Abstract

This paper makes three important contributions: to research on media and gender equality, specifically through the lens of gender equal sports coverage; to understanding the lived experiences of women in public service sports broadcasting, and to gender-sensitive public discourse and policy debates concerning the relationship between media and sport. In it, we examine industry attempts to achieve gender equal coverage in public service broadcasting (PSB) in Ireland and Sweden. The paper draws on a three-way dialogic exchange between the authors who, together, have sizeable professional and personal experiences of public service sports broadcasting, sports participation (from amateur to elite levels), and of voluntary sports coaching and administration. This novel exchange also responds to calls for greater insights into women’s engagements with media. The paper concludes by considering current issues for PSBs in relation to gender equal coverage and suggesting potential future lines of enquiry.

Introduction

This article is an important first step in redressing the empirical lacuna surrounding the voices of women in public service broadcasting (PSB). In so doing, it analyses the challenges for public broadcast media in designing a work model that can achieve gender equal coverage of sport. The case studies – SVT (Sveriges Television, Sweden) and RTÉ (Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Republic of Ireland, hereafter Ireland) – generate comparative insights on organisational culture and the lived experiences of women in PSB who have had to deal with their own and others’ interpretations of gender equality. The article reflects too upon the knotty interdependence of public service media, sport, and societal attitudes to gender equality as well as on the tensions inherent in gender equality between sameness and difference.

The research hiatus concerning the voices and experiences of women working within, or leading, PSB is notable, especially in democratic pluralist societies where debates are ongoing about each component of the idiom ‘public’, ‘service’ and ‘broadcasting’ (see, for example, Born Citation2005; Hendy Citation2013). The value of a strong public dimension to media in liberal democracies is widely acknowledged; globally (e.g. Goodman Citation2011; Vipond Citation1992; Inglis Citation2002), and in Europe (e.g. Arriaza Ibarra, Nowak, and Kuhn Citation2015), including Sweden and Ireland. Both countries are geographically peripheral EU members, characterized by relatively small populations with distinctive language communities and internationalized economies. Welfare regimes differ in both countries and that impact on women’s labour market participation. Sweden is widely regarded as having more progressive family policies that promote gender equality (Nygren et al. Citation2021). The rate of mothers’ employment is much higher there for those who have children of school going age (Boje and Ejrnæs Citation2012) than in Ireland.

Notwithstanding such differences, public and private radio and television in Western Europe are more similar than they are different because of EU regulation and a shared commercial logic (Hultén Citation2007). PSBs have a particular role to play in achieving gender equality in the EU given their historical evolution as social and cultural institutions. As Scannell and Cardiff (Citation1991, xi) put this: ‘broadcasting is not simply a content … Each and every programme is shaped by considerations of the audience, is designed to be heard or seen by absent listeners or viewers’. Put simply, PSBs make assumptions about the scope and purpose of their broadcasting and about their audiences. These assumptions are played out in a multi-media, digitized environment in which PSBs have to balance a more traditional supply-oriented philosophy with a demand-oriented approach to audiences as partners rather than targets (Ferrell Lowe and Bardoel Citation2007). European public service mission statements include a commitment to independence, quality news and information, objectivity, and equitable provision of service regardless of location or socio-economic status. Not only do PSBs entertain audiences and reflect social issues through ‘customer-led’ content, but they also ‘lead customers’ by informing them about social and political change (Prahalad Citation1993).

Embodying national, political, and symbolic significance, SVT and RTÉ are both important actors for domestic quality content production and key patrons of diversity and pluralism. Both operate in an increasingly deregulated, international, digital environment, in which television sports rights have become a ‘battering ram’ (Murdoch 1996, cited in Milliken Citation1996) to penetrate national broadcasting systems (O’Boyle and Free Citation2020; Horgan and Flynn Citation2017; Flynn Citation2020). Consequently, the production of sports media content in both countries is an appropriate lens through which to understand the nexus of historical, cultural, and social processes related to gender equal coverage given to women’s sports. Notably, the work of both PSBs also featured in the European Broadcasting Union’s (EBU Citation2021) report on gender-balanced media coverage.

In addressing the lacunas around the experiences of women in PSB, and the challenges of achieving gender equal coverage in sport, this paper draws on the authors’ professional roles in, and experiences of, the media-gender-sport nexus amassed over many years. The format builds on a reflective three-way dialogic exchange, whose purpose was to build bridges between industry and research by asking questions with high potential real-world and academic value, and by listening and sharing points of view. This was designed to generate a more theoretically infused and evidence-informed approach to gender equal coverage. That the two PSBs, and countries, are at different stages on this journey was equally fruitful, from a comparative perspective. Media professionals, Hellstrand and O’Leary, were particularly focused on addressing practical problems around gender equal coverage in sport, which were pressing for them in industry and, as we shall demonstrate, require(d) daily and weekly action. The development of conceptual knowledge (brought by academic, Liston) leads to relatively slower progress in research terms. Still, the dialogic exchange permitted all three authors to achieve varying degrees of distance from these concerns. In so doing, it led to the activation of local knowledge and the generation of new questions and insights. These reflections should also be seen as one step in rolling engagement between the worlds of research and practice.Footnote1 We turn first to the contexts and work of RTÉ and SVT on gender-balanced sports coverage.

RTÉ and SVT

Historically, RTÉ and SVT operated as monopolies. Today, however, they compete within a mixed landscape of public service, commercial and independent broadcasting companies, which is typical of the European broadcast industry. Ideological justifications for the ongoing protection of public service media are similar in Ireland and Sweden. In Ireland, the licence fee has enabled RTÉ to compete within the international market but, in reality, it relies on mixed revenue (Murphy Citation2007) generated from a dual funding mandate (as public state broadcaster and semi-commercial operator reliant on advertising revenue and sponsorship). The entry of other broadcasters into the national Irish market in the mid-1990s – TG4, a free-to-air Irish language station, and TV3, now Virgin Media, a commercially run national broadcaster – has had a slow impact on indigenous production, such that independent producers continue to operate closely with RTÉ. Both RTÉ and TG4 are members of the EBU.

