Abstract

A challenge in safeguarding children from interpersonal violence (IV) in sport is the reliance on self-disclosures and a limited understanding of the frequency, barriers to and process of disclosures of IV. Through a mixed-methods design, combining survey and interviews, we explored the frequencies of childhood disclosures of experiences of IV in Australian community sport as well as who children disclosed to and how the interaction unfolded. Those who experienced peer violence disclosed at the highest frequency (35%), followed by coach (27%) or parent (13%) perpetrated IV. A parent/carer was most often the adult that the child disclosed to. Interviews highlighted how the normalisation of violence influenced all aspects of the disclosure and elements of stress buffering (normalising or rationalising) particularly underpinned the disclosure interaction. Policies and practices should explicitly identify all forms of IV in sport as prohibited conduct; education and intervention initiatives should target parents as first responders to disclosures.

Introduction

Safeguarding athletes, particularly children, against interpersonal violence (IV) in sport is becoming a focus for both policy and practice within sporting organisations at every competition level. Recent headlines of high-profile abuse cases in sport (e.g. USA Gymnastics, Swimming Australia) indicate the systemic nature of violence against children in sport and the long-term mental and physical consequences of failures to safeguard sport participants and athletes (Pascoe et al. Citation2022; Vertommen et al. Citation2018). International research has reported high frequencies (44–86%) of experiences of IV against children in sport (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023; Parent and Vaillancourt-Morel Citation2021; Vertommen et al. Citation2022; Vertommen et al. Citation2016). From a management perspective, while these data are critical in highlighting the extent and nature of IV against children in sport, understanding how disclosures of all forms of IV in sport occur is equally important (Hartill and Lang Citation2018). Delayed disclosures of IV (or never disclosing) can have severe and long-lasting impacts on the mental wellbeing of the child and also leaves the experiences of IV undocumented and unaddressed (Alaggia Citation2010; Ruggiero et al. Citation2004).

Collectively, various types of IV have been referred to as abuse, maltreatment (Stirling Citation2009), or non-accidental violence (Mountjoy et al. Citation2016), to encompass a variety of behaviors including, but not limited to, sexual, psychological/emotional and physical IV, neglect, bullying and harassment. While the literature has historically focused on sexual IV with coaches as perpetrators and athletes as victims/survivors (Bjørnseth and Szabo Citation2018), other individuals such as parents/guardians, participants/athletes, sports scientists and allied health staff can also be perpetrators of any form of IV in sport (Fasting, Brackenridge, and Sundgot-Borgen Citation2003). In addition to IV occurring at a micro/relational level (Raakman, Dorsch, and Rhind Citation2010), it is important to also acknowledge the role of organizational tolerance in experiences of IV in sport. Roberts, Sojo, and Grant (Citation2020) cited this tolerance as a necessary condition for all forms of IV to occur within sport organisations. Indeed, both individuals and organisations have a role to play in protecting children from IV. In that regard, sport organisations are developing and implementing safeguarding sport policies and practices to ‘assure athletes’ safety and human rights’ (Kerr and Stirling Citation2019, p. 372). In addition to preventative actions, safeguarding also encompasses responsive ones when policies are breached. Responsive actions to experiences of IV in sport holistically rely upon victims/survivors, and/or those who they disclose their experiences to, to both recognise the IV and lodge an official report (Komaki and Tuakli-Wosornu Citation2021). In the case of a community sport club, it would, for example, require a child to talk about their experience to a parent, and for that parent/child to report the event to the management of the club, who would then enact the policy.

Defining ‘disclosure’ can be problematic as the literature often lacks clarity on whether it refers to telling someone about IV or making an official report. Herein we draw that explicit distinction and focus on the child telling an adult about their experience of IV, irrespective of this resulting in an official report. While many policies assume that disclosures are a discreet event, we ascribe to the iterative and dialogical nature of disclosures, recognising disclosures are the result of complex interactions between the child, the adult and their environment, over time (Alaggia Citation2005; Alaggia, Collin-Vézina, and Lateef Citation2019; Gillard et al. Citation2022). McElvaney, Greene, and Hogan (Citation2012) frame the barriers to disclosure as being akin to a ‘pressure cooker effect’ whereby the disclosure is impacted by a constant battle between wanting to tell, but not wanting to, and the emotional pressure of this juxtaposition slowly building up prior to an initial disclosure. However, these framings of disclosures have predominantly focused on child sexual abuse disclosures, with very few studies situated in the sporting context. Herein we will apply this framing of disclosures as an iterative process within both the interview guide as well as the data analysis, recognising at each stage the importance of the interactions between the child and adult being disclosed to and the reflections of the child and how these impact subsequent disclosures (over time) and actions.

From a scientific standpoint, little is known about the process of disclosing an experience of IV in sport, especially from the viewpoint of the child victim/survivor. As the literature focuses mainly on sexual IV, disclosures of other forms of IV experienced by children in sport are not well understood (Bjørnseth and Szabo Citation2018). Understanding disclosures of all forms of IV in sport, both in terms of frequency and process between the child and adults, is critical to inform and advance safeguarding practices and research (Brackenridge Citation2002; Gillard et al. Citation2022). Moreover, while it is clear that supportive responses to disclosures of childhood IV can positively impact the discloser’s longer term wellbeing, there is a need to understand/explore how disclosures and disclosure responses occur in practice (Solstad Citation2019; Ullman Citation2003). The aims of this mixed-methods study were to: 1/identify the frequencies of disclosures of childhood IV in sport and to which adult disclosures were most frequently made, and 2/to explore how disclosures of any form of IV occur in order to increase our understanding of and to inform future safeguarding policy and practice in community sport.

Methodology

As researchers in the field of safe sport, we were motivated to increase understanding of the disclosure process as a way to reflect more deeply on the current safeguarding practices and how they do or do not offer a safe space for people to share their experiences in sport. Our research is underpinned by a transformative axiology that focuses on the enhancement of social justice and human rights, and a respect for cultural norms (Mertens Citation2010). This transformative belief system directly informed our methodological decisions about appropriate ways to gather, analyze, and report data about the disclosure process in such a way that we have confidence that we have captured and ‘represented’ the realities of those with lived experience of IV in an ethical manner, and with the potential to lead to the furtherance of social justice.

