ABSTRACT

This article contributes to the discussion on research methods pedagogy by adding a technological dimension to Nind’s use of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) in research methods education (RME). Within a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning approach, this research-inspired reflection is based on the literature, on the scholar’s praxis and on the on-going design-based research project she has been conducting since 2014. Trained in educational technologies more than 20 years ago, she shares an initial understanding of the use of the TPACK framework for the teaching of research methods in education. Findings include initial definitions of each type of individual knowledge (CK, PK, TK), overlapping knowledge (TPK, TCK, PCK) and a proposal for TPACK as a whole. Secondly, the findings show that technology appears to be a revealing indicator of current praxis in RME, inviting scholars to question methodolatry and technodolatry. As a corollary, Content Knowledge (CK) needs more attention to reconnect RME with its philosophical foundations. Research method teachers and students in the social sciences will foremost benefit from this study and are invited to contribute to the debate within a broader collective intelligence endeavour.

Introduction

Research methods education (RME) in the social sciencesFootnote1 is key and has a big responsibility towards science and society because it trains future researchers and contributes to shaping academic domains, e.g. education.

In the past decade, researchers have studied RME and uncovered valuable insights for praxisFootnote2 in terms of pedagogical culture (Wagner et al. Citation2011, Earley Citation2014, Wagner et al. Citation2019, Garner et al. Citation2009, Kilburn et al. Citation2014, Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2016, Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2018a, Nind and Katramadou Citation2022). RME has been studied from the perspective of different stakeholders, including experts (e.g. Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2016) and students (e.g. Nind Citation2019). It has also been studied using different frameworks and methods: for instance, a leadership and management framework based on the work of Stacey (Citation2002) combined with an expert panel method (Galliers and Huang Citation2012) in Lewthwaite and Nind (Citation2016); a research synthesis framework that relies on Cooper (Citation1998) in Earley (Citation2014); and a systematic review, in Wagner et al. (Citation2019) or in Nind and Katramadou (Citation2022).

Applying Shulman’s (Citation1987) pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) framework to RME, Nind (Citation2020) describes two types of knowledge that research methodology teachers in the social sciences need to develop: generic and specific PCK (presented below in the literature review section). This article extends this specific work of Nind (Citation2020) by discussing the technological dimension, drawing on the TPACK framework (Mishra and Koehler Citation2006, Koehler et al. Citation2013, Koehler and Mishra Citation2005, Herring et al. Citation2016, Mishra Citation2019, Phillips Citation2017), which in turn is based on Shulman’s PCK framework. Technology Knowledge (TK) is defined as deep and broad essential technological understanding; it refers to the ability to develop digital literacy to the extent that technology can be used in productive and creative ways in a given situation (Koehler et al. Citation2013). TK is thus multidimensional and covers various levels of expertise, from specialized research-method teaching environments and software (e.g. computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, CAQDAS) or artificial intelligence (Schäffer and Lieder Citation2023) (e.g. computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS); artificial intelligence, Schäffer and Lieder Citation2023) to non-specialized technology that is used for research methods education purposes (e.g. a wiki format textbook), as well as broader digital literacy (e.g. innovation and creativity in research methods education).

TK has been largely experienced as a key skill, especially since the Spring 2020 with the worldwide lockdown. The Covid19 crisis has drawn attention to issues that distance education specialists have studied for the last 40 years in the field of instructional design (Honebein and Reigeluth Citation2021) and that crystallised at some point in the media debateFootnote3 (Kozma Citation1994, Clark Citation1994). Distance education, i.e. when teachers and learners are not physically present in the same place, has a fundamental role which is to mediate interactions through technology. In this sense, media, a specific instance of technology, serve as links that support learners’ skills and knowledge development (Jonassen Citation1984, Jonassen et al. Citation1994). In the learning and teaching equation, making all sort of technology transparent is important to be aware of its potential influence in the process. Technology can also be explored as a revealing indicator of social processes and realities. Reflect critically on the various roles of TK, attempt to better define them, and raise awareness among teachers in the context of RME is thus considered timely.

This article takes the form of a research-inspired reflection. It is based on the literature, on the scholar’s praxis and on an on-going design-based research project on research method teaching and learning . It is conducted in a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) approach (Boyer Citation1990) and structured as follows: first, a literature review focused on RME. Then, the nature of education as a scientific domain is discussed because it is the teaching context in which RME is explored. The paper’s methodology is then provided. Second to last, the scholar shares the use of a TPACK framework in RME, defining TK, PK, CK and the overlapping forms of knowledge (TCK, PCK and TPK) for further elaboration by researchers and practitioners. Finally, the findings are discussed and the paper is concluded.

Literature review: research methods education

Historical context

A decade ago, Garner et al. (Citation2009) opened a new avenue for research with their ground-breaking book that raised awareness of the importance of research methods pedagogy. Since the publication of this seminal work, much research has been conducted in this area, including a research synthesis (Earley Citation2014), a thematic review (Kilburn et al. Citation2014), one systematic review limited to qualitative methods teaching (Wagner et al. Citation2019) and one recent systematic review exploring pedagogic approaches and strategies between 2014 and 2020 (Nind and Katramadou Citation2022). The most active research team on research methods education in the social sciences over the last few years is led by Melanie Nind and based in the United Kingdom (UK).

Indeed, the UK has invested significantly in capacity-building in the area of social-sciences RME to prepare for the rising knowledge society (Kilburn et al. Citation2014, Valimaa and Hoffman Citation2008). In this context, Nind is leading a National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) project entitled ‘The Pedagogy of Methodological Learning’, which is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); the project began in 2004 and will continue through to 2024.Footnote4 Through this project (and prior to it), Nind’s team has produced literature reviews (e.g. Nind Citation2009, Bengry-Howell Citation2011, Nind Citation2013, Kilburn et al. Citation2014, Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2015b) and disseminated findings of empirical studies (e.g. Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2020, Nind Citation2019, Lewthwaite Citation2019, Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2018b, Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2018a, Nind and Vinha Citation2016, Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2016, Nind et al. Citation2015, Wiles Citation2013).

Nind has coordinated a Handbook of Teaching and Learning Social Research Methods (Nind Citation2023) and Albero and Thievenaz (Citation2022) have published a similar encyclopaedia-like endeavour on the topic of RME in the social sciences – 1800 pages. Nind’s team has also produced practical guides for research method trainers, which are available on the project’s website. These guides cover both face-to-face teaching and online teaching; they provide advice on designing courses for diverse learner groups, structuring and sequencing course content, and promoting learning with data (Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2015a, Collins Citation2019). They also cover principles of effective pedagogy, such as promoting active engagement of the learner (Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2015a). The team’s article on pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) for RME Nind (Citation2020) gives precise recommendations to address important pedagogical challenges.

Pedagogical content knowledge

PCK refers to Shulman’s (Citation1987) concept of transforming content so it is suitable for teaching (Koehler et al. Citation2013). This idea is also central to the French concept of transposition didactique, i.e. how to modify content to make it teachable (Chevallard Citation1991). In research methods education, PCK consists of both generic and specific knowledge enacted through certain approaches, strategies, tactics and tasks (Lewthwaite Citation2019, Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2020, Nind Citation2020). Generic PCK includes organizational skills related to people and subject matter, pacing skills and pedagogical strategies that are found in any teaching and learning situation. Specific PCK is knowledge that is particular to research methods education; it deals largely with how to teach with, through and about data. This includes pedagogic decision-making about authentic data; pedagogic action as a result of immersion in data; narration constructed from data; and the theory-logic-decision-action process (Nind Citation2020, p. 196).

To contextualize PCK for research methods education, Nind and Lewthwaite (Citation2020) suggest a typology of research methods teaching that includes the core categories of ‘approach’, ‘strategy’, ‘tactics’ and ‘tasks’. ‘Approach’ refers to how teachers go about their work in a way that coheres around a theory, set of values or principles. ‘Strategy’ refers to goal-directed planning for implementing an approach. ‘Tactics’ refer to the way in which strategies are executed when planning becomes procedural and specific to a given context. Finally, ‘tasks’ refer to what learners or teachers are required to – or actually – do.

