ABSTRACT

Background

ava® is a new reusable electromechanical auto-injector (e-Device) with disposable, single-use certolizumab pegol (CZP) dispensing cartridges.

Methods

RA0098 (NCT03357471) was a US, multicenter, open-label, phase 3 study designed to assess whether the e-Device can be used safely and effectively by self-injecting patients. CZP pre-filled syringe (PFS) self-injecting patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease received training and self-injected CZP using the e-Device at 2 visits. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients able to self-inject safely and effectively at Visit 2, defined as: 1) complete dose delivery, and 2) no adverse events related to the e-Device precluding its continued use.

Results

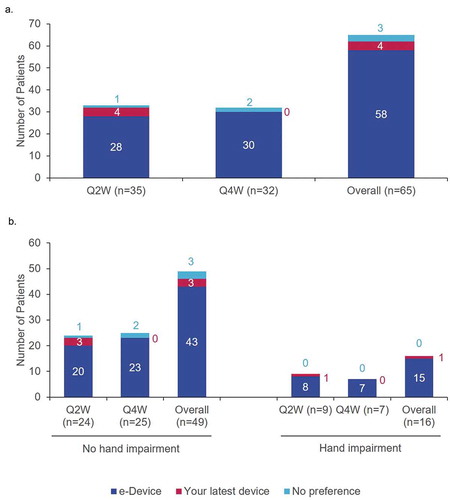

65/67 patients (97.0%) completed the study, 64/65 (98.5%) performed safe and effective self-injection at Visit 2, and 67/67 (100%) performed safe and effective self-injection at Visit 1. Patient satisfaction and self-confidence increased over the two visits. Overall, patients reported a preference for the e-Device (58/65; 89.2%) compared to a PFS (4/65; 6.2%).

Conclusions

Patients were able to safely and effectively self-inject CZP using the e-Device and most preferred ava® over a PFS. No safety-related findings impacting the benefit-risk ratio of CZP were identified.

1. Introduction

Anti-tumor necrosis factors (TNFs) are established and effective treatments for moderate to severe chronic inflammatory diseases [Citation1]. The use of anti-TNFs alongside conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) can result in better long-term disease control and reduced functional impairment [Citation1]. The course of chronic inflammatory disease is associated with an increasing symptomatic burden that leads to a growing number of unmet needs (e.g., limited dexterity) and so requires an integrated patient-centered treatment approach that addresses those unmet needs [Citation2]. The majority of anti-TNFs are administered subcutaneously by self-injection [Citation3,Citation4]. Self-injection can be beneficial to both patients and caregivers, increasing flexibility and patient independence, reducing caregiver burden and reducing costs for both the patient and the healthcare system [Citation5–Citation8]. There are a number of barriers to patients successfully and safely self-injecting anti-TNFs [Citation2,Citation5,Citation6,Citation9]; these include patients’ needle phobia, lack of confidence in their ability to self-inject and forgetting to administer medicine [Citation10,Citation11]. These factors can contribute to sub-optimal levels of adherence to anti-TNF drug regimens, which has the potential to negatively impact patient outcomes [Citation12,Citation13].

Certolizumab pegol (CZP) is an Fc-free, PEGylated anti-TNF approved for use in 66 countries [Citation14]. CZP is approved to treat adults with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA, including ankylosing spondylitis [AS] and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [nr-axSpA] with objective signs of inflammation), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), plaque psoriasis (PSO), and Crohn’s disease (CD); approved indications differ by country [Citation15,Citation16]. At CZP treatment initiation, patients receive a loading dose of 400 mg CZP once every two weeks (Q2 W) for the first four weeks (i.e. the first three CZP doses). This is administered by two subcutaneous self-injections of 200 mg CZP. Subsequently, a maintenance dose of 200 mg Q2 W, 400 mg Q2 W or 400 mg every four weeks (Q4 W) is administered [Citation15,Citation16].