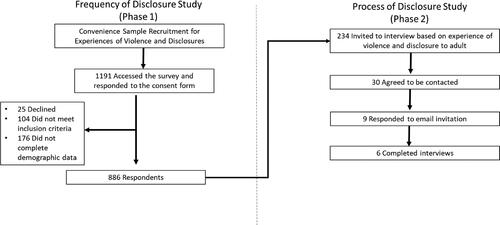

This research employed a two-phase mixed methods research design () and a retrospective lens. The study was approved by the Victoria University Human Research Ethics Committee [HRE20-150]. The research was part of a larger study that explored experiences of IV during childhood participation in community sport in Australia (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023). A mixed-methods design was selected for this project in order to generate, and bring together, both quantitative evidence on the frequency of disclosures of any type of IV during childhood sport participation and qualitative evidence of the experience of disclosing to an adult. The focus on disclosures to adults was selected because of the adults’ assumed ability and responsibility to take action. The complementary nature of the methods provided a more complete and comprehensive insight into the phenomena of disclosing IV in sport (Sparkes Citation2015).

The current study analysed disclosure-focused data that was captured within that first survey, as well as subsequent interviews with individuals willing to speak about their experience of disclosing IV. Importantly, the focus was on child disclosures to adults. This was an explicit decision by the authors in recognition that while peers (other children) could receive disclosures, it is adults who are ultimately expected to have the ability/capability to take further action. The study involved a sequential approach () where the quantitative (survey) method (Phase 1) preceded the qualitative (interviews) method (Phase 2). Phase 1 informed the sample of the qualitative phase to maintain a single, integrated mixed-methods study (van der Roest, Spaaij, and van Bottenburg Citation2015). Phase 1 collected data on frequencies of disclosures to adults for any type of IV experienced during childhood sport participation, while Phase 2 focused on the experience of the disclosure process through semi-structured interviews with a subset of Phase 1 respondents.

Phase 1: Frequencies of Disclosure

Participant characteristics and selection

The frequencies of disclosure data were collected as part of the retrospective magnitude of IV study previously published (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023). A total of 886 survey respondents completed the study: 63.3% women, 34.8% men and 1.9% gender diverse individuals. 13.3% of respondents indicated they had a disability and 2% identified as being Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin. Respondents represented all states and territories of Australia and 18% of participants were aged 18–25 years. As noted in the previous manuscript (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023), 82% of respondents reported at least one experience of IV: 76% psychological/neglect, 66% physical, 38% sexual (inclusive of sexual harassment and sexual violence, with and without contact).

The survey instrument

Experiences of IV and disclosures of it were identified through responses to the Violence Towards Athletes Questionnaire (VTAQ) (Parent et al. Citation2019), which assesses psychological, physical, and sexual violence experienced by children in sport. The survey has undergone initial factor validation and includes four sections of questions about IV, delineated by perpetrator (peer, coach, and two on parents) (Parent et al. Citation2019). For purposes of capturing frequencies of disclosures to adults, a question was added after each of the four sections (peer, coach and two sections on parent violence asking participants if they disclosed that experience to an adult (over the age of 18 years). The question was framed in such a way as to ask participants if they spoke to an adult about any of the experiences that they indicated within each survey grouping (grouped by perpetrator as described previously). This framing aligns with our understanding of disclosures being an iterative process rather than a single discreet disclosure. There was no time frame for the speaking to an adult, aside from it having occurred when they were still classed as a child (under the age of 18 years). This question was only visible to individuals who indicated that they had experienced a form of IV from that type of perpetrator. If participants indicated they disclosed the experience to an adult, they were asked to indicate who the adult(s) they disclosed to were via a multiple response question.

Statistical analysis

Three sets of analyses were conducted: one for each category of perpetrator. In each case three frequency analyses were conducted: frequencies of experiencing IV (yes/no), frequencies of disclosing the IV to an adult (yes/no), and multiple-response frequencies of who the IV was disclosed to (yes/no for each category of adults disclosed to). For each frequency analysis, corresponding chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate were conducted to investigate differences between genders. Significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 27.

Phase 2: Interviews on the Disclosure process

Participant characteristics and selection

A total of 234 participants from Phase 1 were invited to participate in an interview based on having experienced a form of violence and indicating they had disclosed their experience to an adult. Thirty individuals agreed to be contacted by email with study details, of which nine responded to the invitation, and six individuals completed the interviews. Interviewees ranged in age between 20 and 50 years old and had participated in six different sports as a child. There was one man, four women and one individual who was gender diverse. Participants had experienced a range of different types of violence (physical, psychological and sexual [harassment]) and all indicated having experienced at least one form of IV from each perpetrator (peers, coaches and parents), with the exception of one interviewee who had not experienced IV from a parent.

Procedure and analysis

The interview followed a semi-structured guide in order to understand more deeply the experience of disclosing IV to an adult. This approach was deemed appropriate due to the sensitive nature of the topic and to allow the interviewer and interviewee to engage with the broad themes in an open and free-flowing manner. The guide was pragmatic in nature as it focused on the interaction points during the disclosure process and how the interactions between the child-victim/survivor and adults influenced this process (Alaggia, Collin-Vézina, and Lateef Citation2019). The interaction points (and thus interview questions) included motivations/influences for disclosure, the disclosure itself (recognising that many individuals have multiple disclosures), and the interactional impact of that disclosure. We further asked questions around the outcomes from the disclosure (either personal outcomes, changes in familial dynamics or changes at their sport club). To safeguard interviewees, the researcher often checked in with the interviewee to ensure they were okay to continue or if they required a break. Each interview concluded with a participant check in about how they were feeling, and a reminder of the available support resources which included contact details of government support agencies as well as a clinical support for the study participants specifically (a clinically trained psychologist external to the investigator team). The participants were also invited to contact the researcher conducting the interviews if they had any additional questions, concerns they wanted to discuss or to debrief if they needed to.

