Abstract

The aim of this study was to describe gender-specific career paths of Swedish professional handball players. A reanalysis of Ekengren et al. (Citation2018) career interviews with nine male and nine female players led to creating two composite vignettes using the athletes’ own words, accounted for typical features in the male and female players’ career paths. Seven themes were identified in the analysis of the men’s transcripts and eight themes derived from the women’s transcripts. Further, the themes of both vignettes were aligned with career stages described in our previous study (Ekengren et al. Citation2018). The male players’ vignette is interpreted as a performance narrative congruent with elite handball culture that promotes performance success and profitable professional contracts. The female players’ vignette is more holistic, embracing handball, studies, motherhood, and how they ought to be as Swedish women. Recommendations for future research are provided.

The current study is a part of a project focusing on career development in Swedish handball. In our previous study (Ekengren et al. Citation2018), 18 Swedish professional handball players (nine females) were interviewed about their careers with foci on stages and transitions in their athletic and non-athletic developments. Their data were consolidated into the Empirical Career Model of Swedish professional Handball players (ECM-H) using the holistic athletic career model (Wylleman, Reints, and De Knop Citation2013) as a template. The ECM-H describes four athletic stages – initiation, development (with three sub-stages), mastery (with four sub-stages), and discontinuation – complemented by stages in five layers relevant to: Swedish handball settings, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, and financial developments. When creating the empirical model, gender-specific features of the players’ careers became apparent and of interest for further investigation. We decided to complement ECM-H by descriptions of gender-specific career paths and to make a gender-related reanalysis of the same transcripts but using a different perspective in the data treatment and presentation. The perspective taken in this study is a narrative inquiry in the form of constructing composite vignettes based on the male and female participants’ career stories. Our whole project is inspired by the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers paradigm encouraging researchers and practitioners to blend theory, research, and practice with the athletes’ sociocultural and sports contexts (Stambulova and Ryba Citation2013, Citation2014). In line with the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers, we believe that the ECM-H complemented by findings of this study, can become a basis for developing career long psychological support services for Swedish handball players.

Gender perspective in career research

Existing career development models (e.g. Stambulova Citation1994; Wylleman, Reints, and De Knop Citation2013) present a general career path unfolding from one stage to the next with normative transitions in between the stages. This general career path looks linear and only implies that real careers are typically non-linear and much more diverse (depending on contexts, gender, individual characteristics, etc.) than any model can show us (Stambulova and Ryba Citation2013). Because the majority of career research has focused on male athletes, gender-oriented studies typically compare men and women’s career paths or focus exclusively on women-athletes’ careers or particular transitions (e.g. motherhood). Several researchers (e.g. Ryba and Wright Citation2010; Gledhill and Harwood Citation2015; Ronkainen, Watkins, and Ryba Citation2016; Gledhill, Harwood, and Forsdyke Citation2017; Andersson and Barker-Ruchti Citation2018) emphasized that female athletes’ career studies are scarce and often focus on just describing women’s differences or violations from the men’s ‘norm’.

A study by Tekavc (Citation2017) focused on gender comparison of career challenges in male and female Slovene athletes across development, mastery, and discontinuation stages of their careers based on the holistic athletic career model (Wylleman, Reints, and De Knop Citation2013). Tekavc identified gender non-specific, female-specific, and male-specific challenges in athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, and financial developments across the three aforementioned stages. Female career paths are portrayed as more challenging in total, especially at the development and mastery stages. For example, at the development stage, female athletes struggled with high training demands, pressure from coaches, and the combination of sport and studies that did not allow enough time for recovery; they also more often reported higher stress and lower confidence than male athletes. Recent research on Swedish female elite football players at the development career stage (Andersson and Barker-Ruchti Citation2018) described increasing demands in school and sport that led to the players’ stressful living and stimulated their decision to prioritize sport (more often) or school. Coming back to Tekavc’s study, at mastery stage, female athletes were less satisfied with their training regime and preparations for completions, struggled with coordinating their athletic and gender identities; they reported limited financial and professional support as well as higher physical and mental exhaustion from combining sport and studies than male athletes. Female athletes focused more on education and planning for the future, whereas male athletes more often compromised their academic and vocational careers due to sport. According to Tekavc, a transition to parenthood, although perceived as important by both genders, put much higher impact on women’s careers, often leading to its ending. Usually women terminate in sport earlier than men. As a consequence, women shift their attention to family, childcare, and/or work, and emphasize the importance of a social network, while retired male athletes more often have to get an education before getting a job (Stambulova Citation1994; Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler, and Côté Citation2009; Tekavc Citation2017).

Narrative theory and elite sport narratives

A relatively new line in career research promotes narrative inquiry and adopts narrative theory, helping to capture complexities of individuals’ experiences and multiple interactions between the individuals and their cultures (Ronkainen, Ryba, and Nesti Citation2013; Douglas and Carless Citation2015). Although several authors defined the narrative theory (Smith and Sparkes Citation2008; Phoenix and Sparkes Citation2009; Frank Citation2010; Smith Citation2010), we think that its quintessence is best described by Douglas and Carless (Citation2015):

Narrative theory suggests that through a range of complex and often subconscious psychosocial processes, we all engage in negotiating the fit or tension between what we do (as agentic beings), what we say we do (through our personal stories) and what our culture calls us to do (through publicly available narratives). Culturally available narratives become ‘resources’ that encourage and support particular actions, identities and lives. At the same time, the absence of narrative resources within a particular cultural context is likely to limit or constrain particular actions, identities and lives (p. 44).

