ABSTRACT

Arts-based research is a participatory research practice that is well established in the qualitative field. However, while arts-based research has been defined as the creation of art to generate, interpret or communicate research knowledge, there is exiguous literature on the creation of art to establish trustworthiness in qualitative inquiry. This pilot case study specifically addresses this gap in the exploration of arts-based research practices to determine credibility and dependability. The context of the research was the impact of a Digital Sabbath practice on early career teachers, as teachers within their first five years of teaching are among the most vulnerable in the teaching profession. A Digital Sabbath is the practice of unplugging from all technology for one day per week, with the aim of increasing social connectedness and mitigating stress and burnout by decreasing our overuse of technology. The integration of arts-based research within this case study resulted in more active participation of the early career teachers throughout the research process. Consequently, participants’ voices resonated more strongly in the research output, as the iterative and participatory nature of the arts-based design supported a longitudinal dialogue between researcher and participant.

Introduction

Arts-based research (ABR) is a participatory research practice that connects embodied, visual literacy to more traditional academic research practices in higher education (Burnard et al. Citation2018; Jagodzinski and Wallin Citation2013), through which any art form/s are used to generate, interpret or communicate research knowledge (Knowles and Cole Citation2008; Parsons and Boydell Citation2012). Yet how aspects of ABR can be integrated with other qualitative methods in education is still to be explored. In the past decade, there has been considerable work on ABR in education, but this work largely focuses on the implementation of ABR within the education context rather than an integration of ABR with other methods (Cahnmann-Taylor and Siegesmund Citation2018).

While ABR approaches vary depending on the artform being used and the research context, it often involves the researcher interacting with their participant through arts-related activities; where working with the participant informs the researcher’s understanding of the participant’s lived experiences and results in the researcher creating scholarly arts-based works (Wang et al. Citation2017). The final output often draws on both artefacts created with or by the participant, as well as the researcher’s insights from data collected directly from the participant (e.g. interviews or field notes) or other sources related to the experience being explored (Leavy Citation2017). Through this process ABR researchers are able ‘to elicit, process and share understandings and experiences that are not readily or fully accessed through more traditional fieldwork approaches’ (Greenwood Citation2012, 2). Finley (Citation2008) argues that it is essential for ABR researchers to work through the arts in both process and product, to expand knowledge about daily life and individual lived experiences, and to communicate research findings democratically to a broad audience. Finley’s (Citation2008) intended aims of ABR methods align well with the education context through developing an understanding of human lived experiences of learning and by sharing research as education.

While ABR has a strong practice focus, research in education has been influenced by both quantitative methods from psychology and has increasingly adopted qualitative methods from the broader social sciences since the 1980s (Erickson Citation2011; Hsu Citation2005). Consequently, the methods used to collect and analyse data in education are extensive. The aim of this study was to explore how ABR methods could be integrated into an interview-based study in order to determine credibility and enhance research translation. This paper specifically describes one case from the overarching study in order to illustrate how participant engagement can be enhanced through the ABR method.

Issues with credibility in qualitative research and ABR

With developments in qualitative research, including the introduction of methods like ABR, there has been debate about the validity of ‘accepted’ quality criteria (Hammersley Citation2007; Leavy Citation2008). Hammersley (Citation2007) suggests that specific criteria are challenging to apply within the nature of qualitative work and instead the onus needs to be on researcher judgement:

… qualitative researchers need to give much more attention than is currently done to thinking about the considerations that must be taken into account in assessing the likely validity of knowledge claims, exploring the consistency of these with one another, and considering how they apply in other situations from those in which they were generated. (291–292)

Credibility has been defined as the internal validity of one’s research, or the establishment that the researcher’s interpretation matches their participants or the ‘factual accuracy of the account’ (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011, 181). Member checking is one common form of establishing credibility, and involves the researcher taking their ideas back to participants for confirmation of their accuracy (Harvey Citation2015). Yet Doyle (Citation2007) states that there are few in depth descriptions of how sufficient member checking is undertaken, with the main two forms of member checking reported as: (1) sending transcripts back to participants for confirmation, and (2) conducting a member check group session where participants are shown the initial findings of the study and asked provide feedback on the researcher’s interpretation. Sending transcripts back to participants lacks rigour as they can only comment on the nature of the transcription and not the trustworthiness of the researcher’s interpretation (Birt et al. Citation2016). Conducting group member check sessions are also problematic as disconfirming voices can be silenced by the group (Birt et al. Citation2016). These issues have led to researchers employing member checking interviews with individual participants (Doyle Citation2007; Harvey Citation2015). Yet this approach still has limitations; for example, the participant may feel coerced to agree with the researcher’s interpretations when in their presence due to social desirability bias, where a participant may act more positively to align their narrative to the perceived norm (Bergen and Labonté Citation2020). There may also be logistical challenges and additional consent required due to the length of time elapsed between the original data collection and the member checking interview (Birt et al. Citation2016). In addition to these approaches Birt et al. (Citation2016) suggest member checks of synthesized analysed data, whereby participants are presented with accessible summaries of the themes for the overall data set and identify their experience within the themes or add to the overall analysis with additional information. Yet this approach also relies on the participant understanding and feeling comfortable to comment on the analysis that is presented to them.

