Abstract

Whilst discourses of motherhood, such as the ‘ethic of care’ and intensive parenting are powerful and persuasive, no form of motherhood can be acceptable to all. In this visual autoethnography, researcher generated photographs, excerpts from training logs and personal narrative texts are used to explore some of the underlying discourses and assumptions associated with motherhood and sport from the perspective of a single parent. Employing a poststructural lens the author explores the ways in which she has knowingly negotiated her identity as a single mother and competitive-recreational long distant triathlete. The research places a spotlight on the significant support role that children can play in relation to adult involvement in sport, turning the tables on the existing focus on parent-athlete relationships. The findings provide further evidence of the value of sports clubs in supporting the continued participation of mothers, adding to the research on sport and parenthood and family studies.

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to explore some of the underlying discourses and assumptions associated with motherhood and sport from the perspective of a single parent engaged in long-distance triathlon. In so doing this research goes some way to address the concern initially raised by Kay (Citation2000) to broaden empirical research to reflect the growth of non-traditional family forms. In this visual autoethnographic study, researcher generated photographs, excerpts from training logs and personal narrative texts are drawn upon, extending our understandings of the cultural narratives in which sporting mothers are embedded.

The changes to a woman’s sense of identity that occur when one becomes a mother are well documented (Currie Citation2009; Spowart and McGannon Citation2023; Weaver and Ussher Citation1997). In particular, the first year of motherhood represents a “universal period of transition” (Currie Citation2009, 653), with some women experiencing a loss of ‘self’ due to the merging of identities (Hutchinson and Cassidy Citation2022). For full-time mothers who relinquish positions of status in the workplace to stay at home and care for their children, this loss of self is often greatly felt (Edhborg et al. Citation2005). Mothers have disclosed that they feel devalued when their motherhood roles are viewed as less demanding than paid work (Edhborg et al. Citation2005). In addition, women often feel obligated towards the family and place their families’ needs before themselves, frequently resulting in self-depreciation and a lowered self-esteem (Hutchinson and Cassidy Citation2022).

As gendered patterns of work, family and sport have shifted so too have ‘good mother’ discourses and practices. Evidence over the past two decades suggests that there are many ways of ‘performing’ motherhood and sport can provide a space for enhanced well-being and the expansion of feminine identity in addition to positive parental role-modelling (Spowart and McGannon Citation2023). Taking time out to surf was articulated as a specific strategy for the achievement of positive emotional and relational states by mothers in a New Zealand study (Spowart, Burrows, and Shaw Citation2010). These mothers argued that a “happy mum equals a happy family life”, and that engaging in a sport of their choosing, and having time out from parenting helped them to become better mothers and partners, though they did not always escape feelings of guilt for doing so.

The experiences of mothers participating in a range of sports, at all levels from the recreational to the elite, are receiving increasing attention in the social sciences (McGannon and McMahon Citation2022; McGannon, Graper, and McMahon Citation2022; Spowart and McGannon Citation2023; Spowart Citation2021), however, much of our understanding remains largely based upon mothers in couple (often heterosexual) relationships. The experiences of single mothers remain significantly under researched despite the classic nuclear family no longer being the norm. Research has also frequently highlighted the significant role partners play in facilitating mothers’ physical activity time (Saligheh, McNamara, and Rooney Citation2016; McGannon, Tatarnic, and McMahon Citation2019), with time constraints cited as one of the main barriers to participation in sport and fitness activities (Clark and Thorpe Citation2023; McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018; Walsh et al. Citation2018). So, how then do single mothers construct their lives as recreational athletes?

Single mothers are likely to face additional challenges in balancing their athletic pursuits with their parenting responsibilities. They may have less time and resources than other parents and, without partner support, may need to rely on social support networks to help them manage their schedules and responsibilities (Meier et al. Citation2016; Zehl, Thiel, and Nagel Citation2023). However, taking time out from childcare responsibilities can provide rejuvenation that in turn leads to parents spending greater quality time with their children (Spowart, Burrows, and Shaw Citation2010). In a study of mothers engaged in a ‘Back to netball’ programme by Walsh et al. (Citation2018), one of the single parents noted the value of engaging in the team sport to provide her with a sense of belonging, a renewed focus on fitness and an increased sense of confidence.

Combining sport and family time

The notion of ‘taking time out’ from the parental role, and mundane domestic chores, to engage in sport autonomously is a common theme in the sport and motherhood literature (Segrave Citation2000; Soule Citation2018). That said, researchers have also examined family-based leisure and sports activities where mother and child physical activity are combined (Clayton and Coates Citation2015; Leberman and Hurst Citation2023). Discourses of intensive mothering that position the mother as the primary caregiver, expected to place their child’s needs ahead of their own (Bianchi et al. Citation2012; Hays Citation1996), often extends to family leisure. Intensive motherhood emphasizes that mothers should be highly invested in every aspect of their children’s development, education, and well-being (Hays Citation1996). To be deemed a good mother in the era of intensive motherhood, both pregnant women and new mothers are also subject to increasing pressures to carefully manage the risks that they encounter (Jette Citation2006). Exercising ‘appropriately’ becomes a ‘technology of the self’ with moral, personal and social implications (Spowart and Burrows Citation2016).

Mothers often engage in shared activities such as swimming for and with children to maintain proximity (Evans and Allen Collinson Citation2023) and to fulfil societal expectations of ‘good motherhood’. Evans and Allen Collinson (Citation2023) employ a feminist phenomenological theoretical framework to explore mothers’ embodied experiences of leisure-swimming with their pre-school aged children. Their findings show how intensive mothering discourses ‘play out’ in the swimming pool environment. The maternal experiences of participants in their study illustrated the extent of the emotional work in the management and supervision of young children’s embodied behaviours during family swimming time.

Researchers have also examined the interlinking identities of parent and athlete in lifestyle sports such as climbing. Clayton and Coates (Citation2015) argue that parents who climb in a space where children are present means that parenting and climbing identities can become entwined. In their study of seven heterosexual, dual-parent families where both parents climbed, they illustrate how the competing discourses of intensive parenting and personal investment in sport can lead parents to sharing, (or perhaps pushing), their own leisure interests as legitimate activities for children. Sharing leisure/sport time with your child(ren) is frequently positioned positively in family discourse since children of active parents are more likely to engage in long-term participation in physical activity (Stefansen, Smette, and Strandbu Citation2018). The parents in Clayton and Coates’ study were caught between several competing discourses, including discourses of risk-taking (Spowart and Burrows Citation2016) commitment to their serious leisure activity (Stebbins Citation2009), an ethic of care and spending shared family-leisure time with their children (Evans and Allen Collinson Citation2023).

