Abstract

Stories of body shaming in sports coaching are becoming widespread, and can intentionally, unintentionally, or inadvertently be used in different sports coaching practices. These practices do not necessarily intend to harm athletes. The aim of this paper is to explore body critical and body sensitive sport coaching practices that have the potential to be shaming, or as we call it in the title, the ‘anatomy’ of body shaming. The study used photo elicitation interviews including vignettes for data generation with 12 coaches from nine different sports. The results demonstrate that body criticality and body sensitivity function in different subtle ways and that coaches were well-aware of the potentially damaging influence that they can have on athletes. The article concludes with recommendations for further research exploring how athletes experience the most subtle and invisible ways of body critical and body sensitive practices, and how they internalize this well-intended but still potentially shaming advice.

Introduction

You need to lose weight

You need to lose x kg to ever be free from your injury

It’s normal to lose your period, it only means that you train hard enough

You are thinner now than before, good

We are gonna check our weights after Christmas and you need to pay for every kg you have gained

These are only a few of the comments I’ve heard as an athlete. Unfortunately, this kind of talk is normalized in track and I know from my own experience how big of an impact just one comment like this can have on a person. […] As an eighteen-year-old, I just wanted to do everything right to reach my goals and I started to cut out more and more food. I lost a lot of weight and got super thin. In the end I lost my period for 8 months, my body was constantly sore and I was miserable. I constantly looked at my stomach in the mirror to see how much more ‘fat’ I could get rid of. I did my worst year so far performance wise and in the end, I got injured so I had to end my season. (Instagram post by the track and field athlete Kaiza Karlén, www.expressen.se 14 April 2023)

Stories of body shaming like these are regularly published in the media, particularly by elite athletes. Body shaming is understood as the act of humiliating someone by making inappropriate or negative comments about body size, body weight, or body shape (Gilbert and Miles Citation2002; Schlüter, Kraag, and Schmidt Citation2023). Body shaming can also, if used more explicitly and repeatedly, be understood as a form of bullying (McMahon, McGannon, and Palmer Citation2022) and as a form of social aggression or emotional abuse (Willson and Kerr Citation2022) Research suggests that coaches adopt body shaming practices because they believe athletes need to be fat-free to succeed (e.g. Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2017; McMahon and Dinan-Thompson Citation2008; Willson and Kerr Citation2022). The assumption is that if athletes can attain a particular body shape, body composition, and body weight (e.g. child-like in women’s gymnastics; extremely thin in rhythmic gymnastics; slim but toned in swimming; thin and light in running), they are more likely to reach peak performance. To reach such ideal body shapes, coaches have been found to criticize athletes’ bodies, particularly female athletes’ body shape and weight, joke about young athletes’ bodies, not select athletes because of body composition (despite sufficient performance), demand extreme weight loss, and claim that weight loss would enhance performance (Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2017; Kerr, Berman, and De Souza Citation2006; McMahon, McGannon, and Palmer Citation2022; Willson and Kerr Citation2022). For the purposes of this paper, we define this criticism from coaches towards athletes’ bodies as ‘body criticality’, and the practices that they use, as ‘body critical practices’.

Coaches’ critical comments have been found to cause athletes to experience social physique anxiety, disordered eating, and unhealthy dieting (e.g. binge-eating; dietary restraint), and feelings of guilt, shame, and anxiety (Greenleaf Citation2004; Kerr, Berman, and De Souza Citation2006; Ryall Citation2019; Vani et al. Citation2021). Athletes may be distressed when coaches compare their bodies to those of others because they feel pressure to conform to body ideals (Mosewich et al. Citation2009), and as early as 1999, Thompson and Sherman (Citation1999) recommended that coaches should avoid making critical comments to and comparing the bodies of athletes.

Studies on issues related to body shaming have been conducted for some time, particularly on body image and eating/exercise disorders in athletes (e.g. Greenleaf Citation2004; Kerr, Berman, and De Souza Citation2006; McMahon, McGannon, and Palmer Citation2022; Reel et al. Citation2013; Vani et al. Citation2021; Willson and Kerr Citation2022). Findings reveal that athletes are at greater risk of developing eating disorders than non-athletes. Significantly, aesthetic sports, which have been shown to focus on appearance and leanness, entail an additional risk factor for athletes to develop an eating disorder (Krentz and Warschburger Citation2011; Torstveit, Rosenvinge, and Sundgot-Borgen Citation2008).

While critical comments about weight and the shaming of bodies can entail a broad spectrum of definitions and demarcations (see e.g. Schlüter, Kraag, and Schmidt 2023), body shaming can and is being intentionally, unintentionally, or inadvertently used in different sports coaching practices. Research has shown that also more body sensitive practices, like caring for an athlete in terms of controlling weight, can have unintended and potentially shaming consequences, not least during transitional life periods such as puberty (Desbrow Citation2021). Body sensitivity can thus be defined as empathetic and thoughtful actions towards athletes’ bodies, which can also have unintentional harmful effects, i.e. they can be shaming in its consequences. So, how body criticality and body sensitivity function in different coaching practices, or as we call it in this paper, the anatomy of body shaming in sports coaching, is thus a significant issue to be explored to understand its negative consequences on athletes’ health, body- and self-esteem, and general well-being. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore body critical and body sensitive sport coaching practices that have the potential to be shaming. The uniqueness of this paper is that we explore the deep roots of body shaming, that is an exploration of both body critical and body sensitive practices, as most studies have focused directly on more explicit body shaming instead of investigating the unintentional underlying practices that have the potential to be shaming.

