inspire more adolescents to remain physically active into adulthood, and to live healthier, more active lives.

Introduction

Worldwide, three in four adolescents (age 11–17) do not meet the global recommendations for Physical Activity (PA) set by WHO (Citation2019). In the UK, Sport England’s Active Lives Survey (Citation2022) data show that only 47% of students at Key Stage 3 (KS3) (age 11–14) and 41% of students at Key Stage 4 (KS4) (age 14–16) meet the recommended daily amount of 60 min of PA set by the World Health Organisation (Citation2019). Secondary school Physical Education (PE) is compulsory in the UK up to the age of 16, therefore effective PE programmes should play a significant part in influencing adolescents to develop lifelong PA habits (Green Citation2020). PE teachers have a captive audience who they can influence positively and negatively, in relation to their desire to be involved in PA throughout their life (Green Citation2020).

Siedentop (Citation1996) has argued for PE to focus on valuing participation in PA. Lifestyle physical activities are developing globally, leading to young people by substituting traditional game activities for recreational lifestyle activities (e.g. gyms, walking, biking) (Kjønniksen, Fjørtoft, and Wold Citation2009). Research suggests that students value PE as a break from ‘normal’ (academic, passive, boring) school lessons, with increased opportunity for informal social interaction (e.g. Lyngstad, Bjerke, and Lagestad Citation2020; Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). Although students recognised the ‘official’ purpose of PE to improve physical health, PE was considered more important in enhancing mental health and well-being due to the academic demands of school (Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). Interestingly, Kjønniksen, Fjørtoft, and Wold (Citation2009) attribute the popularity of PE in Norwegian schools to the more recreational nature (compared with normal academic lessons) and broader content (including recreational outdoor activities, lifestyle activities, and dance, alongside sport). Similarly, in Smith and Parr’s (Citation2007) study, students’ views on the purpose of PE centred on the supposedly non-educational purposes of PE. However, placing too much emphasis on leisure-focused activities, getting students’ outside and moving’, does not necessarily provide meaningful, educational or syllabus-based experiences for students (Morgan and Hansen Citation2008).

PE and the curriculum

PE curricula in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Scotland, and the US have shifted to a focus on holistic development, with increased emphasis on improving health within PE (Cale and Harris Citation2022). Alternatively, the latest version of the English National Curriculum of Physical Education (NCPE) (DfE Citation2014) was driven by sporting values such as competition and performance-based outcomes. With a more health-conscious society, and a new Sport England strategy with an emphasis on health (Sport England Citation2021), there seems to be a slow shift towards a focus on health discourses within PE (Cale and Harris Citation2022; Kirk Citation2019). Some argue that prioritising PA for health rather than sport in PE could be the most effective way to enhance PA levels in young people as well as increase motivation and engagement in PE (Kirk Citation2019; Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020), however, evidence is limited.

The traditional multi-activity-based PE curriculum in England has been criticised because of its limited relevance to students beyond PE lessons (Nabaskues-Lasheras et al. Citation2020). However, teaching approaches such as Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) (Bunker and Thorpe Citation1982), Models Based Practice (MBP) (Metzler Citation2017) and Sport Education (Siedentop Citation1994) have had limited uptake and continue to be usurped by the dominant model (Kirk Citation2010). Green, Smith, and Roberts (Citation2005) argue that the multi-activity, traditional sport-based curriculum in England is in fact effective in promoting lifelong participation and is the best way to cater for young people. It has been suggested that the E in PE, is under attack (Quennerstedt Citation2019). For example, in Australia, outsourcing of PE threatens to de-professionalise PE teachers (Macdonald Citation2014). Countries such as China and the US focus entirely on activity levels within PE, with Macdonald (Citation2014) questioning whether global neo-liberalism is now shaping the future of PE. Fletcher and Ní Chróinín (Citation2022) identified the need for pupils to find meaningfulness in their PE experiences as reports suggest that many children find PE lessons meaningless and irrelevant to their lives (Lodewyk and Pybus Citation2013). Fletcher and Ní Chróinín (Citation2022) concluded that for PE to be meaningful to students, two pedagogical principles should be considered. The first principle involves adopting democratic approaches by allowing students to take ownership of their PE curriculum. Collaboration and consultation with students should provide them with increased autonomy and opportunities to contribute to the planning and delivery of their PE curriculum. Secondly, reflective principles help students to look back at their PE experiences, and identify what makes PE meaningful to them.

Engagement in PE

Disengagement in PE can originate from experiences that are both external and internal to the school context (Bennie et al. Citation2017). It is unusual to hear reports of pre-school age children being unmotivated and disengaged in PE, suggesting students lose interest as they progress through school (e.g. Guzmán and Kingston Citation2012). Increased enjoyment is linked to increased engagement in PE which can be decisive in developing long-term exercise habits (Jekauc and Brand Citation2017). Alongside age, autonomy, competence, and belonging can also predict student enjoyment in PE (Leisterer and Gramlich Citation2021).

