Abstract

Whilst understanding the social norms of trash talking is an emerging field of research, the extent to how esport consumers perceive its practice in esports is currently limited. Guided by Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework to identify how social norms and moderating attributes influence behaviour, this study investigated consumers perceptions of trash talk in FPS esports. Focusing on Counter Strike: Global Offensive, Overwatch and Rainbow Six: Siege scenes, this study used data harvesting through the popular social media forum – Reddit and gathered 1,724 comments for analysis. Subjective and descriptive norms were influenced around the context of trash talk and the moments it occurred. Behavioural, individual, and contextual moderating attributes also influence consumers perspectives on why esport players do, or do not engage in trash talk. As an area of research still in its infancy, this paper aids in enhancing how communities reflect, discuss and debate relevant themes within esports.

Esports is a thriving digital environment where spectators congregate to watch their favourite professional player, or team, compete. It extends across various games and genres, such as the First-Person Shooter (FPS), which dates back to the 1990s with games like Doom (1993) and Quake (1996) and has established a highly competitive scene in Western culture in its own right (Bryce and Rutter Citation2002; Jonasson and Thiborg Citation2010; Therrien Citation2015; Wagner Citation2006). Current esports literature focusses largely on the consumptive needs of esport spectators (Qian et al. Citation2020; Pu, Xiao, and Kota Citation2022). Established fandoms and communities have developed emotional and consumptive ties to their chosen esport scene (Irwin and Naweed Citation2020; Johnson and Abarbanel Citation2022). Esport consumers have also used online forums in digital and social media to observe the attitudes and attributes of professional players (Spinda and Puckette Citation2018; Wong and Meng-Lewis Citation2022; Xue, Newman, and Du Citation2019).

Online forums serve as an information media where consumers can discuss and debate topics relevant to esports (Kow and Young Citation2013). However, social media has allowed fans to openly judge and criticise behaviour, particularly if spectators witness acts perceived to go against their social norms, reflecting the values and beliefs shared within the community (Hilvert-Bruce and Neill Citation2020; Türkay et al. Citation2020). In conventional sports, spectators engage in publicly shaming practices centred around an athlete’s violation of social norms, which can lead to withdrawal of support and adversely impact their careers (MacPherson and Kerr Citation2021; Sanderson Citation2013; Sanderson and Truax Citation2014). Whilst research has acknowledged that esport spectators ‘judge’ behaviour perceived to go against social norms, it is how, and to what extent, consumers communicate and distinguish social norms that is less understood (Cheung and Huang Citation2011; Naweed, Irwin, and Lastella Citation2020).

One practice governed primarily by its social norms is trash talk, where taunts and insults are directed towards others in a competitive scene, including opponents, fans, coaches and team members (Cook, Schaafsma, and Antheunis Citation2018; Cote Citation2017; Eveslage and Delaney Citation1998; Kershnar Citation2015). The normative boundaries of trash talk differ across conventional sporting communities (Conmy et al. Citation2013; Rainey and Granito Citation2010; Trammel et al. Citation2017) and has been debated as a fair act of mental fortitude (Howe Citation2004; Omine Citation2017) or rather a practice which goes against the values and ethics in competition (Dixon Citation2018). In casual video gaming, it has been described as part of the social ethos where it is used to formulate friendships (Cote Citation2017; Nakamura Citation2012; Wright, Boria, and Breidenbach Citation2002) or alternatively, to promote discomfort (Cook, Schaafsma, and Antheunis Citation2018; Kordyaka, Jahn, and Niehaves Citation2020). In a digital environment, esport players can manipulate the in-game mechanics to create unique trash talk practices (Irwin and Naweed Citation2020; Myers Citation2019). Verbal acts, however, have been considered an experience enjoyed and shared if they do not discriminate against socio-cultural themes of race, sex and gender (Cote Citation2017; Nakamura Citation2012; Ortiz Citation2019a; Tang, Reer, and Quandt Citation2020; Wright, Boria, and Breidenbach Citation2002).

In a recent study focused on the esports scene, Irwin, Naweed, and Lastella (Citation2021) observed that trash talk was perceived to be dialectical and mediated through three core elements: its motive, the context, and the people involved in a given act. Irwin, Naweed, and Lastella (Citation2021) concluded that further research of these elements would help increase our understanding of the ethics, acceptability, and underlying philosophy around its practice (188). As esports continue to grow in professionalism and popularity, understanding how its communities perceive and debate social norms is currently limited, and further research is required to aid in promoting positive satisfaction to consumers (Hilvert-Bruce and Neill Citation2020; Irwin, Naweed, and Lastella Citation2021; Cheung and Huang Citation2011).

Theoretical framework

To examine how esports communities perceive trash talk, this study draws on Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) theoretical framework. This framework synthesises various social theories to predict how social norms and moderating attributes influence behaviour, drawing on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen Citation1991), norm and attitude accessibility (Fazio Citation1986, Citation1990), dual-processing models of cognitive processing (Gibbons et al. Citation1998) and the Theory of Social Normative Behaviour (Rimal and Real Citation2005). Whilst other research has broadened and modified these theories, Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) argue that, individually, such frameworks can prevent delineating underlying conditions how behaviour is evaluated and processed.

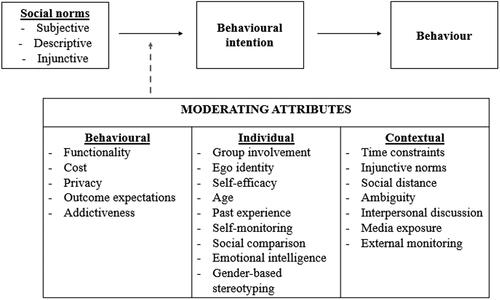

As shown in , Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework emphasises the relationship between core social norms and moderating attributes in given situations, and how they shape behaviour.

Figure 1. Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) revised theoretical framework how social norms and moderating attributes influence behaviour.

