ABSTRACT

This paper pertains to a project which began with an academic research team being recruited by a YMCA management team to help understand how to retain forced migrant youth in YMCA sport programs. Owing to experience working with diverse cultural groups through praxis-oriented approaches, the project team recognized a need to develop an understanding of how forced migrant youth wished to engage in sport where the onus was not exclusively theirs to shoulder the navigation of cultural differences. We present a critical analysis, interspersed with creative non-fiction accounts, to show how forced migrant youth, their families, YMCA settlement staff members, and an academic research team collaborated to increase awareness of the diverse cultural ‘realities’ present in our community and social inequalities faced by forced migrant youth. We conclude with lessons related to community capacity building and the development of contextually relevant sport programs.

One in every 97 people was living forcibly displaced from their home by the end of 2019 due to persecution, conflict, and/or violence (UNHCR Citation2020). Individuals who cross their country’s borders seeking asylum (i.e., asylum seekers) must provide sufficient proof of fear of persecution to be afforded the legal protection and material assistance granted to ‘recognised refugees’ (UNHCR Citation2020). For many asylum seekers and refugees (from here on referred to as forced migrants) returning home is not an option in the short-term. Hence, they seek to be permanently re-settled in a third country (UNHCR Citation2020). The number of individuals seeking asylum in Canada has steadily increased over the past five years (i.e., 9 999 in 2014 to 87 270 in 2019), while at the same time Canada has consistently been among world leaders in resettling refugees (IRB Citation2020; UNHCR Citation2020). The increasing number of forced migrants has resulted in the tension that comes about as culturally dissimilar individuals come into constant contact with one another. The process of, including resistance to, cultural and psychological change individuals undergo when in constant contact with members of a culturally dissimilar community is known as acculturation (Berry Citation2017). Psychological integration, an acculturative process through which individuals maintain connections to their home culture while engaging in daily interactions with culturally dissimilar others, has been posited as an ‘optimal’ form of acculturation by researchers using nomothetic-deductive research approaches (Berry Citation2017). However, more often than not, the onus of undergoing a process of change is shouldered by newcomers who are expected to adapt unilaterally to the host community (i.e., assimilation) (Agergaard Citation2018; Jeanes, O’ Connor, and Alfrey Citation2015). The subsuming of assimilation under the guise of integration can be stressful and lonely for newcomers and compound the negative impact on mental health forced migrants encounter due to traumatic incidents faced during journeys to safety (Berry Citation2017; George Citation2012). The compounded impact can leave forced migrants with feelings of exclusion, isolation, anger, uncertainty, anxiety, and potential prolonged mental health challenges such as depression and/or post-traumatic stress syndrome (George Citation2012; Steel et al. Citation2006).

Sport is often portrayed as a method through which to support the integration of newcomers (e.g., Sport Canada Citation2012). Participating in sport can help newcomers improve their physical and mental well-being, develop connections with others, and learn relevant life skills (Ley, Barrio, and Koch Citation2018; Whitley, Massey, and Wilkison Citation2018). Sport can also help forced migrants feel in control of defining who they are and simplify interaction with culturally dissimilar others (Nathan et al. Citation2013; Stone Citation2018; Woodhouse and Conricode Citation2017). However, without critically examining how individuals engage in sport and who determines what forms of sport engagement are prioritized, the complex social and cultural issues present in sport may be ignored resulting in the marginalization of forced migrants who view engagement in sport differently than what is accepted as normal in the host community (Jeanes, O’ Connor, and Alfrey Citation2015; Spaaij Citation2015). An important first step is acknowledging that sport can also be a context in which broader societal issues of racism (e.g., Farquharson et al. Citation2018), discrimination (e.g., Mauro Citation2013), and a lack of understanding for cultural differences (e.g., Jeanes, O’ Connor, and Alfrey Citation2015) manifest. Recognition of the complexity of intercultural interaction in sport has led to researchers exploring the factors that help or hinder the development of sport contexts capable of producing positive social outcomes (e.g., Dukic, McDonald, and Spaaij Citation2017).

We (the authors) remain skeptical universal factors (i.e., applicable to ALL sport contexts) exist. We concur with sport morality researchers’ (e.g., Shields and Bredemeier Citation2007) views of sport environments as highly idiosyncratic and socially rich whose ‘reality’ is produced by the individuals present in them. The philosophical underpinning of our work is rooted in ontological cultural relativism and epistemological social constructionism. We believe understanding how individuals continuously engage in the co-construction of multiple, localized realities enables us to also understand how change may be brought to our ‘realities’ through the introduction of new stories (Gergen and Gergen Citation2008). Wishing to bring change to the realities present in the community we (the authors) are part of a research team comprised of YMCA community settlement staff, forced migrant families, and academic researchers engaged in a community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) project. Currently in year four of six, this paper is the fourth stemming from the CBPAR project. The first paper was a meta-synthesis of qualitative research related to forced migrants’ involvement in sport and provided academic team members with an opportunity to learn from previously developed knowledge (Middleton et al. Citation2020). The second (Middleton et al. Citation2021) and third paper (Middleton et al. under review) centralized the re-storying of forced migrant youths’ stories through empirical data. Having completed the knowledge generation phase, the aim in this paper is to provide a critical analysis of the continuous process required to engender a collaborative effort towards developing socially just community sport programs.

The critical analysis is underpinned by conversations and email exchanges between research team members throughout the CBPAR project which were tracked and reflected upon by me (Thierry) in a project journal. The analysis is interspersed with a number of creative non-fiction literary devices to bring forward the different voices of research team members and reveal the dynamic navigation of power differentials that occurred throughout the knowledge development process (Spaaij et al. Citation2018). By doing so the aim is to provide an authentic account of how local knowledge was centralized in the social construction of a new shared ‘reality’ (Gergen and Gergen Citation2008; Kral Citation2014). Forced migrant youths’ voices are brought into the text in two ways: (1) brief dialogic accounts of events that occurred during the data collection process when the team could meet in person, and (2) purposefully chosen quotes shared over Zoom and email that reveal how power shifted to youth during the analytical process. Youths’ anonymity is protected throughout the manuscript through the use of (forced migrant youth chosen) pseudonyms so that youth felt safe sharing personal stories (McDonald, Spaaij, and Dukic Citation2019).

Proactively shifting power in the research relationship is incumbent on academic researchers who are generally viewed as occupying positions of power in the research process. As Kwan and Walsh (Citation2018) noted, to ethically navigate power differentials between research team members, academic researchers must be aware of and address power dynamics continuously throughout the research process. Doing so includes acknowledging my (Thierry’s) role in shaping this manuscript by writing in first person. Further, reflexivity is inextricably linked to (academic) researchers shifting power as they continuously use their reflections on the unfolding of the research process to ensure future actions continue to centralize community members as the lead decision makers charting the course of the project (Schinke, Smith, and McGannon Citation2013; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). While reflexivity has become increasingly used in qualitative research texts, rarely are readers privy to the researcher’s reflective thoughts. Rather than seek to portray the CBPAR process as one of continuous equal participation (Kaukko Citation2016), the aim herein is to provide reflexive accounts of how I continuously examined my position in the research process and the subsequent impact on knowledge development (Spaaij et al. Citation2018). Three brief asides (see Lopez Citation2003), a drama literary device used to interrupt a text to provide readers (or viewers) with insight into a character’s thoughts, are used to share my personal interpretations of how intentionally or not I felt my decisions shaped the stories shared by forced migrant youth.

Introducing the CBPAR project

CBPAR projects, rooted in concerns brought forward by community members, use research methods that reflect local practises and result in project deliverables (e.g., training protocols, sport programs) that centralise local customs and are sustainable beyond the involvement of academic researchers (Schinke, Smith, and McGannon Citation2013; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). The project analysed in this paper was initiated by management staff from the YMCA of Northeastern Ontario seeking to develop improved sport programming that would support forced migrant youth resettling in the community. Having provided resettled Syrian forced migrant families with a free one year membership, YMCA managements’ desire for improved programming was borne from a realization that forced migrant families had not renewed memberships beyond the first year. YMCA management staff approached Robert, a long time YMCA supporter and academic known in the community for previous work helping a local Indigenous community develop sport programming for youth.

Setting the context

Sudbury is a city in Northeastern Ontario, a region of Canada that has had a recent influx of forced migrants, primarily from Syria and Western Africa. The YMCA of Northeastern Ontario, a community organization tasked with providing settlement services, recorded a 144% (i.e., 171 to 418) increase in the number of forced migrants they provided services to from 2018 to 2019. The majority of the host community have European ethno-cultural heritage backgrounds. Hence, forced migrants arriving in Sudbury do not have access to large cultural enclaves found in larger urban centres (Kumar, Seay, and Karabenick Citation2015; Statistics Canada Citation2019). Additionally, forced migrants must contend with negative portrayals of their presence in Canadian host communities (Esses, Medianu, and Lawson Citation2013). Forced migrant youth were the chosen research partners as Canadian researchers had previously found newcomer parents more likely to become involved in sport programs through children in the family (ICC Citation2014). The academic research team believed working alongside forced migrant youth would lead to youths’ family members also benefitting from sport involvement.

Project collaborators

From the outset of the project, Deborah took the lead on behalf of the YMCA in continuing to develop the project’s aim, defining inclusion criteria for forced migrant youth, and developing recruitment materials. As a life-long resident of Sudbury, Deborah’s understanding of the dominant ‘realities’ in the community and the different YMCA programs that could benefit from the co-produced knowledge were invaluable in charting the project. Deborah also recruited Bahaa, one of her staff members at the YMCA Immigrant Services office, to join the project and help recruit forced migrant families. Bahaa was forced to flee Syria, finding refuge in Jordan where he helped other Syrian asylum seekers. After five years he was sponsored by Laurentian university to resettle in Canada. Bahaa proved invaluable in helping interested forced migrant youth and their families join the research team as collaborators.

Thirty-three forced migrant youth from 15 families have become collaborators. At the outset of the project the youths’ average age was 12.6 years (range = 8 to 21 years) and average time of living in Canada was 18.6 months (range = 4 to 44 months). Youth were originally from Syria (n = 20), Nigeria (n = 8), Libya (n = 2), Chad (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), and the Bahamas (n = 1). Syrian youth had been resettled in Canada from the country where they applied for asylum, namely Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, while non-Syrian youth were at varying stages of applying for asylum in Canada after having relocated directly from their home country or indirectly by crossing the U.S.A. border.

