ABSTRACT

When a disaster destroys historical buildings, it is a challenge to maintain the authenticity and originality of the buildings as a heritage tourism site, and their destruction impacts the local community, whose economy is dependent on this heritage. This paper discusses the reinventing of heritage tourism, using the case of Kotagede, Yogyakarta, which was hit by a 5.5 magnitude earthquake in 2006. The paper shows that the earthquake has refreshed the cultural landscape, and that new tourism packages using the story of heritage in combination with the earthquake event have also led to new economic opportunities. We show that the process of reinventing the post-disaster heritage tourism was however challenged by the problems of administrative versus cultural boundaries, confusing criteria concerning heritage products, conflicts in the building restoration process, a lack of interest among younger generations in culture and tradition, and unsustainable government programmes. Based on this, it can be concluded that the overlapping of the post-disaster recovery process with the reinvention of heritage tourism products may permanently change the authenticity of the cultural landscape and lead to a shift from organic place-making to planned placemaking processes.

Introduction

A natural disaster poses significant challenges to the development of tourism and affects all layers of the economy (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015). Besides human causalities, disasters may have impacts on both physical aspects of tourism – for example, on infrastructure, buildings and other facilities – and non-physical aspects of tourism, such as destination image branding and perceptions of safety. These two types of impact need different recovery management approaches, especially in the case of heritage tourism. For tourism destinations that are based on heritage and culture, the recovery approach is mostly related to the originality and authenticity of the product after the disaster. Heritage sites have become significant tourist attractions. For instance, Machu Picchu (Peru), Venice (Italy), Borobudur (Indonesia) and the pyramids (Egypt) have for many years provided opportunities for the local communities in terms of livelihood opportunities.

Over time, such places can become famous tourist destinations through the process of ‘place-making’. Lew (Citation2017) differentiates between two types of place making, namely place-making – which means organic, spontaneous and non-planned processes – and placemaking (i.e. without the hyphen), which means more organised, more planned and having a specific target. It is hard to say that a post-disaster recovery process is an organic process, as it is almost always planned, at least to the extent that it usually comes under the programmes of many organisations working during the immediate recovery phase. The method of reinventing, re-creating and remaking a heritage tourism destination post-disaster must be studied to understand how the dynamics between the site, the community and the organisation of tourism challenge the future viability of that tourist destination.

In the postmodern imagination, heritage is essentially whatever the visitor perceives to be heritage (Poria et al., Citation2006; Timothy & Boyd, Citation2003). The definition and boundaries of heritage seem to expand and become more diverse, for example with the concepts of ‘contemporary archaeology’ and ‘future heritage’ (Fairclough et al., Citation2008), and ‘heritage of the recent past’ (Walton, Citation2009). These eroding boundaries of time and context greatly increase the potential for phenomena related to such ‘non-traditional’ areas as sport (Ramshaw & Gammon, Citation2005), industrial production (Edwards & i Coit, Citation1996; Xie, Citation2006) and heritage site to be recognised as heritage tourism attractions. Surprisingly little academic attention has been paid to the process of the recovery of heritage and culture-based tourist destinations in post-disaster periods. Overall, this research aims to fill the gaps on the content and context of developing countries, in particular Indonesia.

This paper presents an empirical case of a heritage tourism area, which in the process of organic place-making, became dominated by a planned placemaking approach following a disaster. The aim of the research underlying it was to understand the transformations post-disaster and the challenges related to reinventing heritage tourism, using the case of Kotagede heritage tourism in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, which was severely damaged by an earthquake in 2006. Thus, the guiding research question here is ‘how has the transformation taken place in Kotagede post-disaster and what are the challenges related to reinventing heritage tourism?’Although Indonesia has tried to utilise tourism as its major economic resource, the country has long been known as the ‘supermarket of natural disasters’. The present research differs from previous research in that it makes two valuable contributions that thus far have attracted little attention; that is, it enriches the debate on heritage tourism place making and describes the post-disaster recovery process over the past 13 years using the first-hand experiences of the affected local community.

This paper is structured as follows. The following section reviews the literature on the place making concept, heritage tourism and post-disaster recovery processes. Section 3 discusses the methods used to gather and analyse the research data. Section 4 provides the context of the research setting of the Kotagede heritage site and its impact on regional tourism in Yogyakarta. Section 5 explains the findings, especially concerning shifts and transformations, such as new types of organisations, new programmes, new tourism products and new cultural landscapes. Section 6 explores the challenges related to the process of reinventing the cultural landscape of Kotagede. Finally, Section 7 presents the conclusion and the implications of the findings for the academic debate.

Conceptual framework

Place making and the role of authenticity in heritage tourism

Heritage is often developed as a tourist destination as part of an economic strategy to create wealth and a livelihood strategy. When a heritage site becomes a tourist destination, this is usually the result of a non-generic (i.e. organic) place-making process. From a geographical perspective, place making has been used to understand contemporary political processes and social movements. Places, according to Davis (Citation2005, p. 610), are ‘discursive-material formations,’ in which the representation of place enables and ‘legitimizes the performance of certain activities in those places as well as directs the social practices that actively shape the landscapes.’ When a place is designated as a heritage site, there will be certain activities and dynamics of a political and social nature at that particular site. According to Rollason (Citation2016), sites that are created and modified by the rulers can yield essentially historical conclusions about the nature of the sites’ power, or about the power they possess. As such, a place symbolises power in three categories: (1) bureaucratic power, which came into existence through the creation of bureaucratic machinery and the development of laws and ideas about the sites; (2) personal power, which originated through circumstances that made it desirable for influential members or classes of society to forge personal relations with the ruler; and (3) ideological power, which was made possible by the ways in which rulers were able to merge their power with the existing or new religious beliefs. All these types of power can become materialised at sites that are later labelled as historical or heritage sites.

