Abstract

This article presents an analytical framework for understanding and studying the value structures that govern participation in sport. We combine insights from a Norwegian Monitor survey with existential philosophical reasoning to present an empirically based value structure and discern three fundamental ways of engaging in sport: being, having and belonging. We argue that distinguishing between these modes of engagement can contribute to describing, analysing and navigating in the variety of ways that participants engage in sport. Using friluftsliv and football as illustrative cases, we analyse how these existential dimensions can be prevalent in different forms of participation. Towards the end of the article, we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of our approach, and how the existential dimensions may relate and intertwine in practice.

Introduction

Values of various kind infuse sports and movement cultures. In addition to sport-specific values, sport has historically promoted and reinforced social values. Sports are embedded in societies and have histories that in complex ways interact with developments in the surrounding communities. All sports are, thus, carriers of values of various kinds, and these values may oppose or mirror values in the surrounding society (Breivik Citation1998). Besides this, participants engage in sports on various grounds and for a variety of reasons (Seippel Citation2006). Some take part to express specific values and lifestyle preferences, while others are more passively drawn into sports and its internal values. The plurality of values in sport has been investigated in a variety of ways, for example from sport philosophical viewpoints (see McFee Citation2004; Kretchmar Citation2015) as well as in empirical sociological approaches (Mclean and Hamm Citation2008). More detailed analyses of how sports are carriers of specific social values related to different groups of sport participants are found in national surveys (see e.g. Pran and Spilling Citation2018). As an analytical background for understanding the relationship between participants, sport and society, we draw on a general account of two dialectical interaction processes (Breivik Citation1998). The first dialectic concerns the interaction between sport and society. It involves a two-way process where a) sports in their different versions are, and have historically been, influenced by societies, and b) the values of sports influence the societies they are parts of. A second dialectic involves an interaction between persons and specific sports, where people a) seek sports, or develop new sports, that match their interests and values, and b) are influenced and socialised by values of the sports they take up.

In this paper, we focus on the second dialectic and discuss values in sport by discerning three general ways of engaging in sport: 1) being, 2) having and 3) belonging. We derive these existential dimensions from the results of an extensive empirical survey (the Norwegian Monitor), and we argue that distinguishing between them can contribute with an analytical framework which can help to describe, analyse and navigate in the variety of values that govern sporting engagement. In line with the Nordic term ‘idrett’, from the old Viking word ‘idtrott’ which meant ‘strong activity’, we will use the term ‘sport’ in a wide sense to include traditional sports and other movement cultures, such as the Norwegian tradition of ‘friluftsliv’. On this basis, we describe how friluftsliv and football can illustrate different versions of the interaction between sports, the surrounding society, and the participants. Friluftsliv represents a movement culture that has a special meaning in Norway while football represents a traditional and global sport. Each of these can illustrate the various ways of engaging in sport, depending on the social values of society and the existential grounds for participation.

Understanding engagement in sport

An empirically based value structure

As an empirical background for understanding the values in sport, we will use findings from a large empirical survey called Norwegian Monitor. The Norwegian Monitor survey has been conducted every second year since 1985. The study is based on interviews with a representative sample of the Norwegian population from the age of 15. It consists of around 4.000 respondents per round, which amounts to over 60.000 interviews over 30 years (Pran and Spilling Citation2018). The study examines values, attitudes, socio-cultural background and behaviour, and it focuses on various areas of life, including participation in sport. Data from the study have been used to analyse the level of participation in sport (Fridberg Citation2010; Breivik and Hellevik Citation2014). For our present purpose, we focus on how it provides an empirically based value structure that can help understand the relationship between values and ways of engaging in sport.

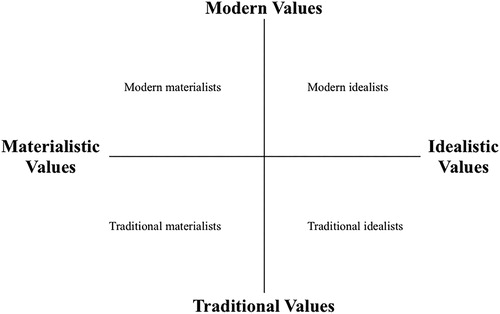

The survey includes 51 values. The values are of three kinds. Personal values comprise values that relate to a person’s attitudes, preferences and behaviour. Inter-personal values encompass values formed in human interaction. Social values are values that characterise aspects of society. By use of factor analysis, the values in the survey have been mapped along two axes as shown in (see Hellevik Citation2008), which order the values along a dimension of modern versus traditional values (the vertical) and a dimension of idealistic versus materialistic values (the horizontal). This basic structure has remained remarkably stable during the period, though some values have changed position and peoples’ attachment and support for different values have varied to some extent. It means that it is a relatively stable value structure, representing how the general population experience values and how the values relate to each other.

