Abstract

Our paper highlights that the proliferation of Indigenous sport research has not been focused on examining Indigenous games and sports. Additionally, no one has to date produced a framework for understanding them on their own merits even though these games now form part of a national physical education curriculum. The overwhelming majority of research focuses on Indigenous engagement with the British imports of cricket, the rugby codes, soccer, and Australian Rules football. We argue that this focus serves to diminish Indigenous cultures and adaptability to colonial forces, that, while disruptive, never eliminated Indigenous games and sports which go back as far as 60,000 years. We lay out such a framework in the hopes that future research will ensure that Indigenous games and sports are understood historically and in the present day.

For a long time, we had our own games. We would play all day. Today they play white man’s way. Walpiri People Elder, Yuemendu Central Australia (Batty, Kelly, and McMahon Citation2001).

Boomerang throwing, swimming and a form of netball may have been the extent of the sporting pursuits of the Aborigines. Neil Cadigan in ‘Blood, Sweat and Tears’ (Cadigan Citation1989).

Introduction

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic clearly disrupted sport at all levels ranging from grassroots to elite sport and forced many Australian sporting scholars to reflect on all issues associated with sport. While it is not clear what Australian sport will look like post-pandemic, a very different sporting landscape can be envisaged. The pandemic also coincided with the world-wide Black Lives Matter movement and the 250th anniversary of the arrival of James Cook to Australia. Therefore, it was not surprising that in 2020, one of the dominant Australian discourses focused on the re-examination of the impact of British colonialization. Much of the discussion highlighted the negative and traumatic impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. This renewed focus therefore forced most Australian sporting codes to reflect and grapple with their own policies on the issues raised. At the very least, there was an acceptance that Australian sporting codes had historically ‘not welcomed’ Indigenous Australians and that more needed to be done to provide more Indigenous understandings and engagement in Australian sport. There was an acceptance that Australian sport, which had recently positioned itself as a great advocate for diversity and inclusion, had been a fundamentally racist institution for much of its history. Even the football codes, such as Australian rules and rugby league, which had significant contemporary Indigenous player participation and representation, came under scrutiny. Recent testimonies from former footballers such as Nathan Blacklock (National Rugby League), Steve Renouf and Adam Goodes (Australian rules) provided significant and pertinent examples on how entrenched racism was even in recent years (Pengilly Citation2020; National Rugby League Citation2020). While there is no doubt that the two football codes of rugby league and Australian rules have provided significant leadership in promoting Indigenous perspectives and inclusion in recent years, there was a questioning at the very least of the link between institutionalised racism and these football codes.

Our goal is to respond to these wider developments which have manifested themselves in public and media debates. Our aim is also to both re-examine and re-vision the historical, social, and cultural understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander physical cultures (including games and sports) not merely through the lens of colonial exploitation and repression, but through the lens of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ (will be referred as Indigenous Australian Peoples in this paper) ongoing resistance and engagement with the invasion of colonial sporting cultures.

This research presents a new narrative and a way of understanding of examining Indigenous societies and physical cultures through the impact of colonialism from the inside out. We argue that to understand the present situation, we must examine how colonialism influenced traditional Indigenous games and sports. There is a body of literature which clearly documents that traditional Indigenous games and sports existed during the Australian colonial period (1788–1900) (Stephen Citation2015; Edwards and Edwards Citation2012). While many of Indigenous physical activities and games were increasingly marginalized after 1788, there remains a tradition of Indigenous games and sports that survives into the twenty-first century and continues to be part of everyday practices in many Indigenous communities.

We do not attempt to merely document these games and sports, as this has been achieved by other scholars (Ruddell Citation2015; Stephen Citation2015; Edwards and Edwards Citation2012; Edwards Citation2009; Edwards and Meston Citation2008) and we do not attempt to provide a reason why most of the games and sports disappeared, as other scholars have researched in detail the impact on Indigenous cultures and societies (Hay Citation2019, Citation2010; Phillips and Osmond Citation2018). Rather, we question why there has been so much resistance to acknowledging the phenomena of traditional Indigenous games and sports. One of the key reasons has been the privileging of white/colonial sport as the starting point for analysis. Even more so, this is a form of settler colonial and epistemological violence perpetuated against Indigenous Australian peoples’ knowledges, sports and games. Epistemological violence is the knowledge which is constantly reproduced and is dominated by the white/colonial experts in the field. This monopoly and the control on knowledge operates as ‘violence against the subject of knowledge, the object of knowledge, the beneficiary of knowledge, and against knowledge itself’ (Shiva Citation1987). (For example, in the most cited history of Australian sport, Richard Cashman’s Paradise of Sport, the 2010 edition begins in the colonial period and does not reach Aboriginal Australians until Chapter 8 entitled ‘Aborigines and Issues of Race’ (Cashman Citation1995). Additionally, Daryl Adair argued in 2017 that ‘because of [the] diminution of Aboriginal culture, Indigenous sports and games began to lose their functional relevance (Cashman Citation1995; Adair Citation2017).’ The collection edited by Chris Hallinan and Barry Judd entitled Indigenous People, Race Relations and Australian Sport published in 2014 focuses entirely on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders playing in Western team sports (Hallinan and Judd Citation2014).

In 2008, Ken Edwards began Yulunga by noting that: ‘Sports history in Australia has focused almost entirely on modern, Eurocentric sports and has therefore largely ignored the multitude of unique pre-European games that are, or once were, played’ (Edwards Citation2009). History is always selective, particularly when it is tied up with the settler-colonial national identity. Certain stories are silent, some are recovered. Over the past decade or so there has been an evolution of methodologies in sport history, much of it led by scholars with Australian connections. However, a recent edited collection entitled Methodologies in Sport History published in 2018 did not explore Indigenous knowledge, storytelling and games and sports as a method for historical and cultural analysis (Day and Vamplew Citation2015).

It is our intention to expand the view of Indigenous movement cultures during and after the colonial period, to read them from both the point of view of Indigenous people and from the impact of the coloniser and those who have sought to examine the ongoing impact of colonialism on the Indigenous peoples of Australia. The approach of history from the point of view of the colonised has been increasingly accepted as we expand our range of research methods and listen to a wider array of voices. Jeff Peires working on the Xhosa Cattle Killing in South Africa in his The Dead Shall Arise (Davies Citation2007)and James Belich’s The Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict which similarly examined Maori perspectives on the land wars in Aotearoa New Zealand began a trend which has been slow to emerge in the history of sports and physical activity in Australia, but is becoming more and more accepted internationally (Belich Citation1989).