Descriptive norms refer to beliefs about what behaviours occur within a social group and Injunctive norms refer to behaviours driven to avoid social sanctions (Byron et al. Citation2016; Chung and Rimal Citation2016; Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren Citation1990; Kallgren, Reno, and Cialdini Citation2000). Put succinctly, the former refers to what people actually do whereas the latter refer to what they ought to do (Byron et al. Citation2016; Chung and Rimal Citation2016). In video gaming, players will avoid performing aggressive behaviour towards others as it goes against the normative beliefs shared within the community (i.e. descriptive norms) and avoids social repercussions, such as being reported and banned from the match (i.e. injunctive norms) (Hilvert-Bruce and Neill Citation2020; Türkay et al. Citation2020; Adinolf and Turkay Citation2018). On the other hand, Subjective norms refer to behaviours which are acted in accordance to perceived social pressure(s) of a given group (Ajzen Citation1991; Chung and Rimal Citation2016). A key premise here is how the influence of norms and attributes will alter depending on the time in a given situation, particularly as when:

An individual makes a spontaneous decision, she will likely enact a behaviour that is informed by the most salient attitude or norm that comes to mind in that moment… In contrast, when an individual has time to deliberate before acting, she will have the cognitive ability to consider both attitudes and norms when making her decision (Chung and Rimal Citation2016, 19).

Table 1. Moderating attributes as defined by Chung and Rimal (Citation2016).

While social norms become established in a given setting, moderating attributes can influence the impact one acts in accordance with them (Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren Citation1990; Lapinski and Rimal Citation2005; Rimal and Real Citation2005). For example, smoking among adolescents can be influenced by ‘group involvement’, where the behaviour can be encouraged within an individual’s peers and friendship group (Chung and Rimal Citation2016; Kobus Citation2003). In an esports context, it can be speculated that a player will engage in ‘trolling’ (verbal and in-game harassment) when they witness others performing similar behaviour (Cook et al. Citation2019; Cook, Schaafsma, and Antheunis Citation2018). In current trash talking literature, the impact of moderating attributes has thus far been explored through ‘self-efficacy’, (Conmy et al. Citation2013; Rainey and Granito Citation2010) and ‘outcome expectations’ (McDermott and Lachlan Citation2021). However, the extent to which consumers observe various moderating attributes and their influence on social norms and behaviour has not been identified. Through the lens of Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework, the aim of this study was to see how communities react, judge and analyse acts of trash talk witnessed in esports. The research question guiding this study asks what governs community perceptions of trash talk in esports?

Methodology

Study design

This study adopted qualitative orientation with a convergent approach (Creswell Citation2014) and focused on three FPS esport communities/games that were considered the most popular of the genre at the time of data collection (Ramsey Citation2020). These were: Counter Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) (Hidden Path Entertainment Citation2012), Overwatch (Blizzard Entertainment 2015) and Rainbow Six: Siege (Ubisoft Montreal Citation2015). Due to the limited research on trash talk in esports, and this study’s focus towards discovering how consumers perceive its practice, a qualitative approach was required (Maxwell et al. Citation2020; Sparrow et al. Citation2020). Specifically, the use of a convergent approach facilitated ease of access and showed how these games were contrived through diverse esport environments. For the purpose of this study, and aligned with previous literature, esport consumers are defined as all individuals who engage in esports – ranging from not only fans and spectators, but also includes professional players, commentators, tournament developers and other prominent industry workers (Abarbanel and Johnson Citation2019; Huettermann et al. Citation2020; Ji and Hanna Citation2020; Weiss and Schiele Citation2013).

Data harvesting occurred between October 2019 to February 2020 and was undertaken on Reddit, a public and online media forum. Use of public, online forums has been recognised as an effective method to encapsulate perspectives within video gaming and esports culture (Cheung and Huang Citation2011; Sparrow et al. Citation2020). Reddit was chosen due to its popularity among esport consumers (Seo Citation2013; Sparrow et al. Citation2020). The ‘subreddits’ (i.e. central hubs for consumer congregation) used were r/GlobalOffensive (1.2 m members), r/Overwatch (5.3 m members), r/OverwatchLeague (75.7k members), r/RainbowSixSiege (85.1k members) and r/R6ProLeague (98.8k members).

Procedure

To gather comments relevant to trash talk, an inclusion and exclusion method was applied to identify and remove off-topic discussions (Hawkins and Filtness Citation2017) using key search terms (Trash talk, banter, taunt/s, shit talk) (Irwin, Naweed, and Lastella Citation2021). Once relevant threads appeared, all of the quotes, opening thread statements, and responses significant to trash talk were extracted systematically. During this, it became clear that the communities had developed their own terminology/jargon that corresponded to trash talk (i.e. Pop offs and Roasting) (Irwin and Naweed Citation2020; Seo Citation2013). These new terms were added with the inclusion terms. provides an overview of inclusion and exclusion search terms.

Table 2. Overview of all search terms and exclusion themes with examples.

summarises the total number of quotes that were gathered. Across the three esports, a total of 106 threads were read, with number of comments across threads reaching 13,284 comments in total. After applying the exclusion themes, a total of 1,724 (12.97%) comments were analysed as part of a final dataset.

Table 3. A summary of the data obtained for this study.

Data analysis

To evaluate the data corresponding to Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework, this study applied both an inductive and deductive approach for data analysis. This was necessary as Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework does not specify social norms, but instead, concedes how they can be broad and altered in certain environments. To then uncover the types of social norms associated with trash talk, all data was first analysed inductively using descriptive coding (Saldana Citation2014) with NVivo (ver. 12). Coding consisted of highlighting sections of a text and developing shorthand labels (i.e. codes) to describe content and create a condensed overview of the main recurring points. Following this, a constant comparative method was adopted through Thematic Analysis (Gibson and Brown Citation2009), where key words identified patterns and created key themes to cover and formulate overarching classifications, and elements, associated with trash talk and social norms.

The second stage of analysis comprised of deductively coding the data through Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) moderating attributes. Using the definitions all 21 attributes, key phrases were corresponded accordingly to how esport consumers perceive these attributes in esports. shows an example how deductive coding was achieved. Using the definition of emotional intelligence in Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework, comments with key words (seen below in bold) which aligned with this attribute were detected. In NVivo, these comments were then added to the emotional intelligence ‘code’ to monitor the frequency this attribute was identified. Out of the original 21 attributes, 14 achieved saturation and were included in the final results. provides a summary of the moderating attributes analysed in this study.

