ABSTRACT

The term “Military Ethical Washing”Footnote1 is used to describe ways in which military ethics clears military organizations from moral responsibility for their actions in a post-national liberal militarism era. Film and television, now even more than in the past, serve as agents of ethics in general, and of military ethics in particular. Using the terms of the “Just War Theory,” the study shows how through processes of De-Politicization and Dis-militarization enhanced by fictional audio-visual narrative representations, narrative films and television dramas express the ethical-liberal turning point of our times, while at the same time using it to ratify national militarism. The process of “Military Ethical Washing” is illustrated in the paper in the Israeli context through cinematic and televised representations of internal targeted assassinations that took place during the constitutive national period of the struggle for Israel’s independence – a case study having critical potential for discussing current military practices and ethical issues being dealt with by the Israeli military, but also relevant to other cases.

Introduction

The paper examines the emergence of “Military Ethical Washing” in an era of liberal militarism in narrative film and television drama. By defining the ethical-liberal turning point, the paper presents the transition from a republican-national discourse to a post-national liberal criticism that led to a double ethical turning point – in the military arena, as well as the cultural one. Through the theoretical framework of the “Just War Theory” and its implementation for the reading of cinematic and televised representations, the paper shows how these theories do not necessarily undermine national militarism, but rather ratify it through processes of De-Politicization and Dis-militarization. A narrative and aesthetic analysis of the Israeli case study involving representations of targeted killings will show how instead of challenging the military ethic, these representations “clean” and “wash” the military from moral responsibility for controversial acts by establishing their moral exceptionality vis-a-vis the demand for a civil, nonmilitary liberal ethic.

Corpus of the study

Representations of internal targeted killings in the Yishuv (the body of Jewish residents in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948) during the struggle for statehood are presented through films that will be defined here as “Underground films” (not in the sense of films that are outside the mainstream in terms of style, genre, or production, but literally films that describe the struggle for independence of pre-State Zionist underground organizations against the British). This corpus of narrative films includes, either extensively or to a limited extent, representations of the main pre-State Jewish underground organizations that struggled against the British Mandate over Palestine. These films appeared in Israeli cinema from its onset, immediately following the establishment of the State. However, with the exception of a few cases, until the 1980s, during the republican national era, these included almost hermetically only representations of the hegemonic underground movement, and accordingly the films were characterized by supportive and unquestioning representations of its operations.Footnote2 Conversely, the corpus of “Underground films” pertaining to the liberal post-national era, produced from 1980 onward, include substantial representations of other, non-hegemonic underground movements as well as representing their operations in a more expansive, more complex and less consensual manner. The corpus of the present study is comprised of six films within this group, offering an explicit or insinuated representation of the phenomenon of internal targeted killings. The films are as follows: Hide and Seek (Dan Wolman, 1980), Rage and Glory (Avi Nesher, 1984), Crossfire (Gideon Ganani, 1989), The Little Traitor (Lynn Roth, 2009), The Fifth Heaven (Dina Zvi-Riklis, 2012), and Tobianski (Riki Shelach, 2014). The corpus also includes three television dramas, formatted either as a television film or a mini-series, produced during the same period and also representing internal targeted killings: the television films Winter Games (Ram Loevy, the Israeli Television, 1988) and Body in the Sand (Riki Shelach, Channel 3, 1999), and the mini-series Eagles (Dror Sabo and Daphna Levin, Hot 3, 2010). The cinematic and televised representations not only share a production period but also formative cultural influences and fictional and stylistic attributes that enable a shared discussion.

Methods

The paper offers an interpretive analysis of cinematic and televised audio-visual narrative text. It proposes a textual examination of narrative and characters constructionFootnote3 alongside a “stylistic analysis” and “aesthetic evaluation”Footnote4 that consider the texts historical context and use interpretative theoretical frameworks.

Structure

The first part of the paper presents its theoretical foundations: the ethical-liberal turning point, cinema and television as agents of a military ethic, and processes of De-Politicization and Dis-militarization as strategies for the creation of “Military Ethical Washing.” The second part presents the Israeli case study of internal targeted killings during the era of the pre-State underground movements. Finally, the third part illustrates the ways in which narrative films and television drama establish the condition of “Military Ethical Washing” by examining representations of internal targeted killings on these media forms during the establishment and impact of the liberal turning point.

The ethical-liberal turning point

A discussion of “Military Ethical Washing” processes requires a presentation of the ethical-liberal turning point that created them. The liberal turning point occurred in the west toward the end of the previous century with the challenging of “republican civility principles” which until then had been a stronghold of national discourse.Footnote5 At the center of these principles were the republican civil ethos by which “the individual’s aspiration for promoting the general will” is compensated through “public estimation and political legitimacy,” and the cultural militarism that nurtured the presence of “military-security representations in high and popular cultures and in public political psychology.” Toward the 1980s the national republican discourse came under fire by the penetration of “liberalism, privatization and post-nationalist discourses.”Footnote6

As a prominent institution of State power,Footnote7 the military was not immune to forces of liberalization.Footnote8 In this cultural climate, a criticism of the military itself began to emerge, as well as one toward cultural national militarism which in the spirit of the era was expected to reduce its presence in public “civil representations.”Footnote9 In this respect, the liberal turning point resulted in growing erosion of the army’s social legitimacy. In an attempt to cope with this De-legitimization and to block it, the ”liberal way of war”Footnote10 or “Liberal Militarism” evolved during this period. The term, coined by Edgerton,Footnote11 embodies the transformation of armies in western democracies in an attempt to readjust to liberalistic trends and reconcile between preservation of military force and its use, and a commitment to liberal values of democracy, human rights, and Humanitarianism.Footnote12 In other words, liberal militarism is an attempt to cope with the paradoxicality of liberal war and the use of military force in order to make “liberal” peace.Footnote13

Military ethics is a central pathway through which liberal militarism had been realized. The Ethics of War attempts to cope with the moral gap between norms of war and those of private and civilian lives.Footnote14 As such, it aims “to equip soldiers and decision makers with conceptual and analytical tools enabling them to make moral and rational decisions,” especially in the “gray areas” created by war.Footnote15 In the military arena, military ethics aimed to define “liberal wars” as morally justifiable, and to delineate a method of combat that corresponds, to the extent possible, with humanistic morality. This was achieved to such an extent, that some claim that the liberal ethical turnFootnote16 led to a tendency for over-moralization of the army and of the conduct of war. In the cultural arena,Footnote17 approaches to ethical discourses enable an artistic discussion on the army’s influence on society. This state of affairs emphasized the part of the artistic arenas as possible agents of military ethics and of cultural negotiation for its phrasing.

Narrative film and television drama as agents of liberal military ethics

Works of art, according to Mautner, can be “a source of moral enrichment […]” - for presenting and illustrating moral dilemmas; as well as a significant pedagogical tool for the “endowment of moral education.”Footnote18 The exposure to works of art, Carroll explains, assists in exercising “moral judgment.” According to him, this is especially true for narrative fiction which mobilizes the audience to a “constant process of ethical judgment” and encourages it to perform “moral evaluations” of characters and situations,Footnote19 which in turn facilitate an imagination of “the state of the other.”Footnote20 Moreover, the enhanced mimetics and iconicity enables narrative film and television dramas not only to narratively and stylistically illustrate moral challenges, but also to suggest a reflexive discussion and audio-visual evaluation of them.Footnote21

Thus, alongside their extensive accessibility, cinema, and television have become an informal but highly influential tool for forming popular perceptions of the “moral (and legal) grammar of war.”Footnote22 Proof of this can be found in the growing recognition of narrative audio-visual media as a significant, powerful tool for ethic initiation, even within military training itself.Footnote23 While the topic of ethical issues pertaining to the military condition is more prominent in documentaries, narrative films and television dramas take a no less central and influential part in it. Finlay explains this in his paper on the Just War Theory and the ways in which they are active participants in its current phrasing.Footnote24

Although deliberations on the question of the Just War go back centuries, it is currently known mainly through the book by Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars (1977).Footnote25 This theory relies on a distinction between combating sides, and by contrasting definitions it proposes a structure for the moral evaluation of wars, through opposition between Just Wars – which can be ethically justified, and wars that are not just; as well as between just and unjust combat (the military strategy and tactic implemented). Thus, in a way that possibly reflects a link between Walzer’s theory and the liberal turn, a central argument in the theory is that as “the end does not justify the means,” there may be cases in which “it is possible to fight a just war by unjust means.”Footnote26 In this context, the theory also distinguishes between Just Warriors – who operate in a just and moral manner, and Unjust Warriors – who act in an unjust manner. The terms of the Just War, as shown by Finlay in his discussion of Just War films dedicated to the “moral drama” of war,Footnote27 are efficient in evaluating the ethical position of cinematic and televised representations of military action.

De-politicization and dis-militarization as strategies for the establishment of “military ethical washing”

A fascinating dialectic characteristic of the liberal era is the appearance of De-Politicization and Dis-militarization processes serving to neutralize liberal militarism. The public sphere is always political in its nature – it is organized and formed through political discourse and “power relations and interests” of the social discourse order.Footnote28 De-Politicization is a process that involves a blurring of the political aspects of a certain social or cultural practice. Through marginalization or detaching of a certain process from the social power structures, De-Politicization creates an impression of noninvolvement in social politics, presenting it as “sporadic, spontaneous or extra-national.” This naturalizing process grants De-Politicization its power as an efficient way to prevent and thwart opposition or nonhegemonic subversion, and a re-ratification of the existing hegemonic order. Where a critical exposure of hegemonic political and ideological conditions is enabled and their dismantlement encouraged, De-Politicization processes divert public attention to other elements, which are not contradictory to them.Footnote29

Although it sometimes appears that De-Politicization processes are limited to totalitarian regimes or republican governments only, they can also be found in liberal democratic arenas. In fact, it is possible that the very conditions of the liberal turning point promote expressions of De-Politicization, especially in military contexts. The erosion in military legitimacy leads in the liberal era to a gradual cultural marginalization of the army and a De-militarization of social discourse.Footnote30 Thus, military De-Politicization disconnects from “particular historical and political circumstances and contexts of war”Footnote31 and creates what will be referred to in this paper as Dis-militarization.Footnote32 In this way such neutralizing and naturalizing processes can assist in the persistence of National State MilitarismFootnote33 and republican cultural militaries, and in the establishment of “Military Ethical Washing” even after appearing to have been a figment of the past,Footnote34 as shall be shown in the Israeli context of internal targeted killings as depicted in narrative film and television dramas.

The ethical-liberal turning point in Israeli society

According to Lebel, civic approach within Israeli society had been organized around republican values and a cultural militarism. Such attributes remained stable until the 1980s, when influences of the liberal turning point began to penetrate, undermining nationalism.Footnote35 The liberal turning point can also be identified in the Israeli case in post-Zionist criticisms that grew in academia, presenting the transition from “a historical consensual awareness” of Zionism in its hegemonic form, to a “historical conflictual awareness” of national past events.Footnote36 Unsurprisingly, the evolving of post-Zionist criticism had entailed a critical attack on the events related to the establishment of Israel.

This formative national period became fertile ground for investigations into the sources of military policy and cultural militarism flaws which in the discourse of the period were defined as immoral and socially corrupting, especially in light of present events: the continuation of the occupation and violent reality of the IDF’s involvement in Lebanon (1982), the first intifada (1987) and the second one (2000). Thus, the war in Lebanon was perceived as unjust and unessentialFootnote37; while the first and second intifadas reinforced the discourse on unjust warfare and presented to Israeli society the construct of the immoral soldier.

