Abstract

The greatest architectural monument of Szeged’s Jewish community is the New Synagogue (1900–1903), designed by Lipót Baumhorn (1860, Kisbér—1932, Budapest). He designed twenty-six synagogues in the former Hungarian Kingdom and was known as the most successful synagogue architect in Europe. In Szeged, his most special buildings are the synagogue, the community’s headquarters, and the Jewish cemetery’s ceremonial hall. During the synagogue’s construction, Baumhorn worked closely together with Dr. Immánuel Löw (1854, Szeged – 1944, Budapest), rabbi and scholar, who applied his immense knowledge in the decoration of the synagogue. Löw belonged to the Neolog denomination of Hungarian Judaism and designed the synagogue garden as an organic part of the building, presenting the flora of both Israel and Hungary. The Neolog movement brought a transformation in the sacred spaces of the synagogue, moving of the bimah to the Eastern end of the synagogue, introducing the use of an organ and a choir, and defining towers on the outside. The synagogue and its garden stand alone on the global stage, thanks to its extraordinary botanical decoration system that is both distinctively designed and rich in symbolic meaning, drawing inspiration from motifs found in the Hebrew Bible, all due to the remarkable botanical expertise of the rabbi, representing a unique and materialized fusion of Neolog Jewish ideals, Hungarian heritage, and architectural excellence. In our study, we present Szeged’s new synagogue and its synagogue garden from an architectural and cultural-historical point of view, summarizing the emergence of Jewish ideas in the turn-of-the-century architecture and the transformation of the use of spaces.

Introduction: The History and the Importance of the Jewish Population in Szeged

The renowned Jewish congregation of Szeged stands as the largest Jewish community in southern Hungary and one of the most important in central Europe. It was founded in 1785 and, at its peak in the 1920s, it had 7000 members, making it the third-biggest Jewish community in Hungary. Nowadays, just 300 people remain members, a stark decline primarily attributed to the devastating impact of historical events such as the Holocaust and the post-war Communist period. These traumatic episodes have profoundly shaped the community’s demographic landscape, significantly reducing its numbers. Yet, the Jewish population of Szeged has a vibrant history, both intellectually and culturally. It is one of the very few countryside communities where, after 1945, Jewish religious and communal life continued and is still taking place. The community’s survival made it possible for it to retain its valuable collection of documents and a rich archive of material memories (Szeged Jewish Archive, SzJA).

Szeged was a primary focal point of Neolog Judaism and thus a prime locus (outside of Budapest) of the attempts of Jews living in Hungary to acculturate into mainstream, Hungarian-speaking urban culture after the creation of Austria-Hungary in 1867. Jewish community members were active in Szeged’s scientific, economic, industrial, religious, cultural, architectural, artistic, educational, and charitable communities (Karády Citation1990, 9–43). By 1840, 800 Jewish men were registered in the town, and the rabbis started keeping vital registers from 1844.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Jewish integration into non-Jewish society had reached a high degree, thanks to their assimilation strategies. The majority of Szeged’s Jewish population took on Hungarian political and cultural identity through schooling and by choosing the Neolog denomination of Judaism in Hungary. The more progressive and pro-reform Neolog movement enabled them to leave behind Orthodox lifestyle practices, which were often insurmountable obstacles to attaining a rise in their status in Hungarian society. Approximately 40% of Szeged’s Jewry belonged to the middle-class intellectuals (including office workers), which is well above the average both compared on a national level and to other cities with a Neolog majority of Jewry (Karády Citation1990, table nr 3). The wealth of the industrial and merchant citizens was also higher, and the Jews of Szeged can be considered more modern and bourgeois than their fellows living in other cities. On March 12, 1879, Szeged was flooded, leaving only 265 of nearly 6,000 houses intact. In the three phases of the city’s reconstruction (1880–1914), there were many Jewish clients among the builders: mainly merchants, doctors, and lawyers.

In 1801, the community’s organizational and operational rules were renewed, and between 1800 and 1803 the first house of prayer was built in the Korona street (today Hajnóczy street). Twenty years later, the building became too small, so in 1825 the community decided to build a new synagogue. This synagogue, known today under the name “the old synagogue,” was built between 1840 and 1843 in Neoclassicist style (designed by father and son, Henrik and József Lipovszky), on the same plot where the previous building was located (today: Hajnóczy u. 12.). The synagogue was inaugurated on May 19, 1843, by the chief rabbi of Pest, Arszlán Schwab, and from 1850 it was led by chief rabbi Lipót Löw (1811, Czerna Hora—1875, Szeged). Arszlán Schwab even brought along a choir to the inauguration, which was regarded as a progressive innovation at that time (Löw & Kulinyi Citation1885, 161).

The flood of 1879 seriously destroyed the building, but Immánuel Löw managed to save the Torah scrolls (Hidvégi Citation2019, 19). After the renovation and the extension of the bimah [the central platform for reading the Torah], the synagogue had seats for 400 men and 300 women in an area of 344 square meters (LöW and Kulinyi Citation1885, 162). The bimah was in the middle. Once the New Synagogue was built, the previous synagogue became the so-called old or small one, or the “men’s synagogue” (Ábrahám Citation2016, 21). In 1977, the Szeged Jewish Community had to sell the site to the Hungarian state. Since 1992, it has been owned by Szeged city. Currently, it is used by the MASZK Theater Association (Apró Citation2011, 15–17).

