ABSTRACT

Does crime exposure impair levels of political knowledge? The literature on crime has focused on its causes as well as its scope, while ignoring how it might influence the practice of political citizenship. Informed citizens are more able to practice their political citizenship. Exploring the impact of experiencing an insecure environment in itself, this article contributes to a deeper understanding of how the citizen responds to crime (burglary and physical attacks). Working memory has limitations and previous research has shown how resource scarcity limits cognitive capacities. This article suggests that crime might produce a situation of security scarcity, i.e. insecurity, which limits cognitive capacity in a similar fashion. This hypothesis is tested in the context of Sub-Saharan Africa, using survey data from the Afrobarometer (Round 4). The findings demonstrate how experiencing a security scarcity decreases political knowledge among male citizens, but not among female citizens.

Introduction

The ability of citizens to make considered judgments is essential for holding elected representatives accountable, as well as for forward-looking electoral decisions. Dahl and others have argued for the importance of informed citizens for the workings of democracy, as indicated by the emphasis on enlightened understanding.Footnote1 Recently it has also been demonstrated that uninformed voters make different evaluations of candidates and parties, and that they make different choices during elections as they have a harder time translating their preferences at the ballot.Footnote2 Hence, political knowledge is essential to whether or not the outcome of an election reflects the will of the people.

A branch of research focusing on cognitive capacity has recently shown us how cognitive resources (such as working memory) are limited, and that such resources are easily taxed if the individual is under duress, due to scarcity of means. Developing this theory, this article suggests that this scarcity mechanism may also come into effect in a violent landscape where the individual experiences a scarcity of security. Thus, a citizen’s cognitive capacity may be detrimentally affected by the exposure to crime, hence reducing political knowledge. Hence there are reasons to believe that high crime environments and violent landscapes may impact levels of political knowledge. Crucially, we do not know if violence and crime spurs vicious circles decreasing political knowledge, producing less accountability, less forward-looking choices, and ultimately deteriorating democracy.

Recent work suggests that there are systematic differences in the distribution of political knowledge,Footnote3 and such unequal distribution of political knowledge is worrisome. If crime is found to impact levels of political knowledge, this may be contributing to the uneven distribution of political knowledge in society. While there are limitations in the data, homicide rates in Africa are reported as more than double the global average and 36% of the total number of homicides in the world took place in Africa in 2010.Footnote4 The highest global rate of major assault is also found in West, Central and Southern Africa even if data is scarce.Footnote5 There is very little research that focuses specifically on Sub-Saharan Africa and the consequences of crime.Footnote6 The little research there is focuses on describing the extent of crime levels, and its causes.Footnote7 Overall, the research on crime and criminology in general tend to focus on the causes of crime, rather than the consequences of crime. The little research that exist that focuses on the social and political effects of crime has tended to focus on how it impacts social ties and trust levels.Footnote8 Thus, it is no surprise that current research pertaining to crime has not paid attention to how it impacts the citizen and her ability to practice her citizenship. This article attempts to rectify this, by examining whether crime can impact levels of political knowledge, through the creation of security scarcity. In addition, as both work on cognition and crime often note important gender differences, this potential gender gap is also tested in this article.

The research question is therefore: Does crime impact levels of political knowledge? To answer this, data from the Afrobarometer (2008/2009) is used. After deriving the research hypotheses, the data used and measurements are described and discussed. The following analysis section contributes to an understanding of how the citizen responds to crime and insecurity through focusing on the experience of an insecure environment in itself. This article finds that security scarcity is negatively associated with political knowledge for men across model specifications, but not among women. Further research is therefore needed into ascertaining the mechanism(s) behind this effect. Yet, violence and crime experiences seem to especially impede male citizens in attaining political knowledge: making informed choices at the ballot box are more difficult in the midst of insecurity and crime.

Crime and political knowledge

The role of informed citizens for the performance and implementation of democracy has stimulated a lot of research on political knowledge. Research on political knowledge has tried to explain its occurrence (both in relation to individual and structural variables);Footnote9 its distribution with respect to gender;Footnote10 its impact on voter turnout and political participation;Footnote11 and tried to determine the consequences of a lack of well-informed citizens.Footnote12

Cognitive functions and the ability to process information are central to amassing and processing political knowledge, and by extension the practice of your citizenship. Cognitive abilities and functions is a rich and large field of research. Using research from behavioural economics, I argue that a violent environment may have a detrimental impact on our cognitive functions. If our environment exposes us to events that are taxing on our cognitive functions, this may affect our ability to focus our attention and learn about politics.

Cognitive capacity is a limited resource, and when the individual is forced to focus on specific issues, research has shown that this is likely to undermine the individual’s ability to focus on other things. In particular, this has been studied in relation to experiencing scarcity of means (such as food or money). Mullainathan has shown using both lab experiments and field experiments that experiencing a resource scarcity preoccupies the individual to such an extent that cognitive functions are weakened. Importantly, this research demonstrates that poverty alone reduces cognitive capacity.Footnote13 In particular, cognitive capacities such as attention and self-control are noted to be limited resources, and if an individual has to focus a lot of these resources on one problem, they are likely to be less available for other areas of that person’s life: “scarcity further reduces those already limited resources, hampering the ability of poor people to follow through on tasks or to make effective decisions.”Footnote14

In particular, it seems as if it is our limited working memory which gives rise to these limitations in our cognitive capacities, even if our long term memory has an impressive capacity. Taber notes that our working memory is limited in three ways: we can only focus on a limited amount at the same time, new items can only enter as we disband of old items, and the rate of fixation to long-term memory is very slow.Footnote15 The conditions of our working memory are such that if our attention is caught by something in particular our ability to also give attention to other issues is severely reduced. Thus, for example a person who has to focus on their resource scarcity will have less cognitive capacity available for other tasks in life.Footnote16

This research leads us to expect that political knowledge should be similarly affected by experiencing resource scarcity. However, this could be expanded beyond the experience of resource scarcity. Shah, Shafir and Mullainathan suggest that there is something more general going on here, particularly as “people shift their focus towards areas of perceived scarcity”,Footnote17 irrespective of what kind of scarcity is at stake. Importantly, Shah et al suggest that “we are missing a study of scarcity itself”.Footnote18 Following this line of thought, I suggest that experiencing a security scarcity should give rise to the same phenomenon. Living in uncertain conditions, where you are constantly exposed to crime or other events that endanger your own and your family’s safety should similarly detract attention from other things in your life. Threats to your own and your family’s welfare are likely to catch your attention and receive priority. Thus exposure to crime should result in a felt security scarcity. Preoccupied by personal safety, politics and being informed about politics become a less central concern for such an individual. Based on this, a hypothesis is put forward which focus on how security scarcity impacts political knowledge:

Hypothesis 1: Crime exposure decreases cognitive capacity, resulting in less political knowledge.

Recent work on working memory within neuroscience has noted that there are important gender differences. For instance, Speck et al note that their “data demonstrate strong gender differences in the pattern of brain activation associated with WM [working memory] tasks”.Footnote19 Similarly, Bell et al note that there is “considerable evidence of differences between males and females in brain activation in response to cognitive challenges”.Footnote20 Overall, gender differences are argued to be central in much of neuroscience.Footnote21 It is not apparent how these gendered differences in terms of working memory will play out in relation to the scarcity hypothesis, but there is enough work to suggest that it is likely to expect differences between the sexes.

Similarly, we also know that there are important differences between the sexes related to crime.Footnote22 Especially, there is a noted gender gap related to the fear of crime (as women tend to be more worried about crime despite less exposure), and research suggest that men and women respond differently to environmental and personalised factors when determining risk.Footnote23 This adds further weight to applying a gender differentiated analysis in terms of the scarcity hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The impact of crime exposure on cognitive capacity and political knowledge is different between men and women.

Data and method

The Afrobarometer survey, Round 4, is used for the analysis. This round covers 20 countries.Footnote24 This is the most recent round which includes questions that can be used to measure political knowledge. The surveys were conducted in 2008, except in Zambia and Zimbabwe where they were conducted in 2009. Together these surveys encompass 27,713 respondents. The Afrobarometer survey is the result of a research network that collects public attitude surveys across Africa, and has done so on a regular basis since 1999. The data is collected in order to generate a representative sample of all citizens of voting age in the countries covered.

Dependent variable: political knowledge

The dependent variable political knowledge is measured using knowledge questions that were asked in Round 4 of the Afrobarometer. The measure of political knowledge is composed of the respondent’s ability to identify (name) their Member of Parliament and the Minister of Finance correctly. The variable focuses on what is factually correct knowledge (the veracious dimension of political knowledge), and in particular the type of knowledge that is termed “surveillance facts” rather than “textbook facts” or static facts.Footnote25 Factually correct knowledge belongs to one of four types, delineated by their temporal dimension (static or surveillance) and their topical dimension (general or policy-specific).Footnote26 The surveillance facts used here relate to the individual’s capacity to retain information regarding new events, and not information concerning the functioning of government as detailed in the constitution for instance (which tends to be temporally invariant). This is important, as it is political knowledge that can vary over time which can be impacted by crime exposure. Thus the measure is focused on general surveillance facts, and not policy relevant knowledge. Policy relevant surveillance knowledge should be even harder to attain than surveillance knowledge about institutions and people.Footnote27