The two axes order the values into four quadrants and thus characterise four different sets or types of value. The modern idealist values are dominant when people define themselves through what they are and the way they live. They typically support values like anti-authority, equality, tolerance, individuality, self-realisation, altruism, and environmental protection. The modern materialist values are dominant when people define themselves through what they have, for example, material goods or skills that give status and prestige. They support values like risk, consumption, law contempt, non-religious, technology, and hedonism. The traditional idealist values are dominant when people define themselves as belonging to something larger, for example, a nation, a church, or nature. They support values like religion, rigidity, puritanism, law-abiding, rural, tradition, investment, and security. The traditional materialist values are dominant when people define themselves as belonging to a party, a worker’s union, or a local place. They support values like rationality, prudence, conformity, traditional gender roles, patriotism, authority, industrialism, and a non-egalitarian attitude.

An existential approach to values in sport

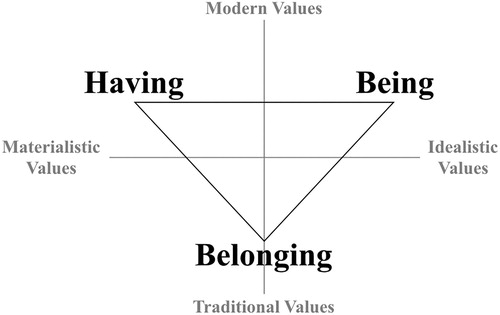

From the brief presentation of the value structure in the Norwegian Monitor survey, we proceed with an existential philosophical analysis to provide a more detailed examination of the social values expressed in the empirical data. We aim to use existential philosophy to achieve a better understanding of the existential grounds for engaging in sport. Since people with traditional idealist and traditional materialist values both define themselves through what they belong to, we find it reasonable to interpret the four socio-cultural types of value, as representing three existential dimensions that emphasise 1) being, 2) having and 3) belonging. In this way, the social value structure in the Norwegian Monitor survey provides an empirical background for an analytical distinction between three existential modes of engagement in sport. We illustrate this analytical framework in .

We use the three existential dimensions as descriptive categories. Hence, we do not conceive of them as moral distinctions and we do not make any normative claims about them like, for example, that it is better to engage in one mode than another. Also, we do not see them as exclusive in the sense that engaging in one mode excludes the other modes. Our view is that their prevalence is a matter of degree rather than either-or. Later in the discussion, we will have more to say about the ways they relate and intertwine in practice, but first, we want to clarify the analytical distinctions by describing the distinct features of each dimension.

Being

Engagement in the mode of being describes a free and active engagement, with a focus on inherent values and experiential qualities. In his work To Have or To Be? Erich Fromm (Citation2008) drew on philosophical accounts of being as becoming, to analyse the being mode of existence as aliveness, process, activity, and movement as central elements in being. Hence, the mode of being is associated with an active subjectivity, but not in the sense of busyness or outward activity. Fromm (Citation2008, 72-78) drew on Spinoza to describe activity in the mode of being as giving expression to our human powers, making use of our (critical) reasoning, being interested and open for experiencing and being the subject of one’s activity. It also concerns a view of activity as autotelic, i.e. you see an activity as inherently valuable and are engaged in for its own sake.

In Jean-Paul Sartre’s (Citation2003) philosophy, he relates the mode of being to the freedom to act. It implies an element of autonomy, and it describes a way of being engaged in the world, either in one’s free project (choice) or one’s situation (facticity). As an example of this Sartre mentions the activity of playing, and he argues that ‘the desire to play is fundamentally the desire to be’ (581).

The mode of being also describes a particular relation to one’s body. Gabriel Marcel (Citation1949) distinguished between being and having a body. Being a body describes the body as subject, which resembles the phenomenological notion of the lived or phenomenal body (Merleau-Ponty Citation2012). It describes an embodied subjectivity, where the body is the tacit and pre-reflective background of our experience of, and engagement with, the world.

Having

Engagement in the mode of having describes a focus on possession and appropriation. It emphasises participation for the sake of achieving, producing or gaining something. Fromm (Citation2008, 21) argued that: ‘In the having mode of existence my relationship to the world is one of possessing and owning, one in which I want to make everybody and everything, including myself, my property’. He also described the mode of having as centred on profit and property, and he analysed it as involving a desire for power, ownership, superiority or control in the relation to others (66). It concerns a view of activity as instrumental, i.e. you value an activity for what you achieve from it and what the activity produces. Activities are, therefore, means for other ends. Hence, they are engaged in for the sake of ends external to the activities.

Sartre (Citation2003, 581 ff.) paid special attention to the appropriative attitude involved in the mode of having. As examples of this, he described scientists who gain knowledge and artists who create a work of art. He also described an appropriative component in sport. We can relate this to the acquisition of skills, a desire for achieving a good performance, for beating a record or for overcoming difficulty and resistance.

The mode of having also involves a special relation to one’s body. Marcel argued that having a body implies seeing the body as an object. It is the physical body which one can take care of by exercising, forming and shaping it. In phenomenological terms, it relates to the body image, i.e. the body when it is the object of our attention, or we present it as an object that appears for others.

