Abstract

This article analyses conditions for including parasports in the Swedish Floorball Federation (SFF) as a case in an ongoing large-scale organizational change aimed towards equal opportunities for persons with disabilities (PwD) within the Swedish Sports Confederation. Frame factor theory is used to analyse the SFF’s conditions for this inclusion in a pre-stage of change. Thus, this article aims to facilitate opportunities for equal conditions for sports participation. Twenty-two semi-structured interviews and 55 questionnaire responses from federation and district representatives informed the analysis. Findings revealed enabling conditions, such as a general benignity towards inclusion, but also highlighted limiting conditions such as mainstream representatives lack of knowledge about the process, which can lead to further marginalization of PwD. The conclusion was drawn that defining the meaning of inclusion in a pre-stage, regarding both policy and practice, is a pressing matter for the SFF to succeed in its continued process of including parasports.

Introduction

There is a discrepancy between sports’ governing policies and the way in which matters of diversity, such as inclusion, are understood and ‘done’ in practice (Spaaij et al. Citation2014). In 2006, the United Nations (UN) adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), stating that ‘countries are to guarantee that persons with disabilities enjoy their inherent right to life on an equal basis with others’ (UN (United Nations) Citation2006, 10) and further declaring that countries are to promote the ‘participation in mainstream and disability-specific sports’ (22) of persons with disabilities (PwD). However, PwD do not have equal opportunities or participation rates in everyday leisure and sports activities compared to their mainstream peers (DePauw and Gavron Citation2005; Elmose-Østerlund et al. Citation2019; Kiuppis Citation2018; Klenk, Albrecht, and Nagel Citation2019). Identified barriers for PwDs’ participation in sports include, for example, limitations in logistics and accessibility and a lack of awareness and understanding (DePauw and Gavron Citation2005), as well as discriminatory management practices due to ignorance and lack of experience (Darcy and Taylor Citation2009). According to Jeanes et al. (Citation2018), traditional sports structures and policies can also constrain initiatives towards including PwD within sports.

Historically, leisure and sporting activities for PwD have mainly been administered and conducted in their own separate organizations, but with the adoption of the CRPD, including PwD has become an increasingly important issue for sports governing bodies (Klenk, Albrecht, and Nagel Citation2019). As a new means to reach this inclusion, the Swedish Sports Confederation (SSC) is in the midst of an extensive organizational change. Parasport Sweden is one of the SSC’s 71 national sports organizations (NSO) and it acts as the collective sports organization for PwD, also referred to in this context as para-athletes. During the 2017 National Sports Meeting, it was decided that the sports that Parasport Sweden administered would be transferred to the mainstream NSOs, which were then to assume responsibility of parasports (Nordlund et al. Citation2022). In accordance with the SSC’s program manifesto What Sports Want [Idrotten Vill], Strategy 2025 [Strategi 2025], and the UN’s CRPD, this new way of organizing aims to provide PwD with equal opportunities for participation in sports (SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation) Citation2019a, Citation2019b; UN (United Nations) Citation2006). This top-down-initiated organizational change, often referred to as the inclusion process (Parasport Sweden Citation2021), brings a change in mission and organization for the receiving NSOs. This article takes a scientific perspective on how practitioners within one NSO, the Swedish Floorball Federation (SFF), are interpreting and ‘doing’ sport policy decisions, meaning how they are approaching and negotiating policies of inclusion into practical implementations (Wermke et al. Citation2020). The focus lies specifically on the organizational conditions within the SFF and its context that, in turn, govern and manage club sports, where the realization of inclusion and equal opportunities is sought. The aim is to make these conditions visible, referring to contextual prerequisites or frames, in a pre-stage of doing inclusion. By investigating the pre-stage, conditions regarding the SFF’s preparedness can be identified and changed at an early stage, facilitating the SFF’s continued process towards inclusion.

When the decision on organizational change was made, Parasport Sweden contained 17 sports for people with intellectual, physical, and visual impairments (Parasport Sweden Citation2021). For this study, we chose floorball as the sport due to its organizational characteristics and position in the process. The SFF has an official ambition and vision of being a sport for all and of para-floorball specifically being a natural part of their organization in the future (SFF n.d.). Sweden also has the highest number of registered floorball players in the world and has a large number of non-registered players who engage in the sport on a regular basis, which is estimated to be around half a million practitioners in schools and various associations (Tervo and Nordström Citation2014). With approximately 900 clubs and more than 100,000 registered practitioners, floorball stands as the second biggest team sport in Sweden and the fifth largest NSO (SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation) Citation2022). Para-floorball is also a large sport in terms of practitioners, with an estimated 2,000 licensed players in Sweden (Parasport Sweden 2022). Regarding their position in the process, the SFF is in the pre-stage, preparing the official reception of parasports. The parasport that is to be received in this case is para-floorball, meaning both manual wheelchair and standing floorball (internationally referred to as Special Olympics floorball). The case of the SFF stands as an example of an NSO acting as a receiver of this top-down-initiated process, using organizational change as a new means of ‘doing’ inclusion.

Organizational aspects of inclusion

Jeanes et al. (Citation2018) argue that sports organizations struggle on a structural and institutional level to realize inclusion, identifying a need for future research on the understandings and enactments of inclusion within national and state sporting associations. Wicker and Breuer (Citation2014) suggest that PwDs’ participation in club sports is highly dependent on the clubs’ organizational capacities, such as financial conditions. Additionally, Shields, Synnot, and Barr (Citation2012) argue that one and the same structure or condition can act as both a facilitator and a barrier for PwDs’ participation in physical activity, depending on its construct, for example, supportive/unsupportive peers, sufficient/lacking resources, or conforming/non-conforming values.

Participation is a key word in the CRPD and in general discussions of inclusion. However, policies focusing solely on the participation of marginalized groups are not likely to achieve inclusion because this also demands a change in sports organizations’ practices and cannot be reached only through recruiting new participants (Spaaij, Knoppers, and Jeanes Citation2020). Kiuppis (Citation2018) also states that inclusion and participation cannot be equated with each other because participation does not necessarily mean that inclusion happens. For example, PwD can have the physical possibility to participate in an activity without having the opportunity to interact with other practitioners. Hence, inclusion is not reached, because inclusion also calls for some sort of social interaction to occur and not only for a certain person to be placed in a certain context. Haegele (Citation2019) also stresses the importance of making a distinction between inclusion and placement, referring to inclusion as a philosophy and the term integration as the matter of placement in mainstream settings. Organizational conditions and management have been identified as factors influencing this social interaction in sports that is seen as necessary for inclusion (Elmose-Østerlund et al. Citation2019).

