Abstract

Recent academic focus has been on reducing the sex data gap for women in sport and exercise research. However, ‘women in sport’ is often narrowly represented by female athletes/participants, though there are numerous other positions in sport which are also threatened by a sex data gap. In this paper, we propose a six-pillar framework of sport to draw attention to the key areas that women can contribute to within a sporting organisation. In this paper we cover the current state of play of female participation across these pillars, identify some of the challenges and implications of women being a minority, and look at the benefits of taking a wider whole-of-sport approach to women in sport beyond just as participants. By conceptualising women in sport across this wider sporting context, we encourage readers to avoid ‘gender blindness,’ and we provide specific recommendations to help raise the profile of women in sport.

Introduction

In the past 25 years, there has been an exponential growth in women’s sport, particularly women’s elite sport. Alongside this, there has been a concerted academic focus on the sex data gap in sport and exercise science (Cowley et al. Citation2021) and a call for increased female participants and female-specific research studies (Bruinvels et al. Citation2017). This has, more widely, contributed to an improved cultural awareness of the unique physiology of females, which has traditionally been overlooked in male-centric sporting spheres. Given the history of women in sport, these social and cultural changes demonstrate that ‘there has been no better time to be a female athlete’ (Lampoon Group, Citation2021, para 11). Despite this, the idea of ‘women in sport’ is often narrowly represented as female athletes, particularly elite female athletes. This myopic attention on women as sportspeople neglects the numerous other ‘non-playing’ positions which women may occupy in both men’s and women’s sport – including coaches, officials, academics, and support staff – which are equally threatened by the sex data gap in research. It is important to acknowledge that while there has been significant advancement in ‘women’s sport’, there has been a stagnation of ‘women in sport’ (Palmer Citation2019). To comprehensively raise the profile of women in all areas of sport, we must consider the broader realms of their involvement, aside from, or in addition to, their involvement as athletes. In this piece, we discuss the importance of (a) conceptualising women in sport across the wider sporting context, emphasising the diversity of available roles, and (b) the need for a wider scope of research to better understand the experience of ‘women in sport’ beyond the female athlete. In doing so, we call on researchers, practitioners, and sporting organisations to carefully consider and evaluate the barriers and facilitators influencing women’s involvement across six pillars of sport. This change in perspective offers practical value as a form of public sociology, contributing to an improvement in the equity of sport as a whole (Donnelly Citation2015).

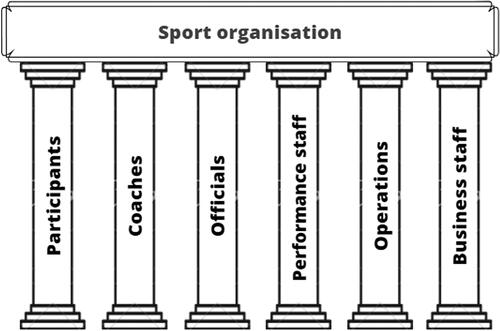

The theory and practice of ‘whole system working’ described by Pratt, Gordon, and Plamping (Citation2005) encourages a shift from thinking about the different ‘parts’ of an organisation or issue, to thinking about the connection between parts and therefore the ‘whole’. Similarly, we should approach the advancement of women in sport from a whole system perspective, recognising and drawing upon the experiences of coaches, officials, academics, and support staff, as well as athletes. To conceptualise this in a sports context, we propose a six-pillar framework of sport () which forms the foundation of modern sports organisations, and which ultimately supports the performance of athletes or teams. These pillars include participants (athletes and research participants of all levels, from grassroots to elite); coaches (all levels and domains of the sport); officials (umpires, referees, ground staff); performance staff (sports scientists, analysts, researchers, and talent scouts); operations (internal management and board members) and business staff (media and marketing staff). These pillars are not static; one individual may transition or operate in different roles or areas, and the composition of these areas differs between organisations. However, this framework is intended to draw attention to the six key areas that women (and men) can contribute to within a sporting organisation or business.

Current state of play

In conceptualising ‘women in sport’ from a whole-of-sport perspective, an important first step is recognising the unequal gender composition of sport positions overall; however, it should be noted that much of the available data presented here describes the status of able-bodied women in sport in middle to high-income countries (Memon et al. Citation2022), and therefore does not constitute a true ‘global’ state of play.