Regardless of whether mothers are taking time out to participate in sport at a distance from their children, or whether they train and compete in spaces where children are present, there is general agreement that motherhood marks a transition when physical activity participation typically decreases (Miller and Brown McGannon, McMahon, and Gonsalves Citation2018). Exceptions to this, until recently, tend to be elite performers, with some well-known examples, such as British runner Jo Pavey, international tennis star Serena Williams and US soccer star Kristine Lilly, to name but a few. That said, McGannon and McMahon (Citation2022) illustrated how competitive recreational runners used their training and competition to exercise agency and carve out unique athlete-mother identities. In this paper I tell my own story of single motherhood and my increasing involvement in competitive, non-elite, long distance triathlon.

Triathlon, as ‘serious leisure’

To help the reader ‘make sense’ of the story Stebbins’ concept of serious leisure provides a useful lens (Stebbins Citation2009). Commitment to a particular leisure pursuit, such that involvement impacts upon career pathways, is at the core of ‘serious leisure’, a term first coined by the Canadian sociologist Robert Stebbins in 1982. The term has subsequently been refined into the following definition:

The systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volunteer activity sufficiently substantial, interesting, and fulfilling for the participant to find a (leisure) career there in acquiring and expressing a combination of its special skills, knowledge, and experience. (Stebbins Citation2009, 764)

Due to the volume and nature of training required long distance triathlon is not a sport typically associated with mothers of young children. In fact, the numbers of women competing in long distance events is far lower than men. As an example, in 2022, Ironman Wales a popular long-distance triathlon event attracting over 2200 competitors, included only 11.6% females, with most of these being in the older age categories (over 45 years), and therefore less likely to have childcare responsibilities of young children.

Methodology

This research adopts a poststructural lens, with Foucauldian concepts of discourse and subjectivity as central. Scott (Citation1990, 135–136) defines discourse as a “historically, socially, and institutionally specific structure of statements, terms, categories, and beliefs that are embedded in institutions, social relationships, and texts". Discourses of motherhood thus manifest themselves as values and beliefs that people hold as ‘truths’ about motherhood and provide the “conditions of possibility” for thought in any cultural and historical context (Foucault Citation1975, 203).

Subjectivity may be defined as “the varying forms of selfhoods by which people experience and define themselves” (Lupton and Barclay Citation1997, 8). From a post-structural perspective, subjects are not seen as rational, unified, essential beings who exist outside the influence of culture, but rather subjects are “dynamic and multiple, always positioned in relation to particular discourses and practices and produced by these”. (Henriques et al. Citation1984, 3.) Viewed through this lens, the self is never static or complete, but constantly shifting, the effect of and contingent upon, power and knowledge relations.

Visual autoethnography

Autoethnography is a research approach that seeks to understand cultural phenomena through personal experiences and reflections. To move beyond autobiographical accounts, autoethnography involves employing a critical ethnographic lens to illustrate the broader cultural significance of the personal (Sparkes Citation2020). Although the blurring of the researcher-participant relationship has attracted some criticism, the ‘insider’ perspective provides access to “in-depth and often highly nuanced meanings, knowledge about, and lived experience of the field of study” (Allen-Collinson Citation2012, 205). In explaining critical autoethnography, Holman (Citation2016) likens story to theory, and draws on the work of Judith Butler to claim that “the intersection of theory and everyday language is crucial to telling and re-imagining not only what we can say, but also who we can be” (229, italics in original).

Approaches to autoethnographic research are increasingly diverse and have grown in popularity in sports research over the past twenty years (Sparkes Citation2020). In the motherhood and sport literature a variety of autoethnographic accounts have lately been adopted. For example, McMahon et al. (Citation2020) use an analytical approach to their collaborative autoethnography to explore the experiences of mothers of children with autism. Adopting an evocative style to their collaborative autoethnography, Spowart and Pearson (Citation2023) tell their combined coach-mother and Paratriathlete-mother self-stories of preparing for, and participating in, the Norseman long distance triathlon in Norway. In recounting their story, they share the lived experiences of two middle-aged mothers, one of whom is diagnosed with cerebral palsy, and explore discourses of risk-taking in mothers.

Whilst less common, in recent years, researchers have started to incorporate visual data, such as photographs, videos, and drawings, into autoethnographic studies. One advantage of combining visual data and autoethnography is that it can provide a more holistic and immersive understanding of the cultural phenomenon being studied providing an alternative way of ‘knowing’ (Phoenix Citation2010). Hockey and Allen-Collinson (2006) weave together photographs and autoethnographic data to offer the reader specific cultural knowledge concerning how distance runners experience, understand and ‘know’ their typical running routes. By including photography in their methods, they provide insight into runner’s embodied feelings and experience of momentum and highlight the potential injury risks along the route. Visual data then can capture nuances and details that might be missed in written or spoken accounts. Additionally, visual data can make research findings, often incorporating complex layers, more engaging and accessible to a wider audience (Phoenix Citation2010). Phoenix (Citation2010, 94) contends that visual data, in its multitude of different forms, can prompt valuable questions such as: “How are we able to see? How are we allowed to see it? How are we made to see? What is being seen, and how is it socially shaped?”

With increasing use of social media sites, such as Facebook and Instagram, visual imagery has become central to the cultural construction of social life in contemporary Western societies (Phoenix and Rich Citation2017). To structure the expanding and increasingly diversified field of research employing visual methods, Prosser and Loxely (2008) distinguish between “researcher-created” and “respondent generated” visual data collection methods.

While there are several benefits to combining visual data and autoethnography, there are also some drawbacks to consider. A key concern is privacy and consent, particularly where visual data might identify people. Furthermore, using visual data in autoethnography can also raise questions about the researcher’s role and positionality. Visual imagery is constructed and as such is not objective or value-free (Phoenix and Rich Citation2017; Rose Citation2007) but shaped by social, cultural, and political factors that influence how they are produced, circulated, and interpreted. They carry meaning and symbolism that can reflect or reinforce certain power relations, values, and ideologies.