Mapping body shaming in sports coaching practices

Body shaming has been recognized in different spheres, including the fashion industry (Lewis Citation2019; McClendon Citation2019), schools (Gam et al. Citation2020; Novitasari and Hamid Citation2021), social media in general (Hamid Citation2018; Hamid, Ismail, and Shamsuddin Citation2018, Mitra Citation2020; Mustafa et al. Citation2022), social media related to physical activity and health (Goodyear et al. Citation2022; Goodyear and Quennerstedt Citation2020), and professional sports (MacPherson and Kerr Citation2020, Citation2021; McMahon, McGannon, and Palmer Citation2022; McMahon et al. Citation2023; Willson and Kerr Citation2022).

Research on body shaming among young people has shown to have damaging effects on self-esteem and emotional well-being (Cherian and Mukherjee Citation2022; Syeda et al. Citation2023). Social media in particular has been proved to facilitate body shaming in young people and to have negative effects on self-esteem (Annah and Heriteluna Citation2023). Body shaming has also been shown to be a modern form of cyber aggression among young people (Židová, Kurincová, and Turzák Citation2022), and to have an association with sexting behaviours through social physique anxiety and SNS addiction symptoms (Ruiz et al. Citation2021). Significantly, a study conducted with 919 high school students in Rome showed that one in four students reported experiences of weight-related body shaming by peers or family members (Cerolini et al. Citation2024).

Research within sports has aimed to explain why coaches consciously or unconsciously adopt body shaming practices. Findings show that coaches adopt these practices because they believe athletes need to be fat-free to succeed (Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2017; McMahon and Dinan-Thompson Citation2008). The connection between a fat-free body and sporting success is, however, socially constructed. Significantly, such as in the case of swimming, the notion of ‘slim to win’ is deeply entrenched, which may lead coaches to adopt practices that are assumed to achieve this body ideal (McMahon and Dinan-Thompson Citation2008). In this regard, the notions of performance enhancement and perfectionism apply not only to the mastery of specific sport skills but also to the attainment of an idealized body shape, body composition, and body weight (McMahon and Penney Citation2013). For instance, using a Foucauldian perspective, McMahon and Penney’s (Citation2013) research showed that fat, weight, and food numbers are a focus of surveillance and regulation by coaches and others and by swimmers themselves. McMahon, McGannon, and Palmer (Citation2022) also explored the role of the athlete’s entourage, showing that athletes were subjected to body shaming from members of their entourage when their bodies failed to meet sociocultural expectations. Willson and Kerr (Citation2022) investigated the experiences of body shaming as a form of emotional abuse among female National Team athletes in aesthetic sports, showing that athletes experienced negative verbal comments about their bodies, body monitoring, forced restrictions of food and water, public criticism of their bodies, and punishment when body-related standards were not met.

Previous studies have shown that female athletes who are immersed in sports with a focus on leanness are more likely to develop eating disorders (Papathomas and Lavallee Citation2010). Some research has demonstrated that male athletes are also shamed for their weight and bodies (Atkinson Citation2011; McMahon and Barker-Ruchti Citation2016). ‘Big and strong to succeed’ is another aspect of body shaming practices, but also here a fat-free body is normalized, especially in masculinity-connoted sports. Significantly, body-shamed male athletes were also found to suffer from eating disorders (Freedman, Hage, and Quatromoni Citation2021). For example, Atkinson (Citation2011) investigated the influence of specific sport cultures on normalized disordered eating behaviours and body attitudes among male athletes. Body shaming has, therefore, been found to have serious short- and long-term consequences, including disordered eating and eating disorders (Flack Citation2021), body dissatisfaction (Neves et al. Citation2017), and the consumption of medication to lose weight (e.g. laxatives) (McMahon, Penney, and Dinan-Thompson Citation2012). Research has shown that coaches sometimes implicitly adopt body shaming in their coaching and in so doing, discourses of performance and (body) perfection have been found to seemingly pervade coaching pedagogies in different sporting contexts (McMahon and Dinan-Thompson Citation2008). Particularly important is when body shaming is explicitly, implicitly, or inadvertently used in coaching practices to achieve this ‘perfection’, as this can carry negative consequences for athletes’ wellbeing. That is, body shaming can be used in obvious ways (i.e. explicitly), in a way that it is not directly expressed (i.e. implicitly) or without knowledge or intent (i.e. inadvertently). While more explicit body shaming has been lately researched in sport related literature, there is a need to further investigate the underlying body critical and body sensitive assumptions and omissions that have the potential to be shaming.

Methods

In this section, we describe the participants and context of this study and the methods used to generate data. We also provide information about the ethical considerations of the study, and we describe the analyses carried out with the data.

Participants and context

The study involved 12 coaches from nine different sports in Sweden who coached mainly adolescents under the age of 18. The sample size was purposely selected so that we could have participants representing coaching in individual and team winter and summer sports that are femininity-connoted (artistic swimming; gymnastics), masculinity-connoted (boxing; American football; ice hockey; shot put and discus), and more ‘gender-neutral’ (cross-country skiing; orienteering). Overall, the recruited male (9) and female (3) coaches had different levels of coaching experience, ranging from five to 35 years. All coached high-level athletes (who trained at least 15 h per week), and all coaches except for one were former elite athletes themselves. All but two coaches coached both male and female athletes. An ethics application was submitted to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Etikprövningsmyndigheten Dnr 2021-03550). Informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to data generation, and all names were replaced with pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality.

