ABSTRACT

This article explores the position of ethnomusicologists approaching the field with the prior lived experience of being a working/proficient musician, meeting other fellow musicians in all the complexity of each person’s multi-layered background. Within these layers, musical practice and the experience of musicking are central to the relationships created between these individuals. The various case studies put forward in the paper bring to the fore how proficient musician-researchers have used their musical skills to negotiate fieldwork, integrating it as a central part of their process. Musical ability, central to their identity as an individual, becomes an additional layer that has arguably enabled musician-ethnomusicologists to access communities on a level where the latter are able to actively work with them, assigning them roles that can satisfy both parties and lead to what is presented as ‘applied relationships’. The article makes the case that the musician-ethnomusicologist’s creative practice, while not directly leading to REF outputs and therefore remaining an unspoken activity, is intricately entwined with their research activity.

Introduction

This article is not about learning to perform in the field, nor is it about acquiring enough fluency to be able to understand the ‘other’ musical culture.Footnote1 It is about the ethnomusicologist approaching the field with the prior lived experience of being a musician with generative or productive competence (Tokita Citation2014),Footnote2 meeting other fellow musicians in all the complexity of each person’s multi-layered background. Within these layers, musical practice and the experience of musicking are central to the relationships created between these musicians. As Baily pointed out in the conclusion of his seminal article outlining the benefits of performing in the field, ‘[b]eing able to play [the music] gave [him] an immediate and large area of common experience with people to whom [he] was a complete stranger’ (Citation2001: 96). This ‘form[ed] the basis for social relationships’ (ibid.), developed from a shared sense of understanding and belonging. I argue that when these prerequisite credentials of musical proficiency and shared common experiences are met and understood, the ethnomusicologist shifts into a space where they may not be musicking at all – although this may, as we will see, be required –, but will instead integrate a meaningful role that is useful to the community as it is able to mould the newcomer within their frame of reference. Using case studies taken from my personal fieldworkFootnote3 but also from several other colleagues in this position (Tsioulakis, Flood, Maher), I discuss how relationships are navigated and how the interaction of musicians with equal levels of competence in different but affiliated cultures can pave the way for meaningful reciprocal relationships that enable the agency of the community chosen by the researcher.

The musician-ethnomusicologist and REF – a personal experience

During my doctoral studies, I always felt a twinge of disappointment when hearing ethnomusicologists who I knew were high level performers say something along the lines of: ‘I would love to play more but have decided to focus on academia for the time being’. My musical activity was central to my identity – I started music at the age of three and went on to train in the conservatoire before starting my own bands and participating in international tours –; it was also, at the time, one of my main sources of income during a self-funded PhD. Dependent on music both socially and financially, I was unable to comprehend this statement. Fast forward four years to a full-time lecturing position in a new department, and I was increasingly able to appreciate my colleagues’ remarks. The administrative burden and demand on one’s time as an academic in a British institution, especially one principally focused on teaching, leaves little space for artistic activity, let alone new creativity. Determined to continue my practice, until the pandemic effectively shut down all forms of live entertainment, I spent my weekends on trains travelling to concerts (clubs, concert halls, weddings, private parties) and used most of my annual leave to tour. Managing to keep burnout at arm’s length, I was unwilling to fully give in to the considerably less artistically stimulating HE institutional environment.

My dual practice, which I publicly assumed, did however sow confusion. Following an unsuccessful job application, a well-meaning senior colleague asked me where I placed my research. I did not understand the question and went into the detail of my research content. He stopped me and asked me the question again: are you a researcher or are you placing yourself as a practice-based researcher? I was thrown off balance and hastily confirmed that I was a researcher. His confusion – as that of other colleagues who assume that my work focuses on practice-based research – might have been fed by my visibility as a performer in the academic world. I perform willingly at gatherings and conferences, blurring the boundaries between my artistic practice and my research. Personally, however, these are distinct. My doctoral studies were in a field that was slightly removed from my artistic practice. I was a classically trained early-music baroque recorder player and a Galician/French bagpipe player, but I chose to focus on Mallorcan pipes, a musical scene little known beyond the Catalan area. My ability to access Mallorcan music and its social realm was facilitated thanks to an understanding of other French and Spanish bagpipe cultures as well as a proficiency in instruments close to its tradition. These informed my research and were key to my status in the field, but Mallorcan bagpipe practice was, as I detail below, not central to my fieldwork or to my fieldplay.

I was in a similar position for my postdoctoral studies. With a team of acousticians, we looked into the mechanical movement of the bagpiper’s arm (Balosso-Bardin et al. Citation2018). While the topic was strongly led by my experience as a piper, and I was used as a subject in our protocol experiments, my creative practice as a musician was not examined. Rather, it served as a way to instigate and guide the research, working then with other musicians for the conclusive experiments. Had I not been a proficient piper, this research would not have been possible, as no one else on the team was a piper nor aware of the subtleties of the instrument when playing it: in other words, music competency triggered the questions that led to the award-winning research.

This separation between research and creative practice meant that I was able to retain a certain degree of artistic freedom, removed from theoretical concerns of authenticity that could stifle creative innovation. Since my doctorate, I have written a couple of articles directly linked to my practice (Balosso-Bardin Citation2016 and Citation2018). However, unlike ethnomusicologists who focus on performance as their object of study and use their practice as an investigative tool (for example, Kim Citation2014), I have used my musical practice as a way to continue building my presence in the musical world as a legitimate and recognised musician.