The data I draw on here comprises three self-produced photographic images, and eight photographic images taken by others (three taken by my children). All images were selected and curated on Facebook by me. I analyse the photographs by referring to my personal training log that chronicled my life journey as a single parent and competitive triathlete over the period when my children were aged 6 to 13 years (2010–2017). The combined data act as reflexive prompts for my own autoethnographic interpretation of the images, however the images may also be read by others in alternative ways. Two central questions drove this research:

How are discourses of motherhood and ‘serious leisure’ articulated through the images?

How was competitive long-distance triathlon maintained as a single mother?

Ethics

Ethical approval was gained from the author’s institution prior to the writing of the paper but not prior to the taking of the photographs, some of which date several years. Whilst this autoethnographic story is told from my perspective, the story is not wholly my own, and impacts relational others (Lapadat Citation2017), particularly my children. As Lapadat (Citation2017, 593) cautions: “It is not always possible to anticipate the consequences the text might have for others’ lives in the future, or for one’s own”.

My children, featured here, are now both adults and both provided written consent for the photographs to be used. That said, in developing this paper I am conscious of the position of power I hold, not only as researcher but as a mother. I consulted widely as to how to best protect the children, including involving them in editing draft versions of the stories told and using pseudonyms. Anonymity is not possible, and I am therefore careful to tell only what I believe is responsible to share. This responsibility extended to excluding photographs where other individuals are recognisable and only including photographs already shared publicly on Facebook via my own and our sports club members’ pages. My children also deselected certain photographs (9) without giving any explanation, as they were encouraged to do. I wanted to include images they were comfortable with, and these, I speculate, are likely associated with the positive memories those images hold for them, hence the ‘holiday shots’ included.

Inevitably, there is a balance between conducting ethical research and including personal photographs. As with other forms of qualitative research what participants remember or choose to share for the purpose of public consumption varies. By carefully staging and selecting the images as a means of performing my mother-athlete identity on Facebook, I presented a curated version of my ‘self’ that is not necessarily a true reflection of my ‘self’, but rather what I would like to it be. The discussion that follows is therefore not only an analysis of the narrative revealed by each photograph but also provides an opportunity for the reader to draw their own conclusions about the identity I wanted to present.

Setting the scene

To better situate the analysis that follows brief biographical information is provided. I have a history of competing in endurance sports that dates back over three decades, and importantly for this research, before I became a mother. Originally a competitive rower, I switched to the sport of triathlon in 2006, when my children, Natalie and Tom (pseudonyms), were four and five years old respectively. I was married at that time and living in New Zealand, although we were all British citizens. In 2009 I won a bronze medal in the sprint category as an ‘age-group’ competitor at the World Triathlon Championships in Perth. My marriage was already difficult, and triathlon increasingly became my ‘escape’. I began to engage in longer, endurance triathlons over the ‘ironman’ distances of 3.8 km swim, 180 km bike and 42 km run, completing my first full distance event as 5th woman in 2013. Between 2010 and 2017, the period pertaining to this research, I completed over 40 triathlon events.

During this time, I developed a regular habit of sharing my training and competitions online via Facebook in a ‘performative act’ designed in part to engage my fellow triathlete community in my sporting endeavours, and in part, as a self-motivational tool. The discussion that follows is an analysis of the narrative revealed by each photograph and an exploration of the story that I wanted to tell by presenting these images on Facebook. This reflexivity opens a space in which we can use the analysis to consider the implications for the mother identity and mother-athlete identity more broadly.

A story of triathlon and motherhood

The beginnings: developing a sense of pride

In 2010, I completed my first middle distance triathlon (1.9 km swim, 90 km bike and 21 km run), Challenge Wanaka, New Zealand, which only the previous year, had seemed a goal well beyond my reach. My children, then 6 and 7 years old, travelled to the event with me and their father. Completion took just over six hours, and whilst I raced, Tom and Natalie played in a nearby park, pic-nicked and road their bikes, supervised by their father. The picture shows the joy and sense of pride on the children’s faces as we were applauded by a large crowd lining the final half a mile to the finish line. I don’t look towards their father (the photographer) to smile, as the kids do, but continue my gaze ahead to the finish line. The pain of the event, clearly showing on my face, arguably easier to deal with than the emotional stress of our failing relationship. The photo might otherwise be read as depicting ‘togetherness’ between mother and children with the children here playing a supporting role in my personal achievement, rather than the other way around. They relished the noise of the crowd and the attention they received at the finish line ().

Soon after this photo was taken, my relationship with Tom and Natalie’s father deteriorated and we returned to the UK (separately) where our wider families resided. The children stayed with their father for one night a week and very infrequently for a weekend.

A shared identity as triathletes

As the wheels were put in motion towards divorce, I set a new triathlon goal to complete an Ironman, double the distance of my previous triathlon achievements. I was juggling working full-time, with both children in primary school, and my estranged husband worked shift work. Most childcare responsibilities fell to me, yet I still felt compelled to accomplish an ironman. Le Breton (Citation2000) argues that the formation of certain risk sports communities is a signifier of anxiety and loneliness amongst the middle classes. I am not sure I was conscious of being lonely, but I certainly strived to keep busy and show the world via Facebook that I was living my ‘best life’ as a mother and an athlete. My mindset was very focused on ‘being happy as a single mum’ and how I presented this to others mattered to me. I wanted my ‘Facebook world’ to see me thriving as a single mother. A two-fingered salute to my estranged husband and to more conventional constructions of Western family life.

I drew on neoliberal discourses of individualism and personal choice to craft my ‘self’ as a mother-triathlete. Such discourses work to persuade us that we oversee our own destinies and can shape the conditions of our lives (Baker Citation2010). I sought out a triathlon community of endurance athletes and prioritised training over ironing and other mundane domestic chores. In fact, I spread the word to as many other women as I could about the time saved by abandoning my iron! I ‘trained’ the children to prepare their own food and training kit so that they were ready to fly out of the door as soon as I arrived home from work. I justified this as ‘good parenting’ preparing the children to fend for themselves. Together with Natalie and Tom, we joined a local triathlon club and a cycling club. Both clubs had junior sections facilitating the transition of my children into the sport and enabling my continued training alongside both my children and more experienced others.

