Abstract

Voluntary sports clubs (VSCs) are viewed by governments as an important catalyst for the integration of migrants/refugees. However, research has shown that only a small number of VSCs are directly involved in ‘integration through sport’ practices. To increase the number of VSCs that are willing and able to significantly implement targeted integration measures, it is necessary to understand how ‘integration through sport policies’ can actually reach the local level and impact practices. In this paper, we propose a conceptual framework that considers and bundles current integration research in organized sports. To address the complexity, a multi-level framework will be developed that helps to understand the roll-out strategies and implementation processes of integration programmes for migrants in organized sports. Additionally, it helps to support practitioners in developing appropriate evaluation schemes, or revising existing integration programmes at the local, regional or national level in order to increase the number of integrative VSCs.

Introduction

Despite COVID-19 and environmental issues, migration and the integration of both migrants and refugees are currently among the most urgent problems on the European agenda. The increasing influx of refugees and migrants into Europe since 2015/2016 has created an urgent need to develop and improve social integration policies and practices, especially in EU member states facing large-scale immigration. The relevance of this topic has been further intensified by the influx of refugees triggered by the war in Ukraine at the beginning of 2022.

Sport could serve as an important integration catalyst (Baker-Lewton et al. Citation2017; Spaaij Citation2015). In Europe, voluntary sports clubs (VSCs) in particular offer opportunities for building social contacts, intercultural relationships and emotional bonds, as sports club membership is usually accompanied by long-term, regular participation. This participation is almost always along with other members and is often accompanied by social activities (Mutz, Burrmann, and Braun Citation2022; Nagel et al. Citation2015, Citation2020b).

Based on the positive assessment of sport’s integrative potential in general, and of VSCs in particular, the European Commission and its member states support sports-based initiatives to integrate migrants and refugees into European host societies (European Commission Citation2022). Despite the existence of these programmes and policies at national and regional levels, only a comparatively small number of VSCs are directly involved in such targeted ‘integration through sport’ practices for migrants and refugees. For example, of the approximately 90,000 VSCs in Germany only 896 sports clubs were registered in the Integration through Sport programme in 2021 as ‘integration bases’ (DOSB Citation2022). It should be noted that VSCs can also specifically integrate migrants and refugees independently from any socio-political integration programmes. Yet, as a comparative study from ten European countries showed, the proportion of VSCs with specific initiatives for the integration of migrants and refugees (18%) is significantly lower than the percentage of VSCs with initiatives for children and adolescents (59%), low-income individuals (42%), girls and women (33%) or the elderly (25%) (Breuer et al. Citation2017).

To increase the number of VSCs that are willing and able to implement targeted proactive integration initiatives, it is necessary to understand how national or regional ‘integration through sport policies’ can reach VSCs and impact their practices. To comprehend how the roll-out strategies of programme initiators are set up and the extent to which these resonate with the VSCs and encourage them to implement integrative initiatives, it is necessary to look at the entire chain of effects in a more holistic manner.

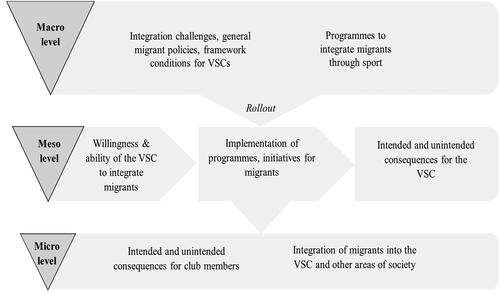

Based on this, the purpose of this paper is to develop a conceptual framework for a comprehensive analysis of public sports-based programmes to integrate migrants and refugees in VSCs. The conceptual framework can be used as a basis for empirical studies that aim to answer, for example, the following questions: (1) How are sport-based integration programmes for migrants and refugees rolled out to the level of VSCs? (2) Which factors are relevant when implementing these programmes in VSCs? (3) How do these programmes change VSCs as organizations? (4) What intended and unintended consequences can be observed for the autochthonous members as well as the migrants and refugees?

To enable a holistic analysis from the programme level to the individual level, the framework must include the macro level (policy), the meso level (VSC) and the micro level (autochthonous club members, migrants and refugees). This can be a promising starting point for sports federations and political authorities to manage and support the integration efforts of VSCs. In particular, it enables them to scale up the integration potentials without jeopardizing VSCs’ integrity and ability through requirements that go beyond their resources and capabilities.

This paper is structured as follows. We will first explain the research context and the general understanding of integration that framed the paper. In the next step, we will reflect on key studies on the topic and identify existing research gaps. In the main part of the paper, the conceptional framework will be developed. Both the review of the state of research and the development of the conceptual framework refer to the macro, meso and micro level. This will enable us to generate a holistic view for analysing the effects of public sports-based programmes to integrate migrants and refugees in VSCs. Finally, we will present perspectives for the practical and analytical application of the multi-level framework.

Research context

VSCs are non-profit organizations that are oriented towards the collective interests of their members and with an organizational logic based on self-organization and a pooling of resources to provide sports and social offers for their members (Coleman Citation1974). This assumes that club members are prepared to provide not only financial resources (membership fees), but also temporal resources (volunteer work) to collectively enable the running of the club. This does not preclude VSCs from having paid staff. However, volunteer work is predominant, although it varies between European countries (Breuer et al. Citation2015). The opportunities offered by the clubs are mostly of a sporting nature (e.g. playing football, participating in swimming competitions or learning to ski) or have a social element (conviviality). VSCs are organized under the umbrella of regional or national sports federations.

Public sports-based programmes in the field of integration in European countries often address several target groups at the same time. For example, the Danish Get2sport programme, the Swiss MiTu Move Together programme or the German Integration through Sport programme do not distinguish between migrants, refugees or asylum seekers. In the Norwegian Refugee fund programme and the Swedish Sport for newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers programme, the target group is more narrowly defined and refers to newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers (Fahlén and Stenling Citation2022). However, even when target groups are more precisely identified, there is often no exact delineation/definition of target groups or this differs between programmes and/or countries. Furthermore, VSCs usually do not distinguish between specific programmes and initiatives for migrants and refugees (Elmose-Østerlund et al. Citation2020). To adequately address this practical reality, we claim that our conceptual framework can be applied in the context of integrating both migrants and refugees (asylum seekers), regardless of the concrete, often country-specific, delineation.

For the sake of (linguistic) simplification, we will use the term migrants, but also include refugees (asylum seekers). An exception to this is made in the literature review where the distinction between migrants and refugees was made by the researchers themselves. We are in no way negating the (sometimes) important differences between the groups or within the groups. Rather, we clearly point out that when using our framework to analyse implementation practices and the impact of social policy programmes in the field of integration, the respective target group(s) must be named and delimited. This also means that the empirical analysis of the specific groups must take into consideration their heterogeneity (see conclusion). We have not performed delimitation/definition of the target group that is independent of the specific public sports-based programme in the field of integration, as this is not expedient.

For the development of the conceptual framework to comprehensively analyse the impact of public sport programmes to integrate migrants in VSCs, we conceptualize integration in line with Thiel, Seiberth, and Mayer (Citation2018) as a multidimensional process. This multidimensional process is based on reciprocity and equal participation and, at its core, targets the social inclusion of people in different parts of society. Integration implies a reciprocal exchange and approximation process, which opposes mere assimilation concepts and targets mutual acceptance when dealing with cultural differences. It also enables integration in the sense of a mutually satisfactory ‘interrelation of differences [Interrelation des Differenten]’ (Stichweh Citation2000, p. 86).