I (Thierry), was a PhD candidate and the lead research assistant on the CBPAR project. Born in Switzerland, I grew up in Nigeria prior to moving to Canada at the age of 10, and more recently, taught physical education in Italy and completed my master’s degrees in Finland and Germany. Originally having been taught by Robert during my undergraduate education, I was invited to join the project team for my PhD. Diana is a licensed clinical social worker in addition to her faculty position. Her research has focused on the use of arts-based mindfulness activities to improve the resilience and self-concept of youth from marginalized backgrounds. Cole is a PhD student who joined the project team at later stage to assume my duties in the program delivery phase. His role was to support the launch of the co-developed staff training and youth-centered sport programs as I moved away from Sudbury after I completed my PhD.

Building relationships

The foundation of high-quality and impactful CBPAR rests on the development of relationships between academic and community collaborators grounded in respect, reciprocity, and trust (Gergen and Gergen Citation2008; Kral Citation2014; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). Developing relationships can be a ‘messy’ process but is facilitated if researchers work alongside community partners with humility and openness to engage in new ways of seeing the world (Cook Citation2009; Schinke et al. Citation2016). From the outset, relationships were developed through formal meetings, shared meals, informal coffee times, unplanned encounters in the community, and intermittent messages via a collaboratively created Facebook group. A crucial component to the development of relationships between academic and YMCA team members and forced migrant families came from Bahaa’s suggestion to visit families’ homes rather than hold formal recruiting events. Initial introduction meetings were held in each family’s home during which I, as the outsider, was introduced to the cultural values and traditions of families over shared cups of coffee, new foods, and instruction on how to speak a few words in the families’ native languages. As Bahaa explained, by sharing in food and drink with the families in their homes, I moved from being a stranger to becoming a part of forced migrant youths’ extended family.

Decolonizing knowledge development

CBPAR draws upon Indigenous scholars’ calls for researchers to move beyond academic boundaries of knowledge production in order to reverse damage done by oppressive research practices (Smith Citation2012). While decolonizing methodologies are rooted in Indigenous scholarship, they are applicable to research with individuals from marginalised backgrounds as they offer an openness to different ways of thinking about cultural norms, co-constructing knowledge, and the dissemination of findings (Land Citation2015; Smith Citation2012). The decolonization approach to knowledge development used in the CBPAR project analysed here followed Darnell and Hayhurst’s (Citation2011) lead, in that the term is not used in reference to a historical era, but rather in relation to challenging unjust social structures and supporting the self-determination of forced migrant youth in regards to the research process. Similar to Kaukko (Citation2016), the current project was developed with the belief that each forced migrant youth was an expert of her/his own story and for meaningful change to be brought to community sport programs their accounts needed to be centralised in any discussion about the impact of sport during acculturative journeys. Hence, the reflexive approach to participation in the CBPAR process on the part of academic researchers was explicitly aimed at recognising and addressing practices through which those in positions of power perpetuated disempowering research structures (Schinke et al. Citation2012). As such, the project team did not adhere to a prescriptive model; the research process was characterised by twists and turns as different ways of thinking about the world provided inspiration for developing novel pathways to bringing about change (Cook Citation2009). The following sections show the dynamic unfolding of the knowledge development process beginning with arts-based conversational interviews followed by a reflexive thematic analysis and culminating in the development of collaboratively written creative non-fiction polyphonic vignettes.

Arts-based conversational interviews

Building upon Rob and Diana’s previous use of an arts-based method to develop locally-relevant knowledge in community work with Indigenous youth (see Blodgett et al. Citation2013) and inspired by a collage of art created by youth hanging in the YMCA Immigrant Services offices, an arts-based method was used during the initial ‘get-to-know-each other’ interviews. Once again, Bahaa and I were invited by the families into their homes for these interviews which began with me asking youth to draw any images and/or symbols that meaningfully depicted personal stories related to playing sport in Canada (some of the artwork created by youth can be found at https://www.facebook.com/Activitypageforforcedimmigrantyouth). While arts-based interviews were selected by academic researchers as a method of fostering space for youth to control which stories were shared, the following two brief creative non-fiction accounts portray how youth and their families took control and shaped how the process unfolded. The accounts are portrayed in a creative non-fiction manner so readers may envision themselves sitting in the room alongside the researchers (Rolfe Citation2002).

Event 1: Art as a collective exercise

‘While you draw, Bahaa and I will also draw our stories of playing sport in Canada at the same time. Feel free to ask us questions at any time,’ I say as I hand a piece of paper to Abdo and spread out markers, pencil crayons, and crayons on the table.

‘Would you mind if my brother joined me?’ Abdo asks. As I look up I see Abdo’s younger brother staring longingly at the colouring utensils and paper.

‘Of course, I’d be happy if he did,’ I say offering a piece of paper to Abdo’s younger brother. I then looked to the other siblings, ‘Would you like to join us too?’