Self Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci and Ryan Citation1985) has been frequently used to understand motivation and engagement within PE (e.g. Bennie et al. Citation2017). According to SDT, the mechanism through which individuals move toward more self-determined and intrinsically motivated behaviour is the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan and Deci Citation2019). Lack of autonomy, competence, and relatedness is counterproductive to the aim of increasing PE participation (White et al. Citation2021). Amotivation in PE can be due to too much focus on skill development and competitive sport, leading to student disengagement and fears of inadequacy (e.g. Ntoumanis et al. Citation2004). Noteworthy, White et al. (Citation2021) concluded that students perceive variety, novelty, choice, and praise based on effort can enhance autonomous motivation towards PE. Other studies focused on relatedness and argued that when students are co-constructors of their curriculum, it increased ownership and resulted in increased participation and engagement (e.g. Enright and O’Sullivan Citation2010).

Teachers working in the English education system face pressure from key education stakeholders to adopt a more traditional, controlling style of teaching (Moy, Renshaw, and Davids Citation2014; Reeve Citation2009). Teachers feel under pressure to ensure that their students succeed within a given system even though they may personally disagree with the system (Moore and Clarke Citation2016). Outside influences such as government standards, and parents often place on teachers the burden of responsibility and accountability for student behaviours and outcomes (Reeve Citation2009). When teachers are under pressure to produce particular student outcomes, they tend to pass along that pressure to their students in the form of a controlling motivatinal style (Reeve Citation2009). This controlling style of teaching has been criticised for failing students in PE as it offers less choices and flexibility, leading to boredom and humiliation (Moy, Renshaw, and Davids Citation2014). Leisterer and Gramlich (Citation2021) found PE lessons to be more output focussed as students get older, targeting attainment, and offering more control-based teaching styles, leading to decreased student enjoyment. Likewise, comparisons to more able students could hinder rather than help child engagement as the focus is on external comparisons rather than learning (Barnes and Spray Citation2013).

Aim

Studies examining PE environments have been criticised for their failure to recognise students as experts on their educational experiences (Enright and O’Sullivan Citation2010), with very few studies exploring the PE processes through the eyes of young people (Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). An activist approach was utilised in this study to co-create knowledge alongside students. Activist researchers have listened and responded to young people, to better challenge the status quo in PE Teacher Education (PETE) (Enright and O’Sullivan Citation2010).

The purpose of the present study was to explore students’ experiences of Secondary School PE, examining changes and continuities in perceptions of PE throughout KS3 (age 11–14) and KS4 (age 14–16). We are particularly interested to explore the meanings that participants attach to their PE experiences, identifying the social structures and processes that shape these meanings.

Method

This study adopted a social constructionist framework (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966) to place student voice at the heart of data collection. The lead researcher has 11 years’ experience teaching PE in secondary school and was aware of their role as a co-creator in the data collection process, using abilities, and experiences to communicate with young people in a considerate way (McGrath, Palmgren, and Liljedahl Citation2018). Participants were interviewed in their ‘natural’ setting, in this case a school.

Participants

Study participants were recruited from a convenience sample of eligible schools which included eight PE departments within comprehensive schools in Yorkshire, England.

The lead researcher contacted the teacher in charge of PE at each school via email or telephone, all of whom provisionally agreed to take part. Information sheets and consent forms were distributed via email explaining the aims and objectives of the study. The schools were of a similar size in terms of number of students on roll, ranging from 1323 to 1584 and were all positioned in semi-rural communities. Schools had students from a range of socio-economic status.

A Year 11 non-examination PE class within each school was asked to take part in the study. Prior to data collection, information sheets and consent forms were distributed to the parents and students within this class. The teacher provided the lead researcher with the class register acknowledging those students who had returned both the parent and student consent form. Each student was identified by a number on the register. The lead researcher randomly selected two numbers, one male and one female participant from the class to be interviewed in each school. If the two numbers selected both corresponded with male students for example, another number was chosen until one male and one female had been selected. Asking a class of students for consent ensured that all had equal opportunity to be selected and there were always at least two participants within each school who had gained consent to be interviewed.

Although the interviews were conducted across eight schools, the accounts presented in this paper are representative of only 16 students. It is therefore not intended as a reflection on the general population of Year 11 (age 15–16) students. However, by highlighting perceptions of a small group of students, we intend to contribute to the knowledge of student perceptions of secondary school PE and the influences that can act upon their views.

Data collection

University ethical approval was granted prior to data collection. The research was approved by Sheffield Hallam University ethics board (May 2019, Converis Code ER9818552).

Semi semi-structured interviews were carried out over a 9-week period with 16 Year 11 students (age 15–16). Interviews lasted on average 32 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the lead author to ensure consistency (DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree Citation2006).

The interview schedule was designed to include rapport-building questions, followed by questions focused on participants’ experiences of PE throughout their time at secondary school (McGrath, Palmgren, and Liljedahl Citation2018). For example, participants were asked to recall a typical PE lesson and describe the activity, environment, and any emotions they experienced within those lessons. Participants reflected on PE lessons from Year 7 to Year 11. When students reflected on specific lessons that were memorable to them, they were asked to elaborate on why those lessons were memorable.