First, women as participants historically receive the greatest focus by science, media, and government organisations. In recognition that sport participation confers lifetime physical and mental health benefits, this pillar of sport has been approaching a more even gender balance in recent years. However, from a global perspective, insufficiently active women still outnumber men (32% of women vs 23% of men), likely a reflection of cultural and gender norms that continue to limit women’s access to safe and active leisure time worldwide (Guthold et al. Citation2018). Meanwhile, at an elite level, widespread disparities in salaries, funding, or prize money likely contribute to fewer elite female athletes remaining within sport long-term. This pillar of sport also recognises the involvement of women as participants in sport and exercise research, where they continue to be underrepresented (Cowley et al. Citation2021). This may be partly due to the assumption that female participants add a methodological challenge to investigations due to fluctuating hormonal profiles (Cowley et al. Citation2021); although it could also be an outcome of there being more male researchers within sport and exercise science.

In almost every sport globally, the proportion of coaches who are women is a statistical minority (Acosta and Carpenter Citation2012). Only 13% of coaches at the ‘most gender equal [Olympic] Games of all time’, the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, were women (International Olympic Committee, Citation2021), reflecting a significant disparity in the gender of high-performance coaches worldwide. In Australia, the balance of women coaches appears to be trending upwards (38% in 2016, 44% in 2018; Eime et al. Citation2021) and is comparable to the United States (35%; Acosta and Carpenter Citation2012). Notably, women coaches overwhelmingly coach women’s sports – only 3.5% of men’s sports in the US collegiate system are coached by a woman (Acosta and Carpenter Citation2012), and women have poorer representation in traditionally masculine sports (Women’s Sport Foundation Citation2019).

Sports officials are a vital non-playing role that includes umpires, referees, administrators, and judges who maintain order and adjudicate contests (Mergler Citation2019). In Australia, 43% of adult officials in 2020 were women (AusPlay Citation2020), the vast majority of whom are likely to be unpaid volunteers (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2013). This is greater than figures reported for Canada (29% women) and the United Kingdom (11%), though data is outdated (Baxter, Kappelides, and Hoye Citation2021). Importantly, women are drastically outnumbered as professional referees and umpires in both men’s and women’s elite sport (NASO Citation2017).

Performance staff is a broad pillar encompassing sports scientists, analysts, and academic researchers. In Australia, this workforce is predominantly male (76%), with women making up less than 20% of high-performance managers and 37% of sport scientists (Dwyer et al. Citation2019). The proportion of women in high performance roles is demonstrating a downward trend (Sport Australia Citation2017), and may reflect ‘systemic problems with the typical employment conditions found in the profession’ (Dwyer et al. Citation2019, p. 229). In academia, the percentage of female first author publications by fourteen leading sport science journals has increased by ∼0.5% annually for the last 20 years, yet remains below 25% of all articles published (Martínez-Rosales et al. Citation2021). The low representation of women on journal editorial boards (<20%, Martínez-Rosales et al. Citation2021) and the prevalence of all-male panels at research conferences also underline the ‘highly complex, structural problem’ of implicit bias in this field (Bekker et al. Citation2018, p. 1287). This bias continues to perpetuate the exclusion of women from professional forums and has implications for the direction and implementation of current and future research (Martínez-Rosales et al. Citation2021).

Within sport operations, there is a distinct lack of female representation across boards of governance and internal management, and therefore, female leadership at an executive level. The latest research indicates that, globally, women have the least representation as board chairs (11%), but slightly greater (though still poor) representation as chief executives (16%) and board directors (20%) in sport organisations (Adriaanse Citation2016). This is still significantly less than the ‘critical mass’ of 30% of women needed to positively influence firm performance (Joecks, Pull, and Vetter Citation2013), which only four countries out of 45 audited have achieved (Adriaanse Citation2016). At an international level, only 27% of National Olympic Committee executive boards have met or exceeded an International Olympic Committee (IOC) minimum target of 30% female representation (IOC, Citation2022).

Finally, an area of sport which is often overlooked is the representation of women in business staff (including media and marketing), which are key supporting roles that frame how athletes and teams are depicted and constructed in mass media. While figures for marketing and content creation roles are unknown, sports journalism continues to be a ‘man’s world’ – only 5% of members in the UK-based Sports Journalists’ Association are women, contributing just 8% of sports articles worldwide (Price Citation2015). While women are well represented in undergraduate journalism courses, sports journalism courses attract just 7% women (in the UK) – indicative of distinct gender barriers that continue to discourage women from studying in this field (Price Citation2015). This lack of gender diversity clearly plays a large part in how women’s sport is portrayed – usually as ‘less important, less exciting and, therefore, less valued than men’s sports’ (Hovden and von der Lippe Citation2019, 627).