The article aims to demonstrate the profound architectural and cultural significance of Szeged’s New Synagogue, within the broader context of turn-of-the-century architecture and the evolving Jewish identity, showcasing its unique features, collaborative aspects, and its role in the transformation of sacred spaces, notably highlighting the integration of Neolog ideas and the presentation of the synagogue garden as a symbolic reflection of both Israeli and Hungarian flora.

The Builders of the New Synagogue

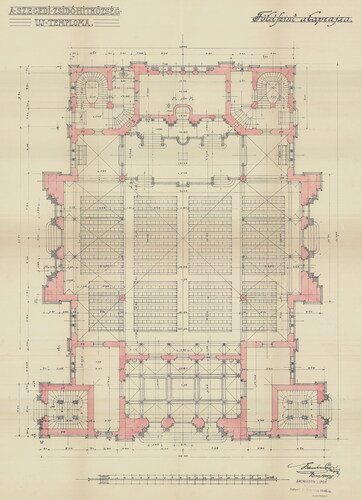

The New Synagogue of Szeged was built between 1900–1903 in a historical and Art Nouveau style. It is the second largest in Hungary (1340 seats) with a central dome of 48,5 meters (). It was built by architect Lipót Baumhorn, under the inspiration of the city’s chief rabbi, Immánuel Löw. Without doubt, Baumhorn’s masterpiece was the Neolog New Synagogue in Szeged, which, in addition to its complex form and its large size, was made unique by its symbolic depiction of the Jewish religion. To this day, the synagogue has borne witness to the local Jewry’s flourishing at the turn of the twentieth century. With its domed mass of four towers, it rises far above the surrounding buildings and takes its rightful place among the city’s religious buildings.

Lipót Baumhorn (1860–1932) was the most successful synagogue designer of his time, designing twenty-six synagogues during his career. In Europe, he was uniquely productive, designing not only in oriental but also in Art Nouveau and Protomodern style, for four decades. Baumhorn’s architectural office produced five tombstones and about fifty plans for secular buildings beside the designing of synagogues and the synagogue renovations (Oszkó Citation2020).

Immánuel Löw (1854–1944) was, without doubt, Szeged’s, if not Hungary’s most important Neolog rabbi and scholar. He was not only significant as a rabbi but also as a scientist in various fields. He was educated in his native town and in addition to his studies at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (College for Jewish Studies) in Berlin, he also studied Semitic linguistics at the University of Leipzig, Germany. In 1879, he submitted his doctoral thesis on plant names in Aramaic (Aramäische Pflanzennamen) for which he received his PhD. In the same year, he graduated as a rabbi and started his work in Szeged, where he officiated until 1944. Löw, an enthusiastic botanist, collaborated closely with Baumhorn and had the architect incorporate numerous intricate floral and plant designs into the detail of the extraordinarily ornate decoration of the synagogue (Hidvégi Citation2019).

The synagogue building was mostly untouched during WWII, although tragically the majority of its congregation was murdered in the Holocaust. It remained empty but was still owned by the tiny surviving Szeged Jewish community. Between 2015 and 2018, external renovations and reconstruction of the garden took place, and in 2017 the new synagogue, whose exterior was refurbished, was given a new roof. The interior has not been upgraded so far due to a lack of funds.

The New Synagogue as an Expression of the Neolog Values

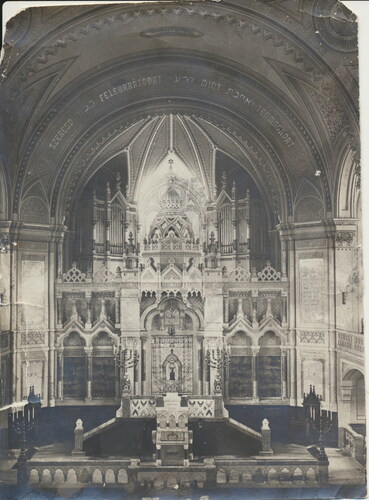

On May 19, 1903, chief rabbi Immánuel Löw inaugurated the new synagogue. Both the chief rabbi and the architect referred to the building as a “Jewish temple” (Hun. zsidótemplom, cf. Judentempel in German) ( and ). Both considered Hungary as their homeland. This alignment with Hungarian identity coincided with the 1895 decree that proclaimed religious equality, further solidifying their connection to Hungary. Baumhorn sent his application to the anonymous tender for the synagogue building project with the pseudonym “God and Homeland,” which might be regarded as a reference to his Neolog ideology.

