ABSTRACT

Background:

The provision of inclusive education in schools is a global priority. However, provision in schools is often criticised for being varied and inconsistent, often perpetuating a rhetoric of exclusion [Warnes, E., E. J. Done, and H. Knowler. 2022. “Mainstream Teachers’ Concerns About Inclusive Education for Children with Special Educational Needs and Disability in England Under Pre-Pandemic Conditions.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs: JORSEN 22 (1): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12525]. These concerns are raised across schooling and subject areas; and Physical Education (PE) is no exception.

Purpose:

The present paper reported results from a scoping review of the literature conducted to answer questions about PE teachers’ subjective interpretations of the meaning and importance of inclusion, the ways PE teachers facilitate inclusion for diverse learners, and the barriers they encounter.

Methods:

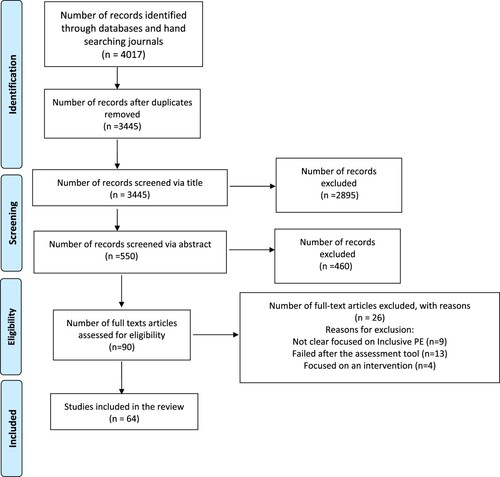

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (extension for Scoping Reviews) informed this review. Adopting elements of the SPIDER tool (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) the database search was conducted in three stages: 1) hand search of titles from key PE journals; 2) systematic search of six databases (EBSCO host , ProQuest, JSTOR, PubMed/Medline, PsycINFO and Web of Science), and 3) search of Google and Google Scholar . Of the 4007 records identified, 64 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Thematic analysis was carried out to identify key themes.

Findings:

Results suggest that inclusion is an important matter in PE provision across different national contexts. The various meanings that teachers attributed to the notion of inclusion appeared to provide a reference point/parameter of how inclusion was enacted in practice. Although the idea of inclusion was supported, most teachers were cautious about what was possible in practice. The most frequently mentioned barriers included the ‘child’, inadequate professional learning, and limited resources and support. Despite the various challenges teachers faced, they reported making efforts to implement a range of inclusive practices, including grounding tasks in students' needs, adopting student centred pedagogies, offering choice, promoting positive peer interactions and teaching by utilising differentiated instruction.

Conclusion:

Acknowledging the subjective nature of such a review, we conclude that findings reinforce but also extend those from previous reviews. The novel contribution lies with the observation that teachers not only faced common barriers to, but also identified shared features of effective inclusion,irrespective of the group of learners they were asked to reflect upon. We have identified key implications for teacher educators, and provided recommendations for future research, which include conducting research in diverse national contexts with cultural responsiveness, better understanding the relationship between teachers’ perceptions/understandings and practices in the context of their complex and diverse environments and cultures, exploring what teachers learn about inclusion, and providing tangible, evidence- informed pedagogies for inclusion as these are implemented in various contexts.

Introduction

The provision of inclusive education in schools is a global priority (United Nations Citation2015). In line with social justice goals, inclusion means that children and young people are treated equitably and with dignity, regardless of their background, identity or circumstances. Inclusion also promotes belonging and learning together in an environment where support and appreciation of individual differences is the norm (UNESCO Citation2017). However, provision in schools is often criticised for being varied and inconsistent, often perpetuating a rhetoric of exclusion (Warnes, Done, and Knowler Citation2022). These concerns are raised across schooling and subject areas; and Physical Education (PE) is no exception (Makopoulou et al. Citation2022).

Inclusive PE (IPE) is often promoted as a vital platform for facilitating social integration (UNESCO Citation2015). Despite this assertion, researchers have repeatedly argued that PE occupies a ‘highly contested and conflicting space’ in young people’s minds (Fitzpatrick Citation2019, p. 1129). According to Kirk (Citation2010), the subject is entrenched with one-size-fits all practices which persistently result to some students being more likely than others to benefit from their PE experiences. At the same time, there is mounting evidence that PE is failing to serve children who do not ‘belong’ to the mainstream. Students diagnosed with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (thereafter referred to as SEND, a term used in the UK) are a particularly vulnerable group; a group that has historically been told they cannot engage and achieve; and who have, at best, been exposed to low expectations or, at worst, had experiences of exclusion and bullying (Haegele et al. Citation2021).

More recently, similar concerns have been raised for other groups of students, who are likely to be marginalised. In the context of increasing student diversity, there is the assertion that children come to schools from an array of backgrounds that differ in respect to their culture, religion, ethnicity, race, socio-economic status, the place of birth, as well as their gender and sexual (and other) identities (e.g. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex (LGBTQI+)). These ‘other’ groups will be referred to thereafter as marginalised groups (American Psychology Association [APA] Citation2023). Scholars examining the experiences of various marginalised groups caution that deep-seated and persistent structures, socio-cultural influences and negative attitudes limit the possibilities of addressing learner diversity adequately (Berg and Kokkonen Citation2022; Doolittle et al. Citation2016; Lleixà and Nieva Citation2020; Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021). In this context, we agree with Penney et al. (Citation2018, 2) that addressing inclusion ‘remains a notable challenge’ for the PE profession internationally.

It is established that the quality of teaching is one of the most important school-based factors influencing student learning (Hattie Citation2009). Thus, gaining greater clarity about the meaning and application of IPE from the perspective of teachers is a significant line of research which is accumulating. Covering publications between 1975-2018, existing reviews focus on the inclusion of SEND students only (Miyauchi Citation2020; Pocock and Miyahara Citation2018; Qi and Ha Citation2012; Rekaa, Hanisch, and Ytterhus Citation2019; Tarantino, Makopoulou, and Neville Citation2022). Results from these reviews suggest that PE teachers: (i) Are supporting the ideal of inclusion, but attitudes are mixed, largely influenced by the child’s type of disability; (ii) Have limited resources and support (e.g. Continuing Professional Development – CPD); and, consequently, (iii) Report lack of knowledge, confidence and competence in implementing IPE.

Despite these significant findings, no previous review has synthesised evidence on teachers’ perceptions and practices about inclusion in the context of learner diversity more broadly, and such a review is warranted. To address this gap, between December 2022 and September 2023 we conducted a scoping review of empirical research to answer the following questions: (1) What are PE teachers’ subjective interpretations of the meaning and importance of inclusion for diverse learners in PE? (2) How do PE teachers facilitate successful IPE for diverse learners and what barriers do they encounter? By looking across the recent literature (last 20 years), the purpose of this review was to draw together some of the key issues and themes running through published research and to delineate major lessons and implications for policy, research and practice.

Methods

Protocol and registration

Once the key aims of this review were agreed, the review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42023392501). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (extension for Scoping Reviews) (Tricco et al. Citation2018) informed this review, including the structure of this methods section.