Throughout these member, checking approaches there is a desire to seek objective responses about data in order to confirm or disconfirm their validity, but there are also opportunities for participants to generate new data based on their reflections on the research (Birt et al. Citation2016; Harvey Citation2015). These opportunities can be empowering for participants as they can actively shape how they are represented in research (Brear Citation2019). Brear’s (Citation2019) approach to member checking included conducting workshops that involved both individual and group activities over time. This approach situated her as the learner with the participants actively engaging in reflecting on and enhancing her interpretation of their data, an approach she stated was transformative for participants (Brear Citation2019). Yet Varpio et al. (Citation2017) have cautioned that participants and researchers often view data from different lenses, where participants have a personal viewpoint and researchers can be more methodologically or theoretically driven; the two (sometimes) competing views need to be considered in negotiating the member checking process.

While ABR has grown out of qualitative inquiry, some researchers consider it to be a standalone paradigm (Leavy Citation2017). Consequently, researchers have also re-examined the quality measures used to assess ABR studies. Chilton and Leavy (Citation2014) suggest the following criteria are more appropriate for ABR:

Question/method fit: a sound justification of the need for ABR methods to meet the intended aims of the research,

Aesthetic power: the quality of the artistic output to communicate meaning,

Usefulness: the contribution of the output in terms of its educative power, contribution to the artform and/or drawing attention to an issue of importance,

Participatory/transformative: the active involvement of silenced voices in the artistic output,

Authenticity: a transparent and reflexive praxis by the researcher, and

Canonical generativity: the resonance of the artistic outputs with a broader audience than the original sample.

These criteria are similar to those put forward by Lafrenière and Cox (Citation2013) who group quality criteria under three broad headings: (1) normative criteria that relate to method and ethics in general, (2) substantive criteria that relate to the aesthetics and technical aspects of the artform, and (3) performative criteria that relate to the effect of the final artistic output on an audience. While these terms are unique to ABR, they are useful in their nuanced definitions of what constitutes credible research in arts research. In the context of this study, the focus of our discussion is on qualitative credibility more generally, using some of these specific ABR terms to unpack the role of ABR methods within the broader qualitative study being conducted.

Focusing on knowledge translation

The quality of research is always a consideration when reporting or translating research findings to the public. The translation of research findings is not a new concept; there has been much debate about the ‘research-practice’ gap in educational research and the strategies for translation to ensure that practitioners can make sense of and utilize findings (Hirschkorn and Geelan Citation2008; Broekkamp and van Hout-Wolters Citation2007). One of the strengths of ABR, as highlighted in its quality criteria, is the emphasis on translating knowledge for a broader audience (Lafrenière and Cox Citation2013; Finley Citation2008). Chilton and Leavy (Citation2014) assert that one of the strengths of the arts is their ability to disseminate knowledge to broad audiences. The arts can translate research findings about the experience as they encourage the audience to have an emboided experience that generates an effect (Lafrenière and Cox Citation2013). For visual arts, an installation can evoke a range of sensory responses in an audience (Lapum Citation2017). This type of audience response is especially important when the research topic is complex, experiential and not easily expressed in words (Gerber and Myers-Coffman Citation2017).

Knowledge translation through the arts is also transformative when they draw on multiple representations and symbols that are understood by a broad audience (Gerber and Myers-Coffman Citation2017). As opposed to traditional text-based publication, translation through the arts affords oppourtunities for dialogue between researcher and audience (Gerber and Myers-Coffman Citation2017; Lapum Citation2017; Barone and Eisner Citation1997). It is important to note that this dialogue can occur over time, as audiences engage with various stages of ABR (Gerber and Myers-Coffman Citation2017).

