Abstract

The paper explores the interplay of elaborate light and sound technologies used in the worship services of Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas. During the renovation and reconstruction of the church venue from former basketball stadium to church auditorium, the church hired professional companies to design and outfit the huge 16,000 seat auditorium in order to create a worship space, which simultaneously is meant to serve as a meeting space for the congregation and as an intimate place for a personal encounter with God. Worship services at Lakewood Church are multi-sensory events in which lights on the ceiling, in the auditorium, and on stage interplay with sound, vision, and space in order to structure the worship service and to mediate divine presence. The analysis is based on fieldwork data acquired on site and textual data drawn from portfolios of the technological companies involved in the reconstruction and outfitting of the church auditorium. I argue that despite the capaciousness of the space an atmosphere of intimacy is created through a specific lighting scheme that departs from traditional church lighting practices.

Introduction

I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in

darkness, but will have the light of life.(John 8:12 NIV)

Light is a powerful metaphor in Evangelical discourse and theology signifying Jesus, salvation, and eternal life. A believer receives the gift of eternal life through the atoning work of Christ on the cross. Consequently, rejecting God’s message of eternal life results in “walking in darkness,” the absence of light, life and salvation (John 8:12 NIV). Such “crucicentrism” is a cornerstone of Evangelical theology and piety (Bebbington Citation1993, 16). The acknowledgement of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is central to the Evangelical conversion experience and the base on which believers build a personal relationship with God. The centrality of Christ’s death at the cross is regularly thematized in preaching, worship, and Bible study. It is mediated not only through spoken discourse focusing on the Word of God, but also through multi-sensory experiences in worship services, Evangelical crusades, and conferences. Although Evangelical discourse focuses on the Word of God, Evangelicals’ lived religion has a strong experiential dimension that offers sensory experiences of faith (Schmidt Citation2000, 38–77; Luhrmann Citation2004; Hitzer and Scheer Citation2014; Stevenson Citation2013). Evangelicalism’s “emotional style” in discourse and practice actively engages and stimulates emotionality, which translates into visible experiences and the expression of strong feelings during worship services and prayer meetings (Hitzer and Scheer Citation2014). Joyous, celebratory feelings are often expressed by singing, dancing, cheering, and clapping hands, whereas swaying, trembling, sobbing or crying indicate deep emotional movement that usually is verbalized afterwards as a sign of being in God’s presence or being touched by the Holy Spirit. Evangelical worship services are the place where the expression of those feelings are witnessed, learned, nurtured and practiced. Jill Stevenson describes contemporary worship services in megachurches as a “performative genre” that employs an “Evangelical dramaturgy.” Such a dramaturgic system enables rhythmic experiences that function as powerful religious tools in cultivating and embodying particular religious beliefs. Evangelical dramaturgy is structured by an interplay of “performative elements” in which space, light, and sound play a significant role. Together with the religious actors on stage and the attendees in the audience, these elements create an “affective atmosphere” meant to enable a believer’s encounter with God (Stevenson Citation2013, 24–26, 162).

The article explores the interplay of elaborate light and sound technologies used in the worship services of Lakewood Church, a megachurch in Houston, Texas. During the transformation of the former basketball stadium into Lakewood Church’s new sanctuary, the church hired professional companies to design and outfit the huge 16,000 seat auditorium. Their stated task was to create a worship space, simultaneously meant to serve as a meeting space for the huge congregation, an intimate place for a personal encounter with God, and also a production set for senior pastor Joel Osteen’s TV ministry. Worship services at Lakewood Church are multi-sensory events in which lights on the ceiling, in the auditorium, and on stage interplay with sound, vision, and space in order to structure the worship service, to stimulate emotion and the anticipation of feelings of closeness to God in order to mediate divine presence.1 I argue that despite the capaciousness of the space an atmosphere of intimacy is created through a specific lighting scheme that departs from traditional church lighting practices and instead utilizes insights from stage production and theatre lighting.

I will first provide some ideas about light and the systematic use of lighting technologies to produce atmosphere in performative practices. Second, I will describe the restructuring of the former sports arena into a church sanctuary and what kind of lighting system was installed at Lakewood Church. I will then proceed to analyse how the lighting systems are used in the worship services, what kind of effects they are meant to produce and how they support the Evangelical dramaturgy in creating affective atmospheres, which enable the experience and cultivation of specific Evangelical beliefs and practices.

Light, Lighting, and the Creation of Atmosphere

Light is the seemingly intangible, ephemeral material substance that illuminates spaces and things and thus renders them visible to the human eye. Light not only reveals and thereby directs the viewers’ attention to what is visible, it also hides from sight what is not reached by the beams of light, and consequently, is still shrouded in darkness. Light’s ephemerality and intangibility might have contributed to the fact that no entry has been dedicated specifically to “Light” in Key Terms in Material Religion (2015) although the entries “Display,” “Sensation,” and “Vision” touch upon light as something that is sensed and seen.