Based on narrative enquiry, Carless and Douglas (Citation2009, Citation2013) and Douglas and Carless (Citation2009, Citation2015) explored how stories told by professional women golfers affected their career termination experiences, and how their identities and sense of self were narratively shaped over time by psychological and sociocultural factors. A recurrent topic in their research is how the culture of sport interacts with mental health, development, identity, and life trajectories of elite and professional athletes in highly pressurized environments (Douglas and Carless Citation2015).

The dominant narrative in elite sport is termed a performance narrative, within this story individuals live and act with single-minded dedication towards performance outcome (i.e. winning) and marginalize other areas of life and self (Carless and Douglas Citation2009; Douglas and Carless Citation2009). When athletes for some reason no longer fit or align with this narrative (e.g. underperform, fail), life might become challenging, their identities might be foreclosed, relationships sacrificed in the pursuit of performance success, and long-term well-being threatened (Carless and Douglas Citation2012). In contrast to the above, alternative narratives identified by Carless and Douglas (Citation2009) (i.e. the discovery and the relational narrative) are more holistic. The discovery narrative revolves around exploration and discovery of people, sport, and the world. The relational narrative is about creating, experiencing, and sustaining relationships with other people in and through sport. These alternative narratives add to narrative resources in the context and challenge the dominant performance narrative by demonstrating that athletic career success can be defined differently from simply winning or losing (Douglas and Carless Citation2015). In their research, Carless and Douglas (Citation2012, Citation2013) emphasized that alternative narratives should be recognized by stakeholders on different levels in sport (e.g. athletes, coaches, managers, sport psychologists, and governing bodies) to facilitate diversity of career paths and sustainable sports participation.

Ryba, Ronkainen, and Selänne (Citation2015) described that female athletes often felt the pressure to adhere to the gendered life script that does not include a professional athletic career. Ronkainen, Watkins, and Ryba (Citation2016) revealed that female runners had to internalize a performance narrative to be validated as ‘serious athletes’; they also lacked narratives supportive for being an athlete-mother, and therefore they saw pregnancy and motherhood as the normative end of their athletic careers. Several authors (e.g. McGannon, Gonsalves, Schinke, and Busanich Citation2015; McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018) reported that elite athlete-mothers experience tensions in ‘juggling motherhood and sport’, and they need to develop coping strategies to be able to combine both, and also avoid feelings of guilt when they train, perform, and travel. The authors emphasized the importance of positive athlete-mother narratives encouraging females to continue in sports after giving birth.

Composite vignettes in career research and objective of this study

Composite vignettes feature stories from various people with various experiences and fuse this wide range of experiences into one single story (Spalding and Phillips Citation2007; Blodgett et al. Citation2011). For example, Blodgett and Schinke (Citation2015) used composite vignettes to draw together rich experiences of 13 Aboriginal hockey players. The findings promoted contextual understanding of the participants’ cultural transitions and dual career (sport and education) experiences within the Euro-Canadian context. Schinke and colleagues (Schinke et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017) used composite vignettes to describe acculturation experiences of 24 elite athletes who had immigrated to Canada as teenagers. The vignettes were presented as comprehensive stories around overarching narrative themes and facilitated understanding of the interactions between the ‘whole person’ and the contexts involved (Schinke et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017).

In our previous study (Ekengren et al. Citation2018), we used thematic analysis of the interviews (Braun, Clarke, and Weate Citation2016) to consolidate the themes into the ECM-H. In this study, the same transcripts were reanalyzed aiming to describe gender-specific career paths of Swedish professional handball players by creating two composite vignettes accounted for the typical features in the male and female players’ career stories.

Methodology

To position this study, several choices have been made based on discussions within the research group. First, we chose to hold a relativism stance and portray the male and female players’ career paths from a social constructionism perspective. This means describing reality as created and recreated through interactions with a social context, and also through historical and cultural norms and settings that act in peoples’ lives (Creswell and Poth Citation2017). Second, we selected the narrative inquiry and took a role of storyanalysts (Smith Citation2016) in analysing in parallel male and female players’ interview transcripts and creating themes. Third, continuing within the narrative inquiry we shifted to a role of storytellers and constructed two composite vignettes based on the participants’ own words with the relevant themes serving as the vignettes’ structure (Smith Citation2016). Although the first author played a key role in data collection and treatment, all the other authors were continuously involved in discussing the data, naming themes, and advising on the vignettes’ structure.

Swedish handball as a setting

Handball is a popular team sports in Sweden, with an even distribution between male and female players. There are several possibilities for junior players to combine handball with upper secondary education at elite sport schools. The league consists of mainly semi-professional with few professional players. Due to the financial conditions in the league, senior players often choose to combine their athletic careers with higher education (which permits student loan from the state) or a part-time job. Skilled players strive to sign a professional contract abroad and continue their career in foreign league with higher professionalization and financial incentives.

Participants

The participants were purposefully chosen based on the following criteria: (a) they have had a contract with a professional club for a period of 5 years or more, (b) they had played over 40 international matches in the Swedish senior national team, (c) they perceived themselves to be at the end of their career or terminated not more than four years ago. Eighteen players (nine men and nine women) met the selection criteria and volunteered to take part. At the time of the interviews, the female participants were 28–34 years old (M age = 31.0; SD = 2.1) and had represented Sweden on the average of 89 matches (SD = 35); the male participants were 28-38 years old (M age = 34.9; SD= 2.8) and had represented Sweden on the average of 131 matches (SD = 60).

