Abstract

The tradition of Swedish ice hockey as a masculine-dominated territory that encourages characteristics like roughness, aggressiveness, and to some extent violence has been hotly debated. Using historical articles from the Swedish Hockey magazine, and with a perspective combining hegemony with the social-ecological model of violence prevention, this study develops an interpretation of how masculinity traits and violence in Swedish ice hockey interconnect. The historical case provides findings for this interconnection, with meanings of masculinity and a competitive commitment as permeating threads. Triggered by individuals, but also connected to coaches’ encouragements, organizations’ endeavours, societal, and financial forces, the negotiations around playing styles and allowance levels have been permeated by ideals of masculinity; ideals that enforce the current hegemonic gender order. Ultimately, the article contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of sport violence as an issue that not only impacts or can be utilized by sport organizations and players/practitioners but also its broader societal implications.

Introduction

For many years, violence in and near sporting activities has been debated by scholars and practitioners alike (Robidoux Citation2002; Spaaij Citation2008). The issue seems to be of particular interest in sports where there is physical contact between participants (e.g. in boxing, rugby, ice hockey) and in the team, and in individual sports that are dominated and distinguished by men and masculinities (Dicarlo Citation2016; Gruneau and Whitson Citation1993; McKee and Reid Citation2020; Weaving and Roberts Citation2012; Weinstein, Smith, and Wiesenthal Citation1995). For example, since the early 1900s men’s ice hockey has been regarded as a harsh and tough game with frequent hard physical contact, checking, and even fighting between players. Often, club rivalry, local patriotism, and even national pride, have fuelled the intensity of matches and have been perceived as having masculinizing and identity-shaping importance (Lorenz Citation2015b; Lorenz and Osborne Citation2006).

With such characteristics in mind, it is hardly surprising that research has also shown how men in team sports are exposed to a greater risk of violence in various forms (see e.g. Taliaferro, Rienzo, and Donovan Citation2010). Writing from an even more critical perspective, Michael Messner argues that:

[I]n many of our most popular sports, the achievement of goals (scoring and winning) is predicated on the successful utilization of violence - that is, these are activities in which the human body is routinely turned into a weapon to be used against other bodies, resulting in pain, serious injury, and even death. (Messner Citation1990, 203)

However, not all researchers agree with Messner’s description of physically-oriented (combat) sports as containing violence, for example in terms of fighting (Channon and Matthews Citation2018). In short, the argument is that combat-oriented sports create a space that both allows and encourages actions that could be regarded as illegal and unwanted outside this space. Practitioners practice and prepare for a sport that includes referees who control and punish eventual rule violations. ‘Safety-thinking’ is thus key in these conditioned situations and, from a historical perspective, we can also see how cruel or deadly (or purer) violence has been modernized and rationalized (Guttmann Citation2004) through changes that contribute to the inadequacy of the term ‘violence’. The introduction of compulsory helmets (in Swedish ice hockey in 1963) is one such intervention that drastically reduced the number of deaths in the sport (Tegner and Lorentzon Citation1992).

Despite rationalizations, regulations, and saving sport from participants’ deaths, some scholars argue that: ‘…many actions in sport, while not violent per se, could be construed as violent in many ways and for many reasons. As such, in many instances within the sporting context, violence becomes normalized in sport’ (Mountjoy et al. Citation2015, 884). Although deadly violence has been drastically reduced in modern sports, a certain level of violence still seems to exist in some. Normalizations, rationalizations, restrictions, rules, and other interventions that aim to increase safety in sport thus blur the notion of violence as something ‘either-or’ and point to a need to understand violence as mixed, or even contradictory, and phenomena in the plural (Hearn et al. Citation2022). More specifically, it seems impossible to completely delete dimensions of violence in certain sports without changing them into unrecognizable and perhaps meaningless entities. Although Guttmann (Citation2004) does not explicitly link the modernization of sport to gender and identity, a key reason for maintaining a certain level of violence is due to its perceived gendering and identity-shaping components.

In this article, how violence in the ice hockey culture functions and its potential as a mediating and reproductive power is in focus. Using historical examples of Swedish ice hockey from the past, I explore the connections between what can be considered as a violent playing style, its associated encouragements, risks and injuries, and its perceived masculinizing capacities, with the overall aim of understanding a sport’s reproductive potential for stabilizing patriarchal configurations in society. In a nutshell, understanding the past can be crucial when analysing a contemporary social issue, as it can serve as a lens through which the present is viewed, thereby offering a broader context and insights that ultimately stimulate a more complex understanding of the issue (Hunt Citation2018, Tosh Citation2019). Conversely, the understanding of the present and decisions for the future are influenced by past experiences and knowledge.

This article also draws inspiration from critical studies on men and masculinities (especially the concept of ‘hegemony’) and a social-ecological understanding of violence. By empirically recognizing how narratives and negotiations around different forms of hard physical contact, fighting, injuries, and the overcoming of pain, which could be summarized under the broader term of sports-related violence, connect to the (de-)masculinizing dimensions of the sport, Swedish ice hockey and its patriarchy-contributing and challenging content is discussed. In this way, the article aims to contribute to a more comprehensive and critical understanding of ice hockey and sport violence that not only impacts or can be utilized by sports organizations and players/practitioners, but one that also reflects the broader societal implications. As far as can be ascertained, the literature on hegemony (and hegemonic masculinity) and social-ecological prevention has never been linked together theoretically and analytically. Sports-related violence and its consequences can create lifelong traumas, cause suffering for individuals and families, and from a purely economic standpoint, incur massive costs for society. Understanding these dimensions and their associated levels is therefore of the utmost importance.

To fulfil this aim, the theoretical departure points are described first and are followed by a review of previous research. The materials and analytical frame are then described. This methodology is applied to the historical case in the study’s findings. These sections then form the basis for the final discussion and conclusions.

Theoretical considerations: the masculinizing and multilayered content of sports-related violence

With a critical perspective on men and masculinities, Critical Studies on Men and Masculinities (CSMM) researchers have long shown how sporting cultures that encourage hard physical contact between combatants can contribute to hegemonic notions of men and masculinities (Flood Citation2008; Messner Citation1990, Citation1992). The term ‘hegemonic’ derives from Gramsci and captures a culturally accepted form of dominance that helps to sustain elite social groups in a dominant position and keep the lower classes as subordinates (Gramsci and Forgacs Citation2000). What Connell (Citation1983) and colleagues did was to gender this cultural force and identify how men demonstrating ‘hegemonic masculinity’ were promoted as dominant forces that simultaneously subordinated and marginalized other versions of masculinities and femininities (see, e.g. Connell Citation1987, Citation2000, Citation2005, Citation2008).