Table 4. An example of how deductive coding was achieved illustrated by showing two comments gathered in the data collection which informed the definition for the moderating attribute of emotional intelligence. Colour fonts in data and definition columns used to show correspondence in coding.

Table 5. Frequency of coded moderating attributes observed in this study in accordance with Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework.

Results and discussion

Results revealed forms of social norms associated with trash talk in esports and the influence of moderating attributes. Supporting literature is referenced throughout to support these views and perspectives. Direct quotes from the data are also provided, in convention with the year they were published and the esport community they derive from. The first results will discuss the social norms of trash talk, then followed by the moderating attributes affiliated with their use.

Injunctive, descriptive and subjective norms of trash talk

Esport consumers debated the use of trash talk in relation to their social norms throughout discussions. For instance, the subjective norms around the use of trash talk varied around the match. If trash talk occurred before the match, it was perceived to promote hype and add excitement for the game (Su Citation2010). After a match, perspectives around acceptability altered depending on the level of respect shown towards the opposing team, after all the trash talking, having good sportsmanship and handshaking each other, even hugging after the game was over, [CS:GO, 2019] and:

I just hope that they can tell where the line is drawn. If you win, the post-match interview you are going to get after lifting the trophy is not exactly the best place, be respectful to opponents that you beat, you can trash talk them next time you face them and rubbing that match on their faces, but immediately after beating them is not a good moment. [CS:GO, 2017]

Banter and trash talk is fine, as long as it is done in good taste. Just calling the other team an expletive is boring and just damages your image. But finding a creative way to banter is funny and can add flavor to the league. [Overwatch, 2018]

The current status of the team/players also influenced perspectives of trash talk with feelings of acceptance varying based on prominence of skill level, Honestly, I dont see any problems with trash talkung [sic] if they can back it up [R6:S, 2019] to whether the team would trash talk a lesser opponent, Rule of thumb is never punch down. [Team 1] are favorites vs [Team 2] and [Team 3] so bming them a little bit is seen as an imbalance. Trash talking your equals or superiors can be exciting though [CS:GO, 2018]. The morality of trash talk was questioned where deemed excessive, [pro player] was overdoing it yesterday with shooting at dead bodies, no need to do that like every round [CS:GO, 2017]. Lastly, the context of trash talk also alters if it was used as a means to offend an opposing team or to defend oneself: This isn’t your average individual, it’s a competitive guy before a final who’s asked in front of a camera and crowd to respond to someone confidently saying his team will lose. Of course he will defend himself, [CS:GO, 2017].

Moderating attributes

Behavioural attributes

The data identified several behavioural attributes to reflect their attitudes towards trash talk. An overview of these attributes are as follows:

Outcome expectations and Functionality

Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) defined two forms of behavioural attributes – Outcome Expectations and Functionality. Outcome expectations refer to when social norms become inconsequential if the benefits of the outcome are of high value (Chung and Rimal Citation2016). For example, one spectator said that a player, were trying to get the mental advantage by rubbing salt in the wound. [RS:6, 2019]. Functionality is based on Katz’s (Citation1960) functions of attitudes and in line with these, illustrates how esport consumers view these functions with trash talk, and it was evident that the behavioural intentions behind trash talk varied depending on the motive towards its act.

Table 6. An overview of the functional analysis of attitudes (Katz Citation1960) and discussions of motives behind trash talk.

Cost

Normative influence changes depending on the perceptions of behaviours and monetary cost. For esport consumers, cost prominently referred to the type of tournament players competed in, where higher monetary costs (i.e. more prestigious tournaments/greater prize money on offer) would deter players from engaging in trash talk. As noted by one consumer, think about competing on a stage to secure an extra $35k and potential $430k on top of that. it’s not ‘far too serious’, it’s competition [CS:GO, 2017]. However, Chung and Rimal identified that not all costs are monetary and could also be classified through subjective perception. In esports, trash talk can be seen as a form of distraction: It’s purely personal. Some players will flame and blame others, some keep their cool all time….as the skill difference is so little in the pro scene you are better off practicing 24/7 than blaming and shit talking others. [Overwatch, 2017]

Privacy

Across the reddit forums, esport consumers acknowledged that their understanding of players relationships and frequency to trash talk is limited if an action occurs offline or not within tournaments. In a thread discussing the forms of trash talk occurring in competitive CS:GO matches, one spectator noted how the commentators observed the in-game chat, and argued how it could have prevented other players from engaging in trash talk:

The difference is American football players diss each other on the field when they aren’t mic’ed up. CS players have everything recorded. Unless they make a secret channel to chat that the general public doesn’t see, they’ll be under greater scrutiny [CS:GO, 2014].

Individual attributes

Self-monitoring, group involvement and ego identity

Beyond behavioural attributes, consumers observed the individual attributes of professional players and how they influenced behaviour (Chung and Rimal Citation2016). For instance, Self-monitoring refers to regulating one’s behaviours to ensure an appropriate and desirable public appearance. In one aspect, spectators believed that players trash talk to promote hype for the community; It’s just a bit of banter to up the stakes and nothing more. A sizeable portion of this community have been asking for more of this. [Overwatch, 2019] and, ‘[Professional RS:6 player] just tries to be a little toxic to build the scene, I think. [sic] Drama is just interesting and being respectful al [sic] the time gets boring and [Professional RS:6 player] understands that and tries to bring eyeballs to the screen’. [RS:6, 2020].

