ABSTRACT

Background

Research in teacher education practice explicitly highlights how learning to teach teachers is a complex, messy, sophisticated process, filled with uncertainty and perpetual challenges. While this applies to all aspects of teacher education, we focus here on the process of learning to teach pre-service teachers (PSTs) how to teach about, through, and for social justice (pedagogies) by enacting the Socially-Just Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (SJ-TPSR) approach.

Purpose

This research was guided by the following research question: What are the realities of enacting a SJ-TPSR approach in physical education teacher education (PETE)?

Method

Utilising a collaborative self-study approach two physical education teacher educators, supported by two critical friends, enacted the SJ-TPSR approach in a 10-week outdoor and adventure activities module with pre-service generalist primary school teachers. Data included: critical friend meetings, pedagogical decision-making documents and interviews with the teacher educators and PSTs.

Findings

The findings revolve around three categories: (i) Teaching about teaching and learning about teaching the SJ-TPSR approach; (ii) The importance of learning together; and (iii) A pedagogy of vulnerability needed? The findings demonstrated the need to take a gradual approach to teaching about teaching the SJ-TPSR approach and learning about teaching along with the SJ-TPSR approach. It was a daunting experience but reflection and sharing our thoughts mitigated most of these feelings. The importance of learning together was highlighted by both teacher educators. Co-constructing this new knowledge with the PSTs further supported this process. Finally, when enacting a new pedagogical approach, particularly in the area of social justice, required an additional pedagogical approach that of vulnerability.

Discussion

Our collaborative self-study on the enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach is an explicit example of reframing pedagogy and practice not only from a social change and social justice perspective, but about, through, and for social justice and change. We first reconceptualised the TPSR approach to the SJ-TPSR approach from a social justice perspective, but then examined our practice and developed practices that also support the teaching and learning about, through, and for social justice. The practices developed have implications for the enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach which hold possibilities for other innovative practices (e.g. layering), and also for self-study research, namely ways in which collaborative self-study can be conducted and in which self-study can work from a social change and social justice perspective

Conclusion

We trust that sharing our journey thus far will support others interested in enacting the SJ-TPSR approach, and that we, in turn, can learn from others enacting, examining, and articulating their experiences with the approach.

Introduction

Research in teacher education practice explicitly highlights how learning to teach teachers is a complex, messy, sophisticated process, filled with uncertainty and perpetual challenges (e.g. Berry Citation2007; Loughran Citation2006). While this applies to all aspects of teacher education, we focus here on the process of learning to teach pre-service teachers (PSTs) how to teach about, through, and for social justice (pedagogies). Research has alluded to the challenges faced by teacher educators attempting to teach critical/social justice pedagogical approaches (e.g. Flory and Walton-Fisette Citation2015; Shelley and McCuaig Citation2018). These challenges may stem from a possible disconnect between socio-cultural research (e.g. social justice) and pedagogical research (e.g. teacher education practices) (Marttinen Citation2021). Hickey, Mooney, and Alfrey (Citation2022, 4) supported this perspective arguing ‘the ongoing concern that despite rich critical scholarship that advocates [social justice] approaches, the translation into practice in school [or teacher education] is both complex and challenging’. While we feel uncomfortable providing a definition of social justice as language is not static, we are informed by the work of Paulo Freire in how we are approaching social justice. Freire’s (Citation1978) pedagogy centres on achieving social justice through liberation of the oppressed. Throughout this paper we return to Freire and the use of his concepts (e.g. dialogue) in the enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach. There have been calls within the field of teacher education (e.g. Cochran-Smith, Gleeson and Mitchell Citation2010; Mills and Ballantyne Citation2016) and more specifically, in physical education and sport pedagogy (e.g. Kirk Citation1986; Tinning Citation1991; Wright Citation1995), for social justice work. More recently, there has been growing research in the pedagogies of social justice (e.g. Luguetti, Kirk, and Oliver Citation2019; Lynch, Walton-Fisette, and Luguetti Citation2022). Despite this, there continue to be challenges with enactment in school settings (Gerdin et al. Citation2021) and in PETE (Flory and Walton-Fisette Citation2015). These enactment challenges are more evident in the physical spaces of physical education (Gerdin et al. Citation2021). The SJ-TPSR approach provides a promising means of addressing these challenges as it is designed for implementation in the physical spaces of physical education (building on Hellison’s work).

In an attempt to conceptualise the how of teaching about, through, and for social justice, we previously published a theoretical vision of a Socially-Just Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (SJ-TPSR) approach in Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). The purpose of this research was to enact that theoretical conceptualisation. As such, the research question was: What are the realities of enacting a SJ-TPSR approach in physical education teacher education (PETE)? We adopted self-study methodology to explore if a theoretical vision (i.e. the SJ-TPSR approach) could support the processes of teaching the teaching of social justice in PETE. Before delving into the methodology of the research, we outline the SJ-TPSR approach and discuss our guiding theoretical framework (Loughran Citation2006).