The clubs’ culture and kit my children and I shared promoted a sense of belonging at a time when family belonging was under threat. I mixed up my training schedule to include rides with Natalie and Tom and soon both children were entering junior events and races. The picture below shows Natalie and I at the end of a gruelling and hilly 35-mile ride endurance event across Dartmoor National Park. Natalie was 11 years old and the youngest competitor by several years. Our closeness in the picture conveying our mother-child bond could easily be read as intensive parenting. What the picture does not reveal is that the required age for entry into the event was 13 years. I had lied on the entry form to secure Natalie’s place. I justified this due to Natalie’s cycling competence and by riding in front, and giving Natalie my wheel, greatly reducing the effort required – but nevertheless, with several thousand feet of ascent, it was a difficult challenge for an 11-year-old. The difficulty of the challenge meant that I was on ‘high alert’ throughout the event. Careful at every point along the way to protect her from other riders, traffic and oncoming road obstacles. Putting myself in front, maintaining proximity (a few centimetres apart), calling out to other riders, and coaching Natalie for the nearly three hours that it took us to complete the event ().

I look back at this photo now and see her tiny child frame against mine. Whatever your thoughts on that, we both felt pride and a sense of accomplishment that day. We celebrated with chocolate and cake afterwards! Rose (Citation2000, 556) maintains that photographs should be considered as “cultural documents offering evidence of historically, culturally and socially specific ways of seeing the world.” The picture of (single) mother and daughter dressed in club cycling kit, not an image even imaginable a few decades earlier, portrayed a sense of achievement, togetherness and family time.

Combining home-life, child-care and training

To achieve my goal of completing an ironman I employed a coach to oversee my training. Each discipline of swim, run and bike, had 3 training sessions scheduled per week. In addition, 2 strength and conditioning sessions needed to be scheduled plus a weekly routine massage. In the build-up to my first ironman an easy week included 15 h training and increased to over 20 h a few months out from the event. This schedule was meticulously planned and squeezed into narrow gaps in the days alongside the requirements of a full-time job and parental responsibilities. To accommodate the rigorous schedule, I employed a range of strategies. Often, I would complete training sessions between 5–7am before the children got up for school; on several evenings a week I would train alongside my children’s junior club activities; and at the weekends when I had responsibility for the children I would plan ‘brick-sessions’ (running straight after a cycle) using the indoor turbo trainer and treadmill, or I would sneak out early whilst they were still in bed and later complete my training at home.

A comprehensive training diary was kept online and shared via google drive to facilitate coach-monitoring. My diet, weight and stress score were monitored daily. The triathlon community we became part of provided social comfort, stability, and a sense of normality, providing what Atkinson (Citation2008, 170) describes as a “special community of like-minded actors”. As my relationship with my husband continued to further fracture, I became more entrenched in the triathlon club which provided the perfect ‘escape’. I took on a role as club coach and fellow club members provided practical support in numerous ways, including providing support with household maintenance due to the many skilled professionals who were members (electrical, plumbing and plastering). Club members became our ‘new family’ as we established ourselves back in the United Kingdom.

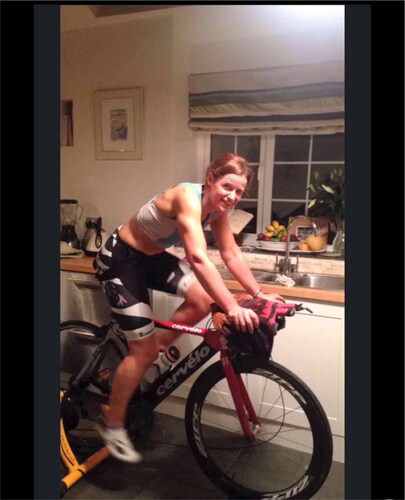

I posted the following picture, taken by my daughter, on Facebook in 2013. The caption read: “No pain, No gain, No roast dinner  ”. A 4-h training set on the turbo trainer, completed as two × two-hour sets with a 15-minute break in between, allowed me to remain in the house with the children and simultaneously cook roast dinner. I shared this achievement in my training log with my coach as follows: “You’ll be proud of me today, four hours of turbo at set power output and I still managed the perfect roast dinner. [Natalie] shouting at me helped!” ().

”. A 4-h training set on the turbo trainer, completed as two × two-hour sets with a 15-minute break in between, allowed me to remain in the house with the children and simultaneously cook roast dinner. I shared this achievement in my training log with my coach as follows: “You’ll be proud of me today, four hours of turbo at set power output and I still managed the perfect roast dinner. [Natalie] shouting at me helped!” ().

Figure 3. Lucy completing a 4 hour turbo set in the kitchen whilst cooking roast dinner.

Source: Authors.

The background provides further evidence of carefully moderated diet, my daily fruit smoothies, with a large bowl of fruit on the windowsill and a blender on the countertop. With my husband gone accessing the gym or going out for long training rides became problematic. To overcome this, I reinvented the house ‘rules’ – an opportunity to reaffirm myself as the head of the household. Our bikes, formerly banished to the garage, came into the house in an act of defiance, but also demonstrating the seriousness of my pursuit. Natalie and Tom seemed to like this approach and in the next photograph I captured Tom practicing his cycling on some rollers in the hallway. I again proudly posted this on Facebook since balancing on rollers is a skill many adult cyclists find difficult to master and many of my Facebook friends, cyclists, could not do this. Perhaps not a well-known life-skill, but illustrating that I was encouraging a healthy, active lifestyle for my children, and certainly evidence that triathlon had become all-consuming in our household ().

Togetherness via a triathlon lifestyle

Whilst I crafted a triathlete identity, the good mother discourse persisted in my life; I did not want to compromise spending time with my children. That shared time however was largely channelled around our sporting pursuits and in so doing I both resisted and reinforced gender stereotypes. Natalie and Tom both wanted to race triathlon like me. They felt pride in wearing the same club kit. In the following photo, taken by Tom, you see me in arguably a more traditional supporting motherhood role, assisting Natalie moments before the start of a race. Mothers often play facilitating roles in children’s sporting endeavours (Davis et al. Citation2021), here demonstrating the ethic of care. However, what is not evident from this photo is that I too was racing that day. I had arranged for another member of the club to watch over my children whilst I did so ().

Figure 5. Lucy helping Natalie to put on her obligatory swimming cap before the start of a junior triathlon.

Source: Authors.

