ABSTRACT

The current debates in the area of researchers’ positionalities criticize the notion of the ‘insider/outsider’ dichotomy and favour the idea of a fluid inbetweener position. However, these narratives foreground researchers’ perspectives and often ignore participants’ agency in constructing a researcher's positionality in the field. In this paper, as an early career researcher, I analyze my journey with my own positionalities in ethnographic research in a rural community in Bangladesh. Adopting a Critical Realist ontological standpoint, I argue that positionalities are co-constructed by researcher and participant and are products of complex interactions between their agencies and the social structure. I illustrate how reflexivity, taking both my and the participants’ views into account, facilitated my movement towards a position where the participants expose their habitual behaviour (not hesitating to offer their day-to-day food – mash potato) rather than providing superficial information (as they do to a guest, for whom they will at least fry an egg – a special arrangement – for dinner).

Introduction

Like other qualitative research methodologies, ethnography often encounters criticism as invalid and fuzzy (Hammersley Citation2006) and has long been theorized differently. One of the aspects of ethnographic research which has featured in debates is ‘positionality': it has been argued that reflecting on the researcher's identities is crucial to make ethnography more ‘valid’ (Kaidesoja Citation2009). Although the term ‘positionality’ has become a buzzword in recent times (Milligan Citation2016), the debate around the concept is longstanding, evolving from prior to the popularisations of the technique of prolonged fieldwork by Bronislaw Malinowski (Young Citation2017). In this article, I offer the experience of an Early Career Researcher (ECR) and illustrate how I navigated my positions, in a Bangladeshi Primary school, during my fieldwork for my doctoral study (Rahman Citation2020).

Three aspects of this article are significant. First, this is an ECR account. An ECR’s perspective is important because the way novice researchers make meaning of field experience shapes both their career and the knowledge they would produce in future. However, studies of ECRs’ experience of research are scarce (Sala-Bubaré et al. Citation2022). Additionally, it can be helpful for ECRs to hear about others’ experiences of ethnographic fieldwork for informed decisions.

The second aspect of significance is my researcher identity. I am a researcher born and had primary education in rural Bangladesh – a country in the Global South (GS). I also worked as an educational researcher in Bangladesh. Yet, part of my higher education and research training was in the UK. The tension between my nativeness and the acquired knowledge from non-native system (Smith Citation2021) and how this is crucial in constructing positionalities is interesting to analyze.

The third contribution is the significance of the Global South (GS) context. Despite differences, GS countries share common features such as colonial legacies; hence, the GS term is used in a relational, not literal manner. People in GS countries often experience multiple temporalities, which are products of ‘balanced’ tensions and negotiations between unfinished pasts and unstable presents (Raghuram et al. Citation2014). The intersection between my researcher's identity and the respondents’ postcolonial tensions results in a complex process of identity creation in the field.

I analyzed my positionalities and their effect on the data taking these three aspects into account because people’s identity lies at the intersection of different social aspects (Trahan Citation2011, Collins and Bilge Citation2020) and it is the combination of these constructs that often shapes people’s experiences.

I applied a Critical Realist (Bhaskar Citation2013) lens to do so. I considered the participants’ and my agency as well as the social structure of the research context to understand and reflect on positionalities. I illustrated how I gained access to the community where the participants expose their habitual behaviour (not hesitating to offer their day-to-day food mash potato) rather than providing superficial information (as they do to a guest, for whom they will at least fry an egg – a special arrangement – for dinner). Before discussing the complexity around the notion of researcher positionality and my experience, I believe it is important to provide a brief account of my PhD study.

Study background and methodology

This paper depicts my reflection on my ethnographic PhD fieldwork explored the nature of teachers’ collaboration (Rahman Citation2020) in a government primary school (state-run school) in Bangladesh – a south-Asian country. In my study, I answered the following research questions:

How is the concept of collaboration understood by teachers in a rural school in Bangladesh?

What is the nature of existing collaborative activities in the broader school context?

How do the factors related to teacher agency and social structure shape teachers’ understanding and practice of collaboration?

The study was conducted in one rural government primary school in Bangladesh. Rural primary schools in Bangladesh are often understaffed (UNESCO Citation2015), and it was not easy to identify a school that has sufficient teachers to perform day-to-day collaborative professional interactions. Hence, I visited three schools in a rural Upazila (state administrative unit) to identify an appropriate school where professional interaction is comparatively more evident. After spending two days in each of the three schools, one school was selected for the actual study. The Upazila and three schools were selected with the help of one of my ex-colleagues, a teacher trainer in Bangladesh. Teachers’ collaboration was more evident in the selected school than in the other two, and therefore the research site would yield data. Moreover, all the teachers at this school agreed to participate voluntarily in the study. Like typical government primary schools in Bangladesh, the school consists of seven classrooms and a staff room (where all the teachers and the headteacher sit), serving 593 students by twelve teachers, including the headteacher, during the fieldwork period. I conducted a single-site study for an in-depth understanding of the school community (teachers, students and other stakeholders, e.g. parents and school managing committee), the social structure of the school and the interplay between the two. Moreover, a multisite in-depth ethnography was beyond the capacity of a PhD researcher.

I carried out two months-long fieldwork when I attended the school each day from the beginning till the end of the school day. I observed teachers’ activities inside and outside the school, interviewed them formally and informally, and audio recorded their staffroom conversations. Consents were taken before audio recording their interviews and staffroom conversations. The activities were designed following BERA (Citation2018) guidelines and were approved by my university ethics board.

Literature review

Ethnography is often defined as the tool for a first hand study of what people do and says in particular contexts (Hammersley Citation2006, Atkinson Citation2007); the importance has been on accessing a natural research context with the least interruption. Endeavours have been evident among educational ethnographers to access and understand such uninterrupted situations since the 1960s, and participatory observation has been becoming a popular tool for such purposes (Delamont Citation1975, Walker and Adelman Citation1976, Wragg et al. Citation1978, Measor and Woods Citation1984, Woods Citation1986). The inherent complexity of social life in educational settings took the centre of debate in educational ethnography studies (Bossert et al. Citation1977), and ethnographers started to become critical of the relationship between observers and observants in educational settings. Adelman et al. (Citation1976) go on, ‘What you see in a school will depend on how the school sees you.’ (8). This debate is still in progress. Hammersley (Citation2006) pointed ‘our own behaviour affects what we are studying.’ (5). How we see and are seen as researchers in an ethnographic context is dependent on our perceived location within the community. These locations are often seen within insider and outsider poles (Sultana Citation2007, DiAngelo and Sensoy Citation2009, Berger Citation2015, Milligan Citation2016, Krauss Citation2018). Researchers’ positions and their effect on the knowledge gained are significant concerns in recent educational ethnography.

While some scholars defined positionality as a ‘placement’ resulting from the relationships between researcher and researched (Anthias Citation2002), which are featured with a complex web of cultural values, beliefs and experiences (DiAngelo and Sensoy Citation2009), others explained positions as the status of a researcher dependent on his/her personal characteristics including race, age, sexual orientation, organizational and cultural affiliations (Naples Citation1996, Bradbury-Jones Citation2007, Berger Citation2015, Bettez Citation2015). Most scholars foreground researchers’ characteristics and the context but ignore participants’ agencies when engaging in the debate around ‘positionality’. Such an approach has contributed to developing an ‘insider/outsider dichotomy where a researcher is considered either as a member of the researched community or a distant observer (Nakata Citation2015, Jimenez et al. Citation2021).

Insider researchers are those who share a history and cultural ways of being with the participants. They might be community members, or they place themselves closely into their research context and create a friendly relationship with the participants (Kanuha Citation2000, Adu-Ampong and Adams Citation2020). Outsider researchers are usually not members of the participants’ community. They observe the research context and the participants’ behaviour from a distance to avoid any interruption to the research context. Such definitions of insider and outsider positionalities separate the research participants from the researcher (Naples Citation1996, Jimenez et al. Citation2021) and constitute researchers as sole producers of knowledge and place them in a higher position than the participants. Yet, researchers and participants supplement each other through the research processes (Delph-Janiurek Citation2001), including constructing researchers’ positionalities. While a researcher's agency allows him/her to decide strategies to place themselves in the desired position to ensure the best observation (Adelman et al. Citation1976, Measor and Woods Citation1984, Berger Citation2015, Milligan Citation2016, Barnes Citation2021), participants can act as agents to control a researcher’s access and engagement in the community as an insider or outsider or anywhere between these two ends.

The ‘insider'/‘outsider’ fixed dichotomy is opposed by many scholars who propose a notion of ‘fluid identity that is developed differently in different situations (Hellawell Citation2006, Thomson and Gunter Citation2011, McGinity Citation2012, Milligan Citation2016, Barnes Citation2021). Researchers are often ‘inbetweeners’, where they experience multiple and shifting identities (Mullings Citation1999, Srivastava Citation2006).

However, Milligan (Citation2016) opposed the notion of ‘fluidity’ by viewing the researcher as an active agent in the field who actively negotiates her positions during data collection and continuously and consciously moves between the ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ status. Barnes (Citation2021) goes further by blending the notions of ‘fluid’ and ‘active’ in-betweenness and calling himself a ‘liquid inbetweener’ where he was more concerned with locating, defining and understanding his positionality than dictating it (Barnes Citation2021, p. 248). He used his agency to understand his positionalities and their effect on his understanding rather than placing himself in a specific position.

Nonetheless, the existing discussions in this area are concerned about the researchers’ perspectives and hence, I argue, reductionist. Most of the narratives in this area examine how a researcher determines his/her position. While researchers are active agents, I argue that participants’ agencies also contribute to the researchers’ positionalities. Among very few scholars, Milligan (Citation2016) acknowledged the contribution of her participants in shaping her positionality ‘much of my identity in this cross-cultural ethnographic research was given to me by the wider community, who saw me as the mzungu’ (p. 248). Yet, she did not explicitly discuss the participants’ role in developing and changing her positionalities. Rather, her discussion focused on the researcher’s active choices and how these affect the way the researcher was viewed.

Although I acknowledge Milligan's (Citation2016) proposition and consider myself as an active agent in developing my positionalities, I argue that the social structure – the internal relations between social positions e.g. researcher and participants (Kaidesoja Citation2009) – and participants’ actions and responses are no less responsible for determining positionalities (Arthur Citation2010). As I take a Critical Realist (CR) ontological standpoint, I argue that in my deliberation to secure a suitable position (researcher agency), the social norms and values and the participants agency need to be reflected to understand my positionalities and their effect on the data. The CR framework seeks to account for how agents use their personal powers for the desired outcome in any given social situation (Archer and Archer Citation2003). The power of an individual member of society may be commissioned by several social factors such as social capital (e.g. the network with other members) (Bourdieu Citation1990), cultural values (e.g. construction of gender), interpersonal skills and so on.

This paper argues that positionalities are co-constructed by researcher and participant through complex interactions between researchers’ and participants’ perceptions and agency. The concept of co-construction here refers to a linguistic and interactional process that mediates a newcomer's (researcher in this case) participation and identity formation in a new cultural context (Duff Citation2002).

In this paper, with empirical data I explained my own positionality and discuss.

how the interactions between the participants and my agency contributed to the co-construction of my positionalities

how different positionalities directed my accessibility in the field and influenced my data

how I used my agency to minimize the effect of my positionalities on the research environment

Conceptual frameworks

Two different conceptual frameworks are brought together in this paper. First, a researcher's positionality during qualitative fieldwork is understood as action and negotiation rather than a static status of the researcher (Cho and Yi Citation2019). A researcher continuously negotiates and shifts his/her identities in the field. The positionality is fluid and may range from a complete outsider to a native status and anywhere between these two poles.

Second, positionality is considered as a social event (i.e. the action and negotiation) which is looked at through a Critical Realist (Bhaskar Citation2013) lens. A Critical Realist (CR) approach suggests that any social phenomenon (e.g. positionality) needs to be analyzed, taking the agency-structure relationship into account (Scott Citation2005, Pawson Citation2013, Tikly Citation2015). It acknowledges the existence of a mind-independent, structured and changing reality. But the knowledge of reality is a social product, which is not independent of those who produce it (Bhaskar Citation2013). According to CR philosophy, social structure and human agency possess distinct power in their own right. The social structure includes the features (e.g. norms, culture) of the society, while human agency possesses attributes such as self-consciousness, reflexivity, intentionality and emotionality (Tikly Citation2015, Palaganas et al. Citation2017). While the powers of social structures enable or restrict human actions, human agency enables people to formulate, pursue interests and learn. For instance, the power of cultural values, such as social constructions of ‘gender’, may shape how people of different gender identities interact. At the same time, the agencies of an individual member of society may allow them to interact in their desired way despite the cultural norms.

In this study, the social norms and values of the research context, such as the social construction of gender, and the cultural characteristics of the society (e.g. social cohesion, sense of hierarchy etc.) are considered as elements of social structure in which both the participants and I used our agencies to act. The complex interactions between the social structure and our agencies (Archer and Archer Citation2003) shaped my identities and positionalities in the field.

