Abstract

Children’s competitive sport in Australia poses barriers for children with disabilities. Sporting structures generally do not provide opportunities for children with disabilities to compete in a manner that is meaningful and fair to them, and generally not with the mainstream competitions. Such treatment may be discriminatory, either wrongfully or unlawfully so. Using Australia’s Little Athletics as a case study, this paper uses systems thinking to holistically map the influences on a child with disability’s experiences in a sporting contest, to identify how the socially constructed environment affects structures and rules and how the law might shape those.

Introduction

Sport is structured in such a way to promote fairness; for example, age-groups, gender divisions, weight and/or skill-based divisions, have all been used to provide fair opportunities for children in sports (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019). Children with disabilities are provided with disability specific sports, or segregated and separate categories within some sport, so they have the opportunity to compete in a fair way. These opportunities are often provided separately from the sporting opportunities for children without disabilities (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019; Inclusive Sport Design 2021). Children with disabilities, do not have the opportunity to compete fairly with and against their able-bodied or ‘mainstream’ peers (those without a disability); that is, where their disadvantage in the contest is recognised in the structures, requirements and rules. When children with disabilities are permitted to compete with and alongside mainstream children and adjustments are not made to account for disadvantages the rules pose for them, they are not being treated fairly. Separate and segregated opportunities, or arrangements to take part in the mainstream without appropriate adjustments, have been argued to be discriminatory (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019; Pearce Citation2017; Pearce Citation2021), because they treat a child with a disability less favourably than children without disability, on account of their disability (Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) sec. 5A(2), 5B(2), 7B ‘DDA’).

Scholarly consideration about sport for people with disabilities is diverse (Patel Citation2015). There is however, little literature that addresses fair sporting contests for people with disability, especially children, competing with and against mainstream athletes in a fair and meaningful way, taking into account adjustments to rules and structures. (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019). The gap in the literature suggests that discrimination theory or perspectives and discrimination law have not been considered or applied to these circumstances.

Systems thinking, or systems mapping, provides the platform to consider the place the structures and rules of sport play in the environment of sport for children with disability. Systems thinking involves taking a holistic view of an environment as an entire system to identify potential problems and workable solutions (Bellew et al. Citation2020). The purpose of a systems approach is to identify ways to challenge the underlying structures and supporting mechanisms that lead to certain outcomes for the participants. Importantly, it can ‘aim to change the way people think about problems’ (Stave and Hopper Citation2007) and is a ‘paradigm… emphasi[sing] universal interconnectivity’ (Pierson-Brown Citation2020). When the problem relates to children with disability and their experience in competitive sport, systems thinking provides an opportunity to generate solutions which address the complexities of the problem.

In this paper, systems thinking will be applied to the environment of Little Athletics to determine what role the structures and rules of the sport play in providing a fair, competitive sporting opportunity for children with disability, particularly with mainstream participants. It also identifies the influence discrimination law can play in rectifying discriminatory structures and practices. In so doing, it will highlight how the rules of sport might perpetuate or minimise discrimination for children with disabilities. More broadly, using a systems approach allows us to consider how to adjust the sport’s legal and institutional arrangements to remove any limitations or adverse consequences for children with disabilities wanting fairness and a meaningful experience or ‘true inclusion’, in competitive Little Athletics. This is consistent with the Regulatory Approaches to Movement, Physical Activity, Recreation, Transport and Sport (RAMPARTS) framework of legal strategies to improve physical activity in populations (Nau et al. Citation2021).

Whilst this paper is specific to Little Athletics Australia and the law in Australia, there are valuable lessons that the paper demonstrates for all sports and in an international context. Systems mapping can demonstrate how the law is an overarching influence on the rules and structures of any sport, and the experience of children with disability. It emphasises important connections and influences within the organisational framework. The exercise of mapping the entire sporting structure, as we have done with Little Athletics, produces insightful results which may assist other sporting organisations, policy makers and academics regardless of sport or jurisdiction.

To demonstrate how we applied systems thinking to Little Athletics, this paper has four parts. Part 1 explains systems thinking, and its utility for solving problems. It also explains the way systems thinking can be a platform to identify challenges children with disability in Little Athletics. Part 2 identifies and explains the challenges for children with disability when they compete in Little Athletics. Part 3 explains discrimination and how systems thinking can identify the law’s role in Little Athletics structures. Finally, Part 4 applies systems thinking and explains how taking that holistic approach to sporting structures can lead to a better competition experience for athletes.

Part 1 Systems thinking

A systems thinking approach explained

A system relates to, or more particularly describes, interconnected parts or elements that function together (Foster-Fishman, Nowell, and Yang Citation2007). Systems mapping, then, is a paradigm to identify and analyse the system as a whole rather than individual elements in isolation (Cavill et al. Citation2020). Systems thinking involves several key characteristics including:

assessing a system as a ‘whole’ rather than as a ‘part’;

recognising and understanding interconnections and feedback;

understanding dynamic behaviour;

appreciating the system’s role in causing the behaviour; and

understanding how the system’s structure generates behaviour (Stave and Hopper Citation2007; Ossimitz Citation2000).

Importantly, systems thinking allows for consideration of direct and indirect interventions, contexts of those interventions, relationships between the factors and the way the system responds to changes (Cavill et al. Citation2020). It is a reconceptualisation of institutional responses to solve a complex problem.

Systems thinking has been used predominantly to respond to issues at a social or community level because it addresses systemic problems. Systems thinking is particularly helpful for solving problems because it is not trapped by ‘pressures and incentives that legal rules and social institutions create’ (Pierson-Brown Citation2020). Solving problems has been related to a shift in thinking:

If we want to bring about the thoroughgoing restructuring of systems that is necessary to resolve the world’s gravest problems… the first step is thinking differently. Everybody thinking different. The whole society thinking differently (Meadows 1991).

There are other types of network approaches to considering contextual environments such as the socio-ecological framework, commonly used in health and health education sector reviews (Golden and Earp Citation2012; Chambers et al. Citation2012). This article does not consider the merits of particular social network models. The systems mapping approach was applied, because it is a ‘method to understand complexity’ (Smith Citation2009, p. 35), had not been applied in a setting such as this in the past, and provided a suitable visual application of the concepts. Other social network models were not considered here.