As John Nauright has discussed in previous work, John Bale’s Imagined Olympians examines ways in which the Tutsi physical cultural practice of gusimbuka urukiramende was misinterpreted as a form of high jumping to explain it in terms of Western sportised cultural analysis (Bale Citation2002). Bale argues a number of works that discuss sport and empire, ‘they are characterized by an unwillingness to attempt an excavation of colonial representations of pre-colonial movement cultures’ (Bale Citation2002). In several illustrations of gusimbuka, Bale states these produced a variety of ways of seeing Africa and the African in the West: ‘as exotic, mysterious, powerful – and as athletic’ [emphasis added]. However, Bale reminds us that within Rwanda itself, the result of representations of Tutsi body culture led to them being viewed as a super ‘race’ of athletic bodies shaped in European discourse, and, by implication, the Hutu were different or inferior as they did not have a similar body culture tradition. Here, Bale touches on a crucial point that requires further analysis in the history of sport in colonial contexts. However, few analyses start from reading local communities and activities from the inside out, but, rather, view the Global South as a place where ‘development’ could happen with the right kinds of inputs (Bale Citation2002; Nauright Citation2014).

As we stated above, historians of sport, colonialism and Indigenous Australia have been mostly silent on the phenomenon of Indigenous physical cultures and games. When Indigenous sport was documented, it was from the perspective of famous Indigenous Australians who played mainstream Anglo-Australian sports, the athletes who Colin Tatz referred to as the ‘black diamonds’ or the Indigenous teams who played Anglo-Australian sports such as the 1868 Indigenous cricket team which toured England (Condon Citation2018; Whimpress Citation2003; Tatz and Tatz Citation1996; Tatz Citation1995). In recent work, innovative historians Gary Osmond and Murray Phillips demonstrate how the popular sport of marching became part of identity among Indigenous women in Queensland. This work is of vital importance in showing dynamic interaction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in a particular activity, but this work is scratching a large surface and there are many other zones of interaction to explore (Phillips and Osmond Citation2021). Furthermore, marching activity is a disciplinary tool for cultural assimilation. Hence, making it easier to integrate Aboriginal people into the dominant culture and as a result diluting and suffocating knowledges associated with Indigenous games.

We argue participation in sport (post-1788) was first a representation of British, and then Australian nationalism in the settler colonies. This therefore meant that Indigenous games and sports could never feature in any narrative related to the history of Australian sport, as Indigenous games and sports stood outside this narrative. This is similar to how John Bale documented Western perceptions of Tutsi ‘high jumping’ mentioned above, in which he argues that Indigenous movement cultures were ‘sportized’ so that they could be understood by Western audiences and officials (Bale Citation2002). While we have accounts of Aboriginal movement cultures from contemporary sources, we have not interrogated them in the way Bale has done in Africa.

Why is it important to re-examine Indigenous games and sport? What is the significance of this research? The answer for the justification of this paper is simple and, as the Black Lives Matters movement has demonstrated, there are still some unfinished understandings and ongoing impacts of colonialism. While one of the catch cries of Australian politicians is ‘we are a sport loving nation’ there has been a lack of critical understanding and engagement of how and why this was achieved. During the height of the 2020 pandemic, Prime Minister Scott Morrison claimed that the ‘Australian cricketers would provide Australians with courage and inspiration in the fight against the pandemic’ (Topsfield Citation2020). Who is included and who is excluded? Why and how did sport assume such significance in our society? Is it still the case? Why is there very little reference in the public domain made to non-British sports in Australian history?

In the 2020s, with the 250th anniversary of the British claiming Australia, the public interest generated by the Black Lives Matters movement and the impact on the pandemic, it is time to re-conceptualise the Indigenous link to Australian sporting history. A start is to provide a neglected theoretical understanding of traditional Indigenous games and sports. As international cricket commentator and former West Indies test match player, Michael Holding states in Why We Kneel, How We Rise (2021), we must recover historical experiences to rise above them. Understanding what continued against all odds, as he discusses with Australian Football League legend Adam Goodes, is necessary so that we can move forward with new understanding (Holding and Hawkins Citation2021).

British imperialism and sport

There is a substantial body of literature that has documented and reinforced the centrality of sport in the British Empire (Mangan Citation1998, Citation2001; Sandiford and Stoddart Citation1998; Holt Citation1990; Nauright and Chandler Citation1996). Scholars agree that sport emerged as a central tenet of the British after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. It was institutionalised and organised in the elite rich public schools and alongside elite endeavours in the community in the mid-1800s. Ultimately it became an institution that was central to what it is to be British. Wherever the British colonised, sport was immediately promoted at two levels. First, the elite demonstrated their Britishness, by supporting leisurely sports such as cricket, horseracing, bowls, hunting and others. It demonstrated their allegiance to the home country in a class-based ideology. Second, sport was institutionalised in the education system through private secondary schools and universities, where sport became central to the construction of gender and youth.

Therefore, this code was transplanted to Australia and strictly adhered to; a code that promoted sport. In the school setting it involved cricket, football, rowing, and athletics and in the non-school (community) setting it involved an interest in sport such as horseracing, coursing and bowls (Cashman Citation1995). While sport was initially a central feature of middle-class Australian society, ultimately it became a classless, though racial, ideology because sport was later promoted to and adopted by the working classes. Australian government public schools took on the British ideology and professional sports were promoted for the working classes to both play and support during the latter 1800s. There is no doubt that sport reinforced class, by nature of the different type of sports played and supported. There is also no doubt that all classes had a passion and opportunity to play sport and watch sports. As Cashman noted, Australia became a ‘paradise of sport’ and sport ultimately became a definer of what it was to be an Australian (Cashman Citation1995). What Cashman minimized, or took for granted in this text, was that it was a definer of what it was to be Anglo-Australian, which itself was initially a reinforcer of a white British global nationalism, a nationalism of ‘Greater Britain’ which was a popular idea between the 1860s and World War One, during the colonial period and a reinforcer of Australian nationalism later in the twentieth century (Bell Citation2007). In other work, Cashman examined the life of Fred ‘The Demon’ Spofforth who epitomised the Anglo-Australian and even lived in both Australia and England during his life as did the famed ‘Bodyline’ bowler Harold Larwood who played a half century later (Cashman Citation1990).

Tony Collins provides the most authoritative account of the meaning of Australian sport in the colonial era and in the contexts of the major football codes of Australian rules football and rugby union (T. Collins Citation2019, Citation2015, Citation2011). In the context of Australian football history in the colonial era, rugby union and Australian rules are, as Collins notes, a ‘declaration of British nationalism, not a declaration of Australian nationalism’ (T. Collins Citation2011). As Patrick McDevitt states, ‘The British elites sought to win the hearts and minds of their subjects through the hegemonic propagation of imperial sport and the associated middle-class white values to the peoples of Empire and the working classes’ and that ‘Australian rules footballers held largely to the same code of sportsmanship as English rugby players’ (McDevitt Citation2004).