This activity, whilst central to my academic practice thanks to the advantages it brings (as described below), is impossible to translate within the Research Excellence Framework (REF). While it is a real bonus for the institution, my professional musical activity (albums, concerts, tours) is invisible within REF. As a musician-ethnomusicologist who has chosen a research profile within their institution and academic community, my activity remains, to paraphrase Witzleben (Citation2010), in the shadows, even as I use it almost constantly to build relationships – whether in the field or at home –, inform my reasoning and instigate new research projects.

I am not alone in this predicament. Ethnomusicologist Ioannis Tsioulakis is also a trained jazz pianist who studied and played in Greece before looking in depth into the Athenian working musician scene. Despite the centrality of his musical activity as a working musician with his own recordings and activity to the field and to his research, these remain hidden. While continuing a professional practice throughout his academic career, Tsioulakis chose not to include any of his artistic output in REF or for any internal assessments. His reasoning was twofold: first, he assumed that music academia ‘does not fully appreciate creative output unless it is intricately connected to funding streams, publications, and/or formal events that enjoy academic prestige’ (pers. comm. 2021), and secondly, in framing his performance as academic output, he would be bringing together two worlds that are currently compartmentalised. Tsioulakis experiences his practice as a personal and enjoyable activity, important for his wellbeing; if it was directly associated to his work environment, it would become less pleasurable and effective (pers. comm. 2021). Tsioulakis’ practice, however, is invaluable to the field of research as it provides experiential knowledge that cannot easily be dismissed. Furthermore, the impact of his work is undeniable and has led him to lead conversations with musicians, unions and arts organisations during times of hardship such as the current artistic crisis triggered by the pandemic. While difficult to quantify in terms of REF, especially when such activity comes at the end of a reporting cycle, Tsioulakis’ research and presence in the field is undeniably strong and extremely necessary, and the fruit of his status both as a musician and researcher.

Through this article, I am arguing that while an musician-ethnomusicologist may have chosen a certain route, privileging the written word as an output for their career advancement, musical practice is at the heart of the research process. The various examples I put forward in the following pages, bring to the fore how proficient musician-researchers have used their musical skills to negotiate fieldwork, integrating it as a central part of their process. The musical ability, central to their identity as an individual, becomes an additional layer that, I argue, has enabled them to access communities on a level where the latter are able to actively work with them within a role that can satisfy both parties and lead to what I call ‘applied relationships’.

Breaking into the field: using the emic-etic continuum

As shown above, fieldplay can become crucial to how an ethnomusicologist is viewed and how it defines their relationship with local musicians as well as internationally. Bringing musical ability into the field impacts these relationships and possibly even the knowledge we are able to capture. Indeed, Titon posits that if ‘knowledge is experiential and the intersubjective product of our social interactions, then what we can know arises out of our relations with others’ (Titon Citation2008: 33). In other words, musical interaction with the field will impact our knowledge, and different sorts of musical interactions will modify it. Therefore, entering the field with mature musical knowledge (encompassing labour-related experiences) relevant to that field might reveal elements that might not have been accessible otherwise. Similarly, the retainer of this knowledge may develop a different relationship with the musicians they are interacting with. I now wish to turn my attention to how these relationships might change when one enters a field as a competent musician.

In order to illustrate this, I will use my personal experience in the field through which I argue that, had I not been a professionally active and competent musician prior to my arrival, my interaction with locals might have been very different, and indeed much more superficial and shallow. It is, of course, difficult to prove the opposite, and my musical background was completed with essential linguistic skills that were both acquired prior to the field (Castilian) and in the field (Catalan). However, the less satisfying experience of anthropological colleagues on the island within the same communities demonstrated that I had been able to access a status that enabled the development of a higher degree of friendship and trust. Interestingly, my experience highlighted that whilst being musically able was necessary to break into the field and maintain a position of legitimacy, it subsequently became secondary to my practice as a researcher.

As a doctoral student, I actively pursued music-making as it became my main source of income for five years. I was involved in several musical spheres, and developed a cosmopolitan network of bands and projects. A classically trained musician specialised in Early Music, I then developed a presence on the French and British folk scenes playing the bagpipes and the recorders. I brought an ‘international’ aspect to various projects, and was sought out by musicians who wanted to work with other folk music traditions. This resulted in a series of semi-permanent positions within fluctuating bands, as I played for projects including Greek folk, Senegalese fusion, Blues, Ceilidh, Turkish music, as well as a selection of other Euro-folk styles. I also incorporated a few established bands which became my main musical outlets, including the UK’s only pizzica and tarantella band (Amaraterra), the international Världens Band (see Balosso-Bardin Citation2018) and my own duet with then fellow musician/PhD student Phil Alexander. Few were aware that I was also an ethnomusicologist, and when they were, the topic of my research – the Mallorcan bagpipes – was so removed from my musical activity that it became insignificant. My principal social role was that of an international, collaborative folk musician. Music was a means to make ends meet, and performing to a high standard was necessary to maintain work and a reputation. I was, in Tsioulakis’ definition, mainly a ‘working musician’ (Citation2020b), and in a good position to enter the field with the experiential knowledge of one.Footnote4