Belonging

Engagement in the mode of belonging describes a particular way of being related to one’s situation. In his work Human Space, Bollnow (Citation2011) analysed dwelling as an important existential category. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty (Citation2012) notion of dwelling [habiter] and the role of dwelling [wohnen] in the later philosophy of Heidegger (Citation1993), Bollnow argues that dwelling is a central aspect of human existence, which has primacy over intentionality and is decisive with regard to our relationship with the world. It can contribute to overcoming the human condition of ‘thrownness’ and it can describe how human beings can avoid feelings of alienation and estrangement. Dwelling describes how people can find meaning in being grounded and bound to a place, ‘to dwell means to be at home in a particular place, to be rooted in it and belong to it’ (Bollnow Citation2011, 121). Dwelling understood as an original relationship with the world is, therefore, central to understanding engagement in the mode of belonging. It denotes a sense of homeliness and rootedness, which can relate to various aspects of one’s situation, including relations with the concrete surroundings, a house, a place, a city, coexistence with others, a community, a group, one’s environment, a social class, an institution, a nation, nature, a culture, etc.

This conception of dwelling has provided an ontological foundation for accounts of belonging in phenomenological sociology (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966), and phenomenological geography (Relph Citation1976; Seamon and Mugerauer Citation1985). The latter of these has contributed with an informative distinction between space and place. While space describes the objective dimension of one’s surroundings such as one’s location, place experience is central to belonging because it is subjective and lived. It is, therefore, a qualitatively different relationship that develops over time and enables people to feel that they inhabit and feel at home where they are, which is constitutive for individual meaning and identity.

Belonging is, thus, central to understanding how people belong to places, but it can also contribute to describing coexistence with others. The communitarian dimension of belonging concerns moods, social values, shared ethos, norms, language, traditions, etc. Here, engagement in the mode of belonging can involve paying attention to shared social values of one’s practice, which can involve experiential aspects such as sharing a heritage, expectations and obligations. The late philosophy of Sartre (Citation2004) paid much attention to cooperation and mutual dependency in collective existence. This focus was an attempt at developing his existential philosophy in a Marxist direction and described the main dimensions of belonging to a group, such as fraternity, function and power. These are central in belonging to, for example, a team where contracts, roles and agreements bind members together. This dimension of belonging involves dimensions such as solidarity, trust, identification, or commitment.

Analysing ways of engaging in Sport - Examples from friluftsliv and football

The following seeks to make use of the analytical distinctions and illustrate how the three existential dimensions can contribute to understanding different ways of engaging in friluftsliv and football. We are theoretically applying the framework and we want to stress that the existential dimensions do not necessarily relate to specific activities. Also, particular ways of organising sport do not necessarily prescribe specific modes of existence among participants. The existential mode of engagement depends both on the social values of society and sport, and on the values and attitudes of participants. With this in mind, our aim is to illustrate how the three existential modes of engagement can be enacted in different forms of participation.

Norwegian friluftsliv

Sport and various forms of active outdoor life have long traditions in Norwegian society. While many countries have developed their own versions of outdoor activities, many proponents of Norwegian friluftsliv think the Norwegian practice of outdoor life is special in at least two respects: First, a large part of the population takes part; around two-thirds of the adult population practice friluftsliv regularly, i.e. at least every month. They hike or walk in the woods or mountains, they ski or bicycle, use a canoe or a sailboat or go fishing. This high level of participation is possible because a small population of 5,3 million people have a large playground in the woods and mountains. Second, many Norwegians think friluftsliv involves specific values, a particular ideology of being outdoors with simple means, free and close to nature and with a deep respect for the wilderness. Nature is, thus, considered a central part of Norwegian national identity (Reed and Rothenberg Citation1993).

As mentioned earlier, the Norwegian word for sport is ‘idrett’, but we also use the term ‘sport’, which relates to the English sport tradition that came to Norway in the second half of the 19th century. The special Norwegian word for outdoor life, friluftsliv, was first used in a poem by Henrik Ibsen in 1863 and literally means ‘life in the open and free air’. While many Norwegians thought friluftsliv could go hand in hand with idrett and sport, others, like the polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, thought they should be clearly distinguished. The argument was that friluftsliv was non-competitive, used simple equipment and had a focus on experience rather than performance. In friluftsliv nature was something to be experienced and valued for its mystery and complexity, while in sport nature functioned as an arena for displaying competitive skills. This tension is still present today, and even if friluftsliv can be subsumed under a broad concept of ‘sport’, it is in many ways different from the mainstream sport. However, friluftsliv comes in different versions and in the following we will try to show how different friluftsliv versions can represent different value structures and thus different existential dimensions.

