ABSTRACT

Punishment is crucial to maintain contribution and to prevent defection in societies. Previous research has shown in small groups that cooperation drops (defection rises) and rises (defection drops) immediately when punishment disappears and reappears. I will discuss this effect for large groups (societies), real-world environment in the form of the absence of policing. On the contrary to small group experiments, there are contribution delays and defection delays following punishment disappearance and reappearance. The length of these delays varies and seems to depend on aspects like trust, transparency, media-behavior, or democratic affection. All these aspects have politico-economic implications.

Introduction

Our societies are based on public goods contribution and cooperation as well as the prevention of defection. For that purpose, they require a functioning punishment system. Policing is one of the key instruments which an institutional punisher has for that purpose. In this article, I want to shed light on the disappearance and reappearance of institutional punishment – here in the form of absent policing – and the effect on contribution and defection. I further discuss possible implications on the democratic order of a country. Very often we take functioning punishment systems as well as the citizens’ readiness to contribute to public goods for granted. But what happens if they disappear?

I show four example examples with criminal lawlessness like theft, riots, murder, etc., arising after the disappearance of policing (institutional punishment). These criminal activities primarily harm the targeted victims, but they also harm public goods. They turn the public space in a dystopian place preventing other citizens from free movement and slow down the economic as well as social activities. Further, they spread general fear among the society. All these aspects allow to analyze the occurrences in a public goods framework.

Different studies have shown that the disappearance of punishment lowers the contribution and that the reappearance of the same increases the contribution to public goodsFootnote1. According to Fehr and Gächter, cooperation can emerge when “altruistic punishment is possible”.Footnote2 Further, the authors illustrated that the sudden disappearance or reappearance of punishment leads to an almost symmetrical and immediate decrease and re-increase of cooperation.Footnote3 Raising these considerations on large-group level and real-world environment means that the institutional punisher (the state including all its instruments), who is supposed to protect its citizens from defection, stops punishing defectors. In small group lab-experiments we have transparency, certainty, and clear rules. Larger groups, however, are marked by different trust-levels in the institutional punisher, principal-agent problems, different levels of transparency, democratization, motivations of the political actors and citizens as well as altering media-behavior. In the following, I discuss some differences between small and large groups. The four examples further down show that there are delays in contribution levels in reaction to punishment disappearance and reappearance. Contribution can be articulated, for instance, in form of system support, public opinion about the regime, election results, peer punishment in substitution of the missing institutional punishment example. These delays can have politico-economic implications and influence the democratic order of a country. But before discussing these examples I elaborate a conceptual model and discuss some possible drivers of these delays.

Disappearance of punishment in large groups

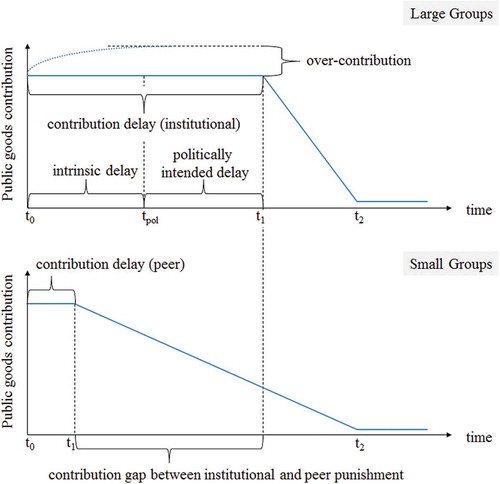

In , I illustrate the decline of public goods contribution (or cooperation) when punishment disappears. Thereby I compare two different punishment setups, institutional punishment in large and peer punishment in small groups. Let’s start with the example of peer punishment in small groups in the lower part of . In t0 the peers stop punishing. Following the Fehr/Gächter model, in small groups the public goods contribution decreases quickly wherefore in this case the contribution delay is very small. The contribution delay shall be defined as the time lag between the moment where punishment disappears until contribution starts to decrease. For very small groups, transparency and no punishment reputation it should turn against 0. The beginning of the decline of the public goods contribution is marked by t1 and its complete disappearance by t2. Here I assume a longer contribution delay as well as a smoother decline of contribution as the Fehr/Gächter model would suggest. That’s because peer punishment setups in the real world are predominantly present in societies composed out of rather small sub-groups and clusters. The simultaneous and sudden disappearance of all peer punishers’ punishment activities might not occur in reality; it will disappear smoother. It is further unlikely that all contributors decrease their public goods contribution with the same speed following the disappearance of punishment. Both take a while to spread through the society.

On the contrary, I assume larger societies with an institutional punishment regime to have a longer contribution delay what was already indicated by Fehr and Fischbacher.Footnote4 To explain this longer delay I divided that it in two parts, an intrinsic delay (tpol-t0) and a politically intended delay (t1-tpol). In the political reality, the two blend into each other and it can be difficult to separate them. The intrinsic delay is longer than under peer punishment which can have different reasons. First, large group institutional punishment comes along with hierarchical structures. These societies are characterized by information asymmetries which make that the information of non-punishment needs to trickle down to the contributors. Second, the institutional punishers (the agents)Footnote5 enjoy, if established since long time, their contributors’ (the principals) trust. This trust is supported by welfare politics and different kinds of self-promotions of the politicians. Trust might lead the principals to lower the vigilance over the agents.Footnote6 That, in consequence, should extend the contribution delay – meaning that societies with a punishment regime of high reputation maintain contribution for a while although the punisher has stopped punishment.Footnote7 Closely linked to the trust between principals and agents is the behavioral motivation of the latter.Footnote8 Trust of the citizens in the politicians’ behavior usually follows from the perception of good motivations of the agents (the politicians) to fulfill their duty. However, if the trust in these motivations is illusive (adverse selection or moral hazard), the contribution delay can be longer. But once the citizens discover this illusion the contribution should decline much faster.