CSMM researchers thus tend to focus on social relations and cultural characteristics in specific situations, for example in order to identify how power works via masculinity ideals. Typical topics might be how camaraderie norms function, and how peers socialize in a team. Results show how the hegemonic notions in men’s teams generally build on heterosexuality norms, where anything associated with women/femininities is carefully addressed. Masculinity scholar Michael Flood is more straightforward and writes that:

Homosocial bonds are policed against the feminizing and homosexualizing influences of excessive heterosociality, achieving sex with women is a means to status among men, sex with women is a direct medium of male bonding, and men’s narratives of their sexual and gender relations are offered to male audiences in storytelling cultures generated in part by homosociality. (Flood Citation2008, 355)

It is important to take into account how sporting men’s socializing involves attitudes towards women/femininity and other men/masculinities. In the long-term, such factors help to create a hegemony that is dominated by men and certain masculinities (Hearn Citation2004). A comprehensive interpretation of what Messner and other CSMM researchers show is that the sports-related violence on the field that is encouraged by coaches, team members, and spectators has a stabilizing effect on the constructions of masculinity in certain sports (including relational ‘borders’ to femininity and homosexuality). This stability is not to be perceived as one-sided, but rather as a dynamic force that builds on the multi-dimensional content of these masculinity constructions and stretches from the individual to the structural, and from the past to the present (Connell Citation2005).

With inspiration from Gramsci’s concept of ‘hegemony’, Connell (Citation2005) develops an analysis of the cultural dimensions of power and how dependence and other non-physical forces can be as effective as physical forces in the upholding of certain conditions for how power is gendered and relationally distributed amongst men, women, and others. Personal life and experiences, together with relational and structural forces, thus interconnect in sometimes sophisticated ways, where masculinity ideals of the dominating hegemony constitute a real challenge to change (Howson Citation2006). This means, that ‘deleting’, ‘rationalizing’ or ‘changing’ the ways of embodying and expressing such masculinity ideals in sports like ice hockey will be questioned and resisted, and where eventual change could simply be an alternative way for the dominating hegemony to prevail (Demetriou Citation2001).

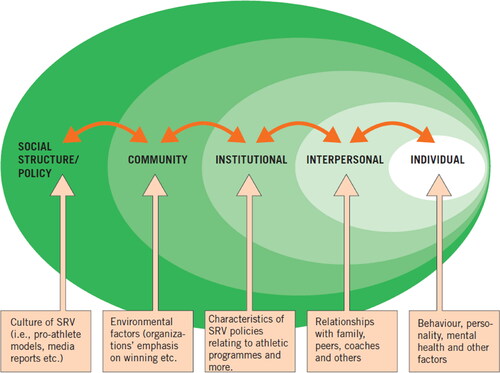

In an attempt to draw attention to how different types and the multi-levelness of interpersonal violence interconnect, Heise (Citation1998) developed a social-ecological model to conceptualize gender-based violence as a multifaceted phenomenon caused by the interplay between personal, situational, and sociocultural factors. The model has since been used in several academic disciplines by scholars of violence on and off the field (see, for example, Apatinga and Tenkorang Citation2021; Prego-Meleiro et al. Citation2020). One of the model’s strengths is that it shows the need to target several, if not all the factors or levels of effective violence-prevention interventions. What this means is that there is a connection between an individual’s need to dominate, a sense of peer pressure, the content of policies, organizational pressure to win, the media, the financial conditions, and other structural factors influencing sport (see ).

Figure 1. A social-ecological model of sports-related violence (cf. Fields, Collins, and Comstock Citation2007, 366 and Heise Citation1998).

The social-ecological model underlines and sorts the different sides of violence, which is important when approaching how masculinity ideals, the dominating hegemony, and interpersonal violence interconnect. At each level there is an upholding potential that is here understood as a hegemonic force, with men’s violence as the most explicit (and perhaps most desperate) expression. Connell (Citation2005) repeats that hegemonic masculinity operates from the personal to the structural, and by connecting this perspective to the social-ecological model each level’s negotiating and upholding potential is clarified. The CSMM field contributes with results from these levels and shows how being part of a community or a ‘gang’ affects the tendency to not speak up against peers (Corboz, Flood, and Dyson Citation2016), that athlete populations are more prone to violence than non-athlete populations (Sønderlund et al. Citation2014), and how male sporting cultures involving heterosexist gender norms tend to feed sexual violence against women (Flood Citation2008; Flood and Dyson Citation2007).

Another reason for a theoretical departure in a combined hegemony and social-ecological model is that this ‘double’ approach has the potential to understand all forms of violence more synthetically. Fields, Collins, and Comstock (Citation2007, p 360) argue that, ‘[b]y separating hazing, brawling, and foul play and failing to recognize that their connection to sport connects them, scholars fail to see how sports-related violence is a broad example of interpersonal violence’. According to Connell (Citation2005), violence (if regarded as necessary) is used by members of a privileged group to sustain dominance (through intimidation, harassment, verbal abuse, and so on). Most importantly, ‘[v]iolence can become a way of claiming or asserting masculinity in group struggles’ (Connell Citation2005, 83). When different individual violent actions are connected and gendered, they become examples of a broader entity, a hegemony, where interpersonal violence can sustain an upholding but also a reactionary, protesting potential. Instead of understanding these actions as isolated, their interconnectedness alters the understanding of them and the cultural hegemony and could, for example, put questions of organizational responsibility and (violence)prevention in a different light. In this context, Fields, Collins, and Comstock (Citation2007, pp. 366-7) point to the need for a more comprehensive approach to change:

Effective preventative interventions for sports-related violence will need to address not only individual factors, such as the need to dominate or the sense of belonging to a group, but also interpersonal factors such as peer pressure, coaches’ influence, and parental examples and expectations; institutional factors such as sports organizations’ and school legislation and referee enforcement of sporting rules; community factors such as the emphasis placed on winning and environmental designs of sporting venues; and social structure/policy factors such as the media’s and sports figures’ influence on the sports culture.

Previous research on ice hockey, hegemony, and masculinity ideals

Possibly due to its sporting and contextual characteristics, the ice hockey culture has been managed as an institution that is perceived as having a masculinizing effect on its participants (Gruneau and Whitson Citation1993; Lorenz Citation2015a; Stark Citation2010). Vaz (Citation1982). Gruneau and Whitson (Citation1993) and Robidoux (Citation2001) have highlighted the characteristics of and links between the ice hockey culture, professionalism, and the game’s violent ingredients. This explains the fascination for, the popularity of, and the capitalizing potential of the game. In line with Gramsci, Robidoux (Citation2001) shows how the dominating hegemony (embodied by rich, White company owners) can reproduce its hierarchical order via ice hockey’s cultural ideals. That is, the players’ sacrifices and abilities to expose themselves to pain serve the interests of the club (and capital) owners: ‘The player’s body, like a fine-tuned engine, is driven to exhaustion; once the body expires the player becomes superfluous’ (Robidoux Citation2001, 190).