These two homelands—the ancient one in Eretz Israel and the present one in Hungary—are also visible in the garden planted around the synagogue, for which Löw selected plants that were common in the land of Israel and other plants from Hungary. The synagogue’s interior decoration also emphasized the new homeland’s idea: the inscription on the triumphal arch over the Torah ark [Aron Kodesh] was written in Hebrew and Hungarian: Love your fellow as yourself! (Lev 19:18). This quote was the first synagogue wall painting written in the Hungarian language, and it was uncommon at the time to include inscriptions in the local vernacular on the walls of the synagogue.

The Szeged New Synagogue was built according to the traditions and rules of the Neolog movement, officially established in 1868. The progressive Neolog or Congressional movement had its root in the Jewish Enlightenment movement, the Haskalah (Silber Citation1987, 107–157). The use of space for experiencing religion was transformed according to the reforms. The manifestation of Neolog Judaism in the synagogue is immediately striking from the building’s exterior: four tall towers, which are characteristic of Neolog synagogues in Hungary, were added during the renovation. This can be regarded as an attempt to adapt to the appearance of Christian churches, and even to surpass them (Pejin Citation2008).

Adherents to Neolog Judaism shifted their focus from everyday religious practices at home to prioritize religious life within the synagogues. The sacredness of the latter increased in the eyes of laypeople, and it became the most important, if not the exclusive, place of Jewish religious experience. The importance of the individuals who played a role there also increased, and the differences between the individuals became more significant. Consequently, liturgical roles became differentiated: specialists or experts in synagogues became more active, and the average layperson became more passive. This brought along a transformation also in the space: most of the attendees became spectators, while only a few men had tasks to be carried out (Biró Citation2018, 76–77).

The arrangement of the synagogue’s space for prayer also reflected the needs of Neology. The bimah was moved to the Eastern side instead of its traditional place in the middle, which had been the custom since the Middle Ages. In architectural terms, this meant that the location for reading the Torah in Neolog synagogues was in the front, on an elevated podium with the Torah-reading table, the stand of the shaliach tzibbur (the leader of the prayer), the Torah Ark, and the seats of the rabbi and the members of the board. In keeping with the placement of the bimah, and as a change from previous practice, the benches all faced the same direction: east. This means that the space loses its central organization, but this is somewhat balanced by the central dome, which is typical of Neolog synagogues.

Since it became possible to use an organ and a choir during the service, a place for these had to be established. Thus, above the Torah ark, there is a loft for the organ and the choir:

The organ was built in the workshop of the organ builder C. Lipót Wegenstein in Timişoara, according to the pneumatic pipe system. It is divided into two manuals and a pedal, with 10 variations in the first manual, 7 in the second and 4 in the pedal (Löw Citation1903, 11).

Weddings could also be conducted in the Neolog synagogues, thus the construction of two additional rooms became necessary: one for the bride and the other one for the bridegroom, where they could prepare and wait for their wedding to be conducted. In the New Synagogue of Szeged, these two rooms were placed at the eastern end of the building. The women in the Szeged New Synagogue were seated strictly in the galleries—but because the synagogue is Neolog, there are no visual barriers (mechitza) to separate them from men, unlike in Orthodox synagogues. The lowering of the parapet lattice in the women’s gallery required only minor interior remodeling inside the building.

All these features have been used in the synagogues of Reform Jewry since the middle of the nineteenth century (e.g. Budapest, Dohány Street Synagogue, 1854–1859, L. Förster). Thus, by the turn of the twentieth century, these were not novelties anymore. According to one scholar, “The Hungarian Neologs broadly followed the achievements of the German Reform Movement (Haskalah), but due to local circumstances and the larger presence of traditional Jews, they were more conservative” (Klein Citation2017, 690). Thus, Neology was, and to this day is, a specifically Hungarian type of Judaism.

History of the Szeged New Synagogue from Planning to Inauguration

The Szeged New Synagogue was built on the plot next to the former “old” synagogue. The increase of the Jewish population in Szeged in the last quarter of the nineteenth century suggested that the community would soon need a larger place of worship. In 1884, the board formed a movement to raise funds for the new synagogue to be built. Additionally, from 1891 the congregation also established foundations, and a considerable sum was collected by 1897.

Unlike many other European Jewish Archives, the community’s archives survived mostly intact despite the destructive forces of the Holocaust and WWII. With the help of these archival documents, the building’s history can be reconstructed in detail. The community issued a tender for constructing a new synagogue in 1898, for which ten applications were received. On April 23, 1899, the committee in charge—including Löw and representatives of the architectural profession (among others, Ignác Alpár) and the city—selected Lipót Baumhorn’s (anonymous) plan. Ödön Lechner, the founder of the Hungarian Art Nouveau movement, probably supported the third prize-winning plan with the pseudonym “And There was Light,” which was eventually built in Szabadka (Subotica) in 1901–1903 by Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab. Klein notes that Baumhorn’s “enriched freestyle” of Ödön Lechner—in whose office Baumhorn worked in 1883–1895—lacks Lechner’s strength, and thus Baumhorn was still a mere follower in this period. He found his voice only a decade later. As architecture historian Rudolf Klein has stated, “the public adored the building, unlike Lechner who would have liked Dezső Jakab and Marcell Komor to win the competition. However, Rabbi Löw could accept only the well-established Lipót Baumhorn, regardless of his mannerism and predilection to overstatement” (Klein Citation2017, 380).