Sørensen and Kahrs (Citation2006) evaluated the inclusion of parasports within mainstream NSOs in Norway, which is similar to the ongoing process in Sweden. This evaluation was carried out among sports organizations on national, district, and local levels. The authors highlighted the importance of organizational preparedness and competence within the receiving organizations, meaning that the need for disability-specific knowledge had not been taken seriously enough. The authors also suggested that a combination of an organizational top-down and bottom-up strategy, rather than just stressing change from above, could anchor the process in the organizations and allow it to develop over time. A main challenge identified by Sørensen and Kahrs (Citation2006) was that para-athletes, being a clear minority in the receiving organization, only become accepted in mainstream sports if they fit the pattern of already existing norms and values among the mainstream majority. Thus, the inclusion process runs the risk of becoming a conversion or assimilation process.

Adaptations of values and cultures in mainstream sports are seen as essential or achieving inclusion (Howe Citation2007; Kitchin and Howe Citation2014). In the mainstreaming process of cricket for PwD in England and Wales, these adaptations were not realized, and cricket for PwD did not become a prioritized part of mainstream sports, leading to the receiving organization merely accommodating the parasport organization, not actually including it (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014). The same thing was true in the case of integrating Paralympic athletes within Athletics Canada, where the process ‘got stuck’ at the point of accommodation (Howe Citation2007). In line with Kiuppis’s (Citation2018) and Haegele’s (Citation2019) argumentations, realizing inclusion clearly demands more than just participation or placement in a certain context, such as organizational accommodation. Further, Kitchin and Howe (Citation2014) have argued that a factor contributing to this state of only accommodating parasports could be that the receiving organization’s motives are based on institutional pressure, such as the pressure to follow political guidelines, and not a desire to include parasports. Hence, processes of change stemming from hierarchical decisions, such as the top-down-initiated process at hand, run the risk of leading to failed inclusion.

In contrast, strong governance and initiatives from head organizations in sports are needed because a lack of governance is a challenge for goal achievement (Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006; Karp, Fahlén, and Löfgren Citation2014). This has been seen before in the Swedish sports context through previous efforts to open sports for more participants, such as the government-initiated and government-funded initiatives Handshake [Handslaget] and the Lift for Sports [Idrottslyftet]. These initiatives were designed in a similar way as the ongoing process of inclusion, where governing organizations gave quite open directives for different equality-seeking initiatives (Karp, Fahlén, and Löfgren Citation2014; Patriksson et al. Citation2007). This low degree of steering gave the NSOs and clubs a high degree of freedom where change was stressed from above, but the way it was to be conducted was up to individual organizations and the responsibility was pushed down in the hierarchy (Karp, Fahlén, and Löfgren Citation2014).

Aim and contribution

What we can claim to know from previous research is that organizational conditions and capacities play a decisive role in the outcome of inclusive efforts. For example, in a top-down governed process, mainstream organizations’ own motives for inclusion can be limiting conditions (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014). However, organizational changes for providing PwD with equal opportunities have previously been studied in a late or final stage and then discussed in terms of results and goal achievement (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014; Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006). Therefore, many of these organizational conditions and capacities are first made visible after the implementation of said effort in the search for reasons and explanations for failing to reach inclusion or equal opportunities. Furthermore, failure to reach inclusion connects to a lack of conditions and capacities, where some have argued that a reconstruction of lacking conditions could bring facilitatory conditions (Shields, Synnot, and Barr Citation2012).

Therefore, this study aims to make visible organizational conditions within the Swedish Floorball Federation in the pre-stage of inclusion of para-sports in order to enable their reconstruction and bring further knowledge about facilitation of equal conditions. Furthermore, by investigating the pre-stage of this process, we aim to precede lessons learned, contributing a new perspective on how organizational inclusion of parasports is done in practice. This article intends to do so from a structural level within sports’ national governing bodies, as some have previously argued to be a field in need of further research (Jeanes et al. Citation2018). In addition, following one specific NSO as a case in a large-scale mainstreaming process is a new approach in the field. The following question guides the research:

What conditions exist within the Swedish Floorball Federation and its context, and what opportunities and challenges do they bring for the process of including parasports?

Frame factor theory

To analyse conditions for a process of inclusion within a sports setting, this article draws on frame factor theory. Originally developed by Dahllöf (Citation1967, Citation1971) and Lundgren (Citation1972, Citation1979) in an educational context, the theory is a process model to ‘study how a frame, or a combination of frames, impacts the pedagogical processes that lead to results in different dimensions’ (Dahllöf Citation1999, 10). The theory has since been developed and applied in different pedagogical contexts, such as within police education, physical education, and club sports (Bäck Citation2020; Karp and Renström Citation2018; Karp and Stenmark Citation2011; Lundvall and Meckbach Citation2008). In a sports context, Nilsson (Citation1988) designed a theoretical model of frame factor theory to understand how individuals in sports clubs construct and adapt to the social sports practices of which they are a part. Karp and Renström (Citation2018) later drew on this model to contextualize the day-to-day activities in sports clubs in connection with policy implementations. Being developed especially for sports pedagogical settings, this study draws on Nilsson’s (Citation1988) version of frame factor theory. Of central importance for inclusion research are the ‘mechanisms of inclusion that operate within sporting environments’ (Kiuppis Citation2018, 5). Frame factor theory strives to explain how society is recreated by investigating the mechanisms that steer its content and structures (Nilsson Citation1988). An important part of the theory for this study is that it distinguishes between the organizational limitations (frames) and the values (contextual ideology) of sports, which can be likened to practice and policy, at the same time that it offers explanations on how these two dimensions influence each other and work together in the creation and recreation of daily actions and value systems (patterns) as those of inclusion. Additionally, the theory also seizes both organizational and individual perspectives, which is important in this study because the analysis is based on individuals’ conceptions of the organization they represent. Frame factor theory contains the three main dimensions of frames, contextual ideology, and patterns, which, in this study, helps to analyse the conditions that exist in the SFF’s context on an organizational level and how they limit and enable the process of inclusion of parasports.

