Abstract

Over the past five decades uncertainty around the value, purpose, and educational relevance of Physical Education (PE) as a school subject has been cultivated amongst key stakeholders in the education community. Within an Australian context there is a paucity of evidence to demonstrate that learning occurs in PE. The aim of this narrative systematic review was to identify and appraise what research on learning has been conducted in Australia since the year 2000 in PE. Results indicated that targeted interventions in PE improved student Fundamental Movement Skills, physical activity levels, and favourably impacted affective outcomes, and that the PE teacher and their chosen pedagogical approaches exhibit most influence on student learning. There was a lack of evidence to demonstrate that authentic learning occurs in PE, highlighting the need for PE researchers, practitioners, and teachers to design and lead empirical and robust research on learning in PE.

Introduction

What do students learn in the school subject Physical Education (PE), and how can learning in this subject be measured has been questioned (Quennerstedt et al. Citation2014), as has the assumed causal relationship between PE and lifelong participation in physical activity (Green Citation2014). Across educational literature researchers acknowledge that exploring learning pragmatically is a complex issue, but few empirical studies have investigated what students learn in PE (Quennerstedt et al. Citation2014), and how the foundations of PE support learning to occur. Over the past five decades, PE has experienced differing ideas about its value, aims, and relevance to student learning. For example, Kliziene et al. (Citation2021) acknowledged a variety of developments in PE concerning and not limited to program design and structure, teaching styles (Mosston Citation1966), curricular models (Jewett and Bain Citation1985), and pedagogical models (Haerens et al. Citation2011; Joyce and Weil Citation1972; Kirk Citation2013). Consequently, divergent perspectives have led to confusion over the purpose of PE among teachers, school leaders, practitioners, and education policy makers (Griggs and Fleet Citation2021). In his recount of the 2018 International Organisation for Physical Education in Higher Education (AIESEP) World Congress in Edinburgh, Quennerstedt (Citation2019) acknowledged that the E in PE was under attack due to issues of outsourcing, de-professionalising PE teachers, an exclusive focus on activity and heart rate levels, and global neo-liberalism shaping the future of PE. Similarly, the P in PE was also under attack as a result of academisation and an overwhelming focus on assessment leading to classroom-based lectures, directing students to becoming formulators of knowledge about movement rather than in or through movement.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific, and and Cultural Organization) Citation1978) established PE as a fundamental right for all and an essential element of lifelong education. However, it has been suggested that from its early days of conception many have focussed on what PE can do for people rather than on the development of a specific body of knowledge, in contrast to other school subjects (Kirk Citation2010; Penney Citation2008; Pill Citation2016; Siedentop Citation1972). In many respects, this situation still occurs today with championing of PE on either what it can do to enhance other subjects (PE will help academic success), or how it is purposeful for example in contributing to a public health ‘inactivity-obesity crises’ agenda (e.g. Simon Citation2018). Surrounding PE has been a paradigm tension (Bailey Citation2005) between those that see PE as a context for physical activity and education of the physical, and those that see PE as educatively purposeful and while necessarily involving physical activity. Physical activity in itself is not sufficient to justify PE as a subject worthy to pursue during curriculum time (Macfadyen and Bailey Citation2002; Penney and Chandler Citation2000; Pill Citation2012). At an international level, research of 135 studies using learning interventions in PE revealed a significant effect on student psychomotor, cognitive, affective, and social learning, suggesting that PE has benefits across multiple domains (Dudley et al. Citation2022). However, in the extant literature it seems that in the naturalistic context of PE, PE teachers assume PE’s claims to influence learning across the domains, which is often not evidential in practice (Beni, Fletcher, and Ní Chróinín Citation2017; Chen et al. Citation2017; Tinning et al. Citation2001). This is because PE is often focussed on education in movement for reproduction of specified and modelled movement techniques (Kirk Citation2010; Pill Citation2016). A review of six international studies investigating the impact of increasing proportions of PE curriculum time on student learning indicated favourable outcomes for cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains, contending that the allocation of additional PE time might surpass what students achieve by dedicating that time to practicing standardised tests. Notwithstanding the findings associated with the reviews of Dudley et al. (Citation2022) and Dudley and Burden (Citation2020), currently there is a dearth of empirical research and supporting evidence to substantiate what learning occurs in PE in Australian schools.

Within the field of literature pertinent to the educational value, purpose, and learning in PE, a selection of studies present individuals’ memories and perceptions of PE post-compulsory schooling years. For example, ‘My best memory is when I was done with it’, (Ladwig, Vazou, and Ekkekakis Citation2018), ‘Most people hate PE and most drop out of physical activity’ (Griggs and Fleet Citation2021), and ‘I just remember rugby: Re-membering PE as more than sport’ (Casey and Quennerstedt Citation2015). Hayes (Citation2017) reported primary school staff and student perspectives of PE as a ‘break from learning’, highlighting an absence of structured learning opportunities, lesson intentions, and learning processes. Collectively, outcomes of these studies reflect perceptions of PE as a regurgitated and repetitive core curriculum dominated by traditional games, in some instances and mastery of skilled performance while in others an absence of educational intent, a lack of enjoyment through embarrassment, bullying, injury, social-physique anxiety, and being punished by the teacher.

The prominence of sport being what many students recalled from PE was found by Evans et al. (Citation2007) who asserted that the primary aim of sports culture in PE is to engender student’s love of sport, but worryingly, it merely guarantees development of those physically able. Quennerstedt (Citation2019) summarised the implications of the educational value, purpose, and learning in PE being at risk of: i) doing sports without education, ii) fitness instruction without education, iii) physical activity facilitation without education, iv) obesity prevention without education, v) facilitating fun and enjoyment without education, and vi) theoretical knowledge without movement. Problematically, PE may be the only opportunity for many students to engage in regular movement, physical activity, and motor skill development; but speculatively, this reality accentuates the opportunity for PE teachers to encourage lifelong participation and learning about the significance of this (McMaster Citation2019). According to Griggs and Fleet (Citation2021) and Green (Citation2014), it is unclear whether PE as a subject, and the teaching of it, is achieving the foundation, direction, and motivation to inspire lifelong participation in movement. Against this background, it is asserted that PE teachers play a critical role in creating and establishing movement experiences, providing high quality instruction and communication of information, and in the design and delivery of learning opportunities for all students (O’Connor Citation2019).

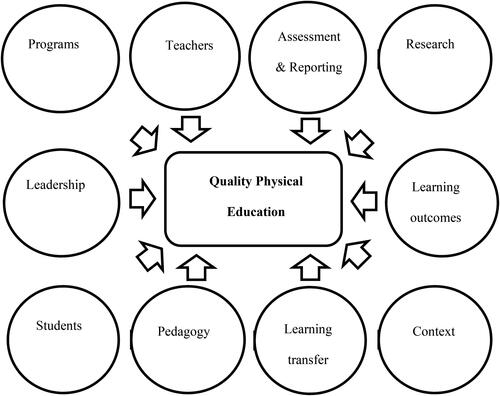

In 2015, The United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) produced guidelines for policymakers for Quality PE (QPE: UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific, and and Cultural Organization) Citation2015). Evidence exists to suggest that the quality of teaching is directly linked to student learning and associated outcomes (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2020; Polymeropoulou and Lazaridou Citation2022), subsequently a focus of this narrative is to advance teacher knowledge that provides a comprehensive conceptualisation of eminent pedagogy through a shared set of concepts, language, and descriptors (Gore Citation2021). In Australia, states and territories generally have a quality teaching or teaching for effective learning framework to direct teacher pedagogy independent of subject area taught (Williams and Pill Citation2019). Light, Curry, and Mooney (Citation2014) and Pill (Citation2004, Citation2011, Citation2016) showed that these frameworks can provide meaning that is context specific to QPE. However, QPE is multi-dimensional encapsulating curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, environment and experience (Pill Citation2004; Penney et al. Citation2009: ).