Search strategy & framework

The SPIDER tool (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) (Cooke, Smith, and Booth Citation2012) was considered the most appropriate framework to inform the search strategy. After initial exploratory database searches, the adaptation of the SPIDER tool was necessary to identify more focused and relevant studies. The revised tool utilised in this review was SPiE, including three broad areas: Sample, Phenomenon of interest and Evaluation. shows how the SPiE was applied, including key search terms used.

Table 1. The revised SPiE Framework and key terms used.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria included papers which: [1] were written in English language; [2] were published in peer reviewed journals the last 20 years (between January 2002 and December 2022); [3] contained original empirical research; and [4] full texts were accessible online. Despite including only studies reported in English, the 20-year range allowed the inclusion of sufficient literature, spanning the development of key legislation globally. Our sample of interest were PE teachers but also adapted physical educators or general teachers teaching school aged children from 4-18 years of age. Studies were excluded if: [1] had a focus on young adults (19 years and older); [2] were written in languages other than English; [3] were published outside the review period; [4] were considered grey literature (e.g. conference papers, dissertations, books/book chapters); [5] focused on extra curriculum programmes; and [6] included perceptions from school staff other than teachers (e.g. teaching assistants, or Special Education Needs Coordinators).

Databases and search strategy

The database search was conducted in three stages. Stage 1 involved carrying out a hand search of titles in the content pages of six established Physical Education Journals, such as Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, Sport Education and Society, Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, and Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. Stage 1 informed the definitive version of SPiE (). In Stage 2, seven electronic databases were searched by applying the SPiE tool: -(EBSCO Host Education Database, ProQuest, JSTOR, PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science). Stage 3 included a parallel hand search of Google and Google scholar to ensure that the search was as comprehensive as possible.

Screening process and study selection

Once all results/titles were imported into an excel spreadsheet, the first author identified and removed all duplicates. Subsequently, the first two authors performed title screening first, followed by abstract screening, using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Quality appraisal was conducted once papers were screened for full text reading. The Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study designs (ICROMS) (Zingg et al. Citation2016) and the Mixed Method Appraisal tool (MMAT) (Hong et al. Citation2018) used to assess the quality of qualitative and quantitative/mixed method studies correspondingly. Uncertainties/disagreements on the final decision were resolved through discussions which were embedded throughout the process. Of the 90 papers identified for full text review, 64 studies met the inclusion criteria and subsequently included in this review. provides a breakdown of this process.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted in line with a data extraction framework developed for this review. To ensure consistency between all three authors, the framework was piloted by comparing and discussing the three authors’ independent data extraction notes on three randomly selected papers. This process gave the team the confidence that there was enough consistency in the process. The remaining papers were randomly divided between the three authors for independent data extraction. Regular meetings were conducted to discuss progress, notes and thoughts.

Analysis and synthesis of findings

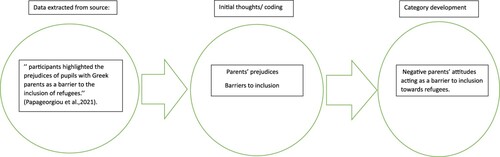

Following Pollock et al. (Citation2023) recommendation, inductive thematic analysis was conducted. A similar process to the data extraction described above was adopted, ensuring consistency between the three authors before proceeding to independent analysis. All data were treated as qualitative and were analysed using constant comparative method, involving open coding, axial coding and ultimately selective coding to condense to develop categories and themes (Thomas Citation2022). During the analysis stage, the review team met several times to discuss and examine preliminary notes about code development, discuss similarities and/or differences and refine the coding hierarchy. The process was further supported by memo writing, a process involving analytical reflections and interpretation of evidence to consolidate which codes can be grouped together to create categories (Charmaz Citation2006). provides a sample of the process of developing categories and themes, but the subjective nature of this process needs to be underlined.

Results

Results are reported in three themes: perceptions of the meaning and importance of inclusion; barriers/challenges encountered; and IPE pedagogies. We acknowledge that it would not be possible to provide detailed discussions for each paper. To ensure our analysis and interpretations are warranted, we have provided examples/claims from a range of papers conducted across diverse national contexts. Before reporting the themes, we offer readers reflections on the key characteristics of the location and focus of the studies included in the review, to contextualise and interpret the results. The key characteristics of the studies included in the present review can be found in .

Table 2. Summary of reviewed articles.

Trends in IPE research – reflections and recommendations

A breakdown of the studies per country of origin and student groups is presented in . Firstly, the studies included were conducted mostly in the US or the UK, while representation of the remaining countries was substantially smaller. Secondly, a predominant focus on SEND (59%) and other marginalised groups (e.g. obese/overweight, immigrants) (35%) suggests that most IPE research adopts a categorical approach. Specifically, the percentage of studies exploring teachers’ perceptions about inclusion/exclusion of diverse learners in PE, irrespective of predefined categories, was substantially smaller (6%) compared to those targeting marginalised groups (94%).

Table 3. Target student population and location of studies.

Contemporary understandings of the term intersectionality are relevant and need to be considered carefully in this context. According to APA (Citation2023), intersectionality refers to the cumulative ways ‘multiple forms of discrimination combine, overlap, or intersect … to produce and sustain complex inequities’ (6). The intersection of children’s multiple and overlapping identities (APA Citation2023) form what Rowan et al. (Citation2021) called a ‘demographic and cultural diversity’ that matters in social and educational contexts (113). However, whilst intersectionality offers a critical tool to better understand ‘the different avenues of disadvantage and disempowerment’ (Mirza Citation2023, p. 11), using this as a framework to better understand teachers’ subjective experiences has not extensively utilised in IPE research.

The meaning and importance of inclusion

Overall, teachers were committed to the ideal of inclusion, having a strong sense of commitment (Baldwin Citation2015; Mihajlovic Citation2019), a professional responsibility and duty of care (Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017) as well as the aspiration (An and Meaney Citation2015; Morley et al. Citation2021), dedication (Ko and Boswell Citation2013) and motivation (Hodge, Ammah et al. Citation2009; Hodge, Haegele et al. Citation2018) to include all, despite the numerous challenges they faced. There was also a degree of clarity about the benefits of inclusion. Underpinned by a social discourse of ‘acceptance of differences’, inclusion was perceived as encouraging the development of social values and skills (e.g. empathy and consideration towards others) (e.g. Lleixà and Nieva Citation2020; Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017; Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021). Despite largely positive evidence about teachers’ commitment to inclusion, there were still some teachers who held negative attitudes towards the inclusion of SEND students, even when the culture of the school was underpinned by humanistic values and embraced diversity (Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017). Haegele, Zhu, and Davis (Citation2018, Citation2021) reported that the most significant teacher-related barriers to IPE related to limited knowledge and negative attitudes, whilst Mihajlovic (Citation2019) found that negative attitudes were often underpinned by pedagogies promoting performance and competition.