Likewise, higher group involvement is likely to increase the influence of social norms on behaviour for the goal to fit in with a group identity central to one’s self-concept (Chung and Rimal Citation2016, 16). Trash talk could negatively affect group involvement, and spectators noted the caution they perceived players to implement towards its use: It’s always trash talk until some people don’t like what’s been said. The drama on reddit and social media is why players don’t trashtalk in the first place. [CS:GO, 2017]. This was observed in another discussion:

As a professional, if you have beef, you take that up with the person in a DM or something similar, or real life. You don’t blow shit up publically [sic] because it makes you look like an asshole and you burn a LOT of bridges. As an org, do you want to hire a player that’s liable to vehemently shittalk you as soon as his contract runs out? [CS:GO, 2019]

[Trash Talk] is an issue when they are representing an org and sponsors. It’s a double edged blade. Money talks, and if you’re not f0rest, GTR, s1mple, C9 etc. (who have a huge, built in fan base without needing to try and grab attention) then shit-talking can make you stand out and bring in that attention. But if your players are kids who don’t know where to draw the line and have the potential to cause a huge PR shit-storm, that attention becomes a negative. [CS:GO, 2018]

Honestly if [professional RS:6 player] ever broke his whole demeanor [sic] would be ruined. It’s the fact that he literally never quits it and acts like a normal person. Like you know he’s not a bad dude or anything, and clearly behind the scenes he’s just another guy, but when the cameras on or there’s an audience dude is just on 100% deadpan shit talking with no limits. It’s amazing [RS:6, 2018].

Emotional intelligence

Trash talk literature has debated its function as a form of psychological advantage (Eveslage and Delaney Citation1998; Howe Citation2004; Johnson and Taylor Citation2020; Nakamura Citation2012). Emotional Intelligence in Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework is defined as the mental ability to handle emotional information influenced by peers. It could be understood that a core individual attribute for trash talk is to prevent it overcoming and distracting the players’ performance or to use it as an advantage. Regarding testing mental commitment, one user stated, Taunting should be a legitimate strategy that targets the opponent’s mental weakness. That said, I fully expect pros to have the mental fortitude to ignore the taunting. [Overwatch, 2017]

Age

A common agreement among esport consumers is how the competitive scene attracts, not only a young audience, but also young professional talent. As such, consumers reflected on the age of players and how, these players although are adults, are still kids that average 19yo that aren’t experienced alot of emotional maturity that older traditional sport players have, [Overwatch, 2019].

Self efficacy

Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) noted Self efficacy as someone’s confidence to exert personal control. Yet, consumers observed that the pressure and impulse could overwhelm a professional player, resulting in a need to, let off steam and trash talk towards an opponent and reduce their self efficacy. One consumer perceived:

It’s an incredibly high-pressure situation, these guys are pumping with adrenaline and this is how they let it off. When they are taunting the other team, they aren’t actually trying to insult them, it’s just how they vent their emotions [CS:GO, 2017]

To be fair they all get caught up in the moment - most of the [Team 1] guys get on with and play with the [Team 2] guys weekly on stream/scrims etc, it’s not like they hate each other, they just have good banter in the heat of the moment [RS:6, 2017].

I don’t even get how you can take it out of context, this is sooo clearly just motivational talk to hype your team up. But we also had Twitch Chat go crazy laughing and hating the Shock against the [Team 1] when [Player 1] said something like “We are so much better then [sic] them!”. I don’t get why some people just try their hardest to take it the worst way possible. [Overwatch, 2019]

Contextual attributes

External monitoring

As a professional environment, esports are governed through external monitoring, where tournament organisers and game developers can enforce rules and sanctions. Comparing esports to conventional sports, a consumer stated, I linked the nfl rules… taunting not allowed. I mean every league has rules like that but that doesnt [sic] stop the players from trying to gain every advantage they can over their opponent. [Overwatch, 2017]. In regard to the esports scene itself, a consumer noted that a professional players behaviour outside of the competitive scene is also observed by the community and officials:

I think being a pro player for a certain game requires you to behave well in that particular game, and everything which happens ingame and outside of it in its community is relevant to the pro player career. So in this case being toxic towards other players in R6 definitely warranted the attention it got. [RS:6, 2017]

Ambiguity

As a multicultural environment, esport consumers emphasised that cultural differences between players can impact their intentions to engage in trash talk. Esports is an international scene, and each of the chosen FPS communities compete across various regions and international tournaments. Culture clashes, and second English professional players could impact their willingness to participate in trash talk:

We’re also dealing with people who don’t speak English as a primary language so if their trash talk is good for their culture, it may sound ridiculous when they translate it to English… Maybe it’s a Cultural Thing, I’d say for Most people in Germany this behaviour appears to be waaay too aggressive. Never liked people who lost their Minds about a competition. Luckily for me, my those [sic] people hardly win anything because they can’t stay cool [CS:GO, 2017].

Interpersonal discussion and media exposure

Esport consumers can be aware of the interpersonal discussions established around trash talk. Yet, as with conventional sports, esports consumers can engage in harsh online practices towards professional players. Formations of online ‘witch hunts’ and the promotion of drama has previously been associated with acts that go against the social norms of esports (Carter and Gibbs Citation2013; Irwin and Naweed Citation2020). In this study, it is believed that their discussions were observed among professional players, which could prevent them from engaging in trash talk:

Definitely, love the “shittalking” (come on now, hardly shittalking, more like banter) from [Player 1], even though it backfires. But the way fans react because they have never done anything competitive in their life is probably why most people refrain from shittalking. [CS:GO, 2017]

It doesn’t matter if he thinks it’s not disrespectful. The perception by the others does. The way our society works is that the individual conforms to the society. If they do not conform, they get ostracized in one way or another. [Professional CS:GO player] may not mean anything bad by it, but his lack of self-awareness enables it to happen in the first place. It’s his flaw, not everyone else’s. [CS:GO, 2018]

Another user responded to this by stating that professional players should be able to express personal emotions in a tournament setting:

I am torn. On the one hand, I agree with you wholeheartedly. On the other, I think that within the realm of competition and sporting there is room for people to express themselves with raw emotion. The key is finding the balance – perhaps he needs to tone it down a bit. [CS:GO, 2018]