Elements of the cognitive interview process (Geiselman et al. Citation1985) were used to enhance memory retrieval as participants reflected on their experiences of school PE throughout the past five years. Memory recall is a concern as participants may experience memory decay when recalling events across a five-year period (Khare and Vedel Citation2019). The accuracy of the information decreases as the recall period increases (Clarke, Fiebig, and Gerdtham Citation2008). However, the method and the knowledge created will always be infused with subjectivities, biases, or distortions (Smith and Sparkes Citation2020). Therefore, participants’ interpretations of those experiences are often precisely what the researcher is interested in (Smith Citation2018). The use of clear and precise questions (Khare and Vedel Citation2019), together with methods to facilitate memory recall by following an ordered sequence of events, starting with the present and thinking back to a point in time, facilitate memory retrieval (Khare and Vedel Citation2019).

The researchers’ knowledge of the existing literature impacted upon the interview process, which included questions focused on choice, autonomy, and relatedness. For example, when participants described having more choice in KS4 PE lessons, they were asked to provide examples of the choices given to them and how this affected their overall experience in PE. Similarly, when participants discussed teachers approaches in PE lessons, they were encouraged to elaborate, providing detail regarding how this affected their perception of PE throughout secondary school. I have presented my research positionality statement in Supplementary File 1.

Data analysis

Individual interviews were transcribed verbatim and over 100 pages of raw data were generated. A computer software package (Nvivo 8) was used to assist with data management, sorting, and retrieval. The lead researcher transcribed the interviews. Thematic analysis was influenced by SDT theory, therefore should be considered inductive and deductive.

Transcripts analysis was undertaken based on the six-phase process outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The first stage involved the lead author familiarising themselves with the transcripts. The raw data were revisited multiple times and significant extracts of the data were initially coded to represent participants experiences of PE. The second stage involved coding and continued until first-order themes were identified and then themes with similar meaning were clustered to form second-order themes.

A peer debriefing session occurred in which another researcher independently performed first-level coding on 50% of the interview data so that discussions could take place regarding the different coded versions of the same data. After peer debriefing, four authors worked together to review the themes and sub themes several times before they were named, defined, and written up. The coding involved continually questioning the assumptions made when interpreting the data. Pseudonyms were also used to represent the personal stories of each participant and to protect their identities (Heaton Citation2022).

Thematic analysis generated three second-order themes, comprising of ten first-order themes outlining factors which influence students’ experiences of PE across KS3 and KS4 (See ). Raw data quotes have been included to ensure authenticity and enhance the context for the reader (Tracy Citation2010).

Results

Overview

The findings were discerned by KS with Year 11 students reflecting separately on their experiences of KS3 and KS4 PE. summarises the hierarchical themes of noticed factors which affect student experiences in secondary school PE. Themes have been labelled as either positive or negative depending on the context in which they were discussed by the participants in this study.

Key stage 3 (KS3) PE

Structure

Participants identified that teachers structured PE lessons differently at KS3 compared to KS4:

In year 7 it was a lot stricter they really encouraged you to participate a lot more

In year 7,8 and 9 you would get told what to do, whereas further up the school, you just choose what you want to do at the start of the week, and they put that on for you. Less structure that’s the word.

In Year 7 I felt a bit like I couldn’t be bothered in PE. The more structured lessons were boring, doing blocks of work on activities you didn’t enjoy.

When the teacher says don’t do that, I get upset, because I want it to be fun. I don’t want to worry about playing it right or wrong to be honest. I just wanted to have fun.

I like netball when its relaxed. When people are shouting at me saying, you’ve stepped twice, I just want to play.

I enjoy playing tennis but when you're stood there and there's a teacher saying well you’ve got to stand like this, hold the racket like this (laughs) you want to just play.

In year 7 probably focus on skills and learning how to play games that you haven't before and then in later years, still using those skills but more relaxed in a way.

In year 7,8 and 9 everyone's just competitive and wanted to win.

It was very competitive when we used to play netball and I'm not a big fan of things being competitive, probably a reason why I don’t play netball anymore.

There’s just too much structure and competitiveness, that’s not fun.

I don’t agree with sets in PE because I think it just promotes the hierarchy within PE and people who are within in the bottom set. So, people in bottom sets feel worse about themselves.

It was only enjoyable because I was in the lower sets. If I was with people much larger and stronger than me, I would have enjoyed it much less.

Stress

For some participants, KS3 PE lessons were a source of stress with the perception of increased pressure:

The team atmosphere, there’s a lot of pressure in that because you kind of feel you’re letting people down which I don’t like.

I haven’t ever skipped PE simply because I didn’t want to get into trouble. But there are occasions where I didn’t want to do PE because I don’t like being put on the spot. It’s the pressure and the embarrassment.

I remember from previous years in school where I was in higher sets for PE and it was more pressure of having to get everything right. That wasn’t an enjoyable thing for me.

I don’t like being judged on my sports. I don’t do it to learn how to do it, I do it to have fun. That’s what PE should be about.