Systems thinking and the social model of disability

Systems thinking is, arguably, a fundamental application of the social model approach to the treatment of children with disability in sport. The social model is universally considered to provide the preferred foundational approach and perspective to considering the experiences of people with disability (Levitt Citation2017). Fundamentally, the social model considers that the socially constructed environment is what poses barriers for children (people) with disability, and that the ‘problem’ is not the impairment the person has (Mitra Citation2018; Fredman et al. Citation2017). Structures and rules of a sporting contest are socially constructed and might pose a barrier to a person with disability being included in the activity—particularly in a fair way. This socially constructed environment of sporting contests is often from an ableist perspective: that sporting competitors will be ‘able’, disregarding impairments that might place them at a disadvantage in the contest.

Considering barriers posed to a person with a disability by the environment and social structures, both physical and attitudinal (including laws, rules and policies), are essential to the social model. One example of a physical barrier would be if a person in a wheelchair is offered entry to a building only via stairs; the building creates a physical barrier rather than the person’s impairment or use of a wheelchair. An attitudinal barrier would be when visual rather than audible notices are provided approaching a train station (Innes v Rail Corporation NSW 2013, 36). The social model, then, considers what adjustments or requirements are needed to address barriers to the experience for a person with a disability when compared to a person without a disability (Oliver Citation2013; Levitt Citation2017). In relation to sport, the social model considers the rules of the sport and how they might be adapted to ensure a person with disability can compete in a way that accounts for their disability and accommodates their disadvantage. In other words, the contest is fair.

We acknowledge that there are various extrapolations of the social model. There are also more advanced, sophisticated and nuanced ways to consider the treatment of a person with disability, with a view to addressing disadvantage or wrongs. We do not propose to explain or apply the more advanced models or theories in this paper. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the place the rules, structures and policies of sport can play in the experience of a person with disability in sport, and the way law might assist within the holistic system. The systems mapping exercise is a valuable tool for that preliminary step, and may lead to further, more advanced applications of other models or theories, such as Critical Disability Theory (Mladenov Citation2013), the interactional model (Mitra Citation2018), the social relational model (Smith and Bundon Citation2018), and the human rights model (Lawson and Beckett Citation2021). The social model approach focuses the perspective on the social structures as barriers and potential solutions for people with disability. The social model approach is required to advance the rights and place of people with disability.

The approach in the systems mapping exercise applied to Little Athletics is novel, and yet, easily understood. As Brighton et al. (Citation2021, p. 394) note, referring to Smith and Sparkes (Citation2020), ‘a major challenge in moving disability sport forward, is conducting research that makes a real difference in the lives of disabled people over time’. They conclude, ‘[i]maginative theorization is only one of the ingredients required in contributing to this collective effort’ (Brighton et al. Citation2021, p. 394). Here, we use the systems map to demonstrate in a visual way, the social model of disability for children in Little Athletics, to consider how the socially constructed environment impacts the experience of a child, and what ‘rights’ or ‘wrongs’ might be addressed within that environment to improve the experience for children with disability. The systems thinking approach identifies the holistic view of the socially constructed environment, together with other factors, to identify which parts of the system might be adjusted or addressed to influence how children with disability are treated in Little Athletics.

The foundational approach of the social model is to consider the environment and social structures, including laws and rules, and consider how they might be framed differently to treat a person with disability in a way that is comparable to the mainstream. That approach might not resolve all the challenges or barriers for a person with disability, but the perspective considers all that can be done to the social structures.

It is worth noting here that in applying the social model, whether it be considered as a philosophy for research or a tool for considering practical adjustments (Levitt Citation2017), some impairments cannot be accommodated through change to the social construct. For example, there are times when an experience is entirely visual, and therefore the construction of that activity cannot be adapted for a person with vision impairment. This example recognises that a person with visual impairment does have an impairment, and that a different experience will need to be developed for them—one that involves other senses, such as touch, sound or taste. Whilst the invariable difficulties for a person with a disability in navigating the world can challenge the social model approach, it is considered the preferred perspective from which to consider society’s treatment of, and influences on, people with disability (Oliver Citation2013), and forms part of many other extended or developed theories of disability. Children with disability in sport face many challenges that we were seeking to consider in the systems mapping process.

Part 2 Children with disability in Little Athletics

The rules of sport provide a framework for competition amongst participants (Greely Citation2004; Jones Citation2014). When those rules mean that children with disability cannot compete fairly, sporting organisations are faced with the challenge of reconceptualising their sport, or risk perpetrating discrimination. Unfortunately for sporting organisations, it is often the challenges which arise from the various systems in, and around, the sporting competition that can limit the opportunities to facilitate fairness for children with disabilities and those issues are intrinsic to the organisation’s functionality. The various systems in place, that may or may not be crafted and constructed by the sporting organisation, create a total environment which affects the participants’ experiences.

Little Athletics Australia is a national Australian sporting organisation providing modified Track and Field competition, known commonly as ‘Little Athletics’, to children aged 5 to 15 in Australia. The organisation comprises voluntary member organisations within the state and territories which provide grassroots to state level athletics competitions for children. Approximately 100,000 children participate in Little Athletics activities Australia-wide (Little Athletics Australia 2022). In 2020, Little Athletics received a grant from the National Disability Insurance Agency in Australia, that established the True Inclusion Project whose aim is to provide for an adjustment to the rules and structures of Little Athletics for the improved treatment of children with disability in the sport together with mainstream.

While Little Athletics provides opportunities for children with disabilities in a way that many other competitive sports do not, the True Inclusion Project was born from the understanding that there was much room for improvement within the structures and rules of the sport. The True Inclusion Project identified that the rules and structures of the sport were socially constructed and therefore part of the environment that affected the experience of a child with disability in sport; if changed could the rules provide a fair and meaningful contest for children with disability together with mainstream children?.

The difficulties for a child with a disability in Little Athletics are not readily recognised. Conceptualising the influences on the experience of children with disabilities in Little Athletics competition can be challenging given many factors contribute to a child’s experience, even where organisations are committed to developing opportunities. Systems thinking provides a suitable response to understand how the existing system, looking at the whole environment, influences the experiences in competitive athletics for children who have a disability. To understand the systems thinking approach and before applying systems thinking to the Little Athletics environment, it is important to understand the Little Athletics environment.

Challenges for children with disability in Little Athletics

When a child with a disability attends Little Athletics competitions, they are invited to take part in a variety of events, dependent upon their age (Little Athletics Australia Citation2021). Those events are modified forms of traditional Track and Field events, which include hurdles, high jump, triple jump, long jump, discus, javelin, shot put, and running events. Dependent upon their impairment, they may not be able to perform the activities required for the event, or their capacity to do so may be limited; for example, a child with a disability affecting lower limbs may not be able to jump. How a child with a disability takes part in the event may depend upon the Centre’s competition model and could become challenging for the child, their parents, and the facilitator of the event to navigate adjustments within the rules of Little Athletics because of resourcing, knowledge or time constraints.

Sport can, at times, be daunting for any child. When starting a new physical activity, a child may find the experience unnatural, or difficult, and it can affect their confidence (Jeanes et al. Citation2019). For children with disability, sport being designed as a contest, without consideration of their particular impairment, can exacerbate feelings of difficulty and insecurity (Jeanes et al. Citation2019). In Little Athletics, the activities require children to demonstrate how fast they are over certain distances, how far they can throw, and how far or high they can jump. When a child with disability takes part in activities designed to demonstrate prowess, there is a risk that they will feel inadequate, or lack confidence, if they are not as skilled as others (Darcy and Faulkner Citation2014; Darcy et al. 2010).

When children participate in sport, their parents are a significant influence on the experience in several ways. Many children are directed to sports their parents played or, at least, enjoyed (Jeanes et al. Citation2019). When parents watch their children’s sport, the parents’ attitude to the child’s involvement is often influential (Torres and Hager Citation2007). For example, a parent who encourages a child to be overly competitive, and ‘win’, can have harmful impacts on the children’s attitude to sport, and other areas of life such as reducing motivation and enjoyment in the sport as well as anxiety-related behaviours (Sánchez-Miguel et al. Citation2013; Spaschak Citation2020).

Sport is a contest which is designed to identify the superior competitor at certain activities (Greely Citation2004) as opposed to a non-competitive recreational activity. Whilst some recreational activities such as jogging for non-competitive reasons, have a sporting context, the recreational nature renders them leisure activities or exercise, because they lack the competitive aspect. When a sport is designed, there are rules created so that the sport is a fair contest (Greely Citation2004). Arguably, a sport that is not a fair contest will be less meaningful or considered to lack integrity. An example of the importance of fairness in sport is the application of the World Anti-Doping Code to prevent athletes using performance enhancing substances to gain an unfair advantage over other athletes (World Anti-Doping Agency Citation2021). So, while sporting rules facilitate fairness, traditionally, the rules of non-disability specific and mainstream sports have not been designed to consider that a person with a disability may be at a disadvantage in the sport.about the common approach to children with disabilities taking part in competitive sport is for the organisations to provide Multiclass or specialist disability specific categories or events. These structures attempt to facilitate opportunities for children with disability to have a physical experience of the sport in a fair way. Some organisations do not provide any particular opportunities for children with disability, which may be because they consider the children are not ‘reasonably capable of performing the actions’ necessitated within the rules of the sport; organisations assume a child with disability could not physically do the activity. For example, high jump or hurdles might be considered too difficult and therefore, the event is conducted without any consideration to a child with disability taking part. Even if organisations facilitated children with disabilities physically taking part in the sporting contest, a competitive opportunity is different from the mainstream. Competitive sport for children with disability are most commonly classification systems, specific programs, special small disability specific competitions, or teams for people with disability (AFL Community 2018; Brisbane Paralympic Football Program; Doncaster & District Netball Association). In Australia there is no recognised, formal practice of children with disability having an adjustment to rules to compete together with mainstream children.

Sporting governing bodies and sports systems have continued to perpetuate separate, segregated opportunities for sport, leisure, and cultural activities by people with a disability as both a desirable and fair offering (Swimming Australia Citation2020; Little Athletics Citation2020; Athletics Australia Citation2020). Whilst some people with disability may enjoy a separate and segregated offering, there is a research gap of examination as to the motivations for such preferences. There could be many reasons why people with disability may prefer segregated or separated sporting competitions, including internalised ableism (Campbell and Kumari Citation2008); success in the disability sport as opposed to being treated unfairly in the mainstream; or because separate offerings of sport provide children with disability an opportunity to embrace their difference—having a social network of people with common experiences.

Separating children with disabilities from mainstream competitors is not necessarily an appropriate solution to ensure fairness within the rules of the sport. Firstly, those offerings do not necessarily provide for all children with disability, because the categories are specific to a particular impairment (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019). Secondly, while segregated categories allow children’s disadvantages to be acknowledged and reasonable adjustments to be made to the rules of sport, it also emphasises that children with disability are different from their mainstream peers. In that way, treating children with disabilities separately is arguably treating them less favourably. While this paper does not critique such an approach further, it is worth noting here that when the rules of the sport allow for separate categories, they perpetuate stigma and exclusion of children with disabilities.

One sporting model which facilitates children with disabilities to compete separately to mainstream children is the classification system. Children with disabilities can have their impairments ‘classified’ to provide them with a definable category for competition. This classification system, referred to as ‘Multiclass’ in Little Athletics (Woods Citation2018) is a direct application of the international classification system used by World Athletics (World Para Athletics Citation2022). The rules of Little Athletics allow for disability classification to enable participation in Multiclass events (for example: Little Athletics Queensland Citation2020). Multiclass events are usually the same events offered to the mainstream athletes although with reduced offerings such as only some of the running races. The Multiclass offering of Little Athletics categorises only some children with disability into classification categories based on an assessment of the functional impact of their impairment on the activities required for the sport. The classification system purports to ensure fairness and enable children with disability to compete against others of the same category according to their capacity (Peers Citation2012). The classification system is used in many sports, and each sport’s classification system is different.

Despite the classification system appearing to provide fair opportunities for children with disabilities to compete in athletics, it can leave some children out of the system, at a disadvantage, or where ‘classified’, with less and/or different opportunity from their mainstream counterparts. Some disabilities are not addressed within the classification system which results in those children being unable to have a classification that would enable participation in the contest (Moritz and Pearce Citation2020). For example, a child with Cri Du Chat syndrome may not present with the relevant severity of functional impact to be considered within the athletics classification categories. Little Athletics events are not always offered with Multiclass categories so children with disability do not have the opportunity to compete fairly in those events, or they must compete against their mainstream peers without an adjustment being made to the contest which leaves them at a disadvantage in the contest.