Challenges and opportunities for women in sport

The widespread lack of female representation in all six pillars of sport reinforces a powerful male hegemony and ensures the continued portrayal of women as a minority group or outsiders in sport (Fink Citation2008; Tingle, Warner, and Sartore-Baldwin Citation2014). For many women, this plays out in the gendered barriers they may encounter day-to-day, such as inadequate changeroom facilities, ill-fitting or inappropriate uniforms, discrimination, workplace incivility, gendered aggression, and sexist attitudes (Baxter, Kappelides, and Hoye Citation2021; Women’s Sport Foundation, 2020; Tingle, Warner, and Sartore-Baldwin Citation2014). In today’s age of social media, these challenges are quick to be publicized and reconciled when they occur to women athletes, e.g. changes to maternity policies for sponsored female runners following high-profile claims of lack of maternity protections (Felix Citation2019). However, a focus on siloed solutions rather than whole of sport approaches to improve the experiences of women in sport misses the big picture.

Recognising that there is more to ‘women in sport’ than just female athletes is a small, but firm, step towards increasing female representation in all six pillars of sport. This awareness of women’s varied roles advances the perception of ‘women in sport’ from a siloed focus on female athletes, to a growing awareness of female coaches, officials, performance, operations, and business staff, and an awareness of gender diversity or lack thereof of each pillar. Women’s sport research, for example, would benefit from a wider scope that explores the barriers and facilitators to women’s involvement within and across these pillars at micro, meso, and macro levels. Equally, the process of evaluating initiatives that result from such research should be conducted broadly, looking at potential flow-on effects across pillars and how these can be leveraged. For example, two national broadcasting networks in Australia and the UK have implemented 50:50 programs aimed at equal representation of women media contributors and news stories on women (ABC Citation2021; BBC Citation2022). In addition to increasing the number of women in media and marketing roles within sport, it may also increase female sport participation, including coaching, officiating, and leadership. While perhaps it is difficult to directly capture the impacts of these actions outside of the immediate pillar it sits, recognising and attempting to quantify this information can be important for understanding the broader success of these actions and direction for future programs.

Increasing female representation across the six pillars offers a range of benefits to organisations, such as reduced incidences of workplace sexual harassment (Au, Tremblay, and You Citation2020), improving negative stereotypes about females in sport (Diedrich Citation2020), reduced human resource and financial problems (Wicker, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2022), and greater management support for gender equity (Spoor and Hoye Citation2014). Fundamentally, increased female representation (and thereby, increased gender diversity) makes both business and ethical sense to a) fairly represent the stakeholders and participants of the sport itself, and b) increase the talent pool for future leadership opportunities (Adriaanse Citation2016). It is not possible to satisfy a growing women’s sport market without input from women themselves; more so, it is not possible to sustain female representation without creating a pipeline of females with leadership potential.

Case study: Australian rules football

Recent developments in the Australian Football League (AFL) illustrate how considering the state of women in more than one sporting pillar can inform strategic policy and planning across the whole sport for deeper systemic change. Understandably, the focus of the first 5+ years of the new AFL Women’s competition was on the development of players and the competition structure. However, while participation in women’s football has increased substantially (Burke, Klugman, and O’Halloran Citation2022), women make up only 28% of AFL club board members (Women on Boards Australia Citation2021) and less than 11% of all umpires (<3% at professional level) (Rawlings and Anderson Citation2021) Out of 18 elite women’s teams, only three have female head coaches, while there are currently no female head coaches in the elite men’s game (Brown and Christian Citation2022). Less is known about women’s participation in the pillars of officiating, operations and performance support, though the presence and contribution of women in business (specifically media and marketing roles) in both men’s and women’s Australian football is becoming more prominent (Lennon Citation2013). This will likely be bolstered by a new broadcast agreement that see all AFLW games televised from 2025 (Twomey, 2022). Likely, this improved media coverage of the AFLW will assist in improving the playing conditions and pay for athletes via increasing sponsorship and match attendance, in turn inspiring more girls to participate in the sport (Jones Citation2022). However, given the low participation rates of women as umpires, coaches, and board members, taking a whole of sport approach is important to understand and improve the landscape for women in Australian football.