The German philosopher Gernot Böhme contends that light as such is not visible and always needs a medium to be seen, i.e. a medium in which it manifests, a surface to fall on or a space it illuminates. He proposes the term “lightness” to indicate the perception of the presence of light and thus visibility; the term “lightness” functions in analogy and opposition to darkness or the absence of light and thus non-visibility (Böhme Citation2017, 197–200). For Böhme, lightness is linked to the perception of space, an observation that is useful for the analysis of how light structures the worship space in a megachurch auditorium and how it enables the production of a specific worship atmosphere:

The fact that lightness creates space is largely responsible for the emotional – or, to cite Goethe, the sensual–moral effects of lightness. As things become visible in the light, they also appear to us in space. Space is not created by the distances between things. It is merely articulated by things, as are the degrees of light and dark. Things appear to us as closer or more distant in the infinite vastness of illuminated space. We can wander within this space with our eyes, and that – even more than the concrete possibility of moving, which also exists in the darkness – gives us the feeling of being in space. (Böhme Citation2017, 200)

Light not only enables the perception of space, but also allows the perceiving subject to find himself or herself “topographically situated” within space. Both are qualities that are important for the production and reception of atmospheres. According to Böhme, atmosphere is “something that proceeds from and is created by things, persons, or their constellations;” it is a shared “reality of the perceived as the sphere of its presence and the reality of the perceiver, insofar as in sensing the atmosphere s/he is bodily present in a certain way” (Böhme Citation2017, 19–20). For Böhme, light and illumination (but also sound, images, and the structure of a specific space) are all important factors in the production and reception of atmosphere.

An application of such knowledge of the atmospheric capacities of light and illumination can be seen in practices of stage design and stage lighting. In the case of Lakewood Church’s worship services, the use of artificial light similar to theatre lighting is central, as the auditorium does not have access to natural light via windows. In staged performances, light is one of the theatrical elements used for dramatic effect, for the creation of atmosphere, and the stimulation of audience perception.

The French dramatist Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) was one of the early pioneers who systematically thought about how light could be employed to create a more immersive experience for theatre audiences. He suggested using “light which is not created merely to add colour or to brighten, and which brings its power, influence, suggestions with it” (Artaud Citation1958, 81–82). Artaud acknowledged the sensual impact of light especially in combination with sound on the spectator and regarded those theatrical elements as capable of creating a “vibratory sensual experience” that could impact the human body (Palmer Citation2013, 39). Artaud also lamented the out-dated technology of early 20th century stage lighting, which he saw as incapable of achieving such multi-sensory, immersive effects (Artaud Citation1958, 95; Palmer 203, 40). Since then, a technological revolution has happened in theatre and performance lighting and the analysis of the Lakewood Church case study will show that the creators and worship leaders of contemporary megachurch services consciously employ the latest technologies in order to harness the dramatic quality of light to create multi-sensory experiences for worship attendees (Emling and Rakow Citation2014; Stevenson Citation2013).

Theatre and performance studies differentiate between light and lighting. Light is the material substance that illuminates the stage or performance area and renders the space, people, and things in it visible. It not only illuminates spaces, but shapes the perception of architectural features and how space is perceived. Light is the result of lighting technologies and it is employed to produce dramatic effects. Lighting refers to the technologies, techniques, and processes used to create light on stage or in a performative space (Palmer Citation2013, xiv; Fischer-Lichte Citation1992, 110). In performance lighting, light has two functions: a practical and a symbolical function. In its practical capacity, light illuminates space and makes things visible. In its symbolic function, it works as a “theatrical sign” signifying first and foremost ‘light’ albeit in different qualities (i.e. daylight, candle light, moonlight, etc.). What these different forms of light connote depends on the specific context of the play and the perceiving audience (Fischer-Lichte Citation1992, 110–114). As mentioned in the introduction, in Evangelical discourse and practice, light is associated with the forgiveness of sin, salvation, and eternal life. The use of light in a megachurch service might thus be used not only to illuminate the space, but also to convey moods and ideas related to the Evangelical message of salvation.

We can regard the megachurch auditorium in which the worship services are conducted as a performative space. The performative space connects the actors on stage (in our case the pastors, worship leaders, musicians, and the choir) with the audience. Worship attendees are not passive spectators, but active participants in the events. They literally move along with the liturgical rhythm of standing, sitting, and praying. In addition, worshippers dance or sway to the rhythm of the music, clap hands, and sing along. They pray intensely in silence or with audible murmurs and shout responses, such as “Jesus,” “Hallelujah” or “Amen.” The theatre scholar Erika Fischer-Lichte states that a performative space is always also an “atmospheric space” (2008, 114). Referring to Gernot Böhme’s earlier mentioned idea of atmospheres as something co-created by constellations of things and people, she argues that “the spectators are not positioned opposite to or outside the atmosphere; they are enclosed by and steeped in it” (Fischer-Lichte Citation2008, 116). In atmospheric spaces, audiences “become aware of their own corporeality” and “experience themselves as living organisms involved in an exchange with their environments. The atmosphere enters their bodies and breaks down their limits” (Fischer-Lichte Citation2008, 120).2 The immersive quality of the atmospheric space turns it into a “liminal space of transformation” (Fischer-Lichte Citation2008, 120). Following Fischer-Lichte, we can regard the sanctuary of a megachurch as the performative space of worship through which an atmospheric, transformative space is created, which attunes the senses of attendees and prepares believers for the experience of or encounter with divine presence.

Several elements stimulating the human sensorium such as light, sound, and smell can contribute to the creation of atmosphere, and as such they are consciously employed for performances (may these be theatre plays or worship services). The two interesting elements for our case study are light and sound. Both take the form of transient, ephemeral waves perceived not only by the eyes and ears, but also felt by the body and absorbed through the skin (Fischer-Lichte Citation2008, 119; Howes Citation2011). Or as Adolphe Appia, another early theorist of stage lighting, wrote already in 1908: “The centre where sound waves, on the one hand (through rhythm), and light beams, on the other (through plasticity) converge, is the human body (Appia quoted in Palmer Citation2013, 80). The sensing body of the worship attendee is thus the site where the effects of an Evangelical dramaturgy might unfold and contribute to the embodiment of belief.