It is probable that the committee chose Baumhorn’s plan on Immánuel Löw’s suggestion (SzJA 531/99., 100/99) since the chief rabbi was well acquainted with the architect’s work. Baumhorn refused to participate in the tender twice. When he finally decided to participate, the community had to extend the deadline of submission so that the architect could apply (SzJA 1899_056, 063, 074, 077, 088). Baumhorn had been involved in the construction of the Szeged town hall already in 1883, and his relationship with Löw became closer in 1888 when Löw inaugurated the synagogue in Esztergom that Baumhorn had designed.

Lipót Baumhorn’s plans depicted a monumental building with an impressive dome that could acquire a dominant role in the cityscape. The New Synagogue, together with the adjacent garden, was designed to occupy an entire block of plots. His design could not be classified by a specific architectural style, as it freely incorporated elements from the Revival styles (such as Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Gothic), while the other two award-winning designs represented a definite Art Nouveau direction. This mixture of styles might have been one of the decisive factors for the committee: a community proud of its assimilation did not want to commit itself to any contemporary architectural trends, and instead chose a design better suited to the taste of the citizens—not to mention their trust in an architect who was already experienced in synagogue construction (Oszkó Citation2020). Löw put it into words:

The character of the building’s architecture is rather free and individual; it does not submit itself to a specific strict stylistic direction. Its base draws from a medieval trend, but its realization and its details are the products of an entirely individual concept and in some respects an expression of the assimilating ability of modern Jewry (Löw Citation1903, 5)

Rabbi Immánuel Löw worked closely with Baumhorn on all details of the decoration of the new synagogue. Every painted panel, every pane of stained glass, every inscription, every carving was imbued with a symbolic meaning that Löw explained at length in detailed accounts. […] It was his [Löw’s] knowledge and interest in botany and Jewish symbolism that put the stamp on the lavish decoration of Baumhorn’s great synagogue (Gruber Citation1994, 152).

True to the principles of Neology, Löw commissioned handicrafts from Hungarian craftsmen, thus the synagogue was materialized by Hungarian-speaking experts:

All our crafts and industrial works are a tribute to the development of domestic industry. We are pleased to note that there was no task that the domestic industry would be unable to solve, and if we now look at the finished works of art, that of the glass painter, the painter, the organ builder, the metalworker, the stone carver, the bookbinder and the woodworker, we are very pleased to see that all these works were implemented by the local and the Budapest industry with impeccable and partly artistic perfection (Löw Citation1903, 13).

A Symphony of Content and Form: The Message of Judaism

The synagogue, with its square prayer space, foyer on the west, and organ loft on its eastern side, is supported by a steel structure (). The exterior suggests a cross-shaped floor plan, yet the interior is relatively homogenous though not exactly central. Despite the lateral expansion of the space on the gallery level, a longitudinal Catholic character can be still felt when standing inside (Klein Citation2017, 379).

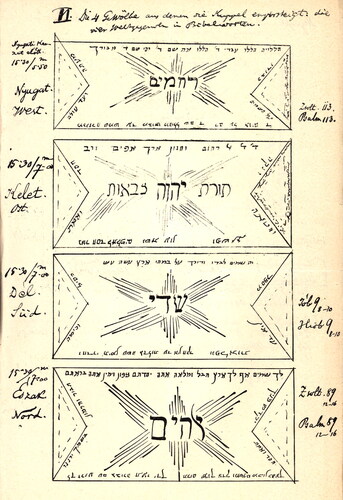

FIG 4 A sketch of the inscriptions on the barrel-vaults, written and drawn by Immánuel Löw, 1902. © Szeged Jewish Archive.

The plan is based on four central columns, which carry the vaults, the dome, and the rooftree rising above the 30 × 30 meter interior. The inner dome is connected to the main columns by pendentives on which the words Torah (תורה), worship (עבודה), piety (חסדים) and practice of acts (גמילות) glow in golden fields. The three concepts written with four words can be found together in Pirkei Avot: “Shimon the Righteous was one of the last of the men of the great assembly. He used to say: the world stands upon three things: the Torah, the Temple service, and the practice of acts of piety.”Footnote1 The four columns supporting the synagogue’s dome mirror the pillars of Judaism in one’s life: Torah study, worship, and acts of charity, as described by Löw:

The connection between the purpose and the building’s division was highlighted by connecting the four massive barrel vaults surrounding the dome with the four main prayers, and one or two words indicating these in golden letters in the middle of the vault (Löw Citation1903, 6).

