Abstract

The importance of gender equality and equity in sports is highlighted not only in practice but also in research; however, previous research has often treated sports as a single context and has disregarded game-specific differences and characteristics. This research addresses this gap by building on a multi-level framework and utilizing a case study approach to increase understanding of why women in leadership positions (employed staff) are underrepresented in the sport of football (soccer) in two Nordic countries, Finland and Norway. The findings show that regardless of the general good state of gender equality in the Nordic countries and even if major barriers have been removed, women aiming for leadership positions face structural and cultural bottlenecks that hinder their possibilities in Nordic football. In addition, this article identifies factors that have improved gender equality in case organizations and suggests new means to address inequality.

Introduction

Regardless of the growth of women in leadership positions in general (OECD Citation2018; Gram Citation2021; Statistics Finland, n.d.) and women being players, consumers, and other actors in different sports, the number of women leaders in sports remains low, especially in the top management positions (e.g. Aalto-Nevalainen 2018; Burton Citation2015; Sartore and Cunningham Citation2007). This also applies to the Nordic countries, which emphasize gender equality and are forerunners in work-life gender equality, and to football, which is the largest organized sport in Norway and the largest ball game in Finland for girls and women (Fasting, Sand, and Nordstrand Citation2019; Lehtonen, Oja, and Hakamäki Citation2022; Pfister Citation2015). During last decades, research has increasingly paid attention to gender inequality in leadership position in sports (see Burton Citation2015; Burton and Leberman Citation2017 for reviews). Scholars have argued that this body of work is critical because it is ethically correct that gender should not prevent an individual from reaching decision-making positions (Adriaanse Citation2016). Moreover, women’s inclusion increases the talent available for these positions and enhances organizational outcomes (Adriaanse Citation2016). Finally, as sports are integral part of the society, inequality in sport-related organization arguably reflects to other parts of the society as well (e.g. Fink Citation2016).

However, previous research has been rather narrow, focusing on specific country contexts and treating sports as a single entity. This study bases on the idea that leadership must be contextualized. Contextual factors set the possibilities and constraints within which women’s advancement into leadership positions is built. For instance, treating sports as a monolithic block does not take into consideration the game-specific characteristics of different sports and the gendered and segmented nature of sports. Moreover, a large part of previous research focuses on the North American context, especially the US intercollegiate system (Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Hancock and Hums Citation2016). This context differs significantly from those of Nordic countries because of the Nordic welfare model and its ideology of equality at all levels and sectors (Skille Citation2014). In the Nordic context, many studies have focused on elected leaders and individuals in elected decision-making positions, such as in the boards of sports organizations (e.g. Elling, Hovden, and Knoppers Citation2019; Hovden Citation2000, Citation2010, Citation2012), leaving a gap for studies on women in managerial leadership positionsFootnote1 in sports organizations. The demands and requirements for women’s advancement differ depending on contextual dynamics and boundaries. Therefore, it is relevant to focus on gender (in)equality within leadership positions in Nordic football.

The aim of this study was to increase the understanding of gender (in)equality in managerial leadership positions in football and thus to bridge the gap in the present literature and to answer the call of Valenti, Scelles, and Morrow (Citation2018) for more research on gender (in)equality in managerial leadership positions in football. Football offers an interesting, paradoxical context for this study, as football is one of the most popular sports for women and girls while being male dominated and having a masculine environment (Fasting, Sand, and Nordstrand Citation2019; Skille Citation2014). More specifically, this research seeks to answer why women in leadership positions are underrepresented in Norwegian and Finnish football organizations by using an instrumental case study approach to study the cases of the Football Association of Finland (FAF) and Norwegian Football Federation (NFF) (Stake Citation2003). The aim of this article was not to compare the two cases but rather to study them as examples for exploring and describing the phenomenon in the Nordic countries, as Finland and Norway share similar contexts and aims regarding gender equality in sports.

This study contributes to the literature on women in leadership positions in sports by investigating the underrepresentation of women from the viewpoint of football organizations in their societal contexts. It offers new empirical evidence from this viewpoint, highlighting the cultural aspects and thus offering a broad overview into its topic in a specific sports context and opening up relevant avenues for further research. The article contributes to practice by identifying factors that have improved gender equality in the case organizations and by suggesting further actions to address the issue in Nordic football.

Theoretical frame and relevant literature

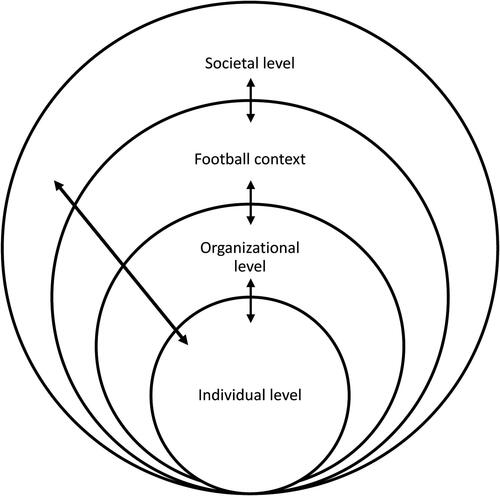

Researchers studying women in leadership positions have used several concepts and metaphors to explain women’s under-representation: ‘the leaking pipeline’ (Hancock and Hums Citation2016), ‘glass ceiling’ and firewalls (Bendl and Schmidt Citation2010); however, these concepts and metaphors tend to apply only one or two theories or analysis levels. Research on gender issues in the sport context is ‘situated in multi-level, sometimes subtle, and usually taken-for-granted structures, policies and behaviours embedded in sport organizations’ (Fink Citation2008, 147). Cunningham (Citation2010, 396) added that ‘sport organizations are multi-level entities that both shape and are shaped by myriad factors’. Hence, a multi-level framework (e.g. Burton Citation2015; Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Cunningham Citation2019; Cunningham and Sagas Citation2008; LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012) based on the multi-level organizational theory (Kozlowski and Klein Citation2000) and Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1977, Citation1979, Citation1993) ecological systems theory refined by Cunningham (Citation2019) was chosen to guide the analysis. The framework captures the complexity of the multi-level entity of sports organizations and the many interrelated and dynamic factors influencing women leaders in football. Cunningham’s (Citation2019) framework consists of micro, meso and macro levels. In this study, a sport-specific context level (football) was added to emphasize the importance of noting differences between different sports (see ). As the full reach of this comprehensive framework is beyond the scope of this article, the focus was on the macro, meso and context levels, especially their cultural aspects, although the interplay of all four levels is acknowledged.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework (adapted from Cunningham Citation2019, 78).