Finally, there are a number functional impacts for some child with disability that are not considered at all in the rules nor otherwise adapted for the contest. For example, a child with autism may have difficulty with crowds, or sensory issues with uniforms that may impede their performance or deter them from performing at all. Those matters are not rectified by a classification system. As a result, the classification system can perpetuate disadvantage in the contests in sport, and lead to discrimination.

Part 3 Discrimination

Discrimination law, more specifically the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth)(DDA), provides for changes to the socially constructed environment to prevent discrimination against people with disability. The ableist approach to rules and the socially constructed environment treats people with disability in a way that can be discriminatory. Discrimination, in law, means that there has been treatment of the person that is unlawful because the law provides that they should not be treated differently (or less favourably) from others in the same circumstances. The law for people with disability in Australia provides that they are to be treated no less favourably than others without disability (not excluded), but also that at times, there will need to be changes to the environment, rules and structures to provide for or accommodate the person’s needs so they are not treated ‘less favourably’. The DDA expressly provides for accommodations for a person with disability. In this way, the law implements, and reflects, the social model approach to disability.

The law includes both human rights and domestic law. Children with disability have the human right to non-discrimination that influences and is implemented by the domestic law, and is relevant to the child’s experience in sport (Moritz and Pearce Citation2020). The human right to non-discrimination is, however, influential in the treatment of a child with disability in sport and is explored in article 30.5 of the Convention for the Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD). In this article, we do not specifically consider the human right to non-discrimination as a factor in the experience of a child with a disability in Little Athletics, because the domestic law is the primary influence over the experience of the child. The issue dealt with in this article, is that the law (including the human right to non-discrimination) might not be readily understood and implemented in sports administration practice, including in the rules and structures of the sport. Discrimination law operates as part of a system to influence the improved treatment of children with disability in sport. The systems thinking approach identifies that issue, and provides for consideration of how the law might be influential and implemented in practice.

Part 4 Applying systems thinking to Little Athletics for children with disability

Few sporting organisations have addressed, in a comprehensive way, a systems approach which would consider the range of issues and structures related to the experiences of children with disabilities in competitive sporting activities (Nixon Citation2007). For the True Inclusion Project, systems thinking was used to: identify the place the rules of the sport played in the environment and experience for a child with disability; and identify if law would be identified as part of the environment, and what role it could play.

Some sporting organisations have rules to govern segregated competitive sporting opportunities (Swimming Queensland 2020), yet there is little anecdotal or scholarly evidence to suggest that sporting organisations are exploring whether there is a better way to provide for children with disability within competitive sport (Jeanes et al. Citation2019). One helpful study concluded:

inclusive provision entails running additional opportunities for a narrow band of young people whose abilities may be similar to those of young people participating in mainstream teams. This narrow conceptualisation of inclusion… fails to contest existing power relations and norms and consequently perpetuates the marginalisation of a large proportion of young people with disabilities in community sport (Jeanes et al. Citation2018).

In these systems mapping study, we considered the circumstances and experience of children with disability in the competitive Little Athletics environment. Systems mapping examines the prevailing traditions of sport governance and public opinion that limit opportunities in sport for children with disabilities (Jeanes et al. Citation2018). Systems thinking was applied in the early stages of a broader project, that considered changes that might be made to the structures and rules of Little Athletics, to provide for children with disability to take part in contests together with and against mainstream children. This broader project was the ‘True Inclusion Project’ outlined above.

Little Athletics Australia, together with researchers from the University of the Sunshine Coast, were granted funding for the ‘True Inclusion Project’ to introduce a best practice competition framework for true inclusion of children with disabilities in Little Athletics—the provision of competition for children with disability together with and against the mainstream. Systems thinking was undertaken, as part of the True Inclusion Project, to explore the factors which influence the experience for children with disability in competitive athletics. This was intended to inform the deliberations of changes to structures and rules of the sport to provide for fair and meaningful inclusion. As part of that project, the researchers deliberating the issues of the experience of children with disability in Little Athletics, brought experiences in physiotherapy, law relating to sport and children, diversity and inclusion employment, Paralympic classification systems, with three researchers also bringing the perspectives of being parents of children with disability who had been involved in varying levels of Little Athletics as well as athletics and other sports outside of the Little Athletics system. This expertise was important in the Systems mapping exercise, as the researcher’s experience informed some of the input into the Systems Mapping process.

Additionally, and importantly, in undertaking the Systems mapping exercise, a focus group (Leech and Onwuegbuzie Citation2009) explored as many of the factors that could be identified that influenced the experience of children with disability in competitive Little Athletics. The focus group participants included various stakeholders in Little Athletics, including Member association representatives and staff, and inclusion advocates and staff. The focus group was held over a two hour period using the Zoom platform where the authors of this paper facilitated discussion amongst participants about the factors that influence the experience children—particularly children with disability, have in in the competitive experience in Little Athletics. Following the focus group, the systems map in was produced. This research is supported by the University of the Sunshine Coast’s human research ethics approval (A201466).

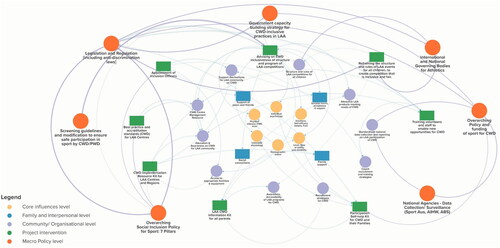

Figure 1. Systems map prescribing the structures of Little Athletics in Australia.

Abbreviations used for brevity: CWD (children with disability); LAA (Little Athletics Australia); PWD (people with disability)

This systems map was developed to identify: the factors in the holistic system at play for children with disability in competitive Little Athletics; and the potential new interventions around the structures and rules, within the system influencing the experience of children with disability in competitive Little Athletics. The results of the systems thinking exercise are illustrated in . Specifically, demonstrates the matrix of factors, individuals, organisations and influences that impact upon the experience of a child with disability in competitive Little Athletics. One interesting outcome of the focus group, was that no one identified the rules of the sport as a barrier to the involvement of children with disability in the sport, nor did anyone consider that law would apply to the experience or delivery of Little Athletics. The research team developed those elements, adding themd to the Macro level of the Systems map. The systems map also highlighted how the True Inclusion Project could intervene in a way intended by the grant, and have maximum impact, by targeting the rules, structures and the impact of the law on the delivery of the sport.