Interviews

The first author conducted one pilot interview to test the procedure and thereafter one main and one follow-up interview with each of the 18 participants. A semi-structured interview guide (used in Ekengren et al. Citation2018) encouraged the participants to share their career experiences from the holistic perspective (i.e. including both athletic and non-athletic developments). To facilitate the reflections, the first author drew a lifeline and asked the participants to begin their story from the present time: ‘Please, tell me about your current everyday living’. This was followed by more in detail questions, which encouraged the participants to go back along their lifeline until the time when they began playing handball. The questions were formulated in an open-ended manner, for example: ‘How come you began to play handball?’. The participants’ stories were stimulated to be told in a more or less consecutive order, even though moves back and forth in time took place. After the participants had described their athletic careers in relation to a certain time period, focus shifted to life outside sport, asking for example: ‘What happened in your non-sport life during your first year as a senior?’. The author and participants wrote keywords and short notes around the lifeline designating major events related to various periods of their careers. These notes were collected by the interviewer and later useful in the follow-ups and the analysis. Transcripts of the main interviews were sent to the participants to read through and reflect upon. In the follow-up interviews the potential gaps in their career accounts were explored.

Procedure

Ethical approval was received from the regional ethical board. The first author contacted the participants either face to face or by phone, explaining the aim of the study, ethical issues, and logistics of the interviews. The interviews were arranged in time and place convenient to the participants. All main interviews were conducted in-person, three of the follow-ups were done online due to geographical distance. On average, main interviews lasted 87 min (SD = 18), and follow-ups 31 min (SD = 12). Before the main interview participants were reminded about the aim of the study and signed informed consent forms. The first author made verbatim transcripts as soon as possible after each interview to facilitate further interviews.

Data analysis and composite vignettes

Male and female transcripts were separated and treated in parallel. First, influenced by Smith (Citation2016), narrative thematic analysis was used to interpret the players’ narratives. The authors took the stance of storyanalysts giving attention to the content in the players’ stories (i.e. what is said), and identifying the themes within. The analysis began from continuously writing ideas deriving from field notes, the first author’s initial thoughts after the interviews, and from repeated readings of the transcripts (i.e. narrative indwelling). Sometimes it was important to focus just on male or female transcripts separately making inter-individual analysis within each gender group (i.e. what were shared in their stories) and the other times male and female transcripts were contrasted to facilitate understanding of specific features of each gender career path. From these inter-individual and inter-gender comparisons, the first author inductively identified themes describing male and female players’ career paths. These themes were discussed with the other authors, and several were renamed in line with the idea to use the themes to navigate a logic in composing the vignettes on the next stage of the data treatment. In total, seven themes were identified to portray the (shared) career paths for male players and eight themes to describe the same for female players.

In the second stage of the data treatment, the first author shifted to a position of a storyteller (Smith Citation2016) and created drafts of composite vignettes (i.e. creative nonfictions) (Ely, Vinz, Downing, and Anzul Citation1997; Spalding and Phillips Citation2007). These were structured using the participants’ own words and the themes identified during the earlier analysis. Each vignette was composed as a collective and coherent story related to chronology of the career (Smith Citation2016), and by using their own words, the authenticity of the players’ experiences was preserved. The first author translated selected extracts of the transcripts from Swedish to English, and then linked the stories together by connecting sentences, so the vignettes could be read as fluid stories. The other authors were acting as critical friends reviewing and revising the drafts of vignettes several times to establish consistent and meaningful storylines. The writing technique used in this study can be seen as a form of creative analytical practices grounded in empirical data and aimed to merge participants’ experiences, show theory in and through the story, and move the readers toward new, and richer understandings (Richardson Citation2000; Smith, McGannon, and Williams Citation2016; Ivarsson et al. Citation2018).

Findings

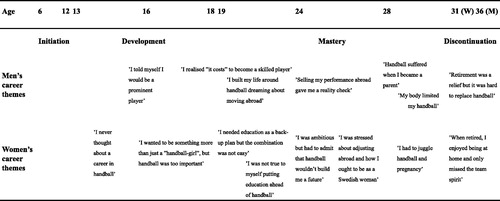

Below we present the two composite vignettes constructed as unified voices from the participants’ own words. Both vignettes roughly follow the stages in a handball career, identified in the ECM-H, but their structures are defined by themes reflecting male and female players’ (contrasting) perceptions and experiences (see ).

Figure 1. Gender-specific themes describing career pathways of Swedish professional handball players.

Composite vignette of male players’ career path

Theme 1: ‘I told myself I would be a prominent player’

Early on, I sought reinforcement through sports. My parents and relatives supported and appreciated me from being good at sports. Maybe that is why I became so dedicated? At first, my dream was to become a football pro, but when I wasn’t selected to regional camps in my early teens I realized that I wasn’t good enough. Instead, I became committed to handball. I followed the senior team in my club, and the [men’s] national team was peaking. I thought I could make a career in handball. I told myself I would be a prominent player.

Theme 2: ‘I realised “it costs” to become a skilled player’

As a junior, I trained a lot. Spending my time in training and at school, I didn’t have any other interests. I managed school being satisfied to pass. I received a contract draft from a Swedish league club that aspired for titles and handball became even more serious. My achievements were uneven, I became anxious about my performance and slept poorly. The coach was virtually inhuman. Altogether, it was a shock for me. We trained so hard, running like greyhounds, and lifting weights as bears. At times I had to throw up. Nevertheless, the coach made me fight and realize that it costs blood, sweat, and tears to be skilled. I didn’t question whether it was the right thing to do. I just did like everyone else, knowing that I could earn good money if I just stuck to the regime. The question was how much I was willing to sacrifice for a professional contract.