Further, societies can generate an in-group preference which causes hesitation in acknowledging a possible dysfunction of the own (reward and punishment) system rather than external causes of any sort.Footnote9 We will see this aspect in a weak form in the first and even stronger in the last example. Another aspect is that peer and institutional punishment are sensitive to noise.Footnote10 But additionally, to the possible noise between the punisher and the defector in peer punishment, institutional punishment can suffer from noise and information asymmetries between the principal (the citizens) and the agent (the politicians being the institutional punisher).Footnote11 Monitoring of other actors’ behavior is more difficult in larger groupsFootnote12 as transparency is likely to decrease. Lack of transparency also decreases the citizens’ readiness for public goods contribution and to support the government.Footnote13 These considerations, in turn, make it necessary to take politico-economic aspects, adverse selectionFootnote14 or moral hazard of the institutional punishers into account. Politicians have the means to seed confusion about the reasons of the disappearing punishment and/or the rising defection. Also, fear mongering with an apparent out-group threat (see the Boston and Turkish example) or nationalist mythsFootnote15 (see the Turkish example) could help increasing the cooperators’ readiness to public goods contribution.Footnote16 These instruments cause the politically intended delay discussed hereafter more in depth. As the institutional punisher is usually in possession or in control of a media system, he can easily use it for own purposes. Nevertheless, the decline of contribution should be even sharper – a kind of impulsive uproar – once the contributors realize that the confusion was seeded by intention.

The politically intended delay describes all measures which institutional punishers actively apply to extend the contribution delay for their own advantage. The notion ‘institutional punisher’ comprises all actors belonging to or profiting from the respective regime. In the real world that includes politicians, bureaucrats, civil servants, employees of state-run or state-protected entities, etc. The instruments which they might apply range from simple self-promotion, lobbying, disinformation, confusion to fear mongering or any other type of malicious tactics. Retarding the contribution delay provides several advantages to the institutional punishers. First, they achieve a greater margin to operate without creating political unrest among the contributors. Second, by stopping punishment without losing contributions they retrieve additional funding which they can use for own purposes including to satisfy their respective supporters.

Adapting this concept to the idea of hierarchical societies it is important to note that this political intention does not only come from the political elite. It rather comprises several vertical levels fading out toward the lower end of the respective society. To better understand these considerations we can use the following illustration (). In small groups, the punisher is directly linked to the peers and each peer is a punisher of all others, respectively. Each peer is principal and agent of the other peers.Footnote17 As the groups grow the linkages become more complex, indirect, and hierarchical.Footnote18 In larger societies, we have separated principal (citizens) and agent roles (government representatives).Footnote19 There are different principal-agent chainsFootnote20; the citizens (principals), the elected politicians (agents) on top of and their civil servants (agents), and police men (agents). In these chains, each punisher (PUN) is the agent of the previous and the principal of the next. In this constellation, if punishment disappears, it is not always immediately clear for the peers who, where, and why the punishment system failed. That is an intrinsic part of this large-group multi-layer constellation even without any malicious action from anybody. It causes the mentioned intrinsic delay – the time which the citizens need to find out who is to be blamed.

Obviously, each of the involved punishment layers has an interest not to fall into disfavor with the peers. So, they’ll try not to inform or even to disinform the peers about the actual causes of the punishment disappearance which results in a longer politically intended delay. We would expect that the existence of press, television, social media, internet, telephony, etc., would reduce either of the delays. But they are not always as free and independent as necessary, and/or the peers are not always and equally perceptive for the available information. The overall situation can be opaque and the peers’ (=citizens) reaction can be peasant. I will call the process of avoiding to fall in disfavor of the principals and to draw the attention on other actors as “blame assignment dynamics”. By this, I mean the influencing of the collective perception of who is to be held responsible for the bad situation. Besides the government (institutional punisher) there are actors like the media, the police, political parties, citizens’ groups and others who can influence this process. Depending on who gets the blame assigned, the contribution delay can be shorter or longer. It is longer if the attention is drawn on the misbehavior of the police not fulfilling its duty (see the Boston example). It is also longer if an external threat is made responsible (the turmoil in Europe in the Boston example or the terrorist threat in the Turkish example). In the Brazil example, in change, the people attributed a large part of the responsibility to the government.

Longer contribution delays also result from high regime support levels which follow from the institutional structure or the culture.Footnote21 This leads to longer patience of the citizens with the government in case of temporary dysfunctionsFootnote22 causing longer contribution delays when punishment disappears. These institutional structures determine the principal-agent chains described above. System support also alters with the level of democratization.Footnote23 One of the reasons is the democratic affection argument of Huhe and Tang.Footnote24 High affection citizens are very attentive on who is to be blamed or supported. Democratic affection can extend or shorten the contribution delay. The authors argue that citizens in a less democratic regime can be more critical on their regimes (higher affection) then the citizens in democracies (lower affection). That, in consequence, could mean that societies which are drifting away from democracy toward autocracy still show high regime support, meaning longer contribution delays. So, longer contribution delays can be harmful for democracies if they are driven by low democracy affection.