In the process of touristic place making, depending on the context, original sites may be replaced with new buildings or new materials for reconstruction, and sometimes the new buildings are not similar to the old buildings in terms of structure and design. Similarly, disasters have led to transformations of the landscape and the architecture. In some cases, the new construction will be adapted to meet the need for disaster mitigation in the future. Considerations such as time and budget constraints can also influence the landscape, building and place making process. This raises questions regarding the authenticity of heritage tourism, especially in the case of built heritage.

Authenticity has been discussed in many kinds of research related to tourism. Going back to the early academic research on this topic, MacCannell (Citation1973) states that the authenticity of origins is the central aspect that attracts tourists who want to experience real things. More recently, authenticity has also been understood as inter-subjective and is consequently labelled as constructed authenticity. Authenticity in this view depends on the criteria used to define it; it is thus inherently socially constructed (Cohen, Citation2007). As such, a non-authentic heritage tourism attraction can still be experienced as authentic according to the subject who experiences it. Dueholm and Smed (Citation2014) suggest that different conceptions of authenticity can co-exist within tourism settings, whereby new technologies can be implemented to strengthen heritage sites as tourist attractions while still paying attention to authenticity and ongoing authentication processes. Moreover, the perception of authenticity has been studied by Meng and Choi (Citation2016) and was shown to be a significant predictor in determining desire and behavioural intention in slow tourism. Clapp (Citation1999) writes that authenticity is the attribute of the quality of heritage. Chhabra et al. (Citation2003) suggested that not every component of an experience needs to be authentic (or even satisfactory), as long as the combination of elements generates the required nostalgic feelings.

In post-modern terms, constructed or cultural authenticity is perceived as a non-fixed commodity and it is continually negotiated and reinvented with every act of recognition (Lowenthal, Citation2015). The process of negotiation and reinvention can be in the form of economic development and commodification, nationalism, heritage conservation and ‘museumisation’, and the creation of new cultures and arts (Richards, Citation2011).

Besides authenticity, the reinventing of heritage tourism post-disaster can be difficult due to various challenges in the process. First, and in line with the above, heritage can be interpreted differently within any one culture at any one time, as well as between cultures and over time (Graham & Howard, Citation2008). Further, it is also apparent that heritage takes a variety of official (i.e. state-sponsored) and unofficial forms. Different agencies, communities and levels of government can use their own definition of heritage, which impacts heritage tourism practices in terms of the set rules, norms and conventions. Moreover, those implications change over time from culture to culture or from period to another (Hall, Citation1997). Second, there is the tension associated with different ways of managing, governing and making use of heritage. It could for instance create a conflict of interest concerning heritage management, especially with regard to the tension between conservation and commodification. Notably, the commodification and commercialisation of heritage has been regarded as a strategic component to conserve and preserve heritage. Heritage in many parts of the world has clearly been exploited as an economic resource by intentional or unintentional place-making processes. Third, the preservation and conservation purpose can be replaced by the survival purpose. In this case, many of the cultural values are no more important than the need to build a better life after the emergency situation.

In general, there is a strong connection between the literatures on heritage conservation, place-making and tourism. Heritage sites are usually places with strong cultural elements and they reflect personal, bureaucratic or ideological powers. Moreover, heritage sites have often been developed to become heritage tourism packages that offer a place for tourists to experience the cultural elements of the past. For heritage tourism destinations, a disaster can either disturb or stimulate the place-making process, as is explored in the following sub-section.

Recovery post-disaster and reinventing heritage tourism

In the context of Indonesia, heritage is regulated under Heritage Law No 11/2010 (Undang-undang Cagar Budaya Nomor 11 Tahun 2010). The government provides incentives for owners of heritage buildings by reducing or entirely exempting property taxes. Some issues have been recorded in relation to heritage designation in Indonesia, including the age of the building/material/structure, the national criteria stated in Article 5 of the Law of Cultural Properties No.11/2010, which is still vague and overlapping. This law needs to improve in both concept and depth (Fitria et al., Citation2015). Indonesia’s heritage laws need more consideration regarding post-disaster situations.

The disaster management lifecycle involves four aspects, namely mitigation, preparedness, relief/response and recovery (Henstra et al., Citation2004). Of these four aspects, recovery is the least understood in terms of academic research (Calgaro et al., Citation2014; Coppola, Citation2006; Lloyd-Jones, Citation2006). Measuring recovery is complex because of its diverse dimensions, for example economic, transport and demographic dimensions (Aldrich, Citation2012). To deal with this complexity and difficulty, many researchers conceptualise recovery as a ‘process’. This influences the way the recovery efforts are assessed. This perspective has been increasingly adopted by researchers conducting recovery research (e.g. Aldrich, Citation2012; Coppola, Citation2006; Mileti, Citation1999). The research is further separated into two phases, namely short-term recovery and long-term recovery. Research on short-term recovery focuses on activities to stabilise the living conditions of the affected population, such as clearing the debris, restoring major infrastructures, providing transitional shelters, etc. (Coppola, Citation2006), whereas research on long-term recovery is generally concerned with the rebuilding and rehabilitating of individuals, households and communities. In this stage, communication becomes very important, especially regarding the marketing campaign that informs consumers and other stakeholders about the status of the destination to regain the consumers’ confidence (Ritchie et al., Citation2004).

