Abstract

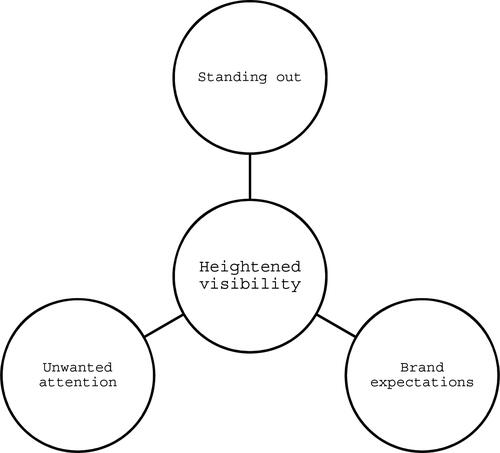

Women working in sports media contend with unwanted attention during their careers, extending beyond evaluations of their knowledge to encompass judgements of their appearances and emotional management. Using Banet-Weiser’s framework of popular feminism, within the ‘economies of visibility’, this research explores the experiences and strategies of women in sports media as they navigate increased visibility. Working as a researcher-insider, the first author conducted semi-structured interviews with seven women working in sports media (early career to 35 years’ experience), working in the UK and/or Ireland, across TV, radio, print and/or online formats. Collaborative reflexive thematic analysis by both authors resulted in the construction of two themes around ‘heightened visibility’ (including a subtheme of standing out) and ‘blending in’. The findings indicate that while women are increasingly visible in the industry, the gender dynamics and conditions of the sports media workplace have not progressed to the same extent.

Introduction

In December 2022 during ITV coverage of the men’s World Cup match between Brazil and South Korea, pundit and former England footballer Eni Aluko gave an incorrect statistic on the goal scoring record of Brazil player Richarlison. Following the comment Aluko faced a barrage of abuse on social media, where her football knowledge and ability were trivialised, not her first experience of the media questioning her legitimacy (Velija and Silvani Citation2021). In July 2022, experienced Gaelic games commentator Ursula Jacob commented ‘enough is enough’ in a detailed Twitter post where she condemned the ‘nasty personal comments’ that she regularly receives in her work for the state broadcaster RTÉ in Ireland. Further afield, American sportscaster Julie DiCaro has written a book documenting her experiences of casual misogyny, covert and overt sexism, and male-driven toxicity in the sports media workplace (DiCaro Citation2022). These examples are just a snapshot of recent experiences of women working in the sports media industry.

Sport perpetuates the idea of male superiority more than many other institutions and Bruce (Citation2008) notes how the association between sport and maleness is so taken for granted in sports media that it goes unchallenged. Bernstein and Kian (Citation2013) comment that men dominate all ranks of sports journalism, and this is reflected in a masculine, macho-oriented workplace (Schmidt Citation2015). This presents challenges for those who are deemed different to the norm, particularly women, with the unspoken assumption that they are less credible (Hardin and Shain Citation2005), less trustworthy (Mudrick et al. Citation2017) and they simply do not know as much about sport as men. Women working in sports media experience gender bias, stereotyping, harassment, double standards and a precarious work environment (Everbach Citation2018), while they are also subjected to the male gaze (Cummins, Ortiz, and Rankine Citation2019). The sexism and gender role stereotyping that women endure are a threat to their retention in the industry, where women will leave as quickly as they enter the profession. Antunovic (Citation2022) suggests that we need to consider how structures and cultural norms shape ideologies in the sport media industry, while women’s voices need to be situated at the centre in order for change to take place (Antunovic Citation2019).

This research examines the experiences of women sports journalists, reporters and contributors working in sports media in the UK and Ireland. More specifically, the authors explore how these women navigate the enhanced visibility of the new media era and how they negotiate ‘standing out’ in an otherwise male dominated industry. This paper is the second in a series of papers from the authors on the topic, following an examination of responses to audience interactions from women working in sports media (Kitching and Sheehan Citation2023). The themes explored across the project cover elements of visibility and vulnerability (this paper) to internal and external responses to online interactions (Kitching and Sheehan Citation2023) along with work practices and conditions.