Ice hockey, as a cultural sphere in the societal order, thus became a pawn in the shaping of a national, hegemonic power order. Lorenz (Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2015) and Lorenz and Osborne (Citation2006) have written several articles on ice hockey, masculinity, and violence from a historical perspective, while Allain (Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2019) has approached the topic from a more sociological, contemporary perspective, showing the complex construction of men/masculinity in hockey. In an anthology chapter, McKee and Reid (Citation2020) also show this complexity and how the violence prevalent in Canadian ice hockey was questioned during the late 1800s and early 1900s, where players could be considered as ideal Canadians but also as unmanly savages if they behaved violently in adequate or inadequate situations. In the Nordic region, Swedish researchers have mainly dominated the field, and here Stark’s Stark (Citation2001, Stark Citation2010) and Backman’s Backman (Citation2018) historical works are prominent. These historians have focused on the importance of ice hockey for shaping a Swedish national identity, and how the ‘Americanization’ or professionalization/commercialization of the game, with the National Hockey League (NHL) as a role model, was adapted by clubs and adjusted by the Swedish Ice Hockey Association to fit the traditions of Swedish ice hockey. It is no coincidence that this Americanization and commercialization of Swedish hockey accelerated after 1989/1991 with the collapse of the former Eastern European power bloc.

More comprehensively, the research on ice hockey, history, and masculinity can be summarized and placed in the social-ecological model. The logic of competition and its importance for the formation of masculinity ideals can be seen to permeate all the different levels. It is the desire to win among individuals, teams, clubs, and federations that motivates this masculinizing potential, and how it infuses the sporting system, informs its rules and regulations, and helps to legitimize, normalize, and justify the potential use of violence (in a broad sense of the term). Sports violence is defined here as fluid and used as a multilayered continuum that includes permitted, harsh physical actions, and impermissible or illegal behaviour. According to Messner (Citation1990, Citation1992), a player teaches his body to take a hit and use it as a weapon. In this way, ice hockey creates an institution for the potential use of normalized violence against oneself and others. Risk-taking and a high tolerance for hard physical contact (and its associated injuries) function as ways to popularize (and masculinize) the sport and is a vital cultural expression that in the long run helps to reproduce the dominating hegemony (Connell Citation2005; Robidoux Citation2001). In this way, the dominating hegemony, masculinizing ideals of ice hockey, and the function of violence in this culture permeate all levels of the social-ecological model, including the individual, organizational, and structural.

Material and method

This article builds on a broader project on Swedish ice hockey that began in 2019 and which encompasses a large amount of different data. This data has been analysed using various theoretical frameworks and published as separate articles. The study case reported on here is Swedish ice hockey between the 1970s and the 2000s. The main reference source is the Hockey magazine published by the Swedish Ice Hockey Association, which until the middle of the 1990s was the association’s official mouthpiece aimed at leaders, coaches, other governing positions, and club members in general. An issue typically starts with an introductory leader, usually written by the chairperson or secretary-general of the Association, highlighting debates or news regarded as important to communicate to people involved in Swedish hockey. This is followed by articles portraying players, leaders, or coaches, reports from games, clubs, or tournaments, statistics, articles about international hockey, etc. The magazine also contains educational, coach- and skill-related articles. It is thus an essential source for capturing the cultural content of Swedish ice hockey.

Based on the theoretical framework and the results of previous research, articles focusing on actions that could be regarded as violent and that have either a masculinizing or de-masculinizing trait were selected as data. When limiting the empirical data, it was important to find examples that could form links between the different levels of the social-ecological model and how these actions helped to stabilize or challenge the current hegemonic order. More specifically, as a first step a qualitative selection of examples was chosen that reflected the various individual, interpersonal, institutional, and structural levels, how they interlinked with each other, and the kinds of masculinity and violence they conveyed (cf. ). An analytical connection between these different levels was identified as a second step. Articles relating to individuals were analytically connected to those relating to insurance companies’ concerns about ice hockey and the number of reported concussions. The articles did not reference each other directly. The synthesis was facilitated by the theoretical framework and was situated in a contemporary context in order to understand sports violence today.

In the findings outlined below, such examples from the Swedish magazine Hockey explain how different cultural expressions and levels interlink with masculinizing and violent factors: a) the desire and commitment to win, b) the risk-taking and price of this commitment, c) the financial possibilities and costs related to this dedication, and d) the need for comprehensive and multidimensional management to change the game’s playing style. Taken together, the findings form the basis for a discussion about the stable, hegemonic conditions for changing the presence of violence in Swedish ice hockey – a discussion that should also be relevant for sporting contexts beyond Swedish ice hockey.

Findings: from individuals’ drives and dedication to organizations’ strategic and violence-preventive decisions

Historically, several sports, like rugby and ice hockey, were developed by men, for men, with the purpose of fostering ideal masculine citizens (Holt Citation2009; Lorenz Citation2015b). The so-called ‘father’ of Swedish sports, Swedish army officer and sports personality Viktor Balck, argued that the greatest sports competition of all was the war (Ljunggren Citation2020, 90). In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the implicit purpose of several sports was to prepare the participants for real-life combat situations (i.e. a war). Accompanied by values and ideals (obey the leader’s order, never give up, sacrifice yourself for the team’s best, and so on), and as young men were the primary target group, Balck and other leaders saw great potential in modern sports, especially since industrialization and the broader modernization of society were perceived as threats to citizens’ health, hygiene, and physical capabilities (Ljunggren Citation2020).

The desire to win – as violence against things, others and oneself

During the 1970s, the ice hockey players Stig and his now more famous brother Börje Salming were often portrayed in the Hockey magazine. Interestingly, Stig Salming was often portrayed as personifying the Swedish will to win by explaining this commitment as: ‘I get angry when I don’t succeed… Some people say that you should not bang the stick so hard on the ice so that it splinters and swear like a trooper. But I’ll say one thing: It makes you feel better!’ (Ericson Citation1976, 10). The Salming brothers were born in the north of Sweden and had a Sami background - an indigenous people living in the Arctic area of Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula. The quote reveals how a typical Swede usually kept frustration bottled up (like the former alpine skier Ingemar Stenmark). However, for Stig Salming, there was an absolute need to immediately reveal accumulated aggression. Although he did not advance to the NHL, Stig played in the national team for several years and was described by the national team coach as being ‘two guys in one - one on the ice, another outside the rink. Both are equally amazing!’ (Ericson Citation1976, 10).

The national team coach’s words referred to Stig’s aggressiveness on the ice and his calmness off it. Stig’s ability to switch his win-at-all-cost mentality on and off is a key to understanding his commitment and dual behaviour. Regarding the violent dimension, a short biographical note is necessary, because when Stig was 10 years of age (and Börje only six) the brothers’ father died in a mining accident. This meant that Stig had to take more responsibility at home (which was unusual for a 10-year-old boy), including the fostering of his little brother, and if Börje did not obey Stig’s words he was sometimes beaten. Around 1970, they both signed a contract with Brynäs IF and moved south to the town of Gävle, where the brothers played and trained together. According to one of the magazine’s articles, Börje sometimes paid back and fought wildly with Stig. These fights occurred during training sessions and were perceived as acceptable if they embodied a will to win; a commitment and winning mode that probably also influenced their teammates as well as their coaches. From 1970 to 1980 the club won six Swedish Championships (Stark Citation2010, Citation2017). As both brothers are described as calm and friendly outside the rink, ice hockey offered them situations in which they could ‘relieve’ accumulated frustration, aggression, and pressure.