In the Israeli military arena, influences of the ethical-liberal turning point can be identified in the timing of the development of the IDF’s ethical code in the beginning of the 1990sFootnote38 and the implementation of ethical education in its training as of the beginning of the 2000s.Footnote39

A central cultural expression of the ethical-liberal turning point’s influence in its military context can be easily found in cinema. The formative model of Israeli cinema, the national-heroic genre, in the spirit of republican self-sacrificing and cultural militarism models, had been recruited for the national causeFootnote40 and did not undermine its moral justification. However, as of the political films of the 1980sFootnote41 and into “the new Israeli cinema” of the 2000s,Footnote42 an influence of the ethical turning point of the liberal discourse on military representations can be identified. This trend can be noted in the cinematic creation itself, in its contents and its style; but also in academic research, which appears to be increasingly interested in questions involving the ethical role of cinema.Footnote43

According to Ben-Zvi Morad, during this period film scholars began examining the cinematic ethic of filmmakers and their commitment to “Truth, morality, and the study of reality,” the ethical implications of stylistic “artistic choices” and the ethics of “viewing and interpreting” films. In a way that may raise allegations of over-moralization also in the cultural arena, Ben-Zvi Morad shows that in the last few decades there has been “an almost obsessive interest of Israeli cinema and its researchers in questions of ethics.”Footnote44 In most films, this trend is expressed in military representations connected to the present or recent past, but some films also return to a more distant one. In this context, the study of the formative years of the struggle for independence in “Underground Films” is of increased importance as it enables, similarly to post-Zionist historiographies, to identify and point to a “shameful origin”Footnote45 of the IDF and Israeli military culture; as the IDF had been structurally, organizationally and personally based on pre-State pre-military movements. Moreover, despite the fact that ethical issues involving the military are not unique to representations of underground internal targeted killings, they may possess an enhanced critical potential; as they can identify an early incarnation of a military practice that became more and more prevalent at the time the films were made, and with the influence of the ethical-liberal turning point also became controversial – i.e., the targeted killings. Under these circumstances the lively ethical discourse regarding their implementation may serve as a central paradigmatic case study for the IDFs coping with liberal militarism terms.Footnote46

Internal targeted killings in the struggle for independence

The struggle of the Jewish Yishuv for national independence was long, stormy, and violent. In the twenty years from the onset of the British mandate in Palestine, the struggle was predominantly political-diplomatic, but in its last decade it also became a pre-military armed struggle. During this period three pre-State underground organizations were active within Jewish society, with an “ideology of direct action” aimed outwards (toward the British and the Arabs), but also inwards (within the Jewish Yishuv itself).Footnote47 Internally, the three underground organizations fought against one another as to the correct ways of struggling for independence and the character of the future State. The Hagana (founded in 1920) and its recruited underground organization the Palmach (1941) formed the security organization of the established Yishuv controlled by the Labor movement.Footnote48 The Etzel (1937) was the combat underground organization of the opposing revisionist movement, while the Lechi (1940) evolved from the Etzel, but later split from it following internal disagreements. Despite their common national goal, throughout their entire period of operation, organizations upheld a bitter rivalry that included extreme acts of violence, of which internal targeted killings may be the most prominent example.

The current paper uses the term internal targeted killings as a general term to describe a range of “political assassination events”Footnote49 which took place in significant numbers, as was shown in Ben-Yehuda’s studies. The extent of internal targeted killings during that period can be understood through its diverse occurrences, which can be classified into four central types: 1) Internal targeted killings between underground organizations – assassinations between the Jewish underground organizations, in which one organization assassinated a member of another. These mostly occurred following suspected collaborations with the British; 2) Internal targeted killings within the organization – due to “internal organizational reasons and needs”Footnote50; 3) Internal targeted killings outside the organizations – assassinations which targeted Jewish citizens which were not part of the underground organizations. Most of these cases involve suspected collaboration with the British and Jews that served in British security forces. In some cases, civilians suspected of collaboration with Arabs were also assassinated; 4) Internal State-Sanctioned Killings – in addition to internal killings that clearly pertain to the underground organizations period, there is also one case of a State-Sanctioned KillingFootnote51: although this case occurred after the establishment of the State of Israel, it can be identified with the “short period of adjustment”Footnote52 or transition to the State period, and with some people’s difficulty to part with underground ways. This case involved the execution of Meir Tobianski which occurred during the War of Independence. Tobianski was a senior member of the Hagana, who during the events served as a senior official in the Jerusalem-based Electric Corporation and as a commander in the recently established IDF. The Intelligence department of the Hagana in Jerusalem, under the command of Binyamin Gibli, suspected that Tobianski had passed on information that led to Arab attacks against Israeli forces fighting in the city. With the support and approval of Isser Be’eri – head of the Israeli intelligence, Tobianski was arrested in Tel Aviv on 30 June 1948 at around three in the afternoon, and about an hour later was court martialed. The field court comprised of three military judges found him guilty of espionage and treason and sentenced him to death. That same evening Tobianski was executed by a firing squad.Footnote53

According to Ben Yehuda, at the time assassinations were morally justified by all underground organizations as part of the essential struggle for national independence. This common goal justified and even necessitated, in the absence of any other recourse, use of various forms of killings of external non-Jewish enemies, and maybe even to a greater extent of internal enemies who are Jewish.Footnote54 Whether defined as operational targeted killings or punitive acts, all underground organizations perceived them as important in “purifying the inner group and redefining its moral boundaries.”Footnote55 However, even during these historic events, the hegemony of the Yishuv used internal targeted killings as stumbling blocks against non-hegemonic underground organizations, serving to further segregate and isolate the Etzel and Lechi and to “incriminate” them in the style of hegemonic policing criminalizationFootnote56 as illegal organizations, through their framing as “terrorists” even though both the Hagana and Palmach used similar methods. Later on, through the decades in which the Yishuv hegemony held onto government,Footnote57 institutional historiography blurred and concealed the role of the Hagana and Palmach in this practice, tying it almost exclusively to the Etzel and Lechi.Footnote58 In the cultural arena, not only were the Etzel and Lechi excluded from cinematic representations, but representations of internal targeted killings were excluded from it entirely.

Representations of internal targeted killings in narrative films and television drama

Internal targeted killings have been represented in “Underground Films” since the 1980s. During this period liberal post-national trends reflected in cinematic representations and for the first time covered all underground organizations, including mentions of their controversial operations, illustrating their attempts to undermine the legitimacy of the army and its origins.

