Abstract

Reports of sexism in sport are ever-growing despite the potential for sexism to impact the well-being of everyone negatively. Relatively little research has investigated this phenomenon, meaning we do not have a clear picture of women’s experiences and are far from implementing relevant solutions. We explored women’s experiences of sexism while working in sport to gain an understanding of how multiple ecological layers intertwine to influence these experiences. A survey, based on the Everyday Sexism Survey, was completed by 105 women; qualitative data was abductively thematically analysed using LaVoi and Dutove ecological model to make sense of women’s experiences. Higher-order themes represented the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, and sociocultural levels at which participants experienced sexism. Clear evidence of sexism at all levels of the ecological model demonstrates that organisations and policymakers must consider the social and personal change necessary for women working in sport.

Introduction

Research demonstrates that women have occupied a lower social status than men in almost every historical context (e.g. Acker Citation1973). Goldman and Gervis (Citation2021) described sport as an inhospitable place for women due to the multiple forms of gender inequities present for athletes, support, and performance staff, and those in senior leadership positions. Moreover, it is well documented that sport research (and research more broadly) has been biased in favour of men in terms of both participant characteristics and gender of researcher (Cowley et al. Citation2021; Criado-Perez Citation2019). Although this has been beneficial in providing us with a detailed understanding of men’s sporting experiences, it has left us with limited knowledge of how gender inequity may impact women in sport. It is generally accepted that women’s gendered experiences in society more broadly are associated with impaired mental health (Barr et al. Citation2022), negative affect (Becker and Wright Citation2011), reduced cognitive function (Dardenne, Dumont, and Bollier Citation2007), and feelings of incompetence (Dumont, Sarlet, and Dardenne Citation2010). Nonetheless, we cannot assume that the above findings are transferrable to all settings because such assumptions do not allow for a nuanced understanding of the ways in which women working in sport experience and are impacted by sexism. In this study, we address the aforementioned disparities by undertaking the following research objectives:

Explore women’s experiences of sexism while working in a sporting context.

Gain an understanding of how multiple ecological layers intertwine to influence women’s experiences of sexism in sport.

Before critically discussing more recent literature on sexism in sport, we provide a short historical context of gender stereotypes and sexism; a contextual understanding of how heteronormative patriarchy impacts women, and society more broadly, is essential in providing a background to why this research is necessary as well as how the key findings are analysed and presented.

Many elements of gender stereotypes are learned in childhood and subsequently used to make lifelong inferences about others (e.g. men are stronger and more authoritative than women; Martin and Dinella Citation2002). Such stereotypes carry ‘cultural meanings, practices and expectations which serve to shape and influence people’s beliefs, feelings, attitudes and behaviours’ (Mastari, Spruyt, and Siongers Citation2019, 1). Men are often expected to display traits such as assertiveness, competitiveness, and ambition, whereas women are expected to be sensitive, nurturing, and caring (Saint-Michel Citation2018). ‘Masculine’ traits have been perceived as congruent with sporting culture, described by Champ et al. (Citation2018) as ruthless, volatile, and hierarchical. Therefore, we argue that the culture of sport not only allows for gender inequality to be hidden in plain sight (Fink Citation2016), but contributes to and maintains societal gender order (Anderson Citation2008).

Although we are speaking about sexism as a ‘universal experience based on gendered expectations,’ (Fink Citation2016, 2), there are other marginalised characteristics that intersect with gender (e.g. race, sexual orientation, social class, disability); any combination of these identities can multiply the impact of sexism and other societal challenges (Crenshaw Citation1989). In the present paper, we broadly delineate women’s experiences of sexism in sport.

Sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on sex or gender and is evident through behaviours, words, images, policies, laws, attitudes, and more. More specifically, sexism entails a complicated combination of animosity and perceived benevolence, also known as Ambivalent Sexism Theory (Glick and Fiske Citation1997). Hostile sexism aims to preserve men’s dominance over women through restricting women’s roles to conform to gender norms, and more generally involves antipathic attitudes towards women, particularly those who pose a threat to the gender hierarchy (Connor, Glick, and Fiske Citation2016; Mastari, Spruyt, and Siongers Citation2019). One common example of hostile sexism is using sexist language or insults, or challenging an individual when they step outside of traditional gender roles. Hostile sexism is overt and often acts as a precursor for sexual harassment, violence, and abuse towards women (Mastari, Spruyt, and Siongers Citation2019). In contrast, benevolent sexism is a subtle and socially accepted form of sexism often expressed in a manner that is perceived as positive (e.g. Ashburn-Nardo et al. Citation2014). Benevolent sexism ‘protects’ and demonstrates fondness toward women who embrace traditional gender roles despite their limitations, therefore reinforcing women’s inferior status within society (Connor, Glick, and Fiske Citation2016). Albeit positive in tone (e.g. women should be protected and cherished), benevolent sexism implies that women are inferior to men and assumes that their value and/or roles should be based on typical gender expectations.

Within the workplace, sexism has been shown to negatively impact employees’ performance, satisfaction, sense of belonging, and well-being (Hindman and Walker Citation2020). Additionally, women are often viewed as either incompetent but liked, or competent but disliked (e.g. Player et al. Citation2019). Subsequently, gender stereotypes influence women individually, socially, and professionally, resulting in men being disproportionately ranked at the top of professional hierarchies.

Sexism in sport

Historically, a primary function of the inception and development of organised sport was to maintain the white male heterosexual power structure (Anderson Citation2009). Sport is a powerful societal contributor (Kane and Maxwell Citation2011) and central to promoting and preserving patriarchal power structures (Bourdieu Citation2001). For example, throughout much of sporting history, sport has traditionally allowed men to demonstrate their ‘right’ to power through their ‘sporting prowess’ (Connell Citation1995, 4), despite the significant reason for men’s uncontested domination of sport being the formal exclusion of women and cultural exclusion of gay men (Bourdieu Citation2001).

Heteropatriarchal ideology is so deeply engrained in sport that it is ‘accepted’ as normal practice (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021), a notion that leaves us questioning how we can break the cycle to create a better future for women in sport. In 2016, ‘Women in Football’ distributed a survey to women working in the football industry in the UK. A total of 61.9% of respondents reported that they had been the recipient of sexist ‘banter’, and 14.8% had been sexually abused. More broadly, 40% of women working in leadership roles reported feeling less valued than their male counterparts due to gender, and 30% reported experiencing inappropriate behaviour from men (Women in Football Citation2016). Furthermore, Goldman and Gervis (Citation2021) explored 11 women sport psychologists’ experiences of sexism. Findings revealed that women who worked in mixed-gender Olympic sports felt their environment was more positive and accepting of them compared to male-dominated environments. Participants believed that sport culture, which has frequently been compared to a ‘boys’ club’, privileged masculinity and gave examples of experiencing benevolent and hostile sexism such as challenges with being taken seriously, lack of access to basic facilities (e.g. women’s restroom), and being treated with inappropriate familiarity. These findings were echoed in Lafferty et al. (Citation2022) narrative exploring women psychologists’ experiences in sport.