General discussion

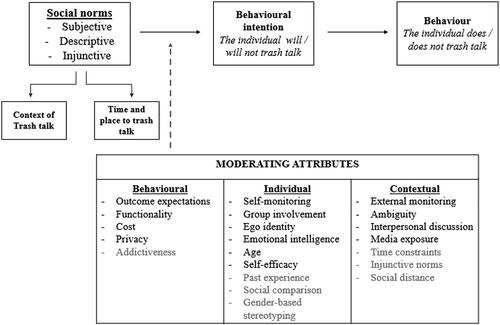

This study aimed to investigate how communities react, judge and analyse acts of trash talk witnessed in esports. Through a conceptual framework by Chung and Rimal (Citation2016), this study uncovered, not only how social norms on trash talk are observed, but also how esport communities judge and analyse in respect to underlying attributes which influence players behaviour. Based on these results, esports consumers generally believe that pro players, before trash talking, will evaluate the social norms and reflect on their moderating attributes to determine whether to engage in its practice. With this framework, the study findings proceed to evaluate how esport consumers analyse the relationship between core social norms (i.e. descriptive, subjective, and injunctive) and moderating attributes (i.e. behavioural, individual and contextual) in a single incident of trash talk. For example, a player who trash talks towards their opponent before a match opens up a discussion to assess its acceptability through analysing the social norms (i.e. its context/when it occurred) and the underlying salient attributes (i.e. the motive behind its use, the persona/individual factors of the players, cultural influences). summarises the results where social norms and moderating attributes influence potential reasons professional players will or will not engage in trash talk. Attributes formulated by Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) conceptualised to how esport spectators observe and speculate the use of trash talk in FPS esports.

Figure 2. The attributes moderating trash talk in esports as viewed through Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework. Attributes not discussed in this study are in grey.

This study proposes practical and theoretical contributions for investigating esport consumer behaviour. First, this study offers tangible insight how consumptive needs are fulfilled within esport communities. Research on esport consumer behaviour validates how fans require social needs to be satisfied (Rietz and Hallmann Citation2023; Jenny et al. Citation2018; Qian et al. Citation2022; Tang, Cooper, and Kucek Citation2021; Xiao Citation2020). While research has investigated the social atmospherics components at live esport events (Jang, Kim, and Byon Citation2020), this study exhibits how consumers utilise online forum discussions for engagement practices within their own communities. Esport organisations and tournament developers would benefit by exploring similar methods to encapsulate spectator needs to further understand how consumers perceive professional players behaviour (Naweed, Irwin, and Lastella Citation2020; Macey et al. Citation2022).

Through the lens of Chung and Rimal’s framework, this study has further opened a plethora of themes how spectators engage within the esport environment. Whilst this research focused on trash talk, it would be no surprise that these communities apply parallel evaluations to other, more imperative issues in esports. For instance, Johnson and Abarbanel (Citation2022) recently observed how esport spectators perceive and discuss cheating in esports, noting the affiliation between written rules of its practice, the ethics behind its use and how fans personal experiences influence their perceptions of the act. Johnson and Abarbanel (Citation2022) further concluded that investigating perspectives of cheating can become complex and alter upon various circumstances. This study proposes that frameworks such as Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) are beneficial in discovering underlying aspects which influence perceptions of behaviour within the esports ecosystem. As new esport scenes are constantly developing, seeing how newcomer communities formulate social norms and discuss moderating attributes and behaviour within these games merit examination.

Limitations and Future research directions

Online forum methodologies allow researchers to gain rich and diverse themes in a given area of research, but they are not without limitation. First, esport consumers did not deliberate other moderating attributes identified in Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework. For instance, Tendency to engage in social comparison is an individual attribute which reflects how, ‘people who socially comparing themselves with their peers are more strongly influenced by descriptive norms’ (Chung and Rimal Citation2016, 17). A reason for this is because this study aimed to investigate these attributes from a consumer perspective, and not from other prominent figures within the professional scene, including professional players, coaches, and tournament developers. Future research should aim at uncovering missing attributes from these other valuable industry perspectives to gain further insight towards the behaviours and perceptions towards trash talk.

Secondly, previous research on trash talk provides implicit themes that, whilst unseen in this study, would be applicable in this framework. For example, in reflection of the functionality behind trash talk, Kershnar (Citation2015) observes that trash talk can also occur towards a disliked opponent; harming them as a person with no motive reflecting the goal of the game. This is plausible as this study did not include professional player insights on their own specific motives and perspectives of trash talk, complete with their own underlying attributes.

A third limitation of this study is that Chung and Rimal (Citation2016) framework do not include further socio-cultural factors previously addressed in trash talk literature. Themes on race, sex and gender have been used to target minoritized groups in both casual video gaming (Cook et al. Citation2019; Cote Citation2017; Nakamura Citation2012; Ortiz Citation2019b) and conventional sports (Kilvington and Price Citation2019; Lawless and Magrath Citation2021; Long and McNamee Citation2004; Simons Citation2003). As representation of marginalized groups is becoming a focus in esports (Darvin, Vooris, and Mahoney Citation2020; Witkowski Citation2018), future research should explore how trash talk and socio-cultural components interrelate with each other within the professional environment.

Lastly, though this method allowed us to gain a grasp how esport communities react to trash talk, it is unknown whether these views reflect the majority of spectators and fans in these esports scenes (Sparrow et al. Citation2020). This may be problematic with the given respondent bias evident in online forums, where the consensus of discussion is often weighted towards agreement (Alsinet et al. Citation2018). Other qualitative and quantitative approaches could be beneficial in addressing this gap.

Conclusion

Strong fandoms and communities have been established in esports, where supporters develop emotional and consumptive ties to their chosen esport scene. The findings of this study identified how esport consumers use online forums to observe, analyse and debate how professional players engage in trash talk. Whilst esport consumers identify the descriptive, injunctive, and subjective social norms of the practice of trash talk; they also recognise how moderating behavioural, individual, and contextual attributes influence players behaviour. In turn, esport communities combine these factors to discuss the implications and its acceptability. It is hoped that future research will extend and broaden these findings to uncover further underlying attributes which influence trash talk.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest are reported by the authors.

References

- Abarbanel, Brett, and Mark R. Johnson. 2019. “Esports Consumer Perspectives on Match-Fixing: Implications for Gambling Awareness and Game Integrity.” International Gambling Studies 19 (2): 296–311. doi:10.1080/14459795.2018.1558451.