This link to British nationalism is clear in the colonial period and is perhaps best demonstrated by the establishment of sport clubs in the press. In the colonial press, male citizens are urged to perform their duty and support the clubs. This occurred for everything including food, fashion, and architecture. Words used to promote sport include ‘the ancient sport of’, ‘the English game of’ and ‘the old English pastime’, with clear references to England (Ditchfield Citation1891). For the most part there were rarely references to sport being a response to be being an ‘Australian’ or a ‘Victorian’ or a ‘New South Welshman’. Sport is linked to being a subject of the British Empire and supporter of British nationalism (Ditchfield Citation1891; Armstrong Citation2020). The press informs readers of the ‘revered English tradition’, providing historical examples of the importance of sport and the playing of sport in British history. Sport is privileged in the press. The agitation for sport in the press always accelerated with the establishing of a new sport, a new club, or the inauguration of any sporting event. It is a reinforcement of the institution of sport, and of proving one’s Britishness.

This privileging of sport in the British Empire was a source of great pride for the British and it defined who they were. Sport became a central institution in the various British colonies, not by chance, but because of colonialism. From the first arrival of the British in 1770 there is a clear sporting presence. Two of the key figures of the Cook expedition in 1770, Joseph Banks and Constantine Phipps, had both played sport at Harrow and Eton. Banks was both a school athlete and local town athlete. As President of the Royal Society for 40 years, Banks became a major figure in the British world and one of the great advocates for the colonisation of ‘the great southern land’. Based on his very limited time at Botany Bay, Banks had produced ‘A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales’ in 1783 (Maiden Citation1909). The arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 was an invasion and the Indigenous peoples were progressively subjugated though not without resistance. The frontier war ultimately was a staggering assault to Indigenous life and cultures which lasted for over 130 years (Goodall Citation2008; Trudgen Citation2000; Reynolds Citation1989).

While debates over Australia’s history came to be crudely represented in binary accounts of ‘white blindfold’ versus ‘black arm band’, in 2020 Australian historians presented a clear picture of the destruction caused by the British to Indigenous Australians’ cultures and societies and Indigenous ways of life (Reynolds Citation2021). The arrival of Cook in 1770 marked the beginning of the end for the ancient way of living for the Indigenous population. Cook’s voyage of exploration had sailed under instructions to take possession of the ‘Southern Continent’. Within months of the First Fleet arriving in 1788, the Sydney colonists had destroyed a way of life that had outlasted British history by tens of thousands of years. The Indigenous peoples soon realised that the British wanted total occupation of the land. The Indigenous populations were ravaged by diseases such as smallpox as had Indigenous peoples in the Americas in what historian Alfred Crosby refers to as ‘ecological imperialism’ (Crosby Citation2015). To most settlers, the Indigenous peoples were considered in the same light as kangaroos, dingoes and emus, strange fauna to be eradicated to make way for the development of farming and grazing (Rowley Citation1972). British colonization reduced the size of the local Indigenous population in a very short space of time. Several scholars claim that in the first 20 years of British settlement almost 90% of Indigenous Australians had perished due to disease and atrocities. More importantly, the British had portrayed and conceptualised the Indigenous way of life as primitive, inferior, and needing to be wiped out. It was a way of justifying colonialism. It is only recently with a re-examination of available documents that new understandings of Indigenous ways of life, knowing, doing, thinking and being have emerged. These new understandings also include portrayal of how sophisticated Indigenous cultures were. While there are several discussions on a range of issues, there is nothing on Indigenous games and sport. Central to this debate was Bruce Pascoe’s book Dark Emu which used original eyewitness accounts by colonial explorers and settlers to reassess Indigenous Australians’ way of living not as ‘mere hunter-gatherers’ but as ‘farmers and agriculturalists’. The best-selling and award-winning book triggered others which critiqued Pascoe’s thesis and questioned his use of sources (Pascoe Citation2014). On the surface, the neglect of sport in all these discussions was quite surprising, but a deeper analysis provides no real surprise.

Why would modern Australian scholars (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) be investigating or looking for Indigenous games and sports during the colonial period? Sport has been one of the few areas where, in recent years, Indigenous Australians have been publicly recognised and applauded by white Australians. There are now dozens of publications in respected outlets that document the strong Indigenous sporting manifestations in the last two decades and acknowledge that Indigenous Australians have succeeded (Hallinan and Judd Citation2014; Tatz Citation2009, Citation1987). This fascination of the link between sport and Indigenous issues has only been seen through the prism of modern British sport. There have been several themes covered in this body of literature such as literature that examined sport as a panacea to address Indigenous inequality. How do you address Indigenous incarceration rates? Give them settler colonial sport. How do you address lower education and health outcomes? Give them settler colonial sport (Evans et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, Evans et al. (Citation2015) highlight:

Participation in sport among Indigenous Australians has been proffered as a ‘panacea’ for many Indigenous problems; from promoting better health and education outcomes, to encouraging community building, good citizenship and entrepreneurship. Parallel to this has been a focus on documenting and analysing sport participation among Indigenous Australians in elite sport which often concludes that Indigenous Australians have an innate and ‘natural ability’ in sports. These two assumptions, first, that sport participation can help realise a wide range of positive social outcomes; and second, that Indigenous Australians are natural athletes, have driven significant public investment in numerous sport focused programs. (27)

The lack of attention is surprising as even a cursory investigation of the available sources of early Indigenous descriptions provides clear evidence of Indigenous Australians taking part in their own sporting traditions. These descriptions were documented by explorers, educationalists, government officials, scientists, ethnographers, missionaries, and others. There are very few descriptions which were documented by Indigenous Australians. The sporting depictions were noted in the first couple of years after the arrival of the British. In 1791, three years after the arrival of the First Fleet, Bennelong ‘had chosen the time for celebrating funeral games of his deceased wife’ (D. Collins et al. Citation1804). Bennelong was an Elder of the Eora people of Sydney Harbour and served as interlocutor between the local Indigenous peoples and the British in Sydney. Barangaroo was Bennelong’s wife, and she was buried in Governor Phillip’s Garden, in present day Circular Quay. Quickly, Indigenous voices were marginalized as soon as the British arrived in Australia.