Friluftsliv as belonging

The history of Norwegian friluftsliv builds on two different traditions, which can illustrate two different ways of belonging (Breivik Citation1978; Nedrelid Citation1991). One tradition is the countryside friluftsliv, which has roots in old farming activities and was especially developed in the 19th century to provide extra food in scarce situations. The countryside friluftsliv included activities such as harvesting, fishing, hunting, collecting berries, mushrooms, eggs and other edible materials. These activities were typically practised in groups and thus with a strong and deep communal aspect of belonging to a local collective and to nature. For many farmers, the extra income from this side-activity helped them survive in tough times and under hard conditions. This ‘extra’ was also a source of joy since getting up in the mountains, into the woods or out on the sea, meant freedom, enjoyment and the experience of nature’s greatness and stillness. The farmers’ form of ‘friluftsliv’ (which was not called ‘friluftsliv’ by themselves) was thus a combination of using available resources in nature and at the same time enjoying what mother nature had to offer of new experiences and deep feelings. It was arguably a practical and to some extent instrumental form of friluftsliv (c.f. the mode of having), which also involved an enjoyable non-instrumental aspect (c.f. the mode of being). Still, the most central aspect for farmers and countryside people seems to be the communitarian belonging to nature. Friluftsliv was a way of connecting with nature and getting a feeling of belonging to nature together with other hunters, fishers and harvesters (Breivik Citation1978; Nedrelid Citation1991). This old tradition is still alive, not as a necessity for poor farmers in the countryside, but as a possibility for leisure-time enjoyment of nature.

The other way of belonging is related to a city-tradition in friluftsliv (Gurholt Citation2008). In the 1830s the first pioneers from the cities ventured into the mountains of Jotunheimen. Scientists, especially botanists, biologists and geologists were first, followed by upper-class people, painters and poets, who entered the mountains as part of the national and romantic movement that swept over Norway from the 1840s onwards. These pioneers called themselves tourists in the original sense of the word, indicating how nature became a site for exciting journeys and possibilities for experiencing the greatness and beauty of nature. This attitude to nature laid the ground for The Norwegian Tourist Association (now called The Norwegian Trekking Association) founded in 1868 to build huts and marking trails to help people get access to the mountains and be able to experience the challenges and attractions of mountain landscapes. Similarly, the woods and the seascapes became areas for friluftsliv, where belonging meant an emotional belonging to nature (c.f. place experience), but also becoming part of the growing group of nature-lovers from the cities. These nature-lovers increasingly came together to form local trekking clubs and associations and belonging to these became, and still is, an important part of many Norwegian’s identity. Thus, besides feeling at home in nature, there are two meanings of belonging the city-tradition of friluftsliv. First, one is a member of the local and the nationwide friluftsliv associations, especially The Norwegian Trekking Association. Second, one is part of the communitarian fellowship of nature-lovers with strong emotional bonds to natural environments of various kinds.

Friluftsliv as being

In 1962 Rachel Carson published The silent spring and the following two decades ‘ecology’ became a keyword for some parts of the friluftsliv movement. The Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess (Citation1990) distinguished between ‘deep’ and ‘shallow’ ecology and developed his nature philosophy called ‘ecosophy’ inspired by Spinoza and the new ecological science. Arne Naess and others advocated a need for a new way of living and a society, including friluftsliv, built on deep ecological principles. The slogan was ‘richness in ends, simplicity in means’, and friluftsliv was seen as a way back to nature, a way back to the original home. Friluftsliv became a way of exemplifying an ecologically sound lifestyle with equipment made of renewable resources, eco-friendly forms of travelling, modesty in lifestyle and clothing, and so on. Rather than appropriating or using nature instrumentally to satisfy egoistic goals (c.f. the having attitude), people should be in it and see friluftsliv as an end in itself.

The deep ecological friluftsliv attracted many young people, but it never became a mass movement. It was in some ways too extreme in its demands on deep ecological commitment and simple personal lifestyle. It inspired, however, many to think critically about friluftsliv as more important than just a recreational leisure pursuit. It has had some interesting consequences in pedagogical contexts. Deep ecological friluftsliv was central in the Norwegian Mountain School established by Nils Faarlund in 1968 and also in the Friluftsliv programs at Norwegian School of Sport Sciences. This version of friluftsliv has, thus, had some considerable communal aspects and involved shared ideals and values, so it could represent an attitude of belonging. We believe, however, that this version of friluftsliv is better suited to illustrate the mode of being, as it insists on an active and critical engagement in deep ecological friluftsliv. It promotes friluftsliv as a way of experiencing and being in nature.

