ABSTRACT

In this methodological discussion, a critical and reflective account of the process and use of online photo-elicitation interviews is given. The role and importance of a well-structured pre-interview task are discussed with a working example aiming to capture physiotherapy students’ professional doctorate journey. It is argued that photo-elicitation techniques can increase active participation and enhance participants’ storytelling by encouraging the use of abstract thinking. This article also offers unique insights through the researcher’s reflective diary and direct quotes from the participants. Key considerations and practical recommendations are provided, such as the online application of photo-elicitation, the nature of the observed topic and working with and not alongside the pictures. Overall, this article is intended to further contribute to the literature on the evaluation and implementation of photo-elicitation techniques, especially in an online setting.

Introduction

Investigating the doctorate student journey

While there are relatively clear requirements to complete and achieve a doctorate degree qualification, the notion of doctorateness and a doctorate journey is less straightforward (Bitzer Citation2015). Similarly, the doctorate characteristics in research knowledge and skills have been extensively addressed in research before (Trafford and Leshem Citation2009), but the personal development and the doctoral journey itself have received significantly less attention. The doctoral journey was previously found to be emotionally and cognitively challenging, especially when students’ identities and beliefs are being questioned (Beech Citation2011, Leshem Citation2020). It is argued that doctorate students enter a passage into the unknown or a suspended state of partial understanding (Wisker et al. Citation2008), also known as the liminal zone (Ybema et al. Citation2011), with the potential for transformative learning at the other end. Entering the liminal space and challenging previous understanding of identity, self and the world often leads to a shift in students’ ontology and epistemology (Meyer and Land Citation2005).

In the case of taught doctorate programmes, like the one observed in this study, students may experience different liminal zones connected to their personal and professional identities (e.g. Who am I? What kind of professional do I want to be? What are my key values?), and their views of their profession (e.g. What is the main purpose/aim of my profession? How do I fit into my profession?). All of this is happening simultaneously with the introduction of new concepts and ideas, such as research philosophy, skill development and professional decision-making. These experiences and concepts are complex phenomena and can be hard to describe and capture with words. This led to the call for capturing richer narratives to describe the doctorate journey through the use of metaphors (Bitzer Citation2015). Consequently, research should consider moving away from the more traditional research methods in order to capture these metaphors and develop an in-depth understanding of the uncertainties and arch of doctorate student journeys (Bitzer and Vandenbergh Citation2014). Visual methodologies, such as photo-elicitation, could be a potential way forward.

Background and benefits of using photo-elicitation techniques

Visual methods are a collection of research tools used to understand the observed research phenomenon through photos, pictures and other visual representations (Glaw et al. Citation2017). One of these visual methods is photo-elicitation, using photographs and other visual mediums within an interview setting to generate a verbal discussion to capture the participants’ thoughts and lived experiences (Harper Citation2002). Furthermore, alongside the generated verbal data, photos and other visual images can be also used as standalone data or as a symbolic representation of the participant's thoughts, feelings, experiences and understanding (Richard and Lahman Citation2015). While the most widely used medium is photography, photo-elicitation can be also used with pictures, drawings, movies and other visual mediums (Harper Citation2002).

Several benefits of photo-elicitation techniques have been previously documented, such as fostering researcher-participant collaboration (Richard and Lahman Citation2015), promoting participant agency (Bates et al. Citation2017), enabling participants to formalize abstractions and generalization (Banks Citation2007), adding additional layers by evoking deep emotions, memories and ideas (Glaw et al. Citation2017), and support reflection and preparation for the study (Banks Citation2007). All these benefits can enhance the richness of the data by adding additional layers of meaning and arguably help to capture more details than other traditional data collection methods (Shaw Citation2021).

Photo-elicitation in higher education research

Photo-elicitation and other visual methodologies have been used for a long time in anthropology and sociology, and they are gaining popularity in other fields such as healthcare (Milasan Citation2022) and educational research (Torre and Murphy Citation2015). In educational settings, visual-elicitation techniques were often used with teachers to reflect on their professional philosophy and practice (Bessette and Paris Citation2020, Birello and Pujolà Citation2020, Pujolà and González Citation2022). However, studies using photo-elicitation with students in Higher Education research are currently limited: Bates et al. (Citation2019) used photo-elicitation to explore general student satisfaction, while Kahu and Picton (Citation2022) aimed to explore first-year student experiences through metaphors of life, university and learning. Both studies showed a promising application of photo-elicitation in their research as they were able to capture a rich dataset on subjective student experience which arguably could not have been captured in more traditional ways. These studies reinforce the call to explore more creative data collection methods in Higher Education in order to produce a high-quality, participant-driven dataset that can truly capture lived student experiences. Furthermore, we argue that due to the complexity of doctorate learning, photo-elicitation could also be a useful tool to enhance reflexivity, self-awareness and therefore, self-development.

