Abstract

Due to the challenges associated with measurement, studies attempting to evaluate the effects of mega and non-mega sports events from a broader, more comprehensive perspective are rare. This paper relies on Camagni’s concept of territorial capital, which is often used to evaluate policy actions in regional studies but represents a new concept in sport. The study investigates the option of employing this concept to evaluate international sports events. It is thus the first to involve the concept in the area of sports events and, indeed, in sport generally. After introducing the concept, its four traditional subdimensions are addressed (‘public goods and resources’, ‘private fixed capital stock’, ‘social capital’ and ‘human capital’) and implemented in aspects of sports events. We found that the content of Camagni’s model creates a potential base for a more wide-ranging methodology to assess the impacts and legacies of sports events.

Introduction

The globalisation of sport and the global spread of sporting events have been associated with the emergence of international sports events on most continents and in growing numbers (Borgers et al., Citation2013; Graeff and Knijnik Citation2021). Cities with various resources attract and host different types of sports events of various sizes and durations (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Polcsik and Perényi Citation2022). We have also seen a growing research interest in analysing the economic, social, environmental and cultural effects of these sports events over the past two decades (Taks, Chalip, and Green Citation2015; Thomson et al. Citation2019). These studies have highlighted various aspects and issues tied to staging sports events (Thomson et al. Citation2019) and found that characteristics such as event size influence research outcomes (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013).

Given the central role of the impact and legacy of sports events in bidding processes (Preuss Citation2019), it may be appropriate to discuss and debate existing methodologies and to spark a possible new round of debates by introducing a new concept to the sports event research community. By avoiding the overcomplication of the existing literature on the evaluation of sports events, we propose considering whether (1) a new concept can be introduced, (2) it is worthy of consideration in so far as it takes a different approach to measuring the assets of the candidate and/or host cities and/or countries, and (3) it can be used in future bidding procedures to predict the capacity of host cities and/or countries so as to realise potential impacts and legacies.

In this paper, we aim to consider the concept of territorial capital evaluating sports events by introducing Camagni’s (Citation2008) analytical scheme. The model may provide a new tool in the future to systematise impacts and legacies associated with sports events across a fairly broad spectrum with a particular focus on the capital elements involved.

Background

Sports events are diverse in nature, and their definition lacks uniformity (Horne Citation2015; Müller Citation2015; Taks, Chalip, and Green Citation2015). Generally, the literature distinguishes between two types of international sports event: mega sports events, such as the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup (Horne Citation2015), and non-mega sports events (Gibson, Kaplanidou, and Kang Citation2012; Taks Citation2013). In contrast to mega sport events, non-mega sports events (NMSEs) attract less media interest, require less significant investment, and have a more limited tourist appeal (Gratton, Dobson, and Shibli Citation2000; Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). However, both types of events have the potential to generate both positive and negative impacts for host communities (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Polcsik, Laczkó, and Perényi Citation2022; Taks Citation2013).

As regards large international sports events, Preuss (Citation2015) diversified impacts by differentiating short-term impacts from legacies, stating that the legacies of sports events are understood as (1) lasting, long-term changes and (2) structural changes which basically influence the hosting region’s future economic potential. A number of authors have emphasised that any effect created in connection with large sports events may fade away shortly after the events (Balduck, Maes, and Buelens Citation2011; Oshimi, Harada, and Fukuhara Citation2016); however, legacies last longer and vary for the different stakeholders (Preuss Citation2007; Scheu, Preuß, and Könecke Citation2021). Furthermore, Gratton and Preuss (Citation2008) have stated that the legacy of sports events can be described by using the tangible and intangible, short- and long-term, and planned and unplanned dichotomies. Tangible benefits—also referred to as ‘hard’ and quantifiable—include new or renovated infrastructure or superstructure improvements (Preuss Citation2007; Scheu, Preuß, and Könecke Citation2021; Thomson et al. Citation2019), while intangible outcomes—also thought of ‘soft’ and difficult to quantify (Mair et al. Citation2023; Preuss Citation2007; Thomson, Kennelly, and Toohey Citation2020)—include social capital (Gibson et al. Citation2014; Zhou and Kaplanidou Citation2018) and human capital (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021).

Several attempts have been made to conceptualise the measurement of the legacies of mega sports events (Kaplanidou Citation2012; Preuss Citation2007) and to create frameworks to evaluate them (Byers, Hayday, and Pappous Citation2020; Preuss Citation2015; Preuss Citation2019). Systematic literature reviews have also investigated legacy effects from different aspects (Scheu, Preuß, and Könecke Citation2021; Thomson et al. Citation2019). Thus, the issue has been widely studied, particularly in relation to mega events, with different measurement models having been developed; however, the challenges of measurement have also been raised.

Among the numerous aspects and approaches in the rich literature, Preuss’s (Citation2015, Citation2019) and Byers and colleagues’ (Citation2020) measurement models should be mentioned. These models have addressed the dimensions of legacy, sustainability or leveraging and have even attempted to take a complex, standardised approach and developed a measurement system (Preuss Citation2015; Preuss Citation2019). These past studies provide essential information on the legacy of sports events; however, most papers have examined a certain highlighted part of sports event impact and legacy or focused on a single chosen aspect (Preuss Citation2019). Limited studies focus on multiple legacy topics or take a more complex view, and the focus clearly remains on mega sports events only (Scheu, Preuß, and Könecke Citation2021; Thomson et al. Citation2019).

Byers, Hayday, and Pappous (Citation2020), however, took the issues connected to sports events a step forward with their interdisciplinary views. Also, Byers, Hayday, and Pappous (Citation2020) raised the issues of wicked problems and the complexity of understanding; among those, the legacies of sports events for the host municipality or region were also mentioned. Byers, Hayday, and Pappous (Citation2020) introduced a new aspect by conceptualising problems as wicked. However, a grouping of legacies that needed to be accounted for was not created. Therefore, this model also left operationalizability open. Undoubtedly, by distinguishing six domains to cover the structural changes generated by sports events, Preuss (Citation2019) created a framework that aimed to provide a basis for empirical research. However, being based on a kind of synthesis of already researched and fragmented legacies in the literature, the framework created a limitation. Furthermore, un- or underresearched but still relevant legacies could have been overlooked or handled marginally in addition to impacts that were not addressed. On the other hand, both frameworks (Byers, Hayday, and Pappous Citation2020; Preuss Citation2019) focus on the legacies of mega sports events, ignoring non-mega sports events.

It should be noted that the notion of ‘capital’ has previously been addressed in the literature on social processes in sport by Bourdieu and Richardson (Citation1986), Coleman (Citation1988, Citation1990) and Putnam (Citation1993). Social capital and human capital have also been covered in the context of sports event research (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Misener and Mason Citation2006; Zhou and Kaplanidou Citation2018). However, other manifestations of ‘capital’ have not been used or referred to in the context of sports events. Consequently, a concept for research that could focus on evaluating the effects of both mega and non-mega sports events with a focus on the host cities’ or even region’s ‘capital’ elements is missing from scholarly approaches to sport.

Due to the overall rich literature on sports events, it is necessary to review previous studies whose scope matches the capital items defined in the Camagni model. This paper is certainly not meant to be a reflection of all the sports event impact and legacy studies or a remake of previous review papers on this topic (Polcsik and Perényi Citation2022; Scheu, Preuß, and Könecke Citation2021; Thomson et al. Citation2019; Thomson, Kennelly, and Toohey Citation2020); rather, the studies used for the purposes of this paper aimed to demonstrate and acknowledge research relevant to the segments identified in the Camagni model as well as to explore possible gaps.

Methods

Our study therefore contextualises and situates previous findings within the broader interdisciplinary sports event literature and clarifies the complexity and interrelatedness of different components to strengthen the application of the Camagni model. We assume from regional studies that territorial capital, with its traditional four segments (within the dimensions of materiality and rivalry), could be a new conceptual approach in sport, which could summarise more areas affected by sports events in the local or regional economy and society. We propose that the territorial capital approach may assist in good governance procedures, as well as granting, planning and implementing processes tied to organisational decision-making at the local, regional and international levels, in addition to directions for future research studies as well.