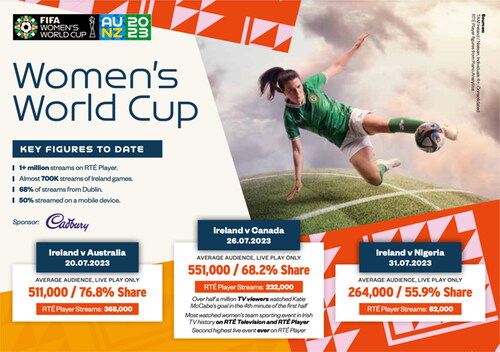

Like many other television services, RTÉ achieves its highest viewing figures annually from sport. Sports programming is a core element of its content which reflects the dominance of the ‘Big Three’ team sports in Ireland: Gaelic games, rugby union and football/soccer. Following 50 years of formal codification, the Republic of Ireland’s women’s football team competed in their first World Cup in 2023. The team’s opening World Cup match against the hosts, Australia, was the biggest live streamed event of the year for RTÉ (see ) while their second match, against Canada, was the most watched women’s team sport event in Irish TV history. An average of 551,000 viewers for this match equated to a 68.9 per cent audience share, and 234,883 live streams on RTÉ Player. This demonstrated a concomitant shift in the approach of RTÉ Sport towards women’s sports broadcasting following the 20 × 20 campaign. Involving national governing bodies of sports, local sports partnerships, media partners and sponsors, 20 × 20 set out to achieve a 20 per cent increase in media coverage of women in sport, female participation at all levels of sport and in attendance at women’s games and sports events between October 2018 and 2020 (Liston and O’Connor Citation2020).

RTÉ does not have the discretion, which it once had, to decide schedules and content based on what it considers to constitute public service broadcasting. External commissioning, television rights and all such decisions are now linked closely to market outputs and ratings. For instance, (Cliona O’Leary, pers. comm., January 6, 2024) observed that it was difficult to secure a slot for coverage of international Irish athletes within RTÉ 2 Sport if a large audience base was not guaranteed. Furthermore, future budget allocations for sports rights and production costs are based on previous outputs, ratings and coverage which means that, in practice, coverage can default to those sports with an already established audience (Cliona O’Leary, pers. comm., January 6, 2024). The biggest change to this practice within PSB sports rights in Ireland was the move in 2019 to cover the Women’s World Cup for the first time. In this, RTÉ partnered with TG4 to cover every game. This move was influenced by RTÉ’s partnership with 20 × 20 and, importantly, audience figures confirmed an interest for securing these rights even without an Irish team confirmed (Cliona O’Leary, pers. comm., January 6, 2024). Set in this context, RTÉ’s audience share for the 2023 Women’s World Cup () represents a break with the past, both in terms of the historical lack of investment in women’s soccer in Ireland but also as a baseline against which to judge future developments; specifically, whether transformational institutional change around gender equality and visibility is yet ongoing at RTÉ Sport following the 20 × 20 campaign (see 20x20 Citation2020), and whether RTÉ can sustain a longer-term commitment to gender equal broadcasting and gender equal coverage.

SVT and Sveriges Radio were originally a joint company formed in 1956 that separated in 1979. Together they are one of the longest established PSBs in the world. Funded today by a public service tax on personal income set by the national Swedish parliament, SVT launched its own language satellite channel in 1987 (TV3) and maintained a monopoly in terrestrial broadcasting until the early 1990s. Despite deregulation and commercialisation of the Swedish media landscape, it remains the largest Swedish television network with roughly one third of the audience share. In a recent Trust Barometer, sports coverage was an area where Swedes said they trusted media the most, but wider programming in SVT and Sveriges Radio also polarized right-wing audiences (Media Academy Citation2020; Nord and Van Krogh Citation2021). With the exception of sponsors of sporting events, SVT is barred from accepting advertisements.

Concerns were raised at the EBU about path dependency preferences following the impact of COVID-19 on sports broadcasting (see also Túñez-López, Vaz-Álvarez, and Fieiras-Ceide Citation2020). However, SVT had already moved away from the bundling of men’s and women’s sports in 2015, when it pledged to achieve gender equal sports coverage. This also reflected the fact that Sweden has actively promoted gender equality for much longer than Ireland (Hobson Citation2003; White and McArdle Citation2022; Plantenga et al. Citation2009). This commitment is reflected in its consistent ranking in the top five in the Global Gender Gap index. Still, egalitarianism and inequality coexist in Nordic countries (Tienari et al. Citation2009).

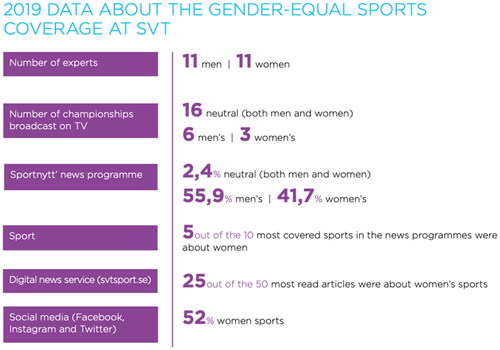

Broadcasting in Sweden has developed as part of this national culture. Considerable efforts have been made there to achieve gender equality, including the position of women in the newsroom and a reduction in gender typing over time. Women media professionals are visible in Swedish public broadcasting and the popular press (Djerf-Pierre and Ekström Citation2013). The licence-fee-financed television companies took a pioneering role in gender equality and gender balance was almost reached in Swedish news desks by the millennium. However, news production and programmes there were still characterized by gender bias until the early 2000s (Ekström and Djerf-Pierre Citation2013), particularly in relation to ‘soft’ social issues which were perceived as women’s territory. In contrast, political news was managed by men (Löfgren Nilsson Citation2013). In 2015, SVT began working actively on gender equal sports coverage, led by Åsa Edlund JönssonFootnote2 and SVT Sport was named the world’s best sports television channel in 2018. illustrates 2019 data on their achievements in this area, which culminated in the 2020 Swedish Equality Award for SVT.

In 2015, approximately 25 per cent of SVT’s news coverage was about women’s sports and this figure had doubled by 2022. Coverage was also extended to include live broadcasting of sports for the first time, such as Damallsvenskan, the top women’s football league. The rights to this league were subsequently acquired by a commercial outlet some years later (Jönsson, cited in Public Media Alliance Citation2022).

In both the Swedish and Irish cases, women working in these two PSBs had to negotiate traditional gender orders that favoured men over women, not only as decision-makers, but also as the traditional beneficiary group when it came to actual coverage. What then of the particular challenges of achieving gender equal coverage? Next is a synthesis of the experiences of this process based on a three-way dialogic exchange between the authors. The findings centre on the challenges for each PSB in designing and maintaining a work model for gender balance in sports news and coverage.