Background on online data collection

Many photo-elicitation techniques are already semi-virtual, and they may be entirely reproducible online (Newman et al. Citation2021). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, collecting data online has become second nature for a lot of researchers and the use of online data collection methods has significantly increased (Newman et al. Citation2021). As a result, more researchers and research participants are familiar with the technology and software required to collect data on online platforms (Lobe et al. Citation2020, Roberts et al. Citation2021). Additionally, there was a spike in improvements and tweaks on these platforms to increase their functions (Lobe et al. Citation2020). Even though online data collection methods are quite similar to their offline counterparts, there are slight differences, such as a lack of physical connection between the researcher and participants or restricted access to read participants’ body language. They also require heightened awareness, reflexivity and sensitivity on the part of researchers regarding participants’ comfort levels, emotional reactions and comprehension of informed consent (Newman et al. Citation2021). These subtle differences can be important and should be considered when photo-elicitation techniques are being used and sensitive topics are being discussed.

The aim of this article

While photo-elicitation was previously described as a ‘promising and innovative tool’ in research methodology (Bates et al. Citation2017), there is a limited amount of pragmatic guidance or consensus on how this method should be used. Bates et al. (Citation2017) described a step-by-step approach using photo-elicitation interviews and provided an overview of key considerations. Another reflective account by Richard and Lahman (Citation2015) discussed the experiences of using photo-elicitation techniques from the researcher’s perspective. However, the online application of this method and participants’ experiences are currently not documented. Therefore, this paper aims to provide a critical account of the process and challenges of using online photo-elicitation techniques with additional reflective accounts from both the researcher and participants. For a working example, we are going to use our recent qualitative study which aimed to explore physiotherapy students’ professional doctorate journey.

Methodological considerations

The rationale for the use of online photo-elicitation techniques

Due to the earlier discussed nature of doctorate journeys, the research team was looking for a data collection method that allows the participants to engage in reflective practice prior to the interview and enable them to capture their thoughts in a creative and meaningful way. Photo-elicitation interviews can do both. Firstly, by asking participants to collect photos and other visual representations of their journey, their cognitive processes are started before the interview takes place. Secondly, photos and pictures can allow the participants to go beyond words and allow creative expressions of the complex and sometimes hard-to-define concepts (Glaw et al. Citation2017).

Design and methods

The study and data reported here is a representative of a larger research project that focused on physiotherapy doctorate students’ perception of their doctorate journey and professional development. The current paper focuses on a sample of 3 out of 16 students who were enrolled in the same Professional Doctorate programme. They were selected to represent and showcase the variety of metaphors and experiences encountered on a doctorate-level qualification. Alongside their chosen visual images, verbal discussions between the participant and the researcher will be also provided. Furthermore, the larger study also captured participants’ experience with the online photo-elicitation technique providing a unique insight into this methodology. These insights will also be presented.

Process of using online photo-elicitation techniques

Visual methodologies, such as photo-elicitation have been utilized previously in a variety of ways; however, a detailed description of the methodology and decision-making are often not included in the published studies and there is a lack of consistency in the conceptualization and articulation of how these methodologies being implemented (Lapenta et al. Citation2011). Like other studies, photo-elicitation studies should have a clear rationale for the chosen methodology including ontological and epistemological considerations and how the photos are being used throughout the study. Bates et al. (Citation2017) differentiated three distinct formats for photo-elicitation interviews: participant-driven (open), participant-driven (semi-structured) and researcher-driven (semi-structured/structured). For our study, we used the participant-driven, semi-structured format where a pre-interview task (see supplementary document) acted as a framework for the participants but did not provide any pre-determined photos or pictures to choose from.