Ritchie (Citation2009) discusses three types of post-disaster transformations, namely human and community transformation, organisational transformation and destination transformation. Human and community transformation is achieved if the community is able to reflect on the past using the disaster as a starting point and to plan for the future. Organisational transformation means changes in the vitality and longevity of the organisation. For instance, there is a possibility of structural changes in the composition and numbers of tourism stakeholders, and eventually of new tourists, new products and new programmes within the organisation (Ritchie, Citation2009). Finally, the renewing generally indicates destination transformation and rebuilding of the infrastructure to be better prepared for future disasters by integrating mitigation and disaster planning strategies. This can only be achieved if the awareness and the cohesiveness within tourism destinations are improved. This is then mostly translated into new policies that support the growth of tourism post-disaster.

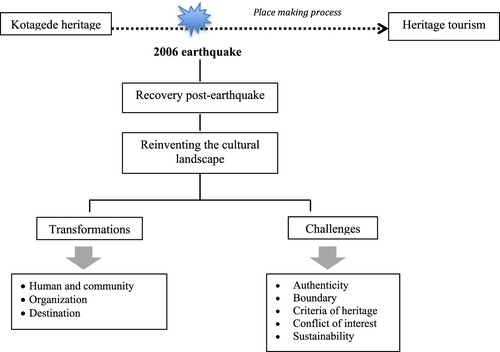

To sum up, recovery is conceptualised as a process and the focus of the present research was specifically on the long-term aspect of recovery. presents the analytical framework. The period of 13 years after the occurrence of the event allowed an examination of the process of recovery, as well as of the transformations, post-disaster. This paper first focuses on the transformation process, and then analyses the challenges related to the reinventing of the cultural heritage process in terms of the possibility of conflict, authenticity, boundaries and governing the heritage site.

Methods

The present research combined a qualitative approach with a case study method. Beeton (Citation2005) defines a case study as a holistic empirical inquiry used to gain an in-depth understanding of a contemporary phenomenon and its real-life context, using multiple sources of evidence. Using this perspective, data were collected from the relevant documents, direct observations and in-depth interviews in two phases. The first phase was in 2011/12, when the first author identified and observed the most important stakeholder groups, and also participated in several projects related to the economic recovery process and map-making exercises in preparation for future disasters. This allowed the first author to conduct a deep field observation and participatory process during this phase of the recovery process. The first author conducted interview with the six organisations working in tourism in the Kotagede area, namely Yayasan Kanthil, Forum Joglo, Pusat Studi Dokumentasi (PUSDOK) Kotagede and BKM PNPM Mandiri Pariwisata, OPKP (organisasi pengelola kawasan pusaka) and Jogja Heritage Society – and with the local sub-district government.

The second phase was in 2019, when the authors re-interviewed (by video call) the organisations and residents working in the tourism industry in Kotagede to investigate the changes and transformations since the 2006 earthquake. Some phone calls were also made and some text messages were exchanged to confirm or clarify parts of some of the initial interviews. A topic list was used as an interview guideline and each interview lasted around 60–90 minutes. Key informant interviews were conducted with the representatives of six organisations working on heritage conservation and tourism in Kotagede. Resident interviews were conducted with the owners of ten traditional jogloFootnote1 houses, Kotagede tour guides and silver crafters. Total respondents in the second phase were 16 people. These respondents were selected by snowball sampling, especially-targeting residents who own joglo houses and resident who have been living in Kotagede since before the earthquake. Interviewees were asked whether they were willing to participate in the research, and the author gained their verbal consent. Interviews were conducted in two languages, Javanese and Indonesian, which are the first author’s native languages. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and translated into English. The data were then manually grouped and subjected to thematic analysis in descriptive narrative texts using regular text processing software (MS Word).

The questions put to the individual informants depended on their role in the recovery process. The community members were asked about their experiences during the 13 years of the recovery process and their stories of reinventing Kotagede as a heritage tourism location. The representatives of both internal and external organisations working in Kotagede were asked about their programmes, roles and challenges, and Kotagede’s prospects ().

Table 1. Aspects of analysis and explanations.

Case study: Kotagede heritage tourism, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Yogyakarta’s historical and cultural background makes it a popular tourism destination: in 2018, it received nearly four million tourist visits. Kotagede itself is promoted as an exemplar of traditional Javanese culture. The first capital of the kingdom of Mataram was situated in Kotagede. The kingdom was established in the sixteenth century and this vital civilisation spread Islamic teachings and culture combined with Javanese traditions.