Hellstrand is currently Digital Strategist and Project Manager in the sport division at SVT where she has worked since the early 2000s. She is a member of the EBU’s Women in Sport Expert Group and a trainer in the EBU’s Masterclass in gender balance in sports media. She is also an active participant in indoor and outdoor sports and physical activities, and she is a track and field coach. O’Leary is currently Director of Corporate Affairs, Communications and Marketing at Sport Ireland, and former Deputy Head of TV Sport at RTÉ, where she worked for almost 25 years. O’Leary led RTÉ’s response and contribution to the 20 × 20 campaign and she was Chair of the EBU’s Women in Sport Expert Group at the same time. She is an active youth sports coach and Deputy Chairperson of her local Gaelic football club where she formerly led activities in the area of diversity and inclusion. Liston is a former elite sportsperson, regular contributor to media on sports-related issues and one of the co-authors of the first Irish report on women in sport, which was produced by the government’s Joint Oireachtas Committee. Amongst other things, this report recommended longitudinal research on the depth, breadth, types and content of media coverage of women’s sports, but was not acted upon (Joint Committee on Arts, Sport, Tourism, Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs Citation2005).

Gender equal coverage: an uneven and ongoing journey

Today, most Western European countries generate more coverage about women in sport than in the past and greater value is placed on female athletes there than in Eastern Europe (EBU Citation2021; Antunovic and Bartoluci Citation2023; Crolley and Teso Citation2007). But there are variations too. The EBU expert group on women in sport positions Scandinavia as a benchmark for all those involved and the interconnectedness of the media-sport-society landscape has shaped the popularity of sports for women and girls in Sweden (e.g. Larsson Citation2021; Ottesen et al. Citation2010). Still, work continues towards gender equal coverage in SVT and this journey has neither been smooth nor unilinear to date (e.g. Laine Citation2016; Wanneberg Citation2011). Hellstrand identified public male allyship (Smith Citation2023) as an important step in SVT’s formal commitment to gender equal coverage. This was when a male Head of News, Björn Fagerlind, also a well-known alpine sports commentator, publicly legitimized the place of gender equality in organisational success. In articulating the need for the PSB to take responsibility for improvements in women’s sports coverage, he rendered male privilege visible to the dominant gender group whose interests were served and buttressed by it.

The formal scrutiny of coverage given to women’s sports at SVT was rather ad hoc at first. This involved a baseline measure taken on a selected week across particular platforms, that involved manually counting teletext pages, online articles on the webpage and the number of stories in SVT’s sport news programmes. This measure was followed by another on a randomly selected week a number of months later. Gradually a more structured approach was introduced until formal targets were adopted by the sports division: that 25 per cent of all coverage should be devoted to women’s sports. Even then, many debates occurred about this target – for instance, why not 50 per cent given that women comprise roughly half the Swedish population? Gender equal coverage (50: 50) became the long-term vision, targets were adopted across various media platforms and regular monitoring was initiated. In 2015 SVT began to monitor their web content and social media, and a formal measurement system for broadcast was adopted in 2018. By these means, the PSB went from an arguably gender-blind approach to coverage, that included the nomination of a ‘Sports Lady of the Day’ at morning meetings of the sports team, to a more formal approach that involved target setting, monitoring, and regular self-reflection by all those charged with responsibility for meeting the long-term vision of gender-equal coverage.

One of the challenges for sustaining this systemic commitment to gender equal coverage was a change in leadership. When Jönsson left the sports division, months passed before a new Head of Division was appointed. As Hellstrand put this: ‘We didn’t have a boss and Åsa was really the one who had her heart in this, along with myself, so it was hard to keep the numbers up at first’. It was also more difficult to maintain the same level of coverage in the post-COVID era. In response, SVT created a smaller informal working group to counteract the leadership gap and maintain momentum. This allowed the sports division to re-establish a formal agenda item on gender equality. Today, SVT’s daily monitoring system involves an email to all staff with an extract from a data dashboard on gender equal coverage across multiple platforms. In 2024, SVT aim to refine this further and establish a real-time facility that will replace the manual counting (by gender) of web page articles on the previous day and in daily social media pieces followed by entry onto Microsoft Excel sheets.

Where these data were first necessary to start the conversation around gender equal coverage, now they are a routine item at daily meetings. Hellstrand and SVT encountered criticism from Swedish viewers concerning their increased coverage of sports such as women’s ice hockey or when opening sport news with items on women’s sports. But, by adopting a formal organizational strategy, SVT were successful in normalizing a new sense of ritual, routine, and repetition around this coverage. SVT had to be creative too when it came to setting up television production, in some cases collaborating with Yleisradio Oy (YLE), the Finnish broadcasting company, so that both PSBs could air and show images.

Annually, the sports division at SVT now reviews a dashboard of amalgamated data. By week 48 of 2023, SVT had exceeded their targets for coverage of women’s sports in broadcast news (44% versus 42.4%), on social media (51.3% versus 50%) and the broadcaster had achieved its target of 42.5% for the percentage of women’s sports tagged in online articles. And, in coverage of the most popular Swedish domestic team sports, targets for gender equal coverage were exceeded in football, handball and floorball with some additional work to be done in relation to bandy (a ball sport that differs from ice hockey in a number of key respects). Today, SVT’s audience is highly engaged concerning the maintenance of gender equal coverage. It has even received complaints concerning the sports results page, which is based on data delivered by an external company, on the grounds that it does not cover women’s sports to the same extent. SVT’s commitment to gender equal coverage is thus beginning to constrain its media partners too to engage in the generation of more gender-sensitive data. Internally, the question of gender equal coverage is now routinized in professional decisions. One male sports editor at SVT put this to Hellstrand (in 2023) as follows:

As an editor, I am always asking myself the question ‘How would we have covered this news if the same thing had happened to Mr X instead of Miss Y?’ … It does not always have to land in the same news rating as there are often valid reasons for differences. But, if you ask the question daily, and you can justify it to yourself from an equality perspective first, you will get very far.

Like Sweden, changes in coverage of women’s sports began to generate momentum in Ireland in the mid-2010s. There, women’s sports started to become a formal topic of public conversation following RTÉs live coverage of the ‘Grand Slam’ (a term for victories over all opponents in the annual Six Nations Rugby Union tournament), won by the Irish women’s rugby team in 2013. A significant momentum spurt occurred also with the inception of the aforementioned 20 × 20 campaign (Liston and O’Connor Citation2020). This was a key driver for RTÉ Sport in the formal establishment of a strategy for gender equal coverage, with aligned targets and a basic measurement system. But there were other external drivers too. These included investment and growth in women’s sports and a shift in cultural awareness (Liston Citation2014). Women have become much more involved in sport in Ireland as athletes, spectators and to a lesser extent as officials and administrators. Wider societal shifts towards gender equality culminated also in the 2022 Report of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly on Gender Equality.