Friluftsliv as having

After the development of ecological consciousness in the 1960s and 1970s friluftsliv received new impulses in the 1980s by the new lifestyle sports. These sports developed outside traditional sports by a combined entrepreneurial effort from practitioners, equipment producers and media people. It also involved the use of video and internet resources. The lifestyle sports consisted mainly of several, partly new, outdoor activities such as board sports (surfboards, skateboards, snowboards, skyboards), water sports (white water kayaking, rafting), ski sports (mountain skiing, freestyle, extreme skiing) new forms of climbing (bouldering, in-door, soloing, big wall, ice-climbing), new forms of skydiving, base jumping, paragliding and kiting (on water and snow). The sports went under different names, for example, ‘action sport’, ‘adventure sport’, ‘risk sport’, ‘extreme sport’, ‘lifestyle sport’. They were in Norway, as in many Western countries, dominated by white middle-class males and often included a tendency to build subcultures based on specific values, lifestyles, clothes and slang (Breivik Citation2010; Wheaton Citation2004).

Some of these sports ended up as competitive sports and came under the umbrellas of sports organisations and the Olympic movement, but some remained outside. In Norway, many young people looked upon these sports as a new and modern form of friluftsliv (Green, Thurston, and Vaage Citation2015). Many traditional friluftsliv practitioners would not accept these modern activities as friluftsliv since they often included competitiveness, expensive equipment and focus on performance more than on deep experiences of nature. The natural environment often functioned as an arena for a display of advanced performance skills. The adherents of the new modern friluftsliv admitted a certain focus on skills and performance but maintained that the experience of the natural environment and the closeness to wilderness were also important elements. The modern friluftsliv made it possible to experience nature not only in its soft and slow forms, as in traditional friluftsliv, but in more difficult and riskier versions. These people sought intense experiences and had a willingness to take chances. By pushing the borders and increasing their performances, they also added status to their life portfolio. By an attitude of adding experiences and performances to their biography bank, they arguably exemplify the mode of having. Among these performers, there is also a continuous search for the best and most expensive equipment and thus an attitude of appropriation and acquisition.

This focus on acquisition may, however, be unfair as a general characteristic, since for many friluftsliv-minded lifestyle athletes the goal was not to log performances in the biography bank but to develop a lifestyle that realised deeper personal goals rather than external performance feats. We must, therefore, underline that while the attitude of having may exemplify some parts of the risky lifestyle version of friluftsliv, this form of friluftsliv also include persons that realise deep personal goals that exemplify the attitude of being. The building of cultural identity and social solidarity in a subcultural group of performers may also exemplify the attitude of belonging. The same complexity of attitudes may also exist in the earlier discussed city- and countryside type of friluftsliv and the ecological friluftsliv. Nevertheless, we believe that we have illustrated, on a general level, how the existential modes of being, having and belonging have been central to the different versions of friluftsliv.

Football in Norway

Football also has a long tradition in Norwegian society, but in contrast to friluftsliv, it has developed in ways that are similar to most other Western countries. The first club in Norway, Christiania Football club, was founded in 1885 by two men, Salvesen and Dahl, who had discovered the game as they studied in England and Scotland (Halvorsen Citation1947). The Norwegian Football Association (NFF) was founded in 1902, and since then the sport has grown to become the largest organised sport in Norway with around 374.000 registered players in 2018 and a vast number of followers.

Football as being

Football played with an emphasis on being implies a focus on the intrinsic and experiential values of the game. Participants here play for the joy of the game. They focus, for example, on experiencing the flow of the game, the thrill of dribbling and feinting, the rhythm of passing, and the excitement of creating new configurations on the field. Another aspect is to transcend and forget oneself and ‘get lost’ in the back-and-forth movements of the game.

This dimension can, for example, be prevalent when participants focus on the play aspect of football (Feezell Citation2010). However, emphasising the experiential and intrinsic value can also relate to the enjoyment of the sweet tension caused by the uncertainty of the outcome of competition (Fraleigh Citation1984). To be fun, it is crucial that participants in football at any level play to win, but rather than focusing on the outcome of the contest, an attitude related being implies a focus on the competitive process and the captivating challenges that can be part of this.

These experiential aspects of football are prevalent in more informal ways of playing. ‘Løkkefotball’ is a typical Norwegian term for an informal way of organising football among friends and locals. It requires only a ball, while other forms of equipment such as standard goals or football boots are irrelevant to the practice. However, the attitude of being is far from restricted to such informal ways of playing the game. Participants in the organised version of football, even at elite level, can also value the bodily experiences, expressions and challenges related to being in the game (Aggerholm, Jespersen, and Tore Ronglan Citation2011; Aggerholm Citation2013).

Football as having

Football played with a focus on having involves an emphasis on more instrumental values. These can relate to the competitive achievements in elite football or, in general, football played with a focus on competition, selection and winning (Gaffney Citation2015). Here, the acquisition of skills and improvement of performance to overcome resistance and gain superiority over opponents would be central to participation. This focus has historically dominated the ways of organising and engaging in football in Norway, and organised football arguably socialises many young people in Norway into values related to competition and winning.