Research context

This study was motivated by a desire to support early-career teachers’ wellbeing. Market research has identified that technology use is rising, with 47% of respondents in a survey of 3500 individuals across all continents spending more than five hours per day on their mobile phones alone (Lu Citation2017). Increased use of technology can be positive, with evidence that it can enhance communication for both pre-service and in-service teachers, such as through online learning communities, professional learning or access to critical information (Selwyn, Nemorin, and Johnson Citation2017; Paris, Boston, and Morris Citation2015). However, teacher workload has also intensified at the same time as digital technology has increased in schools, with some teachers saying that having access to work on mobile devices extends the work day and that technology provides mechanisms to make teachers more accountable for their work (Selwyn, Nemorin, and Johnson Citation2017). In addition to these challenges for teachers, the increased use of technology has been reported to amplify stress, isolation and burnout (Burbles Citation2016; Ugur and Koc Citation2015), all issues that are associated with teacher wellbeing (Liu, Song, and Miao Citation2018).

Stress and burnout are two issues that are already well-documented within the education literature as a consequence of entering the teaching profession (Buchanan et al. Citation2013; Hong Citation2010). The notion of a Digital Sabbath practice has emerged from these concerns, not only for teachers but for all professionals. In a Digital Sabbath, individuals unplug from all technology for 24 h each week with the aim of increasing social connectedness and to mitigate their increasing use of technology. This research explored the feasibility and impact of a Digital Sabbath practice for seven early career visual arts teachers, as teachers within their first five years of teaching are among the most vulnerable in the teaching profession. Visual arts teachers were sampled for this specific study as their discipline specialism results in routine engagement in online spaces, as they report using multimodal sources for planning and reporting teaching experiences (for example, Pinterest and Instagram). Yet, it should be noted that the study did not focus on how teachers were using technology for school. Instead, the study and this paper focus on the teachers’ wellbeing more broadly as their use of technology was both professional and personal.

Method

The study followed the seven early career teachers as they unplugged for a day a week over a three-month period. While the study was qualitative in design, as the participants completed a descriptive survey about their technology and social media habits at the commencement of the project and then engaged in fortnightly interviews about the Digital Sabbath practice during the intervention period, it was also strongly situated in arts-based research. This integration occurred due to the researchers choosing to employ arts-based methods to document the qualitative data during the project (alongside field notes, transcripts and thematic coding of data) to establish credibility and as a knowledge translation strategy for the research findings. While, to some, this study may appear ABR in its design it does not meet the criteria for an arts-based research framework. For example, the aims of the study did not necessitate the use of the arts; it would have been possible to conduct the study as a traditional qualitative design and produce outputs in written text to communicate findings. However, the researchers decided to employ the arts within the qualitative design as both researchers and participants were visually literate (all being visual arts teachers) and due to the synergy between the phenomenon under investigation (Digital Sabbath from multimodal sources of technology). It also supported the researchers’ desire to communicate research findings in a multimodal form, with the final artworks from this process being publicly exhibited at a local government-funded gallery so the results could be disseminated broadly to the wider community.

After receiving approval from the Human Research Ethics Committees at both participating universities (Project 19259, approval date 25 October 2017), each researcher in the study recruited early career teachers to follow throughout the intervention period, with the first author following three teachers and the second following four. Recruitment was conducted via email to professional contacts of the researchers based on participation in previous programmes run by the researchers (including a joint artist in residence teaching programme). All of the visual arts teachers were female, with ages ranging from early twenties to early fifties. As early career teachers, some had permanency in their school and others were on short contracts across multiple schools.

As arts practice is highly personalized, each researcher authentically engaged the arts during the project to meet their participants’ needs. This paper focuses on the process of the first author, where the arts were engaged within member checking and to ensure credible knowledge translation of each participants’ experience.

For the first author, the initial survey and interview focused on rapport building and establishing a picture of the status quo in terms of each participants’ engagement with technology. The interview was transcribed and inductively coded, and the survey responses were descriptively analysed to triangulate the interview findings. From these data, the researcher generated a concept sketch for an artwork that summarized the findings. This sketch was shown to the participant at the beginning of the second interview for critique. It was refined based on the participant’s feedback and then produced as an artwork. This process continued for the duration of the three months; however, not every interview resulted in a separate artwork. When the interviews covered similar themes, these ideas were integrated into existing sketches. On average, four artworks were produced per participant over the three-month period.

The process of generating art and then taking it back to participants is not entirely novel. Gerstenblatt (Citation2013) produced portraits that were then taken to participants for member checking to ensure they appropriately represented her research findings. However, this process occurred at the completion of the artworks (Gerstenblatt Citation2013). In this study, art making was used as part of a dialogic member checking process where the participant was empowered to change or redesign the work throughout production.

Results

While the first author’s method was consistently applied across all three teachers, the research topic resulted in highly personalized journeys for each participant. In order to clearly unpack the method in this paper, a single case study was selected from the three teachers followed by the first author. This teacher, participant G, was a mature-aged teaching graduate in her early fifties. She had completed some artist in residency work in schools but, as a first-year graduate, was still looking for fixed employment. The initial background survey that explored technology platforms used, activities on devices (i.e. professional or personal use), frequency of use, security preferences and comfort having/not having technology indicted that participant G was a confident user of technology who felt physical discomfort when disconnected from her devices. She primarily used her devices for personal activities, but also used them to search for inspiration for creative activities and to maintain a professional profile (e.g. LinkedIn use).

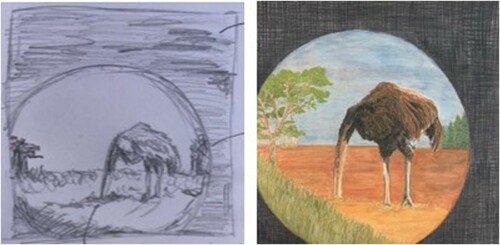

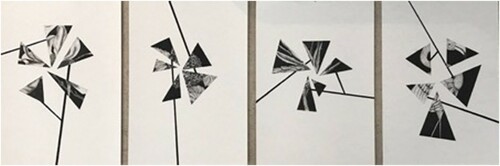

The first artwork in the series () was devised from the initial survey and interview with participant G. While the survey described online habits, the interview also unpacked the participant’s reasons for wanting to engage in the project as well as gathering deeper insights into her technology and social media use. The first interview covered themes of addiction to technology and online voyeurism, with participant G saying

My main reason [for participating] – addiction appears to be forming with regards to social media. First thing in the morning, first thing I do is sit up in bed, grab my iPad, switch it on and spend about an hour looking at posts, sometimes more. I’d like to be able to just leave it, to go somewhere, sit down have a coffee with somebody and just not take out the flipping phone … but the temptations, you can feel it, it’s like being drawn to this thing.

Before it was mainly interest and keeping in touch with certain friends. Now it’s almost voyeuristic. I’m in a couple of chat pages for the area and a couple of the areas round about and it is really interesting getting involved in what their lives are about and what they have got to complain about.

After listening and reading the data multiple times, the author devised the concept sketch shown in . At the second interview (a fortnight later) this sketch was shown to the participant and the researcher’s process of creating the sketch from the data was shared. This excerpt from interview two shows how the data were described in relation to the sketch

I’m thinking symbolically. I was listening to the interview again and I was thinking about how you say technology is all about the escapism but then it’s kind of also voyeurism, where you get locked into it. I have that whole analogy of the ostrich with its head buried down, that it’s this kind of consuming thing … but I was also thinking we were talking about how you connect now with your family [overseas] and friends … that there’s no separation in time and distance. So I’m feeling like in this background landscape I’d like to integrate some Australian landscape and some of your [birthplace] landscapes. You will be the best person to tell me the kind of things I should put there.

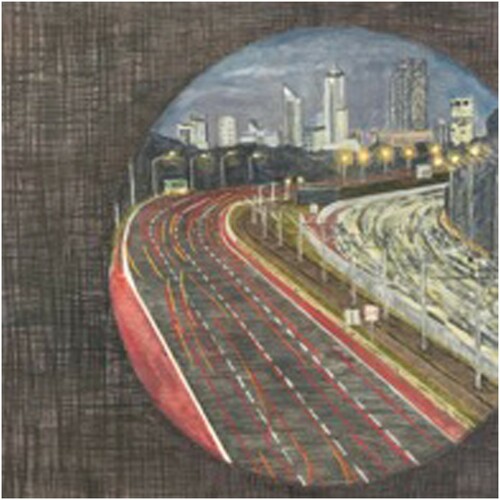

The second artwork was refined over a few interviews with the participant, in the first half of her Digital Sabbath experience. The second artwork was communication and concentration, based on the following types of discussion about family with the participant

What is it with males wanting you to sit and watch TV, not doing something productive … they just want to sit … it’s this company thing … I’m still sitting here but I’m not watching TV, I’m doing my crocheting … it’s raised some interesting conversations in my family around that kind of time you spend together …

I do carry my phone with me. It’s the mum thing. I’ve gotta be able to be contactable by the kids or partner. They phone, say what they have to say and [they’re] gone … less than a minute … they hate talking to other people on the phone. My partner will talk to business people for hours on the phone, me [I get] one line …

The Digital Sabbath process was making the participant more aware about the types of communication among her family. She also spoke often about trying to get concentrated on tasks for longer periods of time as her technology patterns suggested she also had small moments of communication that were disjointed through social media or other platforms. Consequently, the second work proposed by the researcher wanted to follow the concept of communication as a two-way street:

I went for the big things I think have been coming out of what you have been writing and what you have been talking about … I have very roughly drawn up the second work, a busy freeway of some description. That kind of image resonated with me when you were talking about trying not to get distracted and trying to listen more and concentrate more … that kind of two-way communication thing happening in that image, getting in the flow. Also I want to acknowledge a sense of movement, this is a journey and there are priorities you are taking on it.