Literature review

In the following section, the most important findings of previous studies on the topic at different levels are presented in the form of a narrative review. Firstly, we focus on VSCs as policy implementers. In a second step, we look at key findings of VSCs as an integrative setting, before presenting findings on the effects of migrant participation in VSCs. Finally, we reflect on the previous findings and highlight research gaps.

Policy level: policy implementation in VSCs

A number of studies deal with the analysis of VSCs as policy implementers. Most of these focus on the evaluation of ‘integration through sport programmes’ (e.g. Agergaard Citation2011; Block and Gibbs Citation2017; Guerin et al. Citation2003). This line of research shows that approaches taken are generally functional at a pilot project level and that many effective practices exist. However, such studies rarely focus on the details of the intersection between (social) policy roll-out and the implementation of integration programmes and sport. There are, nevertheless, a growing number of studies that have examined the relationship between political authorities (as social planners) and VSCs (as policy implementers) in various sports development contexts (Fahlén, Eliasson, and Wickman Citation2015; Harris, Mori, and Collins Citation2009; May, Harris, and Collins Citation2013; Skille Citation2008; Stenling Citation2013). Such studies have shown that, in view of the heterogeneity and diversity of VSCs, many clubs have only a limited capacity to respond to the demands of policy delivery (May, Harris, and Collins Citation2013). Furthermore, the propensity for VSCs to act as policy implementers has been shown to be contingent on consistency between prevailing institutional logics and the norms that constitute the core of the VSC’s activities (Fahlén, Eliasson, and Wickman Citation2015; Stenling Citation2013; Stenling and Fahlén Citation2016).

Additionally, research has shown that clubs often react defensively when they perceive that something is being imposed on them from the outside (Skille Citation2008). As interest organizations, VSCs are ideally autonomous and independent. Therefore, it is difficult to impose changes in organizational structures directly from the outside (Thiel and Mayer Citation2009). This limits the possibility for direct external guidance and influence. It is important for policymakers to recognize the multifaceted objectives of VSCs as a determinant of the willingness to engage in policy implementation (Harris, Mori, and Collins Citation2009).

Club level: VSCs as an integrative setting

Current studies focus specifically on certain structural conditions and organizational capacities that can promote or hinder processes for integrating individuals with a migration background (Borggrefe and Cachay Citation2021; Kleindienst-Cachay, Cachay, and Bahlke Citation2012; Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020). For example, Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) emphasize the relevance of institutional logics, the importance of other club members with a migration background and the relevance of more professional organizational designs. Furthermore, Borggrefe and Cachay (Citation2021) point out that integration programmes within VSCs are primarily aimed at strengthening their social legitimacy (moral motive) and less at meeting the challenges of club development (e.g. recruiting volunteers, athletes or coaches; functional motive). Other studies focus on cultural patterns, which determine the intercultural openness and innovative potential of VSCs to become more integrative for specific target groups (Elling and Claringbould Citation2005; Seiberth, Weigelt-Schlesinger, and Schlesinger Citation2013).

In contrast, Dowling’s (Citation2020) findings from a critical discourse analysis revealed that local enactments of policy for integration were mostly built upon assimilationist ideas that could potentially exclude refugees. Collectively, research to date suggests that VSCs sometimes offer sport in ways that do not meet refugees’ needs, and there are difficulties associated with trying to include refugees in established sport structures (Jeanes, O’Connor, and Alfrey Citation2015). A lack of awareness of cultural differences (Dagkas and Benn Citation2006) and a lack of gender-segregated facilities (Stride Citation2014) have been found to be significant obstacles in welcoming migrant communities into VSCs. Focusing on such barriers, a few studies address both exclusionary practices as well as insights into the integrative practices of VSCs that illustrate the prerequisites for integrative processes and dealing with obstacles. Findings from these studies reveal that VSCs often develop pragmatic and innovative practices to include specific target groups, such as refugees, that go beyond the established routines of the club (Tuchel et al. Citation2021).

Individual level: effects of participation in VSCs for migrants

Migrants, and particularly refugees, can profit from a range of physical and -psycho-social benefits of organized sport that are likely to foster health and well-being by satisfying essential emotional needs (Anderson et al. Citation2019). Additionally, organized sports can have an impact on other aspects of refugee well-being (e.g. social health) by helping to develop social contacts in their new (host) country (Anderson et al. Citation2019). It is also noted that some migrant groups/refugees use sport to confirm their ethnic identity and sense of belonging with those from similar backgrounds (Krouwel et al. Citation2006).

Cultural capital can be a barrier to accessing sport (see the systematic review by Smith, Spaaij, and McDonald Citation2019). For example, parents’ negative attitude towards sport (Ramanathan and Crocker Citation2009) or a lack of knowledge about sports practices and rules in the host country (Caperchione et al. Citation2011) can restrict participation of refugees in sports activities. Likewise, language barriers can have a negative impact on participation in (organized) sport (Doherty and Taylor Citation2007). In addition, a large number of studies have analysed access among migrants and refugees to (organized) sport with consideration of socioeconomic, psychological, cultural and religious factors (see the systematic review by O’Driscoll et al. Citation2014).

In terms of social integration achieved by VSCs, existing studies show a continuum between two poles. On the one hand, clubs can promote the development of interethnic social relations and the acquisition of culture-specific knowledge and linguistic skills (Makarova and Herzog Citation2014). As members, migrants can participate in joint competitions and social club events, take on voluntary tasks and make use of the qualification offers available in VSCs. Such activities are found to strengthen the sense of common purpose, belonging and unity between members (Adler Zwahlen, Nagel, and Schlesinger Citation2018; Nagel et al. Citation2020b) and reduce social differences and the sense of being foreign (Makarova and Herzog Citation2014). Social networks and friendships (Seippel Citation2005) can also support and facilitate integration into other areas of society (transfer effects of sport to, for example, education and employment) (Block and Gibbs Citation2017). VSCs can also be a social setting where multiculturalism and ethnic concentration are negotiated and cultivated simultaneously (Broerse and Spaaij Citation2019).

On the other hand, current findings also indicate that the influence of sport on integration into a new host society is often less than assumed (Lundkvist et al. Citation2020). The reasons for this are manifold. Participation in sport and the associated integration effects are influenced both by institutional selection mechanisms as well as by individual options and choices (Elling and Claringbould Citation2005). At the individual level, for example, the distinct sporting habitus and physical strangeness can be relevant (Dukic, McDonald, and Spaaij Citation2017). Differences with regard to opportunities to participate in sport and their effects can also be intersectional and determined by the interaction of ethnicity and gender (Knoppers and Anthonissen Citation2001; Massao and Fasting Citation2014; Scraton, Caudwell, and Holland Citation2005).

In terms of institutional selection mechanisms, reasons can also be attributed to social closure mechanism and discrimination practices in VSCs (Doherty and Taylor Citation2007; Engh, Settler, and Agergaard Citation2017). Migrants and refugees can be marked as ‘strangers’, which gives rise to ethnic boundaries or in-group and out-group figurations (Elling, De Knop, and Knoppers Citation2001; Krouwel et al. Citation2006; Spaaij Citation2012, Citation2013). Being identified as a stranger can lead to ethnic discrimination (also in sport), as was shown in a large field experiment conducted among football clubs in Germany (Nobis et al. Citation2022).