The Salming brothers personified a (brutal) kind of altruism and team spirit with the motto to not worry about oneself but to instead bite the bullet, get up, and fight until the final whistle. For example, Stig was brutally knocked down from behind at the end of a World Championship game against the US in 1976. He passed out and damaged his knee, but in the next game was on his feet again to play. The norm was that there were always minor injuries, and for Stig this category included everything that was not a broken bone: ‘If you have the right attitude there’s no problem!’ (Ericson Citation1976, 11). It can also be noted that 20 years later, when Jonas Bergqvist was tackled from behind in his first game in the 1995 Ice Hockey World Championships, his ribs took a knocking but ‘only’ the softer parts were damaged (i.e. nothing was broken). Nevertheless, he stopped playing and sought medical advice (Hammarlund Citation1995, 13).

These two episodes indicate how ideals of safety and risk-taking can change and vary over time and place (or situation). What gave status or was expected of a committed player in the 1970s could be regarded as foolhardy in the 1990s (i.e. to continue playing in a tournament with a suspected concussion). It is tempting to interpret this as a general change over time, but it is rather the situation that is crucial in the shaping of masculinity ideals, not time per se (Connell Citation2005).

Most coaches sought the ‘Salming-type’ of person: a ‘strong, tough, rugged [player], who can pave the way for others and also sometimes score goals’ (Andersson Citation1997a, 10). Their role was to send signals of appropriate and ideal attitudes/commitment to the team. According to the Swedish national team manager in the mid-1970s, it was feared that these types of devoted players would leave or disappear altogether from Swedish ice hockey. The modern welfare state, with all its amenities, was seen as one of the biggest causes of this, and therefore represented a threat to the development of Swedish hockey (Ericson Citation1976). In other words, the increased welfare and its accompanying convenience risked reducing players’ propensity to expose themselves to risks, potential pain, and injuries (or violence). Regarding research on players’ dedication, Connell (Citation2005), Messner (Citation1990, Citation1992) and Young (Citation2012) (and several others) have made significant contributions by highlighting the ideal attitude of winning at any cost, sacrificing one’s body for the team’s best, and how these aspects contribute to the shaping of ideal, so-called hegemonic masculinities. But these authors rarely contextualize this attitude historically. It can hardly be over-emphasized that competitive commitment demonstrates how sports-related and sports-regulated violence has been legitimized, normalized, and perceived as something ‘natural’ and even fun, but also that this appears to be fluid over time. In other words, ice hockey and other sports offered and offer a relatively safe, ritual, fair, and rationalized form of violence (cf. Dunning and Maguire Citation1996).

The worries that ‘committed’ players would leave or disappear did not turn out to be justified, though. Young players continued to show similar qualities and commitment, and, like the Salming brothers, were willing to sacrifice themselves for the team and endure pain and beatings (Andersson Citation1992d; Hammarlund Citation1992a, Citation1992b). Despite - or thanks to - the serious injuries that could occur in a game, many sacrificing, altruistic players became extremely popular amongst spectators and the media (Andersson Citation1973, Citation1997b; see also Messner Citation1990). Coaches also managed to evoke these qualities in their players. Several names could be mentioned here, but one of the most ‘calamitous’ and injured players with this type of attitude was Tomas Sandström. Like Börje Salming, Sandström had a successful yet injury-filled NHL career. For example, in a game in 1992, Toronto’s Doug Gilmor slashed and broke Sandström’s forearm (Gilmor was fined 300.000 SEK and had his income reduced) (Andersson Citation1992c). Only a few games after his comeback, Sandström covered a slapshot with his face, which led to several damaged teeth and his jawbone broken in two places. Sandström had to have a steel frame fitted in his mouth and, as a result, could only consume liquid food for six weeks (Andersson Citation1993c). To paraphrase Messner, Sandström’s body functioned as a weapon and its ammunition affected other players and himself (Messner Citation1990).

How, then, could Sandström’s willingness to return to the ice be interpreted? First of all, he was under contract and there was an implicit readiness to use and endure pain and injuries, which in turn were fuelled by norms that almost enforced these ideals and behaviours. The players were also pieces in a larger financial power order. Robidoux, for instance, writes: ‘The hockey player is thus often associated with power because of the authority his body commands. But it is this same bodily authority which positions the player outside the dominant power relations.’ There were simply strong, hegemonic, and financial interests in the retention of these ideals. Players who were not prepared to make this sacrifice were considered ‘impotent’ (Hedberg Citation1993, 66). Epithets like this promoted and stabilized the sacrificing ethos. Although these ‘bold’ styles could cause concussion and other injuries, players were unwilling to change their playing styles (Elofsson Citation1993). The motto was: ‘Bruises vanish, points remain’ (Andersson Citation1995, 68).

Previous research has also shown that the ability to live up to the above expectancies generates respect, and that players who do not live up to these standards are perceived as disloyal or weak and are likely to be dropped or de-selected (Robidoux Citation2001; Vaz Citation1982). Bodily toughness was promoted as necessary for international achievements (Andersson Citation1993a). This became even clearer in the 1990s, when experts believed that the quality of Swedish junior hockey had diminished and therefore needed to change to allow and encourage more aggressive games. Hockey magazine expert Anders Hedberg, a former NHL player, argued that:

A tackle or forechecking must be allowed to be completed. Raise the ribbon of what is meant by aggressive play and violent tackling for our forthcoming elite juniors. Today, it is far too low. It is not possible to play an optimistic, energy-charged hockey if the person who tackles is always punished by being sent off. (Hedberg Citation1997, 33)

But the harder and more aggressive style of play sometimes came with a high price (Andersson Citation1993b). In contrast to Hedberg’s views of solutions, the fear of serious injury nurtured an opposition towards what was described already in the 1970s as escalating ice hockey violence (Nilsson Citation1976). However, a difficulty arose in identifying and defining whether the consequences were due to the culture and character of ice hockey or were simply individual accidents.

The price of commitment: concussions, injuries, and deaths

A dilemma arises between the players’, teams’, coaches’ and clubs’ will to win, and individuals’ (forced?) inclination to push themselves and play on, despite the pain or minor injuries. When it comes to playing after concussion, the consequences can be serious. Here, it is clear why physicians intervene and try to change the norms in ice hockey, but also how definitions of injuries change over time. As the above examples of Salming and Bergqvist indicate, players (and team physicians) have had different approaches to injuries and their treatments over time, and different investigations have also shown their different occurrences. An investigation in 1992, for example, showed that 36 out of 167 elite players (two goalkeepers, 11 defenders, and 23 forwards) suffered from concussion, with 25 of these having had more than one:

Ice hockey games carry many risks of injury due to the game’s speed and its close contact nature. The ice hockey stick, the hard puck, the unforgiving rink boards and the goal cages can all cause injuries. The injuries are many, although fortunately the majority are not very serious. Blows to the head entail great risks and in order to reduce the number of head injuries helmets became compulsory already in 1963. Prior to that, for a 10-year period (1951-60) Sweden experienced several ice hockey deaths due to head injuries, but after the introduction of the helmet no more deaths were recorded. However, to a significant extent, concussions still occur among ice hockey players. This is an alarming observation, especially as the number of concussions is apparently increasing. (Tegner and Lorentzon Citation1992, 65)

From a historical perspective, players’ safety increased considerably with the decision to make the wearing of helmets compulsory. This change of equipment rule must be understood as a key prevention of head injuries (and deaths). Regarding concussions, and as the physicians’ recommendations and critique were not acknowledged until the early 1990s, the results indicate a reluctance to drastically change the playing rules. With Robidoux’s Robidoux (Citation2001) findings in mind, such results reflect the view of players as exploited pawns in a larger, cultural, and financial game. What was then required for such changes to be initiated within Swedish hockey?