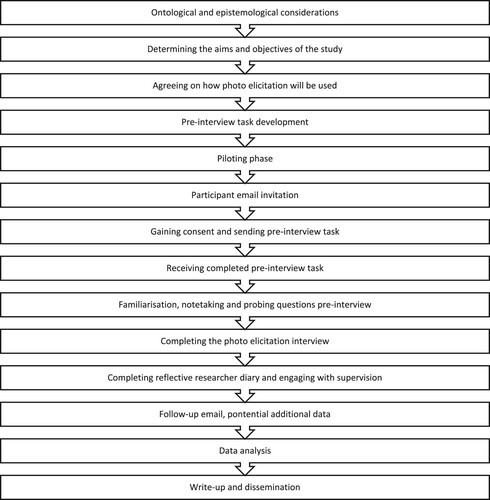

An overview of the study process is outlined in . Key methodological steps included ontological and epistemological considerations and determining the aims and objectives of the study. These initial steps helped to reflect on the research topic and the best way to explore the topic which is also aligned with our research philosophy. As a result, we agreed to implement visual data collection methods. The next step involved the development and piloting of the pre-interview task. The recruitment stage involved reaching out to all Doctorate students on the course by email via a gatekeeper. Students who were interested in the study then received an information sheet, consent form and the pre-loaded PowerPoint slides. Based on our experience, we recommend giving 7–14 days to participants to complete the pre-interview task and attend the interview. Anything less would not provide sufficient time to engage with the reflective nature of the pre-interview task, while anything more might cause participants to put off the task and not engage with it until immediately prior to the interview.

Participants were asked to return their completed slides at least 24 h before the interview, so the researchers could familiarize themselves, take notes and write tailored probing questions (e.g. probing topics and/or the presented pictures further matching the style of the completed pre-interview task), and get an initial feel for the data. This was an important step to ensure a good flow for the interview and allowed the researcher to actively collaborate with the participant. Our experience shows that both the participant and researcher have their unique interpretation of the chosen pictures and they might mean different things to both parties. Having an honest and open conversation about these different interpretations can further enhance thinking and interpretations during the interview and therefore increase the quality of the collected data. As previous studies highlighted, photo-elicitation interviews tend to have a different flow where the participants are more actively engaged and power dynamics are reduced (Glaw et al. Citation2017). In our study, interviews felt like an active listening task with facilitation, reflection and participation empowerment in mind.

Following the interview, the researcher immediately completed a reflexive diary intake and sent out a follow-up email to each participant thanking them for participation and encouraging them to add anything else if they felt needed. As the reflection process does not always stop at the end of the interview and participants might gain more and/or better clarity afterwards, encouraging them to share these additional thoughts can be a valuable addition to the dataset. Based on our experience, asking participants to share any additional thoughts within 24 h of the received email is sufficient to capture these potential after-thoughts and also makes the research process manageable in a timely manner.

The final steps included data analysis and the write-up of the study. Previous studies tend to differ in the type of analysis conducted when using visual elicitation techniques. While some studies only analysed the visual images (Shohel and Mahruf Citation2012), other studies combined the visual and verbal/written data (Comeaux Citation2013) to provide in-depth analysis and understanding of the observed phenomenon. For the current study, we decided to collate all visual images into a matrix diagram (participants/slides/pictures) to observe similarities and differences for each topic and between participants. For the interview analysis, we employed inductive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2021) which aimed to capture and reflect the participants’ experiences instead of the researcher’s interpretation of the chosen images.

Pre-interview task

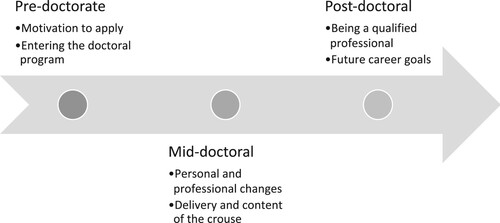

Prior to the online interview, we asked each participant to engage in a pre-interview task. We decided to use a pre-loaded PowerPoint template to provide a chronological guide for personal reflection and collect visual representations of participants’ thinking. This template included generic and purposefully broad instructions to encourage creativity and self-expression. The pre-interview task asked participants to collect any visual representations that described the key milestones of their doctorate journey (). These included:

Their motivation to attend the course

How they perceived themselves at entering the doctoral programme (year 2)

How they changed as a doctorate physiotherapist due to attending the course

How they perceived themselves at the end of the programme

Their thoughts regarding the delivery and/or content of the course

Optional: any other images which represent their view of the programme

Optional if already qualified: how they view themselves now

Optional: anything else they would like to discuss regarding the research topic

Interview process – encouraging ownership

Interviews took place on Microsoft Teams where the researcher shared her screen with the pre-interview task slides so both the researcher and the participant could see the chosen visuals. Each topic/slide was discussed by asking the participant first to tell their stories through the pictures they selected. Then, the researcher asked additional questions regarding the pictures and/or the topic. In this way, the participants remained unbiased and empowered to discuss any thought that came to their minds regarding their journey first, before the researcher probed specifics. As the covered topics can be quite complex, additional, pre-determined cues ensured that all relevant concepts were discussed that the participant might have not considered. For example, slide 3 asked participants how they have changed throughout the course which could include several cognitive and affective domains, such as identity, epistemic stance, confidence level and perception of physiotherapy as a profession. Before moving on to the next slides, participants were asked whether they would like to add anything else to what was discussed so far. This again reinforced their ownership in the process and encouraged active thinking.