Kotagede has a unique architectural landscape. It is considered a heritage site of the Mataram kingdom and includes buildings such as the Grand Mosque (seventeenth century), royal cemeteries (one containing the grave of the founder of the Mataram, Panembahan Senopati (d. 1601)), the Kotagede market, traditional Javanese houses (joglo) and Kalang houses (the houses of successful merchants who lived in Kotagede during the Dutch occupation period). Some of the Kalang houses have been transformed into cafés or restaurants, which are sometimes rented by the local community or outsiders for special events. The Kotagede area is designated as a heritage preservation site (cagar budaya) by the local government of Yogyakarta with Regional Law No 11/2005 chapter 1 verse 6 (Anurogo et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, in 2011, Kotagede and five other heritage areas in Yogyakarta were designated as a heritage district by the national government (Government Decree; SK Gubernur DIY No. 186/KEP/2011) (Rahmi, Citation2017). The most interesting aspect of the local culture is the cultural landscape of Kotagede – the Catur Gatra (‘four pillars’), namely the palace, the mosque, the market and the square. Kotagede’s heritage tourism is geared toward heritage education, although its visitors are both domestic and international. Many domestic tourists are interested in pilgrimage tourism activities surrounding the Agung mosque. Moreover, two kinds of boundaries exist in Kotagede, namely a cultural boundary and an administrative boundary. Cultural boundary refers to the post-Mataram Kingdom area, while the administrative boundary refers to the Yogyakarta Province government. Within the cultural boundary of Kotagede, there are three kampongs under the administration of the city of Yogyakarta (Purbayan, Prenggan and Rejowinangun) and two kampongs under the administration of Bantul Regency (Jagalan and Singosaren). In 2017, the Kotagede cultural boundary was home to 43,000 people (Statistics Indonesia, Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

On 27 May 2006, a strong earthquake (magnitude 6.3) hit Yogyakarta and several parts of the surrounding regions. The earthquake killed 5751 people and injured a further 29,473. A total of 145,929 houses were completely destroyed and 190,843 were severely damaged. Although the worst-hit area was in the Bantul Regency, the Kotagede district was strongly impacted by the earthquake. The major loss for Kotagede was the destruction of and damage to the joglo houses, which are part of the tourist attraction (see of Joglo house). According to the organisation focusing on heritage assessment (Pusaka Jogja Bangkit; PJB), eight traditional houses were completely ruined, 47 were severely damaged, 16 were partially damaged and 17 were lightly damaged (Rahmi, Citation2017). In addition, more than a thousand non-traditional houses were damaged. The recovery status report (Anonymous, Citation2008) showed that the earthquake damaged 90.52% of the private assets held in the housing, social and productive sectors in Yogyakarta Province.

Transformations of Kotagede heritage tourism

Human and community: new tourism products – the Kotagede heritage trails

Human and community transformations post-earthquake are reflected by two aspects, namely the communities’ reflection on the value and quality of the houses and the acceptability of tourism activities. First, the earthquake made the community consider replacing the damaged houses with a different type of housing that is more modern and commonplace. Those who had a good financial situation started to consider stronger types of buildings. Moreover, the local government produced a guideline for housing reconstruction only for regular houses, and not the traditional ones. This resulted in only a small number of traditional joglo houses being rebuilt. Preservation considerations did not lead them to rebuild traditional joglo houses; instead, they built modern houses that are smaller, more effective and minimalistic.

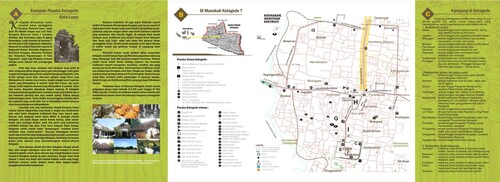

Second, in 1998 a group of Kotagede’s people led by a young lady had established Kotagede Heritage Trails (KHT) as a new tourism package (the KHT was originally called ‘Rambling Through Kotagede’). Its activities were suspended for four years following the earthquake, but when the activities were resumed, it became more popular. It became even more popular in 2012 and is still operating. The package comprises a map that guides visitors through Kotagede to several tourism spots, such as the market and traditional houses, as well as culinary visits and performance art events (Purwohandoyo et al., Citation2018). Visitors buy the tour package from the community organisation, which then distributes the money to the community based on their contribution to the scheme. shows the KHT guide map.

Figure 3. Kotagede Heritage Trails guide map. Source: Department of Architecture and Planning, Universitas Gadjah Mada, 2018.

The heritage trails were introduced by external agencies and subsequently the Kotagede Heritage Trails network was operated by the community of Kotagede itself. As a tourism package, KHT has increased the community’s opportunities to benefit from tourism activities. Although the traditional joglo houses suffer from a lack of authenticity due to some changes in their structure and the materials used, with the help of the new tourism package, Kotagede managed to recover from the earthquake. Statistics Indonesia data show, for instance, consistently increasing numbers of visitors to the Mataram royal cemetery (). Thus, the KHT has supported the recovery process and reinvented Kotagede as a heritage tourism site in a more planned way.

Table 2. Visitors to the Mataram royal cemetery, Kotagede.