Concretized comprehensive critique: ice hockey as the most damaging of all sports

In the 1990s, there are several examples in the source material of friendly matches being stopped because all the players were fighting on the ice, youth matches being cancelled due to too many penalties and players (13–14 years of age), adult coaches fighting, coaches fighting (youth) players, and games being cancelled due to a team leaving in protest against the referee or opponents. Some coaches downplayed the seriousness of such events, arguing that fights and other ‘trifles’ were magnified by the local media. These episodes show that what can be hard to not consider as interpersonal types of violence was not perceived as particularly problematic by ice hockey representatives. The problem was rather that it received the wrong kind of attention in the media, and that by downplaying its problematic aspects it was somehow understood as ‘normal’ in some competitive situations (cf. Mountjoy et al. Citation2015). From a more critical perspective, the problem was not the ice hockey culture per se, but how the culture was presented by outsiders who did not understand it, i.e. these types of fights did not result in any changes being implemented.

From a less critical standpoint, fighting and concussions can be perceived as having vague and diffuse consequences, which could explain why they are downplayed (bruises, headaches, and dizziness are not the same as broken bones and can perhaps also be dealt with given the ‘right attitude’). In contrast, permanent marks for life, such as paralyzing injuries, were more obvious and, in that sense, easier to build an opinion around and trickier for the Ice Hockey Association to ignore. Players had suffered paralyzing injuries for many years, but it was not until the early 1990s that stories of players who had suffered terrible injuries began to be told in Sweden. Perhaps more importantly, the injuries were perceived as being caused by problems in the hockey culture itself (Andersson Citation1992b; see also Mauritzon Citation1993).

The narratives describe how the hockey culture could potentially paralyze a participant or could also function as salvation for an injured player. In 1993 alone, five Swedish players were paralyzed (Andersson Citation1992a; see also Fagerlund Citation1993). Investigations, organized by the sport movement’s leading insurance company, showed that ice hockey was the most damaging (in terms of being seriously injured) of all sports in Sweden at this time. Parents were reluctant to let their children play hockey and the number of dropouts steadily increased. All these factors led to pressure on the Swedish Ice Hockey Association to make the sport safer, and in 1994 preventive measures were initiated (Fagerlund Citation1994).

The inclination to take action (and responsibility) for change was influenced by and linked to factors or layers within, near, and outside the ice hockey culture. That is, both the social-ecological model and Gramsci’s understanding of cultural power as a hegemony help us to understand the conditions for change. Potential changes were debated, and some argued for smaller ice rinks (as in the NHL) so that the game’s pace would increase, become tougher with more physical contact, and be more fun for spectators to watch. Smaller rinks would also increase the players’ development capacities and mean that the game near the goal areas would be more intense, thus also creating a better development milieu for goalkeepers (Hedberg Citation1996). In contrast, others argued for keeping the bigger rinks, banning checks and physical contact (in children’s hockey), stricter and longer penalties, neck protection, the prohibition of checking from behind, blindside checking, and so on. The dilemma centred on the built-in risks in a more intense, faster, and closer game, which meant an increased risk of more paralysis injuries. However, this type of game and pace would also force players to develop their skills, which ultimately also meant that the players would become better prepared to avoid such situations (to some extent, this debate is still ongoing in Swedish ice hockey (TT Citation2022)).

Multi-dimensional management for increased player safety

Pressure was put on the Association to act, and a broad intervention was initiated. What stands out in this work is the comprehensive approach. After meetings with club and player representatives, the rules were changed and referees were encouraged to judge any game-destroying elements, which meant that a more or less zero tolerance for hooking, slashing, and interference was introduced. The decision also related to external pressure on the Swedish Ice Hockey Association (from the insurance sector) and the expectation to ‘show’ a preventative action that would ultimately make ice hockey a safer sport. Substantial preventative work was needed in each local club, where players should ideally learn the risks of careless and respectless playing styles (Fagerlund Citation1993).

A challenge in this change work was the coaches’ instructions and that referees’ allowance levels could (potentially) differ:

Our referees have namely a great responsibility as to whether we should produce any player profiles. If coaches are allowed to instruct their teams’ worst players to eliminate the opponents’ star players using unfair means, Swedish ice hockey will no longer have public idols and entertaining playmakers. (Wedin Citation1993, 23)

Discussion and conclusion

Delving into the historical roots of a particular problem has enabled us to trace the changes and identify the mechanisms, causes, and contributing factors that might otherwise have remained hidden. In line with Hunt (Citation2018) and Tosh (Citation2019), it enabled us to navigate today’s challenges with more precision.

The findings indicate the stability of the Swedish ice hockey culture and how masculinity ideals interconnect with winning commitment and coaches’ tactics, which in turn mirror people’s perceptions of how entertaining hockey is played and a developing ice hockey milieu is organized. Here, it is important to emphasize the multilayeredness of the will to win encompassing individual players’ triumph over bodily pain, how this is encouraged by coaches and peers so that it becomes a question of status, and how competitions are regarded as vital, both culturally and financially (Messner Citation1990, Citation1992; Messner, Dunbar, and Hunt Citation2000; Young Citation1993, Citation2012). The interconnectedness forms the basis of hockey’s cultural stability, where the questioning of certain masculinity ideals is labelled as ‘impotent’. A description like this exemplifies the cultural importance of the sport, since the content, according to Gramsci, can be understood as ‘an instrument’ that allows a dominating hegemony to reproduce itself (Gramsci and Forgacs Citation2000). This means, that the configurations of masculinity in the Swedish ice hockey culture interlink with a broader understanding of how a real man should tackle challenges and embody courage. Some of these traits are more long-lasting than others. Connell (Citation2005), Messner (Citation1990, Citation1992), and Young (Citation2012), for example, also identify the stability of the winning-at-any-cost-ideal. However, sports researchers seldom focus on how such strivings have several layers and contribute to a broader cultural hegemony.

The cultural hegemony ‘teaches’ coaches to dislike ice hockey players who appear fragile or impotent, and who play dull or funeral-like ice hockey. Although individuals embody winning ideals differently, it is important to see how ideals and anti-ideals are rooted in all the various layers of the ice hockey culture – from the individual to the structure, and beyond. That is, the will to win interconnects with the rules, the entertainment aspect of the game, coaches’ tactics, and how respect for teammates is shown. Challenging these ideals at an individual level requires a player to question some of the behaviour that is considered to earn them respect. The propensity to do so can be considered extremely low. Thus, any changes to this way of working and being need to be comprehensively organized at top management level.

