Abstract

Despite an increase in published research investigating the development of sport for women and girls, to date there have been no attempts to review scholarly contributions rigorously and critically in this area. To address this issue, we first conducted an integrative review of research literature to portray an overarching and holistic picture of the field. Our comprehensive literature analysis following five-step process, provide evidence of the status quo of current research foci, authorship, theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and key research findings. Through this initial review, our study identified a distinct lack of intersectional representation of women and girls in the literature. As such, our focus shifted to a critical analysis and discussion of the intersectional works in the body of literature, calling to action for more thoughtful engagement with research participants, contexts, and foci. We conclude our study by providing new perspectives on key issues in research focused on developing sport for women and girls, and by outlining current research and theoretical gaps that provide the basis for future scholarly enquiry.

Introduction

Women are underrepresented in research. Caroline Perez (Citation2019) explains this phenomenon in her book Invisible women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men, highlighting a fundamental lack of women in critical research. From medical research, including the different effects certain drugs have on women’s bodies, to automobile safety testing and the use of male in crash test dummies – women are silenced and excluded within the collection and analysis of scientific and academic research. Perez (Citation2019, I) states that ‘the gender data gap isn’t just about silence. These silences, these gaps, have consequences. They impact on women’s lives every day’. Sport is a site where the society it is housed in is reproduced within it (Coakley, Hallinan, and McDonald Citation2011); it is unsurprising then that women are also underrepresented, excluded and silenced within different sport-focused research agendas. For example, Laxdal (Citation2023) found that there was a lack of sport and exercise medical research among women and it was generally left to women academics to perform this research.

When research relating to women and girls in sport is performed it is most often framed through a Whiteness, abled bodied and heteronormative lens and issues of participation dominate the research agendas (Knoppers Citation2015; McGarry Citation2020). This here presents two issues: 1) The reporting of sample populations does not account for diversity; 2) Understandings of the lived experience of women and girls from diverse backgrounds in sport is lacking. Thus, scholars have noted that sports research inquiries lack critical approach and adequate agendas to address issues concerning marginalized groups within sporting contexts. These underrepresented inquiries within sports research relate to issues of race and ethnicity (Armstrong Citation2011; Singer et al. Citation2022; Mowatt, French, and Malebranche Citation2013; Maxwell et al. Citation2017), disability (Cottingham et al. Citation2018; Pitts and Shapiro Citation2017; Clark and Mesch Citation2018), gender (Knoppers and McDonald Citation2010; Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006; Velija Citation2012), gender discrimination (Fink Citation2016; Kraft et al. Citation2022) and sexuality (Shaw and Cunningham Citation2021; Spaaij, Knoppers, and Jeanes Citation2020). The scarcity of critical research with marginalized groups prompted Frisby (Citation2005) to question if sport scholars are trained to ask these critical questions. Moreover, McGarry (Citation2020) has questioned the impact of research relating to women and girls in sport. In a similar observational vein, George Cunningham (Citation2014) has noted that the sport researchers tackling these issues tend to be from the marginalized groups in question. It could be argued that it is puzzling for the differing sports focussed social science and management disciplines to leave these critical investigations to members of these marginalized groups considering:

We all have a stake in ensuring sport is inclusive and socially just. We are all impacted, be it directly or indirectly, by structures, systems, and cultures that engender inequality. And as such, we are all equally bound to engage in collective action to ensure that sport is a space where all can be physically active, and where opportunities to be successful are not based on how we look … but on competencies and skill sets (Cunningham Citation2014, 1; emphasis added in original).

To address this first aim we undertook a qualitative analysis of the 40 intersectional papers in the sample of articles that had identified communities or groups, such as women of colour, women with a disability, Indigenous women, and queer, intersex or transwomen. It was in doing this work, we began to identify how significant the deficit for the inclusion of intersectional experiences is in sport management/sociology and other social science related disciplines. Notwithstanding, throughout our study we acknowledged the small group of scholars that have either performed research with these neglected spaces or called for similar research agendas to be formed as we are calling for. This prompted us to develop a second research aim: to amplify and add to call to action for sports scholars to increase their research agendas with intersectional women and girls in sport.

While we acknowledge that the underrepresentation of women and girls within sports research is widely known we argue that this research produces new knowledge on two counts. 1) While women and girls are underrepresented, as we will show, their neglect in the research is far worse than first expected. 2) Despite the findings of our study appearing self-evident we argue that research agendas are not changing, thus, we call on the academy to reflect on why knowledge is not shaping future research agendas as well as offering some recommendations to implementation. By addressing both research aims we shift the primary contribution of this paper from a simple review of the existing literature, to call attention – based on the empirical evidence provided in the reviewed articles – and highlight this concerning systemic approach to researching and reporting of women and girls in our fields. Finally, we outline research and theoretical gaps and offer a call to action for addressing these gaps.

Literature review

The literature that was searched and formed the intersectional data of this study was drawn from sport management, sport for development, sociology, gender and history research. Therefore, in presenting the background literature that has informed our argument we sourced studies across these disciplines. Hence throughout the paper we refer to the body of scholarship as ‘sports research’. We acknowledge that each discipline has differing perspectives, applications and theoretical approaches. However, the goal of this literature review was to highlight the collective calls from these differing disciplines – which for the most part have gone unanswered – for increased intersectional research of women and girls in sport.