One researcher conducted all six interviews, with interviews lasting between 25 and 75 min. The interviews were conducted using the Zoom online meeting platform and participants were given the option of having their camera on or off. Audio only recordings were captured of the interview and the Otter Ai platform was utilised to assist with transcription. The analysis of the interview data was conducted according to the reflexive thematic analysis techniques described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). Multiple researchers were involved in the interpretation of the data. The researcher conducting the interviews recorded notes during the interview process as well as post-interview reflections. All transcripts were then reviewed to ensure transcriptions were written verbatim. Another researcher then reviewed all transcripts and conducted semantic coding.

The analytical process involved immersion in the data, as well as reflective questioning on both an individual and collaborative level. As Patterson, Backhouse, and Jones (Citation2023) note, this is not a quick process and required periods of reflection and ‘sitting with the data’ in order to make sense of the findings. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) approach to reflexive thematic analysis places an emphasis on the importance of our subjectivity as researchers as an analytic resource through a process of reflexive engagement between theory, data, and our interpretation of it.

The first author read and coded passages of text in an open manner (initial meaning coding), and subsequently categorised the open codes into sub themes. As an example, the quote ‘So what helped me talking to my parents, is family is very big to me, because my mom is from a Pacific Islander background, so family has always been a massive part of my life’, was initially coded as strong parental bond, and ultimately was situated within the subtheme of Relationship with trusted adults (which included both facilitators and barriers to disclosing based on relationship dynamics). Thus, the first author drafted sections of texts with indicative quotes for the selected themes and requested feedback on codes and subthemes (nomenclature and understanding) from authors before the themes were finalised.

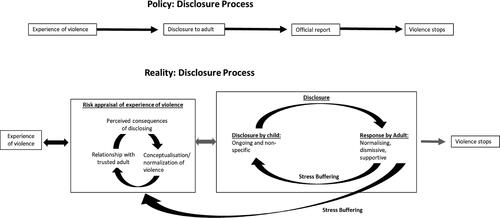

Major themes were framed to align with critical points where cyclical patterns of individual and interactional processing occurred: individual risk appraisal and the disclosure interaction. Within these themes, moments of individual and interpersonal interpretations, expectations, and interactions that influenced the disclosures process were identified and categorized. ‘Critical friends’ within the research team were also instrumental throughout the analysis process. Throughout the analysis process author(s) Woessner, Pankowiak and Kavanagh] discussed the transcripts and initial interpretations. Early versions of the thematic structure and the derived disclosure process diagram () were presented at conferences to gain feedback and refine this representation of the data. This challenged us to justify and clarify the interpretations that we developed and ensure our analysis of the patterns of shared meaning amongst the participants were underpinned by a central organising concept.

Results

Phase 1: Frequencies of disclosures

Of those who had experienced any IV in sport as children, less than half (46%) ever disclosed any of their experiences to any adult. Individuals who experienced peer and coach perpetrated IV had the highest disclosure frequencies of those experiences (35% and 27%, respectively) and those who experienced IV from a parent had the lowest (13%) (). For peer perpetrated IV, men had significantly lower rates of disclosure (28%) than women (38%).

Table 1. Disclosure of childhood IV experienced from different perpetrators: by participants’ gender.

Participants reported that they had most frequently disclosed their experiences of IV to their parent (or their other parent, in the case of parental violence) (). Men reported significantly lower rates of disclosure of IV to parents when they had experienced peer violence (77%), as opposed to women (93%). Regardless of perpetrator, the second most frequent adult that the boys disclosed to was their coach (or another coach, in the case of coach violence) or sport club manager. For girls the rate of disclosing to a coach in the case of either peer violence (39.1%) or parent violence (8%) was significantly lower than for boys (59% and 50% respectively).

Table 2. Who children disclosed experiences of violence to: by perpetrator and respondents’ gender.

Phase 2: Disclosure dynamics Results

The thematic analysis of the interview transcripts led to the development of two overarching themes. One theme focused on the child’s internalised contemplation of talking to an adult about their experience of IV before they disclosed. The second theme focused on the external process of disclosure to and interaction with an adult. Within the internal processing phase, there was an identified risk appraisal by the child, whereby they weighed up their relationships with adults, the consequences of disclosing and the severity of their experience to decide whether or not to disclose. The external process, or disclosure interaction, was conceptualised first as how the child perceived their disclosure experience and second how the adult responded to the disclosure. An additional finding is the contributory role of normalisation of violence in sport in the cyclical process of disclosures of violence.

Risk appraisal of talking about the IV to an adult

Following an experience of violence, participants assessed several factors to decide whether or not to talk to an adult about the violence they experienced, including: 1/the relationship with and anticipated response of the adult; 2/the benefits/consequences of disclosing; 3/their interpretation of the experiences of violence.

Relationship with trusted adults

Many participants shared that their relationship with and anticipated reaction of the adult was a key factor in their decision of whether or not to disclose their experience of IV. For the interviewees, the parent(s) were the primary adults that participants disclosed to and, in some instances, the sports coach. When reflecting on disclosing to parents, it was evident that children’s sense of certainty in how supportive the adult would be in responding to them had an impact on whether or not they disclosed. For example, one of the participants noted that her trusting, ‘best friend’ dynamic with her mother meant that she felt able to share her negative experiences in sport. Another participant indicated that because her ‘parents had such a big interest in [her] sport’ (e.g. driving to sport, attending trainings) that she was assured she could tell them about negative experiences: ‘I just felt like I could tell them about those things’-Alice.

In contrast, the perception of a negative family dynamic created barriers to coming forward to disclose. For example, for Luna, her perception of how her disclosure might be received based on a previous negative interaction with a parent when sharing an emotional experience (e.g. dismissive or unsupportive response) influenced her ‘I probably didn’t divulge too much, because I knew I wasn’t going to receive the proper support that I was probably yearning for’. -Luna.

When adults (parent or coach) were the perpetrator of IV, participants noted that it was challenging to talk about those experiences:

…at a young age, it’s hard because my parents and my coach, I saw them with a lot of respect. And I gave them a lot of authority. So, it’s hard to address dissatisfaction about people that you also view as like an authority figure in your life, and as someone that you respect. -Ruby

Overall, the perception of adults’ support, beliefs about how that support would be enacted, and the pereceived difficulty of disclosing to an adult influenced the child’s decision to talk [or not] about the IV. This appraisal was then combined with the child’s perception of the potential consequences of making a disclosure.