- Adinolf, Sonam, and Selen Turkay. 2018. “Toxic Behaviors in Esports Games: Player Perceptions and Coping Strategies.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion, 365–372. Melbourne, Australia: ACM.

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Alsinet, T., J. Argelich, R. Béjar, and Santi Martínez. 2018. “An Argumentation Approach for Agreement Analysis in Reddit Debates.” In Artificial Intelligence Re-Search and Development, edited by Z. Falomir, K. Gibert and E. Plaza, 217–226. CCIA.

- Blizzard Entertainment. 2015. Overwatch. Irvine, CA: Blizzard Entertainment.

- Bryce, J., and J. Rutter. 2002. “Spectacle of the Deathmatch: Character and Narrative in First-Person Shooters.” In ScreenPlay: Cinema/Videogames/Interfaces, edited by G. King and T. Krzywinska, 66–80. London, UK: Wallflower Press.

- Byron, M. J., J. E. Cohen, S. Frattaroli, J. Gittelsohn, and D. H. Jernigan. 2016. “Using the Theory of Normative Social Behavior to Understand Compliance with a Smoke-Free Law in a Middle-Income Country.” Health Education Research 31 (6): 738–748. doi:10.1093/her/cyw043.

- Carter, Marcus, and Martin R. Gibbs. 2013. “eSports in EVE Online: Skullduggery, Fair Play and Acceptability in an Unbounded Competition.” Paper presented At the Foundation of Digital Games, Crete, Greece.

- Cheung, Gifford, and Jeff Huang. 2011. “Starcraft from the Stands: Understanding the Game Spectator.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 763–772. Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM.

- Chung, Adrienne, and Rajiv N. Rimal. 2016. “Social Norms: A Review.” Review of Communication Research 4: 1–28. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2016.04.01.008.

- Cialdini, Robert B., Raymond R. Reno, and Carl A. Kallgren. 1990. “A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58 (6): 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015.

- Conmy, Ben, Gershon Tenenbaum, Robert Eklund, Alysia Roehrig, and Edson Filho. 2013. “Trash Talk in a Competitive Setting: Impact on Self-Efficacy and Affect.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (5): 1002–1014. doi:10.1111/jasp.12064.

- Cook, Christine, Juliette Schaafsma, and Marjolijn Antheunis. 2018. “Under the Bridge: An in-Depth Examination of Online Trolling in the Gaming Context.” New Media & Society 20 (9): 3323–3340. doi:10.1177/1461444817748578.

- Cook, Christine, Rianne Conijn, Juliette Schaafsma, and Marjolijn Antheunis. 2019. “For Whom the Gamer Trolls: A Study of Trolling Interactions in the Online Gaming Context.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 24 (6): 293–318. doi:10.1093/jcmc/zmz014.

- Cote, Amanda C. 2017. ““I Can Defend Myself.” Women’s Strategies for Coping with Harassment While Gaming Online.” Games and Culture 12 (2): 136–155. doi:10.1177/1555412015587603.

- Creswell, J. W. 2014. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Darvin, Lindsey, Ryan Vooris, and Tara Mahoney. 2020. “The Playing Experiences of Esport Participants: An Analysis of Treatment Discrimination and Hostility in Esport Environments.” Journal of Athlete Development and Experience 2 (1): 36–50. doi:10.25035/jade.02.01.03.

- Dixon, N. 2018. “The Intrinsic Wrongness of Trash Talking and How It Diminishes the Practice of Sport: Reply to Kershnar.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 12 (2): 211–225. doi:10.1080/17511321.2017.1421699.

- Duncan, Samuel. 2019. “Sledging in Sport—Playful Banter, or Mean-Spirited Insults? A Study of Sledging’s Place in Play.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 13 (2): 183–197. doi:10.1080/17511321.2018.1432677.

- Eveslage, Scott, and Kevin Delaney. 1998. “Talkin’ Trash at Hardwick High: A Case Study of Insult Talk on a Boys’ Basketball Team.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 33 (3): 239–253. doi:10.1177/101269098033003002.

- Fazio, Russell H. 1986. “How Do Attitudes Guide Behavior?” In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior, edited by R. M. Sorrentino and E. T. Higgins, 204–243. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fazio, Russell H. 1990. “Multiple Processes by Which Attitudes Guide Behavior: The Mode Model as an Integrative Framework.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 23: 75–109. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60318-4.

- Gibbons, Frederick X., Meg Gerrard, Hart Blanton, and Daniel W. Russell. 1998. “Reasoned Action and Social Reaction: Willingness and Intention as Independent Predictors of Health Risk.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (5): 1164–1180. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1164.

- Gibson, W. J., and A. Brown. 2009. Working with Qualitative Data. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Hawkins, A. N., and A. J. Filtness. 2017. “Driver Sleepiness on YouTube: A Content Analysis.” Accident; Analysis and Prevention 99 (Pt B): 459–464. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2015.11.025.

- Hidden Path Entertainment. 2012. Counter Strike: Global Offensive. [Video Game]. Bellevue, WA: Valve Cooperation.

- Hilvert-Bruce, Zorah, and James T. Neill. 2020. “I’m Just Trolling: The Role of Normative Beliefs in Aggressive Behaviour in Online Gaming.” Computers in Human Behavior 102: 303–311. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.003.

- Howe, Leslie A. 2004. “Gamesmanship.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 31 (2): 212–225. doi:10.1080/00948705.2004.9714661.

- Huettermann, Marcel, Galen T. Trail, Anthony D. Pizzo, and Valerio Stallone. 2020. “Esports Sponsorship: An Empirical Examination of Esports Consumers’ Perceptions of Non-Endemic Sponsors.” Journal of Global Sport Management : 1–26. doi:10.1080/24704067.2020.1846906.

- Irwin, Sidney V., and Anjum Naweed. 2020. “BM’ing, Throwing, Bug Exploiting, and Other Forms of (Un)Sportsmanlike Behavior in CS:GO Esports.” Games and Culture 15 (4): 411–433. doi:10.1177/1555412018804952.