Figure 1. Key components of QPE as curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, environment, and experience (adapted from Pill Citation2004; Penney et al. Citation2009).

Learning in PE

Broadly, learning is often conceived as a change in behaviour, or as changes in the mechanisms that enable behaviour. Here, learning is defined as ‘a relatively permanent change in behaviour that occurs as a result of practice, or as a result of experience’ (Kimble Citation1961, 1). Experience is strongly linked to the concept of learning in that it is the source of ‘what’ is learnt, but not all experiences result in learning (Barron et al. Citation2015). Typically, PE seeks to promote learning across multiple domains (e.g. physical, social, emotional, and cognitive: Griggs and Fleet Citation2021; Metzler Citation2017; UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific, and and Cultural Organization) Citation2015) or developmental channels (Mosston and Ashworth Citation2008). Our study focus is the Australian context, and the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education (AC:HPE; Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority: ACARA, Citation2014) which incorporates Arnold’s (Citation1979) framework as a central proposition, founded upon: i) movement being central to HPE; ii) movement is content and a medium for learning; iii) movement competence should be acquired across a range of physical activities; and iv) forms of movement have value beyond health (Macdonald Citation2013). Arnold (Citation1979) expressed this as education in, through, and about movement, a philosophy and curriculum framework through which a holistic understanding of PE is articulated (Brown and Penney Citation2013).

Significance of this study

The aim of this narrative systematic review was to identify and appraise what research on learning has been conducted in Australia since 2000 in the subject referred to as PE. We accept Siedentop’s (Citation1972) claim that PE does not only specifically, or always happen in the subject Physical Education, as purposed, designed and enacted in certain ways. We note that community sport, physical activity, and recreation settings can also be contexts in which PE occurs. To this end, we distinguish between the subject Physical Education (noun), a process (physical education), and an outcome of becoming physically educated. The insights from this review are important in providing precis of what research outcomes from learning in PE exist within the field, how this research has been conducted, and the implications of research findings relevant to the identity, purpose, and future of the subject.

Method

Protocol and registration

The present study is a systematic review. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42022367949) and was directed by the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. Citation2021).

Search strategy

Studies conducted on learning in PE in Australia since the year 2000 were included in the systematic review. Searches of SportDiscus, PsycInfo, Medline, Web of Science, and ERIC electronic databases commenced in November 2021, with the final searching strategy performed in March 2024. Reference lists of relevant studies were manually searched to identify other possible studies.

The search strategy was conducted through CovidenceTM screening and data extraction software (2022) by using different terms related to the population, behaviour, environment, intervention, combined and adapted to the databases through the principal keywords; (i)‘physical education’; (ii) ‘learning’; (iii) ‘student’, ‘children’; (iv) ‘student learning’, ‘student outcomes’; (v) ‘school’, ‘primary school’, ‘high school’, ‘secondary school’; and (vi) ‘Australia’.

Study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to identify eligible studies. Inclusion criteria for the studies were: (a) addresses student learning or student learning outcomes, (b) is based in Australia or includes Australian populations, (c) incorporates school physical education, (d) has full-text availability, (e) data driven using empirical research methods, (f) published from the start of the millennium (2000 onwards), and (g) documented in the English language. The decision to commence the search from the year 2000 was framed upon previous research on the rise and fall of Australian physical activity between 1996 − 2006 (Bellew et al. Citation2008), recognition of the new millennium posing a change of goals for physical education nationally (Taggart and Goodwin Citation2000), and the 2000 Olympics being hosted in Australia. Inclusion criteria were centred on studies addressing student learning, specifically how learning occurred, what contributed to learning, and through what means students learned. Due to the intricately linked nature of learning and assessment, studies focusing on assessment posed a nuanced challenge. These were included only if the assessment was utilised as a means to measure learning and was supported by data evidencing student learning outcomes.

Exclusion criteria for the studies were: (a) Included populations that did not directly involve school students; (b) Involved school curriculum learning outside of physical education; and (c) Reported on sport or physical activity conducted outside of structured physical education curriculum time.

Data extraction

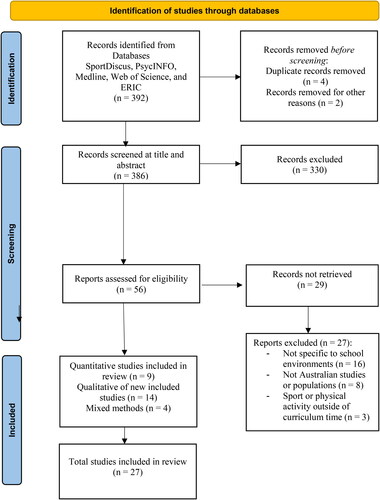

Four researchers (CM, SP, JW, and CI) equally screened titles and abstracts generated by the CovidenceTM screening and data extraction software (2022). Any duplicates were then removed. Screening was conducted for inclusion and exclusion based upon the study selection criteria and recognition of principal keywords for the present review. Conflicts or discrepancies at title and abstract stage were resolved by reaching consensus at an online meeting between the four researchers. Articles that were not within the scope of the review were excluded, eligible articles were examined at full-text ().

For each study meeting the inclusion criteria the following data were extracted: 1) year of publication; 2) author names; 3) country of study; 4) participant demographics (number, age, population); 5) study protocol; 6) measured construct; 7) measurement instruments; and 8) outcomes and results. Reasons for studies being excluded were recorded. To ensure that inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied consistently at the full-text screening stage, Group A was formed by two researchers (SP and JW) who screened 50 per cent each respectively, and Group B was formed by two researchers (CM and CI) who screened the remaining 50 per cent each respectively. Conflicts or discrepancies at full-text screening stage were resolved by reaching consensus at two respective online meetings involving Group A and one member of Group B, and involving Group B and one member of Group A. Prior to analysis a final review of all articles was conducted by CM for validity and confirmation of eligibility.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of all quantitative studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (CM and CI) using the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD; Sirriyeh et al. Citation2012). The QATSDD consists of 16 criteria which are rated on a four-point scale, resulting in a subsequent score for each study. Conflicts or discrepancies at quality assessment stage were resolved by reaching consensus at an online meeting between the two reviewers. The QATSDD has shown consistently to be ineffective and therefore not recommended to not be used for qualitative research review (Smith and McGannon Citation2018). The methodological quality of all qualitative studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (SP and JW) using the guidelines outlined by Stenfors, Kajamaa, and Bennett (Citation2020) to evaluate trustworthiness of qualitative research. To assess the depth, richness, and appropriateness of qualitative data and its analysis as evidence to address a research question these guidelines specify five criteria: credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and reflexivity. Three reviewers (SP, JW, CM) formulated a three-point scale rating system that was used to score the five criteria for each study. Conflicts or discrepancies at quality assessment stage were resolved by reaching consensus at an online meeting between the two reviewers.

The reviewers (CM, CI, SP, JW) independently graded the level of evidence each study stipulated using the level of evidence instrument designed by Smith et al. (Citation2018) and modified by Goodyear et al. (Citation2021). The criteria for each level of evidence is reported in .