The positionalities in my fieldwork

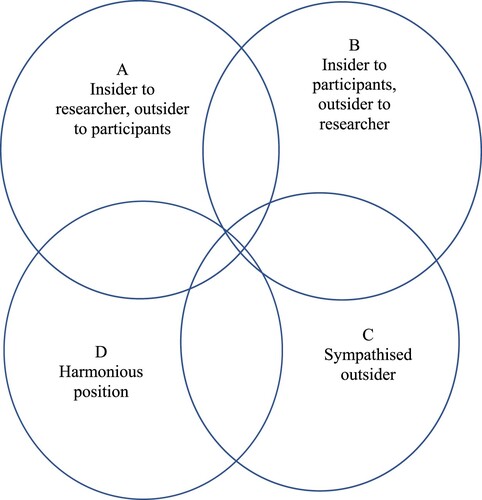

My experiences can be broadly categorized into four distinctive but overlapping sequential positions. The following sections describe how the positionalities were constructed and navigated as well as how those impacted my data and understanding of the context. To do so, I primarily focus on the interview data collected from a male and a female participant so that the gender aspect can be discussed because gender is an element of social structure and contributes to the internal relations between social positions (Kaidesoja Citation2009).

As a male researcher, I could interact less with the female teacher than with the male one. I spent time with the male teacher outside school hours. This was not possible with the female teachers as they had to go home as soon as the school hours finished to take care of family and children. I felt my positionality changed over time but differently for these two teachers due to the different social relationships.

Insider to researcher, outsider to Participants

On a lovely Asian winter morning, I appeared at the chosen school in rural Bangladesh with all my wisdom about in-depth qualitative research acquired from hundreds of pages of theoretical reading about the insider/outsider dichotomy and inbetweener status. I was confident that as an insider, I would be able to access the community very quickly. At the same time, I was also prepared to minimize the drawbacks of being a native researcher, such as missing out on small but significant events (Bonner and Tolhurst Citation2002).

However, the first sentence from a participant after introducing the research topic crushed my confidence and piled uncertainty. The response from the male participant was:

People do research sitting in an air-conditioned room, how they can understand how we suffer here in school and how the research can improve our life!

The more responses I received during the first meeting, the more I realized how naïvely I had misunderstood the dynamics of positionalities. Teachers appeared to be reluctant to talk about their collaborative interactions. The male teacher said:

We do not have any time to collaborate or discuss together … you see, we need to do all sorts of tasks, such as census, vaccination campaign, preparing voter list … .

Time has been mentioned as the most salient barrier to any change in schools (Fullan and Miles Citation1992). The meaning of ‘we do not have time’ has several dimensions (Collinson and Cook Citation2001), which might have been discussed following this response. However, the respondent did not show any intention to discuss this further; rather, he grabbed his student register book and went out of the staff room for his class. I received similar short responses from the female teacher at that point. For instance, she said,

… we have a very good relationship among the colleagues, but we do not have time for collaborative learning … .

Relationships between colleagues can be sensitive and might not be revealed to a stranger. Moreover, a researcher from the UK probably was perceived as someone with higher social status, which may have contributed to the power imbalance and resulted in such superficial responses.

In contrast to Milligan's experience, as she felt like an insider (after she engaged her participants in participative research) in a different cultural context, I discovered myself as an outsider in my very familiar home! However, I was also thrilled to find myself in such a position and started observing the relationship between my positionality and the data I collected. As a result, I went backwards and took time to access the community.

I tried to do so by emphasizing myself as someone who was born, brought up, educated and lived most of his life in a similar context as theirs. I stressed my professional identity as an educator and someone who had previously worked with teachers as a part of a project they participated in to minimize participants’ perceived power gap (Vass Citation2017).

To make a good rapport, I spoke in their local dialect (which I learnt from some of my university fellows who were from the same district), participated in teachers’ social activities outside of the school (), and put on local dress (e.g. Punjabi, Fotua which are traditional men's tops), spend time in tea stalls after school hours and helped some of them to learn using internet on their smartphones. Through these actions, I was trying to show that I was not an exploitative interloper (Gerrish Citation1997, Hammersley Citation2006).

B. Insider to participants, an outsider to researcher

Eventually, over the next couple of weeks, the participants started to gossip, laugh and use slang in front of me. They pulled me into their collegial chitchat and treated me as their friend. However, I was experiencing teachers’ practices unfamiliar to me because I had no prior experience with these dimensions of teachers’ working lives. For instance, I found that teachers were teamed in pairs to share a class in two different sections, which is not a ubiquitous case in Bangladeshi primary schools because of staff shortages in this school. It was an interesting aspect of my research, so I talked about that with the teachers. When I asked about the process of sharing lessons, the male said,

… the headteacher assigns two teachers for two different sections of the same class at the beginning of the academic year. We conduct the same lesson in a week in different sections … .