Theme 3: ‘I built my life around handball dreaming about moving abroad’

As a first-year senior, I worked to wage my salary from the club. I tried to begin at the University, but my study interest ended quickly. The club employed me to train not to study, and the university didn’t support athletes, so I dropped out. I was able to sign a better contract with my club and could focus solid on handball. I trained extra and prepared for a professional contract abroad that I desired.

Theme 4: ‘selling my performance abroad gave me a reality check’

I chose a club [abroad] that seemed reliable with Scandinavian coach and players. Not one of the biggest clubs with extra expectations from fans and media. I thought I would play at the highest level in a friendly environment, instead I learned that such combination doesn’t exist. I came from having a significant role in the team where the coach let me take important decision both on and off the court. [In the new club] I found myself low in hierarchy, not influencing any decisions and sitting on the bench. I realized that the foundation abroad isn’t to be friends, to have fun, or value team cohesion as in Sweden. Instead, we were united by the desire to win matches. I also had to become an individualist to not be cut off from the team. I wasn’t prepared for the tougher climate and doubted myself and my choice. I longed home, but it was thousand kilometres away. Everyone who said they would come to visit, where were they now? After six months, I got to play due to an injured teammate and I grew with it. Then the team’s losses piled up and the coach got fired. Everything became a big mess. I was treated like a piece of meat, worth nothing. Once again, I questioned the point of it all. But I still wanted to prove that I was a skilled player, able to continuously play on the international level. I searched for a new club. In the discussions about a contract I understood that I couldn’t sit in a negotiation requesting 10.000 €a month, and also expect them to care about me and be nice. I am selling my performance, and they require me to perform and the team to win. I saw myself as a tool, only important when the club benefits from me. Yesterday had no meaning if my current performance was poor.

Theme 5: ‘handball suffered when I became a parent’

My wife and I had a child at the same time as I signed a new contract and we moved to a new town [still abroad]. Becoming a parent was a major shift, one more thing [parenthood] became equally important for me as handball. My performance suffered because I was deprived sleep and didn’t have as much time for [training and match] preparation. Often, I went to training completely exhausted and in periods it was hard to perform. I would have been a better player if we had not shared parental responsibility. My wife was invaluable. I wouldn’t have been able to live without her abroad. The worst thing that could happen was when she got sick and couldn’t take care of the child and the house. It is because regardless of the situation, I had to go to practice when the clock stroked four.

Theme 6: ‘My body limited my handball’

I began to think of a life beyond handball when my body didn’t manage the workload. I didn’t know what I would shift to. Besides handball I had nothing except for my network and language skills that I had built up abroad. I worried about what was next. To move home [to Sweden] was a bigger step than I thought. It took time before my family and I found our routines and felt adjusted. I turned home to my old club as a star, and others assumed that I always would do everything right on the court. I wasn’t prepared for such expectations. I was tired and down in periods. I was used to train twice a day and to be well trained, and then shifting to work [part-time] and train half of the time obviously made me a less good player. I was frustrated, also from my physical soreness, and lived with a bad conscience towards other players.

Theme 7: ‘retirement was a relief but it was hard to replace handball’

To terminate was like walking out of a bubble. I didn’t understand it while being active but it became clear afterwards. It was like something heavy fell off my shoulders. The whole family had the sense of relief, especially my wife after being under pressure for so many years and living my career. I still miss playing in front of a crowd and be at the heart of it with all the appreciation. I miss the daily life as a professional player, which is a privilege for few. I certainly don’t want it undone. The professional life may be hard in periods, but it is difficult to replace it. I don’t know what I could have done instead for the same money and quality. I am happy with my career. I played at the highest level and was important in my teams, but I never was content and thought I needed to prove more in the next training and match.

Composite vignette of female players’ career path

Theme 1: ‘I never thought about a career in handball’

As a child, it was never important for me to succeed in handball, it was fun to participate and be part of a team. I became aware of my ability around the age of 15, when my coach told me and my dad that I could be a skilled player. I remember it so well; she [the coach] was the first person that expressed a belief in me as a player. Her words had proper timing and motivated me, without them I might have quit. I thought handball was only for the gifted and I’ve never seen myself as a talent, rather someone whom worked hard. I didn’t even know there was a women’s national team. I watched the men’s team because they were more successful and in media. I didn’t have a professional league as a goal. It just turned out that way, one thing led to another.

Theme 2: ‘I wanted to be something more than just a “handball girl”, but handball was too important’

At school, I felt rather lonely because other girls questioned my devotion to sports. My teammates developed other interests and had doubts about continuing in handball. So, I made sure I also had other interests – a life outside of sport; a life in which handball wouldn’t dictate the rules of my life. I wanted to be something more than just a “handball-girl”. Thus, my plan was to quit after upper secondary school, similar to my teammates. I wanted to work and then travel the world, and later study at university. But then I received a contract draft from a Swedish league club, an opportunity I couldn’t turn down. Handball was too important for me. I have thought about termination several times during my career but coincidences have kept me going.

Theme 3: ‘I needed education as a back-up plan but the combination was not easy’

I was well aware that I needed an education to get a job. This was my back-up plan. As a senior I studied at the university. It gave me meaningful afternoons [in sport] and kept my mind on something else [than just sport]. Once again, I didn’t want handball to run my life. I struggled but managed the combination. I learned to plan my time, focus on the important things, and made sure I was efficient so I could maintain my alter ego as the handball player. My club had other student-athletes and made the combination possible by letting me adjust my practice schedule. On the flipside, I became stressed from lacking time for additional training, recovery, schoolwork, and not meeting family and friends.

Theme 4: ‘I was not true to myself putting education ahead of handball’

I received drafts from professional clubs but [initially] I wasn’t interested to move. I wanted my university degree, and I wanted to raise a family. Thoughts on building a family have probably limited my efforts and restricted me from having goals of becoming one of the best. I thought that the combination [with kids] wouldn’t work so I settled with playing one season at a time, waiting for my family plans to fold into place. I performed and studied without thinking about opportunities in handball. Then it struck me that I wasn’t true to myself. I spent so much time in training and sacrificing my living outside handball and still didn’t dedicate myself to the game. So, I made a statement to focus on handball, take a part-time job with flexible hours and together with the wage from the club make a living. The job was just for money but it made my struggle possible. I slept, ate, and did everything for handball, realising it was possible to move abroad. The curiosity to know how successful I could be, along with the adventure of living in another country, and learning another language drew me towards a professional league. But my efforts to run extra and perform additional drills made my teammates questioning why I was doing it. I found it awkward to explain, and they didn’t seem to understand. They had a totally different view, wanted to avoid workload and additional strain. I continued to do my thing, but it was strange to be questioned when trying to become the best you can.

Theme 5: ‘I was ambitious but had to admit that handball wouldn’t build me a future’

I searched for better conditions to perform, to lower my stress, and be able to recover between matches. I knew that I wouldn’t live off handball. I couldn’t just move abroad for a few years and make money, that is an illusion. It is completely different money than in the men’s game, and women need to be among the best in the world to get comparable income. I couldn’t save money for the future, because I only had enough to pay daily expenses. It feels strange that I do the same things [as men do] but get less. Sure, men might have more pressure from playing in front of bigger crowds. Still it is human dignity to work and get a salary, but to work hard for a fraction is unfair, unworthy. The reason is that I am a woman.

Theme 6: ‘I was stressed about adjusting abroad and how I ought to be as a Swedish woman’

I moved abroad and it was quite tough at first. I didn’t find my role, became stressed, and didn’t act on court like I used to. It resulted in limited playing time. It also had to do with the foreign language that I couldn’t speak. My humour used to help me in social situations, as a way to get in touch with people, but suddenly I couldn’t use it. I became a quiet girl and panicked from not getting the social codes and being misunderstood. I couldn’t show who I was as a person. Altogether, it was hard, I wanted to move back home and terminate my career. The social norms stressed me in regard of how I ought to be as a Swedish woman that is expected to follow the prescribed image of working nine to five, having a house, a Volvo hatchback, a dog, and two kids. Keeping this in mind I took one year at a time and signed short-term contracts to be able to move back home, if things went wrong.

Theme 7: ‘I had to juggle handball and pregnancy’

The idea to stop playing appeared frequently. I still had to justify my choice to play, for example, when old friends asked what I did for a living, thinking handball was only a hobby. When I answered: ‘I’m professional’, they were surprised: ‘Oh, so you still play and you earn money on that?’; it was like they said: ‘When will you grow up?’ At the same time, we played in Champions League, flew private jet to matches, and everything in my life was about performance. It was two worlds colliding: elite sport where people shared my values and the rest of the life where I often was misunderstood. Life after sport scared me. I dwelled on what would happen in the years to come. It was easier to stay in handball knowing the routines. When renewing my contract, the club manager tried to find out whether I was planning to become pregnant. He couldn’t ask it straight out but was obviously eager to know. I approached my 30 s and thought I should try to become pregnant. I signed without sharing my thoughts because I didn’t expect to get pregnant so fast. I thought it would take a year, but it didn’t. I played pregnant up until the thirteenth week without telling anyone. But then I started to throw up in the mornings, feeling unwell, and wondering: ‘What if I will hurt the child?’ Finally, I couldn’t keep it secret, I arranged a meeting with the manager and we terminated the contract. My impression of the club was great; they cared about me even when I needed to cancel my contract. I lost a victorious adventure, but instead I got something a lot better.

Theme 8: ‘when retired, I enjoyed being at home and only missed the team spirit’

I came back home [to Sweden] and moved together with my partner, who during my athletic career had been living in Sweden. I thought it was nice to finally move home, be pregnant, and get rid of my athletic demands. I was fed up with always performing and living in a temporarily home. Thinking back, I’d changed residence for so many times, and had many shallow acquaintances in different places. I didn’t know where I belong and was uncertain about myself as a person. Maybe because I was trying to fit in to every new environment. When having children, handball becomes secondary. Being a mum, I tried to play in Sweden, but it put additional strain on my family with all the travelling, and I didn’t want to be away from my family once again. I also had a number of minor injuries, and my motivation was low because I couldn’t perform to my standards. I guess I was done mentally and my body said ‘no more’. I took the decision to terminate. I’d pushed myself to the extreme for so many years. I realized that there weren’t many of my kind. I don’t miss handball, but I miss the team spirit.

Vignettes aligned with career stages

To facilitate discussion of the findings, we have arranged male and female players’ themes that helped to compose the vignettes, along the career stages to make the gender-specific career paths relevant to the ECM-H (). Contrasting male and female players’ experiences at the different career stages will help to complement the discussion of each vignette as a whole.

Discussion

We begin with summaries of the male and female vignettes, then provide a comparison of the gender-specific career paths across career stages (based on ) and conclude with limitations, further research, and applications.