Based on Gilson and Goldberg (Citation2015), this research can be seen as a conceptual study; it does not aim to present specific data. However, it does aim to provide a framework that can be used to conduct operationalizable empirical research. Our study bridges the gap between regional and sports studies, broadening the scope for analysing the impacts and legacies of sports events by adapting an existing model, not by creating a completely new one. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to address the concept of territorial capital in relation to sports events and attempts to see whether Camagni’s concept can contribute to the evaluation of engagement among local and regional stakeholders in staging mega and non-mega international sports events. It is also the first study to review the four traditional squares of the Camagni model by searching for relevance in the sports events literature and thus contributing a conceptual paper that considers ideas tied to the territorial capital approach, which are discussed next.

The concept of territorial capital

The regional approach to local development was first mentioned in 2001 (OECD Citation2001) with an introduction to the concept of territorial capital. Since then, in the context of regional policy, this concept has become a major area of interest in economics (Perucca Citation2014; Tóth Citation2015). The definition used by Van der Ploeg et al. (Citation2008, 13) best summarises the essential meaning of this notion: ‘the amount and intertwinement of different forms of capital (or different resources) entailed in, mobilized and actively used in (and reproduced by) the regional economy and society’. Differentiating components within the dimensions of rivalry (private to public goods) and materiality (tangible to intangible goods), the paper that introduced the Camagni model (Citation2008) has become one of the most cited studies in all the research involving territorial capital.

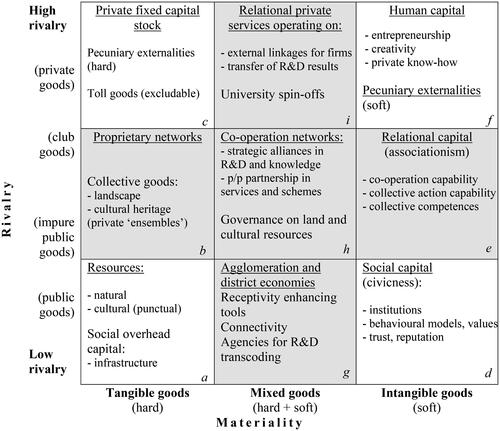

The model developed by Camagni (Citation2008) is a three-by-three matrix containing nine different areas, which is divided into traditional and innovative subdimensions. The traditional subdimension contains four squares, while the innovative one contains five. The four traditional dimensions are placed in the corners of the model and stand for economic, public, social and human capital, which fall along two axes for high-low rivalry and tangible-intangible goods (). In-between areas known as an ‘innovative cross’ represent the intermediate mixed contents on the boundaries of the four traditional factors (Benassi, D’Elia, and Petrei Citation2021). Tóth (Citation2015) has emphasised the integrative nature and benefit of this model in allowing parallel consideration of economic, social, human and environmental factors within one framework, while assigning equal importance to all its nine dimensions.

Figure 1. Camagni’s (Citation2008) concept of territorial capital with traditional (a, c, d and f) and mixed (b, e, g, h and i) elements.

Camagni (Citation2008) was the first to integrate the elements of territorial capital into a single model (Tóth Citation2015). The elements of territorial capital were separated by the rivalry and materiality dimensions. The four traditional segments of the Camagni model contain the tangible and the intangible spectrum ().

Many forms of the capital elements included in the Camagni model had already been investigated empirically in regional studies before the model was developed (Tóth Citation2015), and the model has also triggered a number of further studies (Jóna Citation2015; Tóth Citation2015). Its broad applicability is demonstrated by the fact that it is equally suited to comparing regional variations in a country or on a continent (Fratesi and Perucca Citation2019; Getzner and Moroz Citation2022; Jóna Citation2015; Perucca Citation2014) as it is to analysing the regional impact of an industry (Cerisola and Panzera Citation2022) or to showing the impact of a specific capital element on economic growth (Capello et al. Citation2011).

Public goods and resources

According to Camagni’s (Citation2008) taxonomy, this group includes public goods in a tangible form found in the territory involved. No one can be excluded from consuming them, and they simultaneously contribute to the economic appeal of the area. Typically, they include factors that are created through public funding and can be provided as a public service to economic actors in the area, as well as factors that are formed through natural phenomena and social development and can be used by anyone. Natural and cultural resources as well as infrastructure are only treated comprehensively as social overhead capital in the original taxonomy. Based on Tóth (Citation2015), regional research studies usually measure the capital elements described below.

The cultural capital approach is quite heterogeneous in the literature. As regards public goods, we consider the approaches used by Lash and Urry (Citation1994) and Matarasso (Citation1999) to be relevant in the present dimension in relation to their public characteristics. Matarasso (Citation1999) argues that cultural capital is an aspect of human capital embodied in cultural activities following long-term accumulation. Lash and Urry (Citation1994) define it as a commercial element of a social and historical heritage. Kitson, Martin, and Tyler (Citation2004) assessed it explicitly as the quantity and quality of cultural facilities and assets.

The two types of environmental and natural capital appear with similar content in different studies. Emery and Flora (Citation2006) concept of natural capital tend to approach the diversity of natural endowments in a given area, including weather, geographical isolation, natural resources, amenities and natural beauty. Agarwal, Rahman, and Errington (Citation2009) concept of environmental capital extends the previous definition to include sustainability. According to Agarwal, Rahman, and Errington (Citation2009, 311), ‘environmental capital consists of a number of factors which include natural resource endowment, peripherality and remoteness, the cost of environmental maintenance, and pollution and congestion’. Carayannis, Barth, and Campbell (Citation2012) likewise emphasise the coherence between sustainability and natural capital elements in the natural environment.

Infrastructural and built capital refers to the quantity and quality of community-built, community-owned infrastructure that supports social and economic activities (Emery and Flora Citation2006; Kitson, Martin, and Tyler Citation2004).

According to Brasili et al. (Citation2012, 29), ‘settlement capital provides a representation of the housing characteristics and the evolution of human presence in a territory, completing the full knowledge of the potentialities and criticalities of the territorial capital’. The public goods and resources segment of Camagni’s model is consistent with research on sports events. As these events are mostly financed by public resources and mostly held in public facilities, they are the primary focus of sports economics research.

Private fixed capital stock

In his key study, Camagni (Citation2008) defined private fixed capital stock as a territorial endowment and pecuniary externalities which are produced in local context and sold on the market. However, research on the private fixed capital element of Camagni’s model has used the term ‘financial capital’ (Emery and Flora Citation2006; Huggins and Izushi Citation2008) or ‘economic capital’ (Agarwal, Rahman, and Errington Citation2009). Emery and Flora (Citation2006, 21) applied Lorenz’s (Citation1999) definition, according to which ‘financial capital refers to the financial resources available to invest in community capacity-building, to underwrite the development of businesses, to support civic and social entrepreneurship, and to accumulate wealth for future community development’. Financial capital is related to other forms of capital, and it is indispensable in the growth and development of other forms of capital, such as social and human capital. A decline in financial capital tends to cause a simultaneous downward spiral in other forms of capital (Emery and Flora Citation2006; Huggins and Izushi Citation2008). In the case of economic capital, researchers generally use the following definition: ‘capital resources that are invested and mobilized in pursuit of profit’ (Lin Citation2001).

The results of empirical studies have demonstrated the importance of financial or economic capital. Economic and infrastructure capital promotes regional growth (Dodescu et al. Citation2018), capital investments have a substantial positive influence on gross regional product (GRP) per capita (Getzner and Moroz Citation2022), and the resilience of regions in mitigating economic shocks significantly correlates with the territorial assets available (Fratesi and Perucca Citation2019). Also, territorial capital positively influences the value and performance of companies, contributing significantly to their long-term rise and global recognition (Barzotto, Corò, and Volpe Citation2016). Further, while there may be large differences in the distribution of territorial assets between regions, these differences do not clearly reflect differences in GDP growth (Perucca Citation2014). Complementary links between territorial capital and regional policy may be the solution for regions at different levels of economic development (Fratesi and Perucca Citation2019).