A recent report highlighted female Australian football umpires’ experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and harassment (Rawlings and Anderson Citation2021). The report’s recommendations, while specific to umpiring (Rawlings and Anderson Citation2021), have helped inform the AFL Women and Girls Game Development Action Plan, addressing women’s participation across all aspects of football (playing, coaching, umpiring, administration) (Guardian Sport Citation2022). This deliberate, multidimensional approach to improving female participation within and across football differs from a ‘trickle-down’ approach, which has not previously been effective for improving gender diversity in sports governance (Wicker and Kerwin Citation2022) or participation (Frick & Wicker, 2015). While gendered barriers still persist in the traditionally male-dominated sport of Australian football, Richards, Litchfield, and Osborne (Citation2022) recently highlighted the overall positive experiences of females working in Australian football, demonstrating a progressive shift and acceptance of women in various roles including umpiring, finance, management and journalism. Increasing women’s playing participation is still an important element in policy and planning; however, this case study underlines the importance of including the voices of women in other roles and their unique considerations to acknowledge the broader female experience, and how the relationships between roles contribute to the overall culture of the sport.

Conclusion

The exponential growth of ‘women’s sport’ is to be celebrated. However, we cannot be complacent that female athletes encapsulate all ‘women in sport’; there is much to be said for women as coaches, officials, performance staff, operations staff, and business staff. Each of these pillars of sport is worthy of investment, focus, and development to raise the profile of women in sport as a whole. It is important to acknowledge that the existing gender order in sport is not a time-lag problem that will correct itself; it is a ‘socially constructed power relation that [can] be challenged and changed’ (Adriaanse Citation2016, p. 151).

Organisations which show the greatest improvement in female representation are those that demonstrate a clear, ambitious, and measurable commitment to effective action – for example, through gender quotas and compliance measures – rather than projecting ‘token equality’ (Piggott and Matthews Citation2021). Clearly, no single solution will suit all sport organisations; a bespoke approach that considers the social, emotional, and cultural nuances within individual sports and countries is needed. Therefore, we suggest the following practical recommendations for those who work in sporting organisations or any of the six pillars of sport:

Perform an organisation gender ‘health check’, which may include analysis of gender balance and pay gap (if relevant), reviewing flexible work and parental leave policies and determining organisational goals/targets, such as increasing the number of women in leadership roles. Consider all pillars in a whole system focus.

Understand the barriers and facilitators that may influence a woman’s decision to work/volunteer in your organisation within any pillar and consider how these might be addressed.

When planning and conducting research in sport, consider the broad spectrum of female involvement (inclusive of female researchers), regardless of the main research question. For research focused on females across pillars, consider:

Investigating the barriers and facilitators to participation, including females working within male sport.

Reporting key data on sex-based differences in sporting experiences, e.g. the transition from athlete to coach.

These immediate actions underscore an ongoing focus and longer-term examination of women in sport, which will ultimately benefit the industry as a whole. Women are not only sport participants; they are coaches, officials, performance staff, operations, and business staff, who provide networks of support for each other. Now is the time to consider changing the face of sport, and women in sport.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

References

- ABC 2021. 50:50 The Equality Project. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney. https://about.abc.net.au/5050-the-equality-project/.

- Acosta, R. V., and L. J. Carpenter. 2012. Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal, national study thirty five year update. Retrieved from www.acostacarpenter.org

- Adriaanse, J. 2016. “Gender Diversity in the Governance of Sport Associations: The Sydney Scoreboard Global Index of Participation.” Journal of Business Ethics 137 (1): 149–160. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2550-3.

- Au, S. Y., A. Tremblay, and L. You. 2020. “Times Up: Does Female Leadership Reduce Workplace Sexual Harassment?” Academy of Management Proceedings 2020 (1): 21007. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2020.21007abstract.

- AusPlay 2020. Volunteering in Sport. Retrieved from https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1029487/AusPlay-Volunteering-in-Sport.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. Women in Sport: The State of Play 2013. Retrieved from Canberra: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Products/4156.0.55.001∼June+2013∼Main+Features∼Women+in+Sport+The+State+of+Play+2013?OpenDocument

- Baxter, H., P. Kappelides, and R. Hoye. 2021. “Female Volunteer Community Sport Officials: A Scoping Review and Research Agenda.” European Sport Management Quarterly 1–18. doi:10.1080/16184742.2021.1877322.

- BBC 2022. 50:50: How It Works. British Broadcasting Corporation, London. https://www.bbc.co.uk/5050/methodology.