Apart from a focus on competitive outcomes, the having attitude can also relate to social benefits. For example, young players may engage in sport with a dream of becoming a professional player at some point and, in general, being good at playing football often has a positive impact on social status and recognition. We can also relate the dimension of having to values of the governing bodies. Football is to a still more considerable extent used as a tool for social development for homeless and excluded people, and also as a means to facilitate the integration of newcomers to the Norwegian society (see Walseth Citation2016). These aims tend to be organised as project-based initiatives that target specific groups in the population. Also, other ways of engaging in, and organising, football have recently seen the light of day. For example, ‘football fitness’ has become popular, especially among middle-aged and elderly men. These developments reveal an instrumental attitude to the activity, where the objective body is exercised for the sake of health benefits extrinsic to the activity. Again, this does not exclude having fun and enjoying the game, but it describes a more instrumental mode of engaging in the activity.

Football as belonging

Football played with an emphasis on belonging is prevalent when participants value the social and communitarian aspects of the game, especially being part of a group, a team or a club (Elias and Dunning Citation1966). For example, playing with good friends or belonging to the club of a local community are central social values here. Also, participants who emphasise belonging would focus on broader aspects of participation, which includes the social life that governs games and practice.

The organisation of football in Norway is unique when compared to especially North American traditions (see Tuastad Citation2019). There are larger clubs where the geographic and traditional aspects of belonging are hardly visible anymore (market values and branding strategies replace them). However, the vast majority of football played in Norway is organised and conducted in clubs run as associations. These are driven mostly by voluntary engagement of people in the local community (Ibsen and Seippel Citation2010; Seippel Citation2010). As part of this, most coaches in youth football are parents or other volunteers who engage in coaching and various other duties in the club. These clubs often play a central role in communities and incarnate various local traditions and values. Being the largest sport in Norway, playing football is a popular way of taking part in one’s local community.

There are various football leagues where participants are grouped predominantly by classification criteria related to skill level, age and gender. Because of this, people from different social classes and with different ethnic backgrounds gather around the activity of playing football, which can, therefore, facilitate a sense of belonging as it contributes as a kind of ‘social glue’ in the Norwegian society with great integrative potential. However, there are also cases where a sense of belonging relates to other things. Apart from the geographical aspects of clubs and associations,’ groupings have historically also been rooted in various forms of common interests, a shared ethos or mutual dependency. Examples of this are religious clubs (KFUM and KFUK) and associations organised by social class (in particular workers). Today, we also see football organised by minority groups, for example Muslim organisations, which are rooted in ethnic and religious bonds between participants (Walseth Citation2016). In contemporary society, company sport is also a dominant way of organising football competition. Here, employees from different companies compete in corporate leagues, whereby participants can experience a sense of belonging through strengthened bonds between colleagues.

Discussion

To discuss our analysis, we first consider how the existential dimensions may relate and intertwine in practice, and after that, we highlight some weaknesses and strengths of our framework.

Regarding the distinction between being and having they often merge in sport. Sartre (Citation2003, 581) noticed that ‘it is seldom that play is pure of all appropriative tendency’ and his famous discussion of being and having in the activity of skiing illustrated the difficulties of distinguishing them. Since then, the relation between play and sport, and between play and work, has been widely debated in the philosophy of sport where it is often framed as a discussion of intrinsic and extrinsic values, or internal and external goods. In the actual practice of sport in society, there are interactions, processes, and interchanges that blur the distinction. Therefore, as McNamee (Citation1995) has argued, it might be more valuable here to focus on mixed goods, rather than either-or alternatives. Something may be of intrinsic value and at the same time of extrinsic value. Playing tennis may be valuable in itself and also for some other purpose, like health, money, status and prestige. The extrinsic value may be part of one’s reason, say to play tennis: one plays tennis because it is fun but also for improving health. Also, the extrinsic value may be a consequence, without having intended the consequence: one plays tennis just for fun, but as an unintended consequence gets the benefit of improving health.

Regarding the distinction between belonging and having it could be argued that in countries such as Norway, where nature is an inherent part of national culture, there is a fine line between belonging to nature and belonging to a nation: belonging to nature is to belong to Norway. In such cases belonging and having arguably intertwine, and we may see it as an instrumental relation where belonging to nature appears as a means to belong to the community. The same may be the case when participation in certain sports is a way of belonging to a particular segment or group. For example, in many countries playing golf is exclusive and considered an upper-class activity because of expensive equipment and member fees, and the time-consuming nature of the activity. In such cases, belonging to the higher social classes requires that participants can acquire certain kinds of equipment and invest a sufficient amount of time. We can also interpret the example where football is used as a means for facilitating integration of newcomers in society as a case where having and belonging intertwine. The same might be the case for many performance-oriented activities where, as we discussed earlier, the two existential modes of engagement may also intertwine in cases where the building of cultural identity and social solidarity in a group of performers express values related to belonging.