Summary of male players’ vignette

Throughout their careers, male players create, maintain, and live the performance narrative (Carless and Douglas Citation2009) centralizing winning, prestigious professional contracts and a good income. Already at the beginning of the development stage they begin to adopt a handball player identity and dream about high performance and a successful career. The vignette describes the junior-to-senior transition as a stressful turning point questioning their previous (junior level) assumptions and experiences when facing higher standards in practice and matches in the elite team. The junior-to-senior transition is described as one of the most critical transitions in an athletic career with only a fraction of athletes successfully progressing to the elite senior level (Stambulova and Wylleman Citation2014; Wylleman, Rosier, and De Knop Citation2015). Luckily, our participants were within that minority who managed the transition well. After secondary school graduation, the male vignette tells an even more single-minded story around performance-related concerns in the sport. Moving abroad was associated with a remarkable orientation to productivity in games and winning. The vignette reveals stories of being treated as a merchandize and trying to adapt in a more competitive and less supportive environment than in Sweden. The male players shared that they typically moved abroad together with their life partners and became parents at a truly intense period of their careers (e.g. playing for the foreign club and the national team). Fatherhood was portrayed as equally important to sport but also associated with major costs related to time constrains, fatigue, and decreased drive for performance (Tekavc Citation2017). The decision to move back to Sweden and prepare for the career termination was difficult and elevated emotional discomfort related to uncertainty for the future (Stambulova Citation2017). At the same time, performance narrative continued to influence them even after retirement because they missed being in a spotlight and tried keeping strong.

Summary of female players’ vignette

The female vignette frequently shifts plot between the discovery, relational, and performance narrative. From their adolescence years, female players are like chameleons, trying to adjust and melt into the different context (e.g. handball, school, social settings) to be appreciated. Carless and Douglas (Citation2013) described it as a woman playing a role of an athlete while being in the sport context but significantly marginalizing her athletic identity being in other contexts. Gledhill and Harwood (Citation2015) studied British female football players who failed in the junior-to-senior transition and emphasized contributions of significant others (parents, teachers, peers) who expressed doubts in the players’ success on the senior level, marginalized their athletic identity, and inclined them to terminate. The female players participated in our study perceived their careers as unstable and were several times ready to quit because of limited opportunities (e.g. money), female role models, and in line with Ronkainen, Watkins, and Ryba (Citation2016), seeing sport as an ‘project of youth’. Still the vignette illustrates that women in spite of doubts and disadvantages found handball too important to let it go. After school, females developed a back-up plan due to awareness of insufficient money and limited professional handball opportunities. The plot of the female vignette reveals stressful living caused by demands of performing well not only in sport but also academically and socially (Gledhill and Harwood Citation2015; Tekavc Citation2017; Andersson and Barker-Ruchti Citation2018). Throughout their handball careers, female players tried to adopt the dominant (and male-oriented) performance narrative, and when they did feel a poor fit with it, they developed side storylines related to their academic, social, gender, and cultural identities (e.g. Franck and Stambulova Citation2018). For example, at some point they had to navigate their Swedish female identity in relation to gendered cultural values and norms (Ryba, Ronkainen, and Selänne Citation2015; McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018) prescribing women to have family, kids, and a job different from just ‘throwing a ball’. Pregnancy was seen as an important turn in life but also a barrier for continuing the professional handball career. While several females tried to make a comeback and ‘juggle motherhood and sport’ (McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018), others preferred to invest in family life and get a job in line with their previous education.

Comparison on gender-specific paths across career stages

As seen in , we did not find any gender-specific themes related to the initiation stage. As shown also in Ekengren et al. (Citation2018), at the beginning of their careers both boys and girls do handball (most often together with some other sports) just to have fun and share good time with peers and family members. Only since the development stage, gender differences are getting visible. Male players being early adolescents are already ‘fed’ by narrative resources in the Swedish handball culture telling them: if you work hard and become skilful, it is possible to become ‘a prominent player’ (meaning to reach national team and/or a professional contract). This narrative is in line with the promotion of men in the athletic culture and Western societies, which also might impede women’s athletic career development, because they lack exemplary narratives (Ronkainen, Watkins, and Ryba Citation2016). Sport-orientated narrative resources within the handball culture encouraged the male players to become single-minded towards handball, especially after finishing compulsory school. Consequently, their strong handball identity worked at this stage as a resource for their training and athletic achievements but also created a risk for athletic identity foreclosure and vulnerability in the case of unexpected career termination (e.g. Stambulova and Wylleman Citation2014). In contrast, female players at the development stage missed female role models in sports and media and were typically unaware about career opportunities in handball and also about their handball abilities/talent. They focused more on school and social life (than male players) trying to be good at several things and to become ‘something more than just a handball girl’. This made their living stressful since they did not commit to anything fully, but kept expectations to excel in different contexts. They needed someone (e.g. coach or parent) to persuade them that they had a sport talent worth to be developed and turned into a career. Usually coaches were significant others who pushed them into the performance narrative and motivated them for increasing their effort and commitment to the sport. At the same time, female players’ adherence to the performance narrative across the career looks unstable, with repetitive shifts in and out of it.

At the mastery stage, male players continued to build their performance narrative organizing their life around handball, selling their performance competencies abroad, and being ‘disrupted’ in handball only by fatherhood and then by physical and mental exhaustion after about ten years in elite sports. In contrast, female players continued to shift between elite handball, higher education, and life of an adult woman. They reflected on gender inequality in conditions for the professional career and ‘a must’ for them to have a back-up plan and prepare for career termination. Tekavc (Citation2017) portrayed female career paths as more challenging physically, psychologically, socially, and financially compared to men. This was true for our female participants who struggled to be good against the odds. The Swedish culture prescribed them to get an education, family, and a good job, and it was uneasy to explain to other people why they invested in handball and ignored the available cultural norm. Motherhood was usually planned (in relation to ‘timing’ within the athletic career) but also was more disrupting for the career in female players than in the case of men, and many females perceived having a child as the end of the athletic career (e.g. Tekavc Citation2017; McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018).