Perceived outcomes: fear of losing everything

Participants shared that part of their fear of speaking up related to the potential consequences either to themselves, or to the perpetrator. One individual shared:

I didn’t want them [parents] to withdraw me from sport altogether, because sports always been everything in my life, it truly has. So, I suppose there was a fear of losing that. -Matthew

I wanted to be able to, you know, wake up on a Sunday morning and hop in the car and go play game of soccer or go play a game of rugby without worrying about if someone was going to try and hurt me or you know, and just have fun? I think that was the biggest thing, I just wanted it to go back to the way it was. -Matthew

Beyond individual consequences, participants also battled with the consequences others might experience if they were to speak up. They noted that this was influenced by educational values and beliefs and their desire to be better to others than others were to them.

… I was always raised [that]if you don’t have anything bad to say, say nothing at all, even if it’s the truth. So, I sort of battled definitely internally with that…I didn’t want to do to someone’s reputation, or their character what people were doing to me… I wanted to try and take the moral high road whenever I could, but the moral high road gets you nowhere.- Matthew

These fears of destroying people’s character with accusations of violence were an influencing factor for those children who chose to disclose or not to specific adults.

Individual recognition and environmental normalisation of IV

Many of the participants reflected on how a broader normalisation of the behaviours or their lack of knowledge around the diverse types of IV in sport led to them not disclosing. One participant shared that they would compare their own experiences in sport against what they perceived their peers experienced. For them, if it happened to everyone and everyone stayed silent, they should stay silent as well. Matthew said that some of the bullying behaviours were so widespread that ‘…it’s [violence] a cultural thing in the sport. And so you just learn to live with it, ignore it’. -Matthew

While some elements of how normalisation occurred were challenging for participants to pinpoint, one participant shared explicitly how physical violence was actively normalised. Alice said:

So when I was probably 16, or 17, I had a coach who would throw like equipment out of like frustration, so he had a clipboard… and he would like stand up and throw it on the ground or like break it and slap it around…he kind of introduced himself saying that that was how he behaved and that it was almost like he thought it was acceptable behaviour at like junior level sport.

Not being able to recognise IV, particularly when experienced from parents, could also contribute to the low disclosure rates of parent perpetrated violence. However, one participant shared that while they understood they experienced IV, they would only disclose to an adult ‘in the most extreme circumstances’ and that there were ‘a lot of things I didn’t disclose to them’. -Matthew. This speaks to the need to educate all stakeholders on both the existence and impact of all forms of IV in sport and support disclosures of all experiences.

The disclosure interaction

The disclosure process was described in two stages: the child’s experience of their disclosure and the perceived response from the adult. Participants viewed their experience of telling adults about the IV they experience as less of a discrete timepoint and more as a cyclical series of interactions between them and the adult. In this iterative process, the children shared their experience of violence (non-specific) with adults (typically parents), whose response was most commonly either normalising the child’s experience, reiterating the child’s individual responsibility to manage it (‘suck it up’, ‘toughen up’), or, more rarely, advocating for the child by driving the disclosure forward (to a formal report, further conversations with the club etc).

How children disclosed their experience of IV

Participants frequently described the disclosure of violence as occurring during continual conversations with adults. One participant noted that it was an ‘ongoing discussion pretty much from the moment I started in the sport about bullying, to the moment that I finished. Like, it was ongoing, like multiple times’. -Ruby. However, many participants did not conceptualise their experience of talking about violence as a disclosure of violence, but rather as a series of casual discussions about their broad experience in sport, as illustrated by Chloe ‘…I didn’t know I was disclosing… I just thought I was reiterating what happened during the day… But I think because it wasn’t serious in my mind… Yeah. I may have lessened the blow, maybe…’ Similarly, Luna explained that when she spoke to her parents about the experience of violence ‘It wasn’t like I went seeking help. I went and talked about it in the sense of this happened, this happened, now I’m here’. Disclosures of any type of violence tended to broadly be non-specific and often children do not explicitly name the intent of the conversation as help seeking or needing support.

Normalising of violence from the adult

Despite participants indicating they trusted adults and were motivated to speak to their parents, or even a coach about their experience of violence, adults’ responses frequently normalised the violent behaviour or overall experience. The normalisation was not uniform for all types of violence, with several participants noting that their parents or coaches would normalise some forms (physical violence from a coach) while calling out others (peers ignoring or excluding children), as illustrated by Alice:

…their [the parents’] perception was that the coach was being unfair when, like, the girls were kind of excluding some of us and, but their perception of the coach like throwing the clipboard or throwing equipment around and getting angry wasn’t like, they weren’t that worried about it. – Alice

Dismissing children’s experiences

The majority of participants shared that their disclosures to parents or a coach were often dismissed, disbelieved or diminished with the adult pushing the child to take responsibility for themselves and be ‘resilient’. We categorised this as being distinct from normalisation, though there are clear links between the behaviours. Dismissive behaviour could occur without normalisation, and normalisation of the behaviours could occur without dismissive behaviours. For example, Ruby shared that the dismissive response from their parents relates, in some ways, back to how their parents respond to other situations: ‘it was just like, my parents are very direct people. So, it was more so like, sorry that you’re experiencing this, but time to just be resilient. Like, just don’t think about it’. In some cases, it was clear that the interviewee was classifying how bad the experience was based on the adults’ reaction to their disclosure. One shared: ‘…especially my soccer coach, I used to tell him things even if they were just little things [psychological violence], and he just basically told me to suck it up and get over it’. -Matthew. Matthew further shared that the coach they disclosed to evaded the responsibility of managing their experience of IV, indicating that it’s not a coach’s role to support children in their experiences of violence. Matthew said: ‘he’s [the coach] like, ‘I’m not here to be a counsellor, I’m here to coach you, and that has nothing to do with [named sport], so I’m not interested sort of thing’ ‘.-Matthew. These types of dismissals left the children feeling invalidated and not believed and, in some instances, at fault for the violence. In cases of overtraining and forcing to play while injured, these dismissals were particularly normalised. One participant shared:

And when I told people about my shoulder [injury] … No one gave a shit. They’re like, ‘well, obviously, you didn’t stretch properly. Obviously, you didn’t do this’. So, it was all my fault…. nothing I’ve ever said to anyone ever got taken seriously in anyway. And by taking seriously, I mean, even taken at face value. …That was actually the first time I remember saying ‘I’m hurting’, and someone said, ‘get over it’. And so, whenever I was in pain, I stopped saying anything. I didn’t say anything to anyone, even my Mum, I didn’t say anything. – Chloe

As identified in Phase 1’s survey, parents were the most frequent adult that children disclosed to and often this meant an initial dismissive response played heavily into the child’s decision to disclose again (either to them or any other adult): ‘…, they [parents] were basically the only people that I felt I could talk to. And because I got no traction with them, I just accepted that that was the way it was going to be and had to put up with it’. -Avery

Similar thoughts were shared about disclosing experiences of violence to coaches. One participant noted that though they expected to be able to speak to the coach due to the close familial relationship, the ultimately dismissive response silenced them from speaking to anyone outside of their parents.

As far as with [violence by] my coach, I felt as though because he’d been a family friend for so long that I would’ve have been able to talk to him. So, it was very hard when I got those [dismissive] reactions…So that sort of let me down, and so like, well, what’s the point of talking to anyone out there other than like my mom and dad, what’s the point? -Matthew

The data demonstrates that the initial response to any disclosure is critical. When an individual manages to share their experience, the reaction of the person they have confided in matters. Our participants often felt dismissed and not believed and this negatively impacted not only their future appraisals of experiences of violence but also led them to question their willingness to disclose in the future.

Supportive response and sometimes action-oriented

A few participants shared that in some instances the adult they disclosed to had a supportive response, wherein they expressed that they believed the child. While in some instances the response from the adult included them supporting the child in taking an action, more frequently the response was focused on reassuring the child that they were believed, but then either suggesting they ignore it or confront it themselves. The supportive response, regardless of future actions taken, seemed to provide some relief to the child in that moment and opened the door for them to be able to disclose further: ‘… [the disclosure] was kind of met with an ‘oh yeah, the behaviour is inappropriate’ from the people that were doing it. So, I think maybe the understanding that, that my reaction wasn’t an overreaction definitely helped me talk about it’. – Luna

While the supportive response was helpful initially, the perceived recommendation from parents that the child take action themselves (e.g. talk to their coach about their experience of violence), was not deemed helpful. Participants mentioned that this type of response silenced them further as they did not independently feel able to progress their concerns. There were a few examples where supportive responses by adults to disclosures of violence were followed up with actions from the adult to address the violence. A participant shared an experience of having a parent contact the club about psychological violence from a coach, but they never heard back from the club.

… she [the mother] sent an email to the club. [She] said ‘this happened, I want an apology to my daughter and to me and this is unacceptable’…But as far as I know we never got a response. Never got an apology…But she didn’t actually follow up on matter after the email, ‘she was like it is not going to do anything. What are you gonna do?’- Chloe

There were a couple instances where actions by the parent were followed by changes. In one case, a parent who also held a position within the sport club disclosed their child’s experience of violence (peer and coach, psychological and physical IV).

Yeah, Dad spoke because he used to be part of the soccer club, he was treasurer, so he spoke to them and they’re sort of like an old boys club, didn’t really showed interest, but then Dad sort of went over top of like, everyone, and went to the Association and basically went to that entire board of the soccer club being removed from their position. -Matthew

Another shared that her parents and coach took actions in response to peer bullying, causing other parents to reach out and agree there was ‘a big problem with bullying in the culture of the sport…’ – Ruby. While these instances of parental action are a positive and supportive step, these responses were not the typical ones.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study is, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first to report frequencies and the dynamics of disclosures of all forms of childhood IV within the community level sporting context. Disclosures of childhood experiences of violence within and outside of sport are complex and fraught with challenges including, but not limited to managing individual barriers to disclosing and negotiating confusion around what constitutes violence and others. Yet, children’s disclosures are a pre-requisite for safeguarding response mechanisms to be enacted (e.g. complaint procedures in sport organisations) (Paine and Hansen Citation2002).

Most of our collective knowledge on childhood disclosures of IV has focused on sexual violence, with a limited few studies focused on child sexual IV in the sporting environment (Fontes and Plummer Citation2010; Gillard et al. Citation2022; Parent Citation2011). Our study extends previous work by examining the retrospective frequency and process of children telling adults about the psychological, physical and sexual IV experienced in sport.

presents both the sequential process of disclosures of IV often assumed in organisations’ policies, alongside the iterative and cyclical nature of the disclosure process uncovered within our analysis. This holistic conceptualisation of the findings speaks to critical cyclical junctures within the disclosure process that could be focal points for educational and behavioural interventions. Both phases of our mixed methods study speak to the internal risk-appraisal process as well as the disclosure interaction, offering key insights into the influencers of disclosure and the opportunities to intervene and break the cycle. Specifically, highlights the presence of normalisation across both the internal and interpersonal processes and the critical role of stress buffering (described below) within the disclosure interaction. Essentially, participants move from private attempts to cope with their experience to a disclosure or seeking formal support (primarily from a parent/caregiver).

A key finding in this research was that disclosing to parents and being met with support or actions that either rationalise or normalise the behaviour acts as a ‘stress buffer’ for children rather than an impetus for action (creating a cyclical experience of violence/disclosure/response). Stress buffering is when a perception of the availability of social support (in this instance, from an adult), enhances the individual’s (in this instance, the child’s) perceived ability to cope with the stressful situation (violence) (Cohen Citation2004). Within the context of a disclosure interaction, the child has moved from an internalised processing of the experience (risk-appraisal) to speaking to a social support (disclosure interaction), believing, to some extent, that they will receive support from the adult. However, the response from the adult in almost every instance in this study rationalised or normalised the IV, ultimately acting as a buffer to the child rather than an impetus for action. In this sense, even a supportive or empathetic response, that is not followed up with actions by the adult, in effect, placate the child initially but also halts the disclosure from moving to more formalised reporting processes. In this way, stress-buffering responses could be seen as acutely helpful in terms of meeting the immediate needs of the distressed child, but problematic in the long term due to not responding to, addressing or impacting the occurrences of IV.