Early French explorers and visitors to the colony in Australia provide clear evidence of physical activities and sports taking place. They describe the Indigenous population wrestling and taking part in various throwing and catching games, and that both men and women were proficient ocean swimmers. French explorer Baudin explored Australia. In 1802 on Bruny Island his party encountered a group of Indigenous people where wrestling was taking place. There is a written description of a wrestling match between one of the French sailors and an Indigenous youth (Péron Citation1975).

Throughout the Australian colonial period there are clear depictions of games taking place among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. While most of the games are related to hunting and survival skills, there are clear patterns of types of games. In the late 1890s Roth provided eight categories for traditional Indigenous games. In 2001, Kovacic divided games into three forms, while Slater also provided a typology (Kovacic Citation2001). Games were clearly organised and aimed at educating Indigenous youth. Returning boomerangs were not used for hunting but rather were devised for boomerang games. Indigenous peoples developed modified boomerangs to get them to return. The first swimmers of Bondi Beach were not British but Indigenous Australians (Booth Citation2021, Citation2023). The first ball games were not played with imported footballs from England in the 1860s, but rather balls made from possum or kangaroo skins by Indigenous Australians. Polished stones, like ones used for British bowls, were used for Indigenous target games such as ‘Koolche’ and ‘Weme’ by the Arrernte People of the central desert. Perhaps the most played sport of all was the various ‘hockey’ type games that existed throughout Australia (Edwards Citation2012a).

Our aim is not to provide a detailed description of Indigenous sports in the colonial period but to simply note that they clearly existed. British officials ultimately never reported on the complexity and standing of Indigenous games and sports or even for that the Indigenous peoples had sports. This is because of accounts of Indigenous life would in no way shape or form acknowledge that ‘primitive’ Indigenous peoples played, organized, or enjoyed sport, a form of ongoing epistemic and colonial violence. Sport was something that only the British did, a signifier of high culture, so it is not surprising that traditional Indigenous games and sports were air brushed out of Australian historical accounts until recently. In his pioneering account of the history of Australian sport, Cashman (Citation1995) reflects this tendency by including a cursory reference at the start of the book, related to Indigenous sport:

The original inhabitants of Australia had their own traditions of sport – there were many forms of physical contests when bands went wrestling, spear-throwing contests, sham fights, primitive forms of football involving possum skin ball, spinning discs and stick games. (12–13).

But what about the research which hints at Indigenous mainstream sporting participation within Australia? There are now several publications that highlight sporadic individual Indigenous athletes and participation in teams in the settler colonial period [1788–1928]. One of the more frequently quoted examples is the cricket which was taking place on the Poonindie Aboriginal Reserve in South Australia from the 1850s. This institution was founded in 1850 by Reverend Hale in a well-meaning attempt to:

allow students of the Adelaide native School Establishment who had received a good primary education, to grow up in a European, Christian environment, well removed from their tribal relatives. … He had also introduced the game of cricket, which immediately proved very popular. On a visit to Poonindie in 1853 Bishop Short had been impressed with the ‘neatness in fielding and batting’ of two native elevens playing on the Poonindie Oval. (Tregenza Citation1984)

The promotion of cricket to Indigenous peoples was related to attempting to ‘civilise’ them, by giving religion, language, and sports. When Cashman and others wrote about the history of Australian sport, Indigenous Australians were seen and viewed in relation to imported British sports. Indigenous Australians are latecomers to Australian football, and it is only from the 1980s onwards that they regularly appear in elite level competition primarily in rugby league and Australian rules (Hess Citation2008).

Even in the modern era, the football codes were resistant to harness the talents of Indigenous athletes. In rugby league, the Koori Knockout Cup, an Indigenous knock-out competition, was primarily initiated in 1971 because Indigenous players were finding it hard to break into the elite professional rugby league competition organised by New South Wales Rugby League (Norman Citation2012). Apart from a few high-profile Indigenous players such as Arthur Beetson and Yoh Yeh, there was no place for them in elite rugby league competitions. Yoh Yeh died in custody, less than ten years after making his debut for the Balmain Tigers Rugby League Football Club after moving from Queensland to Sydney with Arthur Beetson (Reed Citation2013).

From the 1990s onwards there were policies in place to broaden the appeal of Australian rules football by encouraging new fans and players (Hess Citation2008). For example, Indigenous players appeared at the elite level and strong links to Indigenous Australians were developed by this code. Prior to the 1990s, only a handful of Indigenous players, approximately 20, had played in the Victorian football league (1897–1989).

In the era of neoliberalism and media sport, Australian rules football mobilised to broaden its appeal, with the catch words of ‘diversification’, ‘inclusion’ ‘new markets’ and ‘new fans’. The Victorian Football League transformed to the Australian Football League and teams were relocated to rugby league and rugby union strongholds (Sydney Swans and Brisbane Lions), while teams in South Australia (Adelaide Crows, Port Adelaide) and Western Australia (West Coast Eagles, Fremantle Dockers) were added to the competition. As part of the 150 years celebrations, certain Australian rules football authorities pushed and promoted the narrative that the founders of the sport, such as Tom Wills, had been influenced by the Indigenous game Marngrook which was, according to them, played in Victoria where Wills resided (Gorman et al. Citation2015). A mysticism is introduced to the founding of Australian rules: it becomes not only an Australian game, a game invented by Australians, but a game with Indigenous roots. An amalgam. But why did it take until 2008 to link Australian rules football to Indigenous games and sports?

The answer to this question is simple. When the AFL celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2008 it saw itself as the Australian game, the code which includes all cultures, and the Indigenous link became central to this legitimization. As a society that previously demoted and neglected the Indigenous sporting link, suddenly there was a celebration of traditional Indigenous football. Advocates of this standpoint of history refer to the lithographs taken by German immigrant William Blandowski in the late 1850s in Victoria showing Indigenous Australians playing various ball games (Blandowski and Harry Citation2010). This is the first mainstream and public mention of Indigenous Australians having their own sporting traditions. Indigenous games and sports are not only acknowledged but heralded. There is one lithograph of a group of Indigenous Australians kicking a ball (see ). If anything, it looks more like soccer than Australian rules and the caption of the lithograph reads ‘never let the ball hit the ground’.

Figure 1. Aboriginal football by William Blandowski, 1850s. Source: Blandowski and Harry (Citation2010, p. 87).

The area where the lithographs were sketched in Victoria was where one of the founders of Australian rules, Tom Wills, resided. It is documentation that was promoted mainly by Australian rules advocates in their quest to become the major winter sporting code in Australia after 2000. Prior to this period, these lithographs were largely unknown and not acknowledged. But in 2008, they emerged as a symbol of what Australian rules represented in 2008. AFL had become the code that promotes diversity from all parts of society including Indigenous; the code that started off as Melbourne rules and recently became Australian rules. The code which promotes diversity from all parts of society, including Indigenous, remains predominantly the domain of Anglo-Celtic colonial Australian-ness, thus allowing greater emphasis on extreme minority diversification when it arises. The diversity that it acclaims only becomes apparent because of the majority whitewash of its natural, overriding self.

