Abstract

Father Damien was a Roman Catholic missionary who lived in Hawai‘i amongst people with leprosy, currently known as Hansen’s disease. He eventually contracted the disease himself and, after his death in 1889, was transformed into the martyred icon (later saint) of Moloka‘i. This paper explores the role of a museum in remembering a missionary saint by focusing on the Damien Museum in Tremelo, Belgium. It does so by focusing on the role of material objects as an essential element of religious devotion.

This article explores the role of a museum in remembering and promoting a missionary saint, the internationally recognized priest Father Damien (1840–1889). It focuses on the Damiaan Museum (or Damien Museum in the anglicized version) in Tremelo, Belgium. While ample scholarly attention has been directed to Father Damien himself, few scholars have written about the Damien Museum. This site is also worthy of attention, as its history reflects the missionary’s representation over time. Recently refurbished, the Damien Museum focuses on the life story—some might say myth—of a Belgian Roman Catholic missionary who lived in Hawai‘i amongst people with Hansen’s disease, formerly known as leprosy.Footnote1 Father Damien eventually contracted the disease himself and, after his death in 1889, was transformed into the martyred icon—and later saint—of Moloka‘i.Footnote2 Drawing on the archives of Damiaan Vandaag in Leuven; the Damiaan Museum, Tremelo, in Belgium; and the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, this paper sets out to explore how the Damien Museum supported the process of the canonization of Father Damien.Footnote3

The rules for the Roman Catholic canonization process have undergone multiple changes throughout its long history. This paper draws on the procedures for beatification and canonization found in the Code of Canon Law, the Codex Juris Canonici, of the Roman Catholic Church. These procedures were promulgated in 1917 and reformed in 1983 under the direction of Pope John Paul II, who famously approved a high number of canonizations (Beccari Citation1907, Peters Citation2001, Bennett Citation2011). Based on the reputation of sanctity after the death of the candidate, the Catholic canonization process for the period under discussion roughly consists of two phases, one at the diocesan level (in collaboration with the Vatican) and the second at the Vatican level. During the first phase, the candidate is nominated to the local bishop. If this initiation of a cause is accepted, the candidate is called a Servant of God. Evidence of the candidate’s saintly reputation or heroic virtue needs to be gathered and assessed before the candidate is considered to be venerable. This means that private devotion of the candidate is crucial, even though the Church does not allow public cults before a candidate is officially a saint. More divine signs are necessary to reach the next level of canonization, which can only be granted by papal decree. Canonization gives the saint his or her own feast day and authorizes their official worship within the Catholic Church (Woodward Citation1996). Scholars have only recently begun exploring the role of materiality in the Catholic canonization process (Hartel Citation2006, Osselaer Citation2018, see also Miller Citation2015). The relative lack of research on this topic until now is understandable, given that the Catholic church considers sainthood to be a result of divine, not human, agency (Woodward Citation1996, 119). However, as Arweck and Keenan (Citation2006, 2–3) write: “the idea of religion itself is largely unintelligible outside its incarnation in material expressions.” In what follows, I shed light on the questions of materiality and human agency at play in the canonization of Father Damien.

This article explores the role of the Damien Museum in the canonization process of Father Damien. The museum structure itself was not built as a missionary museum; rather, the missionary’s former family home was turned into a heritage site.Footnote4 This has been done for other famous religious and secular figures (Adinolfi and van de Port Citation2013). Indeed, scholarship on celebrity culture has highlighted the similarity between celebrity worship and religious devotion (Harrison Citation2006, Macklin Citation2005, Passariello Citation2005). However, Oliver Bennett (2011, 445) appropriately argues that “the relationship between the two is complementary, with organised religion drawing on celebrity culture as much as the other way round.” He writes that in many ways saints can be considered as the “prototypes of modern celebrities” (Bennett Citation2011, 439). This is true in the case of Father Damien. During his canonization process, the Belgian congregation drew on his celebrity status and appeal beyond the Catholic audience. John Allen called Father Damien the original “celebrity saint,” which he defines as a figure whose “moral heroism makes him a media sensation and fires the imagination of the world.” Father Damien drew widespread attention—from beyond his geographical region and outside the Catholic Church itself—because he “sacrificed himself” while challenging his superiors. He was controversial yet seemingly fully devoted to his cause (Allen in Volder Citation2010, vii).

Just as Father Damien blurs the line between a religious figure and a celebrity, the Damien Museum challenges the boundary between a sacred space and a secular museum. The word “museum” is derived from an ancient Greek term. In this era, museums were spaces dedicated to the muses and were considered secular temples. Today, museums are popularly understood to be educational institutions that focus on conserving and displaying tangible and intangible heritage.Footnote5 However, recent scholarship indicates that museums cannot merely be considered as neutral, secular spaces (cf. Buggeln Citation2012). Further, when religious objects are placed in museums, they do not necessarily lose their inspirational qualities (Paine Citation2013). As research on visitor interaction with religious objects in the 2011 exhibition Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe at the British Museum revealed, these encounters can inspire devotion in a museum setting as much as in an ecclesiastical environment (Berns Citation2016).

The Damien Museum further blurs the boundaries between monument and museum—both institutions that can be “viewed as potent, celebratory reminders of colonialism” (Aldrich Citation2010, 471). In Hawai‘i and the rest of the Pacific region, missionary encounters were complex. They sometimes led to strained relationships between European and American missionaries and the Pacific people whose spiritual and cultural landscapes the missionaries sought to reshape.Footnote6 In their attempts to follow both the church’s mission and to win the goodwill of the Pacific people, missionaries are “both connected to and detached from westernising ideologies” (Marten and Neumann Citation2013: 6). A final strand of scholarship that provides context for this paper therefore deals with the decolonization of museums. Euro-American museums were initially established as technologies of power closely related to the formation of the colonial state (Anderson Citation1991, Stocking Citation1985). In the 1980s, scholars and activists began to critically question Western museums’ colonial histories as well as the ongoing presence of their global ethnographic collections. Ethnographic museum collections were often assumed to be an uncomfortable legacy of dubious colonial enterprises that continued to misinterpret the cultures from which they were collected (cf. Ames Citation1986, Clifford Citation1988, Barringer and Flynn Citation1998). Decolonization, as stated by the Museum Association, is a “long-term process” that “requires a reappraisal of our institutions and their history and an effort to address colonial structures and approaches to all areas of museum work” (https://www.museumsassociation.org/campaigns/decolonising-museums/resources/). Behind the drive to decolonize the museum is an openness to restitution or to requests to repatriate colonial collections to Indigenous communities. As this article demonstrates, decolonizing the museum also involves a critical reading of colonial histories and the promotion of a multiplicity of voices (Giblin, Ramos and Grout Citation2019, Lonetree Citation2012). Hawaiian scholars from the 1990s onwards have argued that the voices of Native Hawaiians must be foregrounded in the story of Father Damien (Moblo Citation1997, Law Citation2012, Inglis Citation2013, Imada Citation2018). Ultimately, this article demonstrates that changes in the Damien Museum over time have reflected changing narratives about his significance. While early museum displays celebrated his work at the expense of his Hawaiian patients’ stories, later exhibits have challenged these earlier narratives. The Damien Museum has been redesigned to include more voices and to provide a more robust context for understanding Father Damien’s complex legacy.

Moloka‘i and ma‘i lepera

Since Europeans reached their territory in 1778, Kānaka Maoli, the Indigenous population of the Hawaiian Islands, have been exposed to infectious diseases against which they had no immunity. This resulted in a significant decline in population. Many of these introduced diseases—such as measles, smallpox and venereal disease—carried the potential to disfigure a sick person’s body. However, ma‘i lepera, or leprosy, became perhaps the most feared illness. Not only did it lead to disability, but sufferers were also removed from their families. In 1865, the Kingdom of Hawai‘i passed ‘An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy’, which required people who had been diagnosed with the disease to be placed in quarantine. A leprosy settlement was established in 1866 and it operated until 1969, when the State of Hawai‘i repealed the law. People with ma‘i lepera were sent to Kalawao and Kalaupapa on the Kalaupapa Peninsula on the northern shore of the Hawaiian Island of Moloka‘i. In the first few decades of the settlement, medical care was not always available to them (Inglis Citation2017, 287–289). The reason for creating an isolated settlement was that the government believed leprosy to be highly contagious, even though at that time doctors did not know how it was transmitted (Le Hoang Ngoc Citation2018, 360). The Kalaupapa peninsula was chosen because it was thought to be self-sufficient; the high pali (mountain) and rough ocean waters that surrounded the peninsula served as a natural boundary. There seemed to be sufficient farmland, some of which was already government-owned, with the remainder being bought from the locals (who were not all willing to leave) () (Inglis Citation2017, 295). By the late 1890s, leprosy had come to be referred to as ma‘i ho‘oka‘awale ‘ohana (the disease that separates family). Moloka‘i was interpreted as “a place where people were sent to die” (Edmond Citation1997, 78; Inglis Citation2017; Strange Citation2004, 90).

Recent scholarship has shown how the notion of segregation and its subsequent victimization of Hawaiian patients needed revision. While not denying the disastrous effects of this segregation, more recent narratives have returned agency to the patients by pointing out how they formed communities in the settlement. Hawaiians resisted the segregation policy and often hid those who contracted the disease. Alternatively, relatives of Hawaiians faced with exile chose to live with them as kōkua (helpers) (Inglis Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2017; Imada Citation2018; Law Citation2012). Still, the segregation policy caused trauma for several generations. Between 1866 and 1969 approximately eight thousand people − 95% of whom were Kānaka Maoli—were quarantined at the settlement (Inglis Citation2017, 289). As Rod Edmond points out, “medicine and disease control has often been used as an instrument of colonial authority” (Citation1997, 78). Indeed, the segregation policy was developed while foreign business interests were steadily taking over the Hawaiian government (Herman Citation2001, 319).

Fears of mass contagion have since been scientifically proven to be unfounded, and Dr. Hansen’s 1873 discovery of Mycobacterium leprae has shown that a bacillus infection is responsible for the disease. The slow-growing bacteria are spread through respiratory droplets, and genomic studies have shown that 95% of humans are naturally immune to the bacillus infections. To contract Hansen’s disease requires long-term exposure to untreated patients. The current standard of care using multidrug therapy has made isolation therapy unnecessary (Cheung 2018, 56, 62; WHO Citation2018). While this is a significant breakthrough, this article shows that the human impact of the former medical misunderstanding of the disease is still felt today.

Mythification Versus Stigmatization in the Settlement

Two years before the first patients were sent to Moloka‘i, Father Damien (Pater Damiaan) arrived in Hawai‘i on 19 March 1864. He was born Joseph de Veuster on 3 January 1840 in Ninde, a hamlet in Tremelo, Belgium. The seventh child of well-to-do farmers, his father had hoped for his son to follow in his footsteps. However, Joseph longed for a religious life, following the path that some of his siblings had chosen. Therefore, after some years of working on his parents’ farm, he entered the Catholic Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (SS.CC) as a postulant in January 1859. Also known as the Picpus Congregation, this community was located in Leuven. In 1863, Joseph’s brother, Father (August) Pamphile, contracted typhus and was prevented from travelling to the Hawaiian Islands to become a missionary. Joseph, by then Father Damien, begged to take his place, even though he had not finished his religious education. After his arrival in Honolulu, he was ordained in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Peace on 21 May 1864. He worked for nine years on the Big Island of Hawai‘i in the parishes of Puna, Kohala, and Hāmākua.Footnote7

Meanwhile, more and more people diagnosed with leprosy were sent to Moloka‘i. The forced exile of patients and the minimal medical aid provided by the government meant that Christian clerics initially became the main providers of care. In 1873, the situation in Moloka‘i became an issue for the Picpus Congregation, when 200 local Catholics presented a petition asking for a resident priest. Until then, a priest from Maui or O‘ahu would occasionally travel there; Brother Victorian Betrand even built a wooden chapel in Honolulu and transported it to Moloka‘i in 1872 during these visits. When the petition was discussed during a gathering of Congregation representatives in Wailuku in 1873, it was suggested that a group of priests should take turns in residing for three months each at the settlement. Father Damien, then 33, went first. He arrived in Moloka‘i on 10 May on board the steamer Kīlauea, along with 36 men and women who had been diagnosed with ma‘i lepera. Within two days, Father Damien had decided that he wanted to stay permanently (Law Citation2012, 88–89). Father Damien’s choice was soon seen as a sacrifice that became part of imperial, Christian, medical and popular consciousness (Luker and Buckingham Citation2017, 271). The standard narrative of Damien’s work at Moloka‘i has been one of creating order out of anarchy and replacing neglect with care. It is said that Father Damien created a united community that built a church, schools, a water system and boosted people’s morale. However, Hawaiian language newspapers show the resilience of patients themselves by reporting how poi was made of wheat flour rather than breadfruit (Kanohokula Citation1879). After sixteen years at the settlement, Father Damien died from leprosy in 1889. His death was publicized internationally, not only because of his so-called selflessness, but mainly because his death drew attention to a persistent disease which had by then been associated with colonized people—forgetting about the recent prevalence of the disease in Europe (Edmond Citation2006, 90–102, 151). As Edmond (Citation2006, 98) wrote “Damien’s death had drawn public attention to leprosy as a modern imperial problem.”

As much as Father Damien was revered and admired, Kānaka Maoli patients were stigmatized. Repulsion and horror have been the most common Christian responses to people with leprosy since biblical times. In the Old Testament the disease was considered to be an emblem of sin. In the New Testament sufferers became figures of pity who were offered the hope of salvation. In the Medieval European view the disease was still closely associated with sin. During the 1870s and 80 s ma‘i lepera in Hawai‘i was increasingly moralized as a just punishment for a corrupt Indigenous society (Edmond Citation1997, 78; Edmond Citation2006, 1–2; Vaughan Citation1991, 79–80)—except by Kānaka Maoli themselves whose lack of disgust towards the disease was worrying towards non-Hawaiians (Amundson and Ruddle-Miyamoto Citation2010). Christian revulsion of the disease increased the impact and heroism of missionary work amongst the community (Edmond Citation2006, 151). The contrast between Father Damien as the missionary martyr versus the Indigenous victims thus loomed large.

Father Damien himself provoked contradictory responses throughout his life and after his death. In September 1873 the Board of Health asked him not to disobey the quarantine rule and to stop leaving the settlement. He was considered stubborn amongst his superiors, not always following their suggestions. Yet, after her visit to the settlement in September 1881, Hawaiian Princess Lili‘uokalani (1838–1913, Hawaiian Queen from 1891 until the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893) arranged to make Father Damien Order of the Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalakaua for his efforts on behalf of her people (Law Citation2012, 92, 112, 125). His close friend and colleague Ambrose K. Hutchison described him as a “vigorous, forceful and impellent man with a big kindly heart” (Hutchison in Law Citation2012, 112). Finally, there were the allegations of sexual impropriety made by Dr. Hyde to which Robert Louis Stevenson wrote a famous reply emphasizing Father Damien’s altruism (Stevenson Citation1890). This controversy showed the position he represented. In Edmond’s words: “He bridged the world of European and Hawaiian, clean and unclean, saint and sinner, imperialist and native” (Edmond Citation1997, 79). Ultimately the controversy made him famous beyond the boundaries of Moloka‘i.

Material objects helped to sustain his fame. For example, Father Damien was well photographed: eleven historic photographs, a high number for a nineteenth-century missionary, were taken during crucial moments in his life and circulated (Boon and Jaspers Citation2018). Before leaving for Hawai‘i, he sat for portraits in Paris in 1863, which he himself distributed among family members and colleagues in Leuven (Letter Joseph De Veuster to parents, 30 October 1863).Footnote8 The newly born mass media of the late nineteenth century ensured a wide distribution of these images in the following decades, including in the form of drawings reproducing the original photographs. In 1878 Father Damien posed with 12 girls, who formed the girls’ choir of Kalawao, Moloka‘i, in front of Henry L. Chase’s lens. Father Damien is shown in the center amidst the girls. The contrast between his black clothes and the girls’ white dresses is emphasized even more by the contrast between his healthy glow and the girls’ diseased and disfigured skin. These images reiterate his role as savior or father figure for these children. The image was reproduced with captions such as “Father Damien amidst his ill patients.”Footnote9 The patients were anonymous, reduced to their disease.

From the 1870s and more systematically from the 1890s to the 1950s, the Hawai‘i Board of Health took clinical photographs of ma‘i lepera patients, resulting in what “may constitute the most extensive visual and biopolitical cataloging of Indigenous and Asian bodies within America’s Pacific empire” (Imada Citation2017, 5). In contrast to Father Damien’s photographs, these were used to record the disease, not the people. The diseased subjects were not glorified like Father Damien; the focus was on their deformed bodies. The stigmatization of Kānaka Maoli patients carried on in material terms. As Imada (Citation2017, 2, 6) points out “these images firmly attached this dreaded disease to people and bodies from the Pacific,” yet the people represented “were more than biomedical subjects; indeed, they persist as kupunā (elders) whose ‘iwi (bones) and memory are treasured by descendants.”