Another key finding from this study is that fewer than half of participants had ever disclosed any of their experiences of IV in sport to any adult previously. This low disclosure rate of all types of violence in sport is similar to disclosure rates of child sexual abuse in any environment (Mohler-Kuo et al. Citation2014; Priebe and Svedin Citation2008). Importantly, challenges with disclosures of childhood experiences of IV are not limited to experiences of sexual violence. The qualitative analysis identified specific influencers of a disclosure that could explain these low disclosure rates including: the risk of negative consequences of disclosing, the child’s relationship with the adult and the extent to which the child conceptualised the experience as a form of IV. The perceived consequences of disclosure focused heavily on the potential loss of sport and the sport community. This is not dissimilar to sexual abuse disclosures in elite sport, where participants described the conundrum of speaking up as ‘double abuse’ because to speak up means to risk everything (Gillard et al. Citation2022). To see these fears also play out at the community sport level and with any type of violence against children is concerning, especially considering experiences of physical and psychological violence are more common than other forms (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023). The way in which children conceptualised their experience of IV was heavily influenced by the extent to which both the child and the parent/community normalised all forms of violence. In particular, Vertommen et al. (Citation2022) argue that ‘instrumental violence’, including bullying, belittling or neglect (excluding or ignoring the child) by any perpetrator is highly normalised within sport. At the elite level, a performance focused and win at all costs mentality is well-documented as an enabler of the normalisation of IV (Willson et al. Citation2022), however this finding at the community level of sport dispels the myth of a clear line separating community and high-performance sport.

The highest disclosure rates were for children who had experienced peer violence (35%), with decreasing rates of disclosure for coach violence (27%) and parent violence (13%). The lower disclosure rates for coach and parent perpetrated violence aligns with earlier literature from other environments (education and religious institutions) and is likely reflective of the position of authority and power of both the coach and parent (Brackenridge Citation1997; Hershkowitz, Horowitz, and Lamb Citation2005). Indeed, in elite sporting environments coaches are often viewed as ‘gatekeepers’ to success and to challenge their position would be risking your involvement/inclusion in sport and your community (Kerr Citation2022). This point was highlighted further within the themes of relationship with trusted adults and perceived outcomes, whereby childhood disclosures were more challenging when the trusted adult perpetrated the violence. Indeed, the child felt unable to question adults’ authority and feared being outcasted from sport entirely. The sporting environment, particularly at the community sport level in Australia, is further complicated by the dual roles many volunteer-parents hold within their sporting club (two-thirds of volunteers are parents), creating a web of interconnected relationships which can create barriers to disclosing (Sport Australia Citation2021). Though peer violence was disclosed most frequently, it is not clear that this higher rate of disclosure translates into more frequent formal reports. It is possible there are higher levels of normalisation when disclosing peer IV in sport as opposed to coach or parent IV, thus while children disclose it to an adult, no actions are taken to challenge the practice at an individual or organisational level. Disclosure of peer perpetrated IV in sport could be easier than disclosing adult perpetrated IV adult, but perhaps the ease of formal reporting is reversed. This is critical line of inquiry for future research and further highlights the importance of distinguishing disclosures from reports in both research and practice.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, parents of the child were overwhelmingly the most frequently chosen trusted adult to disclose experiences of violence to, regardless of the perpetrator of the violence. Other research has identified parents as key adult for disclosures of child sexual violence, particularly for younger children, with studies citing that parents receive somewhere around 40% of disclosures of child sexual violence (Paine and Hansen Citation2002). In our study, children’s relationship with their parents was an important part their self-assessment when deciding whether to disclose. Close relationship with parents enabled children to speak up, whereas poor family dynamics (e.g. avoidance of discussions of emotions) silenced them. While parents remained the most frequent adult disclosed to, even when the violence was parent-perpetrated, parent-perpetrated violence still had the lowest disclosure rate of all perpetrators, with only 13% of children disclosing parent violence to any adult. The coach was the second most frequent adult children disclosed to, but there were gendered differences, with fewer girls reporting either peer or parent perpetrated violence to a coach as compared to boys. These gendered differences are poorly understood but could support the development of targeted violence response initiatives. Finally, while survey respondents could only indicate disclosures to adults, other studies have demonstrated that peers are some of the most frequent receivers of disclosures of childhood violence (Priebe and Svedin Citation2008). We focused on adult recipients with the intention of understanding the full disclosure process, acknowledging that adults have a responsibility (and assumed ability) to act on these disclosures. However, more broadly these low disclosure rates to adults (exceedingly low rates to police or sport club managers) indicate that our current reliance on these proxy reporters could be misplaced or, at the very least, not fully optimised (Mohler-Kuo et al. Citation2014).

The disclosure interaction between the child and the adult, particularly the expected and actual response of the adult, was a significant point in children’s disclosure process. For most, this exchange was perceived to have a silencing effect on the child. Research outside sport has found similar trends, but has predominantly focused on sexual abuse (McElvaney Citation2015). While the majority of participants shared dismissive responses from their parents or coaches, even those who received empathetic responses often found themselves back in the violent environment. Herein we framed this interaction via the concept of stress buffering. The stress buffering hypothesis posits that social support protects individuals from the pathogenic consequences of a stressor exposure (Cohen Citation2004; Cohen and Wills Citation1985). The belief that support is available and or the activation of support (response from a trusted adult acknowledging the experience), is hypothesized to help redefine the potential threat of a situation, bolster the child’s perceived ability to cope, and/or alter the affective, physiological or behavioural response (Cohen Citation2004). Therefore, social support (response to disclosure from the adult) can moderate the relationship between stressful life events (violence) and outcomes (proceed with disclosure, ignore, and move on). The challenge herein is that, more often than not, the adult’s response is acting to rationalise and normalise the child’s experience of violence, which, while acting as a buffer for the child, also impedes any further action (by the child or adult). The normalisation or rationalisation by parents of the experiences of violence are not necessarily malicious or ill-intended. In fact, this type of response can provide some short-term relief to the child’s emotional wellbeing, but at the expense of further reassuring the child that their experience of violence is normal. Of note as well, though our interviews were with the victim/survivors, it would be remiss not to acknowledge how the individual parent’s (or other adult’s) prior experiences within sport may have influenced their response. Indeed, their own historical experiences of normalised IV, and even potentially their experiences of reporting/disclosing in sport could have impacted their response. Kerr and Stirling (Citation2012) explain how the parents witness or can be exposed to harmful coaching behaviours in the sport environment but act as silent bystanders to their children’s experiences of IV in sport. The findings here support this view. As the literature shows, not only is the athlete socialised into a sport culture, but parents and other well-meaning figures can also be subtly enculturated into that world and this has an impact on their beliefs of what is acceptable behaviour in sport (Parent and Fortier Citation2018).