Research gaps and considerations

Based on the existing research, four key research gaps can be identified that need to be addressed when developing a conceptual framework for a comprehensive analysis of the effects of public sports-based programmes to integrate migrants and refugees in VSCs.

There is little research that compares social integration factors at the macro level. Therefore, it is important to look at country-specific integration challenges and the general migration policy framework, as well as the concrete design of public sports-based integration programmes (roll-out) within the conceptual framework.

Only few findings exist about the organizational conditions, logistics and participants that are relevant in the process of implementing a specific integration programme or practice of social integration (roll-in) in VSCs. There is therefore a need for a theoretical framework on how public sports-based programmes to integrate migrants in VSCs are implemented from a structural perspective and implemented in their daily work (Skille and Stenling Citation2018).

The consequences within VSCs associated with their integrative engagement have been largely neglected in research to date. The consequences of structural and organizational changes during the implementation of integration programmes and initiatives with regard to the members’ orientation have so far not been sufficiently considered, either theoretically or empirically. When developing the conceptual framework, we therefore place a particular emphasis on the intended and unintended consequences of integrative initiatives for the VSC and its members.

To obtain a holistic view of the impact of public sports-based integration programmes, it is necessary to analyse to what extent migrants feel integrated in the VSC. Whether it is analysed to what extent participation in the club also supports integration in other areas of society. The multidimensionality of social integration must be taken into account within the conceptual framework.

Against the background of the research considerations and the associated consequences described above, we develop a multi-level analytical framework in the following section.

Multi-level analytical framework

Relevance of multiple levels and stakeholders

In the sense of a comprehension-explanatory sociology, it is essential to look at social phenomena by analysing social actors and their actions. A set of instruments for comprehensive system analysis in the context of implementing integration policies in sports requires a more consistent merging of different levels of analysis to describe implementation processes more precisely, considering cause-effect relationships. However, most approaches have examined influencing factors and interrelationships independently from one another at separate levels of analysis.

To explain changes in social structures (here: the increase in the integration capacities of VSCs), Esser (Citation1993) presented a basic model of sociological explanation that links the macro and micro levels (for VSCs: Nagel et al. Citation2015). The macro level comprises the social framework conditions for corporate (here: the VSCs) and individual actors (here: the autochthonous club members as well as the migrants) who are responsible for the (observable) collective outcomes. At the meso level of the organization, the structural characteristics and goals as well as the actions of the VSCs are important. When questioning the conditions of social integration, the consideration of the member’ perspective as well as the migrants’ perspective in relation to the club structure is essential (micro level). The multi-level conceptual framework for analysing roll-out and implementation strategies of sport integration programmes for migrants in VSCs is illustrated in .

The following section focuses on the specific extension potentials that a multi-level analytical approach opens up in the context of the implementation of social policy programmes in the field of integration of migrants.

Relevance of the macro level: policy making and roll-out

An investigation of the relevant socio-political context has to be conducted from two interdependent perspectives. The first perspective considers the specific integration challenges and general migrant policies framework in the country, as well as the general framework under which VSCs in the country operate. The second perspective considers the programmes (instruments) associated with attempts to integrate migrants through sport launched by public stakeholders (e.g. ministries and public agencies) or sports organizations (e.g. umbrella sport organizations).

Theoretical reflections for the macro level are structured using an institutional instruments approach to public policy analysis (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). In this approach, programmes are generally conceived of as the techniques by which actors wield their power – the concrete means used to conduct interventions and thereby (re-)structure behaviour (Vedung Citation2007). Programmes are thus ‘concrete action forms’ (Bemelmans-Videc Citation2007, p. 4) that reflect an interpretation of overarching policies and strategies. Furthermore, programmes are the ways in which ‘the intentions of policy could be translated into operational activities’ (De Bruijn and Hufen Citation1998, 12). In institutional understanding of programmes, they are viewed as a type of institution and, as such, their nature is political rather than neutral (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). Programmes reveal problem and solution constructions and thereby assign blame, mandate and (re-)shape roles as well as reshuffle resources. Furthermore, because programmes are not ‘self-implementing’ (De Bruijn and Hufen Citation1998, 26) they generate organizational machineries that go beyond the implementing organizations.

Beyond these general aspects, two elements of an institutional instruments approach are important: (1) Programmes are a type of institution, hence they are shaped by the institutional context in which they are constructed and implemented (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). (2) Programmes are understood to be constituted by both material and symbolic elements (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007). In terms of the material elements, the focus is on formalized rules (e.g. laws, time plans, budgets, programme instructions, work descriptions). The symbolic elements of institutions are understood as the lines of reasoning that are implicitly or explicitly associated with or underpin rules (for example the motivations that underpin a specific type of funding scheme or distribution of mandates among participating organizations) (Lascoumes and Le Galès Citation2007).

Relevance of the meso level: VSCs as an integrative setting

Willingness and abilities

The objective of tackling specific social problems (such as the inclusion of migrants as a specific target group) is not usually an explicit objective of clubs and their members (Seiberth, Weigelt-Schlesinger, and Schlesinger Citation2013). Thus, integrative efforts for migrants (as non-club members, at least initially) are not the self-articulated purpose of VSCs, particularly if such efforts contradict clubs’ values and members’ interests or overstretch their resources and capacities.

To make sporting activities accessible to migrants, the associated processes must be actively developed by the VSCs themselves (willingness) and based on their specific structural conditions and resources (abilities) (Skille Citation2008). Initiatives to integrate migrants can include, for example, specific sports activities that are known to migrants, reduced or no membership fees, discounted access to sports equipment, support with language problems and administrative procedures, or cooperations with other organizations in and outside of sport (e.g. other VSCs, schools, municipal or district offices) related to integration (Breuer et al. Citation2017).

Willingness is closely related to the institutional logics and programmatic guiding principles within a VSC (Stenling and Fahlén Citation2016; Thiel and Mayer Citation2009). An institutional logic can be understood as the formal and informal rules that guide decision-makers in performing the tasks of the organization. Such rules comprise a set of values and assumptions about an organization’s reality, appropriate behaviour and success (Stenling and Fahlén Citation2016). Therefore, VSCs are much more likely to be willing to take part in integrative initiatives if the arguments behind the measure are compatible with the logic that guides their behaviour. They also need to fit with their principles (for example, recruiting new members to identify potentially talented athletes, improving the club’s image by becoming more ‘coloured’ or intercultural, or legitimizing public subsidies) (McDonald, Spaaij, and Dukic Citation2019; Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020), and not because of any socio-political or moral claims (Kleindienst-Cachay, Cachay, and Bahlke Citation2012).

Willingness might also be associated with shared visions of integration within the club. Such aspects are not explicitly formulated but have rather developed historically in the form of informal rules. These can be seen in the club’s culture and significantly address the issue of social integration within the club (Seiberth, Weigelt-Schlesinger, and Schlesinger Citation2013). In this context, the extent to which boundaries are drawn in the VSC between people with and without a migration background is also important. As Borggrefe and Cachay (Citation2018), in line with Duemmler (Citation2015), have determined for VSCs, it is not the actual social differences between the groups that are relevant. Rather, it is crucial how ethnic and cultural classifications are constructed in social processes as ‘symbolic boundaries’ (Duemmler Citation2015).