Organisational transformation: new organisation, new programme and new actors

Following the earthquake, Yogyakarta received attention from local, national and international organisations. Since the local government of Yogyakarta Province declared that it could manage the disaster recovery itself, the earthquake was considered a local disaster. In the Indonesian Disaster Management Law, local and national disasters have different consequences in terms of financial support and institutional responsibility. The national government conducted four programmes: the Houses and Settlement Reconstruction Programme, under the National Disaster Management Coordinating Board for Disaster (BAKORNAS); infrastructure restoration, including drainage, roads, bridges, etc., performed by the Ministry of Public Works; the rebuilding of educational and health facilities and government offices; and the recovery of the economy by providing training in labour skills and small credits for small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The overall programme was called the Jogja Reconstruction Fund (JRF). Thanks to this fund, Kotagede district was able to recover from the earthquake quicker than other areas, such as Pleret or Sewon district. In the governmental institutions, at least five branches of government offices supported the recovery, including the Yogyakarta Cultural Board, the Ministry of Public Works, the Board of Cultural Conservation Yogyakarta, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Indonesia, and the Regional Planning and Development Board of Yogyakarta. International agencies, such as the World Bank and PUM Netherlands, had provided aid and assistance for immediate recovery (Wijayanto, Citation2014). Also, the local universities in Yogyakarta sent students to perform community services. Universitas Gadjah Mada, a national university located in Yogyakarta, built a replica of a traditional joglo house, which was then used to host exhibitions for tourists.

The transformation of community organisations in Kotagede is reflected in the new programmes that have been conducted since the earthquake. Organisations such as Yayasan Kanthil, Forum Joglo and PUSDOK previously focused only on cultural and tourism matters (Widyastuti, Citation2009). Yayasan Kanthil, for example, focused on cultural preservation, while PUSDOK focused on collecting Kotagede literature and provided information to visitors. After the earthquake, disaster mitigation measures, such as providing evacuation routes for tourists, were implemented. The organisations also participated in the reconstruction of joglo houses by assessing the level of damage and providing data for external agencies that wanted to help. Moreover, the government provided training and all organisations focused on Kotagede were persuaded to join and implement the evacuation guidelines. The marketing strategy for reintroducing Kotagede into the tourism market was also improved by developing trail maps and building the Kotagede library and website.

During the 13-year recovery and reinventing process, many new organisations were developed in the community. Most of the organisations were established to act as the local counterparts of an external donor that was funding parts of the recovery. The community then agreed to establish a new organisation called Heritage District Local Organisation for Heritage Management (Organisasi pengelola Kawasan pusaka Kotagede; OPKP). Although Kotagede already had Forum Joglo – an umbrella organisation of five kampongs for conservation, preservation and making use of Kotagede – only the OPKP tackled the recovery programme of the external donor. According to the informants, there was an overlap in the personnel of the various organisations, meaning that some people act for several organisations at the same time. The OPKP is currently inactive. A new organisation – Badan Pengelola Kawasan Cagar Budaya (Management Board for Cultural Heritage) – has been established. An organisation called Kampong Wisata was also established with government support in the period of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono to handle the PNPM (National Programme for Community Empowerment) programme.

External organisations have supported the recovery of Kotagede in many ways, for example by providing economic recovery programmes and restoring traditional houses. Two days after the earthquake, the Centre for Heritage Conservation of the Department of Architecture and Planning in the Faculty of Engineering at Universitas Gadjah Mada set up a heritage conservation programme called Pusaka Jogja Bangkit (Jogja Heritage Revival; JHR). This revitalisation programme was supported by collaborative parties from external organisations, including the Jogja Heritage Society, the Centre for Heritage Conservation, the Indonesian Network for Heritage Conservation, and ICOMOS Indonesia. The local community organisations were invited to actively participate in the programmes. Adishakti (Citation2008) mentioned that the programme focuses on building the local economy by strengthening both the tangible and the intangible heritage. Some training was provided to enhance the capacity of the organisations in both disaster mitigation and tourism development. The programmes for tourism development were introduced after the restoration of the houses was completed.

Destination transformation: building and landscape transformation

Perhaps the most visible transformation is that of the cultural landscape, namely the replacement of damaged traditional joglo houses with modern houses. The joglo houses used to be Kotagede’s third major attraction, after the mosque and the royal cemetery. Traditional joglo houses have a different structure, style and size. Since the earthquake, however, the appearance of the cultural landscape of Kotagede has become more vague. In addition, the rapid reconstruction projects driven by non-local and non-traditional approaches jeopardised the cultural urban dwelling because they did not consider the socio-cultural, environmental and economic implications. Although the reconstruction projects are not agency driven, the use of modern building technologies is more prominent.

Shifting from traditional joglo houses to regular houses was also part of the adherence to the government’s guidelines. An amount of money was made available for the collapsed houses as identified by the government. In the programme of rehabilitation–reconstruction sponsored by the government, monetary support for traditional joglo houses was a similar amount as the subsidy for regular houses. Thus, the amount was not enough to build a similar traditional house. Therefore, the majority of Kotagede homeowners decided to build as easily and as quickly as possible by following the government’s suggestion and thereby ignoring the rebuilding of the traditional joglo houses. However, a small number of traditional joglo houses remain.

Challenges in the reinventing process

Although the Kotagede’s process of recovery can be regarded as both rapid and successful, some conflicts followed the restoration process, as discussed in the following sub-sections.

Place making versus authenticity

After the earthquake, local and external organisations that focused on recovery devised a set of approaches, programmes and activities to reinvent Kotagede as a heritage site. This indicates a non-organic process of place making. The economic value became the primary target by providing the experience of heritage. Kotagede promoted its unique cultural landscape of the kampongs to attract tourists. However, very few joglo houses are considered original in terms of materials. The authenticity of the attraction is therefore questioned. The homeowners and the representatives of organisations working on heritage conservation understand that; however, their perceptions about authenticity are diverse. For instance, the local community believes that as long as the joglo house in terms of its design is intact, it is authentic. Therefore, the existence of joglo houses automatically preserves the Javanese culture.