Literature review

While the percentage of women sports editors, columnists, designers and managers working in the USA in recent years has increased, the improvements have been marginal, revealing a sports media industry that is predominantly white and male (Lapchick Citation2021). Similarly, Franks and O’Neill (Citation2016) suggest that the proportion of women sports journalists in print media in the UK is lower than that of other countries, and this is supported in a survey by Schmidt (Citation2018) which found that because women in the UK reported far more obstacles and greater discrimination than male journalists, they were much less likely to write articles. In spite of these reports, anecdotally at least, the visibility of women in sports media has undoubtedly increased in recent years – particularly in broadcasting – with the likes of Gabby Logan and Clare Balding as household names in the UK and similarly Joanne Cantwell and Jacqui Hurley in Ireland. The upward trend in this increased visibility has likely been buoyed by the #MeToo movement, along with other campaigns such as #MorethanMean in America and the #20 × 20 campaign (Liston and O’Connor Citation2020). The latter campaign, which took place in Ireland, aimed to garner a 20% increase in media coverage of women in sport. This snowballed into the increasing prominence of women broadcasters, particularly on state radio and television. In these preceding years, it could be argued that sports media departments have begun to trade in an economy of visibility, where, coinciding with an era of popular feminism, (Banet-Weiser Citation2018) simply placing women in a broadcast might be considered progress given the historic lack of visibility of women in such positions. However, affording women these roles does not change the structures that support them in their workplace.

With the increased visibility of women comes expectations in terms of how these broadcasters appear and carry themselves. Women in sports media are routinely scrutinised on their physical appearance and are susceptible to visual objectification (Cummins, Ortiz, and Rankine Citation2019), with audience members giving more of their visual attention to women reporters’ bodies than their faces, relative to male reporters (Cummins, Ortiz, and Rankine Citation2019). Davis and Krawczyk (Citation2010) analysed women sportscasters’ physical appearance and found that women who appeared attractive were considered competent, expert, dynamic and trustworthy, except when they are highly attractive. Not alone their looks but their voices are also scrutinised; in examining audience reactions to women sports podcasters, Yang et al. (Citation2022) found that auditory cuteness positively correlated with audience information satisfaction and perceived attractiveness, both of which predicted perceived expertise. Harrison (Citation2019) suggests that women sportscasters tend to be hired more for their looks than their knowledge and skills; many of the ten women he interviewed felt as though they must wear less conservative clothing and saw no reasonable alternative. He calls the pressure placed on women broadcasters to dress provocatively as ‘nightclubification’ and describes it as the appearance double standard, a deeply rooted, systemic practice which diminishes the perceived credibility of women sportscasters (Harrison Citation2021). Harrison (Citation2019) suggests that this double standard contributes to a notion of women sportscasters constructing a femininity that exists for the purpose of heterosexual men, and it may greatly inform other challenges encountered by women working in sports media. Toffoletti et al. (Citation2021) lean on Duffy and Hund (Citation2019) in suggesting that the cost of increased visibility is often a heightened degree of vulnerability.

The enhanced visibility of women broadcasters in sport has attracted new levels of online harassment, vitriol, violence and abuse targeted at these women. In their analysis of Facebook and Twitter, Kavanagh, Litchfield, and Osborne (Citation2019) found that social media provides a space for unregulated cyberhate targeting high profile sportswomen in their workplace, with similar findings from Bowes, Matthews, and Long (Citation2023) in their analysis of women football pundits. Everbach (Citation2018) found that online harassment as a relatively new dimension aiming to subordinate women through criticism, insults and threats is succeeding at driving women away from sports media, particularly younger women. Garcia and Proffitt (Citation2022) examined how one sports podcast brand ‘Barstool Sports’ used online violence and consistently attacked women sportscasters, reasserting the dominance of white, heterosexual, hegemonic masculinities. In their view, social media has become a space for men to reclaim power through mobilising online violence against women, and as a bid to silence women’s voices, thereby normalising repressive conditions and perpetuating white male conservative ideologies. This practice will be further examined in the next section as the construct ‘popular misogyny’.

Theoretical approach

Sarah Banet-Weister has spoken about the interest of feminist media scholars in the politics of visibility, and the shift that has taken place to economies of visibility (Banet-Weiser Citation2015). Economies of visibility promote an understanding of how identities are constructed and give value to individuals – particularly women and girls – to make themselves visible via media representation. In this way, women are considered in the economic space, where not only are they compelled to find innovative solutions to gender discrimination, but they are encouraged to visibly demonstrate their entrepreneurial abilities (Banet-Weiser Citation2015). Under this framework, reactions to gender inequalities are framed by individual economic and entrepreneurial discourses (Thorpe, Toffoletti, and Bruce Citation2017). Banet-Weiser (Citation2015) says that the product in gendered economies of visibility is the feminine body, where its value is judged and scrutinised, while the regulation and production of the visible self serves up bodies as commodities and creates the body and the self as a brand. This type of framework can place more responsibility on women themselves – rather than their employers or the institutions they are a part of – to generate work, publicity or media coverage and create their own brand (Toffoletti and Thorpe Citation2018). Similarly, Harrison (Citation2021) suggests that discourses of agency and empowerment are problematic in sports media, whereby they call on women to self-regulate their bodies and appearances. This contradiction only serves to lessen women’s credibility in the sports media industry.