The Transformation of Space: From Stadium to Sanctuary

With an average weekly attendance of 45,000 worshippers, Lakewood Church is currently the largest megachurch in the US. What began in 1959 as a small Baptist storefront church influenced by the mid-century charismatic revivals has grown into one of the largest congregations in North America (Sinitiere Citation2015, 27). Part of the success story of Lakewood Church’s exceptional growth is its prominent role within the Word of Faith movement, its prosperity theology, and the success of its TV ministry founded in the 1980s under then senior pastor John Osteen (Young Citation2007, 71–72; Sinitiere Citation2011, 5). Since 1999, when his son Joel Osteen took over, the church’s size has almost quadrupled. Joel Osteen, often dubbed “the smiling preacher”, has become one of the most recognizable TV pastors and a bestselling author of Christian advice books (Rakow Citation2015; Sinitiere Citation2015). All of those factors combined turned Lakewood Church into a household name in American Evangelical and neo-Pentecostal circles. Over the years, the church moved into ever-larger worship spaces while outgrowing them fast. In 2003, Lakewood Church signed a 30-year lease with Houston’s city council to rent the Compaq Center, the former Basketball arena and home of the Houston Rockets, on the condition that they renovate the sport stadium at their own expense. The renovation project cost more than 90 million dollars, turning the former sports stadium into a 16,000-seat sanctuary for the congregation and a state-of-the-art production stage for Lakewood’s TV ministry (Lee and Sinitiere Citation2009, 35).

The arena of the former sports stadium was extensively rebuilt and adapted to the needs of a megachurch, which produces its own televangelist program. Lakewood Church commissioned various companies to plan and implement the conversion of the space and the accompanying installation of the light, sound, video, and camera systems (Eddy Citation2005; Istnick Citation2006; Martof Citation2005; McDonough Citation2013). According to the Technologies For Worship Magazine, one of the many case studies about the Lakewood Church renovation project that appeared in technical journals, Lakewood Church aimed for an intimate atmosphere despite the huge space:

What began as a cavernous, acoustical nightmare known as the former Compaq Center, Lakewood has evolved into a state of the art worship space. Lakewood wanted every member of the congregation to be able to intimately experience Pastor Joel Osteen’s message. The question was—how could you make a thunderous basketball arena into an intimate place to worship the Lord? (Cobus Citation2005)

The arena had to be insulated in order to guarantee good sound quality throughout the entire space for both, the musical and spoken performance as well as the TV recordings. The lowest level of the arena, which formerly housed the playing field, was converted into a large stage in the front part and provided with slightly rising rows of seats in the rest of the area. According to another report on the Lakewood Church project published by LifeDesignOnline.com, a web-based resource for live entertainment professionals in lighting, sound, staging, and projection, the installation of tiered rows of seats changed the structure of the space entirely. It eliminated the character of the sports arena and created a place of worship (Eddy Citation2005). The entire auditorium is carpeted and now comprises 16,000 upholstered seats spread over three levels. The large stage forms the visual centre of the enormous space and can be seen from all three levels. In addition, three large LED screens are mounted above the stage so that the events can also be followed closely from further away.

The technical equipment of the worship space and the design of the stage fulfil a double function: they are meant to enable a certain worship experience while simultaneously facilitating the high-end production of a television program. René Lagler, an Emmy awarded set designer for television productions was commissioned to design a stage suitable for both live performances and television recordings. The new stage is framed by two artificial waterfalls flowing over a rocky landscape adorned with green plants. A sky-blue LED curtain forms the stage background and hides another large screen on which images can be projected during the service (McDonough Citation2013). A large golden globe representing the earth is positioned in front of the LED curtain on a lowerable platform. It is the visual centrepiece of the empty stage. During worship service, the golden globe slowly spins and builds the backdrop to singers and pastors on stage (Eddy Citation2005). In front of the globe is a hydraulic trench for the orchestra and the band, which can also be lowered or raised as required. Two tiered platforms flank the globe and offer space for the choir. Screens behind the two choir sections usually show a blue sky with fluffy white clouds (). The free front stage section, the orchestra pit and the globe in the back part of the stage have made it possible to achieve a depth of space that has a beneficial effect on the quality of the television recordings (Eddy Citation2005). Two permanently installed high-definition cameras in the auditorium primarily take close-ups of the stage and Joel Osteen during his sermon. In addition, three cameras circle over the audience and above the stage on pivoting arms and another three camera operators with mobile cameras move through the auditorium to take close-ups of mainly emotional reactions from the audience (Istnick Citation2006, 18). The in-house media production centre situated on the fifth floor of the building processes the images from all cameras not only for the TV program, but also simultaneously switches these onto the LED screens in the auditorium.

Lighting Technologies at Lakewood Church

Given the architectural features of a former sports stadium and the intended double functionality of the renovated worship space cum TV set, it might not surprise that Lakewood Church and its technical consultants deviated from traditional church lighting schemes and took inspiration from theatre and television production sets. Tom Stanziano, then director of the Lighting Ministry at Lakewood Church (i.e. the team responsible for lighting during worship services), worked with Emmy awarded lighting designer Bill Klages (NewKlages Inc.) and Studio Red Architects (the lead architects in the Lakewood Church renovation project) in developing and realizing the lighting strategy for the new auditorium.

Lakewood Church installed professional lighting systems including catwalks above the stage, which are usually used in large theatre and television productions. The catwalks provide the infrastructure to mount, access, and position various lights and spots that provide an elaborate lighting system for the various stage sections. The stage lights were chosen according to their correct colour temperature, intensity, exposure level, and spread. Mobile spotlights with adjustable shutters provide photogenic light for the pastor, the choir, and the musicians on stage. They enable close-ups in portrait quality while gentle fill lights mounted on the side trusses provide soft light spilling from the stage into the first rows of the audience (Eddy Citation2005).

In addition to stage lights, the audience lighting provided another challenge. The lights needed to provide enough exposure for the cameras to capture not only the stage area, but also to give the viewers in front of a TV screen an idea of the size of the congregation as well as a sense for the space of the auditorium without producing too much glare that would result in discomfort for the congregation. After all, the auditorium was not only a TV Ministry production set, but also a sanctuary meant for worship. The strategy chosen for the Lakewood Church auditorium was to use downlights for the audience section and an elaborate colour-changing LED covered ceiling inspired by a similar construction used in Cirque du Soleil’s “O”. Both strategies were intended to have a positive effect on the worship experience for those present as well as for the spectators in front of the screen (Istnick Citation2006, 20). The new overhead ceiling lighting not only covered the old catwalk system of the former sports arena and hid the roof construction from view; it also produced a surreal visual effect of coloured clouds. One might feel reminded of classical paintings of sky and clouds on church ceilings, which here are realized in a modern, LED-rendered interpretation of a sky. The colour cloud effect resulted from wire mash materials illuminated with Philips Color Kinetics LED lights draped over a series of 40-foot squares (). The construction and its effect are described as “immersive megachurch lighting” in a brochure on “LED Lighting for Worship” produced by Philips Solid-State Lighting Solutions, Inc (Citation2010).

FIG 2 Colour cloud ceiling illuminated in purple hues at Lakewood Church during worship phase. Photo by the author, 2012.

Statements from the lighting designer, the director of Lakewood Church’s Lighting Ministry, and light fixtures producing companies show an awareness for the importance of light in creating atmosphere, evoking moods and thus supporting the communicated message – be it in a theatre performance, TV production or a church service. In advertising their lighting solutions to churches of varying size, a Philips brochure states, “regardless of your approach to worship, you need a lighting style that supports your worship style. Effective lighting focuses attention, creates appropriate mood and atmosphere, communicates meaning, and engages the audience” (Philips Solid-State Lighting Solutions, Inc Citation2010, 3). Echoing Philips’s view of the role of lighting to induce moods and emotions during worship services, Bill Klages describes the objective of Lakewood Church’s exclusive lighting design as follows:

In a departure from traditional Church lighting schemes, it was my opinion that the excitement of this [worship music] section could only be captured for both within the Sanctuary and by the Television camera by making the lighting as specific and, as a result, as theatrical as possible. This approach insures that both the live Congregation as well as the TV viewer have similar emotional responses to the performance. (New Klages Inc., Entertainment Lighting Facilities Design and Television Lighting Design, n. d.)

Lakewood Church’s sanctuary is equipped with various lighting systems comprising more than 600 lights and spotlights. By changing the lighting, different atmospheres can be generated in the room, which at the same time provide sufficient light for TV shots. This ensures that the viewer in front of the screen also gets an impression of the size of the room and the abundance of participants (Eddy Citation2005). In the default light scheme at Lakewood Church, the LED curtain at the back of the stage and the colour cloud ceiling above are illuminated in sky blue while the other lights wash the stage and the auditorium in bright light giving the impression of daylight or sunlight (). It is also the lighting style used for Joel Osteen’s sermon in the latter half of the service.

FIG 3 Lakewood Church auditorium in default light mode with stage and colour cloud ceiling in sky-blue. Photo by the author, 2012.

In general, the lights can be orchestrated, dimmed, and changed in colour in tune with the liturgical structure and the Evangelical dramaturgy of the worship service, especially during the praise and worship part in the first half of a typical Lakewood Church service. Tom Stanziano describes his work as lighting director in an interview with Technologies for Worship Magazine as follows:

We have a song list that is produced at the beginning of the week and then it gets sent to all to the production department. During the week I listen to the different songs to get a feel for the atmosphere that they’re trying to create. Thursday and Friday I’ll sit down with the CD and program to the music. Basically each song has a custom design using a GrandMA lighting console. (Cobus and Stanziano Citation2014)

It is especially the custom design lighting for each song that helps to structure the events on stage and guide the audience along by providing visual cues indicating the praise and worship phases of the service as the next section will show. The lighting design thus supports the creation of an immersive atmosphere in “multisensory services” that equally address the senses, the body, the spirit, and the emotions of the participants (Spinks Citation2010, 63).

Immersive Lighting at Lakewood Church Worship Services

The technical equipment of the auditorium supports the consciously sequenced design of the worship service aimed at providing the visitor with a multi-sensory experience. A typical worship service at Lakewood Church consists of several parts. The first song starts off the church service, followed by a brief welcome message of the pastor couple Victoria and Joel Osteen. The praise music phase is followed by the worship music phase, which blends into a prayer session. A musical interlude signals the next part of the service: a brief message delivered by Victoria Osteen and the invitation to give. After the tithe, Joel Osteen enters the stage and delivers his message, which usually ends with an altar call and a prayer. A last song concludes the worship service.

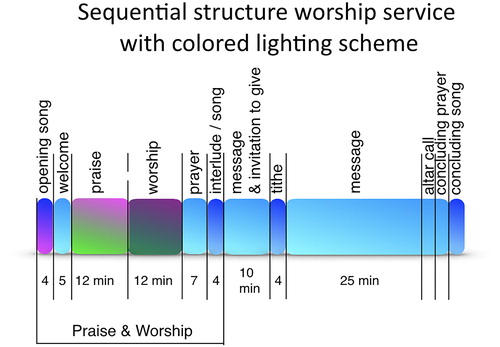

Lakewood Church uses a customized light design with changing colours in the musical parts of the church service (first song, praise, worship, interlude, and conclusion song). For all speaking parts (welcome, prayer, short message, main message, altar call), the church uses the default lighting scheme with sky-blue LED-curtain and colour clouds while bright lights illuminate the stage and auditorium. The sequential structure of the worship service and the accompanying colour scheme is indicated in .

FIG 4 Sequential structure of worship services at Lakewood Church with accompanying colour scheme. Illustration by the author, 2019.

In the following section, I will focus on the first parts of the worship service that is the praise and worship parts and the transition into prayer, which employ customized colourful light designs morphing into the default sky-blue lighting scheme during the prayer phase.3 In Evangelical circles, praise and worship of God through music, song, dance, and prayer include a horizontal and a vertical level, which are consciously taken into account in the musical design of a contemporary worship service: praise music addresses the horizontal level on which the participants of the worship service share and express their praise for the work of God together; worship music creates the vertical level on which the individual communicates with God (Kauflin Citation2008, 175–179). The praise phase precedes worship and is seen as a door opener for the encounter with God (Liesch Citation2001, 61; Sorge Citation2001, 67–68). At the same time, the first part serves to attune the participants to the sermon and to ensure that the message has a maximum effect on the listener (Marti Citation2012, 106). As we will see, the horizontal and vertical levels are not only created through sound, but also by the employed lighting design.

The Praise Phase: Bright Lights and Colours

The praise phase is characterized by fast, upbeat music that invites the congregation to clap their hands, dance along, and sing their praises. The auditorium of Lakewood Church is relatively brightly lit while worship leaders and audience are singing,

oh clap your hands/all ye people and shout unto God/with a voice of triumph/whoa-ooh-oh/you are the everlasting God/shine your light to us for all the world to see/You are the hope of broken hearts/Overcame the grave/To save humanity/We’re singing/Halleluiah/Jesus is alive… (Houghton & New Breed Citation2012)

The stage and artificial sky appear in bright, rich colour tones of light blue, orange, red or green. Often the LED curtain at the stage background and the colour clouds on the ceiling are illuminated in corresponding hues. The coloured lights and their brightness allow the participants not only to see the singers, musicians, and choir on stage but also their fellow worshippers in the huge auditorium. As Böhme suggested, the lightness of the auditorium allows the participants to find themselves literally “topographically situated” within the space of the auditorium and thus as part of a large assembled congregation. As such, the bright lights support the horizontal dimension of the praise phase, which emphasizes the communal aspect of the congregation. The community can see each other in the act of giving praise together which finds its expression in enthusiastic worship styles such as standing, swaying, dancing, clapping hands, singing along, or shouting ( and ). The communal aspect is also mirrored in many praise song lyrics that often employ first person plural pronouns (we, us), thus also emphasizing the community of believers. The praise phase at Lakewood Church lasts on average 20 minutes during which usually four praise songs including the opening song are performed.

FIG 5 Auditorium and stage brightly illuminated in blue colours during praise phase of the worship service. Photo by the author, 2011.

FIG 6. Auditorium and stage brightly illuminated in red colours during praise phase of the worship service. Photo by the author, 2012.

FIG 7 Toned down colours during worship phase with image projection as light source on stage. Photo by the author, 2012.

The Worship Phase: Darkness and Sparse Illumination

At the point when the last notes of the fourth praise song fade away, the lights on stage take on darker hues with less illumination while the golden globe is slowly lowered into the ground thus disappearing from sight. Simultaneously, the LED curtain at the background of the stage opens and reveals another large screen while the downlights in the auditorium are dimmed. The changes in the lighting scheme and the stage decoration indicate the transition into the worship phase of the service. The auditorium becomes comparatively dark in contrast with the praise phase. The stage and ceiling lights shimmer only in muted, rather dark colours of blue, green, and purple. From the auditorium, the events on stage are still clearly visible, while the visibility in the auditorium itself has almost gone except for the first rows illuminated by the lights spilling from the stage. The swaying, dancing and clapping of hands ceases and thus the noise previously produced by the audience during the praise phase is now significantly reduced. Although one is still aware of others in the audience, first and foremost the worshippers right next to one’s own seat, at times, it is almost impossible to recognize individual faces. The singers and musicians on stage perform slow songs, often in the style of ballads with lyrics focusing on Jesus’ death at the cross, the gift of eternal life, as well as on intimacy and closeness to God. As Victoria Osteen expressed it in one of her welcome messages, “Let’s truly believe that we are going to enter into His presence and that in His presence is fullness of whatever we need.” (worship service March 15, 2012, fieldnotes of the author). The darkened auditorium and the slow rhythm of the music invite the participants to enter into God’s presence by closing their eyes, raising their open hands towards the sky, and being consumed by the affective atmosphere while singing:

You are light, You are light/When the darkness closes in/You are hope, You are hope/You have covered all my sin/You are peace, You are peace/When my fear is crippling/You are true, You are true/Even in my wandering/You are joy, You are joy/You’re the reason that I sing/You are life, You are life/In You death has lost its sting/I’m running to Your arms/I’m running to Your arms/The riches of Your love/Will always be enough/Nothing compares to Your embrace/Light of the world forever reign (Hillsong United Citation2010)

The outlines of the many raised hands (the typical worship position of Evangelical and charismatic Christians) are barely visible in the darkened auditorium. The scarce illumination that turns the assembled worshippers into a rather indistinct dark mass supports the vertical dimension of the worship phase, which emphasizes the individual personal relation between a believer and God through Jesus Christ. The lyrics of many worship songs focus on this vertical relation usually expressed through the use of the first person singular (I, my). The darkened space of the auditorium, the toned down lights and colours of the stage performance, the slow emotional ballads, the body postures of the worship leaders (e.g. raised hands, temporarily closed eyes, a hand placed over their hearts) and the lyrics thus support each other in fostering an atmosphere of closeness and intimacy between believer and God where the rest of the congregation temporarily disappears from view and awareness.