The need to reconsider RME

Scholars express a need to reconsider, broaden and deepen RME (e.g. St. Pierre Citation2022, Tesar Citation2022). Drawing on various philosophical approaches, social theories, history of sciences and social sciences that move away from dominant conceptions and ways of teaching and learning research methods, scholars invite us to conduct research differently and change the praxis related to RME.

St. Pierre (Citation2022) explicitly refers to post-social science research as one possible avenue. As a quick reminder, and in the very broad lines, positivist epistemologies predict, comprehensive (interpretive) epistemologies understand, critical epistemologies emancipate, and all post-epistemologiesFootnote5 deconstruct and prepare for new inquiry (Lather and St. Pierre Citation2007). Post-digital involves to critically examine the effects of digital technology on education, economics, ethics, humanity, and the environment (Ball and Savin-Baden Citation2022). It aims to challenge the impact of the digital world on these areas. As a concept, context, and practice, post-digital is fluid, ‘blending the person, the digital, and machines with all interrupting all’ (Savin-Baden Citation2022b, p. 6).

What reconsidering RME might mean can be previewed through new players arriving in the field, like epistemologies of the South (e.g. de Sousa Santos Citation2014, de Sousa Santos and Meneses Citation2020) or open dialogue with other knowledge systems and open engagement of societal actors promoted by Open Science (UNESCO Citation2021). Open Science promotes technology that is participatory and shared in the form of common good, specifically with the high pace and the successive technological revolutions (UNESCO Citation2023, Escaño and Mañero Citation2022). Epistemologies of the South are founded on three assumptions which read as follows: (i) there is a much broader understanding of the world than that unique to the Global North; (ii) the diversity of the world is infinite and there are different ways of thinking, feeling, acting and different relationships between human and non-human beings; and, (iii) plural forms of knowledge must be sought because there is no general theory that can adequately cover all the infinite diversities of the world. Epistemologies of the South thrive to recognize the right of different forms of knowledge to coexist, and advocate for an active recognition of the need for diversity (Descarpentries Citation2021, Descarpentries and Charmillot Citation2022).

Avenues to reconsider RME are thus diverse and this means that it is expected to change in a near future. Furthermore, this need to renovate RME resonates with the claim that the research currently being conducted in education sciences is not that which is actually needed (Reeves and Lin Citation2020).

Education as an academic domain

As RME is being explored in the field of education sciences, it is considered important to recall some basic information. Education as an academic domain started to be institutionalized about a century ago in the Global North (Hofstetter and Schneuwly Citation2002, Hofstetter and Schneuwly Citation2001, Lagemann Citation2000). As an academic domain, education presents a particularity in that it encompasses both discourse and action (Bedin et al. Citation2019): discourse guides action and vice versa. Ideological discourse, which justifies and prescribes educational action, is dominated by different conceptions – e.g. religion, humanism, laicity. The practical side of the domain, which prescribes action, is codified from the experience of practitioners – their practice- insofar as this remains in line with the ideological prescription. The concept of praxis captures the continuity between theory (discourse) and practice (action) (Evans Citation2007, Carr and Kemmis Citation1986, Kemmis and Edwards-Groves Citation2018, Freire Citation1994). It embodies how theory and practice are deeply entangled and marked by history and context: praxis is both an ‘action full-of-thought’ and a ‘thought-full-of-action’ (Evans Citation2007, p. 554) in reference to Freire (Citation1994).

The impact of this particularity can be seen throughout the history of education as a scientific research domain (Van der Maren Citation2019). Three historical periods can be distinguished: premodern, modern and postmodern. In premodern times (i.e. the seventeenth century), research in education did not exist as such. However, the divide between discourse – which was dominated primarily by religion, but also humanistic considerations – and practice during this time has already been attested. With the advent of positivism in the modern era (nineteenth century), experimental research in education began, divided into two main areas: psycho-pedagogical research, which addressed psychological aspects of pedagogy in areas such as learning, affective development, etc; and experimental pedagogy, which involved designing learning environments based on models drawn from psychological knowledge and testing their efficiency through experiments. In the postmodern era (after 1945), education research was reoriented along four lines: (1) proposing complementary models to experimental research; (2) seeking models that diverge completely from positivist methodologies and the use of statistical data; (3) changing the object of study from the classroom to any training situation (e.g. lifelong training, managing, implementing, designing training, etc.); (4) promoting forms of collaborative research in which the researcher and the practitioner both play a distinct role, to reconcile researchers and practitioners (Van der Maren Citation2019, Mialaret Citation2016). This is of course one interpretation of the young history of education sciences in the Global North. A need to revisit this history today seems to be present (e.g. Guibert Citation2021, Laot and Rogers Citation2015) but it goes far beyond the purpose of this article.

Research methods is a subject that is commonly taught in higher education (HE) programmes. It is a subject that has generated considerable research. So much so that it appears in the top eight most studied HE subjects discussed in systematic reviews and meta-analyses under the main topic of teaching and learning (Tight Citation2019, ).

Table 1. A SoTL inquiry using Hubball and Clarke (Citation2010)’s categories.

The absence of topics related to the history or philosophy of education in these reviews should be noted. In other words, studies challenging the bedrock on which education as a science stands, i.e. research methods and by extension RME as a praxisFootnote6, are either too old, not in English (e.g. Hameline Citation1979) or emerging (e.g. Laot and Rogers Citation2015, Tesar Citation2022) to be considered in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Method

The method developed within this article is based on a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) approach (Haigh and Withell Citation2020, Boyer Citation1990, Miller-Young and Yeo Citation2015, Hubball and Clarke Citation2010). It takes the form of a reflection stemming from: (1) a larger design-based research (DBR) project (McKenney and Reeves Citation2019, Collins et al. Citation2004) centred around research methods education over several years (Class et al. Citation2014, Class Citation2016, Class and Akkari Citation2021, Class Citation2020b, Class Citation2017, Class and Schneider Citation2019; Class et al. Citation2021, Class Citation2022b, Citation2022a); (2) the literature; and (3) on the scholar’s praxis. Furthermore, as noted in the data section below, data from the most recent cycle of the DBR provide important inspirational material for this reflection. For this reason, the researcher refers to it as a research-inspired reflection. The reflection is inspired by the DBR and is to be seen as a finding within this larger DBR, i.e. a necessary step before analysing the data.

The following sections outlines the SoTL approach, structured by the statement of the overall guiding process, the statement of the position of the teacher and of the researcher, and the statement of the data.

Scholarship of teaching and learning process

Using Hubball and Clarke (Citation2010, p. 4) categories, outlines the guiding SoTL research question and resulting process to reach findings.

The guiding research questions reads: From a teachers’ perspective, and with reference to the TPACK framework, how can the different types of knowledge be defined for the teaching of research methods in education?

Who is the teacher and on which learning theories does her teaching rely on?

The scholar is an educational technologist and research methods teacher who teaches in several blended and online programmes. For the past seven years, she has taught a 2-ECTSFootnote7 qualitative research methods course in the blendedFootnote8 Master of Teaching and Learning with Technologies (MALTTFootnote9) programme of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at the University of Geneva. In parallel, she has taught a 1-ECTS course on research approaches and methods for the online university degree ‘Research for Digital Education’Footnote10, which is intended to help international francophone students, who hold a master’s degree and want to start a PhD in digital education, to structure their research proposal. Within these teaching experiences, under the guidance of her colleague and, afterwards with students’ renewable assignments, the scholar has contributed to a research method textbook on a wiki (Class and Schneider Citationn.d.).

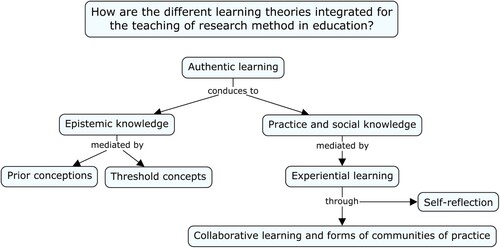

The various learning theories on which the scholar’s teaching is based pertain to an overall socioconstructivist approach, which considers learning as meaning making and learners as active knowledge builders in continual interaction with their sociocultural environments (Jonassen Citation1991, Jonassen and Land Citation2012, Woo and Reeves Citation2007). Within this broad approach, there are five major learning theories that inform her teaching practice. Two support the development of epistemic knowledge and the three remaining ones support the development of social and practice knowledge ().