Before arriving in Mallorca, I had established some connections with local musicians and cultural activists. I was in touch with the most prominent piper of the island, one amateur group and one arts patron. All three were welcoming and encouraging regarding my interest for the topic and a preliminary visit solidified these links, especially when I demonstrated I could play the Mallorcan bagpipes (xeremies) to the group. They were delighted by my ability to play their instrument and a song from their repertoire and amused by my clumsiness as it was the first time I held the unwieldy xeremies; I was more accustomed to the smaller Galician gaita, which has similar fingering, allowing me to transpose my embodied knowledge onto the xeremies at a moment’s notice. As I planned my fieldwork, I considered positioning myself as a student by attending the conservatoire, but quickly abandoned the idea, mainly due to the absence of response from the institution, notorious for its slow administration. After reflection, I decided that this would have been artificial, as I did not necessarily want to establish a student/master relationship with the musicians I was interacting with. Similarly, I had imagined that I would join the group rehearsals of the amateur band. While I was invited to attend rehearsals every week, I quickly realised that my participation was not particularly desired, even if my musical competence was sufficient. Over time, however, these bands counted on the fact that I was able to play and had absorbed their repertoire in order to ask me to join them for performances once in a while, either to ‘give me a taste’ or as an honorific position at public piping events, strategically setting them apart from other groups who did not have a special guest. In Mallorca, as I came to learn, learning not to play until one was specifically invited to, was just as important as knowing how to play.

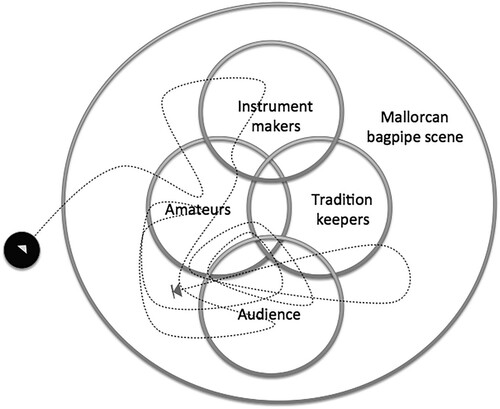

Within the first two months, I had come into contact with a fair number of musicians, instrument makers and local cultural actors. I was attending weekly rehearsals, going to concerts and conducting the odd interview as well as learning Catalan, the main language spoken by the musicians. I was interacting with the Mallorcan bagpipe scene, but the core of the field was eluding me. I had not accounted for the fact that the musical scene was strongly coded nor that there were no impromptu music-making sessions one could attend. Informal social occasions were held behind closed doors, making it difficult for a newcomer, even as a musician, to find a way in. Mallorcan music groups have defined membership, often operating with strict rules of belonging. The traditional duets are formed through mutual affinity or family connections and are lifetime partnerships that cannot be expanded. Conjointly, amateur village groups often – but not always – operate on local membership, with some requiring members to be residents in order to limit numbers and create a stronger identity. As a result, I was shut out from any form of participation. Additionally, as a newcomer, I did not know how to meet younger musicians, with whom I stood a better chance of becoming friends and I was politely ignored when I tried speaking to a couple of musicians after concerts whether I introduced myself as a musician or a researcher. I was socially isolated, detached from the musical world I sought entry into and remained very much in the peripheral position of the observer ().

This position shifted overnight when I played a Euro-folk concert with my trio. I was invited by Toni Torrens, one of the most active patrons of the arts in Mallorca, to perform at a bagpipe gathering he organised every year in the village of Sa Pobla. Sundays were dedicated to an instrument fair, processions, jamming in the square and a communal bagpiper’s lunch, but Saturday evenings featured musicians from Mallorca and Europe. When Toni asked me to play, it was a win, win solution. I was local but represented France and could easily provide him with an international trio, which saved him time, effort and money (after this concert, I assumed the role of an agent for several years, sending my international piping friends to Mallorca for these concerts). On the other hand, this was an excellent opportunity to play for a large audience of local folk musicians, many of whom I had never met before. Also on the bill were a group of Sicilians and a local duo of older pipers who had just published a new album with fascinating archival recordings.

Just before playing, I said a few words in Catalan and then went on to explain in Castilian the reason for which I was in Mallorca. I was here to study the xeremies and was very grateful for the opportunity to play that evening. Accompanied by a Catalan accordionist and a Swedish double bass player, we played several European folk tunes showcasing the recorders and bagpipes, instruments that were well known to the audience. The concert was a success and our set was said to have been carried out ‘with great mastership and sensitivity’ (Genovart Espinosa Citation2012, 20). These few Catalan words coupled with my ensuing demonstration of musicianship led to many conversations, as I was introduced to people who congratulated me, and, crucially, invited me to come and see a show, join a rehearsal, or meet their musical children who were around my age. As these contacts materialised into friendships and lasting relationships, I was able to establish a meaningful relationship with the field, oscillating between the role of researcher and performer over the year (Balosso-Bardin Citation2016).

The initial indifference and maybe even resistance I had found during the first few months of fieldwork was understandable. I was an unidentified person, randomly asking questions about bagpipes, with no real place within the host community. My claims to musicianship were unverifiable and I filled no useful role, as ethnomusicologists are not common in Mallorca, where mass tourism, combined with a closed insular society, has made locals wary of foreigners (see Waldren Citation1996). The last ‘forraster’ or ‘foreigner/outsider’ who had written about Mallorcan musical traditions to any extent was the Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria, who published his encyclopaedia of the Balearic Islands in Citation1897.