Results

While the pre-interview task allowed participants to collect any visual representations of their doctorate journey, almost all participants used Google searches to find images instead of using their own photos or drawings. This might be due to the metaphorical nature of their thoughts and experiences. The created visual matrix showed two things: firstly, participants tended to use a similar storyline and metaphors throughout their interviews, secondly, there were repeated metaphors and similar images picked by several participants. This suggests that while each doctorate journey is unique, there seemed to be universal experiences, such as feelings of uncertainty, continuous reflection and personal growth. The following examples were selected to provide a window into the students’ journey through their chosen metaphors.

The forest – adventure without a roadmap

Participant 2 explained his doctorate journey as an adventure in a forest without a clear roadmap or instructions:

The last one (picture) is the woods. And as you can see, there are no exits out of the woods. That's how you kind of feel kind of, ‘Right, I've got put on this adventure, but I don't know what the end goal is.’

Did you feel that you at least had some kind of direction or was it just, like, go and wander off in this forest?

It was kind of like if someone was sitting there and they're like, go that way and that's it. That's all you had to go by. They didn’t give you a map, there are no rocks. You can’t say go and take a left by this rock or go by that lake. It was just ‘no, you're going that way’. That's it. That's all you got. That's all the instructions.

They're (peers) kind of going through that journey with you. It's like they're going through their own wilderness, so to say. But you've got a radio talk to them. (…) It took me a long time to kind of realize that you’re on your own path. Your woods are not the same as theirs. You have to kind of set your own goals, your own milestones, and your own targets.

Okay, right. What tools do I need? What skills do I need to do to undertake this adventure to make myself the best prepared to go forward? (…) And there were at times when I was trying to carry an electric. Uh, it's like you're going through a backpack for the wilderness and then you're carrying unnecessary things with you, like a hairdryer when really you need an axe if that makes sense.

Yes, yes. So, do you think it's just a natural process to pack everything in your bag and then select, like, then regret what you're bringing? Or do you think that should be more, more supported just before you put that, being placed in that woods? What's your view?

It would be nice to have that support, and God bless whoever finds the ability to measure that. Like here's the support you need in place. Here's the compass here is that … but I don't think it quite works like that. I think you kind of have to stumble yourself.

Balancing over the sharks – juggling act through obstacles

During the interview with Participant 6, one recurring theme was water: while water represented the endless potential to explore, it also represented several dangers and hardships throughout this exploration. For example, one of the selected pictures showed a person balancing on a rope above the water with several sharks visible in the water. Participant 6 described that he chose this picture to represent the ‘if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger mentality’ that is required to complete a doctorate:

It's definitely the knowing and the not knowing and just bouncing here and then. No idea what's going on or really clear what's going on, that kind of thing. Because from week to week, it changed. And yeah, the different assignments and then all of a sudden, there's a placement here and then that completely puts everything aside.

How was this journey emotionally that these knowing that knowing?

Uhm, it was kind of like that last picture on this slide right now. That's how it was emotionally. Uhm ‘cause if even if you go past, let's say, the first three sharks, there are still four there you know if you drop there, you are still dead. And each shark is different.

Yes, there are different sharks …

Yeah, the ones I just got to watch out for are the great whites …

So, let's see how you imagine once you got those sharks out the way, once you find that end of that rope.

Participant 6: Yeah. Yeah. So that's the plan hopefully like in the first picture, that I'm not missing an arm or anything (laughing), but a huge relief and you feel like at the top of the world, at least when you just finished. (…) But if there is something the programme has equipped you well is that I have one of those guns in my hand when I'm diving in that water, so I can shoot the sharks, you know … So yeah, it equipped you well to deal with things that will come your way in life and when I think about it, it's not just in physiotherapy, that's everyday life.

The always blurry mirror – constant reflection and question marks

Participant 5’s journey focused more on his changing mindset and personal growth through reflections. Participant 5 chose several pictures that represented ‘being lost while seeking knowledge’ in some ways, such as a half-open door with lights coming in, a cleared-up path after a storm, a mind with a ticking clock, and a blurry mirror that ‘keeps steaming up’. During the interview, it has become clear that he went through several liminal journeys:

I think that it's very much what the last picture summarises … You are on a path, there are hills, there are a few obstacles in your way and yeah, there are dark parts to that journey, but there is also sunshine in there … so ultimately it is about interweaving your way through this process. I sit here at this point, you know, I’m just working through the dark at the moment, but I would not stop there with the journey, I’m not very good at quitting, so I will ride it out and I’ll do what needs to be done (…) And I do think that this will be an enlightening process for me at the end, this process. So yeah, I suppose it is a good journey and I suppose whether or not that comes from having those obstacles in your way. If it would be all smooth sailing would you get such a good moment of reflection on it at the end?