The systems map outlines a complex matrix of influences, and potential for interventions for improving the experience of children with disability in competitive Little Athletics. Systems thinking identified four levels of influence. Namely: core; family and interpersonal; community or organisational; and macro policy influences. Importantly, the four system levels often intersect and can influence others which further demonstrate the complexity of the Little Athletics structures; the different levels and their interaction with other influences were traced within the map. In this way, the systems map identified that addressing the four levels of influence individually or in isolation, would fail to reflect the intricacies of the various influences on the experience of a child with disability in Little Athletics. Further, it may produce an artificial list of influences at each level divorced from the realities of the barriers children with disabilities experience when seeking ‘true’ inclusion in competitive sport—such as the rules. Consequently, we identified through the systems mapping exercise that the levels of influence, how they interact and how they affect children with disability competing in Little Athletics, included the rules of Little Athletics as a barrier to inclusion; and the law as a potential solution to a child’s experience in Little Athletics, whilst taking into consideration the other elements that factor in the child’s experience.

Systems thinking provides an overarching approach whereby the totality of the influences upon a child with a disability can be considered. Mapping the various facets of the system that affects a child with a disability in Little Athletics, invariably draws perspective to influences that are socially constructed or created. Ultimately, the systems map highlighted the complexity of Little Athletics structures on children with disability. As mentioned above, while the individual levels are helpful to categorise the considerations for children with disability, there is so much overlap that isolating issues according to level was too challenging. Instead, looking at the systems map holistically, it identified two significant considerations which shape children’s experiences in Little Athletics. Firstly, the map identified that the law applied to all aspects of the system. Secondly, the map demonstrated that if the rules of the sport are to be adjusted to be influential on the experience of children with disability in Little Athletics, several other components of the system would need to be considered and addressed, to optimise success.

The rules of Little Athletics as a barrier for children with disability in sport

Sporting competition or sporting contests are regulated by the rules of the sport: enforced through the organisation’s governing body. Sporting rules are designed to generally emphasise the value of victory to the point of it becoming a central axis of the sport (Greely Citation2004). As part of this notion is the concept that a sporting competition should be fair (Greely Citation2004; Jones Citation2014).

Central to fairness in Little Athletics are the processes and mechanisms of ‘inclusion’ that operate within Little Athletics and the question of what happens or could happen to a child with disabilities who enters the track or field. Typical barriers for people with disabilities include society’s lacking awareness about how to involve children with disabilities adequately; the lack of understanding that inclusion in sport means more than the physical inclusion, but inclusion in a fair and meaningful contest; lack of opportunities and programs for training and competition; too few accessible facilities due to physical barriers; and limited information on, and access to, resources (Jeanes et al. Citation2019). A child with a disability’s access to ‘fairness’, will not be addressed unless and until the rules of the sport adequately take into account the provision of a fair and meaningful contest.

Sporting bodies can counteract challenges associated with a child’s disability. Here, there is a need to address the overarching rules of the contest by reforming policy frameworks for sport, and changing the rules so that they provide for children with disability to have adjusted opportunities for fairness in a meaningful way. Changing the way sport is run and operates will change the way a child with a disability and mainstream children are compared, with a view to levelling the playing field.

Of course, altering rules of traditional sporting contests is not necessarily straightforward. Systems thinking and mapping identifies the related influences and issues that pose difficulties in adjusting rules or structures of sport. Specifically, our application of systems thinking identified the challenges to providing a fair and meaningful contest for children included the attitude of administrators, parents and other children; the equipment required to provide the experience; the capacity of children with disability to undertake the traditional activities of the sport in the way the rules applied to them; the way rules were fundamental in the child’s experience in the contest of Little Athletics (Pearce Citation2021); and the feelings and attitudes of the children with disabilities and their families. Further, the systems map identified that the law would apply to the way the sport was delivered, and that discrimination against children with disabilities in Little Athletics would be subject to the law. This provides a platform to intervene in structures, and rules of Little Athletics to change the treatment of children with disability in Little Athletics, and prevent potential wrongful or unlawful discriminatory practices.

The law’s role in the experience

Systems thinking provides valuable context for the role the law plays or could play in an environment. Rather than focusing on ‘traditional legal analysis’ considering the nature of the law only and its application to a problem, systems thinking provides a broader reflection of institutional behaviour and systemic influences for a more nuanced understanding of the legal issue (Pierson-Brown Citation2020). In this way, a systems thinking approach can allow for objective consideration of how to adjust the environment and remove limitations for children with disabilities wanting fairness and meaningful inclusion in not just competitive Little Athletics but any sport.

Systems thinking identified law as an influence from the macro policy level because that level is overarching the whole of the experience in Little Athletics. Law provides for legal ‘rules’ for almost all aspects of life. Accordingly, in a broad sense, law will apply to various aspects of a child’s experience in Little Athletics. For example, privacy laws affect the use of personal information, civil liability legislation and common law affect the safety standards and conduct of providers in the sport, criminal law provides protection from the risk of criminal conduct, workplace health and safety laws affect the conduct of employees and volunteers in providing the sport, and tenancy or property law affects the use of venues for the conduct of the sport. Importantly, when law applies to an aspect of an experience, it can influence the way the experience is provided or undertaken so as to comply with law, or avoid a failure to comply with law. For example, the risk of a civil liability claim ought to raise awareness of safety measures to be put in place, such as a net being used around a discus circle to contain a wayward discus.

Additionally, and as identified in a systems thinking approach, law can be a way to effectively change thinking and attitudes. Law is used in a variety of settings to influence conduct, particularly when it is to change an established or traditional paradigm (Black Citation2002; Freiberg Citation2010). The relationship between law and social attitude has been the subject of theoretical debate, especially in relation to the ability of the law to influence behaviour; when it has some social effect, law is important (Griffith Citation1979).