Interpreting event 1

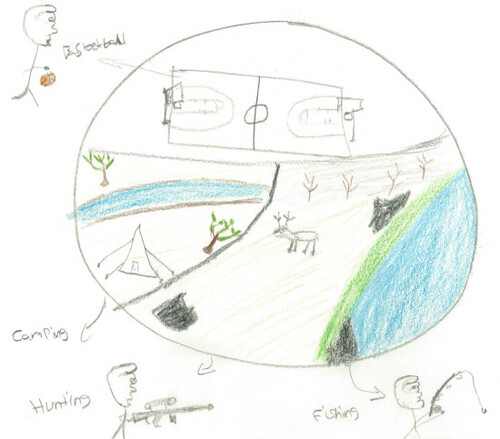

The first event reveals how youth developed an interview context that helped make them feel more comfortable. While Bahaa and I attempted to help youth feel comfortable by assuring them the artwork was solely to be used as means of self-expression and would not be analysed, as well as drawing alongside them, for many of these youth drawing alongside siblings felt most comfortable. Feeling comfortable in the interview setting can help youth feel confident directing conversation by choosing the stories they wish to tell (Sinding, Warren, and Paton Citation2014). The act of drawing in this case catalysed a shifting of power in the research relationship rather than merely becoming a data source (Leitch Citation2008; Sinding, Warren, and Paton Citation2014). For instance, one youth uncomfortable with the prospect of drawing asked if he could answer questions we wanted answered rather than partake in the arts-based exercise. After Bahaa and I explained that we did not have specific questions to ask, but rather wished to hear stories he wanted to tell us and re-iterated that the art was solely to facilitate the storytelling process, the youth decided to draw alongside his brothers. Following the drawing period, the youth was eager to share his story first and proceeded to direct the entire conversation based around his drawing which touched on the different activities he enjoyed engaging in and how engaging in the activities differed from his home country to his host community (see ). Using arts-based methods with youth can also help them share stories that may have previously been ‘unsayable’ (Leitch Citation2008; Sinding, Warren, and Paton Citation2014). Some of these unsayable stories may have been related to traumatic incidents encountered during their journey to safety. For youth who wished to share trauma-related stories, using an arts-based method provided an opportunity to represent these stories as fictional and/or in the past within an ethically safe context (Leitch Citation2008).

Event 2: the freedom to draw what you want

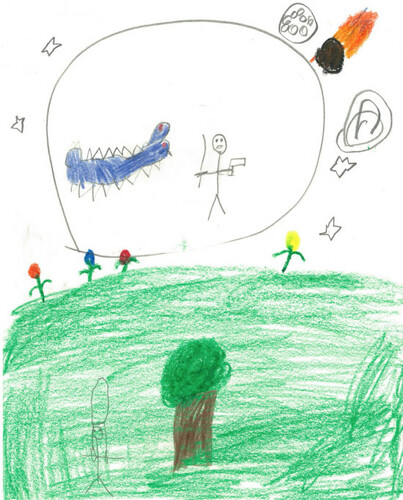

‘Finished!’ Exclaims Deji as he sets down his marker and looks at his drawing. I look up at Deji and then down at his drawing and have to stifle a reaction. On the paper is the drawing of a man with weapons, a strange looking creature, and what looks like a meteor heading for Earth (see ). Interested to hear Deji’s story in relation to his picture I ask, ‘Wow that is cool! Would you mind telling me about your picture?’

Deji launches into telling me all about the book they are reading in school and how he can’t wait to finish it. After about five minutes Deji’s mum softly lays her arm around Deji’s shoulder and says, ‘Deji, why don’t you tell Thierry about the football game you have tomorrow? He would probably be interested to hear about your team.’ Without hesitation Deji launches into a story about his team and his excitement for the upcoming game.

Interpreting event 2

The second event reveals the precariousness that comes with CBPAR; when co-researchers take control of deciding what knowledge is developed they may share stories which differ greatly to those expected by academic researchers (Darnell and Hayhurst Citation2011; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). Perhaps more common were instances when youth shared stories related to their desire for employment. An important story for one youth was related to the gardening company he had self-started during his first summer in his host community. Rather than talk about sports he spoke about how he had begun the company to continue to help financially support his family just as he had in the country they had first fled to. As Darnell and Hayhurst (Citation2011) noted, if community members are more concerned with employment than sport, then truly decolonizing the research process may mean moving beyond a focus on sport. However, many youth also lamented that many employment opportunities did not provide the same intercultural interaction as they had within sport, raising the spectre of examining the intersection of sport with other social fields in youths’ lives (Spaaij Citation2009). Shifting control over what stories were focused on in the storytelling relationship to youth was a continuing priority for the academic research team.

Thierry’s Reflexive Aside: As an academic researcher, listening to stories youth wished to share was at times uncomfortable, particularly stories related to traumatic events in their lives as I feared causing re-traumatization through my questioning. During a debrief session with Diana, she assured me that it was ‘ok to be uncomfortable’ and that if youth were willing to share trauma-related stories my questioning would not be the cause of re-traumatization. My realization in this case was that my uncomfortableness was not solely related to youths’ well-being, but also my own difficulty with ‘putting a face’ to the stories I had read/heard through media accounts of events occurring in war-torn areas.