Yes, you might not get the rainbows if you don’t have any rain … (both laughing)

Certainly, my mentality and approach … the mental growth throughout the programme for me has been quite an enlightening process where you just kind of feel that parts of your personality that you think have formed and cemented and there is no scope for change there. Yet, there are certain layers that you are surprised to find, explore and change. (…) I suppose this self-reflection for me is somewhere I’ve never gone to before.

I suppose the picture of the mind with the ticking clock just summarizes the business of my head. It’s just that everything is ticking away, it is just so busy, it’s so noisy. I suppose I’m trying to push everything out just to give me only one clock that makes one steady noise that I can compute … there is just too much going on at the moment, it is just confusion. And ultimately that’s just it for me, the consistent thing for me is just mental confusion. But I know that there is clarity there, and eventually, there will be only one clock clicking away.

With regards to the mirror picture, I suppose it is just that I cannot clearly see yet in terms of what is the end product. What is happening at the end of this … I keep losing sight and it keeps getting blurry all the time (…) and that’s the thing, it just keeps steaming up and blocking my view of where I see myself.

Experience of using photo-elicitation interviews

This section aims to capture both the participants’ and the main researcher’s experience of using online photo-elicitation techniques in the study.

Engaging with photo-elicitation techniques as a participant

Most participants found both the pre-interview task and the photo-guided interview process engaging and thought-provoking, and they expressed a dual nature of the task: it served as a reflective tool, and it also helped the participants to prepare for the interview itself which made the interview more effective and therefore the data richer.

I think it definitely helped us to dig deeper and quicker as well, like quickly come to the feelings about the course because if I wouldn't have done that it would have been like a bit slower, like I would have been sitting here like, Oh well, let me think about that, OK? Whereas I already knew what was going to happen (…) And then the slides are in order as well of course, so it was just organised, but also in a way that wasn't restricting my creativity in what I thought was a great way to do it. It was something new, but pictures can speak 1000 words, I guess. /P6/

Most participants used Google searches to pick their pictures by putting keywords in the search engine and then selected a picture that reflected their feelings and thoughts the most. One participant described the process like this:

Yeah. I thought the … to find the pictures for the process was quite simple, it was just effectively Google search I used just effectively. Maybe a keyword I want to summarise my thoughts on that individual slide and then I suppose I just didn't necessarily pick the first picture. I may be picked the picture that resonated most with me (…) You know, I think it was maybe much about colour and stuff of the same picture that kind of I felt the colour may be captured more of what I was feeling. /P5/

The amount of time and investment in picking these pictures differed from participant to participant. Some participants spent a couple of minutes, while others spent hours on the task, which seemed to be a personal choice rather than impacting the overall quality.

Because I had a rough idea about the pre-interview task, I was kind of knowing what I'm going to do, so it took me just less than five minutes to pick out the pictures from Google and some of my pictures, so it was not that hard and … It didn't take much of my time, but in the back of my mind, I was thinking about it. So yeah. It took me less than five minutes just to put everything on the slides and send it off to you. /P13/

Yeah, I found it … It was good. I really enjoyed it and it kind of got me thinking and it said like, oh, we should just spend half an hour on it, but I spent much longer (…) Yeah, it was good just to kind of actually sit back and think about what my journey has been. I think because it (the doctorate) moves so quickly, I think it's good to kind of see actually where I was at the start, you know and so yeah, I found it quite insightful. /P4/

Even though photo-elicitation can be a powerful tool in research, it can also be burdensome for the participants and researchers should reflect on whether such a pre-interview task would add to the quality of data or not. In the case of our research, participants acknowledged that it was an enjoyable process regardless of the extra work it required.

Once I realised that it wasn't gonna kill me, I actually started enjoying it. But first I was like, oh no, another thing that I've got to do. And I completely forgot about that, but it was fine, I actually enjoyed it. As I say, I enjoyed it when I started doing that. (…) It probably took me about 25 minutes or so. Yeah, I think it could probably take someone else a lot longer, but you know my kinda concern was OK, get a picture on each slide anyway. I know that I can talk for Scotland, so I'm not gonna need a lot of prompts to get the information over. /P3/

While photo-elicitation worked with almost every participant, one participant preferred more traditional interviews. This highlights individual differences and preferences, which researchers should be mindful of, and the instructions of the pre-interview task should be carefully worded to encourage creativity over creating a tiresome exercise for the participants.