As we have noted, researchers use an alternative concept for measuring capital within the private fixed capital stock element of Camagni’s model. Economic or financial capital plays an important role at the regional level, but there are many factors that influence the effective contribution of this element to the development of a region. Sports events can show patterns with similarities to those of other elements of territorial capital, which may also have a combined impact on local communities. Based on studies on the territorial capital in this dimension, we must also look for sports-related studies with a similar definition.

Social capital

Camagni (Citation2008, Citation2017) outlines the difficulty and complexity of defining and measuring social capital, while he reaches back to approaches used by Coleman (Citation1990) and Putnam (Citation1993) for conceptualisation. The problem of defining social capital lies not only in its complexity, but also in its pervasive nature; quantifying it is hindered by the indirect character by which it may foster local development (Camagni Citation2008).

The Camagni model (2008) refers to civicness in connection with institutions, behavioural models, values, trust and reputation and conceives of social capital as a ‘glue’ that increases the efficiency of other factors and thus influences the economic system as a whole. Camagni draws on ideas from Putman’s political science-oriented civicness approach, where the notions of bonding and bridging were first mooted. Camagni places a special emphasis on this in his model in pointing out that ‘regional and local governments must address the issue of the competitiveness and attractiveness of external firms’, strengthening the potential for full exploitation of business co-operation (Camagni Citation2017, 116).

The cause-effect approach is replaced by co-operation and synergy, while local competitiveness is embedded in intangible social values, such as local trust, sense of belonging, creativity, connectivity, rationality and local efficiency. The complexity of its intangible and public nature is highlighted in a two-dimensional model, which was developed along the formal-informal and macro-micro dichotomies (Camagni Citation2004). In Camagni’s (Citation2004) social capital matrix, institutions, rules and norms defined as formal macro level factors have the power of reducing transaction cost and raising guarantees for the delivery of agreements. Social networks, associations and interpersonal relations on the formal micro level lower the cost of information and its speed of transmission, while trust and reputation play a facilitative role at the informal micro level and foster co-operation and maintain or rebuild relations among partners (Camagni Citation2008). Finally, collective actions are facilitated by common values and behaviours in cost reduction and coordination at the informal macro level (Camagni Citation2008). All in all, the contribution of social capital in the form defined by Camagni (Citation2004) may contribute to showcasing the effective delivery of economic transactions.

Human capital

Human capital can be interpreted as a set of qualities that include education, skills, knowledge and personal experience (Luthans, Luthans, and Luthans Citation2004; Sweetland Citation1996). Investment is made in them deliberately to increase productivity and competitive advantage (Coleman Citation1988). In addition to encyclopaedic knowledge, human capital includes skills, competencies, and the customs and practices of society, which together boost the production of the region (Schultz Citation1982).

According to Camagni’s (Citation2008) taxonomy, human resources are of paramount importance to territorial capital, marketable knowledge that can be developed locally and is constantly being developed, and a network of contacts. Based on Sweetland (Citation1996), Taks (Citation2013, 131) stated that ‘human capital refers to skills that people possess’. Acquiring those skills may have a positive effect on performance, thus contributing to personal development and social welfare (Brannagan and Grix, Citation2023).

Human capital plays a leading role in economic processes, since it develops the local resources and attractiveness of a particular country/region/city (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013). Furthermore, it also acts as an effective factor in economic growth and the development of local communities (Becker Citation1964), while representing high added value for society (Becker Citation1996). Human capital can be described as knowledge development related to experiences, education, skills and ideas (Luthans, Luthans, and Luthans Citation2004), and its value also depends on the rate at which it can contribute to competitiveness (Lepak and Snell Citation1999).

Therefore, the capital type represented by individually acquired ability and knowledge is becoming increasingly important (Coleman Citation1990), and, as an invisible capital element, it can be turned into an economic resource (Bourdieu Citation2004). Human resources and high-level competencies among sports leaders also play a key role in planning and successfully implementing sports events (Brannagan and Grix Citation2023; Parent, Rouillard, and Leopkey Citation2011).

Territorial capital and sports events

Linking territorial capital theory with an analysis of the impacts and legacies of sports events could create synergy between regional and sports studies. An interdisciplinary approach can facilitate a better understanding of complex and wicked problems, such as the legacies of sports events in the host municipality or region (Byers, Hayday, and Pappous Citation2020).

As the frameworks developed by Byers, Hayday, and Pappous (Citation2020) and Preuss (Citation2019) have provided valuable contributions to the dilemma of evaluating sports events, their focus remains on the legacies of mega sports events only. They show no concern for impacts and are not engaged with non-mega sports events. Therefore, it may become desirable for the benefit of future researchers and policy makers to set up a framework that can achieve both the aggregation and operationalization of impacts and legacies of sports events of various sizes. This would allow for a comparison of the impacts and legacies of sports events on different scales, which could also provide a possible host municipality/region with guidance on the type of sports event it may be beneficial to bid for. A further argument in favour of a model that also allows the impacts and legacies of non-mega events to be taken into account is that local impacts and legacies are even more dominant in their case than for mega events, since they may be more frequent and/or repeated in a specific location, host settlement or region.

In order to put the debate on the possibility of applying the Camagni model to the field of sports event research context, as part of this conceptual paper, we must reflect on the previously conducted sports event literature that can be brought to relevance of the dimensions and elements addressed in the Camagni model. These sports event-related studies that, without conscious use of or reference to the Camagni model, have addressed some of the research directions presented in territorial capital concept should thus be identified and acknowledged.

In the following, as with other conceptual studies with a particular focus—in this case, on the possibility of applying Camagni’s territorial capital—previous sports event research is presented only to support the applicability of the model itself. Therefore, not all existing studies on sports events have been collected and reflected on; rather, only those were reviewed that addressed research directions along the context of the Camagni model’s four traditional segments (Citation2008).

Accordingly, with the four segments of the Camagni model in mind, the following discussion provides an overview of sports events as a potential positive and negative driver of urban, economic, environmental, social and human capital development. The aspects of events in the following categories are identified as ‘public goods and resources’, ‘private fixed capital stock’, ‘social capital’ and ‘human capital’.

At the same time, a presentation of the impacts and legacies can provide an opportunity to explore how the concept discussed in this study can be used to examine events in a new way and outline what new possibilities emerge to examine the specificities of the host country/city.

Public goods and resources

The development of infrastructural capital (sports facilities and general infrastructure) is often noted as one of the most important legacies of mega sports events (Preuss Citation2004, Citation2019).

A number of studies stress that after-event utilization of a specific sports infrastructure legacy must be planned at the bidding stage (Preuss Citation2015; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007). Otherwise, it can easily become a white elephant (Alm et al. Citation2016; Mangan Citation2008), which may require significant public resources to maintain lest it deteriorate (Maharaj Citation2015; Preuss Citation2007). Such future plans may include additional/upcoming sports and cultural events, exhibitions, fairs and conferences that the city wants to host in the newly built sports facilities (Clark and Kearns Citation2016; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007; Zawadzki Citation2022).

The development of sports infrastructure may offer long-term benefits if it provides new opportunities not only for sport, but also for recreational activity for local athletes after the event (Annear et al. Citation2022; Clark and Kearns Citation2015; Preuss Citation2019) and if the amount spent on it does not divert resources from grassroots sports (Mangan Citation2008). The establishment of sports parks connected to sports facilities may be justified for a similar reason (Preuss Citation2019; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007). A key issue is how the facilities and neighbourhoods that are affected will be able to integrate into the rest of the city after the event, a matter that requires careful consideration (Clark and Kearns Citation2016).

As regards the development of general infrastructure (roads, public transport, ICT networks etc.), a distinction must be made between candidate cities that are developing and developed (Alm et al. Citation2016; Davis Citation2020; Zawadzki Citation2022). While the former usually do not have the general infrastructure to meet the increased demands during the event, the latter may be able to draw on existing facilities. Therefore, the opportunity cost of investments may also be high for developing cities, as developments may be required in many other areas (Maharaj Citation2015; Zimbalist Citation2006). The literature also states that the capital costs of building new sports infrastructure (e.g. stadiums) are likely to be higher than renovating or expanding existing facilities (Zimbalist Citation2006).

In the case of cities in developing societies, the possibility of infrastructure development and its economic dynamism effects tend to be a strong argument in the bidding process, thus accelerating and bringing forward future investments (Földesi Citation2014). The existence of infrastructure in the required quality and quantity can be a significant competitive advantage in the bidding process, as demonstrated by the London 2012 bid (Davis Citation2020). General infrastructure developments can contribute to the long-term improvement of a host city’s ability to attract (foreign) working capital, e.g. through the formation of new firms (Clark and Kearns Citation2016) and in boosting tourism (Preuss Citation2019; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007). In order to expand tourism services and attract future tourists, it is necessary to establish museums and pedestrian zones as well. If they are not planned in a coordinated way, no breakthrough in tourism can be expected (see the example of the Lillehammer and Albertville Winter Olympics and the Barcelona summer games (Solberg and Preuss Citation2007; Terret Citation2008)).

One of the most common criticisms of infrastructure development is that, although sports events are motivated by the aim of reducing social inequalities among local actors, the gap between wealthy capitalists and deprived social groups actually increases further in many cases (Bergsgard et al. Citation2019; Pereira Citation2018; Vico, Uvinha, and Gustavo Citation2019). There is an additional typical risk that the main beneficiaries of public-funded projects are private equity investors (Clark and Kearns Citation2016).

As regards cultural capital, some authors have posited that facilities built for the long term remain living reminders in the life of the city, represent attractions for residents and tourists alike (Preuss Citation2015; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007) and thus become part of the local community’s memory (Allmers and Maennig Citation2008).

Negative environmental impacts include increased pressures on the natural environment (particularly in the case of outdoor sports events), soil erosion, environmental pollution, and negative impacts on flora and fauna (mainly in the case of facility developments) (Duan et al. Citation2021; Mackellar Citation2013), which all affect the environmental capital of the host region. Significant additional air, noise and light pollution can occur, especially during events (Silva and Ricketts Citation2016). These externalities are exacerbated by sports tourists, athletes and delegates travelling to remote locations for the event (Davenport and Davenport Citation2006), thus resulting in increased traffic and decreased parking and antisocial behaviour among people in the local community (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Polcsik and Perényi Citation2022; Polcsik, Laczkó, and Perényi Citation2022). According to Collins, Jones, and Munday (Citation2009), however, it remains difficult to judge whether a suggested negative effect could be considered as a direct and clearly distinct externality of a sports event. Specifically, the mere organisation of motorsport competitions also promotes the use of vehicles powered by non-renewable resources instead of cycling or walking, thus potentially producing indirect, long-term negative effects (Duan et al. Citation2021; Konstantaki and Wickens Citation2010).

At the same time, a sports event can draw the attention of decision-makers to the fact that by recultivating the natural environment, natural attractions can also contribute to the appeal of the destination in addition to the built environment (Preuss Citation2019). In this context, mega sports events should be prepared and organised with regard to sustainability. Ex-ante environmental impact assessments should be made, e.g. a carbon footprint analysis (Collins et al. Citation2007) or environmental input-output modelling (Jones Citation2008).

One of the most important consequences of settlement capital is that villages built to accommodate participants at mega sports events usually help to expand housing opportunities for the local population, thus potentially promoting gentrification and recultivation of neighbourhoods (Preuss Citation2015; Solberg and Preuss Citation2007). A negative accompanying phenomenon is the significant increase in property prices and rents (Konstantaki and Wickens Citation2010; Vico, Uvinha, and Gustavo Citation2019). This is not always viewed positively by local residents, as the resulting rise in property values may see them priced out of their homes (Gunter Citation2014). Non-mega sports events can benefit the local community through infrastructure upgrades but not through newly built sports infrastructure (Gibson, Kaplanidou, and Kang Citation2012; Taks Citation2013).

As we consider the capital elements and review the economic literature on sports events, several points of connection can be observed that draw attention to the role of such events both in the accumulation of built and infrastructural public goods and cultural goods and in the depletion and erosion of natural resources.

Private fixed capital stock

Papers published on the economic impact of sports events are diverse in terms of methodology, delimitation and results (Kasimati Citation2003; Saayman and Saayman Citation2014). In addition to the scholarly aspect, this topic is also very important politically (Manzenreiter Citation2008; Porter and Fletcher Citation2008; Preuss Citation2007; Terret Citation2008). In economic impact studies, the clustering of sports events plays an important role by comparing effects based on an event’s frequency, size, ownership or economic significance (Barget and Gouguet Citation2007; Gratton, Dobson, and Shibli Citation2000; Saayman and Saayman Citation2014). The methodology used, such as cost-benefit (Agha and Taks Citation2015; Gratton, Dobson, and Shibli Citation2000) or macroeconomic impact analysis (Despiney and Karpa Citation2014), could be another possible grouping criterion. However, there is a wide range of corresponding methods with respect to the definition of the research area; this makes results arrived at with the same method impossible to compare. Consequently, articles on regional economic development are presented from the perspective of the size of the sports event.

Major or mega sports events dominate the sports economics and management research literature. In addition to a political justification, as noted above, such events have the biggest interest in society, presumably due to their significantly greater impact. The spectrum of the sports events analysed is broad: from the FIFA World Cup (Manzenreiter Citation2008) through the UEFA European Championship (Despiney and Karpa Citation2014; Polcsik, Laczkó, and Perényi Citation2022) to the Olympic Games (Kasimati Citation2003; Porter and Fletcher Citation2008; Preuss Citation2004; Terret Citation2008). The conclusion is broadly common in the articles: major sports events do not have an unequivocal economic benefit, so justifying the economic impact of such events is rather challenging (Gibson, Kaplanidou, and Kang Citation2012). As Preuss (Citation2004) stated in relation to ‘the economic Olympic legacy’, tangible economic impacts diminish after a short period, with only structural changes remaining. One of the most important reasons for the lack of a regional economic impact is that habitual sponsors and companies benefit from ‘big events’, while local smaller enterprises have limited opportunities to exploit their potential (Kristiansen, Strittmatter, and Skirstad Citation2016). Nevertheless, there are other examples where regional micro and small businesses have been involved in planning and delivery (Kirby, Duignan, and McGillivray Citation2018). Small-scale events are also favoured by sports economists; simple access to data and straightforward explanations may explain their popularity (Gibson, Kaplanidou, and Kang Citation2012; Taks Citation2013). The results of research studies on small-scale sports events show that, in contrast to major events, they have the potential to generate direct economic benefit for their host communities (Kristiansen, Strittmatter, and Skirstad Citation2016; Wilson Citation2006).

Economic assessments of mega sports events face the problem of defining economic impact. They either do not consider the externalities that emerge as a result of the event or only capture the positive ones (Barget and Gouguet Citation2007; Porter and Fletcher Citation2008). Nevertheless, following the concept of territorial capital, the externalities should be investigated in the other parts of Camagni’s model.

Based on papers on the economic impact of sports events, it is clearly possible to use Camagni’s private fixed capital stock with regard to these events. Previous literature has demonstrated that small and mid-sized sports events may demonstrate more economic effects (Kristiansen, Strittmatter, and Skirstad Citation2016; Wilson Citation2006). In accordance with regional economic assessment studies, economic or financial impact could be used as a baseline concept instead of private fixed capital stock.

Social capital

With regard to sports events, social impact and legacy studies more commonly address issues associated with different types and sizes of events (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Polcsik and Perényi Citation2022) in different economic and cultural contexts (e.g. Balduck, Maes, and Buelens Citation2011; Oshimi, Harada, and Fukuhara Citation2016; Vico, Uvinha, and Gustavo Citation2019).