In netball, I get stressed out when the teachers shouting at me for doing incorrect footwork or not shooting correctly. If it’s way too serious then I'm not a huge fan. I like netball when its relaxed.

It was awful being put on the spot. I don’t like the fact that everyone's relying on me, and I feel like I'm letting them down.

I am afraid that other people will look at that and judge me.

It was scary, and it wasn’t the normal kind of PE atmosphere, because you weren't being social. You didn’t have time to speak to others, and you felt like you were on show

My friend was worried about looking silly in front of the class and she said she wasn’t going to take part next time cos it's embarrassing

Social support

Interactions between students in PE lessons affected the overall student experience at KS3:

comparing myself against other people doesn’t help … its constantly setting yourself up for failure in a way cos it's like, I must be better, or I've not done as well.

with things like the bleep test, you don’t want to be the first to go out, so you overstrain yourself to fit in and not be the weak link. It's something we all dreaded.

There's a lot of negativity in PE cos people are in an insecure situation when they’ve got PE kits on. Everyone feels uncomfortable, so it brings a negative aspect to the subject, it's not the subject or what they're learning it’s the situation where everyone feels the need to be compared.

Key stage 4 PE

Structure

Participants interviewed were approaching the end of their KS4 PE experience, therefore reflections of KS4 PE were more detailed and vivid. The structure of PE lessons at KS4 differed greatly to their memories of KS3 PE:

I prefer less structured activities so not learning skills in football, but let's do dodgeball or benchball. It's just a lot simpler, and people exercise the same amount but have more fun with it.

The informality of the lessons. It was loud, chaotic, it was hectic, and everybody was having a good time, even the cool kids. It was much more like something that I would do with my friends outside of school.

when things are less structured there's a lot more socialising and more communication.

They let us do what we want. I like that sense of freedom.

If sir says we're doing football and a group of us say we don’t want to, he will suggest something different so it’s a bit more democratic. We get more choice and the freedom to choose something easier.

At the beginning of the year, the teachers said KS4 lessons would be less structured, and focus on our mental fitness as much as our physical fitness. This will help us stay calm and if you stay healthy it will be more beneficial to your well-being especially in the run up to exams. Having an hour where it’s not as much of a stress.

you’ve got more freedom. It’s the only period you get to relax and do as you please, so lads mainly its football but if you don’t want to do football there's more choices.

Participants reflected on the teaching environment that was created in KS4 PE, with particular focus on the role and influence of the teacher:

Miss always jokes with us, she joins in and it's friendly. They're never about forcing you to do something. It's about giving it a go, you'll get there and keep improving, you don’t feel pressure from them.

They can have fun; You can have a laugh with them and speak to them like a friend as well as a teacher because they're doing sport with you as well.

The most important thing is to have that connection with your teacher. Some of the PE staff join in the lessons and it makes it a lot more fun seeing them take part.

Stress

Many participants described the pressure and stress of school life. Interviews occurred during the GCSE exam period which may have contributed to students perceived levels of stress. Less structured PE lessons at KS4 offered students ‘free’ time that was needed during a particularly stressful period:

I feel like as the academic years have gotten more stressful, then it’s like, oh thank god I've got PE today. There's so much focus on doing well in subjects like Maths, whereas in PE you don’t have any pressure.

There's not any pressure really from the teacher or your friends to try hard, to do great you know. It’s a very relaxed environment.

It's more relaxed because we choose what we want. The teachers say it’s time to take your mind off exams and time to be free.

Social support

KS4 PE allowed more opportunity for students to work with friends, which improved their experience in PE:

It's a nice hour where you can come and do what you want with friends.

It was just a lesson where you can be with your friends and do sport. You look at it as a fun lesson and one you enjoy.

People open more because when things are less structured there's a lot more socialising and more communication.

PE I’m chatting with friends and playing games, but we get to choose. This lesson, we've done Hectics, so it's just fun games with your friends. It was fun working with my friends, but we were still active in the lesson.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore students’ perceptions of PE across a five-year period and to compare Year 11 students’ (age 15–16) perceptions of PE across KS3 and KS4. Findings suggest that the delivery of the KS4 PE curriculum was more desirable to students when compared to the delivery of the KS3 PE curriculum, with teachers playing a pivotal role in influencing student experience in PE.

Research suggests PA levels decline steeply from age 15 (Anderssen, Wold, and Torsheim Citation2005; Kjønniksen, Fjørtoft, and Wold Citation2009), and this decline may cause a corresponding decrease in a positive attitude to PE (Kjønniksen, Fjørtoft, and Wold Citation2009). Another explanation may be the traditional teaching approach adopted by PE teachers at KS3. Participants described a structured, controlling teaching approach, with a focus on skill acquisition, which can contribute to the development of negative perceptions of PE during initial stages of secondary school (Ntoumanis et al. Citation2004). Participants appreciated autonomy supportive teaching styles utilised during KS4 PE lessons, which resulted in more positive attitudes, in line with previous research (Bennie et al. Citation2017; Ulstad et al. Citation2018). Therefore, teachers recognise the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness when planning lessons and designing their PE curriculum to enhance student experience (White et al. Citation2021).