Given that hegemony, according to Connell (Citation2005) and other scholars, builds on heteronormativity and demarcations against femininity, pure misogyny or homophobia is surprisingly rare in this historical case. Rather, it is the ‘danger’ of appearing funeral-like or unmanly (or impotent) that is displayed here, and how ideal masculinity is loaded with (sexual) activity. Instead, masculinization is created through the ability to endure pain, come back from severe injuries, and have enough courage to be exposed to violence - actions that the system as a whole has supported. This fostering into what was considered as good characters was threatened by the welfare institutions. Here it is important to emphasize how modernization and rationalization at a wider level were seen as threats to the traditional ideals of sport (cf. Guttmann Citation2004). In short, the increased ‘sportification’ created a safer yet ‘softer’ sport.

Connell (Citation2005), for instance, points to the stable yet situation-receptive elements of gender construction by arguing that sport competitions and commitments are economic, cultural, and symbolic tests of manhood, where boys and men are expected to show what they are made of. With such tests, sport can generate popular, problematic, and even deadly actions, but can also change over time. As Dunning and Maguire also contend, these tests are contested and never ‘natural’; a condition that embeds eventual changes into the rules, the use of equipment, safety gear, etc. The game’s inherent potential and risks also shed light on how sports-related violence can be understood as something that is both progressive and problematic. At best it is perceived as character-building, while at worst could cause severe injuries. Sports-related violence is not essentially negative but can create respect between men, be something playful yet in the next moment be paralyzing and sometimes even deadly. Implicitly, men’s bodies appear as vulnerable but with ideal commitment players also show how they overcome vulnerability and severe injuries. Here, the historical perspective indicates that perceptions of injuries and the need for rehabilitation vary over time.

The findings contribute to the current research field by revealing the changed perceptions and conditions for implementing violence prevention and increased player safety in a sports context. However, the outcome of the change will need to maintain the potential for ice hockey-playing men to continue to be perceived as masculine. The risk of death motivated the compulsory use of helmets, However, this change in the rules and the comprehensive rule changes during the 1990s were implemented without the dominating hegemony being disturbed. Despite internal criticism, the Swedish Ice Hockey Association chose to, and was under pressure to introduce stricter rules, harsher punishments against destructive play, and other actions that could cause serious injuries. The fact that insurance companies and occupational therapists pointed to the occurrence of injuries and the importance of rehabilitation may have made it easier for the changes to be implemented.

What, then, is the point of bringing together past accidents, paralyzing injuries, legitimate checking, fights on and off the ice, the will to win, and portraying ideal masculinity in an analysis that combines the social-ecological model with hegemony? The findings indicate the importance of analyzing and understanding ideals and actions beyond the individual level by pointing out how they promote a more general societal hegemony. Men are expected to be strong, willing to sacrifice their bodies, ignore pain and ‘minor’ injuries, be loyal, have fun, be focused on winning, and climb upwards in a hierarchy. From a broader perspective, this echoes findings from research on violence showing the connection between such masculinity ideals with a ‘devaluation of femininity or anything perceived as “non-masculine”’ (Waling Citation2019, 370). What is problematic here is that such ideals can trigger men’s violence against women (Flood Citation2008; Flood and Dyson Citation2007). This type of (misogynistic) devaluation and perception has been found in ice hockey by several scholars, both in Sweden and beyond (Allain Citation2014; Gruneau and Whitson Citation1993; Robidoux Citation2001; Weinstein, Smith, and Wiesenthal Citation1995). This article has simply indicated how such aspects are connected. More empirical evidence is, of course, needed to corroborate the findings.

Therefore, and to conclude, it is important to understand sport cultures in a critical way. Not least, more research is needed on how different types of violence are ‘copied’ or transferred, for example, from sports arenas to other societal arenas where they are not sanctioned. Here, the connections between encouraged masculinity ideals, views of women/femininity, unmanliness, and different types of violence seem to be of crucial importance. Such studies are motivated by the enormous costs caused by sport violence.

In several of their works, Messner and colleagues have developed a critical perspective on how sport promotes men and certain masculinity traits by arguing that in this way sport serves as a symbolic proof of men and masculinities as being more powerful than women and femininities (Connell Citation2005; Messner Citation1990, Citation1992; Messner, Dunbar, and Hunt Citation2000). From this perspective, the violent content of certain sports functions as a masculinizing capacity that enforces this symbolism. This implies what could be called the feminist challenge in sport, or how sport reproduces a patriarchal power order in societies (see e.g. Pringle Citation2018). From this critical and feminist perspective, compiling different rules for women and men is problematic, which is the case in ice hockey where men are allowed to have more physical contact and less protective equipment than women (helmet grits are compulsory for women but not for senior men, who at international level are also allowed to body check each other) (Dicarlo Citation2016; Weaving and Roberts Citation2012). Despite, or perhaps due to this, strongly gendered and sex-separated sports also have potential as areas for women and feminine emancipation (Castan-Vicente and Bohuon Citation2020).

The insights mentioned above put the negotiations and views of the so-called ‘violent’ content in sports like ice hockey in a different and more critical and feminist light. In short, the violent ingredients can either maintain or challenge the current gender order. On the one hand, different people’s perceptions of playing styles and rules are probably only related to the sport itself. On the other hand, such debates can be interpreted as a negotiation about men’s opportunities to appear as masculine with the implicit aim of subordinating or minimizing the possible feminizing content of the sport. When hard and aggressive playing is not encouraged in women’s ice hockey, it reproduces a notion of women’s bodies as less sturdy and more fragile than those of men (Dicarlo Citation2016; Theberge Citation1997, Citation1998). An analysis of actions and attitudes connected to violations and fighting, such as embodying masculine ideals in ice hockey, has the potential to reveal insights into how reproductive forces of men’s power over other men, and over women, work via sport.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allain, K. A. 2008. “Real Fast and Tough”: The Construction of Canadian Hockey Masculinity.” Sociology of Sport Journal 25 (4): 462–481. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.25.4.462.

- Allain, K. A. 2011. “Kid Crosby or Golden Boy: Sidney Crosby, Canadian National Identity, and the Policing of Hockey Masculinity.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 46 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210376294.

- Allain, K. A. 2014. “What Happens in the Room Stays in the Room’: Conducting Research with Young Men in the Canadian Hockey League.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 6 (2): 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.796486.

- Allain, K. A. 2019. “Hegemony Contests: Challenging the Notion of a Singular Canadian Hockey Nationalism.” American Review of Canadian Studies 49 (4): 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2019.1714681.

- Andersson, H. 1973. “KHC Spelar För Publiken!” [KHC Plays for the Spectators!].” Hockey 9 (2): 5.

- Andersson, H. 1992a. “Hockeyinvalid Nummer Två i MoDo Hockey’ [Hockey Disabled Number Two in MoDo Hockey].” Hockey 28 (3): 70.

- Andersson, H. 1992b. “Ishockeyoffer Hjälper Andra’ [Ice Hockey Victim Helps Others].” Hockey 28 (4): 70.

- Andersson, H. 1992c. “Otursförföljd Tomas Sandström’ [Misfortuned Tomas Sandström].” Hockey 28 (11): 67.

- Andersson, H. 1992d. “Snacka Inte Om Panik Eller Kris!’ [Do Not Talk about Panic or Crisis!.”] Hockey 28 (3): 10.