Father Damien’s photographs were used to celebrate him and were circulated as if they were religious images, the focus of unofficial devotion. David Morgan (Citation1998, 1) considers religious images to be part of the “visual formation and practice of religious belief.” Even the images of Father Damien on his death bed, showing the signs of his disease, were reportedly bought by thousands of Londoners. In Birmingham, when this photograph was displayed in a shop window, police had to intervene to control the crowds (Daws Citation1973, 10). In addition to photographs, the plethora of monuments erected for Father Damien express the significance of material representations in sustaining his prominence after his death. In what follows, this article will consider the role of the Belgian Damien Museum in sustaining his famed reputation which supported his journey to sainthood.

Damien Museum: Celebrating a Religious Hero in Material Form

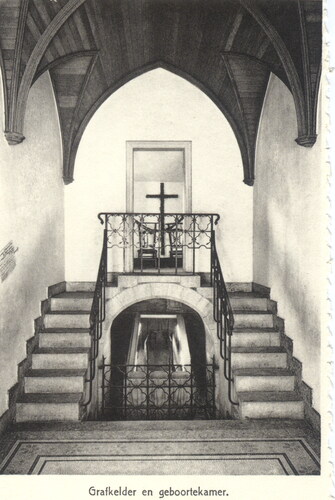

In 1895 the Picpus Congregation acquired the house where Father Damien was born in Tremelo, Belgium. That the Congregation purchased the house only six years after his death suggests that they realized that Father Damien’s story could enhance their appeal for his sainthood. The house was originally built before 1800 as the first brick house in the area. In 1895, two brothers of the Congregation moved into the living quarters and changed the house into its current subdivision. The kitchen was newly tiled and the open fire taken out when the Brothers turned it into a reception room in 1897. Objects associated with Father Damien that had been returned from Hawai‘i, including liturgical artefacts, carpenter’s tools and books, were carefully arranged in oak cupboards in the largest room of the house. In its first iteration as a museum, the house served more as a memorial where people could see the material environment that had shaped him. In 1904 the barn and stable were demolished and replaced by a convent, and in 1907 the novitiate moved in (). The museum itself (consisting of one room) remained unchanged and was only open to the public by appointment (Volk Citation1952; Patteet Citation1963, 731).

FIG 2 Father Damien’s family house (centre) integrated into the convent. This photo was taken before the fire of 1943 (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

In order to turn Father Damien’s living quarters into a display area, congregants focused on material things to tell his life story. In the first few decades of the museum’s existence, the things he used in Belgium and Hawai‘i were exhibited. However, in 1935 King Leopold III of Belgium asked the US President for permission for Father Damien’s body to be returned to Belgium, which instigated further development of the museum. By 1936 Father Damien’s body became the main object.

When news of the potential return of Father Damien’s body initially reached Hawai‘i, however, there was much opposition expressed in local newspapers. In many articles Father Damien’s connection to Hawai‘i was emphasized: “Although not strictly a ‘kamaaina’ [kama‘āina] in the true ‘son-of-the-soil’ sense of the word, Father Damien was as much a part of Hawaii as the ‘palis’ [mountains] that surround Kalaupapa and Kalawao—and their shimmering waterfalls. He was as much a part of Hawaii as the surf that beats incessantly at the rocky shores of Kalaupapa” (Hawaii Sentinel Citation1935). In The Honolulu Advertiser (1935d), it was stated that “Father Damien belonged, and belongs, to Hawaii. His expressed wishes indicated that. His life of sacrifice proved it.” Later that month a reader wrote in the same newspaper: “Never have a man and his work been more indelibly stamped upon a specific place than Father Damien and his labors upon that desolate shelf of land at Kalaupapa and Kalawao” (Honolulu Advertiser Citation1935b). The Belgian Consul, Victor H. Lappe, replied by emphasizing the link to Belgium: “Let then Hawaii, in a gracious outburst of generosity, which is so characteristic in its people, return to Belgium what is rightfully its own by birthright” (Honolulu Advertiser Citation1935c). Lappe refers to the hospitality and generosity, the aloha, of Hawaiian people. As Nohelani Teves (Citation2018, 7) writes, “Both a blessing and an obligation, aloha also constrains, often prescribing how Kānaka Maoli are supposed to act.”

The request to transfer Father Damien’s body to Belgium should be considered as a first step in his beatification process.Footnote10 Concluding that there was not enough initiative on the Hawaiian side to begin the campaign for Father Damien’s sainthood, the Picpus Congregation wanted to take the process into its own hands. This request was eventually granted because the isolated location of Father Damien’s tomb prevented supporters from visiting it.Footnote11 On 27 January 1936 his body was exhumed from its burial site in Moloka‘i. This departure was marked in Hawai‘i by church ceremonies in Honolulu. Additionally, the US Army performed a hero’s departure with bombers flying overhead. Father Damien’s body then travelled to Belgium aboard the ship Mercator, which anchored in Belgium on 3 May 1936. His arrival was marked by a similar celebration. Father Damien’s body arrived in a hearse drawn by white horses as cannons boomed and church bells pealed. Huge crowds welcomed him back (). Father Damien’s body had travelled in a newly made casket of koa wood grown on Hawai‘i Island. It had been made by craftsmen at the Honolulu Planing Mill, which had built koa caskets for Hawaiian royalty for generations (Honolulu Advertiser Citation1936a, 4; Honolulu Advertiser Citation1935a).

FIG 3 Father Damien’s body is carried into St Anthony’s Chapel in Leuven, Belgium, on 2 May 1936 (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

On 31 January 1938, the first phase of the beatification process began. This step requires the collection of evidence about the candidate to determine whether a petition for a formal cause is feasible. It is important to sustain the candidate’s saintly reputation (fama sanctitatis) in the years thereafter (Woodward Citation1996, 344–389). While no public cults in support of candidates are permitted by the Church, private devotion is vital to this stage of the process. As Woodward (1996, 17) writes: “The making of saints, therefore, is an inherently ecclesial process. It is done by others for others… the ‘others’ are not bishops or professional Vatican investigators, but anyone at all who… contributes to a candidate’s reputation for holiness.”

This devotion by the people was facilitated in the Tremelo Museum, where congregants celebrated Father Damien’s life and service through objects. Many of these objects had been collected by Father Vanhoutte, Provincial of the Belgian Picpus Congregation. He had collected a variety of objects at the end of 1936, when he travelled to Hawai‘i to thank the authorities for the return of Father Damien’s body. Father Vanhoutte envisioned that these objects would be placed in a museum to be established in Leuven near the crypt that houses Father Damien’s tomb in St Anthony’s Chapel. His grave had become a place of worship and Father Vanhoutte believed a museum in Leuven could cater for the pilgrims visiting his shrine (Courant Citation1938). However, the vision of a museum in Leuven was never realized. Instead, the Tremelo family house was developed further as a museum site dedicated to Father Damien.

Thus, the objects that Father Vanhoutte brought from Hawai‘i found their place in the Tremelo Museum. He had brought the altar from the St Philomena Church in Kalaupapa, which had been hand-made by Father Damien. From the church’s sacristy he had taken an eighteenth-century altar missal, a monstrance, a processional banner and probably a music manuscript bound in pandanus (Tijd Citation1937; Boon et al.Citation2015). In Belgian newspapers these objects were unapologetically called “relics” (Nieuws van den Dag Citation1937; Libre Belgique Citation1937). Relics are objects used in devotional interactions and provide followers with the material and spiritual means to reconnect with the associated saint. The physical remains and possessions of saints have been revered since early Christianity. As Geary (Citation1994, 194) states, relics “belong to that category, unusual in Western society, of objects that are both persons and things.”Footnote12 Father Damien was not a saint (yet), but there was clearly a process of celebrating him through objects in the Tremelo Museum. Father Damien was represented through liturgical artefacts, books and carpenter’s tools. The inclusion of tools is noteworthy for two reasons. First, they relate to the profession of Jesus’ father, who was a carpenter. Second, the tools—Father Damien used them to build houses and coffins—highlight his role as community builder. The museum provided objects as an incentive for belief in Father Damien’s heroic deeds. His things, treated as relics, served an important role in rendering Father Damien’s life iconic. More than his grave in Leuven, the museum provided the visitor with materials that showed a man who was religious and selfless—and who cared for the spiritual as well as the material needs of his community.