Considering how teachers understood the meaning of inclusion was of interest. Yet, this has not been extensively researched. Only a small number of studies (n = 5) examined teachers’ interpretations, and this was in relation to the inclusion/exclusion of SEND students only. Firstly, scholars identified ‘nuanced’ differences in the ways teachers understood inclusion (Morley et al. Citation2021, 407). For example, Fitzgerald (Citation2012) identified inconsistency in teachers’ interpretations. Some argued that inclusion was primarily about the appropriate placement of students in the right learning environment (within or outside of main PE), whilst others had concerns that separating SEND from mainstream PE is exclusionary in nature. Thus, different teachers had different parameters of what was acceptable inclusive practice, and these perceptions appeared to be inextricably linked to the meaning attributed to the concept.

The way teachers understood inclusion also appeared to evolve over time. Whilst in early publications, most teachers talked about equality (e.g. offering the same opportunities) (Ko and Boswell Citation2013; Smith Citation2004) and providing the right placement so that students ‘fit’ in lessons (Fitzgerald Citation2012; Smith Citation2004), in a more recent study, some PE teachers defined inclusion as necessary to ensure SEND students feel valued and are treated with respect (Morley et al. Citation2021). Teachers in other studies made references to inclusion as a way of enabling students and their peers to learn with each other in environments that instill a sense of belonging (Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017; O’Connor and McNabb Citation2021)

The ‘reality’ of inclusion: what barriers do teachers experience?

Although the idea of inclusion was supported, most teachers were cautious about what was possible in practice. The most frequently mentioned barriers across different studies were the ‘child’, inadequate professional learning, and limited resources and support.

The child as a key barrier to inclusion

PE teachers in 31 studies talked about the child as presenting one of the main barriers to inclusion. Certain SEND groups were perceived as presenting greater challenges for inclusion. The nature and degree of disability defined the extent to which inclusive practices were seen to be possible, and segregated provision was a justifiable option for some. There was a general feeling across those studies that teaching students with mild disabilities was easier because it required less adaptation/modification in planning and less one-to-one support (e.g. Casebolt and Hodge Citation2010; Morley et al. Citation2005; Rojo-Ramos et al. Citation2022). In contrast, because of their ‘unpredictable’ and ‘disruptive’ behaviour, students with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties were perceived to require greater teacher attention (e.g. Casebolt and Hodge Citation2010; Morley et al. Citation2005; Morley et al. Citation2021). Individual sports were, for some teachers, easier to adapt to include SEND pupils compared to fast-paced, competitive team games (Morley et al. Citation2021), whilst others believed that the social interaction of team sports was cumbersome for SEND pupils (O’Connor and McNabb Citation2021). To address these challenges, some teachers offered ‘individualistic approaches’ (An and Meaney Citation2015) often teaching SEND students in separate, small group settings but other teachers were highly concerned about this approach (Wilson, Kelly, and Haegele Citation2020).

Beyond SEND, the complexity, diversity and uniqueness of other marginalised groups’ identities were also seen as a hindering factor for inclusion. Language barriers (Baldwin Citation2015), religious constraints (with potentially negative perceptions about the value of PE and healthy lifestyles), the ‘complex’ nature of cultural identities (e.g. Dagkas Citation2007; Lleixà and Nieva Citation2020; Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021), and students’ body type and size (Doolittle et al. Citation2016; Rukavina et al. Citation2019) were important considerations for PE teachers in different countries. A striking example comes from teachers of overweight and obese students, many of whom believed that these learners hinder their own participation and learning, either because they lack the physical ability (e.g. fitness), competency, or motivation to ‘fit in’ the organised physical activities (Doolittle et al. Citation2016). Teachers who taught Muslim girls were also concerned that the complex nature of cultural identities was a significant reason that hindered girl’s own inclusion in PE (Lleixà and Nieva Citation2020).

Teachers also argued that the negative attitudes held by some of the peers (and some of the parents) towards marginalised groups presented a significant challenge to IPE. Prominent in their reflections were incidents of peer exclusion, bullying and discriminatory comments (e.g. Berg and Kokkonen Citation2022; Odum et al. Citation2017) which often had a negative effect on student’s participation (e.g. Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). Incidents of exclusion and bullying of SEND and other marginalised students by peers had a negative effect on students’ participation (Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). Parents’ negative views about their children interacting socially with ‘others’ were also perceived to be detrimental as they influenced children’s views of PE and their interactions with others (Dagkas, Benn, and Jawad Citation2011; Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021; Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). Thus, creating a ‘safe’ environment where everyone feels welcomed had its own challenges.

Professional learning for inclusion: is it effective?

There was consistent evidence that PE teachers perceived engagement in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) necessary to support inclusive provision. A lot of professional learning was taking place ‘on the job’, as teachers shared experiences and resources, engaged in discussions to set goals, conducted collegial observations and participated in meetings with social workers and other professionals (An and Meaney Citation2015; Grenier Citation2011; Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). Such interactions were valuable in understanding students better, having higher expectations for all (Grenier Citation2011) and increasing teachers’ confidence (Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). However, Ko and Boswell's (Citation2013) research suggested teachers had limited time and opportunities to access this type of informal CPD.

In a third of the studies reviewed (n = 23), teachers viewed themselves as ‘inadequately’ prepared to meet students’ unique, complex needs and this was the outcome of limited Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and untargeted CPD. CPD seeking to support teachers to include and ‘empower’ students from marginalised groups appeared to be largely unavailable, but teachers believed that this kind of focused CPD (on topics such as intercultural education and learner diversity) would be an important and beneficial mechanism to achieve better inclusion (e.g. Baldwin Citation2015; Dagkas Citation2007; Lleixà and Nieva Citation2020; Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021; Wagner, Bartsch, and Rulofs Citation2018). Whilst teachers reported some engagement with CPD for SEND students, they largely believed that there was scope for more and better professional learning. Some teachers reported that the CPD attended was unhelpful either because of a focus on certain disabilities that were not their priority (Morley et al. Citation2021) or because, the CPD was not applied to PE or adapted PE (McGrath, Crawford, and O’Sullivan Citation2019; Morley et al. Citation2021). Teachers also noticed discrepancies between the content of their ITE/CPD and the reality of working in mainstream schools (Morley et al. Citation2021).

We observed that the content – what teachers learn – was important for these teachers, but the evidence reported in the studies did not offer nuanced detail on what teachers perceived to be valuable professional knowledge for inclusion.

Systemic barriers and school support

In 22 studies, teachers articulated concerns related to systemic barriers to inclusion and these were related to policy and curriculum, school resources, equipment/facilities and staff (un)availability (e.g. Benzinger et al. Citation2023; Fejgin, Talmor, and Erlich Citation2005; Morrison and Gleddie Citation2021; Wagner, Bartsch, and Rulofs Citation2018). In a small number of studies, the curriculum was described as narrow, inhibiting the appropriate accommodation of learners' differences (Baldwin Citation2015). In contrast, a ‘flexible’ curriculum affords teachers the opportunity for initiative and better accommodation of students’ needs (e.g. Dagkas Citation2007). The competitive nature of PE was also believed to be a constraining factor, leading to arguments and tensions between native and refugee students (Papageorgiou et al. Citation2021).