Furthermore, in the case of VSCs, which are only slightly formalized organizations, the influence of individual actors is of central importance for the willingness to engage in integration work and the associated structural changes. Studies suggest that organizational change in VSCs is driven much more by changes in membership structures than by external interventions such as subsidies (Emrich, Gassmann, and Pierdzioch Citation2017). The inclusion of migrants as members can be a catalyst for further integration processes and increase cultural diversity in VSCs. This can be achieved on the one hand, by migrants initiating processes and initiatives in the club. On the other hand, by strengthening the sense of belonging of both groups through interethnic interactions and relationships between people with and without a migration background. In contrast, the negative attitude of individual autochthonous members, especially if they have taken on an important role in the VSC, can hinder the willingness to implement integration work and perpetuate assimilative ideas (Seiberth, Weigelt-Schlesinger, and Schlesinger Citation2013; Seiberth and Thiel Citation2010).

Ability is related to the deployment and allocation of assets and resources (capacities) within the club to achieve their goals. The concept of organizational capacity in general (Hall et al. Citation2003) has proven to be a viable approach in research of VSCs (Doherty and Cuskelly Citation2020), in particular for analysing and explaining implementation and development processes for various issues (Wicker and Breuer Citation2013). The ability of VSCs to provide integrative services for migrants depends on the underlying structures and processes and their flexibility and ability to adapt (Tuchel et al. Citation2021). Despite an interest in being an active partner, planned activities are seldom introduced because VSCs lack the required infrastructure and personnel resources (Anderson et al. Citation2019). Human resources are of great importance for VSCs. Competencies, knowledge, attitudes and the behaviour of employees and members – with and without a migration background – represent a central resource for integration work. Intercultural competencies and experiences of the autochthonous members are of particular importance in this context (Anderson et al. Citation2019; Seiberth, Weigelt-Schlesinger, and Schlesinger Citation2013). Since VSCs can vary in terms of their size, goals, resources and capacities, it can be assumed that clubs might create different forms and practices to integrate migrants into their existing sports and social services (Stenling and Fahlén Citation2016).

Intended and unintended consequences at the club level

The extension of the multi-level framework to a sequential model enables the consideration of intended and unintended consequences of social integration, which is a neglected aspect in extant research. Accordingly, we conceptualize VSCs as ‘social entities’. This means that we consider every activity of the organization as having a potential impact on both the club members and on the club itself (Nagel et al. Citation2015). In practice, these two levels are mutually dependent and should not be viewed in isolation. On the one hand, changes can occur at the club level (e.g. changes in the club’s goals and the allocation and redistribution of resources) that affect the members and their interests. On the other hand, changes in the actions and behaviour of the members (e.g. increased willingness to volunteer) can have an impact on the structures of the VSCs. However, regardless of these recursive interrelations of structures and actions (Giddens Citation1984), both levels should be considered separately from an analytical perspective whereby the intended and unintended consequences for the club are the focus at the meso level.

VSCs are social systems that reproduce themselves by decision-making (Thiel and Mayer Citation2009), where organizational structures and practices are not only a result of strategies and active management, but also emerge from these processes (Ortmann Citation2010). This is accompanied by the question as to which structural or personal conditions promote or hinder the development of new characteristics or structures in VSCs. In this context, the (observable) properties of the clubs as a social entity should not just be reduced to the properties of their elements (actors), which they exhibit when viewed in isolation (problem of emergence, Sawyer Citation2005).

The consequences of getting involved in targeted integration practices may be structural, cultural or social. Accordingly, organizational features such as new power constellations and conflicts regarding the distribution of resources emerge and become evident only in the interaction with other elements of the organization (Ortmann Citation2010). The consequences of organizational adaptations therefore remain uncertain. Attempts to mitigate unintended consequences could also cause other effects and initial issues might increase rather than decrease. For instance, new sports activities may be offered but facilities may need to be shared; new sport teams may be created but resources may become more scarce; club life may become more interesting and diverse but valued routines and traditions may change. Therefore, the approach also reflects actions during the processes of social integration in relation to intended and unintended consequences, particularly if there are developments that could have an overburdening or jeopardizing effect. It is particularly worth investigating whether, and to what extent, organizational capacities (Doherty and Cuskelly Citation2020) could potentially change as a result of engaging with the integration of migrants.

Relevance of the micro level: social integration of migrants and consequences of change for club members

It is important to distinguish between integration in sport and integration through sport. Integration in sport represents participation and the feeling of affiliation within the realm of the VSC. Integration through sport represents the link between participation and the feeling of affiliation within the realm of the VSC on the one hand and integration into other areas of society on the other (Elling, De Knop, and Knoppers Citation2001). Thus, integration through sport refers to the transfer of the integrative effects of the VSCs to other areas of life in the host society.

In view of the complexity of the construct of social integration, the division of social integration into different dimensions is helpful. In this regard, Esser (Citation2009) distinguished four dimensions: culturation, placement, interaction and identification. Culturation implies the acquisition of knowledge and cultural techniques that are necessary for meaningful actions within the society. Placement involves access to and adoption of positions and rights within certain societal structures. Interaction describes the embeddedness in functioning (interethnic) social relations in the private realm, participation in public and political life, and the development of social acceptance. Identification refers to the subjectively perceived sense of belonging and emotional attachment to the receiving society. All dimensions are interdependent, which is in line with a multidimensional integration approach (Esser Citation2009). Our approach follows Esser’s (Citation2009) conceptualization of social integration and makes specific references to the social setting of VSCs, as pointed out and validated by Adler Zwahlen, Nagel, and Schlesinger (Citation2018).

Social integration of migrants into VSCs

To communicate and act in compatible ways, we argue that members need to be able to draw on knowledge concerning club-specific norms and routines, as well as the underlying cultural self-image of community. Culturation plays a key role in this and represents a special form of learning and internalizing established club-specific patterns of communication and collectively shared activity orientations (Schlesinger, Egli, and Nagel Citation2013). In VSCs with members from different cultural backgrounds, there can be a multicultural climate. This, however, requires that the co-existence of these cultures is accepted by members. If this is the case, members can be socially integrated even if they have not been assimilated into the dominant culture (given that a dominant culture exists).

The placement dimension deals with the question of whether a member is prepared to become actively involved in shaping certain conditions for work within the club. Also, it deals with the possibility to participate in the development of club policies or take on certain tasks on a voluntary basis (Schlesinger, Faß, and Ehnold Citation2020). Particularly through taking on positions and tasks, migrants can increase the VSC’s readiness for integration work itself. In addition, they can strengthen the VSC’s resources through their specific knowledge or by refreshing existing networks.

The interaction dimension addresses a wide range of starting points for repeatedly taking part in sporting activities in an ethnically mixed sports group before, during and after training. Interaction constellations are characterized by their intercultural character by virtue of the fact that members with different (i.e. also without) migration biographies come into contact with each other. Additionally, the aspect as they let themselves be guided by each other through their sport-specific know-how, act accordingly and thereby gain acceptance. Notwithstanding this high potential for contact, a key issue is the extent to which the (accepted) membership role is implicitly associated with mechanisms for setting up social differences along the criterion of ‘ethnicity’ (Kleindienst-Cachay, Cachay, and Bahlke Citation2012).