It is important to interpret these conclusions in light of the strengths and limitations of the study. First, we acknowledge that the timing of the study is set amongst a backdrop of heightened attention on interpersonal violence in sporting spaces at all levels. In addition, we are cognisant of global movements such as #MeToo that have increased public awareness of sexual violence against women and men and could have, to some extent, reduced the stigma around anonymous reporting for both genders. Given that the study took place at this time this could have influenced the willingness of participants to share their experiences of reporting their retrospective accounts of disclosing IV. Second, the sample for the original study was a convenience sample of Australian community sport participants and is therefore not representative of the entire Australian population, and there could be distinct differences in other countries based on who is available to receive disclosures/reports. The convenience sample limitation was also noted in a previous publication (Pankowiak et al. Citation2023) though given the focus of this paper is on those that have experienced and disclosed violence, the lack of population-level representativeness is potentially less of a limitation for the current study. We further clearly stated that we were seeking people who had disclosed their experience to an adult, but it is possible that disclosures were also made to other peers (below the age of 18 years). The focus of this project was on an adult receiving the disclosure as the adult would have a responsbility/ability to take action, but future studies should consider the role of peer confidants and other children as disclosers. The study implemented a retrospective design, and thus participant responses need to be considered in relation to a potential recall bias and with the understanding that their responses (both in the surveys and interviews) could be informed by their emotional development, processing and life experiences as an adult. Finally, due to the way the survey was constructed, it was not possible nor intended in this study to break down disclosure rates per specific type of IV, but this would be an interesting line of inquiry for future projects.

Conclusion

There are a number of assumptions underpinning traditional disclosure and reporting pathways for victim/survivors of IV in sport and these often remain largely uncontested. Evidence from this mixed methods study indicates that there is an urgent need to revisit the current disclosure procedures to better align with the empirical evidence regarding how, when and to whom children may disclose experiences of violence in sport. In particular, education and prevention initiatives should target all stakeholders and explicitly name sport-specific examples of all forms of violence focusing on breaking down the normative culture of violence that exists. The demonstrated low rates of disclosures as well as the broad pattern of poor responses to disclosures likely influences the decision to make a formal report. Supporting both the child and adult through this process is critical. The disclosure process is notably impeded at both the level of contemplation of the child (heavily influenced by normalisation of violence) and by the response from a trusted adult (influenced also by normalisation of violence and enacted through stress buffering). Policies and practice should acknowledge these critical junctures and provide guidance to both children and adults (often parents) in how to engage in the disclosure interaction in a supportive, empathetic and action-oriented manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank all the participants who gave their time to be involved in this project. Without them, this work would not be possible. The authors also acknowledge Caroline Stansen, a research assistant who assisted with transcribing and checking the initial interview data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alaggia, R. 2005. “Disclosing the Trauma of Child Sexual Abuse: A Gender Analysis.” Journal of Loss and Trauma 10 (5): 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020500193895

- Alaggia, R. 2010. “An Ecological Analysis of Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure: Considerations for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.” J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19 (1): 32–39.

- Alaggia, R., D. Collin-Vézina, and R. Lateef. 2019. “Facilitators and Barriers to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) Disclosures: A Research Update (2000–2016).” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 20 (2): 260–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017697312

- Bjørnseth, I., and A. Szabo. 2018 “Sexual Violence against Children in Sports and Exercise: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 27 (4): 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1477222

- Brackenridge, C. 2002. Spoilsports: Understanding and Preventing Sexual Exploitation in Sport. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Brackenridge, C. H. 1997. “HE Owned Me Basically….” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 32 (2): 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269097032002001

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Cohen, S. 2004. “Social Relationships and Health.” American Psychologist 59 (8): 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

- Cohen, S., and T. A. Wills. 1985. “Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis.” Psychological Bulletin 98 (2): 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Fasting, K., C. Brackenridge, and J. Sundgot-Borgen. 2003. “Experiences of Sexual Harassment and Abuse among Norwegian Elite Female Athletes and Nonathletes.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 74 (1): 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609067

- Fontes, L. A., and C. Plummer. 2010. “Cultural Issues in Disclosures of Child Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 19 (5): 491–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2010.512520

- Gillard, A., E. St-Pierre, S. Radziszewski, and S. Parent. 2022. “Putting the Puzzle Back Together-A Narrative Case Study of an Athlete Who Survived Child Sexual Abuse in Sport.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 856957. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.856957

- Hartill, M., and M. Lang. 2018. “Reports of Child Protection and Safeguarding Concerns in Sport and Leisure Settings: An Analysis of English Local Authority Data between 2010 and 2015.” Leisure Studies 37 (5): 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1497076

- Hershkowitz, I., D. Horowitz, and M. E. Lamb. 2005. “Trends in Children’s Disclosure of Abuse in Israel: A National Study.” Child Abuse & Neglect 29 (11): 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.008

- Kerr, G. 2022. “Addressing Cultural Norms of Sport.” In Gender-Based Violence in Children’s Sport, 105–119. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Kerr, G., and A. Stirling. 2019. “Where is Safeguarding in Sport Psychology Research and Practice?” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 31 (4): 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1559255

- Kerr, G. A., and A. E. Stirling. 2012. “Parents’ Reflections on Their Child’s Experiences of Emotionally Abusive Coaching Practices.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 24 (2): 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.608413