Data generation

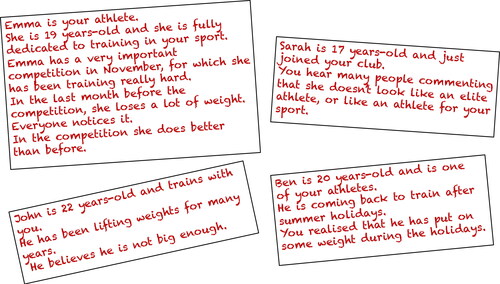

This study used photo elicitation interviews including vignettes for data generation because such tools have been shown to generate rich, in-depth, and detailed insights into the complexities of bodies in physical activity contexts (see e.g. Azzarito Citation2010, Lambert Citation2020, Varea and Pang Citation2018). Coaches were presented with short scenarios about the topic under study. These vignettes were created by the authors of this paper and portrayed different scenarios related to weight gain, weight loss, performance, and body shape ().

Additionally, photographs of a variety of bodies were sourced from different media and were used as a means of interview elicitation. Pictures were purposely chosen and agreed upon by all authors. They displayed different athletes’ body shapes practicing different sports and included male and female athletes. Pictures of athletes of the sport the specific participants coached were shown, as well as pictures of athletes of ‘opposite sports’ than what they coached (e.g. photographs of rhythmic gymnasts to the boxing coaches and vice versa). However, most of the pictures were the same for all coaches. The coaches were invited to comment on the photographs and talk about issues related to health, (un)healthy bodies, fitness, fatness, and health and performance advice ().

The interview questions focused on the perceptions of body size, possible advice given to athletes, weight, levels of fitness, and lifestyle. Examples of questions included: ‘What do you think about this scenario?’, ‘How would you act in a scenario like this?’, ‘Can you identify yourself with this story?’, ‘Do you think she is a successful athlete?’, ‘Would you provide him with some advice?’. Vignettes were used at the beginning of the interview (prior to showing the coaches the pictures) to avoid them having an image already in their minds while talking about the vignette scenarios. Interviews were conducted in Swedish, transcribed verbatim, and the quotes used for this article were translated to English by Authors 2 and 4.

A pilot study was conducted prior to data generation. The participants of the pilot study were two colleagues (at the time of data collection), who had experience in coaching elite athletes, one in a team and the other in an individual sport. They both confirmed the relevance of the vignettes and pictures and stated that it was an easy starting point to comment on topics related to bodies and weight. However, they advised modifying the vignettes to take into account season, sex, and age so it would align better with coaches’ different sporting contexts. Following this suggestion, we tailored the vignettes prior to each interview, but without changing the scenario frameworks.

Data analysis

Critical reflection, as described by Fook and Gardner (Citation2007), provided a framework to deconstruct the data and explore the interviewed coaches’ assumptions and taken-for-granted truths. Critical reflection is thus used as a foundation for approaching this research, and it involved a process of deconstructing and reconstructing assumptions related to body critical and body sensitive practices. The analysis of data entailed five steps.

First, all interview transcripts were read through by all researchers to familiarize themselves with the data and formulate analytical questions in relation to our aim. Second, we used the analytical question: what types of body criticality and body sensitivity can explicitly, implicitly, and inadvertently be identified in coaching practices in the different sports? That is, we looked for body critical and body sensitive practices used in obvious ways (i.e. explicitly), in a way that it is not directly expressed (i.e. implicitly) or without knowledge or intent (i.e. inadvertently). The analytical question was used independently by the researchers. In so doing, each researcher formulated initial themes representing various types of body critical and body sensitive practices that have the potential to be shaming. Third, potential themes underwent thorough dialogue to agree on the themes that were ‘in common’. Fourth, the nuances within each theme were unpacked in terms of body critical and body sensitive practices using further agreed upon analytical questions: (i) What is the logic within the theme? (ii) What are the assumptions around body weight within the theme? (iii) How do body criticality and body sensitivity function in coaching practice? All co-authors were, throughout the whole process, given the possibility to make judgements in relation to different points of view and positions in relation to research in the field. The four authors’ diverse backgrounds and experiences (history, sociology, education) also acted as a quality check of the research. Fifth, after reaching collective agreement on the identified types of body critical and body sensitive practices that have the potential to be shaming, the themes were discussed again to deliberate the presentation of each theme and claims in terms of the logics and assumptions of body critical and body sensitive practices. The constructed themes are presented below and were classified into seven types of body critical and body sensitive practices that have the potential to be shaming.

Results

In the study, seven types of coaching practices that have the potential to be shaming were identified. These were: (1) unrecognition and avoidance; (2) ‘good’ body talk; (3) education of athletes; (4) the use of humour and irony; (5) the use of science and tests; (6) the making of weight gain a lack of motivation; and (7) Individualization. Under each of the categories presented below, the identified logics, assumptions, and functions of the body critical and body sensitive coaching practices that have the potential to be shaming are clarified.

Unrecognition and avoidance

Unrecognition and avoidance involve approaching body sensitive issues by denying their existence or avoiding the issue in the coaching practice. More specifically, two of the coaches argued that issues related to body shaming do not occur within their sports, or at least not in their club. The logic communicated was that coaching practices in Sweden do not include body shaming since the culture and history of coaching in Sweden are different to many other countries. For example, the artistic swimming coach affirmed, ‘Abroad yes. I can say that with certainty. But we have a better body culture in Sweden’. The assumption here is that coaching practices in Sweden do not include body shaming since the culture and history, in a sense, are different than in many other countries.

Furthermore, topics related to body weight and shape were, according to a couple of the coaches, avoided and not talked about, as they were not considered necessary to address in coaching in their sport. The few times that the issue was explicitly addressed by the coaches was when the athletes themselves initiated a conversation. This logic implies that if the athletes do not discuss these topics with the coaches, it is because there is no need to do so. It also has the function that by not talking about these issues, they are non-existent.