- Bekker, Sheree, Osman H. Ahmed, Ummukulthoum Bakare, Tracy A. Blake, Alison M. Brooks, Todd E. Davenport, Luciana De Michelis Mendonça, et al. 2018. “We Need to Talk about Manels: The Problem of Implicit Gender Bias in Sport and Exercise Medicine.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 52 (20): 1287–1289. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099084.

- Brown, D., and K. Christian. 2022. Players waiting in the wings to bolster female AFLW coaching ranks. ABC Sport. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-29/growing-pool-of-retired-athletes-to-bolster-aflw-coaching-ranks/101075340.

- Bruinvels, G., R. J. Burden, A. J. McGregor, K. E. Ackerman, M. Dooley, T. Richards, and C. Pedlar. 2017. “Sport, Exercise and the Menstrual Cycle: Where is the Research?” British Journal of Sports Medicine 51 (6): 487–488. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096279.

- Burke, M., M. Klugman, and K. O’Halloran. 2022. “Why Now’ for AFLW? Providing a New Affirmative Narrative for Women’s Football in the post-Covid World.” Sport in Society 1–18. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2041600.

- Cowley, E. S., A. A. Olenick, K. L. McNulty, and E. Z. Ross. 2021. “Invisible Sportswomen”: the Sex Data Gap in Sport and Exercise Science Research.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 29 (2): 146–151. doi:10.1123/wspaj.2021-0028.

- Diedrich, K. C. 2020. “Where Are the Moms? Strategies to Recruit Female Youth-Sport Coaches.” Strategies 33 (5): 12–17. doi:10.1080/08924562.2020.1781006.

- Donnelly, P. 2015. “Assessing the Sociology of Sport: On Public Sociology of Sport and Research That Makes a Difference.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 50 (4-5): 419–423. doi:10.1177/1012690214550510.

- Dwyer, D. B., K. Bellesini, P. Gastin, P. Kremer, and A. Dawson. 2019. “The Australian High Performance and Sport Science Workforce: A National Profile.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 22 (2): 227–231. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.07.017.

- Eime, R., M. Charity, B. C. Foley, J. Fowlie, and L. J. Reece. 2021. “Gender Inclusive Sporting Environments: The Proportion of Women in Non-Player Roles over Recent Years.” BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 13 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/s13102-021-00290-4.

- Felix, A. 2019, May 22. Allyson Felix: My Own Nike Pregnancy Story. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/opinion/allyson-felix-pregnancy-nike.html

- Fink, J. S. 2008. “Gender and Sex Diversity in Sport Organizations: Concluding Comments.” Sex Roles 58 (1–2): 146–147. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9364-4.

- Frick, B., and P. Wicker. 2016. “The Trickle-down Effect: how Elite Sporting Success Affects Amateur Participation in German Football.” Applied Economics Letters 23 (4): 259–263. doi:10.1080/13504851.2015.1068916.

- Guardian Sport 2022. AFL accepts it could have made public its report on female umpire abuse. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2022/may/03/afl-accepts-is-could-have-made-public-its-report-on-female-umpire-abuse

- Guthold, R., G. A. Stevens, L. M. Riley, and F. C. Bull. 2018. “Worldwide Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity from 2001 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 358 Population-Based Surveys with 1·9 Million Participants.” The Lancet Global Health 6 (10): e1077–e1086. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7.

- Hovden, J., and G. von der Lippe. 2019. “The Gendering of Media Sport in the Nordic Countries.” Sport in Society 22 (4): 625–638. doi:10.1080/17430437.2017.1389046.

- International Olympic Committee 2021. A positive trend at Tokyo 2020 for female coaches and officials. Retrieved from. https://olympics.com/ioc/news/a-positive-trend-at-tokyo-2020-for-female-coaches-and-officials

- International Olympic Committee 2022. Gender Equality & Inclusion Report 2021. https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/1568412/gender-equality-inclusion-report-2021-international-olympic-committee?_lg=en-GB

- Joecks, J., K. Pull, and K. Vetter. 2013. “Gender Diversity in the Boardroom and Firm Performance: What Exactly Constitutes a ‘‘Critical Mass’’?” Journal of Business Ethics 118 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1553-6.

- Jones, R. 2022. Study: 70% of Australians watch more women’s sport now than before pandemic. Sports Pro Media. Retrieved from https://www.sportspromedia.com/news/womens-sport-australia-foxtel-study-tv-viewership-wbbl-nrlw-aflw/

- Lampoon Group: Talent 2021. Ellyse Perry. Lampoon Group. Retrieved from https://www.lampoon.com.au/ellyse-perry/

- Lennon, S. 2013. “Journalism, Gender, Feminist Theory and News Reporting on the Australian Football League.” Ejournalist 13 (1): 20–39.