In the identification dimension members establish emotional and mental relationships with the social setting of the VSC as a ‘social collective’. The more members feels that they belong to the club and can position themselves there due to their cultural self-positioning and their specific sports and exercise habits, the more the club will become an important part of their life and an identity vehicle (Schlesinger, Egli, and Nagel Citation2013). Accordingly, feelings of social and emotional identification may develop within a club (Elling and Claringbould Citation2005).

The integration dimensions used also allow conclusions to be drawn about the extent to which migrants orient themselves towards their culture of origin or the host culture. According to Berry (Citation1990), four basic strategies of acculturation are possible. Integration focuses on maintaining the culture of origin as well as adapting to the host culture. In contrast, assimilation shows little to no emphasis on maintaining the culture of origin. Adopting the language, thought and behaviour patterns of the new cultural system leads to a gradual overshadowing of cultural identity. However, through segregation, their own cultural values and thought patterns are maintained without any contact with the majority culture. In marginalisation, existing cultural identities are broken down and there is also an aversion to the host culture.

Social integration of migrants into other areas of society through VSCs

The dimensions of social integration described above (Esser Citation2009), as well as the various acculturation strategies (Berry Citation1990), are also relevant for integration into other areas of society. In addition, we argue that the following aspects must be taken into account:

Integration (into other areas of society) is influenced by the characteristics and competencies of the individuals involved in the integration processes. Age, ethnicity and gender are important, as are economic and human resources (Block and Gibbs Citation2017).

Tho what extent integration processes take place in other areas of society depends on the background and situation of the migrants. Research has shown that the flight, journey, intermediate destinations, arrival, duration and uncertainty about the outcome of application processes could all factor into how the involved actors understand their situation and the incentives that drive the integration process (Phillimore Citation2021).

Social capital is of particular importance. This can be built up or expanded as part of membership in VSCs (Smith, Spaaij, and McDonald Citation2019; Spaaij Citation2012). Social capital and network perspectives distinguish three ways that social relations might help individuals and societies. Firstly, participation in sports could contribute to the development of strong social ties to others – bonding – which first and foremost could provide social support. Secondly, the outcome of sports club participation could be weak social ties – bridging – which primarily provide useful information and new acquaintances. Such social capital could be helpful for gaining entrance into other institutions – labour market, the local community – and getting information about the relevant competencies in these institutions (Ager and Strang Citation2008; Putnam Citation2001). Thirdly, the focus in social capital analyses is often on how social capital helps social interaction through trust and social norms. The idea is that participation in VSCs, with the numerous opportunities for sporting and social interaction that they offer, involves cooperation between migrants and non-migrants. This leads to a feeling of reciprocal trust and an experience of reciprocal expectations (Burrmann, Braun, and Mutz Citation2019).

Intended and unintended consequences for autochthonous club members

Regardless of whether members of VSCs pursue more purpose-oriented interests, mostly related to taking part in sports activities, or membership is more value-oriented and aimed at social interaction (Schlesinger and Nagel Citation2015). We argue that proactive integration initiatives of the club will affect the interests of the respective individual members. The effect can be perceived by members as being more beneficial or more of a hindrance to their own interests. Migrants increase the resources of VSCs by paying membership fees and working as volunteers. Working as a coach or being active as an athlete supports the creation of sport-related services. They therefore have a positive effect on the perception of the interests of (autochthonous) members, whereby the interests of members who are primarily focused on competitive sport can also be addressed if the migrants have specific competences related to competitive sport.

Furthermore, social interaction with migrants can strengthen the intercultural competences and cohesion of all members and influence their life satisfaction (Akay et al. Citation2017). Therefore, migrant integration and cultural diversity can be a productive resource for the VSC. Direct consequences do not necessarily have to be observable. However, it can be assumed that in the event of convergence, for example, identification with the VSC will be high, which in turn promotes the stability of membership (Schlesinger and Nagel Citation2015) as well as the willingness to volunteer (Schlesinger and Nagel Citation2018).

However, the integration work of a VSC can also clash with the individual goals of members. The effects of divergences in interests depend on the reaction of the club as well as the respective member (Klenk and Nagel Citation2012). Should divergences arise, the reaction of the members can be classified as exit (exit, withdrawal), voice (opposition, protest), loyalty (connectedness) or neglect (indifference, disinterest) according to the EVLN action typology developed by Hirschmann (Citation1970).

Conclusion: perspectives on the practical and analytical application of the multi-level framework

In order to increase the number of VSCs that are willing and able to implement targeted integration initiatives for migrants, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of how ‘integration through sport policies’ reach sports clubs in the first place, how they are implemented there and the consequences they entail for the clubs and the target group. The fundamental dimensions of the implementation of integration programmes have been theoretically located in the multi-level model outlined and their interrelationships presented. The elaborated multi-level framework thus enables a comprehensive analysis of integration programmes by systematically interlocking different levels of analysis. At the same time, the necessary practice-specific research of such implementations can be sufficiently realized – independent from the scope of such programmes. The preceding considerations regarding the complex interrelationships and the necessity of adopting multi-level perspectives should have made it clear that implementation processes for integration programmes can be considered at the local level (e.g. in municipalities) just as much as in the national or international context.

The multiple use of the framework model opens up the option of generating differentiated empirical findings from which both programme planners (e.g. federations) as well as practitioners in VSCs can benefit with regard to integration work through adequate sports policy translation. In the following section, the applicability of the multi-level framework is related to the central issues already addressed in the context of the topic of integration of migrants in VSCs, and points of contact for empirical analyses are outlined. Although the points of contact are presented individually, they should be handled in an integrative manner in the empirical analysis, as this is the only way to fully utilize the advantages of the multi-level model with regard to a holistic approach to implementation processes.

Analysis of integration programmes (macro-level): Future research should focus on which regional, national or international integration programmes exist for VSCs. It is important to analyse which institution sets up the programmes, who the recipients of the programmes are, how the programmes are designed and which roll-out strategy is pursued. Furthermore, the different contextual conditions such as societal and migration characteristics, migration policies or sport policies should be included in the analysis. Comparative analyses can be carried out between different regions within a country as well as between different countries. International analyses in particular make it possible to assess the influence of contextual conditions on the strategic and operational design of integration programmes in VSCs. As previous studies already suggest a connection between sports policies and sports systems (Bergsgard et al. Citation2009; Breuer et al. Citation2015; Scheerder and Claes Citation2017). In addition, integration programmes can be expected to differ depending on whether the country is more of a transit or destination country for migrants, as the (planned) length of stay of migrants differs between countries. This likely results in different integration needs, which should also have an impact on the relevance and design of integration programmes.