The films that portray internal targeted killings are either based on actual historical events, whether declared as such (Tobianski) or not (Crossfire,Footnote59 Body in the Sand,Footnote60 and EaglesFootnote61), or weave a fictional plot “within the framework of events that took place in the past.”Footnote62

Internal targeted killings are represented in films directly and indirectly, and to varying extents. Winter Games, set in 1946, describes the arrival of a Lechi combatant to a village near Haifa, apparently fleeing from the Brits, and the complex relationships between him and village residents. The Fifth Heaven describes the story of an orphanage for girls in the last year of World War II. Both do not include depictions of internal targeted killings, but do contribute to a portrayal of the climate in which they occurred. The film Rage and Glory reveals the story of a group of Lechi combatants in Jerusalem in 1942, mentioning internal targeted killings as a possibility that is raised in their discussions. Eagles portrays the story of two former Palmach soldiers and current serial killers, mentioning them in a short scene that may anticipate the murderous direction chosen by the protagonists. Conversely, in other films internal targeted killings form a central plot line. Hide and Seek describes the coming of age of a young boy named Uri in 1946 Jerusalem, presents a comparison between the Hagana’s assassination of a Jewish informer and the assault of Uri’s young teacher and his Arab lover. The film’s protagonist and his friends peek at the couple on a number of occasions, after which they suspect that the teacher is an informant and report this to one of the boys older brothers who is in the Palmach. Although it becomes apparent that the teacher is not a “traitor,” he still gets “what he deserves” from members of the hegemonic underground organization. Three Palmach combatants assault the teacher and apparently kill his Arab lover. A direct and central representation of internal targeted killings is also present in Crossfire, a film set in 1947, describing a love story between a young Jewish woman from Tel Aviv named Miriam and a young Arab man from Jaffa named George. The story ends with her assassination by the Lechi. Tobinaski, which retells a historical affair presents a chronology of the only execution of an Israeli soldier in the history of the IDF. Finally, Body in the Sand is completely focused on internal targeted killings in the underground organization and depicts two such killings. The film presents the long-term effects of the killings on people that took part in them. Decades after having assassinated his comrade, the protagonist assassinates another veteran to silence him and prevent the first occurrence from being published. Thus, in different ways, these films establish internal targeted killings as a central phenomenon of the period, as seen from its representation in various spaces and times.

In outdoor open spaces (a citrus grove in Crossfire and the seashore in Body in the Sand), in outdoor urban social spaces (a Jerusalem Café in Hide and Seek and a Tel Aviv Street corner in Eagles), and even in institutionalized outdoor spaces (the military base parade square in Tobianski). Hide and Seek even includes a depiction of an attempted targeted killing within a private home. Sometimes it is done in broad daylight (Hide and Seek, Crossfire, Body in the Sand and Tobianski), and sometimes in the dark of night (Hide and Seek and Eagles).

Contentually, the films offer representations of each of the four types of internal targeted killings that occurred during the relevant period. Internal targeted killings between underground organizations can be found in Eagles in the description of the assault on Etzel men by Palmach combatants in Tel Aviv. Internal targeted killings within the organization are mentioned in Rage and Glory and directly and extensively depicted in Body in the Sand. An Internal targeted killing outside the underground organization appears in Hide and Seek, when Hagana combatants assassinate a waiter who had apparently given information to the Brits in return for money, and also in the end of Crossfire when Miriam is assassinated. An Internal State-Sanctioned Killing is depicted in Tobianski.

Tobianski (fair use).

Some of the films present the results of the assassination on screen. This is true in the case of Hide and Seek, Body in the Sand and Tobianski which all include close-ups of a bloody body or body parts, verifying the injuries and death. Conversely, in Crossfire and Eagles, the results of the assassinations are not presented on screen. Crossfire replaces the direct depiction of the assassination with an insinuating cinematic composition. A shot of the car in which the Lechi men are driving away with Miriam is followed by the citrus grove to which they have taken her, and in the background all that is heard is a single gunshot. Closing text on screen immediately afterward confirm her death. In Eagles, even though the soundtrack includes a voiceover of the protagonist explaining that he and his friends “were not in a Palmach of sweethearts who write songs and steal from the chicken coop… We were tough and we had our tradition, for which we were prepared to kill, and not only Arabs, also Jews if needed …;” the visual composition only shows a long shot of him and his friend punching a man in a dark alleyway.

It is interesting to note that only a few films personally identify the assassins (Body in the Sand, Eagles, and to a certain extent also Tobianski) and the assassinated (Crossfire, Body in the Sand, Tobianski). This can be seen as a distancing or blurring mechanism, one of several mechanisms used to implement De-Politicization and Dis-militarization processes that thwart potential critical discussions on internal targeted killings and enable the evolution of “Military Ethical Washing.”

De-politicization and dis-militarization and the creation of “military ethical washing” in representations of internal targeted killings

The films present the climate in which internal targeted killings had been possible. All of them raise apprehensions from collaboration, either willingly or by force, and from situations perceived as substantial threats to the national mission for the establishment of the State. An expression of this can be found in representations of this fear through all age groups, social groups and various underground organizations. In addition, the incorporation of these representations in films included in the corpus, having an accumulated narrated timeFootnote63 covering the period between 1942 and 1948, establishes fear of collaboration with the enemy as an ongoing condition. In Rage and Glory, this fear is expressed within the lines of the underground organizations themselves. Following the failure of a number of operations, some members suspect that there is a traitor among them. One even points to a person she believes is the traitor – their munitions expert who wishes to retire from the organization. In an emotional conversation before heading out to another operation, through the fear that it too would fail, she suggests holding a “trial of peers.” However, what is insinuated in Rage and Glory is widely depicted in Body in the Sand.