Students understand the importance of enhancing physical health through PE, yet recognise the role of PE in enhancing mental health and well-being, particularly as the academic demands of school increase throughout secondary school. Students reported more enjoyable experiences in PE when their teacher adopted an autonomous teaching style (Jaakkola et al. Citation2015), which could also increase students’ intrinsic motivation (Mitchell, Gray, and Inchley Citation2015).

However, the freedom and choice offered in PE depends on the confidence of PE teachers to adopt a less structured, alternative pedagogical approach across the whole secondary school curriculum. We must also recognise the lack of traditional learning experiences that often occur within this environment. Although enjoyable, are we reaching the educational aspect of ‘Physical Education’? Some argue that this approach does not provide meaningful, educational or syllabus-based experiences for students (Morgan and Hansen Citation2008). However, with a potential shift toward an emphasis on health discourses within PE (Cale and Harris Citation2022; Kirk Citation2019), this study suggests the need to consider a change in how we define ‘Physical Education’ and recognise the value of enhancing PA levels in young people through student engagement that could encompass the whole PE curriculum.

This study highlights the need to listen to students’ beliefs that participation in PE should play a part in improving their health, and enable them to learn sports skills in, rather than through PE (Smith and Parr Citation2007). Fletcher and Ní Chróinín (Citation2022) suggested that democratic approaches should be adopted, allowing students to take ownership of their PE curriculum. It is important for students to have increased autonomy and contribute to the planning and delivery of their PE curriculum. Student voice should also be a priority for all secondary school teachers, encouraging students to reflect on their PE experiences and identify what makes PE meaningful to them (Enright and O’Sullivan Citation2010; Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022).

PE can provide students with opportunities to not only improve their physical health, but also their cognitive, social, and emotional development in a school environment (Bailey et al. Citation2009). There has been growing interest among researchers in developing pedagogies with a focus on mental wellbeing as a response to the prevalence of mental health issues among young people (Cale and Harris Citation2022; Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). In this study, students associated KS3 PE with heightened stress levels, arguing that lessons often included social comparison and increased competition. On the other hand, KS4 students used language such as ‘pressure’ and ‘stress’ when describing school life, showing that a more student-centred teaching approach, with a focus on fun, might increase enjoyment and positive mood in KS4 PE lessons, suggesting an improvement in participants well-being.

KS4 PE lessons were described as a source of stress relief and an opportunity to relax and escape from the pressure of exams (Corr, McSharry, and Murtagh Citation2019). Implementing alternative, less structured pedagogical approaches at KS3 PE may inspire young people to adopt a physically active lifestyle at a younger age, which is crucial in encouraging lifelong participation in PA (Kirk Citation2010). Although this may not be considered ‘Physical Education’ there is a growing consensus that PE has a significant role to play in increasing PA levels of young people, to have a positive impact on their overall health and well-being (Cale and Harris Citation2022).

Not all research supports a move away from an emphasis on physical skill development in PE. Since the Norwegian PE curriculum has increasingly focused on enhancing student wellbeing, students no longer recognise PE as an arena for the acquisition of important skills and knowledge (Lyngstad, Bjerke, and Lagestad Citation2020). PE should not be limited to promoting PA at the expense of skill development. A solution is to develop a more holistic PE curriculum throughout secondary school allowing students to develop their skills and competences, but also encouraging teachers to be creative and innovative when planning and delivering their lessons. Despite evidence of its failure to realise its core aspirations, there are still many teachers who believe that skill acquisition should be the focus of PE programmes (Kirk Citation2010). This may be due to concerns that radical reform of PE could devalue its place within the school curriculum (Kirk Citation2010).

Some students in this study felt self-conscious about their abilities during KS3 PE lessons in comparison to other students. PE can be a site of social comparison, with students being judged by peers and teachers in a highly visible way, having consequences on mental health (Barnes and Spray Citation2013; Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). Teachers should therefore focus on participation as the accomplishment rather than the outcome in PE lessons (Murfay et al. Citation2022). However, in the UK, performative cultures privileging intent practices focused on measurable outcomes, accountability, and heightened surveillance, moving away from liberal and social democratic educational principles and ideals which would allow teachers to focus on participation rather than outcome (Evans Citation2014). Interestingly, social comparison was not discussed in relation to KS4 PE lessons, perhaps due to participants developmental age, or that a more autonomous, democratic learning environment increased students’ self-efficacy.

Participants suggested being more physically active in lessons when participating with friends in KS4 PE lessons. Students consider PE as meaningful when the activities are fun and involve working with friends, cultivating comradeship and social togetherness (Lyngstad, Bjerke, and Lagestad Citation2020). Being physically active for sustained periods of time is one of the four key aims of the NCPE, although it should be recognised that this does not equate to being physically educated. However, it is still important to consider the complex ways in which PE is viewed by the young people for whom it is intended, even if this outcome is not considered to be ‘physical education’ by many (Smith and Parr Citation2007). The most recent PE curriculum provides minimalist guidance on both content and assessment in PE and is accompanied by a significant reduction in assessment guidance (Herold Citation2020).which allows teachers autonomy to modify their curriculum, taking into consideration students’ perspectives of PE (Herold Citation2020).