Reflexive thematic analysis

Conducting a reflexive thematic analysis (see Braun and Clarke Citation2019) was a continuation of the knowledge development process as the research team worked together to develop stories forced migrant youth deemed important to share with host community individuals. Braun and Clarke (Citation2019, 591) noted a reflexive thematic analysis is not about “finding the ‘truth’ that is either ‘out there’ and findable from, or buried deep within, the data” but about interpreting and creating context-bound stories that hold meaning to storyteller and story listener. Further, the aim was to share stories that would bring about change and the development of socially just conditions for all youth in community sport programs (Land Citation2015). With forced migrant youth being experts of their stories, it was incumbent on academic and YMCA research team members to become immersed in youths’ stories – especially academic team members who’s analytical and writing skills would be relied upon to bring together forced migrant youths’ stories into resonating creative non-fiction stories (see Middleton et al. Citation2021). Immersion into youths’ stories began during the arts-based interviews and continued through a recursive process of reading and coding interview transcripts during which interesting common features across stories were noted. Discussions occurred amongst all research collaborators related to the development and subsequent organization of codes into sets of interrelated themes that would tell compelling and important stories.

Thierry’s Reflexive Aside: There were many points during the analysis process where I had to assess why I found certain aspects of stories interesting such as the journeys the families had taken to resettle in Sudbury. The difference in youths’ journeys as compared to mine piqued my interest, as my journey had left me without strong ties to one specific country, but rather to multiple. Despite having been forced to flee their homes, many youths remained very proud of their home culture as shown by their desire to invite me into their homes to share their stories with me. Being invited to learn about their culture in such a personal fashion made me realize how limited I would have been trying to re-tell youths’ stories without their collaboration. While I understood the theoretical importance of decolonization, building relationships with youth and their families led to a greater appreciation of how shifting power and control in the research process to community members can lead to the development of locally relevant knowledge.

Co-developing creative non-fiction polyphonic vignettes

The analysis continued through the development of creative non-fiction stories using the thematic frameworks as guides. Reflecting the co-authorship of the stories, polyphonic vignettes were developed; short stories that gave agency to multiple voices throughout the writing process and portrayed the complex, multiple, and diverse meanings related to forced migrant youths’ accounts of the role sport played in their lives, including during their journeys to Canada (Letiche Citation2010). Developing polyphonic vignettes was also an ethical decision so as to highlight differences, as well as similarities, in forced migrant youths’ stories and not further contribute to grouping forced migrant youth as the ‘other’ under one label (Kwan and Walsh Citation2018; Land Citation2015). Using the youths’ words drawn from the transcripts of the arts-based interviews, the stories feature composite characters that resemble forced migrant youth research team members yet adequately protect anonymity. Stories related to male youth collaborators featured two Syrian characters representing the 17 male Syrian youth collaborators and one non-Syrian character representing the five male non-Syrian youth collaborators. Stories related to female youth collaborators had yet to be drafted at the writing of this paper but will also include multiple characters.

I composed the initial draft of male youths’ stories. I took creative license in determining how content drawn from the transcripts was rearranged into a compelling and coherent story. Once completed, the stories were shared with forced migrant male youth collaborators and family members, YMCA, and academic team members whose feedback was provided via email or over Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions. Two pieces of feedback received from youth show the shifting of power to youth during the analysis process. The first piece of feedback was shared over a Zoom call with one family during the analysis of the first story to be disseminated to the community. Having read the first draft of the story as a family, the eldest youth, Tarek, provided the following feedback:

We think the story is good, but it’s missing some of our culture. My dad especially wanted to comment on your description of how we kids stood up from the couch when you arrived at our home and then sat on the floor so that you could sit on the couch. You didn’t explain that this is our cultural custom for any adult that comes into a room. We think you need to explain this so that Canadians understand our culture. Also, your description of how we played football anywhere we could makes it sound like we didn’t have fields to play on, but that isn’t true. We did go play on football fields, it’s just that we would also play anywhere we could at any time, but the way you wrote it, I think, makes our country look poorer than it was.

This feedback from Tarek raised several points which fundamentally altered the writing of the story and shows how youth maintained control of themes centralized in the stories. Rather than the focus being on where football was played, the focus shifted to how football was played (i.e., in an informal manner) which forced migrant youth felt was a more important aspect in the storying. Further, pride in their home culture was further emphasized with the desire for underlying cultural norms behind actions to be explicitly described within the stories.

A second piece of feedback sent to me via email by another youth, Omar, provided further insight into the multiple benefits that underly a storied methodology:

I thought I had a unique childhood, but it seems that all Syrian kids had the same childhood. I can definitely relate… Especially when they touched on the way the teams are split up when they are playing football, given the amount of time it takes to split the teams, it’s VERY accurate. Also the location of the ‘field’ is very relatable because we played in any open area where we could put two rocks on each end as goal posts.

The use of composite characters to re-story seems to have provided Omar with a comforting sense that he was not alone. For youth who must tackle feeling the ‘other’ everyday, the knowledge that youth with similar life stories lived in the community can provide a connection back to their home culture and help them to feel that diverse cultural values and norms are accepted by others in the host community, which can help foster resilience and increase comfort in engaging in intercultural interaction (Keles et al. Citation2018; Berry Citation2017). Combined with connecting youth through involvement in the project, this feedback reveals how including youth as active research team members in the CBPAR process resulted in ‘action’ also occurring naturally rather than through a planned approach.