Because 20 × 20 was launched outside the state-funded sports policy sector and beyond the planned launch of the first National Women in Sport Policy, financial backing of the campaign was limited. Prior to 2019, state policy on women in sport was incoherent and disjointed, owing to a lack of understanding and clear and consistent political will concerning gender equality (Liston Citation2021). Local sports partnerships (LSPs) and national governing bodies of sport (NGBs) did not receive additional funding for 20 × 20 programmes, for example. This meant that a powerful social and moral message was required to garner commitment from everyone involved, including potential sponsors. Accordingly, NGBs, LSPs and others (including sponsors, and print, broadcast, and social media outlets) were invited to stake out their role as cultural architects of transformational change. The campaign was supported by five lead sponsors – Lidl, AIG, Three, Investec and KPMG – each sharing costs and with five female athlete ambassadors (in soccer, Gaelic football, camogie, and golf). Benchmarking and pre-campaign auditing of the sports media landscape by Nielsen Research indicated that just three per cent of print sports coverage and four per cent of online coverage was given to women’s sports, while less than 20 per cent of all televised sports features related to either women only or to mixed-sex sports (Liston and O’Connor Citation2020).

This was the cultural milieu into which RTÉ became a 20 × 20 partner. O’Leary, who led RTÉ’s response, encountered a number of challenges. These revolved around the instigation of internal conversations on gender equal coverage, target setting and the need to build external partnerships with key stakeholders. The starting point was the creation of formal internal measurements of gender equal coverage to establish baseline figures against which a 20 per cent increase could be substantiated. Support was forthcoming from the then (female) Director General. A distinctive institutional challenge for RTÉ was its diverse coverage across multiple platforms: television, radio, news, online and RTÉ Player. Another was whether to incorporate qualitative and quantitative elements to its target setting and monitoring. Once agreement was reached on quantitative targets as an organisational priority, many discussions ensued about a measurement tool to collect data systematically across online news stories, radio, and televised sport. The numbers of presenters and pundits were also monitored by gender on television and radio programmes, and on TV Sports News programmes.

In this way, gender equal coverage became a standing agenda item, as was the case in SVT. O’Leary identified the EBU as one, but not the only, aggregator for women’s sports content throughout Europe. Other enablers for RTÉ Sport’s live coverage of international women’s sports included the EBU’s Sports Assembly, which gathers together sport media executives and experts. This Assembly was led by Glen Killane, former Head of TV in RTÉ, and through whom relations were established, for instance, with the Heads of Sport in Greece and Montenegro to ensure co-produced live coverage of away games played by Ireland’s national women’s football team. This, along with connections between members of the EBU and football governing bodies, UEFA and FIFA, also enabled RTÉ to mobilize input into kick-off times close to, or scheduled during, prime time television slots. At the same time, however, the interdependence of the media-sport ecosystem meant that RTÉ had no control over the quality of broadcasting facilities and infrastructure for women’s sports. This meant that the PSB had to absorb the costs of outside broadcasts and related expenses, such as overnight accommodation and the hiring of floodlights. These additional real costs mean that the economics of, and justifications for, women’s sports coverage can generate differing views within PSBs, especially where audience shares are comparatively smaller, initially at least, than for men’s sports.

Following the 20 × 20 campaign, RTÉ’s Audience Insights research found evidence of more viewers of, and listeners to, live women’s sport; 42 per cent said they listened to more live women’s sports (cited in EBU Citation2021, 60). 75 per cent of male respondents also said they had changed their mindset positively towards women’s sport (Reaper Citation2020). It is yet unclear whether RTÉ has developed, or plans to establish, a permanent data dashboard for gender equal coverage, since no data has been published by the PSB since 2021. Indeed, at the time of writing, RTÉ faces a crisis of public trust arising from revelations about undisclosed payments to a prominent presenter. In the wake of this, there was a significant decline in the number of paying licence holders. This amounted to a loss of approximately €3.7 million and the current Director-General has warned that the PSB faces an anticipated €61 million shortfall, which would amount to insolvency within one year (Public Media Alliance Citation2023).

In November 2023, Sport Ireland released an updated Women in Sport Policy, which builds on its 2019 commitment to promote gender equality and empower women in the sports sector. One important addition is ‘elevating the visibility and profile of women’s sports and women in sports’ (Sport Ireland Citation2023). This creates an important collaborative opportunity between media and NGBs. The Future of Media Commission also recommended that diversity boards be established in RTÉ, and indeed across the entire media sector, and that media ‘should be incentivized to recognize the importance of gathering data on equality, diversity and inclusion and to strive to achieve it as an aim’ (Citation2022, 49). Taken together with the recent Oireachtas report on inclusion in sport in Ireland (Joint Committee on Tourism, Culture, Arts, Sport and Media Citation2024, 10), a strategic plan for sports broadcasting and promotion now needs to be developed in Ireland to enhance diversity in sports reporting and broadcasting, set standards to be met by those in receipt of public funding and to ensure that PSB can commit, in a meaningful way, to broadcasting women’s sport on an equal basis to men’s sport. This external impetus may yet be required to ensure that gender equal coverage becomes normalized and sustained in RTÉ and other Irish broadcasters. In the absence of formal targets, default practices are already observable in Ireland. These involve an increase in the number of television sports programmes presented by the same female presenters, but with a concomitant reduction in the overall number of female experts in front of the camera. Like these experts, women behind the camera in PSB also negotiate traditional gender orders. What then of their lived experiences?

Research has noted the simplistic (mis)diagnoses adopted by some professionals about the under representation of women in media (see for example, Ross, Barlow, and Ging Citation2017). Typically, these judgements are along two lines: either that women choose not to get involved in the media profession, as if choice was universal and independent of social conditions, or that women lack the confidence to work in media. In this way, systemic and organisational conditions that reproduce the under representation of women remain hidden, often minimalised, and left unchallenged in the face of dominant market discourses in media. These discourses position any increase in coverage of women’s sports as a potential financial risk for broadcasters. It is important, then, to understand the lived experiences of women behind the camera in PSB and to consider the implications of this for those who might wish to work in media, especially sports media.