As I reflected on this response in the night, I thought the teacher could have explained how they prepared the lesson together, whether and how they shared teaching materials etc. He did not do so because he probably assumed I knew how these are done since I was from a similar context. Bernstein’s (Citation1964) language codes, well-used discourses in teacher professionalism and organizational culture studies (Walford Citation2011), were helpful in understanding teachers’ above responses. Bernstein called such responses ‘restricted code’, which needs the listener/reader to explore further by prompt questions or additional investigations. The ‘restricted code’ might be a result of two aspects. First, I kept perceiving myself as an outsider after the first meeting experience. Second, as teachers started to consider me an insider, they started using their colloquial language, which often appeared strange to me.

However, my relationship with the female teacher was not changed much at this stage. I had little interaction with her during school time and no communication after school hours. The female teachers were interested in my family’s lives in England. I shared my experience of living in England during break time with them.

Hence, I felt that I needed to make distance from the male teachers to make my outsiderness apparent to them by reminding them of my researcher (not a teacher) role and asking more prompt questions. Gerrish (Citation1997) suggested that being open, suspending assumptions and avoiding over-rapport are the strategies that help reduce the influence of the researcher's presence on the context. By ‘being open’, he meant being explicit about the role of the researcher. So, I attempted to emphasize my researcher identity by wearing a formal dress and explaining my role during the fieldwork. I also indicated that I did not have much experience as a teacher. These strategies helped the participants and me to understand and acknowledge my outsiderness.

C. Sympathized outsider

My behaviours described in the previous section made the teachers more explicit in their responses. For instance, the male teacher claimed that the teacher guide, provided by the government, had lessened their professional discussion with colleagues as all the instructions about the methods and techniques for each lesson were there. When he said that, they brought the guide and showed examples of how it confined them to fixed pedagogies. He also acknowledged that I might not be aware of the teacher guide. He said,

There are many things, and I discussed some of those earlier. You know … shortage of time … lack of resources … also some government efforts … For instance, the teachers’ guide … Oh, you probably do not know that we have been given a teachers’ guide from the DPE … (then brought the guide and explained the purpose and contents).

Such responses can be called ‘elaborated codes’ (Bernstein Citation1964), allowing me to read between the lines with the least number of prompt questions. Moreover, I could feel their sympathy for my outsiderness when he stopped between sentences and said, ‘Oh, you probably do not know … ’. Such a sympathized outsiderness offered me access to the community and explicitness in the responses.

As the male teacher understood my outsiderness and became explicit in his responses, the female teacher started to trust me. She started to talk about her relationships with different colleagues. At the same time, she explained the aspects from a gender perspective as she understood that as a male researcher, I might not realize the issue of a female teacher. For example, I asked a female teacher whom she talks to least.

She said: Shorafot sir because he is a cousin of my husband …

She spent several minutes explaining how a woman respects her husband's cousins, why she should avoid arguments with him, and how closely knitted Bangladeshi rural society is. While such a response was helpful, it seemed like a mechanical process. I asked the participants any new questions raised from the previous discussion, and they tried to explain as much as possible. But I felt that the construction of knowledge was still a one-way process; I wanted a harmonious relationship where we all learn together.

D. Harmonious positionality

As time went by, the relationship became more harmonious. The participants took me to social and cultural events, invited me to their houses, and ‘ I felt I no longer had to think of a series of questions to encourage participants to elaborate on issues I needed to understand. The learning process was happening spontaneously. Both the participants and I started to see events using similar lenses. At this stage, the interactions between the participants and me were more like discussions and dialogue that were embedded in day-to-day conversation rather than interviews. During such discussions, the participants acknowledged my researcher's positionalities. They understood my research questions and pointed out any examples that may help me answer my research questions in our natural conversations. For instance, there was a discussion about land price hikes in Bangladesh in a tea-stall conversation among local primary teachers (from different schools). After the conversation, the male teacher said:

Oh, I forgot to mention one thing. We have a cooperative society, and four of our colleagues are members. We deposited money together to buy a plot of land together. I think this can be an example of collaboration for your study.

I was taken as a member of their meetings, distributed in different groups during group work, asked for an opinion on their decision-making process, invited to their social and family programmes, and spoke slang without hesitation in front of me! I was careful in getting involved in their professional decision-making since I did not want to influence their habitual activities. Yet, I could see that my presence was not altering their activities, and the inner dimension of their collaboration was becoming more apparent to me as a member of their community. The learning in this situation was both ways.