Reappearance of punishment in large groups

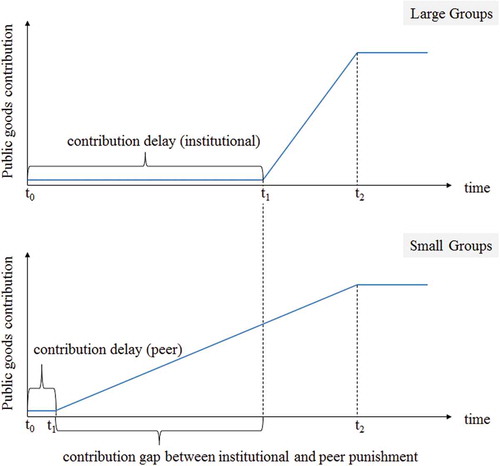

After discussing punishment disappearance, I now come to punishment reappearance. Also, here I distinguish between a small group peer and a large group institutional punishment regime. In , t0 is the point where peers or institutional punishers start punishing. In t1 the cooperators start contributing and in t2 the full contribution level is achieved. Following the Fehr/Gächter model, the contribution delay in small groups is almost zero. Further, the rise in contribution is similarly quick as its decline after the punishment disappearance.

In real-world situations, we need to include the political and historical environment of the respective society and the a-priori-reputation of the punishers. The contribution delay is shorter if the reputation of the punisher is high.Footnote25 The same is valid if he rewards at the beginning more than he punishes and starts to punish later.Footnote26 Fehr and Gächter distinguish between situations where punishment is allowed and where it is not. However, in the real world, there is always some kind of reward and punishment system in place. Even when not doing anything in reaction to a defector’s behavior, we silently approve the behavior, reward the defector, and punish affected thirds. We let the defector get away with the unfairly obtained fruits of his defection. So, when discussing the reappearance of punishment it can’t be dissolved from the question what kind of punishment regime had been in place before t0. We need to take into consideration whether it was peer or institutional punishment, its strength and acceptance level among all members and possibly disturbing environmentFootnote27 in general.

Further, as reputation plays a role when punishment disappears, it also plays a role when punishment reappears. When a punisher without reputation restarts punishing, cooperation will remain low for a while until the cooperators begin to trust him. All this influences the lengths of the contribution delay. A dilemma of institutional punishment reappearance is that it needs to be funded upfront. But punishment is required to foster cooperation whose revenues, in turn, are supposed to finance the institutional punisher. Nobody is ready to provide this funding by his contribution until the institutional punisher has shown to be trustworthy. On the contrary, in the case of peer punishment the delays are shorter, peers are ready to assume punishment costs privately – so, the problem of financing the reappearance of punishment is much lower on small group peer level.

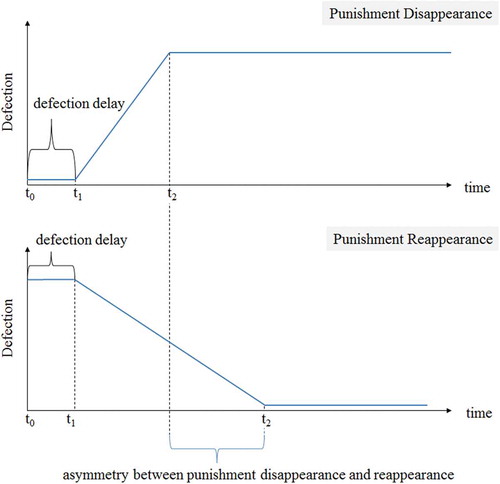

Another aspect is the reaction of defectors on the disappearance and reappearance of punishment – the defection delay. This delay reflects the time between punishment reappearance and the start of defection decline; it also depends on the already mentioned reputation and information availability. But defectors and contributors do not necessarily have the same levels of trust and information with respect to the punisher. Defectors tend to be better informed and organized what might cause significant differences between contribution and defection delays (). Further, the defection delay and its steepness can be different in case of punishment disappearance as it is for punishment reappearance.

Disappearance and reappearance of punishment – some examples

There are not many cases of punishment disappearance with useful chronological and numerical data. This might be due to the politico-economic nature of the subject. The involved parties have little interest in sharing exact information about those incidences. In the following, I discuss some examples.

The Boston police strike 1919

On Tuesday, September 9, 1919, the Boston policemen went on strike. Their absence was immediately prompted by days of riots on the streets of the city (defection). The strikes followed a dispute between government and police union. The upcoming of a possible strike was reported in the press days before it occurred.Footnote28 Hence, it was anticipated by the government, the defectors and the citizens. On Sunday, September 14, the situation was reported to be under control againFootnote29 by using military forces and voluntary policemen.

The Boston citizens, in addition to their tax paying, were ready to provide (and finance) almost immediately numerous peer punishers (the mentioned voluntary policemen) to maintain public order.Footnote30 So, instead of reducing the contribution, the citizens increased it even; I call this over-contribution (see ). Further, there was seemingly no defection delay. Further, the government, supported by the press, successfully managed to put the blame on the striking policemen. It also insinuated an external threat (politically intended delay) by hinting on the ideological turmoil in Europe at the time.Footnote31 This fear mongering, the blame assignment to the policemen, and the long democratic tradition might have been the reason for the observed over-contribution.

Summarizing this example, there was no defection delay which might be explainable by the fact that the disappearance of punishment was a priori known by the defectors – so, they were all prepared. Further, there was a contribution delay outlasting the whole strike period. The public opinion was in favor of the government what caused increasing instead of decreasing contribution.