Frames

In this study, frames are the structural or organizational conditions that exist within the SFF and its contextual surroundings. Lundgren (Citation1979) and Nilsson (Citation1988) described three types of frames. First, there are constitutional frames, which are laws and regulations within the context, such as decisions or guidelines from the SSC. Second, organizational frames are considered as consequences of the constitutional frames, such as priorities and the allocation of resources. Third, physical frames refer to material resources such as availability and access to sports arenas or equipment.

Contextual ideology

Contextual ideologies are conceptions in the context, in this article meaning federation and district representatives’ conceptions about goals and purposes of sports. It includes formal and informal values that are conceptions about shared and expressed values in the context, for example, content in policy documents and individual or shared values that do not emerge in official documents in sports (Karp and Renström Citation2018). Contextual ideologies also include rational and fostering goals, which are described as conceptions about practical skills or other goals that aim to develop the athlete within their sport and the norms and values that the context presumes, such as sports as a means to foster good citizens (Nilsson Citation1988).

Patterns

The pattern adapts to and is constantly recreated by its context’s frames and ideologies. Patterns concern the context’s daily practices, meaning everyday life in sports organizations. Patterns contain structure, function, and methodology, which, in this order, can be described as who is included and excluded through existing structures in sports, what function sports fill or what their purpose is, and how the daily sports practice is organized and conducted (Nilsson Citation1988). The individuals in the organization participate in processes where values regarding desirable and undesirable behaviours and attributes are constructed, and the individual’s ability to adapt to these values will affect the extent to which they are included or excluded in the context ().

Table 1. Understanding frame factor theory in a sports context (based on Nilsson Citation1988).

Methods

The SFF’s steering mechanisms of inclusion, referred to as conditions, are, in this study, considered to have an enabling and/or limiting nature, bringing opportunities and/or challenges. Opportunities refer to respondents’ conceptions about what is thought to be beneficial for and through the inclusion process. Challenges mean respondents’ conceptions about experienced obstacles for and through a process of inclusion.

Sample and data collection

Through a targeted selection (Bryman Citation2016), the conceptions explained above have been studied on both federation and district levels within the SFF. While the NSOs’ federations are the main governing organizations within each sport, their districts are assigned to represent, coordinate, and support the NSOs’ operations on a regional and local level in order to contribute to sport development. The federation’s board consists of those who are ultimately responsible for organizational conditions and strategic decisions regarding the inclusion process, while the staff work operationally to turn these decisions into actions and activities. The SFF’s 20 districts act as the federation’s extended arm towards the non-profit clubs and are therefore important actors in support of and communication with the clubs regarding the inclusion process. Participation of district representatives in the study provides an idea about conditions and preparedness in different districts and, thus, different conditions in the SFF’s clubs. These respondents are all stakeholders on different strategic levels in the inclusion process, which strongly connects to frames and contextual ideology in the theoretical framework. The connection to patterns will be viewed through their conceptions on the club and athlete level, meaning daily practices in sports.

This study combines quantitative questionnaires with qualitative semi-structured interviews (Bryman Citation2016). The respondents for questionnaires and interviews were chosen from two different samples based on the different aims of the data collections. Questionnaires were used to reach a large number of possible participants and to obtain an overview of the SFF’s current status, while interviews were needed to obtain deeper and more nuanced responses from those identified as having a role directly responsible for matters of the inclusion process.

Online questionnaires were sent to all board members as well as SFF employees and to those listed as contacts or staff in the districts’ official web pages in the 20 districts. Semi-structured interviews (Bryman Citation2016) were conducted with four representatives from the board and office of the federation, as well as with chairpersons in 18 out of 20 districts.

Procedure and data analysis

Questionnaires

With a deductive approach (Bitektine Citation2008), numerous themes and questions were formulated to capture the theory’s dimensions of frames, ideologies, and patterns, and thereafter adjusted into a questionnaire. The questionnaire was then modified and adjusted to the respondents’ organizational levels, meaning the federation’s board, the federation’s staff, and district representatives. The themes revolved around the organization’s current conditions regarding the inclusion of para-floorball and possible future outcomes and results. Examples of questions asked include, ‘To what extent do you believe that the inclusion of para-floorball will affect and influence mainstream floorball?’ The questions were to be answered on a scale of one to five, with the exception of opening questions about the respondents’ background in floorball and an open comment section at the end. Only three respondents left additional comments which did not contribute any new findings but merely supported the answers already given, which is why they are not presented in the results. The online questionnaires were distributed via email together with information about the study’s purpose and voluntary participation. To enable truthful answers regarding attitudes towards inclusion, the questionnaires were answered anonymously. The questionnaires sent to federation representatives generated 29 responses out of 41 distributed questionnaires and a response rate of ≈ 71%. Among district representatives, 69 questionnaires were distributed, generating 26 responses and a response rate of ≈ 38%. For the analysis of quantitative data and for creating figures, IBM SPSS Statistics 26 was used.

Interviews

Three interview guides were created based on the respondents’ organizational roles, with the same overarching themes. The interview guide was designed and questions were formulated with regards to frame factor theory’s dimensions, even though the nature of the semi-structured interviews allowed the conversation to flow between themes and questions to integrate them with one another (Bryman Citation2016). Examples of questions asked included, ‘To what extent is the inclusion process currently a priority in your organization?’ and ‘What supporting structures regarding the inclusion process exist within your organization?’ The interviews were conducted via phone and were approximately 30 to 65 min long. The interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim. NVivo 12 was used as a software tool for analysing the qualitative data. In NVivo, themes, or nodes (Bryman Citation2016), were composed by the previously formatted central areas in the study of opportunities and challenges. Due to the study’s deductive approach, quotes from the data were coded into these themes and then subdivided into underlying nodes according to the frame factor theory’s frames, contextual ideology, and patterns, as presented in the results. To ensure no relevant aspects of the material had been overlooked, two researchers independently reviewed the codes and the coded data, acting as ‘critical friends’ (Smith and McGannon Citation2018). This means that the researchers opened up a critical dialogue regarding their interpretations, providing a ‘theoretical sounding board’ for one another when comparing annotations (Smith and McGannon Citation2018). Differences that arose were discussed and reflected upon in order to reach a collective agreement on the coding.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Swedish Research Council’s (2017) guidelines on good research practice. It is part of a larger study that the Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved (Dnr 2020-05067). All participants submitted a written or oral confirmation of approval to participate in the study, that is, an informed consent (Swedish Research Council Citation2017). Participants were informed about when audio recording started and ended. All interviews were conducted and transcribed by the first author, who also translated the quotes from Swedish into English. In this process, the participants’ names received codes, and all names mentioned were replaced before uploading the quotes to software tools for analysis in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (European Union Citation2016). The use of the term ‘persons with disabilities’ conforms to ‘people-first language’ used by multiple authorities in the disability context (e.g. UN (United Nations) Citation2006; WHO (World Health Organization) Citation2001), where the person or athlete is valued first, leaving disabilities to be of secondary importance.