The first is authentic learning (Herrington et al. Citation2014). This theory is based on presenting students with a real-world problem that is ill-defined, has real-world relevance and is embedded in a single substantial complex task, while providing them with resources and scaffolding opportunities to help them construct solutions. Authentic learning is rooted in theories of situated cognition (Hutchins Citation1995) and legitimate peripheral participation (Lave and Wenger Citation1991), which are both social forms of learning.

The second is Usher’s (Citation2018) theory of experiential learning, which is associated with postmodernism and, more specifically, with theories of power. This theory uses graphic representation with four quadrants to illustrate the degree to which an individual can be empowered through experience. Each quadrant represents the pedagogy and epistemology of experiential learning according to given practices, showing what the emphasis is on (Appendix 1).

The third is community of practice (Wenger Citation1998, Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2020), which is a form of social learning that emphasizes the concepts of common interest, participation and value. Value is defined in terms of agency and meaningfulness of participation. More precisely, participation is perceived as leading to a difference that matters, thereby generating value (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2020).

The fourth theory of learning, which operates at a finer granularity, is threshold concept theory (Meyer et al. Citation2010, Meyer and Land Citation2003, Nicola-Richmond Citation2018, Stopford Citation2021). According to this theory, certain key concepts are necessary to fully grasp the meaning of a given field of knowledge. These concepts act as gatekeepers in the sense that once someone crosses through the gate, their understanding is irrevocably changed. Crossing the gate is a process that leverages liminality: learners first initiate a movement to change their understanding, then find themselves in troublesome, confusing knowledge zones. Once the new knowledge is integrated, learners abandon their former understanding and re-anchor their new understanding in new epistemologies and ontologies. At the end of this process, their understanding is transformatively and irreversibly altered.

The fifth is the theory of prior conceptions (Meyer et al. Citation2005, Brew Citation2001), which is closely related to threshold concepts and conceptual change (Amin and Levrini Citation2018). It consists of identifying the conceptions learners already have when they arrive in the course, with the aim of understanding where they stand and building their learning from that point.

Who is the researcher and what are her worldviews?

The scholar has been involved in Design-Based Research (DBR) since the beginning of her doctoral studies, but also for her studies on research methods, which allowed her to experience research from a science and society approach (Bedin and Franc Citation2019). Indeed, DBR is a participatory research approach in which the reception – the community in, with and for which knowledge is produced, as well as the problem of practice – the command, are fully considered. The praxis of the scholar was largely influenced by this approach (e.g. Class Citation2020a). In addition, an epistemological background made of absences and emergences (de Sousa Santos Citation2016), ‘ontological epistemology of participation’ (Giri Citation2021, p. 369) and creativity (Hayes Citation2007, Class Citation2022b) guided her. More recently, she gained new understandings from her interaction with research method teachers (e.g. Savin-Baden Citation2022a, Charmillot Citation2020, St. Pierre Citation2006) and her active engagement to understand Openness (e.g. Peters Citation2014, Deimann Citation2019). DBR paved the way to opening up to diverse knowledge systems and concepts like ‘liquid methodologies’ (Savin-Baden Citation2022a). She currently sees herself in a liminal space, trying to bridge the gap between what she has been taught and has taught, which aims to reproduce, and post-inquiry, which aims to create.

Data and working towards findings

Data collection method of the larger DBR study include questionnaire, semi-structured interviews and real data from learning environments. The findings that are of most interest to the current study, with a focus on how they have influenced those of the present study, can be summarized very briefly as follows.Footnote11

For the present article, the research-inspired reflection stems foremost from interviews conducted with francophone research methods teachers, the focus group conducted with anglophone scholars, and the interviews conducted with DBR experts in 2020.Footnote12 This is the reason why we call it a research-inspired reflection. Indeed, getting all the data processed and ready for analysis took about a year (Class et al. Citation2021). From oral interactions with participants by the means of interviews, through to verifying the outsourced transcription, interacting with participants in written form on the final transcription to be used, and finally to identifying what needs to be pseudonymised when participants expressed the desire to remain anonymous, gave the scholar different ‘moments in time’ to reflect on the knowledge shared through this data. This, together with the presently shared reflection, was considered necessary preliminary work to be ready to apprehend the analysis in its full complexity.

Findings: exploring tpack for the teaching of research methods in education

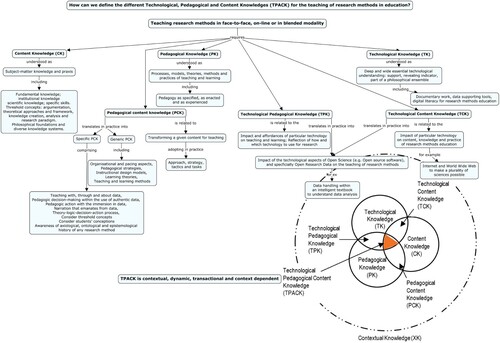

This section defines each type of individual knowledge (CK, PK, TK) and overlapping knowledge (TCK, PCK, TPK) for research methods education to suggest the use of a TPACK framework (). It takes education as an example of domain in the social sciences.

Figure 2. Suggesting a first draft of the use of the TPACK framework (Mishra Citation2019) for the teaching of research methods.

Defining content knowledge

CK refers to subject-matter knowledge or so-called theoretical artefacts – concepts, theories, frameworks – and ‘established practices and approaches toward developing such knowledge’ (Koehler et al. Citation2013, p. 14 citing Shulman Citation1986). Researchers and practitioners agree that engaging in research requires curiosity, open-mindedness, theoretical understanding, procedural knowledge and practical skills (Kilburn et al. Citation2014). In other words, to develop a deep and broad understanding of CK in RME, all these skills are prerequisites. In the context of research methods education for education sciences, there cannot be a one-size-fits-all CK: CK is inherently diverse.Footnote13

For instance, Van der Maren (Citation2019) competency framework includes the following types of CK: (1) fundamental knowledge, comprehending epistemology and philosophy of the social sciences, critical history of research in education, and ethics of researchFootnote14; (2) institutional knowledge, including the deontology of research in education, the status of the researcher and of publications, forms of institutional valuing, and forms of interacting with funding agencies and funding management; (3) scientific knowledge, including established knowledge in education and contributing disciplines, research methodology by objective (fundamental, developmental, action-research, analysis of activity), and research proposal and data analysis (i.e. qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method); (4) technical and digital knowledge, such as literature review techniques, data collection techniques, and software for analysing qualitative, quantitative and textual data; and (5) specific skills, such as problematizing (in the sense of stating the problem), documenting, planning, and operationalizing research, interpreting and disseminating results, and transferring knowledge learnt through research.

For each of these broad areas of competencies, by using threshold concepts, the Integrated Threshold Concept Knowledge (ITCK) framework (Timmermans and Meyer Citation2019) helps to define CK at a finer granularity. The ITCK framework supports teachers’ adoption of scholarly practices through a 7-step process. These steps read as: (1) identifying and analysing threshold concepts; (2) making expert understanding explicit; (3) situating threshold concepts within the discipline to make its underlying epistemologies transparent and understandable; (4) designing learning outcomes; (5) planning evaluation; (6) generating a repertoire of teaching and learning activities; and (7) adopting scholarly practices in order to reflect on and study teaching and learning practices from a SoTL perspective (see in Timmermans and Meyer Citation2019, p. 364).

Thresholds in research methods education have been studied for more than a decade (Kiley and Wisker Citation2009, Kiley Citation2019, McKenna Citation2017, Thripp Citation2016, Kiley Citation2015, Chatterjee-Padmanabhan et al. Citation2019, Chatterjee-Padmanabhan and Nielsen Citation2018, Keefer Citation2015), and researchers have identified the following threshold concepts: argumentation, theoretical approaches and framework, knowledge creation, analysis and research paradigm (Kiley and Wisker Citation2009). This work forms a good basis from which to engage in the ITCK framework’s 7-step process to better investigate CK in research methods education.