Despite the importance of law in underlying sporting rules, there has been conjecture about the extent that law can influence behaviour in the disability and competitive sporting space, particularly in relation to discrimination. Smith (Citation2006) identified that there have been failures in ‘soft’ approaches to legislation, and potentially prohibitive effects of mandatory and strict compliance regulation in the discrimination context. Smith (Citation2006) further argued that a ‘corporate responsibility’, self-regulatory and incentive-based regulation is the best prospect for changing the social construct upon which discrimination is founded. Such an approach considers the system, the organisation and how they fit together. However, there are issues with rediverting responsibility to organisations for addressing legal issues like discrimination. The current regulatory framework for dealing with discrimination, that is complainant driven, particularly from a vulnerable social category, is arguably ineffective in eliminating discrimination and will not succeed in altering the social construct (Allen Citation2016). Organisations may not be motivated to change their approach. Allen (Citation2016) explains that those likely to be affected by the system, in this case those with disabilities, do not necessarily have the skills, nor other resources and capacity to make the complaints or ensure their complaint is addressed and resolved which means the discrimination issues are not addressed. This was particularly pertinent to the True Inclusion Project given the affected parties are primarily children with disabilities and so are inherently vulnerable. Kanter (Citation2011) and Mor (Citation2006) argue that regulation or legislation can encourage behaviour, social attitude and construct, to accommodate and accept disability. The rules, then, prescribe the acceptable behaviour and condemn unacceptable behaviour and the rules of sport govern the community’s perceptions about constructing disability. The rules operate within the broader system and influence the whole system.

Law is used to effect macro policy conduct such as requiring people not be discriminated against for their sex, gender, age, race, or disability, through anti-discrimination legislation, which to be implemented, would require rules and structures to influence conduct. Likewise, law influences the community and organisational level of sport because the rules and structures of the sport, and the implementation of those by volunteers, need to comply with discrimination laws. If there is a law that provides that children with disability are to be treated in a particular way, that law can impact that child’s experience (Pearce and Moritz Citation2019). Law influences the family and interpersonal level in relation to the experience of a child with disability in Little Athletics, because law can shape attitudes and conduct. For example, if the law were to provide for children with disability to have access to buildings, as it does, then social attitudes develop to reflect the legal requirement. If the law were to provide for children with disability to have a fair and meaningful experience in sport, then that in turn can influence the social attitudes that children with disability take part and be treated fairly. If, however, there is no legal requirement for certain conduct, that may mean that social attitudes are reflective of the ‘norm’ that sport is for able bodied people, and that children with disability should be separated into different (and often lesser) offerings of the sport. In another way, the law can influence this level of the experience for children with disability because if the rules of the sport were attractive to children with disability, then there would be more children with disability take part, and families of those children would be more inclined to encourage their participation. Children with disability would benefit from the associated social and peer relationships. The final, intrapersonal level of influence on a child with disability’s experience in Little Athletics is also influenced by law. In particular, discrimination law affects a child with disability’s feelings of dignity and self-worth (Cologon Citation2014; Fredman et al. Citation2017). If a child is treated with respect and provided the same or comparable experiences to other children, they feel worthy and valued (Darcy and Faulkner Citation2014). If, however, children with disability are not provided the same opportunities, and are separated and segregated, and not provided comparable events or experiences, that in turn influences feelings of value and self-worth.

Systems thinking or mapping demonstrates that the law can have a significant impact or influence over the experience of children with disability in competitive sport. The law applies to all practices, polices, structures and rules that provide a child with disability their experience. To the extent that those structures perpetuate discriminatory practices—whether wrongful or unlawful, the law and different thinking about the way a child with disability takes part in the sport, can assist in improving their experience.

Conclusion

Little Athletics Australia, a national organisation delivering children’s Little Athletics, fosters diversity and inclusion for children with disability yet still operates within a broader system constrained by rules and competing environmental factors. Systems thinking provides a unique approach to consider the challenge of true inclusion for children with disability through mapping the entire system holistically to consider the competing influences in experiences of Little Athletics competitors.

The systems map, identified two key considerations relevant to the rules and laws which shape children’s experiences in Little Athletics. Firstly, the map identified that the law and rules of sport underlie all aspects of the system. Secondly, the map demonstrated that if the rules of the sport are to be adjusted to be influential on the experience of children with disability in Little Athletics, several other components of the system would need to be considered and addressed, to optimise success. That is, changing rules in isolation and without dealing with other system contributors, is unlikely to have the successful impact intended of reducing or preventing disadvantage to children with disabilities. Initiatives which target rule changes along with other supporting strategies will remove these barriers and allow for children with disabilities to have meaningful competition and true inclusion in sports like Little Athletics; indeed, further research could develop how any children’s sport might be non-discriminatory and truly inclusive.

Systems thinking demonstrates that the law is intimately connected to the socially created structures in sport, namely the structures and rules, and the attitudes towards those rules, and people with disability. Systems thinking identifies the key problems in ‘true inclusion’. These key problems are: that the rules are designed with an assumption that all children have the same physical and mental capacities (ableism) so are unfair to children with disabilities; the attitude that athletics is fixed and the contest cannot be altered; and the attitude that children with disability are not able to be included in the contest, and therefore need to be separated and segregated in different and often lesser events and contests. When it is understood that the law can be and is influential in a child’s experience in sport, then the law can be used to provide an optimal experience. The systems map recognises that the law is an overarching influence. The systems mapping exercise identifies that it may be discriminatory to children with disability to not provide adaptions to rules to provide a fair and meaningful experience in competition, together with mainstream children, or if separately, in a comparable way. There is scope for further consideration and creative thinking for a different perspective to be brought to the experience of all children for fair and meaningful treatment in the contests of sport. The systems mapping exercise demonstrates that law could influence the child with disability’s experience, when considered together with all the other influences that interconnect, such as administration, implementation, safety, attitudes of others, and the feelings of children who take part. Law then provides the solutions to the failures to provide children with disability a fair contest identified through systems thinking. This provides a platform for further research as to how any children’s sport could be restructured and the rules changed, to be non-discriminatory and truly inclusive.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by funding from the National Disability Insurance Agency (Activity ID 4-DXQ9S1D). The systems mapping from this paper was informed by industry stakeholders, including Little Athletics Australia staff and volunteers, who attended a forum and/or shared their thoughts and experiences of Little Athletics with the research team. We thank them for their time and valuable contributions.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligations as researchers, we are reporting that we received grant funding from the National Disability Insurance Scheme in partnership with Little Athletics Australia, a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. We have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and we have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from that partnership.