The variable is coded as the per cent of questions the respondent answered correctly (per cent correct). Thus, the dependent variable has three possible values, neither correctly identified (0), one correctly identified (50) and two correctly identified individuals (100). The variable does not differentiate between which questions were answered correctly, thus the distance between knowing nothing and knowing one answer and between knowing one answer and two answers are deemed the same.Footnote28 A linear regression model is used for the analysis, as this is simpler to use and interpret compared to ordered logit (many have made calls for more parsimonious and simple models).Footnote29 As can be seen from below, as many as 45.17 per cent could not identify either individual, and 41.47 per cent could identify one, and only 13.36 per cent of the sample could correctly identify both.

Table 1. Distribution of political knowledge.

In order to assess this variable’s validity, it was correlated with a number of items. As one would expect, it is positively correlated with education (0.295***) and voting (0.081***). In addition, per cent correct was also negatively correlated with an index variable (−0.115***), a variable which measures whether or not the respondent has heard enough about a number of political actors and institutions to answer a question about trust. The important issue here is not the response to trust, but rather whether the respondent had heard enough about the specific actor to rate their trust for each one. The variable was generated through adding up the times the response category “Haven’t heard enough to say” was used by the respondent when asked to rate their trust for a range of political actors/institutions: president; national assembly, national election commission, elected local council, ruling party, opposition, police and courts of law. This variable ranges from 0 to 8, where 8 indicates that the respondent did not feel they had heard enough about all 8 actors/institutions to rate their trust for them, i.e. very low political knowledge. Most people scored 0 (and thus felt as if they knew enough about the actor in question to answer the consecutive question) (80.54 per cent), but some did not. The negative correlation between per cent correct and have not heard about is as expected, as the higher the respondent scored on the not heard about index, the fewer political actors the respondent felt they knew enough about to comment further on, which in turn corresponds to scoring low on the per cent correct variable. Per cent correct is a better measure of political knowledge, as the subjective rating of the respondent concerning whether they know enough about certain actors to comment on them further is an indication of the degree to which the respondent feels familiar and knowledgeable about these institutions and actors (thus to some degree reflecting internal efficacy). This test could have been done using any other variable, with a response category noting that the respondent does not feel they have heard enough about the actor to rate them on said variable.

The main limitation of the measure for political knowledge used in this article is that the number of items it relies on is limited. Preferably a larger battery of general surveillance facts should have made up the variable, but the survey format does not allow for this. In this sense, the fact that the variable correlates as expected with other measures is reassuring. Of course, the needs of the citizen in order to make an informed choice are also much larger than what is captured by general surveillance facts. What kind of knowledge a citizen and voter should primarily have is of course a much larger both normative and empirical question.Footnote30 Yet, name recognition and attention to new events in politics are important facets of the multidimensional concept of political knowledge. The measures used here focus on the formal aspects of politics, as they pertain to elected representatives rather than local big men which in many contexts might be even more important local political knowledge.Footnote31 Nevertheless, even in these contexts formal power is not irrelevant either, and this measure also has a local focus as one of the questions focus on the Member of Parliament representing their district. Ideally, however, a larger array of such questions would have been more appropriate than solely relying on two knowledge questions.

Measuring crime

The main independent variable is crime. Crime can be defined in many different ways, and there are discussions between definitions that focus on legally defined crime and definitions of crime which are not dependent on the illegality of the act.Footnote32 In this context, working with data from multiple different legal settings, crime that is legally defined could pose problems. However, given the purposes of this article, legally defined crime is enough of a starting point. In addition, the particular crime that interests this article, is crime that imposes on the direct physical security of others, and thus inflicting harm. Hence, crimes which may break the tax code in a country, is not relevant here. The types of crime exposure measured in the survey are rather common types of crimes, and thus while the legal definition of assault and burglary may vary between countries, as well as the punishment of such crimes, there is no doubt that both types of acts can be defined as crimes. These are also crimes which include interpersonal violence.Footnote33 Thus, crime exposure here, such as experiencing burglary or violence, would result in a lack of physical security, i.e. a security scarcity.