Analysis of implementation strategies for integration programmes as well as bottom-up integration initiatives (meso level): Political programmes and thus integration programmes are not simply implemented by VSCs but go through internal processes. They are reprocessed according to internal logic (Fahlén, Eliasson, and Wickman Citation2015; Garrett Citation2004; Skille Citation2008; Stenling Citation2013; Stenling and Fahlén Citation2016). Empirical studies should focus on the extent to which commonalities and differences in implementation emerge depending, for example, on the type of programme, external incentives or structural conditions (club goals, resources) as well as the commitment of members. It is therefore necessary to analyse which adaptation strategies and practices can be distinguished from each other and which mechanisms/factors influence them. Studies can put the focus on programmes within a single country and across countries. The effect of different structural conditions can be captured above all in international studies, as stronger differences between clubs can be found here than within a country (Breuer et al. Citation2015; Nagel et al. Citation2020a). Another interesting aspect is the analysis of integration initiatives that are not directly related to politically initiated integration programmes, but rather were initiated by the club in a self-dynamic way from within (bottom-up) (Breuer et al. Citation2017).

Analysis of the consequences of integration efforts for the VSC (meso level) as well as for the members (micro level): The impact that a social commitment can have beyond sports-related tasks on the VSC as an organization and on its members must be taken much more into account. Both levels can initially be considered in isolation. However, our framework allows for multi-level analyses, which can generate insights into interactions between the club structure and the member level. Because actions and the impact on members are not only related to individual data (analysis of differences between individuals), but also to corresponding structural data (Schlesinger and Nagel Citation2015, Citation2018). Accordingly, it can be assumed that the observable consequences of the actions of members within a VSC are more similar than for members of different clubs. In addition, a differentiation can be made according to whether the integration initiatives are more strongly connected to an official integration programme (top-town) or rather initiated by the club itself (bottom-up).

Analysis of the consequences of integration programmes and initiatives for migrants (micro level): ‘Migrant’ is a container term applied for a wide range of very diverse groups with different cultural, linguistic, religious, social backgrounds and identity (Seiberth, Thiel, and Spaaij Citation2019). This is reflected in their different values, preferences and attitudes (Tucci and Statistisches Bundesamt 2013). No such differentiation is made within the framework. Rather, the framework is intended to be used comprehensively as an overarching analytical tool. However, empirical studies need to take into account the heterogeneity of migrants in order to examine specific situations for each migrant group. In this context, it is also important to pay more attention to the interaction between ethnicity and gender (Massao and Fasting Citation2014). Therefore, the framework needs to be specifically adapted for an empirical analysis of migrant groups (e.g. Muslim women, children, war refugees) and the corresponding structural conditions. The heterogeneity of migrants must be considered when analysing expectations of club membership and evaluating the consequences of integration programmes and initiatives. Furthermore, the research design has to be adapted to specific cases due to differences between and within migrant groups. Depending on the situation, observations, individual interviews, focus group interviews or group discussions are used. The emphasis can be placed on a rather homogeneous group, which can be implemented in the context of municipal studies. Stronger differences between migrants (e.g. with regard to country of origin, ethnicity, reason for migration, migration experience), on the other hand, can be mapped above all in the context of international studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adler Zwahlen, J., S. Nagel, and T. Schlesinger. 2018. “Analyzing Social Integration of Young Immigrants in Sports Clubs.” European Journal for Sport and Society 15 (1): 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2018.1440950

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Agergaard, S. 2011. “Development and Appropriation of an Integration Policy for Sport. How Danish Sports Clubs Have Become Arenas of Ethnic Integration.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 3 (3): 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2011.596158

- Akay, A., A. Constant, C. Giulietti, and M. Guzi. 2017. “Ethnic Diversity and Well-Being.” Journal of Population Economics 30 (1): 265–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0618-8

- Anderson, A., M. A. Dixon, K. F. Oshiro, P. Wicker, G. B. Cunningham, and B. Heere. 2019. “Managerial Perceptions of Factors Affecting the Design and Delivery of Sport for Health Programs for Refugee Populations.” Sport Management Review 22 (1): 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.015

- Baker-Lewton, A., C. Sonn, D. N. Vincent, and F. Curnow. 2017. “I Haven’t Lost Hope of Reaching out…’: Exposing Racism in Sport by Elevating Counternarratives.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (11): 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1350316

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.-L. 2007. “Introduction: Policy Instrument Choice and Evaluation.” In Carrots, Sticks & Sermons. Policy Instruments & Their Evaluation, edited by M.-L. Bemelmans-Videc, R. C. Rist, and E. Vedung, 4th ed., 1–19. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Bergsgard, N. A., B. Houlihan, P. Mangset, S. I. Nødland, and H. Rommetvedt. 2009. Sport Policy. London: Routledge.

- Berry, J. W. 1990. “Psychology of Acculturation: Understanding Individuals Moving between Cultures.” In Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology, edited by R. Brislin, 232–253. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Block, K., and L. Gibbs. 2017. “Promoting Social Inclusion through Sport for Refugee-Background Youth in Australia: Analysing Different Participation Models.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 91–100. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.903

- Borggrefe, C., and K. Cachay. 2018. “The Social selectivity of certain Sports with Regard to German Migrants Theoretical Reflections Using Handball as an Example.” “European Journal for Sport and Society 15 (3): 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2018.1484022

- Borggrefe, C., and K. Cachay. 2021. “Interkulturelle Öffnung von Sportvereinen – Theoretische Überlegungen und Empirische Ergebnisse [Intercultural Opening of Sports Clubs – Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Results].” Sport Und Gesellschaft 18 (2): 157–186. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2021-0013

- Breuer, C., S. Feiler, R. Llopis-Gog, and K. Elmose-Østerlund. 2017. “Characteristics of European sports clubs. comparison of the structure, management, voluntary work and social integration among sports clubs across ten European countries.” Accessed July 2, 2023. https://www.sdu.dk/en/om_sdu/institutter_centre/c_isc/forskningsprojekter%20/sivsce/-/media/f16c3e0c48414f659e8bcd9cad2107b0.ashx.

- Breuer, C., R. Hoekman, S. Nagel, and H. van der Werff. 2015. Sport Clubs in Europe. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Broerse, J., and R. Spaaij. 2019. “Co-Ethnic in Private, Multicultural in Public: Group-Making Practices and Normative Multiculturalism in a Community Sports Club.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 40 (4): 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2019.1628724

- Burrmann, U., S. Braun, and M. Mutz. 2019. “Playing Together or Bowling Alone? Social Capital-Related Attitudes of Sports Club Members and Non-Members in Germany in 2001 and 2018.” European Journal for Sport and Society 16 (2): 164–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2019.1620412

- Caperchione, C., G. Kolt, R. Tennent, and W. K. Mummery. 2011. “Physical Activity Behaviours of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Women Living in Australia.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-26

- Coleman, J. S. 1974. Power and the Structure of Society. New York: Norton.