Being a woman in PSB

Both Hellstrand and O’Leary highlighted the existence of what they felt was an implicit gender bias in PSB. Of the limited research available on women in media management/leadership in Ireland, two executive directors from RTÉ also acknowledged the impact of gender bias there, which they felt had lessened over time, and 20 screen workers reported that gendered assumptions existed about the interests of male and female audiences (cited in Ross, Barlow, and Ging Citation2017). Similarly, while Swedish public service media companies have actively encouraged women to take up leadership roles, interviewees in Balkmar’s (Citation2017) research thought there were now ‘too many’ women in some leadership positions. This is a notable finding because it demonstrates that biases and assumptions are challenging to dismantle (The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Citation2023), Especially when gender equal targets are perceived as a zero-sum game of ‘top-down’ compliance. Generally this approach excludes a reconfiguration of recruitment and hiring processes and involves little reflexivity about culture change, pipeline problems and gender biases underlying decision making in the media-sport ecosystem. As a result, there are many dimensions of the career experiences of women in sports media leadership yet unknown and that arise from the ubiquity of hegemonic male-associated ideas and values.

Both Hellstrand and O’Leary encountered the challenges of explicit and implicit bias in their careers, personally and professionally, especially when it came to the subject of merit. This was experienced in two main ways: in relation to women’s sports being seen as (un)deserving of coverage in their own right and on the position of women in leadership, which involved competing ideas about competency, gender quotas, and tokenism. Certainly, quotas remain a contested issue generally. Opponents of quotas cite market self-regulation and the right of organisations to select suitable candidates and, often, competence and quotas are set against each other: specifically, it is said that those women chosen through quotas often lack the necessary competence to fulfil roles. In Sweden the quota debate has been intense and Swedish media texts positioned men as the contested norm and women as different. This intensity can be explained in part by the wide range of people in Sweden who have acknowledged gender inequalities and the many open discussions there about forms of structural change (Tienari et al. Citation2009).

Early in her media career, Hellstrand experienced daunting discussions with senior reporters who questioned why they should care about women’s sports. Indeed, there are still senior reporters in SVT today who exert a negative influence on younger female reporters through informal work practices and discourses that undermine targets around gender equal coverage. In this way, tradition was and is a barrier to change. Not only does it live ‘deep in the walls of SVT’ (Linn Hellstrand, pers. comm., December, 2023) but, as research has also affirmed, modern sport itself was incepted as a male preserve. Pushing women’s sports to the forefront was thus a constant challenge for Hellstrand who had many arduous days at work. But, as noted above, a small group bonded within SVT Sport, aided by the work of the EBU and, crucially, this included influential male allies. These were senior sports commentators who spoke publicly about their aspiration for equality on behalf of their daughters.

O’Leary had similar experiences at RTÉ. For her, the lack of parity given to women’s sports felt almost personal. There, the starting point to RTÉ’s 20 × 20 campaign was a traditional base of established production practices and ideas about men’s sports coverage: the status quo was made by men for men. Therefore, it was difficult for her to be an advocate for change without consciously separating the personal from the professional on a daily basis. At a personal level, O’Leary (Citation2022) felt a degree of psychic guilt: this related to her gender identity of being a woman in RTÉ Sport who had not prioritized gender equal coverage. She did not recognize this bias until she was questioned in 2014 by an external female member of RTÉ’s Audience Council about gender equal sports coverage. Upon identifying her own and others’ unconscious biases, O’Leary found that it became impossible to unsee these or turn a blind eye to them. Her realisation that merit was a social construction, and not a fixed universal entity, was also important in this regard because it spurred her to build a circle of support from within RTÉ, and also externally with the EBU and Swedish colleagues. Completing postgraduate study enabled her to understand that change management was challenging for those male and female sports media professionals with little or no expertise or interest in women’s sports, who may not have known any female sports experts and whose vision of reality was redefined by 20 × 20.

In these ways, both O’Leary and Hellstrand experienced forms of emotional labour involved in dealing with other people’s feelings. One core component of this was the necessary regulation of their own emotions in the face of the need to sustain a focus on gender equal coverage in daily work. This required them to be consciously engaged in the dissolution of gendered attitudes, values, and norms. O’Leary observed cycles of grief, anger and change experienced by male and female colleagues at RTÉ Sport during the introduction of formal targets for women’s sports coverage. This was unsettling and challenging for some, especially where targets were perceived as having been imposed swiftly and without much consultation. This was a function of resistance to change at individual level, but it was also part of an institutional problem involving the economic necessity to maximise audiences and the related tendency to be risk averse. Much of men’s sport history has been mediatised (Whannel Citation1992) i.e. extensively recorded, and regularly replayed by television in the form of anniversaries, commemorations, and ‘backstories’ to upcoming events. Seasoned male and female sports staff in RTÉ Sport have been fully immersed in this gendered male sports history for many years. There is no comparable mediatisation of histories and traditions for women’s sports yet. There are also limited television archives for women’s sports which PSBs can access. Consequently, in setting out to achieve gender equal coverage, one of the key challenges for RTÉ and other PSBs is to create a sense of history, tradition, ‘great teams’ and individual celebrities in women’s sport, by thinking creatively about how to use television (Hurley 2020, cited in Liston Citation2020).

Working with and on women’s sports to achieve gender equal coverage requires risk-taking on the part of PSBs, who by their status are intended to be relatively free from commercial constraints. There is growing competition in Ireland, and throughout Europe, between state, public service and privately-owned broadcasters for public service content production. In some countries, like Germany, Denmark, and Greece, for instance, the licence fee has been replaced with a household broadcasting charge, thus reducing the same pressures of reliance on licence fees as critical to the future of PSB. But PSBs exist in a competitive media environment and with ongoing changes associated with digitalization and commercialzation. The paper now concludes by reflecting on these issues and offering ideas for potential future lines of research enquiry.

Current issues and future lines of enquiry

This paper makes three important contributions. First is to the growing field of research on media, and to sports media specifically, which is the ‘last bastion [of media] under men’s exclusive control’ (Ross and Padovani Citation2017, 9). Here, insights were offered into the realpolitik of sport as emotional labour for women in PSB, their acculturation into and experiences of challenging existing male-oriented norms, and how different PSBs, in Sweden and Ireland, have responded to the push for gender equality. Second is to research-industry collaboration on questions that have equal real world and academic value. From this work it is apparent that females who take a stance in relation to gender equal coverage within media organisations must be adequately supported. Through their efforts, women have built and continue to build their own informal occupational networks in PSBs but much of this is non-monetised emotional labour, in which they work not only to make a living and carve out a career in sports media but also, crucially, to achieve self-actualization. Third is to gender-sensitive public discourse and policy debates in and about the media-society-sport ecosystem. As a research theme, ‘women-media-sport’ sits at the junction of several overlapping policy areas and institutional practices. These include the promotion of gender equality at European level and in different national contexts; media policies and practices on gender mainstreaming that vary across time and space; and international and national sports policies that now engage with various dimensions of gender equality and the public visibility of women’s sports. Across Europe, many PSBs have developed formal gender equality structures which compare quite favourably with private and not-for-profit media organisations and co-operatives (Ross Citation2014).Footnote3 The continued success of female athletes and male allyship are two crucial elements in advancing gender equal coverage. But it is important too to acknowledge that male allies may also feel relatively isolated, given that sport and sports media are acutely gendered environments, historically and culturally speaking.