Two items are used to capture crime: the first asks how often the respondents have had something stolen from their house, and the second asks how often they have been physically attacked. The variable taps current lack of security, and not the anticipation of future crime. The Afrobarometer asked the following questions: “Over the past year, how often, if ever, have you or anyone in your family: been physically attacked?” and “had something stolen from your house?” The variables are measured on a 5-category scale (never, just once or twice, several times, many times and always, 0–4). The two variables correlate (0.371***). These two variables are used as an additive index (0–8) to measure exposure to crime, especially as the variation in these variables is fairly limited. A small majority (51.43%) in the survey have never experienced a physical attack or burglary.Footnote34 However, all models were tested with the two separate indicators as well, and the results are largely similar (fewer results are reported as significant). See below for the distribution of the different crime measures. Men and women are also similarly exposed to both types of crime, so there is no large gender difference with respect to these types of crimes. Of course, had the survey included an item on sexual assault the trend may have been different.

Table 2. Distribution of crime measures.

Control variables

A number of control variables are also used in the analysis, particularly as many of these variables are likely to shape political knowledge, but also be associated with vulnerability to crime and violence. The exclusion of these control variables is likely to bias the coefficient estimates.

The scarcity literature would clearly suggest that experiencing resource scarcity (i.e. poverty) should decrease people’s attention to political events and thus result in less political knowledge (the literature on socioeconomic status would result in similar predictions). Poverty is measured through how often the respondent has gone without food and a cash income, as lack of such material benefits is likely to occupy the respondent to a high degree, hence tasking on cognitive abilities. The survey questions related to poverty were measured as follows: “Over the past year, how often, if ever, have you or anyone in your family gone without: a cash income/enough food to eat.” The variables were measured on a five-category scale (never, just once or twice, several times, many times and always, 0–4).

Individuals who participated in elections are also likely to be more knowledgeable about politics, thus the models use a dummy variable to measure whether or not the respondents voted. Locality is also likely to matter both for knowledge of politics as well as exposure to crime, thus the models also use a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent lives in an urban or rural setting. In addition, the following variables are used as controls, as they are recognised as important predictors of political knowledge: the respondent’s age (measured in years, continuous); gender (dummy, male = 1); level of education (10 categories, from no formal schooling to post-graduate);; political interest (“How interested would you say you are in public affairs?”, four categories, from “not at all interested” to “very interested,” 0–3); and access to news. Measuring the respondent’s access to news, one item indicating access to news through radio is used. Access to news through radio is the most accessible channel and not dependent on the respondent’s literacy.Footnote35 The variable has five answer categories (“How often do you get news from the radio?”, from never, less than once a month, a few times a month, a few times a week, and every day, 0–4).

In addition to controls at the individual level, a number of controls are also introduced at the country level. The conditions for both security scarcity and political knowledge may differ between wealthier countries and poorer, as well as depending on the level of democracy in the country. Hence, GDP per capita (2008) as well as a country level variable measuring level of democracy (Freedom House) are used as controls. The general level of violence in the country may also matter for the hypothesised relationship; hence homicide rate is also used as a control. The homicide rate (number of homicides per 100,000) is used as a measure of lack of security at the country level. This variable has data for 14 of the countries included in the Afrobarometer, from the year 2008. Other measures of crime, such as rate of assault and rate of theft are also possible measures, but this data limits the data to even fewer countries. The data is from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). When employing homicide rate the observations are still considerably limited to those countries with available data, hence the analysis is conducted with and without this particular control.

For more details on the variables used in the analysis, see the Appendix, with descriptive statistics on all variables, see .

Analysis

The scarcity hypothesis suggested that when people’s attention are taken over by pressing concerns, such as their own security or physical well-being (due to their crime exposure), their ability to give attention to other things such as politics is reduced, and as a result their levels of political knowledge should also be low. The analysis begins with an examination of the relationship between crime and the dependent variable political knowledge with individual level controls across different groups, followed by the introduction of country level controls (multi-level analysis). The dependent variable is per cent correct. See , these results are robust to alternative specifications.Footnote36

Table 3. Political knowledge, per cent correct (0–100).