- Andersson, H. 1993a. “Små Marginaler – Väntad Finalplats Blev Femte Plats’ [Small Margins - Expected Final Became Fifth Place].” Hockey 29 (11): 9.

- Andersson, H. 1993b. “Stefan Larsson i Huvudroller’ [Stefan Larsson in Principal Parts].” Hockey 29 (11): 23.

- Andersson, H. 1993c. “Tomas Sandström Svårt Skadad Igen’ [Tomas Sandström Badly Injured Again].” Hockey, 29 (2): 43.

- Andersson, H. 1995. “Blåmärken Bort, Poängen Kvar’ [Bruises Vanish, Points Remain].” Hockey, 31 (5): 68.

- Andersson, H. 1997a. “Finska Kaxigheten Däckades’ [Finnish Cockiness Decked].” Hockey, 33 (1): 10.

- Andersson, H. 1997b. “Tommy Samuelsson Svårt Skadad’ [Tommy Samuelsson Badly Injured].” Hockey, 33 (1): 61.

- Apatinga, G. A., and E. Y. Tenkorang. 2021. “Determinants of Sexual Violence Among Married Women in Ghana: Qualitative Evidence From Ghana.” Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment 33 (4): 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063220910728.

- Backman, J. 2018. Ishockeyns Amerikanisering: En Studie Av Svensk Och Finsk Elitishockey [Ice Hockey’s Americanization: A Study of Swedish and Finnish Elite Ice Hockey]. Malmö: Malmö universitet, Idrottsvetenskap.

- Castan-Vicente, F., and A. Bohuon. 2020. “Emancipation through Sport? Feminism and Medical Control of the Body in Interwar France.” Sport in History 40 (2): 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2019.1652845.

- Channon, A., and C. R. Matthews. 2018. “Love Fighting Hate Violence: An anti-Violence Programme for Martial Arts and Combat Sports.” In Transforming Sport: Knowledges, Practices, Structures edited by D. Burdsey, T. F. Carter, & M. Doidge (pp. Chapter 7). London: Routledge.

- Connell, R. 1983. Which Way is Up?: Essays on Sex, Class and Culture. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Connell, R. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Polity in association with Blackwell.

- Connell, R. 2000. The Men and the Boys. Cambridge: Polity.

- Connell, R. 2005. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Connell, R. 2008. “Masculinity Construction and Sports in Boys’ Education: A Framework for Thinking about the Issue.” Sport, Education and Society, 13 (2): 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320801957053.

- Corboz, J., M. Flood, and S. Dyson. 2016. “Challenges of Bystander Intervention in Male-Dominated Professional Sport: Lessons From the Australian Football League.” Violence against Women 22 (3): 324–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215602343.

- Demetriou, D.,. Z. 2001. “Connell’s Concept of Hegemonic Masculinity: A Critique.” Theory and Society 30 (3): 337–361. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017596718715.

- Dicarlo, D. 2016. “Playing like a Girl? The Negotiation of Gender and Sexual Identity among Female Ice Hockey Athletes on Male Teams.” Sport in Society 19 (8-9): 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1096260.

- Dunning, E. G., and J. Maguire. 1996. “Process-Sociological Notes on Sport, Gender Relations and Violence Control [Article.” ]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 31 (3): 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029603100305.

- Elofsson, S. 1993. “Thomas Javeblad Har Gjort Come-Back’ [Thomas Javeblad Has Made Comeback].” Hockey 29 (12): 54.

- Ericson, S. 1976. “Bröderna Salming – Fruktad Svensk Duo i World Cup!’ [The Salming Brothers - Dreaded Swedish Duo in the World Cup!].” Hockey 12 (5): 10

- Fagerlund, R. 1993. “För En Kapacitet Som Conny Evensson Finns Det Alltid Plats – Alla Våra Landslagskaptener Är Dock Mycket Kompetenta’ [For a Capacity like Conny Evensson, There is Always Room – However, All Our National Team Captains Are Very Competent].” Hockey, 29 (12): 3.

- Fagerlund, R. 1994. “Konsten Att Vårda Sig Själv’ [The Art of Taking Care of Oneself].” Hockey 30 (12): 30.

- Fields, S. K., C. L. Collins, and R. D. Comstock. 2007. “Conflict on the Courts: A Review of Sports-Related Violence Literature.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 8 (4): 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838007307293.

- Flood, M. 2008. “Men, Sex, and Homosociality: How Bonds between Men Shape Their Sexual Relations with Women.” Men and Masculinities 10 (3): 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06287761.

- Flood, M., and S. Dyson. 2007. “Sport, Athletes, and Violence against Women.” NTV Journal, 4 (3): 37–46. https://xyonline.net/sites/xyonline.net/files/Flood%20Dyson%2C%20Sport%20and%20violence%20against%20women%2007.pdf.

- Forsdike, K., and G. O’Sullivan. 2022. “Interpersonal Gendered Violence against Adult Women Participating in Sport: A Scoping Review.” Managing Sport and Leisure https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2116089.

- Gramsci, A., and D. Forgacs. 2000. The Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935. New York: New York University Press.

- Gruneau, R. S., and D. Whitson. 1993. Hockey Night in Canada: Sport, Identities and Cultural Politics. Toronto: Garamond Press.

- Guttmann, A. 2004. From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports (Updated with a New Afterword. ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hammarlund, U. 1992a. “Michael Nylander Är Historisk’ [Michael Nylander is Historic].” Hockey 28 (4): 35.

- Hammarlund, U. 1992b. “Nu Siktar Jag På Salmings NHL-Rekord’ [Now I’m Aiming for Salming’s NHL Record].” Hockey 28 (6): 26.

- Hammarlund, U. 1995. “Kronorna” i Globen’ [‘The Crowns’ in the Globe].” Hockey, 31 (5): 13.

- Hearn, J. 2004. “From Hegemonic Masculinity to the Hegemony of Men.” Feminist Theory 5 (1): 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700104040813.

- Hearn, J., S. Strid, A. L. Humbert, and D. Balkmar. 2022. “Violence Regimes: A Useful Concept for Social Politics, Social Analysis, and Social Theory.” Theory and Society 51 (4): 565–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-022-09474-4.

- Hedberg, A. 1993. “Hockeyn För Impotent – Gör Något Radikalt!’ [Hockey is Too Impotent – Do Something Radical!].” Hockey 29 (11): 66.

- Hedberg, A. 1996. “Mindre Rinkar – Självklart – Men Bara i Elitserien’ [Smaller Rinks – of Course – but Only in the Premier Division].” Hockey 32 (12): 81.

- Hedberg, A. …]. 1997. “Vaknar Vi Inte Av Denna Knockout, Ja Då Vet Inte Jag…’ [If We Don’t Wake up from This Knockout, Well, Then I Don’t Know.” Hockey, 35 (1): 33.

- Heise, L. L. 1998. “Violence Against Women: An Integrated, Ecological Framework.” Violence against Women 4 (3): 262–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002.

- Holt, R. 2009. Sport and the British: A Modern History. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Hunt, L. 2018. History: Why It Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Howson, R. 2006. Challenging Hegemonic Masculinity. London: Routledge.