Banet-Weiser also writes about ‘popular feminism’ as part of the economy of visibility, something which has ebbed and flowed but took hold following the #metoo movement in 2017 (see Banet-Weiser and Portwood-Stacer Citation2017). Popular feminism refers to conditions whereby individuals and organisations have their feminism seen, liked, retweeted and shared, and accessible to the broad public. These practices seek to capitalise on the popularity of feminist discourse, but there are no real critiques or problematising of patriarchy. In this way, popular feminism does little to address and remove barriers that prevent true gender equity (Banet-Weiser Citation2018). Through popular feminism, there is recognition of the growing number and prominence of women contributors in sports media, yet this growing number may not change the structures or institutions within which they operate. Banet-Weiser suggests that under popular feminism, simply bringing women to the table becomes the solution for all gender problems; however the mere presence of women does not necessarily challenge structures (Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020). Positive developments such as the increase in the number of women working in sports media hides deep seated gender inequalities, for example structural factors such as hiring processes and career opportunities (Sherwood, Nicholson, and Marjoribanks Citation2018). Popular feminism flourishes in popular culture and media, where it is closely connected to the neoliberal principles of individualism, self-entrepreneurialism, economic success and new market growth, all of which exist within and alongside the economies of visibility.

A trend that has grown alongside popular feminism is popular misogyny (Banet-Weiser Citation2018), which can be seen particularly in the online harassment of women in male dominated cultures or industries. As Banet-Weiser (Citation2018, 5) explains, contemporary misogyny submits that ‘men are suffering because of women in general, and feminism in particular’, and ‘…every space or place, every exercise of power that women deploy is understood as taking that power away from men’. Popular misogyny is a violent response to popular expressions of feminism and is cultivated and circulated via social media networks and responds to the possibility that ‘patriarchy and masculinity are under threat’. Under popular feminism, there is an assumption that women sports journalists are empowered, when it is more likely that the increased attention and profile brings harassment, typecasting, unfair criticisms, gender bias, double standards and a precarious work environment (Harrison Citation2021). Thus, the woman is not truly empowered and does not have a choice. At the same time, as demonstrated by the examples in the opening paragraph, the growth in popular misogyny means that there is a cohort of male consumers of sport who are not happy with women’s increased visibility and presence in sports media.

In this paper, the authors attempt to use Banet-Weiser’s popular feminism/misogyny as a frame to understand how women working in sports media shape and manage their visibility, particularly in relation to their appearance and their public facing interactions. Using popular feminism/misogyny allows us to illuminate the contradiction of needing to be visible for their work (popular feminism), but suffering this increased visibility (popular misogyny), all operating within a working environment and sports media culture that upholds capitalist and neo-liberal values. The economies of visibility can provide a mechanism to show how women journalists manage their visibility, while also highlighting contradictions they experience in promoting and/or protecting their work and themselves. The researchers try to use these frameworks in a critical way, acknowledging the implication that these women must often take responsibility for generating interest and broadcasting a positive image. Thus, this paper focuses on visibility and recognition for these women but does not go as far as covering elements of the division of labour, economic dispositions, resources and allies or peer to peer support, some of which will be further investigated in our third paper.

Methods

As earlier mentioned, this paper is one of three studies examining women’s views on their experiences in the sports media industry. Semi-structured interviews were deemed the most suitable method in order to tease out detailed responses from the participants. Both authors drew up a carefully selected interview guide, with topics covering visibility, presentation, appearance and social media use and interactions, all of which were important in informing the data for this paper.

All participants must have been working in the UK and/or Ireland in at least one of TV, radio, print and/or web/online media in any public facing role, e.g. journalists, broadcasters, reporters or contributors. All study participants had to also be active or were active on at least one social media platform. With the first author working in the sports media space for over a decade, her position as a researcher insider was advantageous in terms of access and thus snowball sampling was utilised, with participants offering contact details for other potential participants. Given her position, the first author kept a reflexive journal throughout the data collection and analysis phases. Ethical approval for the research was granted through the authors’ institution.

All participants were white and came from various levels of tenure in the industry, e.g. working freelance, part time or in permanent roles. None of the participants had experience of racial or ethnic exclusion or inequalities, which is a significant limitation of a project of this kind. While these studies are growing in number, e.g. Coche (Citation2022), we acknowledge that we can and should do more to reach women and participants beyond Western environments and white ethnicities.

The interviews were conducted by the first author online via Microsoft Teams in March and April 2022. Prior to the interviews, participants were invited to read an information sheet and all participants gave informed consent via signed forms. Each interview lasted from 45 to 90 minutes. All participants were asked the same series of questions, with various follow-up questions depending on their answers. The first author’s reflexive journalling through this period helped her to shape and adapt questions for future interviews, while it allowed constant introspection and reflection during this writing process. Following the seventh interview, the researchers deemed that enough information had been obtained and moved to the analysis stage.