Results

The results are here presented according to the main dimensions of frame factor theory.

Frames

Frames highlight contextual conditions for the organization in question that can be enabling and/or challenging for its functions. The results regarding frames predominantly show challenging conditions for including para-floorball.

The results show that there are limiting constitutional frames regarding decision-making and guidelines from central organizations, creating challenges for the inclusion process. This can be seen in the interviews as federation representatives inquire for more directives and governance from SSC and Parasport Sweden. Currently, there are insecurities about whom the SFF should turn to regarding the inclusion process and who is responsible, which can be traced back to the decision of inclusion in 2017.

The decision was applauded by everyone because it was politically correct, but very few of those who were sitting there applauding had the ability and knowledge to understand what it meant. And most of all it was a little bit like ‘well now we have made the decision, here is the organization, good luck’ (…) I think they took the decision too lightly, they should have looked at this consequence- and action-plan a lot more seriously.- Federation representative 3

District representatives, in turn, ask for clearer directives and information from the SFF. In the interviews, they express a need to know what is expected of them in the process, for example, regarding what activities they should offer for PwD and to what extent. Due to organizational differences, the SFF’s districts are in different positions in the process, and among some districts, there are insecurities regarding what parasport is and hence, what the inclusion means. The respondents see a risk that these differences and lack of directives will bring every individual district to decide their own guidelines and regulations regarding what should be achieved and how the work should be done.

When [the inclusion process] is knocking on the door and SFF doesn’t have a strategy ready, then the districts might deal with it on their own and create their own solutions (…) some districts have come further than others, and when everyone is running in different directions and in different speed, I think that it rarely turns out well.- District representative 12

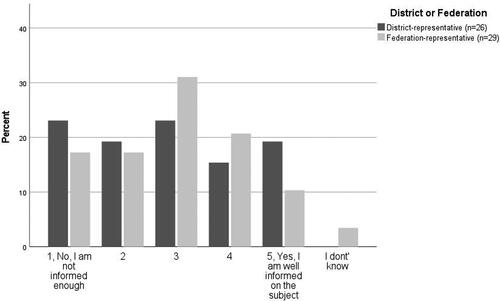

A general concern in the interviews, and something that most certainly shapes the constitutional frames and decision-making process, is that an increased competence is needed within all levels of the SFF concerning para-floorball, but also about the inclusion process and how it will be conducted. In the questionnaire to federation as well as district representatives, the question was asked whether the respondent could explain what the inclusion process meant. As seen in , the answers were widespread regarding both the SFF and the district level.

Figure 1. To what extent federation and district representatives consider themselves able to explain the meaning of the inclusion process.

Despite differences in knowing the meaning of the change process, respondents of the interviews see an opportunity where increased inclusion could lead to increased resources regarding sponsorship. This is based on the idea that companies and sponsors nowadays want to be associated with good values, not only good performance. Including parasports could count as being part of corporate social responsibility, and thereby, give political credit to floorball for being inclusive. Further, the biggest opportunity regarding organizational frames according to the respondents is that floorball as an organization will grow with new practitioners, thereby making the ‘floorball family’ a greater organization.

From the interviews, it is clear that there are different understandings among the respondents about organizational frames within the SFF that can bring either opportunities or challenges for the inclusion process. On one hand, floorball is seen as a young and modern federation with less set structures and an innovative board, which favours value and equality work. On the other hand, some respondents mean that there is a structure and culture with a low tendency to change within sports in general, where floorball is no exception, which could complicate change and development work.

As a result, or from adopting the low governance within constitutional frames, information and resource allocation are also considered challenges. Here, federation representatives, in difference to district representatives, do not speak so much about a lack of economic resources as they do about guidelines concerning economy. Several respondents describe uncertainties regarding resources, which comes from ambiguity within the SSC and Parasport Sweden regarding what applies. To ensure sufficient resources for parasport within the receiving NSOs, clear action, consequence, and time plans are requested in connection to the letter of intent that will be written between the SFF and the SSC:

A plan of action Is needed in order to first discuss economic conditions, it is always important to talk about, you can’t pretend that they are not important. The money that existed for para-floorball, will they be transferred? Will they not be transferred? How will this be handled?- Federation representative 4

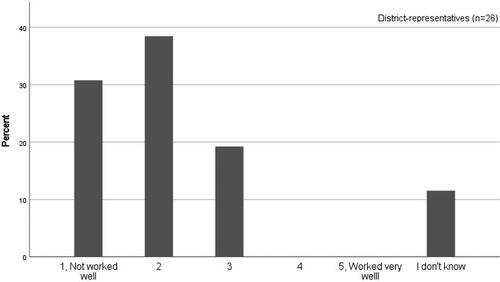

Figure 2. Conceptions on the district level regarding how well the SFF has carried out information about the inclusion process.

Another challenge seen as a result from the constitutional frames is a fear that parasports will ‘disappear’ when becoming part of a larger organization. According to several respondents of the interviews, there is a risk that parasports and para-athletes will receive less attention or priority when there no longer exists an NSO that looks out for their interests collectively. There is a knowledge and a sense for parasports within Parasport Sweden that runs the risk of disappearing through the transition to the SFF.