However, as Preuss (Citation2007) has observed, social capital is generated by a challenging process of transforming short-term social impacts into long-term legacies. In addition to the immediate response of pride, community or the maintenance of identity, it is also referred to as psychic income (Gibson et al. Citation2014; Kim and Walker Citation2012) and is transferred to social initiatives and long-lasting community benefits. Thus, as stated by Chalip (Citation2006), being realised as social capital requires additional efforts. It is also theorised/posited that sports events are halfway between entertainment as a service and social capital as a long-term benefit (Chalip Citation2006); the theoretical definitions and measures of social capital do not always correspond.

As social capital is specific to a social environment, it displays diversity across nations. Countries representing developing or transitioning economies, such as former socialist countries and developing societies in South America, have aimed to stimulate their economies (Földesi Citation2014; Gibson et al. Citation2014). By entering the arena of bidding procedures for and hosting sports events, they attempt to generate international attention for their countries, promote their cultures, create trust and creditability, and attract investors (Graeff and Knijnik Citation2021).

Sport is assumed to have the power to build a collective identity and patriotism (Dóczi Citation2012; Heere et al. Citation2013) and to create social capital through events as well (Chalip Citation2006; Gibson et al. Citation2014; Misener and Mason Citation2006; Zhou and Kaplanidou Citation2018). Some authors are more critical of the ability of sports events to foster sports participation (Annear et al. Citation2022; Chalip et al. Citation2017).

Authors focus attention on the perceptions of those living in host cities and state that the measurement and understanding of the perceived social effects of sports events are essential in the overall success of such events for local communities (Gursoy, Milito, and Nunkoo Citation2017; Polcsik, Laczkó, and Perényi Citation2022). Gursoy and Kendall (Citation2006) point out that personal involvement among local citizens in planning or delivering events is indispensable to realising social capital. For example, the direct role of volunteerism in event support creates a collective experience and may contribute to long-term social capital (Taks Citation2013). We see multiple roles in volunteer activities at small-scale events, resulting in higher potential for personal growth (Taks, Chalip, and Green Citation2015); some authors write about social innovation in connection with how activities are offered by sports organisations (Corthouts et al. Citation2020). According to residents’ perceptions, mega events may activate social cohesion ties within a community (Gursoy, Milito, and Nunkoo Citation2017; Polcsik and Perényi Citation2022).

Human capital

The short period of sports events poses unique challenges for the organisers to recruit, train, socialise and retain employees and volunteers (Xing and Chalip Citation2012). As a dividend of organising sports events, human capital can be identified as an intangible impact/legacy (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013). According to Barros and Alves (Citation2003), establishing network ties is a source of value growth; in contrast, Taks (Citation2013) sees growing potential in community interactions during sports events. Human capital is a crucial source of competitive advantage (Luthans, Luthans, and Luthans Citation2004). Nevertheless, its preservation vis-à-vis sports events with a limited duration is a challenge; therefore, strategic planning is essential so that the host country or region can derive a competitive advantage (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). Accurately measuring the extent of intangible legacies like human capital is challenging (Preuss Citation2015). Relatively little empirical research has been carried out on the correlation between human capital and the effects of sports events, with a number of authors confirming the difficulty of such an analysis (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013). From this point of view, smaller sports events are better served by drawing on the expertise and knowledge of local communities. For instance, when involving a voluntary workforce, local people are the most suited to carrying out tasks related to the event, thus maximizing the impact of the local community’s human capital (Taks Citation2013).

The personnel involved in mega sports events occupy various functional roles and have different professional backgrounds, thus potentially resulting in diverse knowledge production. The effect of the newly acquired knowledge and skills may therefore vary from individual to individual (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). In the context of mega sports events, Zhuang and Girginov (Citation2012) analysed volunteers’ Olympic human capital, while Kaplanidou et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated the opportunities and results of exploiting human resources and examined the dimensions of human resources among Olympic organising committee employees, which include network ties, teamwork, interpersonal skills, adaptability and flexibility (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). They showed how these employees applied their newly-acquired knowledge and skills during their subsequent career development. These skills can be used in environments which require coordination and quick decision-making. Thus, as a result of the Olympic legacy, human capital can be transferred to other fields so employees’ future career prospects can be enhanced (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). The study also pointed to the extent of losses of human capital in the host country by highlighting the limited opportunities to apply the use of acquired knowledge following an event (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021). Citing research carried out among the local inhabitants of the host country, Balduck, Maes, and Buelens (Citation2011) and Oshimi et al. (Citation2016) supplemented questionnaires on perceived social effects related to human capital (Sweetland Citation1996; Taks Citation2013). From the perspective of the host country’s/city’s residents, knowledge development is one of the most critical intangible legacies that sports events leave behind (Chalip et al. Citation2017; Kaplanidou Citation2012; Preuss Citation2019; Taks Citation2013). In summary, both mega and non-mega sports events offer a chance to develop human capital (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013), especially when the workforce is selected from among the local inhabitants of the host country (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2016).

Conclusion

Territorial capital is a well-known area of research in regional studies. One of the most frequently cited models was developed by the pioneer Camagni (Citation2008), who grouped the different elements of capital into a single model. The model emphasises regional specifications tied to cultural, economic and environmental contexts and offers ‘tailor-made’ sports implementation strategies for the pervasive leveraging of benefits potentially offered by such events. In this article, we briefly reviewed the Camagni model and its traditional four dimensions used in regional studies, in which the basis for distinguishing the capital elements was Camagni’s interpretation of the territorial capital model. These nominal definitions can be used to frame the effects of sports events and provide transparency for the reader about which parts of the capital elements were in the focus and what results were found in relation to these events. In this approach, the set and composition of the various capital elements can also be interpreted as the set of skills and capabilities needed to organise a mega or non-mega sports event. At the same time, the direction and extent of changes in these skills and capabilities can be investigated and analysed in both the short and long term after a sports event is over. The possibility of examining both short- and long-term capital elements simultaneously draws attention to the fact that the model can be used in measuring not only legacies, but also impacts.

Economic impacts and social and environmental aspects have been addressed, and have been considered increasingly important over the last two decades (Mair et al. Citation2023; Thomson et al. Citation2020; Wallstam et al. Citation2020). As sports events can have a wide range of impacts (e.g. in terms of the economy, tourism, society and participation in sport), the value of this study has been to present the impacts and legacies noted here grouped according to the capital elements in Camagni’s model. In the context of sports events, the application of Camagni’s model can be explained by the fact that the models developed by Byers et al. (Citation2020) and Preuss (Citation2019) do not include specifics on operationalizability. While Preuss (Citation2019) certainly suggests criteria, he does not mention specific indicators. However, the Camagni (Citation2008) model has been used for operationalization in a number of cases in regional studies (Cerisola & Panzera Citation2022; Fratesi & Perucca Citation2019; Getzner & Moroz Citation2022) and in areas other than sports.

Based on papers on the economic impact of sports events, it is possible to use Camagni’s private fixed capital stock for such events. Previous literature has shown that small and mid-sized sports events may demonstrate more economic effects (Kristiansen et al. Citation2016; Wilson, Citation2006). In accordance with regional economic assessment studies, economic or financial impact could be used as a baseline concept instead of private fixed capital stock. Although authors have raised concerns about a definition of economic impact that excludes externalities tied to sports events or considers them with a positive bias (Barget & Gouguet Citation2007; Porter & Fletcher Citation2008), results show that externalities may be viewed more objectively through the lens of Camagni’s model.

Considering the capital elements and reviewing the economics literature on sports events, several points of connection can be observed that draw attention to the role of these events in the accumulation of infrastructural public goods and cultural goods and the depletion and erosion of natural resources. Settlement capital, for example, which refers to villages built to accommodate participants at mega sports events, may expand housing opportunities for the local population, thus promoting gentrification and recultivation of neighbourhoods (Preuss Citation2015; Solberg & Preuss Citation2007). However, a concern about increased property prices and rents has also been raised (Konstantaki & Wickens Citation2010; Vico et al. Citation2019), with higher property values potentially pricing local residents out of owning homes (Gunter Citation2014). Infrastructure upgrades, excluding newly built sports infrastructure, that have been generated by non-mega sports events can be perceived as benefitting local communities (Gibson et al. Citation2012; Taks Citation2013).