The socially-just TPSR approach

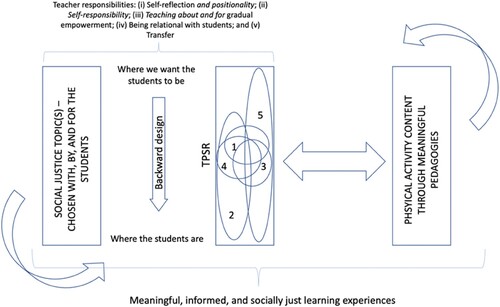

There have been calls for a blending of ‘pedagogical research’ (e.g. PETE practices) and ‘socio-cultural research’ (e.g. social justice) (Flory and Landi Citation2020; Marttinen Citation2021). We label this blending the ‘how’ of social justice. In responding to the ‘how’ question, and a demand to translate (critical pedagogical) vision into practice (Gore Citation1998; Shelley and McCuaig Citation2018), we first reconceptualised TPSR with a social justice lens – the SJ-TPSR (see ). Hellison’s TPSR work (Citation2011) focused on developing personal and social responsibility (and the teaching of such), but the focus was not explicitly on social justice. Authors (e.g. Kirk Citation2019; Casey and Kirk Citation2020) have commented on how TPSR could be viewed as a form of critical pedagogy and acknowledge how TPSR could be viewed as a contribution to social justice pedagogy. We acknowledge this relationship, but also saw the potential to bring social justice explicitly to the forefront through re-developing/re-imagining the TPSR model. This newly developed approach – socially just TPSR (SJ-TPSR) – adds socially just perspectives to the original model. Those being, for example, challenging the notion of the ‘levels’. From a social justice perspective, these needed to be reconceptualised as they can be seen (and enacted) as a hierarchical structure whereby students need to ‘pass’ a level before proceeding to the next. As such, some students may be in more powerful positions than others which creates a power issue. We previously argue ‘that hierarchical levels can cause such intangible divisions and, in some cases, tangible divisions depending on the use of the levels … [for example,] as a behaviour management tool’ (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). This power issue may also relate to the students’ privileges. In other words, students may be on a certain level (a power position) due to their position of privilege: ‘An example of this may be a student who comes from a family who have the means to pay for them to take part in multiple sports and physical activities (see Wheeler, Green, and Thurston Citation2019). This student’s privilege is associated with socio-economic status and the possible benefits/opportunities this affords them to learn how to be respectful for the rights and feelings of others (level 1), self-motivated (level 2), and self-directed (level 3) in physical activity spaces and contexts. The student then brings this privilege (e.g. increased physical capital and socialising experiences) – linked to socio-economic status – into the physical education class which provides that student with an advantage’ (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). We further argue that the static, linear-progression-oriented nature of the levels does not capture the complexity of teaching and learning. The SJ-TPSR spaces overlap whereby students can start in different (and multiple) spaces and move between spaces throughout the lesson. For more information on this reconceptualisation, please see Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill (Citation2022).

We have also added social justice responsibilities to teacher responsibilities. We, and other social justice researchers, strongly suggest the need for self-reflection on positionality with regards to the social justice matter at hand. This process – positionality work – has now been included in the SJ-TPSR teacher responsibilities. In addition to this, we have added ‘self-responsibility’ which means ‘not only having the ability to respond, but a commitment to engage in educating yourself on the situations that need a response’ (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). Finally, we added in ‘teaching about and for’ to Hellison’s (Citation2011) gradual empowerment. While we agree with Hellison’s intention here, we further argue the need to ‘teach students about empowerment and providing/co-creating spaces whereby students have the opportunity to be empowered’ (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). Overall, Hellison advocated for re-developing TPSR in light of the needs of young people (and society). We are honouring Hellison’s wishes with the SJ-TPSR asking ‘What’s worth doing?’ and ‘Is it working?’ (Hellison Citation2011).

While a detailed account of the theoretical development of a SJ-TPSR approach was published (please see Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022), we briefly outline the three key strands of the approach:

In looking at (a visual representation of our vision for practice), starting on the left-hand side, the first strand is the social justice matter(s) (e.g. privilege and oppression, see Lynch, Walton-Fisette and Luguetti Citation2022), in other words, social injustices. This is chosen based on learners’ interest and needs as well as the context of the teaching and learning. We emphasise the need to value students as partners, in this case, by negotiating the social justice matter with, by, and for the students. This is supported by Walton-Fisette, Sutherland, and Hill’s (Citation2019, 2) suggestion, ‘Pedagogies for social justice must be tailored to fit the setting’.

As we move to the middle strand of the figure, the TPSR levels have been reconceptualised from a hierarchical depiction, which might give the impression of needing to pass one level before gaining access to another and which also places learners above and below one another, to spaces that acknowledge the complexity and fluidity of being (e.g. moving in, out, and across spaces). We have alluded to justifications for this above.

The right-hand strand is the physical activity content. Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill (Citation2022) suggest the SJ-TPSR approach can act as an underpinning pedagogy to practise that also leaves open possibilities for integrating other meaningful pedagogies that support the physical activity content; for example, this research in the context of a module based in an Outdoor and Adventure Activities approach which is also underpinned in a pedagogy of the SJ-TPSR approach.

One other notable piece of the reconceptualization is teacher responsibilities which include social justice concepts such as positionality, gradual empowerment, and transfer in the form of advocacy. The arrows at the top and bottom are a reminder that constant reflection is required to continue to develop and articulate this approach. The alignment of the strands – the social justice topic/matter chosen with, by, and for the learners and approached through backward design (i.e. assessing where we want to be and designing ways to get there); the five spaces rather than levels; and the physical activity content through meaningful pedagogies – might therefore lead to meaningful, informed, and socially-just learning experiences.

One of the many features of TPSR that remains in the SJ-TPSR approach is the five-part lesson plan (Hellison Citation2011) – or what we refer to as learning plan so that learning is prioritised, not the lesson (Baker Citation2020). As discussed in Baker et al. (Citation2023), the five-part learning plan offers an entry point for educators to begin their SJ-TPSR journey. Guidance, such as beginning class by chatting one-on-one or with small groups of learners to purposefully nurture strong(er) bonds (i.e. Relational Time), is an essential part of a learning plan with both the TPSR and SJ-TPSR approaches. With an SJ-TSPR approach, the second part of the learning plan, the Awareness Talk, differs slightly from the original. Rather than focusing the Awareness Talk on personal and social responsibility, an SJ-TPSR approach is an opportunity to highlight the social justice matter that will be the focus of the learning while also inviting learner input. As with the original approach, most of the learning time in an SJ-TPSR learning plan is through Physical Activity (part 3). With a SJ-TPSR approach, however, the learning of about, through, and for social justice. For example, physical activity time should be used to shift the power to the learners, perhaps by challenging groups to examine what inclusion (vs exclusion), accessibility, and ‘isms’ look like, sound like, and feel like in activity spaces such as physical education class, the playground, and community recreation areas (see Baker et al. (Citation2023) for elaboration and more practical examples). The last two parts of both a TPSR and SJ-TPSR learning plan are reflections – one group and one individual. In the SJ-TPSR approach, the group meeting offers the opportunity to discuss and share opinions on the social justice topic broadly or in relation to physical activity. The Individual Reflection is a time for introspection about personal attitudes and behaviours toward the social justice topic and how these apply to interactions in other areas of the school, in the community, and personal lives.