It's not necessarily my way of thinking, but it didn't surprise me because we've done similar things with images throughout the DPT (the course) and I always struggled with them then, so it's just like I'm not a person for this. And it just to my description, I'm much more of like … I'd rather communicate verbally than through images so I'm glad the interview went with it. It wasn't just the pre-interview task cause I think if it would be just the pre-interview task, I wouldn't have been actually able to translate what anything meant to me. /P11/

As the above quote also highlights, shifting between photo-elicitation and the more traditional interview style should be okay if it better suits the participants. The used methods should be utilized as a means to an end and not followed rigidly.

Overall, a lot of positive feedback was received from the participants regarding the pre-interview task and the nature of the interview itself. Their experiences echoed previous claims about the advantages of photo-elicitation, such as promoting participant agency (Bates et al. Citation2017), adding additional layers by evoking deep emotions, memories and ideas (Glaw et al. Citation2017) and supporting reflection and preparation for the study (Banks Citation2007). Therefore, our experiences suggest that photo-elicitation can be a feasible and effective research tool if it is implemented and presented well.

Reflections on using photo-elicitation methods as an early career researcher

As an early career researcher, it was my first time using a creative, visual data collection method and I found the process remarkably interesting but scary at the same time. My biggest concern was whether the pre-interview task would work at all and how I will be able to integrate it effectively into the verbal interviews. I was also unsure whether the pictures and talking about the pictures themselves would produce any quality data or if it would turn out to be counterproductive. Therefore, my confidence and approach to using probing questions around the pictures fluctuated in the early interviews as I tried to find the best way to maximize the potential of this methodology.

Furthermore, compared to more traditional interview methods, I found that using photo-elicitation added an extra cognitive load on me by requiring me to shift my focus between the pictures, the participant, the verbal information, my decision-making regarding the flow of the interview and the questions I want to ask. I found this process both rewarding and draining at the same time, and I believe that I gained more trust in my own abilities as I have become more confident to work with the participant and their visual storytelling.

Another aspect of the study was the sensitive nature and the emotional load of the research topic. As a psychologist and a doctorate student myself, I feel I could empathize with the participants and provide enough time and space for them to express their emotions and tell their stories. Being a psychologist with qualitative training helped to support the emotional journey of the participants and capture their lived experiences. As a doctorate student, even though I am doing a research doctorate compared to the participants’ taught doctorate programme, I could understand the emotional rollercoaster that most participants described. However, as a practitioner psychologist, I could also ensure that I do not project my own emotions and journey onto the participants and be an impartial listener. Furthermore, the semi-structured nature of the interviews allowed me to be flexible and I made sure that participants could get closure with their journey before rounding up the interview itself.

After each interview, a meeting or email exchange took place between the main researcher and the rest of the research team. Critical discussions were used to monitor the research process and to provide continuous support throughout the research. Initial conversations were about whether there is enough depth and breadth in the collected data and whether any changes are necessary. Later discussions focused on developing an initial understanding of the collected data and highlighting similarities and differences between students’ journeys. Interviews took place in a short period of time which also put a cognitive and affective load on me. These critical discussions helped me to reflect on my lived experience as a researcher and I gained the confidence to fully engage with the developed visual data collection tool. As a result, we felt that the quality and flow of the interviews improved, and a rich dataset was produced.

Overall, engaging in reflective writing and critical discussions seemed to be a crucial part of the research process and we would highly recommend implementing similar reflective processes into any research process to support the emotional load on the researcher, enhance reflection and professional development, and increase the quality of the research.

Key considerations and practical recommendations

Online applications

Like any other online qualitative study, researchers should ensure that both parties have a strong internet connection, and they are familiar with the data collection platforms. This requires a certain level of IT literacy and access to computers which might eliminate the use of this method with certain groups. A detailed and well-structured pre-interview guide is also essential so it can be easily accessed and used on an online platform. Additionally, we would advise researchers to use dual screens: one for sharing the pre-interview task slides, and one to engage with the participant. Being able to see the participant in full size (instead of the smaller screen option when sharing slides on a simple screen) allows the researcher to read participants’ body language and develop a better rapport with them. This might have extra significance when discussing a sensitive and complex topic, such as their challenges during their doctorate programme. Additional training might also benefit novice researchers with limited experience with visual data collection methods. This training could focus on the methodological considerations and decision-making to provide consistency, the development of an effective pre-interview task to maximize the depth and breadth of the collected data and testing of the chosen online platform and its functions (e.g. screen sharing options and transcription services) to fully utilize their advantages.