The model investigated here favours a synthetic, even equal consideration of the social impacts of sports events on the lives of those living in host cities in addition to economic and other aspects, including public spending. Gursoy et al. (Citation2017) outlined the importance of a clearer understanding of impacts on local communities; the concept of territorial capital may thus be one possible approach to allow for an analysis with a wider spectrum. For example, knowledge development (Chalip et al. Citation2017; Kaplanidou Citation2012; Preuss Citation2019; Taks Citation2013) or collective experiences through volunteer involvement (Taks Citation2013) can also be considered and evaluated, even capitalised on with regard to local or regional characteristics—in addition to potential for personal growth (Taks et al. Citation2015), development of human capital (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2021; Taks Citation2013) and local workforce engagement (Kaplanidou et al. Citation2016) as hard-to-track intangible legacies.

The use of Camagni’s model takes a new approach when measuring the impacts of sports events at a local, regional or even national level and aims to stimulate debate among researchers and encourage consideration of using a new, alternative approach in sport adopted from regional studies. By acknowledging that a number of studies have been conducted on sports events with regard to the content defined in each type of capital in Camagni’s model to contribute to—and not to overcomplicate—an already crowded research area on events, it may be concluded that Camagni’s model could be used in the evaluation and prediction of effects associated with these events. This may facilitate a better understanding and (more) effective leverage of international sports events in future host environments regardless of the type of sport, the scope of the event or the geographical environment for hosting such events.

A future research direction may also be identified through this conceptual paper with an analysis of studies on the remaining five squares in the innovative cross of the Camagni model, which have not been targeted in this analysis. Furthermore, research done on the territorial capital matrix may allow us to identify as many relevant indicators as possible, which could enable us to operationalize specific variables for a complex evaluation of any sports event in the future. Thus, the application of the extended model will benefit from the existing literature, as it is already widely researched and well-established in regional studies. Empirical studies that have built on territorial capital in that field could also serve as a model for operationalizability and measurability in the context of sports events in the future. A possible analysis of bidding cities and regions (and local perceptions) which adapts territorial capital to sport may show the special characteristics of potential host cities and may reinforce the long-term benefit gained by holding a sports event or anticipate a possible failure to capitalise on otherwise available engines that can be put in place in connection with organising sport.

Limitations and final remarks

Based on the literature in the customary four segments of territorial capital apart from sports, the segment indicators demonstrated by Camagni are rich and diverse and may provide a useful foundation for sport-specific analysis. However, it should also be pointed out that the meanings of Camagni’s dimensions may not always match those used in the sports literature. A search for different keywords in sports was therefore necessary.

It should likewise be noted that while Camagni’s model has some potential for developing a new methodological perspective with certain possible new measurement elements to evaluate the impact of sports events, the limitations of the model should also be further explored within the sport subsystem. Other models which might achieve similar outcomes should be considered. For instance, the work of Davies et al. (Citation2019) on the application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) model should prove illuminating. All in all, the concept of territorial capital may serve as a new strategy path for future research with respect to the four capital elements, but also within the dimension of the five remaining squares in the innovative cross of the model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agarwal, S., S. Rahman, and A. Errington. 2009. “Measuring the Determinants of Relative Economic Performance of Rural Areas.” Journal of Rural Studies 25 (3): 309–321.

- Agha, N., and M. Taks. 2015. “A Theoretical Comparison of the Economic Impact of Large and Small Events.” International Journal of Sport Finance 10 (3): 199–216.

- Allmers, S., and W. Maennig. 2008. “South Africa 2010: Economic Scope and Limits.” Hamburg Contemporary Economic Discussions 21: 1–33.

- Alm, J., H. A. Solberg, R. K. Storm, and T. G. Jakobsen. 2016. “Hosting Major Sports Events: The Challenge of Taming White Elephants.” Leisure Studies 35 (5): 564–582.

- Annear, M., S. Sato, T. Kidokoro, and Y. Shimizu. 2022. “Can International Sports Mega Events Be Considered Physical Activity Interventions? A Systematic Review and Quality Assessment of Large-Scale Population Studies.” Sport in Society 25 (4): 712–729.

- Balduck, A. L., M. Maes, and M. Buelens. 2011. “The Social Impact of the Tour de France: Comparisons of Residents’ Pre-and Post-Event Perceptions.” European Sport Management Quarterly 11 (2): 91–113.

- Barget, E., and J. J. Gouguet. 2007. “The Total Economic Value of Sporting Events Theory and Practice.” Journal of Sports Economics 8 (2): 165–182.

- Barros, C. P., and F. M. P. Alves. 2003. “Human Capital Theory and Social Capital Theory on Sports Management.” International Advances in Economic Research 9 (3): 218–226.

- Barzotto, M., G. Corò, and M. Volpe. 2016. “Territorial Capital as a Company Intangible: Exploratory Evidence from Ten Italian Multinational Corporations.” Journal of Intellectual Capital 17 (1): 148–167.

- Becker, G. 1964. Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis of Special Reference to Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Becker, G. S. 1996. The Economic Way of Looking at Behavior: The Nobel Lecture (No. 69). Palo Alto, CA: Hoover Press.

- Benassi, F., M. D’Elia, and F. Petrei. 2021. “The ‘Meso’ Dimension of Territorial Capital: Evidence from Italy.” Regional Science Policy & Practice 13 (1): 159–175.

- Bergsgard, N. A., K. Borodulin, J. Fahlen, J. Høyer-Kruse, and E. B. Iversen. 2019. “National Structures for Building and Managing Sport Facilities: A Comparative Analysis of the Nordic Countries.” Sport in Society 22 (4): 525–539.

- Borgers, J., B. Vanreusel, and J. Scheerder. 2013. “The Diffusion of World Sports Events between 1891 AND 2010: A Study on Globalisation.” European Journal for Sport and Society 10 (2): 101–119. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2013.11687914.

- Bourdieu, P. 2004. Science of Science and Reflexivity. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, P., and J. G. Richardson. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241–258.

- Brannagan, P. M., and J. Grix. 2023. “Nation-State Strategies for Human Capital Development: The Case of Sports Mega-Events in Qatar.” Third World Quarterly 44 (8): 1807–1824. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2023.2200159.

- Brasili, C., A. Saguatti, F. Benni, A. Marchese, and D. Gandolfo. 2012. “The Impact of the Economic Crisis on the Territorial Capital of Italian Regions.” In ERSA Conference Papers. European Regional Science Association: Bratislava, Slovakia.

- Byers, T., E. Hayday, and A. S. Pappous. 2020. “A New Conceptualization of Mega Sports Event Legacy Delivery: Wicked Problems and Critical Realist Solution.” Sport Management Review 23 (2): 171–182.

- Camagni, R. 2004. “Uncertainty, Social Capital and Community Governance: The City as a Milieu.” Contributions to Economic Analysis 266: 121–149.

- Camagni, R. 2017. “Regional Competitiveness: Towards a Concept of Territorial Capital.” In Seminal Studies in Regional and Urban Economics, pp. 115–131. Cham: Springer.

- Camagni, R. 2008. “Regional Competitiveness: Towards a Concept of Territorial Capital.” In Modelling Regional Scenarios for the Enlarged Europe. European Competitiveness and Global Strategies, 33–46, edited by R. Capello, R. Camagni, B. Chizzolini, and U. Fratesi. Berlin: Springer.

- Capello, R., A. Caragliu, and P. Nijkamp. 2011. “Territorial Capital and Regional Growth: Increasing Returns in Cognitive Knowledge Use.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 102 (4): 385–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2010.00613.x.

- Carayannis, E. G., T. D. Barth, and D. F. Campbell. 2012. “The Quintuple Helix Innovation Model: Global Warming as a Challenge and Driver for Innovation.” Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 1 (1): 1–12.

- Cerisola, S., and E. Panzera. 2022. “Cultural Cities, Urban Economic Growth, and Regional Development: The Role of Creativity and Cosmopolitan Identity.” Papers in Regional Science 101 (2): 285–302.

- Chalip, L. 2006. “Towards Social Leverage of Sport Events.” Journal of Sport & Tourism 11 (2): 109–127.