The police strike in Argentina 2013

Between December 3 and December 13, 2013, the provincial police in 20 out of 24 Argentinean provinces went on strike. The disappearance of police forces from the streets caused an immediate rise of defection (no defection delay) in form of looting causing hundreds of injured and several dead – the most violent riots since Argentina returned to democracy in 1983. Over the next days, military troops were deployed to most important hotspots of the country, but looting went on until the provincial governments raised the police officials’ salaries around December 10. There was a vital blame assignment dynamic observable; the government electively put the blame on the officials, an unspecified group of persons who “deliberate actions aimed to inspire chaos and anxiety”,Footnote32 and on the opposition for not denouncing the occurrences.

The central government proposed a police reform containing the ‘decentralization’Footnote33 of the provincial polices. This could be seen in the context of the alleged corruption problems of the provincial police and the reported misbehavior of their officers. On the other hand, the provincial polices, controlled by the provincial governors, count about 100.000 officials meanwhile the federal police, controlled by the central government, just counts about 40.000 officials. So, the proposed police reform could also follow from a balance-of-power calculus of the central government vis-à-vis their political rivals in the provinces.

There were no signs of a contribution decline in form of manifestations. On December 10, thousands of ArgentineansFootnote34 celebrated Argentina’s 30 years of democracy; this event could have been used to demonstrate against this situation. Instead, in some areas armed “middle class citizens” were reported of protecting buildings themselves.Footnote35 This could be spontaneous self-defense or a soft form of over-contribution. The reason for the absence of manifestations is difficult to define. I speculate that it could be a combination out of confusion of who is to be blamed, the opposition’s call to block the 30th-anniversary-festivities of the government and the fear about the security situation in general as well as the ambiguous fame of the Argentinean police in particular.Footnote36 This example has a clear politico-economic aspect as the disappearance of policing takes place in an unstable political system.

The Espirito Santo (Brazil) police strike 2017

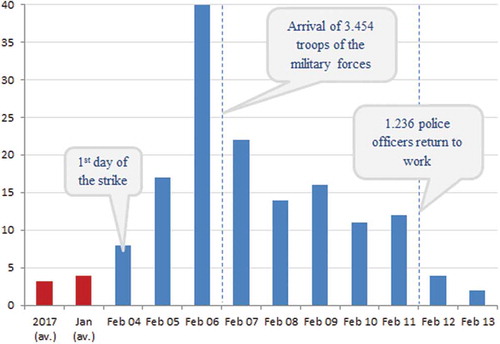

The police strike in Brazil’s federal state Espirito Santo provides pretty good chronological and numerical data. On February 4, 2017, the military police of Espirito Santo went on strike. Following to that, the homicide rates increased exponentially over the subsequent days until the arrival of 3.454 troops of the Brazilian military.Footnote37 After three days of increasing and seven days of decreasing homicide numbers the situation was again under control ().

In this example, the increase and decrease of defection following the disappearance and reappearance of PSPinst were asymmetric. The decrease was longer than the increase of defection despite of enormous institutional punishment efforts in form of the military deployment. Further, there was practically no defection delay. The defectors reacted immediately on the punishment disappearance or reappearance. However, the increase of defection (t2-t1 in upper part) was steeper than the following decrease (t2-t1 in lower part).

On February 7, some citizens from the neighborhood demonstrated in front of the General Command office of the Military Police in Vitoria demanding the police officers to resume their duty.Footnote39 On February 12, large-scale manifestations of the so-called “Caminhada das famílias pela paz” (engl. “families” march for peace’)Footnote40 started in different cities of Espirito Santo. These manifestations expressed on one side the people’s disapproval with the defectors. On the other side, it showed their unrest with the institutional punisher (the police) and their readiness to withdraw their democratic support from the government; this moment indicates the contribution delay (t2-t1 in upper part). So, we have no defection delay on the punishment disappearance, but an estimated contribution delay of 8 days in this example (leaving beside the small manifestation of February 7). The contributors apparently needed time to get sufficiently organized. Without the return of 1.236 police officersFootnote41 to their workplaces the defection levels would most likely have remained above the levels of before the strike.

The blame assignment by the press was rather balanced to both, the striking policemen and the government for not reaching an agreement with them. More empirical research could help to analyze the different contribution and defection delays as well as the speed of increase/decrease in dependency of the environment (i.e. the media setup, predominant socio-political ideology, etc.).

The looming violence in Turkey between 2015 and 2017

The following example has a strong politico-economic element. Meanwhile, the previous examples did not come along with any lasting change of the democratic order as such, this example did. It describes Turkey in the period from 2015 to 2017. During the summer 2015, Turkish newspapers were several times attacked by an angry mob meanwhile the police arrived “late” on site and the perpetrators have not been investigated.Footnote42 Further, an explosion occurred at an HDP party election rally in Diyarbakir in June 2015 two days before the parliamentary elections. The cause and those who were responsible for it have not been investigated.Footnote43 This was followed over the next 18 months by an increase of violence with numerous terror attacks and assassinations. Only beginning of 2017, after the attack on the Istanbul nightclub Reina, the government came under pressure for “creating an atmosphere in which a religious fanatic could get away with murder”.Footnote44 So, defectors realized in 2015 that the institutional punisher (police) apparently arrived ‘late’Footnote45 or delayed its activities (in form of investigation and prosecution). Thus, it opened a space for non-punished defection.