The ava® device is a reusable, electromechanical self-injection device (e-Device) for CZP administration of the 400 mg Q2 W loading dose and 200 mg Q2 W or 400 mg Q4 W maintenance dose regimens, and was developed in conjunction with OXO (New York, NY, USA) [Citation5]. The e-Device supports a single dose of 200 mg per injection; 400 mg is given as two successive 200 mg injections. ava® was developed iteratively with the input of patients with the aim of creating a medical device that improves patient experience; the e-Device incorporates enhanced features designed to address some of the challenges of self-injection [Citation5]. Enhanced features allow patients to personalize their self-injection in order to help overcome self-injection challenges such as dexterity problems, uncertainty during self-injection, and forgetfulness [Citation5,Citation17]. Such features include four different injection speeds (8, 11, 14 and 17 seconds), start/pause/emergency stop functions and notification for the next injection. The e-Device also includes an injection log which may facilitate a dialogue about treatment adherence between patient and healthcare professional (HCP). ava® has been approved for use in the EU [Citation15].

The aim of this clinical study was to determine whether the e-Device can be used safely and effectively for self-injection by patients after being trained on proper self-injection technique. This study was completed following a request from the FDA.

1. Methods

1.1. Study objectives

The primary objective of this study was to determine the proportion of patients able to safely and effectively self-inject certolizumab pegol (CZP) Q2 W or Q4 W using the e-Device at Visit 2. Patients’ ability to do so was evaluated by the HCP present, who documented any AEs that precluded continued use of the e-Device and confirmed complete dose delivery when the CZP-cassette containers were empty upon visual inspection. The secondary objective was to assess the ability of patients to safely and effectively self-inject CZP using the e-Device at Visit 1. Further objectives were to determine patient experience of self-injecting using the e-Device, measure injection site pain, to ascertain patient preference for the e-Device compared to their previous device (CZP PFS), and to evaluate the safety of CZP self-injection using the e-Device.

1.2. Patients

Adult patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with moderate to severe RA, PsA, AS or CD at least six months prior to Visit 1 were recruited. Patients must have been self-injecting CZP using a PFS Q2 W or Q4 W for at least three months before Visit 1. The study aimed to recruit at least 10 patients with impaired hand function (measured as ≥13.5 on the Cochin scale) [Citation18,Citation19]. Patients were excluded from the study if they had participated in another study of an investigational medical product or device within the previous three months or were currently participating in another study.

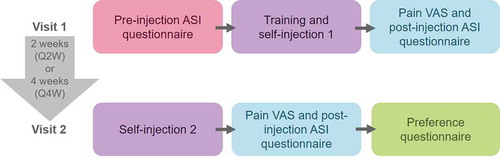

1.3. Study design

The study was a phase 3, open-label study comprising of two site visits and a follow-up telephone call (). Visit 1, was scheduled to coincide with the established CZP treatment schedule for each patient. At this first visit, patients completed an initial eligibility check and baseline characteristics were recorded before carrying out a pre-injection Assessment of Self-injection (ASI) questionnaire. Patients were trained on how to use the e-Device. During the training session, patients could select their preferred injection speed; the default injection speed was ‘fast’ (11 seconds), though patients were able to select their preference (‘fastest’ [8 seconds], ‘slow’ [14 seconds] or ‘slowest’ [17 seconds]). Patients then immediately used the e-Device to self-inject their prescribed dose of CZP. For patients in the Q2 W group this comprised one injection using one a 1 ml, 200 mg CZP cartridge at each visit. For patients in the Q4 W group, this was two injections using two 1 ml, 200 mg CZP cartridges at each visit.

During self-injection at Visit 1 or 2, if the e-Device skin sensor lost contact with the skin, the e-Device withdrew the needle and stopped CZP administration. If less than five minutes had elapsed, the patient could reposition the e-Device and resume the injection. If the patient was unable to administer the entire dose of CZP within this timeframe, an incomplete self-injection and the reason for this was recorded by the HCP in an electronic Case Report Form, in addition to the automatic incomplete self-injection recording in the device’s injection log. Patients used a visual analogue scale (VAS) to indicate the level of pain they felt during their first self-injection using the e-Device and then completed the post-injection ASI questionnaire.