It is worth remembering that while the SJ-TPSR approach is built on from the TPSR model, it is not a model; it is an approach to teaching and learning social justice. Therefore, it is not constrained or limited to the boundaries of a pedagogical model. Referring to Metzler’s (Citation2017) understanding of models as blueprints, Landi, Fitzpatrick and McGlashan (Citation2016) critique this conceptualisation as the teacher who enacts the model ‘reproduce[s] particular benchmarks that have been previously designed without knowledge of the school, students, or context’ (402). Landi, Fitzpatrick and McGlashan (Citation2016) continue to discuss how models may position students ‘as individuals incapable of knowing’ (402) given their outcomes are already determined through the model. Given how social justice work in contextual, the SJ-TPSR approach accommodates for these critiques as it positions students at the centre of the teaching and learning process, and encourages the teacher to work with and learn from the students in terms of social justice matters (and which reflect their needs): ‘This reconceptualisation of TPSR allows for this input so that the approach is designed around the students (and their culture, needs, and situations)’ (Scanlon, Baker, and Tannehill Citation2022). The teacher who enacts the SJ-TPSR approach and has designed the approach in consultation with the students, will have a different enactment to another teacher in a different context; context matters. Therefore, the SJ-TPSR approach can be used to teach about different and multiple social justice matters (especially if relevant to the students’ lives), i.e. social injustices, and this, therefore, offers a social justice aligned approach to the field. We are guided by Landi, Fitzpatrick and McGlashan (Citation2016) advice here: ‘Models then need to be adopted in physical education programs with care and with a thought for context … If models are employed, then aspects can be altered and contextualized within a wider program and within a broader sociocultural framework’ (408). In saying all of this, we are not advocating SJ-TPSR as the best (or only) way to teach for social justice in physical education; this is one way of doing so which may be further redeveloped through practitioner research.

Translating vision into practice

Hill et al. (Citation2022), whose research explored how PETE and sport pedagogy educators develop social justice knowledges and beliefs, suggest the need for teacher educator’s professional development that shifts an acknowledgement of social justice matters to a change in pedagogical practice. The authors also acknowledge the complexity of this move as ‘Knowledge of the content and pedagogies … does not automatically make someone believe in the value of that knowledge and enact it’ (10). As a way to translate vision into practice, we were guided by self-study as a methodology for examining professional practice (see LaBoskey Citation2004; Pinnegar Citation1998) and for its ‘great compatibility’ with ‘social justice teacher education’ (LaBoskey Citation2009, 81). Therefore, there needs to be a development of a pedagogy of teacher education to inform the teaching of teaching social justice. This encompasses values and beliefs which addresses Hill et al. (Citation2022) concerns.

Developing a pedagogy of teacher education

Theorising practice and translating that into the ‘how’ of teaching are essential elements of teaching about teaching (Loughran Citation2006). Teacher educators, as teachers of teachers, should prioritise the development of knowledge of practice given its potential contributions to the improved quality of teaching about teaching not only for oneself, but for PSTs learning about teaching (Crowe and Berry Citation2007). A pedagogy of teacher education has been interpreted by many (e.g. Crowe and Berry Citation2007; Loughran Citation2006; Russell and Loughran Citation2007) as teacher educators engaged in expertly conceptualising and enacting theoretical and practical knowledge of the relationship between teaching about teaching, teaching about learning, and learning about teaching (Loughran Citation2014). As such, a pedagogy of teacher education offers a supportive framework for examining teacher educator practice, in our case, the enactment of an SJ-TPSR approach in PETE.

Methodology

We adopted a collaborative self-study of teacher education practice approach (e.g. Fletcher and Hordvik Citation2023) to this research. This approach to self-study aligns with LaBoskey’s (Citation2004) characteristics of quality self-study as being (a) self-initiated, (b) focused on improvement, (c) drawing on multiple forms of qualitative data, and (d) validity achieved through trustworthiness. However, with a collaborative approach, (e) interactivity, is strengthened by including multiple lenses though which to interrogate teaching about teaching and learning about teaching, as well as to interpret the data. Approaching this research through a collaborative self-study approach is also appropriate given Casey and Kirk (Citation2020, 31) advising that ‘the process of developing new prototype pedagogical models needs to be done in partnership, ideally as a collaborative process between researchers, curriculum developers, school practitioners and learners'.

Context of research

The research took place over 12 weeks (10 weeks of teaching and two weeks of pre- and post-meetings) in an Outdoor and Adventure Activities (OAA) module on a four-year undergraduate primary teacher education programme. The OAA module is a module on the Bachelor of Education (Primary/Elementary Teaching) programme. It is a 5 ECTS credit module undertaken pre-service teachers in Year 3 as part of a primary physical education option. Teaching personal and social responsibility, underpins all work in the module since its inception. The theory of outdoor and adventure education is explained and illustrated as students engage in activities related to the primary curriculum (DES Citation1999). Walking activities, outdoor challenges and orienteering provide the medium for exploration of the adventure philosophy including risk, challenge, problem solving, cooperation, debriefing (reflective practice) and trust. Students work collaboratively to plan lessons that can be implemented in a school setting and those that are undertaken off-site in natural environments. To clarify, OAA was the medium in which the SJ-TPSR was enacted; the self-study was enacting the SJ-TPSR approach and learning about, through, and for social justice through the medium of OAA. The social justice matters are not constrained to OAA, they transcend forms of movement and as such, this approach could be used as an underpinning pedagogy in any movement context. It is important to note that in [name of country] primary teachers are educated as generalist educators. The physical education specialism, of which OAA is one of five modules, is only available to 25–30 PSTs each year from a cohort of 450. Dylan and Maura co-taught the module. All 26 PSTs from this module were invited to participate in focus group interviews; three accepted the invitation. We acknowledge this as a limitation, which may have been due in part to interviews being conducted after the completion of the course (in line with ethical guidelines) which was also the completion of the academic year for this cohort.