Strength and limitations

One of the strengths of this study was that students’ perceptions were explored from eight secondary schools in Yorkshire, England, providing a good representation of students’ perspectives, considering factors affecting students’ perceptions of PE based upon the school and the teachers. Although, the transferability is limited (Smith Citation2018), other studies on perceptions of PE have focused on the views of students in only one school (Lyngstad, Bjerke, and Lagestad Citation2020; Murfay et al. Citation2022; Smith and Parr Citation2007). Another strength of the study is the use of thematic analysis informed by SDT theory, therefore both inductive and deductive analysis was carried out. This provided an in-depth qualitative analysis of students’ perspectives.

However, this study also contains some limitations. The current study relies on the participants’ ability to accurately reflect on their past experiences of school PE. A longitudinal study, following students throughout their secondary school PE journey would allow for close monitoring of changes in perceptions of PE in the present rather than retrospectively. However, Smith and Sparkes (Citation2020) acknowledge that in qualitative research, participants’ interpretations of reconstructed accounts of those experiences, are precisely what the researcher is interested in.

Implications for practice and research

The results of this study indicate a distinct difference between student’s experiences of PE at KS3 compared to KS4. Findings also highlight the importance of the teacher’s role in providing a positive student experience in PE.

It is not easy for teachers to change their practice in the current educational climate with increased workloads, disruptive students and stagnant levels of pay resulting in many PE teachers leaving the profession in their first five years of teaching (Lee Citation2019). However, studies have shown increased student engagement and wellbeing when teachers alter their teaching approach across all KS levels (Bennie et al. Citation2017; Ulstad et al. Citation2018). Our research suggests teachers should consider their teaching approaches, to enhance the students’ PE experience during the early stages of secondary school, as well as considering the social structure of their classes, and the relationships they develop with their students, to promote the most positive interactions within PE. KS4 PE offered students more autonomy with a less structured curriculum, which in turn helped students to cope with the stress and pressure of exams. This does not mean that students should experience ‘free play’, solely focused on having fun, as this can result in lack of effort during PE lessons, or avoiding participation altogether (Ntoumanis et al. Citation2004; Quennerstedt Citation2019). However, there is potential for teachers to widen the learning beyond educating students physically, focusing on how PE can improve the emotional well-being of young people in a society where there are considerable issues with regards to adolescent mental health.

The marginalisation of PE within the school curriculum has been a persistent threat throughout the history of state secondary schooling (Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). Whilst there are serious concerns in the UK around the growing mental health crisis of young people, it may be that the best defence for PE becomes physical recreation as an antidote to the academic stress students face in school (Røset, Green, and Thurston Citation2020). However, whilst PE may have a role to play in addressing issues such as mental health or obesity, this should not be the sole purpose for PE (Cale and Harris Citation2022). PE cannot address all young people’s PA and health needs (Evans Citation2014). However, teachers can use the PE time they have to stimulate interest, enjoyment, knowledge, competence and expertise in PA and sport for health and well-being amongst young people.

Concerning future research, this study increased understanding around the changing perceptions of PE in secondary schools, providing a platform for future research to further identify factors affecting students‘ experiences. Clearly, teacher evaluation and continuous consultation is important for engaging students in PE (Mitchell, Gray, and Inchley Citation2015). Exploring teachers’ perspectives is necessary to appreciate the factors which impact upon their ability to deliver the best PE experience for students.

Finally, the role of alternative pedagogical approaches at KS4 should be explored further. For example, Models Based Practice (MBP) has been recognised as an alternative to more traditional, multi-activity-based programmes (Kirk Citation2013). Meaningful PE is also grounded in democratic, student-centred pedagogy (Fletcher and Ní Chróinín Citation2022) where learning occurs as students construct knowledge based upon their personal experiences. There is a need to determine when and why teachers adopt different pedagogical approaches throughout secondary school PE, and the impact this has on student perceptions of PE.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Dr Leighton Jones, Academy of Sport and Physical Activity, Sheffield Hallam University, for his help and guidance throughout the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderssen, Norman, Bente Wold, and Torbjørn Torsheim. 2005. “Tracking of Physical Activity in Adolescence.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 76 (2): 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2005.10599274.

- Bailey, Richard, Kathleen Armour, David Kirk, Mike Jess, Ian Pickup, and Rachel Sandford. 2009. “The Educational Benefits Claimed for Physical Education and School Sport: An Academic Review.” Research Papers in Education 24 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701809817.

- Barnes, Jemima S., and Christopher M. Spray. 2013. “Social Comparison In Physical Education: An Examination Of The Relationship Between Two Frames Of Reference And Engagement, Disaffection, And Physical Self-Concept.” Psychology in the Schools 50 (10): 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21726.