Gender and leadership

Femininity and masculinity are defined within and created ‘out of a complex of dynamic interwoven, cognitive, emotional and social forces’, and essentially connected to the bodies of men and women (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000, 145–146). Femininity and masculinity are often seen as mutually exclusive, and throughout history, male and female have been opposed using contrary traits such as rationality/emotionality, objectivity/subjectivity and culture/nature (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000). Different kinds of masculinities and femininities exist (Collinson and Hearn Citation1996). However, the dominant form of men and masculinity in sport leadership tends to be heterosexual, white, able-bodied, middle-aged and physically dominant. The discourses about sport leadership highlight qualities traditionally perceived as masculine, such as mental and physical toughness and competitiveness (Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Shaw and Hoeber Citation2003) or, as Hovden (Citation2000) described, a ‘male heavyweight profile’.

However, the idea that management and leadership are firmly constructed as culturally masculine or that females in leadership positions deviate from these constructions cannot be taken for granted (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000; Pullen and Vachhani Citation2018). Due Billing and Alvesson (Citation2000) argue that recent conceptions of leadership and management are increasingly in line with values and orientations that the gender literature often labels as feminine. This means that the polarization of masculinity and femininity in leadership is fading. Empirically, women and men in leadership positions tend to be rather similar in terms of, for example, aims, values and characteristics (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000; Mikkonen, Stenvall, and Lehtonen Citation2021; Lehtonen, Oja, and Hakamäki Citation2022).

The literature on gender and leadership is often general, embracing stereotypical ideals, with no distinctions between different groups of women and men or different historical or cultural settings (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000). Pullen and Vachhani (Citation2018) continue that the current conceptions of feminine leadership cannot capture femininity in all its differences. This study acknowledges the challenges of the concept of feminine leadership (see e.g. Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000; Pullen and Vachhani Citation2018) and thus uses feminine leadership as a critical concept (see Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000); that is, the concept is not used to emphasize the stereotypes, idealized and essential views on skills and orientations related to the female sex but rather as a concept de-masculinizing leadership, unwinding the relationship between leadership and its cultural connections to masculine men and dominant masculinity (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000).

Socio-cultural (macro) perspectives

Sports are closely intertwined with society and reflect wider societal norms and practices (Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Fink Citation2016). Regardless of gender inequality being a global phenomenon, it is context dependent (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000). Much of the existing literature is based on the North American context and thus cannot be applied to the context of Nordic welfare states without further scrutiny. They offer a point of departure for increasing the understanding of the phenomenon in other contexts.

Macro-level perspectives operate at the societal level, such as employment and anti-discrimination laws (see Chapter 3.1), institutional sexism, and stakeholder expectations (Cunningham Citation2019). Institutional sexism refers to ideas about gender and the appropriate roles and behaviours of women and men that become rooted in a given culture (Cunningham Citation2019; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006). For instance, sport organizations identify male activity as privileged and reinforce masculinity and masculine behaviour as the proper qualities for leadership, which reinforces gender discrimination in sport organizations (Burton Citation2015; Cunningham Citation2019; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006). Women are often perceived as an ‘other’ in the social institution of sport and thus experience heavy scrutiny (Acker Citation1990; Fink Citation2016; Welford Citation2011). Thus, they may have to use extra time and energy to adapt to the masculine culture and may feel that they must prove their competence to a greater extent compared to men (Kumra and Vinnicombe Citation2010). Partly impacted by institutional sexism, internal and external stakeholders’ (e.g. players, coaches, community members and financial supporters) expectations often serve to reinforce gendered norms and stereotypes, thus preventing women to achieve leadership positions in sports (Cunningham Citation2019).

Football, management and gender in Finland and Norway

Finland and Norway are Nordic welfare states and top countries in terms of work-life gender equality compared to the rest of the world. Norway is a small step ahead of Finland in some indicators of gender equality in work-life, such as the number of female senior managers and directors (OECD Citation2018; World Economic Forum Citation2019). Finnish and Norwegian women have higher educational attainments than men, but they are still a minority in top management positions.

The football culture is gendered: it is dominated and identified by masculinity (Fasting, Sand, and Nordstrand Citation2019; Pfister Citation2015; Skille Citation2014). The domination of masculine values, ideas, and meanings reinforce the gendered culture (Fasting, Sand, and Nordstrand Citation2019) and produce and reproduce symbolic and social gender orders, which shape gender relations in football (Hjelseth and Hovden Citation2014). Women in football are a new phenomenon compared to men. For instance, women’s football became part of the FAF in 1971 and the NFF in 1976 (approximately 70 years after the organizations were founded); however, women’s football has grown rapidly in recent years. The FIFA Citation2019 Women’s World Cup enjoyed global interest and success. The appreciation of the sport, the number of people following the sport, and the number of girls and women participating in the sport has all increased (FIFA Citation2019). Football is the largest organized sport in Norway and the largest ball game in Finland for girls and women (Fasting, Sand, and Nordstrand Citation2019; Lehtonen, Oja, and Hakamäki Citation2022; Pfister Citation2015). The women’s national teams in these countries have succeeded well and have held higher FIFA rankings than their male peers for many years. Nonetheless, women’s success in the football pitch and the increasing numbers of girls and women associated with football and women in leadership positions in general have not been matched with the number of women in leadership positions in the national governing bodies of football, the FAF and NFF.

Organizational (meso) perspectives

Meso-level perspectives operate at the organizational level, such as diversity policies (see Chapter 3.1), bias in decision-making, organizational culture and power relations (Cunningham Citation2019).

Stereotypes are the first component of bias and represent ‘traits that we view as characteristics of social groups, or of individual members of those groups, and particularly those that differentiate groups from each other’ (Stangor Citation2009, 2; Cunningham Citation2019). They are socially constructed and time bound in a given culture. Stereotypes have been passed on for decades from one generation to another; therefore, they are often subconscious and difficult and slow to change (Vinnicombe and Singh Citation2002). Sport leaders are still associated with men and masculine behaviour. Therefore, women are less likely to be considered as managers and leaders (Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Grappendorf and Burton Citation2017; Hovden Citation2010). The strength of the ‘think manager, think male’ association has decreased over the years; nevertheless, it still remains in the structures and cultures of sport (Cunningham Citation2019). The second component, prejudice, refers to the differential evaluation of one group relative to another (Brewer Citation2007). Particularly challenging for women in leadership positions is their double bind: women are expected to be feminine, but as leaders, they are expected to fit into the traditional, masculine leadership style (Grappendorf and Burton Citation2017). The last component of bias, discrimination can be divided into access and treatment discrimination (Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley Citation1990). Access discrimination occurs when members of a certain group are excluded from entering an organization or a leadership position. Treatment discrimination refers to members of certain groups receiving fewer organizational resources than they legitimately deserve.