Defining pedagogical knowledge

Although pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) has already been defined in the literature review section, it is necessary here to define pedagogical knowledge (PK) separately, as it deals essentially with notions of pedagogy. PK refers to deep knowledge about the processes, models, methods and practices of teaching and learning, including evaluation. It requires mastery of underlying psycho-pedagogical principles and theories (e.g. cognitive load, zone of proximal development, engagement, motivation) (Koehler et al. Citation2013).

Within a sociocultural theoretical perspective (i.e. learning happens everywhere and not just in schools), Nind et al. (Citation2016) provide a three-dimensional analytic tool to explore PK as a dynamic phenomenon. The first dimension is ‘pedagogy as specified’, which refers to what is assumed to be an appropriate way to teach and learn (i.e. the official curriculum and what society deems valuable and valued). The second dimension is ‘pedagogy as enacted’, which refers to how teachers and learners concretely embody the pedagogical act of teaching and learning. It is thus dependent on the enactors and their beliefs, conceptions, interpretations of policy, personal history, competences, etc. The third dimension is ‘pedagogy as experienced’, which refers to the actual impact of the enacted pedagogy on the various actors and their subjective experience of teaching and learning.

Nind’s team also provides guidance with regard to effective pedagogy. In their view, effective pedagogy equips learners for life in its broadest sense, engages with valued forms of knowledge, recognizes the importance of prior experience and learning, promotes the active engagement of the learner, fosters both individual and social processes and outcomes, recognizes the significance of informal learning, depends on the learning of all who support the learning of others, and demands consistent policy frameworks with support for learning as their primary focus (Lewthwaite and Nind Citation2015a).

In terms of process, effective PK takes into account normative documents (e.g. competency frameworks, curricula), socially-valued forms of teaching (e.g. project-based learning today, rote learning some decades ago) and learning that is actually enacted by individuals in situated contexts. In terms of content in research methods education, the works previously cited (i.e. Garner et al. Citation2009, Nind's team; Earley Citation2014) have contributed to orient research methods pedagogy in the twenty-first century.

Defining technological knowledge

As mentioned in the introduction, TK is defined in terms of deep and broad essential technological understanding. It refers to the capacity to develop digital literacy to the point of being able to apply technology productively and creatively (Koehler et al. Citation2013). As a reminder, the etymology of the term ‘technology’ comes from the ancient Greek techne, meaning ‘art, skill, craft’ (Lancaster Citation2021).

First, technology is presented as supporting the researcher’s work. TK is multidimensional and covers different levels of expertise and knowledge in research methods education. TK supports researchers in their documentary and data collection work (Van der Maren Citation2019) through data mining software and search engines. TK enhances researchers’ data analysis and interpretation – one of the core professional activity of researchers (e.g. Schmieder Citation2019, Silver and Woolf Citation2015, Kalpokaite and Radivojevic Citation2020). TK enables access to research data shared according to the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) standards on open archives (e.g. Koers Citation2020). TK provides opportunities to creatively use non-specialized technology for the purposes of research methods education – for instance, using the wiki technology to create and publish a participatory and co-created textbook (e.g. Class and Schneider Citationn.d.). Finally, TK enhances understandings of broader digital literacy (e.g. the capacity to work with artificial intelligence), which certainly can help if it is well understood and mastered (de la Higuera and Iyer Citation2023). In teaching research methods, the different ways in which technology is used by researchers need to be adapted for teaching.

Second, technology is highlighted as a revealing indicator of social processes and realities. In its revealing role, TK acts as an eye-opener on current practices, both the ones that are positive, i.e. how research methods education functions and the ones that are maybe more challenging, i.e. how research methods education dys-functions and is broken.Footnote15 Indeed, when technology is introduced into a practice, it is usually done gradually (e.g. Eduvista Citation2018, Tondeur Citation2021, Sackstein et al. Citation2023). It begins with the imitation of the same gestures of existing practices, but with different media (e.g. coding with highlighters and in a CAQDAS software) and gradually moves on to explore new possibilities. The philosophical underpinnings of the practice though are taken for granted, go unquestioned, and are simply transferred to the new technological stage or to the digital world. The transition from a face-to-face to a digital practice, or from one technological stage to another, is thus seen as a key revealing moment of those philosophical underpinnings which are taken for granted. As a corollary, it is the essence of the praxis that is unveiled in these transitional moments. In this sense, technology is said to be an eye-opener and a revealing indicator. It offers the opportunity to gain access to the philosophical foundations and to question them. In the future, for example, artificial intelligence that will be used to teach research methods will need to be carefully vetted, with algorithms and data sets made fully transparent, to avoid the pitfalls that are reported in the documentary Coded biasFootnote16 for instance and by organizations (e.g. OECD Citation2022, UNESCO Citation2023).

Finally, there are drawbacks or pitfalls to TK, which can be summarized under the term technodolatry (in reference to St Pierre’s methodolatry). With methodolatry, St. Pierre (Citation2019, p. 11) reminds us that methodology needs to be seen as a building block in a philosophical ensemble. Methodolatry refers to what ‘the feminist Mary Daly, in 1973, called the worship of method, the belief in the necessity of method, the uncritical application of a methodology regardless of its misalignment with the onto-epistemology of the study’ (St. Pierre Citation2019, p. 11). Using the term technodolatry in research methods education, the scholar points to the need to consider technology as a building block in the same overall philosophical ensemble of the study. Technodolatry thus can be understood in the present context as the worship of any technology and the uncritical application of technology regardless of its historical philosophical baggage. Savin-Baden (Citation2022a) for example warns against the simplified use of technology and mentions specifically hollow analysis; unsophisticated charts that look pretty but do not offer any in-depth explanations; cleaning data and hiding themes; using statistical software suites; and ignoring subtexts.

To conclude this section, technology is to be considered as a pharmakon: it can act as a medicine but also as a poison (Mboa Nkoudou Citation2020). It can be very helpful to support researchers’ and teachers’ activities but it can also be very misleading. It is scholars’ responsibility to make it a medicine.

Defining pedagogical content knowledge

As stated in the literature review, PCK consists of generic and specific knowledge enacted within certain approaches, strategies, tactics and tasks (Lewthwaite Citation2019, Nind and Lewthwaite Citation2020, Nind Citation2020). To further illustrate PCK, research writing is examined. Badenhorst (Citation2023, pp. 149–150) explains her pedagogical approach to research writing, which draws on: (i) threshold concepts from doctoral education (i.e. those mentioned in the content knowledge section); (ii) research pedagogy (i.e. conceptualizing a research project, situating it within the research literature, developing critical skills and taking a stance, developing problem/purpose statements and the importance of evidence and validity of data in developing arguments, the idea of research writing as a threshold concept and of writing differently depending on the type of research being conducted); and (iii) writing studies (i.e. the social nature of writing, the fluid nature of genres, writing as development, the importance of writing identities, how habits can become fixed and entrenched and how all writers need to continually learn). She then explains the conceptual framework on which the course is based, i.e. Beaufort (Citation2007). Finally, ‘pedagogy as experienced’ shows that the prioritization of the type of knowledge most valued by the group of students who participated in the study resulted in the following categorization: emotional intelligence, self-awareness as a writer, knowledge of the writing process, knowledge of the discourse community, rhetorical knowledge, genre knowledge and, finally, subject knowledge (Badenhorst Citation2023, p. 161).

Defining technological pedagogical knowledge

TPK, understood as the way a particular technology can change teaching and learning, recalls the media debate of the 1990s between Clark and Kozma (Kozma Citation1994, Clark Citation1994). Clark argued that technology was simply a ‘conduit’ for pedagogy, while Kozma held that technology has pedagogical implications, and that teachers must therefore take care in their choice of appropriate technologies. TPK seeks to understand the different affordances of technology and how to leverage them for teaching and learning (Koehler et al. Citation2013). TPK is thus about the impact of technology on teaching and learning research methods. Its core concern is how to create and integrate the affordances of technology to support the teaching and learning of research methodology.

In this context, stakeholders need to consider the continuum and entanglements between technology and human cognition. In research methods education, one example of TPK is the use of open research data archives for teaching and learning. An important issue to consider, therefore, is how the pedagogical scenario of a course integrates access to Open Research Data. For example, might a backward engineering process be used, in which a first activity might consist of working back from a given dataset to imagine a data collection method and an initial research question? Could a second activity consist of analysing this data through the lens of the chosen research question and providing a backed-with-data answer? And so on.