Participants

Our community of learners consisted of four teacher educators who ranged from experienced to early career academics. Dylan and Maura were the teacher educators enacting the approach and Kellie and Deborah were critical friends. PSTs also contributed to what was learned about enacting the SJ-TPSR approach, and as such may be considered critical contributors (Baker Citation2021). LaBoskey (Citation2004) suggests that viewing a situation from one perspective in self-study is not sufficient. MacPhail, Tannehill, and Ataman (Citation2021, 14) acknowledge how critical friends can challenge a person’s thinking, reasoning, and ideas and that critical friends have three defining characteristics, ‘a reciprocal collaborative relationship, a willingness to be challenged, and an intrinsically motivated willingness to engage in the relationship’. Both Kellie and Deborah were experienced with TPSR and the implementation of curriculum and instructional models and as such, were deemed suitable critical friends who could advance the enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach. To provide the reader with an understanding of our teaching philosophies or ‘lens’, we share our positionality statements:

Growing up as part of the LGBTQ+ community and in a lower middle-class family, I have always had an interest in advocating for minority groups and differing perspectives With regards to teacher education and social justice, I am particularly interested in how we as teacher educators can teach pre-service teachers to teach social justice in health and physical education. As such, I look to co-create (pedagogical) spaces whereby we can educate each other (PSTs and teacher educators) on social justice matters, integrate social justice principles, and advocate for a more just and equitable society.

Having a sister who has special needs and being aware of her educational experiences growing up (very limited) and sporting experiences (Special Olympics opened a whole new world for her) I was engaging in social justice issues before I knew what they were. As an international rugby player I experienced social justice issues such as gender equity and class. These experiences coupled with the variety of experiences my PSTs were having, and sharing with me, on professional placements made me consider how I could teach for, through and about SJ in my physical education lectures. I wanted to be able to support them and the children in their care and educate for a more equitable society. I chose O&AA to explore this concept as it was a module, I teach each year and is underpinned by TPSR. O&AA content matter and research is something I am very comfortable with, therefore I felt this would be the best starting point for my engagement with this new SJ-TPSR approach.

What I currently know and understand about (a) my position in society and the power and privilege I am therefore afforded, and (b) the intent of positionality statements, is evolving. I therefore offer this positionality statement as it pertains to my role in this research – that of critical friend in supporting the development of an approach with possibilities and opportunities of explicitly teaching about, through, and for social justice. My interest in social justice has its foundations in my experiences as a young female who consciously used my voice (and unconsciously used my body) to carve a space for myself in male-dominated 1970s and 80’s sport. These experiences, and my position within society at various points in my life (e.g. 1970s lower socio-economic status to 2020s upper end of ‘middle-class’, university educated, white/euro-Canadian, bilingual, heterosexual, able-bodied, female, athlete) have further contributed to my interest in, and notion(s) of social justice. As a newly minted PhD who had been enacting a TPSR approach in HPE K-12 and tertiary contexts for close to three decades, the opportunity to collaboratively engage with colleagues in reconceptualizing TPSR through a social justice lens, and the possibilities this offered with respect to supporting educators (i.e. in-service and pre-service, and teacher educators), and their students, in learning about, through, and for social justice, has been one of the greatest challenges and joys of my career.

Deborah is an experienced teacher educator who is passionate about teaching and teacher education. Deborah has worked on many research projects which encapsulated social justice, for example, the Urban School Group project (Tannehill and Murphy Citation2012). Author’s journey to becoming a teacher educator is beautifully captured in this reflective piece, the British Educational Research Association (BERA) 2013 Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy Special Interest Group (SIG) Lecture (Tannehill Citation2016).

In considering the simultaneous power relationship and the degree of mutual connections, roles and behaviours captured by interrogating the role of the critical friend, the differences between the coach, mentor and critical friend become evident. As a reminder, mentoring tends to be contractual and nominally arranged on behalf of an institute. Critical friend relationships tend to arise from personal approaches or requests and/or grown from a professional friendship. (p.12)

We also acknowledge the power inbalance between the teacher educators and PSTs. In line with granted ethical approval, we took steps to reduce this power inbalance. For example, focus groups were on a volunteer basis and were conducted after all assessments had been submitted and returned with grades and feedback. In our teaching and enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach, we shared our vulnerabilities (which will be discussed later on in the findings) to create a more dialogical teacher-student relationship. This was informed by Paulo Freire’s (Citation1978) concept of dialogue:

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers … The teacher is no longer merely the one who teaches, but one who is … taught in dialogue with the students, who in their turn while being taught also teach. (53)

Data collection

The data collection included: (i) Four critical friend meetings (fortnightly during teaching term) (CFM); (ii) A pedagogical decision-making document (PDMD) which captured Dylan and Maura’s process of pedagogical decisions; (iii) A teacher educator focus group that was conducted by a third party (FG); and (iv) Two PST’ interviews (PST interviews). All critical friend meetings and interviews were conducted online over Zoom and recorded.

Data analysis

The first three authors independently coded the recorded critical friend meetings and the focus groups. This occurred through ‘initial coding’ (Charmaz Citation2014). During this phase, we also adopted a collaborative ‘live’ coding process. ‘Live’ coding (Parameswaran, Ozawa-Kirk, and Latendresse Citation2020), is done through watching, listening, and coding the recordings. Parameswaran, Ozawa-Kirk, and Latendresse (Citation2020, 641) acknowledge how ‘hearing the voice of the participant brings aspects of emotion, intent, and context that offers life that is otherwise lost on paper’. This approach proves particularly useful for focus groups (Parameswaran, Ozawa-Kirk, and Latendresse Citation2020) and critical friends’ meetings which are unstructured and difficult to translate into text. The second phase of coding was ‘focused coding’. The first three authors met to have a collaborative coding meeting whereby they shared their initial codes. We noted similarities, differences, and common messages across the three sets of coding. We collapsed and amalgamated initial codes to create more focused codes. This was a more collaborative, selective, and conceptual process than initial coding (Mordal-Moen and Green Citation2014). In the final phase of coding, ‘theoretical coding’, the first three authors met again to collaboratively construct categories and subcategories and to make sense of the data using the framework of Loughran’s (Citation2006) pedagogy of teacher education with a particular focus on teaching about teaching and learning about teaching. This process involved more regular meetings whereby we could agree, disagree, clarify, and come to a consensus in the data construction. As a result of this data analysis, three categories were constructed which we will outline and discuss.

Findings

Category 1: Teaching about teaching and learning about teaching the socially-just TPSR approach

Teacher educators must learn to simultaneously manage teaching PSTs about teaching while supporting PSTs in learning about teaching (as both learners and future teachers) (Loughran Citation2006). An added layer of complexity arises when the approach is unfamiliar (i.e. the SJ-TPSR approach). In the next two sub-sections we describe ways in which Dylan and Maura’s attempts to integrate the SJ-TPSR approach in OAA brought rise to feelings of uncertainty for them as well as for PSTs, and how these feelings were mitigated through reflection on, and changes to pedagogical practice.