The gendered cultures privileging men in sports may reinforce the assumption that men are also better suited for leadership positions. Following Schein (Citation2004, 17), culture can be defined as ‘a pattern of shared assumptions… that has worked well enough to be considered valid, and therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct ways to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems’. Values, norms, and the visible and invisible rules of sport organizations are often based on masculine norms (Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Grappendorf and Burton Citation2017). Therefore, it may be difficult for women to adapt to organizations and further their careers. Women may feel trapped as the minority because they cannot change the masculine culture and procedures; they must adapt or decide not to join (Liff and Ward Citation2001). Cultures have been passed on and maintained over time, so they have become taken for granted (Cunningham Citation2019). Therefore, it may be difficult for people to critically question the structures, values and processes privileging men over women. For instance, the general assumption is often that work and organizational practices are gender neutral (Acker Citation1990; Burton and Leberman Citation2017).

Eagly and Carli (Citation2012) suggest that pressure related to family responsibilities is a major barrier for women in leadership positions. Leadership positions often include travelling, challenging hours and overtime work. Women are expected to take the main responsibility for the home and family; thus, combining family and demanding work is often viewed only as a woman’s problem. Even if women have shared childcare with their spouses or family, or paid work, decisions makers often assume that women are responsible for the home and family; therefore, they are not deemed suitable for demanding positions (Eagly and Carli Citation2012). Similar findings relate to the sport management setting (e.g. Shaw and Hoeber Citation2003).

Lastly, power and power relations impact women leaders in sport organizations (Burton and Leberman Citation2017). Often, power is held by a few individuals belonging to traditional majority groups in sport organizations: ‘white, heterosexual, Protestant, and able-bodied men’ (Cunningham Citation2019, 142). Previous research has also shown evidence that men may not be willing to give up their positions of power (Ottesen et al. Citation2010; Pfister Citation2010). Sheridan and Milgate (Citation2003) evidenced that members of the dominant group (i.e. men) are not concerned about the underrepresentation of women and do not question the present situation sustaining their dominance. Men desiring to maintain power while holding the key to the inclusion of women in leadership are challenging.

Individual (micro)-level perspectives

Micro-level perspectives, such as human and social capital and self-limiting behaviour operate at the individual level (Cunningham Citation2019). Similar to macro- and meso-level factors, micro-level factors are interrelated with factors operating at the meso and macro levels. If this interplay is left unrecognized, micro-level scrutiny may falsely turn into blaming women (Cunningham Citation2019). ‘Human capital’ refers to individual development through, for example, education, work experience, and training and ‘social capital’ to networks and relationships with peers, supervisors and subordinates (Sagas and Cunningham Citation2004). Regardless of whether women have greater human capital than men, they may not receive great returns (Cunningham Citation2019). Furthermore, social capital seems to be more beneficial for men than for women in a leadership career (Sagas and Cunningham 2004). Sartore and Cunningham (Citation2007) suggest that women may unconsciously produce self-limiting behaviours due to the male-dominant sport context. ‘Self-limiting behaviour’ refers to internal identity comparison processes in which women compare themselves to the meanings established through social and sport ideologies, which may prevent women from viewing themselves as leaders and thus prevent them from acting as leaders (Sartore and Cunningham Citation2007).

Methodology

Instrumental case study perspective (Stake Citation2003), which means that cases were used as an environment to study the phenomenon, was chosen to examine and describe why women are underrepresented within leadership positions in Nordic football. This approach was chosen because factors influencing women in leadership positions are complex and, to some extent, unconscious and they must be studied in their context. The case study approach is appropriate for this study, as it allows phenomena to be studied in-depth in the real-life context (Yin Citation2018). The study has two units for analysis, the FAF and NFF, which were examined monolithically as examples illustrating the phenomenon in the Nordic countries. The main research data were obtained from nine semi-structured interviews. In addition, organizational documents (strategic and equality plans) and archives (data from the NFF and FAF websites) were used as secondary data.

The FAF and NFF were selected as the case organizations for several reasons. First, Finland and Norway are generally considered top countries regarding gender equality in work-life and are composed of increasing numbers of women leaders (OECD Citation2018; Statistics Finland n.d.; Gram Citation2021). Second, the football associations (FAs) are among the largest and thus most powerful sport governing bodies in these countries. Third, the numbers of women and girls playing, watching, and, otherwise, participating in football have been increasing, but the number of women in leadership positions remains low.

Case organizations

The FAF was founded in 1907. It joined the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) in 1908 and the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) in 1954. The FAF has nearly 1000 member clubs and more than 140,000 registered players, of whom 32,500 (23%) are girls and women. The FAF has 81 employees, of whom 22 (27%) are women (as of December 2018). No women hold top leadership positions (five positions), and only two of seven of the middle-managers are women (Suomen Palloliitto Citation2019). As of 15 April 2021, the board of the FAF consists of eight persons, including two women. The chairperson is a man, and the first vice-chairperson is a woman. The FAF 2016–2020 strategy states that attention should be given and actions should be taken to increase the number of women in different football positions, especially in coaching and leading (Suomen Palloliitto Citation2016, 28).

The NFF was founded in 1902 and joined FIFA in 1908 and UEFA in 1954. The NFF has nearly 1800 member clubs and more than 337,000 registered players, of whom 96,000 (29%) are girls and women. The NFF has 118 employees, of whom 28 (24%) are women (as of April 2021). As of 15 April 2020, the NFF website lists seven top leadership positions, of which two are filled by women, and 16 middle-management positions, of which one is held by a woman. The NFF board consists of eight people, including four women. The chairperson is a man, and the first vice-chairperson is a woman. The NFF strategy states that one of its main goals is to increase the proportion of girls and women in football and to recruit, educate, and inspire more women players, coaches, referees, managers and representatives (Norges Fotballforbund Citation2021). The NFF had a female general secretary, Karen Espelund, for 10 years between 1999 and 2009.