Visit 2 was scheduled to coincide with patients’ next required dose of CZP. For patients in the Q2 W group, this was two weeks after Visit 1; for patients in the Q4 W group there was a four-week gap between the visits. At Visit 2, patients self-injected their prescribed dose of CZP using the e-Device, before assessing their self-injection experience using the pain VAS and post-injection ASI questionnaire. Finally, patients completed a preference questionnaire detailing which device (the e-Device or the CZP PFS) they preferred. For all patients, a follow-up safety telephone call was conducted one week after the final study drug administration. All adverse events (AEs) and adverse device effects (ADEs) were recorded.

1.4. Study procedures and evaluations

Prior to the start of the study all patients signed an Informed Consent form approved by an International Review Board (IRB)/Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) and which complies with regulatory requirements.

1.4.1. Pre- and post-injection ASI questionnaires

Patient experience of self-injection, both before and after using the e-Device, was evaluated using ASI questionnaires. These questionnaires are versions of the Self-Injection Assessment Questionnaire (SIAQ) modified for use with an e-Device [Citation10]. The pre-injection ASI comprised six questions, grouped into two domains: ‘(negative) feelings about self-injection’ and ‘self-confidence’. Questions assessed patients’ feelings toward needles and injections and whether they feel they can safely, cleanly and correctly self-inject CZP. The post-injection ASI questionnaire included 44 questions that evaluated patients’ experience of using the e-Device. Questions were grouped into six domains. Domains included ‘pain and skin reactions’, ‘(negative) feelings’, ‘self-image’, ‘satisfaction’, ‘self-confidence’ and ‘ease of use’. Mean domain scores were calculated for both pre- and post-injection ASI questionnaires.

1.4.2. Injection site pain VAS

A VAS was used to assess overall injection site pain within 15 minutes of completing the self-injections at each visit. Patients were required to indicate their injection pain by placing a mark on a 100 mm line from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst possible pain). The VAS was completed immediately after self-injection and prior to the post-injection ASI. Patients in the Q4 W group completed the VAS after the second injection at each of the visits and were asked to rate their overall pain associated with both self-injections.

1.4.3. Preference questionnaire

After self-injection at Visit 2, patients completed a preference questionnaire to assess their preference between the e-Device and the PFS [Citation10,Citation20]. The questionnaire included nine questions asking patients which device they preferred for specific attributes (e.g. ease of use) or situations (e.g. when traveling). The final question asked patients to indicate their preferred device overall. This questionnaire was completed after the VAS and post-injection ASI at Visit 2.

1.5. Safety recording

Any AEs or ADEs that occurred during the clinic visits were recorded at the time. AEs were defined as any adverse medical occurrence in a patient administered a pharmaceutical product that has a temporal, but not necessarily causal, relationship with the treatment. An ADE is any adverse medical occurrence, unintended disease, injury or untoward clinical sign in patients enrolled in the study. A serious AE/ADE was defined as one that is life-threatening, causes death, significant or persistent disability, congenital anomaly or birth defect or hospitalization, or requires medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the above outcomes. Effects that were considered usual by the HCP or patient (e.g. minor pain, bleeding or bruising) during self-injection were not classified as AEs. A week after Visit 2 each patient received a safety follow-up call during which any further AEs or ADEs were recorded.

1.6. Statistical analysis

Pre- and post-injection ASI questions were rated on a scale of 0–4 or 0–5. To allow comparison between questions, domains and the two questionnaires, scores were converted to a 10-point scale (Supplementary Table S1). ASI domain scores were only calculated if at least half of the questions in the domain had been answered and were calculated as a mean of the item scored included in that domain. The mean and standard deviation of the VAS scores were calculated to analyze the level of pain patients experienced when using the e-Device to self-inject CZP. Overall patient preference scores were stratified by injection dosing group (Q2 W vs. Q4 W) and by Cochin impaired hand function score.