The Szeged New Synagogue has a unique position on the world stage, thanks to its exceptional botanical decoration system characterized by distinctive design and profound symbolic significance, inspired by motifs from the Hebrew Bible, all attributed to Löw’s remarkable botanical expertise. The rabbi also planned a crucial role for the decorations of the corner vaults: the cross-vaulted fields are decorated with plants symbolizing the books of the Tanakh as Löw described these references:

The four parts of the Scripture are symbolized by the four upper corners, each with a characteristic, colorful plant from that part of the Bible where it is mentioned. The Torah is represented in the southeast by a holy bramble (Rubus Sanctus Schreb.), the first prophets are represented in the northeast by the Colocynth [bitter apple/cucumber, Citrullus colocynthis] (2 Kings 4:39), the last prophets are referred to in the northwest as the miracle tree of the prophet Jonah [Ricinus], and the sacred documents are represented in the southwest by a walnut tree mentioned in the Song of Songs. The oral law and the historical development are represented in the Western vaults with these plants from the Mishna: the colorful holy bramble and the oleander [nerium, Nerium oleander, Psalm 1,3] as well as the nymphaea [water lilies], which form a white border on a blue background (Löw Citation1903, 6). ()

The glass dome symbolizes the revealed law and its historical development. In the center, beams are starting from the words “let there be light,” in the middle fields, there are the books of the Scripture, each symbolized by a plant mentioned in it (Löw Citation1903, 6).

The Torah ark is crowned by an ornate small dome reminiscent of the enormous dome of the synagogue (). The organ loft is located above the Torah ark and bimah facing east, the painting of which evokes the starry sky. The mizrach—the wall of the synagogue facing east—is tremendously ornate, composed of historicizing medieval, Orientalizing, and Art Nouveau elements topped by a scaled-down copy of the dome. For the Torah ark, Löw ordered shittah wood (Acacia seyal) from the land of Israel.

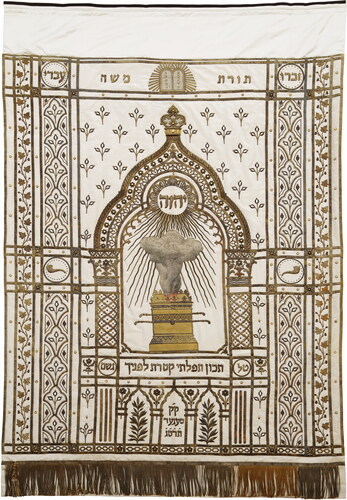

FIG 6 The mizrah (Eastern wall) and the Torah ark of the New Synagogue with the parochet (richly ornamented curtain covering the Torah Ark) designed specifically for the inauguration. © Hungarian Jewish Archives F97.144.

The building of the synagogue in Szeged crowned the great oeuvre of architect Lipót Baumhorn, who paid full attention to the smallest details, taking care to ensure that the interior matched the exterior. The Szeged Women’s Association provided the financial support for the furnishing of the synagogue with ritual textiles, and sets of Torah mantles, tablecloths, wedding canopies, Torah curtains (parochets) were made. The old textiles were restored, and new items were made with gold embroidery companies in Budapest. Lipót Baumhorn and Immánuel Löw designed a set of ritual textiles for the inauguration (SzJA inv. nr. 01.01.2020–02) together with its accessories and negotiated with prestigious gold embroidery workshops in Budapest. The parochet (Torah ark curtain) was made of white silk and embroidered with gold thread, with a matching kapporet (valance) and a Torah cover (Hamar Citation2014, Bányai Citation2017, Bányai, Katkó-Bagi and Pataricza Citation2023). They also designed a matching bimah cover, but it got lost (Bányai Citation2017, 28). József Schlesinger (1871–1933) was the market leader in the publication of books for liturgical purposes (prayer books, haggadahs), and he produced these textiles. He also maintained an embroidery studio and was asked to prepare the necessary ritual textiles for the inauguration of the synagogue (Bányai Citation2017, 9). On the parochet, under an arch of the same shape as the synagogue’s dome, the altar of incense is visible, surrounded by the ancient columns of Jachin and Boaz (2 Chron 3; 1 Kings 7:21) (). The smoke rising from the top of it is an illustration of Psalm 141:2, which was most likely suggested by Löw: תכון תפלתי קטרת לפניך (Take my prayer as an offering of incense) The top inscription of the curtain concerning the Torah (Malachi 3:22): זכרו תורת משה עבדי (Be mindful of the Teaching of My servant Moses).

Windows: Scenes of Everyday Life and Holidays

Through the stained-glass windows that fill the ten openings on the ground floor and the giant windows on the gallery, Löw wanted to symbolize certain motives of the Jewish calendar (Frauhammer and Szentgyörgyi Citation2020, Varga Papi Citation2021, Oszkó and Pataricza forthcoming) (). The Szeged Jewish Archive still has the sketches and drawings for the decorative paintings and those of the windows in German and in Hungarian languages (SzJA 1902_457_007_01–13). The holidays were visualized in ten scenes on the ground-floor windows, and these are repeated in the two large, three-lobed windows of the gallery. Due to the tradition of aniconism (i.e. the ban of the depiction of God and humans) in Judaism, and thanks to the extraordinary botanical knowledge of Löw, the holidays were displayed using a set of symbols consisting only of plants and objects.

FIG 8 The visualisation of Shabbat on the first window in the north-eastern wall © Ágnes Ivett Oszkó.