In addition to displaying his objects, the museum turned the room where he was born into a chapel. A journalist visiting in 1947 wrote when entering this room: “A blessed silence reigned and one involuntarily senses the sacredness of the place.” The fact that an appointment had to be made to visit the museum enhanced its special status: “When we enter the sanctuary where the Apostle Damien grew up, we felt a step closer to Him, who, so far from home, in all simplicity died amongst his friends” (Vrije Volksblad Citation1947, author’s translation). Visiting the museum became a sacralizing experience.Footnote13 While officially called a museum, which is usually considered a secular institution, the Tremelo Museum did not become the secular counterpart of the sacred shrine in Leuven. Instead, it gained a spiritual significance in itself. As such, the museum began to play a role in Father Damien’s beatification process.

Separating Father Damien and Kānaka Maoli in Material Terms

In September 1943, a fire destroyed the convent adjacent to the museum. Between 1946 and 1949, the convent was rebuilt. While the family house remained undamaged in the fire, the museum was refurbished around 1950. Two rooms of the former convent that withstood the fire became part of the museum, in addition to the original family house, and thus became “documentation rooms.” A square tower, representing a mission church, was also added. On 18 May 1952 the refurbished, white-chalked museum was recognized as a state monument. At this time, new operating hours enabled wider visitation, as the museum was open to the public most days of the week () (Volk Citation1952; Patteet Citation1963, 730). The first documentation room opened as well, which focused on Father Damien’s life in Hawai‘i (). It featured handmade chandeliers and the altar that Father Damien had built for the Philomena Church in Moloka‘i, near a display case with his tools. On the walls hung a collection of drawings by Edward Clifford, who had spent three weeks on Moloka‘i at the end of 1888.These drawings had been donated to the museum by Clifford’s niece in 1933. Other display cases showed his books, his Bible, letters, notebooks, his pipes and his chasubles (Goed Nieuws Citation1954).

FIG 6 Documentation room focusing on Father Damien’s life at the Damien Museum around 1960 with the altar that Father Damien built for the St Philomena Church (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

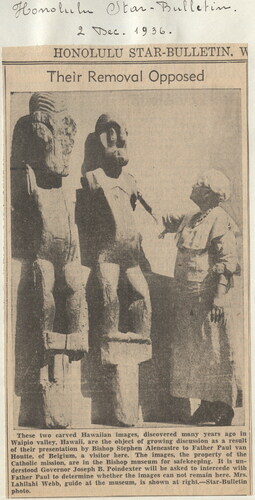

When Father Vanhoutte returned Father Damien’s possessions from Hawai‘i in 1936, he had initially also wanted to return collections assembled in the Pacific region by other missionaries from the Congregation. However, the transfer of two Hawaiian figures that had been found in Waipi‘o Valley in 1911 was hindered by the Hawaiian audience (Honolulu Advertiser Citation1936b). The images had probably been left behind or hidden when Hawai‘i‘s old religion was overthrown in 1819. They were ki‘i heiau (temple images) which acted as receptacles to contact the akua (gods) and probably once stood upon Pāka‘alana heiau. In 1919 the Catholic Mission had presented them on loan to the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum for safekeeping. There, they were identified as two akua (gods): Kū, the god of chiefly governance, warfare, protection and procreation; and his wife Hina (Schorch et al. Citation2020, 42; ). “Keep them in Hawaii,” headlines The Honolulu Advertiser (Citation1936c) read when reporting on the potential removal of the Hawaiian figures from the Bishop Museum. As the author of this story wrote, “It is hoped the owners will reconsider and that these mementoes of an earlier regime will be left where sentiment attaches to them, and where their presence has a definite meaning” (Honolulu Advertiser Citation1936d).

FIG 7 Newspaper clipping of the Honolulu Star Bulletin, December 2, 1936, showing Mrs. Lahilahi Webb, guide at the BP Bishop Museum with the ki‘i heiau (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven with permission of Honolulu Star Bulletin).

The discussion of where the Hawaiian figures belonged became one of ownership and repatriation. The debate was based on birth-right, or place of origin, and questions of who has the duty of care of objects. These questions had also been raised regarding the transfer of Father Damien’s body. Both of these discussions resembled museum talk. Repatriation as an event and debate focuses on the issue as to whom “things” (human remains and objects) belong and who should look after them (Kakaliouras Citation2012, S211). The juxtaposition of Father Damien’s body and the Hawaiian figures underlines the sense of potency with which objects are imbued both in the Pacific and in Roman Catholicism. The figures were to stay in Hawai‘i, particularly since Father Damien’s body had been returned to his birth land: “It is felt this would be a gracious goodwill gesture in return for the kokua [help] Hawaii gave in the transference of Father Damien’s remains” (Honolulu Star Bulletin Citation1936a). The Honolulu Star Bulletin (Citation1936b) listed several reasons for the historic wooden figures to remain in Hawai‘i, including: “The idols are authentically Hawaiian and belong, by right of origin, at least as much to Hawaii as to any foreign land.” The Catholic Congregation decided to gift the figures to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Careful to ignore the figures’ local potency, Father Vanhoutte stated that this gift was “in the sole interest of scientific and historical research” (Letter by Father Vanhoutte to Peter H. Buck, December 12, 1936).Footnote14

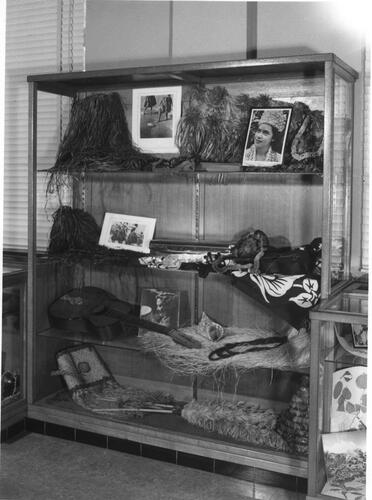

In return for donating the Hawaiian figures, the Bishop Museum gave the Congregation a collection of 50 artefacts and botanical specimens “representative of ancient Hawaiian culture” (Letter Vanhoutte to Buck, December 12, 1936).Footnote15 This collection would form the basis of the Hawaiian display in the Tremelo Museum, situated in the second documentation room. It officially opened on 17 June 1953 (). The room literally provided documentation about Hawai‘i. Displayed on the wall was a cloth with the phrase Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ‘Āina i ka Pono (The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). This phrase was first uttered by Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) upon the re-establishment of the Hawaiian Kingdom in July of 1843 following the temporary cession of his sovereignty to Great Britain. Later the phrase was adapted as the motto for the State of Hawai‘i.Footnote16 In the display, facts and figures about Hawai‘i were provided in the form of maps and overviews of export produce, flora and fauna. The bulk of the artefacts from the Bishop Museum—such as basketry, bowls, musical instruments, kahili (scepters) and ihe (spears)—were included in this display. As a local newspaper described it: “In a clear manner hundreds of objects that need to give an image of the life of the inhabitants of Molokai were displayed… one can admire the colorful clothes of the natives, their arts, customs and habits, their ornaments and adornments, the corals and shellfish that live in the seas, the beautiful basketry, their weapons, musical instruments, utilitarian objects, colorful birds that live on the island, etc.” (Standaard Citation1953, author’s translation). A magazine geared towards women linked it to reigning stereotypical perspectives of the place: “One case with musical instruments within the center a large photograph of female hula dancers! They wear the hibiscus flower in their hair and wear lei around their necks” (Goed Nieuws Citation1954, author’s translation).

FIG 8 Documentation room focusing on Hawai‘i at the Damien Museum around 1960 (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

FIG 9 Display case with fibre skirts, musical instruments and photographs of dance performances in the Documentation room focusing on Hawai‘i at the Damien Museum around 1960 (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

In both documentation rooms, visitors could learn about Father Damien and Kānaka Maoli through objects. These objects were the result of interactions and relations between Father Damien and Kānaka Maoli. A crucial feature of material remnants of the missionary encounter is their potential to become a focus for reflections on shared histories by people from different parts of the world, with the associated complexities that this involves. However, in the museum the Hawaiian people and Father Damien were clearly separated, shown in different rooms. In the Hawai‘i room the emphasis was on the artistry and economy of Hawaiian people. The way information was logically and rationally conveyed contrasted with the way that piety was emphasized in the Father Damien room. There, the collections were an active instrument in the perpetuation of Father Damien’s beatification story.