A danger for parasports could be that they become such a small part of our organization that they disappear in the rest. That’s a danger I would see if I was on that side. That can’t happen, because they have built something already and want to develop that, not get marginalized and disappear in a bigger organization.- District representative 5

A reoccurring concern in the interviews is that the SFF’s 20 district associations all have different conditions to operate and manage their activities due to differences in size, number of employees, clubs, active participants, and so on. Following this, they also have different conditions to work with the inclusion process, which, according to the districts’ chairpersons, will create differences regarding how the inclusion process will be conducted, as well as what will be achieved, in both the short and the long term.

The question about material or physical resources is especially prominent in the interviews on district level where outdated venues, lack of practice hours, and inaccessible sports arenas are brought forward as limitations for activities. The organizations’ adaptations of physical environments are considered as needed to enable participation for all members and practitioners.

In summary, the frames mainly consist of limiting conditions such as uncertainties about resources and responsibilities. The most salient condition regards governance and decision-making in connection to the inclusion process where the respondents request further information and competence in the matter.

Contextual ideology

This dimension consists of values and goals of the context, both collective and individual, and official and informal. As opposed to frames, contextual ideology mainly reflects opportunities for including para-floorball.

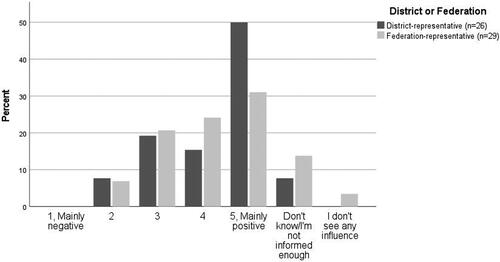

Overall, the respondents of both interviews and questionnaires have positive views on para-floorball and its inclusion. This is for example seen in the questionnaire on both the federation and the district level, where it was asked how the respondents view the inclusion process’s influence on Swedish floorball, and respondents answered that the influence would be mainly positive. No one answered that it would be mainly negative ().

Figure 3. Perceptions among federation and district representatives regarding the inclusion process’s influence on Swedish floorball.

However, concerning the phenomenon of inclusion, there are different ideas and conceptions, or informal values, on what it means, which leads to a fear that it is unreachable. This is seen in the interviews where being organizationally included is one thing, but to reach inclusion on a deeper level, which is expressed to be the desired situation, is seen as a challenge. A federation representative uses the term ‘total inclusion’ to describe a state where the included target group has the opportunity to influence the organization and its decisions. This can sometimes be seen as an unreachable goal within sports.

Sometimes when we talk about inclusion it feels like a utopia, I think it is very difficult to achieve and maybe especially for sports, since sports is based on a very non-inclusive idea (…) the question is if we will succeed with inclusion, because then we also must widen the norm from these athletes as well.- Federation representative 1

As a fostering goal, there is a consensus among the respondents of the interviews that including para-floorball will change some existing ideas and perceptions of floorball for the better. Mainstream floorball, which is played five against five, is viewed as the ‘real’ floorball, and including para-floorball will challenge this view and norm about how the sport should be played and how a player should be. Respondents express a hope that this will facilitate including other marginalized groups because the new and widened norm will be able to hold more people. A widened norm is also considered a step for the SFF towards being a sport for all.

We have a strategic goal or vision to be a sport for all, so of course it’s positive for us to get the opportunity to include para-floorball (…) It will be really great with new perspectives and possibilities to broaden the concept of floorball, because that concept is pretty slim for a lot of people.- Federation representative 1

In summary, contextual ideology mostly contains perceptions of benignity towards the inclusion process, and an idea that it will bring widened norms and positive influences on floorball. Limiting conditions are also shown in the shape of a discrepancy in the way the respondents view the meaning of inclusion.

Patterns

The concept of patterns refers to the everyday life and practices in sports. Frames and ideologies shape and re-shape the patterns in a constantly ongoing process. Through mirroring the results shown in frames and ideologies, the patterns consist of a mixture of opportunities and challenges for the inclusion process.

Regarding the contextual ideology and the idea of widened norms, broadening the ideal of floorball players is not just beneficiary for floorball as a federation or sport, but also on an individual level according to interviews. Through belonging to the same organization and being closer to one another, athletes with and without disabilities will learn about and gain respect for each other, which in the long run, creates a more tolerant and prosperous society. Through not separating the two organizations and their activities, it is shown to first and foremost the children and youth without disabilities, that PwD can participate on equal conditions and not be ‘hidden away’, as a federation representative expresses it.

However, norms are also seen as a challenge in including marginalized groups. Ideas about capacities and current ideals create different thresholds for including athletes with different types of disabilities in the daily practices. There is also an experienced difference in status between mainstream and para-floorball appearing in the interviews, where mainstream floorball and its athletes have a higher standing in the hierarchy. This is expected to change through the inclusion process but is also expected to be a protracted process.

Different is maybe the wrong word, but I think that for the foreseeable future, we will see para-floorball and mainstream-floorball as different activities, and within a foreseeable future, mainstream-floorball will be the norm and thereby higher in the hierarchy somehow, with both prerogative of interpretation and more power. The goal has to be to decrease this difference over time, but it would be naive to think that you just do it and that it goes fast, I think it’s a really long process.- District representative 4

Belonging to different federations, mainstream and para-floorball is generally managed and conducted in different clubs. In the daily organization of sports, respondents of interviews see an opportunity for families with children both with and without disabilities. The inclusion can mean an improvement for these families where siblings who previously have practiced floorball in different clubs now might be able to belong to and practice in one and the same. Some positive effects of this unity on the club level have already been seen where some athletes have gone from practicing on a team for para-floorball to practicing with a mainstream floorball team. This probably would not have happened if the two teams had not belonged to one and the same club and organization. This way, as a result of contextual ideology and more specifically, rational goals, the inclusion enables multiple options for PwD to participate in mainstream sport. Regarding the scarce resources that are mentioned as an organizational frame, respondents also see practical advantages for the districts to merge floorball activities, such as the possibility to use the same referees and volunteers in games for both mainstream and para-floorball.

As a result of the low level of knowledge appearing in the constitutional frames, some respondents of the interviews fear that correct competence and preparedness do not exist within the SFF’s different organizational levels to organize para-floorball. PwD are feared to be the ones who will be affected by this ignorance if clubs cannot handle or meet different types of needs.