This ‘togetherness’ extended to family holidays with our close-knit family unit taking our bikes, swimming costumes, and running shoes on every holiday. and are photographs taken by me during a family holiday to France in 2015. shows Natalie and Tom with their backpacks on boarding the cross-channel ferry from Plymouth to Roscoff. My bike, in the background of the second photograph, rested against a wall whilst I captured the moment. The return ticket cost £35 each, suiting my carefully managed budget that had been significantly reduced since the divorce. We stayed for a week at budget Airbnb accommodation roughly 10 miles from the ferry port. The locality meant that we could carry everything we needed for a week (mainly sports equipment!) in our backpacks. The children were told ‘if you can’t carry it, you can’t take it!’

The photos illustrate the free time spent together as social outings. The sight of Natalie and Tom in their cycle outfits with large backpacks attracted the attention of other adults onboard the ferry, and both children proudly received the attention and positive comments, reinforcing their ever-growing confidence as junior cyclists. Whilst it was typical to see adults travelling to France in this way, it was novelty to see children transporting themselves. Previous research has illustrated that family leisure is often regarded as a “duty of parenthood” (Shaw and Dawson Citation2001, 227) and that participation in family leisure activities can enhance family bonding.

Training was integrated into our daily holiday schedule by way of a cycle ride (typically around 30kms) each day, a swim in the sea or holiday complex pool, aligning closely to Stebbins (Citation2009) concept of serious leisure. I would squeeze in my obligatory runs by either fitting them in before breakfast or taking an off-road cycle route that enabled Tom and Natalie to accompany me on their bikes. Due to the lack of support from other adults on holiday, ‘togetherness’ was further reinforced. This notion of family ‘togetherness’ was also identified using photo elicitation by Leberman and Hurst (Citation2023) in their research exploring participants’ experiences of motherhood and martial arts.

Mutual support and shared responsibility

Good teams share responsibility. Whilst parental support is commonly associated with good mother discourses the support children provide to their parents is not typically highlighted and yet children of single parents in particular can (and frequently do) provide support to parents in a myriad of ways (McLanahan and Sandefur Citation1997). In the motherhood and sport literature this notion of mutual support is notably absent with the focus typically being on parent-athlete relationships and the facilitation of children’s sports participation (Davis et al. Citation2021). Leberman and Hurst (Citation2023) recently revealed how children’s involvement in martial arts can work as a motivator towards participation, demonstrating how involvement in sport might be mutually beneficial for parents. Whilst several authors have highlighted shared family time (e.g. Evans & Allen-Collinson, Clayton and Coates Citation2015) the parents (often the mother) have been shown to be the care-givers.

In the next photograph Natalie and I pose for a ‘selfie’ whilst in the French Alps during another active summer holiday in 2016. We were in fact several hours from our accommodation and I was completing a scheduled long run of around 25kms. In the photograph I am displaying my triathlon identity via my ironman Wales finisher shirt (2014) – a badge of honour akin to a military medal amongst the triathlon subculture. Completing an ironman was no longer the goal however, for now the goal had shifted to the ambition to secure an age-group podium finish and qualify for the British long distance triathlon age-group team.

It was over 30 degrees, and the route was mountainous. I was fifth at Ironman Wales and I was now aiming for the top three in my next age-group race. My training had necessarily ‘ramped up’ to another level and the children became invested in my goal too ().

Figure 8. Natalie provides Lucy with nutritional support on a lung training run in the French Alps, 2015.

Source: Authors.

Natalie and I had been transported by ski lift to the mid-way point of a mountain bike resort enabling us to reach a relatively wide and safe mountain track so that Natalie could ride alongside me (or at least, that is what the lift operator had told us). In her backpack Natalie carried water, food, and spare clothing for us both. She adopted the role as coach, providing feedback on mileage covered and offering regular encouragement.

With the absence of other adults on holiday, the children frequently adopted support roles, sharing various responsibilities. , another ‘selfie’ taken by Natalie, shows the three of us smiling towards the camera, dressed in wetsuits, with Tom holding a surfboard. One might easily assume from this picture that we are all about to enjoy a family surfing experience together, with me adopting the caring role. In reality, I am about to go sea swimming as part of my open water training. Open water swimming should never be undertaken alone due to the inherent risks associated with the sport (Tipton and Bradford Citation2014). The buoyant surfboards provide me with essential safety cover, and so whilst I look up to check on my children’s whereabouts whilst swimming, they too are monitoring my movements. Aware that should I get into difficulty, such as through the onset of cramp, they can provide lifesaving support. Both children had spent several years as members of the New Zealand Surf Life Saving Society ‘nipper’ programme providing them with surf awareness and surf rescue skills. Here, aged 12 and 13 years they were competent and confident to assume this role, overseen from the beach by the Professional Lifeguard team whom I had notified before entering the water.

Thus far the pictures have highlighted the integration of my triathlon experiences into our daily family lives where activities were carefully adapted to be inclusive of the children. However, this teamwork extended to supporting me on race day too when there would be an extended period of separation. In 2017, the three of us returned to New Zealand and to Challenge Wanaka, where I had completed my first middle distance triathlon seven years previously. This time I had entered the full distance event. Published results from the previous years suggested that if I could complete the event in around 12 hrs 45 min I would likely secure a podium finish. My training had been going well and this was a realistic goal.

For the duration of the event Tom and Natalie, now 13 and 14 years old, would have to take care of themselves. Whilst many teenagers would be left to amuse themselves at this age, we were no longer in our home country and if I were to have an accident during the race the nearest hospital was several hours away. I had a friend on ‘standby’, just in case, and had left my children with my mobile phone so that they could contact a nearby cousin in that event. Motherhood guilt consumed me in the lead up to the event. I put every contingency plan in place that I could think of and hoped for the best. They were sensible children and had other adults to call on in the worst-case scenario I convinced myself. shows that these negative thoughts had left me as I headed out on the bike leg of the beautiful course that skirted the shores of Lake Wanaka. The large grin etched on my face revealing the thrill and enjoyment of riding my carbon, aero, race bike at speed. Across the three disciplines, cycling is my strength, and I was high in confidence as I set out on the 180 km ride, determined to enjoy the scenery along the way.