Table 1. Criteria for the assessment of level of evidence.

Data synthesis and analysis

The study designs, variables, and outcome measures for what research has been completed in PE in Australia within the study scope varied considerably. Due to a restricted capacity to pool data from the included studies and subsequently limit suitability for statistical analysis, a meta-analysis was not possible. Against this background a narrative synthesis approach was implemented to systematically review the results of each study, emphasise key characteristics, understand differences and similarities, and overall outcomes (Goodyear et al. Citation2021; Ryan Citation2013). Findings from each quantitative and qualitative study were described to provide evidence of: i) features of each study, and ii) outcomes of each study. Relationships were then qualitatively examined within studies to explore reasons for differences in direction, and between studies to detect patterns based on differences in population and study characteristics.

Results

Description of studies

Twenty-seven manuscripts were reviewed and are summarised by author and year, participant demographics, research method, study protocol, instrument, and outcomes in . Six studies were randomised controlled trials, seven were a combination of non-randomised quantitative and mixed-methods studies, and 14 studies were qualitative. Thirteen manuscripts reported on data collected from school students (between school years five and year 12), ten reported on data from PE teachers, two reported on data from Year 11/12 PE curriculum, and two reported on data from Victorian Certificate of Education PE (VCEPE) examinations. Studies which involved interventions that were delivered in school PE lessons were implemented between five and 33 weeks in duration, and studies that incorporated PE professional learning for teachers were implemented for seven weeks.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

The level and quality of evidence was determined using a modified version of the strength of evidence matrix (Goodyear et al. Citation2021), reported in . Strength of evidence outcomes reflecting strong evidence-base represented sufficient level of high-quality evidence (six of 27). Strength of evidence outcomes reflecting a moderate evidence-base (five of 27), and low-quality studies where there was insufficient evidence to make definitive claims about study variables investigated and measured (16 of 27). There was considerable heterogeneity across the studies relevant to learning in PE and both the breadth and depth in which study variables were investigated and measured.

Table 3. Level and quality of evidence of included studies.

How is learning conceptualised?

Across each of the 27 studies there was no definition or specific explanation of learning. Conceptually, learning was identified through terminology such as: producing better or improved outcomes (1), increasing student learning and positively impacting long-term physical activity (2), examining learning outcomes (3), enjoyment and affect (5, 6), student learning and motivation (7) and an inquiry-based approach to enhance connectedness between learning in PE and student lives beyond schools (12). Arnold’s (Citation1979) three dimensions of education in, through, and about movement formulated the basis for curriculum intentions in two studies (4, 8). Studies (9-11) utilising a Professional Learning for Understanding Games Education (PLUNGE) intervention were framed upon the theoretical promotion of learning grounded in achievement goal theory (Nicholls Citation1984), and incorporated instructional, environmental, and motivational components to facilitate student outcomes. Study (16) utilised a Physical Education Physical Literacy (PEPL) intervention based on the objectives of improving school climate relevant to physical literacy, improving the delivery and frequency of PE, promoting schoolyard physical activity, and creating links between school and community-based organisations. Pedagogic practices using Bernstein’s theory of social reproduction of pedagogic discourse was adopted to underpin instructional and regulative discourses to what and how students learn (17). Relatedness-supportive behaviours using the self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci Citation2000) to gauge impact on student learning outcomes (14), teacher effectiveness through psychosocial, pedagogical, and feedback outcomes (19), teacher differentiation relevant to student readiness and interest (18), and teaching styles exhibited to meet syllabus objectives related to higher-order thinking skills (15) encompassed general reference to student learning.

Studies focused upon Senior Secondary PE identified the achievement of learning specific to performance in assessment (13, 23, 24), highlighting outcomes such as: skills for physical activity, self-management and interpersonal skills, knowledge and understanding of movement and conditioning, knowledge and understanding of sport psychology, bodies in motion, sports coaching and physical activity lifestyles, physical activity participation and physiological performance, and enhancing performance. Whittle and colleagues utilised the social ecological model (Sallis, Owen, and Fisher Citation2008) to position student academic achievement, specifically how student learning and academic achievement were influenced by multiple factors (25, 26). An international review of examinable Senior Secondary curriculum (including six Australian States and one Territory) emphasised knowledge and understanding of content, development of higher order thinking skills (analyse, evaluate), critical and creative skills including problem-solving, research and investigative skills, affective outcomes such as leadership, communication, and cooperation, ICT, development of lifelong health and wellbeing, and performance in physical skills (22).

How is student learning measured?

The most common methods for data collection were through individual semi-structured interviews (2, 3, 4, 5, 12, 17, 18, 19) and focus groups interviews (13, 14, 16, 25, 26, 27). The variables relevant to student learning investigated through these two methods across these studies included the impact of: teaching styles and teacher effectiveness on student learning, inquiry-based approaches on student experiences, assessment methods on student learning, the subject Physical Recreation on student motivation and post-school options. Also, teacher perceptions of what quality PE is, and impact of teacher behaviours relevant to student relatedness, support, and learning outcomes. Questionnaire (1, 10, 16, 19, 20) and survey (3, 9, 13, 16, 21) methods were used to obtain perceptions of models-based practice towards student learning, sense of self-efficacy, sporting competence, PE enjoyment, physical abilities, opinions of digital assessments and examinations, attitudes towards PE, perceptions of autonomy support and the learning climate. Class observations (4, 5, 10, 11, 15, 17, 18, 19) were used to inform teachers’ pedagogic practices, teaching styles, differentiation capacity, student performance of Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS) and sport-specific skills, and both active and non-active learning time. Case study method (4, 17) was incorporated to examine expressions of Arnold’s (Citation1979) three dimensions in teacher’s interpretations of curriculum, and to explore the impact of community role models to re-engage students in PE.

Study (5) utilised a knowledge skill test and student self-assessment at the beginning and conclusion of a rugby unit to measure student learning, and Study (6) adopted the Team Sport Assessment Procedure (López-Pastor et al. Citation2013) to measure tactical understanding, American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD: 1984) basketball skill test, and Football Federation Australia (Berger Citation2013) soccer skill test at pre-and post-test. Study (9, 10) incorporated the Test of Gross Motor Development (TGMD-2; Ulrich Citation2000) to measure a range of FMS, pedometers to measure in-class physical activity (9), and the System for Observation of Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT; Pope et al. Citation2002) to measure physical activity levels of selected students, lesson context, and teacher behaviour every 20 s during lessons (10). Study (19) used the Games Performance Assessment Instrument (GPAI; Oslin, Mitchell, and Griffin Citation1998) to measure soccer performance, accelerometers to determine student physical activity levels, and the Active Learning Time-Physical Education instrument (ALT-PE; Sidentop, Tousignant, and Parker Citation1982) to categorise the representative behaviours interim, waiting, off-task, on-task, and cognitive during ten consecutive PE lessons.

Evidence of student learning

Studies (9, 10) reported that the PLUNGE intervention contributed to a significant treatment effect in student FMS object control (throw and catch), in-class physical activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, game play abilities of decision-making, support and skill performance. In addition, through a game-sense approach, generalist primary teachers in the intervention group demonstrated significant beneficial treatments for teaching quality (intellectual quality, quality learning environment, significance of learning experience) that contributed to students improving game-play outcomes, in-class physical activity, and FMS (11). A PEPL intervention contributed to improvements in object control skills, increases in confidence and motivation to be physically active, and moderate evidence of enhanced moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during school time (16). A peer teaching intervention framed upon a game-based approach led to significantly improved in-game motor skills and active learning time, with peer teachers providing greater levels of feedback and structured learning time (19). A needs-supportive approach to teaching including strategies: i) explaining relevance, ii) providing choice, and iii) complete free choice to benefit student motivation, revealed that each approach was beneficial for lesson success, student motivation, physical activity, and learning. Explaining relevance was perceived as the most effective strategy for student enjoyment, motivation, and learning (2).

Several studies reported both student and teacher perceptions of pedagogical practice as methods to demonstrate evidence of learning. Study (12) enabled student involvement in the development of the unit, finding that students yielded enjoyment from the ownership and shared responsibility afforded, but that knowledge constructed during and after the unit remained largely superficial and individualistic. The Sport Education model was viewed as a pedagogical approach that enhanced students’ attitudes towards PE, encouraged interaction and cooperation, promoted inclusivity, improved personal and social skills, encouraged a sense of belonging and responsibility, facilitated more opportunities for assessment, allowed for student decision-making and tactical development, and increased both student motivation and learning (1, 5, 7); with constraints of the model being challenges with accountability and responsibility, social competency, cultural dilemmas, and teacher preparation (7). An indirect approach to teaching (Game Sense approach: den Duyn Citation1997) produced higher levels of tactical understanding and enjoyment levels in basketball and soccer, whereas a direct approach (skill acquisition) led to better FMS performance (6). Study (15) reported that only five of eleven teaching styles were observed in 27 Senior PE lessons, thus effectively covering syllabus objectives that require evaluative learning to produce new knowledge was highly improbable.

Studies investigating Senior Secondary PE Victorian Certificate of Education (VCEPE) examination scores in years 2011 and 2012 suggested that teachers train students for written questions and indicated that students had a superficial awareness of Arnold’s three dimensions of education, demonstrating limited capacity to link knowledge and understanding across four key subject areas (23, 24). Similarly, study (4) identified that a written examination privileges theoretical and propositional knowledge over practical knowledge and understanding, subsequently not aligning with the desired intentions of Arnold’s dimensions. In contrast, digital forms of assessment designed to maximise opportunities to cater for students’ varied knowledge, skills, and understandings to be demonstrated were perceived by students to be authentic, meaningful, and linked subject practical and theoretical components effectively (13). Study (3) reported that Year 11 and 12 students selected the subject Physical Recreation based upon minimal academic requirements, that the unit does little in preparing students for the world of work, and that the narrow competencies offered led students to concentrate more on doing rather than thinking and learning.

What influences student learning?

In asking PE teachers what quality teaching means and how understanding of quality PE influences their pedagogical constructs, teachers identified terms such as student-centred, physical, health, lifelong, fitness, inclusive, making connections, engagement, motivation, teacher involvement, fun, passion, and enthusiasm. The term sport featured prominently, but there was a lack of agreement regarding a common definition of quality PE, and limited use of research-based frameworks for informing teacher perspectives (27). Study (14) identified a range of teacher-specific behaviours that students deemed to be relatedness supportive and associated with student outcomes, highlighting teacher communication through individual conversation, in-class social support through task-related support, and teacher attentiveness/awareness (perceive, recognise, noticing class events, and emotional cues). In addition, the behaviours of teacher interest, friendliness, being a motivator, providing positive feedback and encouragement, facilitating teamwork and cooperation, and showing care influenced student outcomes. Study (18) acknowledged the goal of differentiation is to maximise student growth and provide optimal growth for all, but within an aquatic environment reported that PE teachers found it difficult to achieve differentiation and assess pragmatically despite planned outcomes and content to facilitate this. Study (25) adopted a social ecological model to investigate teacher perceptions linking teacher effectiveness to student success and student achievement, and across individual and social levels teachers highlighted student-teacher relationships, teacher availability outside of class time, passion and enthusiasm for PE, content knowledge, creating high expectations for students, and selecting appropriate teaching methods for students. Similarly, study (21) where PE teachers reported on their sense of self-efficacy indicated confidence in content taught engaged students in their learning, emphasising efficacious management of student behaviour, use of instructional strategies, and using a variety of pedagogical approaches such as direct instruction, student-centred learning, peer-teaching, and cooperative learning. Study (17) recognised the importance of creating a supportive environment to create connectedness, role modelling, and sharing of goals to promote engagement for learning in PE.

Perceptions of Senior Secondary PE students revealed that knowledge of content, verbal ability, care, enthusiasm, access to the teacher, incorporating practical activities, and sense of humour were the most important teacher-related factors to influence academic performance (20). Similarly, teacher attitudes, knowledge of students and student-teacher interactions, content knowledge, monitoring student progress, approachability, support and encouragement, passion and enthusiasm for PE and student success, and access outside of class time characterised student perceptions that influence academic achievement (26). To articulate Senior Secondary PE curriculum with Arnold’s (Citation1979) dimensions across Australian states and territories, Study (8) identified consistency across the terms movement, application, physical, performance, training, fitness, play, body (in movement), information describes, principles, content, learning, understanding assessment (about movement), and health, sports, tactics (through movement). From all states fewer concepts were identified relevant to the learning through movement dimension.

Collectively the randomised controlled trials implemented studies (9, 10), study (16), and study (19) reported performance improvements in object control skills (FMS), in-class physical activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during school time, decision-making in game play, and increases in both confidence and motivation to be physically active. Despite performance improvements one study identified no change in student perceptions of athletic competence (9), and one study identified student perceptions of sporting competence less favourable post-intervention (16).

Discussion

Absence of evidence to determine the occurrence of learning

The studies in this narrative systematic review represent a diverse selection of research aims and methodologies to provide evidence of student learning in PE. Based on the definition of learning employed for this review, ‘a relatively permanent change in behaviour that occurs as a result of practice, or as a result of experience’ (Kimble Citation1961, 1), across 27 studies there is little evidence to indicate that relatively permanent change in behaviour through practice or a result of experience does occur in PE in Australian schools. Considering that a foundational emphasis of PE is to promote, foster, and build student motivation towards lifelong participation in physical activity, the findings from this review offer limited proof to substantiate this. A small number of randomised controlled trials (9-11, 16, 19) using targeted interventions demonstrated performance improvements in FMS, increases in physical activity across the school day, and increases in both confidence and motivation, yet only one of the interventions was implemented for a period greater than seven weeks (16). Collectively, these findings bring to query a learning versus performance distinction and debate, which according to Soderstrom and Bjork (Citation2015), can be traced back decades. According to Soderstrom and Bjork (Citation2015), empirical evidence exists showing that considerable learning can occur in the absence of any performance gains, and conversely, substantial changes in learning often do not translate into changes in performance. Previous motor learning studies have revealed that physical guidance through teaching can reduce skill performance errors, but that unguided active teacher involvement promotes better long-term retention of skills. Notwithstanding that pragmatically exploring and measuring learning is complex (Quennerstedt et al. Citation2014), and the inherent challenges associated with conducting action research in school environments, there is a need for more randomised controlled trials in PE which are longitudinal cohort in design (Barrett and Noble Citation2019), and include repeated time point measures (Schober and Vetter Citation2018). Incorporating such methods would facilitate the emergence and possible maintenance of any permanent change in behaviour, and potentially establish a platform for the advent of patterns or trends relevant to student learning. Therefore, this review supports the views expressed by Pill (Citation2012) of a mismatch between rhetoric and reality in the dominant ideologies and pedagogy that underpin teaching in PE, and Alexander, Taggart, and Medland (Citation1993) who called for a new approach to teaching to create a ‘circuit breaker’ for the self-reproducing failure of Australian PE.