- Johansson, K. 1992. “Temadag i Göteborg [Theme Day in Gothenburg].” Hockey 28 (6): 52.

- Ljunggren, J. 2020. Den Svenska Idrottens Historia [The History of Swedish Sport]. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Lorenz, S. L. 2015a. “Constructing a Cultural History of Canadian Hockey.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (17): 2107–2113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2016.1152265.

- Lorenz, S. L. 2015b. “Hockey, Violence, and Masculinity: Newspaper Coverage of the Ottawa ‘Butchers’, 1903–1906.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (17): 2044–2077. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2016.1147431.

- Lorenz, S. L. 2015. “Media, Culture, and the Meanings of Hockey.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (17): 1973–1986. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2015.1124863.

- Lorenz, S. L., and G. B. Osborne. 2006. “Talk about Strenuous Hockey’: Violence, Manhood, and the 1907 Ottawa Silver Seven-Montreal Wanderer Rivalry [Article.” ]. Journal of Canadian Studies 40 (1): 125–156. +253. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.40.1.125.

- Mauritzon, L. 1993. “Så Förändrades 20-Årige Martins Liv’ [That’s How 20-Year-Old Martin’s Life Changed].” Hockey 29 (1): 59.

- McKee, T., and B. Reid. 2020. “‘Man’s Game’: Media, Masculinity, and Early Canadian Hockey.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Masculinity and Sport, edited by R. Magrath, J. Cleland, & E. Anderson, 207–224. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Messner, M. A. 1990. “When Bodies Are Weapons: Masculinity and Violence in Sport [Article.” ]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 25 (3): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029002500303.

- Messner, M. A. 1992. Power at Play: Sports and the Problem of Masculinity. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Messner, M. A., M. Dunbar, and D. Hunt. 2000. “The Televised Sports Manhood Formula.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 24 (4): 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723500244006.

- Mountjoy, M., D. J. A. Rhind, A. Tiivas, and M. Leglise. 2015. “Safeguarding the Child Athlete in Sport: A Review, a Framework and Recommendations for the IOC Youth Athlete Development Model.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 49 (13): 883–886. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094619.

- Nilsson, S. 1976. “Hockeyvåldet’ [the Hockey Violence].” Hockey 13 (5): 27.

- Prego-Meleiro, P., G. Montalvo, Ó. Quintela-Jorge, and C. García-Ruiz. 2020. “An Ecological Working Framework as a New Model for Understanding and Preventing the Victimization of Women by Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault.” Forensic Science International 315: 110438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110438.

- Pringle, R. 2018. “On the Development of Sport and Masculinities Research: Feminism as a Discourse of Inspiration and Theoretical Legitimation.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Feminism and Sport, Leisure and Physical Education, edited by L. Mansfield, J. Caudwell, B. Wheaton, & B. Watson, 73–93. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Robidoux, M. 2002. “Imagining a Canadian Identity through Sport: A Historical Interpretation of Lacrosse and Hockey.” Journal of American Folklore 115 (456): 209–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/4129220.

- Robidoux, M. A. 2001. Men at Play: A Working Understanding of Professional Hockey. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Smith, M. 1979. “Hockey Violence: A Test of the Violent Subculture Hypothesis.” Social Problems 27 (2): 235–247. https://doi.org/10.2307/800371.

- Spaaij, R. 2008. “Men Like Us, Boys Like Them Violence, Masculinity, and Collective Identity in Football Hooliganism.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 32 (4): 369–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723508324082.

- Stark, T. 2001. “Pionjären, Polar’n Och Poeten: Maskuliniteter, Nationella Identiteter Och Kroppssyn Inom Kanadensisk, Svensk Och Sovjetisk Ishockey under Det Kalla Kriget [[The Pioneer, the Buddy and the Poet: Masculinities, National Identities and Body Perceptions in Canadian, Swedish and Soviet Ice Hockey during the Cold War].” Historisk Tidskrift [Journal of History] 2001 (121): 691–722.

- Stark, T. 2010. Folkhemmet på is: Ishockey, modernisering och nationell identitet i Sverige 1920-1972 [People’s home on ice: ice hockey, modernisation and national identity in Sweden 1920-1972]. idrottsforum.org. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-5606.

- Stark, T. 2017. “Från “Lappjävel” till” the King” Börje Salming, NHL, Och Den Svenska Modellen [From ‘Fucking Sami’ to ‘the King’: Börje Salming, NHL, and the Swedish Mode].” Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum 8: 163–196. http://lnu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1209423/FULLTEXT02.

- Sønderlund, Anders L., Kerry O'Brien, Peter Kremer, Bosco Rowland, Florentine De Groot, Petra Staiger, Lucy Zinkiewicz, and Peter G. Miller. 2014. “The Association between Sports Participation, Alcohol Use and Aggression and Violence: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 17 (1): 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.011.

- Taliaferro, L. A., B. A. Rienzo, and K. A. Donovan. 2010. “Relationships Between Youth Sport Participation and Selected Health Risk Behaviors From 1999 to 2007.” The Journal of School Health 80 (8): 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00520.x.

- Tegner, Y., and R. Lorentzon. 1992. “Hjärnskakning Hos Ishockeyspelare’ [Concussion Amongst Ice Hockey Players].” Hockey 28 (7): 65

- Theberge, N. 1997. “It’s Part of the Game’: Physicality and the Production of Gender in Women’s Hockey.” Gender & Society 11 (1): 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124397011001005.

- Theberge, N. 1998. “Same Sport, Different Gender: A Consideration of Binary Gender Logic and the Sport Continuum in the Case of Ice Hockey.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 22 (2): 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372398022002005.

- Tosh, J. 2019. Why History Matters. 2nd ed. London: Red Globe Press.

- TT. 2022. SHL-Profilerna: Krymp Rinkarna i Svensk Ishockey [The SHL Profiles: Shrink the Rinks in Swedish Ice Hockey]. Stockholm: Dagens Nyheter.

- Vaz, E. W. 1982. The Professionalization of Young Hockey Players. Nebraska: Univ. of Nebraska press.

- Waling, A. 2019. “Problematising ‘Toxic’ and ‘Healthy’ Masculinity for Addressing Gender Inequalities.” Australian Feminist Studies 34 (101): 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2019.1679021.

- Weaving, C., and S. Roberts. 2012. “Checking In: An Analysis of the (Lack of) Body Checking in Women’s Ice Hockey.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 83 (3): 470–478. https://doi.org/10.5641/027013612802573120.

- Wedin, C. 1993. “Dags För Stockholm Och Globen Att Stödja AIK Och Djurgården’ [It’s Time for Stockholm to Support AIK and Djurgården].” Hockey, 29 (1): 23.

- Weinstein, M. D., M. D. Smith, and D. L. Wiesenthal. 1995. “Masculinity and Hockey Violence.” Sex Roles 33 (11-12): 831–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544782.

- Young, K. 1993. “Violence, Risk, and Liability in Male Sports Culture.” Sociology of Sport Journal 10 (4): 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.10.4.373.

- Young, K. 2012. Sport, Violence and Society. London: Routledge.