2. Results

2.1. Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 67 patients were enrolled, of these 65 completed both visits of the study. After Visit 1, one patient was lost to follow-up and one patient discontinued using the e-Device due to an AE but continued receiving CZP. Patient baseline characteristics are shown in . The mean age of patients included in the study was 52.4 years (standard deviation [SD]: 13.2 years. Overall, 68.7% (46/67) patients were female and had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 29.6 kg/m2 (SD: 6.9 kg/m2). Of the 67 patients enrolled, 16 (23.9%) had a Cochin impaired hand function score of ≥13.5, exceeding the aim of at least 10 patients in this subgroup.

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics.

2.2. Safe and effective self-injection

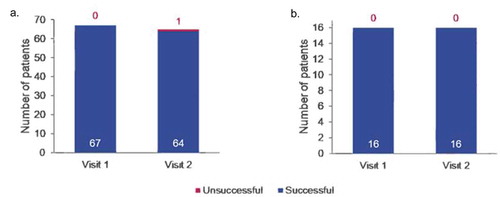

At Visit 2, 64/65 (98.5%) patients were able to safely and effectively self-inject using the e-Device (). One patient did not successfully meet the primary endpoint of a safe and effective self-injection at Visit 2 due to an injection site hemorrhage. At Visit 1, 100% (67/67) patients, including all patients with impaired hand function, were able to safely and effectively self-inject using the e-Device. Of those patients with impaired hand function, all (16/16; 100%) were able to successfully self-inject at both visits ().

2.3. Pre-injection ASI questionnaire results

The results of the pre-injection ASI comprising six questions across two domains are shown in . The overall mean converted scores for the ‘(negative) feelings about self-injection’ and ‘self-confidence’ domains were 2.2/10 (SD: 2.2) and 6.1/10 (SD: 3.4), respectively. The results of the Q2 W and Q4 W subgroups were similar ().

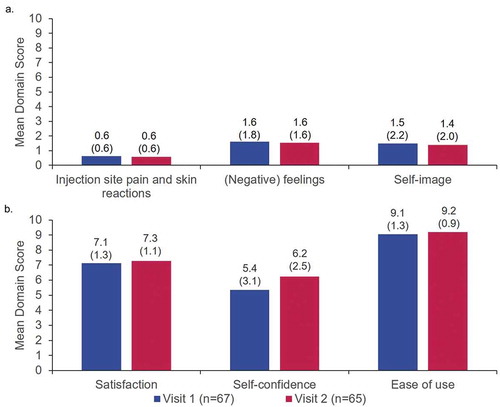

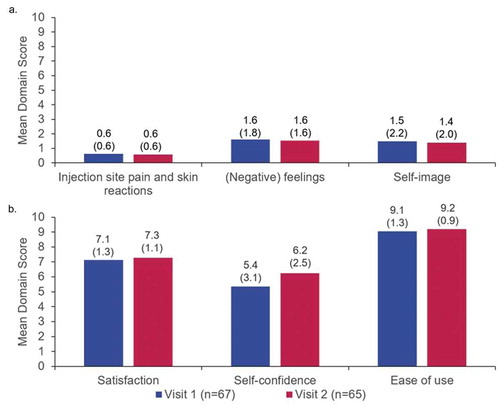

2.4. Post-injection ASI questionnaire results

The results of the post-injection ASI comprising 44 questions across six domains are shown in . These were grouped as negative domains (), ‘pain and skin reactions’, ‘[negative] feelings’ and ‘self-image’; or positive domains (), ‘satisfaction’, ‘self-confidence’ and ‘ease of use’. Post-injection ASI scores for ‘self-confidence’ improved from Visit 1 (5.4/10 [SD: 3.1]) to Visit 2 (6.2/10 [SD: 2.5]) and scores for ‘satisfaction’ improved slightly from Visit 1 (7.1/10 [SD: 1.3]) to Visit 2 (7.3/10 [SD: 1.1]). All other domain scores were similar across visits. Compared to pre-injection ASI domain scores at Visit 1 (), patients reported improved ‘(negative) feelings about self-injection’ and similar levels of ‘self-confidence’ at Visit 2, with post-injection ASI scores of 1.6/10 (SD: 1.6) and 6.2/10 (SD: 2.5), respectively. Pre- and post-injection ASI results were similar between different dosing subgroups (Q2 W vs. Q4 W) (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