Both Finland (Act on Equality between Women and Men 1986) and Norway (Act on Gender Equality 1979) have enacted gender equality laws that forbid gender-based discrimination in society, including sports and work. Both acts obligate public decision-making bodies (e.g. government committees, advisory boards and working groups) to be comprised at least 40% female and 40% male members. This obligation applies to public sport organizations but not at the association or club level, including national governing bodies of sports. In Norway, the Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sport (NIF) enacted a quota regulation that concerns all levels of the NIF (including sports clubs). The regulation states that both genders should be represented in elected/appointed decision-making bodies. In bodies with a minimum of four persons, each sex should have at least two representatives (Hovden Citation2012). In Finland, no quota regulations have been imposed, but the state steers sport organizations by requiring them equality and non-discrimination plans to be eligible for government grants (Pyykkönen Citation2016). These regulations impact women’s opportunities at the meso level and have increased the number of women in leadership positions in sport organizations. However, these regulations only apply to elected/appointed positions, not employments.

Interviewees

The interview data were obtained from interviews with nine informants from the FAF and NFF. Interviewees F1, F2 and F3 were women, and Interviewees M4 and M5 were men from the FAF. Interviewees F6 and F7 were women, and interviewees M8 and M9 were men from the NFF. The interviewees were purposefully selected, as it is important in qualitative interviews that the interviewees know as much as possible about the phenomenon studied or have experienced the phenomenon (Patton Citation2014). All the interviewees were employed by the FAs. To include only interviewees with knowledge about the organizational culture and norms, newly hired leaders and chiefs were not chosen as interviewees. As no women and only a few women have held top leadership positions in the FAF and NFF, respectively, women in chief positions were also viewed as relevant informants for this research. Chiefs play managing roles and possess decision-making power in both organizations. All interviewees except for one woman have higher educational levels. However, she had robust coaching education and, at the time of the interview, was enrolled in a higher education programme. The women and men interviewees were approximately 30–55 and 50–60 years old.

The purposeful selection was based on a sample of nine informants (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). In qualitative research, the purpose is not to count opinions or people, or to make statistical generalizations but to describe a phenomenon, understand complex psychosocial issues or find a theoretically meaningful interpretation of a phenomenon (Miles and Huberman Citation1994; O’Reilly and Parker Citation2013). Therefore, sampling in qualitative research considers the richness of the information, and the number of respondents depends on the topic and resources available (O’Reilly and Parker Citation2013). Considering this articles explorative and descriptive nature, the small number of leadership positions in the FAs, the interviewees’ experience in case organizations and the guiding theoretical framework, the chosen number of respondents can deliver meaningful understandings of the phenomenon studied (Crouch and McKenzie Citation2006).

Data collection and analysis

The study received approval from the Norwegian Data Protection Official, after which the 10 chosen interviewee candidates were contacted. Nine agreed to the interview. The participants gave their written or oral consent to participate and had the opportunity to withdraw from the study at any time. The interviews took place between 7 March and 25 April 2019. The duration of the interviews varied between 40 and 80 min. One woman from the NFF was interviewed via email, as the researcher could understand written Norwegian, and the other interviews were conducted via Skype and recorded with an external audio recorder. Five interviews were conducted in Finnish; and three, in English. The researcher transcribed the interviews verbatim. All nine interviews produced 91 pages of empirical data written in 11-point font and single-line spacing. The interviews were pseudonymized by coding.

Each interview began with a brief about the aim of the research and structure of the interview to set expectations, followed by a warm-up question about the background and journey of the interviewees to their present positions. Images and values are important in the interactions and practices with which organizations assign meanings to gender and vice versa (Acker Citation1990). Therefore, the following questions considered both the experiences and actions, and the thoughts of the interviewees about organizational culture and structure, gender equality, gender roles and so forth. Secondary data (organizational documents, such as strategic plans, equality plans and archives, such as data from the NFF and FAF websites) were used to complement the interview data to create a holistic image of the context, including organizational structures and culture, as well as the organizations’ aspirations towards gender equality.

The analysis was based on a reflective thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke, and Weate Citation2016). First, the author familiarized with the data by reading, re-reading and taking notes. After which, the data were coded using both deductive and inductive approaches. The deductive approach was driven by the theoretical frame and relevant literature (Chapter 2). The inductive approach enabled possible new additional themes and patterns to be identified and to generate a further understanding of this phenomenon. Finally, the codes were refined into relevant themes in relation to the research question (Braun, Clarke, and Weate Citation2016).

Results and discussion

This section presents the empirical results and simultaneous interpretations and discussions based on the theoretical framework and relevant literature.

Gendered organizational culture

Gendered stereotypes and gender roles were still present in both FAs at least to some extent. Both men and women interviewees at the FAF showed that gendered behaviour and the presence of a masculine ‘locker room’ culture had decreased at the FAF; however, some female interviewees still had experiences with masculine culture. They reported that the locker room culture offends some employees, which may be the reason for gendered stereotypes, ‘bad humour’, and rough communication. They argued that the masculine culture may have a negative influence on the self-confidence of some women and thus on their willingness to accept responsibilities to enhance their careers. Male interviewees argued that gendered behaviour used to be more common but may still exist:

Yeah, of course there could be these kinds of things (gendered stereotypes and behaviour), but I cannot really say that there is or that I’ve come across them. But then again, I am not trying to argue that on an absolute level, these things do not ever take place. (Interviewee M4)

I think that in debates between women and men and when we discuss topics regarding that, it is easy to be described as an old man with old or old-fashioned statements and thoughts. So, people having the opposite view, they try to brand people and use it against us. We are not experienced when it comes to that topic—then we are just old. (Interviewee M8)

In addition to cultural barriers at the meso level, the low level of employee turnover poses a structural barrier for women aiming for a leadership position. The interviewees reflected on how people tend to stay at the FAF and NFF for long periods. On one hand, this may be an indication of a good organizational culture. Those employed by these organizations enjoy working for them. If people felt unhappy, the employee turnover would be greater. On the other hand, if the employees want to secure leadership careers in football, they may not have options other than to stay at the FAs because they are the highest football organizations in these countries. Regardless, the low level of employee turnover negatively impacts women aiming for leadership positions: even if more women managers were wanted at the FAF and NFF, the process of change is slow, as the positions do not open until old managers, mostly men, retire. Changing the proportion of managers is more difficult than that of people in elected decision-making positions (e.g. chairs/board members) because of the Nordic labour laws that protect employees’ rights. The organizations cannot discharge staff for new staff.