Throughout their careers, female players were more anxious about their future (e.g. signed only short-term contracts) but also were better prepared for the discontinuation stage than male players (e.g. in terms of education and a more holistic life narrative). Both men and women experienced relief from the responsibility to maintain performance, especially when the body often said ‘no’. However, there were differences in terms of what they missed from elite sport: males found it difficult to replace the adrenalin rush and recognition they experienced, while females missed mainly team-ship and spirit.

Methodological reflections, future research, and applications

The social constructionism perspective aided us to reveal the nuances of gender-specific career paths in Swedish handball players. In our research group, we have had a good gender balance that was helpful when the vignettes’ first drafts created by the first author (a white, heterosexual male) were read and critically reflected upon by both male and female co-authors. Accordingly, the vignettes were revised several times until they were inclusive for different participants’ experiences, evoked transferability (Smith Citation2018), and invited the readers to fill in details based on what resonated with them and the athletes they work with. Keeping in mind that ‘each reader’s interpretation can be unique, adding a further dimension’ (Spalding and Phillips Citation2007, p. 958), we hope to encourage future career research exploring athletes’ various identities and development in different sporting and sociocultural contexts, as recommended by the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers paradigm (Stambulova and Ryba Citation2013, Citation2014). Although our vignettes are created from the social constructionism perspective that features a subjective and mind-dependent reality, we think our findings have a potential to be applicable in other team sports and cultures depending on what the readers can discern as applicable (Smith Citation2018). The next step in our project is to develop and test career long psychological support services for Swedish handball players based on the ECM-H and current findings of gender-specific career paths. The practical worth of vignettes is not in providing a truth but serving as representations that can stimulate reflection and improve action (Spalding and Phillips Citation2007). For example, our findings challenge the illusion of a career as a steady progress, by demonstrating a number of turning points and relevant ups and downs in the players’ careers. Other lesson to learn from this study is about a need in diverse narrative resources circulating in sports contexts to confront and destabilize the dominant performance narrative (e.g. Carless and Douglas 2015). Findings from our study can be useful for player-, coach-, and parent education on different levels in Swedish handball (e.g. elite sport schools, clubs, federation) to raise these stakeholders’ awareness of diverse career paths and aiming to promote sustainable handball careers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the players whom devoted their time and shared their career stories.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest relevant to the content of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, R., and N. Barker-Ruchti. 2018. “Career Paths of Swedish Top-Level Women Soccer Players.” Soccer & Society. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2018.1431775.

- Blodgett, A. T., and R. J. Schinke. 2015. “When You’re Coming from the Reserve You’re Not Supposed to Make It”: Stories of Aboriginal Athletes Pursuing Sport and Academic Careers in “Mainstream” Cultural Contexts.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 21: 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.001.

- Blodgett, A. T., R. J. Schinke, B. Smith, D. Peltier, and C. Pheasant. 2011. “In Indigenous Words: Exploring Vignettes as a Narrative Strategy for Presenting the Research Voices of Aboriginal Community Members.” Qualitative Inquiry 17: 522–533. doi: 10.1177/1077800411409885.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and P. Weate. 2016. “Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research.” In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, edited by B. Smith, and A. C. Sparkes 191–205. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2009. “We Haven’t Got a Seat on the Bus for You’ or ‘All the Seats Are Mine’: Narratives and Career Transition in Professional Golf.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 1: 51–66. doi: 10.1080/19398440802567949.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2012. “Stories of Success: Cultural Narratives and Personal Stories of Elite and professional athletes.” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 13 (3): 37–41. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2012.657793.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2013. “Living, Resisting, and Playing the Part of Athlete: Narrative Tensions in Elite Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 14 (5): 701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.05.003.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Douglas, K., and D. Carless. 2009. “Abandoning the Performance Narrative: Two Women’s Stories of Transition from Professional Sport.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 21 (2): 213–230. doi: 10.1080/10413200902795109.

- Douglas, K., and D. Carless. 2015. Life Story Research in Sport: Understanding the Experiences of Elite and professional athletes through narrative. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ekengren, J., N. B. Stambulova, U. Johnson, and I.-M. Carlsson. 2018. “Exploring Career Experiences of Swedish Professional Handball Players: Consolidating First-Hand Information into an Empirical Career Model.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2018.1486872.

- Ely, M., R. Vinz, M. Downing, and M. Anzul. 1997. On Writing Qualitative Research: Living by Words. London, UK: Falmer Press.

- Franck, A., and N. B. Stambulova. 2018. “Individual Pathways through the Junior-to-Senior Transition: Narratives of Two Swedish Team Sport Athletes.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2018.1525625.

- Frank, A. W. 2010. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-narratology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Gledhill, A., and C. Harwood. 2015. “A Holistic Perspective on Career Development in UK Female Soccer Players: A Negative Case Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 21: 65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003.

- Gledhill, A., C. Harwood, and D. Forsdyke. 2017. “Psychosocial Factors Associated with Talent Development in Football: A Systematic Review.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 31: 93–112. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.04.002.

- Ivarsson, A., U. Johnson, J. Karlsson, M. Börjesson, M. Hägglund, M. B. Andersen, and M. Waldén. 2018. “Elite Female Footballers’ Stories of Sociocultural Factors, Emotions, and Behaviours Prior to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2018.1462227.

- McGannon, K. R., C. A. Gonsalves, R. J. Schinke, and R. Busanich. 2015. “Negotiating Motherhood and Athletic Identity: A Qualitative Analysis of Olympic Athlete Mother Representations in Media Narratives.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 20: 51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.010.