Teaching about teaching the socially-just TPSR approach

Learning to teach about teaching any new pedagogical content knowledge is complex as questions of what to teach, how to teach, and when to teach are asked alongside feelings of lack of control and institutional/modular level restrictions. In our case, some of the challenges we had to address were the outcomes of the OAA module already being in place and having to be met, and teaching about teaching a newly conceptualised approach to integrating social justice matters into activity spaces of physical education (i.e. the SJ-TPSR approach). To manage some of the mounting complexities, we made the pedagogical decision to model incremental implementation, explicitly sharing pedagogical decision-making, and layering the SJ-TPSR approach onto the OAA content.

Even before we began enacting the SJ-TPSR approach, we were unsure of how to integrate the approach into an already designed course with defined learning outcomes. We continued to struggle with the challenge as the module progressed. Debroah, one of our critical friends, suggested that the OAA content and structure aligned with many of the tenants of the SJ-TPSR approach (e.g. problem solving, responsibility, debriefing):

If you look at outdoor adventure and the Full-Value Contract, when you’re getting young people talking about how they like to be treated, you could bring in all sorts of issues in terms of gender and race and that kind of thing. (CFM 1)

It’s organic the way it's happening and it’s scary that we don’t have control over what’s happening. Obviously we have control as we planned the lessons, but I’d like to have more control about, ‘this is the [teaching] about [social justice], this is the [teaching] through [social justice], and this is the [teaching] for [social justice] and this is where OAA fits’ … but that [understanding] happens at the end [of the module] I think. (CFM 2)

Even though I’m a bit petrified about it all, when I look at [our conceptualization of what SJ-TPSR might look like in practice], I already do that. The discussion around where [PSTs] see it, where they can do it, bringing their own experiences … facilitating that bit, to me, is where I would need a little bit of help, and I think it’s just because I don’t know social justice. (CFM 3)

Your struggles are exactly what the literature says you should be struggling with – how to give up control, feel like a novice again. You are right on schedule! Model implementation often fails because teachers feel like novices again, it gets too hard, so they revert back to familiar practices – the honeymoon period of excitement fades as does the commitment. (CFM 2)

Alongside role modelling, taking baby steps, and explicitly sharing our reflective and pedagogical decision-making process with PSTs, strategically using the assessment allowed us to reinforce and push PSTs’ learning of the SJ-TPSR approach. Maura designed assessments to further support PSTs’ learning of the approach. PSTs had to choose one social justice matter (prompted by their observations on their school placement) and create a five-phase learning plan on teaching about, through, and for that chosen social justice matter. We learned that the process of engaging with the learning plan assignment supported PSTs’ deepening understanding of the approach. PSTs’ questions about the assessment often linked to questions about the approach. Asking about assessment requirements and providing examples of what they might include in their assignments aided PSTs’ understanding of the concepts. Through the reading of the completed assignments, Maura also found that the assessment provided more opportunity to engage with the readings, the content, and for the PSTs to apply the SJ-TPSR approach to their future teaching (in the form of a learning plan). One PST, Annie, reflected, ‘I really started to think about the [learning] plan assignment and everything kind of came together – like the readings, and the lecture notes, and thinking about my own experiences’ (PST interviews). This is another way in which PSTs’ experience informed our teaching about teaching, in this case, the opportunities and possibilities of supporting learning through assessment, that we will carry forward with us in our future practice.

Learning about teaching the socially-just TPSR approach

In addition to reflecting on our co-teaching through pedagogical decision-making documents, written reflections, and critical friend meetings, PSTs’ experiences simultaneously learning about the SJ-TSPR approach and learning to teach through the SJ-TPSR approach informed our practice. PSTs, for example, were apprehensive about the SJ-TPSR approach in part because they had no prior knowledge of, or experience with, this approach. One practice that resonated with PSTs in supporting their growing comfortability with the approach was the connections to real-life practical examples. Rhoda, for example, reflected that, ‘The a-ha moment [in understanding] would have been when [Dylan] related it [to his] own life in terms of the pronouns and how that experience affected [him]’ (PST interviews). An a-ha moment for Dylan and Maura was when one PST came at the end of the class to discuss they social justice matter of intersectionality. Interestingly, this PST discussed how they chose obesity as their social justice matter but was now moving to body positivity. It showed us the development of PSTs’ ideas around social justice. Everything seemed to be aligning and making sense for everyone. Dylan and Maura felt that this ‘may be because we aligned the three aspects of the module – OAA pedagogical model, socially justice TPSR approach (spaces), and OAA content’ (PDMD). To clarify, The PSTs individually chose a social justice matter and worked with this social justice matter throughout the module. Some chose social injustices such as LGBTQ+ matters, obesity (which moved to body positivity), social class, and race. These were all chosen through positionality and reflection activities so that the chosen social justice matter was meaningful to the PST.

Above all other practices, however, the integration – or layering – of aspects of the SJ-TPSR approach into each and every class (i.e. through repetition) was the one that resonated most prominently with PSTs. Alice shared that, ‘Every week, each activity that we did, was kind of based on [a SJ-TPSR approach] which was good. It was like reinforcing the way it works. Then the reflection after, like how well things worked or didn’t work’ (PST interviews). Similarly, Aidan alluded to consistent integration of the SJ-TPSR approach as a key factor in growing confidence and competence. Aidan emphasised the word ‘constantly’ when speaking about what most supported learning, ‘Through all the activities and through you [Dylan] and Maura constantly bringing it back, saying, “Think about the model, think about the spaces.” It’s actually quite straightforward’ (PST interviews). While Aidan perhaps overstated the simplicity of enacting the SJ-TPSR approach, an understanding of the complexity and necessity to layer learning through repetition was also acknowledged,

Mostly, probably, every class [you touched on the approach]. You would come in, talk about regular things, what we’re going to do that day. [The social justice matter] was still brought up at the start [i.e. awareness talk]. You always made us aware of ‘Ok, we are still focusing this on all different social justice matters and about the spaces’. And then we’d go off and do, whatever it was, whether it was orienteering or the minefield activity … you would throw in some question like ‘Oh, think about one of your social justice matters’ and then afterwards we’d reflect … Maybe at the start I was thinking, ‘Ok, this is going to be intense’. Just the constant learning about it. It was every week; it was the same; it was kind of reminding and refreshing and adding on to our knowledge [which] was nice and easy to understand then at the end. I wouldn’t say it was easy, but the way we were taught about [and through the socially just TPSR approach] made it easy to understand. (PST interviews)