As mentioned earlier, crucicentrism is one of the characteristics of Evangelicalism (Bebbington Citation1993). Thus, at least one song of the worship phase focuses explicitly on Christ’s death at the cross through which mankind was freed from sin and death overcome. The large screen behind the singers and musicians usually hidden by the golden globe and the LED curtain displays corresponding images of Jesus, the three crosses on Calvary, and similar motifs ( and ).4 While the auditorium is submerged in relative darkness, the projected images become a source of light and shine bright from the stage albeit depicted in toned down colours. The light of the images spills from the stage into the first rows of the auditorium and creates an effect comparable to rays of sunlight falling through a stained glass window and sparsely illuminating a dark church nave. Shining from the screen, images of the crucified Christ lighten the stage and the dark auditorium. The image of Jesus literally becomes the light, the ‘light of the world’ that momentarily reigns over the worship attendees present in the sanctuary of Lakewood Church (Hillsong United Citation2010; John 8:12 NIV).

From Worship to Prayer: The Sunrise Effect

The worship phase usually lasts for 12 minutes in which the singers and musicians perform three songs. Towards the end of the third worship song, Joel Osteen enters the stage. With the fading of the song, the light slowly returns and the golden globe re-emerges on stage. While Osteen is praying aloud with closed eyes and outstretched arms, the LED curtain moves back into place illuminated it its default colour sky-blue. Bright lights shine onto the waterfalls flanking the stage and the images of blue skies with fluffy white clouds are displayed again behind the choir sections while the overall light in the auditorium slowly increases. A minute into Osteen’s prayer, the sanctuary is illuminated in bright light and the colour cloud ceiling in sky-blue (). The timing and effect of the slowly increasing light are reminiscent of a sunrise; the sun illuminating the world again after the darkness of the night. Here too, the light corresponds to the message: while the worship lyrics and images in the previous section revolved around Christ’s atoning work at the cross, the return of the light signals what is bought through Christ’s sacrifice: light, hope, peace, joy, and life. It tallies perfectly with Osteen’s “message of hope” conveyed in his prayers, sermons, and books (Rakow Citation2015). By literally moving through the darkness, believers are reminded of Christ’s saving work through lyrical, visual, tonal, and emotional cues. In the moments of darkened intimacy, the believer can renew, nourish, and strengthen her personal relationship with God and then, at the end of the passage, literally emerges into the light again while Osteen prays for health, success, victory, and prosperity as promised by God to faithful believers (Rakow Citation2015; Sinitiere Citation2015).

Atmosphere as a Mediating Strategy

What I have described above was the typical liturgical structure and the accompanying lighting scheme of the English-peaking worship services at Lakewood Church on Wednesday evenings, Saturday evenings, and Sunday mornings during my fieldwork period. Lakewood Church’s worship leaders (i.e. musicians) and the light ministry team consciously aim for a certain worship service atmosphere—joyous and celebratory during the praise phase, more toned down and intimate during the worship phase, and full of brightness during Osteen’s prayer and “message of hope” (Rakow Citation2015). The intentional production of a specific atmosphere does not necessarily mean that it is experienced in the intended way by every attendee or spectator. I suggest to think of atmosphere as a communicative offer to which worship attendees might respond in various ways and intensities of immersion or not respond at all. We can speak of an “affective atmosphere” – to use Jill Stevenson’s term (2013, 162)5 – for those participants who feel indeed enveloped, steeped or immersed by it, i.e. when the created atmosphere actually resonates with the audience and thus affects participants. The majority of attendees exhibits a visible enthusiasm to move along with the liturgical structure of the Evangelical dramaturgy, which means that their worship practices are joyous and exuberant (i.e. visibly swaying/dancing, singing, clapping hands), toned down and intimate (i.e. prayer position, closed eyes, moving lips, tears), and affirmative during Osteen’s prayer (enthusiastic and audible responses shouting “Amen!” or “Hallelujah!”). Such active participation and reactions show an openness to be enveloped by the atmosphere. Occasionally, one sees individual attendees briefly tuning out the service, checking their phone, texting or briefly chatting with their neighbours although the volume of the musical performance is too high to keep a longer conversation flowing. But overall, the atmosphere seems compelling for many attendees, easily drawing worshippers into actively participating in the praise, worship, and prayer phases. Martin Radermacher speaks of atmospheres as

“the realized semantic potential of socio-spatial arrangements. It means that socio-spatial arrangements (i.e. built spaces of social practice) in principle enable a multitude of meaningful connections, but in concrete social situations a specific semantic framework is evoked, which is sometimes explicitly called atmosphere by actors in the field, but in any case is implicitly effective as atmosphere.” (Radermacher Citation2018, 143–144, translation by the author).

Following Radermacher’s suggestion to regard atmospheres as “the realized semantic potential of socio-spatial arrangements” which evoke a “specific semantic framework”, we can regard Lakewood Church’s worship services and the use of light, sound, space, and performance as an intentional creation of an affective atmosphere meant to evoke a specific Evangelical and neo-Pentecostal semantic framework. Such a framework is expressed through an “Evangelical dramaturgy” in order to create an affective atmosphere enabling “meaningful connections” for the worship attendees, e.g. joyous, celebratory feelings or feelings of closeness or intimacy with God (Stevenson Citation2013, 20; Radermacher Citation2018, 143–144).

Unlike a visit to a theatrical performance (which is in most cases an unique event), attending a worship service is usually a repeated activity. Each time, new and first time visitors are present at Lakewood Church, but the majority of attendees does participate in worship services on a more or less regular basis. Repeated participation allows for a growing familiarity with the sequential structure of the worship service, the accompanying practices, body postures, and moods. Praise, worship, and prayer are learned practices. Through repeated participation, worship services and their particular atmospheres foster, inculcate, and support the embodied dispositions of an Evangelical or neo-Pentecostal habitus, which enables participants to respond to the lyrical, visual, tonal, and emotional cues employed during a worship service.

These multi-sensory worship services with their horizontal level of connecting with fellow worshippers and the vertical level of connecting with the divine are what Birgit Meyer calls a “sensational form” that mediates divine presence by rendering it sensible to the worshippers. She defines sensational forms as,

relatively fixed, authorized modes of invoking and organizing access to the transcendental, thereby creating and sustaining links between religious practitioners in the context of particular religious organizations. Sensational forms are transmitted and shared; they involve religious practitioners in particular practices of worship and play a central role in forming religious subjects. (Meyer Citation2008, 707).

The sensational form of multi-sensory worships services creates synesthetic experiences that activate and engage the body and affects of participants. The Evangelical dramaturgy supported by elaborate light and sound systems mediates divine presence by stimulating emotions and preparing the individual to anticipate feelings of closeness to God while simultaneously embodying and reinforcing specific theological concepts and epistemological assumptions within believers (i.e. crucicentrism, a personal relationship with God through Jesus Christ, God’s supernatural power, etc.).

Conclusion

With the support of light and sound technologies, Lakewood Church creates a performative and thus atmospheric space for worship in which the congregation and the individual believers can praise God, pray to Him and feel themselves in His presence. The arrangement of space, people, lights, colours, images, sounds, and words of Evangelical worship services together create the typical affective atmosphere found in Lakewood Church services. As we saw, light played a significant role in adding “aesthetic texture” to the multi-sensory worship experience (Stevenson Citation2013, 24). Light in its practical function was employed to illuminate the space and the events on stage, but also as a theatrical sign to connote Jesus, eternal live, and salvation in order to support an Evangelical message conveyed through the various elements of the worship service. The play of lightness and darkness in the custom lighting design for the different parts of Lakewood Church services influences the perception of space in the sanctuary. Bright lights and clear visibility heighten the sense of space and increase the awareness of the grandeur of the assembled congregation. Seeing oneself among the assembled worshippers emphasizes the horizontal or communal aspect of the worship service, where fellow Christians come together to praise God. In contrast, reduced visibility and sparse illumination reduce the sense of space, shrink the spaciousness of the auditorium to one’s immediate surroundings and thus help to temporarily blind out a large part of the congregation. The darkened auditorium space and the toned down colours of the stage lights facilitate feelings of intimacy or closeness to God and thus emphasize the individual or vertical aspect of the worship service where the personal relationship between a believer and God is central. Lakewood Church’s lighting scheme helps to transform the auditorium from a capacious meeting space for the congregation into an intimate space of individual religious worship and vice versa.

Anne Loveland and Otis Wheeler have observed similar effects from megachurch sound systems. Such electronic sound systems can emulate the acoustical capaciousness of a cathedral and thus make a space “sound larger”, while they also have the capacity to make a large auditorium “sound smaller” during spoken performances (Loveland and Wheeler Citation2003, 232–233). The interplay of light and sound are thus crucial performative elements for the creation and transformation of different worship spaces within the same auditorium, which simultaneously is able to serve as a meeting space for the congregation and as an intimate place for a personal encounter with God.

In the context of Lakewood Church worship services, artificial light is neither a purely practical necessity to produce visibility in the sanctuary, nor is light primarily meant as a metaphor for Jesus, eternal life and salvation. Light technologies, lighting schemes, and the resulting light effects are a consciously and intentionally used strategy for the creation of a specific worship atmosphere. Within the Evangelical dramaturgy of worship services at Lakewood Church light might function as a theatrical sign invoking a certain symbolism, but it first and foremost is used as medium to mediate divine presence.

notes and references

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katja Rakow

Katja Rakow is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies of Utrecht University, The Netherlands. Her research focuses on megachurches in the US and Singapore with a special interest in material religion, technology, and the transcultural dynamics of religious practices and discourses.[email protected]

Notes

1 The analysis is based on fieldwork data acquired on site and textual data drawn from case study reports and portfolios of the technological companies and designers involved in the reconstruction and outfitting of the church auditorium. The data was acquired during two periods of fieldwork, the first between February and March 2011, the second between February and April 2012. The postdoctoral research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the larger research project “Modern Religious Experience Worlds” at Heidelberg University, Germany, 2010-2013.

2 Although Gernot Böhme speaks of atmospheres as a quality of space more generally, Fischer-Lichte here specifically refers to performative spaces, which for her are always also atmospheric spaces. She does not speak of space as such as not all spaces are characterized by spectators or audiences.

3 The examples mentioned in this section are taken from my fieldnotes from a worship service on March 25, 2012, at 8.30 a.m., which was a very typical Sunday worship service at Lakewood Church.

4 The use of images might surprise, but to my experience and observations at three large megachurches in the US, Singapore, and Australia, neo-Pentecostal megachurches with large media ministries often seem to have a relaxed attitude towards the use of images although a certain limited range of motifs is observable. The used images – if projected on LED screens during worship services or displayed in other printed or digital media formats – are usually limited to depictions of Jesus, the crucifixion, crosses, or Calvary and thus mediating the centrality of Evangelicalism’s crucicentrism. Depictions of nature, believers or scenes from their daily Christian life (baptism, prayer, Bible study, or situations of fellowshipping) are another range of images often used in Evangelical or neo-Pentecostal contexts.