Attainment and realisation of learning outcomes

Despite there being an absence of evidence to determine the occurrence of learning in this review, both the attainment and realisation of several learning outcomes were discovered through multiple methods and educational models. For instance, the use of direct versus indirect approaches to learning (6), sport education model (1, 5, 7) game-based approaches (9-11), inquiry-based approach (12), peer-teaching/student-centred (19), and Sport Australia Physical Literacy Framework (16). Overall, findings from these non-traditional approaches as opposed to traditional or direct approaches to delivering PE revealed higher student tactical understanding, higher levels of enjoyment, higher sport test scores, greater improvements in self-assessment scores, greater improvements in game-play decision-making skills, increased time dedicated to structured learning, and greater provision of feedback from peer teaching. Collectively these positive outcomes connect with student learning in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains of PE (Bloom et al. Citation1956; Hoque Citation2017), and seemingly impact favourably upon student engagement and motivation towards PE. In comparison, traditional or direct approaches to teaching PE are considered teacher-centred, whereby the teacher is completely in control of all instructional decisions about content, class management, instruction, assessment, student engagement and accountability (Metzler Citation2017). Such approaches are premised upon students being expected to replicate movement patterns, and under consistent exposure lead students to the recruitment of cognitive processes only when information is received from the teacher, thus incurring low cognitive engagement (Griggs and Fleet Citation2021; McMorris Citation1998). Findings from the current review suggest that a traditional approach may be more effective in the learning and development of FMS and in the early stages of skill acquisition, which is supported by previous research (Bessa et al. Citation2021, Metzler Citation2017). Contrastingly, the emphasis upon indirect and models-based approaches observed allows a more student-centred learning focus and progression towards a broader and deeper range of learning outcomes (Casey and MacPhail Citation2018; Kirk Citation2013). Furthermore, it is plausible that these approaches are used increasingly in PE to shift the subject away from a perceived ‘sport culture’ and dominance of sport provided in PE within many schools (Hernando-Garijo et al. Citation2021). It must be noted that the findings from this review relating to learning outcomes from multiple educational models are generated primarily through self-report methods (survey, questionnaire, interviews). These methods provide benefit in terms of participant access, being time and cost efficient, but have limitations relevant to the reliability of information about people’s beliefs, misrepresentation of thoughts, ambiguity, and being contextually unique, thus influencing the capacity to make generalisations (Gaete, Gómez, and Benavides Citation2017).

Quality of teaching

Quality of teaching was found in the corpus to be directly linked to student learning and associated outcomes (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2020; Polymeropoulou and Lazaridou Citation2022), with components of the QPE as curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, environment, and experience framework (adapted from Pill Citation2004; Penney et al. Citation2009) apparent within the studies in this review. Across numerous studies (2, 13, 14, 18, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27) student and teacher perceptions of preferred teaching styles, teacher behaviours that are relatedness supportive and connect with the achievement of student outcomes, teacher capacity to differentiate learning, teacher-related factors that impact student learning, digital forms of assessment, and what quality PE means, were reported. Mutually, the findings from these studies represent a compendium of characteristics and behaviours that both students and teachers conveyed as ideal in regard to the QPE components pedagogy, learning transfer, students, teachers, learning outcomes, context, and assessment.

What the studies in the corpus do not offer are research designs and subsequent findings that are empirical, authentic, pragmatic, or pertinent towards providing evidence of student learning. Rather, the studies in this review describe teacher-related factors and behaviours that influence student learning, but are impeded by small and convenience-based samples, basing conclusions on data collected at one point in time, and use of self-report measures. Accordingly, drawing concrete conclusions and making population-level generalisations from these findings is difficult, as is translating these findings into functional, meaningful and measurable real-world practice, particularly when examining student learning in PE. Classroom observations are a valuable approach to evaluate and improve teaching, acknowledging the process allows for understanding of how teachers teach within a realistic context, and being a staple of research on teaching for nearly a century (Martinez, Taut, and Schaaf Citation2016). In the current review, four studies (4, 15, 17, 18) utilised classroom observations to evaluate teaching styles, pedagogical approach, and capacity to provide differentiated learning, with these observations uncovering the importance of role modelling, teachers not pertaining to the desired intentions of Arnold’s (Citation1979) dimensions in their interpretation and enactment, teachers relied on a small number of teaching styles to deliver syllabus learning, and that teachers were able to differentiate the content and how this was delivered, but demonstrated infrequent differentiation for assessment. Against this background, research designs that incorporate multiple forms of data collection (Camerino, Castaner, and Anguera Citation2012), adopt multiple time point measures (Schober and Vetter Citation2018), and seek populations that are more heterogeneous (Andrade Citation2021) may yield outcomes that provide increased robustness, validity, reliability, and practical applicability.

Arnold’s (Citation1979) three dimensions were mentioned in only two of the studies reviewed. One of these was a document analysis which explored the Senior Secondary PE syllabi across Australian states and territories (8), highlighting concepts and themes consistent within each dimension, but providing no origins for student learning. The second study reported how Arnold’s dimensions were expressed in teacher’s interpretation and enactment of the VCEPE (4), with findings suggesting a juxtaposition between subject content and how it was actually delivered, recognising that meaningful connection of physical activity experiences was missing from theoretical knowledge and elements of the subject. Moreover, the expression of Arnold’s dimensions was limited, bringing to question the prioritising of the VCEPE examination and consequently debate surrounding the place of physical activity in an examinable ‘academic’ subject. Considering that Arnold’s framework forms a central proposition within the 2014 AC:HPE, it is surprising that there is scant research exploring student learning in PE relevant to PE curriculum. Another study (22) presented an international document analysis of 15 Senior Secondary PE courses (including all Australian states and territories) which sought to clarify what is worthwhile content knowledge, the status of PE as an academic subject in relation to other mainstream subjects, the academisation of PE, and the privileging of scientific knowledge over practical knowledge. Findings from this analysis were largely consistent across subject aims, objectives, theoretical foundations, and content, with ten of the 15 syllabi including an examination, but only six of the 15 assessed physical performance of students. According to Hay and Penney (Citation2009), assessment can be viewed as a process that can promote student learning through movement and integrating concepts and contexts in real-world settings, but with increased use of high-stakes examinations, creating and executing an integrated teaching approach has shown to be problematic (Thorburn and Collins Citation2006). Two studies in the current review (23, 24) presented document analysis of VCEPE examinations across two cohort years, with outcomes signifying that this approach to assessment functions chiefly to determine student achievement through written tasks, as opposed to practice informing student learning in, through, and about movement (Arnold Citation1979). Therefore, this evidence implies that classroom theoretical experiences and examinations provide accountability for schools, cultivate low-order thinking through assessing knowledge and theoretical skills, but do not aid higher-order thinking by providing opportunities to apply, analyse, create, and evaluate.

Research on student learning in PE in Australia is negligible

The culmination of findings from this review demonstrate that between the years 2000 and 2024, research on learning in PE Australia is negligible. In considering the questions raised by Quennerstedt et al. (Citation2014) - what do students learn in the school subject PE, and, how can learning in this subject be investigated? this study provides limited evidence for the benefit of targeted interventions involving FMS, physical activity levels, enjoyment and motivation towards PE. Beyond this, the influence of the PE teacher was the field most explored within the corpus, yet due to a lack of rigorous and experiential study designs it is difficult to articulate how teacher influence directly effects student learning. An important outcome from one study (27) inferred that a sample of PE teachers with between one and 39 years of experience did not share commonality in how they defined QPE and did not portray QPE reflective of how it features within the AC:HPE by the work of Arnold (Citation1979). This provides rationale for why divergent perspectives have led to confusion over the purpose of PE among teachers, school leaders, practitioners, education policy makers (Griggs and Fleet Citation2021), students (Hayes Citation2017), and the credibility of the subject.