One of the invitations I received following the performance was to attend a drum making workshop along with some other young musicians, who I later understood were considered as the core revivalists’ main apprentices and have since become central to Mallorca’s folk music scene. When the younger musicians headed back to the city, I asked if I could stay with drum maker and xeremies player, Miquel Tugores and the afternoon extended into a series of discussions about bagpipes, demonstrations on local cane flutes that he handed me to try out and comment upon the quality of sound, and a tour of his workshop. Years of experience as a woodwind player, trawling through early music instrument exhibitions as well as instrument making workshops meant that I could engage with the material objects and form a musician/instrument-maker bond, as we both appreciated the skill of the other. These relationships with the material musical world continued to develop throughout the years, as my recorder playing skills were valued by other Mallorcan instrument makers who occasionally turned towards me to comment upon the accuracy of their instruments. A few hours later, Tugores offered to drive me back to Palma. On the way back, he turned towards me and said: ‘Now I know. You are part of the club.’ I asked him to clarify. He told me that initially, he didn’t know what I would turn out to be. A young woman from abroad who played music was one thing. But I had volunteered to stay alone with a near stranger in order to learn more about his trade and knowledge. We had exchanged for a whole afternoon on traditions and tried out local instruments, connecting through stories and music. He had recognised our ‘common experience’ (Baily Citation2001: 96), which meant that we were able to connect despite being strangers; we had similar experiences in related musical traditions and were able to connect not only through music-making but also through the material objects, contextualising them within culture and society. I was, therefore, like them, part of ‘the club’ and from then on was treated much in the same way as their other younger apprentices. This included invitations to watch them play, be part of their social circle and, once in a while, play with them.

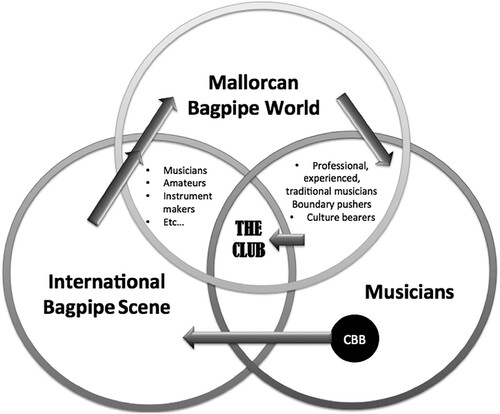

Importantly, being ‘part of the club’ did not mean being part of the larger Mallorcan piping world. The club was an intercultural affinity group (Slobin Citation1993) that could be defined here as the wider community of musicians and instrument makers fascinated by bagpipe music, culture and materiality. The club Tugores alluded to was the intersection of people who shared experiential knowledge about the wider traditional musical world in which they were embedded, incorporating an inherent knowledge of and interest for social and cultural codes, beyond the specificities of each locality. Titon conceptualises this complicity as a ‘subject shift’ (Citation1995: 291); the informant brings the fieldworker into their world, especially in the face of a third party. Interestingly, many of the subject shifts Titon explores happen through experiences peripheral to the act of direct music-making such as conversations or moments of intense emotion. While the situation with Tugores did not involve a physical third party, he was very clearly alluding to a category of musicking that did not have the necessary tools and understanding to access this specific club. As such, he was accepting the fact that I belonged to the same world as he did, thanks to parallel experiences that allowed us to understand each other beyond the surface of language and information exchange. The gap had been bridged through several activities and led Tugores as well as the inner circle of the Mallorcan traditional musicians to recognise, as Titon puts it, that ‘one’s experience resembles the other's-that the inner experience corresponds to and complements the outer’ (Citation1995, 296). Alongside the musicians, instrument makers and cultural activists, the club had just accepted the membership of a musician-ethnomusicologist. ().

These rites of passage have been described several times by ethnomusicologists (Baily Citation2001; Kippen Citation2008; Rice Citation2008). What was significant here was that the subject shift allowed me to become a full member of the inner circle of the Mallorcan bagpiping community without having played a single note of Mallorcan music.

I had become part of the club through three events.

I demonstrated my musical skills in a public concert, shifting into the position of a competent and working musician.

I demonstrated an intimate, lived understanding of parallel traditions supported by credentials and experience as an encultured musician within a wider but connected musical scene.

I was able to interact with the material musical instruments as an expert, reinforcing a recognisable professional bond.

Negotiating fieldplay: expectations and threat

The arrival of a new and possibly ‘exotic’ musician with previously acquired skills on the field may trigger a range of different reactions and expectations. Liza Sapir Flood, for example, realised that as a competent fiddler, her musicianship came along with a set of musical responsibilities that forced her to become an active member of the musical community (Citation2017). Despite her initial reluctance, her participation was unavoidable and was coupled with a tacit allegiance to one of the principal fiddlers who informally but effectively apprenticed her. It was inconceivable that, as someone who knew the repertoire and had engaged with similar music before, she could just step aside and deprive them from her fiddling skills. Flood’s initial but short-lived resistance came from a personal expectation that her academic activity might be separated from her musical identity, allowing her to maintain a ‘marginal presence suited for observation and contemplation’ (Flood Citation2017, 492). This desire to blend in the background, however, was not accepted by the community and may, indeed, be difficult in any situation where a new person enters the scene. Nor is invisibility necessarily desirable. Indifference, as I initially experienced, was more difficult to manage than curiosity or even suspicion. Cooley and Barz describe fieldwork as ‘the process during which the ethnomusicologist engages living individuals as a means toward learning about a given music-cultural practice’ (Citation2008: 4, author’s emphasis). Positive or negative reactions are social interactions, which, as human beings, we can respond to in a range of ways, but a lack of engagement is difficult to work with. Flood’s experience demonstrates that the musical community we, as researchers, hope to engage with has a certain amount of agency when it comes to defining the nature of this engagement. Furthermore, when the researcher is also recognised as a competent musician, fluent in local cultural and labour-related codes, social interactions happen on a deeper and more meaningful level, and take into account mutually recognised lived experiences.