The audio was gathered and transcribed through the Microsoft Teams app. The first author began the process of reviewing the transcripts for accuracy, and this initial familiarisation with the data became another opportunity to journal. From this phase onwards the data were constantly proofed to ensure participant anonymity, which was a keen concern for the authors. All participants were given pseudonyms and potential identifiers were removed, e.g. mention of workplaces, colleagues, or specific public interactions on social media. We included the participants’ current roles and whether they work in men’s/women’s sport, but given that some of the contributors cover one particular sport, specific mention of sports and venues or stadia had to be removed to protect their identities. We also decided to omit the number of years they work in sports media, except to identify them as early career, mid-career or late career, with the most experienced participant having 35 years’ experience in sports media. Interview transcript review (ITR) was utilised for participants to check their transcripts and one participant returned revisions to their transcript, all of which was to maintain anonymity. Once this paper was fully written it was circulated to the interviewees to check for aspects of anonymity. The following are the pseudonyms and details of the seven women interviewed for this project ().

Table 1. Participant information.

Analysis

The researchers employed Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis (TA) to analyse the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, Citation2021a, Citation2021b), and through this process made a concerted effort to develop their analytic sensibility (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). Reflexive TA is becoming increasingly employed in sports related research, and Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) discuss the importance of the researcher(s) engaging reflectively and thoughtfully with the data and the process of analysis. Reflexivity acknowledges the role of the researcher(s) as an active agent in the production of knowledge and the researchers were guided by worked examples and author accounts of doing reflexive thematic analysis (Byrne Citation2022; Trainor and Bundon Citation2021). We know that through reflexive TA, theme generation is an active and creative process that is not separate from the researchers but generated by them. In this way, the combination of the first author’s reflective journal and critical interactions between the first and second authors allowed the researchers to challenge biases that might have arisen from the first author’s familiarity with the research participants and her position in the field, while it also informed us as to how the themes were constructed.

Intertwined in the reflexive TA process was the economies of visibility/popular feminism framework. From the outset of the project, the authors’ aim was to explore the experiences of women working in sports media, but through the reading, framing and data collection process this became a three-pronged approach to examining gendered sports media culture. As earlier mentioned, the data we were interested in for this paper revolved around the question of how women working in sports media experience the visibility that comes with their role in sports media.

While we acknowledge that reflexive TA is not linear and cannot be overly systematic (Braun and Clarke Citation2013) we followed the Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) six steps of reflexive TA. Following initial familiarisation with the transcripts, phase two involved complete coding (Braun and Clarke Citation2013), where the authors identified initial codes, searching for evidence of the women managing their visibility and promoting/protecting their work. Both coding separately, the researchers attempted to be inclusive, thorough, and systematic in this process, invoking the framework to identify implicit meanings or assumptions beyond the obvious. A second coding phase helped to refine and simplify the codes, at which point we came together to start phase three and identifying patterns in the data. Here we tried to organise the codes, topics and issues and the process became more visual, where we developed a thematic map to clarify the relationships between patterns. This became a process of building the themes and ensuring that each theme had a central organising concept and here we used the Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) list of good questions to ask yourself in developing themes. In phase four we began the process of reviewing and refining the themes, which is a significant step given criticism about confusing codes and themes (Braun and Clarke Citation2021b). This involved further merging and ensuring that our candidate themes were distinctive and perhaps even contradictory to other themes (Byrne Citation2022) and that each theme we constructed had a centralising concept, with further subthemes where necessary. The process concluded when we had constructed two themes around (1) heightened visibility and (2) blending in, with related subthemes as illustrated in and .

Heightened visibility

This theme attempts to explain the contradiction that under popular feminism, women are put forward to be visible in their working environment in sports media, and particularly in the broadcasting realm. Superficially, media organisations appear to paint an equitable picture in giving women prominent roles, but this was not felt by the participants. All women spoke of being very obviously in the minority in the press box (Nora, Emma) and in print media (Andrea, Olivia, Mia) while Isabelle, Mia and Olivia said they were the only women in their workplace. Emma said:

I still walk into a press room as the only woman, and I just see a sea of male heads turn and look at me and I just feel deeply uncomfortable because I’m the other…I walk in, and I just feel eyes on me because I am a woman and I am different and I am the other.