Inclusion was also dependent on school factors, such as school culture, policies and available resources. A supportive school ethos was considered a core factor (Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017) and consistent implementation of policies enabled teachers to respond appropriately to incidents of misbehaviour or peer-bullying towards overweight and obese students (Rukavina et al. Citation2019). Teachers across 18 studies also argued that without adequate resources (e.g. specialised equipment, space, class size), support (e.g. time for planning) and adequate weekly time for PE, it was difficult to address the needs of all students, especially those with SEND and other marginalised groups (e.g. Baldwin Citation2015; Filipčič, Burin, and Leskošek Citation2021; Hodge et al. Citation2004; Hodge, Ammah et al. Citation2009; Hodge, Sato et al. 2009 Nanayakkara Citation2022; Rojo-Ramos et al. Citation2022; Wilson, Kelly, and Haegele Citation2020).

Inadequate resources were primarily about limited human resources. The lack of availability of additional support staff in lessons, such as Teaching Assistants (TAs), was a barrier identified, especially when class sizes were large. Lack of support staff equated to teachers’ inability to provide SEND students (especially those with severe and complex needs) the one-to-one teaching required to stay engaged in tasks (Ko and Boswell Citation2013; O’Connor and McNabb Citation2021). Teachers underlined that TAs need to be knowledgeable, show enthusiasm, and have the required skills in PE to add value (Morley et al. Citation2021). There were also views that TAs was an under-used resource because neither teachers nor TAs had adequate training on how to maximise TA's contribution (O’Connor and McNabb Citation2021).

Inclusion enacted: effective IPE pedagogy?

Despite the various challenges faced, teachers reported making efforts to implement what they perceived to be inclusive practices. They talked primarily about understanding students, adopting student-centred pedagogies, offering choice, promoting positive peer interactions and adopting differentiated instruction.

Understanding students and building rapport

Developing the right relationships, by demonstrating a personal interest, and establishing effective communication with the students was important (Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017). In 15 studies, teachers sought to build positive relationships and to develop mutual trust with their students. For example, in Canada, teachers underlined the importance of building rapport with all their students to ensure students felt comfortable and welcomed in PE (Patey et al. Citation2021). Similarly, most teachers in China, attempted to create a warm and welcome environment for their SEND students by providing positive feedback and praising students’ actions. They argued that such positive reinforcement was paramount to build the right kind of relationship with their students (Wang, Wang et al. Citation2015).

Beyond these efforts to build personal rapport, knowledge-about-the child could derive from information available in SEND students’ Individual Education Plans (An and Meaney Citation2015), consultation with colleagues (e.g. Ko and Boswell Citation2013; Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017; Wilson, Kelly, and Haegele Citation2020), or via dialogue with the students’ families, which enabled teachers to learn about their students’ backgrounds, interests and needs (Qi, Wang, and Ha Citation2017). Working closely with parents to communicate policy expectations and to raise awareness of the value of PE were important strategies for breaking down knowledge and cultural barriers for Muslim girls (Dagkas, Benn, and Jawad Citation2011). Teachers in Lleixà's and Nieva's (Citation2020) study underlined how important it would be for teachers to engage in a dialogue with immigrant families to get to know each other better (but this was not established practice).

Student-centred pedagogies and student choice

Building upon this knowledge-of-the-child, some teachers argued that engaging students actively in the learning process and giving them choice made the learning environment more inclusive. Patey et al. (Citation2019) reported that learner-centred pedagogies, alongside a strengths-based, can-do approach, were advocated by teachers as enabling inclusion. An indicative example was evident in Patey's et al. (Citation2021) study, where teachers offered opportunities to students to get involved in learning by creating their own games in PE and this was perceived as a powerful way to make learning experiences more inclusive. Some teachers also talked about choice. We however observed that the degree of choice teachers talked about varied, and that choice could take different forms.

Mihajlovic (Citation2019) described how teachers offered students choice of activities ‘based on students’ individual interests’ to increase participation (e.g. goalball). Teachers in Rukavina et al. (Citation2015) study talked about ‘first order instructional strategies’ (p.99) to enhance the participation of overweight and obese students (e.g. proactive decision-making, eliminating spotlighting, providing choices) and ‘second order instructional approaches’ (p.101) involving systematic differentiated instruction towards individual students. Other teachers talked about choice in how students learn, encouraging them to engage more actively in their own learning (e.g. Furuta et al. Citation2022; Majoko Citation2019; Patey et al. Citation2021).

Differentiated instruction: an inclusive approach implemented in the right ethos?

A key strategy in enacting inclusion, as reported consistently in 15 studies was the use of differentiated instruction (DI). For SEND students, DI was perceived to provide access to educational resources (Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017), affording appropriate participation (Mihajlovic Citation2019) and tailored opportunities for practice (e.g. Majoko Citation2019; Overton, Wrench, and Garrett Citation2017) so that students experienced success (Wilson, Kelly, and Haegele Citation2020). Teachers reported differentiating by equipment, rules and various aspects of the learning environment, including grouping arrangements (e.g. small group modified tasks), use of space and time for practice. Teachers in Barker et al. (Citation2021) study engaged in meaningful discussions of how they can modify/adapt activities for overweight students to enable them to participate in PE. Activities often included parallel tasks as a measure to help overweight students to not feel that they are being observed by their peers in a way that would make them feel ashamed.

Some of the teachers, however, acknowledged that DI was not panacea. Teachers in Qi, Wang, and Ha (Citation2017) study raised concerns that DI could result in SEND students being singled out or even marginalised, with potentially significant negative impact on their psychological and physical development. What appeared to distinguish stigmatisation from genuine inclusion was the nature of peer interactions and this was discussed in both SEND-focused and other marginalised groups studies. Specifically, Grenier (Citation2011) observed that the provision of additional support through DI needs to be done in a way that SEND students stand out in a positive light; i.e. by establishing their presence and participation as valuable members in the class. Establishing the right ethos, positive peer interactions, and inter-dependence was important in reducing the marginalisation and isolation of students with ‘stigmatised' attributes.

Positive peer interactions and cooperative learning

Teachers in 14 studies argued that utilising cooperative practices with heterogeneous grouping (e.g. tasks that require input from all, collaborative problem solving and positive inter-dependence) was a key approach to inclusive education. For some teachers, teaching PE inclusively meant the facilitation of nurturing relationships between students (Majoko Citation2019), and the creation of an atmosphere of ownership (Furuta et al. Citation2022) that ‘embrace multiple perspectives and provide equitable opportunities for learning’ (Philpot et al. Citation2021, p.2).

A significant portion of the teachers in Furuta's et al. (Citation2022) study said they used peer tutoring strategies so that students help their Japanese language peers to understand the content in PE activities. Teachers in Lleixà and Nieva (Citation2020) planned group work to foster student collaboration to avoid isolation of immigrant students. In relation to the inclusion of obese students, Rukavina et al. (Citation2019) reported that whilst some teachers did not change their ‘traditional’ provision, others grounded the learning environment in personal and social development principles to promote and celebrate difference and diversity. Teachers in Barker’s (Citation2019) study attempted to introduce ‘open-minded’ activities to help all students understand better the values and rules that derive from different cultures in sports and games. Despite these positive examples, building positive peer relationships for effective inclusion was not an established practice across the different studies reviewed. As noted above, teachers raised serious concerns about those students who wered negative towards otherness, lacking the knowledge, understanding and skills to interact productively and meaningfully. Thus, peer interactions were viewed as both a tool for – but also a barrier to – inclusion.