- Irwin, Sidney V., Anjum Naweed, and Michele Lastella. 2021. “The Mind Games Have Already Started: An in-Depth Examination of Trash Talking in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive Esports Using Practice Theory.” Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds 13 (2): 173–194. doi:10.1386/jgvw_00035_1.

- Jang, Wooyoung W., Kyungyeol A. Kim, and Kevin K. Byon. 2020. “Social Atmospherics, Affective Response, and Behavioral Intention Associated with Esports Events.” Frontiers in Psychology 11:1-11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01671.

- Jenny, Seth E., Margaret C. Keiper, Blake J. Taylor, Dylan P. Williams, Joey Gawrysiak, R. Douglas Manning, and Patrick M. Tutka. 2018. “eSports Venues: A New Sport Business Opportunity.” Journal of Applied Sport Management 10 (1): 34–49. doi:10.18666/JASM-2018-V10-I1-8469.

- Ji, Zeran, and Richard C. Hanna. 2020. “Gamers First – How Consumer Preferences Impact eSports Media Offerings.” International Journal on Media Management 22 (1): 13–29. doi:10.1080/14241277.2020.1731514.

- Johnson, Christopher, and Jason Taylor. 2020. “More than Bullshit: Trash Talk and Other Psychological Tests of Sporting Excellence.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 14 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1080/17511321.2018.1535521.

- Johnson, Mark R., and Brett Abarbanel. 2022. “Ethical Judgments of Esports Spectators regarding Cheating in Competition.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 28 (6): 1699–1718. doi:10.1177/13548565221089214.

- Jonasson, Kalle, and Jesper Thiborg. 2010. “Electronic Sport and Its Impact on Future Sport.” Sport in Society 13 (2): 287–299. doi:10.1080/17430430903522996.

- Kallgren, Carl A., Raymond R. Reno, and Robert B. Cialdini. 2000. “A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: When Norms Do and Do Not Affect Behavior.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26 (8): 1002–1012. doi:10.1177/01461672002610009.

- Katz, D. 1960. “The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes.” Public Opinion Quarterly 24 (2): 163–204. doi:10.1086/266945.

- Kershnar, Stephen. 2015. “The Moral Rules of Trash Talking: Morality and Ownership.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 9 (3): 303–323. doi:10.1080/17511321.2015.1099117.

- Kilvington, Daniel, and John Price. 2019. “Tackling Social Media Abuse? Critically Assessing English Football’s Response to Online Racism.” Communication & Sport 7 (1): 64–79. doi:10.1177/2167479517745300.

- Kobus, Kimberly. 2003. “Peers and Adolescent Smoking.” Addiction 98 (1): 37–55. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x.

- Kordyaka, Bastian, Katharina Jahn, and Bjoern Niehaves. 2020. “Towards a Unified Theory of Toxic Behavior in Video Games.” Internet Research 30 (4): 1081–1102. doi:10.1108/INTR-08-2019-0343.

- Kow, Yong Ming, and Timothy Young. 2013. “Media Technologies and Learning in the Starcraft Esport Community.” In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 387–398. San Antonio, TX: ACM. doi:10.1145/2441776.2441821.

- Lapinski, Maria Knight, and Rajiv N. Rimal. 2005. “An Explication of Social Norms.” Communication Theory 15 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x.

- Lawless, William, and Rory Magrath. 2021. “Inclusionary and Exclusionary Banter: English Club Cricket, Inclusive Attitudes and Male Camaraderie.” Sport in Society 24 (8): 1493–1509. doi:10.1080/17430437.2020.1819985.

- Long, Jonathan A., and Mike J. McNamee. 2004. “On the Moral Economy of Racism and Racist Rationalizations in Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 39 (4): 405–420. doi:10.1177/1012690204049068.

- Macey, Joseph, Ville Tyrväinen, Henri Pirkkalainen, and Juho Hamari. 2022. “Does Esports Spectating Influence Game Consumption?” Behaviour & Information Technology 41 (1): 181–197. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2020.1797876.

- MacPherson, Ellen, and Gretchen Kerr. 2021. “Sport Fans’ Responses on Social Media to Professional Athletes’ Norm Violations.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19 (1): 102–119. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2019.1623283.

- Maxwell, December, Sarah R. Robinson, Jessica R. Williams, and Craig Keaton. 2020. “A Short Story of a Lonely Guy”: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Involuntary Celibacy Using Reddit.” Sexuality & Culture 24 (6): 1852–1874. doi:10.1007/s12119-020-09724-6.

- McDermott, Karen C. P., and Kenneth A. Lachlan. 2021. “Emotional Manipulation and Task Distraction as Strategy: The Effects of Insulting Trash Talk on Motivation and Performance in a Competitive Setting.” Communication Studies 72 (5): 915–936. doi:10.1080/10510974.2021.1975139.

- Myers, Brian. 2019. “Friends with Benefits: Plausible Optimism and the Practice of Teabagging in Video Games.” Games and Culture 14 (7–8): 763–780. doi:10.1177/1555412017732855.

- Nakamura, Lisa. 2012. “It’s a Nigger in Here! Kill the Nigger! User‐Generated Media Campaigns against Racism, Sexism, and Homophobia in Digital Games.” In The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies, edited by A. Valdivia, 2–15. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9781444361506.wbiems159.

- Naweed, Anjum, Sidney V. Irwin, and Michele Lastella. 2020. “Varieties of (Un)Sportsmanlike Conduct in the FPS Esports Genre: A Taxonomic Classification of ‘Esportsmanship.” Journal of Global Sport Management : 1–21. doi:10.1080/24704067.2020.1846907.

- Omine, Mitsuharu. 2017. “Ethics of Trash Talking in Soccer*.” International Journal of Sport and Health Science 15 (0): 120–125. doi:10.5432/ijshs.201718.

- Ortiz, Stephanie M. 2019a. “The Meanings of Racist and Sexist Trash Talk for Men of Color: A Cultural Sociological Approach to Studying Gaming Culture.” New Media & Society 21 (4): 879–894. doi:10.1177/1461444818814252.