References

- “About Us”. 2022. Little Athletics Australia, https://littleathletics.com.au/about-us/

- Abreu, Dan., Travis W. Parker, Chanson D. Noether, Henry J. Steadman, and Brian Case. 2017. “Revising the Paradigm for Jail Diversion for People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Intercept 0.” Behavioral Sciences & the Law 35 (5–6): 380–395. doi:10.1002/bsl.2300

- “All Abilities Netball.” 2022. Doncaster & Districts Netball Association, https://www.ddna.com.au/all-abilities-netball/.

- Allen, Dominique. 2016. “Barking and Biting: The Equal Opportunity Commission as an Enforcement Agency.” Federal Law Review 44 (2): 311–335. doi:10.1177/0067205X1604400206

- Allender, Steven, Brynle Owen, Jill Kuhlberg, Janette Lowe, Phoebe Nagorcka-Smith, Jill Whelan, and Colin Bell. 2015. “A Community Based Systems Diagram of Obesity Causes.” PloS One 10 (7): E 0129683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129683

- Australia, Athletics. 2020. “Multi-Class Athletics.” Athletics Australia http://athletics.com.au/Participate/Multi-Class-Athletics/Intellectual-Impairment.

- Bagnall, Anne-Marie, Duncan Radley, Rebecca Jones, Paul Gately, James Nobles, Margie Van Dijk, Jamie Blackshaw, Sam Montel, and Pinki Sahota. 2019. “Whole Systems Approaches to Obesity and Other Complex Public Health Challenges: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6274-z

- Bellew, William, Ben J. Smith, Tracy Nau, Karen Lee, Lindsey Reece, and Adrian Bauman. 2020. “Whole of Systems Approaches to Physical Activity Policy and Practice in Australia: The Asapa Project Overview and Initial Systems Map.” Journal of Physical Activity & Health 17 (1): 68–73. doi:10.1123/jpah.2019-0121

- Black, Julia. 2002. “Critical Reflections on Regulation.” Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy 27: 1–35.

- Brighton, James, Robert C. Townsend, Natalie Campbell, and Toni L. Williams. 2021. “Moving beyond Models: Theorizing Physical Disability in the Sociology of Sport.” Sociology of Sport Journal 38 (4): 386–398. doi:10.1123/ssj.2020-0012

- Campbell, Fiona, and A. Kumari. 2008. “Exploring Internalized Ableism Using Critical Race Theory.” Disability & Society 23 (2): 151–162. doi:10.1080/09687590701841190

- Cavill, Nick, Debra Richardson, Mark Faghy, Chris Bussell, and Harry Rutter. 2020. “Using System Mapping to Help Plan and Implement City-Wide Action to Promote Physical Activity.” Journal of Public Health Research 9 (3): 1759. doi:10.4081/jphr.2020.1759

- Chambers, Duncan, Paul Wilson, Carl Thompson, and Melissa Harden. 2012. “Social Network Analysis in Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Scoping Review.” PloS One 7 (8): e41911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041911

- “Classification.” 2020. Swimming Australia, https://www.swimming.org.au/swim-1/compete/classification.

- Cologon, Kathy. 2014. “Issues Paper Inclusion in Education; towards Equality for Students with Disability.” Discussion Paper Policy Recommendations Written With Children With Disability Australia.

- Darcy, Simon, and S. Faulkner. 2014. All Kids Can Play: Report on the Children with Disabilities Accessing Mainstream Sports. https://www.uts.edu.au/about/uts-business-school/management/news/all-kids-should-play.

- Darcy, Simon, et al. 2022. “Getting Involved in Sport: The Participation and Non-Participation of People with Disability in Sport and Active Recreation.” (Research Project, Australian Sports Commission, in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney 2010).

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth). 1992.

- Foster-Fishman, Pennie G., Branda Nowell, and Huilan Yang. 2007. “Putting the System Back into Systems Change: A Framework for Understanding and Changing Organizational and Community Systems.” American Journal of Community Psychology 39 (3-4): 197–215. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0

- Fredman, Sandra, Meghan Campbell, Shreya Atrey, Jason Brickhill, Nomfundo Ramalekana, and Sanya Samtani. 2017. Achieving Transformative Equality for Persons with Disabilities: Submission to the CRPD Committee for General Comment no.6 on Article 5 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. University of Bristol: Oxford Human Rights Hub.

- Fredman, Sandra. 2011. Discrimination Law. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford Press.

- Freiberg, Arie. 2010. “Re-Stocking the Regulatory Tool-Kit.” David Levi-Faur and Avishai Benish (Eds), Jerusalem Papers in Regulation and Governance. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University.

- Friel, Sharon, Melanie Pescud, Eleanor Malbon, Amanda Lee, Robert Carter, Joanne Greenfield, Megan Cobcroft, Jane Potter, Lucie Rychetnik, and Beth Meertens. 2017. “Using Systems Science to Understand the Determinants of Inequities in Healthy Eating.” PloS One 12 (11): e0188872. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188872

- Golden, S. D., and J. A. Earp. 2012. “Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions.” Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education 39 (3): 364–372. doi:10.1177/1090198111418634

- Greely, Henry T. 2004. “Disabilities, Enhancements, and the Meanings of Sports.” Stanford Law & Policy Review 15 (1): 99.

- Griffith, John. 1979. “Is Law Important.” New York University Law Review 54: 339.

- “Inclusive Sport”. 2022. Sport Australia, https://www.sportaus.gov.au/participation/inclusive_sport.

- Innes v Rail Corporation NSW [2013]. 2022. FAMC 36, 2022.

- Jeanes, Ruth, Ramón Spaaij, Jonathan Magee, Karen Farquharson, Sean Gorman, and Dean Lusher. 2019. “Developing Participation Opportunities for Young People with Disabilities? Policy Enactment and Social Inclusion in Australian Junior Sport.” Sport in Society 22 (6): 986–1004. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1515202

- Jeanes, Ruth, Ramón Spaaij, Jonathan Magee, Karen Farquharson, Sean Gorman, and Dean Lusher. 2018. “Yes We Are Inclusive’: Examining Provision for Young People with Disabilities in Community Sport Clubs.” Sport Management Review 21 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2017.04.001

- Jones, Carwyn. 2014. The Bloomsbury Companion to the Philosophy of Sport. Edited by Cesar R Torres. London: Bloomsbury.

- Kanter, Arlene S. 2011. “The Law: What’s Disability Studies Got to Do with It or an Introduction to Disability Legal Studies.” Columbian Human Rights Law Review 42: 403.