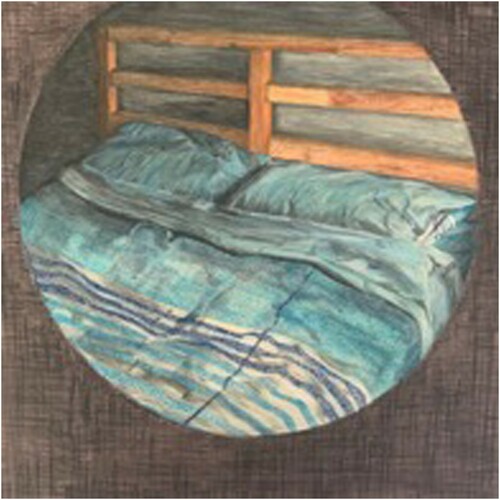

, the third work in the series, was developed from the middle month of the intervention. At this point the participant had overcome some of the challenges with stepping away from technology and started to discuss some of the benefits she had noticed:

I have kind of used this Digital Sabbath as way to have a decent rest … which has been good … for the first time in years I’m starting to sleep through the night … not entirely sure why but it’s really good. Don’t know whether it’s got something to do with this … it seems to have got my stress hormones down as well.

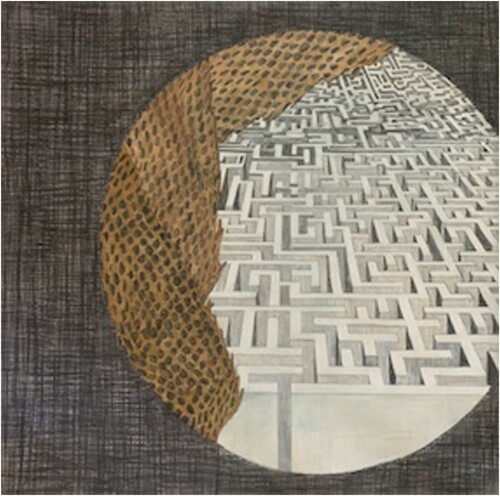

The final artwork () was devised during the final few interviews with the participant. It followed a slightly different approach than the previous works. At the penultimate interview participant G gave the researcher a piece of packaging she had collected. It was from some essential oils she had been using throughout the Digital Sabbath intervention and she thought the packaging itself was an interesting texture so she kept it. Consequently, the researcher knew that this would be worked into the final work she was creating.

The last two interviews, and final one in particular, focused on the participant’s reflection on her overall Digital Sabbath experience. Themes arising from the inductive coding included strategies to avoid picking up technology during the Digital Sabbath, and creating new habits:

Not picking up the iPad [is an ongoing challenge]. I charge it at night, it’s right there beside my bed … [I’m] leaving in it in the bedroom, shoving it under my pillow or something so every time I go through there I’m not seeing it … there is only one person I’d be cheating and that’s me. [My phone] goes beside the TV cabinet, not beside me. So I’ve then got to get up and go get it and if I’m sitting down. I’m trying not to go on to social media until at least lunchtime most days … [it] was fine today because we were out and I took my book with me.

I have that packaging at home and I want to do something with that in the foreground because it is a beautiful shape and [it is] part of [your] collection [from the Digital Sabbath]. I feel like the background should be a maze … it has that implication of journey, moving, stopping, collecting, going onto the next thing. I was listening back to our conversation about you trying to leave your phone near the TV or away from you so you didn’t have to get up and get it. And I thought you’ve created challenges for yourself, you have to physically negotiate a maze to get to your phone.

Of importance to the research process described above was the purposeful distancing the researcher employed to minimize ownership of the artistic process. One pitfall of member checking through an interview is that the participant may feel coerced to agree with the researcher’s interpretation (Birt et al. Citation2016). displays an example of the researcher’s own artistic practice, which is distinct from the style used for this study, shown in participant G’s series.

Figure 5. An example of the researcher’s personal artistic style, Magnolia, Hydrangea, Strelitzia, Flamingo, 2018, charcoal and pencil on paper.