Moreover, conversations between the participants (both male and female) and I became more unstructured than before. I often did not need to look at my interview agenda; discussions were followed naturally. For instance, after a government official visited the school, I asked the teachers how much they thought the inspector's visits were helpful. The male teacher mentioned the school community as a ‘family’ where he included me. Other teachers (including the female teachers) joined and participated in the discussion. The conversation was:

Shorafot Hossain: Let’s think that we are in a family; we have a very simple lunch like rice with mashed potato and lentils. We will manage with that. But if a guest comes, we will try to arrange something special, at least scrambled egg … or some sort of fish … . … that’s how we will treat him (the guest) … our lessons are similar … we teach in our own way. But if there someone comes to observe, naturally we …

Benu Akter: At least fry an egg … (Laughter)

Sonu Shaha: We fill our stomachs anyway …

Shorafot Hossain: But you have just become a part of our family, we share the typical lunch with you, so you can see the real lesson we conduct … but if you come all of a sudden (like a government inspector) … You won’t see the regular practice …

Me: I came to taste the mashed potato and lentils (laugh)

Indeed, I felt like a family member in the school towards the end of my fieldwork. This relationship provided me with a culturally rich understanding of the data I collected. I was able to develop a longer-term friendship with the participants and I still have frequent communication with them. However, such a position was not possible to achieve by only the researcher's endeavour. Interactions between the participants’ views of a researcher and my perception of my positionalities evolved into such positions. Yet, I had to maintain several strategies to influence the participants’ views to ensure a deeper understanding of the context. The experiences of the positionalities can be summarized by .

The diagram above resembles very distinctive but overlapping positionalities. The first circle represents a situation where the researcher perceived himself as an insider, but participants considered him an outsider. In the second one (clockwise), the participants considered the researcher an insider, but the researcher found the context strange. Third, both participants and the researcher acknowledged the limitation of knowledge of the researcher about the context and the participants are sympathized to the outsiderness of the researcher. And finally, a harmonious relationship where both researcher and participants are sympathetic to each other. The positionalities overlap and continuously shift (Naples Citation1996, Nakata Citation2015, Milligan Citation2016, Barnes Citation2021). I was never a complete insider or a complete outsider but an inbetweener. However, my positionality was not liquid (Thomson & Gunter Citation2011, Barnes Citation2021) as I deliberately changed my position. Hence, I found my experience more aligned with Milligan's, an active inbetweener. However, my positionality was not determined only by my agency but also by how my participants saw me.

Hence, I argue that to obtain an authentic understanding of the context, a researcher needs to navigate through the different positionalities by being reflexive on his/her strategies and the data collected and on the participants’ agency. I acknowledge that a specific positionality may not be useful (and possible) for all research. Thus, how a position impacts, the data collection and interpretation needs to be reflected on and documented (Hammersley Citation2006). How my positions impacted data, and the strategies I adopted to navigate different positions are described above. reflects the diagram above and summarizes the discussion.

Table 1. Positionalities and their effects on data.

Conclusion

In this paper, I argued that the researcher's positionalities are products of a complex interaction of agencies of the researcher and participants. While this proposition acknowledges the contemporary argument for an inbetweener position (Milligan Citation2016, Barnes Citation2021, Jimenez et al. Citation2021) and discards the idea of insider/outsider dichotomy, it argues that an inbetweener position is neither a result of the field context (Thomson and Gunter Citation2011, Barnes Citation2021) nor solely the agency of the researcher (Milligan Citation2016, Jimenez et al. Citation2021) but a combination of both. This means that a researcher's positionality is not just a fluctuating and permeable social location due to only the continuously evolving nature of his/her professional identity (Barnes Citation2021) or just the researcher’s actively navigated situation. As I experienced during my fieldwork, positionality is a perceptual construction of identity shaped by the interactions between researcher’s and participants’ perception of the researcher, their agency and the social structure.

In this paper, I discussed how I adopted several strategies to negotiate my positionalities and how participants’ perceptions of a researcher and their agency and the social norms and values contributed to my continuously changing positionalities. I also reflected on how different positionalities impacted the data I collected. For instance, during my fieldwork, I encountered four distinguished but overlapped positionalities: the different combinations of my perceived identities by myself and the participants. The combinations are; insider to the researcher but an outsider to the participants, insider to participants but an outsider to the researcher, the outsiderness of the researcher acknowledged by both parties, and a harmonious positionality.

A Critical Realist (Scott Citation2005, Bhaskar Citation2013) philosophy helped conceptualize the construction of the researcher's positionality. According to a CR theory, there is an independent reality which cannot be observed, but the unobservable structures cause observable events and social relations. The social world is layered, complex and an open system. The different entities (e.g. people such as teachers, organizations/groupings such as the Cooperative, policies, plans, goals etc.) have properties that support mechanisms which can enable, constrain or block mechanisms of other entities. For my research, many of these mechanisms were latent but were activated by personal power (such as my actions or those of the participants) or by the power of social structures over personal actions (e.g. with gender).