Thierry’s Reflexive Aside: I felt a great sense of responsibility in writing the initial draft of the polyphonic vignettes. While the stories were composed from collaboratively developed thematic frameworks, I understood that how I pieced together the youths’ words in a manner that conveyed the stories they wished to share would be closely scrutinised. I was not wrong. The first piece of feedback shared earlier was a turning point for me in my relationship with some of the forced migrant youth. Rather than feeling defensive, their willingness to provide critical feedback and assert control over how the manner in which the story was shared made me feel that the relationship had reached a deeper level of trust at which they felt comfortable explaining to me my cultural mis-understanding, thereby providing me with a unique and fortunate opportunity to further learn from the youth.

Conclusion

Earlier on in the CBPAR project, the author team outlined the importance of decolonization, collaboration, and praxis to engendering socially just change (see Schinke et al. Citation2018). This contribution brings a deeper understanding to how knowledge can be co-constructed through CBPAR and as such we conclude by focusing on the importance of constantly attending to the dynamic sharing of power as the research process unfolds (Kral Citation2014; Schinke, Smith, and McGannon Citation2013; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). Drawing upon the critical analysis three lessons are shared that further understanding of how CBPAR approaches, and attention to who directs the development of knowledge, can contribute to locally relevant and sustainable community sport programs.

First, we (as an author team) believe the use of storied method(ologies) provide marginalized, in this case forced migrant youth, with the space needed to share stories that can become the starting point of engendering socially just change within a community (Pratt Citation2007). The research process detailed here is one approach to supporting an environment in which forced migrant youth feel psychologically, emotionally, and culturally safe enough to take control of the storytelling relationship. Through youth taking control of the knowledge development process, the research project developed authentic and meaningful sport and non-sport specific stories that show how sport is an embedded component of youths’ lives, and yet not of more importance than other parts such as family, work, and school. Prolonged engagement through interviews and analysis of shared stories illustrates how story-telling relationships are an embedded component of the research process as the stories which get shared may change over time and place (Gergen and Gergen Citation2008).

The development of storytelling relationships also meant that, while similarities were found across stories, differences were also brought forward so as not to make any claim to a universal story that could be told to portray forced migrant youth. As Land (Citation2015) noted, grouping individuals into ‘us and them’ categories is not a neutral approach but one grounded in maintaining a status quo of which cultures are considered to be superior and inferior. Further, failing to recognize youths’ divergent stories could have resulted in some youth, whose stories were different than those found to be ‘common’, feeling marginalised in the research process (Kwan and Walsh Citation2018). Therefore, the aim was to consider the complexity inherent in the youth collaborators’ stories, and to portray the rich stories identified as important to be shared with host community members.

The second lesson we (as an author team) have learnt is the need to reconcile the aforementioned prolonged engagement with forced migrants’ transient lives. The time and effort needed to build trusting and respectful relationships has previously been discussed in relation to the constraints academic researchers face in terms of finite research timelines (Schinke, Smith, and McGannon Citation2013). However, the transient nature of forced migrants’ lives as they search for a host community in which they feel safe and hopeful for the future (see Pizzolati and Sterchele Citation2016) is another factor that must be taken into account. During the research process, contact was lost with some of the families as they moved away from the community. While there is the opportunity to recruit new youth to join the research team, such as Kidd et al. (Citation2018) have done in work with street-involved youth, there is an imperative need for visible action to take place expeditiously while still ensuring that such action reflects the needs and values of those for whom the change is meant to serve.

Finally, the aim of moving beyond academic boundaries by shifting control over the storytelling process to youth meant academic researchers and YMCA community staff members retained little control over the stories which were shared (Cook Citation2009; Smith Citation2012). As shared earlier, for some youth this meant a desire to share traumatic personal stories. Sharing stories related to difficult times in one’s life through the research process can be a form of catharsis and our author team hope that engagement in the research process helped some forced migrant youth collaborators further develop the resilience needed to cope with traumatic pasts (Papathomas and Lavalee Citation2012). However, it is important to acknowledge the difference between research and professional therapeutic services. From an ethical standpoint, academic researchers must consider the well-being and safety of those they work with. While working with forced migrant youth, academic and YMCA research team members have continued to provide youth, and their families, with numerous resources that can be accessed if professional and/or clinical assistance is required.

The sharing of personal traumatic stories during the research process also brought about a deeper appreciation for ensuring the well-being of academic and community research team members. Our author team implore academic and community researchers to also consider the impact of the research on themselves. Researchers, particularly those involved in the day-to-day interactions with community members and/or the transcription of interviews, can be subject to vicarious trauma (Parker and O’Reilly Citation2013). Openly embracing complexity, (inter-)subjectivity, and researchers positionality entails also critically analysing researchers sense of safety and emotional well-being in the research process. While each researcher’s sense of uncomfortableness will be unique, the presence of team members who encourage critical reflection and support during these times may be the epitome of what it means to have critical friends. Critical friends have been discussed as helping to foster reflexivity by encouraging reflection and exploration of alternate interpretations (see Smith and McGannon Citation2018), but our author team suggest the role be extended to include providing support and care for all research team members through regular preparation and debriefing sessions.