2.5. Injection site pain VAS scores

Mean VAS scores were similar between visits (the mean Visit 1 score was 10.9/100 [SD: 15.4]; the mean Visit 2 score was 10.5/100 [SD: 13.0]). However, there was a wide variation in patients’ ratings with Visit 1 scores ranging from 0–82/100 and Visit 2 from 0–64/100. VAS scores were similar between Q2 W and Q4 W; mean Q2 W score at Visit 1 was 10.2/100 (SD: 17.0) and mean Q4 W Visit 1 score was 11.6/100 (SD: 13.6). At Visit 2, Q2 W and Q4 W subgroup mean scores were 12.9/100 (SD: 15.3) and 8.0/100 (SD: 9.7), respectively.

2.6. Patient preference questionnaire results

Most patients (89.2%; 58/65) preferred the e-Device over their current device (). Subgroup analyses of patient preference by hand impairment demonstrated that, when rating the devices for overall preference, patients with hand impairment were more likely to prefer the e-Device than patients without hand impairment (93.8% [15/16] vs. 87.8% [43/59]; ).

2.7. Safety results

An overview of the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) can be found in Supplementary Table S2. Across the study, nine patients (13.4%) experienced a TEAEs, all TEAEs were rated as mild. There were no serious TEAEs or TEAEs that let to permanent withdrawal of CZP. Most commonly patients experienced TEAEs at the injection site (‘general disorders and administration site conditions’: 3 patients [4.5%]) or had TEAEs that fell under the system organ class term ‘infections and infestations’ (3 patients [4.5%]). One TEAE was also classified as an ADE: an injection site hemorrhage at Visit 2 that was recorded as an unsuccessful self-injection.

3. Discussion

Patients, including those with impaired hand function, were able to safely and effectively self-inject CZP using the e-Device after training. Most patients successfully self-injected CZP at both visits, indicating that the e-Device can be safely and effectively used once time had passed between training and self-injection. After using the e-Device, patients rated it highly for satisfaction, self-confidence and ease of use at both visits. These results are comparable to a previously published report using the ASI to assess this e-Device [Citation20]. Patients felt they experienced fewer negative feelings about self-injection when injecting with the e-Device at Visit 2, compared to their pre-injection ASI questionnaire scores. Most patients, including all those with hand impairments, preferred the e-Device over their previous device.

3.1. The e-Device may address some self-injection challenges

These results suggest that using the e-Device may help address some of the challenges associated with self-injection and increase patient satisfaction [Citation6]. For example, rheumatology patients often have dexterity problems making self-injection difficult, which has previously resulted in lower preference scores for auto-injection devices [Citation21]; evidence has shown that ergonomically designed self-injection devices can help overcome this challenge [Citation22]. For example, the e-Device was designed with a larger grip and a large, easy-to-press start button [Citation5]. Although the sample size was small and so should be interpreted with caution, these design features may explain why patients with hand function impairments were more likely to prefer the e-Device over their previous device.

Patients’ lack of confidence in their ability to successfully self-inject can lead to difficulties in administering treatment [Citation17]. In this study, self-confidence improved from Visit 1 to Visit 2 and scores at Visit 2 were higher than those reported during the pre-ASI. This suggests that once patients have used the device to administer an injection, functions such as the on-screen instructions that guide the patient through their self-injection may help to improve self-confidence [Citation5]. Evidence suggests that patients are more likely to feel satisfied with self-injecting biologics if they feel that they are in control of the administration process [Citation6]. This can lead to patients developing habits and rituals help them feel in control [Citation17]. The injection speed control, on screen injection progress and ability to pause mid-injection may help improve a patient’s sense of control over the self-injection process [Citation5]; these features were indicated as key preferences for next-generation self-injection devices such as the e-Device in a previous study involving RA, PsA and axSpA patients [Citation23].