Almost half of the coaches are hesitant to talk about bodies and weight because the issues are taboo. The cross-country skiing and orienteering coaches acknowledged this as follows:

Why it is taboo …? Body shape is still very sensitive. I don’t think there is enough support around athletes to take care of. It’s a fear that we say things and that they, as a consequence, end up in these problems. That’s what I think. (Cross-country skiing coach 1)

But, not talking much about it while she, the other one in the national team, who I think … well, it fits because they talk about these things, keep track of your weight and stuff. So why shouldn’t we bring up and talk about these things? (Orienteering coach 2)

Well, I wouldn’t have acted just because we have a problem at the other end, and I know how triggering it can be and what consequences it can have, so I think I’d have let it be. (Gymnastics coach)

The above quotes illustrate that the coaches are aware of how sensitive body and weight can be and that they do not always feel well-equipped to deal with these issues. They try to be sensitive and do not want to risk causing harm by attempting to engage in conversations. Hence, the logic is that by starting conversations on body weight, coaches feared that they might trigger eating or exercise disorders among their athletes. In so doing, coaches were clearly aware of the potential risks that their comments entail and the damaging effects they might cause their athletes.

A strategy to avoid discussions or confrontations regarding body-sensitive topics, which half of the interviewed coaches suggested, is normalization and routinization of body-related practices, such as weighing athletes. Here, it is assumed that the repetition normalizes these practices, reducing potential damaging effects. There is, accordingly, a logic of denial of the existence of body shaming in this type of coaching practice. Further, body shaming is perceived as something that can be avoided by making it ‘normal’.

The ‘good’ body talk

Another type of coaching practice that has the potential to be shaming refers to the idea of ‘good bodies’, i.e. what a reasonable and good body weight (and shape) would be in each sport. The logic here is that certain bodies enhance performance. The coaches’ comments indicated that it is ‘obvious’ to them what such ‘good bodies’ are. Losing weight was considered a related, positive effect:

If this person would come back and be in this environment and want to train … then you start with … Okay, what are your goals? I want to come back to top 10 in Sweden. Okay. What do you need to do then? It isn’t enough with five practices a week, you need to do ten practices a week, and how should they look like? What should you train? Quite often, this person will lose weight just by the change of lifestyle … and then it’d be really strange if the person did not realize that weight is a factor. (Orienteering coach 1)

The ice hockey coach further explained that in his sport, big and muscular bodies used to be idealized, but that this has diversified. However, this coach felt that it would be good if coaches talked about these issues more explicitly, as many players cannot become big and strong. This coach had heard from a friend who plays in the NHL that he is being asked to eat more and become bigger (Ice hockey coach). It is assumed that a big body is a good body in terms of ice hockey performance. Similarly, one of the American football coaches offered an example of referring to what a good body is: ‘I have said to many of our players ‘don’t get too ripped. Don’t mortify yourself. This is not bodybuilding or gymnastics. You should be able to move yourself, but you also have to be able to take a hit”’ (American football coach 2). What is communicated here is that a good body is a body that is devoid of fat.

Within this type of practices, the logic is that since there are ‘good bodies’ for performance, there are also ‘bad ones’. What constitutes a ‘good’ or ‘decent’ body was obvious to the coaches, which also entailed moral connotations of how such bodies look like. These practices function through normalizing bodies, portraying actions such as weight loss as something easy while weight gain as something problematic.

Education of athletes

The education of athletes on issues relating to body and weight is about addressing body and weight as a question about the lack of knowledge regarding nutrition and training among the athletes. The logic is that the reason why athletes do not eat or train in the right way, and therefore weigh too little or too much or do not perform as expected, is that they lack nutritional and training knowledge. Consequently, the coaching strategy entails the education of athletes and was expressed by all the coaches. This includes recommendations by the coaches regarding lifestyle and diet. For example, the ice hockey coach commented that if a player looked too thin or, which is more common, has gained weight during a summer break, he would introduce a dietary scheme to show them what they need to do food-wise to train and perform better (Ice hockey coach).

Furthermore, one of the cross-country skiing coaches highlighted how a particular incident encouraged them to educate the athletes about what to eat and not to eat:

We have had occasions last year when moving from the tunnel [indoor snow facility] to outdoors, then some athletes bought a Snickers bar and it was like sugar sort of and something to drink. But then we took an hour going through the difference between a snack and a snack. We separated them regarding how it’d look like and what happens to the blood sugar and so on. So, we tried to educate them in doing the right thing instead of snapping them off about what not to eat. That’s what we did. (Cross-country skiing coach 1)

We just try to communicate that energy is a precondition, ‘you have to eat’, and we really don’t lay any value in what they eat, but it is… just in our case we have not had any problems with, well at the other end, so to speak, only that they eat too little. (Gymnastics coach)

We always have lectures about diet where we bring in an expert because it doesn’t have to be me as a coach. Instead, I think it’s good to bring in others, so they hear that it isn’t only me thinking certain things.

The use of humour and irony

One way to downplay or comment on sensitive issues or ideal bodies is through the use of humour or irony. More specifically, a couple of the coaches recounted communicating a particular way of how to look or be, or how to act or not act, by presenting it in an ironic way or as a joke. By doing this, the ‘saltiness of a message’ can be ‘sweetened’. For example, one of the orienteering coaches recounted how he had been approached by his athletes, telling him about another coach who joked in front of his athletes, saying, ‘rather light than full’ (in Swedish: hellre lätt än mätt). What that coach can be seen to have communicated is that a light body is better for running than eating until you are full. Even if said as a joke, the athletes did not understand it in this way and told their orienteering coach because they understand what such comments can trigger in athletes (e.g. eating disorders).

The interviewed orienteering coach then started to reflect on his own coaching practices and realized that he may have made similar comments about bodies. He recounted that in the gym, while strength training, he had made comments such as ‘beach 2021, here we come’ (in Swedish: mot beach 2021). While meant as a funny comment about himself (i.e. trying to lose weight and build muscles to show off at the beach), the orienteering coach reasoned that his comment could idealise the lean and muscular body, which may make athletes who overhear this comment feel bad.