Attitudes of the case organizations towards families

Previous research has cited that the presumption of women having the main responsibility for the home and family hinders women’s leadership careers (Eagly and Carli Citation2012; Shaw and Hoeber Citation2003). Contradicting previous research, the interviewees did not feel that being a mother restricts one’s leadership possibilities to a greater extent than being a father. The attitude of the FAF towards family and personal life was described as supportive and flexible by all interviewees. Parental leave is viewed as equally natural for both men and women, and flexible hours are offered to both: ‘these days, both fathers and mothers are using parental leaves, and we encourage, or let’s not say that way but in this way, that we are not being an obstacle for using parental leaves in any case’ (Interviewee M5). The interviewees described the NFF as rather flexible and understanding towards family and work; however, both male and female interviewees highlighted that they work a lot, including weekends and evenings:

You have to be aware of that ‘a lot of work is done on weekends, evenings and in the summer] when you apply for a job like this, especially if you have school-aged children.’ (Interviewee M9)

The importance of gender-balanced leadership

Similar to previous research, the data obtained in this study indicated that both organizations have fewer women than men in decision-making positions, men and women tend to hold different types of leadership positions, and women lead lower down in the hierarchy in the FAF and NFF (e.g. Aalto-Nevalainen 2018; Burton Citation2015; Hovden Citation2010; Sartore and Cunningham Citation2007; Welford Citation2011). At the FAF, men hold the five highest positions and form the executive management group. Women are employed as chiefs and middle managers. Four female chiefs holding a supporting management role are part of the extended executive management group. In the NFF, two women hold the highest leadership positions, of whom one is the human resource (HR) manager, and the other is the director of elite football. In addition, four women are middle managers. Positions traditionally viewed as more feminine and as supportive positions (e.g. HR manager) are held by women, whereas more operational leadership positions are often held by men. Tharenou (Citation2005) argued that this causes women to lack line management and operational experience, which may decrease women’s opportunities to acquire the holistic organizational knowledge needed in top management. The NFF interviewees mentioned that there has been a female general secretary at the NFF and believed this paved the way for other women reaching for a leadership position. At the FAF, there has never been a female top manager; however, almost all FAF interviewees viewed the current gender ratio within leadership positions as good and equal:

I feel that it [gender equality and the position of women] comes rather naturally at the moment, and I see that the base is ready for this kind of action to be continued also in the future without it being a big issue; however, I see it as important through our equality plan and other actions that gender equality is a matter that is written down, so that we don’t think that as it is equal now [the state of gender equality], it will also be in the future. (Interviewee M4)

Unlike at the FAF, only one male interviewee from the NFF was satisfied with the current gender ratio within leadership positions, and all but one male interviewee viewed having men and women leaders as important. This dissatisfaction with the current gender ratio may be a factor influencing the NFF to actively seek and attract competent women (e.g. in 2019, they hired a female director for elite football). The men also expressed that the current gender ratio at the NFF may reflect the general culture and attitude towards gender equality in Norway, which seems to be a step ahead of Finland (OECD Citation2018; World Economic Forum Citation2019). As sports and football are intertwined with society (Fink Citation2016), changes and developments in general gender equality also impact football organizations.

Football culture

On the context level, the lack of football-specific experience may pose a barrier influencing women’s tendency to hold supportive leadership roles instead of core operational leadership roles. First, the interviewees saw football-specific experience as crucial in many leading positions at both FAs, especially within core departments (e.g. elite sport department):

We have seen examples of people, of older women, that are well educated, with a good resume, good reputation, coming in here and not being able to function because they didn’t understand football. They didn’t understand how people think in a football club or in a football organisation. In this case, you’re not suited, and then it doesn’t matter if you’re a man or a woman. (Interviewee M8)

Second, women’s football competence is often derived from women’s football, which may not be as highly valued as competence gained from men’s football. An interesting contradiction in the data is that a male interviewee from the FAF argued that women’s and men’s football are equally valued in the organization. Regardless, the actions are contradictory. Women, whose competence is often from female football, are said not to have the right kind of football competence needed in leadership positions. Women’s football as a sport is gaining appreciation at the FAF, although experience derived from it is not. This contradiction is especially harmful for women, who tend to work within women’s football. Furthermore, it may be easier for a man to work within men’s football and gather experience, whereas a woman in a men’s football club, especially in a leading position, may have to prove her capabilities as a woman and may receive extra attention for breaking gender roles. Similar experiences were expressed by some of the women interviewed:

At the moment, I am not interested. For instance, if someone came to ask me to do ‘Heimebane’ kinda thing, I could sign up for that if I could only focus on football. But as the time is not ready for that yet, I would have to be on barricades only because of this ‘woman thing’, and I would be assessed mainly as a woman and not as a professional, and I don’t want to use energy for that right now. (Interviewee F2)

Third, football is still generally perceived as a masculine environment; however, the FAs are responsible for the development and operations of both men’s and women’s football and are under heavy public scrutiny. Therefore, they must answer the gender equality demands and expectations of the public, media and state government. In this case, stakeholder expectations are not against but for gender equality (c.f., Cunningham Citation2019, 137). Smaller organizations, such as smaller football clubs do not receive the same level of scrutiny. In smaller organizations, especially for male football, gender discrimination and male dominance may be more common owing to the traditional football club context. Therefore, women may face unscalable barriers or feel uncomfortable or unwilling to work in this environment. In relation to the previously discussed notion of football competence from women’s football being undervalued at the FAF, women are automatically handicapped in recruitments and promotions in which football competence is highly valued if they cannot or will not work at the men’s football club level.

Changing perceptions of appropriate sports leaders

As shown earlier, the effects of the gendered (football) culture are still visible in both organizations at least to some extent. However, the interviewees from both FAs felt that the organizations are moving towards a more equal state. The interviewees discussed outside pressure, Nordic culture and its emphasis on gender equality, and the equality challenge as a formal part of the organizations’ agendas and conscious efforts to increase the involvement of women in decision-making roles as factors positively influencing gender equality. Many top managers viewed gender equality as an important value and therefore have undertaken actions to enhance the position of women. For instance, the current male-to-female ratio is considered in recruitment situations. Without support from top management, change towards a more equal gender state would be difficult; however, changing the culture to be more gender equal is a slow process. Interviewee F2 described the situation at the FAF:

We are going in the right direction, and a lot of work is being done for it. But we are not in ideal world yet, and we are behind the associations of Sweden and Norway; however, they have more money, and they can share it more. So, we do have work left, and the association recognizes it and is working more towards it [gender equality] than it has before.

In recent years, women have become more active in sports, and female football has increased its profile. For instance, the 2019 Women’s World Cup reached 1.12 billion unique viewers (FIFA Citation2019), and both associations introduced equal pay for the national teams. The numbers of girls and women playing, coaching, refereeing and participating in football have increased. This trend is visible also in both FAs. The interviewees noted that the numbers of female employees and women applying for leadership positions have increased: ‘It is getting better. I see now that we are recruiting, and for more junior positions, quite a lot of women are applying, and that is good. To become a top manager, you need to start somewhere’ (Interviewee M9). The numbers of women managers and leaders in general have increased in both Finland and Norway (e.g. OECD Citation2018). This may also have a positive influence on football. The perception of a proper leader is changing, and women are being considered competent candidates for leadership positions. Regardless of the reported change to a more gender-equal state, the women still felt that they needed characteristics traditionally perceived as masculine to work in the environment. Female interviewees from the FAF emphasized that they are tough and used to working in a male-dominant field; thus, the locker room culture at the FAF, for instance, does not negatively influence them as it could other women. In other words, women must hold qualities that, according to the interviewees, are not typical for women or they must try to adapt to the masculine norms to cope in the environment. However, at the same time, traditional gender roles are still visible, and women are expected to act according to their gender roles (e.g. Burton Citation2015; Grappendorf and Burton Citation2017; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006). Interviewee F1 described the situation as follows:

Like if I as a woman said out loud all the same things [as men], it would surely raise some eyebrows. I guess this is an issue which is easy to hide behind — men are men, or well, he’s a football player. Especially in here.

In contrast to previous research (e.g. Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Grappendorf and Burton Citation2017; Hovden Citation2010; Shaw and Hoeber Citation2003), traditional heroic and masculine leadership characteristics were not viewed as important, and none of the interviewees described themselves as presenting this leadership style. Instead, more feminine characteristics, such as empathy, listening and discussion skills were emphasized:

I am a leader that is listening, that wants to have things on the table. I am not the kind of demanding leader who tells people what to do. At some point you need to do that as well… But my job is to facilitate. (Interviewee F7)

Although softer leadership qualities are valued in these organizations, women in leadership positions are a minority. The interviewees reflected that leadership styles in general have changed towards becoming more feminine. This means that male leaders have also adopted a softer leadership style (taking into account the long careers in the organizations). Men’s adaptation may just be a manifestation of popular, modern leadership theories, a consequence of social pressure or a result of finding it to be more effective; however, it may be that men do not want to relinquish their positions of power (Ottesen et al. Citation2010; Pfister Citation2010). Along with the popularization of leadership styles that emphasize more feminine characteristics, men must adapt – or at least act like they have adapted – to the new demands to keep their power positions. Lämsä and Sintonen (Citation2001) argued that changing the perception of who is capable and valid to lead an organization takes time owing to the masculinity associated with leaders. Interviewee F7 reflected, ‘It takes time to change a culture.’ However, the data suggest that it is not the so-called masculinity or femininity of ideal leadership styles that excludes women from leadership positions. Acknowledging the gendered nature of football and leadership, and the connectedness of masculinity and femininity with male and female bodies (Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000), it may be that it is the female body and the images and stereotypes it represents that are new phenomena in football leadership; thus, women are seen as less fit to lead and manage.

Concluding remarks

The aim of this study was to increase understanding of why women in leadership positions are underrepresented in Nordic football. Studies on the underrepresentation of women leaders in sports have generally treated sports as a single context and focused on specific country contexts. To the author’s knowledge, this is the first study to examine the phenomenon with empirical evidence in the Finnish and Norwegian football contexts. Thus, this descriptive and exploratory study contributes to the continuing conversation on women and leadership in sports by offering a broad overview into the topic in a single-sport context, with special emphasis on cultural aspects, thus opening up new avenues for further research.

In comparison with previous studies (conducted mainly in the US, e.g. Burton and Leberman Citation2017; Shaw and Hoeber Citation2003), this study shows that some major barriers for women aiming for leadership positions have been broken down (e.g. family-work relation, and heroic and masculine leadership style) in Nordic football. Actions and changes at several different levels have been identified as factors positively impacting gender equality in this article. At the macro level, factors include the cultures of the Nordic countries that emphasize gender equality and state-level policy actions. The meso level includes factors, such as organizational-level policy actions and strategic goals, women pioneers, outside pressure and stakeholder expectations, top management’s conscious efforts to improve gender equality, and the changed leadership culture in the organizations. At the context level, the changing football culture, increased appreciation of women’s football and the increasing number of women and girls playing the sport help to change the football culture and to tackle structural barriers. In line with Cunningham’’ (2019) and Burton’s (Citation2015) findings, this article shows that the barriers women leaders face are dynamic and multi-faceted and emerge from several levels. Thus, multi-level actions are needed to tackle gender inequality in football. However, regardless of the aforementioned actions and changes, women remain underrepresented within leadership positions in Nordic football.

As shown in this study, women in Nordic football face both structural and cultural bottlenecks at different levels in their leadership careers. However, the barriers seem largely intertwined with the following dilemma: football-specific experience (derived from men’s football) is seen as crucial in many leading positions at both FAs. Naturally, this is the case in many organizations and especially in sports, in which a deeper understanding of the national context and the inner workings of a particular federation are seen as crucial to career success. Owing to the fewer female than male actors in football (e.g. players, coaches and referees), the reproduction of male leaders partially comes down to numbers. If men bring with them the masculine/locker room culture from their sporting past into the organization, leadership is applied as a continuation of those socialization norms. To break the reinforcing cycle, actions also addressing the (male) football culture are needed. Many of the present actions address women, such as increased appreciation of women’s football and outside pressure or organizational actions towards gender equality. However, focusing only on women’s football is not enough, as men as the majority shape the culture, values and norms in football. Other actions address increasing gender equality in the FAs. However, as it seems that men keep reinforcing the culture they learned in the past as players and other actors in the FAs, it becomes essential to intertwine the past. As umbrella organizations for football, the FAs have the power and means to steer (men’s) football clubs towards a more inclusive culture. Furthermore, addressing the culture and organizations at the club level would help break the structural barrier of women lacking the right kind of football experience.

Limitations and future research directions

The limitation of a case study is the limited possibilities to generalize the results (Stake Citation2003). However, as in this case, the case study approach provides a possibility to gain in-depth understanding of a particular phenomenon in a given context and thus a possibility to learn. Therefore, this article provides a valuable addition to the continuing discussion on gender, leadership and sports. The data obtained from this research were collected from people in leadership positions at the FAF and NFF. Interviews with people who have aimed for leadership positions but for some reason could not reach or have not reached them could have given a different understanding of the under-representation of women leaders in football. This perspective offers a venue for further studies to increase understanding. Another interesting perspective for further research is the level of football clubs. This research indicates that women are said to lack the right kind of football experience at the club level. More research at different levels of sport is needed to understand the bottlenecks and barriers affecting gender equality in sport management. Furthermore, an even closer examination of the football culture or some aspects of the culture (e.g. what kind of values or social norms form barriers to women pursuing leadership careers in football organizations) would be important for increasing understanding in single-sport contexts.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Professor Jari Stenvall and the two anonymous referees for their insightful comments that have helped improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The author has no potential conflict of interest to declare.