In recognising that sexism is experienced differently by individuals depending on a range of characteristics and identities, it is important that researchers take a wider view of individual and societal perceptions and influences. For example, LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012) adopted Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1977) ecological systems theory as one way to make sense of the multiple barriers facing female coaches across each level. Ecological models move beyond the individual to explore their intrapersonal (e.g. personal, biological, and psychological factors), interpersonal (e.g. socio-relational influences), organisational (e.g. organisational policies, job descriptions, professional practices, use of space, and opportunities, or lack thereof) and sociocultural (e.g. norms and cultural systems). Through using this model, researchers (e.g. LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012) recognise that women’s experiences working in sport are complex and affected by multiple levels of their environment, inclusive of their individual characteristics and immediate settings of family and colleagues, through to broader interactions with the sporting environment and societal culture and values. Ecological systems theory allows for the consideration of the interrelatedness between systems and how they intertwine to influence and shape women’s experiences.

Despite at least twenty years (e.g. Fink Citation2016; Roper, Fisher, and Wrisberg Citation2005) of stories detailing women’s experiences of sexism in sport, very little change has been made (e.g. Lafferty et al. Citation2022). Significant and valuable work has laid the foundation for conducting research on sexism in sport (e.g. Hindman and Walker Citation2020; Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012; Roper, Fisher, and Wrisberg Citation2005), and it is important to work towards gaining a broader understanding of sexism experienced by women working in sport. This is particularly the case as most studies have placed a narrow focus on the role of those delivering psychological support. As a next step, it is important to recognise that women occupy a plethora of roles in sport, spanning from coaching/managerial roles to sports science and medical support, and that role or status may influence women’s experience of gender equity. In this study, we address the aforementioned research objectives by exploring the ways in which women have experienced and been impacted by sexism whilst working in sport. In line with the suggestions of Cook and Fonow (Citation2018), we hope this paper allows us to understand the landscape of how sexism is experienced by women working in sport, meaning that future studies can focus on creating change.

Method

Research paradigm

The present research adopted a constructivist research paradigm in line with its focus on exploring the influence of society and culture on people’s understandings of their experiences, and assumptions that knowledge is socially, culturally, and historically constructed (e.g. Poucher et al. Citation2020). The authors assume ontological relativism in that we understand that reality is subjective and comprised of human action and interaction, and that no singular truth or reality exists, and epistemological subjectivism, in that knowledge is co-created between researcher and participant (e.g. Poucher et al. Citation2020). In line with this, the research team employed the primary principles of feminist research methodology: reflexivity surrounding how gender impacts all aspects of social life, consciousness-raising as a methodological tool, challenging claims of objectivity, feminist ethical considerations, and an emphasis on utilising research to transform patriarchal institutions and empower women (Cook and Fonow Citation2018). Culminated shared experiences can be a powerful mechanism for change (e.g. Lafferty et al. Citation2022); we aim to provide varying degrees of shared beliefs and experiences of these women using the ecological systems model (to be outlined below; Bronfenbrenner Citation1977; LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012) as a framework to present these experiences. All members of the research team identify as women and work within sporting environments and have experienced and observed sexist behaviour throughout their careers.

Participants

105 women ranging in age from 21 to 68 (Mage = 35.8; SD = 9.81) took part in the study. Participants were recruited through opportunity sampling (Jupp Citation2006) on social media. Women working in sport and 18 years or older were eligible to participate. Participant demographic data was collected including sexual orientation, ethnicity, and nationality (). Notably, while not an initial aim of this study, participants represented a highly Western, white majority, a factor which should be considered when interpreting the presented results and analysis. Participant career data was collected to identify participants’ role in sport (), seniority, and length of time working in sport.

Table 1. Participant demographic data.

Table 2. Participant primary career role.

Materials

This study was part of a wider project where the Everyday Sexism Survey’s (McDonald, Mayes, and Laundon Citation2016) questions were used and adapted to fit a sporting context. The use of this questionnaire was in line with our research aims and theoretical assumptions and allowed for a more holistic understanding of women’s experiences. McDonald, Mayes, and Laundon (Citation2016) survey was designed to measure sexism within organisations and addresses many different facets of hostile and benevolent sexism. The research team recognises the importance of context on experience and did not employ the survey for relational enquiry; therefore, the Everyday Sexism Survey provided an appropriate tool to explore our research aims in line with our philosophical positioning. Questions [available upon request] were adjusted to ensure suitability for women working in a sporting context. For example, the question ‘how can [organisation name] better prevent and respond to gender inequality or everyday sexism?’ was changed to ‘how can sexism be prevented in sport, and how might governing bodies in sport respond to gender inequality or sexism?’. Other qualitative questions included ‘Can you detail your experience(s) of sexism while training or working in sport?’ and ‘Is there anything else about sexism in your workplace or the culture of sport that you would like to tell us?’. Open-ended, free-text questions were included to allow participants to qualitatively share their experiences of sexism within their specific sporting workplace (Veal and Darcy Citation2014). The survey took 10-30 min to complete depending on participants’ depth of answers.

Procedure

Upon attaining institutional ethical approval (protocol number 21/SPS/032), participants filled out the online survey advertised through social media. The survey explained study aims, what participation would entail, and confidentiality. After completing the survey, all participants were offered information about accessible support services should they feel distressed.

Data analysis

Qualitative data captured within the survey collected by all 105 participants was abductively thematically analysed. The research team initially approached the data with no ‘guiding theories’, engaging in reflexive thematic analysis due to its flexibility and recognition of how the research team’s subjective knowledge, understanding, and experiences of sexism would inevitably shape the construction of themes and their subsequent analysis (an important principle of feminist research methodology; Braun and Clarke Citation2012, Citation2022; Cook and Fonow Citation2018). Throughout this process, qualitative survey answers were initially coded inductively by the first and second authors. This analysis enabled the researchers to generate a high number of codes within two overarching data topics (‘Experience’, 11 codes and ‘Importance of Eliminating Sexism’, six codes). For example, ‘Experience’ included ‘condescension’, ‘coping mechanisms’, and ‘genderising behaviours, roles, and emotions’. Codes for ‘Importance of Eliminating Sexism’ included ‘health’, ‘safety’, ‘career and personal development’, and ‘equality’. The high number of codes prompted the research team to recognise the need to refine analysis; this was achieved through a reflexive discussion between all research team members. Subsequently, the overarching topic of ‘importance of eliminating sexism’ was removed to allow a greater focus on experiences of sexism with the assumption that participants’ experiences would convey the importance of eliminating sexism in their own right.