Intersectionality in sport development research

Intersectionality can challenge taken-for-granted normative assumptions of gender, sexuality, Whiteness and ableism (Knoppers et al. Citation2021; Simon et al. Citation2021) while also examining ‘the complex and different forms of inequality, oppression and discrimination and how they interact and overlap in multidimensional ways’ (Scraton Citation2018, 641). Crenshaw (Citation1991) conceptualized intersectionality to challenge social and legal thinking that race and gender were separate analytical concepts, highlighting that women of colour’s lived experience was a critical and divergent site of inquiry within the study of race and gender (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018). More importantly, ‘intersectionality is the recognition that powerful forces such as sexism, racism and classism are not independent of one another but are interacting forces’ (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018, 318). Adopting an intersectional lens allows the consideration of the lived experiences of marginalized groups through the recognition that multiple social constructions such as race, gender, sexuality, dis/ability and class intersect to create unique oppressions and disadvantages. As we will argue in this paper, intersectional approaches have been limited across sports research. Notwithstanding, there has been a small, but important number of intersectional research studies conducted. This has included investigations by LaVoi (Citation2016), McDonald (Citation2014) and Toffoletti and Palmer (Citation2017). All of these studies researched the sporting lived experiences of women and girls from diverse backgrounds. In the most part however, sports research has neglected intersectionality within its research agenda. To demonstrate this, we will highlight the many calls across disciplines, that scholars have made for increased intersectional sporting research agendas.

Intersectionality and race

Scholars have criticized sports research for its lack of critical inquiries into people of colour’s experiences within different sporting contexts. For example, Knoppers (Citation2015) has called for more research into racially discriminatory hiring practices within sport organizations. These calls remain salient in the wake of former Miami Dolphins head coach, Brian Flores’, filing of a 2022 class action against the National Football League (NFL) and several teams for discriminatory hiring practices (Singer et al. Citation2022). Moreover, in the 2011 Journal of Sports Management (JSM) special issue Armstrong (Citation2011) suggested that sport management needed to develop a racial and ethnic research agenda that acknowledged Whiteness’s pervasiveness within the discipline. To assess if Armstrong’s (Citation2011) calls had been acted upon, Singer et al. (Citation2022) conducted a systematic review to assess the decade long coverage of race-related research. The results revealed a lack of meaningful research, particularly concerning the lived experience of people of colour within sports research (Singer et al. Citation2022). Further research has supported Singer and colleague’s findings. For example, Mowatt, French, and Malebranche (Citation2013) highlight that black women in leisure studies research are either invisible or portrayed in stereotypical ways. There has also been scant research relating to Indigenous Australian women’s participation in sport (Maxwell et al. Citation2017). While Abdel-Shehid and Kalman-Lamb (Citation2017) have called for intersectional approaches focused on class, gender and race to help facilitate greater social inclusion in sport. This research is collectively challenging sports researchers to increase their attention on Black populations, while considering interlocking social categories of class and gender, and questioning normative discourses of heterosexuality, ableism, and Whiteness.

Intersectionality, gender and sexuality

Sports research in the past has lacked widespread theoretical application which supports critical approaches fostering impactful diversity research. Shaw and Frisby (Citation2006) suggest that sports scholars have opportunities to interrogate diversity issues through adopting feminist and poststructuralist research agendas. However, these theoretical approaches have yet to be fully accepted and adopted across different sports research approaches. Knoppers and McLachlan (Citation2018) undertook a systematic review of past sporting research to ascertain the deployment of different feminist theories. Knoppers and McLachlan (Citation2018) found a scarcity of gender-focused studies. Of the papers found, they evaluated the theory development used and while a selection of feminist theories had been operationalized, feminist queer theory was ‘largely ignored’ (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018, 172). This is a critical finding as feminist queer theory interrogates socially constructed norms and pre-existing binaries of heterosexual/homosexual, male/female and masculine/feminine (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018). Moreover, when gender is theorized within sports research it tends to be framed through traditional social theorizing of power and positionality. For example, Velija (Citation2012) looked at the power construction of English girls playing cricket and Butler (Citation2013) investigated the positionality of women in the British horse racing industry. The lack of queer and feminist theorization indicates that gender and sexuality sports research currently being conducted is in most parts framed from a heteronormative lens. Thus, to interrogate issues affecting marginalized groups, sports researchers need to question ‘the normality of prominent discourses in sport such as that of performance excellence and marketplace thinking and how the normality of these discourses is simultaneously gendered and sexualised’ (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018, 173), while being framed through a heteronormative and Whiteness lens (Simon et al. Citation2021). These critical concerns are apparent in past sport researcher’s framing of sexuality.

Sexuality within sports research has traditionally been shaped around masculinity and femininity, which is framed through a heteronormative lens that produces discourses of homophobia and exclusion – especially concerning men (Shaw and Cunningham Citation2021). Research has then suggested that there is little social acceptance for gay men and women in sport (Denison and Kitchen Citation2022). With this in mind, Shaw and Cunningham (Citation2021) conducted a scoping review of the existing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBT+) sport research between 1960 and 2020, and demonstrated that the scarcity of research in this area was exacerbated when these studies were broken down into disciplines. These results reinforce the view that within sport LGBT + people are kept ‘hidden and silenced’ (Lawley Citation2018, 157) and that this is ‘discriminatory, unhealthy, and unsustainable’ (Shaw and Cunningham Citation2021, 373). Thus, Shaw and Cunningham (Citation2021) are calling sport academics to expand their research agendas to include LGBT + people. Scholars have also called for increased research relating to homophobic behaviour within sport organizations with the goal to create greater diversity and inclusion (Spaaij, Knoppers, and Jeanes Citation2020), the merit of sporting organizations’ support of LGBT + diversity and inclusion programs (Storr Citation2021), and the marketing practices and opportunities, or lack thereof, of LGBT + sportspeople (Melton and MacCharles Citation2021). All of these concerns raised indicate a lack of diversity and inclusion within sport more generally that requires increased academic scrutiny. Disability is a further marginalized group underrepresented within sport management scholarship.

Intersectionality and disability

The lived experiences of people with disability within sport are arguably the most underrepresented research thread of the groups mentioned here. Sports disability research primarily focuses on participation at the elite international level with events such as the Paralympics (Pitts and Shapiro Citation2017), with very little focused on women and girls specifically. Making this point further are Clark and Mesch (Citation2018) who have conducted research with deaf women athletes. They note that while disabled women athletes’ participation has increased in recent years few research studies have looked at the lived experience of this community. Further research avenues yet to be fully explored among disabled athletes is the intersection of gender and disability across co-ed sports. Cottingham et al. (Citation2018) highlighted this underrepresented research avenue with their study of women power soccer players. In a review of the disability content taught in North American introductory sport management curriculums, Pitts and Shapiro (Citation2017) found that a mitigating factor for not including this content was a lack of research. Moreover, Knoppers and McDonald (Citation2010, 318) note that ‘scholars have infrequently applied an intersectional approach within the study of disability … and sport’. This is unsurprising, considering societal othering of disabled people seems to be normative and often unquestioned. For example, it took 15 years for disability advocates to change the name of Major League Baseball’s (MLB) injured player designation list. In 2018 the name of this – the Disabled List (DL) – was changed to a less discriminatory label: the Injured List (IL) (Hums et al. Citation2020). However, social media analysis performed on fans’ reaction to the change found that the renaming was seen as an attack on baseball history and was considered unnecessary (Hums et al. Citation2020). Thus, highlighting a lack of understanding of a person’s lived experience with a disability within sport and broader consideration for the harmful impacts of ableist language. With this lack of understanding from the able-bodied community towards disability in sport there are increasing opportunities for sport academics to expand their research agendas to include an array of disability and diversity inquiries within sport.

Our literature review has focused on publications that have performed similar aims to our study: Systematically interrogate the research agendas of women and girls in sport that intersect with race, gender, sexuality and disability. The literature presented here has found that the research agendas being adopted are often narrowly framed around a limited view of marginalized people driven by normalized discourses of Whiteness, maleness and heterosexuality. This is unsurprising as faculties researching issues pertaining to sport are predominantly populated by white identifying men, which ‘demonstrate[s] … [a] hierarchical power structure’ (Springer, Stokowski, and Zimmer Citation2022, 69) of academia. Nevertheless, as Cunningham (Citation2014, 3) reminds us: ‘justice and equality in sport will only be realized through our collective actions – not our silence’. Despite Cunningham (Citation2014) and others repeated calls for more significant (Cunningham, Wicker, and Walker Citation2021; Fink Citation2016; Singer et al. Citation2022) and impactful (McGarry Citation2020) diversity led inquiries, and the meaningful establishment of an intersectionality research agenda (Armstrong Citation2011; Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006; Simpkins, Velija, and Piggott Citation2022; Mowatt, French, and Malebranche Citation2013; Clark and Mesch Citation2018), these calls have, for the most part, been unanswered within sports research more generally. It is at this intersection that our study looks to highlight this gap in the literature and propose a call to action. A call to action for all sports researchers across the social science and management disciplines to expand their research agendas to include diverse women and girls – capturing the lived experience of this often-silenced community.

Research methodology

As noted earlier, this review followed the principles of Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) five-step process for an integrative review: (1) problem identification, (2) literature search, (3) data evaluation, (4) data analysis and (5) presentation (see also Schulenkorf, Sherry, and Rowe Citation2016). Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) five-step process was applied twice throughout the study. Firstly, to our literature review of the sporting research pertaining to women and girls and then a second time to our intersectionality sample which became the focus of our qualitative inquiries. Similar reviews have served as fruitful research to situate the corpus and approach of a research field such as Schulenkorf, Sherry, and Rowe (Citation2016) review of the sports for development literature, Evans and Pfister (Citation2021) and Burton (Citation2015) who performed systematic reviews on women in sport leadership positions.

Data collection

The literature search was conducted on two databases, SCOPUS and SPORTDiscus and included English-language peer-reviewed scientific articles published between January 2000 and December 2020.

Three concepts drove the identification of relevant articles: sports, development and women and girls. Specifically, the search aimed to identify articles that included the following terms in their title, abstract and/or key words: sport* NOT transport AND develop* AND (woman OR women* OR girl* OR female*).

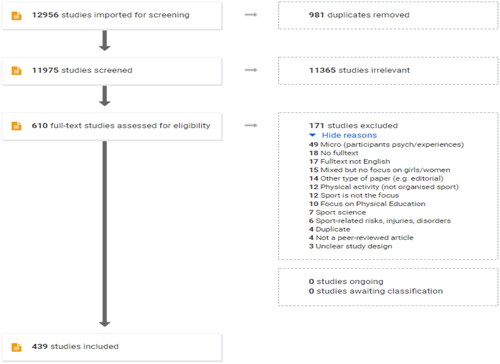

This search resulted in 12956 items across the two databases. These items were uploaded to Covidence, a software that assists the data evaluation process in systematic reviews. The Covidence software scans for and automatically deletes duplicated references. As a result, 981 duplicates were removed following upload of the items.

Data evaluation

The first step of the data evaluation process included screening the title and abstract of the 11957 articles to exclude those that were not related to the research topics: the development of sport for women and girls, and women and girls’ development through sport. The exclusion framework was guided by the need to capture the breadth and width of publications relating to women and girls in sport with a sport development and sport for development lens. The decision was also made to only include organized sport to keep the sport for development focus relating to community and to capture women and girls that are active agents with their sports engagement. Therefore, parameters were set to exclude mixed gendered studies, non-sport or peer reviewed studies and research with a health focus. A similar effective exclusion and inclusion criteria were used in the systematic review of the sport for development literature by Schulenkorf, Sherry, and Rowe (Citation2016). summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to determine the relevance of the studies. These criteria were employed to guide decisions about articles’ eligibility for the purpose of this study as well as to guide discussions between the researchers. Two independent researchers screened every article. If the two researchers did not reach consensus on the inclusion or exclusion of an article, a third researcher resolved the conflict following discussion with the two other researchers, using the list of criteria as reference. This process resulted in the exclusion of 11,365 articles and the inclusion of 610 studies for full-text screening. In the second step of the data evaluation process, two independent researchers read the studies’ full text to confirm their eligibility against the established criteria. As in step one of the data evaluations, a third researcher resolved the conflicts on the inclusion/exclusion of studies following discussion with the two other independent researchers. This process resulted in the exclusion of 171 additional studies. A final set of 439 studies was included in this review (see for the complete integrated review PRISMA chart).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the integrative review.

Data analysis

To analyse the sample of relevant studies, metadata were extracted from each 439 studies according to diverse categories (see ).

Table 2. The different categories that formed the analytical units of analysis for the empirical data generated.

For each category, a database was developed from the extracted data, and the data were examined to identify patterns and develop themes and sub-themes accordingly (see for an example).

Table 3. Offers an example of categories analysed from one randomly selected article of the sample.

These themes and sub-themes were then used to develop the main findings of this integrated review, which are presented in the following section.

Positionality and limitations

Reflecting on positionality, the authors of this paper acknowledge the privilege they hold as White and western researchers who have experienced western and colonial education and are trained in western methods of research. We each have our own lived experiences and bring our own diversities and experience of oppression including gender, ability, non-Anglo-Saxon nationality, survivor of child abuse – within our contributions here. However, we know that our experiences are not reflective of all. We must navigate our position, work on driving the inclusion of more voices in our own work and continue to learn from others. We ask, you, our colleagues to join us in this ongoing work.

Our individual positionality also brings to light the limitations of our methods in this study. We restricted the search to English speaking academic papers, while the systematic nature of the review relied on subjective categorization of each study. We acknowledge that the very nature of a systematic review privileges some knowledge and voices over others. Notwithstanding, the search parameters and exclusion criteria were based on past systematic reviews (Burton Citation2015; Evans and Pfister Citation2021; Schulenkorf, Sherry, and Rowe Citation2016) and offered an extensive understanding of the breadth and width of research pertaining to women and girls in sport. Despite the limitations we have detected in our method and positionality the findings that we will now present offer valuable and novel insights into the state of sports research pertaining to women and girls.

Findings

We will present our findings in two sections, first the overall findings from the larger data set to provide a broad understanding of the research identified within the review process. Moreover, these findings will highlight how women and girls have been framed as a homogenous population within the research. There is then a deeper analysis of the smaller sample of intersectionality focused research papers. This smaller data set and the qualitative analysis that was performed with it will form the analytical foundation of our discussion and call to action which concludes the article.

Overall data set

We will begin by presenting the critical findings from our analysis of the entire data set of literature published on women and girls within sporting research over the past 20 years (2000–2020). This will include highlighting key findings from the study populations, research foci, geographical and disciplinary location of the research and gender of the scholars responsible for the studies, rather than presenting analysis from every data category identified. Our literature search clearly highlighted the limited sport research pertaining to women and girls. While this was not unsurprising, the sheer lack of research was alarming and far worse than first anticipated (of the 11, 365 papers found in our search only 439 were focused on women and girls in sport). Moreover, what was even more striking and of concern was the lack of diversity – or presumed homogeneity – within the studies, with little to no consideration for including, investigation or referencing intersectional lived experiences of participants and their communities.

Study population and research focus

On analysing the findings of the literature reviewed, we found that the overwhelming number of studies treated women and girls in sport as a homogeneous analytical category. Of the 439 studies in the sample, 398 had a sample of ‘women’ (277), mixed gender (73) and ‘girls’ (39). This left only 40 studies that specifically identified their research participant population as anything other than generic ‘women’: women of colour (17), gender diverse (11), same sex attracted women (9) and women with disability (3), see . Further analysis of the focus of the studies was instructive in determining the level of depth in which women’s and girl’s sport research is taking place.

Table 4. The study populations from the sample (note the ‘other’ category featured studies with parents and children, media and content analysis and case studies with sport organizations).

The study focus category captured the main concepts of the reviewed papers. Many of the categories, displayed in , are self-explanatory like coaching, leadership, sport management and organizations. The main difference here was the Sport for Development research which attached development outcomes to the sporting programs in the study. All other categories were focused on participation, organization, leadership or lived experience – either at the micro (athlete) or the macro (organizational) level. This distinction is critical as Sport for Development has fundamentally different motivations and approaches than the other categorizations.

Table 5. The guiding analytical focus of the sample’s studies.

Participation and coaching of women and girls within sport took up 42% (183) of the study focus, see . This indicates that of the research being conducted, a majority is concerned with the participation of women and girls in sport – thus neglecting important empirical lines like the experiences of these women within different sporting settings, be that elite, collegiate, community or recreational levels. This here suggests that most research agendas are focusing on women and girls’ integration into sport, which is important, yet this is only one part of the sporting ecosystem. Thus, neglecting critical facets such as the sporting experience for women and girls and intersecting social constructions such as race, gender, sexuality, class and ableism.

Geographical and disciplinary approach

Further significant results from the interrogation of the literature sample were that these approaches to researching women and girls in sports are consistent across the globe. Half of the studies (213) were in either the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), Australia or Canada. At the same time, there were 37 other countries represented from diverse regions including Africa, Asia, the Pacific, South America and the Middle East. Moreover, there were 36 international or European studies. The majority (345) of studies took a sport development approach as opposed to just 88 which opted for a sport for development focus.

As demonstrated in our literature review it was expected that there would be a lack of sport management studies within the sample. However, interestingly we found that this is not a discipline-specific problem. Only 51% of the studies were in the field of sport management. In comparison, 34% took a sport sociology perspective. There were also studies from history and gender studies disciplines.

Gender identification of authors

The final significant data point detected was the gender of the authors. Over half of the authors were identified in the review as women (230), while 125 studies had mixed-gender authors. This left just 35 studies written by men (there were 51 studies in which gender of the authors were unverified due to the subjective nature of the data analysis). These findings pose the question: should there be a willingness for more male scholars to research women and girls within different sporting settings? We would argue that having more male scholars willing to carry out research with women and girls in sport would be one step in arresting the disparity of sporting research existing between men and women. Cunningham (Citation2014) supports this notion stating that it is the responsibility of all in society – not just women – to make sport as inclusive as possible regardless.

We have established that the studies from our sample relating to women and girls in sport generally lack diversity in their sample construction or study focus. Thus, presenting a perfunctory homogeneous view of women and girls in sport. The disregard for and lack of intersectionality research within the sample was critical to forming these conclusions. Therefore, the greater empirical focus of the dataset was with the intersectional research that had been completed in the twenty-year timeframe. Hence, the remainder of this findings section and discussion will focus on the intersectional data set.

Intersectional data set

In analysing the 40 studies that adopted an intersectional approach we identified four main foci: a) race, b) gender and sexuality, c) sex verification and d) disability, see Appendix 1 for a complete list of the studies. The most significant number of studies focused on race, ethnicity or religion – referred to in this study as women of colour (17). Religion was included in this category as it was analytically similarly to race and ethnicity within the sample through highlighting the experiences of difference and othering, for example see Ahmad and Thorpe (Citation2020). In contrast, 12 studies looked at LGBT + related issues for women and nonbinary athletes. The third category focused on the issues of sex verification within sport (8). Finally, only three studies looked at disability issues in women’s sport, see .

Table 6. The breakdown of intersectional studies from the sample.

A further interesting finding was that over the 20-year period, only ten studies were published between 2000 and 2010. While 50% of the intersectional studies have been produced since 2016, see .

Table 7. A breakdown of the time periods where the intersectional studies have been published.

This suggests that intersectional research studies being conducted among women and girls in sport is a relatively recent area of attention. This is both a cause for concern and a time to acknowledge the scholars challenging the status quo and producing intersectional women and girls sporting research. While the field will continue to require much intentional efforts to redress this lack of intersectional representation in sporting research, we must champion those who have and continue to produce work giving voice and legitimacy to communities who have not been adequately represented. Those who have been calling for action for far longer are the voices we must heed.

A further concern from the data is that, except for the US, which contributed to nine of the intersectional studies, there is a surprisingly low number of contributions from other Western countries. For example, Canada, Australia, the UK and New Zealand combined to contribute 11 studies. Moreover, an even split of disciplines was represented within the sample of intersectional research. Gender studies accounted for 12 papers, while sport sociology and sport management both respectively had 14. Out of the 12 gender studies, ten were focused on sex verification or LGBT + populations. Over half of the sport management studies (8) and sport sociology (7) studies focused on women of colour. This suggests that all disciplines must encourage more intersectional approaches to women’s sport research. Moreover, there is scope for sport management and sociology researchers to increase gender/sexuality research with women and girls in sport. A call that has been previously made by scholars including Shaw and Cunningham (Citation2021), Spaaij, Knoppers, and Jeanes (Citation2020), Storr (Citation2021) and Melton and MacCharles (Citation2021).

In keeping with the overall results of the literature review, women and mixed gender author teams accounted for 93% of the intersectional studies. This suggests that the intersectional representation of women and girls in sporting research almost exclusively relies on women to forward this agenda. Similar limitations in scope and focus were found when the breadth of these papers was inspected. Of the 40 studies, almost one-third are focused on either high-profiles sportspeople or driven by scholarly expertise. Three papers researching Muslim women’s experience within sport comes from two scholars (Ahmad and Thorpe Citation2020; Thorpe et al. Citation2022; Ahmad et al. Citation2020), and two studies use African American tennis player Serena Williams as their focus (Tredway Citation2020; Wilks Citation2020). At the same time, six articles focus on Caster Semenya and gender verification testing for athletes (Behrensen Citation2013; Camporesi and Maugeri Citation2010; Cooky and Dworkin Citation2013; Holzer Citation2020; Teetzel Citation2014; Wiesemann Citation2011). This indicates that 25% of the captured intersectional research relies on case studies of high-profile sportspeople. Moreover, athletics/track events were the most represented sport of the intersectional studies, which was directly influenced by the high volume of research about Semenya. The reliance on high profile athletes like Semenya and Williams to stimulate intersectional research of women and girls in sport further highlights the lack of consideration given more broadly to women of colour, LGBT+, and athletes with a disability across sporting research agendas.

Critically examining the complex exploitative issues around Semenya’s experiences, and the racialized and gendered commentary around Williams’ career is important to understand the impact of racism and sexism in elite sport. However, that these few studies are representative of the majority of intersectional sport research foci is a stark reminder of how many lived intersectional experiences are missing. Thus, it is critical to examine the central tenets and core message from our intersectional sample.

Discussion

Included in the 40 intersectional papers from our sample was the study by Ahmad and Thorpe (Citation2020) that focused on Muslim sportswomen and how they challenge taken for granted stereotypes relating to their religion and gender. This particular study gave us further cause for reflection. Ahmad and Thorpe (Citation2020) theorize that these women are space invaders within the sporting landscape. This is drawn from the work of Nirmal Puwar (Citation2004, 8), who states that:

Some bodies are deemed as having the right to belong, while others are marked out as trespassers, who are, in accordance with how both spaces and bodies are imagined (politically, historically, and conceptually), circumscribed as being ‘out of place’. Not being the somatic norm, they are space invaders.

We argue then that women from marginalized groups are not just space invaders within sporting settings and infrastructures – which is what many of the 40 papers in our sample have argued. They are also space invaders among the scholars and researchers that investigate, teach and publish in the different sports research disciplines highlighted in this study. Borland and Bruening (Citation2010) support this assertion, whose intersectional study of Black women head coaches in Division 1 US college basketball programs featured in our sample. Borland and Bruening (Citation2010, 418) state that:

[l]ittle research continues to exist on the experiences of Black sportswomen and other under-represented groups in sport, such as Asians and Hispanics … researchers, when looking at marginalised groups, have focused their efforts on examinations of Black males and White females.

This study is then indeed a call to action – for all sports scholars to consider expanding research agendas to include multiple voices framed through an intersectional lens.

Call to action and future research

There are many benefits to including marginalized voices within a sporting research agenda. Increased intersectional research can create an allyship among the academy and sporting community in which marginalized people’s voices can be heard and understood (Jolly, Cooper, and Kluch Citation2021; Teetzel Citation2020). Moreover, it has been suggested that societal stigmas surrounding people from intersectional positions could be a reason there is little research with these groups, as they often exclude themselves, because of social oppression, from the recruitment process (Ruddell and Shinew Citation2006). Greater collegiality and allyship within academia and sport more generally, could help alleviate this problem by including more diverse scholars and scholarship, and additionally educating scholars from different lived experiences as we continue to develop our own understandings of intersectionality through listening and learning from others.

Collegiality and collaboration indeed might be key as we work as an academy to redress this systemic exclusion of the intersectional experiences of all women and girls in sports research. With this kind of work, positionality and privilege are undeniably important considerations and can add complications to the ‘who’ and ‘should’ be doing this kind of work and maybe who should not. We can empathize how some scholars can find this an uncomfortable negotiation to find an appropriate space to act. However, as previously highlighted through the work of George Cunningham (Citation2014), we cannot sit back and let this work fall on those in our field from marginalized communities and with the lived experiences to do the heavy lifting for the academy alone. We see examples of this emotional labour to redress systemic exclusion by those from within these communities too often in research, as well as in industry (see Symons, Duncan, and Sherry Citation2022). The responsibility and privilege of change should be the responsibility of all scholars.

Further reasoning to act is that it cannot be forgotten that sport is a social institution. Therefore, to foster greater inclusion and equality within sport for marginalized women and girls, social change needs to take place outside the fields, courts, arenas and pitches of our sporting clubs (Harmon Citation2020). At this junction, our call for increased research agendas with these neglected groups can question the multiple discourses that intersect within sports contexts (Ravel and Rail Citation2007). For example, the problematic binaries of men/women (masculinity/femininity), heteronormative/homosexuality, ableism/disablism and different racial and religious categories. At this juncture, social researchers working within sport need to take the lead of the few we have mentioned here and challenge these taken for granted discourses and binaries within their research agendas. This needs to take place at the onset of entering the academy.

A critical site that can influence sport scholars’ research agendas is their formative years in the classroom. Curriculum across sport management and relevant social science departments must focus on questioning taken for granted activities and strive for inclusive practices (Cunningham Citation2014; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006). Moreover, institutional review panels for recruitment and promotion within these departments need to value and include a critical feminist lens into their teaching and research agendas (Knoppers and McLachlan Citation2018). In short, diversity needs to become a core tenet of a sporting academic curriculum. Springer, Stokowski, and Zimmer (Citation2022, 69) support these calls: ‘given the complexities within the sport context specifically, it is not enough for … educators to speak casually about equity and diversity; these constructs must become permanent fixtures within … education’. Therefore, we implore sporting faculty heads of sport management and differing sport-driven social science departments to consider the calls of the past and this paper and begin to reset the research agendas of our institutions to include the voices of all women, non-binary folk, and girls in sport. We make these calls in the face of seemingly assumed knowledge regarding the researching of women and girls within sport. We have used this paper to challenge this thinking: If the under researching of women and girls in sport is widely accepted why have these calls continuously gone unanswered? We are not calling for theoretical or methodological innovation or change. What is required is a collective discipline approach to correct these shortcomings in research agendas. If not, as we have demonstrated with this study, research agendas and approaches will continue to only provide a partial picture of the lived experiences of women and girls in sport.

Conclusion

Through this review, we have shown the current, and frankly unacceptable, state of play of sport development research for women and girls. Our analysis covered twenty years (of peer reviewed research journal publications and their content to show the stark disparity there is for wider consideration of the lived experiences of women and girls that intersect with race, sexuality, disability, class, gender and religion. Women and girls are not a homogenous group and as researchers in this field we encourage our colleagues to move beyond portraying generic samples of women and girls in sports research. We stand on the shoulders of those who have been working to address the lack of intersectional research in the sport management discipline and who have been advocating for change and calling for action for many years. We heed their call and hope this paper and our empirical data highlight their important, formative work that we need to build upon. As authors of this paper, we know we have a role to play in this as well. We will continue to do our best to drive change in our field and translate to industry to drive the change we need to see in practice to play sports more inclusive and reflective of everyone who participates, volunteers and works in sport and those who love to follow it. We hope the findings of this study serve as inspiration to redress and rectify past exclusions and give voice to more lived experiences in sports research.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

The first author conceptualized the original idea for the article, authors two and four performed the literature search and data analysis, and all four authors drafted and/or critically revised the work.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). The full data set of research articles used for the detailed review has been provided as an appendix.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (176.7 KB)Disclosure statement

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdel-Shehid, Gamal, and Nathan Kalman-Lamb. 2017. “Complicating Gender, Sport, and Social Inclusion: The Case for Intersectionality.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 159–162. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.887

- Ahmad, N., and H. Thorpe. 2020. “Muslim Sportswomen as Digital Space Invaders: Hashtag Politics and Everyday Visibilities.” Communication & Sport 8 (4–5): 668–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479519898447

- Ahmad, N., Holly Thorpe, Justin Richards, and Amy Marfell. 2020. “Building Cultural Diversity in Sport: A Critical Dialogue with Muslim Women and Sports Facilitators.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 12 (4): 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1827006

- Anderson, Denise. 2009. “Adolescent Girls’ Involvement in Disability Sport: Implications for Identity Development.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 33 (4): 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723509350608

- Armstrong, Ketra. 2011. “Lifting the Veils and Illuminating the Shadows’: Furthering the Explorations of Race and Ethnicity in Sport Management.” Journal of Sport Management 25 (2): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.2.95

- Behrensen, Maren. 2013. “In the Halfway House of Ill Repute: Gender Verification under a Different Name, Still No Contribution to Fair Play.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 7 (4): 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2013.856460

- Borland, John F., and Jennifer E. Bruening. 2010. “Navigating Barriers: A Qualitative Examination of the under-Representation of Black Females as Head Coaches in Collegiate Basketball.” Sport Management Review 13 (4): 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.05.002

- Burton, Laura J. 2015. “Underrepresentation of Women in Sport Leadership: A Review of Research.” Sport Management Review 18 (2): 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.02.004

- Butler, Deborah. 2013. “Not a Job for ‘Girly-Girls’: horseracing, Gender and Work Identities.” Sport in Society 16 (10): 1309–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.821250

- Camporesi, Silvia, and Paolo Maugeri. 2010. “Caster Semenya: Sport, Categories and the Creative Role of Ethics.” Journal of Medical Ethics 36 (6): 378–379. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.035634

- Caudwell, Jayne. 2007. “Queering the Field? The Complexities of Sexuality within a Lesbian-Identified Football Team in England.” Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 14 (2): 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701213750

- Clark, Becky, and Johanna Mesch. 2018. “A Global Perspective on Disparity of Gender and Disability for Deaf Female Athletes.” Sport in Society 21 (1): 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225808

- Coakley, Jay., Christopher J. Hallinan, and Brent McDonald. 2011. Sports in Society: Sociological Issues and Controversies. Sydney, AU: McGraw Hill.

- Cooky, Cheryl, and Shari L. Dworkin. 2013. “Policing the Boundaries of Sex: A Critical Examination of Gender Verification and the Caster Semenya Controversy.” Journal of Sex Research 50 (2): 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.725488

- Cottingham, Michael, Mary Hums, Michael Jeffress, Don Lee, and Hannah Richard. 2018. “Women of Power Soccer: Exploring Disability and Gender in the First Competitive Team Sport for Powerchair Users.” Sport in Society 21 (11): 1817–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1421174

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Cunningham, George B. 2014. “Interdependence, Mutuality, and Collective Action in Sport.” Journal of Sport Management 28 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0152

- Cunningham, George B., Pamela Wicker, and Nefertiti A. Walker. 2021. “Editorial: Gender and Racial Bias in Sport Organizations.” Frontiers in Sociology 6: 684066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.684066

- Denison, Erik, and Alistair Kitchen. 2022. “Out on the Fields: The First International Study on Homophobia in Sport.” Sport Australia, Accessed 26 April https://outonthefields.com.

- Evans, Adam B., and Gertrud U. Pfister. 2021. “Women in Sports Leadership: A Systematic Narrative Review.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 56 (3): 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220911842

- Fink, Janet S. 2016. “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Embedded Nature of Sexism in Sport.” Journal of Sport Management 30 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0278

- Frisby, W. 2005. “The good, the bad, and the ugly: Critical sport management research.” Journal of Sport Management 19 (1): 1–12.

- Harmon, Shawn H. E. 2020. “Gender Inclusivity in Sport? From Value, to Values, to Actions, to Equality for Canadian Athletes.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 12 (2): 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2019.1680415

- Holzer, L. 2020. “What Does It Mean to Be a Woman in Sports? An Analysis of the Jurisprudence of the Court of Arbitration for Sport.” Human Rights Law Review 20 (3): 387–411. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngaa020

- Hums, Mary A., Evan Frederick, Ann Pegoraro, Nina Siegfried, and Eli A. Wolff. 2020. “What’s in a Name? Examining Reactions to Major League Baseball’s Change from the Disabled List to the Injured List via Twitter.” Baseball Research Journal 49 (2): 22–32.

- Jolly, Shannon, Joseph N. Cooper, and Yannick Kluch. 2021. “Allyship as Activism: Advancing Social Change in Global Sport through Transformational Allyship.” European Journal for Sport and Society 18 (3): 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2021.1941615

- Knoppers, Annelies. 2015. “Assessing the Sociology of Sport: On Critical Sport Sociology and Sport Management.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 50 (4–5): 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214538862

- Knoppers, Annelies, and Mary McDonald. 2010. “Scholarship on Gender and Sport in Sex Roles and beyond.” Sex Roles 63 (5–6): 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9841-z

- Knoppers, Annelies, and Fiona McLachlan. 2018. “Reflecting on the Use of Feminist Theories in Sport Management Research.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Feminism and Sport, Leisure and Physical Education, edited by Louise Mansfield, Jayne Caudwell, Belinda Wheaton and Beccy Watson, 163–179. New York, NY: Springer.

- Knoppers, Annelies, Fiona McLachlan, Ramón Spaaij, and Froukje Smits. 2021. “Subtexts of Research on Diversity in Sport Organizations: Queering Intersectional Perspectives.” Journal of Sport Management 1: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0266

- Kraft, Erin, Diane M. Culver, Cari Din, and Isabelle Cayer. 2022. “Increasing Gender Equity in Sport Organizations: Assessing the Impacts of a Social Learning Initiative.” Sport in Society 25 (10): 2009–2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2021.1904900

- LaVoi, Nicole M. 2016. “A Framework to Understand Experiences of Women Coaches around the Globe: The Ecological-Intersectional Model.” In Women in Sports Coaching, 13–34. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lawley, Scott. 2018. “LGBT + Participation in Sports:‘Invisible’participants,‘Hidden’spaces of Inclusion.” In Hidden Inequalities in the Workplace, edited by V Caven and S Nachmias, 155–180. London: Palgrave.

- Laxdal, Aron. 2023. “The Sex Gap in Sports and Exercise Medicine Research: Who Does Research on Females?” Scientometrics 128 (3): 1987–1994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04641-5

- Marcelo de Castro, Haiachi, Cardoso Vinícius Denardin, Kumakura Roberta Santos, Mello Júlio Brugnara, Filho Alberto Reinaldo Reppold, and Gaya Adroaldo Cezar Araújo. 2018. “Different Views of (Dis)Ability: Sport and Its Impact on the Lives of Women Athletes with Disabilities.” Journal of Physical Education and Sport 18 (1): 55–61. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2018.01007

- Maxwell, Hazel, Megan Stronach, Daryl Adair, and Sonya Pearce. 2017. “Indigenous Australian Women and Sport: Findings and Recommendations from a Parliamentary Inquiry.” Sport in Society 20 (11): 1500–1529. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1284802

- McDonald, Mary. 2014. “Mapping Intersectionality and Whiteness: Troubling Gender and Sexuality in Sport Studies.” In Routledge Handbook of Sport, Gender and Sexuality, edited by Jennifer Hargreaves and Eric Anderson, 171–179. New York, NY: Routledge.

- McGarry, Jennifer E. 2020. “Enact, Discard, Transform: An Impact Agenda.” Journal of Sport Management 34 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0391

- Meier, H. E., M. Konjer, and B. Strauß. 2020. “Identification with the Women’s National Soccer in Germany: Do Gender Role Orientations Matter?” Soccer & Society 21 (3): 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2019.1629908

- Melton, E. Nicole, and Jeffrey D. MacCharles. 2021. “Examining Sport Marketing through a Rainbow Lens.” Sport Management Review 24 (3): 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1880742

- Mowatt, Rasul A., Bryana H. French, and Dominique A. Malebranche. 2013. “Black/Female/Body Hypervisibility and Invisibility: A Black Feminist Augmentation of Feminist Leisure Research.” Journal of Leisure Research 45 (5): 644–660. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i5-4367

- Perez, Caroline Criado. 2019. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. New York, NY: Random House.

- Pitts, Brenda G., and Deborah R. Shapiro. 2017. “People with Disabilities and Sport: An Exploration of Topic Inclusion in Sport Management.” The Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 21: 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2017.06.003

- Puwar, Nirmal. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies out of Place, Proquest Ebook Central Library (Purchased). Oxford: Berg.

- Ravel, Barbara, and Genevieve Rail. 2007. “On the Limits of “Gaie” Spaces: Discursive Constructions of Women’s Sport in Quebec.” Sociology of Sport Journal 24 (4): 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.24.4.402

- Ruddell, Jennifer L., and Kimberly J. Shinew. 2006. “The Socialization Process for Women with Physical Disabilities: The Impact of Agents and Agencies in the Introduction to an Elite Sport.” Journal of Leisure Research 38 (3): 421–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2006.11950086

- Schulenkorf, Nico, Emma Sherry, and Katie Rowe. 2016. “Sport for Development: An Integrated Literature Review.” Journal of Sport Management 30 (1): 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0263

- Scraton, Sheila. 2018. “Feminism(s) and PE: 25 Years of Shaping up to Womanhood.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (7): 638–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1448263

- Shaw, Sally, and George B. Cunningham. 2021. “The Rainbow Connection: A Scoping Review and Introduction of a Scholarly Exchange on LGBT + Experiences in Sport Management.” Sport Management Review 24 (3): 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1880746

- Shaw, Sally, and Wendy Frisby. 2006. “Can Gender Equity Be More Equitable?: Promoting an Alternative Frame for Sport Management Research, Education, and Practice.” Journal of Sport Management 20 (4): 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.4.483

- Simon, Mara, Jihyeon Lee, Megen Evans, Sheldon Sucre, and Laura Azzarito. 2021. “A Call for Social Justice Researchers: Intersectionality as a Framework for the Study of Human Movement and Education.” Kinesiology Review 1: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2021-0009

- Simpkins, Elena, Philippa Velija, and Lucy Piggott. 2022. “The Sport Intersectional Model of Power as a Tool for Understanding Intersectionality in Sport Governance and Leadership.” In Gender Equity in UK Sport Leadership and Governance, edited by Philippa Velija and Lucy Piggott, 37–50. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Singer, John N., Kwame J. A. Agyemang, Chen Chen, Nefertiti A. Walker, and E. Nicole Melton. 2022. “What is Blackness to Sport Management? Manifestations of anti-Blackness in the Field.” Journal of Sport Management 36 (3): 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0232

- Spaaij, Ramón, Annelies Knoppers, and Ruth Jeanes. 2020. “We Want More Diversity but…”: Resisting Diversity in Recreational Sports Clubs.” Sport Management Review 23 (3): 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.007

- Springer, Daniel L., Sarah Stokowski, and Wendi Zimmer. 2022. “The Coin Model of Privilege and Critical Allyship: Confronting Social Privilege through Sport Management Education.” Sport Management Education Journal 16 (1): 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2020-0093

- Storr, Ryan. 2021. “The Poor Cousin of Inclusion”: Australian Sporting Organisations and LGBT + Diversity and Inclusion.” Sport Management Review 24 (3): 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2020.05.001

- Symons, Kasey, Sam Duncan, and Emma Sherry. 2022. “Brief Research Report: “Nothing about us, without us.” A Case Study of the Outer Sanctum Podcast and Trends in Australian Independent Media to Drive Intersectional Representation.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4: 871237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.871237

- Teetzel, Sarah. 2014. “The Onus of Inclusivity: Sport Policies and the Enforcement of the Women’s Category in Sport.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 41 (1): 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2013.858394

- Teetzel, Sarah. 2020. “Allyship in Elite Women’s Sport.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 14 (4): 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2020.1775691

- Thorpe, Holly, Nida Ahmad, Amy Marfell, and Justin Richards. 2022. “Muslim Women’s Sporting Spatialities: Navigating Culture, Religion and Moving Bodies in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 29 (1): 52–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1855123

- Toffoletti, Kim, and Catherine Palmer. 2017. “Invisible (Women’s) Bodies.” In Routledge Handbook of Physical Cultural Studies, edited by Michael L. Silk, David L. Andrews and Holly Thorpe, 286–294. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Tredway, K. 2020. “Serena Williams and (the Perception of) Violence: Intersectionality, the Performance of Blackness, and Women’s Professional Tennis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (9): 1563–1580. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1648846

- Velija, P. 2012. “Nice Girls Don’t Play Cricket’: The Theory of Established and Outsider Relations and Perceptions of Sexuality and Class Amongst Female Cricketers.” Sport in Society 15 (1): 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2011.625274

- Whittemore, Robin, and Kathleen Knafl. 2005. “The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 52 (5): 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Wiesemann, Claudia. 2011. “Is There a Right Not to Know One’s Sex? The Ethics of ‘Gender Verification’ in Women’s Sports Competition.” Journal of Medical Ethics 37 (4): 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.039081

- Wilks, L. E. 2020. “The Serena Show: Mapping Tensions between Masculinized and Feminized Media Portrayals of Serena Williams and the Black Female Sporting Body.” Feminist Media Histories 6 (3): 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2020.6.3.52