Another illustration of the use of humour and irony to communicate that a light body is the right body was provided by one of the cross-country skiing coaches. Reflecting on the past, the coach thought that maybe 10–15 years ago, when an athlete returned from a summer break and had gained weight, coaches may have said something like, ‘too little training?’ However, this coach has witnessed a shift lately towards greater awareness of what coaches can say and what they should avoid. Consequently, this coach is avoiding making jokes or ironic comments today (Cross-country skiing coach 2).

The use of science and tests

The practice of using science and tests refers to making issues of bodies and weight ‘objective’ by using medical or physiological science and measurements. More specifically, what the majority of the coaches say they do is to tackle potentially sensitive situations by making body weight a question of quantified data, i.e. only science and tests can objectively judge whether something is right or wrong. This logic implies that if the numbers show desired values, then the athlete is fine. Producing such data also demonstrates that numbers are valid. The function is that it allows coaches to use the numbers to communicate an issue to athletes, such as weight gain, rather than formulating a reasonable argument.

The practice of using science and measurements to address issues regarding body and weight is evident in the coaches’ statements. For example, the ice hockey coach expressed that in one of the training environments he is working in, the testing regimes and follow ups of individual players are extensive, including nutrition and monthly muscle mass and fat percentage measurements. These measurements are not taken by the coach, but the physiotherapist, which adds to the perception of body and weight being someone else’s responsibility.

The use of science and tests was further illustrated by one of the American football coaches. His general approach is that a coach does not know anything about an athlete until they are tested. According to the coach, the common practice in American football is to use evidence-based physiological profiles of the different player positions. Taking age and sex into account, the profiling entails the comparison of the position’s prescribed weight and performance with that of the players’ body and weight (e.g. strength; speed; mobility). When asked to elaborate on how he would approach the fictive player Emmanuel from the vignette used in the interview, who quickly lost a lot of weight but still performed very well, the coach said:

I’d be very concrete. We’d look at his numbers. I guess that’s a part of it – what do the numbers say? It’s both his status now and his journey to be able to identify cause and effect. What is it that has this effect? (American football coach 1)

But we can approach this on several levels. Is this more psychological? How does Emmanuel feel mentally? In that case, it’s much more about asking Emmanuel about how he feels and let him describe his own situation, in addition to what his numbers say. And that’s of course much harder. (American football coach 1)

One of the orienteering coaches offered another illustration of tackling potentially sensitive situations and issues regarding bodies and eating. When facing the situation of premature performance peaking through intentionally losing weight, and to prevent this practice from spreading to junior athletes, he described how he frames his talks about nutrition and energy intake using a ‘scientific’ vocabulary:

But it [that senior athletes intentionally lose weight to peak their performance] can be a bit problematic, for sure […] Then we, for example, can talk about the energy intake when training and competing. We can kind of highlight what we do and what we don’t do. How it should look like. When we train at night it’s very important to eat like this and when we are on training camps one eats a little bit more. (Orienteering coach 1).

Coach: We weigh everyone in the lab. Well, I don’t weigh them. […] I cast an eye on it and then they write themselves. […] I don’t stand with a pointer and say ‘now we will take your weight and I will take notes’. They also measure their height, and they should also fill in other things – so it becomes a natural part of that. […] If you’d weigh them regularly at the upper secondary school, it might have consequences, but to be in the lab, it’s like going to the school nurse or to the doctor or something, and then it becomes natural. So, we have not got any complaints about that at all. (Cross-country skiing coach 2)

However, the weighing is not primarily about ensuring the athletes do not gain too much weight. In orienteering and cross-country skiing, for example, it is rather to control that they are not losing too much weight, as the coaches understand that this is a problem in their sports.

No matter what the intentions are and no matter how weighing is framed, the logic of weighing has the function of making weight crucial for optimal performance. Through bodily measurements, it is assumed that bodies can be quantified and judged according to sport-specific requirements. Numbers thus have the function to transmit messages in more straightforward ways than other means to communicate how performance can be enhanced. The logic of using measurements is that numerical data is generated to determine athletic performance. The prioritizing of numbers, however, carries the risk of overshadowing the well-being of the athlete. Hence, what is assumed is that if the numbers show that the athletes perform well, there is no problem.

The making of weight gain a lack of motivation

Making weight gain a lack of motivation entails describing weight gain as a problem. In contrast to losing weight, which most of the coaches considered a medical issue, gaining weight is constructed as a matter of having personal problems or lacking motivation to perform better. As an illustration, one of the cross-country skiing coaches explained that if an athlete gains weight, she would think that it had to do with lack of motivation that could come from illness or a problem in the family (Cross-country skiing coach 1). Similarly, although the coach felt that weight gain during holidays is normal, if the athletes are unable to lose that weight after being back in training, the weight gain is problematized as a motivational issue:

So, I’d ask … now that you are back in school [a school for elite athletes], how is it with your motivation? What do you think about that? Now we need to come back to our routines, and so forth. So, then he [the athlete] should talk about his routines during the summer holiday. It might have been more sleep in the mornings … But what about other routines with breakfast, lunch, and dinner, maybe he can say something about that. It might have been negligence and I’d ask what he thinks about that (Cross-country skiing coach 1).

Individualization

Individualization is about coaches suggesting a certain way of eating or training to get athletes back on track to perform better, avoiding telling them they weigh too much or too little. The logic is that being implicit and focusing on the solution or a specified goal is better than being explicit and focusing on the problem. To achieve this, several of the coaches individualize performance in the sport.