Administrative boundary versus cultural boundary

There is also a conflict between the administrative boundary and the cultural boundary. The former is one of the districts (kecamatan) in the city of Yogyakarta. However, within the cultural boundary, the old Kotagede includes two other kampongs that are under the administration of Bantul Regency. They previously formed one united area of old Kotagede. This leads to problems in many aspects of recovery programmes. The administrative boundary has become the basis for delineating the target of recovery programmes, which is under the administration of Bantul Regency (Kampong Jagalan and Kampong Singosaren) and the city of Yogyakarta (Kampong Prenggan, Kampong Rejowinangun and Kampong Purbayan). These two administrations have different priorities concerning programmes and budgets. In the organic tourism place-making process, the cultural boundary seems to work better than the administrative boundary, because the flow of people and their interests are not restricted to the administrative boundary. Tourists are free to visit any part of the kampong they wish to visit.

Confusing criteria on heritage products

The definition of ‘heritage product’ has become a challenge for both the community and the government. For the community, heritage is more about meaning than about material artefacts. However, the national government needs fixed standards and criteria to define something as a heritage product. The definition has implications for the funds the programme receives. According to the interviews, the community had asked the government to support the maintenance of the joglo houses. The government responded by offering a discount on the annual property tax on joglo houses. Yet, the discount (IDR 50,000/USD 5) is not enough to maintain the houses.

Moreover, the definition of ‘heritage building’ is also problematic, because the government will only financially support the maintenance of houses that are older than 50 years and thus qualify as a ‘heritage building’. Unfortunately, post-earthquake, many joglo houses were transformed into new houses that are not more than 50 years old. Moreover, the government does not support the new ‘traditional’ houses even though they are exact replicas of the original joglos. One respondent said:

The cultural heritage should be at least 50 year old, and the cultural preservation material is the building that is designated by the government. The problem is the overlapping of the materials; the same building can have double registrations. When we change the roof of or renovate the wall of the joglo, the government said it is not authentic anymore and cannot be registered as cultural heritage, it is very ambigu in the Law, (Respondent 1, 2019)

Lack of interest among the younger generation in the cultural aspects of Kotagede

A lack of interest among the younger generation in Kotagede’s culture and traditions has been observed. Many young and educated people have moved to Jakarta or another city to find jobs. Although this shows that the community has recovered and can send their children away to higher education institutions, the number of workers in the traditional silver workshops has dropped significantly and the population composition has become more dominated by the elderly rather than the young.

Tourism activities as a livelihood have become more acceptable in the community. Introducing some new programmes from outside agencies changed the community’s perception of tourism before and after the disaster. Previously, tourists mainly visited the Catur Gatra (‘four pillars’), that is, the mosque, the square, the market and the cemetery. After the introduction of the Kotagede Heritage Trails, the community became aware that tourism could also benefit the surrounding areas. One informant said that the tour to the joglo houses was initiated in 1998, but it had not attracted many local people or tourists; thus, the activities had been very rarely conducted. Apparently, the community now agrees and allows the development of the tour to visit their neighbourhood.

Although tourism activities have become more acceptable since the earthquake, as mentioned younger people leave Kotagede to work in cities. This has negative consequences not only for the already declining handicraft industry, but also for cultural activities and the traditional joglo houses. However, the younger generation’s lack of interest in the local culture may also be caused by the low wages paid to those with culture-related jobs. One of the respondents mentioned that:

More and more young generation do not interested in the culture and history of Kotagede, the development of tourism is hoped to give new perspective for young generation that their culture and history is valuable, by showing that people from outside Kotagede visit and like it’ (Respondent 3, 2019)

Unsustainable programmes

Since the end of the recovery period, Kotagede’s reinventing process has continued on its own. The local government, including the Tourism Board and the Culture Board, followed up by supporting the culture and tourism development. However, many of the programmes have some problems in the implementation phase. One of the informants said that some programmes did not achieve the targeted outcome. For example, the training for tour guides that was conducted has not produced a sufficient number of tour guides, because the participants in the training were undergraduate students who then obtained other jobs after graduation.

Another problem concerns the community’s participation. As one of the local community activists said, ‘We are merely the target of development and programmes, not the actors’. There is a tendency for the community of Kotagede to be a target of programmes from the government. The term ‘target’ used by the key person refers to the lack of space to participate in the planning process for Kotagede. They tend to just receive the top-down programmes planned by the government. They also said that the government does not have a clear vision on how to develop Kotagede. For instance, when there is an event or programme (e.g. performance art or a cultural festival), the government hires external private event organisers to handle it. The local government had to employ this mechanism because the national government has ruled that only private legal companies can be contracted by local governments to conduct certain activities. Some members of the Kotagede community, however, said that the community was not asked to participate in the programmes.

Discussion and conclusions

In the post-earthquake recovery process of heritage tourism development in Kotagede, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the recovery process overlapped with the reinventing of the destination’s image branding. Kotagede as a case study has shown that there are dynamics and challenges in both the reinventing and the recovery process. The post-disaster recovery process that generally follows the rules and standards for disaster mitigation is not always in line with the sustainability of the cultural landscape. For disaster mitigation purposes, the cultural aspect is sometimes diminished, and it does not have priority. This creates a conflict over authenticity and originality, which are the primary capital of heritage tourism. The 13-year reinventing process of Kotagede following the 2006 earthquake has revealed some essential notions. These notions are the contribution of this research. These include the idea that disasters can change the cultural landscape; that two kind of power of place (i.e bureaucratic and ideologic) can be found in one place; authenticity is not the only factor to deal with strategy post disaster; and in the recovery process it is possible to have at least two sources of interest, in this case from the government and the community at large.