Whilst not a fast long distance triathlon course, the bike leg is not particularly technical, with no real tricky descents or traffic to negotiate. It had been strategically selected to minimise the risk of accident. Alone on my bike my motherhood responsibilities wandered in and out of my thoughts. ‘Where are they now?’ ‘Will I see them enroute?’ I was so used to them being alongside me separation provided a mental challenge.

I entered the second transition ahead of my predicted time and set out on the run route. I quickly scoured the crowds leading out of town expecting to see Natalie and Tom. I was disappointed not to see them, but I was simultaneously aware that a Dutch athlete was fast approaching to overtake. I told myself to run my own race and let her pass. As she did so, Tom appeared ‘You’re now in 3rd place mum, you can’t let anyone else past’ he coached. Using my iPhone, the children had downloaded the live tracking app for the race. They had carefully selected all the female athletes in my age-group allowing them to monitor the relative positions of my rivals. They then took it in turn to run to certain points on the course providing me with the latest updates. Ironman racing can be a lonely experience and typically athletes do not know until the finish where they are in relation to fellow age-group competitors ().

Figure 11. Lucy crossing the finish line at Challenge Wanaka with her children, securing a bronze medal in the 40-50 year age category and a place in the European Championships.

Source: Authors.

The race tactics conceived by Natalie and Tom allowed me to pace my run and conserve my energies as I knew where my nearest rival was for most of the race. Information which arguably helped to secure my final overall third position. In the final kilometre both children joined me, running alongside and shouting encouragement. We crossed the line together (), raising our arms in a collective sense of achievement and pride, illustrating the fluidity of motherhood and feminity discourses.

Conclusion and wider implications

The lifestyle sports literature has previously demonstrated the extent of the entanglement between sport and family lives by committed participants (Clayton and Coates Citation2015; Spowart Citation2021; Spowart, Burrows, and Shaw Citation2010). Through visual representation and personal narrative this paper highlights the complex web of discourses that circulate in society and adds further evidence of the importance of sport in the lives of some mothers. Here, discourses of ‘good motherhood’, ‘togetherness’ and ‘family-leisure’ sit alongside discourses of ‘healthy lifestyles’, neoliberal discourses of ‘personal autonomy’, and serious leisure discourses of ‘extreme commitment’ and complete entanglement in day-to-day life. It is possible to be a supportive single-mother who is connected to her children, whilst also carving out an identity as a competitive-recreational triathlete.

Foucault’s ideas regarding ‘technologies of self’ afford a useful heuristic for exploring the story of single motherhood and competitive triathlon recounted here. For Foucault, it is not the participation in the activity that is significant; rather the crucial factor in understanding technologies of self is critical thought (Foucault, Citation1985). He believed that “[t]here are times in life when the question of knowing if one can think differently than one thinks, and perceive differently than one sees is absolutely necessary if one is to go on looking and reflecting at all” (Foucault, Citation1985, 8). Whilst discourses of motherhood, such as the ‘ethic of care’ and intensive parenting are powerful and persuasive, no form of motherhood can be acceptable to all and as new family types have arisen in the form of same-sex couples, divorced families, reconstituted families, and transgender families, it is time to move beyond research focused on traditional nuclear families.

For Foucault, it is the constant critique of dominant discourses that brings about the possibilities of transformation. In this visual autoethnographic account, it is the attitude with which I constructed my triathlon-single mother identity, knowingly negotiating “the omnipresent menace of discourses of ‘good parenting’” (Clayton and Coates Citation2015, 239), that makes a difference in relation to its transformative potential.

Despite the growth of women engaging in a multitude of sports, long distance triathlon remains an activity dominated by males and is not a sport typically engaged in by mothers of young children. To change one’s condition, individuals must learn to problematize their identities by becoming self-reflexive. As the individualised engagement by mothers in serious leisure activities become part of the social fabric, this may establish an opportunity for broader societal impact by broadening present discourses of femininity and motherhood. Butler’s understanding of the relationship between gender and identity is useful here (1999). Butler advocates for the “reconceptualization of identity as an effect, that is, as produced or generated” (Butler, 1999, 187). Viewing identity in this way “opens up possibilities of agency that are insidiously foreclosed by positions that take identity categories as foundational and fixed” (Butler, 1999, 187). Butler urges feminists to consider how this performance can be used as a tool for social change. Viewing identity in this way, should permit a greater range of possibilities for doing gender (Butler, 1999). In other words, we can ‘buy into’ and adopt certain practices of motherhood, thus contributing to and reinforcing their institutionalisation, or we can draw from a range of alternative discourses, thereby creating or affirming our own way of ‘being’. Personal stories of motherhood, such as this, hold significant value within sports research as they offer a nuanced and contextualised understanding of the complex interplay between individuals, their experiences, and the broader sporting landscape whilst also adding to the range of alternative discourses circulating about motherhood.

That the space is formed and sustained more by my own self-interest in triathlon, than the children’s desire to take part, is a moral dilemma that is countered and legitimized through the sharing of family leisure time and the maintenance and encouragement of healthy lifestyles. The sharing of this time was given even greater significance due to my full-time employment status. Much like the surfers in Spowart, Burrows and Shaw’s (2010) study and the climbers in Clayton and Coates (Citation2015) study, I rationalised (and continue to rationalise) our family’s collective involvement in triathlon by comparing to the ‘unhealthy’ alternatives of sedentary lifestyles and computer games. Of course, I am cognisant of the fact that what is considered healthy is, in itself, a social construction, and others may read the relentless pursuit of sporting achievements as ‘unhealthy’. In addition, I justified my involvement in triathlon by celebrating the sporting achievements of my children and sharing these successes on Facebook. Similarly, my triathlon successes are often photographed with my children, reinforcing shared family time.

For readers interest, my children did engage in several sports outside of triathlon. Tom became a very good mountain biker and joined a local club where he trained, competed, and later coached other youngsters. Natalie took up Netball between the ages of 11 and 14, playing for the school and a regional satellite team until a serious injury at a trampoline park meant that she could no longer run. Now, as adults, neither are involved in triathlon, although Tom used his swimming knowledge to secure a paid position as a Lifeguard over the summer holidays.

A key and novel finding of this research is the significant support role that children can play when their involvement is integrated into adult sporting pursuits. Typically, previous research has focused on the support role played by parents in relation to their children’s sporting pursuits (Davis et al. Citation2021), and parental sports engagement is positioned as something that is undertaken autonomously (Leberman and Hurst; Soule Citation2018). In this autoethnographic account Natalie and Tom offer: motivation; coaching; carry essential supplies during training; act as essential safety cover; and provide vital information on race day. Rather than regarding this as selfish on my part, instead I choose to draw on neoliberal discourses of autonomy and individual responsibility, teaching my children skills that they will require in later life. As a level 3 triathlon coach, risk assessments were undertaken in all situations, with the children’s safety always placed as paramount.

Engagement in the local triathlon club provided a ‘safe moral space’ for both me and the children particularly as divorce and separation are common in triathletes (Atkinson Citation2008). It also provided a wider support network that I called upon at times whilst I was racing. Writing this paper has afforded me a further opportunity to reflect and ‘make sense’ of a difficult period of my life and highlighted how personal autonomy and well-being can comfortably sit alongside the motherhood role. Perhaps I was ‘judged’ by others for my decisions, but the triathlon club allowed for the construction of a meaningful identity as mother-triathlete that satisfied both the personal and the cultural conditions at play by reconstituting time and space so that both family and my ‘self’ benefitted, and the child-centred parenting ideology remained intact.

Like all research, this visual autoethnography presents a partial story, derived from reflections on my experiences aided by my personal training log, discussions with my children, and drawing on the selection of Facebook photographs While combining visual data and autoethnography can offer several benefits, such as providing a more immersive understanding of cultural phenomena and increasing the accessibility of research findings, it is important for researchers to be aware of the potential drawbacks, such as subjective interpretation, ethical concerns, and issues related to positionality. By being mindful of these issues, researchers can use visual data in a responsible and meaningful way, leading to more nuanced and impactful autoethnographic research. Future research could usefully offer more detailed understandings of how parents from diverse families maintain engagement in competitive and competitive-recreational sport. Greater attention could also be paid to the role of children in supporting parental engagement in sport to shift the focus from parent-athlete to child-athlete. Finally, further research employing a range of visual methods such as photo-elicitation using participant-generated photographs to explore the family dynamics and power relations associated with sports participation would add to our understanding.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the support of my children in preparing this paper and throughout my triathlon journey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allen-Collinson, J. 2012. “Autoethnography: Situating Personal Sporting Narratives in Socio-Cultural Contexts.” Qualitative Research on Sport and Physical Culture, edited by K. Young and M. Atkinson, 191–212. Bingley, UK: Emerald.

- Ankers, E. 2023. “Experiences and Perceptions of Motherhood and Climbing.” Annals of Leisure Research : 1–17. doi:10.1080/11745398.2023.2177178

- Atkinson, M. 2008. “Triathlon, Suffering and Exciting Significance.” Leisure Studies 27 (2): 165–180. doi:10.1080/02614360801902216

- Baker, J. 2010. “Great Expectations and Post-Feminist Accountability: Young Women Living up to the ‘Successful Girls’ Discourse.” Gender and Education 22 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09540250802612696

- Bianchi, S. M., L. Sayer, M. A. Milkie, and J. P. Robinson. 2012. “Housework: Who Did, Does or Will Do It, and How Much Does It Matter?” Social Forces; a Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation 91 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1093/sf/sos120

- Clark, M., and H. Thorpe. 2023. “Digital Self-Tracking and Spacetimemattering: Beyond Linear Understandings of Mothers’ Sporting Bodies.” In Motherhood and Sport: Collective Stories of Identity and Difference, edited by Lucy Spowart, and Kerry R. McGannon, 105–118. London: Routledge.

- Clayton, B., and E. Coates. 2015. “Negotiating the Climb: A Fictional Representation of Climbing, Gendered Parenting and the Morality of Time.” Annals of Leisure Research 18 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1080/11745398.2014.957221

- Currie, J. 2009. “Managing Motherhood: Strategies Used by New Mothers to Maintain Perceptions of Wellness.” Health Care for Women International 30 (7): 655–670. doi:10.1080/07399330902928873

- Davis, Louise, Daniel J. Brown, Rachel Arnold, and Henrik Gustafsson. 2021. “Thriving through Relationships in Sport: The Role of the Parent–Athlete and Coach–Athlete Attachment Relationship.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 694599. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694599

- Edhborg, M., M. Friberg, W. Lundh, and A. Widstrom. 2005. “Struggling with Life: Narratives from Women with Signs of Postpartum Depression.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 33 (4): 261–267. doi:10.1080/14034940510005725

- Evans, A. B., and J. Allen Collinson. 2023. “Phenomenological Insights on Motherhood and Aquatic Embodiment.” In Motherhood and Sport: Collective Stories of Identity and Difference, edited by Lucy Spowart, and Kerry R. McGannon, 15–29. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1975. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1985. The Use of Pleasure. The History of Sexuality Volume Two. London: Penguin.

- Hays, S. 1996. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale.

- Henriques, J., W. Hollway, C. Urwin, C. Venn, and V. Walkerdine. 1984. Changing the Subject: Psychology, Social Regulation and Subjectivity, London: Methuen.

- Hockey, J., and J. Allen Collinson. 2006. “Seeing the Way: Visual Sociology and the Distance Runner’s Perspective.” Visual Studies 21 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1080/14725860600613253

- Holman, J. S. 2016. “Living Bodies of Thought: The ‘Critical’ in Critical Autoethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 22 (4): 228–237. doi:10.1177/1077800415622509

- Hutchinson, J., and T. Cassidy. 2022. “Well-Being, Self-Esteem and Body Satisfaction in New Mothers.” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 40 (5): 532–546. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1916452

- Kay, T. 2000. “Leisure, Gender and Family: The Influence of Social Policy.” Leisure Studies 19 (4): 247–265. doi:10.1080/02614360050118823

- Jette, S. 2006. “Governing Risk, Exercising Caution: Western Medical Knowledge, Physical Activity and Pregnancy.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Lapadat, J. C. 2017. “Ethics in Autoethnography and Collaborative Autoethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 23 (8): 589–604. doi:10.1177/1077800417704462

- Leberman, S., and J. Hurst. 2023. “Is Training with Your Children a Double-Edged Sword?: Motherhood and Martial Arts.” In Motherhood and Sport: Collective Stories of Identity and Difference, edited by Lucy Spowart, and Kerry R. McGannon, 30–47. London: Routledge.

- Le Breton, D. 2000. “Playing Symbolically with Death in Extreme Sports.” Body & Society 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1177/1357034X00006001001

- Lupton, D., and L. Barclay. 1997. Constructing Fatherhood: Discourses and Experiences. London: Sage.

- McGannon, K., S. Graper, and J. McMahon. 2022. “Skating through Pregnancy and Motherhood: A Narrative Analysis of Digital Stories of Elite Figure Skating Expectant Mothers.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 59: 102126. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102126

- McGannon, K. J., and McMahon, J. 2022. “(Re)Storying Embodied Running and Motherhood: A Creative non-Fiction Approach.” Sport, Education and Society. 27 (8): 960–972. doi:10.1080/13573322.2021.1942821

- McGannon, K., J. McMahon, and C. Gonsalves. 2018. “Juggling Motherhood and Sport: A Qualitative Study of the Negotiation of Competitive Recreational Athlete Mother Identities.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 36: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.008

- McGannon, K., E. Tatarnic, and J. McMahon. 2019. “The Long and Winding Road: An Autobiographic Study of an Elite Athlete Mother’s Journey to Winning Gold.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 31 (4): 385–404. doi:10.1080/10413200.2018.1512535

- McLanahan, S., and G. Sandefur. 1997. Growing up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- McMahon, Jenny, Gilly-Elle Wiltshire, Kerry R. McGannon, and Christopher Rayner. 2020. “Children with Autism in a Sport and Physical Activity Context: A Collaborative Autoethnography by Two Parents Outlining Their Experiences.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (9): 1002–1014. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13573322.2019.1680535?needAccess=true&role=button.

- Meier, A., K. Musick, S. Flood, and R. Dunifon. 2016. “Mothering Experiences: How Single Parenthood and Employment Structure the Emotional Valence of Parenting.” Demography 53 (3): 649–674. doi:10.1007/s13524-016-0474-x

- Phoenix, C. 2010. “Seeing the World of Physical Culture: The Potential of Visual Methods for Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 2 (2): 93–108. doi:10.1080/19398441.2010.488017

- Phoenix, C., and E. Rich. 2017. “Visual Methods in Research.” In The Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, edited by Brett Smith and Andrew. C. Sparkes, London: Routledge.

- Prosser, J., and A. Loxley. 2008. “Introducing Visual Methods.” ESRC National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper. Available from: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/420/ [Accessed 20 May 2023].

- Raisborough, J. 2006. “Getting Onboard: Women, Access and Serious Leisure.” The Sociological Review. 54 (2): 242–262. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00612.x

- Rose, G. 2000. “Practising Photography: An Archive, a Study, Some Photographs and a Researcher.” Journal of Historical Geography 26 (4): 555–571. doi:10.1006/jhge.2000.0247

- Rose, G. 2007. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Scott, J. W. 1990. “Deconstructing Equality-Versus-Difference: Or, the Uses of Poststructuralist Theory for Feminism.” In Conflicts in Feminism, edited by M. Hirsch & E. F. Keller, 134–148. New York: Routledge.

- Segrave, J. 2000. “Sport as Escape.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 24 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1177/0193723500241005

- Saligheh, M., B. McNamara, and R. Rooney. 2016. “Perceived Barriers and Enablers of Physical Activity in Postpartum Women: A Qualitative Approach.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16 (1): 131. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0908-x

- Shaw, S. M., and D. Dawson. 2001. “Purposive Leisure: Examining Parental Discourses on Family Activities.” Leisure Sciences 23 (4): 217–231. doi:10.1080/01490400152809098

- Soule, K. E. 2018. “The Role of Sport in the Lives of Mothers of Young Children.” In Sport and Physical Activity across the Lifespan: Critical Perspectives, edited by R. A. Dionigi and M. Gard, 227–243. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sparkes, A. C. 2020. “Autoethnography: Accept, Revise, Reject? An Evaluative Self Reflects.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (2): 289–302. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1732453

- Spowart, L. 2021. “Snowboarding, Motherhood and Mobility.” Annals of Leisure Research 24 (2): 193–208. doi:10.1080/11745398.2019.1669472

- Spowart, L., and L. Burrows. 2016. “Negotiating Moral Terrain: Snowboarding Mothers.” In Women in Action Sport Cultures, edited by Holly Thorpe, and Rebecca Olive, 155–174. Palgrave Macmillan, London. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-45797-4_8

- Spowart, L., L. Burrows, S, and Shaw, S. 2010. “I Just Eat, Sleep and Dream of Surfing’: When Surfing Meets Motherhood.” Sport in Society 13 (7-8): 1186–1203. doi:10.1080/17430431003780179

- Spowart, L K. R. McGannon. (Eds) 2023. Motherhood and Sport: Collective Stories of Identity and Difference. London: Routledge.

- Spowart, L., and S. Pearson. 2023. “Pushing to the Limits: A Collaborative Autoethnography of Motherhood, Disability, Ambition, and Risk.” In Motyherhood and Sport: Collective Stories of Identity and Difference, edited by Lucy Spowart, and Kerry R. McGannon, 135–148. London: Routledge.

- Stebbins, R. 2009. “Serious Leisure and Work.” Sociology Compass 3 (5): 764–774. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00233.x

- Stefansen, K., I. Smette, and A. Strandbu. 2018. “Understanding the Increase in Parents’ Involvement in Organized Youth Sports.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1080/13573322.2016.1150834

- Tipton, M., and C. Bradford. 2014. “Moving in Extreme Environments: Open Water Swimming in Cold and Warm Water.” Extreme Physiology & Medicine 3 (12) doi:10.1186/2046-7648-3-12

- Walsh, B., E. Whittaker, C. Cronin, and A. Whitehead. 2018. “Net Mums’: A Narrative account of Participants’ Experiences within a Netball Intervention.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (5): 604–619. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2018.1449765

- Weaver, J. J., and J. M. Ussher. 1997. “How Motherhood Changes Life: A Discourse Analytic Study with Mothers of Young Children.” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 15 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1080/02646839708404533

- Zehl, R., A. Thiel, and S. Nagel. 2023. “Children’s Sport Opportunities and Parental Support in Single-Parent Families with a Lower Socio-Economic Status: An Ecological Perspective.” European Journal for Sport and Society 20 (2): 179–200. doi:10.1080/16138171.2022.2121248