However, the host community may not perceive previously acquired skills and fluency in the musical genre positively and the musician-ethnomusicologist might be perceived as a threat. Ethnomusicologist Nicola Maher, for example, is an excellent clarinettist who spent many months over several years in a small northern Greek village. Maher was an active performer in London, playing with Turkish and Greek bands, learning repertoire and style within the diaspora and identified as a professional musician. She started visiting the village a few years before beginning her research, mainly to improve her Greek playing style and initially positioned herself as a student. Unlike Flood, Maher’s musical circle was formed of musicians who played professionally and relied on their music-making to make an income. Her ability to pick up music quickly was noticed, and Maher reflected that a beginner in the instrument might have not been met with so much wariness:

To begin with, they were worried, because they thought I was going to take their jobs. That created a barrier between them. I remember … [walking] past [one of my teachers in the village] and he said [tongue in cheek] ‘we’ve got to watch this one, she picks things up really quickly, she might take our jobs’. A beginner would not have that issue. (Maher, interview Citation2019)

A further barrier to Maher’s inclusion within the community was her exceptional status as a woman playing the clarinet, traditionally a male instrument in Epirus (Maher Citation2019: 47). While her musical skills were useful to establish a connection with the musicians, her performance did not actually give her an insight about the life of the musicians as her exceptionalism got in the way:

[My performance practice didn’t] exactly give an insight into their experience as a musician. The reaction to me was completely different. I was a strange novelty, a woman, British, playing the klaríno. I was treated kind of like this amazing phenomenon. I was playing three songs, and these guys play for hours and hours and hours and were taken for granted. The reaction of the audience was disproportionate compared to what I did and the skills they had. (Maher, interview 2019)

This position, as ‘an “outsider” musician in the field’ (Maher Citation2019: 48), despite having the relevant musical expertise, was delicate. On the one hand, Maher conceded that her heightened understanding of music and musicianship, and specifically that of the area she was researching, ‘offered [her] some unique insights that may otherwise have been missed’ (Citation2019: 44), on the other hand she was navigating relationships and personal identities according to the situation, attempting to maintain relationships with the musicians without alienating them.

Her identity as a researcher was slowly established once she decided to study this music for her PhD, after having interacted with the community for a few years. But her identity as a musician was firmly anchored:

To begin with, it actually worried me. (…) I couldn’t break out of identity as a clarinettist. Then I realised it didn’t matter so much; it actually helped. I actually had access to things I wouldn’t have access to otherwise: panighýria and celebrations. Sometimes they would invite me to play, I got kind of a backstage pass. I had a closer relationship, I had been learning the music for several years before starting the research, they were my friends before starting the research. (Maher, interview 29 March 2019)

Maher’s strategy echoes my Mallorcan activity. Once my musicianship was publicly established, I found that there was little need to impose my participation on the field. The knowledge that I could participate at a level that satisfied the musicians in the community seemed to be enough. Like Maher, I was recognised by the musicians as someone who had acquired the necessary participatory skills and had the crucial experiential knowledge as a musician. The invitations to perform were on an ad hoc basis for local celebrations. These moments were key, as they were the most coded and well-guarded domains of the musicians who only let those with knowledge and skills participate in them. During these crucial performances, I gained insights that were enhanced by the solemnity of the moment or the knowledge of what this specific performance meant for the community and therefore the trust that was passed onto me to lead the community musically. This level of participation was facilitated, I believe, by our empathetic understanding of musician’s politics directly linked to our experience as musicians combined with our interest for the local cultural landscape.

For the remainder of my fieldwork, I chose to focus on my research activities and nearly all but abandoned my practice. I had realised that my musical ability often meant that I was quicker than others to learn and play melodies, especially in amateur circles, and my musical participation was neither sought nor particularly valued. I took a few group lessons to socialise with other pipers and then resolved myself to playing only on occasions when I was invited to do so.

Furthermore, participation would have led me to privilege engagement and public appearances with one or more groups. This would, I believe, have compromised my social autonomy. Indeed, Flood found that her position as a fiddler constrained her social autonomy and bound her to social and relationship obligations (Citation2017: 500). Social autonomy became one of my defining characteristics as an ethnomusicologist within the community, admired by pipers who were unable to navigate through the island as freely as I was due to a combination of ideological differences and internal politics. In Mallorca, my social autonomy came to be expected, and I was recognised, by the end of my fieldwork as being ‘the first musician/ethnomusicologist capable of crossing by herself the path of all the xeremiers of Mallorca' (see ), something that was unheard of. I believe that this position was only possible thanks to my status as an ‘outsider musician’.

Figure 3. Clay figurine by Ricardo Gago of a xeremier (left) and flabioler (right) given as a present at the end of the author's fieldwork. Translation of inscription: ‘To Cassandre Balosso-Bardin. For being the first musician/ethnomusicologist capable of crossing alone the path of all the xeremiers of Mallorca, winter 2013.’

Although my ability to pick up a Mallorcan bagpipe and play when asked to was essential, proving that I had learned local repertoire and ornamental aesthetics, my activity as a researcher, or ‘[their] ethnomusicologist’ as one piper put it, was much more interesting than being another piper amidst a saturated scene. I had found a field that had hardly ever garnered any academic interest beyond Catalan-speaking regions, and my position as a researcher was a more useful role, strengthened by my knowledge of and engagement with other musical cultures and foreign academia.