- Bennie, Andrew, Louisa Peralta, Sandra Gibbons, David Lubans, and Richard Rosenkranz. 2017. “Physical Education Teachers’ Perceptions About the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Strategies Used to Increase Relevance and Choice for Students in Physical Education Classes.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45 (3): 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1207059.

- Berger, Peter L, and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Open Road Media.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bunker, David, and Rod Thorpe. 1982. “A Model for the Teaching of Games in Secondary Schools.” Bulletin of Physical Education 18 (1): 5–8.

- Cale, Lorraine, and Jo Harris. 2022. Physical Education Pedagogies for Health. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003225904.

- Clarke, Philip M., Denzil G. Fiebig, and Ulf-G. Gerdtham. 2008. “Optimal Recall Length in Survey Design.” Journal of Health Economics 27 (5): 1275–1284. 012. https://doi-org.libaccess.hud.ac.uk/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.05.

- Corr, Méabh, Jennifer McSharry, and Elaine M. Murtagh. 2019. “Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies.” American Journal of Health Promotion 33 (5): 806–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118818747.

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 1985. “Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior.” Contemporary Sociology 17 (2): 253.

- Department for Education. 2014. “National Curriculum.” GOV.UK. October 14, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-curriculum.

- DiCicco-Bloom, Barbara, and Benjamin F Crabtree. 2006. “The Qualitative Research Interview” Medical Education 40 (4): 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x.

- England Sport. 2021. “Uniting the Movement.” The Five Big Issues—Connecting with Health and Wellbeing.

- England Sport. 2022. “Active Lives Children and Young People Survey, 2020-2021.”.

- Enright, Eimear, and Mary O’Sullivan. 2010. “‘Can I Do It in My Pyjamas?’ Negotiating a Physical Education Curriculum with Teenage Girls.” European Physical Education Review 16 (3): 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X10382967.

- Evans, John. 2014. “Neoliberalism and the Future for a Socio-Educative Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (5): 545–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.817010.

- Fletcher, Tim, and Déirdre Ní Chróinín. 2022. “Pedagogical Principles That Support the Prioritisation of Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education: Conceptual and Practical Considerations.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 27 (5): 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1884672.

- Geiselman, R. Edward, Ronald P. Fisher, David P. MacKinnon, and Heidi L. Holland. 1985. “Eyewitness Memory Enhancement in the Police Interview: Cognitive Retrieval Mnemonics Versus Hypnosis.” Journal of Applied Psychology 70 (2): 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.2.401.

- Green, N. R. 2020, June. “Changing the Focus of Physical Education.” International Journal of Physical Education, Health & Sports Sciences, 43–49. https://pefijournal.org/index.php/ijpehss/article/view/8.

- Green, K. E. N., Andy Smith, and Ken Roberts. 2005. “Young People and Lifelong Participation in Sport and Physical Activity: A Sociological Perspective on Contemporary Physical Education Programmes in England and Wales.” Leisure Studies 24 (1): 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436042000231637.

- Guzmán, Jose Francisco, and Kieran Kingston. 2012. “Prospective Study of Sport Dropout: A Motivational Analysis as a Function of Age and Gender.” European Journal of Sport Science 12 (5): 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.573002.

- Heaton, Janet. 2022. ““*Pseudonyms Are Used Throughout”: A Footnote, Unpacked.” Qualitative Inquiry 28 (1): 123. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211048379.

- Herold, Frank. 2020. “‘There is New Wording, but there is no Real Change in What We Deliver’: Implementing the New National Curriculum for Physical Education in England.” European Physical Education Review 26 (4): 920–937. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19892649.

- Jaakkola, Timo, Sami Yli-Piipari, Vassilis Barkoukis, and Jarmo Liukkonen. 2015. “Relationships among Perceived Motivational Climate, Motivational Regulations, Enjoyment, and PA Participation among Finnish Physical Education Students.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 15 (3): 273–290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1100209.

- Jekauc, Darko, and Ralf Brand. 2017 July. “Editorial: How Do Emotions and Feelings Regulate Physical Activity?” Frontiers in Psychology 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01145.

- Khare, Satya Rashi, and Isabelle Vedel. 2019. “Recall Bias and Reduction Measures: An Example in Primary Health Care Service Utilization.” Family Practice 36 (5): 672–676. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz042.

- Kirk, David. 2010. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874622.

- Kirk, David. 2013. “Educational Value and Models-Based Practice in Physical Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (9): 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.785352.

- Kirk, David. 2019. “Precarity, Critical Pedagogy and Physical Education,” September. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429326301.

- Kjønniksen, Lise, Ingunn Fjørtoft, and Bente Wold. 2009. “Attitude to Physical Education and Participation in Organized Youth Sports During Adolescence Related to Physical Activity in Young Adulthood: A 10-Year Longitudinal Study.” European Physical Education Review 15 (2): 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X09345231.

- Lee, Ye Hoon. 2019. “Emotional Labor, Teacher Burnout, and Turnover Intention in High-School Physical Education Teaching.” European Physical Education Review 25 (1): 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17719559.