- Martínez-Rosales, E., A. Hernández-Martínez, S. Sola-Rodríguez, I. Esteban-Cornejo, and A. Soriano-Maldonado. 2021. “Representation of Women in Sport Sciences Research, Publications, and Editorial Leadership Positions: are we Moving Forward?” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 24 (11): 1093–1097. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2021.04.010.

- Memon, Aamir Raoof, Ishtiaq Ahmed, Nabiha Ghaffar, Kainat Ahmed, and Iqra Sadiq. 2022. “Where Are Female Editors from Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries? A Comprehensive Assessment of Gender, Geographical Distribution and Country’s Income Group of Editorial Boards of Top-Ranked Rehabilitation and Sports Science Journals.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 56 (8): 458–468. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-105042.

- Mergler, J. 2019. “An Exploration of the Developmental Sport and Training Histories of Canadian Sport Officials.” (Doctoral dissertation).

- NASO 2017. National Officiating Survey. National Association of Sports Officials. Retrieved from https://www.naso.org/survey/

- Palmer, K. 2019. The dial is shifting for gender equality in sport – just not fast enough. Retrieved from https://www.sportaus.gov.au/media_centre/news/the_dial_is_shifting_for_gender_equality_in_sport_just_not_fast_enough

- Piggott, L. V., and J. J. Matthews. 2021. “Gender, Leadership, and Governance in English National Governing Bodies of Sport: formal Structures, Rules, and Processes.” Journal of Sport Management 35 (4): 338–351. doi:10.1123/jsm.2020-0173.

- Pratt, J., P. Gordon, and D. Plamping. 2005. Working Whole Systems: putting Theory into Practice in Organisations. Radcliffe Publishing, Oxon.

- Price, J. 2015. “Where Are All the Women? Diversity, the Sports Media, and Sports Journalism Education.” The International Journal of Organizational Diversity 14 (1): 9–19. doi:10.18848/2328-6261/CGP/v14i01/58057.

- Rawlings, V., and D. Anderson. 2021. Girls and Women in Australian Football Umpiring: understanding Registration, Participation and Retention. AFL & University of Sydney, Sydney. https://d2n6ofw4o746cn.cloudfront.net/interactives/documents/AFL_umpiring.pdf.

- Richards, K., C. Litchfield, and J. Osborne. 2022. “We Need a Whole Range of Different Views’: exploring the Lived Experiences of Women Leaders in Australian Rules Football.” Sport in Society 25 (10): 1940–1956. doi:10.1080/17430437.2021.1905630.

- Spoor, J. R., and R. Hoye. 2014. “Perceived Support and Women’s Intentions to Stay at a Sport Organization.” British Journal of Management 25 (3): 407–424. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12018.

- Sport Australia 2017, May 22. Australian Sports Commission identifies need for more female coaches. Retrieved from. https://www.sportaus.gov.au/media-centre/news/australian_sports_commission_identifies_need_for_more_female_coaches

- Tingle, J. K., S. Warner, and M. L. Sartore-Baldwin. 2014. “The Experience of Former Women Officials and the Impact on the Sporting Community.” Sex Roles 71 (1–2): 7–20. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0366-8.

- Wicker, P., and S. Kerwin. 2022. “Women Representation in the Boardroom of Canadian Sport Governing Bodies: structural and Financial Characteristics of Three Organizational Clusters.” Managing Sport and Leisure 27 (5): 499–512. doi:10.1080/23750472.2020.1825987.

- Wicker, P., S. Feiler, and C. Breuer. 2022. “Board Gender Diversity, Critical Masses, and Organizational Problems of Non-Profit Sport Clubs.” European Sport Management Quarterly 22(2): 251–271.

- Women on Boards. 2016. Gender Balance in Global Sport Report. Retrieved from https://www.womenonboards.net/womenonboards-AU/media/AU-Reports/2016-Gender-Balance-In-Global-Sport-Report.pdf

- Women on Boards Australia. 2021. Lens on AFL Boards. Retrieved from https://www.womenonboards.net/womenonboards-AU/media/AU-PDFs/Lens-on-AFL-Boards-2021.pdf

- Women’s Sport Foundation 2019. Coaching through a Gender Lens: Maximizing Girls’ Play and Potential - Executive Summary. Retrieved from: https://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Gender-Lens-Executive-Summary-Updated-format-6-3-20-FINAL.pdf