- Komaki, J. L., and Y. A. Tuakli-Wosornu. 2021. “Using Carrots Not Sticks to Cultivate a Culture of Safeguarding in Sport [Opinion].” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3: 625410. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.625410

- McElvaney, R. 2015. “Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse: Delays, Non-Disclosure and Partial Disclosure. What the Research Tells Us and Implications for Practice.” Child Abuse Review 24 (3): 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2280

- McElvaney, R., S. Greene, and D. Hogan. 2012. “Containing the Secret of Child Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27 (6): 1155–1175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511424503

- Mertens, D. M. 2010. “Transformative Mixed Methods Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (6): 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364612

- Mohler-Kuo, M., M. A. Landolt, T. Maier, U. Meidert, V. Schönbucher, and U. Schnyder. 2014. “Child Sexual Abuse Revisited: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study among Swiss Adolescents.” Journal of Adolescent Health 54 (3): 304–311.e301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.020

- Mountjoy, M., C. Brackenridge, M. Arrington, C. Blauwet, A. Carska-Sheppard, K. Fasting, S. Kirby, et al. 2016. “International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement: Harassment and Abuse (Non-Accidental Violence) in Sport.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 50 (17): 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121

- Paine, M. L., and D. J. Hansen. 2002. “Factors Influencing Children to Self-Disclose Sexual Abuse.” Clinical Psychology Review 22 (2): 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00091-5

- Pankowiak, A., M. N. Woessner, S. Parent, T. Vertommen, R. Eime, R. Spaaij, J. Harvey, and A. G. Parker. 2023. “Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Violence against Children in Australian Community Sport: Frequency, Perpetrator, and Victim Characteristics.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38 (3-4): 4338–4365. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221114155

- Parent, S. 2011. “Disclosure of Sexual Abuse in Sport Organizations: A Case Study.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 20 (3): 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2011.573459

- Parent, S., and K. Fortier. 2018. “Comprehensive Overview of the Problem of Violence against Athletes in Sport.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 42 (4): 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518759448

- Parent, S., K. Fortier, M.-P. Vaillancourt-Morel, G. Lessard, C. Goulet, G. Demers, H. Paradis, and M. Hartill. 2019. “Development and Initial Factor Validation of the Violence toward Athletes Questionnaire (VTAQ) in a Sample of Young Athletes.” Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 42 (3): 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2019.1682262

- Parent, S., and M.-P. Vaillancourt-Morel. 2021. “Magnitude and Risk Factors for Interpersonal Violence Experienced by Canadian Teenagers in the Sport Context.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 45 (6): 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520973571

- Pascoe, M., A. Pankowiak, M. Woessner, C. L. Brockett, C. Hanlon, R. Spaaij, S. Robertson, F. McLachlan, and A. Parker. 2022. “Gender-Specific Psychosocial Stressors Influencing Mental Health among Women Elite and Semielite Athletes: A Narrative Review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 56 (23): 1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-105540

- Patterson, L. B., S. H. Backhouse, and B. Jones. 2023. “The Role of Athlete Support Personnel in Preventing Doping: A Qualitative Study of a Rugby Union Academy.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 15 (1): 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2086166

- Priebe, G., and C. G. Svedin. 2008. “ Child Sexual Abuse is Largely Hidden from the Adult Society: An Epidemiological Study of Adolescents’ Disclosures.” Child Abuse & Neglect 32 (12): 1095–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.04.001

- Raakman, E., K. Dorsch, and D. Rhind. 2010. “The Development of a Typology of Abusive Coaching Behaviours within Youth Sport.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 5 (4): 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.5.4.503

- Roberts, V., V. Sojo, and F. Grant. 2020. “Organisational Factors and Non-Accidental Violence in Sport: A Systematic Review.” Sport Management Review 23 (1): 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.03.001

- Ruggiero, K. J., D. W. Smith, R. F. Hanson, H. S. Resnick, B. E. Saunders, D. G. Kilpatrick, and C. L. Best. 2004. “Is Disclosure of Childhood Rape Associated with Mental Health Outcome? Results from the National Women’s Study.” Child Maltreatment 9 (1): 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559503260309

- Solstad, G. M. 2019. “Reporting Abuse in Sport: A Question of Power?” European Journal for Sport and Society 16 (3): 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2019.1655851

- Sparkes, A. C. 2015. “Developing Mixed Methods Research in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Critical Reflections on Five Points of Controversy.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 16: 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.014

- Sport Australia. 2021. Ausplay: A focus on volunteering in sport. https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1029487/AusPlay-Volunteering-in-Sport.pdf

- Stirling, A. E. 2009. “Definition and Constituents of Maltreatment in Sport: Establishing a Conceptual Framework for Research Practitioners.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 43 (14): 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433

- Ullman, S. E. 2003. “Social Reactions to Child Sexual Abuse Disclosures: A Critical Review.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 12 (1): 89–121. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v12n01_05

- van der Roest, J.-W., R. Spaaij, and M. van Bottenburg. 2015. “Mixed Methods in Emerging Academic Subdisciplines: The Case of Sport Management.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 9 (1): 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813508225

- Vertommen, T., M. Decuyper, S. Parent, A. Pankowiak, and M. N. Woessner. 2022. “Interpersonal Violence in Belgian Sport Today: Young Athletes Report.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (18): 11745. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/18/11745. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811745

- Vertommen, T., J. Kampen, N. Schipper-van Veldhoven, K. Uzieblo, and F. Van Den Eede. 2018. “Severe Interpersonal Violence against Children in Sport: Associated Mental Health Problems and Quality of Life in Adulthood.” Child Abuse & Neglect 76: 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.12.013

- Vertommen, T., N. Schipper-van Veldhoven, K. Wouters, J. K. Kampen, C. H. Brackenridge, D. J. A. Rhind, K. Neels, and F. Van Den Eede. 2016. “Interpersonal Violence against Children in Sport in The Netherlands and Belgium.” Child Abuse & Neglect 51: 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.006

- Willson, E., G. Kerr, A. Battaglia, and A. Stirling. 2022. “To Athletes’ Voices: National Team Athletes’ Perspectives on Advancing Safe Sport in Canada [Original Research].” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4: 840221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.840221