Discussion and recommendations

The present paper reported results from a scoping review conducted to answer questions about PE teachers’ subjective interpretations of the meaning and importance of inclusion, the ways PE teachers facilitate inclusion for diverse learners, and the barriers they encounter. A total of 64 empirical studies were conducted in 24 different countries and were included in the review. We observed a dominance of specific research contexts and a prevailing categorical understanding in IPE research. To address these, it is imperative to: (1) widen the reach but also strengthen the evidence base of IPE research in diverse national contexts and across all continents with cultural responsiveness (APA Citation2023) (recommendation #1); and (2) explore IPE from an intersectional standpoint to develop a nuanced understanding of the complexity of inclusion in modern PE classrooms (recommendation #2).

Overall, results suggest that teachers are mostly committed to the ideal of inclusion which appeared to have consolidated its position as ‘a moral and legal imperative’ (Kefallinou, Symeonidou, and Meijer Citation2020, 136). Whilst not extensively researched, in recent studies, teachers’ understandings of inclusion reflected a deep commitment to inclusivity and diversity, aligned with contemporary thinking. When inclusion is approached with a focus on creating a sense of belonging, it is more likely for students to feel valued, respected and welcomed, positively affecting their overall sense of wellbeing (UNESCO Citation2017). On the one hand, the variety in teachers’ interpretations was perhaps anticipated. Globally, national educational policies for inclusion differ considerably (European Agency Citation2015) because of diverse and evolving socio-economic, educational, cultural and historical circumstances (Ramberg and Watkins Citation2020). Whilst this disparity was expected, the observation that constructions of the meaning of inclusion direct or shape teachers’ practices is a significant one with clear implications for research and practice.

We recommend that future IPE research develops greater understanding of teachers’ interpretations of the notion of inclusion in the context of their unique contexts (recommendation #3) and examines how teachers’ understandings shape their approaches to IPE in culturally diverse research contexts (recommendation #4). Results have clear implications for teacher educators too, who need to work with trainee and practicing teachers to discuss, negotiate and co-construct the meaning of inclusion as a broad concept that goes beyond the mere presence and participation of learners in lessons.

Teachers, however experienced significant barriers to inclusion. The most frequently mentioned were the ‘child’, inadequate CPD and limited resources and support. Echoing results reported in previous systematic reviews (Rekaa, Hanisch, and Ytterhus Citation2019; Tarantino, Makopoulou, and Neville Citation2022), certain SEND students were perceived as presenting greater challenges for inclusion compared to others. Beyond SEND, the complexity, diversity and uniqueness of other marginalised groups identities were also seen as a hindering factor for inclusion. At a first glance, the views teachers expressed about the child as the barrier suggest that teachers think in a deficit way about their students. Locating the problem with the child is problematic, since it draws teachers’ attention away from entrenched institutionalised inequalities and, arguably, their own responsibilities for inclusion. We want to approach this finding with nuance, however.

Teaching takes place in social settings where exclusion is deeply structural and cultural (Slee and Allan Citation2001). When schools do not provide the necessary resources and support, teachers may struggle to meet the needs of these students, leading to the perception of students as barriers, diverting their attention away from the wider systemic and cultural barriers to inclusion (Azzarito and Hill Citation2013). In contrast, when schools have an embedded inclusive culture, permeating all layers of practice, teachers are more likely to view each child as a unique individual with valuable contributions to make. It is in these cultures of sustained focus on genuine inclusion that even subtle discrimination and exclusionary practices that may still exist are identified, scrutinised and change (Pocock and Miyahara Citation2018).

Unsurprisingly, teachers talked about inadequate and insufficient CPD, bringing to the forefront once again the debate on how teacher educators engage with the challenge of preparing and supporting teachers to deal with difference. Research on the features of effective CPD has consistently argued that CPD needs to be tailored to teachers’ needs (Tarantino, Makopoulou, and Neville Citation2022), encourage the ‘disturbance’ of teachers’ embedded practices, beliefs, attitudes and values (O’Connor Citation2016), and support teachers develop the critical tools to analyse the effects (and appropriateness) of IPE pedagogies (Makopoulou Citation2018, Citation2009; Makopoulou et al. Citation2022). Yet, questions need to be asked about the capacity of ‘high quality CPD’ to provide sustainable solutions . Elmore’s (Citation2002, p. 3) observation that further investment to a ‘low-capacity, incoherent system is simply to put more money into an infrastructure that is not prepared to use it effectively’ is relevant here. Given substantial evidence around the limitations of CPD interventions (Makopoulou et al. Citation2022), there is some evidence to suggest that embedding high quality professional learning practices in schools might yield more sustainable results. IPE researchers need to develop a clear research strategy on ways to promote, support and evaluate school-based CPD initiatives to better understand what teachers learn about inclusion and how contextual and other factors shape that learning (recommendation #5).

In line with their reported commitment, teachers reported making methodical and systematic efforts to include all students. Despite the different locations the studies were conducted, and irrespective of the specific group of students teachers were reflecting upon, one of the most frequently mentioned approaches to inclusion was differentiated instruction (DI). A degree of critical disposition towards DI was evident when teachers underlined the importance of avoiding singling out students as different, acknowledging that there is a clear danger that DI can unintentionally contribute to student stigmatisation. To alleviate these concerns, establishing the right ethos, providing cooperative learning opportunities and promoting positive peer interactions were seen as powerful approaches to inclusion. However, core pedagogies for inclusion, as identified in the educational literature, were less prevalent or even absent from teachers’ reflections. These include student choice as a tool to inform pedagogical decision-making by challenging power relations and established norms, the notion of diversification of learning opportunities for all (rather than some), and the limitations of teacher-determined differentiation (Florian Citation2014).

Finally, peer interactions were viewed as both a tool for – but also a barrier to – inclusion. There was, however, little discussion on the pedagogies or approaches adopted to address the presence of negative peer interactions. According to Juvonen et al. (Citation2019), peer dynamics are complex and challenging, and, if left undisrupted, they can unfold organically in ways that can lead to exclusion. To address this, school administrators and teachers need to, firstly, avoid instructional practices that segregate groups of students in ways that highlight differences; and secondly, monitor carefully learning structured interactions with sensitive awareness of social relations (Juvonen et al. Citation2019).

Results reported here suggest that some of teachers’ reflections were at odds with the above guidance (e.g. some teachers promoted segregated provision as the default approach). There was also very little reference to investing time to strengthen students’ cultural responsiveness (APA Citation2023), emotional intelligence and social skills to support positive and appropriate peer interactions and social inclusion (Kefallinou, Symeonidou, and Meijer Citation2020). Therefore, teachers need further support in implementing such pedagogies more consistently and effectively. Further research is also required to better understand what pedagogies for positive, inclusive, peer interactions look like in PE (recommendation #6).