The ice hockey coach offered an example of individualization by recounting that when one of his players lost too much weight, he, out of concern, gave him a personalized training program and a dietary scheme. Such an approach would also be used if a player had gained too much weight, which, according to the coach’s experience, is much more common. ‘Then, we used to talk a little bit about a dietary plan, and I ask them: “But is it [a plan] something you would be interested in, to get you down to where we… [want]?”’ (ice hockey coach). In addition, the coach argued that to be able to control what the players are eating, they are offering them lunch boxes. The main logic for doing this is that organized meals are convenient for the young players who arrive at training directly from school. This strategy also prevents the players from getting restaurant or fast-food. It is thus in relation to this general offer of food that players can be proposed a specific dietary plan. However, the ice hockey coach emphasized that neither lunch boxes nor taking on a dietary scheme are mandatory; it is up to the individual player to assume their responsibility.

One of the American football coaches offered similar examples as the ice hockey coach. He had experienced that players needed to become stronger and, therefore, needed to consume a special diet.

One needs to help them with extra snacks and monitor their nutrition, but it was almost impossible to make them gain weight because of their bodies… the whole system has made it difficult, so we needed to get help from RF’s [the Swedish sport confederation] nutritionists and specialists at Bosön to make it happen. That was messy. (American football coach 2)

Also, when a player has what the American football coach referred to as an unhealthy weight and needs to lose kilograms, the strategy is to individualize the issue.

We can’t make a 145 kilo-guy run 5 kilometres because his knees can’t handle it. Instead, it’s biking or swimming, but the discussion always starts from a sport performance perspective. ‘I think you will be a better football player if we can do something about that [the unhealthy weight]’. (American football coach 2)

This coach also stated that it is better to talk about skills than a specific weight. The focus should be on how to be stronger and faster so the player can enhance performance.

The gymnastics coach provided an example of being more explicit and not allowing room for alternatives. She stated that at the moment, one of her gymnasts is too thin, so the coaching team has given her an ultimatum: if she wants to train, she has to eat properly. The coach has also recommended that athletes contact eating disorder specialists or the nurse at the athletes’ schools. When it is not acute, she said she can be a little bit more subtle and say something like: ‘During this period, we will have a little bit more strength training, so try to get some more proteins in you’ (Gymnastics coach).

Discussion

Results from this study show that coaches use unintentional and inadvertent practices in their coaching that have the potential to be shaming. In contrast to the findings from Willson and Kerr (Citation2022), the coaches in our study did not in any way intend to shame the athletes, on the contrary, they aimed to give well-intended advice or use ways to objectify or not recognize the issue. The coaches in our study were well-aware of the potentially damaging influence that they can have on athletes, and therefore, they preferred not to intervene in possible sensitive topics.

In general, the coaches demonstrated that they care about the athletes, similar to the coaches in Gano-Overway (Citation2023) study, where coaches tried to understand the athletes holistically. However, by not intervening or ignoring pertinent issues relating to body and weight, the coaches do not necessarily care for athletes as they assume that everything is fine. In so doing, the coaches were simultaneously saying that they cared for athletes, but at the same time, their fears overrode and showed ‘inaction’.

By making everything related to performance and numbers as ‘normal’ and not sensitive could be problematic. Aligning with McMahon and Penney’s (Citation2013) research we would argue that if coaches do not initiate these sensitive conversations, it can be more harmful to athletes than risking possible triggers. Coaches are just too concerned regarding what the most appropriate way to do something is. In contrast, Becker’s (Citation2009) study showed how athletes described their best coaches as those who were not afraid to make mistakes. The fears of this study’s coaches about doing something wrong prevail, and therefore, they prefer not to do anything if there is nothing too visible that needs to be done. In so doing, it could be too late, and the coaches are operating only in a preventive way, and importantly, they are not aware of this.

Coaches also showed uncritical statements about education and the use of science in their coaching practices. They did not question or challenge the veracity or the dominant discourses related to performance and health when it comes to the education of athletes and scientific tests. Furthermore, by normalizing and routinizing certain body sensitive practices, the assumption was that athletes would not feel uncomfortable.

Of course, we can ask ourselves what coaches should do then, as they seem to be in a no-win situation. In alignment with McMahon et al. (Citation2023) study, we believe that coaches should adopt a critically reflective stance in relation to analyzing body sensitive practices and that there is a need to develop more critical education programs that teach about body shaming in sport. In doing so, coaches will be better prepared to challenge dominant discourses about performance, and they will be able to educate their athletes in critical ways to include more than just one approach to coaching for high performance. Coaches need to work on creating awareness together with the athletes and being pro-active rather than re-active or avoidant. Coaches are just as responsible for what they teach as for what they do not teach making well-informed judgements about their coaching. Coach educators should also promote reflexivity and criticality in their programs.

Further research is also needed to investigate the possible gendered nature of body shaming, as coaches from this study described how, in some cases, they would act differently if they were dealing with a male or a female athlete. They were also aware of how female athletes were more sensitive to certain topics. While the focus of this paper was not on gender, we cannot ignore the gendered nature of the body since fitness, according to Brabazon (Citation2006), can be understood as a feminist issue (Brabazon Citation2006), and women continuously have been shamed in sport (Liston Citation2021). Gender is closely related to the body in general and body shaming in particular including body sensitive practices such as weighing athletes and measuring body fat. Hence, more research focusing on gender is needed to explore how athletes experience the most subtle and invisible ways of body critical and body sensitive practices and how they internalize this well-intended but still potentially shaming advice from the coaches.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to explore body critical and body sensitive sport coaching practices that have the potential to be shaming, or as we call it in the title of the paper, the anatomy of body shaming. The results demonstrate that body critical and body sensitive practices function in different subtle ways in coaching practice. For example, it functions through avoidance and denial, through talking about ‘good’ bodies, through the education of athletes, through the use of irony and humour, through making weight gain a lack of motivation, and through individualization. Of course, at the centre of these concerns is athletes’ health and well-being, which inspired the idea for this paper.

Our study also shows possible implications for coach education and practice. Coach education programs should ensure that coaches are well-prepared to address sensitive issues in coaching practices and that they are capable of initiating these kinds of conversations with athletes. While there have been some attempts to educate both coaches and athletes on different kinds of abuse (see e.g. McMahon et al. Citation2023), coaches are still showing fears, indecision and re-active practices in relation to these issues. We hope that by conducting more research in this area, coaches become more pro-active in critically reflecting on their practices relating to bodies and weight in order to prevent body shaming in their practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Annah, I., and M. Heriteluna. 2023. “The Effects of Social Media and Body Shaming on Self Esteem Amongst Adolescent.” In Proceeding of 1st Polkesraya International Conference, edited by Mahalia, L. D., Sukriani, W., Noordiati, S., Innah Mashar, H. M., and Annah, I. Retrieved from: http://repo.polkesraya.ac.id/2803/1/1.pdf

- Atkinson, M. 2011. “Male Athletes and the Cult(Ure) of Thinness in Sport.” Deviant Behavior 32 (3): 224–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639621003748860.

- Azzarito, L. 2010. “Ways of Seeing the Body in Kinesiology: A Case for Visual Methodologies.” Quest 62 (2): 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2010.10483639.

- Barker-Ruchti, N., R. Kerr, A. Schubring, G. Cervin, and M. Nunomura. 2017. “Gymnasts Are like Wine, They Get Better with Age”: Becoming and Developing Adult Women’s Artistic Gymnasts.” Quest 69 (3): 348–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1230504.

- Becker, A. J. 2009. “It’s Not What They Do, It’s How They Do It: Athlete Experiences of Great Coaching.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 4 (1): 93–119. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.4.1.93.

- Brabazon, T. 2006. “Fitness is a Feminist Issue.” Australian Feminist Studies 21 (49): 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164640500470651.

- Cerolini, S., M. C. Vacca, A. Zegretti, A. Zagaria, and C. Lombardo. 2024. “Body Shaming and Internalized Weight Bias as Potential Precursors of Eating Disorders in Adolescents.” Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1356647. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1356647.

- Cherian, A., and S. Mukherjee. 2022. “The Vicious Loop of Body Shaming and Self-Projection: An Explorative Study of Indian Young People Aged 20-30 Years Old.” Youth Voice Journal 2: 69–79.

- Desbrow, B. 2021. “Youth Athlete Development and Nutrition.” Sports Medicine 51 (Suppl 1): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01534-6.

- Flack, S. R. 2021. The Influence of Maternal Body-Shaming Comments and Bodily Shame on Portion Size. South Florida: University of South Florida ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Fook, J., and F. Gardner. 2007. Practicing Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. London: Open University Press.

- Freedman, J., S. Hage, and P. A. Quatromoni. 2021. “Eating Disorders in Male Athletes: Factors Associated with Onset and Maintenance.” Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 15 (3): 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2020-0039.

- Gam, R. T., S K. Singh, M. Manar, S. K. Kar, and A. Gupta. 2020. “Body Shaming among School-Going Adolescents: Prevalence and Predictors.” International Journal of Community Medicine And Public Health 7 (4): 1324–1328. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20201075.

- Gano-Overway, L. A. 2023. “Athlete’s Narratives of Caring Coaches Who Made a Difference.” Sports Coaching Review 12 (1): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2021.1896208.

- Gilbert, P., and J. Miles, eds. 2002. Body Shame. Conceptualisation, Research and Treatment. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

- Goodyear, V., and M. Quennerstedt. 2020. “#Gymlad – Young Boys Learning Processes and Health-Related Social Media.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (1): 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1673470.

- Goodyear, V., J. Andersson, M. Quennerstedt, and V. Varea. 2022. “#Skinnygirls: Young Girls’ Learning Processes and Health-Related Social Media.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1888152

- Greenleaf, C. 2004. “Weight Pressures and Social Physique Anxiety among Collegiate Synchronized Skaters.” Journal of Sport Behavior 27: 260–276.

- Hamid, B. A. 2018. “The Power to Destruct: Online Fat Shaming Bullying in Social Media.” In Stop Cyberbullying, edited by T. K. Hua, 35–50. Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- Hamid, B. A., H. Ismail, and C. M. Shamsuddin. 2018. “Haters Will Hate, but How? The Language of Body Shaming Cyberbullies in Instagram.” In Stop Cyberbullying, edited by T. K. Hua, 80–101. Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- Kerr, G., E. Berman, and M. De Souza. 2006. “Disordered Eating in Women’s Gymnastics: Perspectives of Athletes, Coaches, Parents and Judges.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 18 (1): 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200500471301.

- Krentz, E. M., and P. Warschburger. 2011. “Sports-Related Correlates of Disordered Eating in Aesthetic Sports.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 12 (4): 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.03.004.

- Lambert, K. 2020. “Re-Conceptualizing Embodied Pedagogies in Physical Education by Creating Pre-Text Vignettes to Trigger Pleasure ‘In’ Movement.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 25 (2): 154–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1700496.

- Lewis, R. 2019. “Modest Body Politics: The Commercial and Ideological Intersect of Fat, Black, and Muslim in the Modest Fashion Market and Media.” Fashion Theory 23 (2): 243–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2019.1567063.

- Liston, K. 2021. “Honour and Shame in Women’s Sports.” Studies in Arts and Humanities 7 (1): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.18193/sah.v7i1.199.

- MacPherson, E., and G. Kerr. 2020. “Online Public Shaming of Professional Athletes: Gender Matters.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 51: 101782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101782.

- MacPherson, E., and G. Kerr. 2021. “Sport Fans’ Responses on Social Media to Professional Athletes’ Norm Violations.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19 (1): 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1623283.

- McClendon, E. 2019. “The Body: Fashion and Physique—A Curatorial Discussion.” Fashion Theory 23 (2): 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2019.1567057.

- McMahon, J., and D. Penney. 2013. “(Self-) Surveillance and (Self-) Regulation: Living by Fat Numbers within and beyond a Sporting Culture.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 5 (2): 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.712998.

- McMahon, J., and M. Dinan-Thompson. 2008. “A Malleable Body – Revelations from an Australian Elite Swimmer.” Healthy Lifestyles Journal 55 (1): 23–28.

- McMahon, J., and N. Barker-Ruchti. 2016. “The Media’s Role in Transmitting a Cultural Ideology and the Effect on the General Public.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 8 (2): 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1121912.

- McMahon, J., D. Penney, and M. Dinan-Thompson. 2012. “Body Practices – Exposure and Effect of a Sporting Culture? Stories from Three Australian Swimmers.” Sport, Education and Society 17 (2): 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.607949.

- McMahon, J., K. R. McGannon, and C. Palmer. 2022. “Body Shaming and Associated Practices as Abuse: Athlete Entourage as Perpetrators of Abuse.” Sport, Education and Society 27 (5): 578–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1890571.

- McMahon, J., M. Lang, C. Zehntner, and K. R. McGannon. 2023. “Athlete and Coach-Led Education That Teaches about Abuse: An Overview of Education Theory and Design Considerations.” Sport, Education and Society 28 (7): 855–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2067840.

- Mitra, S. 2020. “Trolled, Body-Shamed and Slut-Shamed: The Desecration of the Contemporary Bollywood Female Star on Social Media.” Celebrity Studies 11 (1): 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2020.1704388.

- Mosewich, A. D., A. B. Vangool, K. C. Kowalski, and T.-L. F. McHugh. 2009. “Exploring Women Track and Field Athletes’ Meanings of Muscularity.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 21 (1): 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200802575742.

- Mustafa, M. S. A., I. R. Mahat, M. A. M. M. Shah, N. A. M. Ali, R. S. Mohideen, and S. Mahzan. 2022. “The Awareness of the Impact of Body Shaming among Youth.” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 12 (4): 1096–1110. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i4/13197.

- Neves, C. M., J. F. Filgueiras Meireles, P. H. Berbert de Carvalho, A. Schubring, N. Barker-Ruchti, and M. E. Caputo Ferreira. 2017. “Body Dissatisfaction in Women’s Artistic Gymnastics: A Longitudinal Study of Psychosocial Indicators.” Journal of Sports Sciences 35 (17): 1745–1751. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1235794.

- Novitasari, E., and A. Y. S. Hamid. 2021. “The Relationships between Body Image, Self-Efficacy, and Coping Strategy among Indonesian Adolescents Who Experienced Body Shaming.” Enfermería Clínica 31 (2): S185–S189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2020.12.019.

- Papathomas, A., and D. Lavallee. 2010. “Athlete Experiences of Disordered Eating in Sport.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 2 (3): 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.517042.

- Reel, J. J., T. A. Petrie, S. SooHoo, and C. M. Anderson. 2013. “Weight Pressures in Sport: Examining the Factor Structure and Incremental Validity of the Weight Pressures in Sport – Females.” Eating Behaviors 14 (2): 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.003.

- Ruiz, M. J., G. Sáez, L. Villanueva-Moya, and F. Expósito. 2021. “Adolescent Sexting: The Role of Body Shame, Social Physique Anxiety, and Social Networking Site Addiction.” Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking 24 (12): 775–852.

- Ryall, E. S. T. 2019. “Shame in Sport.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 46 (2): 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2019.1609359.

- Schlüter, C., G. Kraag, and J. Schmidt. 2023. “Body Shaming: An Exploratory Study on Its Definition and Classification.” International Journal of Bullying Prevention 5 (1): 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-021-00109-3.

- Syeda, H., I. Shah, U. Jan, and S. Mumtaz. 2023. “Exploring the Impact of Body Shaming and Emotional Reactivity on the Self-Esteem of Young Adults.” CARC Research in Social Sciences 2 (3): 60–67. https://doi.org/10.58329/criss.v2i3.30.

- Thompson, R. A., and R. T. Sherman. 1999. “Athletes, Athletic Performance, and Eating Disorders: Healthier Alternatives.” Journal of Social Issues 55 (2): 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00118.

- Torstveit, M. K., J. H. Rosenvinge, and J. Sundgot-Borgen. 2008. “Prevalence of Eating Disorders and the Predictive Power of Risk Models in Female Elite Athletes: A Controlled Study.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 18 (1): 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00657.x.

- Vani, M. F., E. Pila, M. de Jonge, S. Solomon-Krakus, and C. M. Sabiston. 2021. “Can You Move Your Fat Ass off the Baseline?’ Exploring the Sport Experiences of Adolescent Girls with Body Image Concerns.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (4): 671–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1771409.

- Varea, V., and,B. Pang. 2018. “Using Visual Methodologies to Understand Pre-Service Health And physical Education Teachers’ Subjectivities of Bodies.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (5): 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1228625.

- Willson, E., and G. Kerr. 2022. “Body Shaming as a Form of Emotional Abuse in Sport.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 20 (5): 1452–1470. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1979079.

- Židová, M., V. Kurincová, and T. Turzák. 2022. “Body Shaming as a Modern Form of Cyber Aggression.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Research 12 (2): 270–274.