I think it [experience with the SJ-TPSR approach] will definitely influence the way that I approach things, and not just in [physical education], as a generalist primary school teacher. Certainly, it made me aware of other things. So, my placement made me very aware of socio-economic backgrounds. But [this module] also brought ableism and disabilities to my attention because I hadn’t had very much experience with that from placements. So just to think about all the other things, not just someone in a wheelchair [but] all the different types of disabilities and other socially just matters. (PST interviews)

Category 2: The importance of learning together

There was an emphasis on the importance of learning together. The ‘layers’ of learning together were (a) Dylan and Maura and PSTs, (b) PSTs and PSTs, and (c) critical friends. While the layers of learning are intertwined, we will artificially separate them for the purposes of explanation.

Dylan and Maura learning together and with/from the PSTs

It was noted throughout the data how co-teaching enhanced the teaching and learning journey. For example, Dylan had knowledge in the SJ-TPSR approach and the teaching of social justice matters, and Maura had knowledge of TPSR and OAA in the context of generalist primary PSTs. The complementary expertise was vital in enriching the learning for Maura and Dylan and the teaching for the PSTs as described by Maura, ‘At the stage we were at, neither of us could have taught the module on our own due to a deficit in knowledge in one of the aspects’ (CFM 2). In addition, having someone to bounce ideas off such as ‘do you intervene or not’ (Maura, CFM 3) to consult with, and to model for PSTs how learning happens with others was invaluable. The complementary expertise, alongside Dylan and Maura’s willingness to learn with, for, and from one another, contributed to what we learned and can now articulate about our learning journey.

As previously alluded to, there was a level of anxiousness amongst Dylan and Maura in ‘not knowing everything social justice’ (we again revisit this anxiousness in the next category), but through critical friend discussions, we were encouraged to learn with the PSTs and therein, encourage the PSTs to learn with and from each other. Using the PSTs’ life and professional experiences as a starting point proved to be a worthwhile approach. Dylan suggested that,

I think we can get afraid of the social justice piece. I think if we use the [PSTs] as the experts in this case given that they’ve done that knowledge in the different modules [in other courses]. If we had the [PSTs] come in and ‘OK, reflect on your school placement, think of what you’ve learned so far, what is the social justice matter you want to choose?’ (CFM1)

In all, reflecting on the learning journey, we believe learning with PSTs may be one solution to ‘not knowing everything about social justice’. Dylan elaborated stating,

[The challenge is] not knowing enough, but we have to accept that we will never know enough. Social justice is changing so fast, we are not on the ground of social justice [in schools] – we are in our own personal lives, but in schools we are not. We need to accept we do not know enough, but for me, that creates a really great opportunity to work with PSTs as partners because they … are the ones on the ground in schools … experiencing social justice matters in school. (CFM 3)

PSTs learning together

In adjusting our practice to ‘put the ball in the students’ court’, Dylan and Maura enacted student-led and student-centred approaches in our teaching. Speed Dating (sharing with and questioning each other to increase understanding), World Café (working in groups, discussing various parts of a topic from table to table) and OAA activities (such as an orienteering event or group challenge) were teaching methods and strategies we designed to collaboratively co-construct learning about the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of social justice. One example of learning through physical activity was during orienteering. We created stories of children who were experiencing a level of exclusion in physical education due to minority backgrounds and placed pieces of each story at orienteering checkpoints. PSTs had to collect these story pieces while completing the orienteering course. Upon completion of the course, the PSTs would put all the pieces together, discuss the story in their groups, identify the social justice matter, and plan how they could teach about, through, and for the selected social justice matter. One PST reflected on this activity as their ‘a-ha’ moment (i.e. when the SJ-TPSR approach began making sense) and how having the time and space to openly discuss with their peers enhanced their learning:

[An a-ha moment] was during orienteering when we went and picked up different cards and we looked at different kinds of scenarios and just being able to discuss them and hear about what others had thought of for, through, and about. Just being able to listen and ‘Oh yes, that’s a good idea’. Because we were listening to the different ways you’d go about having that child in the class and it was kind of a broad discussion – yes for orienteering, but [also] just for any other PE [physical education] strand.’ (Aidan, PST interviews)

Critical friends learning together

Critical friends (Deborah and Kellie) pushed our thinking, pushed our practices, and helped us vision the bigger picture of the SJ-TPSR approach. We experienced challenges acknowledged in the literature (e.g. embedding social justice content in practical spaces), but having critical friends reassured us of the learning process and the notion of building our practice by taking ‘baby steps’. The following extracted conversation attests to this:

I was confused and am still a little bit confused. [After two weeks of teaching] I’m still kind of seeing [our teaching] a little bit as layering. We have to give the [PSTs] so much information about the what, the why, and where of social justice but I’m still not sure of how to bring it into the actual activity … .Like the example we spoke about last day of the orienteering, as they went around they gathered [stories of children from minority backgrounds] but that’s still layering [social justice matters] on top of orienteering … that’s an orienteering activity with just a task attached that has a social justice focus. Whereas I’m thinking ‘How do I make the actual orienteering itself [a socially just activity]? (Maura, CFM 2)

Maybe you’re worrying too much. Maybe to start with it’s not teaching social justice through social justice. Maybe layering is the place to start. (Deborah, CFM 2)

Category 3: A pedagogy of vulnerability needed?