Nature of the observed topic

Our experience supports previous claims suggesting that photo-elicitation techniques can evoke deep emotions and trigger certain parts of the brain that normally do not get triggered during normal interviews (Harper Citation2002). This does not seem to differ on an online platform; however, additional considerations are proposed. Firstly, study protocols should reflect a certain degree of risk management, such as mitigation of sudden loss of internet connection and availability for debriefing. Secondly, researchers should consider how they could effectively and quickly develop rapport with the participants to create a safe space for sharing and discussing personal experiences on an online platform. Furthermore, our experience shows that conducting research online might take longer (e.g. due to connection issues, or technical problems) and extra time should be considered for initial conversation before asking the participants (whom we just met for the first time online) to open up about their life experiences. To manage our own emotions and anxiety as researchers, we recommend completing pilot interviews and familiarizing ourselves with the used technology. This can reduce the potential negative emotional influence on the participant during the interview (e.g. worrying about getting the technology up and running or being concerned with the timing of the interview).

Working with and not alongside the pictures

Relying heavily on pictures or photos can be quite challenging, especially for early career researchers as they are usually trained in the more ‘traditional’ data collection techniques. Using photo-elicitation interviews requires a different dynamic between participants and researcher with a substantial focus on the chosen pictures (Glaw et al. Citation2017). As pictures can generate metaphors and participants might use a specific language to describe their feelings and experiences (Kahu and Picton Citation2022), the researcher should acknowledge, adapt and use the same language. For example, while one participant described the necessary skills to complete a doctorate as a roadmap, another participant described it as a toolkit or a fine balancing act. We found that working with these pictures and then asking follow-up questions using the same analogies or metaphors can help to further probe and capture their meanings for the participant and allow them to tell their experiences as a story instead of a fact-checking memory exercise. An example of this is when one of the participants early on explained his doctorate journey as being dropped into the woods without a clear path ahead, the researcher asked questions such as, what did help you get out of the woods, was there anyone with you in the woods and whether he thinks others had to go through the same woods or not. Our experience shows that trusting the symbolic representations and working with the used metaphors will increase participants’ storytelling and abstract thinking which then allows better self-expression and descriptions.

Discussion and conclusion

This article gives examples of the use of online photo-elicitation methods and how they have the potential to add further validity, depth, richness and new insights to already existing verbal and written data collection methods (Torre and Murphy Citation2015, Hidalgo Standen Citation2021). Our experience supports previous claims which argue that visual methods enhance the richness of data through the developed metaphors (Bessette and Paris Citation2020, Pujolà and Gonzàlez Citation2022) and help with the relationship between the researchers and participants by making the participant an active part of the study (Bates et al. Citation2017). In the case of the current research, metaphors, such as the always blurry mirror and the adventure without a roadmap, provided a detailed description of what doctorate students may go through when they are experiencing liminal zones. As liminal zone is a complex phenomenon, gaining these detailed and comprehensive insights into personal experiences can enhance our understanding and the support we can provide to the students.

We further argue that it is not just the pictures themselves but a well-structured pre-interview task that can also enhance the quality of the study and increase participant engagement: We believe that data enhancement was achieved in our study because the pre-interview task encouraged reflection, facilitated rapport building, enabled the expression of emotions and helped to capture intangible concepts (e.g. liminality, doctorateness) as easily understandable metaphors (e.g. forest with no clear path out). Through the chronological journey supported by participant-chosen images, the interview felt more like reflective storytelling than a rigid research study which is aligned with the aims of participant empowerment in this methodology (Lapenta et al. Citation2011, Glaw et al. Citation2017).

By providing personal reflections from both the researcher and participants, we wanted the reader to gain an insight into the experience of using online photo-elicitation techniques. Even though most participants enjoyed the pre-interview task, asking participants to do extra preparation for a research study can be a big ask, therefore, researchers should reflect on whether it is necessary and how it might impact the quality of the collected data. Our experience shows that keeping a reflective research diary and engaging in continuous discussions with the research team can boost confidence and increase the effectiveness of the used visual methods. Additionally, we discussed several practical and ethical recommendations to transfer photo-elicitation into a fully online research environment which is unavoidable as a reaction to a worldwide pandemic. Overall, we believe that visual methodologies, such as online photo-elicitation can be and should be implemented into Higher Education research as an innovative methodology for capturing unique insights into both student and staff experiences.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (126.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants who participated in our research study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Banks, M., 2007. Using visual data in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bates, E.A., et al., 2017. ‘Beyond words’: a researcher’s guide to using photo elicitation in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 14 (4), 459–481. doi:10.1080/14780887.2017.1359352.

- Bates, E.A., Kaye, L.K., and McCann, J.J., 2019. A snapshot of the student experience: exploring student satisfaction through the use of photographic elicitation. Journal of further and higher education, 43 (3), 291–304. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2017.1359507.

- Beech, N., 2011. Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Human relations, 64 (2), 285–302. doi:10.1177/0018726710371235.