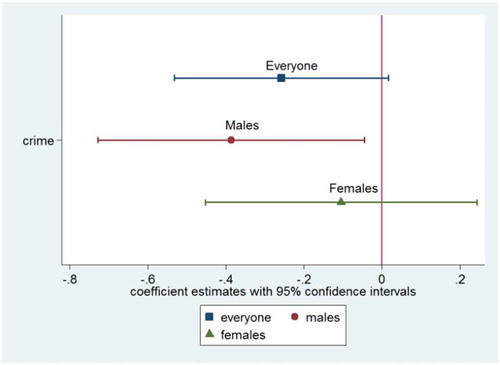

Model 1, 2 and 3 use the additive index of crime together with a number of individual level controls. The coefficient for crime is reported as negative in Model 1 (in line with hypothesis 1); however it is not significant at 95%. When splitting the sample between males and female (model 2 and 3), it becomes clear that experiencing crime has a statistically significant negative impact on political knowledge for men, but not for women. Thus far, the results are consistent with hypothesis 2. Using Model 2, the substantive impact of crime is sizeable if not overwhelming; moving from no exposure to burglary or physical attacks to always feeling exposed to burglary and physical attacks during the previous year, is associated with 3.04 percentage point decrease in the per cent of questions the respondent answered correctly among men. The results remain the same without the controls, and when adding other control variables such as other sources of news, voting for the incumbent, and whether the respondent felt that their ethnic group was treated unfairly, and when dropping the variable political interest. Using the constituent crime measures of having something stolen or being physically attacked the pattern is largely similar, where exposure to some crime is associated with lower levels of knowledge among men, whereas for women the relationship is null.

In Model 4, 5 and 6 the country level controls of GDP per capita and democracy are added, and again we see that the relationship between crime exposure, security scarcity, and political knowledge is reported as negative in the full sample (in line with hypothesis 1), but not statistically significant. However, when the sample is split between males and females, the relationship is statistically significant among men but not among women, in support of hypothesis 2. See . Similarly, when we add the homicide rate in Models 7, 8 and 9, the same pattern is repeated, despite losing several observations as many of the countries have missing data on the homicide rate.

The control variables operate as expected, with one exception: cash income scarcity. Poverty (resource scarcity) in terms of lack of food and lack of income were included in the model. Experiencing food scarcity is consistently associated with lower levels of political knowledge. However, experiencing a cash income scarcity is not a statistically significant predictor of political knowledge across the model specifications. The reason for this could be related to patronage tendencies in these contexts and in cases where politics can be a source of financial income; thus, experiencing a scarcity of cash income may increase attention to politics and hence levels of political knowledge. Or perhaps it is only a lack of food that truly represents a resource scarcity, whereas the lack of a cash income is less severe. Overall then, food scarcity, but not income scarcity, has the expected negative relationship with political knowledge using the Afrobarometer data. Concerning the other controls, age is positively associated with levels of political knowledge, so is education, political interest and being male. Voters are also more likely to have higher levels of political knowledge. Access to news has a positive impact on levels of political knowledge. Whether or not the respondent lived in an urban setting or a rural is not reported as significant.

In sum, the effect of experiencing crime is fairly consistent across models and does indeed decrease political knowledge among men but not among women. Future work should therefore explore why we see this diverging trend among men and women. An important next step in scrutinizing the results found here would be to examine the mechanisms involved. Suffering from security scarcity should impact your cognitive abilities in general if the scarcity hypothesis is true, and thus we should see evidence of impact on other cognition measures. And does this show the same gendered pattern? Thus, whether it is in fact this limitation to working memory that connects crime and political knowledge requires more work. Similarly, the argument here is that crime creates an experience of security scarcity, and this could also be further examined. Do individuals who experience crime, also feel preoccupied by security concerns? And do the experience of crime and preoccupation with security concerns happen to the same extent for women and for men?

Conclusion

Sub-Saharan Africa is plagued with high levels of crime. The homicide rate in Africa is more than double the global average and 36% of the homicides in the world took place in Africa in 2010.Footnote37 While much research is conducted on the extent and scope of crime and its causes, we know much less about how the individual citizen is affected when trying to exercise their democratic citizenship in insecure landscapes. In an attempt to scrutinise how crime impacts the citizen, Afrobarometer survey data were used to test how political knowledge is influenced by such experiences. In this article the effect on political knowledge stemming from experiencing crime and living in violent environments have been tested. The scarcity thesis suggests that individuals who are confronted with pressing concerns (such as when their life is at risk) are less able to give attention to other things in life. An extension of this hypothesis would then suggest that exposure to crime (giving rise to security scarcity) would result in lower levels of political knowledge. This article shows that living with crime (and associated insecurity) is associated with lower political knowledge among men but not among women. This finding was robust across model specifications.

The gendered difference found in this article should be studied further. Why do men respond differently to crime compared to women? Is it solely a question of differences in how working memory functions, or is something else driving this difference? The data available for this analysis does not allow us to take this question further, but future research should. These are questions that not only require survey data that takes on these questions within studies in criminology, political science and the like, but it is also an ongoing challenge for neuroscience in terms of how cognitive functions are gendered.