The accounts of those women working in PSB also highlight the impact of financial constraints on securing sports broadcasting rights. This is a challenging competitive market. Consequently, strong leadership and creativity is required from PSBs to match privately-owned competitors. This challenge is accentuated by the dominance of men’s sports coverage in international news aggregators such as PA Media Group (formerly the Press Association). Accordingly, more financial investment is required from, and for, PSBs in order to equalize the landscape of gendered sports coverage. There is also added difficulty on PSBs to deliver gender equal coverage because of the varied readiness of women’s sports (in terms of human and physical infrastructure) for media packaging and broadcasting throughout the world. To maintain momentum in this direction, targets for gender equal coverage need to inform all domestic decision-making on rights.

More research is needed to understand whether and how policies have been adopted by media organisations to promote gender equal sports coverage. Such work needs to consider the contribution to be made by PSBs as well as any obligations upon them, normative and/or legal. The experiences of women within PSB workplaces should inform future moves to generate sex- and gender-based disaggregated data across multiple media platforms in these organisations. Longitudinal data about gender-equal coverage, within RTÉ, SVT and other media providers, will also be needed to facilitate ongoing engagement between stakeholders in the space between women’s sports and media. Certainly, the Irish and Swedish examples highlight the need to sustain monitoring cycles of gender equal coverage because ‘declaring something is so is not same as its being so’ (Byerly and Padovani Citation2017, 22). But a digitally literate and gender-sensitive audience can also anchor civic conversations about data measures (compulsory or optional) to bring about gender equal coverage. The adoption of the Gender Equality in News Media Index (GEM-I) tool (Machari and Barata Mir Citation2022) could be one such initiative to enable RTÉ, SVT, and other PSBs to furnish open-source reports on gender equality targets.

Further insights are also needed on gendered social trends and employment patterns in sports media and into sports media work and emotional labour. Media companies will need to engage in a more reflexive understanding of the gendered nature of their organisational environments that goes beyond sole, or clusters of, male allies working in tandem with female colleagues to effect meaningful and sustainable cultural change. The ‘how’ behind the translation of hegemonic gendered ideologies into organisational media practices also requires much more exploration in terms of daily rationalisations for behaviours and decisions, arguments played out in meetings and in internal memos, and which mean that some positions are heard while others are marginalised or ignored. The sustained visibility of women as sports experts on televised, radio and online sports broadcasting is also critical in challenging stereotypical views of men in authoritative roles.

Given the rapid pace of change in media production, notably the growth in social and participatory media, the entire portfolio of PSB content needs to be constantly reviewed in relation to gender equality. The challenge for all PSBs is not only to sustain audiences who are interested in women’s sports but also to grow these through the production of content that reaches beyond sports, potentially into areas of health, embodiment, and social justice for example. In this context, the triad of PSB functions remains as important as ever - to inform, educate and entertain audiences about and through gender equal sports coverage. This approach will require clarity of purpose and consistency of approach across all PSB divisions. Further research might also explore where women’s sports stories are positioned, institutionally, on the soft news-hard news binary (North Citation2016), and how these are perceived publicly by audiences.

Finally, few media organisations can now ignore the push for gender equality because it is recognized much more as good business practice. Still, the more common approach in European media policy has been on media plurality and universal access (Ross and Padovani Citation2017). Meanwhile, in contemporary sport, common practice is to adopt policies around equality, diversity and in, but there is a tension in addressing gender equality amid increasing diversity. Lessons can be learned from the Swedish experience of gender mainstreaming since it was first proclaimed a major political strategy in 1994. The ‘drawn-out’ institutional mainstreaming process there (Sainsbury and Bergqvist Citation2009) was vulnerable to inertia and policy slippage, especially when it leaned on personal commitment. Gender mainstreaming the routines of Swedish government offices over a 12-year period was ‘an impressive and sobering achievement’ (Sainsbury and Bergqvist Citation2009, 229).

What might this mean for future efforts to introduce gender mainstreaming into the fields of public service media and sport? Changes resulting from these efforts might supersede the need for positive measures for women, and goals might be displaced, potentially resulting in integration into existing unequal power structures. It is important then that a redistribution of economic and social power is also addressed in and through any changes that result from mainstreaming the public policy process. It would be naïve also to minimise potential resistance to gender equality in sports media (and sport more generally). Typically, the exclusion or under-representation of women from/in sport media-as-work elicits competing responses: either that greater diversity in workforces today makes equality practically redundant; or to press the case for accommodating women’s particular interests and acknowledging them as gender-differentiated sports media professionals. Neither position is sufficient to achieve gender equality or gender equal coverage in and of itself. Indeed, much of the history of gender equality has been trapped between ideas of sameness and difference arising from the Wollstonecraft dilemma (Pateman Citation1989).

Talking about diversity usually involves ideas and values about the benefit of difference, such as racial/ethnic diversity for example, and the improvement of human capital. The focus on diversity, including the conflation of equality, diversity and inclusion, threatens gender equality in a number of ways: by losing sex/gender in the diversity package; by privileging other dimensions of inequality over sex/gender in theory and practice; by diminishing the importance of group inequalities which is an essential concept to understanding systemic gender inequalities; and by linking diversity strongly to human resource management and business priorities. The latter also risks passing over the crucial relationship between paid and unpaid work, and the second shift (Hochschild Citation1989), that underpins so much gender inequality. Crucially, gender must remain a crosscutting axis at this point in time or the outcome could be a rhetorical, muted, even stalled, evolution when it comes to gender equal sports coverage. The enduring questions remain: who are the women to be represented in this coverage, who decides and why?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For example, Liston and O’Leary collaborated during and after an international research symposium on Media and Sport, held in Galway (Ireland) in May 2022, and on the design of an all-Ireland higher education workshop for undergraduate students on sport, media, and gender. This workshop was piloted at the time of writing, supported financially by Sport Ireland’s Women in Sport fund and was instigated in collaboration with the Olympic Federation of Ireland’s Gender Equality Committee.