Unwanted attention

Women in broadcasting experienced unwanted attention mostly from men they did not know, some of which included social media invites or queries on their relationship status. Nora commented: ‘I found that when I started working in sports media, I was getting all these invites from randomers and weirdos’. Andrea said, ‘Only a couple years ago, I was in [stadium] and you know, walk into the press box and [one] man like ‘is she married single or available?’ …you get that sort of stuff all the time’. While much of this took place via online media, there were instances where the women drew unwanted attention at sports events:

If I walk out of the [sports event] in [city]…and people are drunk because they’ve been there all day and then they see you and…it’s just like a moth to a flame. Like you’re dying to get the back door. And like, you’re very mindful that you’re a girl and you’re alone…. that’s a part of our life that’s not getting any better, I’m afraid. (Alex)

I come off air and had people kind of commenting on my body, you know, I’ve had people talk about it, direct message me about my breasts, and people calling me ugly…so whenever I’d be on [television], you get more kind of followers in the instant afterwards…and they’re all men and there are certain type of male accounts and it’s just really weird and creepy.

I was at a [sports event] years ago…I was filming, I was kind of on my own with the camera. I was walking around the ground kind of taking some images while the match was ongoing. And I had a stand full of [sports] fans chant at me, ‘Get your ****’ out for the lads.

She also mentioned that ‘a lot of the comments will be from them saying “love you or you look great” ‘, while she feels ‘deeply uncomfortable when people get in touch with me and [say] “you’re beautiful”’. Here, Emma’s body has been judged and scrutinised, and as seen in the ‘blending in’ theme below this experience influences and shapes her ongoing regulation and control of her body and visible self.

Standing out

This subtheme explains how the women experience heightened visibility as a result of being in the minority, or as Emma termed it earlier, ‘I am different, and I am the other’:

I’m still turning up to a lot of events as the only woman. So, I am sitting there at the [sports event], as the only woman. And I was doing like a report or whatever and update and I put the mic down and I kind of just turned my head around and, and I saw two guys just pointing at me and laughing. And it was just like, ‘is this really happening?’

I was at a [sports event] a couple of weeks ago for [media organisation] and there was three people behind me. And at the end of the match, they were lovely, they were like, oh, what are you doing? I told them I was working, and they were just, like, so surprised.

I went down to [stadium] to do a [final]. You had to knock at the door in there to get up to the press box, so I get to the door and a young-ish guy answered the door and I showed him my pass…I said I want to go to the press box and…this is only around ten years ago. He looks at me and said, ‘Are you singing the anthem?’

They told me they’ve been out at [sports events] and they’ve, you know, turned up and they’ve arrived to the media press door and they get told, ‘oh no, no, no, you’re at the wrong place and you know the, hospitality is down there’, thinking they are waitresses or working anywhere but in media. And they’ve had people come up to them then when they’ve been in the press room and ask them, ‘can I have a cup of tea?’

Brand expectations

Some of the participants alluded to the importance of presentation and branding in their work, thereby conveying neoliberal aspects or economic discourses related to the self and the individual. Andrea said, ‘your brand is important…how you’re presenting yourself is important’ and she called the obligation to promote the work that she does on radio ‘a big part of the job’. Isabelle said, ‘you have to have people kind of liking you in order to be a bit more successful’. These quotes detail a certain level of acceptance of this aspect of their work in sports media. Further, while they didn’t explicitly say it, some of the participants felt the burden of responsibility for managing their visibility and self-promotion. Nora said, ‘you are probably pushing yourself out there…better for you to be known…you want them to like you for who you are and not what they want you to be’. Alex said, ‘I do think it’s relevant to be current on a platform such as Twitter because it does give you a voice when you need it and like not everybody is on TV and I’m not on TV all the time, so there are matters where I need to use that for my voice’. Mia and Olivia, who both have a wealth of experience in print media, spoke critically about this aspect of working in sports media. Mia condemned the ‘focus on women and how they look’, while Olivia said:

I think it’s distracting. You know, there’s a visual thing, they don’t listen to what you’re saying sometimes on TV because they’re too busy looking… you’re judged on how you look all the time…Again, not something I think that applies to men.

Blending in

Given the culture of popular misogyny that exists in reaction to visibility that women in sports media experience, there is some censorship, management and regulation of their bodies and voices, in terms of how they dress and what they say. The women often stated their preference to ‘blend in’ whereby they (a) police their appearance or remove or play down their gender, and (b) censor their public-facing commentary, opinions, and responses on social media in an attempt to deflect attention away from themselves.

Policing appearances

Some of the participants felt the expectation of ensuring they managed their bodies and appearances, particularly with regard to television appearances. Alex gets her clothes sponsored by a clothing line and said, ‘I feel like I can’t wear the same outfit twice within 12 months’. Andrea commented, ‘I suppose I take my appearance quite seriously as well in terms of going to the gym, and I mean only on the telly now, like I had to make sure my hair is done and all that sort of stuff like that’. While neither Andrea nor Alex commented on negativity associated with managing their appearance, Emma spoke about the pressures she is aware of on women television presenters to appear a particular way:

One person was told she would never work for them because she didn’t look a certain way. And she’s been working as a sports presenter for 20 years. And another person worked there and had been given gym membership to lose weight and pictures and a look book. They were given pictures of hairstyles and told by their bosses you have to wear your hair like that, you know, certain types of makeup, certain types of clothes. They’d be bought clothes which were two sizes smaller to encourage them to lose weight.