While the researcher often works with landscape as a subject, the stylistic decisions differ greatly between her own work and the works produced as part of the study. Prior to working with the participants the researcher decided that working in her own style might be less successful when employing arts based methods in member checking, as it suggests the researcher/artist has ownership over the artistic choices rather than the works being collaborative. The researcher showed examples of her work to participants at the beginning of the study so they could see how the style being employed in this study was a new way of working for the researcher. This approach built rapport between the participant and the researcher as both parties were learning through the process. It also resulted in the shared ownership over the artworks produced, with the participant driving the concepts included and the researcher’s hand being open in the production of authentic imagery based on the participant’s data. The member checking interviews where concept sketches were shared did not arouse any conflict between the participant and researcher; instead constructive discussions ensued to make changes to the composition or presentation of the sketch, or deeper elaboration on the concept was given by the participant. While only one sketch was presented at each member checking interview, the researcher always stated that the idea was not finalized and indicated uncertainty about the concept if she wanted to seek further clarification from participants about her interpretation.

Discussion

The case study of participant G outlines the art-based approach taken by the researcher to engage in member checking. The first aim of this approach was to explore how ABR methods could be integrated into a more traditional qualitative design in order to determine credibility. The active participation of the early career teacher throughout the data collection process is evident in this case. The participant was able to have an ongoing discussion about the works and be an active collaborator in shaping the presentation of research findings throughout the project. While early discussions often focused on the presentation of the work and general agreement or disagreement with the researcher’s interpretation, the member checking interviews for the final two works showed a deeper engagement with research findings and the participant added anecdotes and further details that resulted in clarification of the main themes being presented (for example, the decision to have a non-representational maze in the final work). It was evident that the participant’s engagement with the research process and interpretation of her data was deepening over time as a result of frequent opportunities for reflection. In addition, the participant often looked at the concept sketch and gave examples of how her experiences matched the symbols or concepts presented in visual form; this type of engagement with the process was similar to the synthesized analysed data member checking approach (Birt et al. Citation2016), where participants situated their own experiences within a summary of themes from the overall data set. This approach mitigates risks concerned with participants feeling confronted by receiving their verbatim transcripts (Birt et al. Citation2016).

While the researcher gained confidence in the dialogic member checking approach based on the participant’s engagement with the data over time, there was also evidence that this approach met some of the quality criteria for ABR as defined by Chilton and Leavy (Citation2014). First, the aesthetic power of the works was addressed through discussion about the participant’s reading of the work and its ability to communicate a valid interpretation of her data; second, as illustrative above the approach was highly participatory and there were multiple opportunities for the participant to be active in the artistic output; and third, the process of creating a sketch and then actively discussing it with participant resulted in an authentic and reflexive praxis by the researcher. This approach made the researcher more connected to the member checking process as there was active collaboration. In other member checking approaches the researcher simply presents their interpretation and then gathers feedback from participants (Birt et al. Citation2016), yet in this study, the longitudinal and dialogic nature of the member checking approach necessitated a participatory (but not coercive) role.

The second aim of the study was to produce works that would translate research findings for a broader audience. While data were not collected on the final public installation of the works, the feedback from participants in the member checking approach has provided some evidence of the educative power of the works. The collaboration with the participant afforded the opportunity to ensure the works were authentic to their individual experience, and broader symbols were used to translate these concepts to enhance translation. The result of this process was the multimodal dissemination of research findings, which occurred through exhibition as well as through more traditional academic publication. One strength of using the arts is the sensory response it can evoke from an audience (Lapum Citation2017), which is useful when the research topic is not easily expressed in words (Gerber and Myers-Coffman Citation2017). This approach is applicable to the study of wellbeing, which is a complex phenomenon (Liu, Song, and Miao Citation2018). Consequently, evoking a sensory response was essential to enaging the audience and calling attention to our relationship with technology, both for teachers and the broader public. It is anticipated that this approach to dissmenating findings can support the research-practice gap, as teachers (and others) have greater access to the publicly available artworks than they do traditional academic outputs. The democratic access to research findings is essential in knowledge translation back to practice, and paticularly in providing opportunities for teachers and others to reflect on their own engagement with technology.