For the duration of my fieldwork, I kept my on-going musical practice separate, continuing at home and on tour in order to satisfy my needs as a practicing musician. Not only was there no local scene for my musical activities, this external activity had the benefit of maintaining my profile through social media, supporting my position as a musician, whilst safely exerting my profession on foreign lands, removing any threat to the local community. My activity, though, did not go unnoticed and my position as an international musician allowed me to enter into reciprocal relationships beyond simple participation in local music-making.

Reciprocity in the field and after, or becoming ‘useful’

Shelemay writes that ‘anthropologically trained ethnomusicologists have … actively participated in musical performance in the field, … most often to ensure reciprocity and/or to test their understanding of musical data they have gathered’ (Citation2008: 143). I hope to have established that musical participation does not automatically translate into reciprocity. Indeed, reciprocity may have more to do with observing protocol, including abstaining from playing unless expressly invited to do so, just as it might mean playing even if one had not expected to. The ability to play if so required is, in a way, more important than the performative act itself. To reiterate Kippen’s observation, musical reciprocity leading to an equitable musical dialogue is difficult to achieve ‘at least not until one has spent many, many years becoming, metaphorically, an adult within the tradition’ (Kippen Citation2008: 133). Beyond performative skills, this includes the codes surrounding musical practice and labour. This is not impossible. Tsioulakis managed to engage with his co-workers on a musical but also social and intellectual level thanks to the transparency with which he used his multiple identities: jazz musician, academic and ethnic insider (Citation2020a). This level of sustained musical reciprocity is, however, not an easy task to achieve.

That said, I argue that musician-ethnomusicologists seem to naturally engage in reciprocal relationships, fitting neatly into the applied part of our discipline. As individuals who can embrace several identities in the field, ethnomusicologists slowly become part of a system that they sought entry into and become a bridge between worlds. Simply put, they can become a ‘useful’ part of the community, fulfilling a role established by the latter. The ethnomusicologist’s job, then, is to be able to identify this role and to adapt to it while, of course, following our ethical code. The underlying criterion for reciprocity is an ability to observe protocol that is tacitly set out by the community. As a visitor in the community, we are bound to ‘treating others with respect, care, modesty, courtesy, exchange, and reciprocity’ (Titon Citation2008: 38). Baily, for example, describes the appreciation of his new master when he refused to play several times before giving in, demonstrating his fluency in cultural codes surrounding invitations to play (Citation2001). Similarly, Kisluik describes the ‘special kind of courtesy’ that forms a ‘tacit basis’ for musical interaction in a bluegrass session (Citation1988: 146). The ethnomusicologist must, then, be able to listen and hear what the community wants.

Beyond adhering to social contracts within the community, I have identified five areas of reciprocity that ethnomusicologists in general and musician-ethnomusicologists in particular engage with. These reciprocal ‘applied relationships’, where the ethnomusicologist engages directly with the community taking on a role that fulfils a need of function, include advocacy, network, social responsibility, support and visibility.

Advocacy

Tsioulakis offers a striking example for advocacy. During his time working in nightclubs as a contracted musician while carrying out fieldwork, he became the spokesperson for the musicians, arguing for their salaries and benefits with management. As a professional musician and full member of the band, he was able to represent their position, while simultaneously risking his position in the nightclub. His dual role, as an academic and musician, meant that he had less to lose were he to be fired than his colleagues, nor was he jeopardising his reputation as someone who was always asking for money. Tsioulakis reflects that his position as a ‘co-worker’ and ‘temporary insider’ allowed him to ‘stand with [his] colleagues and put [him]self on the line because … [he] could speak out without worrying about the longevity of [his] career and reputation’ (Tsioulakis Citation2020a).

Network

As musicians from different parts of the world, we bring with us new networks that we actively engage with. As academics, we have links to our institutions, which might help invite a musician as a guest artist (Rice Citation2008), but as musicians, we have extended relationships with agents, venues and other musicians. This, for example, led Maher to organise a mini-London tour for one of the clarinettists she worked with. Although this went well, prompting demand for more UK opportunities by the musician, Maher noted that ‘he was surprised that there was not more money going around and more gigs as well, he thought you could just turn up and play’ (interview 2019).

Social responsibility

Social responsibility is exemplified by Flood (Citation2017), who took on a role that fulfilled a need within the community. Pushed into a meaningful participation by the musicians, she took a role that was key to her field. Social responsibility can, of course, be carried out in non-musical ways, such as archiving data, sharing recordings and images and in general supporting the community through an academic skillset. Musical social responsibility, however, is not to be underestimated, as shown by Shelemay, who through her musical practice and knowledge, became part of a chain of transmission within a diasporic community (Citation2008).

Support

During my fieldwork and after, I was able to support Mallorcan musicians more than once. Using my experience as a musician, I advised younger musicians who were looking for breaks on the international folk music scene. Conversations led to a band applying for a spot at a Galicia festival, which led them to go onto more prestigious concerts in Spain and in the UK. Other musicians turned to me several times, both to attend international music workshops and to support communication with French festival organisers, providing them precise formulas needed to navigate through French administration. Similarly, links with museums and other musicians around the world have led me to support the business of several instrument makers as I send them prospective clients.