At this point, the research team agreed that LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012) use of the ecological systems theory resonated with the initial codes; when discussing the next steps of analysis, the research team agreed to engage with a more deductive approach as we determined that the codes had a natural ‘fit’ with LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012) version of the ecological model. The first and second authors then used the inductively co-created codes to code the data deductively, drawing upon ecological systems theory. Initial inductive codes were placed into higher-order themes representing LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012) version of ecological systems theory. For example, the code ‘coping mechanisms’ was placed under the data topic of ‘intrapersonal’, and the code ‘condescension’ was placed under the data topic of ‘interpersonal’. These codes were further discussed and refined by the research team to create richer themes to present the data with shared meaning (Braun and Clarke Citation2012, Citation2022). These themes, while not representative of a single reality, present this sample’s representation of how their experiences have impacted their world. At all stages, the research team made a conscious decision to share their own understanding of the model, pre-existing ideas, beliefs, knowledge and attitudes to allow for a ‘critical interrogation’ of how such aspects influenced the research process and data.

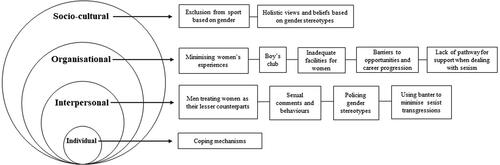

Application of the ecological systems model to women’s experiences of sexism working in sport

Developing from the instrumental work of LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012), this study adopted the ecological model to make sense of our participants’ experiences of sexism while working in sport; we adopted the modified version of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1977) ecological systems theory employed by LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012), initially developed by Sallis et al. (Citation2008). Women’s experiences, and their perceptions of these experiences, may be due to a plethora of variables resulting from an individual’s personal experience of the environment and culture they reside in. Ecological models prevent a one-dimensional view and acknowledge the interaction between the individual, their environment, and society. This model includes the following levels: firstly, the intrapersonal or individual level encompasses personal and psychological factors such as cognitions, emotions, values, beliefs, and in the context of this study towards perceptions of sexism. The following layer is the interpersonal level, which includes interpersonal interactions such as social relationships, and influences such as colleagues, significant others, friends, and family. The organisational level represents the organisational policies, professional practices, and opportunities (or lack thereof) presented within organisations (LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012). Finally, the fourth level is the socio-cultural level, which involves the socio-cultural norms that impact individuals, interpersonal relationships, organisational composition, and more. It is hoped that this model can help shed light on the existing gaps in the literature and sporting industry, and offer stakeholders and future researchers the opportunity to create social and personal change for women working in the sporting workplace.

Results and discussion

This section presents qualitative findings organised through an ecological systems theory lens of women’s experiences with sexism in the sports workplace (). The data presented involves a complex interrelationship between all levels of the model, although the authors have organised themes within the broader ecological model. While the results are presented in a way that makes sense to this research team, in line with our research paradigm, we are aware that readers will engage in naturalistic generalisability and that their own unique experiences will inform their interpretations of both the data and presented analysis.

Intrapersonal/individual experiences

This over-arching theme illustrates sexism experienced by the women in this study at an intrapersonal level such as cognition, biology, emotion, beliefs, and personal expertise. Importantly, a significant portion of participants reported experiencing sexist or crude remarks, jokes, gestures, or behaviours within their workplace; for example, Participant 22 (PE Teacher) details how she was singled out and ‘regularly asked questions like ‘have you had any cock recently?’ Obviously, they never asked each other questions like this’. We are aware that these experiences are stressful at an individual level (e.g. Fink Citation2016) and will lead to subsequent coping mechanisms dependant on the individual. In line with this, at an individual level, the women in this study most commonly discussed how they coped with sexist experiences; coping mechanisms was co-created as the only sub-theme at the intrapersonal/individual level.

Coping mechanisms

Coping mechanisms, the only co-created subtheme at the intrapersonal/individual level in this study, refers to how participants attempted to cope with their experiences of sexism. The data reflects varied responses to experiencing or witnessing sexism ranging from ‘ignore[ing] the remarks (but it does bother me)’ (Participant 18, National Development Officer) to leaving their profession altogether: ‘stopped coaching’ (Participant 62, Executive). Many participants felt unable to challenge or confront the perpetrator of sexism, and even when they did, their concerns were ignored:

I was refused work on the grounds I’m female (but the offer of work wasn’t ever

“concrete” enough, and/or the discrimination is not overt enough to make a formal complaint, just implied) - which seriously limits what you can do about the situation. Not many options available to you besides screaming into the void and commiserating with female friends and colleagues. (Participant 57, Coach Developer)

Several participants reflected similar stories, first engaging in problem-focused coping but adjusting to more avoidant or emotion-focused coping mechanisms either by necessity or choice. Another participant explained, ‘I have raised it. In the end when it wasn’t resolved- I left’ (Participant 14, Coach), while Participant 30 (Researcher) ‘just cried’. One participant explained that she copes by ‘dismissing’ sexism until it becomes unbearable:

I regularly experience sexism, I’d say on a daily basis. Sometimes I challenge it if it’s really bad but most of the time I shrug it off. In my previous job, the ‘harmless’ sexism escalated and lead to me having to put a sexual harassment complaint into my Head. The minor sexism I dismissed and laughed off built up until it became much bigger. Only then did I report it. It has made me challenge colleagues at my new school when they make sexist comments, but it is so commonplace that I pick my battles and only confront the things that I think are completely unacceptable. (Participant 22, PE Teacher)

It’s pretty much the norm for women working within male sport environments, and the worst part is you can feel like you need to let it slide, or go along with it, otherwise you aren’t seen to be ‘one of the lads’ and thus you’re not integrated within the sporting culture and your work can be rendered ineffective. (Participant 27, Trainee Sport and Exercise Psychologist)

Interpersonal sexism

This broader interpersonal theme comprises social-relational influences such as colleagues, friends, and parents. Based on participants’ responses, male colleagues and others normalising sexist behaviour are the primary focus of this theme, which is represented by subthemes detailing men treating women as their lesser counterparts, sexual comments and behaviours, policing gender stereotypes, and using banter to minimise sexist transgressions.

Men treating women as their lesser counterparts

This sub-theme represents men treating the women in this study as inferior based on gender assumptions (e.g. assuming women are lesser than their male colleagues in intelligence, strength, or importance). As a mechanism by which to demonstrate men’s dominance over women, condescension encompasses both benevolent and hostile sexism. Participant 19 describes her experience of having her skillset questioned as a result of her gender:

A male colleague was asked to work with a player instead as ‘the player would rather

speak to a man’ - no evidence of this being true. My quality of relationship with a player has been put down to me being a female and not my skill set. (Participant 19, Sport and Exercise Psychologist)

Due to the patriarchal assumption that gender has the potential to negate knowledge, the voices of men are often more valued than the voices of women (e.g. Beard Citation2017). This presumption often leads to not allowing women to thoroughly articulate their points, ‘brutally’ questioning women, ‘mansplaining’, and refusing to accept women’s expertise in ‘masculine’ environments (Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Whaley and Krane Citation2012, 69). This was frequently reported by the women in this study: ‘people (men) spoke over me while I have been making points in meetings, they have gone on to say the wrong thing but other men have agreed. Happens all the time. Undervalued despite holding high qualifications and knowledge’ (Participant 2, Researcher). This condescending behaviour can impact women’s performance, maintaining the idea that women do not belong in sport. Additionally, these efforts can escalate to increasingly hostile sexism. For example, one method by which women’s performance is often undermined is by threats to their physical and mental well-being and safety:

Male coaches would interject to take over a conversation with an athlete, even though I was coaching at a much higher level and have much more experience. One male coach followed me around when I was coaching, which I felt was intimidating, and he wouldn’t stop when I told him it was making me uncomfortable. (Participant 40, Coach)

Sexual comments and behaviours

This sub-theme refers to direct or indirect comments and behaviours towards women which are sexual in nature. For example, participant 39 (Coach) reports that she was ‘told she was employed because she looked good poolside’. In addition, participant 22 (PE Teacher) illustrates an all-too-familiar story (e.g. Lewis, Williams, and Jones Citation2020) of how sexism that is brushed off as harmless can escalate into intimidating, scary behaviour:

I experienced a lot of sexism as the only female PE teacher. My manager at the school started off with a few comments, then he started appearing where I was teaching, when I was on duty etc. Then texts started. At first I laughed things off as being a ‘joke’ but it eventually got really bad and lead to me reporting it. I left this too late as I felt intimidated, he was the most senior member of staff at the school other than the head who was away at the time. After reporting him another 4 members of staff reported him too. They just needed a voice and to know they’d be listened to. (Participant 22, PE Teacher)

While sexism and harassment towards women can have a negative impact on performance and is used as a mechanism by which to exclude women from sport, it must be emphasised that while performance is important, safety is a workplace right and should be prioritised above all else. No one should have to worry about being sexually harassed at their place of work; despite this, there are numerous accounts of sexual harassment (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Lafferty et al. Citation2022) and abuse (e.g. Lewis, Williams, and Jones Citation2020) towards women in sporting contexts, including this study, and it is likely that these stories capture only a small number of actual accounts. An exemplification of how the different levels of the ecological model are interrelated, this interpersonal experience will impact women at a very intrapersonal level: not only must women consider how they position themselves within an organisation and fight to have their knowledge accepted and perspectives heard, this is often accompanied by feeling unsafe and vulnerable, and very little is known about how these experiences impact long-term well-being.

Policing gender stereotypes

This sub-theme refers to the enforcement of behaviours based on assumptions made about peoples’ bodies, emotions, roles, and behaviours based on gender. Enforcing the performance of traditional gender roles through both benevolent and hostile sexism has historically been a major method of maintaining hegemonic masculinity. Sport often assumes normative femininity in women (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021) because any action or discourse that challenges traditional norms can be seen as a threat (Adams, Anderson, and McCormack Citation2010). For example, participant 42 (Manager) was told to ‘smile more in meetings,’ and Participant 39 (Coach) had been asked, ‘who was looking after family so they were available to attend training/gala over a weekend. Then being criticised for being away from home so much’. This was also expressed by Participant 34 (Coach), who noted ‘I get more comments about my role, that travelling should be harder for me than my husband because I’m a mother’.

Women are regularly only given value for roles that will not disrupt men’s traditional power structure (e.g. motherhood, traits such as being attractive or caring; Adams, Anderson, and McCormack Citation2010), and when women step outside of traditional norms, men often resort to more direct comments about their place in the world. This was reflected in the present study, with one participant (Prefer not to say) commenting, ‘a male colleague asked if I’d like to be taken shopping rather than attending our meeting – which was for the FA Council’. Additionally, participant 25 (Physiotherapist) was told ‘I was being replaced because I ‘might be a distraction to the players’ - that I potentially might be too aesthetically pleasing, and athletes may unnecessarily spend time in my company’.

Using banter to minimise sexist transgressions

Using banter as a method of engaging in sexism was commonplace in this study. Banter is a useful tool in the maintenance of the gender hierarchy, as it is often interpreted as ‘funny’ and ‘harmless’ by men; as with most benevolent sexism, women are disempowered from confronting the perpetrator of sexist banter because of the so-called ‘comical-tone’ of the comments (Ashburn-Nardo et al. Citation2014). Additionally, men often circumvent responsibility for engaging in hostile sexism by using banter, which is broadly accepted as a part of sporting culture (e.g. Nesti Citation2010), making it more difficult to challenge. In fact, literature detailing how to effectively work in professional football offers advice to psychologists on how to use banter to their advantage: ‘the opportunity to share in masculine camaraderie and join in the ubiquitous ‘banter’ that is so much a part of this culture will do much to mitigate the feminine stereotype’ (Nesti Citation2010, 17). Aside from the obvious issues (e.g. problematising femininity), this is especially problematic in a world where women constantly feel like they must remain alert for their personal safety (e.g. Lewis, Williams, and Jones Citation2020), particularly in male-dominated environments, and even banter that might seem harmless to some can be concerning for women: ‘I was finishing off a job interview and one of the panellists made an innuendo comment, much to the amusement of another male panellist. I laughed this off, but this made me feel uncomfortable’ (Participant 17, Sport and Exercise Psychologist).

The above experience emphasises the importance of environments where women feel safe enough to challenge sexist comments, and in the absence of that, the presence of male allies to question sexist banter. Despite this, male allies are scarce in many sporting environments (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021). Additionally, Participant 1 (Lecturer) explained how ‘sexist jokes being passed off as banter plays down the whole problem. Raising awareness is very difficult’. This is reiterated by Participant 45 (Coach), who notes that ‘most of the sexism I have experienced or witnessed has been brushed off as ‘banter’. Sometimes I feel the person saying it doesn’t even realise the consequences of their behaviour because it is accepted within society’.

Organisational sexism

Organisational sexism excludes women by making environments difficult to access, navigate, and work within; examples include policies, job descriptions, use of space, lack of access to basic facilities, unsuitable work clothing, and professional practice. Sport organisations are areas where men and their activities are generally privileged (e.g. designed and built for and by men; Shaw and Frisby Citation2006), and is another example of Fink’s conceptualisation of sexism as ‘overt’ but ‘unnoticed’ in sport (Fink Citation2016, 2). In this study, organisational sexism is characterised by minimising women’s experiences, boy’s club, inadequate facilities for women, barrier to opportunities and career progression, and a lack of pathway for support when dealing with sexism.

Minimising women’s experiences

This subtheme refers to minimising reports or experiences of sexism and harassment at an organisational level through excusing it as the norm, banter, or fictional. For example, Participant 84 (Physiologist) reported that they ‘have been ridiculed when rais[ing] that this behaviour is inappropriate’. Horrifyingly, Participant 67 (Client Manager) disclosed the dismissive behaviour from her boss when reporting her experience of hostile sexism and abuse, further compounding her experience: ‘I once made a complaint that a man had ‘drunkenly’ felt my breast at an event we were hosting and I was told by my boss that ‘I would be disappointed if this sort of thing didn’t happen to me’’. This dismissive behaviour was reiterated by Participant 48 (Operations Manager), who ‘had lots of stories from my female colleagues, things like men telling women sexism does not exist in sport and that she was making it up’. This minimisation is likely to inhibit women’s abilities to report sexism within their organisations, as evident in Participant 49’s quote:

Comments are made by men towards the women in the office it is laughed off as “that just X being X,” so it is a culture of accepting sexism as part of the job. When I have informed my manager of this happening the man involved was simply transferred to another training centre but is still a part of the sporting team. (Participant 49, Sport Scientist)

Boys’ club

This subtheme refers to informal groups of men within organisations that exclude women from the group itself as well as integrating into the organisation. Also known as the ‘Old Boys’ Club,’ this common phenomenon is frequently used to exclude those outside of heteronormative hegemonic masculinity (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021). Participant 22 explained this idea of ‘boys club’ and the stigma associated with being a woman:

The men have a ‘boys’ club’ together and regularly meet up during the workday for coffee, go to the gym, have a chat etc. If the women do this, then we get reprimanded and branded as lazy. Important work information is discussed amongst the males in the office and is rarely discussed with the females. (Participant 22, PE Teacher)

Further demonstrating the interrelatedness between ecological levels, another function of the boys’ club was reported to be exclusion through the minimisation of women’s experiences of sexism, an experience that has been reported consistently for nearly twenty years (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Roper Citation2008; Whaley and Krane Citation2012). The present results indicate little change: ‘the charming men rule and if they don’t like you then you cannot get in the door. If you are not already in the club then you cannot get in unless you are pals with the popular men’ (Participant 24, Consultant). As evident in this study and others (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021), ‘boys’ clubs’ often use methods found at various levels of the ecological model (e.g. banter) to minimise and exclude women, resulting in a small but dominant community of men that systematically maintain the gender hierarchy, particularly in sport, where these groups possess power within an organisation and often go unchallenged, even by other men.

Inadequate facilities for women

This sub-theme refers to how sport and its respective organisations have been built and organised primarily by men and for men’s needs (e.g. Shaw and Frisby Citation2006). This links to infrastructure, clothing, facilities, and more, and is another example of how women are both passively and actively excluded from sport organisations. Women are often unaccounted for when orders for uniforms or other organisation-specific clothing are made, resulting in awkward conversations or having to wear uncomfortable clothing:

When working in football, I am always given men’s kit to wear, despite the fact that there is women’s kit. The male team manager consistently orders male kit for me in the smallest sizes possible, but doesn’t consider than I might want to wear women’s clothes…This to me typifies football’s lack of interest, concern or attention to detail regarding female staff. (Participant 17, Sport and Exercise Psychologist)

Barriers to opportunities and career progression

This sub-theme refers to how being a woman is a disadvantage to opportunities that might progress women’s careers within sport. Nearly twenty years ahead of Roper, Fisher, and Wrisberg (Citation2005) article illustrating unfair hiring practices and barriers relating to family matters creating major obstacles for women sport psychologists, the idea of being ‘overlooked’ was prominent within the present data: ‘A colleague was overlooked for promotion. I heard the interviewing male manager say ‘She will just pop out another kid, I’m not promoting her to fund her baby making’’ (Participant 21, Coach). This abuse of women’s rights was also reported by Participant 74 (Coach): ‘I was stopped from doing my job during my first pregnancy. No maternity policy in place’. These experiences were echoed by many participants, including Participant 79 (Coach), who was ‘told women cannot make it to the top of the career ladder’ and was ‘not supported on maternity leave’.

Similar to the glass ceiling illustrated by Roper, Fisher, and Wrisberg (Citation2005), participants reported extreme difficulty in achieving promotions because they are women:

Having trustees work against me so I wouldn’t get an executive officer role. Being openly abused. Having lies told about me to try and kill my credibility. People scheming to ensure the girls and women’s section in the club fails. (Participant 54, Coach)

Lack of pathway for support when dealing with sexism

This sub-theme refers to participants’ inability to progress with complaints about sexism within an organisation and the perception that there is no support for individuals who experience sexism within their organisation. While we have discussed this experience as a cause or consequence for themes at intrapersonal (e.g. a reason for avoidant coping) and interpersonal (e.g. minimisation of women’s experiences, banter) levels, the lack of pathway for support was consistent throughout the data and warrants an organisational theme. For example, Participant 49 (Sport Scientist), ‘heard of derogatory comments made by a male member of staff towards both an athlete and staff members regarding physical attributes. No action was taken by the organisation when this was made known to them’. Further supporting why women rarely engage with problem-focused coping, women who feel safe enough to report their experiences are often met with condescension and a lack of understanding:

Myself and my colleague can often be referred to as ‘girls’ or ‘the girls’ by the rest of the staff team - which feels pretty patronising when you’re 28-30+ year old women, and it feels invalidating and not reflective of our age or stage. I raised it with our placement supervisors (both men) and they couldn’t understand why we were bothered, despite me pointing out they’ve likely never been referred to as ‘boys’ in their professional lives. Ironically, they also called us ‘girls’ multiple times within the meeting. (Prefer not to say)

Additionally, Participant 14 (Coach) reported how there was ‘support verbally (from a male superior) but inaction after conversation’. This lack of support from men is reiterated by Participant 24 (Consultant), who notes ‘there are not many male allies still. After over 20 years of trying to make change’. Commonly, even those who witness sexism and interpret it as inappropriate are unlikely to question or dispute the sexism, particularly if perpetrated by someone in power (e.g. a leadership role; Ashburn-Nardo et al. Citation2014). This means that women are often less likely to feel the social power to confront any man in their organisation; additionally, men are less likely to challenge those with more power in their organisation (e.g. coaches, management, the ‘boys’ club’, etc.), and are even more likely to engage in sexism if committed by a man in power (e.g. Ashburn-Nardo et al. Citation2014). This can lead to abhorrent behaviour and hostile sexism being perpetrated and accepted by men, and subsequent hostile sexism within an organisation, as evident in this study: ‘I was sexually harassed in the workplace by a head coach for six months. As a result, I received a high amount of sexism towards myself as people blamed me for this happening’ (Participant 82, Performance Director). As mentioned above and emphasising the interrelatedness between the different subthemes and ecological layers, the tendency to minimise women’s experiences can result in hostile sexism and abuse, which should be unacceptable in any organisation. The authors therefore contend that there is a major onus on sporting institutions and organisations, who have a duty of care to ensure their employees’ well-being and safety is supported; in addition, these institutions must to establish and maintain cultures where sexism is not only not tolerated, but actively challenged at a structural and personnel level. However, these institutions are unlikely to do so (Goldman and Gervis Citation2021) unless pushed to do so by policies at a governing body level.

Sociocultural sexism

This theme encompasses norms and cultural systems, such as stereotypes and more generalised marginalisation. More specifically, while we exist in a heteropatriarchal society, sport is a compounded version of this where men possess even more power and privilege due to the explicit construction of sport as a mechanism to maintain white, straight men’s power in society (e.g. Anderson Citation2009). In the context of this study, sociocultural sexism is illustrated through exclusion from sport based on gender and holistic views and beliefs based on gender stereotypes.

Exclusion from sport based on gender

Participants felt excluded from equal treatment and opportunities to work and/or lead in sport. This sub-theme illustrates Beard’s (Citation2017) assertion that ‘you cannot easily fit women into a structure that is coded as male’ (86), and reflects a widely-reported general non-acceptance of women (e.g. Beard Citation2017; Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Lafferty et al. Citation2022). Women were often overlooked within leadership, with Participant 24 (Consultant) explaining that she was ‘not seen as leadership material against the men who are the norm and perform less well when it comes to leadership behaviours. My way was different so assumed to be less valuable’. This relates again to women’s leadership styles (although often extremely effective) being viewed as less impactful (Player et al. Citation2019). One participant was extremely impacted by the feeling of being unwelcome in a sporting environment:

I generally work in women’s sport. It’s partly by choice, and partly because I felt so unwelcome in the male sporting environments I had been trying to work in, that I couldn’t really hack it anymore. I shouldn’t be limiting my career options because our employment field is looking the other way when it comes to patriarchal structures within sport and exercise enacting harm - sexism affects women AND men, we owe it to everyone working in the field to do more, and do better. (Prefer Not to Say)

Holistic views and beliefs based on gender stereotypes

This sub-theme details broader views and beliefs based on learned gender stereotypes imposed upon the women in this study. The data has highlighted that societal gender stereotypes are influencing people’s beliefs about men and women. Gender stereotypes are used on a cultural level to justify the gender hierarchy (e.g. Cejka and Eagly Citation1999), which is evidenced in the present study. These stereotypical beliefs are often perpetuated with ‘minor’ comments, resulting in constant generalisation, as reported by Participant 19 (Sport and Exercise Psychologist): ‘I’ve heard men describing other men as being ‘on their period’ when they’ve displayed anger/an emotional response to something happening’. These normalised statements accomplish maintaining hegemonic masculinity in numerous ways. First, these assumptions prevent men from engaging with healthy behaviours such as expressing their emotions. Second, they maintain the idea that something associated with femininity (e.g. a period) is a negative. Normalising feminine experiences directly threatens hegemonic masculinity, and therefore must be problematised within a patriarchal system, a tendency that is further illustrated by additional participants: ‘Women are seen as too emotional however the men were passionate’ (Participant 24, Consultant); ‘Described as over emotional when men show same traits’ (Participant 95, Coach); ‘a coach referred to his feminine side, joking he would go home and have a mental breakdown’ (Participant 31, TV).

Numerous women reported a necessity to maintain a more masculine aesthetic or leadership style within their organisations. For example, Participant 9 (Project Manager) reported that ‘the women who have a feminine style in sports workplaces are not taken serious[ly]’. The idea that ‘masculine’ traits are singularly desirable in sporting culture not only perpetuates the gender hierarchy, but also prevents both women and men from being authentic; this makes navigating and performing in leadership roles more challenging (Hopkins and O’Neil Citation2015) and can have negative impacts on well-being for men and women (Ménard and Brunet Citation2011). For example, Participant 14 (Coach) stated that she ‘heard the phrase ‘you hit like a girl’ used as a negative in coaching sessions’. Using femininity as a punishment, evident in additional research (e.g. Goldman and Gervis Citation2021), maintains the idea that femininity is antithetical to strength and therefore bad. Furthermore, the ‘ideal lady’ stereotype was emphasised by Participant 101 (below):

“I was asked in the UK (at a work event) how strange it was that I drink black coffee and beer, and I play a contact sports, they literally said ‘this is not what a lady does’. The fact that the UK education system segregates in school by gender, women play netball, men play rugby and football, is automatically telling the society that women should not play “men’s sports”. I am an engineer by degree, and if society does not put an effort in changing behaviour and people’s mindset, there will continue be a lack of women in engineering and science for example, because society tells the girls that “this is not what a lady does”. (Participant 101, Coach)

Summary

In this paper, we sought to explore how sexism is experienced by women working in sport. As the first study to consider sexism in the workplace more broadly (e.g. outside of specific role(s) in sport), our findings demonstrate that sexism is commonplace in sport settings. Moreover, participants provided examples of hostile and benevolent sexism, suggesting that despite claims that ‘sexism is over” (Paquette Citation2016), sexism is experienced at intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, and sociocultural levels in the sporting world (Connell Citation2009; LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012; Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Lafferty et al. Citation2022; Musto, Cooky, and Messner Citation2017). Building on the foundational work of LaVoi and Dutove (Citation2012), where coaches reported experiences of sexism, ecological systems theory provided a novel framework through which to make sense of participant’s experiences of sexism across the multiple levels. Qualitative findings elucidated that each level should not be treated as a distinct entity, rather that sexism (and its roots in sport) are complex and each layer is inextricably intertwined (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979).

One concerning finding was the challenges participants faced in trying to cope with and/or report their experiences of sexism. Participants often felt unable to raise the issue of sexist behaviour with someone in their organisation due to believing that there would be a negative impact on their reputation, negative consequences for their career, that it would not make a difference, or that it was not safe enough to do so, assumptions which are correct based on the organisational responses to sexism reported within this study. Subsequently, they attempted to manage this interpersonal and organisational stressor at an intrapersonal level with avoidant and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). Feelings of isolation and loneliness in dealing with sexism were representative of inadequate support/resources available within the sport macrosystems and supports the findings from a BBC Sport survey (Grey Citation2020). This study found that elite British sportswomen were fearful of speaking up about incidents of sexism in case it negatively impacted their selection for future events. The implications of this are concerning in terms of creating any substantive shift in inequity and attitudes towards women. A first step in remedying this issue may be to develop specific policies for reporting and penalising sexism at organisational and governing body level, as well as consequences for those who fail to provide adequate support. Further, introducing training and education to facilitate awareness at interpersonal and organisational levels can work towards systemic change influences individual attitudes, actions, and behaviours. Education about what sexism is and is not is imperative to challenging its existence: to be able to challenge sexism, people first need to be able to recognise it as something discriminatory (Ashburn-Nardo et al. Citation2014).

Importantly, while the onus of eliminating sexism has historically been placed on women (e.g. Carter Citation2020), this should not necessarily be the case. Relative to women confronting sexism, men who do so are perceived much more positively, and confrontations are taken as more legitimate (Drury and Kaiser Citation2014). While this is in itself is due to sexist beliefs, it is important for allies to use their voice when witnessing sexism. With this in mind, while our results provide a depth of insight into women’s experiences of sexism whilst working in sport, it is important that future research diversifies to attain the perceptions of men. For example, it is important to attain a more holistic understanding of what shapes men’s views, attitudes, behaviours and how they feel about reporting observations of sexism. Pressure for eliminating institutionalised, culture-wide sexism and gender inequality from leadership organisations will likely generate commitment (Cunningham Citation2008); in other words, pressure from governing bodies is imperative to create positive change, and the research team recommend that governing bodies, organisations, experts, and importantly, women co-create relevant policies to improve equity in sport. These discussions and subsequent policies should consider each level of the ecological model and how these levels interact to inform women’s experiences, especially their ability to work and progress within a sporting environment in a manner that is facilitative to their mental and physical health.

Finally, reflecting on previous work within sexism, coaches (LaVoi and Dutove Citation2012) and sport and exercise psychologists (Goldman and Gervis Citation2021; Lafferty et al. Citation2022) represented a large portion of participants; it is important to gain more nuanced understandings of how specific roles within sport (e.g. physiotherapist, organisational roles) interact with women’s experiences. Similarly, while utilising a broad lens to examine the scope at which sexism is occurring in sport is important, the researchers maintain that a more storied approach will provide nuance to women’s experiences of sexism, inclusive of additional marginalising characteristics.

Limitations and concluding thoughts

In line with our philosophical positioning and research paradigm, the research team understand that readers will make their own interpretations of the data we have presented (e.g. naturalistic generalisability; Smith Citation2018). We understand that the experiences reflected by our sample does not represent the experience of every woman or organisation, and acknowledge that due to its broad approach, the present study did not focus explicitly on the intersectional nature (e.g. Carter Citation2020) of patriarchal oppression; similarly, white, northern, and Western women comprise the majority of the present sample. While it was important to start somewhere, further research should diversify in addressing additional facets of marginalisation as well as take a more storied approach to understand women’s experiences in order to paint a broader picture and work towards eliminating white heteronormative feminism in our fight towards eliminating a heteronormative patriarchal society.

With this in mind, it is important to restate that sexism was present at all levels of the socio-ecological model and that interpersonal, organisational, and sociocultural experiences of sexism often lead to women engaging in coping mechanisms that are often associated with compromised well-being. The onus is on those with privilege in sporting contexts (men in particular), sport organisations and policymakers, and sport culture more broadly to make efficient, positive changes to eliminate sexism within sport. Additionally, this paper is the first to broadly explore women’s experiences of sexism in sport and has provided information on how much more work there is to be done in this area. For example, the authors emphasise important areas to explore further, such as: the implications of specific roles on women’s experiences of sexism, more nuanced explorations of the intersectional nature of women’s experiences of sexism (e.g. sexual orientation, ethnicity, disability, etc.), and research exploring how we create change to make sport more equitable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Acker, J. 1973. “Women and Social Stratification: A Case of Intellectual Sexism.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (4): 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1086/225411

- Adams, A., E. Anderson, and M. McCormack. 2010. “Establishing and Challenging Masculinity: The Influence of Gendered Discourses in Organized Sport.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 29 (3): 278–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X10368833

- Anderson, E. 2008. “‘I Used to Think Women Were Weak’: Orthodox Masculinity, Gender Segregation, and Sport.” Sociological Forum 23 (2): 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2008.00058.x

- Anderson, E. D. 2009. “The Maintenance of Masculinity Among the Stakeholders of Sport.” Sport Management Review 12 (1): 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2008.09.003

- Ashburn‐Nardo, L., J. C. Blanchar, J. Petersson, K. A. Morris, and S. A. Goodwin. 2014. “Do You Say Something When It’s Your Boss? The Role of Perpetrator Power in Prejudice Confrontation.” Journal of Social Issues 70 (4): 615–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12082

- Barr, M., R. Anderson, S. Morris, and K. Johnston-Ataata. 2022. Towards a gendered understanding of women’s experiences of mental health and the mental health system. Women’s Health Victoria. Melbourne. (Women’s Health Issues Paper; 17).

- Beard, M. 2017. Women & Power: A Manifesto. London: Profile Books.

- Becker, J. C., and S. C. Wright. 2011. “Yet Another Dark Side of Chivalry: Benevolent Sexism Undermines and Hostile Sexism Motivates Collective Action for Social Change.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101 (1): 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022615

- Bourdieu, P. 2001. Masculine Domination. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. Thematic Analysis. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology 9 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Carter, L. 2020. Feminist Applied Sport Psychology: From Theory to Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Cejka, M. A., and A. H. Eagly. 1999. “Gender-Stereotypic Images of Occupations Correspond to the Sex Segregation of Employment.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25 (4): 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025004002

- Champ, F. M., M. S. Nesti, N. J. Ronkainen, D. A. Tod, and M. A. Littlewood. 2018. “An Exploration of the Experiences of Elite Youth Footballers: The Impact of Organizational Culture.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 32 (2): 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1514429

- Champ, F., N. Ronkainen, D. Tod, A. Eubank, and M. Littlewood. 2021. “A Tale of Three Seasons: A Cultural Sport Psychology and Gender Performativity Approach to Practitioner Identity and Development in Professional Football.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (5): 847–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1833967

- Connell, R. 2009. Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Connell, R. W. 1995. “Politics of Changing Men.” Radical Society 25 (1): 135. https://www.proquest.com/openview/eb5ad73acbe66dcd01c0ffe4ff500286/.

- Connor, R. A., P. Glick, and S. T. Fiske. 2016. “Ambivalent Sexism in the Twenty-First Century.” In The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice, edited by C. G. Sibley and F. K. Barlow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cook, J. A., and M. M. Fonow. 2018. “Knowledge and Women’s Interests: Issues of Epistemology in Feminist Sociological Research.” In Feminist Research Methods: Exemplary Readings in the Social Sciences, edited by J. M. C. Nielsen. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Cowley, E. S., A. A. Olenick, K. L. McNulty, and E. Z. Ross. 2021. “Invisible Sportswomen”: The Sex Data Gap in Sport and Exercise Science Research.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 29 (2): 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2021-0028

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (139): 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf.

- Criado-Perez, C. 2019. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Cunningham, G. B. 2008. “Creating and Sustaining Gender Diversity in Sport Organizations.” Sex Roles 58 (1–2): 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9312-3

- Dardenne, B., M. Dumont, and T. Bollier. 2007. “Insidious Dangers of Benevolent Sexism: Consequences for Women’s Performance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93 (5): 764–779. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.764

- Drury, B. J., and C. R. Kaiser. 2014. “Allies Against Sexism: The Role of Men in Confronting Sexism.” Journal of Social Issues 70 (4): 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12083

- Dumont, M., M. Sarlet, and B. Dardenne. 2010. “Be Too Kind to a Woman, She’ll Feel Incompetent: Benevolent Sexism Shifts Self-Construal and Autobiographical Memories toward Incompetence.” Sex Roles 62 (7–8): 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9582-4

- Eubank, M., M. Nesti, and A. Cruickshank. 2014. “Understanding High Performance Sport Environments: Impact for the Professional Training and Supervision of Sport Psychologists.” Sport & Exercise Psychology Review 10 (2): 30–36. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2014.10.2.30

- Fink, J. S. 2016. “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Embedded Nature of Sexism in Sport.” Journal of Sport Management 30 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0278

- Glick, P., and S. T. Fiske. 1997. “Hostile and Benevolent Sexism: Measuring Ambivalent Sexist Attitudes Toward Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21 (1): 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x

- Goldman, A., and M. Gervis. 2021. “Women Are Cancer, You Shouldn’t Be Working in Sport”: Sport Psychologists’ Lived Experiences of Sexism in Sport.” The Sport Psychologist 35 (2): 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2020-0029

- Grey, B. 2020. “Sportswomen Share Experiences of Sexism.” BBC Sport, August 14. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/53593465

- Hindman, L. C., and N. A. Walker. 2020. “Sexism in Professional Sports: How Women Managers Experience and Survive Sport Organizational Culture.” Journal of Sport Management 34 (1): 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0331

- Hopkins, Margaret M., and Deborah A. O’Neil. 2015. “Authentic Leadership: Application to Women Leaders.” Frontiers in Psychology 6: 959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00959

- Jupp, V. 2006. The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020116

- Kane, M. J. 2011. “Sex Sells Sex, Not Women’s Sports. So What Does Sell Women’s Sports?”, July 27. http://www.thenation.com.

- Kane, M. J., and H. D. Maxwell. 2011. “Expanding the Boundaries of Sport Media Research: Using Critical Theory to Explore Consumer Responses to Representations of Women’s Sports.” Journal of Sport Management 25 (3): 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.3.202

- Lafferty, M. E., M. Coyle, H. R. Prince, and A. Szabadics. 2022. “‘It’s Not Just a Man’s World’–Helping Female Sport Psychologists to Thrive Not Just Survive. Lessons for Supervisors, Trainees, Practitioners and Mentors.” Sport & Exercise Psychology Review 17 (2): 6–18. http://hdl.handle.net/10034/627002. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2022.17.2.6

- LaVoi, N. M., and J. K. Dutove. 2012. “Barriers and Supports for Female Coaches: An Ecological Model.” Sports Coaching Review 1 (1): 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2012.695891

- Lazarus, R. S., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Lewis, D., L. Williams, and R. Jones. 2020. “A Radical Revision of the Public Health Response to Environmental Crisis in a Warming World: Contributions of Indigenous Knowledges and Indigenous Feminist Perspectives.” Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique 111 (6): 897–900. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00388-1

- Martin, C. L., and L. M. Dinella. 2002. “Children’s Gender Cognitions, the Social Environment, and Sex Differences in Cognitive Domains.” In Biology, Society, and Behavior: The Development of Sex Differences in Cognition, edited by A. McGillicuddy-De Lisi and R. De Lisi, 207–239. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing.

- Mastari, L., B. Spruyt, and J. Siongers. 2019. “Benevolent and Hostile Sexism in Social Spheres: The Impact of Parents, School and Romance on Belgian Adolescents’ Sexist Attitudes.” Frontiers in Sociology 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00047

- McDonald, P., R. Mayes, and M. Laundon. 2016. Everyday Sexism Survey: Report to Victoria’s Male Champions of Change (MCC) Group. Austrailia.

- Ménard, J., and L. Brunet. 2011. “Authenticity and Well‐Being in the Workplace: A Mediation Model.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 26 (4): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111124854

- Musto, M., C. Cooky, and M. A. Messner. 2017. “‘From Fizzle to Sizzle!’ Televised Sports News and the Production of Gender-Bland Sexism.” Gender & Society 31 (5): 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217726056

- Nesti, M. 2010. Psychology in Football: Working with Elite and Professional Players. London: Routledge.

- Paquette, D. 2016. “Sexism Is Over, According to Most Men.” Washington Post, August 22. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/08/22/sexism-is-over-according-to-most-men/.

- Pierli, G., F. Murmura, and F. Palazzi. 2022. “Women and Leadership: How Do Women Leaders Contribute to Companies’ Sustainable Choices?” Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.930116

- Player, A., G. Randsley de Moura, A. C. Leite, D. Abrams, and F. Tresh. 2019. “Overlooked Leadership Potential: The Preference for Leadership Potential in Job Candidates Who Are Men vs. women.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00755

- Poucher, Z. A., K. A. Tamminen, J. G. Caron, and S. N. Sweet. 2020. “Thinking through and Designing Qualitative Research Studies: A Focused Mapping Review of 30 Years of Qualitative Research in Sport Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 13 (1): 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1656276

- Roper, E. A. 2008. “Women’s Career Experiences in Applied Sport Psychology.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 20 (4): 408–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200802241840

- Roper, E. A., L. A. Fisher, and C. A. Wrisberg. 2005. “Professional Women’s Career Experiences in Sport Psychology: A Feminist Standpoint Approach.” The Sport Psychologist 19 (1): 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.1.32

- Sallis, J. F., N. Owen, and E. B. Fisher. 2008. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by, K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath (4th ed., pp. 465–486). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Saint-Michel, S. E. 2018. “Leader Gender Stereotypes and Transformational Leadership: Does Leader Sex Make the Difference?” M@n@gement 21 (3): 944–966. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.213.0944

- Shaw, S., and W. Frisby. 2006. “Can Gender Equity Be More Equitable?: Promoting an Alternative Frame for Sport Management Research, Education, and Practice.” Journal of Sport Management 20 (4): 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.4.483

- Smith, B. 2018. “Generalizability in Qualitative Research: Misunderstandings, Opportunities and Recommendations for the Sport and Exercise Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

- Veal, A. J., and S. Darcy. 2014. Research Methods in Sport Studies and Sport Management: A Practical Guide. London: Routledge.

- Whaley, D. E., and V. Krane. 2012. “Resilient Excellence: Challenges Faced by Trailblazing Women in US Sport Psychology.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 83 (1): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2012.10599826

- Women in Football. 2016. “Women in Football 2016 Survey Analysis.” https://www.womeninfootball.co.uk/resources/women-in-football-2016-survey-analysis.html

- Women in Sport. 2020. “Impact Report 2018 and 2019.” https://womeninsport.org/research-and-advice/our-publications/impact-report-2018-and-2019/