- Chalip, L., B. C. Green, M. Taks, and L. Misener. 2017. “Creating Sport Participation from Sport Events: Making It Happen.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 9 (2): 257–276.

- Clark, J., and A. Kearns. 2015. “Pathways to a Physical Activity Legacy: Assessing the Regeneration Potential of Multi-Sport Events Using a Prospective Approach.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 30 (8): 888–909.

- Clark, J., and A. Kearns. 2016. “Going for Gold: A Prospective Assessment of the Economic Impacts of the Commonwealth Games 2014 on the East End of Glasgow.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 34 (8): 1474–1500.

- Coleman, J. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Coleman, J. S. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120.

- Collins, A., A. Flynn, M. Munday, and A. Roberts. 2007. “Assessing the Environmental Consequences of Major Sporting Events: The 2003/04 FA Cup Final.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 457–476.

- Collins, A., C. Jones, and M. Munday. 2009. “Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Mega Sporting Events: Two Options?” Tourism Management 30 (6): 828–837.

- Corthouts, J., E. Thibaut, C. Breuer, S. Feiler, M. James, R. Llopis-Goig, S. Perényi, and J. Scheerder. 2020. “Social Inclusion in Sports Clubs across Europe: Determinants of Social Innovation.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 33 (1): 21–51.

- Davenport, J., and J. L. Davenport. 2006. “The Impact of Tourism and Personal Leisure Transport on Coastal Environments: A Review.” Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 67 (1–2): 280–292.

- Davies, L. E., P. Taylor, G. Ramchandani, and E. Christy. 2019. “Social Return on Investment (SROI) in Sport: A Model for Measuring the Value of Participation in England.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 11 (4): 585–605.

- Davis, J. 2020. “Avoiding White Elephants? The Planning and Design of London’s 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Venues, 2002–2018.” Planning Perspectives 35 (5): 827–848.

- Despiney, B., and W. Karpa. 2014. “Estimating Economic Regional Effects of Euro 2012: Ex-Ante and Ex-Post Approach.” Management and Business Administration. Central Europe 22 (1): 3–15.

- Dóczi, T. 2012. “Gold Fever (?): Sport and National Identity–the Hungarian Case.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 47 (2): 165–182.

- Dodescu, A.-O., E.-A. Botezat, A. Costangioara, and M.-I. Bolos. 2018. “An Exploratory Analysis of the Territorial Capital and Economic Growth: Evidence from Romania.” Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research 52 (4): 95–112.

- Duan, Y., B. Mastromartino, J. Nauright, J. J. Zhang, and B. Liu. 2021. “How Do Perceptions of Non-Mega Sport Events Impact Quality of Life and Support for the Event among Local Residents?” Sport in Society 24 (10): 1742–1762.

- Emery, M., and C. Flora. 2006. “Spiraling-up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework.” Community Development 37 (1): 19–35.

- Földesi, G. S. 2014. “The Impact of the Global Economic Crisis on Sport.” Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research 63 (1): 22–30.

- Fratesi, U., and G. Perucca. 2019. “EU Regional Development Policy and Territorial Capital: A Systemic Approach.” Papers in Regional Science 98 (1): 265–281.

- Getzner, M., and S. Moroz. 2022. “The Economic Development of Regions in Ukraine: With Tests on the Territorial Capital Approach.” Empirica 49 (1): 225–251.

- Gibson, H. J., K. Kaplanidou, and S. J. Kang. 2012. “Small-Scale Event Sport Tourism: A Case Study in Sustainable Tourism.” Sport Management Review 15 (2): 160–170.

- Gibson, H. J., M. Walker, B. Thapa, K. Kaplanidou, S. Geldenhuys, and W. Coetzee. 2014. “Psychic Income and Social Capital among Host Nation Residents: A Pre–post Analysis of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.” Tourism Management 44: 113–122.

- Gilson, L. L., and C. B. Goldberg. 2015. “Editors’ Comment: So, What is a Conceptual Paper?” Group & Organization Management 40 (2): 127–130.

- Graeff, B., and J. Knijnik. 2021. “If Things Go South: The Renewed Policy of Sport Mega Events Allocation and Its Implications for Future Research.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 56 (8): 1243–1260.

- Gratton, C., N. Dobson, and S. Shibli. 2000. “The Economic Importance of Major Sports Events: A Case-Study of Six Events.” Managing Leisure 5 (1): 17–28.

- Gratton, C., and H. Preuss. 2008. “Maximizing Olympic Impacts by Building up Legacies.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 25 (14): 1922–1938.

- Gunter, A. 2014. “Mega Events as a Pretext for Infrastructural Develpoment: The Case of the All African Games Athletes Village, Alexandra, Johannesburg.” Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 23 (23): 39–52.

- Gursoy, D., and K. W. Kendall. 2006. “Hosting Mega Events: Modeling Locals’ Support.” Annals of Tourism Research 33 (3): 603–623.

- Gursoy, D., M. C. Milito, and R. Nunkoo. 2017. “Residents’ Support for a Mega-Event: The Case of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Natal, Brazil.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 6 (4): 344–352.

- Heere, B., M. Walker, H. Gibson, B. Thapa, S. Geldenhuys, and W. Coetzee. 2013. “The Power of Sport to Unite a Nation: The Social Value of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.” European Sport Management Quarterly 13 (4): 450–471.

- Horne, J. 2015. “Assessing the Sociology of Sport: On Sports Mega-Events and Capitalist Modernity.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 50 (4–5): 466–471.

- Huggins, R., and H. Izushi. 2008. “Benchmarking the Knowledge Competitiveness of the Globe’s High-Performing Regions: A Review of the World Knowledge Competitiveness Index.” Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 18 (1/2): 70–86.

- Jóna, G. 2015. “New Trajectories of the Hungarian Regional Development: Balanced and Rush Growth of Territorial Capital.” Regional Statistics 5 (1): 121–136.

- Jones, C. 2008. “Assessing the Impact of a Major Sporting Event: The Role of Environmental Accounting.” Tourism Economics 14 (2): 343–360.

- Kaplanidou, K. 2012. “The Importance of Legacy Outcomes for Olympic Games Four Summer Host Cities Residents’ Quality of Life: 1996–2008.” European Sport Management Quarterly 12 (4): 397–433.

- Kaplanidou, K. K., A. Al Emadi, M. Sagas, A. Diop, and G. Fritz. 2016. “Business Legacy Planning for Mega Events: The Case of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.” Journal of Business Research 69 (10): 4103–4111.

- Kaplanidou, K., C. Giannoulakis, M. Odio, and L. Chalip. 2021. “Types of Human Capital as a Legacy from Olympic Games Hosting.” Journal of Global Sport Management 6 (3): 314–332.

- Kasimati, E. 2003. “Economic Aspects and the Summer Olympics: A Review of Related Research.” International Journal of Tourism Research 5 (6): 433–444.

- Kim, W., and M. Walker. 2012. “Measuring the Social Impacts Associated with Super Bowl XLIII: Preliminary Development of a Psychic Income Scale.” Sport Management Review 15 (1): 91–108.

- Kirby, S. I., M. B. Duignan, and D. McGillivray. 2018. “Mega-Sport Events, Micro and Small Business Leveraging: Introducing the ‘MSE–MSB Leverage Model’.” Event Management 22 (6): 917–931.

- Kitson, M., R. Martin, and P. Tyler. 2004. “Regional Competitiveness: An Elusive yet Key Concept?” Regional Studies 38 (9): 991–999.

- Konstantaki, M., and E. Wickens. 2010. “Residents’ Perceptions of Environmental and Security Issues at the 2012 London Olympic Games.” Journal of Sport & Tourism 15 (4): 337–357.

- Kristiansen, E., A. M. Strittmatter, and B. Skirstad. 2016. “Stakeholders, Challenges and Issues at a co-Hosted Youth Olympic Event: Lessons Learned from the European Youth Olympic Festival in 2015.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 33 (10): 1152–1168.

- Lash, S., and J. Urry. 1994. Economies of Signs and Space (Theory, Culture & Society). London: Sage Publications.