I know you should be allowed wear whatever you want, but you don’t want to wear anything too revealing because you know that’s also opening a can of worms then, ‘oh, she’s looking for attention’ …I definitely would look after that to make sure it’s appropriate.

I didn’t want to be too sexy there, so I didn’t want to be wearing real kind of tight fit stuff…so it took me a long time to kind of find myself, I suppose…I still am really conscious because I’ve quite big breasts and I’m always really conscious of them on air…And yeah, I’m trying to kind of use clothes as a bit of a shield.

Naturally I dress in a lot of colours in work and my personal life. But in work I kind of adopted the uniform that was black and white or grey. So that I looked like everybody else in the room when I went into a press conference, so I wasn’t sticking out. And so, when I asked a question, nobody went, ‘oh, that’s a woman you know’. And I did have that. I would have had that in dressing rooms, and I famously remember a [male athlete] shouting, ‘who’s the bird?’

We wore the same coats through all the [TV events] and very dark, dark plain coats all the time and which were picked out by [television company]. I just wore the same coats all the time and there were no comments on what I wore because it was a black coat, or it was a navy coat one year or whatever and it was the best thing I ever did because none of the focus was on it and I was getting no messages or tweets on what I was wearing.

I didn’t like that I was in a job where the emphasis was on how you looked. And you know, I actually remember like being in there and make up before and getting ready to go on air and like…’so annoying, constantly having to put on makeup like, this is not why I got into this’ … my time in journalism, bloody getting my hair done and putting on makeup.

Censoring their commentary

All participants commented on the experience of ‘pile ons’ [Andrea] on social media in reaction to something they have commented on (these reactions will be further explored in a later paper). For this reason, they are very careful about what they post or comment on, and some of them have withdrawn from regular social media posting, despite earlier comments on ‘brand expectations’. Though Andrea commented on the importance of promoting her work on social media, she also said, ‘I don’t [want to] seem like an idiot on social media’ and ‘I wouldn’t leave myself open to that’. She goes further, showing how guarded she is, ‘I wouldn’t want to draw attention to myself…like I just prefer to keep everything level and kind of stay below the radar…I’d be really reluctant to give an opinion even on like a red card or anything like that’. Though Nora said that she would always back her own views and opinions, in relation to posting on social media she said, ‘I probably have been a lot safer[sic] on social media when it comes to putting things up’. In a similar vein, Mia illustrated the dilemma she experiences between backing her own opinion but trying to manage or withhold her thoughts:

Like, you know if I feel strongly about something, I will put it out. You know, I, you know, I, I would hate that. And I would hate that I wouldn’t do something for fear of a reaction…. But at the same time, I do feel myself kind of generally pulling back just a little bit from Twitter compared to the way I used to use it.

I’m a little bit careful on Twitter. You know, I probably self-censor on Twitter. I’m you see, I’m not one for expressing very strong opinions on Twitter either…I think that when you do that, that’s where a lot of the reaction comes on Twitter…And I think that’s where a lot of it gets really toxic because then you get the anti-female stuff and ‘who do you think you are’ and all the rest.

Olivia takes a clear position in relation to managing her social media use, and what to avoid. Similar to what she does with managing her appearance, her approach is to downplay and to avoid drawing attention to herself, particularly where posts might be perceived as complaining. This could be related to her stage of career, having previously spoken up about the lack of women at work, and the lack of support for women athletes and teams, only for it to fall on deaf ears:

…and you’re banging on that door all the time. And then after a while, you know, you’re the one in the office so they’re, like, throwing their eyes up to heaven going, ‘Oh here we go again’ and you stop. You stop because you’re just too busy.

If you play it up, you’re bringing attention to yourself, and it could cause you problems. Uhm, and I felt the most useful thing I could do is keep my profile as low as possible, and do so that I could do my job better…Who is interested in me complaining? And it doesn’t further my career in any way shape or form…if you go on social media and complain about it, you’re only bringing it to people’s attention. So, I always felt no, like I was telling the story.

…going to cause a big ruckus and they’re just going to be talking about it. And to me that that wasn’t how I was going to become successful in my job. I was going to become successful in my job just by keeping my head down. I was unusual because of my gender, and when you’re in that position, you really want to keep your head down.

Conclusion

This paper outlines the contradictory experiences of women working in sports media in the UK and Ireland. On the one hand neoliberal discourses dictate expectations that these women should ‘stand out’ and develop their ‘brand’, particularly via social media, while on the other hand the heightened visibility that comes with this means that they experience marginalisation, othering and unwanted attention. Simultaneously, these women regulate and shape their bodies, voices and overall visibility in an effort to ‘blend in’ and avoid drawing attention to themselves. As seen in Kitching and Sheehan (Citation2023), threading through this data is a narrative of control, which it appears women must use in order to manage their wellbeing and online identities.