2 Jönsson joined SVT as a reporter in 1999. She became sports programming anchor and commentator, sports project manager and then head of SVT Sport online and head of sports development. In 2022, she resigned from SVT to become general secretary of the Swedish Olympic Committee.

3 Irish Near Media Co-op is one such example of a not-for-profit media co-operative based in Dublin North-East. It has adopted an anti-harassment policy and claims to hold awareness-raising training and editorial discussions on gender portrayal (Council of Europe Citation2020).

References

- 20x20. 2020. “The Long Road Documentary.” https://shorturl.at/jrHP7

- Antunovic, Dunja, and Sunčica Bartoluci. 2023. “Sport, Gender, and National Interest during the Olympics: A Comparative Analysis of Media Representations in Central and Eastern Europe.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 58 (1): 167–187. doi:10.1177/10126902221095686.

- Arriaza Ibarra, Karen, Eva Nowak, and Raymond Kuhn, eds. 2015. Public Service Media in Europe: A Comparative Approach. London: Routledge.

- Balkmar, Dag. 2017. “Sweden: Too Many Women? Women and Gender (in)Equality in Swedish Media.” In Gender Equality and the Media: A Challenge for Europe, edited by Karen Ross and Claudia Padovani, 208–219. London: Routledge.

- Boje, Thomas P., and Anders Ejrnæs. 2012. “Policy and Practice: The Relationship between Family Policy Regime and Women’s Labour Market Participation in Europe.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 32 (9–10): 589–605. doi:10.1108/01443331211257670.

- Born, Georgina. 2005. “Digitising Democracy.” The Political Quarterly 76 (s1): 102–123. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2006.00752.x.

- Byerly, Carolyn, and Claudia Padovani. 2017. “Research and Policy Review.” In Gender Equality and the Media: A Challenge for Europe, edited by Karen Ross and Claudia Padovani, 7–31. London: Routledge.

- Council of Europe. 2020. Gender Equality and Media – Analytical Report. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Steering Committee on Media and Information Society.

- Crolley, Liz, and Elena Teso. 2007. “Gendered Narratives in Spain: The Representation of Female Athletes in Marca and El País.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 42 (2): 149–166. doi:10.1177/1012690207084749.

- Djerf-Pierre, Monika and Mats Esktröm, eds. 2013. A History of Swedish Broadcasting: Communicative Ethos, Genres and Institutional Changes. Sweden: Nordicom and the Swedish Foundation of Broadcast Media History.

- Ekström, Mats and Monika Djerf-Pierre. 2013. “Approaching Broadcast History: An Introduction.” In A History of Swedish Broadcasting: Communicative Ethos, Genres and Institutional Changes, edited by Monika Djerf-Pierre and Mats Esktröm, 11–30. Sweden: Nordicom and the Swedish Foundation of Broadcast Media History.

- European Broadcasting Union. 2021. “Reimagining Sport: Pathways to Gender-Balanced Media Coverage.” Eurovision Sport. https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/Publications/strategic/open/Reimagining_Sport.pdf.

- Ferrell Lowe, Gregory and Jo Bardoel, eds. 2007. From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. Sweden: Nordicom.

- Flynn, Roddy. 2020. “A Level Playing Field? Irish Broadcast-Sports Rights and the Decline of the National.” In Sport, the Media and Ireland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Neil O’Boyle and Marcus Free, 227–246. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Future of Media Commission. 2022. “Report of the Future of Media Commission.” https://shorturl.at/lKRSY.

- Goodman, David. 2011. Radio’s Civic Ambition: American Broadcasting and Democracy in the 1930s. London: Oxford University Press.

- Hendy, David. 2013. Public Service Broadcasting. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hobson, Barbara. 2003. “Recognition Struggles in Universalistic and Gender Distinctive Frames: Sweden and Ireland.” In Recognition Struggles and Social Movements, edited by Barbara Hobson, 64–92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hochschild, Arlie. 1989. The Second Shift. New York: Avon Books.

- Horgan, John, and Roddy Flynn. 2017. Irish Media: A Critical History. Dublin: Four Courts Press.

- Hultén, Olof. 2007. “Between Vanishing Concept and Future Model: Public Service Broadcasting in Europe on the Move.” In Power Performance and Politics: Media Policy in Europe, edited by Werner A. Meier and Josef Trappel, 197–222. Germany: Meier.

- Inglis, Ken. 2002. “Changing Notions of Public Service Broadcasting.” Southern Review: Communication, Politics & Culture 35 (1): 9–20.

- Joint Committee on Arts, Sport, Tourism, Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs. 2005. “Women in Sport.” http://archive.oireachtas.ie/2004/REPORT_20040701_0.html

- Joint Committee on Tourism, Culture, Arts, Sport and Media. 2024. “Report on Inclusion in Sport.” Accessed March 3, 2024. https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/committee/dail/33/joint_committee_on_tourism_culture_arts_sport_and_media/reports/2024/2024-02-27_report-on-inclusion-in-sport_en.pdf

- Laine, Anti. 2016. “Gender Representation of Athletes in Finnish and Swedish Tabloids.” Nordicom Review 37 (2): 83–98. doi:10.1515/nor-2016-0012.

- Larsson, Håkan. 2021. “The Discourse of Gender Equality in Youth Sports: A Swedish Example.” Journal of Gender Studies 30 (6): 713–724. doi:10.1080/09589236.2021.1937082.

- Liston, Katie, and Mary O’Connor. 2020. “Media Sport, Women and Ireland: Seeing the Wood for the Trees.” In Sport, the Media and Ireland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Neil O’Boyle and Marcus Free, 133–149. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Liston, Katie. 2014. “Revisiting Relations between the Sexes in Sport on the Island of Ireland.” In Norbert Elias and Empirical Research, edited by Tatiana Landini and Francois Dépelteau, 197–219. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liston, Katie. 2020. “Women, Media and Sport in Ireland: A Round-Table Discussion.” In Sport, the Media and Ireland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Neil O’Boyle and Marcus Free, 374–422. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Liston, Katie. 2021. “Honour and Shame in Women’s Sports.” Studies in Arts and Humanities 7 (1): 5–17. doi:10.18193/sah.v7i1.199.