- Lepak, D. P., and S. A. Snell. 1999. “The Human Resource Architecture: Toward a Theory of Human Capital Allocation and Development.” The Academy of Management Review 24 (1): 31–48.

- Lin, N. 2001. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action (Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511815447.

- Lorenz, E. 1999. “Trust, Contract and Economic Cooperation.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 23 (3): 301–315.

- Luthans, F., K. W. Luthans, and B. C. Luthans. 2004. “Positive Psychological Capital: Beyond Human and Social Capital.” Business Horizons 47 (1): 45–50.

- Mackellar, J. 2013. “World Rally Championship 2009: Assessing the Community Impacts on a Rural Town in Australia.” Sport in Society 16 (9): 1149–1163.

- Maharaj, B. 2015. “The Turn of the South? Social and Economic Impacts of Mega-Events in India, Brazil and South Africa.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 30 (8): 983–999.

- Mair, J., P. M. Chien, S. J. Kelly, and S. Derrington. 2023. “Social Impacts of Mega-Events: A Systematic Narrative Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 31 (2): 538–560.

- Mangan, J. A. 2008. “Prologue: Guarantees of Global Goodwill: Post-Olympic Legacies–Too Many Limping White Elephants?” The International Journal of the History of Sport 25 (14): 1869–1883.

- Manzenreiter, W. 2008. “The ‘Benefits’ of Hosting: Japanese Experiences from the 2002 Football World Cup.” Asian Business & Management 7 (2): 201–224.

- Matarasso, F. 1999. Towards a Local Culture Index. Measuring the Cultural Vitality of Communities. Gloucester: Comedia.

- Misener, L., and D. S. Mason. 2006. “Creating Community Networks: Can Sporting Events Offer Meaningful Sources of Social Capital?” Managing Leisure 11 (1): 39–56.

- Müller, M. 2015. “What Makes an Event a Mega-Event? Definitions and Sizes.” Leisure Studies 34 (6): 627–642.

- OECD. 2001. Territorial Outlook. Paris: OECD.

- Oshimi, D., M. Harada, and T. Fukuhara. 2016. “Residents’ Perceptions on the Social Impacts of an International Sport Event: Applying Panel Data Design and a Moderating Variable.” Journal of Convention & Event Tourism 17 (4): 294–317.

- Parent, M. M., C. Rouillard, and B. Leopkey. 2011. “Issues and Strategies Pertaining to the Canadian Governments’ Coordination Efforts in Relation to the 2010 Olympic Games.” European Sport Management Quarterly 11 (4): 337–369.

- Pereira, R. H. M. 2018. “Transport Legacy of Mega-Events and the Redistribution of Accessibility to Urban Destinations.” Cities 81: 45–60.

- Perucca, G. 2014. “The Role of Territorial Capital in Local Economic Growth: Evidence from Italy.” European Planning Studies 22 (3): 537–562.

- Polcsik, B., T. Laczkó, and S. Perényi. 2022. “Euro 2020 Held During the COVID-19 Period: Budapest Residents’ Perceptions.” Sustainability 14 (18): 11601.

- Polcsik, B., and S. Perényi. 2022. “Residents’ Perceptions of Sporting Events: A Review of the Literature.” Sport in Society 25 (4): 748–767.

- Porter, P. K., and D. Fletcher. 2008. “The Economic Impact of the Olympic Games: Ex Ante Predictions and Ex Poste Reality.” Journal of Sport Management 22 (4): 470–486.

- Preuss, H. 2004. “Calculating the Regional Economic Impact of the Olympic Games.” European Sport Management Quarterly 4 (4): 234–253.

- Preuss, H. 2007. “The Conceptualisation and Measurement of Mega Sport Event Legacies.” Journal of Sport & Tourism 12 (3–4): 207–228.

- Preuss, H. 2015. “A Framework for Identifying the Legacies of a Mega Sport Event.” Leisure Studies 34 (6): 643–664.

- Preuss, H. 2019. “Event Legacy Framework and Measurement.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 11 (1): 103–118.

- Putnam, R. 1993. “The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life.” The American Prospect 13 (Spring): 4.

- Saayman, M., and A. Saayman. 2014. “Appraisal of Measuring Economic Impact of Sport Events.” South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation 36 (3): 151–181.

- Scheu, A., H. Preuß, and T. Könecke. 2021. “The Legacy of the Olympic Games: A Review.” Journal of Global Sport Management 6 (3): 212–233.

- Schultz, T. W. 1982. Investing in People: The Economics of Population Quality. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Silva, C., and C. F. Ricketts. 2016. “Mega Sporting Events and Air Pollution: The Case of the Super Bowl.” Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 7 (3): 504–511.

- Solberg, H. A., and H. Preuss. 2007. “Major Sport Events and Long-Term Tourism Impacts.” Journal of Sport Management 21 (2): 213–234.

- Sweetland, S. R. 1996. “Human Capital Theory: Foundations of a Field of Inquiry.” Review of Educational Research 66 (3): 341–359.

- Taks, M. 2013. “Social Sustainability of Non-Mega Sport Events in a Global World.” European Journal for Sport and Society 10 (2): 121–141.

- Taks, M., L. Chalip, and B. C. Green. 2015. “Impacts and Strategic Outcomes from Non-Mega Sport Events for Local Communities.” European Sport Management Quarterly 15 (1): 1–6.

- Terret, T. 2008. “The Albertville Winter Olympics: Unexpected Legacies–Failed Expectations for Regional Economic Development.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 25 (14): 1903–1921.

- Thomson, A., G. Cuskelly, K. Toohey, M. Kennelly, P. Burton, and L. Fredline. 2019. “Sport Event Legacy: A Systematic Quantitative Review of Literature.” Sport Management Review 22 (3): 295–321.

- Thomson, A., M. Kennelly, and K. Toohey. 2020. “A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review of Empirical Research on Large-Scale Sport Events’ Social Legacies.” Leisure Studies 39 (6): 859–876.

- Tóth, B. I. 2015. “Territorial Capital: Theory, Empirics and Critical Remarks.” European Planning Studies 23 (7): 1327–1344.

- Van der Ploeg, J. D., R. E. Van Broekhuizen, G. Brunori, R. Sonnino, K. Knickel, T. Tisenkopfs, and H. A. Oostindië. 2008. “Towards a Framework for Understanding Regional Rural Development.” In Unfolding Webs-The Dynamics of Regional Rural Development, 1–28. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum.

- Vico, R. P., R. R. Uvinha, and N. Gustavo. 2019. “Sports Mega-Events in the Perception of the Local Community: The Case of Itaquera Region in São Paulo at the 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil.” Soccer & Society 20 (6): 810–823.

- Wallstam, M., D. Ioannides, and R. Pettersson. 2020. “Evaluating the Social Impacts of Events: In Search of Unified Indicators for Effective Policymaking.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 12 (2): 122–141.

- Wilson, R. 2006. “The Economic Impact of Local Sport Events: Significant, Limited or Otherwise? A Case Study of Four Swimming Events.” Managing Leisure 11 (1): 57–70.

- Xing, X., and L. Chalip. 2012. “Challenges, Obligations, and pending Career Interruptions: Securing Meanings at the Exit Stage of Sport Mega-Event Work.” European Sport Management Quarterly 12 (4): 375–396.

- Zawadzki, K. M. 2022. “Social Perception of Technological Innovations at Sports Facilities: Justification for Financing ‘White Elephants’ from Public Sources? The Case of Euro 2012 Stadiums in Poland.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 35 (2): 346–366.

- Zhou, R., and K. Kaplanidou. 2018. “Building Social Capital from Sport Event Participation: An Exploration of the Social Impacts of Participatory Sport Events on the Community.” Sport Management Review 21 (5): 491–503.

- Zhuang, J., and V. Girginov. 2012. “Volunteer Selection and Social, Human and Political Capital: A Case Study of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.” Managing Leisure 17 (2–3): 239–256.

- Zimbalist, A. 2006. The Bottom Line: Observations and Arguments on the Sports Business. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.