Conclusion

The present paper reported results from a scoping review conducted to answer questions about PE teachers’ subjective interpretations of the meaning and importance of inclusion, the ways PE teachers facilitate inclusion for diverse learners and the barriers they encounter. Acknowledging the subjective nature of such a review, we conclude that findings reinforce but also extend those from previous reviews. The novel contribution, however, lies with the observation that the barriers teachers experience appeared to be the same irrespective of the group of learners they were asked to reflect upon. Equally, the positive approaches for inclusion identified shared common features, irrespective of who the learners are. Thesewere largely underpinned by notions of differentiation, positive peer interactions and social learning experiences. We have identified key implications for practitioners and directions for future research, including conducting research in diverse national contexts with cultural responsiveness, with priority placed in better understanding the relationship between teachers’ perceptions/understandings of inclusion and the practices adopted in the context of complex and diverse learning environments and school cultures, and in developing more nuance in what teachers learn about inclusion and how this learning shapes their practices. The finding that peer interactions were perceived as a tool for inclusion but also a key factor for exclusion also deserves further investigation. Future research needs to also consider successful administrative practice (i.e. supervision and support of positive inclusion practices by administrators, and improved CPD and other resources) but also to identify ways to better understand the power of cultural and institutionalized inequities, promoting advocacy to counteract such influences.

RESPONSE TO REVIEWERS COMMENTS .docx

Download MS Word (47.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alhumaid, M. M. 2021. “Physical Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Toward Including Students with Autism in Saudi Arabia.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (24): 13197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413197.

- American Psychological Association. 2023. Inclusive Language Guide. 2nd ed. Apa.org. https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/language-guidelines.pdf.

- Ammah, J. O. A., and S. R. Hodge. 2005. “Secondary Physical Education Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Teaching Students with Severe Disabilities: A Descriptive Analysis.” High School Journal (Chapel Hill, N.C.) 89 (2): 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.2005.0019.

- An, J., and K. S. Meaney. 2015. “Inclusion Practices in Elementary Physical Education: A Social-Cognitive Perspective.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 62 (2): 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2014.998176.

- Azzarito, L., and J. Hill. 2013. “Girls Looking for a ‘Second Home’: Bodies, Difference and Places of Inclusion.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 18 (4): 351–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.666792.

- Baldwin, C. F. 2015. “First-year Physical Education Teachers’ Experiences with Teaching African Refugee Students.” SAGE Open 5 (1): 215824401556973. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015569737.

- Barker, D. 2019. “In Defence of White Privilege: Physical Education Teachers’ Understandings of Their Work in Culturally Diverse Schools.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (2): 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1344123.

- Barker, D., M. Quennerstedt, A. Johansson, and P. Korp. 2021. “Physical Education Teachers and Competing Obesity Discourses: An Examination of Emerging Professional Identities.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE 40 (4): 642–651. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2020-0110.

- Benn, T., and G. Pfister. 2013. “Meeting Needs of Muslim Girls in School Sport: Case Studies Exploring Cultural and Religious Diversity.” European Journal of Sport Science: EJSS: Official Journal of the European College of Sport Science 13 (5): 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.757808.

- Benzinger, J., J. R. Crane, A. M. Coppola, and D. J. Hancock. 2023. “Physical Educators’ Perceptions and Experiences of Teaching Students with Mobility Disabilities.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly: APAQ 40 (2): 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2022-0092.

- Berg, P., and M. Kokkonen. 2022. “Heteronormativity Meets Queering in Physical Education: The Views of PE Teachers and LGBTIQ+ Students.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 27 (4): 368–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1891213.

- Cameron, N., and L. Humbert. 2020. “‘Strong Girls’ in Physical Education: Opportunities for Social Justice Education.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (3): 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1582478.

- Casebolt, K. M., and S. R. Hodge. 2010. “High School Physical Education Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching Students with Mild to Severe Disabilities.” Physical Educator 67 (3): 140–155.

- Charmaz, K. C. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Cooke, A., D. Smith, and A. Booth. 2012. “Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis.” Qualitative Health Research 22 (10): 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938.

- Dagkas, S. 2007. “Exploring Teaching Practices in Physical Education with Culturally Diverse Classes: A Cross-Cultural Study.” European Journal of Teacher Education 30 (4): 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760701664219.

- Dagkas, S., T. Benn, and H. Jawad. 2011. “Multiple Voices: Improving Participation of Muslim Girls in Physical Education and School Sport.” Sport, Education and Society 16 (2): 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.540427.

- Dixon, K., S. Braye, and T. Gibbons. 2022. “Still Outsiders: The Inclusion of Disabled Children and Young People in Physical Education in England.” Disability & Society 37 (10): 1549–1567. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1907551.

- Doolittle, S. A., P. B. Rukavina, W. Li, M. Manson, and A. Beale. 2016. “Middle School Physical Education Teachers’ Perspectives on Overweight Students.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE 35 (2): 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0178.

- Elmore, R. F. 2002. Bridging the Gap between Standards and Achievement: The Imperative for Professional Development in Education. Washington DC: Albert Shanker Institute.

- European Agency. 2015. Consolidated Annual Activity Report of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. https://doi.org/10.2811/045913

- Fejgin, N., R. Talmor, and I. Erlich. 2005. “Inclusion and Burnout in Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 11 (1): 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×05049823.

- Filipčič, T., M. Burin, and B. Leskošek. 2021. “Teachers’ Beliefs Regarding Teaching Students with Visual Impairments in Physical Education.” Kinesiologia Slovenica 27 (2): 143–154. https://doi.org/10.52165/kinsi.27.2.143-154.

- Fitzgerald, H. 2012. “‘Drawing’ on Disabled Students’ Experiences of Physical Education and Stakeholder Responses.” Sport, Education and Society 17 (4): 443–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.609290.

- Fitzpatrick, K. 2018. “What Happened to Critical Pedagogy in Physical Education? An Analysis of Key Critical Work in the Field.” European Physical Education Review 25 (4): 1128–1145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18796530.

- Flintoff, A., and F. Dowling. 2019. “‘I Just Treat Them all the Same, Really’: Teachers, Whiteness and (Anti) Racism in Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (2): 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1332583.

- Florian, L. 2014. “What Counts as Evidence of Inclusive Education?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.933551.

- Furuta, Y., T. Sato, R. T. Miller, C. Kataoka, and T. Tomura. 2022. “Public Elementary School Teachers’ Positioning in Teaching Physical Education to Japanese Language Learners.” European Physical Education Review 28 (4): 1006–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×221104912.

- Grenier, M. A. 2011. “Coteaching in Physical Education: A Strategy for Inclusive Practice.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly: APAQ 28 (2): 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.28.2.95.

- Haegele, J. A., and L. J. Lieberman. 2016. “The Current Experiences of Physical Education Teachers at Schools for Blind Students in the United States.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 110 (5): 323–334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145482X1611000504.

- Haegele, J. A., W. J. Wilson, X. Zhu, J. J. Bueche, E. Brady, and C. Li. 2021. “Barriers and Facilitators to Inclusion in Integrated Physical Education: Adapted Physical Educators’ Perspectives.” European Physical Education Review 27 (2)): 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×20944429.

- Haegele, J., X. Zhu, and S. Davis. 2018. “Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Education Participation for Students with Disabilities: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (2): 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1362046.

- Hattie. 2009. Visible Learning, a Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement: Education, Education. Cram101.

- Hersman, B. L., and S. R. Hodge. 2010. “High School Physical Educators’ Beliefs About Teaching Differently Abled Students in an Urban Public School District.” Education and Urban Society 42 (6): 730–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124510371038.