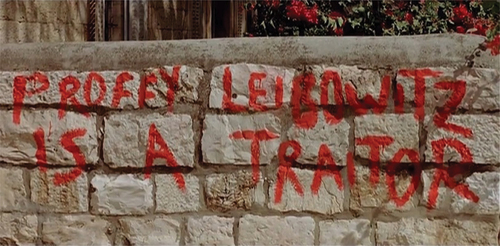

In a confrontation between the four members of the underground organization about the circumstances of the targeted killing of their friend in the past, the question of treason is raised. When one blames another in handing information to the British, he adds and explains that “In this type of treason, the policy of the organization had been clear – elimination!.” In The Fifth Heaven the fear of treason is depicted when the boarding school principal dismisses the young cleaning girl Bertha for her romantic ties with a British officer and his fear that this would hinder his efforts to raise funds for the school. Winter Games depicts the fear among residents of the village in which a Lechi combatant attempts to find refuge, to become involved in the struggle between the British and the underground organizations, and between the organizations themselves. In Hide and Seek the threat of treason is depicted in a long meeting of neighborhood residents. In the scene an older woman who manages the meeting exclaims to the convening neighbors, but also to viewers – that “We are confident that there is a collaborator [with the British] in our neighborhood.” She even promises and threatens, “Don’t worry – he will be punished.” In The Little Traitor, set in Jerusalem in 1947, the charge of treason for “delivering secrets to the British” is made against Proffy – a young boy who develops a friendship with a British officer. The film shows the official investigation held against him despite his young age, and although he is found to be not guilty, he is still banished by his friends who turn their backs on him and write on one of the walls of the neighborhood: “Proffy Leibowitz is a Traitor.”

The Little Traitor (fair use).

The film Crossfire illustrates the fear of treason on the eve of the War of Independence, with the vigorous efforts of the Hagana and Palmach to put an end to the relationship between George and Miriam. To complete the picture, Tobianski illustrates the persistence of the fear of treason even after the British have left and the transition to Statehood had been achieved. Thus, the films included in the corpus establish the struggle against the threat of treason as a justifiable war and justified reason for using weapons. However, at the same time, in a way that marks liberal dialectics, representations of internal targeted killings also create in these films a De-politicization of the described historical arena which disconnects them from the internal struggle between underground organizations and blurs its violent discourse.

Moreover, paradoxically these films mark internal targeted killings as inappropriate, and as unjustifiable warfare. This “ethical tier”Footnote64 is depicted through artistic choices determining not only what will be presented and what will not, but also how, thereby also exposing the Dis-militarization processes of the existing military ethic.

An examination of the film’s narrative composition shows that they condemn the killings through diegetic processes within the film world, and also extra-diegetic process which are external to it. Hide and Seek and Tobianski use characters within the diegesis, that view the killings and explain their condemnation to the viewer. In Hide and Seek, for instance, the protagonist is a bystander tearfully viewing the attack against the teacher and his lover.

Hide and Seek (fair use).

Similarly, in Tobianksi, soldiers are seen, most of them female, watching the execution with shock and dismay. In this film the process is doubled also by the addition of extra-diegetic “reproachful” closing titles stating that none of the people involved in the execution had been truly punished for their actions. A similar reproach through closing titles can also be found in Crossfire, which ends with a black and white photograph of Miriam and George, and above it the text “Although her blame had not been proven, her name was never cleared and those responsible for her death never paid for what they did.”

A stylistic examination of the representation of internal targeted killings in the films raises a number of attributes that create what can be referred to as their “reproaching esthetics:”

Reduced lighting – In most of the films included in the corpus (Hide and Seek, Rage and Glory and Eagles), the representations of internal killings are characterized by low key lighting. Whether the scenes take place indoors or out, during the day or at night, they include an especially dark frame, nearly monochromatic, with limited visibility and contrasting shadows that give a sense of terror and vagueness which in the cinematic style of the film noir can represent ambivalence or moral deviation. Footnote65

Rage and Glory (courtesy of Artumas Communication and United King Films).

Eagles (fair use).

Enhanced sound – The representation of internal targeted killings is characterized by an enhancement of vocal elements emphasizing the representation of the events as intimidating and violent. In Hide and Seek, Body in the Sand and Tobianksi the sounds of the shooting seen on screen are enhanced, while in Crossfire an especially loud shot is heard, replacing in the cinematic composition the representation of the shooting itself, which, as already mentioned is not seen on screen at all. Hide and Seek and Eagles depict an enhancement of blows and throwing of objects, cries of pain and injury. In addition, in all films, representations of internal targeted killings are accompanied by a troubling and threatening “interpretative music” .Footnote66

Cinematic duration – the films depicting internal targeted killings do so through the use of fast or slow motion – “A technique common to all types of moving pictures, that creates a prominent gap between the representation of time and the actual duration of an action.”Footnote67 In Hide and Seek the assassination of the Jewish informer is very swift and appears to be represented in fast-motion, while the assault of the teacher and his lover begins with slow motion. In Body in the Sand slow-motion is used to represent the actual moment of the killing and the falling of the assassinated man, marking his death. In Tobianski, slow motion is used both in the depiction of Tobianski being taken out to the shooting yard and during the shooting itself. In all these cases, the emphasis of cinematic duration creates an enhanced esthetic through which the moment of death is intensified.Footnote68 In Body in the Sand the visual slow motion is emphasized also through a soundtrack distortion of the cries of pain of the attacked.

Enhancement of the color red – a recurring representation in some of the films included in the corpus is the use of a strong shade of red in the depictions of assassinations. The assassination of the informer in Hide and Seek ends with a shot imbued by a gleaming red through which the blood marking the shot to his chest is multiplied by the red tablecloth in the nearby café. In Body in the Sand, a short closeup of red blood is seen seeping from the cloth of the shirt of the victim. In Tobianski, when the body of the protagonist collapses to the ground, a bright red blood stain remains on the death wall behind him. In fact, even in The Little Traitor, which does not include an actual representation of a killing but only marks the social-cultural climate in which internal targeted killings had taken place, an echoing of such representation can be noted in the red paint used to write the malicious graffiti against Proffy.

Positioning – Hide and Seek and Body in the Sand shares direct and even multiplied representation of killings, with a similar composition in which the victim is presented with his back to the camera, and only after he is killed his face is seen. This composition visually establishes the internal killing act as an act of treason – only this time the victims are not those who are suspected of collaborating with the enemy, but the assassins themselves.