We have established that colonialism was intertwined with sport as the British Empire was underpinned by the Imperial sporting ethos. However, this sporting ethos was not for all. It is gendered and only males, white males, should be represented. It could not and would not feature, therefore, in the traditions of the Indigenous population. Cricket was first played in Sydney in 1803 and the first horse racing meeting took place in 1810. The sport of cricket was the first sport promoted in the school system and supported by the elites. There was a growth of the various sports, which was a demonstration of the locals replicating the home country institutions and the colonists demonstrating their Britishness. There was a growth in the various sports, which was a demonstration of the locals replicating the home country institutions. Empire loyalty and national identity, the invention of sport as an imperial ideology and Australian practice from the eighteenth century to Federation and beyond. These impacted class, gender, ethnicity, and Indigenous participation.

Documentation of Indigenous games and sport

We do not aim to document the existence of all Indigenous games and sport as was attempted by Ken Edwards and Troy Meston. In 2008, the authors produced the most sustained and authoritative account of surviving Indigenous games and sports in Yulunga (Edwards and Meston Citation2008). In their various publications Edwards and Meston, both documented contemporary Indigenous games and sports and provided accounts of existing references and documentation of Indigenous games and sports. Edwards and Meston also documented sports that they believed may have developed after colonisation or were a result of it. In their definition of what constitutes. Indigenous games and sports, they provided the following definition (Edwards Citation2012b):

Traditional games include [sic] all aspects of traditional and contemporary play and movement expressions that are, or have been, developed, repeated and shared informally and/or formally within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and its identifiable present-day cultural groups or communities, and are generally accepted by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as being a part of, and/or an adequate reflection of their social identity. (7)

Typology 1: Eyewitness accounts

The process and influence of colonisation occurred at different times and places and in different ways across Australia, so the documentation of Indigenous games and sport was possible and did occur. Most of these accounts occurred in the second half of the 1800s in northern and central Australia. These firsthand accounts are important because they clearly show a continuity of Indigenous sporting traditions. Edwards was able to locate and compile many references to Indigenous games and much of the following is based on his work.

Three individuals (Walter Roth, Daisy Bates and Alfred Haddon) provide the most thorough descriptions of games and sports. In 1929 Daisy Bates wrote that wrestling, which was first documented in 1792 by the French, was still practised in 1929: ‘The young men engaged in this pastime placed their hands on each other’s shoulders, and struggled, pushed and pulled until one of them fell’ (Bates Citation1929). The sporting depictions are located in the ‘Dance, Songs and Games’ section of her collections. Bates notes (Bates Citation1929):

There were also climbing contests in the big timber areas, the women taking the lead in this pastime also. The highest and broadest trees in the Southwest were climbed with no other aid than their native axe afforded. They cut a notch in the tree above their heads, and then sticking the pointed end of the axe into the bark, they raised themselves up by its aid, their left hand clasping the tree. Their great toe was inserted in the holes thus made and in an incredibly short time they reached the top of the tree by this means. Many of the southern trees still bear the marks of climbers who have long since passed away. (36)

The blacks here swim in a far more vertical position than we do: furthermore, instead of “breasting” the water, the right shoulder appears to occupy the most advanced position. The right arm, starting with bent elbows, makes a clean sweep downwards, outwards, and backwards until, at the end of the stroke, the elbow is fully extended. The left arm remains sharply bent throughout its stroke, and limits a far smaller circle, the elbow appearing above the water-surface at each stroke. (68–69)

The most energetic of these games is a kind of hockey, shinny or shinty, which is played everywhere. It is called kokan in Mabuiag, which is also the name of the ball itself. The ball is made of wood and varies from about 55 to 60 mm in diameter and 3.5 to 4 oz. in weight, the largest being 78 mm and 10 oz. It is struck with a roughly made bat or club, bawain, dabi, which is usually a piece of bamboo, varying from 60 to 85 cm in length, on which a grip is cut. The game is played over a long stretch of the sand-beach, there are two sides and each player has a stick …. The game is very ‘fast’ and causes intense excitement and a tremendous noise; it is not without an element of danger as the heavy ball is hit with extreme vigour. We witnessed in Mabuiag one great match between married and single men. (314)

Games are also discussed in Berndt (1940), Harney (1952), and Salter (1967, 1974). The work of people such as Basedow (1925), McCarthy (1960), Robertson (1975), Oates (1979), Miller (1983), Factor (1988), Atkinson (1991) and Haagen (1994) also provide information about traditional games. Margaret Lawrie made several visits to the Torres Strait Islands area between the 1960s and 1970s and recorded many of the stories, language and traditional games of the people (p.35).

Typology 2: Edwards’ documentation of Indigenous games and sports in Yulunga

In July 2008, Ken Edwards launched an Australian Sports Commission initiative and reviewed every available account of traditional Indigenous games and sports and reproduced 140 games in one document titled Yulunga, which means ‘playing’ in the language of the Kamilaroi people of north-western New South Wales. The endeavour took more than a decade to research and the games came from all parts of the country. It was primarily designed to be used in schools, sporting organisations and community groups throughout the country as an educational resource. A description of each of the games includes information around the background, context and location of where the game came from, the language to use, and a description of the game and the rules that apply. An example of one of the games is included below (): Tur-dur-er-in (a type of wrestling). Many of the original accounts of Indigenous games were recorded during the nineteenth century by explorers, government officials, settlers, scientists and missionaries. The project also involved consultation with Indigenous communities nationwide to ensure the activities included were an accurate reflection of Australian Indigenous play culture. The document is important because it recognises that Australian sport is much older than 250 years.

Figure 2. Tur-dur-er-rin. Source: Edwards and Meston (Citation2008, p. 241)

Typology 3: Newspaper articles

Another source of documentation of Indigenous games and sports is in the mainstream press. There are innumerable reports of Indigenous games and sports that have not featured in any research. While Australian sporting historians use the press to document the establishment and consolidation of sports in Australia, there has been no similar attempt to do so for Indigenous games and sports. The mainstream Australian press is an untapped source of evidence that could be used to document and better understand Indigenous games and sports. This information could complement the information from the first two typologies.

Articles usually reported on Aboriginal people from various local districts meeting and competing against each other (see ). One example in the Evening-News-Sydney (Citation1892): ‘about 120 representatives of the once powerful and dangerous Clarence River blacks’ entered events such as ‘tree climbing with knives, and double boomerang throwing (6). In Barambah, Indigenous sports were still taking place in 1924, between northern men versus a combined southern and western team (Maryborough-Chronicle Citation1924). There seem to have been annual games such as the ones in Queensland covered in the press (The-Courier Citation1903) in the early 1900s where there were competitions in ‘Aboriginal Sports’ which were a celebration of traditional sports such as ‘spear-throwing’ and ‘return-boomerang’ who would throw it ‘exactly as it was thrown a hundred years ago, before white appeared on the scene’ (4). These annual games are important because they refer to not only the type of sports but more importantly a system that had been in place for their promotion. While Aboriginal men from all over Queensland took part, the best of the various tribes attended. The games were both organised and structured.

Conclusion

After 1788, many pre-existing Indigenous games and sports declined as the Indigenous societies and cultures which supported them were substantially disrupted by British colonisation. Anglo-Australian sports such as cricket were introduced on missions and settlements as part of assimilationist policies. It was a process of ‘civilising the natives’ and teaching them British values. In a few places, mainly central and northern Australia, traditional games and sports from before colonisation persisted. The nature and role of traditional sports within Indigenous cultures, both past and present, is often overlooked or is poorly understood by historians of Australian sport. This paper hints at a reason for this neglect. Almost 20 years ago, Daryl Rigney (Citation2003) reflected on scholarship on Indigenous Games and Sports:

One of the ways to colonize a people is to control their ability to represent themselves. One of the ways to subvert colonization is to retain or recapture the process of representation, to set the scene for counter-hegemonic anti-colonial narratives. This chapter aims to contribute to the field of anti-colonial scholarship by exposing the relationship between Australian colonial knowledge and Australian colonial power, in and through sport. In Australian cultural life, sport has long held a reified standing. As a result sport has often escaped critical examination, and thus Australians have failed to see the extent to which it is socially conditioned and influenced by the political and economic power of the nation-state. The location of Indigenous people and sport in a historically and politically racialized context enables insights into the historical construction of dominance and the roles of political, economic and cultural institutions in society. (45)

In 2019, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated more than 46% of Indigenous Australians had a chronic health condition that presented notable health risks and 37% of Indigenous children aged 2–4 years were considered overweight or obese. There was also an eight to nine-year gap between the life expectancy of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The gap in health and education has widened, not narrowed. In addition, Evans et al. (Citation2015) warned about making non-Indigenous sports the ‘panacea’ for all Indigenous problems, especially for youth. They warned sport had become a silver bullet for policy makers. Sporting organisations mobilised to acknowledge and promote Indigenous representativeness. One way forward may be to link Anglo-Australian sports to Indigenous sports described in Yulunga. Many of the sports are similar. Lawn bowls was first played in Australia in the mid-1840s at about the same time Joseph Jukes in 1843 described a type of Indigenous lawn bowls where ‘flat tabular pieces of stone, about the size of an octave volume, were stuck upright on the sand in a certain order, while others both flat and round, were lying dispersed about’ (Jukes Citation1847). Edwards presented several lawn-based target games in Yulunga such as Koolche and Weme.

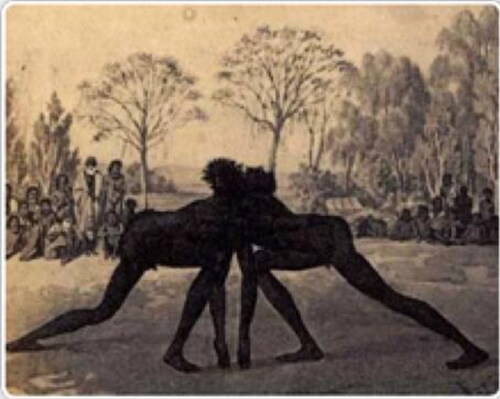

At the very least there should be an acknowledgement that Indigenous games and sports existed as we revise the totality of Australian movement cultures. What is needed is a more detailed analysis of storytelling through yarning where Indigenous voices contribute to the histories of their games and sports. This, when combined with documentary sources, can tell a powerful story (Nauright Citation2010). As we have demonstrated, their presence was documented and widespread. Wrestling is documented systematically from 1788 onwards, from the French in 1892 until Edwards’ numerous descriptions of the various forms of wrestling in Yulunga (boojur kombang, epoo korio, garunba, kari woppa). In the mid-1850s Blandowski depicted wrestling visually and this is reproduced below (). More than that, Blandowski informs us that this was a structured sport:

Figure 4. Aboriginal wrestling by William Blandowski, 1850s. Source: Blandowski and Harry (Citation2010, p. 95)

When these men are found they start the wrestling games, tournaments that do not involve the spectators. The men grease their bodies and meet in the shade of a tree. They use handfuls of dirt from the ground to make their opponents easier to grip. Only the viewing of the fight itself can give a good picture of the fighters and the suppleness of their muscles; a depiction through picture and words is not enough.

In 2008, Ken Edwards began Yulunga by noting that: ‘Sports history in Australia has focused almost entirely on modern, Eurocentric sports and has therefore largely ignored the multitude of unique pre-European games that are, or once were, played’ (Edwards Citation2009). History is always selective, particularly when it is tied up with national settler colonial identity. Certain stories are silent, some are recovered. It is in this space that we need to work with Indigenous communities to tell their stories and to move beyond stereotypical analyses of athleticism, dominance, innovation, etc. to listen to stories and evidence from Indigenous Australians about their movement cultures and the impact of imperialism and marginalization as well as resilience in the face of domination. As Edwards and Meston (Citation2008) stated, ‘There are comparatively few descriptions of games and sports by Indigenous people, but efforts have been made to include a significant level of Indigenous input’. He made a valiant start, but there is much more to do. We have charted where voids have existed and provided explanations as to why, now it is time for us to continue the work of Edwards and weave Aboriginal movement cultures more fully into histories and contemporary understanding of all sports and games in Australia. The fight for fair treatment of Indigenous games, sports and related knowledges must come from Indigenous exponents, athletes, and Indigenous people themselves. The settler colonials have a collective responsibility of learning about the history of the unceded Lands where all sports and games are played, including privileging the Indigenous voices. The deniers of colonial and epistemic violence are promoting absence of ethical thinking.

Disclosure statement

Tarunna Sebastian is a Pitjantjatjara and Anmatyerre woman from Central Australia; Steve Georgakis is a leader with the other authors in integrating Aboriginal movement cultures into physical education training at The University of Sydney, John Nauright is the editor of two key books on race and ethnicity in sport and is a part Mvskoke American Indian man.