- Hodge, S., J. O. A. Ammah, K. M. Casebolt, K. LaMaster, B. Hersman, A. Samalot-Rivera and T. Sato. 2009. “A Diversity of Voices: Physical Education Teachers' Beliefs About Inclusion and Teaching Students with Disabilities.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 59 (4): 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120903306756.

- Hodge, S., J. Ammah, K. Casebolt, K. Lamaster, and M. O’Sullivan. 2004. “High School General Physical Education Teachers’ Behaviors and Beliefs Associated with Inclusion.” Sport, Education and Society 9 (3): 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320412331302458.

- Hodge, S. R., J. Haegele, P. Gutierres Filho, and G. Rizzi Lopes. 2018. “Brazilian Physical Education Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching Students with Disabilities.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 65 (4): 408–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2017.1408896.

- Hodge, S. R., T. Sato, A. Samalot-Rivera, B. L. Hersman, K. LaMaster, K. M. Casebolt, and J. O. A. Ammah. 2009. “Teachers’ Beliefs on Inclusion and Teaching Students with Disabilities: A Representation of Diverse Voices.” Multicultural Learning and Teaching 4 (2), https://doi.org/10.2202/2161-2412.1051.

- Hong, Q. N., P. Pluye, S. Fàbregues, G. Bartlett, F. Boardman, M. Cargo, P. Dagenais, et al. 2018 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018. Pbworks.com. Accessed 25 October 2023. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf.

- Hunter, S., S. T. Leatherdale, K. Storey, and V. Carson. 2016. “A Quasi-Experimental Examination of how School-based Physical Activity Changes Impact Secondary School Student Moderate- to Vigorous- Intensity Physical Activity over time in the COMPASS Study.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13 (1): 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0411-9.

- Hutzler, Y., and S. Barak. 2017. “Self-efficacy of Physical Education Teachers in Including Students with Cerebral Palsy in Their Classes.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 68: 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.07.005.

- Juvonen, J., L. M. Lessard, R. Rastogi, H. L. Schacter, and D. S. Smith. 2019. “Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities.” Educational Psychologist 54 (4): 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645.

- Kefallinou, A., S. Symeonidou, and C. J. W. Meijer. 2020. “Understanding the Value of Inclusive Education and Its Implementation: A Review of the Literature.” Prospects 49 (3–4): 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09500-2.

- Kirk, D. 2010. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge.

- Ko, B., and B. Boswell. 2013. “Teachers’ Perceptions, Teaching Practices, and Learning Opportunities for Inclusion.” Physical Educator 70 (3): 223–242.

- Larsson, H., B. Fagrell, and K. Redelius. 2009. “Queering Physical Education. Between Benevolence Towards Girls and a Tribute to Masculinity.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 14 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980701345832.

- Lleixà, T., and C. Nieva. 2020. “The Social Inclusion of Immigrant Girls in and Through Physical Education. Perceptions and Decisions of Physical Education Teachers.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (2): 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1563882.

- Majoko, T. 2019. “Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Physical Education in Zimbabwean Primary Schools.” SAGE Open 9 (1): 2158244018820387. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018820387.

- Makopoulou, K. 2018. “An Investigation into the Complex Process of Facilitating Effective Professional Learning: CPD Tutors' Practices under the Microscope.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (3): 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1406463.

- Makopoulou, K. 2009. Continuing Professional Development for Physical Education Teachers in Greece: Towards Situated, Sustained and Progressive Learning? [Doctoral dissertation, Loughborough University].

- Makopoulou, K., D. Penney, R. Neville. 2022. “What Sort of ‘inclusion’ is Continuing Professional Development Promoting? An Investigation of a National CPD Programme for Inclusive Physical Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 26 (3): 245–262.

- Martínez-López, E. J., N. Zamora-Aguilera, A. Grao-Cruces, and M. J. De la Torre-Cruz. 2017. “The Association Between Spanish Physical Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Expectations and Their Attitudes Toward Overweight and Obese Students.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 36 (2): 220–231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0125.

- McGrath, O., S. Crawford, and D. O’Sullivan. 2019. ““It’s a Challenge”: Post Primary Physical Education Teachers’ Experiences of and Perspectives on Inclusive Practice with Students with Disabilities.” European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity 12 (1): 2. https://doi.org/10.5507/euj.2018.011.

- Mihajlovic, C. 2019. “Teachers’ Perceptions of the Finnish National Curriculum and Inclusive Practices of Physical Education.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 10 (3): 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2019.1627670.

- Mirza, S. 2023. Introducing intersectionality: In conversation with Heidi Safia Mirza [podcast]. https://www.bera.ac.uk/media/introducing-intersectionality-in-conversation-with-heidi-safia-mirza#:~:text=Introducing%20Intersectionality%3A%20In%20conversation%20with%20Heidi%20Safia%20Mirza

- Miyauchi, H. 2020. “A Systematic Review on Inclusive Education of Students with Visual Impairment.” Education Sciences 10 (11): 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110346.

- Morley, D., R. Bailey, J. Tan, and B. Cooke. 2005. “Inclusive Physical Education: Teachers’ Views of Including Pupils with Special Educational Needs and/or Disabilities in Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 11 (1): 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336(05049826.

- Morley, D., T. Banks, C. Haslingden, B. Kirk, S. Parkinson, T. Van Rossum, I. Morley, and A. Maher. 2021. “Including Pupils with Special Educational Needs and/or Disabilities in Mainstream Secondary Physical Education: A Revisit Study.” European Physical Education Review 27 (2): 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×20953872.

- Morrison, H. J., and D. Gleddie. 2021. “Interpretive Case Studies of Inclusive Physical Education: Shared Experiences from Diverse School Settings.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (4): 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1557751.

- Nanayakkara, S. 2022. “Teaching Inclusive Physical Education for Students with Disabilities: Reinvigorating In-Service Teacher Education in Sri Lanka.” Sport, Education and Society 27 (2): 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1964462.

- Nieva Boza, C., and T. Lleixà i Arribas. 2018. “Inclusión de las Niñas Inmigrantes y Creencias del Profesorado de Educación Física [Inclusion of Immigrant Girls and Beliefs of Physical Education Teachers].” Apunts Educació Física i Esports 134: 69–83. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2018/4).134.05.

- Obrusnikova, I. 2008. “Physical Educators’ Beliefs About Teaching Children with Disabilities.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 106 (2): 637–644. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.106.2.637-644.

- Obrusnikova, I., and S. R. Dillon. 2011. “Challenging Situations When Teaching Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders in General Physical Education.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly: APAQ 28 (2): 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.28.2.113.

- O’Connor, J. 2016. “The Development of the Stereotypical Attitudes in HPE Scale.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (7): 69–80.

- O’Connor, U., and J. McNabb. 2021. “Improving the Participation of Students with Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Physical Education Classes: A Rights-Based Perspective.” Educational Studies 47 (5): 574–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1719385.

- Odum, M., C. W. Outley, E. L. J. McKyer, C. A. Tisone, and S. L. McWhinney. 2017. “Weight-related Barriers for Overweight Students in an Elementary Physical Education Classroom: An Exploratory Case Study with One Physical Education Teacher.” Frontiers in Public Health 5: 305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00305.