- Leisterer, Sascha, and Leonie Gramlich. 2021. “Having a Positive Relationship to Physical Activity: Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Age as Predictors for Students’ Enjoyment in Physical Education.” Sports 9 (7): 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports9070090.

- Lodewyk, Ken R., and Colin M. Pybus. 2013. “Investigating Factors in the Retention of Students in High School Physical Education.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 32 (1): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.32.1.61.

- Lyngstad, Idar, Øyvind Bjerke, and Pål Lagestad. 2020. “Students’ Views on the Purpose of Physical Education in Upper Secondary School. Physical Education as a Break in Everyday School Life – Learning or Just fun?” Sport, Education and Society 25 (2): 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1573421.

- Macdonald, Doune. 2014. “Is Global Neo-Liberalism Shaping the Future of Physical Education?” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (5): 494–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.920496.

- McGrath, Cormac, Per J. Palmgren, and Matilda Liljedahl. 2018. “Twelve Tips for Conducting Qualitative Research Interviews.” Medical Teacher 41 (9): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149.

- Metzler, Michael. 2017. Instructional Models for Physical Education. 3rd ed. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315213521

- Mitchell, Fiona, Shirley Gray, and Jo Inchley. 2015. “‘This Choice Thing Really Works … ’ Changes in Experiences and Engagement of Adolescent Girls in Physical Education Classes, During a School-Based Physical Activity Programme.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 20 (6): 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.837433.

- Moore, Alex, and Matthew Clarke. 2016. “‘Cruel Optimism’: Teacher Attachment to Professionalism in an era of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (5): 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1160293.

- Morgan, Philip J., and Vibeke Hansen. 2008. “Classroom Teachers’ Perceptions of the Impact of Barriers to Teaching Physical Education on the Quality of Physical Education Programs.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 79 (4): 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2008.10599517.

- Moy, Brendan, Ian Renshaw, and Keith Davids. 2014. “Variations in Acculturation and Australian Physical Education Teacher Education Students’ Receptiveness to an Alternative Pedagogical Approach to Games Teaching.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (4): 349–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.780591.

- Murfay, Ken, Aaron Beighle, Heather Erwin, and Erin Aiello. 2022, January. “Examining High School Student Perceptions of Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review. 1356336X2110728. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X211072860.

- Nabaskues-Lasheras, Itsaso, Oidui Usabiaga, Lorena Lozano-Sufrategui, Kevin J Drew, and Øyvind Førland Standal. 2020. “Sociocultural Processes of Ability in Physical Education and Physical Education Teacher Education: A Systematic Review.” European Physical Education Review 26 (4): 865–884. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19891752.

- Ntoumanis, Nikos, Anne-Marte Pensgaard, Chris Martin, and Katie Pipe. 2004. “An Idiographic Analysis of Amotivation in Compulsory School Physical Education.” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 26 (2): 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.26.2.197.

- Quennerstedt, Mikael. 2019. “Physical Education and the Art of Teaching: Transformative Learning and Teaching in Physical Education and Sports Pedagogy.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (6): 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731.

- Reeve, Johnmarshall. 2009. “Why Teachers Adopt a Controlling Motivating Style Toward Students and How They Can Become More Autonomy Supportive.” Educational Psychologist 44 (3): 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990.

- Røset, Linda, Ken Green, and Miranda Thurston. 2020. “Norwegian Youngsters’ Perceptions of Physical Education: Exploring the Implications for Mental Health.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (6): 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1634043.

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2019. “Research on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation is Alive, Well, and Reshaping 21st-Century Management Approaches: Brief Reply to Locke and Schattke (2019).” Motivation Science 5 (4): 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000128.

- Siedentop, D. 1994. Sport Education: Quality P. E. Through Positive Sport Experiences. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Siedentop, Daryl. 1996. “Valuing the Physically Active Life: Contemporary and Future Directions.” Quest (grand Rapids, Mich ) 48 (3): 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1996.10484196.

- Smith, Brett. 2018. “Generalizability in Qualitative Research: Misunderstandings, Opportunities and Recommendations for the Sport and Exercise Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221.

- Smith, Andy, and Michael Parr. 2007. “Young People’s Views on the Nature and Purposes of Physical Education: A Sociological Analysis.” Sport, Education and Society 12 (1): 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320601081526.

- Smith, Brett, and Andrew C. Sparkes. 2020. “Handbook of Sport Psychology.” Handbook of Sport Psychology, April, 999–1019. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119568124.ch49.

- Tracy, Sarah J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (10): 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121.

- Ulstad, Svein Olav, Hallgeir Halvari, Øystein Sørebø, and Edward L. Deci. 2018. “Motivational Predictors of Learning Strategies, Participation, Exertion, and Performance in Physical Education: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Motivation and Emotion 42 (4): 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9694-2.

- White, Rhiannon Lee, Andrew Bennie, Diego Vasconcellos, Renata Cinelli, Toni Hilland, Katherine B. Owen, and Chris Lonsdale. 2021 March. “Self-Determination Theory in Physical Education: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies.” Teaching and Teacher Education 99: 103247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103247.

- World Health Organization. 2019. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. Geneva: World Health Organization.