- Löfgren Nilsson, Monika. 2013. “A Long and Winding Road: Gendering Processes in SVT News.” In A History of Swedish Broadcasting: Communicative Ethos, Genres and Institutional Changes, edited by Monika Djerf-Pierre, and Mats Esktröm, 171–194. Sweden: Nordicom and the Swedish Foundation of Broadcast Media History.

- Machari, Sarah, and Joan Barata Mir. 2022. Global Study: Gender Equality and Media Regulation. Linnaeus University: Fojo Media Institute.

- Media Academy. 2020. “The Confidence Barometer 2020.” https://medieakademin.se/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Presentation_fortroendebarometern_2020.pdf.

- Milliken, Robert. 1996. “Sport is Murdoch’s “Battering Ram” for Pay TV.” Independent, October 15.

- Murphy, Kenneth. 2007. “Institutional Change and Irish Public Broadcasting.” Irish Studies Review 15 (3): 347–363. doi:10.1080/09670880701461886.

- Nord, Lars, and Torbjörn Van Krogh. 2021. “Sweden: Continuity and Change in a More Fragmented Media Landscape.” In The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How Leading News Media Survive Digital Transformation. Vol. 1, edited by Josef Trappel and Tales Tomaz, 353–380. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- North, Louise. 2016. “The Gender of ‘Soft’ and ‘Hard’ News.” Journalism Studies 17 (3): 356–373. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.987551.

- Nygren, Karina, Julie Walsh, Ingunn Ellingsen, and Alastair Christie. 2021. “Gender, Parenting and Practices in Child Welfare Work? A Comparative Study from England, Ireland, Norway and Sweden.” The British Journal of Social Work 51 (6): 2116–2133. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa085.

- O’Boyle, Neil, and Marcus Free. 2020. “Introduction.” In Sport, the Media and Ireland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Neil O’Boyle and Marcus Free, 1–28. Cork: University Press.

- O’Leary, Cliona. 2022. “Gender Equality in Sports Media: Reflections on the Design and Implementation of a Change Framework.” In Media, Sport and Ireland International Symposium. National University of Galway, May 19–20.

- Ottesen, Laila, Berit Skirstad, Gertrud Pfister, and Ulla Habermann. 2010. “Gender Relations in Scandinavian Sport Organizations – A Comparison of the Situation and the Policies in Denmark, Norway and Sweden.” Sport in Society 13 (4): 657–675. doi:10.1080/17430431003616423.

- Pateman, Carole. 1989. “The Patriarchal Welfare State.” In The Disorder of Women: Democracy, Feminism and Political Theory, edited by Carole Pateman, 179–209. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Plantenga, Janneke, Chantal Remery, Hugo Figueiredo, and Mark Smith. 2009. “Towards a European Union Gender Equality Index.” Journal of European Social Policy 19 (1): 19–33. doi:10.1177/0958928708098521.

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao. 1993. “The Role of Core Competencies in the Corporation.” Research-Technology Management 36 (6): 40–47. doi:10.1080/08956308.1993.11670940.

- Public Media Alliance. 2022. “SVT Sport: A World Leader in Equal Sports Coverage.” https://www.publicmediaalliance.org/svt-sport-a-world-leader-in-equal-sports-coverage/

- Public Media Alliance. 2023. “RTÉ Facing Insolvency as Global Pressure on Licence Fees Continue.” https://shorturl.at/gwG47

- Reaper, Luke. 2020. “20 x 20 Press Release.” https://banda.ie/20x20-press-release/

- Ross, Karen and Claudia Padovani, eds. 2017. Gender Equality and the Media: A Challenge for Europe. London: Routledge.

- Ross, Karen, Charlotte Barlow, and Debbie Ging. 2017. “UK and Ireland: Employment, Representation and the 30 Percent Cul-de-Sac.” In Gender Equality and the Media: A Challenge for Europe, edited by Karen Ross and Claudia Padovani, 220–231. London: Routledge.

- Ross, Karen. 2014. “Women in Media Industries in Europe: What’s Wrong with This Picture?” Feminist Media Studies 14 (2): 326–330. doi:10.1080/14680777.2014.909139.

- Sainsbury, Diane, and Christina Bergqvist. 2009. “The Promise and Pitfalls of Gender Mainstreaming.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 11 (2): 216–234. doi:10.1080/14616740902789575.

- Scannell, Paddy, and David Cardiff. 1991. A Social History of British Broadcasting Vol. 1 - 1911–1939: Serving the Nation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Smith, David. 2023. “Men as the Missing Ingredient to Gender Equity: An Allyship Research Agenda.” In A Research Agenda for Gender and Leadership, edited by Sherylle Tan and Lisa DeFrank-Cole, 141–154. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Sport Ireland. 2023. Women in Sport. Dublin: Sport Ireland. https://shorturl.at/fsFT6.

- TAM Ireland/Nielsen. 2023. “Women’s World Cup: Key Figures to Date.” https://mediasales.rte.ie/wp-content/uploads/WWC-Graphic-2023.pdf

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2023. “Social Institutions and Gender Index 2023 Global Report: Gender Equality in Times of Crisis.” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/sigi-2023-global-report_4607b7c7-en

- Tienari, Janne, Charlotte Holgersson, Susan Meriläinen, and Pia Höök. 2009. “Gender, Management and Market Discourse: The Case of Gender Quotas in the Swedish and Finnish Media.” Gender, Work & Organization 16 (4): 501–521. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00453.x.

- Túñez-López, Miguel, Martin Vaz-Álvarez, and César Fieiras-Ceide. 2020. “Covid-19 and Public Service Media: Impact of the Pandemic on Public Television in Europe.” El Profesional de la Información 29 (5): E290518. https://revista.profesionaldelainformacion.com/index.php/EPI/article/view/85717/62543. doi:10.3145/epi.2020.sep.18.

- Vipond, Mary. 1992. Listening in: The First Decade of Canadian Broadcasting, 1922–1932. Montreal: Mc-Gill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wanneberg, Pia Lundquist. 2011. “The Sexualization of Sport: A Gender Analysis of Swedish Elite Sport from 1976 to the Present Day.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 18 (3): 265–278. doi:10.1177/1350506811406075.

- Whannel, Gary. 1992. Fields of Vision: Television Sport and Cultural Transformation. London: Routledge.

- White, Julia, and Jean McArdle. 2022. “Analysis of Government Policy Relating to Women’s Sport.” In The Routledge Handbook of Gender Politics in Sport and Physical Activity, edited by Gyozo Molnár and Rachel Bullingham, 59–60. London: Routledge.