The critical analysis presented here has helped show how the dynamic unfolding of a CBPAR project can result in the development of locally relevant knowledge that contributes to socially-just sport programming. We (the author team) conclude by acknowledging the co-authors who are not listed in the by-line for reasons of anonymity and confidentiality, namely the forced migrant youth members of the research team. We feel fortunate to have been afforded the opportunity to listen to youths’ stories and have been inspired by youths’ resiliency and desire to contribute to the community.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agergaard, S. 2018. Rethinking Sports and Integration: Developing a Transnational Perspective on Migrants and Descendants in Sports. New York: Routledge.

- Berry, J. W. 2017. “Theories and Models of Acculturation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health, edited by S. J. Schwartz and J. B. Unger, 15–28. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Blodgett, A. T., D. Coholic, R. J. Schinke, K. R. McGannon, D. Peltier, and C. Pheasant. 2013. “Moving beyond Words: Exploring the Use of an Arts-Based Method in Aboriginal Community Sport Research.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 5 (3): 312–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2159676X.2013.796490.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Cook, T. 2009. “The Purpose of Mess in Action Research: Building Rigour through a Messy Turn.” Educational Action Research 17 (2): 277–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790902914241.

- Darnell, S. C., and L. M. C. Hayhurst. 2011. “Sport for Decolonization: Exploring a New Praxis of Sport for Development.” Progress in Development Studies 11 (3): 183–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100301.

- Dukic, D., B. McDonald, and R. Spaaij. 2017. “Being Able to Play: Experiences of Social Inclusion and Exclusion within a Football Team of People Seeking Asylum.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 101–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.892.

- Esses, V. M., S. Medianu, and A. S. Lawson. 2013. “Uncertainty, Threat, and the Role of the Media in Promoting the Dehumanization of Immigrants and Refugees.” Journal of Social Issues 69 (3): 518–535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12027.

- Farquharson, K., R. Spaaij, S. Gorman, D. Lusher, and R. Jeanes. 2018. “Managing Racism on the Field in Australian Junior Sport.” In Relating Worlds of Racism: Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European Whiteness, edited by P. Essed, K. Farquharson, K. Pillay, and E. J. White, 166–188. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- George, M. 2012. “Migration Traumatic Experiences and Refugee Distress: Implications for Social Work Practice.” Clinical Social Work Journal 40 (4): 429–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-012-0397-y.

- Gergen, K. J., and M. M. Gergen. 2008. “Social Construction and Research as Action.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. 2nd ed., edited by P. Reason and H. Bradbury, 158–171. London: SAGE.

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB). 2020. “Refugee Protection Claims (New System) Statistics.” Accessed 23 January 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y3rorava

- Institute for Canadian Citizenship (ICC). 2014. “Playing Together: New Citizens, Sport & Belonging.” Accessed 23 January 2021. https://tinyurl.com/yyzbnvfy

- Jeanes, R., O’ Connor J., and Alfrey L. 2015. “Sport and the Resettlement of Young People from Refugee Backgrounds in Australia.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 39 (6): 480–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514558929.

- Kaukko, M. 2016. “The P, A, and R of Participatory Action Research with Unaccompanied Girls.” Educational Action Research 24 (2): 177–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1060159.

- Keles, S., O. Friborg, T. Idsøe, S. Sirin, and B. Oppedal. 2018. “Resilience and Acculturation among Unaccompanied Refugee Minors.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 42 (1): 52–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416658136.

- Kidd, S., L. Davidson, T. Frederick, and M. J. Kral. 2018. “Reflecting on Participatory, Action-Oriented Research Methods in Community Psychology: Progress, Problems, and Paths Forward.” American Journal of Community Psychology 61 (1–2): 76–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12214.

- Kral, M. J. 2014. “The Relational Motif in Participatory Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (2): 144–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413510871.

- Kumar, R., N. Seay, and S. A. Karabenick. 2015. “Immigrant Arab Adolescents in Ethnic Enclaves: Physical and Phenomenological Contexts of Identity Negotiation.” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 21 (2): 201–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037748.

- Kwan, C., and C. A. Walsh. 2018. “Ethical Issues in Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research: A Narrative Review of the Literature.” The Qualitative Report 2 (4): 369–386. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss2/6. doi:https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3331.

- Land, C. 2015. Decolonizing Solidarity: Dilemmas and Directions for Supporters of Indigenous Struggles. London: Zed Books.

- Leitch, R. 2008. “Creatively Researching Children’s Narratives through Images and Drawings.” In Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People, edited by P. Thomson, 37–57. New York: Routledge.

- Letiche, H. 2010. “Polyphony and Its Other.” Organization Studies 31 (3): 261–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609357386.

- Ley, C., M. R. Barrio, and A. Koch. 2018. ““In the Sport I Am Here”: Therapeutic Processes and Health Effects of Sport and Exercise on PTSD.” Qualitative Health Research 28 (3): 491–507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317744533.

- Lopez, J. 2003. Theatrical Convention and Audience Response in Early Modern Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mauro, M. 2013. “A Team Like No ‘Other’: The Radicalized Position of Insaka FC in Irish Schoolboy Football.” Soccer & Society 14 (3): 344–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2013.801265.

- McDonald, B., R. Spaaij, and D. Dukic. 2019. “Moments of Social Inclusion: Asylum Seekers, Football and Solidarity.” Sport in Society 22 (6): 935–949. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1504774.