Beginning of 2017, the police forces resumed their investigation and prosecution activities (reappearance of punishment) with numerous arrests and they actively reported about them.Footnote46 However, only 15%Footnote47 of the detained people over “suspected links to ISIS” were arrested. Thus, there was even a certain institutional over-punishment in the year 2017. The defection delay following the punishment reappearance is difficult to define. Since there were no major attacks (defection) against civilians in 2017 after the nightclub Reina Day attack the defection delay could be vaguely estimated as close to zero. Though the security forces apparently have prevented a couple of attacks by the raids they carried out.Footnote48 So, supposedly, there were some intended but thwarted defections.

During this time, the majority of the citizens still supported the government with their votes (the elections November 2015), their taxes and obedience to the legal system as a whole. This example shows that contribution delays are sometimes driven by (too much) trust in the institutional punisher, fearFootnote49 and an information asymmetry about the actual situation regarding the defection and the (missing) institutional punishment. The Turkish politicians rather confused than informed the citizens about the origin of the attacks and its apparent institutional punishment activities in response. They electively attributed the attacks to ISIS, Kurdish groups and later to the Gülen movement; also for attacks which nobody or another group had claimed responsibility.Footnote50 All that was culminated by the idea that even the U.S. might have been, somehow, involved in one or the other attack.Footnote51 So, these constellations caused an estimated contribution delay of about 18 months (June 2015 to January 2017). On the contrary, I could vaguely estimate the defection delay to be about 6 weeks (the time between the attacks of June 5 and July 20, 2015).

During these 18 months, Turkey experienced significant occurrences: hundreds of victims of terror attacks and parliamentary elections (June 2015) whose results were not recognized by the government. Further, the repeated parliamentary elections (November 2015) with more government-favorable results which are an expression of social conformity,Footnote52 a failed coup d’état (July 2016) and a state-of-emergency declaration (July 2016). The latter was followed by the closure of media institutions, the dismissal of thousands of civil servants, and the imprisonment of thousands of citizens. Till the end of the state-of-emergency on July 19, 2018, these figures increased to about 130.000 dismissed public officials and around 77.000 pretrial detentions.Footnote53 More than 18.600 officialsFootnote54 were dismissed in the last two weeks of the state-of-emergency. This run-up of policing activities as well as the anti-terror lawFootnote55 approved by the Turkish parliament days after the state-of-emergency ended, reminds to the ending of the French state-of-emergency in 2017. The content of the French law against terrorism was less problematic, but the pattern of “terminating the state-of-emergency and ‘normalizing’ part of it in form of permanent law” was the same.Footnote56

In this example, the absence of institutional punishment in form of missing police investigation and prosecution did not follow from a police strike. It was rather that the ‘atmosphere’Footnote57 of non-prosecution (Summer 2015 to January 2017) of the violent acts followed by intensified policing (July 2016 to July 2018) against suspects and opponents in general. This generated a situation where the force-of-law was still there – at least in the political narrative – but, to paraphrase Giorgio Agamben, “the force-of-law and its application were separated, and the pure force realized instead”.Footnote58

Discussion

I’ve modeled the increase and decrease of contribution and defection following the disappearance and reappearance of institutional punishment in comparison to peer punishment. I discussed the model with four examples of disappearance and reappearance of policing. In accordance to the model, the contribution delay in case of institutional punishment disappearance in large groups was remarkably longer than in small group peer punishment.

The lack of transparent information, the complicated principal–agent relations, and the higher complexity of the daily processes in large groups make it more difficult for citizens to evaluate the situation. The contribution delays are longer in societies with high regime support levels following either a cultural predisposition or the institutional setup. The peers are ready to defend the “Social Contract” they (believe to) have with the government, despite of its temporary inability to fulfil it. They do this even by increasing their contribution (over-contribution) in form of voluntary peer punishment (see the Argentinean and Boston example).

Citizens have trust in the institutional punisher to fulfil his duty depends on his reputation. This, in turn, is higher for old and long-serving punishers. Good reputation of the institutional punisher fosters credulity in the same among the peers. Hence, the peers might not want to recognize the possible moral hazard of their elected institutional punishers. They might be receptive for the ideas of possible external threats as the Boston and Turkish example have shown. Peer-level contributors are usually not organized. They need time to coordinate their activities and to overcome the collective action problem like manifestations (see the Brazilian example).

The democratic affection was different in the four examples. Meanwhile the Boston citizens staffed a police force out of volunteers, the Brazilian citizens organized manifestations. In the Argentinean example the democratic affection is hard to determine. In the Turkish example, the constitutionally doubtful repetition of the elections, their results and the long contribution delay showed that the democratic affection was very low.

The contribution delay and over-contribution depend pretty much on what responsibility the citizens suppose the government to have regarding the increase of defection. In the Boston example, citizens were in favor of the government what lead to over-contribution. In the Brazilian example the citizens’ manifestations were directed against politicians, policemen, and defectors alike – no over-contribution was observed. In the Turkish example, we have seen an opinion swop of the supposed responsibility for the increased violence (defection). The citizens were about to turn from over-contribution (in form of better election results for the government the 2nd parliamentary elections in November 2015) to a drop of contribution in early 2017.Footnote59 So, the citizens’ contribution behavior follows their opinion about who is supposedly responsible. There is a possibility of the institutional punisher to influence the public opinion – the blame assignment dynamic – about the disappearing punishment and the defection increase (see the examples of Boston and Turkey). Thereby, the institutional punisher influences the contribution delay.