5 Stevenson uses the term “affective atmosphere” without further developing this idea on a conceptual level.

- Artaud, Antonin. 1958. The Theatre and Its Double. Translated by Mary Caroline Richards. New York: Grove Press.

- Bebbington, David. 1993. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. London: Routledge.

- Böhme, Gernot. 2017. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, edited by Jean-Paul Thibaud. London: Routledge.

- Cobus, Kevin Rogers. 2005. “Lakewood Church: From Stadium to Sanctuary.” Technologies for Worship Magazine, October 2005. https://tfwm.com/lakewood-church-from-stadium-to-sanctuary/.

- Cobus, Kevin Rogers, and Tom Stanziano. 2014. “Lakewood Church: Interview with LD Tom Stanziano.” Technologies for Worship Magazine, February 26. http://tfwm.com/lakewood-church-interview-with-ld-tom-stanziano/.

- Eddy, Michael S. 2005. “Slam Dunk: Lakewood Church.” LiveDesignOnline, October 1. https://www.livedesignonline.com/mag/slam-dunk-lakewood-church.

- Emling, Sebastian, and Katja Rakow. 2014. Moderne religiöse Erlebniswelten in den USA: “Have Fun and Prepare to Believe! Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 1992. The Semiotics of Theater. Advances in Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2008. The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Hillsong United. 2010. “Forever Reign.” A Beautiful Exchange. Sydney: Hillsong Music Australia.

- Hitzer, Bettina, and Monique Scheer. 2014. “Unholy Feelings: Questioning Evangelical Emotions in Wilhelmine Germany.” German History 32 (3): 371–392. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghu061

- Houghton, Israel, and New Breed. 2012. “Rez Power.” Jesus at the Center. New York: Columbia Records. doi:10.15420/icr.2007.49

- Howes, David. 2011. “Sensation.” Material Religion 7 (1): 92–98. doi:10.2752/175183411X12968355482178

- Istnick, Alison. 2006. “Lakewood Church Part II: Walking the Line between Live and Broadcast.” Church Production Magazine, Jan./Feb. (2006): 17–20.

- Kauflin, Bob. 2008. Worship Matters. Leading Others to Encounter the Greatness of God. Wheaton: Crossway Books.

- Klages, Bill. (n.d.) “Lakewood Church – Houston, Texas. Notes by Bill Klages.” New Klages Inc., Entertainment Lighting Facilities Design and Television Lighting Design. Accessed July 16, 2019. http://www.newklages.com/NKI_lakewood.htm.

- Lee, Shayne, and Phillip Luke Sinitiere. 2009. Holy Mavericks: Evangelical Innovators and the Spiritual Marketplace. New York, London: New York University Press.

- Liesch, Barry. 2001. The New Worship: Straight Talk on Music and the Church. Grand Rapids: BakerBooks.

- Loveland, Anne C., and Otis B. Wheeler. 2003. From Meetinghouse to Megachurch: A Material and Cultural History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. doi:10.1086/ahr/110.1.124

- Luhrmann, Tanya M. 2004. “Metakinesis: How God Becomes Intimate in Contemporary U.S. Christianity.” American Anthropologist 106 (3): 518–528. doi:10.1525/aa.2004.106.3.518

- Marti, Gerardo. 2012. Worship across the Racial Divide: Religious Music and the Multiracial Congregation. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Martof, Mark. 2005. “Technologies for Worship Reach New Heights at Lakewood Church.” Technologies for Worship Magazine, March 2005. https://tfwm.com/technologies-for-worship-reach-new-heights-at-lakewood-church/.

- McDonough, Andy. 2013. “Case Study: Inside Houston’s Lakewood Church: Teamwork Drives an Audio Upgrade in the Nation’s Largest Sanctuary.” Church Production, March 29, 2013. http://www.churchproduction.com/story/main/inside-houstons-lakewood-church.

- Meyer, Birgit. 2008. “Religious Sensations: Why Media, Aesthetics, and Power Matter in the Study of Contemporary Religion.” In Religion: Beyond a Concept, edited by Hent de Vries, 704–723. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Palmer, Scott. 2013. Light. (Readings in Theatre Practice). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Philips Solid-State Lighting Solutions, Inc. 2010. LED Lighting for Worship: Philips Color Kinetics.” Burlington, Mass: Philips Solid-State Lighting Solutions, Inc.

- Radermacher, Martin. 2018. “Atmosphäre’: Zum Potential eines Konzepts für die Religionswissenschaft.” Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft 16 (1): 142–194. doi:10.1515/zfr-2017-0018

- Rakow, Katja. 2015. “Religious Branding and the Quest to Meet Consumer Needs: Joel Osteen’s ‘Message of Hope.” In Religion and the Marketplace in the United States, edited by Jan Stievermann, Philip Goff, Detlef Junker, Anthony Santoro, and Daniel Silliman, 215–239. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, Leigh Eric. 2000. Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Sinitiere, Phillip Luke. 2011. “From the Oasis of Love to Your Best Life Now: A Brief History of Lakewood Church.” Houston History 8 (3): 2–9.

- Sinitiere, Phillip Luke. 2015. Salvation with a Smile: Joel Osteen, Lakewood Church, and American Christianity. New York: New York University Press.

- Sorge, Bob. 2001. Exploring Worship. A Practical Guide to Praise & Worship. Kansas City: Oasis House.

- Spinks, Bryan D. 2010. The Worship Mall: Contemporary Responses to Contemporary Culture. London: SPCK Publishing.

- Stevenson, Jill. 2013. Sensational Devotion: Evangelical Performance in Twenty-First Century America. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Young, Richard. 2007. The Rise of Lakewood Church and Joel Osteen. New Kensington: Whitaker House.