Notes

1 In this study, managerial leadership position refers to a full-time, salaried, managerial position, thus excluding coaches, elected leaders and individuals in other elected decision-making positions.

References

- Acker, J. 1990. “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations.” Gender & Society 4 (2): 139–158. doi:10.1177/089124390004002002.

- Adriaanse, J. 2016. “Gender Diversity in the Governance of Sport Associations: The Sydney Scoreboard Global Index of Participation.” Journal of Business Ethics 137 (1): 149–160. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2550-3.

- Bendl, R., and A. Schmidt. 2010. “From ‘Glass Ceilings’ to ‘Firewalls’—Different Metaphors for Describing Discrimination.” Gender, Work & Organization 17 (5): 612–634. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00520.x.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and P. Weate. 2016. “Using Thematic Analysis in Sport and Exercise Research.” In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Sport and Exercise, edited by B. Smith and A. Sparkes, 191–205. London: Routledge.

- Brewer, M. B. 2007. “The Importance of Being We: Human Nature and Intergroup Relations.” The American Psychologist 62 (8): 726–738. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.728.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–531. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1993. “The Ecology of Cognitive Development: Research Models and Fugitive Findings.” In Development in Context: Activity and Thinking in Specific Environments, edited by R. H. Wozniak and K. W. Fisher, 3–24. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Burton, L. J. 2015. “Underrepresentation of Women in Sport Leadership: A Review of Research.” Sport Management Review 18 (2): 155–165. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2014.02.004.

- Burton, L. J, and S. Leberman. 2017. “An Evaluation of Current Scholarship in Sport Leadership: Multilevel Perspective.” In Women in Sport Leadership: Research and Practice for Change, edited by L. J. Burton and S. Leberman, 16–32. London: Routledge.

- Collinson, D. L, and J. Hearn. 1996. “Breaking the Silence: On Men, Masculinities and Managements.” In Men as Managers, Managers as Men, edited by D. L. Collinson and J. Hearn, 1–24. London: Sage.

- Crouch, M., and H. McKenzie. 2006. “The Logic of Small Samples in Interview-Based Qualitative Research.” Social Science Information 45 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1177/0539018406069584.

- Cunningham, G. B. 2010. “Understanding the under-Representation of African American Coaches: A Multilevel Perspective.” Sport Management Review 13 (4): 395–406. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2009.07.006.

- Cunningham, G. B. 2019. Diversity and Inclusion in Sport Organisations: A Multilevel Perspective. 4th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cunningham, G. B., and M. Sagas. 2008. “Gender and Sex Diversity in Sport Organizations: Introduction to a Special Issue.” Sex Roles 58 (1–2): 3–9. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9360-8.

- Due Billing, Y., and M. Alvesson. 2000. “Questioning the Notion of Feminine Leadership: A Critical Perspective on the Gender Labelling of Leadership.” Gender, Work and Organization 7 (3): 144–157. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.0010.

- Eagly, A. H., and L. L. Carli. 2012. “Women and the Labyrinth of Leadership. Contemporary Issues in Leadership.” In Contemporary Issues in Leadership, edited by W. E. Rosenbach, R. E. Taylor, and M. A. Youndt, 147–162. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Elling, A., J. Hovden, and A. Knoppers. 2019. Gender Diversity in European Sport Governance. London: Routledge.

- Fasting, K., T. S. Sand, and H. R. Nordstrand. 2019. “One of the Few: The Experiences of Female Elite-Level Coaches in Norwegian Football.” Soccer & Society 20 (3): 454–470. doi:10.1080/14660970.2017.1331163.

- FIFA. 2019. “2019: A breakthrough year for women’s football.” FIFA. Accessed 3 August 2020. https://www.fifa.com/womens-football/news/2019-a-breakthrough-year-for-women-s-football/

- Fink, J. S. 2008. “Gender and Sex Diversity in Sport Organizations: Concluding Comments.” Sex Roles 58 (1–2): 146–147. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9364-4.

- Fink, J. S. 2016. “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Embedded Nature of Sexism in Sport.” Journal of Sport Management 30 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1123/jsm.2015-0278.

- Gram, Karin H. 2021. Increase in female leadership, Statistics Norway. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/increase-in-female-leadership.

- Grappendorf, H, and L. J. Burton. 2017. “The Impact of Bias in Sport Leadership.” In Women in Sport Leadership: Research and Practice for Change, edited by L. Burton and S. Leberman, 47–61. London: Routledge.

- Greenhaus, J. H., S. Parasuraman, and W. M. Wormley. 1990. “Effects of Race on Organizational Experience, Job Performance Evaluations, and Career Outcomes.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (1): 64–86. doi:10.5465/256352

- Hancock, M. G., and M. A. Hums. 2016. “A ‘Leaky Pipeline’: Factors Affecting the Career Development of Senior-Level Female Administrators in NCAA Division I Athletic Departments.” Sport Management Review 19 (2): 198–210. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2015.04.004.

- Hjelseth, A., and J. Hovden. 2014. “Negotiating the Status of Women’s Football in Norway. An Analysis of Online Supporter Discourses.” European Journal for Sport and Society 11 (3): 253–277. doi:10.1080/16138171.2014.11687944.

- Hovden, J. 2000. “Heavyweight’ Men and Younger Women? The Gendering of Selection Processes in Norwegian Sport Organizations.” NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 8 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1080/080387400408035.

- Hovden, J. 2010. “Female Top Leaders—Prisoners of Gender? The Gendering of Leadership Discourses in Norwegian Sports Organizations.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 2 (2): 189–203. doi:10.1080/19406940.2010.488065.

- Hovden, J. 2012. “Discourses and Strategies for the Inclusion of Women in Sport—the Case of Norway.” Sport in Society 15 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1080/17430437.2012.653201.