- Overton, H., A. Wrench, and R. Garrett. 2017. “Pedagogies for Inclusion of Junior Primary Students with Disabilities in PE.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (4): 414–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2016.1176134.

- Papageorgiou, E., N. Digelidis, I. Syrmpas, and A. Papaioannou. 2021. “A Needs Assessment Study on Refugees’ Inclusion Through Physical Education and Sport. Are We Ready for This Challenge?” Physical Culture and Sport Studies and Research 91 (1): 21–33. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2021-0016.

- Patey, M., Y. J. Byoungwook Ahn, W. Lee, and K. J. Yi. 2019. ““For Everyone, but Mission Impossible:” Physical and Health Educators’ Perspectives on Inclusive Learning Environments.” Journal of Physical Education and Sport 19 (4): 2477–2483. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2019.04376.

- Patey, M. J., Y. Jin, B. Ahn, W.-I. Lee, and K. J. Yi. 2021. “Engaging in Inclusive Pedagogy: How Elementary Physical and Health Educators Understand Their Roles.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 27 (14): 1659–1678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1916102.

- Penney, D., R. Jeanes, J. O’Connor, and L. Alfrey. 2018. “Re-theorising Inclusion and Reframing Inclusive Practice in Physical Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (10): 1062–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1414888.

- Petrie, Kirsten, J. Devcich, and H. Fitzgerald. 2018. “Working Towards Inclusive Physical Education in a Primary School: ‘some Days I Just Don’t get it Right’.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (4): 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1441391.

- Philpot, R., W. Smith, G. Gerdin, L. Larsson, K. Schenker, S. Linnér, K. M. Moen, and K. Westlie. 2021. “Exploring Social Justice Pedagogies in Health and Physical Education through Critical Incident Technique Methodology.” European Physical Education Review 27 (1): 57–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20921541.

- Pocock, T., and M. Miyahara. 2018. “Inclusion of Students with Disability in Physical Education: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (7): 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412508.

- Pollock, D., M. D. J. Peters, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, L. Alexander, A. C. Tricco, C. Evans, et al. 2023. “Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 21 (3): 520–532. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-22-00123.

- Qi, J., and A. S. Ha. 2012. “Inclusion in Physical Education: A Review of Literature.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 59 (3): 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2012.697737.

- Qi, J., L. Wang, and A. Ha. 2017. “Perceptions of Hong Kong Physical Education Teachers on the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 37 (1): 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2016.1169992.

- Ramberg, J., and A. Watkins. 2020. “Exploring Inclusive Education Across Europe: Some Insights from the European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education.” FIRE Forum for International Research in Education 6 (1): 85–101. https://doi.org/10.32865/fire202061172.

- Rekaa, H., H. Hanisch, and B. Ytterhus. 2019. “Inclusion in Physical Education: Teacher Attitudes and Student Experiences. A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 66 (1): 36–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2018.1435852.

- Rojo-Ramos, J., F. Manzano-Redondo, J. C. Adsuar, Á Acevedo-Duque, S. Gomez-Paniagua, and S. Barrios-Fernandez. 2022. “Spanish Physical Education Teachers’ Perceptions About Their Preparation for Inclusive Education.” Children (Basel, Switzerland) 9 (1): 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9010108.

- Rowan, L., T. Bourke, L. L’Estrange, J. Lunn Brownlee, M. Ryan, S. Walker, and P. Churchward. 2021. “How Does Initial Teacher Education Research Frame the Challenge of Preparing Future Teachers for Student Diversity in Schools? A Systematic Review of Literature.” Review of Educational Research 91 (1): 112–158. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320979171.

- Rukavina, P., S. Doolittle, W. Li, A. Beale-Tawfeeq, and M. Manson. 2019. “Teachers’ Perspectives on Creating an Inclusive Climate in Middle School Physical Education for Overweight Students.” The Journal of School Health 89 (6): 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12760.

- Rukavina, P. B., S. Doolittle, W. Li, M. Manson, and A. Beale. 2015. “Middle School Teachers’ Strategies for Including Overweight Students in Skill and Fitness Instruction.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE 34 (1): 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2013-0152.

- Slee, R., and J. Allan. 2001. “Excluding the Included: A Reconsideration of Inclusive Education.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 11 (2): 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210100200073.

- Smith, A. 2004. “The Inclusion of Pupils with Special Educational Needs in Secondary School Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 9 (1): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898042000208115.

- Tarantino, G., K. Makopoulou, and R. D. Neville. 2022. “Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities in Physical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Teachers’ Attitudes.” Educational Research Review 36: 100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100456.

- Thomas, G. 2022. How to do Your Research Project: A Guide for Students. 4th ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850.

- Tristani, L., S. Sweet, J. Tomasone, and R. Bassett-Gunter. 2022. “Examining Theoretical Factors That Influence Teachers’ Intentions to Implement Inclusive Physical Education.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 93 (3): 564–577.

- UNESCO. 2015. Quality Physical Education Guidelines for Policy-Makers. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 2017. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- United Nations. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/sdgs-17-goals-transform-world.

- Valley, J. A., and K. C. Graber. 2017. “Gender-biased Communication in Physical Education.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE 36 (4): 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0160.

- Van Doodewaard, C., and A. Knoppers. 2018. “Perceived Differences and Preferred Norms: Dutch Physical Educators Constructing Gendered Ethnicity.” Gender and Education 30 (2): 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1188197.

- Wagner, I., F. Bartsch, and B. Rulofs. 2018. “Physical Education Teachers’ Self-Perceived Needs for Support in Dealing with Student Heterogeneity in Germany.” International Sports Studies 40 (1): 6–18. https://doi.org/10.30819/iss.40-1.02.

- Wang, L., J. Qi, and L. Wang. 2015. “Beliefs of Chinese Physical Educators on Teaching Students with Disabilities in General Physical Education Classes.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly: APAQ 32 (2): 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1123/APAQ.2014-0140.

- Wang, L., M. Wang, and H. Wen. 2015. “Teaching Practice of Physical Education Teachers for Students with Special Needs: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour.” International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education 62 (6): 590–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2015.1077931.

- Warnes, E., E. J. Done, and H. Knowler. 2022. “Mainstream Teachers’ Concerns About Inclusive Education for Children with Special Educational Needs and Disability in England Under Pre-Pandemic Conditions.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs: JORSEN 22 (1): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12525.

- Wilson, W. J., L. E. Kelly, and J. A. Haegele. 2020. “‘We’re Asking Teachers to do More with Less’: Perspectives on Least Restrictive Environment Implementation in Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (9): 1058–1071. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1688279.

- Wilson, W. J., E. A. Theriot, and J. A. Haegele. 2020. “Attempting Inclusive Practice: Perspectives of Physical Educators and Adapted Physical Educators.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 11 (3): 187–203.

- Zingg, W., E. Castro-Sanchez, F. V. Secci, R. Edwards, L. N. Drumright, N. Sevdalis, and A. H. Holmes. 2016. “Innovative Tools for Quality Assessment: Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs (ICROMS).” Public Health 133: 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.10.012.