- Ortiz, Stephanie M. 2019b. “You Can Say I Got Desensitized to It”: How Men of Color Cope with Everyday Racism in Online Gaming.” Sociological Perspectives 62 (4): 572–588. doi:10.1177/0731121419837588.

- Pu, Haozhou, Shuhong Xiao, and Ryan W. Kota. 2022. “Virtual Games Meet Physical Playground: Exploring and Measuring Motivations for Live Esports Event Attendance.” Sport in Society 25 (10): 1886–1908. doi:10.1080/17430437.2021.1890037.

- Qian, Tyreal Yizhou, James Jianhui Zhang, Jerred Junqi Wang, and John Hulland. 2020. “Beyond the Game: Dimensions of Esports Online Spectator Demand.” Communication & Sport 8 (6): 825–851. doi:10.1177/2167479519839436.

- Qian, Tyreal Yizhou, Jerred Junqi Wang, James Jianhui Zhang, and John Hulland. 2022. “Fulfilling the Basic Psychological Needs of Esports Fans: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.” Communication & Sport 10 (2): 216–240. doi:10.1177/2167479520943875.

- Rainey, David W., and Vincent Granito. 2010. “Normative Rules for Trash Talk among College Athletes: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Sport Behavior 33 (3): 276–294.

- Ramsey, J. 2020. “Top 10 eSports Games of 2020: Biggest Prizes & Viewership.” Lineups. https://www.lineups.com/esports/top-10-esports-games/.

- Rietz, Julia, and Kirstin Hallmann. 2023. “A Systematic Review on Spectator Behavior in Esports: Why Do People Watch?” International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship 24 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1108/IJSMS-12-2021-0241.

- Rimal, Rajiv N., and Kevin Real. 2005. “How Behaviors Are Influenced by Perceived Norms:A Test of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior.” Communication Research 32 (3): 389–414. doi:10.1177/0093650205275385.

- Saldana, Johnny. 2014. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sanderson, Jimmy, and Carrie Truax. 2014. ““I Hate You Man!”: Exploring Maladaptive Parasocial Interaction Expressions to College Athletes via Twitter.” Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics 7: 333–351.

- Sanderson, Jimmy. 2013. “From Loving the Hero to Despising the Villain: Sports Fans, Facebook, and Social Identity Threats.” Mass Communication and Society 16 (4): 487–509. doi:10.1080/15205436.2012.730650.

- Seo, Yuri. 2013. “Electronic Sports: A New Marketing Landscape of the Experience Economy.” Journal of Marketing Management 29 (13–14): 1542–1560. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.822906.

- Simons, Herbert D. 2003. “Race and Penalized Sports Behaviors.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 38 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1177/10126902030381001.

- Sparrow, L., M. Antonellos, M. Gibbs, and M. Arnold. 2020. “From ‘Silly’ to ‘Scumbag’: Reddit Discussion of a Case of Groping in a Virtual Reality Game.” In Proceedings of the 2020 DiGRA International Conference: Play Everywhere. The Digital Games Research Association.

- Spinda, John S. W., and Stephen Puckette. 2018. “Just a Snap: Fan Uses and Gratifications for following Sports Snapchat.” Communication & Sport 6 (5): 627–649. doi:10.1177/2167479517731335.

- Su, Norman Makoto. 2010. “Street Fighter IV: Braggadocio off and on-Line.” In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 361–370. Savannah, GA: ACM.

- Tang, Tang, Roger Cooper, and Jake Kucek. 2021. “Gendered Esports: Predicting Why Men and Women Play and Watch Esports Games.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 65 (3): 336–356. doi:10.1080/08838151.2021.1958815.

- Tang, Wai Yen, Felix Reer, and Thorsten Quandt. 2020. “Investigating Sexual Harassment in Online Video Games: How Personality and Context Factors Are Related to Toxic Sexual Behaviors against Fellow Players.” Aggressive Behavior 46 (1): 127–135. doi:10.1002/ab.21873.

- Therrien, Carl. 2015. “Inspecting Video Game Historiography through Critical Lens: Etymology of the First-Person Shooter Genre.” Game Studies 15 (2).

- Trammel, Richard, Judy L. Van Raalte, Britton W. Brewer, and Albert J. Petitpas. 2017. “Coping with Verbal Gamesmanship in Golf: The PACE Model.” Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 8 (3): 163–172. doi:10.1080/21520704.2016.1263980.

- Türkay, Selen, Jessica Formosa, Sonam Adinolf, Robert Cuthbert, and Roger Altizer. 2020. “See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil: How Collegiate Players Define, Experience and Cope with Toxicity.” In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. Honolulu, HI: Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3313831.3376191.

- Ubisoft Montreal. 2015. “Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six Siege.” In [Video Game]. Montreal, Canada: Ubisoft.

- Wagner, Michael G. 2006. “On the Scientific Relevance of eSports.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Internet Computing, Las Vegas, NV.

- Weiss, Thomas, and Sabrina Schiele. 2013. “Virtual Worlds in Competitive Contexts: Analyzing eSports Consumer Needs.” Electronic Markets 23 (4): 307–316. doi:10.1007/s12525-013-0127-5.

- Witkowski, Emma. 2018. “Doing/Undoing Gender with the Girl Gamer in High-Performance Play.” In Feminism in Play, edited by Kishonna L. Gray, Gerald Voorhees, and Emma Vossen, 185–203. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Wong, Donna, and Yue Meng-Lewis. 2022. “Esports: An Exploration of the Advancing Esports Landscape, Actors and Interorganisational Relationships.” Sport in Society: 1–27. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2086458.

- Wright, Talmadge, Eric Boria, and Paul Breidenbach. 2002. “Creative Player Actions in FPS Online Video Games: Playing Counter-Strike.” Game Studies 2 (2): 103–123.

- Xiao, Min. 2020. “Factors Influencing eSports Viewership: An Approach Based on the Theory of Reasoned Action.” Communication & Sport 8 (1): 92–122. doi:10.1177/2167479518819482.

- Xue, Hanhan, Joshua I. Newman, and James Du. 2019. “Narratives, Identity and Community in Esports.” Leisure Studies 38 (6): 845–861. doi:10.1080/02614367.2019.1640778.