The findings of this study reveal a few different things. First, disasters can change the cultural landscape. Kotagede’s heritage tourism has undergone a cultural landscape transformation. Although it is believed that global issues, such as the migration of both people and knowledge, influenced the decisions on the preservation of cultural landscapes, the earthquake also triggered a process of change. A lack of financial support and of interest in cultural matters led to the transformation of Kotagede’s cultural landscape. It may build perspective that transformation post-disaster is needed in order to achieve resilience (Rindrasih, Citation2018).

Second, Kotagede has shown the power of place in terms of bureaucratic power (see Rollason, Citation2016). Since Kotagede is designated as a heritage conservation area, most of the programmes for development and the reconstruction of facilities to enable livelihood recovery were targeted at the Kotagede community. Moreover, the ideological power of place is also reflected in the large numbers of visitors doing pilgrim tourism, namely to pray in the mosque. Therefore, although Kotagede can be said to become resilient through innovating its products, and it has shown two kinds of place-power, that is, bureaucratic and ideological power.

Third, although the authenticity is questioned, Kotagede recovered and reinvented itself as a heritage tourism site through government interventions in terms of planned programmes and community initiation. Clapp (Citation1999) writes that authenticity is the attribute of the quality of heritage. The case of Kotagede has shown that although the quality of authenticity has been reduced due to the earthquake, heritage tourism can still recover quickly. This is in line with Chhabra et al. (Citation2003), who say that not every component of an experience needs to be authentic (or even satisfactory) as long as the combination of elements generates the required nostalgic feelings. In this sense, an object only becomes heritage by its social or political purpose and subsequently acquires an economic sense in its new role as a heritage object (see van Gorp, Citation2003). Heritage is capable of being interpreted differently within any one culture at any one time, as well as between cultures and through time (Graham & Howard, Citation2008). The case of Kotagede has also confirmed this.

Finally, the government perspective on tourism development tends to be dominated by planned reinventing, especially in relation to programmes and marketing. However, the community perspective on reinventing tends to follow organic place-making (see Lew, Citation2017). The local government is a key actor in reinventing heritage tourism through its projects and programmes. Further, the government considers that heritage tourism has a direct economic use.

This paper argues that a tourism destination that successfully connects the place with its history and the political and place framing is able to recover from a disaster and to transform the ‘bad story’ of disaster into a better narrative to support the tourism industry. In addition, the authenticity of a heritage product should not hamper the recovery of a heritage tourism destination following a disaster. Furthermore, more research should be done to understand the role that a new product and new organisation play in a community’s wealth and to evaluate the effectiveness of government programmes that promote the resilience of heritage tourism in different parts of the world.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Annelies Zoomers and Professor Tejo Spit for valuable inputs during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erda Rindrasih

Dr. Erda Rindrasih is a development divison staff of Tourism Studies Programs the Graduate School Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. She is also a director of Indonesia Tourism Watch (ITW). Her research focuses on tourism and geography, disaster and tourism, resilience, community based tourism and halal tourism.

Patrick Witte

Dr. Patrick Witte is associate Professor in Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Patrick is specialised and internationally recognised in the interconnection of land use and transportation planning, with a particular focus on integrated corridor development (doctoral dissertation, 2014) and inland port development (lead editor of a special issue in Journal of Transport Geography, 2020). He has authored or co-authored over 30 international, peer-reviewed journal articles in the past 5 years.

Notes

1 The word joglo refers to the shape of the roof. In the highly hierarchical Javanese culture, the shape of a house’s roof reflects the social and economic status of the owners of the house. Joglo houses are traditionally associated with Javanese aristocrats (Tjahjono, Citation1998).

References

- Adishakti, L. T. (2008). Community empowerment program on the revitalization of Kotagede heritage district, Indonesia post-earthquake. In T. Kidokoro, J. Okata, S. Matsumura & N. Shima (Eds.), Vulnerable cities: Realities, innovations and strategies (pp. 241–256). Springer.

- Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. University of Chicago Press.

- Anonymous. (2008). Recovery status reports The Yogyakarta and central Java earthquake 2006. Universitas Gadjah Mada and International Recovery Platform.

- Anurogo, W., Lubis, M. Z., Hartono, H., Pamungkas, D. S., & Dilaga, A. P. (2017) Kajian ketahanan kawasan wisata berbasis masyarakat dalam penguatan ekonomi lokal serta pelestarian sumberdaya kebudayaan kawasan kotagede yogyakarta. Jurnal Ketahanan Nasional, 23(2), 238–260. doi: 10.22146/jkn.25929

- Beeton, S. (2005). The case study in tourism research: A multi-method case study approach. In B.W. Ritchie, P. Burns & C. Palmer (Eds.), Tourism Research Methods: Integrating Theory with Practice (pp. 37–48). CABI.