This paper sheds light on the roles of sports journalists in an era of new media and online visibility. Aligning with the neoliberal principles of individualism, self-entrepreneurialism, economic success and new market growth, most of the participants supported or accepted ‘branding’ and being visible as part of their roles. Most of the women have complied with the ‘standing out’ element, where it is necessary that not only are they seen and heard, but that their bodies and appearances are central to this enhanced visibility, particularly for those working in television. They then protect themselves and their wellbeing by ‘blending in’. Mia and Olivia signalled some non-conformity in this regard. In Mia’s move to work in print media and Olivia’s long held role there, both women appear to lean towards the written word. One might suggest that this, along with Mia’s frustration with the focus on women’s appearances, and Olivia’s critical comments around social media and keeping a low profile, signal a rejection of neoliberal discourses around visibility. It is possible that they might also stem from a different generation of women working in sports media, who might have grown tired having been ‘banging on that door all the time’ [Olivia].

Alluded to earlier in this paper, the 20 × 20 campaign and era brought about increased visibility of women in sports media in Ireland, with a similar increase in the UK. However, our data indicate that the gender dynamics and conditions in the sports media workplace have not progressed to match this increased visibility. By giving women prominent broadcasting positions, media companies are trading in this economy of visibility under popular feminism, but it appears that these environments are neglecting the support that women need in order to negotiate the prevailing male culture at work. While some of our participants downplayed or ignored the difficulties they faced, simultaneously, there was no evidence of employers being progressive in terms of tackling the difficulties faced by these women. Further, under the conditions of their employment, contractual or otherwise, some of the women may have had little scope for complaint. Women’s deployment in sports media roles and responsibilities needs greater care, particularly as Alex described the women – in line with popular feminism – as ‘a novelty factor’ or as ‘ticking a box’. Within this space, popular feminism, and indeed popular misogyny manifest, and thus gender inequalities remain unchallenged. We hope to finish this project by exploring elements of work practices and environment along with allies or peer to peer support. Beyond this there is much scope for further examination of women journalists’ working practices including their economic dispositions, resources and the division of labour.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the seven women who were so willing to share their experiences in the sports media industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Antunovic, Dunja. 2019. “We Wouldn’t Say It to Their Faces’: Online Harassment, Women Sports Journalists, and Feminism.” Feminist Media Studies 19 (3): 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1446454.

- Antunovic, Dunja. 2022. “Social Media, Digital Technology, and Sport Media.” In Sport, Social Media, and Digital Technology, edited by Jimmy Sanderson, 9–27. Leeds, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2015. “Keynote Address: Media, Markets, Gender: Economies of Visibility in a Neoliberal Moment.” The Communication Review 18 (1): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2015.996398.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny: Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2020. “Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation.” Feminist Theory 21 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119842555.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, and Laura Portwood-Stacer. 2017. “The Traffic in Feminism: An Introduction to the Commentary and Criticism on Popular Feminism.” Feminist Media Studies 17 (5): 884–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1350517.

- Bernstein, Alina, and Edward M. Kian. 2013. “Gender and Sexualities in Sport Media.” In Routledge Handbook of Sport Communication, edited by Paul M. Pedersen, 319–327. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bowes, Ali., Molly Matthews, and Jess Long. 2023. “Critical Feminism and Football Pundits.” In Critical Issues in Football: A Sociological Analysis of the Beautiful Game, edited by Will Roberts, Stuart Whigham, Alex Culvin and Daniel Parnell, 124–136. London, UK: Routledge.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London, UK: Sage.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021a. “Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21 (1): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021b. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Bruce, Toni. 2008. “Women, Sport and the Media: A Complex Terrain.” In Outstanding Research about Women and Sport in New Zealand, edited by Camilla. Obel, Toni Bruce and Shona Thompson, 51–71. Hamilton, New Zealand: Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research.

- Byrne, David. 2022. “A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Quality & Quantity 56 (3): 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y.

- Coche, Roxane. 2022. “Women Take Power: A Case Study of Ghanaian Journalists at the Russia 2018 World Cup.” Sociology of Sport Journal 39 (1): 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2020-0108.

- Cummins, R. Glenn, Monica Ortiz, and Andrea Rankine. 2019. “Elevator Eyes’ in Sports Broadcasting: Visual Objectification of Male and Female Sports Reporters.” Communication & Sport 7 (6): 789–810. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479518806168.