Visibility

Visibility can come in different forms, such as publicity or dissemination. Titon, for example, supported a blues musician by publishing an interview with him and ‘became someone who might be able to promote them, to help them in their careers, instead of just a young man hanging around older ones and trying to learn music from them’ (Citation2008: 26). Just as Titon became a useful addition to the musicians’ network, enhancing their visibility beyond their usual scope, I was, after a year in the field, designated by the musicians as a natural representative of Mallorcan traditional music. In a few instances, I was asked by local municipalities to give presentations about the xeremies and asked my musician friends whether they wanted to speak instead. They were happy to play, but drew a line at speaking: I was now their ethnomusicologist and had my role to fulfil. So, when asked to give a talk for the Balearic delegation in Brussels in 2018, I gave the talk, but also named musicians from Mallorca, Ibiza and Menorca who were invited to participate and perform alongside my presentation. With visibility comes responsibility and, in the Mallorcan context, I have been wary of speaking about my research beyond cultural and academic circles. Local musicians have said in jest to not say too many nice things about them, which highlights a more serious undertone as tourism increasingly encroaches onto their cultural space, forcing me to respect their wishes and think carefully how and where I talk about their musical traditions.

Reciprocity is embedded within social contracts, supported by tacit codes of protocol and understanding. The musician-ethnomusicologist position not only facilitates moments of musical reciprocity, it also enhances the capacity for meaningful exchanges beyond the realm of musicking. The multiplicity of roles accessible through the researcher enables a range of interactions that contribute to feelings of mutual benefit that can extend beyond the field, whether these are musical, educational, promotional or material.

Conclusion

Musical ability matters and participation offers valuable insights. However, musical participation is not necessarily always the most desirable methodology to engage meaningfully with a community. The ability to engage musically at the drop of a hat seems to be valued by local musicians, but constant participation is not always required. The various experiences explored in this paper highlight the fact that mature musical competence increases the agency of the local community when it comes to deciding how the newcomer can or will participate. How one is asked to participate musically reveals how music might be socially constructed. In Flood’s case, she was required to become a fully participative fiddler, filling a strong socially prescribed role. In my case, participation was only required in carefully coded performances and these were mainly used to prove that I knew the music and understood the honour that was being bestowed on me by inviting me to play. I was more valuable as a socially unrestricted researcher than yet another piper, but this status was only attainable thanks to my musical understanding. In other words, I first had to be recognised as a musician in order to be able to become ‘their’ ethnomusicologist.

Musical participation is, indeed, a tool for fieldwork. Previously acquired musical competence and experience can also been seen as an extra layer of skills, much like having fluency in the local language before entering the field. Beyond participation, musician-ethnomusicologists enable communities to decide how they will become useful. This may be as an agent a critic, a journalist, an administrator, a musician, or even as an academic. The musical, experiential and social baggage of the musician-ethnomusicologist allows the researcher to go beyond the act of musicking and to engage with the community on a deeper and more satisfying level. Thus, a sense of mutual benefit may be reached more easily as the researcher brings a wider palette of identities that can be engaged with. This shifts the focus back to the field, with the individuals effectively deciding the nature of the engagement with the ethnomusicologist, whether this fits within the researcher’s initial imagined relationships or not. It activates the agency of the community in what one might describe as an ‘applied relationship’. As such, the musician-ethnomusicologist fluctuates on the emic-etic continuum as their identities adapt to the needs of the local community.

This article, whilst ostensibly focusing on the musician-ethnomusicologist navigating the field, also highlights the fact that researchers call upon a range of external skills that are central to their practice, complementing and enhancing each other. Titon reminds us that musical activity and scholarship are highly compatible (Citation2008). I argue that musicians who also exercise a research practice are enmeshed in two worlds that are intricately entwined and difficult to untangle. Despite this, the REF exercise focuses on the material research output; the process or methodology involved, where the wider activity of the musician-ethnomusicologist comes to the fore, remains an unspoken activity. Unlike practice-based researchers, their creative practice does not lead to direct research results and is, therefore, overlooked. Asking a musician-ethnomusicologist whether their activity is research or practice-based, is like asking whether they see from their left or right eye. Both offer slightly different perspectives, but together present a vivid, enhanced, three-dimensional image. As such, to the professor who once asked me where I placed my research, I would answer both in my creative practice and my ethnomusicological activity. As both depend on each other and enable a deeper connection to the research that I then choose to translate through language, is it necessary to separate them at all?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cassandre Balosso-Bardin

Dr Cassandre Balosso-Bardin is a Senior Lecturer in Music at University of Lincoln. Her research interests, informed through fieldwork based research and performance, include Mediterranean music, musical instruments, cultural sustainability, and intercultural music-making. She worked as a postdoctoral researcher for the interdisciplinary Geste-Acoustique-Musique project at Sorbonne-Université in 2016 and is the founding director of the International Bagpipe Organisation since 2012. Classically trained, Dr Balosso-Bardin is an internationally touring performer and a member of Världens Band (Sweden) and Amaraterra (Italy/UK). She has performed on the bagpipes and recorders at many festivals and venues including the Proms, Womad, Cambridge Folk Festival, the Sage, Musicport, Aan Korb BBC festival, Bloomsbury festival, Urkult, Stockholm Culture Festival and Oslo World Music Festival.