On the Journey to Sainthood: The Role of Relics

In March 1955 Father Damien’s cause of beatification was deemed to merit a formal process and was introduced to the Congregation of Rites in Rome. The first step, the Apostolic Process, examined the heroic degree of the virtues of the missionary priest and the validity of reported miracles (Letter Father Furtado to Father Walter, April 29, Citation1959).Footnote17 While this took place, Father Damien’s body was exhumed in 1956 to be turned into relics. This process, which takes place on the journey to sainthood, allows for remains to be accessible to the faithful. Divided into soldered zinc containers, his personhood could then be distributed and his holiness spread. The circulation of relics has a long history, so much so that Geary (Citation1994, 194) discusses medieval relics as “sacred commodities.” The koa coffin in which Father Damien’s body was transported to Belgium became a third-degree contact relic as chips from the coffin were gradually distributed. The fact that things that have been in contact with the saintly candidate become relics reminds us how much sainthood is based on the material and corporeal. The original coffin in which Father Damien had been buried in Moloka‘i also became a contact relic. It found a place in the chapel of the Tremelo Museum, making it even more into a pilgrimage site (). In 1963 T.N. Jagadisan, Organizing Secretary Indian Leprosy Association, wrote in the museum’s visitors’ book:

FIG 10 Chapel adjacent to the room where Father Damien was born, where his original coffin was displayed from 1956 onwards (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

How thrilled I am to make this holiest of holy pilgrimages on 2nd October 1963, Mahatma Gandhi’s birth anniversary! The Mahatma considered that there have been few lives in history or legend lived on the completely spiritual and heroe [sic., hero] level of Father Damien; Since I am one who has had leprosy and brought through the Lord’s Grace into the service of Leprosy patients, I feel hushed with reverence at this holy shrine. (Museum Pater Damiaan Citationn.d.)

The reference to the museum as a shrine is interesting. A shrine generally holds relics of various kinds and serves as a target for pilgrimage and devotion. The Roman Catholic Church aims to have strict control over relics’ authenticity (Geary Citation1994, 204). However, in addition to these official relics, other objects in the Damien Museum that had been used by Father Damien had already been characterized as unofficial “relics” by the media (see above). Relics, corporeal and non-corporeal, have a wider use beyond Catholicism, and in religious practice globally. The term is also used in association with people who have acquired fame or a celebrity status because their clothing and possessions receive a relic status in the eyes of their fans and are therefore highly collectible (Walsham Citation2010, 11, Hooper Citation2014).

In 1968, Tremelo Museum staff paid particular attention to the house’s family room and the recreation of the interior as it would have been during Father Damien’s youth. An appeal was made to the people of Ninde to donate objects that would have been used in old farmhouses (Nieuwsblad Citation1968). The museum’s family room aimed to show the environment that led to Father Damien’s remarkable deeds. It was conveyed as a simple yet pious environment, in which a mother read from a book of saints to her children every night.Footnote18 The appeal for re-authenticating his life was part of the mission to keep Father Damien’s memory alive. As Picpus Father Jammaers wrote, “We cannot let the memory of Damien fade. His ‘birth house’ should be one of the inspiring places in Flanders. It does not matter what we do with the plane, chandelier or chasuble of Damien. What matters is what we do with Damien himself, what inspired him, and what people after us will do with him” (Smets and Jammaers Citationn.d., 11, author’s translation). Yet, the objects played an important role in sustaining the aura of fame surrounding Father Damien. Indeed, relics are “material manifestations of the act of remembrance” (Walsham 2010, 13); they evoke “an absent whole” (Wharton Citation2006, 9–10). As a result of the Museum’s appeal, the people of Tremelo brought in a small number of objects that entered the collection and received an association with Father Damien that did not necessarily exist. What matters is not necessarily the relics’ authenticity, but what they teach us about belief and devotion. In this case, objects unrelated to Father Damien himself were still deemed valuable, as they helped to represent his pious life for visitors to the museum.

On 7 July 1977 Father Damien was declared Venerable by Pope Paul VI. Now a “Servant of God,” divine signs were required for him to be beatified. These were examined in accordance with miracle standards. It needed to be established that God performed a miracle and that it occurred through the intercession of the servant of God. If additional divine signs were reported after the beatification, canonization could follow (Woodward Citation1996, 79–86). In the following years (around 1980) the Tremelo Museum was adapted to emphasize elements of Father Damien’s life that supported his role as a mediator of God’s miracles. In the Hawai‘i room, many of the Hawaiian objects were taken from the display to make space for a slide show that conveyed information about melaatsheid (Dutch for leprosy). The accompanying text (in Dutch, French and German) described Old and New Testament perspectives on the disease and how people thought about it in the Middle Ages. It also included more recent efforts to cure the disease and what work remained on that front (Knichel [Citation1980]). The Hawaiian collections in the wall cabinets remained, but they served more as idyllic décor. The focus of the display now centered on leprosy, which was presented as a horrible disease that left people disfigured, disempowered and dependent. The focus of this display became the disease itself and Father Damien’s related work.

In 1986 Father Damien’s relics were distributed further when the Belgian Damien Museum made donations to the Father Damien Museum in Honolulu (19 August). These included tools, a kapa (barkcloth) beater and a gourd together with photocopies of photos (Note by Provinciaal [name illegible]).Footnote19 Then, in June 1991, Pope John Paul II approved Father Damien for beatification after the Vatican Medical Board ruled that the miraculous recovery of Sister Semplicie Hué could be attributed to Venerable Father Damien’s intercession. By 1895 this healing had been put forward, but had not been recognized as miraculous. With Father Damien’s new status as “Blessed,” it was decided that another relic (his right hand) would be returned to Hawai‘i and reinterred at Kalawao. It is a usual part of the beatification process to send a relic to the Vatican, but the decision was made to send it to Hawai‘i instead due to Father Damien’s close connection to the land. The journeys taken by Father Damien’s body in addition to other objects associated with him mark a process of remembering through which his memory is dispersed.Footnote20

Since 1983 two miracles are required for the canonization of non-martyrs. In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI recognized as a second miracle: the spontaneous disappearance of incurable cancerous tumors from Audrey Toguchi in 1999 after regular praying visits to Father Damien’s tomb in Kalawao (Damiaan Vandaag Citation2012). On 11 October 2009 Father Damien was canonized; a papal declaration confirmed that he is with God and can be subject to devotion as a result. His right heel bone was sent as relic to Honolulu.

In the decades that followed Father Damien’s death, many of those who sought to remember him displayed or distributed his things and body, which became a carefully crafted object rather than a mere biological entity. The objects associated with Father Damien were a means of celebrating him in different spaces; their circulation helped to spread his story.

Shared History: Refurbished Damien Museum and New Mission

Father Damien’s 2007 canonization—as well as a 2005 vote bestowing on him the status of the Greatest Belgian of All Time—spurred an interest in refurbishing the Damien Museum. By this time, he was recognized not just a saint but a celebrity as well. And yet, recent discussions about the violence of colonialism raise questions about the memorialization of a figure such as Father Damien. In a time when public statues of colonial figures are being contextualized or removed—a discussion which only recently started in Belgium where a high number of colonial monuments were builtFootnote21—one might ask whether it is appropriate to have a museum devoted to a Belgian saint who worked as a Catholic missionary in the Pacific. This is a question that the museum staff obviously asked themselves. Their answer partly lies in the decision to nuance the focus on one individual and to include a multiplicity of voices.

By the mid-2000s, Museum staff members were aware that the museum presented a contrast between Father Damien and his patients. Displays in the Tremelo Museum portrayed him as a savior, while Hawaiian patients’ stories were neglected. This dated and colonial representation had been addressed in scholarship but not yet in the museum. In 1969, the Hawaiian government had ended its mandatory isolation policy in Moloka‘i. When Kalaupapa became a National Historical Park in 1980, some former residents became tour guides. Since then, Hansen’s disease patients have fought to reclaim their place in society and fight the disease’s stigma. Museum staff recognized the need to tell these stories.