While this study shows some distinct benefits to engaging longitudinal, ABR approaches to member checking there are some challenges that need to be considered and addressed by researchers. First, it is can be challenging for a participant to make sense of a researcher’s interpretation of their data and this approach requires a participant not only to comment on the interpretation of data but also its representation in a visual form. These dual layers to member checking may have an effect on the conversations between participant and researcher and require careful planning and consideration on the researcher’s part. In this study, the issue of interpretation was addressed in two ways: (1) through sampling, where both researcher and participant were art teachers who were confident in visual language and in analysing visual works; and (2) through the longitudinal design, where there were multiple opportunities to engage in the process so that it could be refined over time. The researcher ensured to ask probing questions about the sketches so to elicit conversation about both the interpretation of data and then the presentation of those data in visual form.

Second, there are some issues around ethics that need to be addressed in this type of research design. In this approach there is clear collaboration between the researcher and the participant in the co-creation of the final artworks. In a traditional ABR framework it is common for the artist to produce works that are inspired by the participant, but in this study, the participant (through the member checking interviews) shaped the creation of the artwork in addition to providing the inspiration for it. In this study, the participant is active in data analysis and generation alongside the researcher but under the National Statement for Ethical Conduct in Human Research the participant is also entitled to remain anonymous in research reporting (National Health and Medical Research Council Citation2007). In this study, the issue was addressed through discussion with the participants, who could choose to be made identifiable in the presentation of the final works if they wished. Yet this is an area that requires further exploration in co-created ABR and research studies that include co-created or designed non-traditional research outputs.

While the researchers in this study were the primary artists, it would also be interesting to explore the potential for participants to individually generate artworks that are then the starting point for interviews about the research topic. This approach may further empower participants in the research, but was beyond the scope of this study. Creating artworks can take considerable time and the researchers did not wish to place additional burden onto an already vulnerable population, given the burnout and stress issues previously identified within the early career teacher population. However, in collaboration with participants, it might be possible to address issues of co-creation through more co-participatory or participant-led artwork production.

Future research in this area could also examine the efficacy of this method beyond visual arts teachers. While visual literacy was deemed important for deep discussions about the artwork to occur, our multimodal society means all individuals have a degree of visual literacy from daily interactions with technology platforms. The extent to which this method can be replicated with individuals who are ‘outside’ the arts is yet to be examined, as is the potential for other artforms (or other products) to be employed within this type of research method.

Conclusion

This study contributes to method through the integration of ABR to interpret data and perform member checking within more traditional qualitative education research. The approach piloted in this study supported deep engagement from the participants in the member checking process, with the illustrative case study presented giving one example of the types of conversations that occurred to both create the artworks and confirm the credibility of the data presented by teachers in the study. In a multimodal and multi-literacy society, this approach to member checking gave participants a unique way of returning to the data and the researcher’s interpretation of those data. In this study, the approach was not confronting and discussions around both data interpretation and aesthetic presentation were present in most member checking interviews.

The second aim of this study was to integrate ABR as a knowledge translation strategy for the interview data collected. While this paper has focused on how the method supports the development of credible data for presentation in an exhibition, the evaluation of this method to enhance education knowledge translation to a broader public context is yet to be conducted. Nevertheless, ABR has a history of engaging audiences in challenging and authentic experiences (Lapum Citation2017), which is one of its strengths as a methodology. It is anticipated that this strategy, in combination with traditional academic publications, will strengthen the connection between research and practice.

The approach used in this study is just one example of innovating and integrating methodologies to best meet both the needs of the participants and research aims of the study. While further refinement is needed, participants’ voices appeared to resonate more strongly in the research output as a result of the iterative and participatory nature of the ABR design conducted over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barone, T., and E. Eisner. 1997. “Arts Based Educational Research.” In Complementary Methods for Reserach in Education, edited by R. M. Jaeger, 95–109. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

- Bergen, N., and R. Labonté. 2020. “Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Health Research 30 (5): 783–792. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319889354.

- Birt, L., S. Scott, D. Cavers, C. Campbell, and F. Walter. 2016. “Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870.

- Brear, M. 2019. “Process and Outcomes of a Recursive, Dialogic Member Checking Approach: A Project Ethnography.” Qualitative Health Research 29 (7): 944–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318812448.

- Broekkamp, H., and B. van Hout-Wolters. 2007. “The gap Between Educational Research and Practice: A Literature Review, Symposium, and Questionnaire.” Educational Research and Evaluation 13 (3): 203–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610701626127.

- Buchanan, J., A. Prescott, S. Schuck, P. Arbusson, P. Burke, and J. Louviere. 2013. “Teacher Retention and Attrition: Views of Early Career Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 38 (3): 112–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n3.9.

- Burbles, N. C. 2016. “How we use and are Used by Social Media in Education.” Educational Theory 66 (4): 551–565.