This first window on the south-eastern side symbolizes everyday life and work. Opposite to it, the first window in the northeast depicts the traditions connected to Shabbat. The inscription is a quote from the Lecha Dodi song, recited at Kabbalat Shabbat: לכה דודי / לקראת כלה /בואי כלה/ (Go forth, my love to meet the bride. Come forth, bride; come forth, bride!). Pesach is visualized on the windows on the southern side. At the top a seder plate is visible, under it there are two festive cups and the inscription which is divided on the two windows: זמן חרתנו (The time of Our Freedom), and on the large panes the bundles of papyrus growing out of the Red Sea, alluding to the liberation of the Jews from Egypt. Shavuot is shown on the second two-part window on the northern side. On the top window, the tablets of Moses are visible with the stone tablets. The inscription under it says זמן מתן תורתנו (the time of the giving of our Torah). In the main fields, the Nile acacia’s flowering branches refer to the ancient Ark of the Covenant (Oszkó and Pataricza, forthcoming).

The skylight windows above the side gates focus on the High Holidays with simple floral symbols. On the southern side, Rosh Hashanah is visualized with two shofars, the red flower of a pomegranate (as a symbol of sin), and a white lily (representing forgiving), while in the northern side in Yom Kippur is pictured, with the inscription: סלחתי [I forgive] and again a pomegranate flower and a white lily.

The two tablets on the fourth window on the southern side symbolize Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles), with the inscription: בסכת תשבו (Sit in tents!). Opposite to this window, on the northern side, Shmini Atzeret is visualized with the messages: אלוקי הרוחות (God of spirits) and הושיעה נא (help us). The last set of windows on the southwestern side visualizes the holidays of freedom and joy. In the center of the three-parted windows of Purim and Hanukkah, the blue-white flag of the Maccabees is visible, symbolizing the victory over the Seleucid Empire in 165 BCE (with the inscription על הנסים for the miracles) and the re-inauguration of the Temple in Jerusalem. Löw provided insight into the symbolism: “In the twin windows of the holidays of joy, the Maccabean heroes’ memory is visualized who won by fighting for faith and their homeland” (Löw Citation1923, 1:146). On the right, Purim is symbolized by the crown of Mordechai and the scroll of Esther (Megillat Esther) with the inscription אודה ושמחה (rejoicing and glory); on the left Hanukkah, the Feast of Light is visualized with a sealed oil jug and a copper Hanukkiah: וששון ויקר (and joy and honor). The fifth window on the north commemorates the two demolitions of the Jerusalem Temple (Tisha Be ‘av, in 586 BCE and 70 CE). In the inscription field of the window, a quote from Psalms 137:5 can be read: אםÖ¾אשכחך ירושלם תשכח ימיני (If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right-hand wither).

A colossal window commemorating the historical event of the Szeged flood was designed to be placed on the western porch, above the main entrance. At the top, there is an inscription in the frontlet [tzitz] of the high priest: קדש ליהוה (Holy to the Lord, Ex 39:30) beneath which is the jeweled breastplate of the high priest [choshen], menorot, silver horns, and blessing priestly hands. Below these, on the large panes the old, Neo-Classical style synagogue is visible, which was covered during the 1879 great flood of Szeged, and next to it is a simplified drawing of the new synagogue. Immánuel Löw summarized the purpose of the whole building as follows:

This is what this new building is announcing: it does not want to be a soulless mass of stone, but it proclaims its destiny in its division, the times that need to be devoted to prayer at sunrise, sunset, midday glare, evening twilight in the four directions. It proclaims in its ancient rows of letters the basics of morality, such as the respect for parents, the pursuit of peace among humans, the act of mercy, and the understanding of the [God’s] words. The understanding of the words is proclaimed on the tablets of the Ten Commandments on the altar [bimah], and the understanding of the all-pervading message in the heart of the Scripture, which is laid down in the middle book Moses [the third one] in the nineteenth chapter and which culminates in both the arch above the altar [bimah] and the moral thinking of man: ואהבת לרעך כמוך - love your fellow as yourself! (Löw Citation1923, 1:147)

From Cedar Trees to Poplars: Immánuel Löw’s Synagogue Garden

Synagogues rarely stand in the middle of gardens or parks, yet this is the case in Szeged, and it is by no means a coincidence. Immánuel Löw was able to apply his knowledge to both the synagogue’s iconography and the plants in the garden. The park and the synagogue are a united entity, neither of which can be understood without the other.

The chief rabbi planned a park with plants from the land of Israel and Hungary around the synagogue. The area bordering the schoolyard was covered with rose bushes. The garden had almond trees, figs, grapes, peaches, and cypresses, regarded as plants from the land of Israel, while the thujas, ambers, firs, and yews represented the flora of Hungary. The list of plants was published in detail in the Bulletin of the Jewish Primary School in Szeged in 1908 and 1909 (Löw Citation1908, 4–6, Löw Citation1909). Based on these lists, we know that the garden once had 76 different species. The most notable species were the cedars planted around the small hills and the black locust’s native on the Hungarian plain (Löw Citation1929, 324).

An undated, colored photocopy with the title “Tree-planting map of the synagogue site and the school” has survived. The drawing may have been made as an afforestation plan of the schoolyard, and according to art historian Ferenc Dávid, it recorded the conditions around 1908 (Dávid Citation2021, 58). In 1944, the synagogue garden was eradicated and destroyed when deportees were moved from the former ghetto to the synagogue, and their apartments were taken away. As their furniture was not taken away, these were all packed together in temporary synagogues in the garden of the synagogue next to the fence. In the garden of Immánuel Löw, a stall was set up during the time of the ghetto, leaving nothing of the plants of that time (Pacsika Citation2019). The synagogue was mostly untouched during WWII. In 1946 and around 1960, the city council had new trees planted to the park, and until the reconstruction, these aged trees were in the synagogue garden, preventing a view of the building.

The reconstruction of the garden was carried out between 2015 and 2018, and it aimed to recall the original state by replanting thirty-five species. Out of the 76 plant species, 35 could be replanted. Apart from the differences, however, efforts were made to maintain the vegetation’s density and diversity (Pacsika Citation2018).

Conclusion

The renowned Jewish community of Szeged stands as the largest Jewish community in southern Hungary and one of the most important in central Europe. Its Jewish community was founded in 1785, and at its peak, in the 1920s, it had 7000 members as the third biggest one in Hungary. The Szeged Jewish community is unique because Szeged was a primary focal point of Neolog Judaism and thus a prime locus (outside of Budapest) of the attempts of Jews living in Hungary to acculturate into the mainstream, Hungarian-speaking urban culture after the creation of Austria-Hungary in 1867. It is one of the few countryside communities in Hungary where, after the Holocaust, Jewish religious and communal life continued and is still taking place.

Built between 1900–1903, the magnificent Szeged New Synagogue, the fourth largest synagogue in Europe, is a masterpiece of architecture in a Historicising and Art Nouveau style, designed by architect Lipót Baumhorn in cooperation with Dr. Immánuel Löw, a botanist and the chief rabbi of Szeged. Without a doubt, Baumhorn’s crowning achievement was the Neolog Synagogue in Szeged, which, in addition to its complex form and large size, was distinguished by the symbolic depiction of the Jewish religion. The architect and the rabbi worked in close cooperation on the design process of the synagogue. The synagogue stands alone on the global stage, owing to its extraordinary botanical decoration system that is both distinctively designed and rich in symbolic meaning, drawing inspiration from motifs found in the Hebrew Bible, all due to the remarkable botanical expertise of the rabbi. It represents a unique and materialized fusion of Neolog Jewish ideals, Hungarian heritage, and architectural excellence. The synagogue garden, also designed by Löw, is unparalleled, being an organic part of the building, presenting the flora of Israel and Hungary. Preserving the New Synagogue is essential not only for architectural significance but also to honor the memory and legacy of the Jewish community that shaped Szeged’s development. It is a testament to a significant era in the city’s history, bridging Neolog Jewish ideals and Hungarian identity.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ágnes ivett Oszkó

Ágnes Ivett Oszkó, PhD is an art historian, researcher of the Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Center in Budapest, Hungary. Since 2020 she has been working as the curator of exhibitions on the works of synagogue architect Lipót Baumhorn and Hungarian synagogue architecture. [email protected]

Dóra Pataricza

Dóra Pataricza, PhD is working as a post-doctoral researcher at Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland, in a project titled “Antisemitism Undermining Democracy.” Since 2020, she has been working as the project director and the co-curator in a series of exhibitions on the works of synagogue architect Lipót Baumhorn. [email protected]

Notes

1 All the translations of Hebrew texts are taken from Sefaria.org.

References

- Ábrahám, Vera. 2016. Szeged zsidó temetői [The Jewish Cemeteries of Szeged].Szeged.

- Apró, Ferenc. 2011. A Hágitól a Mars Térig. Városismertető Séta [From the Hágit to the Mars Square. A City Tour]Szeged: Municipality of Szeged.

- Bányai, Viktória. 2017. A Szegedi Zsidó Hitközség tulajdonában lévő textiltárgyak: Feliratok, adományozók [Textiles Owned by the Szeged Jewish Community: Inscriptions, Donors].” In Szegedi Judaisztikai Közlemények 3.Szeged.

- Bányai, Viktória, ÉvaKatkó-Bagi, and DóraPataricza. 2023. “A Szegedi Zsidó Hitközség zsinagógai textiltárgyainak katalógusa” [Catalogue of the Synagogue Textiles of the Jewish Community of Szeged].” In Móra Ferenc Múzeum Évkönyve.Szeged.

- Biró, Tamás 2018. “A neológ és a református szakrális tér átalakulása a 19. században: Egy strukturális-összehasonlító vallástörténeti ujjgyakorlat”. [The Transformation of Neolog and Calvinist Sacral Space in the 19th Century: A Structural-Comparative Religious History Study].” In Schöner Alfréd hetven éves – Essays in Honor of Alfred Schöner, edited by Oláh, János and Zima, András. Budapest: Gabbiano Print Kft.

- Dávid, Ferenc. 2021. “Löw Immánuel szegedi zsinagógakertjének rekonstrukciója” [The Reconstrucion of the Synagogue Garden of Immánuel Löw in Szeged]Ars Hungarica47 (1): 47–74.

- Egyenlőség. 1903. [Equality] May 24, 17.

- Frauhammer, Krisztina, and AnnaSzentgyörgyi eds. 2020. Windows of Celebration in the New Synagogue of Szeged. Szeged: Municipality of Szeged.

- Gruber, Ruth Ellen. 1994. “Synagogues Seeking Heaven. Looking for Lipót Baumhorn.” In Upon the Doorposts of Thy House: Jewish Life in East-Central Europe, Yesterday and Today, edited by Ruth EllenGruber. New York: Wiley.

- Hajdók, Judit. 2021. A szabadkai zsinagóga újjáépített orgonája. [The Reconstructed Organ of the Synagogue in Szabadka]Szabadka: Szabadkai Zsinagóga Alapítvány.

- Hamar, Edina. 2014. “A Szegedi Zsidó Hitközség tulajdonában lévő kegytárgyak és liturgiai tárgyak állapotfelmérése restaurálás céljából.” [Survey of Relics and Liturgical Objects Owned by the Jewish Community of Szeged for Restoration Purposes].” In Zsidók Szeged társadalmában [Jews in Szeged’s Society], edited by IstvánTóth. Szeged: Múzeumi Tudományért Alapítvány Szeged.

- Hidvégi, Máté. 2019. “Löw Immánuel élete” [The Life of Immánuel Löw].” In Löw Immánuel válogatott művei. Virág és vallás [Selected Works of Immánuel Löw, Flower and Religion], edited by Hidvégi, Máté and TamásUngvári. Budapest: Scholar.

- Karády, Viktor. 1990. “Az asszimiláció Szegeden (Szociológiai kérdésvázlat).”)” [The Assimilation in Szeged. (A Sociologial Sketch)] in A szegedi zsidó polgárság emlékezete [The Memory of the Jewish Citizens of Szeged], edited by IstvánZombori. Szeged: Móra Ferenc Múzeum.

- Kármán György hetven éves. 2003. [György Kármán turned 70]. https://www.or-zse.hu/ev/karman70.htm

- Klein, Rudolf. 2017. Synagogues in Hungary 1782-1918. Genealogy, Typology and Architectural Significance. Budapest: Terc Kft.

- Löw, Immánuel. 1903. A szegedi új zsinagóga [The New Synagogue of Szeged]Szeged.

- Löw, Immánuel. 1908. A szegedi zsidó népiskola értesítője 1907–1908 [The Bulletin of the Szeged Jewish Elementary School 1907–1908]. Szeged.

- Löw, Immánuel. 1909. A szegedi zsidó népiskola értesítője 1908–1909 [The Bulletin of the Szeged Jewish Elementary School 1908–1909]. Szeged.

- Löw, Immánuel. 1923. Fölszentelő” [Inauguration Speech] in Száz Beszéd, 1900–1922 [Hundred Speeches, 1900–1922], edited by ImmánuelLöw. Szeged: Schwarcz.

- Löw, Immánuel. 1929. Hetven beszéd (1914–1928). [Seventy speeches. 1914–1928]. Szeged: Szegedi Zsidó Hitközség.

- Löw, Immánuel, and ZsigmondKulinyi. 1885. A szegedi zsidók 1785-től 1885-ig [The Jews of Szeged, 1785–1885]. Szeged: Szegedi Zsidó Hitközség.

- Oszkó, Ágnes Ivett. 2020. Baumhorn Lipót (1860–1932). Budapest: Holnap Kiadó.

- Oszkó, Ágnes, and DóraPataricza. Forthcoming. “Vadrózsa, bogáncs és cédrusok: A Szegedi Új Zsinagóga dekorációja” [Holy Brambles, Thistles, and Cedars. The Decoration of the Szeged New Synagogue]. Múlt és Jövő.

- Pacsika, Emília. 2018. “Bádog csodák, üvegboltozat - szegedi Új zsinagóga” [Tin Wonders, Glass Vaults – The Szeged New Synagogue]. Építészfórum, https://epiteszforum.hu/badog-csodak-uvegboltozat-szegedi-uj-zsinagoga

- Pacsika, Emília. 2019. „Szeged értelmiségi város volt” [Szeged was the city of the Literati]. Szegedhttp://szegedfolyoirat.sk-szeged.hu/2019/04/26/pacsika-emilia-szeged-ertelmisegi-varos-volt/

- Pejin, Attila. 2008. Tornyos zsinagógák Magyarországon [Towered Synagogues in Hungary]. https://www.or-zse.hu/resp/pejin/pejin-tornyos-zsinagogak2008.htm

- Silber, Michael. 1987. “The Historical Experience of German Jewry and Its Impact on Haskalah and Reform in Hungary.” In Toward Modernity: The European Jewish Model, edited by JacobKatz. New Brunswick and Oxford: Transaction Books.

- Varga Papi, László. 2021. Törött ablakok, törött remények. [Broken Glasses, Broken Hopes].Szeged: Atlasz.