Throughout the process, it proved important for both teacher educator and PSTs’ learning, particularly given the topic of social justice, that we demonstrated a level of vulnerability. At first, Maura struggled with being anxious and vulnerable stating that,

My anxiousness and vulnerability around even about what a social justice matter was, what teaching about, through, and for was, and I am still going through those [feelings of not knowing] … My own learning was happening throughout that process [of teaching teachers]. (CFM 3)

I think it was Deborah who said we need to show vulnerability in our ‘not knowing enough’. We started to show our vulnerability after our critical friends’ meetings [by way of] showing [PSTs] what we don't know, which is nearly as important as what we do know. (Dylan, FG)

I was talking about what steps are we, as a profession, take doing social justice work. I shared with the [PSTs] that I wasn’t doing any social justice work for the first three years of my teaching. I told them why and then I told them what experiences that changed my mind around that. So, [this was showing] being vulnerable in my own self [and teaching] and role modelling that they can be vulnerable in their teaching.’ (CFM 2)

I think Dylan, when you related it to your own example during your teaching, when you were talking about identity and how people identify and how you wanted to further your knowledge. That kind of just showed how it can be in various different parts of people’s lives and made it kind of aware to us from the onset. That kind of made it easier for me to understand [the SJ-TPSR approach]. (Rhoda, FG)

Discussion

Teacher educators are advised to develop their practice through the examination of the ways in which they approach the teaching of PSTs in relation to promising practices and theories of teacher education, and to make permanent changes resulting in reframed pedagogy and practice (Loughran Citation2014). Berry and Hamilton (Citation2013) suggest that self-study can support this examination, but also make connections to reform from a social change and social justice perspective,

Outcomes of self-study research focus both on the personal, in terms of improved self-understanding and enhanced understanding of teaching and learning processes, and the public, in terms of the production and advancement of formal, collective knowledge about teaching and teacher education practices, programs, and contexts that form an important part of the research literature on teacher education. Both personal and public purposes are concerned with the reform of teaching and teacher education that works from a social change and social justice perspective (1).

Further to this, we strongly suggest that collaborative self-study more explicitly engages PSTs. Baker (Citation2021) and Coulter, Bowles, and Sweeney (Citation2021) valued PSTs as critical contributors to their development as teacher educators and advocated for the place of PSTs as collaborative contributors which would situate PSTs as knowingly and actively involved in the process of teacher development. We support this suggestion as PSTs’ experiences during the course did inform our practices (e.g. baby steps, layering, including personal stories, and being vulnerable), but the interviews offered a more explicit critique of our practices. We wonder about the opportunities, possibilities, and challenges associated with PSTs being knowingly situated as collaborative contributors to the development of our teacher educator practice, in this case, our enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach. As evident from our findings, the notion of learning together (category 2) created a positive learning environment for the teacher educators, PSTs, and critical friends. We strongly advocate for this shift in thinking from mentoring/coaching to critical friendship (MacPhail, Tannehill, and Ataman Citation2021), from teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher to teacher-student with student-teachers (Freire Citation1978), and from teacher-centred approaches to student-centred approaches underpinned by sharing vulnerabilities (hooks, Citation1994). These were strategies which we enacted to create such a positive learning environment. Team teaching and having two critical friends helped this process as the research team, as previously acknowledged, had strong personal and working relationships. This allowed us to invest in creating a safe space and have a level of honesty which created a sense of trust. We believe it was this that minimised any conflicts or difficulties between the team during this enactment. This is not to say there were none, our findings express times of being overwhelmed and ‘trying too much’, but it was our critical friends who validated those feelings and we worked as a team through these challenges. We encourage others embarking on such a journey to invest in a critical friendship relationship following the advice of MacPhail, Tannehill, and Ataman (Citation2021) in how to negotiate power balances in such a relationship.

Final thoughts

While we now have some guidance for ourselves and others with respect to the how of enacting the SJ-TPSR in PETE, as is often the case with self-study research, we are also left with more questions than when we started. Committed to our development as teacher educators, we are continuing to examine these and other questions, as well as the enactment of the SJ-TPSR approach. We trust that sharing our journey thus far will support others interested in enacting the SJ-TPSR approach, and that we, in turn, can learn from others enacting, examining, and articulating their experiences with the approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors).

References

- Baker, Kellie. 2020. “Developing and Articulating a Pedagogy of Physical Education Teacher Education Using Models-Based Practice.” Doctoral diss., Memorial University of Newfoundland. http://research.library.mun.ca/id/eprint/14615

- Baker, Kellie. 2021. “Developing Principles of Practice Implementing Models-based Practice: A Self-Study of Physical Teacher Education Practice.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 41 (3): 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2020-0304.

- Baker, Kellie, Dylan Scanlon, Deborah Tannehill, and Maura Coulter. 2023. “Teaching Social Justice through TPSR: Where Do I Start?” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 94 (2): 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2022.2146611.

- Berry, Amanda. 2007. Tensions in Teaching About Teaching: Understanding Practice as a Teacher Educator (Vol. 5). Dordrecht: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Berry, Amanda, and Mary-Lynn Hamilton. 2013. “Self-study of Teacher Education Practices.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Casey, Ashley, and David Kirk. 2020. Models-based Practice in Physical Education. London: Routledge.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

- Cochran-Smith, Marilyn, Ann Marie Gleeson, and Kara Mitchell. 2010. “Teacher Education for Social Justice: What's Pupil Learning Got to Do With It?.” Berkeley Review of Education 1 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/B81110022.

- Coulter, Maura, Richard Bowles, and Tony Sweeney. 2021. “Learning to Teach Generalist Primary Teachers How to Prioritize Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education.” In Meaningful Physical Education An Approach for Teaching and Learning, edited by Tim Fletcher, Deirdre Ní Chróinín, Doug Gleddie, and Stephanie Beni, 75–86. Oxon: Routledge.

- Crowe, Alicia R., and Amanda K. Berry. 2007. “Teaching Prospective Teachers About Learning to Think Like a Teacher: Articulating our Principles of Practice.” In Enacting a Pedagogy of Teacher Education, edited by Tom Russell, and John Loughran, 31–34. London, UK: Routledge.

- Department of Educaiton and Science. 1999. Physical Educaion Curriculum. Dublin: The Stationary Office.

- Elias, Norbert. 1978. “On Transformations of Aggressiveness.” Theory and Society 5 (2): 229–242.

- Fletcher, Tim, and Mats M. Hordvik. 2023. “Emotions and Pedagogical Change in Physical Education Teacher Education: A Collaborative Self-study.” Sport, Education and Society 28 (4): 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2035345.

- Flory, Sara B., and Dillon Landi. 2020. “Equity and Diversity in Health, Physical Activity, and Education: Connecting the Past, Mapping the Present, and Exploring the Future.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 25 (3): 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1741539.

- Flory, Sara B., and Jennifer L. Walton-Fisette. 2015. “Teaching Sociocultural Issues to Pre-Service Physical Education Teachers: A Self-study.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 6 (3): 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2015.1092722.