- Kozlowski, S. W. J, and K. J. Klein. 2000. “A Multilevel Approach to Theory and Research in Organizations: Contextual, Temporal, and Emergent Processes.” In Multilevel Theory, Research and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions, edited by K. J. Klein and S. W. J. Kozlowski, 3–90. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Kumra, S., and S. Vinnicombe. 2010. “Impressing for Success: A Gendered Analysis of a Key Social Capital Accumulation Strategy.” Gender, Work & Organization 17 (5): 521–546. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00521.x.

- Lämsä, A., and T. Sintonen. 2001. “A Discursive Approach to Understanding Women Leaders in Working Life.” Journal of Business Ethics 34 (3/4): 255–267. doi:10.1023/A:1012504112426.

- LaVoi, N. M., and J. K. Dutove. 2012. “Barriers and Supports for Female Coaches: An Ecological Model.” Sports Coaching Review 1 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1080/21640629.2012.695891.

- Lehtonen, K., S. Oja, and M. Hakamäki. 2022."Equality in Sports and Physical Activity in Finland in 2021.” Publications of the Ministry of Education Culture 2022: 5. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-263-815-1

- Liff, S., and K. Ward. 2001. “Distorted Views through the Glass Ceiling: The Construction of Women’s Understandings of Promotion and Senior Management Positions.” Gender, Work & Organization 8 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.00120.

- Mikkonen, M., J. Stenvall, and K. Lehtonen. 2021. “The Paradox of Gender Diversity, Organizational Outcomes, and Recruitment in the Boards of National Governing Bodies of Sport.” Administrative Sciences 11 (4): 141. doi:10.3390/admsci11040141.

- Miles, M. B, and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Norges Fotballforbund. 2021. “Strategiplan 2016–2019” [Strategy]. Norges Fotballforbund. Accessed 15 April 2021. https://www.fotball.no/tema/strategiplan-2020-2023/#173324/

- OECD 2018. “Is the Last Mile the Longest?” Economic Gains from Gender Equality in Nordic Countries. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- O’Reilly, M., and N. Parker. 2013. “Unsatisfactory Saturation’: A Critical Exploration of the Notion of Saturated Sample Sizes in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 13 (2): 190–197. doi:10.1177/1468794112446106.

- Ottesen, L., B. Skirstad, G. Pfister, and U. Habermann. 2010. “Gender Relations in Scandinavian Sport Organizations—a Comparison of the Situation and the Policies in Denmark, Norway and Sweden.” Sport in Society 13 (4): 657–675. doi:10.1080/17430431003616423.

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Pfister, G. 2010. “Are the Women or the Organisations to Blame? Gender Hierarchies in Danish Sports Organisations.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 2 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/19406941003634008.

- Pfister, G. 2015. “Assessing the Sociology of Sport: On Women and Football.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 50 (4–5): 563–569. doi:10.1177/1012690214566646.

- Pullen, A, and S. J. Vachhani. 2018. “Examining the Politics of Gendered Difference in Feminine Leadership: The Absence of ‘Female Masculinity.” In Inclusive Leadership. Palgrave Studies in Leadership and Followership, edited by S. Adapa and A. Sheridan, 125–149. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pyykkönen, T. 2016. Yhdenvertaisuus ja Tasa-Arvotyö Valtion Liikuntapolitiikassa – Taustaselvitys Valtion Liikuntaneuvostolle ja Sen Yhdenvertaisuus- ja Tasa-Arvojaostolle [Non-Discrimination and Gender Equality Work in State Sports Policy]. New York, NY: National Sports Council Publications.

- Sagas, Michael, and, George B Cunningham. 2004. “Does Having “the Right Stuff” Matter? Gender Differences in the Determinants of Career Success among Intercollegiate Athletic Administrators.” Sex Roles 50: 411–421.

- Sartore, M. L., and G. B. Cunningham. 2007. “Explaining the under-Representation of Women in Leadership Positions of Sport Organizations: A Symbolic Interactionist Perspective.” Quest 59 (2): 244–265. doi:10.1080/00336297.2007.10483551.

- Schein, E. H. 2004. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Shaw, S., and W. Frisby. 2006. “Can Gender Equity Be More Equitable? Promoting an Alternative Frame for Sport Management Research, Education, and Practice.” Journal of Sport Management 20 (4): 483–509. doi:10.1123/jsm.20.4.483.

- Shaw, S., and L. Hoeber. 2003. “A Strong Man is Direct and a Direct Woman is a Bitch’: Gendered Discourses and Their Influence on Employment Roles in Sport Organizations.” Journal of Sport Management 17 (4): 347–375. doi:10.1123/jsm.17.4.347.

- Sheridan, A., and G. Milgate. 2003. “She Says, He Says’: Women’s and Men’s Views of the Composition of Boards.” Women in Management Review 18 (3): 147–154. doi:10.1108/09649420310471109.

- Skille, E. Å. 2014. “Sport in the Welfare State: Still a Male Preserve: A Theoretical Analysis of Norwegian Football Management.” European Journal for Sport and Society 11 (4): 389–402. doi:10.1080/16138171.2014.11687974.

- Stake, R. 2003. “Case Studies.” In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. 2nd ed., edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 134–164. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stangor, C. 2009. “The Study of Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination within Social Psychology: A Quick History of Theory and Research.” In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, edited by T. D. Nelson, 1–23. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Suomen Palloliitto. 2016. “Strategia 2016–2020 [Strategy].” Suomen Palloliitto. https://www.palloliitto.fi/info/palloliitto/visio-missio-strategia

- Suomen Palloliitto. 2019. “Yhdenvertaisuussuunnitelma 2019–2020 [Equality Plan].” Suomen Palloliitto. https://www.palloliitto.fi/info/palloliitto/visio-missio-strategia/yhdenvertaisuussuunnitelma

- Tharenou, P. 2005. “Women’s Advancement in Management: What is Known and Future Areas to Address.” In Supporting Women’s Career Advancement: Challenges and Opportunities, edited by R. J. Burke and M. C. Mattis, 31–57. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Valenti, M., N. Scelles, and S. Morrow. 2018. “Women’s Football Studies: An Integrative Review.” Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 8 (5): 511–528. doi:10.1108/SBM-09-2017-0048.

- Vinnicombe, S., and V. Singh. 2002. “Sex Role Stereotyping and Requisites of Successful Top Managers.” Women in Management Review 17 (3/4): 120–130. doi:10.1108/09649420210425264.

- Welford, J. 2011. “Tokenism, Ties and Talking Too Quietly: Women’s Experiences in Non‐Playing Football Roles.” Soccer & Society 12 (3): 365–381. doi:10.1080/14660970.2011.568103.

- World Economic Forum. 2019. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

- Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.