Pre-injection ASI results demonstrated that the patients involved in this study were comfortable self-injecting with their current device, reporting low (negative) feelings about self-injection and high self-confidence. Patients still rated the e-Device highly in the post-injection ASI questionnaire and most patients preferred the e-Device over their previous device. This suggests that the e-Device may improve patient satisfaction even when patients are not unhappy with their current self-injection device.

3.2. The individual needs of different patients vary

Overall, 7/65 (10.8%) patients preferred their previous device or had no preference. While this is a small proportion of patients, this result indicates that different patients value different features of a self-injection device [Citation6,Citation24]. Providing the e-Device alongside a portfolio of other self-injection devices allows patients, with the help of HCPs, to choose the right device for their individual needs. Previous studies have indicated that patient satisfaction when using devices to administer treatment is a considerable factor influencing patient adherence [Citation3]. Given that ava® aims to improve patient satisfaction and gives patients reminder notifications for their next injection date, it may be possible that the e-Device improves patient adherence.

3.3. Limitations

The length of this study was limited to two CZP doses, with a maximum of four weeks and four individual CZP self-injections (for the Q4 W subgroup). As a result, patient preference and ratings were based on a small amount of exposure to the e-Device. As such, the results of this study may not be representative of the feelings of patients who have more experience using the e-Device. Differences in dosing regimen resulted in patients in the Q4 W subgroup completing four self-injections with the e-Device, while those in the Q2 W subgroup completed only two self-injections. This variation in experience with the e-Device may have led to differences in patient preference and satisfaction; however, no differences were observed between the two dosing subgroups and so this seems unlikely. The sample size of patients recruited to this study was small and so results from this study may not be generalizable to other patient groups and populations. A criterion for participating in the study was that patients must have been self-injecting CZP for at least three months prior to Visit 1. As all patients had experience of self-injection, the results of this study may not be transferrable to patients who are self-injecting for the first time. Finally, patients opted into this study which may have resulted in selection bias as they be more open to new or different treatment delivery options.

4. Conclusions

Patients, including those with impaired hand function, were able to use the e-Device safely and effectively and rated their experience positively; most patients preferred the e-Device over a CZP PFS. The e-Device may help enhance patient experience and increase CZP treatment adherence, potentially improving clinical outcomes.

Authors contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception and design: D Tatla, I Mountian, B Schiff, B VanLunen, M Schiff; substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of the data: D Tatla, I Mountian, B Szegvari, B VanLunen, M Schiff; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: D Tatla, I Mountian, B Szegvari, B VanLunen, M Schiff; final approval of the version of the article to be published: D Tatla, I Mountian, B Szegvari, B VanLunen, M Schiff.

Declaration of interest

D Tatla, I Mountian, B Szegvari, and B VanLunen are employees of UCB Pharma. M Schiff research/grant support from UCB Pharma; consultancy fees form UCB Pharma. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Data sharing statement

Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers six months after product approval in the US and/or Europe, or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents which may include: analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications, and clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password protected portal.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

RA0098_MS_Supplementary_Section.docx

Download MS Word (184.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, the investigators and their teams who took part in this study. The authors also acknowledge Susanne Wiegratz, UCB Pharma, Monheim, Germany for publication coordination and Oliver Palmer, BSc (Hons), Emma Phillips, PhD, and Simon Foulcer, PhD, from Costello Medical, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Udalova I, Monaco C, Nanchahal J, et al. Anti-TNF therapy. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(4):MCHD-0022-2015.

- Giacomelli R , Afeltra A, Alunno A, et al. International consensus: what else can we do to improve diagnosis and therapeutic strategies in patients affected by autoimmune rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritides, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjogren’s syndrome)?: the unmet needs and the clinical grey zone in autoimmune disease management. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(9):911–924.

- Schwartzman S, Morgan GJ Jr. Does route of administration affect the outcome of TNF antagonist therapy? Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S19–23.

- Sylwestrzak G, Liu J, Stephenson JJ, et al. Considering patient preferences when selecting anti-tumor necrosis factor therapeutic options. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(2):71–81.