Regarding the distinction between being and belonging, it is also blurred in many cases. We can see belonging as a prerequisite for, or at least a fundamental aspect of, being. For example, feeling at home in one’s club, sensing coherence in a team or experiencing to be in the right place when tracking can allow participants to emerge in the activities and be one with nature or self-forgetful when playing a game. This primacy of belonging would be in line with Bollnow’s argument that dwelling has primacy over intentionality, and also arguments from phenomenological geography that our ways of inhabiting places constitute our experience and identity. On the other hand, we can also see being as a prerequisite for belonging in the sense that deep involvement in, and enjoyment of, one’s activity is essential for dwelling in the activity and committing oneself in a prolonged engagement.

We might see these tensions and ambiguities in practice as a weakness of our framework. However, the fact that the dimensions are related in various ways and that it can be difficult to distinguish between them in practice doesn’t render the analytical distinctions invalid. On the contrary, the distinctions between fundamental ways of engaging in sport enable us to understand and discuss how they relate and intertwined in practice. From an analytical stance, the dimensions are distinct and separable. This, however, does not imply that we see the dimensions as exclusive in practice. As mentioned earlier, we see their prevalence in practice as a matter of degree rather than either-or. Therefore, engaging one mode would not exclude engaging in another mode at the same time.

Another aspect we want to clarify is that the prevalence of existential dimensions is not deducible from the specific form of activity and its organisation. The empirically based value structure derived from the data concerning participation in sport shows that on an average level there is a correlation between individual values and participation in certain forms of sporting activities. So, values do seem to influence the ways of engagement in sport, but the existential mode of engagement also depends on the participants’ attitude to their practice. Therefore, the same form of activity, for example playing organised football, can be experienced in many ways and with a focus on different values. On an individual level and using more qualitative methods one would naturally find a range of variations and exceptions from our generalised analytical framework and our examples of ways of engaging in sport (some modern materialists value belonging to a particular club, and some traditional idealists play football to exercise). There are exceptions, but there are also observable patterns of value structures and fundamental modes of engagement. By clarifying and analysing these structures and modes, we hope our analysis can contribute to qualifying discussions about the ambiguities and tensions, to better understand how the exceptions differ from the common.

Therefore, to sum up we believe that our account of three fundamental existential dimensions is solid, as it is based on correlations in substantial empirical data and rooted in existential philosophy. As analytical distinctions, we think they can serve as a strong theoretical framework, which can help to clarify and explicate common ways of engaging in sport. As such, we hope that it can contribute with valuable analytical grounds for navigating in the variety of ways that people engage in sport, and we believe it holds the potential to provide a philosophical background for further empirical studies, qualitative and quantitative, of participation in sport.

Conclusion

In this article, we have presented an empirically based value structure that identifies key dimensions and characteristics of sports participation. Drawing on data from the Norwegian Monitor survey and combining it with philosophical reasoning, we discerned three general ways of engaging in sport: being, having and belonging. We sought to provide a philosophical clarification of the three existential dimensions and put them to use by illustrating what these ways of being engaged in sport might look like in friluftsliv and football. Though our attempts at relating the existential dimensions and ways of organising activities are to some extent provisory, we hope that they can serve as examples of different ways of engaging in activities, which depend on both the social values of society and individual modes of engagement. The empirical data we draw on, and the examples we use, are taken from a Norwegian context. However, we see the philosophical perspectives as generalisable and applicable to other cultural contexts. To be sure, sport carries very different individual and social values in different parts of the world, but there are at the same time some common denominators. The distinction between being, having and belonging may function to explicate such commonalities, and thus provide a useful analytical framework for future studies into value structures and participation in sport.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aggerholm, K. 2013. “Express Yourself: The Value of Theatricality in Soccer.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 40 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1080/00948705.2013.785414.

- Aggerholm, K., E. Jespersen, and L. Tore Ronglan. 2011. “Falling for the Feint – an Existential Investigation of a Creative Performance in High-Level Football.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 5 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1080/17511321.2011.602589.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality. A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Penguin Books.

- Bollnow, O. F. 2011. Human Space. Translated by C. Shuttleworth. London: Hyphen Press. (Orig. 1963)

- Breivik, G. 1978. “To Tradisjoner i Norsk Friluftsliv [Two Traditions in Norwegian Friluftsliv].” In Friluftsliv Fra Fridtjof Nansen Til Våre Dager, edited by G. Breivik and H. Løvmo, 7–16. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Breivik, G. 1998. “Sport in High Modernity: Sport as a Carrier of Social Values.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 25 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1080/00948705.1998.9714572.

- Breivik, G. 2010. “Trends in Adventure Sports in a Post-Modern Society.” Sport in Society 13 (2): 260–273. doi:10.1080/17430430903522970.

- Breivik, G., and O. Hellevik. 2014. “More Active and Less Fit: changes in Physical Activity in the Adult Norwegian Population from 1985 to 2011.” Sport in Society 17 (2): 157–175. doi:10.1080/17430437.2013.790898.

- Carson, R. 1962. The Silent Spring. Boston, MA: Mariner Books.

- Elias, N., and E. Dunning. 1966. “Dynamics of Group Sports with Special Reference to Football.” The British Journal of Sociology 17 (4): 388–402. doi:10.2307/589186.