References

- Adair, Daryl. 2017. “Australia.” In Routledge Handbook of Sport, Race and Ethnicity, edited by David K. Wiggins and John Nauright, 146–159. London; New York: Routledge.

- Armstrong, Eleanor. 2020. “Australian Cultural Populism in Sport: The Relationship between Sport (Notably Cricket) and Cultural Populism in Australia.” ANU Undergraduate Research Journal 10 (1): 68–76. https://studentjournals.anu.edu.au/index.php/aurj/article/view/284.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting (ACARA). 2016. “The Australian Curriculum Health and Physical Education.” ACARA. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/health-and-physical-education/?year=12997&year=12998&strand=Personal%2C+Social+and+Community+Health&scotterms=false&isFirstPageLoad=false.

- Bale, John. 2002. Imagined Olympians: Body Culture and Colonial Representation in Rwanda. Vol 3. Sport and Culture Series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bates, Daisy. 1929. “Songs, Dances, Etc. – Games, Amusements.” https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/103288/1/Daisy%20Bates%20-%20Games%20and%20Amusements.pdf

- Batty, David, Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, and Jennifer McMahon. 2001. Motorcar Ngutju: Payback: The Chase: The Rainmaker 2001. NSW Australia: University of New South Wales Press.

- Belich, James. 1989. The Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict: The Maori, the British, and the New Zealand Wars.acls Humanities e-Book. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Bell, Duncan. 2007. The Idea of Greater Britain Empire and the Future of World Order, 1860-1900. Edited by Course Book. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Blandowski, William, and Allen Harry. 2010. Australia: William Blandowski’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Booth, Douglas. 2021. Bondi Beach: Representations of an Iconic Australian. Singapore: Springer.

- Booth, Douglas. 2023. “Experiments in History: The Voice of Bondi.” Rethinking History 27 (1): 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2022.2158644

- Cadigan, Neil, Don Hogg, Brian Messop, Venetia Nelson, Richard Sleeman, Jim Webster, and Phil Wilkins. 1989. Blood, Sweat & Tears: Australians and Sport/Neil Cadigan … [.]. Melbourne: Lothian.

- Cashman, Richard I. 1990. The “Demon’ Spofforth”. Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press.

- Cashman, Richard I. 1995. Paradise of Sport: The Rise of Organised Sport in Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Collins, David, Philip King, George Bass, and Maria Collins. 1804. An account of the English Colony in New South Wales the Journal of Mr. Bass, by Lieutenant-Colonel Collins. 2nd ed. London: Printed by A. Strahan for T. Cadell, and W. Davies.

- Collins, Tony. 2011. The Invention of Sporting Tradition: National Myths, Imperial Pasts and the Origins of Australian Rules Football, 8–31. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Collins, Tony. 2015. “Early Football and the Emergence of Modern Soccer, c. 1840-1880.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (9): 1127–1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2015.1042868

- Collins, Tony. 2019. How Football Began: A Global History of How the World’s Football Codes Were Born. 1 ed. Milton: Routledge.

- Condon, Anthony. 2018. “The Positioning of Indigenous People in Australian History: A Historiography of the 1868 Aboriginal Cricket Tour of England.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 35 (5): 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1453499

- Crosby, Alfred W. 2015. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Davies, Sheila Boniface. 2007. “Raising the Dead: The Xhosa Cattle-Killing and the Mhlakaza-Goliat Delusion.” Journal of Southern African Studies 33 (1): 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070601136517

- Day, Dave, and Wray Vamplew. 2015. “Sports History Methodology: Old and New.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (15): 1715–1724. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2015.1132203

- Ditchfield, Peter Hampson. 1891. Old English Sports, Pastimes and Customs. London: Methuen and Co.

- Edwards, Ken. 2009. “Traditional Games of a Timeless Land: Play Cultures in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 32–43.

- Edwards, Ken. 2012a. A Bibliography of the Traditional Games of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Toowoomba, Australia: University of Southern Queensland.

- Edwards, Ken. 2012b. A Typology of the Traditional Games of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Esk, Australia: Ram Skulls Press. https://eprints.usq.edu.au/24916/12/Edwards_typology_PV.pdf.

- Edwards, Ken, and Tim Edwards. 2012. A Bibliography of the Traditional Games of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Toowoomba, Australia: University of Southern Queensland.

- Edwards, Ken, and Troy Meston. 2008. Yulunga: Traditional Indigenous Games. Canberra: Australian Sports Commission.

- Evans, John, Steve Georgakis, and Rachel Wilson. 2017. “Indigenous Games and Sports in the Australian National Curriculum: Educational Benefits and Opportunities?” ab-Original 1 (2): 195–213. https://doi.org/10.5325/aboriginal.1.2.0195

- Evans, John, Rachel Wilson, Bronwen Dalton, and Steve Georgakis. 2015. “Indigenous Participation in Australian Sport: The Perils of the ‘Panacea’ Proposition.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 7 (1): 53–77. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v7i1.4232

- Evening-News-Sydney. 1892. “Aboriginal Sports.” Evening News Sydney, December 29.

- Goodall, Heather. 2008. Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770-1972. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Gorman, Sean, Barry Judd, Keir Reeves, Gary Osmond, Matthew Klugman, and Gavan McCarthy. 2015. “Aboriginal Rules: The Black History of Australian Football.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (16): 1947–1962. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2015.1124861

- Haddon, Alfred. 1912. ‘Games and Toys’ in Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits: Volume 4, Arts and Crafts,. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hallinan, Chris, and Barry Judd. 2014. Indigenous People, Race Relations and Australian Sport. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Hay, Roy. 2010. “A Tale of Two Footballs: The Origins of Australian Football and Association Football Revisited.” Sport in Society 13 (6): 952–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2010.491265

- Hay, Roy. 2019. Aboriginal People and Australian Football in the Nineteenth Century: They Did Not Come from Nowhere. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Hess, Rob. 2008. A National Game: The History of Australian Rules Football. Camberwell, VIC: Viking.

- Holding, Michael, and Ed Hawkins. 2021. Why we Kneel, How we Rise. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Holt, Richard. 1990. Sport and the British: A Modern History. Oxford Studies in Social History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jukes, Joseph Beete. 1847. “Narrative of the Surveying Voyage of HMS Fly: During the Years 1842-1846.Cambridge Library Collection.” Maritime Exploration. Cambridge: Publisher not identified.

- Kovacic, Leonarda. 2001. “Cataloguing Culture: In Search of the Origins of Written Records, Material Culture and Oral Histories of the Gamaroi, Northern New South Wales.” PhD thesis, The University of Melbourne. https://www.womenaustralia.info/bib/AWP002886.htm.