- Freire, Paulo. 1978. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 9th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

- Gerdin, Goran, Rod Philpot, Wayne Smith, Katarina Schenker, Lena Kjersti Mordal Moen, Susanne Larsson, Knut Linnér. 2021. “Teaching for Student and Societal Wellbeing in HPE: Nine Pedagogies for Social Justice.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3: p.702922.

- Gore, Jennifer M. 1998. “On the Limits to Empowerment through Critical and Feminist Pedagogies.” In Power/Knowledge/Pedagogy, edited by Dennis Carlson, 271–288. Colorado: Westview.

- Hellison, Don. 2011. Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Through Physical Activity. 3rd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hickey, Chris, Amanda Mooney, and Laura Alfrey. 2022. “Locating Criticality in Policy: The Ongoing Struggle for a Social Justice Agenda in School Physical Education.” Movimento, https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.96231.

- Hill, Joanne, Jennifer Walton-Fisette, Michelle Flemons, Roderick Philpot, Sue Sutherland, S. Phillips, Sara. B. Flory, and Alan Ovens. 2022. “Social Justice Knowledge Construction among Physical Education Teacher Educators: The Value of Personal, Professional, and Educational Experiences.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2022.2123463.

- hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to transgress. New York: Routledge.

- Kirk, David. 1986. “A Critical Pedagogy for Teacher Education: Toward an Inquiry-oriented Approach.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 5 (4): 230–246.

- Kirk, David. 2019. Precarity, Critical Pedagogy and Physical Education. Routledge.

- LaBoskey, Vicki K. 2004. “The Methodology of Self-Study and Its Theoretical Underpinnings.” In International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, edited by John Loughran, Mary Lynn Hamilton, Vicki K. LaBoskey, and Tom Russell, 817–869. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3_21.

- Laboskey, Vicki K. 2009. ““Name It and Claim It”: The Methodology of Self-Study as Social Justice Teacher Education.” Research Methods for the Self-study of Practice 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9514-6_5.

- Landi, Dillon, Katie Fitzpatrick, and Hayley Mcglashan. 2016. “Models Based Practices in Physical Education: A Sociocritical Reflection.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 35 (4): 400–411.

- Loughran, John. 2006. Developing a Pedagogy of Teacher Education: Understanding Teaching & Learning About Teaching. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203019672.

- Loughran, John. 2014. “Professionally Developing as a Teacher Educator.” Journal of Teacher Education 65 (4): 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533386.

- Luguetti, Carla, David Kirk, and Kimberly L. Oliver. 2019. “Towards a Pedagogy of Love: Exploring Pre-service Teachers’ and Youth’s Experiences of an Activist Sport Pedagogical Model.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 24 (6): 629–646.

- Lynch, Shrehan, Jennifer L. Walton-Fisette, and Carla Luguetti. 2022. Pedagogies of Social Justice in Physical Education and Youth Sport. New York: Routledge.

- MacPhail, Ann, Deborah Tannehill, and Rebecca Ataman. 2021. “The Role of the Critical Friend in Supporting and Enhancing Professional Learning and Development.” Professional Development in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1879235.

- Marttinen, R., Host. 2021. “2021 AERA SIG Scholar Lecture by Katie Fitzpatrick.” (No. 160) [Audio Podcast Episode]. In Playing Research in Health & Physical Education. https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/160-2021-aera-sig-scholar-lecture-by-katie-fitzpatrick/id1434195823?i=1000516954256.

- Metzler, Michael. 2017. Instructional Models in Physical Education. Taylor and Francis.

- Mills, Carmen, and Julie Ballantyne. 2016. “Social Justice and Teacher Education: A Systematic Review of Empirical Work in the Field.” Journal of Teacher Education 67 (4): 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116660152.

- Mordal-Moen, Kjersti Mordal, and Ken Green. 2014. “Physical Education Teacher Education in Norway: The Perceptions of Student Teachers.” Sport, Education and Society 19 (6): 806–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.719867.

- Parameswaran, Uma D., Jade L. Ozawa-Kirk, and Gwen Latendresse. 2020. “To Live (Code) or to Not: A New Method for Coding in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Social Work 19 (4): 630–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325019840394.

- Pinnegar, Stephanie. 1998. “Introduction to Part II: Methodological Perspectives.” In Reconceptualizing Teaching Practice: Selfstudy in Teacher Education, edited by M. L. Hamilton, 31–33. Falmer Press.

- Russell, Tom, and John Loughran. 2007. “Enacting a Pedagogy of Teacher Education.” In Enacting a Pedagogy of Teacher Education, edited by Tom Russell, and John Loughran, 1–15. London, UK: Routledge.

- Scanlon, Dylan, Kellie Baker, and Deborah Tannehill. 2022. “Developing a Socially-Just Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) Approach: A Pedagogy for Social Justice for Physical Education (Teacher Education).” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2022.2123464.

- Shelley, Karen, and Louise McCuaig. 2018. “Close Encounters with Critical Pedagogy in Socio-Critically Informed Health Education Teacher Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (5): 510–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1470615.

- Siedentop, Daryl. 2002. “Sport Education: A Retrospective.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 21 (4): 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.21.4.409.

- Tannehill, Deborah. 2016. “My Journey to Become a Teacher Educator.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 21 (1): 105–120.

- Tannehill, Deborah, and Ger Murphy. 2012. “Teacher Empowerment Through a Community of Practice: The Urban School Initiative.” In American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance Annual Conference. Boston, MA.

- Tinning, Richard. 1991. “Teacher Education Pedagogy: Dominant Discourses and the Process of Problem Setting.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 11 (1): 1–20.

- Tinning, Richard. 2002. “Toward a “Modest Pedagogy”: Reflections on the Problematics of Critical Pedagogy.” Quest (grand Rapids, Mich) 54 (3): 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2002.10491776.

- Walton-Fisette, Jennifer L., Sue Sutherland, and Joanne Hill. 2019. Teaching About Social Justice Issues in Physical Education. IAP.

- Wheeler, Sharon, Ken Green, and Miranda Thurston. 2019. “Social Class and the Emergent Organised Sporting Habits of Primary-aged Children.” European Physical Education Review 25 (1): 89–108.

- Wright, Jan. 1995. “A Feminist Poststructuralist Methodology for the Study of Gender Construction in Physical Education: Description of a Study.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 15 (1): 1–24.