- Middleton, T. R. F., B. Petersen, R. J. Schinke, San F. Kao, and C. Giffin. 2020. “Community Sport and Physical Activity Programs as Sites of Integration: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research Conducted with Forced Migrants.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 51: 101769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101769.

- Middleton, T. R. F., R. J. Schinke, B. Habra, D. Coholic, D. Lefebvre, and K. R. McGannon. 2021. “The Changing Meaning of Sport during Forced Immigrant Youths’ Journeys.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 54: 101917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101917.

- Nathan, S., L. Kemp, A. Bunde-Birouste, J. MacKenzie, C. Evers, and T. A. Shwe. 2013. ““We Wouldn’t of Made Friends If We Didn’t Come to Football United”: The Impacts of a Football Program on Young People’s Peer, Prosocial and Cross-Cultural Relationships.” BMC Public Health 13 (399): 399–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-399.

- Papathomas, A., and D. Lavallee. 2012. “Narrative Constructions of Anorexia and Abuse: An Athlete’s Search for Meaning in Trauma.” Journal of Loss and Trauma 17 (4): 293–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.616740.

- Parker, N., and O’Reilly M. 2013. “We Are Alone in the House”: A Case Study Addressing Researcher Safety and Risk.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 10 (4): 341–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2011.647261.

- Pizzolati, M., and D. Sterchele. 2016. “Mixed-sex in sport for development: A pragmatic and symbolic device. The case of touch rugby for forced migrants in Rome.” Sport in Society 19 (8–9): 1267–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1133600.

- Pratt, G. 2007. “Working with Migrant Communities: Collaborating with the Kalayaan Centre in Vancouver, Canada.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation, and Place, edited by S. Kindon, R. Pain, and M. Kesby, 95–103. New York: Routledge.

- Rolfe, G. 2002. “‘Lie that Helps us See the Truth’: Research, truth and fiction in the helping professions.” Reflective Practice 3 (1): 89–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940220129898.

- Schinke, R. J., K. R. McGannon, W. D. Parham, and A. M. Lane. 2012. “Toward Cultural Praxis and Cultural Sensitivity: Strategies for Self-Reflexive Sport Psychology Practice.” Quest 64 (1): 34–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2012.653264.

- Schinke, R. J., Middleton, T. R. F., Petersen, B., Kao, S., Lefebvre, D., and Habra B. 2018. “Social Justice in Sport and Exercise Psychology: A Position Statement.” Quest 71 (2): 163–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2018.1544572.

- Schinke, R. J., B. Smith, and K. R. McGannon. 2013. “Pathways for Community Research in Sport and Physical Activity: Criteria for Consideration.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health 5 (3): 460–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.846274.

- Schinke, R. J., N. R. Stambulova, R. Lidor, A. Papaioannou, and T. V. Ryba. 2016. “ISSP Position Stand: Social Missions through Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14 (1): 4–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.999698.

- Shields, D. L., and B. L. Bredemeier. 2007. “Advances in Sport Morality Research.” In Handbook of Sport Psychology. 3rd ed., edited by G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund, 662–684. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Sinding, C., R. Warren, and C. Paton. 2014. “Social Work and the Arts: Images at the Intersection.” Qualitative Social Work 13 (2): 187–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325012464384.

- Smith, L. T. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. Dunedin: University of Otago Press.

- Smith, B., and K. R. McGannon. 2018. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (1): 101–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Spaaij, R. 2009. “Sport as a Vehicle for Social Mobility and Regulation of Disadvantaged Youth.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 44 (2–3): 247–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690209338415.

- Spaaij, R. 2015. “Refugee Youth, Belonging, and Community Sport.” Leisure Studies 34 (3): 303–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.893006.

- Spaaij, R., N. Schulenkorf, R. Jeanes, and S. Oxford. 2018. “Participatory Research in Sport-for-Development: Complexities, Experiences, and (Missed) Opportunities.” Sport Management Review 21 (1): 25–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.106/j.smr.2017.05.003.

- Sport Canada. 2012. “Canadian Sport Policy 2012.” Accessed 23 January 2021. https://tinyurl.com/y3nltxea

- Statistics Canada. 2019. “The 10 Highest Population Densities among Municipalities (Census Subdivisions) with 5,000 Residents or More, Canada, 2016.” Accessed 23 January 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170208/t001a-eng.htm

- Steel, Z., D. Silove, R. Brooks, S. Momartin, B. Alzuhairi, and I. Susljik. 2006. “Impact of Immigration Detention and Temporary Protection on the Mental Health of Refugees.” The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 188: 58–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007864.

- Stone, C. 2018. “Utopian Community Football? Sport, Hope, and Belongingness in the Lives of Refugees and Asylum Seekers.” Leisure Studies 37 (2): 171–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1329336.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2019.” Accessed 23 January 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2019/

- Whitley, M. A., W. V. Massey, and M. Wilkison. 2018. “A Systems Theory of Development through Sport for Traumatized and Disadvantaged Youth.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 38: 116–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.004.

- Woodhouse, D., and D. Conricode. 2017. “In-Ger-Land, in-Ger-Land, in-Ger-Land! Exploring the Impact of Soccer on the Sense of Belonging of Those Seeking Asylum in the UK.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 52 (8): 940–954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216637630.