Defining technological content knowledge

TCK describes how the use of a given technology influences and impacts the content, knowledge and practice of a certain teaching-learning domain (Koehler et al. Citation2013). It involves (1) selecting appropriate technology according to its affordances for the domain; (2) using technology in the process of teaching and learning; and, (3) conducting research to evaluate its impact. In research methods education, TCK could include notions related to the Internet / World Wide Web (CERN Citationn.d.) and previous traditions of exchanging among scholars (Langlais Citation2015). Indeed, it is through mobility (Sheller Citation2018) and the Internet that different parts of the world that were previously kept apart can open up, forging international connections and raising awareness about the variety of realities and knowledges (UNESCO Citation2021). In this perspective, TCK in research methods’ core concern is to create and integrate the affordances of technology to make a plurality of sciences possible (de Sousa Santos and Meneses Citation2020, St. Pierre Citation2006).

Defining technological pedagogical content knowledge

TPACK is more than the sum of its components; rather, it implies a new, integrated knowledge. TPACK offers an opportunity to align the different individual and intersectional types of knowledge in a coherent whole. TPACK extends the epistemological understanding of a given field and allows it to reorient, strengthen or create new epistemologies (Koehler et al. Citation2013). Expanding the epistemological, ontological and axiological understandings in the field of research methods education is key at this moment in the history of education sciences (e.g. Tesar Citation2022). Indeed, as teachers and researchers of research methods, it is important to be properly equipped, i.e. to be fully aware of the breadth and depth of philosophical knowledge, in order to be able to train new scholars in full transparency.

The TPACK framework can be used in research methods education to help bridge disparate knowledge types. Establishing an initial understanding of each type of individual and overlapping knowledge and visually representing them all on the same map () is a step towards raising awareness of their interconnectedness and how one type of knowledge can be leveraged over the other in a coherent philosophical ensemble.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, the scholar used a SoTL approach to suggest the use of a TPACK framework for the teaching of research methods in education. Its initial aim was to advance the discussion started 10 years ago on the pedagogy of research methods in the social sciences and particularly Nind (Citation2020)’s more recent work on PCK. It was felt important to add technology to this discussion and indeed, it was.

As a reminder, technological knowledge (TK) refers to the ability to develop digital literacy to the point where technology can be used productively and creatively, and is defined in terms of deep and broad essential technological understanding (Koehler et al. Citation2013). In relation to research methods education, technology was presented as fulfilling three roles: firstly, it supports the work of the researcher, and by extension, the work of the research methods teacher; secondly, it highlights social processes and realities; and thirdly, it can act as a medicine or a poison.

Building on the second role, through this writing, technology has emerged as a revealing indicator of the praxis of research methods education. To further illustrate this claim, consider ‘coding’ in qualitative research as a data analysis research method. First, coding was done with paper and pencil, then it was transferred to CAQDAS. And now it is about to use some kind of generative artificial intelligence based on these past practices, pushing the technology-enhanced practice to further support the method. Despite these technological changes, the onto-epistemology behind coding has never been questioned in mainstream RME. Founding her argumentation on Deleuze and Guattari, St. Pierre (Citation2019, p. 6), however, shows how coding can or cannot be used depending on the onto-epistemology in which the study is conducted. She takes the example of an ontology of immanence where coding makes no sense. Coding falls into a binary ontology of transcendence, which is present in a certain interpretation of positivism. Scholars should therefore have a firm grasp of the onto-epistemological underpinnings of their study before deciding whether to use coding. However, this process is rarely undertaken and even more rarely documented.

The reflections on PCK and TK show that it is now at the level of content knowledge (CK) that more attention needs to be paid to teaching research methods. This is consistent with the findings and reflections of other researchers (e.g. Nind Citation2023, Albero and Thievenaz Citation2022, Tesar Citation2022, Hameline Citation1979, St. Pierre Citation2006, Savin-Baden Citation2022a). Similarly, an awareness of the fact that a research method is not neutral and a critical examination of the background to research methods are of paramount importance. Rethinking the content taught in research methods education with a critical mindset seems timely. It is proposed to reflect on and discuss the ontological, axiological and epistemological foundations of research methods, i.e. their overall philosophical underpinnings, but also to include the different knowledge systems (e.g. Piron and Arsenault Citation2021). It is desirable to make these diverse knowledge production systems accessible, transparent and understandable to new scholars to complement the existing and yet to emerge philosophies of the Global North. Indeed, along with philosophical basements of RME that have been invisibilised, the exclusive focus on the Global North has invisibilised philosophies, pedagogies, social theories, etc. from the Global South (e.g. Akkari and Fuentes Citation2021, Cakata et al. Citation2023). This has now been made clear and can be thought of in a different way. In RME, to advance the post-inquiry, the not yet there and a creative and responsible use of technology, re-sourcing in the world’s philosophical heritage seems to be a good compromise.

To conclude, the proposed use of the TPACK framework for research methods education () provides an example of all the different types of knowledge that a research methods teacher should master in the domain of education (e.g. Van der Maren Citation2019, Mialaret Citation2016). As explained in the section Who is the researcher and what are her worldviews, it is the fruit of being in a liminal space, halfway between the RME associated with the industrial society, oriented towards reproduction, and RME in the knowledge society with a focus on creation (Innerarity Citation2015).

The proposed use of the TPACK framework for RME offers an opportunity to think about the role of research methods in shaping the domain of education. As previously mentioned, education is shaped by discourse and action, i.e. research and practice. RME is a special nexus in this relationship because its aim is the training of future scholars who, in turn, will advance the field of education through their research praxis. It was already underlined how philosophy has been replaced by evidence-based research in education leading to ‘scientism’ (St. Pierre Citation2006, Laot and Rogers Citation2015, Hameline Citation1979). This crying need for philosophical ‘re-sourcing’ (Adler Citation2000) is reinforced by the recent call of a collective of scholars to reconsider the place of philosophy in the domain of education. Scholars specifically call for genuine partnerships worldwide in the exploration of ‘indigenous ethico-onto-epistemologies’ (Tesar Citation2022, p. 1235). This is where epistemologies of the South (e.g. de Sousa Santos Citation2014, de Sousa Santos and Meneses Citation2020) and Open Science’s recommendations (UNESCO Citation2021) to consider open dialogue with other knowledge systems and open engagement of societal actors can be seen as a game changer. The visibility and full transparency of processes (e.g. the underlying philosophies of any research method) seems important for the documentation of RME itself.

The proposition of the TPACK framework for RME, which is only one suggestion among many other possibilities, raises awareness of potential needs for professional development. It could encourage other scholars to suggest the use of the TPACK framework at a finer granularity, e.g. to teach qualitative or post-digital research method in given philosophies. Finally, it could encourage other scholars to create frameworks that can make the diversity of RME accessible, transparent and consistent with research needed in the emerging knowledge society.

Data deposition

For this research project, data is available from YARETA, https://yareta.unige.ch/home/detail/0a9383ea-850e-4998-90c0-088df8bfc318.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Research methods education in the social sciences represents the domain to which this article adds a contribution. To avoid repeating it, we abbreviate it to RME.

2 Praxis is meant here in the Freirian sense, i.e. reflection and action intertwined. This idea is also present in Phillips (Citation2017) with knowledge described as a continuum from episteme to phronesis.

3 The debate focused on the role of technology and the main question was to find out whether technology has to be considered as a mere vehicle or if it has a pedagogical impact.

5 We refer here altogether to epistemologies that have been around for some years, e.g. postmodernism, as well as newer ones like postdigital which, since 2021 offer a book series dedicated to the topic, https://www.springer.com/series/16439

6 Research methods education is itself informed by discourse and action and thus also takes the form of a praxis.

7 ECTS stands for European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System. “ECTS credits represent learning based on defined learning outcomes and their associated workload”; it makes courses more transparent and helps students to move between countries pertaining to the European Higher Education Area. 1 ECTS is equivalent to 25 student working hours. https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/higher-education-initiatives/inclusive-and-connected-higher-education/european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system

8 Blended in the sense of upfront techno-pedagogical design: one face-to-face week alternating with four weeks of on-line work.