Notes

1 Many scholars have discussed in depth bi- or poly-musicality (Hood Citation1960; Nettl Citation1983; Tokita Citation2014; Wong, Roy and Margulis Citation2009; Cottrell Citation2007; Slobin Citation1993) as well as the experience of performing in the field (Rice Citation2008; Cooley and Barz Citation2008; Titon Citation1995 and Citation2008; Baily Citation2001; Wong Citation2001; Shelemay Citation2008; Witzleben Citation2010; Stock and Chiener Citation2008).

2 Generative or productive competence is described by Tokita as ‘the ability to create new original music, and/or the mastery and authority to be an agent of transmission’ (Citation2014). This level of competence sees musicians adapting or altering a tradition.

3 The fieldwork referenced in this paper was part of my PhD qualification and reviewed for its ethical implications. The work was approved via the School of Oriental and African Studies, Postgraduate Research Section in June 2011.

4 See Witzleben for a critique on the scholarly study of musical experiences (Citation2010: 144).

References

- Baily, John. 2001. ‘Learning to Perform as a Research Technique in Ethnomusicology’. British Journal of Ethnomusicology 10 (2): 85–98.

- Balosso-Bardin, Cassandre. 2016. ‘A Musician in the Field: The Productivity of Performance as an Intercultural Research tool’. In The Routledge International Handbook for International Arts Research, edited by Pamela Burnard, Elizabeth Mackinlay and Kimberly Anne Powell, 152–162. London: Routledge.

- Balosso-Bardin, Cassandre. 2018. ‘#NoBorders. Världens Band: Creating and Performing Music across Borders’ [Sharing Space? Sharing Culture? Applied Experiments in Music-Making across Borders]. The World of Music (New Series) 7 (2): 81–106.

- Balosso-Bardin, Cassandre, Augustin Ernoult, Patricio de la Cuadra, Benoît Fabre and Ilya Franciosi. 2018. ‘The Secret of the Bagpipes: Controlling the Bag. Techniques, Skill and Musicality’. Galpin Society Journal 7: 189–272.

- Cooley, Timothy J. and Gregory F. Barz, eds. 2008. Shadows in the Field : New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cottrell, Stephen. 2007. ‘‘Local Bimusicality among London’s Freelance Musicians’’. Ethnomusicology 51 (1): 85–105.

- Feld, Stephen. 1982. Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Flood, Liza Sapir. 2017. ‘Instrument in Tow: Bringing Musical Skills to the Field’. Ethnomusicology 61 (3): 486–505.

- Genovart Espinosa, Antoni. 2012. ‘Concert de cornamuses per encetar la Fira de Sa Pobla’. Es Grall 7: 20–21.

- Herndon, Marcia. 1993. ‘Insiders, Outsiders: Knowing Our Limits, Limiting Our Knowing’. The World of Music 35 (1): 63–80.

- Hood, Mantle. 1960. ‘The Challenge of "Bi-Musicality"’. Ethnomusicology 4 (2): 55–59.

- Kim, Hyelim. 2014. ‘Winds of Change: Tradition and Creativity in Korean Taegum Flute Performance’. PhD thesis, SOAS, University of London.

- Kippen, James. 2008. ‘Working with the Masters’. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 125-40. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kisliuk, Michelle. 1988. ‘“A Special Kind of Courtesy”: Action at a Bluegrass Festival Jam Session’. TDR 32 (3): 141–55.

- Maher, Nicola. 2019. ‘The Crying Clarinet: Emotion and Music in Parakalamos’. Ph.D. diss., Cardiff University, Wales.

- Maher, Nicola. 2019. Skype interview, 29 March 2019.

- Nettl, Bruno. 1983. The Study of Ethnomusicology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Rice, Timothy. 2008. ‘Toward a Mediation of Field Methods and Field Experience in ethnomusicology’. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 42–61. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Salvator, Ludwig (Archduke). 1897. Die Balearen, In Wort und Bild geshildert. Leipzig: Brockhaus.

- Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. 2008. ‘In Ethnomusicologist, Ethnographic Method, and the Transmission of Tradition’. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 141–156. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Slobin, Mark. 1993. Subcultural Sounds: Micromusics of the West. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

- Stock, Jonathan and Chou Chiener. 2008. ‘Fieldwork at Home: European and Asian perspectives’. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 108–124. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Titon, Jeff Todd. 1995. ‘Bi-Musicality as Metaphor’. The Journal of American Folklore 108 (429): 287–297.

- Titon, Jeff Todd. 2008. ‘Knowing Fieldwork’. In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 2nd ed., 25–41. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tokita, Alison. 2014. ‘Bi-musicality in Modern Japanese culture’. International Journal of Bilingualism 18 (2): 159–174.

- Tsioulakis, Ioannis. 2020a. ‘Standing with: the role of the ethnomusicologist in the musicians’ struggle for better working conditions’. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of International Council for Traditional Music-Ireland. University College Cork. 21–22 February.

- Tsioulakis, Ioannis. 2020b. Musicians in Crisis: Working and Playing in the Greek Popular Music Industry. New York: Routledge.

- Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Waldren, Jacqueline. 1996. Insiders and Outsiders, Paradise and Reality in Mallorca. Providence: Berghahn Books.

- Witzleben, Lawrence. 2010. ‘Performing in the Shadows: Learning and Making Music as Ethnomusicological Practice and Theory’. Yearbook for Traditional Music 42: 135–166.

- Wong, Deborah. 2001. Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Performance. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Wong, Patrick C. M., Anil K. Roy and Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis. 2009. ‘Bimusicalism: The Implicit Dual Enculturation of Cognitive and Affective Systems’. Music Perception 27 (2): 81–88.