- Dagkas, S., and T. Benn. 2006. “Young Muslim Women’s Experiences of Islam and Physical Education in Greece and Britain: A Comparative Study.” Sport, Education and Society 11 (1): 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320500255056

- De Bruijn, A. A., and A. M. Hufen. 1998. “A Contextual Approach to Policy Instruments.” In Public Policy Instruments. Evaluating the Tools of Public Administration, edited by B. G. Peters, and F. K. M. van Nispen, 47–69. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Doherty, A., and G. Cuskelly. 2020. “Organizational Capacity and Performance of Community Sport Clubs.” Journal of Sport Management 34 (3): 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0098

- Doherty, A., and T. Taylor. 2007. “Sport and Physical Recreation in the Settlement of Immigrant Youth.” Leisure/Loisir 31 (1): 27–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2007.9651372

- DOSB. 2022. “Integration durch Sport. Unsere Vereine [Integration through Sport. Our Clubs].” Accessed July 2, 2023. https://integration.dosb.de/inhalte/service/stuetzpunktvereine

- Dowling, F. 2020. “A Critical Discourse Analysis of a Local Enactment of Sport for Integration Policy: Helping Young Refugees or Self-Help for Voluntary Sports Clubs?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 55 (8): 1152–1166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690219874437

- Duemmler, K. 2015. “Symbolische Grenzen - Zur Reproduktion sozialer Ungleichheit durch ethnische und religiöse Zuschreibungen [Symbolic Borders - On the Reproduction of Social Inequality through Ethnic and Religious Attributions]. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Dukic, D., B. McDonald, and R. Spaaij. 2017. “Being Able to Play: Experiences of Social Inclusion and Exclusion Within a Football Team of People Seeking Asylum.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 101–110. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.892

- Elling, A., and I. Claringbould. 2005. “Mechanisms of Inclusion and Exclusion in Dutch Sports Landscape: Who Can and Wants to Belong?” Sociology of Sport Journal 22 (4): 498–515. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.22.4.498

- Elling, A., P. De Knop, and A. Knoppers. 2001. “The Social Integrative Meaning of Sport: A Critical and Comparative Analysis of Policy and Practice in The Netherlands.” Sociology of Sport Journal 18 (4): 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.18.4.414

- Elmose-Østerlund, K., B. Ibsen, S. Nagel, and J. Scheerder. 2020. “The Contribution of Sports Clubs to Public Welfare in European Soccieties. A Cross-National Comparative Perspective.” In Functions of Sports Clubs in European Societies. A Cross-National Comparative Perspective, edited by S. Nagel, K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, and J. Scheerder, 345–385. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Emrich, E., F. Gassmann, and C. Pierdzioch. 2017. “Steuerung von Vereinswandel zwischen individuellen Interessen und äußerem Druck [Managing change between individual interests and external pressures in Clubs].” In Der Sportverein – Versuch einer Bilanz, edited by L. Thieme, 295–334. Schorndorf: Hofmann.

- Engh, M. H., F. Settler, and S. Agergaard. 2017. “The Ball and the Rhythm in Her Blood: Racialised Imaginaries and Football Migration from Nigeria to Scandinavia.” Ethnicities 17 (1): 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796816636084

- Esser, H. 1993. Soziologie. Allgemeine Grundlagen [Sociology. General basics]. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

- Esser, H. 2009. “Pluralisierung oder Assimilation? Effekte der multiplen Inklusion auf die Integration von Migranten [Pluralisation or Assimilation? Effects of Multiple Inclusion on Integration of Migrants.” Zeitschrift Für Soziologie 38 (5): 358–378. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2009-0502

- European Commission. 2022. “Erasmus + Project Results.” Accessed July 2, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/#search/project/keyword=integration%2520migra*%2520sport%25202020&options[0]=ongoing&activityYears[0]=2020&matchAllCountries=false.

- Fahlén, J., and C. Stenling. 2022. “Mapping of context, policies and programmes. Integration of newly arrived migrants through organised sport – from European policy to local sports club practice (INAMOS).” Accessed July 3, 2023. https://inamos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/INAMOS_Mapping_Context_WP2.pdf.

- Fahlén, J., I. Eliasson, and K. Wickman. 2015. “Resisting Self-Regulation: An Analysis of Sport Policy Programme Making and Implementation in Sweden.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 7 (3): 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2014.925954

- Garrett, R. 2004. “The Response of Voluntary Sports Clubs to Sport England’s Lottery Funding: Cases of Compliance, Change and Resistance.” Managing Leisure 9 (1): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360671042000182973

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Guerin, P. B., R. O. Diiriye, C. Corrigan, and B. Guerin. 2003. “Physical Activity Programs for Refugee Somali Women: Working out in a New Country.” Women & Health 38 (1): 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v38n01_06

- Hall, M. H., A. Andrukow, C. Barr, K. Brock, M. De Wit, and D. Embuldeniya. 2003. The capacity to serve: A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

- Harris, S., K. Mori, and M. Collins. 2009. “Great Expectations: Voluntary Sports Clubs and Their Role in Delivering National Policy for English Sport.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 20 (4): 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9095-y

- Hirschmann, A. 1970. Exist, Voice, and Loyalty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Jeanes, R., J. O’Connor, and L. Alfrey. 2015. “Sport and the Resettlement of Young People From Refugee Backgrounds in Australia.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 39 (6): 480–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514558929

- Kleindienst-Cachay, C., K. Cachay, and S. Bahlke. 2012. “Inklusion und Integration.” In Eine Empirische Studie zur Integration Von Migrantinnen und Migranten im Organisierten Sport [Inclusion and Integration. An Empirical Study on Integration of Migrants in Organised Sports]. Schorndorf: Hofmann.

- Klenk, C., and S. Nagel. 2012. “Freiwillige Sportorganisationen als Interessenorganisationen?! Ursachen und Auswirkungen Von Ziel-Interessen-Divergenzen in Verbänden und Vereinen [Voluntary Sports Organisations as Interest Organisations].” Sport Und Gesellschaft 9 (1): 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2012-0102

- Knoppers, A., and A. Anthonissen. 2001. “Meaning Given to Performance in Dutch Sport Organizations: Gender and Racial/Ethnic Subtexts.” Sociology of Sport Journal 18 (3): 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.18.3.302

- Krouwel, A., N. Boonstra, J. W. Duyvendak, and L. Veldboer. 2006. “A Good Sport?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 41 (2): 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690206075419

- Lascoumes, P., and P. Le Galès. 2007. “Introduction: Understanding Public Policy through Its instruments - From the Nature of Instruments to the Sociology of Public Policy Instrumentation.” Governance 20 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00342.x

- Lundkvist, L., S. Wagnsson, L. Davis, and A. Ivarsson. 2020. “Integration of Immigrant Youth in Sweden: Does Sport Participation Really Have an Impact?” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25 (1): 891–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1775099

- Makarova, E., and W. Herzog. 2014. “Sport as a Means of Immigrant Youth Integration: An Empirical Study of Sports, Intercultural Relations, and Immigrant Youth Integration in Switzerland.” Sportwissenschaft 44 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-013-0321-9

- Massao, P. B., and K. Fasting. 2014. “Mapping Race, Class and Gender: Experiences from Black Norwegian Athletes.” European Journal for Sport and Society 11 (4): 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2014.11687971

- May, T., S. Harris, and M. Collins. 2013. “Implementing Community Sport Policy: Understanding the Variety of Voluntary Club Types and Their Attitudes to Policy.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 5 (3): 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2012.735688

- McDonald, B., R. Spaaij, and D. Dukic. 2019. “Moments of Social Inclusion: Asylum Seekers, Football and Solidarity.” Sport in Society 22 (6): 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1504774

- Mutz, M., U. Burrmann, and S. Braun. 2022. “Speaking Acquaintances or Helpers in Need: Participation in Civic Associations and Individual Social Capital.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 33 (1): 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00274-x