Challenges and obstacles are that the receivers are not ready, neither resource-wise nor knowledge-wise, and that is a major challenge when it is just thrown over. It sounds so politically correct, and it is the right thing to do, and I think that it is great, but I see a big danger in the fact that you just keep going, because what happens when suddenly a girl or a guy in a wheelchair shows up and the person dropping them of think that they can just drop them off? The receiver has no idea how to handle that.- Federation representative 4

In conclusion, patterns show that the frames and contextual ideology can bring opportunities for the daily practices and the athletes in it, such as a better usage of resources and more opportunities for PwD’s sports participation. Patterns also present challenges brought to the daily practices in the shape of the club’s unpreparedness to meet different needs.

Discussion

In this section, we initially discuss the conditions that emerged within the SFF and then turn to their suggested impact in the shape of opportunities and challenges for the inclusion process. When analysing the results of the pre-stage of doing inclusion through frame factor theory, there are mostly challenges that appear regarding frames. However, the contextual ideology with values and ideas about the inclusion process shows mainly opportunities, which, in turn, brings a mixture of challenges and opportunities in the patterns for including para-floorball. Possible reasons for this distribution are also discussed.

First, we recognize the study’s limitations: the case of the SFF has its own characteristics such as being a team sport, being one of the biggest NSOs in Sweden, having an expressed benignity towards inclusion, and so forth. Organizational differences among NSOs bring differences in the conditions for the inclusion process. However, studying a specific NSO as a case brings opportunities for a deeper understanding of conditions within a specific context and the opportunities and challenges that follow, which is this article’s focus.

The results identify organizational shortcomings on federation and district levels within the SFF as challenges for inclusion in accordance with Jeanes et al. (Citation2018). For example, there are limiting frames in the context in the form of existing organizational structures for decision-making and governance. The lack of governance regarding what should be achieved through the inclusion process and how this inclusion should be done is expressed on structural levels within the SFF. This might not be a surprising result in a pre-stage of doing inclusion, but it seems especially important to highlight considering the findings about the district’s different conditions where identifying this in the pre-stage provides opportunities for taking measures to minimize the expressed risk of the districts going their separate ways in the process.

Considering the hierarchical governance that is the nature of Swedish sports management, this inclusion decision is no exception. Responsibility is distributed downwards along the organizational hierarchy, at the same time, directives and information are sought upwards through the hierarchy from those on whom the responsibility is placed. This points to a deficiency in the top-down structure regarding delegation where responsibility travels faster than, or completely without, directives. Goal achievement will most likely be challenging for the SFF and its different organizational levels if these directives and aims are not communicated (Karp, Fahlén, and Löfgren Citation2014; Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006). For example, thoughts that inclusion is an unreachable goal were expressed, where the description of inclusion as a utopia could be the result of a lack of knowledge regarding responsibilities and implementations. Enabling bottom-up initiatives as supplemental to top-down decisions could make for a better foundation among the different organizational levels (Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006). This foundation could decrease the risks of the ‘lower’ levels simply acting on institutional pressure and not having a wish for inclusion among themselves (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014).

There is a consensus within the SFF at both the federation and district levels that including parasports is desirable. Many see the inclusion process as a step towards opening floorball for more groups or individuals and thereby getting closer to the SFF’s formal goal and vision, that is, equal conditions for everyone to practice sports (SFF 2020). This existing ideology enables a united sports movement behind the decision to include parasports in the NSOs, where the contexts’ shared values, meaning the SFF’s and SSC’s visions and policies, strive for inclusion in accordance with the CRPD (SFF 2020; SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation) Citation2019a; UN (United Nations) Citation2006). A desire for inclusion behind a decision of mainstreaming is a prerequisite for inclusion to be realized (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014), making this ideology an enabling frame.

Some of the limiting frames on an organizational level can create opportunities in this process, in accordance with Shields, Synnot, and Barr (Citation2012), such as the physical frames where venues and other resources are scarce. Even though limited resources are considered a challenge for the inclusion process, merging para-floorball could also bring opportunities regarding resources where the same resources, such as referees, can be used for both purposes. If managed correctly, this brings opportunities for shared and better distributed resources. If not, organizational shortcomings can be a barrier in sports participation for PwD and thus can limit possibilities for inclusion (DePauw and Gavron Citation2005; Elmose-Østerlund et al. Citation2019). Stemming from this idea that every frame can be enabling and/or limiting depending on the frame’s shape or form (Shields, Synnot, and Barr Citation2012), there is a need for future research to investigate the possibilities of change in current limiting frames, rather than development of new enabling ones. If challenges are faced from this perspective, every problematic condition could also contain its own solution. Lack of competence would be reconstructed to increased competence, weak governance would be solved with stronger governance, and so on. This might seem like an obvious statement, but the nature of this and previous initiatives for change have rather focused on creating and offering new activities and new solutions instead of facing the original problems and reconstructing existing limiting conditions. By making these limiting conditions visible in the pre-stage, this article contributes to problem-solving tactics in future organizational efforts towards equal opportunities for sports participation for all.

The respondents hoped that the inclusion would lead to broadened norms that will be seen in daily sport practices, that it will spread outside sports, and that it will lead to a more open and inclusive society. Changed attitudes and changes in values and culture have been proven to be essential in achieving inclusion and avoiding the ‘accommodation trap’ (Howe Citation2007; Kitchin and Howe Citation2014). However, to enable this opportunity for changed norms in daily practices when receiving para-athletes at the club level, the lack of parasport-specific competence that is shown in the results needs to be addressed (Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006). Knowledge and awareness about parasports and disabilities are necessary competences for a receiving NSO to adjust its values and norms to include the minority that is parasports and not just convert it (Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006).