- Burnard, P., C. Holliday, S. Jasilek, and A. Nikolova. 2018. “Artists and Arts-Based Method use in Higher Education: A Living Inquiry of an Academic Programme in a Faculty of Education.” In Arts-based Methods and Organizational Learning, edited by T. Chemi and X. Du, 291–325. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cahnmann-Taylor, M., and R. Siegesmund. 2018. Arts-based Research in Education: Foundations for Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chilton, G., and P. Leavy. 2014. “Arts-based Research Practice: Merging Social Research and the Creative Arts.” In Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by P. Leavy, 403–422. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. 7th ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2000. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Doyle, S. 2007. “Member Checking With Older Women: A Framework for Negotiating Meaning.” Health Care for Women International 28 (10): 888–908. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330701615325.

- Erickson, F. 2011. “A History of Qualitative Inquiry in Social and Educational Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 43–60. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Finley, S. 2008. “Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples and Issues, edited by J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole, 72–82. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Gerber, N., and K. Myers-Coffman. 2017. “Translation in Arts-Based Research.” In Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by P. Leavy, 587–607. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Gerstenblatt, P. 2013. “Collage Portraits as a Method of Analysis in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12 (1): 294–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200114.

- Greenwood, J. 2012. “Arts-based Research: Weaving Magic and Meaning.” International Journal of Education and the Arts 13: 1–20.

- Hammersley, M. 2007. “The Issue of Quality in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 30 (3): 287–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270701614782.

- Harvey, L. 2015. “Beyond Member-Checking: A Dialogic Approach to the Research Interview.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 38 (1): 23–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2014.914487.

- Hirschkorn, M., and D. Geelan. 2008. “Bridging the Research-Practice gap: Research Translation and/or Research Transformation.” The Alberta Journal of Educational Research 54 (1): 1–13.

- Hong, J. Y. 2010. “Pre-service and Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity and its Relation to Dropping out of the Profession.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1530–1543.

- Hsu, T. 2005. “Research Methods and Data Analysis Procedures Used by Educational Researchers.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 28 (2): 109–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01406720500256194.

- Jagodzinski, J., and J. Wallin. 2013. Arts-based Research: A Critique and a Proposal. Rotterdam: Sense Publishing.

- Knowles, J. G., and A. L. Cole. 2008. Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lafrenière, D., and S. M. Cox. 2013. “‘If you Can Call it a Poem’: Toward a Framework for the Assessment of Arts-Based Works.” Qualitative Research 13 (3): 318–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446104.

- Lapum, J. L. 2017. “Installation: The Voyage Never Ends.” In Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by P. Leavy, 377–395. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Leavy, P. 2008. “Chapter 1: Social Research and the Creative Arts, an Introduction.” In Methods Meets Art, edited by P. Leavy, 1–24. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Leavy, P. 2017. Handbook of Arts-Based Research. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Liu, L. B., H. Song, and P. Miao. 2018. “Navigating Individual and Collective Notions of Teacher Wellbeing as a Complex Phenomenon Shaped by National Context.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 48 (1): 128–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1283979.

- Lu, T. 2017. “Almost Half of Smartphone Users Spend More than 5 h a day on their Mobile Device.” https://www.counterpointresearch.com/almost-half-of-smartphone-users-spend-more-than-5-hours-a-day-on-their-mobile-device/.

- Merriam, S. B. 2009. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2007. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (Updated 2018). Canberra: AusInfo.

- Paris, L., J. Boston, and J. E. Morris. 2015. “Facebook and the Final Practicum: The Impact of Online Peer Support in the Assistant Teacher Program.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40 (9): 157–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte/2015v40n9.9.

- Parsons, J. A., and K. M. Boydell. 2012. “Arts-based Research and Knowledge Translation: Some key Concerns for Health-Care Professionals.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 26 (3): 170–172.

- Selwyn, N., S. Nemorin, and N. Johnson. 2017. “‘High-Tech, Hard Work: an Investigation of Teachers’ Work in the Digital age.” Learning, Media and Technology 42 (4): 390–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1252770.

- Ugur, N. G., and T. Koc. 2015. “Time for Digital Detox: Misuse of Mobile Technology and Phubbing.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 195: 1022–1031.

- Varpio, L., R. Ajjawi, L. V. Monrouxe, B. C. O'Brien, and C. E. Rees. 2017. “Shedding the Cobra Effect: Problematising Thematic Emergence, Triangulation, Saturation and Member Checking.” Medical Education 51 (1): 40–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13124.

- Wang, Q., S. Coemans, R. Siegesmund, and K. Hannes. 2017. “Arts-based Methods in Socially-Engaged Research Practice: A Classification Framework.” Art Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal 2 (2): 5–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.18432/R26G8P.