- Nagel, S., K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, and J. Scheeder. 2020a. Functions of Sports Clubs in European Societies. A Cross-National Comparative Perspective. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Nagel, S., K. Elmose-Østerlund, J. Adler Zwahlen, and T. Schlesinger. 2020b. “Social Integration of People with Migration Background in European Sports Clubs.” Sociology of Sport Journal 37 (4): 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2019-0106

- Nagel, S., T. Schlesinger, P. Wicker, J. Lucassen, R. Hoekmann, H. van der Weerf, and C. Breuer. 2015. „“Theoretical Framework.” In Sport in Europe. A Cross-National Comparative Perspective, edited by C. Breuer, R. Hoekman, S. Nagel, and H. van der Werff, 14–36. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Nobis, T., C. Gomez-Gonzalez, C. Nesseler, and H. Dietl. 2022. “(Not) Being Granted the Right to belong-Amateur Football Clubs in Germany.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 57 (7): 1157–1174. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211061303

- Nowy, T., S. Feiler, and C. Breuer. 2020. „“Investigating Grassroots Sports Engagement for Refugees: Evidence From Voluntary Sports Clubs in Germany.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 44 (1): 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519875889

- O’Driscoll, T., L. K. Banting, E. Borkoles, R. Eime, and R. Polman. 2014. “A Systematic Literature Review of Sport and Physical Activity Participation in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Migrant Populations.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16 (3): 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9857-x

- Ortmann, G. 2010. “Organisation und Moral.” Die Dunkle Seite [Organisation and Moral. The Dark Side]. Weilerswist: Velbrück GmbH Bücher & Medien.

- Phillimore, J. 2021. “Refugee-Integration-Opportunity Structures: Shifting the Focus from Refugees to Context.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (2): 1946–1966. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012

- Putnam, R. D. 2001. Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Ramanathan, S., and P. Crocker. 2009. “The Influence of Family and Culture on Physical Activity among Female Adolescents from the Indian Diaspora.” Qualitative Health Research 19 (4): 492–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309332651

- Sawyer, R. K. 2005. Social Emergence. Societies as Complex Sytems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scheerder, A. W., and E. Claes. 2017. Sport Policy Systems and Sport Federations. A Cross-National Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schlesinger, T., and S. Nagel. 2015. “Does the Context Matter? Analysing Individual and Structural Factors of Member Commitment in Sports Clubs.” European Journal for Sport and Society 12 (1): 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2015.11687956

- Schlesinger, T., and S. Nagel. 2018. “Individual and Contextual Determinants of Stable Volunteering in Sport Clubs.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (1): 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216638544

- Schlesinger, T., B. Egli, and S. Nagel. 2013. “Continue or Terminate?’ Determinants of Long-Term Volunteering in Sports Clubs.” European Sport Management Quarterly 13 (1): 32–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2012.744766

- Schlesinger, T., E. Faß, and P. Ehnold. 2020. “The Relevance of Migration Background for Volunteer Engagement in Organised Sport.” European Journal for Sport and Society 17 (2): 116–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2020.1737423

- Scraton, S., J. Caudwell, and S. Holland. 2005. “Bend It like Patel. Centring ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Gender in Feminist Analysis of Women’s Football in England.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 40 (1): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690205052169

- Seiberth, K., A. Thiel, and R. Spaaij. 2019. “Ethnic Identity and the Choice to Play for a National Team: A Study of Junior Elite Football Players with a Migrant Background.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (5): 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1408460

- Seiberth, K., and A. Thiel. 2010. “Cultural Diversity, Otherness and Sport – Prospects and Limits of Integration.” In Migration, Integration and Health: The Danube Region, edited by H. C. Traue, R. Johler and, J. J. Gavrilovic, 189–203. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

- Seiberth, K., Y. Weigelt-Schlesinger, and T. Schlesinger. 2013. “Wie integrationsfähig sind Sportvereine? - Eine Analyse organisationaler Integrationsbarrieren am Beispiel von Mädchen und Frauen mit Migrationshintergrund [How Integrative Are Sports Clubs? An Analysis of Organisational Barriers through the Example of Girls and Women with Migration Background.” Sport Und Gesellschaft 10 (2): 174–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2013-0204

- Seippel, O. 2005. “Sport, Civil Society and Social Integration. The Case of Norwegian Voluntary Sport Organizations.” Journal of Civil Society 1 (3): 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448680500484483

- Skille, E. Å. 2008. “Understanding Sport Clubs as Sport Policy Implementers.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 43 (2): 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690208096035

- Skille, E. Å., and C. Stenling. 2018. “Inside-out and outside-in: Applying the Concept of Conventions in the Analysis of Policy Implementation through Sport Clubs.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (7): 837–853. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216685584

- Smith, R., R. Spaaij, and B. McDonald. 2019. “Migrant Integration and Cultural Capital in the Context of Sport and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 20 (3): 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0634-5

- Spaaij, R. 2012. “Beyond the Playing Field: Experiences of Sport, Social Capital, and Integration among Somalis in Australia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (9): 1519–1538. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.592205

- Spaaij, R. 2013. “Cultural Diversity in Community Sport: An Ethnographic Inquiry of Somali Australians’ Experiences.” Sport Management Review 16 (1): 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.06.003

- Spaaij, R. 2015. “Refugee Youth, Belonging and Community Sport.” Leisure Studies 34 (3): 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.893006

- Stenling, C. 2013. “The Introduction of Drive-in Sport in Community Sport Organizations as an Example of Organizational Non-Change.” Journal of Sport Management 27 (6): 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.6.497

- Stenling, C., and J. Fahlén. 2016. “Same Same, but Different? Exploring the Organizational Identities of Swedish Voluntary Sports: Possible Implications of Sports Clubs Self-Identification for Their Role as Implementers of Policy Objectives.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 51 (7): 867–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214557103

- Stichweh, R. 2000. “Die Weltgesellschaft.” Soziologische Analysen. [World Society. Sociological Analyses]. Frankfurt/M: Suhrkamp.

- Stride, A. 2014. “Let Us Tell You! South Asian, Muslim Girls Tell Tales about Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (4): 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.780589

- Thiel, A., and J. Mayer. 2009. “Characteristics of Voluntary Sport Clubs Management: A Sociological Perspective.” European Sport Management Quarterly 9 (1): 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740802461744

- Thiel, A., K. Seiberth, and J. Mayer. 2018. Sportsoziologie [Sport Sociology], 2nd ed. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer.

- Tucci, I; Statistisches Bundesamt. 2013. “Lebenssituation von Migranten und deren Nachkommen [Life Situation of Migrants and Their Descendants].” In Datenreport: Vol. 2013. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, edited by Statistisches Bundesamt, 198–204. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Tuchel, J., U. Burrmann, T. Nobis, E. Michelini, and T. Schlesinger. 2021. “Practices of German Voluntary Sports Clubs to Include Refugees.” Sport in Society 24 (4): 670–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1706491

- Vedung, E. 2007. “Policy Instruments: Typologies and Theories.” In Carrots, Sticks & Sermons. Policy Instruments & Their Evaluation, edited by M.-L. Bemelmans-Videc, R. C. Rist, and E. Vedung, 4th ed., 21–58. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Wicker, P., and C. Breuer. 2013. “Understanding the Importance of Organizational Resources to Explain Organizational Problems: Evidence from Nonprofit Sport Clubs in Germany.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 24 (2): 461–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9272-2