- Davis, Daniel Cochece, and Janielle Krawczyk. 2010. “Female Sportscaster Credibility: Has Appearance Taken Precedence?” Journal of Sports Media 5 (2): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsm.2010.0004.

- Duffy, B. E., and E. Hund. 2019. “Gendered Visibility on Social Media: Navigating Instagram’s Authenticity Bind.” International Journal of Communication 13: 20.

- DiCaro, Julie. 2022. Sidelined: Sports, Culture, and Being a Woman in America. New York, NJ: Penguin.

- Everbach, Tracy. 2018. “‘I Realized It Was about Them… Not Me’: Women Sports Journalists and Harassment.” In Mediating Misogyny: Gender, Technology and Harrassment, edited by Jacqueline R. Vickery and Tracy Everbach, 131–149. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Franks, Suzanne, and Deirdre O’Neill. 2016. “Women Reporting Sport: Still a Man’s Game?” Journalism 17 (4): 474–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914561573.

- Garcia, Christopher J., and Jennifer M. Proffitt. 2022. “Recontextualizing Barstool Sports and Misogyny in Online US Sports Media.” Communication & Sport 10 (4): 730–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795211042409.

- Hardin, M., and S. Shain. 2005. “Female Sports Journalists: Are we there Yet? ‘No’.” Newspaper Research Journal 26 (4): 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953290502600403.

- Harrison, Guy. 2019. “We Want to See You Sex It up and Be Slutty:’ Post-Feminism and Sports Media’s Appearance Double Standard.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 36 (2): 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2019.1566628.

- Harrison, Guy. 2021. On the Sidelines: Gendered Neoliberalism and the American Female Sportscaster: Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Kavanagh, Emma, Chelsea Litchfield, and Jaquelyn Osborne. 2019. “Sporting Women and Social Media: Sexualization, Misogyny, and Gender-Based Violence in Online Spaces.” International Journal of Sport Communication 12 (4): 552–572. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2019-0079.

- Kitching, Niamh, and Aoife Sheehan. 2023. “I’m Obviously a Sucker for Punishment’: Responses to Audience Interactions Used by Women Working in Sports Media.” International Journal of Sport Communication 16 (4): 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2023-0173.

- Lapchick, Richard E. 2021. The 2021 Sports Media Racial and Gender Report Card: Associated Press Sports Editors (APSE).” Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida.

- Liston, Katie, and Mary O’Connor. 2020. “Media Sport, Women and Ireland: Seeing the Wood for the Trees.” In Sport, the Media and Ireland: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Neil O’Boyle and Marcus Free, 271–307. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

- Mudrick, M., L. Burton, and C. A. Lin. 2017. “Pervasively Offside: An Examination of Sexism, Stereotypes, and Sportscaster Credibility.” Communication and Sport 5 (6): 669–688.

- Schmidt, Hans C. 2015. “Still a Boys Club’: Perspectives on Female Sports and Sports Reporters in University Student Newspapers.” Qualitative Research Reports in Communication 16 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/17459435.2015.1086422.

- Schmidt, Hans C. 2018. “Forgotten Athletes and Token Reporters: Analyzing the Gender Bias in Sports Journalism.” Atlantic Journal of Communication 26 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2018.1398014.

- Sherwood, Merryn, Matthew Nicholson, and Timothy Marjoribanks. 2018. “Women Working in Sport Media and Public Relations: No Advantage in a Male-Dominated World.” Communication Research and Practice 4 (2): 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2017.1365176.

- Thorpe, Holly, Kim Toffoletti, and Toni Bruce. 2017. “Sportswomen and Social Media: Third-Wave Feminism, Postfeminism, and Neoliberal Feminism into Conversation.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 41 (5): 359–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723517730808.

- Toffoletti, Kim, and Holly Thorpe. 2018. “Female Athletes’ Self-Representation on Social Media: A Feminist Analysis of Neoliberal Marketing Strategies in ‘Economies of Visibility.” Feminism & Psychology 28 (1): 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517726705.

- Toffoletti, Kim., Holly Thorpe, Adele Pavlidis, Rebecca Olive, and Claire Moran. 2021. “Visibility and Vulnerability on Instagram: Negotiating Safety in Women’s Online-Offline Fitness Spaces.” Leisure Sciences 45 (8): 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2021.1884628.

- Trainor, Lisa R., and Andrea Bundon. 2021. “Developing the Craft: Reflexive Accounts of Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (5): 705–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1840423.

- Velija, Philippa, and Louie Silvani. 2021. “Print Media Narratives of Bullying and Harassment at the Football Association: A Case Study of Eniola Aluko.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 45 (4): 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520958342.

- Yang, Dongdong, David J. Atkin, Michael Mudrick, and Yuren Qin. 2022. “Auditory Cuteness in Sports Podcasting: A New Lookism?” Communication & Sport 11 (5): 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221117783.