There are several limitations to the analysis performed here. In particular, the variable measurements are limited, and this in particular entailed a measure of political knowledge solely based on two items. Yet the concept of political knowledge is multidimensional. Thus, the trends noted here, or the lack thereof may play out differently had other dimensions of political knowledge been examined. However, the validity checks performed on the variable used lend more weight to the conclusions put forward in this article. This article does offer an important expansion and tentative exploration of how insecurity may shape the ability of citizens to make informed choices in politics. Further refining the measures, of both political knowledge and crime exposure should help us explore this relationship further to see if this association continues to hold. Importantly, we should also notice other impacts from security scarcity on other measures of cognitive performance. One important possible extension of the findings in this article, is that it also raises the issue of how insecurity during elections matter for cognition. In contexts where physical insecurity comes about through election violence, how does this impact cognition? This is another burgeoning field of research, where insights from this article could be of use.Footnote38

The lack of security was hypothesized to reduce cognitive capacity much like resource scarcity has been demonstrated to do in the past. As such, this article has demonstrated the relevance of the scarcity thesis in general, expanding on the work related to resource scarcity.Footnote39 If people are overwhelmingly concerned with something in their immediate environment it detracts important cognitive capacity from other issues and concerns that might also matter to the individual’s well-being in the long run. Trying to practice your citizenship in a violent landscape one is thus severely limited.

The findings of this article are especially disheartening for the prospects for democracy. Expanding on the kinds of scarcity which has a limiting influence on our cognitive functions, we see how the citizen is limited in exercising his or her democratic citizenship in environments of insecurity. Crime is not only problematic in terms of the physical harm it gives rise to, but they also deteriorate the quality of the political regime due to how it influences citizens’ ability to engage in an enlightened fashion in the public debate. What is even more disheartening is that the actual experience of crime is unlikely to be evenly distributed in the population, and may well hit those already challenged the hardest. Increased levels of political knowledge deepen the political process and increase the degree to which political choices reflect the will of the people. Violent and crime saturated landscapes undermine this process and in the long run democracy. Fortunately crime levels can be addressed; they are not set in stone.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank a number of different colleagues who at various stages have commented on this paper: Moa Mårtensson, Markus Holdo, Gina Gustavsson, Enzo Nussio, Katrin Uba, Julia Jennstål and Adam Shehata. All remaining flaws are of course my own. This work was partially supported by the Swedish Research Council under Grant 421-2011-1438.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Democracy and Its Critics (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1989); see also Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E Brady, Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 304–33; Jack Knight and James Johnson, “What Sort of Political Equality Does Deliberative Democracy Require?” in Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics, ed. William Rehg and James Bohman (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1997), 299.

2. Anthony Fowler and Michele Margolis, “The Political Consequences of Uninformed Voters,” Electoral Studies 34 (2014); Shane P Singh and Jason Roy, “Political Knowledge, the Decision Calculus, and Proximity Voting,” ibid, no. 0.

3. Anthony Fowler and Michele Margolis, “The Political Consequences of Uninformed Voters,” ibid.: 109; see also M Kent Jennings, “Political Knowledge over Time and across Generations,” Public Opinion Quarterly 60, no. 2 (1996): 229.

4. UNODC, Global Study on Homicide (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2011), 9.

5. Stefan Harrendorf, Markku Heiskanen, and Steven Malby, International Statistics on Crime and Justice (Helsinki: European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2010), 22.

6. For an exception, see Charlotte Lemanski, “A New Apartheid? The Spatial Implications of Fear of Crime in Cape Town, South Africa,” Environment and Urbanization 16, no. 2 (2004).

7. See for example Martin Schönteich, “South Africa’s Position in Africa’s Crime Rankings,” African Security Review 9, no. 4 (2000); Gabriel Demombynes and Berk Özler, “Crime and Local Inequality in South Africa,” Journal of Development Economics 76, no. 2 (2005); Marshall Barron Clinard and Daniel J. Abbott, Crime in Developing Countries: A Comparative Perspective (New York: Wiley, 1973); Kwesi Aning, “Are There Emerging West African Criminal Networks? The Case of Ghana,” Global Crime 8, no. 3 (2007).

8. See for example Catherine E. Ross and Sung Joon Jang, “Neighborhood Disorder, Fear, and Mistrust: The Buffering Role of Social Ties with Neighbors,” American Journal of Community Psychology 28, no. 4 (2000); Wesley Skogan, “Fear of Crime and Neighborhood Change,” Crime and Justice 8 (1986).