- Domanska B, Stumpp O, Poon S, et al. Using patient feedback to optimize the design of a certolizumab pegol electromechanical self-injection device: insights from human factors studies. Adv Ther. 2018;35(1):100–115.

- van den Bemt BJF, Gettings L, Domańska B, et al. A portfolio of biologic self-injection devices in rheumatology: how patient involvement in device design can improve treatment experience. Drug Deliv. 2019;26(1):384–392.

- Larsson I, Bergman S, Fridlund B, et al. Patients’ independence of a nurse for the administration of subcutaneous anti-TNF therapy: A phenomenographic study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2010;5. DOI:10.3402/qhw.v5i2.5146.

- Jacobs P, Bissonnette R, Guenther LC. Socioeconomic burden of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases–focusing on work productivity and disability. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;88:55–61.

- Giacomelli R, Gorla R, Trotta F, et al. Quality of life and unmet needs in patients with inflammatory arthropathies: results from the multicentre, observational RAPSODIA study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(5):792–797.

- Keininger D, Coteur G. Assessment of self-injection experience in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: psychometric validation of the self-injection assessment questionnaire (SIAQ). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:2.

- Maniadakis N, Toth E, Schiff M, et al. A targeted literature review examining biologic therapy compliance and persistence in chronic inflammatory diseases to identify the associated unmet needs, driving factors, and consequences. Adv Ther. 2018;35(9):1333–1355.

- Bluett J, Morgan C, Thurston L, et al. Impact of inadequate adherence on response to subcutaneously administered anti-tumour necrosis factor drugs: results from the biologics in rheumatoid arthritis genetics and genomics study syndicate cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(3):494–499.

- Bayas A, Ouallet JC, Kallmann B, et al. Adherence to, and effectiveness of, subcutaneous interferon β-1a administered by RebiSmart® in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: results of the 1-year, observational SMART study. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12(8):1239–1250.

- European Medicines Agency. Cimzia assessment report. 2018 [cited 2020 April 15]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/cimzia-h-c-1037-ii-0065-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf

- European Medicines Agency. Cimzia summary of product characteristics. 2018 [cited 2020 April 15]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001037/WC500069763.pdf

- United States Food and Drug Administration , Cimzia prescribing information. 2018 [cited 2020 April 15]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125160s283lbl.pdf

- Schiff M, Saunderson S, Mountian I, et al. Chronic disease and self-injection: ethnographic investigations into the patient experience during treatment. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4(2):445–463.

- Duruoz MT, Poiraudeau S, Fermanian J, et al. Development and validation of a rheumatoid hand functional disability scale that assesses functional handicap. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(7):1167–1172.

- Poiraudeau S, Lefevre-Colau MM, Fermanian J, et al. The ability of the Cochin rheumatoid arthritis hand functional scale to detect change during the course of disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13(5):296–303.

- Pouls B, Kristensen LE, Petersson M, et al. A pilot study examining patient preference and satisfaction for ava, a reusable electronic injection device to administer certolizumab pegol. RMD Open. 2019 ;doi: 10.1080/17425247.2020.1736552.

- Schulze-Koops H , Giacomelli R, Samborski W, et al. Factors influencing the patient evaluation of injection experience with the SmartJect autoinjector in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(2):201–208.

- Sheikhzadeh A, Yoon J, Formosa D, et al. The effect of a new syringe design on the ability of rheumatoid arthritis patients to inject a biological medication. Appl Ergon. 2012;43(2):368–375.

- Boeri M, Szegvari B, Hauber B, et al. From drug-delivery device to disease management tool: a study of preferences for enhanced features in next-generation self-injection devices. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1093–1110.

- Kivitz A, Cohen S, Dowd JE, et al. Clinical assessment of pain, tolerability, and preference of an autoinjection pen versus a prefilled syringe for patient self-administration of the fully human, monoclonal antibody adalimumab: the TOUCH trial. Clin Ther. 2006;28(10):1619–1629.