11 Early cycles focused on (mis)conceptions of research using Meyer et al. (Citation2005)’s inventory (Class Citation2016, Class Citation2017). It appeared that for the 8 new scholars participating in the research, previous experience with research would lead to consolidation and/or correction of pre-existing knowledge, an encounter with threshold concepts and a non-linear learning path - plateau, doubt, fall. On the other hand, the absence of previous experience would lead to an exclusively upwards learning path, focused on the discovery of new elements of knowledge and ignoring threshold concepts. More recent cycles (Class and Akkari Citation2021) focused on decision-makers' opinion on RME within the specific international training RESET-Francophone. In addition to underlining that research topics in the Global South are most of the time “imported”, this training is considered a "third way" beside the European doctorate and the North American PhD. Activities take new scholars through the different steps of the research cycle and require them to reflect on philosophical aspects that are seldom addressed with their advisors and doctoral schools. Furthermore, more recent cycles of the DBR also focused on the techno-pedagogical design of learning environments for RME (Class Citation2020b), on the importance of moving away from “institutional positivism” (Piron Citation2019) for social sciences’ researchers (Class et al. Citation2021) and on the importance to make the foundations of education visible (Class Citation2022b).

12 This data is part of the SNSF project entitled Open Education for Research Methodology Teaching across the Mediterranean and can be accessed on-line.

13 For instance, with regard to qualitative research, a wide range of perspectives co-exist (e.g. Aspers and Corte Citation2019, Brinkmann et al. Citation2014).

14 There is a crying need for philosophical foundations to be re-introduced in research methods education (e.g. Tesar Citation2022, Given Citation2008, St. Pierre Citation2006).

15 In reference to Jhangiani (Citation2017): “the opposite of open is not closed; the opposite of open is broken”. Talking of science, it is a term he uses to highlight the perversions of the system, such as paying for access to articles written, peer-reviewed and published by academics paid with public funds, and the need to restore good practice.

17 In two words, pastoral power is the power that, in the 18th century went out of churches into the state and society and imposed a new form of power from the state and a "new type of individualization which is linked to the state" (Foucault Citation1982, p. 785).

18 The various studies to which reference is made are those mentioned in the first paragraph of the current Method section. Some of them are part of the SNSF project “Open Education for Research Methodology Teaching across the Mediterranean”.

19 The different scenarii, year after year since 2014 are available in French from https://tecfa.unige.ch/perso/class/ScenarioDetailles2014-2020/

References

- Adler, J., 2000. Conceptualising resources as a theme for teacher education. Journal of mathematics teacher education, 3 (3), 205–224. doi:10.1023/A:1009903206236.

- Akkari, A., and Fuentes, M. 2021. Repenser l’éducation: alternatives pédagogiques du Sud. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377797.

- Albero, B., and Thievenaz, J. 2022. Traité de méthodologie de la recherche en Sciences de l'éducation et de la formation. Éditions Raison et Passions.

- Amin, T., and Levrini, O., 2018. Converging pserspectives on conceptual change: mapping an emerging paradigm in the learning sciences. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Aspers, P., and Corte, U., 2019. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qualitative sociology, 42 (2), 139–160. doi:10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7.

- Badenhorst, C., 2023. Bridging the unknown. Threshold concepts in doctoral research writing. In: L. Buckingham, J. Dong, and F. Jiang, eds. Interdisciplinary practices in academia: Writing, teaching and assessment. Routledge, 1st ed., 147–166. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003263067-11

- Ball, J., and Savin-Baden, M., 2022. Postdigital learning for a changing higher education. Postdigital science and education, 4 (3), 753–771. doi:10.1007/s42438-022-00307-2.

- Beaufort, A., 2007. College writing and beyond: a new framework for university writing instruction. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

- Bedin, V., and Franc, S., 2019. Introduction générale. In: V. Bedin, S. Franc, and D. Guy, eds. Les sciences de l'éducation: pour quoi faire?: entre action et connaissance. Paris: L'Harmattan, 21–37.

- Bedin, V., Franc, S., and Guy, D., (Eds.). 2019. Les sciences de l'éducation: pour quoi faire?: entre action et connaissance. In Pratiques en formation. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Bengry-Howell, A., et al., 2011. A review of the academic impact of three methodological innovations: netnography, child-led research and creative research methods. ESRC national centre for research methods. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/1844/

- Boyer, E., 1990. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Princeton NJ: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Brew, A., 2001. Conceptions of research: a phenomenographic study. Studies in higher education, 26 (3), 271–285. doi:10.1080/03075070120076255.

- Brinkmann, S., Jacobsen, M.H., and Kristiansen, S., 2014. Historical overview of qualitative research in the social sciences. In: P Leavy, ed. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 17–42.

- Cakata, Z., Radebe, N., and Ramose, M. 2023. Azibuye emasisweni. Reclaiming our space and centring our knowledge.

- Carr, W., and Kemmis, S., 1986. Becoming critical: education, knowledge and action research. Lewes: Falmer.

- CERN., n.d. The birth of the Web. https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web.

- Charmillot, M. 2020. Définir une posture de recherche. Université de Genève.

- Chatterjee-Padmanabhan, M., and Nielsen, W., 2018. Preparing to cross the research proposal threshold: A case study of two international doctoral students. Innovations in education and teaching international, 55 (4), 417–424. doi:10.1080/14703297.2016.1251331.

- Chatterjee-Padmanabhan, M., Nielsen, W., and Sanders, S., 2019. Joining the research conversation: threshold concepts embedded in the literature review. Higher education research & development, 38 (3), 494–507. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1545747.

- Chevallard, Y., 1991. La transposition didactique. Du savoir savant au savoir enseigné. 2nd ed. Grenoble: La Pensée sauvage.

- Clark, R., 1994. Media will never influence learning. Educational technology research and development, 42 (2), 21–29.

- Class, B., et al., 2016. Enseigner la méthodologie de la recherche en technologie éducative: des conceptions aux concepts seuils. Distances et médiations des savoirs, 13, 2–17. doi:10.4000/dms.1349.

- Class, B., et al., 2017. Pistes réflexives sur l’apprentissage de la méthodologie de la recherche en technologie éducative. Frantice.net Numéro spécial, 12-13, 149–174.

- Class, B., 2020a. Enhancing knowledge and practice: research competences of a distance learning coordinator. In: J Theo Bastiaens, ed. Edmedia + innovate learning. Netherlands: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), 1198–1212.

- Class, B., 2020b. Features for an international learning environment in research education. Paper presented at the international conference on computer supported education.

- Class, B.M.d.B., et al., 2021. Towards open science for the qualitative researcher: from a positivist to an open interpretation. International journal of qualitative methods, 20. doi:10.1177/16094069211034641.

- Class, B., et al., 2021. Towards open science for the qualitative researcher: from a positivist to an open interpretation. International journal of qualitative methods, 20, doi:10.1177/16094069211034641.

- Class, B., 2022a. Open education: towards epistemic sustainability. In: Mutlu Cukurova, Nikol Rummel, Denis Gillet, Bruce McLaren, and James Uhomoibhi, eds. International conference on computer supported education. Springer, 646–653.

- Class, B., 2022b. Revisiting education: On the role of imagination, intuition and other “gifts” for open scholars. Frontiers in education, 7, doi:10.3389/feduc.2022.846882.

- Class, B., and Akkari, A., 2021. Le projet RESET-francophone: vers une formation ouverte et libre à la méthodologie de la recherche en éducation. L’éducation en débats: analyse comparée, 10 (2), 192–217. doi:10.51186/journals/ed.2020.10-2.e346.

- Class, B., and Schneider, D., n.d. Manuel de recherche en technologie éducative. http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/fr/Manuel_de_recherche_en_technologie_%C3%A9ducative.

- Class, B., and Schneider, D., 2019. La ressource: de la réforme de Bologne à l’ingénierie pédagogique. Paper presented at the Ludovia.ch, Yverdon-les-bains.