This narrative review does have limitations. There was diversity within study designs including randomised controlled trials, interventions, non-randomised, observational, case study, document analysis, and qualitative, therefore the range of study aims, populations, and results exhibited considerable variability. Of the 27 studies included, less than a quarter of these were assessed to be high quality, with insufficient evidence relevant to both the identification and appraisal of student learning in PE. The use of several self-report methods to obtain data directly contributed to 16 of the 27 studies offering low quality evidence of student learning. These limitations emphasise the need for studies to adopt designs which foster high quality evidence, such as randomised controlled trials, mixed methods, longitudinal cohort, and incorporate the measurement of student learning that aligns with relatively permanent change in behaviour as a result of practice, or as a result of experience.

Conclusion

This study presents evidence of what research on learning has been conducted in Australia since the year 2000 in the subject PE. Principally, there is an absence of authentic and reliable research to enable objective verification and substantiation of any relatively permanent change in student behaviour that occurs as a result of practice, or as a result of experience. A small number of randomised controlled intervention studies demonstrated favourable short-term outcomes for FMS, tactical approaches, and affective variables, but the majority of studies examined perceptions related to teacher influence on various student outcomes associated with their learning. When considering the purpose of PE and what students learn, the findings from this review promulgate a call to PE researchers, practitioners, and teachers in Australia to design and lead research on learning in PE. In approaching this, methodological considerations such as randomised controlled trials, repeated data collection points, and longitudinal approaches are recommended. If PE is under attack as a school subject, if confusion does exist regarding its educational value amongst a far-reaching educational community, and if validation of learning is at risk, the need for pragmatic and empirical substantiation of learning in PE is imperative.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and mentorship provided by Professor Tony Rossi from the University of Western Sydney. Throughout the developmental stages of this narrative systematic review, Tony was a comprehensive source of information, insight, and critique that assisted with both inspiration and direction for the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- ACARA (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority). 2014. Health and Physical Education Curriculum. ACARA.

- Alexander, K., A. Taggart, and A. Medland. 1993. “Try before You Buy”. Sport and Physical Activity Research Centre, Edith Cowan University.” Presented at Annual AARE Conference, Fremantle, Western Australia.

- Alexander, K., and J. Luckman. 2001. “Australian Teachers’ Perceptions and Uses of the Sport Education Curriculum Model.” European Physical Education Review 7 (3): 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X010073002.

- Andrade, C. 2021. “Understanding Statistical Noise n Research: 1. Basic Concepts.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 45 (1): 89–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176221139665.

- Arnold, P. 1979. Meaning in Movement, Sport and Physical Education. London: Heinemann.

- Bailey, R. 2005. “Evaluating the Relationship between Physical Education, Sport and Social Inclusion.” Educational Review 57 (1): 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191042000274196.

- Barrett, D., and H. Noble. 2019. “What Are Cohort Studies?” Evidence-Based Nursing 22 (4): 95–96. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103183.

- Barron, A. L., E. A. Hebets, T. A. Cleland, C. L. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Hauber, and J. R. Stevens. 2015. “Embracing Multiple Definitions of Learning.” Trends in Neurosciences 38 (7): 405–407. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscihebets/59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.008.

- Bellew, B., S. Schoeppe, F. C. Bull, and A. Bauman. 2008. “The Rise and Fall of Australian Physical Activity Policy 1996 – 2006: A National Review Framed in an International Context.” BioMed Central 5 (18): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8462-5-18.

- Beni, Stephanie, Tim Fletcher, and Déirdre Ní Chróinín. 2017. “Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature.” Quest 69 (3): 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192.

- Bennie, A., L. Peralta, S. Gibbons, D. Lubans, and R. Rosenkranz. 2017. “Physical Education Teachers’ Perceptions about the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Strategies Used to Increase Relevance and Choice for Students in Physical Education Classes.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 45 (3): 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1207059.

- Berger, H. 2013. The National Football Curriculum: The Roadmap to International Success. Football Federation Australia Official Publication.

- Bessa, C., P. Hastie, A. Ramos, and I. Mesquita. 2021. “What Actually Differs between Traditional Teaching and Sport Education Students’ Learning Outcomes. A Critical Systematic Review.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 20 (1): 110–125. https://doi.org/10.5282082/jssm.2021.110.

- Bloom, B., M. Engelhart, W. Hill, and D. Krathwohl. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. London. Longmans

- Brown, S., and D. Macdonald. 2011. “A Lost Opportunity? Vocational Education in Physical Education.” Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 16 (4): 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2010.535196.

- Brown, T., and D. Penney. 2013. “Learning in, through and about Movement in Senior Physical Education? The New Victorian Certificate of Education Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 19 (1): 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X12465508.

- Browne, T., T. Carlson, and P. Hastie. 2004. “A Comparison of Rugby Seasons Presented in Traditional and Sport Education Formats.” European Physical Education Review 10 (2): 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X04044071.

- Camerino, O., M. Castaner, and T. Anguera. 2012. Mixed Methods Research in the Movement Sciences: Case Studies in Sport, Physical Education and Dance. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Casey, A., and A. MacPhail. 2018. “Adopting a Models-Based Approach to Teaching Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (3): 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2018.1429588.

- Casey, A., and M. Quennerstedt. 2015. “I Just Remember Rugby: Re-Membering Physical Education as More than Sport.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 86 (1): 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.977430.

- Chen, A., T. Zhang, S. Wells, R. Schweighardt, and C. Ennis. 2017. “Impact of Teacher Value Orientations on Student Learning in Physical Education.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education: JTPE 36 (2): 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2016-0027.

- Darling-Hammond, L., L. Flook, C. Cook-Harvey, B. Barron, and D. Osher. 2020. “Implications for Educational Practice of the Science and Learning and Development.” Applied Developmental Science 24 (2): 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- den Duyn, N. 1997. Game Sense: Developing Thinking Players – a Presenters Guide and Workbook. Belconnen, ACT. Australian Sports Commission.

- Dudley, D., and R. Burden. 2020. “What Effect on Learning Does Increasing the Proportion of Curriculum Time Allocated to Physical Education Have? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” European Physical Education Review 26 (1): 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19830113.

- Dudley, D., E. Mackenzie, P. Van Bergen, J. Cairney, and L. Barnett. 2022. “What Drives Quality Physical Education? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Learning and Development Effects from Physical Education-Based Interventions.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 799330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.799330.

- Evans, J., E. Rich, R. Allwood, and B. Davies. 2007. Being ‘Able’ in a Performative Culture; Physical Education’s Contribution to a Healthy Interest in Sport? Rethinking Gender and Youth Sport. London. Routledge.

- Gaete, Alfredo, Viviana Gómez, and Pelayo Benavides. 2017. “The Overuse of Self-Report in the Study of Beliefs in Education: Epistemological Considerations.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 41 (3): 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1288205.

- Georgakis, S., and J. Graham. 2016. “From Comparative Education to Comparative Pedagogy: A Physical Education Case Study.” The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 15 (1): 105–115.

