The Tropenmuseum’s exhibition Longing for Mecca, on the Islamic pilgrimage, the Hajj, presents visitors with both a historical and a contemporary view of one of the world’s greatest religious rituals. This exhibition is based on the 2012 Hajj: journey to the heart of Islam at the British Museum, was subsequently adapted for a Dutch audience in 2013, and put on display at the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden. The Tropenmuseum’s improved version of the exhibition underscores the global diversity of Islam, while focusing on Dutch Muslims and the Dutch colonial past as well.

It comes as no surprise that the museum is keen to attract young people of varied backgrounds. Both the British Museum and the Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, already successfully drew in many Muslim visitors. The Tropenmuseum exhibition, too, has been a stunning success in this respect, being visited by school and university groups, mosque associations, discussed in immigrant neighbourhoods of Dutch suburbia, etc. At the exhibition’s official opening, on Valentine’s Day 2019, the purpose and “mission” of the museum, as it is often labelled, was clarified by director Stijn Schoonderwoerd: bringing people together, defending open-minded thinking, and generating greater tolerance and mutual respect in the Netherlands.

Steering away from strongly politicizing the Hajj is effected by the exhibition’s emphasis on personal spiritual yearnings, choices, and experiences, indicated also by the title. To illustrate these longings, visitors are shown short videos of Dutch Muslims of diverse backgrounds speaking about the Hajj as a matter of “the heart” and of “sincerity.” Simultaneously, the exhibition informs about visual, aural, and tactile atmospheres, objects, and sensations that are part of the Hajj as a collective experience. Especially the variety of objects is organized to demonstrate the “cosmopolitan” – a term used in the exhibition – character of Islam and of Muslims worldwide, who are magnetically drawn to Mecca as a powerful unifying centre. Visitors are informed, against stereotypes that focus on the Arab World, that most pilgrims hail from the Asian continent, from Turkey and Iran to China and Indonesia.

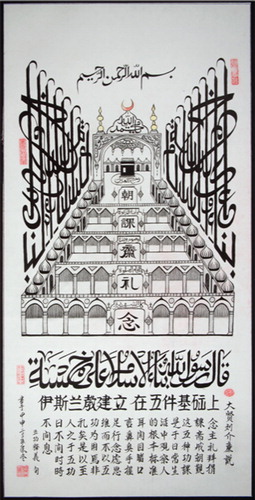

Next to the precious loans from the Khalili Collections, which were also on display in London and Leiden, new acquisitions show Islamic cosmopolitan entanglements, such as a calligraphic composition made by Shi Jie Chen (1925–2006) from Ürümqi, also known as Muhammad Hasan Ibn Yusuf (). This work is striking because it reveals, in an immediate visual way, how Chinese and Arabic text and architectural elements are fused by the artist. The theme is traditional, showing the five pillars of Islam, but in a Sino-Arabic style unknown to many of the museum’s visitors. In fact, when this object was documented, a new category of “Islamic styles and periods – East Asia” had to be created in The Museum System, the digital environment used by curators and other staff, because it was the first of its kind in the Dutch collection.

FIG 1 Shie Jie Chen (Muhammad Hasan Ibn Yusuf). Sino-Arabic calligraphic composition with the theme of the five pillars of Islam. 2005. Ürümqi, China. Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, 7031-3.

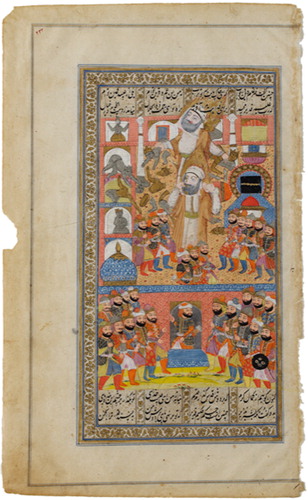

Next to geographic diversity, the displays and accompanying texts make sure to mention other religious differences, that there are mystical strands in Islam, for instance, or by showing a handful of Shi’ite objects. One of these is a miniature painting dated to c. 1800 C.E., made in Kashmir (). The image depicts the Prophet Muhammad carrying his son-and-law and cousin Ali. They are performing an iconoclastic act together, destroying the idols in Mecca, and are honoured by the artist with translucent veils and flaming halos. The image can be said to distinguish the Islamic rejection of worshipping of false Gods from a prohibition to paint human forms. The Persian text, however, alerts us to the fact that in its original context it was not perceived as a potentially problematic image of the Prophet, but as an affirmation of the Shi’ite belief that Ali was his chosen successor.

FIG 2 Miniature painting of the Prophet Muhammad and Ali removing the idols from the Kaaba. Circa 18th century C.E. Kashmir, Mughal Empire. Collection Wereldmuseum, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, WM-68236.

Unfortunately, after choosing this fascinating Mughal artwork for display, the museum placed it alone behind a black screen. Visitors can press a button to switch on a light, but the image’s bright colours and gilded decorations remain blurred by the screen. The accompanying object description transports it from an original historical context to a problem-zone: “opinion has always differed as to whether this [i.e. depicting the Prophet] is permitted.” This strategy of well-meaning caution backfired, and led to the museum receiving complaints from visitors who believed such an image should not be shown at all. The overall impression of the exhibition also remained that of a Sunni Islam of the Five Pillars, the Qur’an, and Islamic Law, even as this was at times combined with other voices, such as during a musical performance, or with the South-Asian miniature painting. By being set apart, such contested practices and objects thus risk becoming the exceptions to a conservative rule. The goals of instrumentalizing such exhibits for promoting social cohesion and in the process not to offend, can stand in tension with showcasing the internal diversity of Islam.

Despite shortcomings, exhibitions such as Longing For Mecca do provoke critical thoughts, by teaching visitors about restrictive Dutch colonial governance policies aimed at controlling Indonesians, or by adding the question to a displayed photograph of a Saudi skyscraper in Mecca under construction: “Is it possible, here in Mecca, where vast amounts of wealth and power are accumulated, to truly achieve spiritual purity and universal equality?” These critical insertions remain modest, so as not to harm the museum’s mission to encourage amicable contact between citizens; it is an achievement in itself to convey something of the beauty of the Hajj to Muslim visitors and the general Dutch public. The challenge will continue to be to cultivate both an open-minded stance towards Mecca and Islamic pluriformity, as well as critical perspectives. Whether and to what extent the desire for intimacy, for some groups and persuasions more than others, has indeed overruled the critical impetus in Longing for Mecca and other similar exhibitions will remain an important conversation topic as we head into the third decade of the twenty-first century.

[email protected]: 10.1080/17432200.2020.1775420