9. See for example Kimmo Grönlund and Henry Milner, “The Determinants of Political Knowledge in Comparative Perspective,” Scandinavian Political Studies 29, no. 4 (2006); Michael Henderson, “Issue Publics, Campaigns, and Political Knowledge,” Political Behavior 36, no. 3 (2014); Jennifer Jerit, “Understanding the Knowledge Gap: The Role of Experts and Journalists,” Journal of Politics 71, no. 2 (2009).

10. Jay K Dow, “Gender Differences in Political Knowledge: Distinguishing Characteristics-Based and Returns-Based Differences,” Political Behavior 31, no. 1 (2009); Kathleen Dolan, “Do Women and Men Know Different Things? Measuring Gender Differences in Political Knowledge,” Journal of Politics 73, no. 1 (2011); Mónica Ferrín Pereira, Marta Fraile, and Martiño Rubal, “Young and Gapped? Political Knowledge of Girls and Boys in Europe,” Political Research Quarterly 68, no. 1 (2015).

11. Paul Howe, “Political Knowledge and Electoral Participation in the Netherlands: Comparisons with the Canadian Case,” International Political Science Review 27, no. 2 (2006); Nakwon Jung, Yonghwan Kim, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga, “The Mediating Role of Knowledge and Efficacy in the Effects of Communication on Political Participation,” Mass Communication and Society 14, no. 4 (2011).

12. See for example Larry M Bartels, “Uninformed Votes: Information Effects in Presidential Elections,” American Journal of Political Science 40, no. 1 (1996); John G Bullock, “Elite Influence on Public Opinion in an Informed Electorate,” American Political Science Review 105, no. 3 (2011); Martin Gilens, “Political Ignorance and Collective Policy Preferences,” ibid 95, no. 2 (2001); David P Baron, “Electoral Competition with Informed and Uniformed Voters,” ibid 88, no. 1 (1994); Pippa Norris, Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 142–68.

13. Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir, Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much (New York: Times Books, 2013), text; see also Marianne Bertrand, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Eldar Shafir, “A Behavioral-Economics View of Poverty,” The American Economic Review 94, no. 2 (2004); Anandi Mani et al., “Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function,” Science 341, no. 6149 (2013); Anuj K. Shah, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Eldar Shafir, “Some Consequences of Having Too Little.” Science 338, (2012): 682–685.

14. Sendhil Mullainathan, “The Psychology of Poverty,” Focus 28, no. 1 (2011): 19.

15. “Information Processing and Public Opinion,” in Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, ed. David O Sears, Leonie Huddy, and Robert Jervis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 442–5.

16. There is however a debate in the literature on the limitations of our working memory, where this resource model is one of several. In a recent review of these different models, the resource model is noted to have several advantages, but it may not be a complete solution for the way in which we model working memory and its limitations. See Klaus Oberauer et al., “What Limits Working Memory Capacity?” Psychological Bulletin 142, no. 7 (2016).

17. Shah, Shafir, and Mullainathan, 12.

18. Ibid., 14. For other examples where the scarcity thesis has been expanded further, see Mariëlle A Beenackers et al., “The Role of Financial Strain and Self-Control in Explaining Income Inequalities in Health Behaviors,” European Journal of Public Health 26 (2016).

19. Oliver Speck et al., “Gender Differences in the Functional Organization of the Brain for Working Memory,” Neuroreport 11, no. 11 (2000): 2585.

20. Emily C. Bell et al., “Males and Females Differ in Brain Activation During Cognitive Tasks,” NeuroImage 30, no. 2 (2006): 536.

21. Larry Cahill, “Why Sex Matters for Neuroscience,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, no. 6 (2006). See also Kelly P Cosgrove, Carolyn M Mazure, and Julie K Staley, “Evolving Knowledge of Sex Differences in Brain Structure, Function, and Chemistry,” Biological psychiatry 62, no. 8 (2007). However, there are also some that argue that these gender differences are not huge, and while important should not be given too much attention, and if they are given attention they need to be handled with care, see Lise Eliot, “The Trouble with Sex Differences,” Neuron 72, no. 6 (2011); Janet Shibley Hyde, “Sex and Cognition: Gender and Cognitive Functions,” Current opinion in neurobiology 38 (2016); “The Gender Similarities Hypothesis,” American Psychologist 60, no. 6 (2005).

22. See for example William R. Smith and Marie Torstensson, “Gender Differences in Risk Perception and Neutralizing Fear of Crime: Toward Resolving the Paradoxes,” The British Journal of Criminology 37, no. 4 (1997); Sarah Bennett, David P. Farrington, and L. Rowell Huesmann, “Explaining Gender Differences in Crime and Violence: The Importance of Social Cognitive Skills,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 10, no. 3 (2005).