These and other stylistic characteristics depicting internal targeted killings may present an expression of the argument that a just war does not justify unjust warfare. However, surprisingly as can be seen from the liberal dialectic that created “Military Ethical Washing,” it is not the military ethic that frames internal target killings as unjust and immoral. Contrary to expectations, the “moral gap” established in the films between the justification of war and denunciation of the killings, does not serve to define the acts themselves (the warfare) or its perpetrators (the warriors) as unjust in a way that could have served to define a moral position vis a vis the military practice. A close examination shows that De-politicization and Dis-Militarization processes are seen as opposing voices, thwarting their potential criticism toward the army and cultural militarism. Thus, the films exchange ethics pertaining to the military condition with a civil liberal ethic that is tied to the private sphere of individual rights and liberties. Despite the fact that arguments for De-Politicization of the military situation as a way of evading moral responsibility are expressed in various works dealing with Israeli cinema and television,Footnote69 it appears that representations of internal targeted killings provide a case study for the way in which films justify a specific current military practice and an ethic which is under dispute, thereby leading to “Military Ethical Washing.” The main strategy by which this is achieved in the films is Dis-militarization – a distancing of ethical questions entailed in acts of internal targeted killings from the army and its underground historical origins.

As already mentioned, Winter Games and The Fifth Heaven do not include a representation of an internal killing, but do mark the migration of ethical discourse from military to civil. Both identify underground combatants, which in the other films are depicted as fully responsible for the killings, with moral deviation through the recurring representation of a taboo relationship between a combatant and an underage girl. The hostility among villagers toward the Lechi combatant in Winter Games, which eventually leads to his death, is explained in the film through a combination of the fact of his belonging to the terrorist underground organization, and his sexual relations with one of the village girls. Similarly, The Fifth Heaven outlines the forbidden relationship between Duce, the Lechi combatant hiding at the girls orphanage, and Maya, the film’s 13 years old protagonist. Various scenes throughout the film depict the insinuated relationship developed between them, which begins with an underground secret of hiding weapons, which Duce shares with Maya, and continues with initial groping and touching which are clearly forbidden. In their last meeting, just before he heads out to action, Maya asks him to take her with him. The two hug lengthily and Duce tells her that he cannot, because “it’s forbidden, it would be no good.” From his words it is not clear whether he means the imminent action of the underground organization or their relationship that deviates from social norms.

The Fifth Heaven (fair use).

The films that include a representation of internal killings directly and explicitly establish this exchanging of military ethics by a civil one. As mentioned, Hide and Seek includes two consecutive scenes consisting of the assassination of an informant and the attack of the teacher and his Arab lover, which apparently leads to his death. The film’s cinematic composition ratifies and normalizes the first killing as successful and fitting, while the other attack is denounced. In terms of screen time and the viewer’s empathy-creating familiarity with the victims, emphasis made in the film on the attack of the teacher and his lover raises the argument that the film does not oppose internal killings per se as an inappropriate military practice, or sees them as a possible source of ethical deviations in the IDF today. In fact, the film’s composition insinuates that it actually aims to oppose conservative society’s unacceptance of the homosexual and interracial love between a Jewish and Arab man, presenting a deviation from hetero-normative and ethno-normativeFootnote70 limits as defined by the nationalist discourse that aims to maintain “the family as a productive unit”Footnote71 and to preserve the ethnic and nationalist separation that defines it. A similar case that also denounces the conservative fear of the national order from “mixing blood,” and not of the use or instilling of targeted killings as an immoral military practice, can of course be found in Crossfire. Various scenes in the film depict the Hagana’s attempts to thwart the relationship between Miriam and George, confirming the argument that the film is protesting against a racial conservatism that views “forbidden love”Footnote72 as “national degradation”Footnote73; rather than against the military practice of targeted killings. Here too the arrows are targeted toward conservativism and oppression of the national order as being hetero-patriarchic and Europocentric,Footnote74 while never demanding it to assume responsibility for the implementation of military force.

The Drama Body in the Sand does not make do with the needs of the underground organization to justify the internal killing, but also ties it to an act of treason having a background of romantic love as well as personal benefit and vendetta. Thus, for instance, the past killing was tied to a love triangle involving a woman combatant and two men from the underground organization, and it is insinuated that one of the men emotionally abused the woman. “He belittled her, humiliated her and crushed her,” describes one of the protagonists, to explain why he wanted him dead. However, while he speaks the cinematic composition provides a visual flash-back to the past, proving his version to be false, in view of the relaxed love scene depicted on screen. This representation, at the very least links the internal killing with a moral deviation that is related to loyalty and trust, if not insinuating to the existence of violence within this framework. In the mini-series Eagles the internal killing is identified with a deviation of familial patriarchic norms when the two protagonists, Palmach warriors, uphold an alternative common familial and conjugal relationship with the same woman, who gives birth to a daughter whose father may be either of them. Even Tobianski, which directly denounces the arbitrariness of implementing military power and the fact that position holders in the military establishment do not take responsibility for their actions, does not make do with these arguments which clearly pertain to the military ethic, but enhances them with the portrayal of Gibli, whom it identifies as the main party responsible for the execution, and as a chauvinist who uses sexual aggression toward his secretary. This depiction of Gibli, which takes up much of the film, paints the moral failure of his functioning in the Tobianski affair with violent and oppressive masculine norms which do not directly stem from the military situation.

Using these methods, the cinematic and televised composition distances representations of internal killings from the military sphere, emptying them from the critical potential of military ethic, and exchanges them for a call only for a civil liberal-universal morality.Footnote75 In a final analysis it appears that any possible discussion of war, warfare or immoral warriors was largely severed from the most recent representations of internal target killings in Israeli cinema and television.

Conclusions

This paper presented the term “Military Ethical Washing” to describe the ways in which the ethical-liberal turning point creates a demand for liberal militarism on one hand, but undermines it through the De-Politicization and Dis-Militarization of military ethics on the other. Thus, contrary to previous studies that referred to the way in which the general civic ethic discourse serves to morally “clean“ the army, this paper emphasizes the role of the military ethic itself in screening its moral responsibility.

As shown, in terms of the ethical-liberal turning point narrative films and television dramas not only serve as new post-national historiography agents,Footnote76 but also as agents of military ethic. Under such conditions it is no wonder that film and television are returning to the formative period of the establishment of nationalism, in which the historical sources of the military are of crucial importance. This is why many inquiries held in Israeli press, television and documentary films tend to examine “each and every sign of unfitting behavior” by the IDF in general, and in the days of the underground movements and Israel’s War of Independence – the IDF’s origins, in particular.Footnote77 However, as can be seen from representations of internal targeted killings in underground films through the prism of the “Just War Theory, narrative film and television dramas tend to conceal representations that may raise moral disagreement and distance them from the army. The advantage of the dramatic depiction of the internal killings, which is lacking from written or filmed documentary representations and may have illustrated the moral drama that is derived from the military situation, shifts the ethical discussion away from the army, thereby enabling it in audio-visual fiction to be “washed“ as “the most moral army in the world.” In this way cinematic and televised representations, which had originally reflected and maybe even anticipated the liberal attempt to challenge the army and to demand a moral liberal militarism, have become a means of “Military Ethic Washing” – toward the establishment of a conservative national military ethic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The term “Military Ethical Washing” is based on current uses of the image of “washing” for cases in which a liberal impression qualifies actions which the liberal discourse allegedly denounces, or the way in which the liberal discourse “covers over or distracts” its ailments [Amar Wahab, “Affective Mobilizations: Pinkwashing and Racialized Homophobia in Out There,” Journal of Homosexuality 68, no. 5 (2021): 850].

2. Films belonging to the corpus of “Underground Films” as of the beginning of Israeli cinema until the 1980s are: Ceasefire (Amram Amar, 1950), The Faithful City (Józef Lejtes, 1952), Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer (Thorold Dickinson, 1955), Pillar of Fire (Larry Frisch, 1959), What a Gang (Ze’ev Chavatzelet, 1973), He Walked Through the Fields (Yosef Millo, 1967), and The House on Chelouche Street (Moshe Mizrahi, 1973).

3. Ella Shohat, The Israeli Cinema – East/West and the Politics of Representation (Raanana: Open University Press, 2005), 22-24 [Hebrew].

4. Sarah Cardwell, “Television Aesthetics: Stylistic Analysis and Beyond,” in Television Aesthetics and Style, eds. Jason Jacobs and Steven Peacok (London, New Delhi, New York and Sidney: Bloomsbury, 2013): 23.

5. Udi Lebel, “The Limits of Victimization and the formation of the Hierarchy of Bereavement: Terror casualties and the decline and revival of the Republican Bereavement Discourse,” Democratic Culture 14 (2012): 161 [Hebrew].

6. Lebel, 2012: 157-160.

7. Bryan Mabee and Sardjan Vucetic, “Varieties of Militarism: Towards a Typology,” Security dialogue 49, no. 1-2 (2018):97.

8. Jean Joana and Frederic Merand, “The Varieties of Liberal Militarism: A Typology,” French Politics 12, no. 2 (2014): 184.

9. Lebel, 2012: 164.

10. Anna Stavrianakis, “Legitimizing Liberal Militarism: Politics, Law and War in the Arms Trade Treaty,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 5 (2016): 845.

11. David Edgerton, “Liberal Militarism and the British State,” NLRI 185 (1991): 1.

12. Victoria M. Basham, “Liberal Militarism as Insecurity, Desire and Ambivalence: Gender, Race and the Everyday Geopolitics of War,” Security Dialogue 49, no. 1-2 (2018): 33.

13. Bryan Mabee, “From “Liberal War” to “Liberal Militarism: United States Security Policy as the Promotion of Military Modernity,” Critical Military Studies 2, no. 3 (2016): 244-245.

14. Jonathan Parry, “Legitimate Authority and the Ethics of War: A Map of the Terrain,” Ethics & International Affairs 31, no. 2 (2017): 171-172.

15. Benjamin Ish-Shalom, “Purity of Arms” and Purity of Ethical Judgment,” Sefer Amadot: The Yarmulke and the Beret (Elkana Rehovot: Orot College Press, Israel, 2009), 14.

16. Stavrianakis, 2016: 844.

17. Mabee, 2016: 244.

18. Menachem, Mautner, “Natan Alterman, Menachem Finkelstein and the use of Art for the Moral Education of the Army,,” in the Book of Menachem Finkelstein, Eds., Sharon Afek, Ofer Grosskopf, Shachar Lipschitz and Elad Spiegelman (Zafririm: Nevo, 2020), 588-590.

19. Noel Caroll, “Art and Ethical Criticism: An Overview of Recent directions of Research,” Ethics 110 (2000): 366-367.

20. Mautner, 2020: 590.

21. Christopher J. Finlay, “Bastards, Brothers, and Unjust Warriors: Enmity and Ethics in Just War Cinema,” Review of International Studies 43, no. 1 (2016): 788-79.

22. Finlay, 2016: 74-75.

23. Angela M. Riotto, “Teaching the Army – Virtual Learning Tools to Train and Educate Twenty-First-Century Soldiers,” Military Review (2021), 90-94.

24. Finlay, 2016: 75.

25. Raphael Cohen-Almagor, “Michael Walzer’s Just War Theory and the 1982 Israel War in Lebanon: Theory and Application,” Israel Studies 27, no. 3 (2022): 166-167.

26. Cohen-Almagor, 2022: 169-170.

27. Finlay, 2016: 75-76.

28. Gal Hermoni and Udi Lebel, “Politicizing memory – An Ethnographical Study of remembrance ceremony,” Cultural Studies 24, no. 26 (2012): 470-471.

29. Hermoni and Lebel, 2012:471-472.

30. Udi Lebel and Guy Hatuka, “De-Militarization as Political Self-Marginalization: Israel Labor Party and the MISEs (Members of Israeli Security Elite) 1977-2015,” Israel Affairs 22, no. 3-4 (2016): 656-658.

31. Hermoni and Lebel, 2012: 470.

32. The term Dis-militarization involves the expropriation of a military dimension or aspects from a certain social or cultural representation of the army, and not De-militarization which means a change in army-society relations or the civilization of military actions, such as the extraction of military practices from the army’s responsibility, into civilian hands. For an extensive discussion on De-militarization processes see: Arita Holmberg, “Ä Demilitarization Process Under Challenge? The Example of Sweden,” Defence Studies 15, no. 3 (2015) − 2235-253.

33. Mabee and Vucetic, 2018:101.

34. Hermoni and Lebel, 2012: 471-472.

35. Lebel, 2012: 153.

36. Uri Ram, “Zionist and Post-Zionist Historical Consciousness in Israel: A Sociological Analysis of the Historians” Debate.” In Zionist Historiography Between Vision and Revision, ed. Yechiam Weitz. Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 1997, pg. 283. [Hebrew].

37. Cohen-Almagor, 2022: 166.

38. Asa Kasher, “The Spirit of the IDF and the love of the land,” Maarachot 382 (2002): 72-73.

39. Amira Raviv, “Approaches to the Study of Military Ethics in Colleges,” Maarachot 396 (2004): 53. [Hebrew].

40. Shohat, 2005: 68.

41. Yael Monk, Israeli Cinema at the Turn of the Millenium, Raanana, The Open University, 2012: 37. [Hebrew].

42. Monk, 2013: 13.

43. Sandra Meiri, “Lesibat Hadavar Zanav Chavar: Memory, Trauma and Ethics and the narrative films of Judd Ne’eman,” Israel: A Journal for the Study of Zionism and the State of Israel – History, Culture, Society 14 (2008): 35 [Hebrew].

44. Yael Ben-Zvi Morad, “An Aesthetic of Guilt – A Critique on Volume 13 of the Journal ‘Mihkan’ on Ethics and Responsibility in Israeli Cinema;” Slil – Online Journal of History, Cinema and Television 9 (2015): 89-92.

45. Judd Neeman, “Camera Obscura of the Fallen: Military Pedagogy and its Accessories in Israeli Cinema,” in Udi Lebel, ed., Security and Communications: A Dynamic of Relations (Beersheva: Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 2005), p. 347-349 (Hebrew).

46. For an ethical discussion on the implementation of targeted killings see for instanceSteven G. Koven and Abby Perez, “Ethics of Killing and Assassinations,” Public Integrity (2021).

47. Nachman Ben-Yehuda, “Political Assassination Events as a Cross-Cultural Form of Alternative Justice,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 38, no. 1-2 (1997): 32.

48. Udi Lebel, “Exile from National Identity: Memory Exclusion as Politics,” National Identities 11, no. 3 (2009): 244.

49. Ben-Yehuda, 1997:25.

50. Nachman Ben-Yehuda, Political Assassinations by Jews: A Rhetorical Device of Justice (Albany: Stat University of New York Press, 1993), 145.

51. Michael Davis, “Between Peace and War: The Moral Justification of State-Sanctioned Killing of Another State’s Civilian Officials,” International Criminal Law Review 14 (2014): 795.

52. Ben-Yehuda, 1997:37.

53. Ben-Yehuda, 1993: 263.

54. Ben-Yehuda, 1997:34-36.

55. Ben-Yehuda, 1997: 31.

56. Martiza Felices-Luna, “Rethinking Criminology(ies) through the Inclusion of Political Violence and Armed Conflict as Legitimate Object of Inquiry,” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 52, no.3 (2010): 251.

57. Lebel, 2009: 244.

58. Ofer Aderet, “A defeat in the Hagana’s battle for its reputation,” Haaretz 12 June 2020: 15.

59. According to the opening credits of Crossfire, the film was inspired by real events. Although not overtly declared, the narrative resembles Lehi’s assassination of Chaya Zeidenberg at Tel Aviv in the beginning of 1948 (Ben Yehuda, 1997: 254).

60. Body in the Sand does not directly identify the underground organization in question. However, it seems that there is no mistaking the identity of the Lehi. Beyond the narrative similarities to the internal assassination of Eliyahu Giladi in which senior Lehi members were involved (Ben-Yehuda, 1993: 178-185), the characters attributes and the names of the protagonists in the film directly insinuate this comparison.

61. Although this was not expressly stated in Eagles, the order for the cross-organization attack by the protagonists alludes to a real event in which Etzel people were attacked by the Palmach around September–October 1947. Yehuda Lapidot, “The Sezon” – the Hunting Season (Jabotinsky Institute, 2015), 390.

62. Mordechai Bar-On, Smoking Borders: Studies in the Early History of the State of Israel, 1948-1967 (Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, 2001), 38.

63. Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative Volume 2. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 77-81.

64. Ben-Zvi Morad, 2015: 89.

65. Barry Langford, Film Genre – Hollywood and Beyond (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 213-215.

66. Shohat, 2005: 38.

67. Dan Arav, “Trauma in Slow Motion: Historical Reconstruction on Television.” In Film and Memory – Dangerous Relations? Eds: Haim Bereshit, Shlomo Zand and Moshe Zimmerman (Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 2004), 223.

68. Arav, 2005: 224.

69. Orli Lubin, Woman Reading Woman (Hiafa: Haifa University Press, 2003), 234 [Hebrew]; Ben-Zvi Morad, 2015: 9.

70. Yosefa Loshitzky, Identity Politics on the Israeli Screen (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), 113.

71. Raz Yosef, “Resisting Genealogy. Diasporic Grief and Heterosexual Melancholia in the Israeli Films. Three Mothers and Late Marriage.” In Traces of Days to Come: Trauma and Ethics in Contemporary Israeli Cinema (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2017), 188.

72. Loshitzky, 2001: 113.

73. Claire Gorrara, “Fashion and the Femmes Tondues: Lee Miller, Vogue and Representing Liberation France,” French Cultural Studies 29, no. 4 (2018): 332.

74. Yossef, 2017: 185-187.

75. Lubin, 2003: 234-236.

76. Anita Shapira, “History and Memory: The Case of Latroon, 1948,” Alpaim 10 (1994): 25-26.

77. Kalman Libeskind, “A Happy Nakba,” Maariv Weekend, 5 August 2002, 14.