Abstract

The global optimism for sport as ‘an important enabler of sustainable development’ by the United Nations appears in many countries’ policy documents. In Ghana, sport is linked to the social dimension of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But the acknowledgement of the potential of sport, in itself, cannot be the decisive evidence of deep commitment or successful implementation. The research analyses how sport partners (governmental and non-governmental) have been involved and resourced in implementing the government’s commitment to the community health and well-being policy. Qualitative data were derived from government policy documents, government officials and key actors from non-state sport organisations. Matland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Model was the theoretical framework used to analyse the policy-implementation link. The findings identified challenges in policy implementation associated with resources distribution, non-involvement of local implementing actors, football’s overbearing importance and legitimation of sport for development organisations. The impact of these challenges for sustainability were discussed.

Introduction

The launch by the United Nations (UN) of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2016 received strong international support from the major economic powers including the International Monitory Fund (IMF) and World Bank. In the discussion of the implementation of the SDGs, sport was identified as ‘an important enabler of sustainable development’ (UNGA (United Nations General Assembly) Citation2015, 3). In light of this, leading international organisations including the African Union, The Commonwealth Sport, World Health Organisation, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and UNESCO (Sherry et al. Citation2019; Burnett Citation2021; Lindsey and Darby Citation2019) as well as some countries (Craig et al. Citation2019; Moustakas and Işık Citation2020; Campillo-Sánchez et al. Citation2021) have incorporated sport into their development policies. In Ghana, the SDGs dominated the political discourse and have been prominent in the government’s business and development policies with, for example, the National Development Planning Commission of Ghana linking sport to the social development dimension of the SDGs (NDPC (National Development Planning Commission) Citation2019). Moreover, contributing to the achievement of the SDGs became the policy goal of the Ministry of Youth and Sport (like all other ministries) from 2016 onwards.

The Ghanaian government has made a strong public commitment to the UN’s SDGs (Ministry of Finance, Citation2019; ElMassaha and Mohieldinb Citation2020) and is relatively well-placed to make progress towards their achievement for four reasons: first, as explained in more detail below successive Ghanaian leaders have worked closely with the UN in devising the SDGs; second, Ghana has a relatively stable political system ranking eighth out of 53 African countries (TheGlobalEconomy.com 2020); third, the country is considered by both the IMF (Agou et al. Citation2019) and the World Bank (Geiger, Trenczek, and Wacker Citation2019) as a fast-growing economy with its per capita GDP just below the average for the continent; and fourth, Ghana hosts over 6,000 non-governmental organisations (Hushie Citation2016; Kumi Citation2017; Ibrahim and Alagidede Citation2020) - a number of which have experience of using sport as a medium for achieving their objectives (Charway and Houlihan Citation2020). Given the relative political and economic stability of Ghana it is arguably a valuable case to test the potential for the successful delivery of SDGs commitments by government.

There have been concerted efforts in Africa where sport as a tool for development has been used to tackle various community health issues like HIV/AID, non-communicable diseases and malaria to mention a few (African Union Citation2008; Delva et al. Citation2010; Hansell, Giacobbi, and Voelker Citation2021; Lindsey and Banda, Citation2011; Mwaanga Citation2010). In Ghana, the government through, the sport ministry has made policy provisions to improve community health and well-being since 2016. In line with target 3.3 of SDG 3 the sport ministry has focused on sensitising Ghanaian youths on reproductive health issues such as sexually transmitted diseases and infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS and more recently the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (Minstry of Youth and Sports Citation2016-2021). Furthermore, the initiation of the Youth and Sports Resource Centres of Excellence (YSRCEs) in 2016 indicated the sport ministry’s commitment as it provides Ghanaian youths with access to recent sport ministry programmes in 2020, such as ‘Reprotalk (Reproductive Talk)’ and ‘Community Information Dissemination for COVID-19’ (Minstry of Youth and Sports Citation2021). The ‘Policy Outcome Indicators and Targets’ in the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework from 2016 to 2021 showed that 8,355,609 Ghanaian youths have been involved in the sport ministry’s community health and well-being programmes (Minstry of Youth and Sports Citation2016-2021).

Scholars on African sport and development policies have noted that many African countries have not just adhered to international policies, but they have also made domestic legislative provision to reinforce the adherence (Lindsey and Bitugu Citation2018). However, governments’ commitment towards implementation and to ensuring compliance are uncertain (Keim and de-Coning Citation2014). It is for this reason that, Keim and de-Coning (Citation2014, 195), in their study of 10 sub-Sahara African countries, stated that despite the available sport policies and legislative arrangements, ‘… further potential exist to improve policy analysis and policy content’.

The purpose of this article is to analyse how, and with what success, the government’s commitment to the SDGs was translated into programme delivery at the local level (regional and district) in relation to health, one of the central SDGs. In addition, the article examines how sport partners (governmental and non-governmental) have been involved and resourced in implementing the government’s commitment to the community health and well-being policy. The next section explores in more detail the status of the SDGs in Ghanaian politics. This is followed by a discussion of Matland’s (Citation1995) Ambiguity-Conflict Model of policy implementation which is used as the framework for the analysis of the empirical data on which the study is based. The findings section analyses the policy implementation challenges at the national, regional and district levels and leads into the concluding discussion.

Institutionalising the SDGs in Ghana

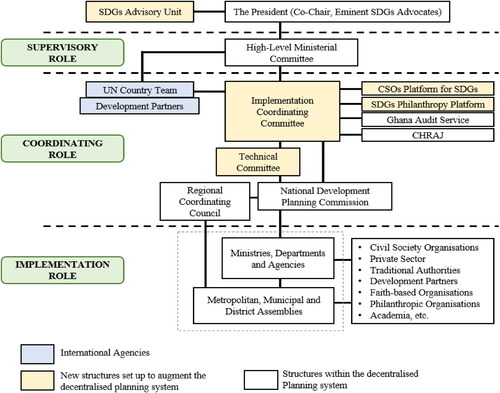

Since the beginning of the millennium, Ghana’s commitment to the UN development goals has survived the nation’s political divide. Four presidents from the two major opposing political parties (the National Democratic Congress and the National Patriotic Party) in Ghana have remained committed to the two sets of UN goals, first the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000–2015) and now the SDGs (2016–2030). As evidence of the strength of their commitment, two successive Ghanaian presidents have served as the Co-Chair of the UN SDGs Advocates Group from 2016 to date (NDPC (National Development Planning Commission) Citation2019). Regardless of how one may look at the SDGs, the presidency of Ghana has been the instrumental ‘link’ between the UN Goals and Ghana’s domestic (sport) policies (Houlihan Citation2009). The government has continually indicated that the SDGs are useful to the local development agenda of Ghana. The depth of national commitment to the SDGs is evident in the government’s development policies (NDPC (National Development Planning Commission) Citation2019; SDGs Advisory Unit of Ghana 2021). Also, domestic policies such as the Ghana Beyond Aid and the 40-year Long-term National Development Plan of Ghana (2018 to 2057) have been designed to reinforce the 17 SDGs. Of the 17 SDGs we focused on health (SDG 3). Health is a part of the social dimension of the SDGs meant to ‘ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages’ (UNGA (United Nations General Assembly) Citation2015, 18). Using sport for health - particularly community wellbeing, and physically active and healthy lifestyle - is one of the key provisions of Ghana’s 2016 Sport Act 934 and one of the major goals of the sport ministry since 2016 (MTEF, 2016–2021). The government adopted a multi-sectorial approach where the services and a plurality of different actors have been institutionalised (see ). The institutionalisation also illustrates how the SDGs policy is intended to be implemented at the local level through funding, partnerships and monitoring and evaluation.

Figure 1. Institutional arrangement for implementing the SDGs in Ghana.

Source: NDPC (National Development Planning Commission) (Citation2019).

Further evidence of the commitment by the government of Ghana through the Ministry of Finance is the development of the SDGs budgeting and tracking system. The budgeting and tracking system is an integrative software system, ‘Hyperion’, that gathers data related to the 17 SDGs (Ministry of Finance 2018, iii). The system serves as the monitoring tool to ensure that budgetary allocations and expenditure of the Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), and Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs, herein referred as district assemblies) reflect the SDGs (ibid.). Funds allocated to the sport ministry support the activities and programmes of the National Sport Authority (NSA), the regional sport offices and the district sport units. It is noteworthy that the regional sport offices are not autonomous as they function in accordance with the missions of and directives from the NSA and the sport ministry. Additionally, the district sport units receive funding support from the MMDA’s District Assembly Common Fund (DACF) which comes from the central government. Such supports fall under the ‘social services’ section of the DACF. The district sport units are composed of members from the Ghana Educational Service, MMDAs, and regional sport offices. Apart from the state sport actors already mentioned, there are also non-state actors such as National Sport Federations (NSFs) and Sport for Development (SDP) organisations which have activities and programmes in the districts. Although the NSFs receive some financial support from the NSA and the sport ministry, the SDP organizations do not (Charway and Houlihan Citation2020).

The information generated from the SDGs budgeting and tracking system is one of the two methods the government uses to evaluate the nationwide implementation of the SDGs. The second method for evaluation is statistical information from the Ghana Statistical Service through national censuses and surveys (GSS (Ghana Statistical Service) Citation2017). It has however been difficult to evaluate the impact of government policy at the local level, particularly the lived experiences of the frontline implementing actors in the regions and districts who directly impact the SDGs (ibid.). With focus on the sport policy subsystem of Ghana vis-à-vis policy implementation, this research filled this gap, by collecting qualitative data from the frontline implementing state and non-state sport organisations in the communities.

For the purpose of this research the policy making authorities were considered to comprise those government institutions that play leading (supervisory and coordinating) roles in the implementation of the SDGs including the Office of the President, National Development Planning Commission, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Youth and Sport and the National Sport Authority (See ). The primary implementing actors at the local level were state (regional and district sport offices) and non-state actors (National Sport Federations and Sport for Development organisations).

Theoretical framework: ambiguity-conflict matrix

Matland’s (Citation1995) model served as the framework for the analysis of issues of policy clarity and comprehensibility tied to low or high ambiguity as well as congruence and relevance tied to low or high conflicts were analysed (Matland Citation1995). Matland specified the appropriateness of the different policy approaches (top-down, bottom-up or combined), in a matrix of four implementation categories, to explain their combined impact on how the interplay of ambiguity and conflict affects policy implementation. Ambiguity refers to the vagueness or uncertainty of policy goals or policy means. Conflict occurs among two or more organisations when policies or resources for implementation are seen as more beneficial to some organisations than others. The model has four policy implementation categories: administrative, political, experimental, and symbolic (see ).

Table 1. Matland’s ambiguity-conflict matrix of policy implementation.

Administrative implementation posits that policies made by authorities are well-defined and understood by implementing actors and that the means or resources to achieve the policies are nonconflictual. The kernel of this category is that the implementation outcome is determined by the provision of adequate resources. Matland mentioned that this category is applicable to the top-down traditions whereby the rational choice decisions of implementing actors are consistent with policy goals. Low policy ambiguity means that there is clarity of policy objectives, compliance, consensus and unfiltered information flows from the top to local implementers. Low policy conflict indicates that implementation guides or toolkits, appropriate human resources and other relevant resources are provided for successful implementation.

Political implementation refers to a situation where there is low policy ambiguity and high policy conflict. Central to achieving implementation outcomes is the power to influence policy. Here, there is clarity of policy goals, however the collective agreement among implementing actors is conflicting and the outcome of the implementation process is determined by which implementing actor or group of implementing actors have enough resources and are best positioned to influence policy. This occurs in two ways, (1) when some implementing actors are favoured by policy makers due to their history, cultural or social significance and (2) when opposing implementing actors construct a strong coalition or have adequate resources to negotiate with the policy making authorities. Policy making authorities may attempt to ensure compliance through coercion, incentives or political promises. Matland noted that in some instances local implementing actors (often far from policy making authorities) may exercise some power by following their own mission and refusing to comply with policy objectives. Though negotiation for cooperation may be initiated with the opposing implementing actors, the top-down approach to policy implementation is more applicable under this category.

Experimental implementation indicates high policy ambiguity and low policy conflict. The central driving force for the implementation outcomes are the contextual conditions which entail resource mobilization by local implementing actors. High policy ambiguity means that policies are subject to different interpretations by local implementing actors. Also, the means of achieving policy objectives may vary among implementing actors. There is low conflict because each local actor implements the ambiguous policies according to their individual interpretation and strength or capacity. The category is experimental because implementation outcomes may be a success or failure depending on resource adequacy of the local implementers. Matland noted that successful implementation produces learning outcomes that are often beneficial to policy making authorities. Sometimes policy makers or governments deliberately make ambiguous policies in order to shift the burden of interpretation to the local implementing actors. More applicable to this category is the bottom-up approach to implementation.

The fourth category, symbolic implementation, is characterised by high policy ambiguity and high policy conflict. The key determinant of the implementation outcome is the local level coalition strength. The strength of the coalition of local implementing actors with adequate resources to influence policy significantly. There is high policy ambiguity because the policies are symbolic and often abstract, vague and ill-defined in nature. Unlike experimental implementation, Matland noted that the strength of local coalitions shapes the outcome of the implementation.

Research design and method

The research used a case study design to collect and analyse qualitative data from multiple stakeholder organisations within the sport policy subsystem of Ghana. Yin (Citation2009,18) stated that the case study, in relation to data collection and analysis, ‘copes with the technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest…, relies on multiple sources of evidence…, benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis’. Considering that this research studied the relationship between policy and implementation involving multiple actors (Ragin Citation1992), data were collected from two overlapping sets of policy actors: (1) those primarily fulfilling policy making, supervisory or coordinating roles like the executive, ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs); and (2) those state and non-state organisations primarily concerned with implementation comprising the state subnational structures (regional and district offices), National Sport Federations (NSFs) and sport for development organisations.

Access and sampling strategy

After gaining approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), initial and formal contacts were made with participants from the aforementioned organisations on the two levels. Each of the participants was also issued with an informed consent form ahead of the interview. This was done through gatekeepers/mediators from the network that the first author has known in his past 10-year experience as both a sport administrator and researcher in Ghana. With regards to the policy making authorities the research used purposive sampling of senior government officials and policy makers given their expert knowledge of the SDGs policy implementation process in Ghana. Further, policy documents and reports were accessed online or requested from the policy making authorities (see ). With regards to the actors primarily concerned with implementation, purposive sampling was once again used to gain access to directors and senior officials from the National Sports Authority (NSA), Regional Sport Offices (RSOs), National Sport Federations (NSFs) and Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) organisations. However, two NSFs and two SDP organisations declined the requests for interviews without citing any specific reasons. Snowball sampling was used to access the coordinators from the District Sport Units (DSU). It is worth mentioning that until 2019, Ghana had 10 regions. Currently there are 16 regions but with limited structures in the additional six regions. The research therefore used state sports organisations from the previous 10 regions, specifically taken from the northern, mid, and southern parts of Ghana. This selection of regions was designed to ensure a balance of data sources in terms of urbanisation, wealth, population density and culture. See the full list of the interviewees in .

Table 3. Participants for semi-structure interviews.

Data collection

The data collection formed part of an ongoing research project which began in 2019. The research used multi-method data collection through document analysis, semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs). This allowed for triangulation in order to make a strong case for the research outcome (Bowen Citation2009). Details of the methods of enquiry are as follows:

Document analysis

Insights were drawn from policy implementation documents to analyse how sport has been captured and reported. They comprised both government and private documents (see for full details). Some of the documents were accessed online while others were requested from participants after interviews. In doing so, biased selectivity was checked, for instance, by ensuring that requested or provided documents served the purpose of the research rather than merely suiting research participants (Yin Citation2009). The research also followed Scott’s (Citation1990) four quality control principles of handling documentary sources which are data authenticity, credibility, representative and meaningfulness.

Table 2. Sourced documents.

Semi-structured interviews

The rationale for this type of interview was to understand the implementation process from the perspective of key government officials (DeJonckheere and Vaughn Citation2019). Due to the COVID-19 global pandemic participants preferences in relations to the interview mode were considered. Consequently, interviews were conducted digitally via Zoom or face-to-face (see for the full details). For the face-to-face interview the researcher adhered to the COVID-19 health and safety protocols in Ghana which included wearing a mask and maintaining the minimum distance of one meter (Government of Ghana Citation2020; Kenu, Frimpong, and Koram Citation2020). Interviewed participants were from policy making authorities and implementing organisations (see ). The interview guide for the policy making authorities covered areas about the measures put in place to ensure implementation nationwide, the engagement of implementing actors in the policy process and the role of sport in advancing the SDGs in Ghana. Research questions to the regional sport directors and senior managers from the NSFs and SDP organisations included their engagement with the sport ministry, collaborations, access to government resources and their contribution to the social objectives of the SDGs.

Focus group discussion (FGD)

Three FGDs were conducted as a complement to the semi-structured interviews in order to analyse the reliability of responses particularly from the regional sport directors. Overall, the purpose was to find out whether the policy goal of the SDG 3 through sport has been practical, understood and implemented. The discussions involved four to six District Sports Unit (DSU) coordinators/representatives (see ) who provided insights into the communities where they worked (Bryman Citation2012). Participants were given the flexibility to share their experiences. Additionally, given the political nature and the hierarchical order of the DSU, a neutral location for each of the three FGDs, was selected to allow participants to speak more freely (Elwood and Martin Citation2000). The FGDs were aided by an interview guide with similar objectives as the semi-structured interviews but with deeper frontline insights.

Reflexivity

Collecting data from a familiar context requires critical reflection regarding the researcher’s position. Additionally, it involves an ongoing process of self-disclosure and explanation (Dowling Citation2008). Being a Ghanaian (first author) who speaks multiple Ghanaian languages and with a previous work experience in Ghana, provided me with an ‘easier entrée, a head start in knowing about the topic and understanding nuanced reactions of participants’ (Berger Citation2015, 223). Nonetheless, the researcher’s position as an insider required attention to ethical dilemmas. Floyd and Arthur (Citation2012, 172) stated that, there is often the ‘deeper level ethical and moral dilemmas that insider researchers have to deal with once ‘in the field’. These dilemmas are; (1) to gain trust participants were invited to give informed consent prior to the interview and were also told that, their personal details would be anonymised throughout and after the research (Jacobsson and Åkerström Citation2013); (2) there was also the risk of neutrality that participants may want to discuss personal matters or other unrelated issues (Patton Citation2014; Mapitsa and Ngwato Citation2020; 3) the risk of projection bias by both the researcher and participant(s) was taken into consideration; (5) the researcher avoided assuming that the research participants were fully aware of the details of the SDGs as either a sport policy goal or cross-sectorial policy in Ghana; and (6) the researcher also paid critical attention to implied statements, incomplete sentences or use of non-verbal cues (like facial expressions and symbolic gestures) to signify certain meanings (Berger Citation2015). Here, I ensured the clarity of the questions asked in the interview while also probing participants to fully grasp their responses.

Data processing and analysis

The data analysed comprised the identified documents (in ) and interviews (semi-structured interviews and FGDs). The duration of the semi-structured interviews was from 40 to 60 minutes and the FGDs from 70 to 90 minutes. The interviews were transcribed verbatim. The transcribed data were manually and digitally analysed. The data processing began with familiarising ourselves with the data by thoroughly reading and re-reading through the data, making notes and forming ideas about coding. By using the MAXQDA Plus (2020), initial codes were extracted and labelled through the open coding method. The extracted codes were then linked together through axial coding to form meaningful organised categories (Gratton and Jones Citation2010). Thence, the organised categories were downloaded in excel format for manual analysis to generate main themes and sub-themes where necessary. In addition to the authors’ collective analytical efforts, the probing and feedback from peer debriefing helped to generate credible themes (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). The data analysis was undertaken both inductively and theoretically. By using the inductive approach, we engaged in data immersion, pattern matching and explanation building to generate common themes from the data (Yin Citation2009). The data from the document analysis and policy making authorities were inductively analysed to know how the government of Ghana had captured sport’s contribution to the social goals of the SDGs in its reports and policies. The theoretical approach, as the name denotes, adopted the coding strategy based on the theoretical lens used for the research. Thus, aided by Matland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Matrix of policy implementation, the following themes emerged; clarity and relevance of sport and SDGs as a policy goal; inclusivity of the policy implementation process; collaborations and interdependence among implementing actors; and policy implementation conflicts – here emerging themes were resource distribution, human resource capacity, reliance on football and discretion.

Findings

Policy making authorities’ commitment to sport and the SDGs

This section shows how the role of sport in achieving the SDGs is captured and reported by the Government of Ghana and state institutions that play supervisory and coordinating roles (see ) towards the implementation of the SDGs. At the Ministry of Youth and Sports one of the policy goals in connection to the SDGs is ‘to contribute to … the attainment of a healthy population through … sports’ (Ministry of Youth and Sport, 2020, 2). This goal serves as the basis for reporting the SDGs.

Stimulated by the United Nations’ MDGs, the emphasise on the social development role of sport was first captured in Ghana’s Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS II) (2003-2009) and Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDI-II) (2010-2017). However, the Ghana MDGs reports (2006, 2008, 2010 and 2015) published by the National Development Planning Commission of Ghana did not provide a single report on the actual social contribution of sport.

Following the UN’s categorical statement of sport as a significant enabler of ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ (UNGA (United Nations General Assembly) Citation2015, 3), the social role of sport, among other areas, has not only regularly appeared in Ghana’s development policies but its social significance has been noted in some national reports as shown below:

The Unit will aggressively seek to build new partnerships with educational institutions, traditional leaders, sporting organisations, and deepen its partnership with civil society organisations to expand its outreach. - 2019 SDGs Advisory Annual Report (page 37).

[The government will] provide more sports amenities and encourage the youth to engage in sporting activities. - 2019 Voluntary National Review (page 101)

We have considered sport in a number of ways. So, in the medium-term development framework the strategy and objective are to provide sports facilities and recreational facilities in all districts to promote the uptake of sports…, to revitalise the school sports programmes [such as] the inter colleges, community sports festivals, etc. to promote healthy lifestyle through what we call keeping active. We had also planned to partner with the GFA [Ghana Football Association] to try and see how we can use it to educate people on the SDGs and how best they can support the implementation. – Eris

Summarizing the above, the policy making authorities have shown commitment (in the form of strategy development and resource allocation) with regards to the role of sport in their efforts to meet the SDGs. Thus, illustrating Matland’s administrative category where goals are well-defined, and implementation takes a top-down model. The emphasis on partnership with sporting organisations and the social role of sport for community health and well-being are crucial but the government’s (through the sport ministry) approach towards implementation is more political. For instance, the sport ministry’s intervention in implementation in local communities to prioritise football indicates political implementation. It also shows that local implementing actors that are football-related like the Ghana Football Association will be more favoured.

Local level implementation

Symbolic implementation at the regional level

The regional sport directors (RSDs) interviewed agreed on the relevance of the sport to achieving the SDG 3 in general, but they did not hesitate to speak about the challenges that prevent them from contributing to the health of the people within the communities where they work. These challenges are their non-involvement in the implementation process, the lack of implementation guidance and the lack of financial and human resources.

With regard to the extent to which regional sports directors have been involved by the sport ministry and the National Sport Authority (NSA) in the implementation process and whether they have been provided with implementation guidelines typical comments were:

Specifically, we have not been involved by the NSA [National Sports Authority] and the sport ministry… The NSA and sport ministry do things the way they want, but not even according to our structures. So, it is a big challenge for us. – RSD 1

We had meeting about the SDGs and they (MOYS and NSA officials) said they are going to start the implementation but up until now there is no action taken. [So] I am working within my own strengths, till they come out with detailed guidelines. – RSD 2

We have a quota from government, but we have never received that quota from the government. – Regional Sport Officer 3

We concentrate so much on football in this country. In fact, two Black Stars matches can consume the whole budget for the year. So, it is in our small way that we are doing things. It is difficult to actually hit the [SDGs] targets. – RSD 2

Apart from [one of the] district sport units (DSUs) where we have NSA staff, we do rely on GES (Ghana Education Service) PE coordinators in the districts. For instance, when we organise inter-district sport festivals, we rely on them. – RSD 1

For the mass sports we rely on sponsors that help us facilitate health and keep fit activities. We do liaise with individual keep fit clubs and regional health centres. Also, we partner with FM stations and MMDAs/DSUs to organise health walks and marathons. - RSD 3

Political implementation at the district level

The activities of the District Sport Units (DSUs) are supposed to be funded under the social services section of the District Assembly Common Fund (DACF). A thorough search of the parliamentary annual authorised ‘formula for sharing the DACF’ from 2016 to 2020, indicated that although sport is an approved area under the social services section of the DACF, the allocation of funds meant for sport is not mandatory. The allocation is based on the discretion of the district chief executive officers. Unlike sport, it is worth pointing out that, the fund allocations to other social service areas like disability, education, disaster management and housing are mandatory and clearly defined.

The DSU is where policy translates into actions. Those interviewed were frontline implementers comprising district sport community coordinators/coaches and PE Coordinators from the Ghana Education Services. They spoke about health issues, lack of resources, non-involvement and over concentration on football. They believed that without their services the health of the people in the communities will worsen if both the Ministry of Youth and Sport and the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) continue to neglect their contributions.

When asked about the health issues that they encounter while working with people within their respective communities they mentioned issues associated with breathing (particularly asthma), malaria and ulcers due to prolonged hunger or bad nutrition. They remarked that all the health issues they encounter need medical attention and assessments. They also mentioned that the dusty playing fields either cause or exacerbate respiratory problems that they encounter. Additionally, they also stated that the ill-equipped and bad playing fields have caused injuries among young people who participate in their programmes:

I think there is also dusty fields which to me I think it causes asthma and difficulty in breathing. – DSU Group 1

Another key health challenge is the lack of good equipment, and bad playing fields. If you come to the [playing fields in my district], the ground is as hard as stone… It is very rough, bad state facilities and playing fields are poor and stony – DSU Group 2

I challenged the district authorities some time ago and I told them that we are aware that 2% or 5% of the [District assembly] Common Fund is for sports. But when we present our budget, we follow it up million times before a token is given in support of our sports. At times they didn’t even mind me. It is hell. – DSU Group 3

You see this is an African country, if you push, [the district authorities] will send you home… as we sit down here as individuals, we cannot take any decision until our leadership asks for our input but they don’t. – DSU Group 2

The politics in sports is too much. … On certain occasions, the [district] assembly authorities purchase equipment like jerseys, footballs and whatever and they go to the various villages giving it out to clubs without involving us. – DSU Group 3

If our authorities know very well, they will channel most of the money to physical activities and sports within communities and we will do away with a lot of the diseases and illnesses. That is where the national health care cost will reduce. But everything is centered on soccer. – DSU Group 1

[My district] is in collaboration with Breast Cancer International to organise health walk. They bring their doctors to conduct free screenings… At times the diseases are detectible and once detected then they help. There is also Marcot Surgicals Limited, that sponsor us with sanitary pads for girls and women. – DSU Group 3

There is Right to Play and sometimes they come with a lot of learning materials like their game manuals and equipment like footballs, jerseys and others. They give them to the various[district] schools. Sometimes, they organise workshops for the schoolteachers and we will monitor their activities. – DSU Group 2

In sum, the quotes from district sport unit implementers typify Matland’s political implementation category where policies are well-defined but operate in the context of high conflict due to over-reliance on football activities, inadequate or no funding, and non-involvement of the frontline implementing actors. These create an implementation deficit where frontline implementers, who regularly translate policy into action, are either disregarded or neglected. In effect, the discretion and autonomy of the frontline implementers to cope with policy delivery uncertainties (like scarce resources) which may ultimately shape public policies may go overlooked (Lipsky Citation1980). The disregard of the roles of the frontline implementer is further illustrated among the national sport federations and the sport for development and peace organisations below.

Political implementation with national sport federations

The National Sport Federations (this includes some para-associations) have regional sport structures with district clubs that engage young people in the communities. Even though they are federated under their respective international sport federations, they pointed out that the government has ignored their contribution to national development.

The federations state that as compared to the Ghana Football Association/football which receives hefty portion of government funding, all other national sport federations do not receive such support:

Through our regional leagues in the districts we contribute a lot in terms of player development, young athletes becoming healthy and paying medical bills. And so, hopefully within the next five to 10 years, we should start seeing a shift of mindset towards other sports aside [from] football. – Ceres

Disable sport associations provide yearly programmes to the NSA and sport ministry, yet, we are neither financially supported nor recognised. But when it comes to the physically disabled sport the sports ministry supports their amputee football more, over the last five years. –Makemake

Symbolic implementation with sport for development and peace (SDP) organisations

Of the over 6000 NGOs operating in Ghana it is not known precisely how many use sport as a primary strategy and would qualify as SDP organisations. However, it was clear from the interviews that sport is a primary or secondary vehicle for addressing social issues for a large number. The Youth Development through Sport (YDS) coalition of SDP organisations in Ghana has been instrumental in the use of sport to address health outcomes like the SDGs. The programmes and activities of the SDP organisations are not unknown to the sport ministry because both the 2016 Sport Act 934 of Ghana and the SDGs policies recognises them as strategic partners towards national development. The four members of SDP organisations that were interviewed work for self-funding local NGOs at the grassroots level. The participants that were interviewed from SDP organisations mentioned that the SDG 3 is relevant and integral to their work in the communities but also pointed out the lack of collaboration and recognition from both the district assemblies and the sport ministry.

With regards to health (SDG 3) their programmes have focused on HIV AIDS, malaria, mental health and girls and women’s health issues:

Basically, we focus a lot on HIV/AIDS and malaria. And I'm sure you are aware of how deadly malaria is in our side of the world. We also have a girl empowerment and health programme that we run. – Haumea

We look at general health and fitness since every child growing up needs to play and be active. We also run mental health campaigns for children from broken homes and our volunteers comprising university students struggling with anxiety and depression issues from their studies. – Orcus

Government should use organisations like ours, because we are non-governmental and not political. The things we can achieve together may be bigger than what government, through the ministries and MMDAs, can do. If government really wants to achieve something that is universal, then they should be involving us. – Sedna

Resources and funding are considerations but what we really must look at are legitimacy, promotion and recognition. The recognition of SDP organsations is very crucial towards the growth of SDP sector. It is sad the lack of needed recognition. – Gonggong

Our strategy is to partner organisations like ours that have some things that we need. For instance, Right to Play assists us with capacity building programmes. Right to Dream absorbs most of our girls into their football academy. Alive and Kicking supports our health outreach programmes like HIV/AIDS and malaria through football. - Haumea

Discussion and conclusion

The above findings illustrate the intricacies of the policy-implementation nexus frequently cited in the public policy literature. Can the government’s commitment to the SDGs simply be a political strategy for Ghana’s image or to ensure continued funding from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) which gives concession to low and middle-income countries (LMICs) implementing the SDGs? Generally, the findings reveal weaknesses in the policy implementation of SDG 3 through sport due to the gap between government policy statements and practice, that is, what government seeks to do as against what government is actually doing. We will therefore discuss the challenges that accounted for the SDG health and sport policy-implementation gap through the lens of Matland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Matrix of Policy Implementation. These challenges comprise the lack of resources, the non-involvement of local implementing actors, clientelism due to football’s overbearing importance, the legitimation of SPD organisations. The implications for sustainability and similar research around the world will be discussed. Additionally, we reflect on the utility of Matland’s typology and discuss its strength and weaknesses in relation to the research findings. The concluding part makes recommendations for further research.

In line with Matland’s typology, the research findings showed that the policy implementation related to the health of the Ghanaian population (SDGs 3) through sport is predominantly political at both the policy making and local implementing levels although there were instances at the regional level that showed elements of symbolic implementation. As noted in the findings, the SDGs as a policy goal are well-defined, however the symbolic-political implementation indicates high conflicts over the means of implementation. For instance, the resources available for the actual implementation are unevenly distributed and often politicised by leading government actors at the sport ministry and the district assemblies. Hence, conflict over the means of implementation where the decisions of the frontline implementing actors are misaligned with the stated policy goals. For instance, since government officials from the sport ministry and the district assemblies have taken over the actual implementations of the SDGs in ways that they deem fit, the local implementing actors from the regional and district sport offices follow their ‘own missions’ (Matland Citation1995, 164).

Additionally, conflict over means of implementation occurred due to the unavailability and skewed distribution of funding, the lack of implementation guidelines and sufficient human resources for successful implementation. As a result, mistrust among the local implementing actors could impede successful implementation. We argue that, to have significant impact on successful implementation, government has to ensure regular and appropriate distribution of funds to regional sport offices, provision of sufficient human resource at the local district level and an inclusive policy implementation process.

Further, conflicts among local implementing actors as described occur in the form of clientelism where some groups are favoured over others. Clientele relationships between the sport ministry and the Ghana Football Association (GFA) as well as between district assemblies and certain community groups (that engage in football related activities) permeates the findings. The prioritisation of football illustrates the political clientelism described by Stoke (Citation2011) as ‘programmatic redistributive politics’ where politically elected officials in government draw policy resources to favour certain groups for canvassing and political support. The leverage of football’s popularity for political reasons, as revealed creates asymmetrical relationships among the implementing actors (Lemarchand and Legg Citation1972). What may ensue is that a large number of actors may be neglected, and the wider impact of development may not be attained (Van de Walle Citation2014). For instance, despite the UN’s 2030 Agenda for the SDGs emphasis on mobilising resources from non-state actors to complement governments efforts, the SDP particularly sector relevant to health have neither been utilised nor captured in the reports of the sport ministry. The SDP sector entails diverse community-based NGOs offering various social services which complements government’s efforts in the local communities.

The symbolic-political implementation issues discussed also undermines the social significance of sport and hence the sustainability of health outcomes. In reference to Lindsey’s (Citation2008) concept of sustainability: government, through its institutions, must ensure frequent and equitable distribution of resources to implementing actors; avoid the clientelistic tendencies that cause disparities among implementing actors; legitimise and recognise SDP organisations as strategic partners in order to ‘strengthen community capacity’ (ibid., 282); and ultimately work with local implementing actors to make a well-defined implementation guide tailored to needs of communities.

A study funded by the Commonwealth Secretariat which has involved 71 countries since 2017 showed evidence of ‘sports policies identified as development objectives’ linked to specific SDGs (Sherry et al. Citation2019, 13). In recent studies, (country-specific) SDGs and sport policies have been analysed (Lindsey and Darby Citation2019; Moustakas and Işık Citation2020; Campillo-Sánchez et al. Citation2021). The studies provide evidence for vertical policy coherence of SDGs and sport policies between national and international organisations. Despite this, the research findings also noted the need to improve and carefully examine horizontal policy (in)coherencies involving sport NGOs and government institutions at the local level. Campillo-Sánchez et al. (Citation2021) study on Sports and SDGs in Spain for instance found that there are inconsistencies in ‘alliances, the exchange of experiences and roles between the different actors (state and nonstate)’ (p. 14). A similar conclusion was reached in the research conducted by Moustakas and Işık (Citation2020) about Botswana, which revealed policy weaknesses which included a lack of stakeholder engagement, limited community sport facilities, no concrete implementation plan and overwhelming financial support for football. These challenges show a similar pattern to those identified in this study. By failing to utilise or analyse the opportunities that policy coherence offers, local implementation actors may act at their discretion or pursue divergent paths, as shown by this study.

In general, Matland’s Ambiguity-Conflict Matrix of Policy Implementation was a useful analytical tool as it incorporates elements of top-down and bottom-up implementation, rather than seeing them as alternative approaches. The four different implementation categories, their characteristics and the conditions under which these characteristics affect the success of policy implementation provided a valuable ideal type against which Ghana’s experience could be assessed and analysed. Thus, it provided the analytical grounds to substantiate the call for scrutiny regarding expressions of sport as a cost-effective low risk policy tool or magic wand used by governments to solve wide range of social problems (Coalter Citation2010). The Matrix nonetheless would benefit from being used in combination with other theories of the policy process (such as the Advocacy Coalition Framework or the Multiple Streams Framework) to better explain how power is exercised by policy actors.

To conclude, we want to re-emphasise on the importance of the SDP sector which has gained global momentum and have appeared in many national policies (Sherry et al. Citation2019). Despite the presence of many SDP organisations in various local communities of Ghana, there have been little research covering their contributions to sustainable development particularly related to health. Therefore, we recommend further research to explore how the SDP actors organise themselves and mobilise (finance) resources to contribute to sustainable development despite being excluded from government-led policy implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- African Union. 2008. Policy Framework for the Sustainable Development of Sport in Africa (2008-2018). Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Agou, G., F. Lima, J. Ralyea, C. Verkoren, A. Mugnier, C. Ndome-Yandun, and J. Vibar. 2019. “Ghana - Selected Issues Paper.” IMF Country Report No. 19/368. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Berger, R. 2015. “Now I See It, Now I Don’t: Researcher’s Position and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 15 (2): 219–234. doi:10.1177/1468794112468475.

- Bowen, G. A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40. doi:10.3316/QRJ0902027.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Burnett, C. 2021. “Framing a 21st Century Case for the Social Value of Sport in South Africa.” Sport in Society 24 (3): 340–355. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1672153.

- Campillo-Sánchez, J., E. Segarra-Vicens, V. Morales-Baños, and A. Díaz-Suárez. 2021. “Sport and Sustainable Development Goals in Spain.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3505. doi:10.3390/su13063505.

- Charway, D., and B. Houlihan. 2020. “Country Profile of Ghana: Sport, Politics and Nation-Building.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 12 (3): 497–512. doi:10.1080/19406940.2020.1775677.

- Coalter, F. 2010. “The Politics of Sport-for-Development: Limited Focus Programmes and Broad Gauge Problems?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 45 (3): 295–314. doi:10.1177/1012690210366791.

- Craig, Patricia J., Bob Barcelona, Semra Aytur, Jess Amato, and Sarah J. Young. 2019. “Using Inclusive Sport for Social Change in Malawi, Africa.” Therapeutic Recreation Journal 53 (3): 244–263. doi:10.18666/TRJ-2019-V53-I3-9720.

- DeJonckheere, M., and L. M. Vaughn. 2019. “Semistructured Interviewing in Primary Care Research: A Balance of Relationship and Rigour.” Family Medicine and Community Health 7 (2): e000057–8. doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000057.

- Delva, W., K. Michielsen, B. Meulders, S. Groeninck, E. Wasonga, P. Ajwang, M. Temmerman, and B. Vanreusel. 2010. “HIV Prevention through Sport: The Case of the Mathare Youth Sport Association in Kenya.” AIDS Care 22 (8): 1012–1020. 10.1080/09540121003758606.

- Dowling, M. 2008. “Reflexivity.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by L. M. Given, 747–748. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- ElMassaha, S., and M. Mohieldinb. 2020. “Digital Transformation and Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).” Ecological Economics 169 (106490): 106490. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106490.

- Elwood, S. A., and D. G. Martin. 2000. “Placing” Interviews: Location and Scales of Power.” The Professional Geographer 52 (4): 649–657. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00253.

- Floyd, A, and L. Arthur. 2012. “Researching from within: External and Internal Ethical Engagement.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 35 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2012.670481.

- Geiger, M., J. Trenczek, and K. M. Wacker. 2019. “Understanding Economic Growth in Ghana in Comparative Perspective,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 8699 prepared by the World Bank Group, Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice.

- Government of Ghana. 2020. Ghana Imposition of Restrictions Act, 2020: Imposition of Restrictions (Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic) Instrument. Government Gazette.

- Gratton, C., and I. Jones. 2010. Reserach Methods for Sports Studies. 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- GSS (Ghana Statistical Service). 2017. Data Production for SDG Indicators in Ghana. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Hansell, A. H., P. R. Giacobbi, and D. K. Voelker. 2021. “A Scoping Review of Sport-Based Health Promotion Interventions with Youth in Africa.” Health Promotion Practice 22 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1177/1524839920914916.

- Houlihan, B. 2009. “Mechanisms of International Influence on Domestic Elite Sport Policy.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 1 (1): 51–69. doi:10.1080/19406940902739090.

- Hushie, M. 2016. “Public-Non-Governmental Organisation Partnerships for Health: An Exploratory Study with Case Studies from Recent Ghanaian Experience.” BMC Public Health 16 (963): 963–913. 10.1186/s12889-016-3636-2.

- Ibrahim, M., and I. P. Alagidede. 2020. “NGOs Activities and Local Government Spending in Upper West Region of Ghana: are They Complements or Substitutes?” International Review of Philanthropy and Social Investment 1 (1): 73–86. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1f2128e4ec. doi:10.47019/IRPSI.2020/v1n1a6.

- Kumi, E. 2017. “Diversify or Die? The Response of Ghanaian Non–Governmental Development Organisations (NGDOs) to a Changing Aid Landscape.”, PhD Thesis., University of Bath, UK.

- Kenu, E., J. A. Frimpong, and K. A. Koram. 2020. “Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ghana.” Ghana Medical Journal 54 (2): 72–73. 10.4314/gmj.v54i2.1.

- Jacobsson, K., and M. Åkerström. 2013. “Interviewees with an Agenda: Learning from a ‘Failed’ Interview.” Qualitative Research 13 (6): 717–734. doi:10.1177/1468794112465631.

- Keim, M., and C. de-Coning. 2014. Sport and Development Policy in Africa: Results of a Collaborative Study of Selected Country Cases. Cape Town: ICESSD, University of the Western Cape.

- Lemarchand, R., and K. Legg. 1972. “Political Clientelism and Development: A Preliminary Analysis.” Comparative Politics 4 (2): 149–178. doi:10.2307/421508.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Lindsey, I. 2008. “Conceptualising Sustainability in Sports Development.” Leisure Studies 27 (3): 279–294. doi:10.1080/02614360802048886.

- Lindsey, I., and D. Banda. 2011. “Sport and the fight against HIV/AIDS in Zambia: A ‘partnershipapproach’?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46 (1): 90–107. doi:10.1177/1012690210376020.

- Lindsey, I., and B. B. Bitugu. 2018. “Distinctive Policy Diffusion Patterns, Processes and Actors: Drawing Implications from the Case of Sport in International Development.” Policy Studies 39 (4): 444–464. doi:10.1080/01442872.2018.1479521.

- Lindsey, I., and P. Darby. 2019. “Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the Policy Coherence?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 54 (7): 793–812. doi:10.1177/1012690217752651.

- Lipsky, M. 1980. Street Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Mapitsa, C. B., and T. P. Ngwato. 2020. “Rooting Evaluation Guidelines in Relational Ethics: Lessons from Africa.” American Journal of Evaluation 41 (3): 404–419. doi:10.1177/1098214019859652.

- Matland, E. R. 1995. “Synthesizing the Implementation Literature: The Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 5 (2): 145–174. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242.

- Ministry of Finance. 2019. Ghana’s SDG Baseline Report. Accra: Ministry of Finance. Ghana’s-SDG-Budget-Baseline-Report-Aug-09-18.pdf (mofep.gov.gh)

- Ministry of Finance. 2019. Ghana’s SDG Budgeting Manual. Accra: Ministry of Finance

- Minstry of Youth and Sports 2016. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2016-2018. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Minstry of Youth and Sports. 2017. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2017-2019. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Minstry of Youth and Sports. 2018. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2018-2021. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Minstry of Youth and Sports. 2019. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2019-2022. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Minstry of Youth and Sports. 2020. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2020-2023. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Minstry of Youth and Sports. 2021. Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2021-2024. Accra: Ministry of Finance.

- Moustakas, L., and A. A. Işık. 2020. “Sport and Sustainable Development in Botswana: Towards Policy Coherence.” Discover Sustainability 1 (1): 5. doi:10.1007/s43621-020-00005-8.

- Mwaanga, O. 2010. “Sport for Addressing HIV/AIDS: explaining Our Convictions.” Leisure Studies Association Newsletter 85: 61–67.

- NDPC (National Development Planning Commission). 2019. Ghana: Voluntary National Review Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Cantonments, Accra: National Development Planning Commission.

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ragin, C. C. 1992. “Casing” and the Process of Social Inquiry.” In What is a Case? edited by C. C. Ragin, and S. B. Howard, 217–226. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scott, J. 1990. A Matter of Record: Documentary Sources in Social Research. Cambridge: Polity.

- SDGs Advisory Unit. 2021. SDGs Advisory Unit Annual Report 2019. Accra: SDGs Advisory Unit, Office of the President of Ghana.

- Sherry, E., C. Agius, C. Topple, and C. Clark. 2019. Measuring Alignment and Intentionality of Sport Policy on the Sustainable Development Goals. London: The Commonwealth.

- Stoke, S. 2011. “Political Clientelism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Science, edited by R. E. Goodin, 648–674. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0031.

- TheGlobalEconomy.com. 2020. Political Stability in Africa. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_political_stability/Africa/

- UNGA (United Nations General Assembly). 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution A/RES/70/1 adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. New York United Nations.

- Van de Walle, N. 2014. “The Democratization of Clientelism in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Clientelism, Social Policy, and the Quality of Democracy, edited by D. A. Brun, and L. Diamond, 230–252. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage.