Abstract

Although the world of sport is experiencing an increase in women’s participation and interest, it is still viewed as an inferior product when compared with men’s sport. In particular, Australian Rules Football has an extended history of excluding women from participatory opportunities, feeding into discriminatory stereotypes that football is for men. Guided by social role theory, we aimed to develop an in-depth understanding of the diversity in community perspectives surrounding women’s participation in football in Australia and the various factors that encourage and dissuade consumption of women’s football. The findings emphasise that negative attitudes toward women’s football are deeply rooted in societal and gender norms, whilst positive attitudes may be facilitated by progressive ideologies and a desire for gender equality more broadly. This study contributes to the existing literature by highlighting the complex relationship between general sports support and active consumerism in Australia.

As an industry, sport relies heavily on the engagement of the consumer to produce revenue, contributing to the sustainability of individual teams, clubs, and leagues (CitationDa Silva and Las Casas 2017). Historically, men have dominated the sporting industry in media attention, access to resources, participatory opportunities, and viewership (Symons et al. Citation2022); they are often considered the pinnacle for sports entertainment (Fink Citation2015; Levi et al. Citation2022). Recently, sports consumerism has seen a shift in the popularity of women’s professional sporting leagues, particularly in Australia where women’s participation has become more prevalent in sports that have traditionally been considered ‘male only’ – with the most notable being Australian Rules Football (i.e. football; Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh 2022). Reports from the Women’s Australian Football League (AFLW) demonstrate a substantial increase in women’s and girls’ participation (i.e. 790%), with the number of female community teams across Australia growing from 205 to 2,540 since 2010. Despite this, support and fanbases for the AFLW often fail to match the support that men’s football receives. For example, the 2022 AFLW Grand Final (i.e. Season 6) only attracted a crowd of 17,000 people (a decrease from previous years; AUSTADIUMS Citation2022), which is less than the average crowd of 23,600 for AFL men’s (AFLM) regular mid-season games in 2021 (AFL Tables 2022). Given the significant role that fans play in the endurance of sporting competitions (Mosalanezhad et al. Citation2020; Mumcu and Marley Citation2017), understanding the development of attitudes toward the sport is crucial to sustaining successful leagues and teams. However, despite some research in this area, our understanding of what influences these attitudes and motivates consumerism for women’s sport remains limited. Therefore, the purpose of the current research was to investigate the barriers and motivators surrounding support for women’s participation in an historically male-dominated sport. In developing an understanding of the factors that influence consumer behaviour, this research may be beneficial to key industry stakeholders in informing further marketing decisions and developing the financial sustainability of women’s football in Australia.

Australian rules football

Despite the popularity and influence of several football codes around the world (e.g. soccer, rugby), Australian Rules is considered the most prominent form of football in Australia (Willson et al. Citation2017), and the most ‘progressive’ football code in the world, regarding women’s out-of-play involvement and spectatorship (Nicholson et al. Citation2021). However, opportunities for women to participate in football have still been limited, when compared to opportunities for men. Although women’s interest and participation in football has been apparent since the early 1900s, the introduction of the Women’s Australian Football League (AFLW) in 2017 marked a period of socio-cultural significance in the football industry and broader Australian society, as women were, for the first time, given the opportunity to play football at a professional level.

However, systemic discrepancies such as shorter quarters and fewer players on the field in AFLW may feed into existing stereotypes and negative expectations, and inhibit the continued growth of women’s football, resulting in limited developmental opportunities. Moreover, the women’s league is only granted a 10-round season despite equal numbers of teams in both leagues (18). This not only limits the exposure of women’s football comparatively to men’s, who are allowed 23 rounds, but it also means that not all AFLW teams play each other within a season. Furthermore, AFLW matches are rarely exhibited at nationally recognised stadiums where AFLM games are played every round; even the 2022 (Season 7) AFLW Grand Final encountered a capacity of 8,000 people (Smale Citation2022) despite past AFLW Grand Finals averaging 23,000 spectators.

Sports consumerism

Attitudes toward women’s sport

Understanding the attitudes and perspectives of consumers has consistently been a key focus within sport consumerism research, justified by the understanding that such attitudes may be predictors of consumer behaviour (Funk, Alexandris, and McDonald Citation2022; Mumcu, Lough, and Barnes Citation2016). For example, it is suggested that stronger attitudes tend to motivate consumer behaviour, as they are more likely to watch or engage with their favourite and least favourite sports teams (Mumcu, Lough, and Barnes Citation2016). That is, both positive and negative attitudes may lead to an increase in consumer behaviour when there is a desire to see a specific team win or lose.

Despite numerous studies investigating attitudes and factors that influence sports consumerism (see for example, Funk et al. Citation2009; Funk and James Citation2004; Kim et al. Citation2019), there is a dearth of research that focuses specifically on attitudes towards women’s professional sport. Furthermore, such research is generally not in an Australian context, limiting generalisability to the unique sociocultural and historical context of Australian football. Given that research has emphasised that the factors that attract consumers to men’s sport are likely not an accurate reflection of the factors that attract consumers to women’s sport (Guest and Luijten Citation2018; Kim et al. Citation2019; Mumcu and Marley Citation2017; CitationThomson et al. 2022 ), developing an understanding of consumer attitudes towards women’s sport is essential for the continued success of the AFLW.

Previous findings

More generally in sports consumerism research, individual factors (e.g. entertainment, cost, escape, aesthetics, team satisfaction, and athlete skill), and group factors (e.g. social interaction, team and/or player attachment, family bonding, and group affiliation) have been found to motivate positive consumer behaviours (Malchrowicz-Mośko and Chlebosz Citation2019; Mumcu and Marley Citation2017; Sarstedt et al. Citation2014). Although less prevalent in the literature, an important finding in the consumerism of women’s sport relates to social reform (Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh 2022). This was demonstrated by Funk, Ridinger, and Moorman (Citation2003) and McDonald (Citation2000) suggesting that support for progressive ideologies (e.g. support for women’s opportunities) may encourage support for women’s sport. More recently, Delia’s (Citation2020) qualitative study found that the elements of gender equality (i.e. support for women’s sport, perception of a lack of priority for women’s sport, and resentment of men’s sport) were central to the meaning of team identification for fans of women’s sport. These findings were further evidenced by Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh (2022) who found that factors associated to social reform, such as opportunity for women and accessibility may positively influence perceptions of women’s football over time. These factors reflect a broader movement toward the desire for gender equality, and an industry that supports inclusivity, equal opportunity, and diversity (Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh 2022). Therefore, Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh (2022) suggested that the factors that have acted as barriers to women’s participation in sport (e.g. opportunity, accessibility), have the potential to motivate strong attitudes towards women’s sport (i.e. AFLW), a finding that is not reflected in the consumerism of men’s sport.

Gender roles and the AFLW

Women’s participation in sport has historically been stigmatised and associated with unfavourable stereotypes that they are athletically inferior to men (CitationLobpries et al. 2018 ). The patriarchal hierarchy in sport over time may be a result of socially constructed gender roles that have historically served to maintain a heteronormative segregation between the place of women and men in society. Social role theory (SRT; Eagly Citation1987) suggests that these gender roles developed from societal expectations of gendered behaviour; a consequence of the gender hierarchy within Western societies. Attitudes surrounding gender roles refer to perceptions or beliefs about how individuals should behave or contribute to society (Wu et al. Citation2023; Korabik et al. Citation2008). SRT purports that these expectations formed as a result of Correspondence Bias: the process of observing an individual’s behaviour and concluding traits and characteristics from this (Eagly and Wood Citation2012). For example, individual behaviour has often been interpreted as the result of physiological factors, rather than environmental or cultural influences. Although, these interpretations vary between cultures and are dependent on factors such as the social and economic role of genders within a specific culture (Giuliano Citation2018). In Western society gender roles have previously been determined through the division in labour, whereby women and men were allocated roles that were thought to align with physical characteristics. That is, women were assigned tasks that involved the home and child rearing duties, whereas men filled roles that required physical exertion (e.g. strength, endurance) and authority. When these more traditional assumptions about gender exist within the workforce, the subsequent power imbalance allows men greater authority, limiting the opportunities and resources for others.

Australia has seen some shift toward egalitarian gender ideals in contemporary society. For example, women are more likely than men to be university educated, and dual income households are now more common than traditional family systems in which men earn sole income (Hickson and Marshan Citation2023). However, Hickson and Marshan’s (Citation2023) research emphasized that Australian attitudes toward women in the workforce are largely conservative, demonstrating preservation of traditional gender ideologies – suggesting that stereotypical beliefs about the role of women are still prevalent in contemporary Australia. Given the sporting industry remains one of the only institutions in which individuals are segregated by a traditional gender binary, this potentially cultivates an environment in which traditional perspectives grounded in hegemonic masculinity may manifest and continue to limit the growth of women’s sport.

Sport has been acknowledged throughout history as an activity that aligns with a traditional understanding of masculinity (Bevan et al. Citation2021; Kidd Citation2013). That is, athletically desirable qualities such as speed, stamina, and physicality have generally been associated with men, with the accompanying assumption that women are physically inferior (Gentile, Boca, and Giammusso Citation2018). As such, women have generally been excluded from sports that were considered ‘masculine’, further contributing to the idea that women are not suited to contact sports. Because football is considered a traditionally ‘masculine’ sport, owing to its high intensity contact nature, women’s participation can be deemed a violation of traditional gender norms. Given that those who violate the traditional binary of gender roles are more likely to be perceived in a negative manner (Croft et al. Citation2021; Eagly Citation1987; Morgenroth and Ryan Citation2020; Reidy, Sloan, and Zeichner Citation2009), there is potential for individual ideals of gender norms to contribute to understandings of attitudes towards women’s sport. Research has demonstrated this rhetoric, as past findings suggest those who endorse more traditional ideals of gender may have more negative attitudes towards women’s sport (McCabe Citation2008), including AFLW (Glazbrook and Webb Citation2024). However, our understanding of gender role ideology and its impact on consumer attitudes regarding football not only remains limited, but also largely relies on quantitative methodology, and therefore lacks contextualized analysis of individual understandings of gender.

The current study

Although previous research has examined attitudes towards sport and sports consumerism (see Funk and James Citation2004; Guerstein Citation2017; Stevens and Rosenberger Citation2012; Wenger and Brown Citation2014), most has failed to investigate women’s professional sport, particularly in an Australian context. This is an important area given that research has suggested that factors that motivate positive consumer attitudes for men’s sport likely cannot be generalized to women’s sport and neglect the unique sociocultural context of Australian football. Therefore, the aim of this study was to qualitatively contextualize community perspectives on the AFLW to further understand underlying predictors of attitudes towards women’s football. We ask:

RQ1: What factors contribute to community support for the AFLW?

RQ2: What factors act as a barrier to community support for the AFLW?

RQ3: How do societal expectations of gender influence public attitudes towards the AFLW?

Method

Sample and data collection

Ethical approval was granted by the host university’s Human Ethics Committee (protocol #204855). A convenience sample of 357 participants from the Australian community was recruited through social media (i.e. Facebook, Instagram); they were presented with relevant study information and then participants were required to provide informed consent before they commenced the online survey. Due to incomplete surveys (i.e. participant dropout prior to the completion of optional qualitative items), the final sample size for this study was 300. Participant ages ranged from 18 to 70, and a majority (96%) of participants resided in South Australia (see for participant demographic information). Eligibility criteria required participants to be 18 years or older. Because the open-ended questions were opt-in items, each qualitative item had a different number of responses, ranging from 145 to 274 responses per item – with an overall total of 1760 responses within this study, from 300 participants. These responses ranged between 2 to 145 words.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the final sample.

The online survey

Data presented in this paper were generated from responses to ten open-ended survey items. These responses were collected from a larger survey of public attitudes towards the AFLW. The survey was administered via the online platform SurveyMonkey. Ten open-ended items from the original study are the focus of the current study, for the purpose of obtaining a deeper, more nuanced understanding of attitudes towards women’s football in Australia. The questions explored topics regarding consumption of women’s football and controversial issues surrounding the AFLW (e.g. gender pay gap, season length). These questions were designed to evoke strong opinions, in the sense that they allowed for unfiltered discussion of contentious topics on an anonymous platform.

Analytic method

Data were initially exported to IBM SPSS v.28, where descriptive statistics were calculated for participant demographics (). Qualitative data were exported to the computer program, Nvivo 13.

The data were analyzed using Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA; Braun and Clarke Citation2021), a method for identifying patterns of meaning across datasets whilst also accounting for the researcher’s relationship with those data and how their role may factor into interpretation. This method is considered appropriate for exploratory areas of research (Braun et al. Citation2013). Although our analysis identified superficial meaning surrounding participant attitudes towards the AFLW, we also sought to engage a more theory-driven approach. SRT (Eagly and Wood Citation2012) was utilized as a theoretical lens through which the data were understood, which is reflected in the interpretation of the findings. Our interest was not in individual responses to the qualitative items, but rather to develop a thorough understanding of participants’ perceptions of women’s football, by assessing patterns of meaning in participant responses. This research was underpinned by critical realism, which emphasizes the existence of individual, subjective perceptions of reality, but acknowledges that these are informed by contextual factors such as culture, values, and language (Braun and Clarke Citation2021).

Data analysis was conducted by the first author, and began through immersion with the data, whereby the dataset was read and reread multiple times. The second step, initial code generation, began with more semantic-level coding, identifying meaning that was explicitly expressed. Coding became more latent throughout the process as implicit meaning was extracted from the data, with the first author being guided through a social role theory lens, offering a framework for understanding individual perceptions of women’s football and how gender role ideology may influence attitudes towards women’s sports. All coding was completed manually, via the analytic software Nvivo. Codes were revised several times, particularly in relation to how the researcher’s own identity and experiences lent insight and perspective to that interpretation before the researcher progressed to theme generation. During the theme generation phases, data were transported from Nvivo, to hardcopy (i.e. paper), where the remainder of the analysis was completed. Candidate themes were then developed from the codes, and mapping techniques were utilized to ensure codes were coherent to the central organizing concept of each theme. Finally, all authors collaborated to review the primary researcher’s themes; this involved discussion of each definition, workshopping how the themes mapped together (including sub-themes within each), and how cohesively the sample extracts fit within those themes. Following the guidance of Braun and Clarke (Citation2021), numeric values are not presented in the findings due to the potential for values produced in the RTA process to be an inaccurate reflection of participant perceptions.

Findings

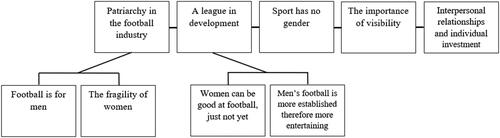

Overall, participant responses were predominantly supportive and favoured the existence of a women’s professional football league; however, lack of interest in following the AFLW was expressed. Five themes related to participants perceptions of the AFLW were generated (). Given a majority of participants were female, both positive and negative perspectives were expressed largely by female participants – with there being a larger proportion of female responses in discussion of visibility in sport. Similarly, male participants expressed both negative and positive perspectives (although less overall), however, were more prevalent in discourse regarding the physical capabilities of women and the entertainment value of women’s sport. Each of the five themes will be detailed in order of prevalence, and demonstrative quotes will be prefaced with the participant number, age, and then gender (i.e. P12- 23 y, F(emale) or M(ale)).

Theme 1: Patriarchy in the football industry

Perhaps the most prevalent theme across the dataset was the patriarchal influence within the Australian football industry. This concept was expressed in responses that indicated support for the AFLW, as well as those that indicated some level of opposition toward the AFLW. These polarising perspectives were demonstrative of both egalitarian and traditional gender attitudes through either acknowledgment of patriarchy within the industry, or through explicit or inadvertent sexist comments. When the idea of patriarchy or male domination was expressed more explicitly, it was generally with reference to how this limits the growth of women’s football: ‘The patriarchy supresses women’s opportunities to enter these physically demanding fields as they are both encouraged and punished for having children’ (P97-21 y, F) and ‘men don’t respect it [AFLW]. Men run the AFL so there is little chance to make it [AFLW] bigger’ (P223-38 y, F). Such responses were indicative of support for the AFLW but reflect an underlying frustration toward male domination within the football industry, suggesting a desire for equal investment in the women’s league. This perspective was further demonstrated in responses, especially in reference to those who were football fans, and supported the establishment of a women’s league but did not follow the AFLW: ‘It [AFLW] is just not telecasted or advertised like the men’s footy is’ (P26-26 y, M) and ‘great idea, great sport and great players, just not as in your face in the media so don’t have the same push to follow it’ (P124-24 y, F). These responses suggest that the constant media coverage of the AFLM makes it far more accessible to consumers when compared with the AFLW. This supports perceptions of the sporting industry as a space in which heteropatriarchal systems favour men, limiting the further development of women’s sport through marketing decisions that reduce the visibility of the AFLW.

Other responses demonstrated frustration toward the AFL regarding the pay gap between the two leagues. Some participants stated that, not only are women paid too little, but that men football players are paid too much: ‘the men get paid too much to play a game’ (P86-54 y, F) and ‘the wage gap angers me and puts me off supporting AFL’ (P230-22 y, F) and ‘the men should be paid less, some of those salaries are ridiculous. They’re not saving lives, they’re playing sport’ (P120-53 y, F). These responses demonstrate progressive ideologies through the resistance of generally normalised industry practices that emphasize investment solely in the talent of men.

Subtheme 1A: It’s a man’s sport

Further responses under the patriarchy theme were exemplary of more explicit sexism, in which participants suggested that women should not participate in activities that are perceived as masculine: ‘I do not like aggression in any form but dislike it most from women’ (P86-54 y, F). Such commentary demonstrates traditional gender attitudes through the suggestion that particular traits are gender specific, which is furthered through the enforcement of stereotypical notions of women as passive beings.

More negative perceptions of women’s football demonstrated a patriarchal stance as justification for the male dominance within the football industry. Many appeared to hold heteropatriarchal beliefs, insinuating that this gender hierarchy should be maintained by explicitly stating opposition to women’s football. For example, ‘AFL has been known as a man’s sport and will always be known as that’ (P144-49 y, F) and ‘Doesn’t look right. Has always been a man’s game and should stay that way’ (P183-49 y, F). By extension, it was suggested that the football industry should be excused from promoting inclusivity: ‘I’m all for equality, just not in football’ (P166-49 y, F). Such responses reflect the perception of the football industry as a male space and are demonstrative of a desire for this to continue. Through communicating discomfort with women’s participation in football, these participants demonstrated adherence and support for a traditional gender binary – demonstrating support for an industry that promotes the superiority of men. This was a perspective that was developed further by the rhetoric that women’s football skills were inferior to men: ‘It [AFLW] is really hard to watch. The skills are inconsistent and feels like an u12’s [under the age of 12] game where it’s scrum footy’ (P359-23 y, M). Therefore, women’s football was also seen to not be worthy of funding: ‘I don’t want to see women playing footy. I wouldn’t waste my time or money’ (P42-48 y, F) and ‘I don’t believe there is a need for women in football, so I don’t see a need to pay women’ (P43-48 y, F). Unlike other themes, these responses reflect an underlying belief that women are not capable of developing elite skills and as such, should not be included professionally:

I think the idea is there but so much history lies within AFL and I feel like I won’t ever live up to the standard. Men are elite at the game and execute skills whereas the women, not so much. I am personally just used to it being a Man’s sport (P146-26, F).

Subtheme 1B: The fragility of women

A particularly salient feature under Theme 1 was the perceived fragility of women. This concept extends the notion of maintaining the male dominance within the football industry, by suggesting that women are inherently incapable of excelling in high contact or ‘masculine’ sports due to biological or physiological factors. For example, ‘I don’t enjoy watching it [AFLW] as girls aren’t physically as athletic as men and can’t do the cool physical side like the speckies, big marks, etc. that I enjoy watching’ (P277-27 y, F) and ‘I think physically women are not built to play such a high level of contact sport’ (P263-50 y, F). The responses within this subtheme were indicative of a belief that the AFLW is a lesser standard simply because women’s physiology does not allow for the same athleticism as men, rather than differences in developmental exposure. As such, men’s football is perceived to be more entertaining: ‘[AFLM is] much more entertaining. More physicality. Biological makeup means men will always be bigger, stronger, faster which are key components of football’ (P134-34 y, M) and:

Genetics of the human give males much more strength, power, speed, physical size than that of a female. It makes the male game much more exciting to watch. Therefore will bring bigger crowds and more money. Therefore they should be paid more (P134-34y, M).

‘the training and upkeep that needs to be maintained during that period is quite taxing on the body and would be far more strenuous for women opposed to men, as men aren’t having to deal with menstrual cycles on top of being able to perform at that elite level’ (P26-26 y, M).

Responses within this subtheme reflect the attitude that football is a sport best suited to men, however, emphasis is placed on female bodies and how biology seemingly limits the athletic capabilities of women in sport. These perspectives demonstrate traditional gender attitudes through a desire to comply with a gender binary that is justified by perceived the perception of innate physical attributes – with these attributes assigned in a manner that warrants the need to protect women from spaces that may be considered dangerous (i.e. the idea of innate characteristics of men reflect physical dominance). Such ideas have been paralleled throughout the history of women’s sport and exemplify common stereotypes that have served to limit women athletes. Discourse surrounding the idea of women as physically inferior is particularly limiting as it allows consumers to justify their misogyny through either the idea that women’s football will not be entertaining enough, or, through performative concern for the safety of women in contact sport.

Theme 2: A league in development

The idea of the AFLW as a ‘new league’ was prominent in many participants’ responses, with reference to the impact of this for consumers. Some participants expressed that whilst the league is still developing, this indicates that it will continue to improve as it becomes more established. In contrast, other participants were more focused on the present state of the industry, implying that men’s football is already established, making it more attractive to the consumer.

Subtheme 2A: Women can be good at football, just not yet

Whilst a majority of participants expressed support for the establishment of the AFLW, many of those who described themselves as football fans did not follow the women’s league. The key concept within this subtheme was the notion that perceptions of the AFLW presenting a lower standard of football were attributed only to developmental discrepancies and not ‘inherent’ gender differences. For instance: ‘Girls not having had as much experience with footy means the games are less exciting. It will continue to improve’ (P85-26 y, F) and:

‘[AFLW] hasn’t been around long enough to be compared to AFL[M] yet. You are comparing chick’s [sic] that have played “league” for four years vs some men who have played for 10 years, the game won’t be at a consistent skill level to the men on a regular basis I don’t feel for a few more years yet’ (P35-39 y, F).

Contrary to many responses within Theme 1, these examples emphasize the understanding that female football players have not been granted the same developmental opportunities and pathways as their male counterparts. So, whilst women’s football is described here as less entertaining, it reflects an underlying belief that women’s football has the potential for continual improvement.

Responses further demonstrated an understanding for the development of women’s football but suggested that the establishment of the league should have been implemented more gradually: ‘Love watching but I think the girls need to be patient with the development. I think they are expecting too much too soon’ (P100-60 y, F). This idea was justified by the argument that the current talent pool is too small to fuel an entire league; given limited opportunities for women and girls to participate in grassroots football previously: ‘The talent pool [is] being spread too thin’ (P106-30 y, M) and ‘I think it is overly [sic] a good idea, I just feel that it is getting too big too quick which doesn’t allow the talent available which makes some games blowouts during the season due to the experience’ (P268-23 y, M). These responses are indicative of an overall support for the league but, demonstrate a nuanced understanding of the impact of developmental discrepancies and how these limit the growth of women’s football, from a spectator perspective.

Subtheme 2b: Men’s football is more established, and therefore more entertaining

An extension of the previous subtheme, subtheme 2b incorporates the understanding of the AFLW as a developing league, with emphasis on the idea that men’s football is more entertaining. Reponses seemed to suggest people would rather invest in men’s football because it is already established: ‘I believe it’s [AFLM] more exciting and worthwhile. There’s [sic] more matches. Better atmosphere. Greater competition?’ (P131-23 y, F) and ‘at this stage the AFLW is not up to the standard if [sic] AFLM. AFLM is a superior product…’ (P11-24 y, M). This corresponds with previous themes through the insinuation that consumers seek convenient entertainment and are less inclined to be interested in products that may require time and effort to engage with (e.g. a sports league still in development).

The perception of AFLW as less entertaining also appeared to impact participants’ view on ticket pricing, with many implying that women’s football is not worth the same price as men’s football: ‘The quality and standard of the game is nowhere near the same. I would not be interested in paying more to see a local footy vs. AFL[M] match for the same reason’ (P24-43 y, F) and ‘Until the [AFLW] comp becomes more cut throat and competitive there is no chance I would pay more than $20 to get into a game’ (P301-22 y, M). These responses indicate that for some people football is purely a form of entertainment and should be treated as such, although fail to acknowledge that the current rate of entrance to a women’s game is only $10 AUD (compared with men’s tickets often being priced upwards of $100), and therefore do not discuss if this is considered a fair cost of entry.

Continuing from the idea of entertainment, participants noted factors relevant to AFLM, that have not yet been extended to the women’s league: ‘Can’t put multis on AFLW games’ (P282-19 y, M) and ‘[There’s] no AFL[W] fantasy [football league]’ (P255-22 y, M) and ‘I only follow the men’s comp because I am involved in footy tipping at work’ (P14-43 y, F). These responses further support the concept of football as entertainment, whilst highlighting specific discrepancies between the leagues, which may serve as a barrier to support for the AFLW. Considering entertainment factors adjacent to the sport is a strategy that could be beneficial in the further development of the women’s league, as these are likely important points of attraction for some consumers.

Theme 3: Sport has no gender

Another perspective across the dataset was the belief that sporting opportunities should not be determined on the basis of gender. In contrast to previous responses promoting traditional gender attitudes, sport was seen as something that should be made accessible to everyone: ‘Everyone should have the opportunity to play whatever sport they choose’ (P60-63 y, F) and ‘I will support anything that encourages both men and women to play sports’ (P188-39 y, F). These responses demonstrate egalitarian ideals of gender through a desire for equal opportunity within the industry, which was further referenced in responses that discussed the benefits of playing sport: ‘Why shouldn’t it [women’s football] be allowed to happen? Sport is a healthy thing to be involved with, no matter your gender. If women want to play football, good’ (P147- 30 y, M) – suggesting that the significance of sport for some participants exists beyond factors related purely to entertainment. Furthermore, some respondents suggested that Australia should not be recognised for a sport that is only inclusive of one gender: ‘both men and women have a right to play for a national sporting code’ (P32-57 y, F) and ‘Just good to have women involved in a country wide sport that is recognised by the world for being our sport’ (P25-26 y, M). The important distinction in comparing these responses to the previous themes is the dialogue of ‘our’ sport referring to Australia as a whole, rather than referring to just men – a difference that insinuates that not all participants perceived football as a space that is inherently for men.

An opinion offered by some participants was a lack of perceived difference between women’s and men’s football. It was understood that as a spectator, football is enjoyable because the sport itself is entertaining, not necessarily because of who is playing. This opinion contrasts with those who suggested women are physically incapable of excelling in football: ‘A football game is a football game. Same concept but with different players’ (P182-18 y, F) and ‘I am watching the same sport – just with the opposite sex’ (P299-46 y, F). This was expressed further with participants explicitly stating a generalised interest in football, with no reference to gender: ‘I just love footy’ (P172-55 y, F) and ‘I just like to watch high level sport’ (P63-62 y, F).

These opinions were extended into discussions of pay differences between women and men, with some participants suggesting that pay rates should not be based on gender: ‘There should never be any [pay] gap in any profession. Sex should not be a barrier. Ability and skills show no gender bias’ (P33-57y, F) and ‘I’m going to watch people play a tough sport for my entertainment, they deserve to be paid the same’ (P252-28 y, F). These responses reflect resistance to the contentious issue of the current gender-based wage gap in the football industry, which indicates more broadly, support for equal opportunity for everyone in sport.

Theme 4: The importance of visibility

Another common perspective across the dataset was the perception of women’s football as a space of inclusivity and diversity. This was referenced in regard to both players and spectators, and appeared to be a particularly important motivating factor for support for the AFLW: ‘The crowds are far more welcoming and inclusive than an AFLM game, and the women are strong and brave, and do a brilliant job of promoting themselves and the game’ (P297-28 y, F) and ‘I also see it as a more inclusive space compared to the men especially in terms of the lgbtq + community and engagement with grassroots’ (P237-19 y, F). This discourse not only communicates the positive aspects of the women’s league that attract consumers, but also references factors that may dissuade consumption of men’s football. This suggests that consumers may be less likely to engage with AFLW if they do not feel included or accepted by a sporting league, or the league’s interests are inconsistent with consumer values.

This idea was supported further by responses that emphasized an aversion to the football industry’s limited diversity: ‘The AFL is such a male driven industry and assumably the biggest in Australia, which I personally find extremely off putting due to the lack of diversity’ (P8-19 y, F). In contrast, the inclusive environment cultivated by the AFLW also appeared to act as a barrier to support for the women’s league for those participants demonstrating more conservative ideologies: [what’s the biggest issue within the AFLW?] ‘the lesbian and sexuality promotion’ (P86-54 y, F) – playing into common stereotypes surrounding the sexuality of women in sporting contexts.

The importance of the visibility of quality role models was an idea prominent in many responses. Responses indicated a preference for AFLW players as role models, which was supported further by the suggestion that certain AFLM players should not be in the spotlight, insinuating that simply being an elite athlete is not an adequate prerequisite to being a quality role model:

‘They [AFLW players] are amazing athletes and role models, they deserve the full spotlight. It’s about the game again and unlike the male clubs which are full ripe with a culture of toxic masculinity. I do not want my son to idealize them. These women just get in there and get on with the game whilst holding down their day jobs’ (P173-40 y, F) and:

‘People tend to place sports stars on pedestals and idolize them, and while it shouldn’t necessarily be the case, I think AFLW players (and female sportspeople in general) do a better job of accepting the role model tag. Because they realize how important it is to be visible, to create a pathway for others’ (P297-28 y, F).

Further responses alluded to the importance of visible role models for girls and women, so that they can aspire to be professional football players. The role of female athletes in creating and promoting pathways for women’s sport and younger athletes was another popular factor in support of the AFLW: ‘It is so important young girls can see that girls are just as capable to play the sport of AFL at the highest level too’ (P173-26 y, F) and ‘It is so apparent the steps taken by the AFLW, so far, have thrilled and captured girl’s imaginations across Australia’ (P16-67 y, F). Some responses also made reference to the history of the football industry in providing limited opportunities for girls and women: ‘I wanted to play footy when I was younger and never could so I think it’s great that girls can be involved in the sport now’ (P324-24 y, F) and ‘Seeing women play sports is what I wish I had seen as a young girl’ (P199-23 y, F). This suggests the importance of providing visible role models to increase women and girls’ participation in grassroots football and offer aspirational goals to the next generation of women football players.

Theme 5: Interpersonal relationships and individual investment

It was reported by participants that interest in and engagement with sport were associated with social factors. That is, many participants stated that they only engaged in sports consumerism when those around them were doing the same. This appeared to be a significant barrier to support for the AFLW: ‘Only moderately interested in AFL and follow to converse with family. They do not follow AFLW’ (P308-50 y, F).

‘I usually watch the footy when I hear through word of mouth that a game is on. I’m rarely up to date on what games are on anyway, but AFL Mens is the only one I hear about through friend’s parents, or mates. Usually go watch it at the pub or at friends house, and in those cases it’s always the men’s league on’ (P232-23 y, F).

These responses emphasize a lack of desire to seek out AFLW related content, reflecting a broader disinterest in women’s football. Furthermore, these responses also suggest attending or watching sport may be considered a social event for some people, rather than a direct source of entertainment, but were biased toward AFLM due to broader factors around consumerism rather than the nature of the game itself. Unlike entertainment-value, these factors reflect more personal connections to identifying as a football fan. For example, several participants emphasized their investment in a specific football team: ‘My team doesn’t have an AFLW side’ (P20-59 y, F) and ‘At the moment my club doesn’t have a AFLW team so I’m less likely to watch it’ (P21-59 y, F). Although the AFLW now has a team equivalent to each AFLM team, therefore rectifying this barrier, these responses highlight the importance of team loyalty in sports consumerism. This finding suggests that the responsibility of marketing and promotion of women’s football falls not only with the AFL, but also the individual teams within the league.

Participants also implied that interest in specific players was an important factor in support of football: ‘I don’t know the players so I find it hard to follow/support’ (P249-19 y, F) and ‘I have no vested interest in the players themselves’ (P71-20 y, M). The lack of interest in players could be a consequence of the limited coverage of AFLW in comparison to AFLM more generally, or the marketing of AFLM players as celebrities versus AFLW players as regular people. Contrary to previous research suggesting that women’s sport media coverage focuses too much on the players as people rather than athletes, participants stating a lack of knowledge of the individual players suggests that this type of media attention may be beneficial in facilitating parasocial relationships evident when athletes are viewed as celebrities – or, that additional media coverage of AFLW players is required more broadly. Some participants alluded to the desire to watch football stemmed from physical attraction to the players: ‘As a straight woman, I am generally watching the AFLM to view the men as opposed to the sport’ (P221-21 y, F). The responses within this theme suggest some spectators of football are less interested in football more generally, and instead are drawn in by specific aspects of the sport that may make the game appealing.

Discussion

Guided by social role theory, the aim of the current study was to develop a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to public support for the AFLW, as well as the factors that may act as a barrier to this support. The findings outline the nuance within perceptions of the AFLW and emphasize specific barriers and motivators to not only support for the league, but also active consumer engagement. Although the findings suggest a greater proportion of individuals endorse the existence of the AFLW, there was a clear disconnect between this support and a desire to engage in consumerism of women’s football. This disconnect acts as an opportunity for marketing efforts to not only increase interest for the league, but close the gap between support and consumerism of the women’s league.

Participants emphasized support for women’s football, but discussed several barriers, or perceived barriers, that appeared to prevent them from active engagement with the AFLW. For example, the claim that women’s football receives less media attention than men’s football seemed to be a prominent barrier to league engagement, as it provided less opportunity to stimulate interest (e.g. not being exposed to unsolicited AFLW related media). AFLW related content is not as prevalent in mainstream media and therefore is not as accessible, when compared to the AFLM who dominate Australian media platforms (Vinall Citation2021). This reflects a long-established discrepancy in the sporting industry in which women’s sport globally receives substantially less coverage than men’s sport (Sherwood et al. Citation2019; Cooky et al. Citation2021). Such discrepancies are likely a consequence of the gendered state of the sporting industry, wherein the imbalance of power allows men greater access to the resources necessary (e.g. funding) to dominate media and news outlets (Fink Citation2015; Petty and Pope Citation2018; Sherwood et al. 2019). The continuation of men’s football as the most prevalent league discussed in the media is a type of Symbolic Annihilation (Fink Citation2015). That is, although the limited mainstream media coverage of women’s football does not inhibit people from exploring alternative platforms through which to engage with the AFLW, it suggests to the consumer that women’s football is less important (Cooky et al. Citation2021) which is consistent with the barriers identified in the current findings.

The notion of football as a social event coincides with previous sports consumerism research that demonstrated that social interaction is a predictor of positive sports consumer behaviour (Funk and James Citation2006; Mumcu and Marley Citation2017; Sainz-de-Baranda, Adá-Lameiras, and Blanco-Ruiz Citation2020). However, participants noted that the exposure to AFLW was, at times, only promoted by friends and/or family, many of which were predominantly referencing AFLM, reflecting the current state of the industry in which men’s football is more popular (Morgan 2020). The implication of consumerism of AFLW content being motivated by social connection/experience alone, is that those not genuinely invested in the sport may be less likely to engage in impactful consumer behaviour such as attending matches or buying merchandise, potentially having a cyclical impact on the women’s league more broadly. That is, not only does a lowered investment in promoting AFLW result in less access and more reliance on individual interest and social events for promotion, reducing consumerism, so too does the lack of consumerism from potential spectators reduce the funds going into the league to grow it, resulting in a stunted growth in AFLW. Previous research suggests that continuous exposure may aid in attracting consumers to less popular sports (Sedky, Kortam, and AbouAish Citation2022). This suggests that marketing the AFLW equally to the AFLM can be an integral part of reducing the barriers to more active engagement from consumers.

The impact of gender norms

The influence of gender role ideology on participants’ attitudes towards the AFLW was prevalent throughout the data and appeared to have a meaningful impact on support for the league. This was expressed in many instances, and clearly emphasized the perception of the football industry as a predominantly male space. Social role theory (SRT) helps to understand these sentiments, with socially constructed gender roles resulting in the belief that women and men cannot or should not occupy the same spaces, due to the perceived binary of gender (i.e. the ideology that women are feminine, and men are masculine; Eagly and Wood Citation2012). Given that football has historically been a male dominated sport (Willson et al. Citation2017), stereotyping may have resulted in the perception that professional football is for men, meaning the AFLW rejects traditional gender ideologies. As such, those with more traditional understandings of gender may be unlikely to be motivated to expose themselves to the AFLW, regardless of the quality of play, with increased exposure often found as an antidote to stereotype maintenance (FitzGerald et al. Citation2019; Gonzalez et al. Citation2021; Neubaum et al. Citation2020). This is further limited by the reduced exposure to women’s sport, reinforcing this gendered perception,which in turn suggests that the marketing of AFLW may lead to increased support for women’s football, offering opportunities to challenge the current stereotypes.

The impact of prejudice against women in AFL was also exemplified in the data, with participants expressing the opinion that women are physically incapable of achieving the same level of athleticism as men. This idea appeared to serve as a barrier to engagement with the AFLW, as women’s football was subsequently described as less entertaining. Traditional ideals of gender are based in the idea that men and women’s physical ability is incongruent (Eagly and Wood Citation2012), likely providing some explanation for the perception that characteristics required of football players are antithetical with the perceived innate characteristics of women. This particular perspective is demonstrative of essentialist ideologies that position women as inherently less athletic than men (Allison and Love Citation2022; Messner Citation2011). Though potentially more subtle in contemporary society, perceptions of women as physically inferior appear to be an enduring stereotype, evident in discussions surrounding women’s involvement in sports deemed conventionally masculine (Pape 2023; Dorken and Giles Citation2011), coinciding with the current findings.

The idea that women are physically inferior was endorsed further by the suggestion that women’s bodies cannot tolerate the intensity of a highly physical, contact sport such as football, an attitude common to other sports requiring physical exertion (e.g. bodybuilding (Rahbari Citation2019) and rugby (Kanemasu and Johnson Citation2019)). Previous literature suggests the framing women’s bodies as incongruent with professional sport allows for the manifestation of hegemonic ideologies that centre the sporting industry around men (Pape 2023). Therefore, enduring perspectives surround the suitability of women to football, as demonstrated in the findings, may continue to limit the development of the women’s league. However, promotion and advertising that markets football as a sport for everyone may help to aid stereotyping of the industry as a predominantly masculine space.

Furthermore, the belief that women are at higher physical risk in sport has been the topic of much biomedical discourse regarding injuries in women’s sport (see Fortington and Finch Citation2016; Gill et al. Citation2021; Rolley et al. Citation2022). Fox et al. (Citation2020) examined the prevalence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries within the AFLW, noting that although females are more likely than males to sustain such injuries, there is an overemphasis on the discussion of this issue being the result of biological differences. Rather, it was suggested that such injuries could, to some extent, be attributed to the recent establishment of the AFLW (Fox et al. Citation2020), in that less experienced women footballers have not been granted the same rigorous developmental opportunities as men, coupled with a shorter pre-season training period, resulting in the potential for an increased risk of injury. At times participants expressed concern for the safety of women footballers (often not a concern for male players). This view is exemplary of benevolent sexism whereby misogyny is disguised as concern. That is, the concern expressed is actually rooted in the paternalistic idea that women are too fragile and need to be protected (Gothreau, Arceneaux, and Friesen Citation2022).

Moreover, traditional gender attitudes may result in a resistance toward anything beyond the heteronormative status quo, including the Queer community. Despite percentages of sexual minority athletes within the AFLW reflecting similar proportions of sexual diversity within the general population (e.g. 15–20%; Denison Citation2021), the AFLW’s support for sexual minority equality has often been associated with negative misconceptions. As reflected in the findings, the presence of the sexual and gender diversities (i.e. non-binary athletes) within the AFLW and the vocalized platform that these athletes are given (Sherwood et al. 2019), in conjunction with the common stereotype that women who play football are part of a sexual minority group (Booth and Pavlidis Citation2021), may act as a barrier to support for the AFLW. Perceived gender roles provide a framework for understanding this barrier, as Queer sexualities threaten the boundaries of traditional perceptions of femininity and masculinity (Booth and Pavlidis Citation2021; Kowalski and Scheitle Citation2020), and this coupled with the concept of women in a male dominated field, results in a particularly unappealing spectacle for those with more traditional gender ideology. Football as a sport is glorified despite inviting an exclusionary culture, for example, with AFLM being one of the only major sporting leagues with no openly non-heterosexual player. This cultivates an ideal environment for sports fans with a more conservative ideology, whilst serving to subliminally reinforce prejudice against sexual minorities by not creating a safe environment for these individuals to exist.

Engagement & support for the AFLW

Motivation for AFLW support and engagement appeared to be predetermined by a broader desire for gender equality. That is, women’s football was perceived by some as equal to men’s football and as such, equally deserving of the same resources, funding, and publicity, coinciding with previous findings (Delia Citation2020; Funk, Ridinger, and Moorman Citation2003; Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh 2022). This acknowledgement was coupled with the understanding that developmental discrepancies have limited women in their ability to foster elite football skills that men have been allowed the opportunity to do for decades. Therefore, perceived differences in football quality between women and men were attributed to developmental discrepancies rather than the fault of women themselves.

Participants who were more inclined to both support the league and engage in consumer behaviour demonstrated an egalitarian understanding of gender. Egalitarian gender roles are derived from the belief that every person should be provided with equal access to opportunities and rights regardless of gender identity, sex, or sexuality – without exception (Kulik Citation2018). As such, egalitarian ideals do not assign rigid roles to specific individuals, given the same standard of treatment is applied to all people. These concepts were evident throughout the aforementioned themes, particularly concerning a support for gender equality and equal opportunity. This finding is consistent with previous research (Delia Citation2020; Funk, Ridinger, and Moorman Citation2003; Wear, Naraine, and Bakhsh 2022) in which support for women’s opportunity was found to contribute to more positive attitudes, and identification with women’s sport. This indicates that a promotion of equal opportunities within the sporting industry may be beneficial in increasing support for the AFLW.

Providing positive role models for women in sport not only encourages overall grassroots participation, but also contributes to normalizing the place of women in traditionally male spaces, such as the football industry, which may further promote engagement with the AFLW. The discussion of AFLW players as role models was justified further by the insinuation that many of their AFLM counterparts should not be considered role models. This conjecture has been prevalent in the media and community, fuelled by allegations of violence, drug use, and sensationalized drinking culture (Chandrasekera Citation2019; Gratten Citation2011). Similarly, several participants communicated resentment towards the AFLM, and how these athletes are glorified. However, resentment itself was not necessarily a motivator for engagement with the AFLW, but rather a by-product of a desire for gender equality more generally. This finding is similar to that of Delia (Citation2020) wherein the avoidance of consuming men’s sport was seen by participants as a means to contribute to promoting gender equality. As such, the domains in which men are given precedence (e.g. funding, media, pay) allow consumers to identify specific areas for improvement to work towards, and further promote the goal of equality. These findings reflect the importance of providing positive AFLW role models and representation, to market women’s football as a product that encourages healthy participation in sport.

Further motivation for league engagement and support identified from the themes referenced the environment of inclusivity and diversity cultivated by the AFLW. This is consistent with previous findings, which suggested the importance of inclusive fan culture and environments as a motivational factor in consumption, in the context of successful women’s professional team sports (Guest and Luijten Citation2018). This motivation appeared to extend from the sense of resentment toward men’s sport, as participants emphasized the lack of diversity within AFLM as a factor that discouraged from engaging with men’s football. This issue has been widely discussed in the media, particularly regarding examples of racism and sexism, which often appear to be engrained in the culture of Australian football (Klugman Citation2019). In contrast, the AFLW appear to have earnt a reputation of inclusion and activism for the minority groups within the league. As discussed by participants, the advocation for the LGB community through the introduction of the annual Pride Round, and the positive representation of Queer athletes. In contrast to the AFLM, which is one of the only major sporting leagues in which no player is openly non-heterosexual (Booth and Pavlidis Citation2021), the AFLW have successfully developed a space in which minority fans and players alike feel accepted, therefore appealing to consumers who believe in the importance of inclusion. This coincides with Guest and Luijten (Citation2018) research, which emphasized the importance of inclusive environments as motivational factors for Queer, and progressive fans.

Stakeholder recommendations, limitations, and future research

Several practical implications can be drawn from the findings, including the importance of exposure for improving consumer engagement. Sports marketers may find it beneficial to increase publicity for the AFLW, which could be implemented in unison with advertisements for the AFLM to normalize the discourse of the two as equals. Ensuring broad exposure is important as consumers should not be required to actively seek out content for women’s sport (unlike AFLM which is often continually streaming during the season). The importance of this was demonstrated in the 2023 Women’s World Cup (soccer), in which adequate financial backing and appropriate media attention resulted in record breaking consumer interest in women’s soccer in Australia (Lewin Citation2023). Similarly in cricket, the 2023 Women’s Ashes experienced record breaking attendance and engagement (with test match viewership increasing 400% from 2019), as a result of factors such as sponsorship, media engagement, and support from relevant governing bodies within the sport (Reus Citation2023). This success of each of these events not only demonstrates the potential for women’s sporting leagues as financially viable products, but the importance of adequate investment to facilitate this outcome.

Furthermore, to maintain the current consumer attraction to the league, sports marketers should continue to emphasize the AFLW’s culture of inclusivity and diversity; an important approach in sports marketing when consumers are from the Queer community (Melton and MacCharles Citation2021). This is especially relevant given the lack of diversity and inclusion within the AFLM appears to act as a barrier to consumption of men’s football. Furthermore, although past research indicates men are less likely than others to support women’s sport, a large portion of participant responses opposing the AFLW, came from women participants. This finding indicates the assumption women will be interested in the AFLW, simply because they are women, is not adequate in the promotion of a successful and enduring league. Given a significant portion of AFLM supporters are women (Lenkic and Hess Citation2016), this finding further supports the need for media surrounding the AFLW to mirror the amplified delivery of men’s football.

The qualitative approach contributes rich contextualized experience to the body of knowledge on how social role theory can be used to understand the development of attitudes towards women in sport. Furthermore, the method of RTA allowed for the interpretation of more subtle and implicit forms of sexism, which may be difficult to garner from quantitative designs. Future researchers would likely benefit from investigating the phenomenon of implicit sexism more thoroughly, to aid the development of marketing and intervention strategies. Despite the novel contribution of this study to understanding attitudes towards women’s football, there are limitations to be considered when interpreting the findings. Although RTA is generally more concerned with transferability than generalizability (Braun and Clarke Citation2021), it is important to emphasize that the sample within the current study included an overrepresentation of women and South Australian (SA) residents, meaning results should be considered within this context (e.g. with SA being a predominantly Labor voting state (AEC 2022), indicating that those within this state may be more socially progressive). Given the proclivity of Australian men in engaging with football more generally, future researchers may also find it beneficial to further represent this population within this research area. Furthermore, the main SA team within the AFLW (i.e. the Adelaide Crows), has been largely successful, meaning the context in which women’s football has been consumed in SA thus far may have been more positive, and indicative of an overall successful league, which may contribute to positive attitudes towards the AFLW for South Australians. Future research should aim to include a more diverse sample to capture the unique contexts and experiences of the broader national population. The findings from this study could be used within future research, to inform the development of intervention strategies that aim to improve consumerism and attitudes surrounding the AFLW. Such strategies could target the promotion and marketing of the AFLW through advertising that positions women’s sport as exciting and newsworthy, whilst dismantling stereotypical perceptions of women as inferior athletes. Such advertisements could be designed to target both overt and implicit sexist attitudes that may limit consumer interest and motivation to engage with women’s football, by extension contributing to the financial sustainability of the professional league.

Conclusion

Despite the present study demonstrating support for the AFLW, the prevalence of negative attitudes is still evident, including both overt and subtle gender inequality. The imbalance of consumerism between women’s and men’s football in Australia underlines the need for ongoing research to further understand the barriers to support and engagement with the AFLW. The prevalence of traditional gender ideology within the context of football continues to inhibit the further growth of women’s football and reinforces stereotypical ideals that suggest women are inferior athletes. However, the identification of several motivational factors has provided context for the success of the AFLW since its establishment and allows for an understanding of how this can be sustained or improved further. The barriers and motivators to consumption of women’s and men’s football emphasize the importance of implementing unique and contextualized approaches to sports marketing for each league. To continually contribute to the promotion and success of the AFLW, it is essential to understand the attitudes surrounding support for women’s football and attempt to bridge the gap between general support and active engagement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to ethical limitations, the data associated with this research may be available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- AFL Tables. 2022. “Attendances 1921–2022.” December 19, 2023. https://afltables.com/I/crowds/summary.html.

- Allison, R., and A. Love. 2022. “We All Play Pretty Much the Same, except…”: Gender-Integrated Quidditch and the Persistence of Essentialist Ideology.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 51 (3): 347–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912416211040240

- AUSTADIUMS. 2022. “AFLW Attendance.” AUSTADIUMS, Australian Stadiums & Sport. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.austadiums.com/sport/comp/I.

- Australian Electoral Commission. 2022. “2022 Federal Election Results Map; South Australia.” Australian Electoral Commission. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://www.aec.gov.au/Elections/federal_elections/2022/files/maps/SA-2022-results-map.pdf.

- Bevan, N., C. Drummond, L. Abery, S. Elliott, J. Pennesi, I. Prichard, L. K. Lewis, and M. Drummond. 2021. “More Opportunities, Same Challenges: Adolescent Girls in Sports That Traditionally Constructed as Masculine.” Sport, Education and Society 26 (6): 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1768525

- Booth, K., and A. Pavlidis. 2021. “Clubhouses and Locker Rooms: Sexuality, Gender and the Growing Participation of Women and Gender Diverse People in Australian Football.” Annals of Leisure Research 26 (4): 628–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2021.2019594

- Braun, Vi.,G. Tricklebank, andV. Clarke. 2013. “It Shouldn’t Stick out from Your Bikini at the Beach.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 37 (4): 478–493. doi: 10.1177/0361684313492950.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Chandrasekera, P. 2019. “Should footy players be role models?” The Roar. https://www.theroar.com.au/2019/04/10/should-footy-players-be-role-models/

- Cooky, C., L. D. Council, M. A. Mears, and M. A. Messner. 2021. “One and Done: The Long Eclipse of Women’s Televised Sports, 1989–2019.” Communication & Sport 9 (3): 347–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795211003524

- Croft, A., C. Atkinson, G. Sandstrom, S. Orbell, and L. Aknin. 2021. “Loosening the GRIP (Gender Roles Inhibiting Prosociality) to Promote Gender Equality.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 25 (1): 66–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868320964615

- Da Silva, E., and A. Las Casas. 2017. “Sport Fans as Consumers: An Approach to Sport Marketing.” British Journal of Marketing Studies 5 (4): 36–48.

- Delia, E. B. 2020. “The Psychological Meaning of Team among Fans of Women’s Sport.” Journal of Sport Management 34 (6): 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0404

- Denison, E. 2021. “Why is AFL the Only Pro Sport to Never Have an Openly Gay Male Player?” The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/why-is-I-the-only-pro-sport-to-never-have-an-openly-gay-male-player-20210625-p58477.html

- Dorken, S., and,A. Giles. 2011. “From Ribbon to Wrist Shot: An Autoenthnography of (A)Typical Feminine Sport Development.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 20 (1): 13–22. doi: 10.1123/wspaj.20.1.13.

- Eagly, A. 1987. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Psychology Press.

- Eagly, A., and W. Wood. 2012. “Social Role Theory.” In Handbook of Theories in Social Psychology, edited by P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, and T. Higgins, 458–476. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Fink, J. 2015. “Female Athletes, Women’s Sport, and the Sport Media Commercial Complex: Have we Really “Come a Long Way, Baby”?” Sport Management Review 18 (3): 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.05.001

- FitzGerald, C.,A. Martin,D. Berner, andS. Hurst. 2019. “Interventions Designed to Reduce Implicit Prejudices and Implicit Stereotypes in Real World Contexts: A Systematic Review.” BMC Psychology 7 (1): 29 doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0299-7.

- Fortington, L. V., and C. F. Finch. 2016. “Priorities for Injury Prevention in Women’s Australian Football: A Compilation of National Data from Different Sources.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2 (1): e000101. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000101

- Fox, A., J. Bonacci, S. Hoffmann, S. Nimphius, and N. Saunders. 2020. “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Australian Football: Should Women and Girls Be Playing? You’re Asking the Wrong Question.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 6 (1): e000778. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000778

- Funk, D. C, andJ. D. James. 2006. “Consumer Loyalty: The Meaning of Attachment in the Development of Sport Team Allegiance.” Journal of Sport Management 20 (2): 189–217. 10.1123/jsm.20.2.189.

- Funk, D. C., K. Alexandris, and H. McDonald. 2022. “Sport Consumer Attitudes.” In Sport Consumer Behaviour Marketing Strategies, edited by Daniel C. Funk, Kostas Alexandris, and Heath McDonald, 204–223. London, UK: Routledge.

- Funk, D. C., K. Filo, A. A. Beaton, and M. Pritchard. 2009. “Measuring the Motives of Sport Event Attendance: Bridging the Academic-Practitioner Divide to Understanding Behavior.” Sport Marketing Quarterly 18 (3): 126–138.

- Funk, D. C., and J. D. James. 2004. “The Fan Attitude Network (FAN) Model: Exploring Attitude Formation and Change among Sport Consumers.” Sport Management Review 7 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(04)70043-1

- Funk, D. C., L. L. Ridinger, and A. M. Moorman. 2003. “Understanding Consumer Support: Extending the Sport Interest Inventory (SII) to Examine Individual Differences among Women’s Professional Sport Consumers.” Sport Management Review 6 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1441-3523(03)70051-5

- Gentile, A., S. Boca, and I. Giammusso. 2018. “You Play like a Woman!’ Effects of Gender Stereotype Threat on Women’s Performance in Physical and Sport Activities: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 39: 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.07.013

- Gill, S. D., J. Stella, N. Lowry, K. Kloot, T. Reade, T. Baker, G. Hayden, M. Ryan, H. Seward, and R. S. Page. 2021. “Gender Differences in Female and Male Australian Football Injuries – A Prospective Observational Study of Emergency Department Presentations.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 24 (7): 670–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2021.02.011

- Glazbrook, M. R., and S. N. Webb. 2022. “AFLW and the Gender Gap: An Analysis of Public Attitudes towards the Women’s Australian Football League.” Australian Journal of Psychology. doi: 10.1080/00049530.2024.2315949.

- Gothreau, C., K. Arceneaux, and A. Friesen. 2022. “Hostile, Benevolent, Implicit: How Different Shades of Sexism Impact Gendered Policy Attitudes.” Frontiers in Political Science 4: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.817309

- Guest, A. M., and A. Luijten. 2018. “Fan Culture and Motivation in the Context of Successful Women’s Professional Team Sports: A Mixed-Methods Case Study of Portland Thorns Fandom.” Sport in Society 21 (7): 1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1346620

- Guerstein, G. 2017. “Sports Fans as Customers and Measurement of Their Attitudes.” Theoretical and Empirical Aspects of Economics, Management and Finance 5 (4): 219–230.

- Giuliano, P. 2018. “Gender: An Historical Perspective.” In Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, edited by S. L. Averett, L. M. Argys,and S. D. Hoffman. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gonzalez, A. M., J. R. Steele, E. F. Chan, S. A. Lim, and A. S. Baron. 2021. “Developmental Differences in the Malleability of Implicit Racial Bias following Exposure to Counterstereotypical Exemplars.” Developmental Psychology 57 (1): 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001128

- Gratten, M. 2011. “Survey Wake-Up for Footy Players.” The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/sport/afl/survey-wakeup-for-footy-players-20110404-1cynk.html.

- Hickson, J., and J. Marshan. 2023, July 18. “Land of the (Un)Fair Go? Peer Gender Norms and Gender Gaps in the Australian Labour Market.” SSRN Electronic Journal (TTPI – Working Paper 9/2023). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4520289

- Kanemasu, Y., and J. Johnson. 2019. “Exploring the Complexities of Community Attitudes towards Women’s Rugby: Multiplicity, Continuity and Change in Fiji’s Hegemonic Rugby Discourse.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 54 (1): 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217707332

- Kidd, B. 2013. “Sports and Masculinity.” Sport in Society 16 (4): 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.785757

- Kim, Y., M. Magnusen, M. Kim, and H. W. Lee. 2019. “Meta-Analytic Review of Sport Consumption: Factors Affecting Attendance to Sporting Events.” Sport Marketing Quarterly 28 (3): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.283.092019.01

- Klugman, M. .“The AFL sells an inclusive image of itself. But when it comes to race and gender, it still has a way to go.”, 2019The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-afl-sells-an-inclusive-image-of-itself-but-when-it-comes-to-race-and-gender-it-still-has-a-way-to-go-124351

- Korabik, K, McElwain, A, and Chappell, D. 2008. “Integrating Gender-Related Issues into Research on Work and Family.” In Handbook of Work-Family Integration: Research, Theory, and Best Practices, edited by K. Korabik, D.S. Lero, and D.L. Whitehead, 215-232. US: Academic Press.

- Kowalski, B.M., andC.P. Scheitle. 2020. “Sexual Identity and Attitudes about Gender Roles.” Sexuality & Culture 24 (3): 671–691. doi: 10.1007/s12119-019-09655-x.

- Kulik, L. 2018. “Explaining Egalitarianism in Gender-Role Attitudes: The Impact of Sex, Sexual Orientation, and Background Variables.” Asian Women 34 (2): 61–87. https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2018.06.34.2.61

- Lenkic, B., and R. Hess. 2016. Play on! The Hidden History of Women’s Australian Football. Echo Publishing.

- Levi, Hannah,Ross Wadey,Tanya Bunsell,Melissa Day,Kate Hays, andPete Lampard. 2022. “Women in a Man’s World: Coaching Women in Elite Sport.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 35 (4): 571–597. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2022.2051643.

- Lewin, R. 2023. “How an ‘Insane’ Record-Breaking Crowd Lived up to the Hype and Drove the Matildas to Victory.” 7News Sport. https://7news.com.au/sport/fifa-womens-world-cup/how-an-insane-record-breaking-crowd-lived-up-to-the-hype-and-drove-the-matildas-to-victory-c-11335819.

- Lobpries, J., G. Bennett, and N. Brison. 2018. “How I Perform is Not Enough: Exploring Branding Barriers Faced by Elite Female Athletes.” Sport Marketing Quarterly 27 (1): 5–17. doi: 10.32731/SMQ.271.032018.01

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E., and K. Chlebosz. 2019. “Sport Spectator Consumption and Sustainable Management of Sport Event Tourism; Fan Motivation in High Performance Sport and Non-Elite Sport. A Case Study of Horseback Riding and Running: A Comparative Analysis.” Sustainability 11 (7): 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072178

- McCabe, C. 2008. “Gender Effects on Spectators’ Attitudes toward WNBA Basketball.” Social Behavior and Personality 36 (3): 347–358. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.3.347

- McDonald, M. G. 2000. “The Marketing of the Women’s National Basketball Association and the Making of Postfeminism.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 35 (1): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269000035001003

- Melton, E. N., and J. D. MacCharles. 2021. “Examining Sport Marketing through a Rainbow Lens.” Sport Management Review 24 (3): 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1880742

- Messner, M. 2011. “Gender Ideologies, Youth Sports, and the Production of Soft Essentialism.” Sociology of Sport Journal 28 (2): 151–170. doi: 10.1123/ssj.28.2.151.

- Morgenroth, T., and M. K. Ryan. 2020. “The Effects of Gender Trouble: An Integrative Theoretical Framework of the Perpetuation and Disruption of the Gender/Sex Binary.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 16 (6): 1113–1142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620902442

- Morgan, Roy. . 2020. “TV Viewership of the AFL Women’s Competition Increases While Others Decline.” Roy Morgan Research. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/tv-viewership-of-the-afl-womens-competition-increases-while-others-decline.

- Mosalanezhad, M., M. Talebpour, Z. S. Mirzazadeh, and M. Keshtidar. 2020. “Investigating the Factors Affecting the Financial Viability of Professional Sports Leagues - A Study of Iranian Handball Premier League.” PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17 (12): 683–702.

- Mumcu, C., N. Lough, and J. C. Barnes. 2016. “Examination of Women’s Sports Fans’ Attitudes and Consumption Intentions.” Journal of Applied Sport Management 8 (4): 44–48. https://doi.org/10.18666/jasm-2016-v8-i4-7221

- Mumcu, C., and S. C. Marley. 2017. “Development of the Attitude Towards Women’s Sport Scale (ATWS).” International Journal of Sport Management 18 (2): 183–209.

- Neubaum, G., S. Sobieraj, J. Raasch, and J. Riese. 2020. “Digital Destigmatization: How Exposure to Networking Profiles Can Reduce Social Stereotypes.” Computers in Human Behavior 112: 106461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106461

- Nicholson, M., B. Stewart, G. de Moore, and R. Hess. 2021. Australia’s Game: The History of Australian Football. Melbourne, Australia: Hardie Grant Books.

- Pape, M. 2023. “An Unhappy Marriage? Sex Segregation and Inclusion Debates in Women’s Sport.” In Routledge Handbook of Sexuality, Gender, Health and Rights, edited by P, Aggleton., R, Cover., C. H. Logie., C. Newman., and R. Parker. New York, Routledge.

- Petty, K., and S. Pope. 2018. “A New Age for Media Coverage of Women’s Sport? An Analysis of English Media Coverage of the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup.” Sociology 53 (3): 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518797505

- Rahbari, L. 2019. “Pushing Gender to Its Limits: Iranian Women Bodybuilders on Instagram.” Journal of Gender Studies 28 (5): 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2019.1597582