- Goodyear, V., B. Skinner, J. McKeever, and M. Griffiths. 2021. “The Influence of Online Physical Activity Interventions on Children and Young People’s Engagement with Physical Activity: A Systematic Review.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 28 (1): 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1953459.

- Gore, J. M. 2021. “The Quest for Better Teaching.” Oxford Review of Education 47 (1): 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1842182.

- Green, K. 2014. “Mission Impossible? Reflecting upon the Relationship between Physical Education, Youth Sport and Lifelong Participation.” Sport, Education and Society 19 (4): 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.683781.

- Griggs, G., and M. Fleet. 2021. “Most People Hate Physical Education and Lost Drop out of Physical Activity: In Search of Credible Curriculum Alternatives.” Education Sciences 11 (11): 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110701.

- Haerens, L., D. Kirk, G. Cardon, and I. De Bourdeaudhuij. 2011. “Toward the Development of a Pedagogical Model for Health-Based Physical Education.” Quest 63 (3): 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2011.10483684.

- Harvey, S., S. Pill, P. Hastie, and T. Wallhead. 2020. “Physical Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Successes, Constraints, and Possibilities Associated with Implementing the Sport Education Model.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 25 (5): 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1752650.

- Hay, P., and D. Penney. 2009. “Proposing Conditions for Assessment Efficacy in Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 15 (3): 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X09364294.

- Hayes, D. 2017. “The Love of Sport: An Investigation into the Perceptions and Experiences of Physical Education amongst Primary School Pupils.” Research Papers in Education 32 (4): 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1318807.

- Hernando-Garijo, Alejandra, David Hortigüela-Alcalá, Pedro Antonio Sánchez-Miguel, and Sixto González-Víllora. 2021. “Fundamental Pedagogical Aspects for the Implementation of Models-Based Practice in Physical Education.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (13): 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137152.

- Hoque, E. 2017. “Three Domains of Learning: Cognitive, Affective and Psychomotor.” The Journal of EFL Education & Research 2 (2): 45–52.

- Hyndman, B., and S. Pill. 2017. “The Curriculum Analysis of Senior Education in Physical Education (CASE-PE) Study.” Curriculum Perspectives 37 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-017-0020-z.

- Jewett, A., and L. Bain. 1985. The Curriculum Process in Physical Education. W Dubuque, IA: C. Brown.

- Joyce, B., and M. Weil. 1972. Models of Teaching. Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Prentice-Hall.

- Kimble, G. A. 1961. Hilgard and Marquis’ “Conditioning and Learning”. New York. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Kirk, D. 2010. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge

- Kirk, D. 2013. “Educational Value and Models-Based Practice in Physical Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (9): 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.785352.

- Kliziene, I., G. Cizauskas, S. Sipaviciene, R. Aleksandraviciene, and K. Zaicenkoviene. 2021. “Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (14): 7536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147536.

- Ladwig, Matthew A., Spyridoula Vazou, and Panteleimon Ekkekakis. 2018. “My Best Memory is When I Was Done with It: PE Memories Are Associated with Sedentary Behaviour.” Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine 3 (16): 119–129. http://doi.org/10.1249/TJX.0000000000000067.

- Light, R., C. Curry, and A. Mooney. 2014. “Game Sense as a Model for Delivering Quality Teaching in Physical Education.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 5 (1): 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2014.868291.

- López-Pastor, Víctor Manuel, David Kirk, Eloisa Lorente-Catalán, Ann MacPhail, and Doune Macdonald. 2013. “Alternative Assessment in Physical Education: A Review of International Literature.” Sport, Education and Society 18 (1): 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.713860.

- Macdonald, D. 2013. “The New Australian Health and Physical Education Curriculum: A Case of/for Gradualism in Curriculum Reform?” Australia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2013.801104.

- Macfadyen, T., and R. Bailey. 2002. Teaching Physical Education 11-18: Perspectives and Challenges. London: Continuum Books.

- Martinez, F., S. Taut, and K. Schaaf. 2016. “Classroom Observation for Evaluating and Improving Teaching: An International Perspective.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 49: 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.03.0020191-491X.

- McMaster, N. 2019. Teaching Health and Physical Education in Early Childhood and Primary Years. 1st ed. Australia. Oxford.

- McMorris, T. 1998. “Teaching Games for Understanding: Its Contribution to the Knowledge of Skill Acquisition from a Motor Learning Perspective.” European Journal of Physical Education 3 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898980030106.

- Metzler, M. 2017. Instructional Models of Physical Education. 3rd ed. New York. Routledge.

- Miller, A., E. Christensen, N. Eather, J. Sproule, L. Annis-Brown, and D. Lubans. 2015. “The PLUNGE Randomized Controlled Trial: Evaluation of a Games-Based Physical Activity Professional Learning Program in Primary School Physical Education.” Preventive Medicine 74: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.02.002.

- Miller, A., E. Christensen, N. Eather, S. Gray, J. Sproule, J. Keay, and D. Lubans. 2016. “Can Physical Education and Physical Activity Outcomes Be Developed Simultaneously Using a Game-Centred Approach?” European Physical Education Review 22 (1): 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15594548.

- Miller, A., N. Eather, S. Gray, J. Sproule, C. Williams, J. Gore, and D. Lubans. 2017. “Can Continuing Professional Development Utilizing a Game-Centred Approach Improve the Quality of Physical Education Teaching Delivered by Generalist Primary School Teachers?” European Physical Education Review 23 (2): 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16642716.

- Mosston, M. 1966. Teaching Physical Education. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

- Mosston, M., and S. Ashworth. 2008. “Teaching Physical Education, First Online Edition.” https://spectrumofteachingstyles.org/assets/files/book/Teaching_Physical_Edu_1st_Online.pdf

- Nicholls, J. G. 1984. “Achievement Motivation: Conceptions of Ability, Subjective Experience, Task Choice, and Performance.” Psychological Review 91 (3): 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328.

- O’Connor, J. 2019. “Exploring a Pedagogy for Meaning-Making in Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 25 (4): 1093–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18802286.

- O’Connor, Justen, Ruth Jeanes, and Laura Alfrey. 2016. “Authentic Inquiry-Based Learning in Health and Physical Education: A Case Study of ‘r/Evolutionary’ Practice.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 21 (2): 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2014.990368.

- Oslin, J., S. Mitchell, and L. Griffin. 1998. “The Game Performance Assessment Instrument (GPAI): Development and Preliminary Validation.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 17 (2): 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe17.2.231.

- Page, M., J. McKenzie, P. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. Hoffmann, C. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, et al. 2021. “PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplar for Supporting Systematic Reviews.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 372: N71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Penney, D. 2008. “Positioning and Defining Physical Education, Sport and Health in the Curriculum.” European Physical Education Review 4 (2): 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X9800400203.

- Penney, D., A. Jones, P. Newhouse, and A. Cambell. 2012. “Developing a Digital Assessment in Senior Secondary Physical Education.” Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 17 (4): 383–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2011.582490.

- Penney, D., and T. Chandler. 2000. “Physical Education: What Futures?” Sport, Education and Society 5 (1): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/135733200114442.

- Penney, D., R. Brooker, P. Hay, and l Gillespie. 2009. “Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment: Three Message Systems of Schooling and Dimensions of Quality Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 14 (4): 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320903217125.

- Pill, S. 2004. “Quality Learning in Physical Education.” Active & Healthy Magazine 11 (3): 13–14.

- Pill, S. 2011. “Seizing the Moment: Can Game Sense Further Inform Sport Teaching in Australian Physical Education?” PHENex Journal/Revue phenEPS 3 (1): 1–15.