- Bessette, H.J., and Paris, N.A., 2020. Using visual and textual metaphors to explore teachers’ professional roles and identities. International journal of research & method in education, 43 (2), 173–188. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1611759.

- Birello, M., and Pujola Font, J.T., 2020. The affordances of images in digital reflective writing: an analysis of preservice teachers’ blog posts. Reflective practice, 21 (4), 534–551. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1611759.

- Bitzer, E.M., 2015. The doctoral quest as an alternative metaphoric narrative for doctoral research education. Journal for new generation sciences, 13 (3), 1–16.

- Bitzer, E.M., and Vandenbergh, S.J.E., 2014. How does doctoral education matter? Identity change through doctoral journeys across disciplines. South African journal for higher education, 28 (2), 1047–1068.

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2021. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: SAGE Publications.

- Comeaux, E., 2013. Faculty perceptions of high-achieving male collegians: a critical race theory analysis. Journal of college student development, 54 (5), 453–465. doi:10.1353/csd.2013.0071.

- Glaw, X., et al., 2017. Visual methodologies in qualitative research. International journal of qualitative methods, 16: 1–8. doi:10.1177/1609406917748215.

- Harper, D., 2002. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Visual studies, 17 (1), 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Hidalgo Standen, C., 2021. The use of photo elicitation for understanding the complexity of teaching: a methodological contribution. International journal of research & method in education, 44 (5), 506–518. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2021.1881056.

- Kahu, E.R., and Picton, C., 2022. Using photo elicitation to understand first-year student experiences: student metaphors of life, university and learning. Active learning in higher education, 23 (1), 35–47. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2021.1881056.

- Lapenta, F., Margolis, E., and Pauwels, L. 2011. The Sage handbook of visual research methods. Some Theoretical and Methodological Views on Photo-Elicitation, 201-214.

- Leshem, S. 2020. Identity formations of doctoral students on the route to achieving their doctorate. In issues in educational research (Vol. 30, Issue 1).

- Lobe, B., Morgan, D., and Hoffman, K.A., 2020. Qualitative data collection in an Era of social distancing. International journal of qualitative methods, 19: 1–8. doi:10.1177/1609406920937875.

- Meyer, J.H., and Land, R., 2005. Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher education, 49 (3), 373–388. doi:10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

- Milasan, L.H., 2022. Photo-elicitation: unleashing imagery in healthcare research. In: Arts based health care research: a multidisciplinary perspective, edited by Hinsliff-Smith McGarry and Ali, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 51–67.

- Newman, P.A., Guta, A., and Black, T., 2021. Ethical considerations for qualitative research methods during the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency situations: navigating the virtual field. International journal of qualitative methods, 20: 1–12. doi:10.1177/16094069211047823.

- Pujolà, J.T., and González, V. 2022. Images to foster student teachers’ reflective practice and professional development. Promoting professionalism, innovation and transnational collaboration: a new approach to foreign language teacher education, 223–232.

- Richard, V.M., and Lahman, M.K.E., 2015. Photo-elicitation: reflexivity on method, analysis, and graphic portraits. International journal of research & method in education, 38 (1), 3–22. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2013.843073.

- Roberts, J.K., Pavlakis, A.E., and Richards, M.P., 2021. It’s more complicated than it seems: virtual qualitative research in the COVID-19 Era. International journal of qualitative methods, 20: 1–13. doi:10.1177/16094069211002959.

- Shaw, P.A., 2021. Photo-elicitation and photo-voice: using visual methodological tools to engage with younger children’s voices about inclusion in education. International journal of research & method in education, 44 (4), 337–351. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2020.1755248.

- Shohel, M., and Mahruf, C., 2012. Nostalgia, transition and the school: an innovative approach of using photographic images as a visual method in educational research. International journal of research & method in education, 35 (3), 269–292. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2012.713253.

- Torre, D., and Murphy, J., 2015. A different lens: changing perspectives using photo-elicitation interviews. Education policy analysis archives, 23 (111): 1–26. doi:10.14507/epaa.v23.2051.

- Trafford, V., and Leshem, S., 2009. Doctorateness as a threshold concept. Innovations in education and teaching international, 46 (3), 305–316. doi:10.1080/14703290903069027

- Wisker, G., Robinson, G., and Kiley, M. 2008, April. Crossing liminal spaces: encouraging postgraduate students to cross conceptual thresholds and achieve threshold concepts in their research. In conference for quality in postgraduate research: research education in the new global environment-part, 2.

- Ybema, S., Beech, N., & Ellis, N. 2011. Transitional and perpetual liminality: an identity practice perspective. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34 (1–2), 21–29. doi:10.1080/23323256.2011.11500005