- Class, B, B Schneider, R Canal, and M Laroussi. 2014. A project for transitional education of doctoral applicants in educational technology. Paper presented at the Ed media - world conference on educational multimedia, hypermedia and telecommunications, Tampere, Finland, 23-26 June 2014.

- Collins, D., 2019. The NCRM quick start guide to: teaching social research methods online. National centre for research methods. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4246/1/Quick-start-guide-teaching-online.pdf

- Collins, A., Joseph, D., and Bielaczyc, K., 2004. Design research: theoretical and methodological issues. Journal of the learning sciences, 13 (1), 15–42. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls1301_2.

- Cooper, H., 1998. Synthesizing research: a guide for literature reviews. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Deimann, M., 2019. Openness. In: Insung Jung, ed. Open and distance education theory revisited: implications for the digital era. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 39–46.

- de la Higuera, C., and Iyer, J. 2023. AI for Teachers, An Open Textbook.

- Descarpentries, J. 2021. Les Épistémologies du Sud à Paris 8 UAES. https://hal.science/hal-03896929/.

- Descarpentries, J., and Charmillot, M. 2022. Théories critiques et épistémologies du Sud. https://education.cuso.ch/?id = 902&L = 0&tx_displaycontroller[showUid] = 6140.

- de Sousa Santos, B., 2014. Epistemologies of the south: justice against Epistemicide. London & New York: Routledge.

- de Sousa Santos, B., 2016. Epistémologies du Sud : mouvements citoyens et polémique sur la science. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer.

- de Sousa Santos, B., and Meneses, M.P., 2020. Epistemologies of the south. Knowledge born in the struggle. Constructing the epistemologies of the global south. New York: Routledge.

- Earley, M., 2014. A synthesis of the literature on research methods education. Teaching in higher education, 19 (3), 242–253. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.860105.

- Eduvista. 2018. Innovation Maturity Model. Accessed 25 mai. http://files.eun.org/fcl/eduvista/eduvista-tool-2p1.pdf.

- Escaño, C., and Mañero, J., 2022. Postdigital intercreative pedagogies: ecopedagogical practices for the commons. In: Petar Jandrić, and Derek R. Ford, eds. Postdigital ecopedagogies: genealogies, contradictions, and possible futures. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 231–246.

- Evans, R., 2007. Comments on shulman, golde, bueschel, and garabedian: existing practice is not the template. Educational researcher, 36 (9), 553–559. doi:10.3102/0013189(07313149.

- Foucault, M., 1982. The subject and power. Critical inquiry, 8 (4), 777–795.

- Freire, P., 1994. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Galliers, R., and Huang, J.S., 2012. The teaching of qualitative research methods in information systems: an explorative study utilizing learning theory. European journal of information systems, 21, 119–134. doi:10.1057/ejis.2011.4.

- Garner, M., Wagner, M., and Kawulich, B., 2009. Teaching research methods in the social sciences. London: Routledge.

- Giri, A.K., 2021. With and beyond epistemologies from the south: ontological epistemology of participation, multi-topial hermeneutics and the calling of planetary realisations. Sociological bulletin, 70 (3), 366–383. doi:10.1177/00380229211014666.

- Given, L., 2008. Positivism. In The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909

- Guibert, P. 2021. Manuel de sciences de l'éducation et de la formation. Louvain la Neuve: Louvain-la-Neuve De Boeck Supérieur.

- Haigh, N., and Withell, A., 2020. The place of research paradigms in SoTL practice: an inquiry. Teaching & learning inquiry, 8 (2), 17–31. doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.8.2.3.

- Hameline, D., 1979. Le sujet de l'éducation. Paris: Beauchesne.

- Hayes, D., 2007. What Einstein can teach us about education. Education 3-13, 35 (2), 143–154. doi:10.1080/03004270701311986.

- Herring, M.C., Koehler, M.J., and Mishra, P., 2016. Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators. New York & London: Routledge.

- Herrington, J., Reeves, T., and Oliver, R., 2014. Authentic learning environments. In: M Spector, D Merrill, J Elen, and M Bishop, eds. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. New York: Springer Science, 401–412.

- Hofstetter, R., and Schneuwly, B., 2001. L’avènement d’un nouveau champ disciplinaire. Ressorts de l’universitarisation des sciences de l’éducation à Genève, 1890-1930. In: R Hofstetter, and B Schneuwly, eds. Le pari des sciences de l’éducation. Bruxelles: de Boeck, 79–115.

- Hofstetter, R., and Schneuwly, B., 2002. Institutionalisation of educational sciences and the dynamics of their development. European educational research journal, 1 (1), 3–26. doi:10.2304/eerj.2002.1.1.9.

- Honebein, P.C., and Reigeluth, C.M., 2021. To prove or improve, that is the question: the resurgence of comparative, confounded research between 2010 and 2019. Educational technology research and development, 69 (2), 465–496. doi:10.1007/s11423-021-09988-1.

- Hubball, H., and Clarke, A., 2010. Diverse methodological approaches and considerations for SoTL in higher education. The Canadian journal for the scholarship of teaching and learning, 1 (1), doi:10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2010.1.2.

- Hutchins, E., 1995. Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Innerarity, D., 2015. Chapitre 3. La société de la connaissance et l’ignorance. In Innerarity, Daniel, ed. Démocratie et société de la connaissance. FONTAINE: Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 47–65.

- Jhangiani, R.S., 2017. Open as default. The future of education and scholarship. In: Rajiv S. Jhangiani, and Robert Biswas-Diener, eds. Open. The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science. Ubiquity Press, 267–280. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3t5qh3.5

- Jonassen, D., 1984. The mediation of experience and educational technology: a philosophical analysis. Educational communication and technology journal, 32 (3), 153–167.

- Jonassen, D.H., 1991. Objectivism versus constructivism: do we need a new philosophical paradigm? Educational technology research and development, 39 (3), 5–14. doi:10.1007/BF02296434.

- Jonassen, D., Campbell, J., and Davidson, M., 1994. Learning with media: restructuring the debate. Educational technology research and development, 42 (2), 31–39.

- Jonassen, D., and Land, S., 2012. Theoretical foundations of learning environments. 2nd ed. New York & London: Routledge.

- Kalpokaite, N., and Radivojevic, I., 2020. Teaching qualitative data analysis software online: a comparison of face-to-face and e-learning ATLAS.ti courses. International journal of research & method in education, 43 (3), 296–310. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1687666.

- Keefer, J.M., 2015. Experiencing doctoral liminality as a conceptual threshold and how supervisors can use it. Innovations in education and teaching international, 52 (1), 17–28. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.981839.

- Kemmis, S., and Edwards-Groves, C., 2018. Education, practice, and practice architectures. In: Kemmis, Stephen and Edwards-Groves, Christine, eds. Understanding education: history, politics and practice. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 115–158.

- Kilburn, D., Nind, M., and Wiles, R., 2014. Learning as researchers and teachers: the development of a pedagogical culture for social science research methods? British journal of educational studies, 62 (2), 191–207. doi:10.1080/00071005.2014.918576.

- Kiley, M., 2015. 'I didn't have a clue what they were talking about': PhD candidates and theory. Innovations in education and teaching international, 52 (1), 52–63. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.981835.

- Kiley, M., 2019. Threshold concepts of research in teaching scientific thinking. In: M Murtonen, and K Balloo, eds. Redefining scientific thinking for higher education. higher-order thinking, evidence-based reasoning and research skills. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 139–155.

- Kiley, M., and Wisker, G., 2009. Threshold concepts in research education and evidence of threshold crossing. Higher education research & development, 28 (4), 431–441. doi:10.1080/07294360903067930.

- Koehler, M.J., and Mishra, P., 2005. What happens when teachers design educational technology? The development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of educational computing research, 32 (2), 131–152. doi:10.2190/0ew7-01wb-bkhl-qdyv.

- Koehler, M.J., Mishra, P., and Cain, W., 2013. What Is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? The journal of education, 193 (3), 13–19.

- Koers, H., et al., 2020. Recommendations for services in a FAIR data ecosystem. Patterns, 1 (5), 100058. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2020.100058.

- Kozma, R., 1994. Will media influence learning? reframing the debate. Educational technology research and development, 42 (2), 7–19.