- McGannon, K. R., J. McMahon, and C. A. Gonsalves. 2018. “Juggling Motherhood and Sport: A Qualitative Study of the Negotiation of Competitive Recreational Athlete Mother Identities.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 36: 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.008.

- Phoenix, C., and A. C. Sparkes. 2009. “Being Fred: Big Stories, Small Stories and the Accomplishment of a Positive Ageing Identity.” Qualitative Research 9 (2): 219–236. doi: 10.1177/1468794108099322.

- Richardson, L. 2000. “New Writing Practices in Qualitative Research.” Sociology of Sport Journal 17 (1): 5–20.

- Ronkainen, N. J., T. V. Ryba, and M. S. Nesti. 2013. “The Engine Just Started Coughing!’ – Limits of Physical Performance, Aging and Career Continuity in Elite Endurance Sports.” Journal of Aging Studies 27: 387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.09.001.

- Ronkainen, N. J., I. Watkins, and T. V. Ryba. 2016. “What Can Gender Tell us about the Pre- Retirement Experiences of Elite Distance Runners in Finland?: A Thematic Narrative Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 22: 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.003.

- Ryba, T. V., and H. K. Wright. 2010. “Sport Psychology and the Cultural Turn: Notes Toward Cultural Praxis.” In The Cultural Turn in Sport Psychology, edited by T. V. Ryba, R. J. Schinke, and G. Tenenbaum 1–28. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Ryba, T. V., N. J. Ronkainen, and H. Selänne. 2015. “Elite Athletic Career as a Context for Life Design.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 88: 47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.02.002.

- Schinke, R. J., A. T. Blodgett, K. R. McGannon, and Y. Ge. 2016a. “Finding One’s Footing on Foreign Soil: A Composite Vignette of Elite Athlete Acculturation.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 25: 36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.04.001.

- Schinke, R. J., A. T. Blodgett, K. R. McGannon, Y. Ge, O. Oghene, and M. Seanor. 2016b. “A Composite Vignette on Striving to Become” Someone” in my New Sport System: The Critical Acculturation of Immigrant Athletes.” The Sport Psychologist 30: 350–360. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2015-0126.

- Schinke, R. J., A. T. Blodgett, K. R. McGannon, Y. Ge, O. Oghene, and M. Seanor. 2017. “Adjusting to the Receiving Country outside the Sport Environment: A Composite Vignette of Canadian Immigrant Amateur Elite Athlete Acculturation.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 29 (3): 270–284. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2016.1243593.

- Smith, B. 2010. “Narrative Inquiry: Ongoing Conversations and Questions for Sport and Exercise Psychology Research.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 3 (1): 87–107. doi: 10.1080/17509840903390937.

- Smith, B. 2016. Narrative Analysis in Sport and Exercise: How Can it be Done? In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, edited by B. Smith, and A. C. Sparkes 260–273. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Smith, B. 2018. “Generalizability in Qualitative Research: Misunderstandings, Opportunities and Recommendations for the Sport and Exercise Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 137–149. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2008. “ Contrasting Perspectives on Narrating Selves and Identities: An Invitation to Dialogue.” Qualitative Research 8 (1): 5–35. doi: 10.1177/1468794107085221.

- Smith, B., K. R. McGannon, and T. L. Williams. 2016. “Ethnographic Creative Nonfiction: Exploring the What’s, Why’s and How’s.” In Ethnographies in Sport and Exercise Research, edited by G. Molner, and L. Purdy 59–73. London, UK: Routledge.

- Spalding, N. J., and T. Phillips. 2007. “Exploring the Use of Vignettes: From Validity to Trustworthiness.” Qualitative Health Research 17: 954–962. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306187.

- Stambulova, N. B. 1994. “Developmental Sports Career Investigations in Russia: A Post- Perestroika Analysis.” The Sport Psychologist 8 (3): 221–237.

- Stambulova, N. B. 2017. “Crisis-Transitions in Athletes: Current Emphases on Cognitive and Contextual Factors.” Current Opinion in Psychology 16: 62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.013.

- Stambulova, N. B., D. Alfermann, T. Statler, and J. Côté. 2009. “ISSP Position Stand: Career Development and Transitions of Athletes.” International Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 7 (4): 395–412. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671916.

- Stambulova, N. B., and Ryba T. V. (Eds.). 2013. In Athletes’ Careers across Cultures, edited by N. B. Stambulova, and T. V. Ryba. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Stambulova, N. B., and T. Ryba. 2014. “A Critical Review of Career Research and Assistance [Mismatch] through the Cultural Lens: Towards Cultural Praxis of Athletes’ Careers.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 7 (1): 1–17.

- Stambulova, N. B., and P. Wylleman. 2014. “Athletes’ Career Development and Transitions.” In Routledge Companion to Sport and Exercise Psychology, edited by A. Papaioannou, and D. Hackfort 605–621. New York: Routledge.

- Tekavc, J. 2017. Investigation into Gender Specific Transitions and Challenges Faced by Female Elite Athletes. Brussels, Belgium: Vubpress.

- Wylleman, P., A. Reints, and P. De Knop. 2013. “A Developmental and Holistic Perspective on Athletic Career Development.” In Managing High Performance Sport, edited by P. Sotiaradou, and V. De Bosscher 159–182. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wylleman, P., N. Rosier, and P. De Knop. 2015. “Transitional Challenges and Elite Athletes’ Mental Health.” In Health and Elite Sport. Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit?, edited by J. Baker, P. Safai, and J. Fraser-Thomas (Vol. 38, pp. 99–116). New York, NY: Routledge.