- Lawson, Anna, and Angharad E. Beckett. 2021. “The Social and Human Rights Model of Disability: Towards a Complementarity Thesis.” The International Journal of Human Rights 25 (2): 348–379. doi:10.1080/13642987.2020.1783533

- Leech, N., and A. Onwuegbuzie. 2009. “A Typology of Mixed Methods Research Designs.” Quality & Quantity 43 (2): 265–275. doi:10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

- Levitt, Jonathan M. 2017. “Exploring How the Social Model of Disability Can Be Re-Invigorated: In Response to Mike Oliver.” Disability & Society 32 (4): 589–594. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1300390

- “Little Athletics Queensland”. 2020. Multi-Class Athletes. https://laq.org.au/competition/multi-class/.

- Macquarie Dictionary Online. 2022. https://www.macquariedictionary.com.au/.

- Meadows, Donella H. 1989. “System Dynamics Meets the Press.” System Dynamics Review 5 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1002/sdr.4260050106

- Mitra, Sophie. 2018. Disability, Health and Human Development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mladenov, Teodor. 2013. “The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Its Interpretation.” Alter 7 (1): 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.alter.2012.08.010

- Mor, Sagit. 2006. “Between Charity, Welfare, and Warfare: A Disability Legal Studies Analysis of Privilege and Neglect in Israeli Disability Policy.” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 18 (1): 64–137.

- Moritz, Dominique, and Simone Pearce. 2020. “Disability Discrimination in Children’s Competitive Sport.” University of New South Wales Law Society Court of Conscience 14: 53–57.

- “Multi Class”. 2021. Little Athletics Australia. https://littleathletics.com.au/events/multi-class/>.

- “Multi Class”. 2020. Little Athletics Australia. https://littleathletics.com.au/events/multi-class.

- “Multi Class Swimming”. 2020. Swimming Queensland. https://qld.swimming.org.au/multi-class-swimming.

- “National Inclusion Carnival”. 2018. AFL Community. http://community.afl/all-abilities/programs/national-inclusion-carnival#:∼:text=The%20AFL%20National%20Inclusion%20Carnival,every%20state%20and%20territory%20represented.

- Nau, Tracy, Ben Smith, Adrian Bauman, and Bill Bellew. 2021. “Legal Strategies to Improve Physical Activity in Populations.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 99 (8): 593–602. doi:10.2471/blt.20.273987

- Nixon, Howard L. 2007. “Constructing Diverse Sports Opportunities for People with Disabilities.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 31 (4): 417–433. doi:10.1177/0193723507308250

- Oliver, Mike. 2013. “The Social Model of Disability: Thirty Years On.” Disability & Society 28 (7): 1024–1026. doi:10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

- Ossimitz, Gunther. 2000. “Teaching System Dynamics and Systems Thinking in Austria and Germany (Conference Paper).” In International Conference of the System Dynamics Society.

- Parent, Dale G., and Liz Barnett. 2004. “Improving Offender Success and Public Safety through System Reform: The Transition from Prison to Community Initiative.” Federal Probation 68 (2): 25.

- Patel, Seema. 2015. Inclusion and Exclusion in Competitive Sport: Socio–Legal and Regulatory Perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pearce, Simone, and Dominique Moritz. 2019. “#Whataboutme: Can the Inclusion of Gender Diverse Children Pave the Way for Children with Disability in Sport?” Australian and New Zealand Sports Law Journal 13 (1): 155–182.

- Pearce, Simone. 2017. “Disability Discrimination in Children’s Sport.” Alternative Law Journal 42 (2): 143–148. doi:10.1177/1037969X17710623

- Pearce, Simone. 2021. “The Fundamental Nature of Sport: Disability, Discrimination and Sport in Holzmueller V. Illinois High School Association.” The International Sports Law Journal 21 (1–2): 74–93. doi:10.1007/s40318-020-00179-3

- Peers, Danielle. 2012. “Interrogating Disability: The (De)Composition of a Recovering Paralympian.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 4 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2012.685101

- Pierson-Brown, Tomar. 2020. “Thinking like a Lawyer.” Clinical Law Review 26 (2): 515.

- Sánchez-Miguel, Pedro A., Francisco M. Leo, David Sánchez-Oliva, Diana Amado, and Tomás García-Calvo. 2013. “The Importance of Parents’ Behavior in Their Children’s Enjoyment and Amotivation in Sports.” Journal of Human Kinetics 36 (1): 169–177. doi:10.2478/hukin-2013-0017

- Smith, Belinda. 2006. “Not the Baby and the Bathwater: Regulatory Reform for Equality Laws to Address Work-Family Conflict.” Sydney Law Review 28 (4): 689–732.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies. Edited by N. Watson and S. Vehmas. 2nd ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Smith, Brett, and Andrea Bundon. 2018. The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Smith, Timothy. 2009. Climate Change in Regional Australia: Social Learning and Adaption. Edited by J Martin, M Rogers & C Winter, Bendigo, Australia: VURRN Press.

- Spaschak, Allison. 2020. The Effect of Parental Pressure on the Stress, Self-Efficacy and Overall Well-Being of Athletes. New York: Kinesiology, Sport Studies, And Physical Education Synthesis Projects.

- Stave, Krystyna, and Megan Hopper. 2007. “What Constitutes Systems Thinking? A Proposed Taxonomy.” In Proceedings of the 25Th International Conference of the System Dynamics Society.

- “Supporting people of all abilities to stay active and healthy through sport”. Accessed 10 February 2022. Brisbane Paralympic Football Program. http://bpfp.com.au.

- Torres, Cesar R., and Peter F. Hager. 2007. “De-Emphasizing Competition in Organized Youth Sport: Misdirected Reforms and Misled Children.” Kinesiology, Sport Studies and Physical Education Faculty Publications 34 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1080/00948705.2007.9714721

- “What Is Classification.” 2022. International Paralympic Committee World Para Athletics Classification & Categories. https://www.paralympic.org/athletics/classification.

- Woods, Michael. 2018. Little Athletics Australia & Athletics Australia National Diversity & Inclusion Project Consultation. https://cdn.revolutionise.com.au/cups/tasathletics/files/gp9jqbjkpoqwffg1.pdf.

- “World Anti-Doping Code.” 2021. https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the-code.

- World Health Organization. 2022. “International Classification Of Functioning, Disability And Health: Children And Youth Version: ICF-CY.” Apps.Who.Int. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43737.