- Calgaro, E., Lloyd, K., & Dominey-Howes, D. (2014). From vulnerability to transformation: A framework for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(3), 341–360. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2013.826229

- Chhabra, D., Healy, R., & Sills, E. (2003). Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 702–719. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00044-6

- Clapp, G. (1999). Heritage tourism. Heritage tourism report. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Division of Travel, Tourism, Film, Sports and Development.

- Cohen, E. (2007). ‘Authenticity ‘in tourism studies: Aprés la lutte. Tourism Recreation Research, 32(2), 75–82. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2007.11081279

- Coppola, D. P. (2006). Introduction to international disaster management. Elsevier.

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Davis, J. S. (2005). Representing place: ‘deserted isles’ and the reproduction of bikini atoll. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 95(3), 607–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00477.x

- Dueholm, J., & Smed, K. M. (2014). Heritage authenticities–a case study of authenticity perceptions at a Danish heritage site. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(4), 285–298. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2014.905582

- Edwards, J. A., & i Coit, J. C. L. (1996). Mines and quarries: Industrial heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 341–363. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00067-4

- Fairclough, G., Harrison, R., Jameson, J. H., & Schofield, J. (2008). The heritage reader. Routledge.

- Fitria, I., Ahmad, Y., & Ahmad, F. (2015). Conservation of tangible cultural heritage in Indonesia: A Review Current national criteria for assessing heritage value. Proceeding 5th Arte Polis international conference and Workshop – “reflections on Creativity: Public Engagement and The making of place”, Arte-Polis 5, 8-9 August 2014, Bandung, Indonesia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 184.(2015) 71–78.

- Graham, B. J., & Howard, P. (2008). The Ashgate research companion to heritage and identity. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage.

- Henstra, D., Kovacs, P., McBean, G., & Sweeting, R. (2004). Background paper on disaster resilient cities. Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction.

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007

- Lloyd-Jones, T. (2006). Mind the gap! post-disaster reconstruction and the transition from humanitarian relief. RICS.

- Lowenthal, D. (2015). The past is a foreign country – revisited. Cambridge University Press.

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. doi: 10.1086/225585

- Meng, B., & Choi, K. (2016). The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 57, 397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.003

- Mileti, D. (1999). Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States. Joseph Henry Press.

- Poria, Y., Reichel, A., & Biran, A. (2006). Heritage site management: Motivations and expectations. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 162–178. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.08.001

- Purwohandoyo, J., Cemporaningsih, E., & Wijayanto, P. (2018). Pariwisata Kota pusaka. UGM Press.

- Rahmi, D. H. (2017). Building resilience in heritage district: Lesson learned from Kotagede Yogyakarta Indonesia. Paper presented at the IOP conference Series: Earth and environmental Science. 99(1) 012006.

- Ramshaw, G., & Gammon, S. (2005). More than just nostalgia? Exploring the heritage/sport tourism nexus. Journal of Sport Tourism, 10(4), 229–241. doi: 10.1080/14775080600805416

- Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.008

- Rindrasih, E. (2018). Under the Volcano: Responses of a community-based tourism Village to the 2010 Eruption of Mount Merapi, Indonesia. Sustainability, 10(5), 1620. doi: 10.3390/su10051620

- Ritchie, B. W. (2009). Crisis and disaster management for tourism. Channel View Publications. doi: 10.21832/9781845411077

- Ritchie, B. W., Dorrell, H., Miller, D., & Miller, G. A. (2004). Crisis communication and recovery for the tourism industry: Lessons from the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2-3), 199–216. doi: 10.1300/J073v15n02_11

- Rollason, D. W. (2016). The power of place: Rulers and their palaces, landscapes, cities, and holy places. Princeton University Press.

- Statistics Indonesia. (2018a). Kabupaten Bantul dalam Angka 2018. Retrieved 7 March, 2019, from https://bantulkab.bps.go.id/publication/2018/08/16/40e5d68cbcf9f2c86bd402ba/kabupaten-bantul-dalam-angka-2018.html

- Statistics Indonesia. (2018b). Kota Yogyakarta dalam Angka 2018. Retrieved 7 March, 2019, from https://jogjakota.bps.go.id/publication/2018/08/16/8e60dd366fc77ddeee9ea008/kota-yogyakarta-dalam-angka-2018.html

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage tourism. Pearson Education.

- Tjahjono, G.1998). Architecture. Indonesian heritage. 6. Archipelago Press.

- van Gorp, B. H. (2003). Bezienswaardig: historisch-geografisch erfgoed in toeristische beeldvorming. Eburon.

- Walton, J. K. (2009). Seaside tourism on a global stage: ‘resorting to the coast: Tourism, heritage and cultures of the seaside’, Blackpool, UK, 25–29 June 2009. Journal of Tourism History, 1(2), 151–160. doi: 10.1080/17551820903388120

- Widyastuti, B. (2009). Motif Sosial Yayasan Kanthil Dalam Melestarikan Budaya Lokal Kotagede [Unpublished Thesis]. Islamic State University. Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta. http://digilib.uin-suka.ac.id/3159/ - on 18 February 2019

- Wijayanto, P. (2014). Managing Kotagede heritage districts after 2006 earthquake. Journal of Disaster Mitigation for Historical Cities, 8(July 2014). http://digilib.kotagedelib.com/file/article/19.pdf

- Xie, P. F. (2006). Developing industrial heritage tourism: A case study of the proposed jeep museum in Toledo, Ohio. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1321–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.06.010