- Lagemann, E., 2000. An elusive science: the troubling history of education research. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Lancaster, L. 2021. Technology. Oxford University Press.

- Langlais, P.-C., 2015. Quand les articles scientifiques ont-ils cessé d’être des communs? Sciences communes. On-line: https://scoms.hypotheses.org/409

- Laot, F., and Rogers, R., 2015. Question éducative et recherche dans l'après Seconde Guerre mondiale. In: F Laot, and R Rogers, eds. Les Sciences de l'éducation. Emergence d'un champ de recherche dans l'après-guerre. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 7–24.

- Lather, P., and St. Pierre, E.A., 2007. Postpositivist new paradigm inquiry. In: P Lather, ed. Getting lost: feminist efforts toward a double(d) science. Albany: State University of New York Press, 164.

- Lave, J., and Wenger, E., 1991. Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

- Lewthwaite, S., et al. 2019. Developing pedagogy for ‘Big Qual’ methods: Teaching how to analyse large volumes of secondary qualitative data. National Centre for Research Methods.

- Lewthwaite, S., and Nind, M., 2015a. The NCRM quick start guide to: principles for effective pedagogy. National centre for research methods. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/3766/

- Lewthwaite, S., and Nind, M., 2015b. Pedagogy in context: international experts’ insights into the teaching of advanced research methods. Society for research in higher education annual conference, United Kingdom.

- Lewthwaite, S., and Nind, M., 2016. Teaching research methods in the social sciences: expert perspectives on pedagogy and practice. British journal of educational studies in continuing education, 64 (4), 413–430. doi:10.1080/00071005.2016.1197882.

- Mboa Nkoudou, T.H., 2020. Epistemic alienation in African scholarly communications: open access as a pharmakon. In: Martin Paul Eve, and Jonathan Gray, eds. Reassembling scholarly communications: histories, infrastructures, and global politics of open access. The MIT Press, 25–40.

- McKenna, S., 2017. Crossing conceptual thresholds in doctoral communities. Innovations in education and teaching international, 54 (5), 458–466. doi:10.1080/14703297.2016.1155471.

- McKenney, S., and Reeves, T., 2019. Conducting educational design research. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Meyer, J., and Land, R., 2003. Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. In: ETL project. Coventry and Durham: University of Edinburgh, 1–2. http://www.etl.tla.ed.ac.uk//docs/ETLreport4.pdf

- Meyer, J., Land, R., and Baillie, C., 2010. Threshold concepts and transformational learning. In: Michael A. Peters, ed. Educational futures: rethinking theory and practice. Vol. 42. Rotterdam, Boston, Taipei: Sense Publishers.

- Meyer, C., Shanahan, J., and Laugksch, R., 2005. Students’ conceptions of research. I: a qualitative and quantitative analysis. Scandinavian journal of educational, 49 (3), 225–244.

- Mialaret, G., 2016. Les origines et l’évolution des sciences de l’éducation en pays francophones. Les Sciences de l'éducation - Pour l'Ère nouvelle, 49 (3), 53–69. doi:10.3917/lsdle.493.0053.

- Miller-Young, J., and Yeo, M., 2015. Conceptualizing and communicating SoTL: a framework for the field. Teaching & learning inquiry: The ISSOTL journal, 3 (2), 37–53. doi:10.2979/teachlearninqu.3.2.37.

- Mishra, P., 2019. Considering contextual knowledge: the TPACK diagram gets an upgrade. Journal of digital learning in teacher education, 35 (2), 76–78. doi:10.1080/21532974.2019.1588611.

- Mishra, P., and Koehler, M., 2006. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers college record, 108 (6), 1017–1054.

- Nicola-Richmond, K., et al., 2018. Threshold concepts in higher education: a synthesis of the literature relating to measurement of threshold crossing. Higher education research & development, 37 (1), 101–114. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1339181.

- Nind, M., 2009. Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: methodological challenges. ESRC national centre for research methods NCRM/, 012.

- Nind, M., et al., 2013. Risk, creativity and ethics: dimensions of innovation in qualitative social science research methods. Brtish educational research association annual conference, United Kingdom.

- Nind, M., et al., 2019. Student perspectives on learning research methods in the social sciences. Teaching in higher education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1592150.

- Nind, M., 2020. A new application for the concept of pedagogical content knowledge: teaching advanced social science research methods. Oxford review of education, 46 (2), 185–201. doi:10.1080/03054985.2019.1644996.

- Nind, M. 2023. Handbook of teaching and learning social research methods. Elgar.

- Nind, M., Curtin, A., and Hall, K., 2016. Research methods for pedagogy. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nind, M., and Katramadou, A., 2022. Lessons for teaching social science research methods in higher education: synthesis of the literature 2014-2020. British journal of educational studies, 1–26. doi:10.1080/00071005.2022.2092066.

- Nind, M., Kilburn, D., and Wiles, R., 2015. Using video and dialogue to generate pedagogic knowledge: teachers, learners and researchers reflecting together on the pedagogy of social research methods. International journal of social research methodology, 18 (5), 561–576. doi:10.1080/13645579.2015.1062628.

- Nind, M., and Lewthwaite, S., 2018a. Methods that teach: developing pedagogic research methods, developing pedagogy. International journal of research & method in education and information technologies, 41 (4), 398–410. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2018.1427057.

- Nind, M., and Lewthwaite, S., 2018b. Hard to teach: inclusive pedagogy in social science research methods education. International journal of inclusive education, 22 (1), 74–88. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1355413.

- Nind, M., and Lewthwaite, S., 2020. A conceptual-empirical typology of social science research methods pedagogy. Research papers in education, 35 (4), 467–487. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1601756.

- Nind, M., and Vinha, H., 2016. Creative interactions with data: using visual and metaphorical devices in repeated focus groups. Qualitative research, 16 (1), 9–26. doi:10.1177/1468794114557993.

- OECD. 2022. OECD Framework for the Classification of AI systems. doi:10.1787/cb6d9eca-en.

- Peters, M.A., 2014. Openness and the intellectual commons. Open review of educational research, 1 (1), 1–7. doi:10.1080/23265507.2014.984975.

- Phillips, M., et al. 2017. Unpacking TPACK: reconsidering knowledge and context in teacher practice.

- Piron, F., 2019. L’amoralité du positivisme institutionnel. L'épistémologie du lien comme résistance. In: L Brière, M Lieutenant-Gosselin, and F Piron, eds. Et si la recherche scientifique ne pouvait pas être neutre? Éditions science et bien commun. https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/neutralite/

- Piron, F., and Arsenault, E. 2021. Guide décolonisé de formation à la recherche en sciences sociales et humaines. Éditions Science et bien commun.

- Reeves, T.C., and Lin, L., 2020. The research we have is not the research we need. Educational technology research and development, 68 (4), 1991–2001. doi:10.1007/s11423-020-09811-3.

- Sackstein, S., Matthee, M., and Weilbach, L., 2023. Theories and models employed to understand the Use of technology in education: a hermeneutic literature review. Education and information technologies, 28 (5), 5041–5081. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11345-5.

- Savin-Baden, M., 2022a. The death of data interpretation and throwing sheep in a postdigital age. Education ouverte et libre - open education, 1, 1. doi:10.52612/journals/eoloe.2022.e11.754.

- Savin-Baden, M., 2022b. Landscapes of postdigital theologies. In: Maggi Savin-Baden, and John Reader, eds. Postdigital theologies: technology, belief, and practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 3–19.

- Schäffer, B., and Lieder, F.R., 2023. Distributed interpretation – teaching reconstructive methods in the social sciences supported by artificial intelligence. Journal of research on technology in education, 55 (1), 111–124. doi:10.1080/15391523.2022.2148786.

- Schmieder, C., 2019. Qualitative data analysis software as a tool for teaching analytic practice: towards a theoretical framework for integrating QDAS into methods pedagogy. Qualitative research, 20 (5), 684–702. doi:10.1177/1468794119891846.

- Sheller, M., 2018. Mobility justice: the politics of movement in an age of extremes. London: Verso.

- Shulman, L.S., 1986. Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educational researcher, 15 (2), 4–14. doi:10.2307/1175860.

- Shulman, L., 1987. Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard educational review, 57 (1), 1–22.