For instance, my positionalities were different for different people simultaneously. I acknowledge that gender, along with other cultural dimensions, is one of the most significant factors shaping my positionalities. With the same strategy I adopted to access the teachers’ community, I had different accessibilities to a male and a female participant. This was not due to a mere individual characteristic of the participants, but the social construction of gender roles was responsible for such difference. Hence, I argue that the researcher’s and participants’ agency and the social structure affect the positionality of a researcher.

Therefore, the current practice in graduate training, e.g. PhD, may reconsider the definition and development of researchers’ positionality. While the current narratives in this area discuss the role of reflexivity in developing positionalities, these most encompass the researcher's agency. The participants’ role and the context's social structure must be considered in such discussions.

I acknowledge that a single positionality may not be sufficient to obtain the required amount and standard of data for different research and thus appreciate all the positionalities. A careful scrutinization of different positionalities and their respective effect on the data and analysis should be reported (Hammersley Citation2006).

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the ESRC for funding the time spent for developing this paper. I thank Professor Freda Wolfenden, Dr. Alison Buckler and Dr. Ian Eyer for their intellectual support in developing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelman, C., Adelman, C., and Walker, R., 1976. A guide to classroom observation. London: Routledge.

- Adu-Ampong, E.A., and Adams, E.A., 2020. “But you are also Ghanaian, you should know”: negotiating the insider–outsider research positionality in the fieldwork encounter. Qualitative Inquiry, 26 (6), 583–592.

- Anthias, F., 2002. Where do I belong? Narrating collective identity and translocational positionality. Ethnicities, 2 (4), 491–514.

- Archer, M.S., and Archer, M.S., 2003. Structure, agency and the internal conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arthur, L., 2010. Insider-outsider perspectives in comparative education. Paper presented at the Seminar Presentation at the Research Centre for International and Comparative Studies.

- Atkinson, P., 2007. Ethnography: principles in practice. London: Routledge.

- Barnes, G.-J., 2021. Researcher positionality: the liquid inbetweener. PRACTICE, 1–8. DOI:10.1080/25783858.2021.1968280.

- BERA (British Educational Research Association). 2018. Ethical guidelines for educational research. 4th ed. London. Available from: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2018/06/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-for-Educational-Research_4thEdn_2018.pdf?nored irect = 1.

- Berger, R., 2015. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15 (2), 219–234.

- Bernstein, B., 1964. Elaborated and restricted codes: their social origins and some consequences. American Anthropologist, 66 (6), 55–69.

- Bettez, S.C., 2015. Navigating the complexity of qualitative research in postmodern contexts: assemblage, critical reflexivity, and communion as guides. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28 (8), 932–954.

- Bhaskar, R., 2013. A realist theory of science. London: Routledge.

- Bonner, A., and Tolhurst, G., 2002. Insider-outsider perspectives of participant observation. Nurse Researcher (Through 2013), 9 (4), 7.

- Bossert, S., Stubbs, M., and Delamont, S., 1977. Review of explorations in classroom observation. American Educational Research Journal, 14 (2), 180–181. doi:10.2307/1162711.

- Bourdieu, P., 1990. Structures, habitus, practices. In The logic of practice, edited by Pierre Bourdieu, 52–65. California: Stanford University Press.

- Bradbury-Jones, C., 2007. Enhancing rigour in qualitative health research: exploring subjectivity through Peshkin's I's. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59 (3), 290–298.

- Cho, S., and Yi, Y., 2019. Intersecting identities and positionality of US-based transnational researchers in second language studies. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42 (4), 414–427.

- Collins, P.H., and Bilge, S., 2020. Intersectionality. Cambridge: Wiley and Sons.

- Collinson, V., and Cook, T.F., 2001. “I don’t have enough time”-teachers’ interpretations of time as a key to learning and school change. Journal of Educational Administration, 39 (3), 266–281.

- Delamont, S., 1975. Participant observation and educational anthropology. Research Intelligence, 1 (1), 13–21. NOT REFERRED TO IN MAIN PAPER (Inserted in page 5).

- Delph-Janiurek, T., 2001. (Un) consensual conversations: betweenness,‘material access’, laughter and reflexivity in research. Area, 33 (4), 414–421.

- DiAngelo, R., and Sensoy, Ö., 2009. “We don't want your opinion”: knowledge construction and the discourse of opinion in the equity classroom. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42 (4), 443–455.

- Duff, P.A., 2002. The discursive co-construction of knowledge, identity, and difference: an ethnography of communication in the high school mainstream. Applied Linguistics, 23 (3), 289–322.

- Fullan, M.G., and Miles, M.B., 1992. Getting reform right: what works and what doesn't. Phi Delta Kappan, 73 (10), 745–752.

- Gerrish, K., 1997. Being a'marginal native': dilemmas of the participant observer. Nurse Researcher, 5 (1), 25–34.

- Hammersley, M., 2006. Ethnography: problems and prospects. Ethnography and Education, 1 (1), 3–14. (This was taken off during the revision).

- Hellawell, D., 2006. Inside–out: analysis of the insider–outsider concept as a heuristic device to develop reflexivity in students doing qualitative research. Teaching in Higher Education, 11 (4), 483–494.

- Jimenez, A., Abbott, P., and Dasuki, S., 2021. In-betweenness in ICT4D research: critically examining the role of the researcher. European Journal of Information Systems 31 (1): 1–15.

- Kaidesoja, T., 2009. The concept of social structure in roy bhaskar’s critical realism. JyväskyläStudies in Education, Psychology and Social Research 376, University of Jyväskylä.

- Kanuha, V.K., 2000. “Being” native versus “going native”: conducting social work research as an insider. Social Work, 45 (5), 439–447.

- Krauss, K.E., 2018. A confessional account of community entry: doing critically reflexive ICT4D work in a deep rural community in South Africa. Information Technology for Development, 24 (3), 482–510.

- McGinity, R., 2012. Exploring the complexities of researcher identity in a school based ethnography. Reflective Practice, 13 (6), 761–773. (Taken off during revisions).

- Measor, L., and Woods, P., 1984. Changing schools: pupil perspectives on transfer to a comprehensive. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Milligan, L., 2016. Insider-outsider-inbetweener? Researcher positioning, participative methods and cross-cultural educational research. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46 (2), 235–250.

- Mullings, B., 1999. Insider or outsider, both or neither: some dilemmas of interviewing in a cross-cultural setting. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 30 (4), 337–350.

- Nakata, Y., 2015. Insider–outsider perspective: revisiting the conceptual framework of research methodology in language teacher education. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 38 (2), 166–183.

- Naples, N.A., 1996. A feminist revisiting of the insider/outsider debate: The “outsider phenomenon” in rural Iowa. Qualitative Sociology, 19 (1), 83–106.

- Palaganas, E.C., et al., 2017. Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. Qualitative Report, 22 (2): 426–438.

- Pawson, R., 2013. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. London: Sage.

- Raghuram, P., Noxolo, P., and Madge, C., 2014. Rising Asia and postcolonial geography. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 35 (1), 119–135.

- Rahman, M.S., 2020. Unexplored areas of teacher collaboration: evidence from a Bangladeshi rural primary school. Milton Keynes: The Open University.

- Sala-Bubaré, A., et al., 2022. Early career researchers making sense of their research experiences: a cross-role and cross-national analysis. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52 (5), 748–767.

- Scott, D., 2005. Critical realism and empirical research methods in education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 39 (4), 633–646. (Taken off during revisions).

- Smith, L.T., 2021. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Srivastava, P., 2006. Reconciling multiple researcher positionalities and languages in international research. Research in Comparative and International Education, 1 (3), 210–222.

- Sultana, F., 2007. Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 6 (3), 374–385.

- Thomson, P., and Gunter, H., 2011. Inside, outside, upside down: The fluidity of academic researcher ‘identity’in working with/in school. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 34 (1), 17–30.

- Tikly, L., 2015. What works, for whom, and in what circumstances? Towards a critical realist understanding of learning in international and comparative education. International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 237–249.

- Trahan, A., 2011. Qualitative research and intersectionality. Critical Criminology, 19 (1), 1–14.

- UNESCO, 2015. Education for all global monitoring report: policy paper, Paris.

- Vass, G., 2017. Getting inside the insider researcher: does race-symmetry help or hinder research? International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 40 (2), 137–153.

- Walford, G. 2011. “The Oxford Ethnography Conference: a place in history?” Ethnography and Education 6 (2): 133–145.

- Walker, R., and Adelman, C., 1976. A guide to classroom observation. London: Methuen.

- Woods, P., 1986. Inside schools: ethnography in schools. London: Routledge.

- Wragg, E.C., Stubbs, M., and Delamont, S., 1978. Review of explorations in classroom observation British. Journal of Educational Studies, 26 (2): 197–19910.2307/3120099.

- Young, M.W., 2017. The ethnography of Malinowski: The Trobriand Islands 1915-18. London: Routledge.