- Pill, S. 2012. “Rethinking Sport Teaching on Physical Education.” PhD thesis, University of Tasmania.

- Pill, S. 2016. “Exploring the Challenges in Australian Physical Education Curricula past and Present.” Journal of Physical Education and Health: Social Perspective 5 (7): 5–18.

- Polymeropoulou, V., and A. Lazaridou. 2022. “Quality Teaching: Finding the Factors That Foster Student Performance in Junior High School Classrooms.” Education Sciences 12 (5): 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050327.

- Pope, R., K. Coleman, E. Gonzalez, F. Barron, and E. Heath. 2002. “Validity of a Revised System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT).” Pediatric Exercise Science 14 (2): 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.14.2.135.

- Quennerstedt, M. 2019. “Physical Education and the Art of Teaching: Transformative Learning and Teaching in Physical Education and Sports Pedagogy.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (6): 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1574731.

- Quennerstedt, Mikael, Claes Annerstedt, Dean Barker, Inger Karlefors, Håkan Larsson, Karin Redelius, and Marie Öhman. 2014. “What Did They Learn in School Today? A Method for Exploring Aspects of Learning in Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 20 (2): 282–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X14524864.

- Ryan, R. 2013. “Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: Data Synthesis and Analysis”. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. http://cccrg.cochrane.org

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” The American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Sallis, J. F., N. Owen, and E. Fisher. 2008. “Ecological Models of Health Behavior.” In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath, pp. 465–485. San Francisco, California. Jossey-Bass.

- Schober, P., and T. Vetter. 2018. “Repeated Measures Design and Analysis of Longitudinal Data: If at First You Do Not Succeed – Try, Try Again.” Anesthesia and Analgesia 127 (2): 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003511.

- Sidentop, D., M. Tousignant, and M. Parker. 1982. Academic Learning Time – Physical Education. 1982 revision coding manual. Ohio State University, United States of America.

- Siedentop, D. 1972. Physical Education: An Introductory Analysis. Iowa, United States of America. Wm. C. Brown & Company.

- Simon, W. E. Jr, 2018. Break a Sweat, Change Your Life: The Urgent Need for Physical Education in Schools. California, Los Angeles. AuthorHouse.

- Sirriyeh, R., R. Lawton, P. Gardner, and G. Armitage. 2012. “Reviewing Studies with Diverse Designs: The Development and Evaluation of a New Tool: Reviewing Studies with Diverse Designs.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 18 (4): 746–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x.

- Smith, B., and K. R. McGannon. 2018. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (1): 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Smith, B., N. Kirby, B. Skinner, L. Whightman, R. Lucas, and C. Foster. 2018. Physical Activity for General Health Benefits in Disabled Adults: Summary of a Rapid Evidence Review for the UK Chief Medical Officers’ Update of the Physical Activity Guidelines. England, Public Health England.

- Soderstrom, N. C., and R. A. Bjork. 2015. “Learning versus Performance: An Integrative Review.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 10 (2): 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615569000.

- Sparks, C., J. Dimmock, P. Whipp, C. Lonsdale, and B. Jackson. 2015. “Getting Connected: High School Physical Education Teacher Behaviors That Facilitate Students’ Relatedness Support Perceptions.” Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 4 (3): 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000039.

- Stenfors, Terese, Anu Kajamaa, and Deirdre Bennett. 2020. “How to …Assess the Quality of Qualitative Research.” The Clinical Teacher 17 (6): 596–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13242.

- Suesee, B., K. Edwards, S. Pill, and T. Cuddihy. 2019. “Observed Teaching Styles of Senior Physical Education Teachers in Australia.” Curriculum Perspectives 39 (1): 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-0048-8.

- Taggart, A., and S. Goodwin. 2000. Physical and Sport Education in Australia: Organisation, Placement and Related Issues. Mount Lawley, Australia: Sport and Physical Activity Research Centre (SPARC), Edith Cowan University.

- Telford, R. M., L. S. Olive, R. J. Keegan, S. Keegan, L. M. Barnett, and R. D. Telford. 2021. “Student Outcomes of Physical Education and Physical Literacy (PEPL) Approach: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial of Multicomponent Intervention to Improve Physical Literacy in Primary Schools.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 26 (1): 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1799967.

- Thorburn, M., and D. Collins. 2006. “The Effects of an Integrated Curriculum Model on Student Learning and Attainment.” European Physical Education Review 12 (1): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X06060210.

- Tinning, R., D. Macdonald, J. Wright, and C. Hickey. 2001. Becoming a Physical Education Teacher: Contemporary and Enduring Issues. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education, Australia.

- Ulrich, D. A. 2000. “Test of Gross Motor Development – 2.” Examiner’s Manual. Austin, Texas. Pro-ed.

- UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). 2015. Quality Physical Education (QPE) Guidelines for Policy-Makers. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- UNESCO (United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). 1978. Charter for Physical Education and Sport. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Whatman, S., and K. Main. 2018. “Re-Engaging ‘Youth at Risk’ of Disengaging from Schooling through Rugby League Club Partnership: Unpacking the Pedagogic Practices of the Titans Learning Centre.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (4): 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1184135.

- Whipp, P., A. Taggart, and B. Jackson, “. 2014. “Differentiation in Outcome-Focused Physical Education: Pedagogical Rhetoric and Reality.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (4): 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.754001.

- Whipp, P., B. Jackson, J. Dimmock, and J. Soh. 2015. “The Effects of Formalized and Trained Non-Reciprocal Peer Teaching on Psychosocial, Behavioural, Pedagogical and Motor Learning Outcomes in Physical Education.” Frontiers in Psychology 6: 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00149.

- Whittle, R., A. Benson, and A. Telford. 2017a. “Exploring Context Specific Teacher Efficacy in Senior Secondary (VCE) Physical Education Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 68: 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.006.

- Whittle, R., A. Benson, and A. Telford. 2017b. “Enrolment, Content and Assessment: A Review of Examinable Senior Secondary (16-19- Year Olds) Physical Education Courses: An International Perspective.” The Curriculum Journal 28 (4): 598–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2017.1318770.

- Whittle, R., A. Benson, S. Ullah, and A. Telford. 2017. “Student Performance in High-Stakes Examinations Based on Content Area in Senior Secondary (VCE) Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (6): 632–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1310831.

- Whittle, R., A. Benson, S. Ullah, and A. Telford. 2018. “Investigating the Influence of Question Type and Cognitive Process on Academic Performance in VCE Physical Education: A Secondary Data Analysis.” Educational Research and Evaluation 24 (8): 504–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2019.1612256.

- Whittle, R., A. Telford, and A. Benson. 2015. “The ‘Perfect’ Senior (VCE) Secondary Physical Education Teacher: Student Perceptions of Teacher-Related Factors That Influence Academic Performance.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40 (40): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.1.

- Whittle, R., A. Telford, and A. Benson. 2018. “Teacher’s Perceptions of How They Influence Student Academic Performance in VCE Physical Education.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43 (2): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n2.1.

- Whittle, R., A. Telford, and A. Benson. 2019. “Insights from Senior-Secondary Physical Education Students on Teacher-Related Factors They Perceive to Influence Academic Achievement.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 44 (6): 69–90. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n6.5.

- Williams, J., and S. Pill. 2019. “What Does the Term ‘Quality Physical Education’ Mean for Health and Physical Education Teachers in Australian Capital Territory Schools?” European Physical Education Review 25 (4): 1193–1210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18810714.