Since the 1990s, Hawaiian scholars have contested stories of Moloka‘i that valorize Father Damien at the expense of the patients he lived with in Kalawao and Kalaupapa. Pennie Moblo (1997, 715) advocated against what she identified as the mythical rendering of a great white savior from the west and stated that “the focus on Damien eclipses the active role played by Hawaiians, and preserves a colonially biased history.” Since Moblo’s strong appeal to remove Father Damien from his pedestal, scholars have focused on the role of the community as a whole. Scholars have begun to highlight the experiences of the patients and their families, and the impact of forced quarantines on the Hawaiian community. Memoirs such as Olivia: My Life in Exile in Kalaupapa (Breitha Citation1991) and No Footprints in the Sand (Nahaielua Citation2006), as well as interviews with patients published in scholarly works (Law Citation2012; Inglis Citation2013; Imada Citation2018), offer a glimpse of how people suffered, but also show the support and sense of community that existed. Patients’ abilities, rather than their disabilities, become the focus, which nuances the story of their “savior.” This research indicates how Father Damien has a place in Moloka‘i’s history amidst the many patients, helpers (kōkua) and supporters, whose voices are finally recognized (Law Citation2012; Inglis Citation2013; Imada Citation2018; Strange Citation2004, 88–89).

This shared history is shown in the refurbished Tremelo Museum, which opened on 25 May 2017. This iteration of the museum’s design no longer separates the representation of Father Damien’s life from Hawaiian culture nor juxtaposes the objects that represent them. A timeline in the entrance area situates Father Damien in European and Hawaiian history and beyond. The display compares him to other well-known human rights activists such as Mahatma Gandhi (who expressed admiration for Father Damien) and Martin Luther King (). The family room is still unfinished, and the chapel invites quiet contemplation and, indeed, devotion.Footnote22 In the first documentation room the focus is on Father Damien’s life in Hawai‘i. Hawaiian kapa (barkcloth) and gourds, poi beaters, bowls and other utensils are shown next to a desk where his letters can be read. A ukulele is displayed next to his tools (). The first room offers a range of voices including those that “articulate patient subjectivities” (Luker and Buckingham Citation2017, 84). The patients are no longer anonymous. Recent scholarship on the identification and biographies of Kalaupapa patients by Anwei Skinses Law (Citation2012) is elaborately shown through an interactive screen. Law helps run an international organization to promote the rights of people with Hansen’s disease. One aim of the Law’s work is to broaden Kalaupapans’ words and images beyond the history of Hawai‘i and colonialism, and instead include their stories in larger conversations about genocide and trauma (Strange Citation2004, 104). The refurbishment of the museum can be considered a decolonizing strategy. Decolonizing the museum involves critically engaging with colonial histories and treating them as encounters that involved traumatic cultural erasure as well as strategic Indigenous intervention (Giblin, Ramos and Grout Citation2019, Lonetree Citation2012). These are elements that the Damien Museum has now emphasised.

FIG 11 Refurbished Damien Museum, which opened on 25 May 2017 (Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

FIG 12 Timeline in the 2017 refurbished Damien Museum (Copyright Bailleul; Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

FIG 13 First Documentation room in the 2017 refurbished Damien Museum (Copyright Bailleul; Courtesy of Damien Collection, Leuven).

In the museum’s second documentation room the focus is on the work of Damien Action, an NGO which is active across 13 countries that aims to help people suffering from Hansen’s disease, tuberculosis, and leishmaniasis. Father Damien may be the foremost reason why people visit, yet his story is not the only one they hear once they arrive. Father Damien’s story in the newly refurbished museum now enables multiple conversations, many of which direct visitors beyond a European-centric context. The focus has subtly shifted from Father Damien as hero to Father Damien as Samaritan, who could not have done his work without others: “It is a place of experience and interaction, of inspiration and reflection… Damien’s message of hope, respect and solidarity is a powerful appeal for societal attention and engagement for anyone who feels excluded or treated unfairly” (Boon Citation2018, author’s translation). The museum promotes itself as an experience center, using Father Damien’s work as a source of inspiration to do good. The website invites potential visitors to “Discover how a Father Damien is lurking inside all of us” (http://damiaanmuseum.be/en/).

Epilogue

The history of the Damien Museum is an interesting interplay between seemingly separate places and notions—such as celebrity and sainthood, object and subject, spirituality and materiality, Hawai‘i and Belgium, museum and memorial, and profaneness and sacredness—which in reality overlap. The story of Father Damien and his museum in Belgium invites us to upset these binaries. Furthermore, this analysis of the Damien Museum has showed the effective role of the museum and of materiality in the campaign to sainthood. Museums are collections of fragments through which stories are told. The process of selecting fragments and deciding which stories to tell is difficult and necessarily selective. Each of the Museum’s refurbishments has been connected to Father Damien’s representation at the time. His evolution from religious figure to international hero to celebrity saint and world-renowned humanitarian is closely linked to the exhibits that have illustrated his life through objects. The Damien Museum has transformed from providing an intimate view of Father Damien’s life by appointment only to a modern museum that tells a universal story. While it has changed over time, what has remained constant is that, despite its educational purview, the Father Damien Museum has also functioned as a memorial, and a sacralizing space for people who believe.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Ruben Boons, Patrik Jaspers and Karolien Borghlevens at Damiaan Vandaag, Leuven; staff at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum and Alice Christophe and Sarah Kuaiwa for their time and work.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karen Jacobs

Karen Jacobs is Associate Professor at the Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, University of East Anglia, UK. She has worked on various international research projects, focusing on the Arts of West Papua, Polynesia and Fiji, and material heritage of British missions in the Pacific. Her research has resulted in a variety of exhibitions and publications. Exhibition projects include Pacific Encounters: Art and Divinity in Polynesia 1760-1860 (Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, 2006; Museé du quai Branly, 2008), Art and the Body (Fiji Museum, 2014), and Fiji: Art and Life in the Pacific (Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, 2016; LACMA, 2019). Book projects include Collecting Kamoro (Jacobs 2012), Trophies, Relics and Curios? Missionary Heritage from Africa and the Pacific (Jacobs, Knowles and Wingfield 2015) and This is not a Grass Skirt: on fibre skirts (liku) and female tattooing (veiqia) in nineteenth century Fiji (Jacobs 2019).

Notes

1 This disease was named after G.A. Hansen, the Norwegian doctor who identified mycobacterium leprae, the bacterium causing leprosy, in 1873. While the term Hansen’s disease is widespread now, it was not used during Father Damien’s time. Therefore the terms leprosy or the Hawaiian translation ma‘i lepera will be used interchangeably, unless referring to more recent times.

2 The spelling of Moloka‘i varies and often the ‘okina or glottal stop is not used. This article follows the spelling as recorded by Pukui and Elbert (Citation1966, 20).

3 Consulted archival sources were mainly in Dutch, French, English and some Hawaiian (see bibliography); for the latter a translator was consulted.

4 For recent research on Catholic mission museums, see Loder-Neuhold (Citation2019).

5 For the latest ICOM definition of a museum, see https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/#:∼:text=NetworkICOM%20approves%20a%20new%20museum%20definition&text=The%20new%20text%20reads%3A,exhibits%20tangible%20and%20intangible%20heritage.

6 For scholarship on the role of material culture in missionary encounters in the Pacific region, see, amongst others, Thomas Citation1991, Gardner Citation2006; Diaz Citation2010, Jacobs Citation2014, Jacobs and Wingfield Citation2015.

7 There is a plethora of biographies about Father Damien (e.g. Daws Citation1973; Eynikel Citation1999; Volder Citation2010).

8 Archives Damiaan Vandaag.

9 Author’s translation from Dutch and French, see https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-father-damien-a-catholic-missionary-and-priest-with-the-kalawao-girls-98454369.html.

10 This was made public knowledge, cf. TV footage of Father Damien’s return in 1936 (Aankomst Damiaan 3 mei 1936, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2LP6NRKWgo) and newspaper articles (Tijd, July 5, 1937).

11 In addition to Father Damien, others were recognized by the Roman Catholic Church. Mother Marianne Cope (1838-1918), a Franciscan nun who lived at the Kalaupapa Settlement between 1888 and 1918 and oversaw the medical treatment of women and children at the Charles Reed Bishop Home, was beatified in 2005 and canonized in 2012 (Hanley and Bushnell Citation1991). In 2010 the Roman Catholic Church presented the Polynesian Cultural Center on O‘ahu with a plaque commemorating Jonatana Napela (1813–79) of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and his collaboration with Father Damien (Woods Citation2008). In 2015 the Joseph Dutton Guild was established by the Diocese of Honolulu to start the beatification process of Joseph Dutton (1843–1931), who had arrived in 1886 in Moloka‘i to help Father Damien and founded the Baldwin Home for men and boys.

12 Relics have a wider use beyond Christianity (cf. Bagnoli et al. Citation2010; Hooper Citation2014).

13 See Adams (Citation2005) and Passiarello (Citation2005) for discussions on how houses of iconic people can become shrines and sites for religious experience.

14 Archives of the Picpus Fathers and Father Damien, Damiaan Vandaag, Leuven.

15 Archives of the Picpus Fathers and Father Damien, Damiaan Vandaag, Leuven.

16 The usual translation of the phrase is added to the text, but Hawaiian words have multiple meanings which can reveal deeper knowledge (see Basham Citation2008, 159).

17 Archives of the Picpus Fathers and Father Damien, Damiaan Vandaag, Leuven.

18 See a testimonial by Father Damien’s relative, Gustavine van Roost in Damiaan, mens of mythe:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=onMOofX_aXs.

19 In 1964 the Belgian Congregation donated a chasuble to the Honolulu-based Picpus Congregation that had plans to establish a museum devoted to Father Damien (Letter to Reverend Brendan Furtado, May 10, Citation1964).

20 For a Congregation reflection on the distribution of Father Damien’s body, see Macken (Citation1995).

21 These discussions mostly center on Belgium’s colonial past (see Goddeeris Citation2015; Stanard Citation2019).

22 Father Damien’s coffin is currently not on display.

- Adams, Walter R. 2005. “Saints and Health: A Micro-Macro Interaction Perspective.” In The Making of Saints: Contesting Sacred Ground, edited by James F.Hopgood, 169–186. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Adinolfi, Maria P., and Mattijsvan de Port. 2013. “Bed and Throne: The “Museumification” of the Living Quarters of a Candomble Priestess.” Material Religion9 (3): 282–303. doi:10.2752/175183413X13730330868915

- Aldrich, Robert. 2010. “Colonial Museums in a Postcolonial Europe.” In Museums in Postcolonial Europe, edited by DominicThomas, 12–31. London: Routledge.

- Ames, Michael. 1986. Museums, the Public and Anthropology. Ranchi: Ranchi University Press.

- Amundson, Ron, and O.Akira. 2010. “A Wholesome Horror: The Stigmas of Leprosy in 19th Century Hawaii.” Disability Studies Quarterly30 (3/4): 1–8. doi:10.18061/dsq.v30i3/4.1270

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. ed. London: Verso.

- Arweck, Elisabeth, and William J. F.Keenan. 2006. “Introduction: Material Varieties of Religious Expression.” In Materializing Religion: Expression, Performance and Ritual, edited by William J.F.Keenan, 1–20. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Bagnoli, Martina, Holger A.Klein, C.Griffith Mann, and JamesRobinson, eds. 2010. Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum.

- Barringer, Tim J., and TomFlynn, eds. 1998. Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture, and the Museum. London: Routledge.

- Basham, Leilani. 2008. “Mele Lāhui: The Importance of Pono in Hawaiian Poetry.” Te Kaharoa1 (1): 152–164. doi:10.24135/tekaharoa.v1i1.138

- Beccari, Camillo. 1907. “Beatification and Canonization.” In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02364b.htm.

- Bennett, Oliver. 2011. “Strategic Canonisation: sanctity, Popular Culture and the Catholic Church.” International Journal of Cultural Policy17 (4): 438–455. doi:10.1080/10286632.2010.544726

- Berns, Steph. 2016. “Considering the Glass Case: Material Encounters between Museums, Visitors and Religious Objects.” Journal of Material Culture21 (2): 153–168. doi:10.1177/1359183515615896

- Boon, Ruben, JaspersPatrik, J.Van der Meyden Klaas, Van HerckMyriam, and LucVints. 2015. Damiaan Daar Zit Muziek in! over Een Heilige en Een Muziekhandschrift. Leuven: KADOC.

- Boon, Ruben. 2018. “Een Klein Museum met een grote Missie.”Damiaan Vandaag, 25 April 2018 (https://damiaanvandaag.be/archieven/2316).

- Boon, Ruben, and JaspersPatrik. 2018. “Damiaanfoto Uit 1873 Geeft Geheimen Prijs.” Damiaan Vandaag (damiaanfoto-uit-1873-geeft-geheimen-prijs).

- Breitha, Olivia R. 1991. Olivia: My Life in Exile in Kalaupapa. Arizona: Arizona Memorial Museum Association.

- Buggeln, Gretchen T. 2012. “Museum Space and the Experience of the Sacred.” Material Religion8 (1): 30–50. doi:10.2752/175183412X13286288797854

- Cheung, Alexander T. M. 2018. “How Stigma Distorts Justice: The Exile and Isolation of Leprosy Patients in Hawaìi.” Asian Bioethics Review10 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1007/s41649-018-0042-3

- Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Courant. 1938. “Een Damiaan-Museum te Leuven.” Courant, February 16, 1938.

- Daws, Gavan. 1973. Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Diaz, Vicente M. 2010. Repositioning the Missionary: Rewriting the Histories of Colonialism, Native Catholicism, and Indigeneity in Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Edmond, Rod. 1997. “Leprosy and Colonial Discourse: Jack London and Hawaii.” Wasafiri12 (25): 78–82. doi:10.1080/02690059708589546

- Edmond, Rod. 2006. Leprosy and Empire: A Medical and Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eynikel, Hilde. 1999. Damiaan: de Definitieve Biografie. Leuven: Davidsfonds.

- Gardner, Helen. 2006. Gathering for God: George Brown in Oceania. Dunedin: Otago.

- Antwerpen, Gazet van. 1953. “Hawaïaans Missiemuseum Geopend te Tremelo.” Gazet van Antwerpen, June 18, 1953.

- Geary, Patrick J. 1994. Living with the Dead in the Middle Ages. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Giblin, John, ImmaRamos, and NikkiGrout. 2019. “Dismantling the Master’s House.” Third Text33 (4-5): 471–486. doi:10.1080/09528822.2019.1653065

- Goddeeris, Idesbald. 2015. “Colonial Streets and Statues: Postcolonial Belgium in the Public Space.” Postcolonial Studies18 (4): 397–409. doi:10.1080/13688790.2015.1191986

- Nieuws, Goed. 1954. “Hawaii in Tremelo, de Geboorteplaats Van de Apostel Der Melaatsen.” Goed Nieuws Voor de Vrouw30 (3): 2–3.

- Hanley, Mary L, and Oswald A.Bushnell. 1991. Pilgrimage and Exile: Mother Marianne of Molokai. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Harrison, Ted. 2006. Diana: The Making of a Saint. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Hartel, Heather A. 2006. “Producing Father Baker: Material and Visual Practices of Making a Saint.” Material Religion2 (3): 320–348. doi:10.1080/17432200.2006.11423054

- Sentinel, Hawaii. 1935. “Keep Father Damien’s Remains in Hawaii.” The Hawaii Sentinel, September 12, 1935.

- Henare, Amiria, MartinHolbraad, and SariWastell, eds. 2007. “Thinking through Things.” Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically. London: Routledge.

- Herman, R. D. K. 2001. “Out of Sight, out of Mind, out of Power: Leprosy, Race and Colonization in Hawai‘i.” Journal of Historical Geography27 (3): 319–337. doi:10.1006/jhge.2001.0325

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1935a. “New Koa Casket Being Prepared for Fr. Damien.” The Honolulu Advertiser, January 30, 1935.

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1935b. “Letters from the People: Strenuously Objects to Removal from Hawaii of Father Damien’s Body.” The Honolulu Advertiser, September 27, 1935.

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1935c. “Belgian Consul Enters Plea in Controversy over Damien.” The Honolulu Advertiser, October 4, 1935.

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1936a. “Catholic Bishop Pays Tribute in Rites at Grave.” The Honolulu Advertiser, January 28, 1936.

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1936b. “Hite to Plead for Three Idols.” The Honolulu Advertiser, December 4, 1936.

- Honolulu Advertiser 1936c. “Keep Them in Hawaii.” The Honolulu Advertiser, December 7, 1936.

- Honolulu Advertiser. 1936d. “Territory Reciprocates Idol Gift with Relic Collection.” The Honolulu Advertiser, December 8, 1936.

- Honolulu Star Bulletin. 1936a. “Opposition to Idol Removal Growing Here.” The Honolulu Star Bulletin, December 2, 1936.

- Honolulu Star Bulletin. 1936b. “An Appeal to Generosity.” The Honolulu Star Bulletin, December 5, 1936.

- Hooper, Steven. 2014. “A Cross-Cultural Theory of Relics: On Understanding Religion, Bodies, Artefacts, Images and Art.” World Art4 (2): 175–207. doi:10.1080/21500894.2014.935873

- Imada, Adria L. 2017. “Promiscuous Signification: Leprosy Suspects in a Photographic Archive of Skin.” Representations138 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1525/rep.2017.138.1.1

- Imada, Adria L. 2018. “Lonely Together: Subaltern Family Albums and Kinship during Medical Incarceration.” Photography and Culture11 (3): 297–321. doi:10.1080/17514517.2018.1465651

- Inglis, Kerri A. 2013. Ma‘i Lepera: Disease and Displacement in Nineteenth-Century Hawai‘i. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Inglis, Kerri A. 2015. “One’s Molokai Can Be Anywhere”: Global Influence in the Twentieth-Century History of Hansen’s Disease.” Journal of World History25 (4): 611–627. doi:10.1353/jwh.2015.0007

- Inglis, Kerri A. 2017. “Nā Hoa o ka Pilikia (Friends of Affliction): a Sense of Community in the Molokai Leprosy Settlement of 19th Century Hawai‘i.” The Journal of Pacific History52 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1080/00223344.2017.1371223

- Jacobs, K. 2014. “Inscribing Missionary Impact in Central Polynesia: Mapping the George Bennet Collection (1821-1824).” Journal of the History of Collections26 (2): 263–276. doi:10.1093/jhc/fht038

- Jacobs, Karen, and ChrisWingfield. 2015. “Introduction.” In Trophies, Relics and Curios: Missionary Heritage from Africa and the Pacific, edited by KarenJacobs, ChantalKnowles and ChrisWingfield, 9–22. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Kakaliouras, Ann M. 2012. “An Anthropology of Repatriation: Contemporary Physical Anthropological and Native American Ontologies of Practice.” Current Anthropology53 (S5): S210–S221. doi:10.1086/662331

- Kanohokula, S. K. K. 1879. “Ka Poi Palaoa.”Kuokoa, March 15, 1879 (for translation see Nupepa blog: https://nupepa-hawaii.com/2012/10/03/poi-made-from-wheat-flour-in-kalawao-and-kalaupapa-1879/).

- Knichel, Julius P., SS.CC. 1980. “Damian-Museum in Tremelo.” Sonderdruk aus Deutsche Tagespost.

- Law, Anwei S. 2012. Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Le Hoang Ngoc, Yen. 2018. “The Nuns of Lepers: Compassion, Discipline and Surrogate Parenthood in a Former Leper Colony of Vietnam.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology19 (4): 350–366.

- Belgique, Libre. 1937. “Un Musée du Père Damien.” La Libre Belgique, July 18, 1937.

- Loder-Neuhold, Rebecca. 2019. “Crocodiles, Masks and Madonnas: Catholic Mission Museums in German-Speaking Europe.” PhD thesis., Uppsala: Department of Theology (http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1363017&dswid=-5108.).

- Lonetree, Amy. 2012. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Luker, Vicky, and JaneBuckingham. 2017. “Histories of Leprosy: Subjectivities, Community and Pacific Worlds.” The Journal of Pacific History52 (3): 265–286. doi:10.1080/00223344.2017.1379124

- Macken, Paul SS.CC. 1995. De Gestoorde Rust Van Pater Damiaan. Kalawao 1936-Kalawao 1995. Leuven: Damiaan Documentatie en Informatiecentrum.

- Macklin, June. 2005. “Saints and near-Saints in Transition.” In The Making of Saints: Contesting Sacred Ground, edited by James F.Hopgood, 1–22. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Marten, Michael, and KatjaNeumann. 2013. “Introduction.” In Saints and Cultural Trans-/Mission, edited by MichaelMarten and KatjaNeumann, 1–6. Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag.

- Miller, Maureen C. 2015. “Catholic Material Culture. An Introductory Bibliography.” The Catholic Historical Review101 (1S): 99–106. doi:10.1353/cat.2015.0022

- Moblo, Pennie. 1997. “Blessed Damien of Moloka‘i: The Critical Analysis of Contemporary Myth.” Ethnohistory44 (4): 691–726. doi:10.2307/482885

- Morgan, David. 1998. Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Damiaan, Museum Pater. n.d. Damiaan-Museum/Tremelo. Leuven: Paters H.H. Harten.

- Nahaielua, Henry. 2006. No Footprints in the Sand: A Memoir of Kalaupapa, with Sally-JoBowman. Honolulu: Watermark Publishing.

- van den Dag, Nieuws. 1937. “Herinneringen Aan Pater Damiaan.” Nieuws van den Dag July 18, 1937.

- Nieuwsblad. 1968. “Oudstrijder Brengt Foto’s Terug….” Nieuwsblad, April 3, 1968.

- Nohelani Teves, Stephanie. 2018. Defiant Indigeneity: The Politics of Hawaiian Performance. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Osselaer, Tine van. 2018. “Valued Most Highly and Preserved Most Carefully’: Using Saintly Figures’ Houses and Memorabilia Collections to Campaign for Their Canonisation.” Museum History Journal11 (1): 94–111.

- Paine, Crispin. 2013. Religious Objects in Museums: Private Lives and Public Duties. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Passariello, Phyllis. 2005. “Desperately Seeking Something: Che Guevara as Secular Saint.” In The Making of Saints: Contesting Sacred Ground, edited by James F.Hopgood, 75–89. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Patteet, Lucas. 1963. Muzeüm Pater Damiaan, Tremelo. Antwerpen: Vlaamse toeristenbond.

- Peters, Edward N. 2001. The 1917 or Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena, and Samuel H.Elbert. 1966. Place Names of Hawaii and Supplement to the Third Edition of the Hawaiian-English Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Schorch, Philipp, et. al. 2020. Refocusing Ethnographic Museums through Oceanic Lenses. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Smets, Gaby, and LeoJammaers, eds. n.d. Pater Damiaan: Het Verhaal Van Een Man Die Melaats Werd Met de Melaatsen. Leuven: Mensen Onderweg.

- Stanard, Matthew. 2019. The Leopard, the Lion, and the Cock: Colonial Memories and Monuments in Belgium. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Standaard. 1953. “Officiele Inwijding Van Het Hawaiiaans Museum te Tremelo.” De Standaard, June 20, 1953.

- Stevenson, Robert L. 1890. Father Damien—An Open Letter to the Reverend Dr. Hyde of Honolulu. (http://robert-louis-stevenson.org/).

- Stocking, George W. 1985. “Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture.” History of Anthropology 3. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Strange, Carolyn. 2004. “Symbiotic Commemoration: The Stories of Kalaupapa.” History and Memory16 (1): 86–117. doi:10.2979/his.2004.16.1.86

- Te RangiHiroa [Buck, Peter H.]. 1964. Arts and Crafts of Hawaii: XI. Religion. Honolulu: B.P. Bishop Museum Press.

- Thomas, N. 1991. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Tijd 1937. “Sinds Pater Damiaan Terug is….” De Tijd—Gent, July 5, 1937.

- Vaughan, Meghan. 1991. Curing Their Ills: Colonial Power and African Illness. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Volder, Jan de. 2010. The Spirit of Father Damien: The Leper Priest - a Saint for Our Time. With Foreword by JohnAllen. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Volk 1952. “Geboortehuis en Museum Van Pater Damiaan te Tremelo.” Het Volk, May 16, 1952.

- Volksblad, Vrije. 1947. “Hier Werd Geboren Pater Damiaan, Apostel Der Melaatsen.” Vrije Volksblad, May 27, 1947.

- Walsham, Alexandra. 2010. “Introduction: relics and Remains.” Past & Present206 (Supplement 5): 9–36. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtq026

- Wellens, Cyriel. 1959. “Het Hawaïaans- en P. Damiaanmuzeüm te Tremelo.” De Brabantse Folklore. Tijdschrijft Van de Dienst Voor Geschiedkundige en Folkloristische Opzoekingen Der Provincie Brabant143: 407–436.

- Wharton, Annabel J. 2006. Selling Jerusalem: Relics, Replicas, Theme Parks. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- WHO 2018. Leprosy: Fact Sheet. Last modified 14 March 2019. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leprosy

- Woods, Fred E. 2008. “Most Influential Mormon Islander: Jonathan Hawaii Napela.” Hawaiian Journal of History42: 135–157.

- Woodward, Kenneth L. 1996. Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Become Saints, Who Do Not and Why. London: Touchstone.

- Young, James E. 2016. The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.