For the SFF to have set goals and to measure some type of goal completion in this process, another question in need of an answer is what the concepts of equal opportunities and inclusion refer to in this practice. The results show a discrepancy in how the respondents perceive inclusion, pointing to a lack of consensus on the matter and creating challenges for a united effort towards a common goal. Previous research seems to agree that inclusion means more than physical placement to enable participation in a specific setting (e.g. Haegele Citation2019; Kiuppis Citation2018) However, looking at previous initiatives for change in the Swedish sports system (e.g. Karp, Fahlén, and Löfgren Citation2014; Patriksson et al. Citation2007), the concepts of inclusion and accessibility have been equated with recruitment and participation rates. Aiming simply towards recruitment with the ongoing process might lead not only to failure to reach inclusion (Spaaij, Knoppers, and Jeanes Citation2020) but also to organizations possibly choosing the easy option through assimilating new participants, thereby risking further marginalizing PwD (Sørensen and Kahrs Citation2006). In contrast, recognizing inclusion as being realized when new values have paved the way for a change in norms and culture (Kitchin and Howe Citation2014) is difficult to measure. There might not be a challenge-free definition of the term inclusion, but a united definition could make risks and challenges visible and improve opportunities for a collective effort towards inclusive sports.

As initially declared in this discussion, the contextual ideologies with the values and goals of sport show mainly opportunities, whereas the frames seen as the actual organizational conditions of the SFF show a considerate number of challenges. An interpretation of this is that, in the pre-stage, the respondents generally carry a positive view of the idea of including parasports in theory, but they hold a critical view on how it is or will be handled in practice on an organizational level. A further interpretation, as several respondents mentioned, is that the idea and concept of including parasport is undefined. Inclusion is considered correct and to align with formal values, but there is much uncertainty regarding what it means. The requests for better conditions regarding governance, resources, and competences seem to be rooted in this insecurity regarding not only how the inclusion process will be implemented but also what will be received through it. In the interviews, a wide range of ideas appear regarding it being a transfer of an organization and economic resources, competence, new norms, athletes and new members, or practical sports activities. The desire to follow formal values might be why the contextual ideologies consist of such positive views on inclusion, and why the organizational frames mainly consist of critical ones. Unsurprisingly, formal values are followed in a pre-stage where other ideologies might not exist, and questioning the ideology of which an individual is a part would be a contradictory action. However, this means that no one dares to raise their hand and ask not only the question of what inclusion means, but also the question of how it should be done and what is to be received in the process.

Conclusions

In relation to the research question, this study, with the help of frame factor theory, makes a methodological contribution on how to identify conditions for doing inclusion in a pre-stage of change. Through the chosen theory, the present results can be seen to pre-identify, and give partial explanations for, challenges and opportunities for inclusion within the SFF and the effort for equal opportunities for participation. For example, the study identifies limiting conditions regarding the lack of governance and information about the process, which leads to insecurities regarding responsibilities, resource allocation, and what is to be received in the process. Enabling conditions are also identified, such as opportunities for changed norms and attitudes within mainstream floorball, paving the way towards the SFF’s vision of being a sport for all. This is valuable in the continued mainstreaming process, as well as for future research, because it prompts scholars and policymakers to think about how inclusion is done in practice and the importance of pre-stage evaluations in order to enable reconstruction of limiting conditions to facilitate equal conditions for PwD in sports.

An especially pressing issue appears in definitions of what this inclusion process means and what is to be received through it, where the results convey different conceptions. Similar to how limiting conditions, such as scarce resources, can bring opportunities for the process, enabling conditions can lead to challenges in daily practices. This is seen where a desire to follow contextual ideologies and their formal values leads to insecurities regarding the process and its meaning. The question of what is embedded in the concept of including parasports in practice is yet to be answered.

Finally, frame factor theory’s final dimension of patterns debouches in the daily practices of sport, meaning the club and athlete levels. Because this is where inclusion is meant to be realized, it would be valuable to follow the organizational hierarchy down to the club level to shed more light on the matter. Here, the athlete’s thoughts and experiences of the process would be made visible. If this organizational change aims for athletes to have equal opportunities in their daily practices, they should have a say in the matter of composing goals and definitions of how and when this is achieved in sport. Another important perspective for future research to consider is that of parasport representatives. In discussing conditions for inclusion, those involved in parasport on a national, regional, and local level could most certainly contribute with knowledge regarding which conditions are needed for the successful reception of parasports and athletes. This would also add a dimension of comparability between the para- and mainstream organizations, showing possible discrepancies in conceptions of the conditions needed for doing inclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bitektine, A. 2008. “Prospective Case Study Design: Qualitative Method for Deductive Theory Testing.” Organizational Research Methods 11 (1): 160–180. doi:10.1177/1094428106292900.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bäck, T. 2020. “From police education to police practice: police students’, and policeofficers’ perceptions of professional competences.” PhD diss., Umeå University.

- Dahllöf, U. 1967. Skoldifferentiering Och Undervisningsförlopp [School Differentiation and Teaching Processes]. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell.

- Dahllöf, U. 1971. Ability Grouping, Content Validity and Curriculum Process Analysis. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Dahllöf, U. 1999. “Det Tidiga Ramfaktorteoretiska Tänkandet: En Tillbakablick.” Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige 4 (1): 5–29.

- Darcy, S., and T. Taylor. 2009. “Disability Citizenship: An Australian Human Rights Analysis of the Cultural Industries.” Leisure Studies 28 (4): 419–441. doi:10.1080/02614360903071753.

- DePauw, K. P., and S. J. Gavron. 2005. Disability and Sport. 8th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Elmose-Østerlund, K., Ø. Seippel, R. Llopis-Goig, J. W. Van der Roest, J. Adler Zwahlen, and S. Nagel. 2019. “Social Integration in Sports Clubs: Individual and Organisational Factors in a European Context.” European Journal for Sport and Society 16 (3): 268–290. doi:10.1080/16138171.2019.1652382.

- European Union. 2016. “Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council.” Official Journal of the European Union, 59: 89–131. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L0680&from=EN.

- Haegele, J. A. 2019. “Inclusion Illusion: Questioning the Inclusiveness of Integrated Physical Education: 2019 National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education Hally Beth Poindexter Young Scholar Address.” Quest 71 (4): 387–397. doi:10.1080/00336297.2019.1602547.

- Howe, P. D. 2007. “Integration of Paralympic Athletes into Athletics Canada.” International Journal of Canadian Studies (35): 133–150. doi:10.7202/040767ar.

- Jeanes, J., R. Spaaij, J. Magee, K. Farquharson, S. Gorman, and D. Lusher. 2018. “Yes We Are Inclusive’: Examining Provision for Young People with Disabilities in Community Sport Clubs.” Sport Management Review 21 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2017.04.001.

- Karp, S., J. Fahlén, and K. Löfgren. 2014. “More of the Same Instead of Qualitative Leaps: A Study of Inertia in the Swedish Sports System.” European Journal for Sport and Society 11 (3): 301–320. doi:10.1080/16138171.2014.11687946.

- Karp, S., and A. Renström. 2018. “Sport for Adults: Using Frame Factor Theory to Investigate the Significance of Local Sports Instructors for a New Sport for All Programme in Sweden.” Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum 9: 87–109.

- Karp, S., and H. Stenmark. 2011. “Learning to Be a Police Officer. Tradition and Change in the Training and Professional Lives of Police Officers.” Police Practice and Research 12 (1): 4–15. doi:10.1080/15614263.2010.497653.

- Kitchin, P. J., and P. D. Howe. 2014. “The Mainstreaming of Disability Cricket in England and Wales: Integration ‘One Game’ at a Time.” Sport Management Review 17 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.05.003.

- Kiuppis, F. 2018. “Inclusion in Sport: Disability and Participation.” Sport in Society 21 (1): 4–21. doi:10.1080/17430437.2016.1225882.

- Klenk, C., J. Albrecht, and S. Nagel. 2019. “Social Participation of People with Disabilities in Organized Community Sport.” German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 49 (4): 365–380. doi:10.1007/s12662-019-00584-3.

- Lundgren, U. P. 1972. “Frame Factors and the Teaching Process. A Contribution to Curriculum Theory and Theory on Teaching.” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg.

- Lundgren, U. P. 1979. Att Organisera Omvärlden. En Introduktion till Läroplansteori [To Organize the Outside World: An Introduction to Curriculum Theory]. Stockholm: Liber.

- Lundvall, S., and J. Meckbach. 2008. “Mind the Gap: Physical Education and Health and the Frame Factor Theory as a Tool for Analysing Educational Settings.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 13 (4): 345–364. doi:10.1080/17408980802353362.

- Nilsson, P. 1988. Tävlingsidrotten Som Uppfostringsmiljö: Regelefterlevnad Inom Idrotten – En Teoretisk Referensram [Competitive Sports as Fostering Arena]. Stockholm: Institutionen för Pedagogik.

- Nordlund, M., K. Wickman, S. Karp, and L. Vikström. 2022. “Equal Abilities – The Swedish Parasport Federation and the Inclusion Process.” Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum no. 13: 111–129.

- Patriksson, G., O. Stråhlman, S. Eriksson, and L. Kristén. 2007. “Handslaget – Från Idé till Utvärdering. Om Projekt, Ekonomi Och Verksamhet.” Svensk Idrottsforskning 3 (4): 22–28.

- Parasport Sweden 2021. ” Om inkluderingsprocessen.” Accessed 11 October 2022. https://www.parasport.se/Drivaochutveckla/idrottsforbund/Ominkluderingsprocessen/

- Parasport Sweden 2022.” Kartläggning paraföreningar” [Mapping Para-Clubs]. [Unpublished raw data]. Swedish Floorball Federation, November 9.

- SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation). 2019a. “Idrotten vill.” Accessed 5 October 2022. https://www.rf.se/download/18.7e76e6bd183a68d7b71179c/1664978259581/Idrotten%20Vill%20%E2%80%93%20Idrottsr%C3%B6relsens%20id%C3%A9program.pdf

- SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation). 2019b. “Strategi 2025: Fem utvecklingsresor.” Accessed 23 September 2022. https://www.strategi2025.se/Strategi2025/Femutvecklingsresor/

- SSC (Swedish Sports Confederation). 2022. “Idrottsrörelsen i siffror.” Accessed 29 April. https://www.rf.se/globalassets/riksidrottsforbundet/nya-dokument/nya-dokumentbanken/idrottsrorelsen-i-siffror/2021-idrotten-i-siffror–-rf.pdf?w=900andh=700

- Shields, N., A. J. Synnot, and M. Barr. 2012. “Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity for Children With Disability: A Systematic Review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 46 (14): 989–997. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-090236.

- Sørensen, M., and N. Kahrs. 2006. “Integration of Disability Sport in the Norwegian Sport Organizations: Lessons Learned.” Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 23 (2): 184–202. doi:10.1123/apaq.23.2.184.

- SFF (Swedish Floorball Federation). “ 2020. Om Svensk Innebandy: I dag och i framtiden.” Accessed 20 September 2022. https://www.innebandy.se/om-svensk-innebandy/i-dag-och-i-framtiden/

- SFF (Swedish Floorball Federation). Svensk Innebandy Vill n.d. “.” Accessed 20 September 2022. https://innebandyvill.se/

- Smith, B., and K. R. McGannon. 2018. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (1): 101–121. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Spaaij, R., K. Farquharson, J. Magee, R. Jeanes, D. Lusher, and S. Gorman. 2014. “A Fair Game for All? How Community Sports Clubs in Australia Deal with Diversity.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 38 (4): 346–365. doi:10.1177/0193723513515888.

- Spaaij, R., A. Knoppers, and R. Jeanes. 2020. “We Want More Diversity but…’: Resisting Diversity in Recreational Sports Clubs.” Sport Management Review 23 (3): 363–373. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.007.

- Swedish Research Council 2017. Good Research Practice https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html

- Tervo, T., and A. Nordström. 2014. “Science of Floorball: A Systematic Review.” Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine 5: 249–255. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S60490.

- UN (United Nations). 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” Accessed 5 December 2022. http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- Wermke, W., G. Höstfält, K. Krauskopf, and L. Adams Lyngbäck. 2020. “A School for All’ in the Policy and Practice Nexus: Comparing ‘Doing Inclusion’in Different Contexts. Introduction to the Special Issue.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 6 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/20020317.2020.1743105.

- WHO (World Health Organization) 2001. “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.” Accessed 28 March 2023. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

- Wicker, P., and C. Breuer. 2014. “Exploring the Organizational Capacity and Organizational Problems of Disability Sport Clubs in Germany Using Matched Pairs Analysis.” Sport Management Review 17 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.03.005.