- Feezell, R. 2010. “A Pluralist Conception of Play.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 37 (2): 147–165. doi:10.1080/00948705.2010.9714773.

- Fraleigh, W. P. 1984. Right Actions in Sport. Ethics for Contestants. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Fridberg, T. 2010. “Sport and Exercise in Denmark, Scandinavia and Europe.” Sport in Society 13 (4): 583–592. doi:10.1080/17430431003616225.

- Fromm, E. 2008. To Have or to Be? New York: Continuum. (Orig. 1976)

- Gaffney, P. 2015. “Competition.” In Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Sport, edited by M. McNamee and W. J. Morgan, 287–299. London and New York: Routledge.

- Green, K., M. Thurston, and O. Vaage. 2015. “Isn’t It Good, Norwegian Wood? Lifestyle and Adventure Sports Participation among Norwegian Youth.” Leisure Studies 34 (5): 529–546. doi:10.1080/02614367.2014.938771.

- Gurholt, K. P. 2008. “Norwegian Friluftsliv as Bildung: A Critical Review.” In Other Ways of Learning, edited by P. Becker and J. Schirp, 131–154. Marburg: BSJ Marburg

- Halvorsen, A., ed. 1947. Norges Fotball Leksikon [The Norwegian Encyclopedia of Football]. Oslo: Prent forlag.

- Heidegger, M. 1993. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” In Basic Writings, edited by D. F. Krell, 343–363. San Francisco, CA: Harper Collins Publishers. doi:10.1007/BF02479963.

- Hellevik, O. 2008. Jakten på Den Norske Lykken [The Pursuit of the Norwegian Happiness]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Ibsen, B., and Ø. Seippel. 2010. “Voluntary Organized Sport in Denmark and Norway.” Sport in Society 13 (4): 593–608. doi:10.1080/17430431003616266.

- Kretchmar, S. 2015. “Pluralistic Internalism.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 42 (1): 83–100. doi:10.1080/00948705.2014.911101.

- McLean, J., and S. Hamm. 2008. “Values and Sport Participation: Comparing Participant Groups, Age, and Gender.” Journal of Sport Behavior 31 (4): 352–367.

- Marcel, G. 1949. Being and Having. Glasgow: The University Press.

- McFee, G. 2004. Sport, Rules and Values: Philosophical Investigations into the Nature of Sport. London: Routledge.

- McNamee, M. 1995. “Sporting Practices, Institutions, and Virtues: A Critique and a Restatement.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 22 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1080/00948705.1995.9714516.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 2012. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by D. A. Landes. London and New York: Routledge. (Orig. 1945)

- Naess, A. 1990. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nedrelid, T. 1991. “Use of Nature as a Norwegian Characteristic.” Ethnologia Scandinavica: a Journal for Nordic Ethnology 21: 19–33.

- Pran, K. R., and J. Spilling. 2018. Fysisk Aktivitet og Idrett i Norge. Norsk Monitor 2017/18. Rapport Utarbeidet for Norges Idrettsforbund og Olympiske og Paralympiske Komité [Physical Activity and Sport in Norway. Norwegian Monitor 2017/18. Report Prepared for the the Norwegian Confederation of Sports and Olympic and Paralympic Committee]. Oslo: IPSOS.

- Reed, P., and D. Rothenberg. (Eds.). 1993. Wisdom in the Open Air: The Norwegian Roots of Deep Ecology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion Limited.

- Sartre, J.-P. 2003. Being and Nothingness. An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translated by H. E. Barnes. London: Routledge. (Orig. 1943)

- Sartre, J.-P. 2004. Critique of Dialectical Reason. Volume One. Theory of Practical Ensenbles. Translated by A. Sheridan-Smith. London: Verso. (Orig. 1960)

- Seamon, D., and Mugerauer, R., eds. 1985. Dwelling, Place and Environment. Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Seippel, Ø. 2006. “The Meanings of Sport: Fun, Health, Beauty or Community.” Sport in Society 9 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1080/17430430500355790.

- Seippel, Ø. 2010. “Professionals and Volunteers: On the Future of a Scandinavian Sport Model.” Sport in Society 13 (2): 199–211. doi:10.1080/17430430903522921.

- Tuastad, S. 2019. “The Scandinavian Sport Model: Myths and Realities. Norwegian Football as a Case Study.” Soccer & Society 20 (2): 341–359. doi:10.1080/14660970.2017.1323738.

- Walseth, K. 2016. “Sport within Muslim Organizations in Norway: Ethnic Segregated Activities as Arena for Integration.” Leisure Studies 35 (1): 78–99. doi:10.1080/02614367.2015.1055293.

- Wheaton, B. 2004. “Introduction. Mapping the Lifestyle Sport-Scape.” In Understanding Lifestyle Sport: Consumption, Identity and Difference, edited by B. Wheaton, 1–28. London and New York: Routledge.