- Maiden, J. H. 1909. Sir Joseph Banks: The Father of Australia. Syd: Gullick.

- Mangan, J. A. 2001. Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School: The Emergence and Consolidation of an Educational Ideology. 3rd ed., Vol. 13. Sport in the Global Society. Florence: Routledge.

- Mangan, J. A. 1998. The Games Ethic and Imperialism: Aspects of the Diffusion of an Ideal. Sport in the Global Society, [2]. London: F. Cass.

- Maryborough-Chronicle. 1924. “Barambah Aboriginal Sports.” Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, June 23.

- McDevitt, Patrick F. 2004. May the Best Man Win: Sport, Masculinity, and Nationalism in Great Britain and the Empire, 1880-1935. 1st ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Melbourne Cricket Ground. 2020. “Johnny Mullagh Inducted into Australian Cricket Hall of Fame.” Melbourne Cricket Ground. https://www.mcg.org.au/whats-on/latest-news/2020/december/johnny-mullagh-inducted-into-australian-cricket-hall-of-fame.

- National Rugby League. 2020. “Laid Bare: Renouf, Racism and Rugby League.” https://www.nrl.com/news/2020/07/31/laid-bare-renouf-racism-and-rugby-league/.

- Nauright, John. 2010. Long Run to Freedom: Sport, Cultures and Identities in South Africa. Sport & Global Cultures Series. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Nauright, John. 2014. “On Neoliberal Global Sport and African Bodies.” Critical African Studies 6 (2–3): 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2014.956206

- Nauright, John, and Timothy John Lindsay Chandler. 1996. Making Men: Rugby and Masculine Identity. London: F. Cass.

- Norman, Heidi. 2012. “A Modern Day Corroboree - the New South Wales Annual Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout Carnival.” Sport in Society 15 (7): 997–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.723370

- Pascoe, Bruce. 2014. Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? Broome, Western Australia: Magabala Books Aboriginal.

- Pengilly, Adam. 2020. “Blacklock Wants Indigenous Welfare Officer at Every NRL Club.” The Sydney Morning Herald, September 10. https://www.smh.com.au/sport/nrl/blacklock-wants-indigenous-welfare-officer-at-every-nrl-club-20200909-p55tzp.html.

- Péron, François. 1975. A Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere, Performed by Order of the Emperor Napoleon, during the Years 1801,1802,1803 and 1804. Voyage to the Southern Hemisphere. North Melbourne, Vic: Marsh Walsh Publishing.

- Phillips, Murray G., and Gary Osmond. 2018. “Australian Indigenous Sport Historiography: A Review.” Kinesiology Review 7 (2): 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2018-0007

- Phillips, Murray G., and Gary Osmond. 2021. “Tensions, Complexities, and Compromises: Sharing Australian Aboriginal Women’s Sport History.” Journal of Sport History 48 (2): 118–134. https://doi.org/10.5406/21558450.48.2.03

- Reed, Lyle F. 2013. Inquest. Ipswich, Queensland: Lyle F. Reed.

- Reynolds, Henry. 1989. Dispossession: Black Australians and White Invaders. Australian Experience. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Reynolds, Henry. 2021. Truth-Telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement. Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing.

- Rigney, Daryle. 2003. “Sport, Indigenous Australians and Invader Dreaming: A Critique.” In Sport and Postcolonialism, edited by John Bale and Mike Cronin, 45–56. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Roth, Walter Edmund. 1902. “Games, Sports, and Amusements of the North Queensland Aboriginals.”

- Rowley, C. D. 1972. The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. Aborigines in Australian Society; 4. Ringwood, VIC: Penguin Books Australia.

- Ruddell, Trevor. 2015. “The Marn-Grook Story: A Documentary History of Aboriginal Ballgames in South-Eastern Australia.” Sporting Traditions 32 (1): 19–37.

- Sampson, David. 2009. “Culture, ‘Race’ and Discrimination in the 1868 Aboriginal Cricket Tour of England.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2009 (2): 44–60.

- Sandiford, Keith A. P., and Brian Stoddart. 1998. The Imperial Game: Cricket, Culture and Society.Studies in Imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Shiva, Vandana. 1987. “The Violence of Reductionist Science.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 12 (2): 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437548701200205

- Stephen, Matthew. 2015. “Cricket in the ‘Contact Zone’: Australia’s Colonial Far North Frontier, 1869-1914.” Identities 22 (2): 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2014.884972

- Tatz, Colin. 1987. Aborigines in Sport. ASSH Studies in Sports History; No. 3. Bedford Park, S. Aust: Australian Society for Sports History.

- Tatz, Colin. 1995. Obstacle Race: Aborigines in Sport. Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Tatz, Colin. 2009. “Coming to Terms: ‘Race’, Ethnicity, Identity and Aboriginality in Sport.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2009 (2): 15–31.

- Tatz, Colin, and Paul Tatz. 1996. Black Diamonds: The Aboriginal and Islander Sports Hall of Fame. St Leonards, N.S.W: Allen & Unwin.

- The-Courier. 1903. “Aboriginal Sports.” The Courier, October 2.

- The-South-Australian-Register. 1854. “Cricket.” The South Australian Register, February 7, 3.

- Topsfield, Jewel. 2020. “‘Convoluted Waffle’: Prime Minister Lambasted over Mixed Messaging.” The Sydney Morning Herald, March 25. https://www.smh.com.au/national/convoluted-waffle-prime-minister-lambasted-over-mixed-messaging-20200325-p54duj.html.

- Tregenza, John. 1984. “Two Notable Portraits of South Australian Aborigines.” Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia 12: 31.

- Tregenza, John. 1996. Collegiate School of St. Peter Adelaide: The Founding Years 1847-1878. St. Peters, S. Aust: The School.

- Trudgen, Richard Ian. 2000. Why Warriors Lie down and Die: Towards an Understanding of Why the Aboriginal People of Arnhem Land Face the Greatest Crisis in Health and Education since European Contact: Djambatj Mala. Darwin: Aboriginal Resource & Development Services Inc.

- Whimpress, Bernard. 2003. “The Black Lords of Summer: The Story of the 1868 Aboriginal Tour of England and beyond [Book Review].” In Australian Aboriginal Studies: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies 20 (1): 90–91.

- Williams, John. 2017. “Embedding Indigenous Content in Australian Physical Education - Perceived Obstacles by Health and Physical Education Teachers.” Learning Communities: International Journal of Learning in Social Contexts 21: 124–136. https://doi.org/10.18793/lcj2017.21.10

- Williams, John. 2018. “I Didn’t Even Know That There Was Such a Thing as Aboriginal Games’: A Figurational account of How Indigenous Students Experience Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (5): 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1210118