The defection delay in large groups is significantly shorter than the contribution delay – in some cases almost zero. This could have the following reasons. First, defectors get their benefits from cheating the social contract; contributors from fulfilling the same. Defectors wait for the punisher to stop punishing; contributors (simply) trust that the punisher does his job. Hence, the attention of (potential) defectors regarding the punisher’s behavior is higher contributors’ attention. Second, the organization level of defectors (i.e. organized crime) is higher as it is for contributors. Further, the defection delay difference between punishment disappearance and reappearance indicates that not all instruments of the institutional punisher are equally suitable. Assault troops (in the example of Brazil) are able to curb street crime, but not the silently working organized crime.

Since there are obviously winners and losers following the punishment disappearance and its delays, we must take politico-economic aspects into account. First, there are incentives for a possible collusion between the institutional punisher and defectors.Footnote60 Second, there is a possibility that the government (institutional punisher) abuses this dynamic to increase the power asymmetries between itself and the citizens.

So, both delays depend on the information availability, the attention, and the organization level of contributors and defectors, and other parameters as outlined. The exact definition of the delays (t1-t0 in , and ) and steepness (t2-t1 in , and ) in empirical analyses is not easy. Rather than defining the exact length, it was important to show the asymmetries between small and large groups, peer and institutional punishment, contribution and defection, disappearance, and reappearance. Further empirical research is needed to deeper analyze the different aspects.

Figure 6. Homicides following the police strike in Espirito Santo (Brazil) in February 2017.Footnote38

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. M. Casari and L. Luini, “Cooperation Under Alternative Punishment Institutions: An Experiment,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 71, no. 2 (2009): 273–82; O. Gürerk, B. Rockenbach, and I. Wolff, “The Effects of Punishment in Dynamic Public-Good Games.” Available at SSRN 1589362, 2010; C. Hilbe and A. Traulsen, “Emergence of Responsible Sanctions Without Second Order Free Riders, Antisocial Punishment or Spite,” Scientific Reports 2, (2012): 458.

2. E. Fehr and S. Gächter, “Altruistic Punishment in Humans,” Nature 415, no. 6868 (2002): 137–40.

3. Ibid., 135.

4. E. Fehr and U. Fischbacher, “Third-Party Punishment and Social Norms,” Evolution and Human Behavior 25, no. 2 (2004): 63–87.

5. T. Besley, Principled Agents?: The Political Economy of Good Government (Oxford University Press on Demand, 2006). See p. 98 for this principal (citizens) and agent (government) definition.

6. B. S. Frey, “Does Monitoring Increase Work Effort? The Rivalry with Trust and Loyalty,” Economic Inquiry 31, no. 4 (1993): 663–70.

7. M. Dos Santos, D. J. Rankin, and C. Wedekind, “Human Cooperation Based on Punishment Reputation,” Evolution 67, no. 8 (2013): 2446–50; M. Dos Santos and C. Wedekind, “Reputation Based on Punishment Rather than Generosity Allows for Evolution of Cooperation in Sizable Groups,” Evolution and Human Behavior 36, no. 1 (2015): 59–64.

8. B. S. Frey, Not Just for the Money vol. 748, (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1997).

9. J. M. Robbins and J. I. Krueger, “Social Projection to Ingroups and Outgroups: A Review and Meta-Analysis,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 9, no. 1 (2005): 32–47; D. Balliet, J. Wu, and C. K. De Dreu, “Ingroup Favoritism in Cooperation: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 140, no. 6 (2014): 1556.

10. S. Fischer, K. R. Grechenig, and N. Meier, “Cooperation Under Punishment: Imperfect Information Destroys it and Centralizing Punishment does not Help,” MPI Collective Goods Preprint (06, 2013).

11. M. R. Frascatore, “Collusion in a Three-Tier Hierarchy: Credible Beliefs and Pure Self-Interest,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 34, no. 3 (1998): 459–75.

12. J. P. Carpenter, “Punishing Free-Riders: How Group Size Affects Mutual Monitoring and the Provision of Public Goods,” Games and Economic Behavior 60, no. 1 (2007): 31–51.

13. E. S. Dickson, S. C. Gordon, and G. A. Huber, “Institutional Sources of Legitimate Authority: An Experimental Investigation,” American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 1 (2015): 109–27.

14. B. Caplan, The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies (Princeton University Press, 2011).

15. J. J. Mearsheimer, Why Leaders Lie: The Truth About Lying in International Politics (Oxford University Press, 2011).

16. L. Goette, D. Huffman, S. Meier, and M. Sutter, “Group Membership, Competition, and Altruistic Versus Antisocial Punishment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Army Groups.” (2010).

17. B. Toelstede, “Social Hierarchies in Democracies and Authoritarianism: The Balance between Power Asymmetries and Principal-Agent Chains,” Rationality and Society (2020): 1043463120904051. P.5f.

18. P. J. Richerson, and R. Boyd, “Institutional Evolution in the Holocene: The Rise of Complex Societies,” In Proceedings-British Academy, vol. 110 (Oxford University Press Inc, January, 2001), 197–234.

19. B. Toelstede, “Social Hierarchies in Democracies and Authoritarianism: The Balance between Power Asymmetries and Principal-Agent Chains,” Rationality and Society (2020): 1043463120904051. P.6ff.

20. Ibid.

21. W. Mishler and R. Rose, “What are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies,” Comparative Political Studies 34, no. 1 (2001): 30–62; W. Mishler and R. Rose, “What are the Political Consequences of Trust? A Test of Cultural and Institutional Theories in Russia,” Comparative Political Studies 38, no. 9 (2005): 1050–78.

22. M. Hooghe and S. Zmerli, Political Trust: Why Context Matters (London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2011).

23. M. Mauk, “Regime Support and its Sources in Democracies and Autocracies” (In Conference Paper and Talk, The Political Sociology of Trust, 2017).

24. N. Huhe and M. Tang, “Contingent Instrumental and Intrinsic Support: Exploring Regime Support in Asia,” Political Studies 65, no. 1 (2017): 161–78.

25. E. Fehr and S. Gächter, “Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments,” American Economic Review (1999/2000): 980–94; The article was published in 2000, but there is also a more comprehensive version of the article from (1999) available on the internet.

26. X. Chen, T. Sasaki, Å. Brännström, and U. Dieckmann, “First Carrot, then Stick: How the Adaptive Hybridization of Incentives Promotes Cooperation,” Journal of The Royal Society Interface 12, no. 102 (2015): 20140935.

27. O. P. Hauser, M. A. Nowak, and D. G. Rand, “Punishment does not Promote Cooperation under Exploration Dynamics when Anti-Social Punishment is Possible,” Journal of Theoretical Biology 360, (2014): 163–71.

28. The New York Times (1919/1), “Boston Police Organize,” August 10, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2LASfND (accessed July 22, 2018).

29. The New York Times (1919/3), “Bay State Governor Firm,” September 14, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2mD6BlM (accessed July 22, 2018).

30. The New York Times (1919/2), “The Boston Police Strike,” September 10, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2JKYY5J (accessed July 22, 2018); The New York Times (1919/3), “Bay State Governor Firm,” September 14, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2mD6BlM (accessed July 22, 2018).

31. The New York Times (1919/2), “The Boston Police Strike,” September 10, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2JKYY5J (accessed July 22, 2018); The New York Times (1919/3), “Bay State Governor Firm,” September 14, 1919. The New York Times. Source: https://nyti.ms/2mD6BlM (accessed July 22, 2018).

32. The Economist, “Law and Disorder. The Economist,” December 11, 2013. Source: https://www.economist.com/americas-view/2013/12/11/law-and-disorder (accessed July 16, 2018).

33. Alejandro Rebossio, “Argentina se plantea una reforma policial tras los saqueos,” El País. December 12, 2013. Source: https://elpais.com/internacional/2013/12/12/actualidad/1386875007_478940.html (accessed July 16, 2018).

34. The Economist, “Law and Disorder. The Economist,” December 11, 2013. Source: https://www.economist.com/americas-view/2013/12/11/law-and-disorder (accessed July 16, 2018).

35. Alejandro Rebossio, “La mayoría roba, pero uno saquea para dar de comer a los chiquitos,” El País. December 11, 2013. Source: https://elpais.com/internacional/2013/12/11/actualidad/1386787710_193806.html (accessed July 16, 2018).

36. L. Glanc, “Caught between Soldiers and Police Officers: Police Violence in Contemporary Argentina,” Policing and Society 24, no. 4 (2014): 479–96; Human Rights Watch (2018/1), “Argentina – Country Report 2018,” Human Rights Watch, New York. Source: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/argentina_2.pdf (accessed July 22, 2018).

37. Linhares, Carolina/Heitor, Leonardo, “Governo do Espírito Santo acusa 703 PMs amotinados por crime military,” Folha de São Paulo. February 10, 2017. Source: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2017/02/1857545-governo-do-espirito-santo-acusa-703-pms-amotinados-por-crime-militar.shtml (accessed July 22, 2018).

38. Folha de São Paulo [Editorial], “Homicídios no Espírito Santo caem após parte da PM voltar às ruas,” Folha de São Paulo, February 12, 2017. Source: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2017/02/1858168-homicidios-no-espirito-santo-caem-apos-parte-da-pm-voltar-as-ruas.shtml (accessed July 22, 2018); Rafaela Lara, “Ampla maioria de mortos no ES era homem e vivia na Grande Vitória,” Veja, February 14, 2017. Source: https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/ampla-maioria-de-mortos-no-es-era-homem-e-vivia-na-grande-vitoria/ (accessed July 22, 2018); Carolina Linhares and Leonardo Heitor, “Governo do Espírito Santo acusa 703 PMs amotinados por crime military,” Folha de São Paulo, February 10, 2017. Source: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2017/02/1857545-governo-do-espirito-santo-acusa-703-pms-amotinados-por-crime-militar.shtml (accessed July 22, 2018).

39. Veja [editorial office], “Moradores protestam pedindo a volta da PM às ruas de Vitória,” Veja, February 7, 2017. Source: https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/moradores-protestam-pedindo-a-volta-da-pm-as-ruas-de-vitoria/ (accessed July 22, 2018).

40. Heloísa Mendonça, “A vida começa a voltar às ruas de Vitória,” February 13, 2017. El País Brasil. Source: https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/02/12/politica/1486909811_192503.html (accessed July 22, 2018).

41. Folha de São Paulo [Editorial], “Homicídios no Espírito Santo caem após parte da PM voltar às ruas,” Folha de São Paulo. February 12, 2017. Source: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2017/02/1858168-homicidios-no-espirito-santo-caem-apos-parte-da-pm-voltar-as-ruas.shtml (accessed July 22, 2018).

42. Ceylan Yeginsu, (2015/2), “Opposition Journalists Under Assault in Turkey.” The New York Times, September 17, 2015. Source: (accessed July 22, 2018).

43. Ceylan Yeginsu, (2015/1), “Days Before Election in Turkey, Blasts at Rally Kill 2.” The New York Times, June 5, 2016. Source: https://nyti.ms/1FD3ObL (accessed July 22, 2018); Kirsty Major, “Ankara Explosion: Timeline of Bomb Attacks in Turkey between 2015 and 2016,” The Independent, February 17, 2016. Source: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/turkey-blast-two-dead-and-100-injured-after-explosions-hit-kurdish-party-election-rally-10301447.html (accessed July 22, 2018).

44. Andrew Finkel, “Turkey in Grip of Fear as Erdoğan Steps up Post-Terror Attack Crackdown,” The Guardian, January 7, 2017. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/07/turkey-fear-as-crackdown-follows-terror-attack-istanbul-new-years-eve?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (accessed July 22, 2018).

45. Ceylan Yeginsu, (2015/2), “Opposition Journalists Under Assault in Turkey,” The New York Times. September 17, 2015. Source: (accessed July 22, 2018).

46. Hürriyet Daily News, (2018/1), “Nearly 1,500 ISIL Suspects Detained in Istanbul in 2017,” Hürriyet Daily News, January 2, 2018. Source: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/nearly-1-500-isil-suspects-detained-in-istanbul-in-2017-125124 (accessed July 22, 2018); Hürriyet Daily News, (2018/2), “739 Arrested, 4,765 Detained in Turkey’s 2017 Fight against ISIL.” Hürriyet Daily News, January 3, 2018. Source: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/739-arrested-4-765-detained-in-turkeys-2017-fight-against-isil-125193 (accessed July 22, 2018).

47. Ibid.

48. Hürriyet Daily News, (2018/1), “Nearly 1,500 ISIL Suspects Detained in Istanbul in 2017.” Hürriyet Daily News, January 2, 2018. Source: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/nearly-1-500-isil-suspects-detained-in-istanbul-in-2017-125124 (accessed July 22, 2018).

49. Andrew Finkel, “Turkey in Grip of Fear as Erdoğan Steps up Post-Terror attack Crackdown.” The Guardian, January 7, 2017. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/07/turkey-fear-as-crackdown-follows-terror-attack-istanbul-new-years-eve?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (accessed July 22, 2018).

50. Al Jazeera, “ISIL Claims Responsibility for Diyarbakir Car Bomb.” Al Jazeera Media Network, November 5, 2016. Source: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/11/isil-claims-responsibility-diyarbakir-car-bomb-161105035859444.html (accessed January 28, 2017); Kirsty Major, “Ankara Explosion: Timeline of Bomb Attacks in Turkey between 2015 and 2016.” The Independent, February 17, 2016. Source: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/turkey-blast-two-dead-and-100-injured-after-explosions-hit-kurdish-party-election-rally-10301447.html (accessed July 22, 2018); Samuel Osborne, “Does Isis Really “Claim every Terror Attack”? How do we know if a Claim is True?” The Independent, May 4, 2017. Source: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-terror-attack-claim-real-true-legitimate-fake-false-how-to-know-a7701046.html (accessed July 22, 2018).

51. Tim Arango, “In Turkey, U.S. Hand is Seen in Nearly Every Crisis.” The New York Times, January 4, 2017. Source: http://nyti.ms/2j3AhEN (accessed July 22, 2018).

52. B. Toelstede, “How Path-Creating Mechanisms and Structural Lock-Ins Make Societies Drift from Democracy to Authoritarianism,” Rationality and Society 31, no. 2 (2019): 233–62.

53. Human Rights Watch, (2018/2), “Turkey: Normalizing the State of Emergency.” Human Rights Watch, New York. Source: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/07/20/turkey-normalizing-state-emergency (accessed July 22, 2018).

54. Hürriyet Daily News, (2018/3), “State of Emergency Ends Amid Proposal of New Anti-Terror Law.” Hürriyet Daily News, July 18, 2018. Source: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/state-of-emergency-ends-amid-proposal-of-new-anti-terror-law-134715 (accessed July 22, 2018).

55. Human Rights Watch, (2018/2), “Turkey: Normalizing the State of Emergency.” Human Rights Watch, New York. Source: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/07/20/turkey-normalizing-state-emergency (accessed July 22, 2018); Le Monde, « Turquie: le Parlement adopte une loi « antiterroriste » remplaçant l’état d’urgence. » Le Monde, July 25, 2018. Source: https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2018/07/25/turquie-le-parlement-adopte-une-loi-antiterroriste-remplacant-l-etat-d-urgence_5335891_3210.html (accessed July 27, 2018).

56. B. Toelstede, “Democracy Interrupted: The Anti-Social Side of Intensified Policing,” Democracy and Security (2018): 1–13.

57. Andrew Finkel, “Turkey in Grip of Fear as Erdoğan Steps Up Post-Terror Attack Crackdown.” The Guardian, January 7, 2017. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/07/turkey-fear-as-crackdown-follows-terror-attack-istanbul-new-years-eve?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (accessed July 22, 2018).

58. G. Agamben, State of exception, vol. 2 (University of Chicago Press, 2005), 40.

59. Andrew Finkel, “Turkey in Grip of Fear as Erdoğan Steps Up Post-Terror Attack Crackdown.” The Guardian, January 7, 2017. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/07/turkey-fear-as-crackdown-follows-terror-attack-istanbul-new-years-eve?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (accessed July 22, 2018).

60. C. Angelucci and A. Russo, Moral hazard and collusion in hierarchies (Mimeo, 2012).