23. William R. Smith, Marie Torstensson, and Kerstin Johansson Johansson, “Perceived Risk and Fear of Crime: Gender Differences in Contextual Sensitivity,” International Review of Victimology 8, no. 2 (2001); see also Tilman Brück and Cathérine Müller, “Comparing the Determinants of Concern About Terrorism and Crime,” Global Crime 11, no. 1 (2010): 5; Simon C Moore and Jonathan Shepherd, “Gender Specific Emotional Responses to Anticipated Crime,” International Review of Victimology 14, no. 7 (2007).

24. The following countries were included in Round 4: Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe, Afrobarometer Data, Round 4, 2008/9, available at http://www.afrobarometer.org.

25. Jennings, 229; Jason Barabas et al., “The Question(S) of Political Knowledge,” American Political Science Review 108, no. 4 (2014).

26. 841.

27. Ibid., 841f.

28. The two items were positively correlated, but identifying the Minister of Finance correctly was a harder question (23.15 per cent correct) than identifying the Member of Parliament correctly (45.04 per cent correct).

29. See for example Philip A Schrodt, “Seven Deadly Sins of Contemporary Quantitative Political Analysis,” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 2 (2014): 292f; Christopher H Achen, “Toward a New Political Methodology: Microfoundations and Art,” Annual Review of Political Science 5 (2002). See also the discussion concerning the choice between logit and linear regression by Ottar Hellevik, “Linear Versus Logistic Regression When the Dependent Variable Is a Dichotomy,” Quality & Quantity 43, no. 1 (2009). Hellevik shows that even with respect to significance tests the results are very similar, and there is no systematic over- or underestimation. Robustness checks with alternative model specification (e.g. multilevel ordered logit) were also conducted, but the findings for individual coefficients were equivalent, as well as changes in coefficients when controls or sample specifications are altered. As the results are robust with respect to these alternative model specifications, the more simple to interpret models are presented in the article.

30. See for example Dolan. for a discussion on measures that may lead to a gender bias; and Robert C Luskin and John G Bullock, “‘Don’t Know’ Means ‘Don’t Know’: Dk Responses and the Public’s Level of Political Knowledge,” ibid., no. 02. for a discussion of how response categories are valued.

31. See for instance Mats Utas, ed. African Conflicts and Informal Power: Big Men and Networks (London: Zed Books, 2012).

32. Stuart Henry and Mark M. Lanier, “The Prism of Crime: Arguments for an Integrated Definition of Crime,” Justice Quarterly 15, no. 4 (1998); see also Miriam Gur-Arye, “The Nature of Crime: A Synthesis, Following the Three Perspectives Offered in the Grammar of Criminal Law,” Criminal Justice Ethics 27, no. 1 (2008).

33. For a discussion of how violence can be defined, see Keith Krause, “Beyond Definition: Violence in a Global Perspective,” Global Crime 10, no. 4 (2009).

34. This may seem like the experience of these crimes is uncommon. However, if we compare the amount of people who report experiencing a certain crime in the last year, in Sweden for instance, we see that the occurrence is quite extreme as seen through the Afrobarometer data. The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention note that 1 per cent of households in Sweden had been burglarised during 2015, and 2 per cent of the population had been assaulted during 2015 (based on survey data).

35. As the survey was conducted through a face-to-face interview, literacy is not a prerequisite for participating in the survey.

36. The hypotheses were also tested using a dummy dependent variable (multilevel logit), using only the response to being able to identify the MP correctly, as well as using the per cent correct (with three categories) with OLS and fixed effects, as well as multilevel ordered logit. Again, the results are robust to these alternative specifications.

37. UNODC, 9.

38. The literature on election violence and its consequences is a burgeoning field, see e.g. Vera Mironova and Sam Whitt, “Social Norms after Conflict Exposure and Victimization by Violence: Experimental Evidence from Kosovo,” British Journal of Political Science 48, no. 3 (2018): 749-765; John Ishiyama, Amalia Pulido Gomez, and Brandon Stewart, “Does Conflict Lead to Ethnic Particularism? Electoral Violence and Ethnicity in Kenya 2005–2008,” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 22, no. 3 (2016); Anna Getmansky and Thomas Zeitzoff, “Terrorism and Voting: The Effect of Rocket Threat on Voting in Israeli Elections,” American Political Science Review 108, no. 3 (2014); Johanna Söderström, “Fear of electoral violence and its impact on political knowledge in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Political Studies 66, no. 4 (2018): 869–886. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0032321717742835.

39. Mullainathan and Shafir.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics.