ABSTRACT

Film-induced tourism at heritage attractions (HAs) is a growing industry of international relevance. It can influence visitors’ expectations of the site and further their preferences for interpretation to include a degree of reference to the film(s). Drawing upon in-depth interviews with visitors at a UK HA further popularised through book and film, this paper explores visitors’ preferences for heritage interpretation. The paper identifies four visitor taxonomies – vigorous followers, curious investigators, versatile explorers and purposeful avoiders. It ultimately highlights the value of data-driven visitor taxonomies, providing an in-depth insight into heritage tourism in general and film-induced tourism at this heritage site in particular. Thus, this paper contributes to a greater understanding of the popular media products’ influence on visitor preferences for on-site heritage interpretation.

Introduction

Film-induced tourism or ‘tourism which involves visits to places celebrated for associations with books, authors, television programmes and films’ (Busby & Klug, Citation2001, p. 316) is a global phenomenon (Beeton, Citation2016; Macionis & Sparks, Citation2009; Vila et al., Citation2021) which has also become a reality at numerous HAs (Bąkiewicz et al., Citation2017; Hoppen et al., Citation2014; Martin-Jones, Citation2014). Interestingly, since film-induced tourism can influence the viewers’ destination and visitation choice (Chen, Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2019), the possibility for HAs to feature in potentially popular and widely viewed films has also become one of the routes to ensuring that these meet their commercial objectives and promote themselves to new audiences.

Rosslyn Chapel is one of these HAs where film-induced tourism has occurred. It served not only as a backdrop in the film The Da Vinci Code but was also a part of the plot in both the actual film and the book the film was based on. It is also referred to within the various conspiracy theories as a place where the Holy Grail had potentially been hidden. What makes Rosslyn Chapel an even more unique case is the fact that this is one of the relatively few examples of a religious site where the permission was given to include the actual site in a film. This may be due to the fact that HAs face increasingly challenging and competitive operating environments with a growing need to demonstrate value and generate income, mostly commonly achieved via increasing visitor volume and spend. The visitor experience in such circumstances becomes central to the future success of HAs, which also has significant implications for managers who need deeper insights into visitor expectations in order to meet their needs (Leask, Citation2010). As contemporary approaches to the management of HAs place more emphasis on satisfying visitors than meeting the multi-layered needs of a HA as a whole (Guthrie & Anderson, Citation2010; Irimiás et al., Citation2020; Staiff, Citation2016), film-induced tourism can become a complex phenomenon to manage in practice. Namely, managers may not be sufficiently aware of a variety of impacts a film might have had on the visitors’ expectations and preferences for interpretation on site, making it very difficult to anticipate (and meet) their needs. Therefore, this qualitative study explores film-induced tourism and heritage interpretation at a HA (in this case Rosslyn Chapel) and develops data-driven taxonomies based on visitors’ own expectations and preferences for interpretation. These taxonomies, as this paper elucidates, inform recommendations for more effective heritage management practices and enhance the ability of HAs popular among film tourists to meet their own measures of effectiveness.

Previous studies which have developed interpretation based visitor taxonomies for heritage sites were conducted either at National Parks (see, for example, Stewart et al., Citation1998) or at sacred and dark tourism sites (Biran et al., Citation2011; Hughes et al., Citation2013; Nguyen & Cheung, Citation2014; Poria et al., Citation2009) and these have overlooked the influence of popular media, such as films, on visitors’ interactions with heritage interpretation. There have been only a handful of studies conducted specifically on heritage tourism and heritage interpretation in the context of film-induced tourism. These include Schofield (Citation1996) and his research regarding alternative heritage tourism in Manchester and its cinematographic images; Frost (Citation2006), who examined the historic film Ned Kelly and its impact on heritage tourism in north-eastern Victoria; and Winter (Citation2002) who was concerned with media representations of World Heritage sites, though this study was conducted in an Asian context over a decade ago. More recently, Pan and Ryan (Citation2013) conducted research, also in an Asian context, but in Hong Kong on Wing Lee Street, the setting of an award-winning film Echoes of the Rainbow, where they attempted to gain a better understanding of how media shapes the agenda in terms of conservation, as well as the process by which the film created a heightened awareness of the heritage values of this location in Hong Kong. Månsson (Citation2010), on the other hand, employing the convergence theory, conducted research at Rosslyn Chapel in 2006 and provided a useful analysis of visitors’ motivation to visit HAs that had featured in popular media products. Although these particular papers provide a valuable contribution to the academic literature on film tourism at heritage sites, these are not concerned with the popular media influence on the preferences for heritage interpretation. This paper both addresses the calls for further research in the field of heritage interpretation (e.g. see Poria et al., Citation2009; Stewart et al., Citation1998) and fills an important gap in existing research in relation to film-induced tourism, visitor expectations and heritage interpretation at HAs.

Film-induced tourism at HAs

It is now well known that popular media products such as films have a very strong pull factor that influence people's decision where to go for holiday (Månsson, Citation2010; Vila et al., Citation2021). However, while the prime purpose of film productions is usually not to promote the locations which feature in these films or to inspire post-film production visitation, these films nonetheless, in some cases, boost the awareness, profitability and attractiveness of screened locations (Kim et al., Citation2019; Riley et al., Citation1998; Teng & Chen, Citation2020). The motivation to visit film tourism locations may also not always be influenced specifically by films as visitors may also be pushed by personal factors such as prestige, ego, enhancement of self-identity (see, for example, Macionis, Citation2004; Månsson, Citation2010; Villa et al., Citation2021).

While historic and documentary films may generate an increased visitation to historic sites, thereby further contributing to an often already existent heritage tourism at these locations (Frost, Citation2006), in cases where a fiction film further popularises a HA among tourists, this form of tourism exemplifies the postmodern experience of place (Leotta, Citation2011; Schofield, Citation1996). Importantly, in such contexts, visitors’ interest in both fictional and historical narratives of a HA can co-exist (Bakiewicz et al., Citation2015). Experiences of visiting a film location can conjure up memories related to actors, events and settings (Iwashita, Citation2006) and fictional narratives can create powerful perceptions of locations which, as a result, often also become emblematic attractions (Zhang et al., Citation2016). What is more, when visiting both literary and film tourism related places, visitors can discover ‘multiple intertwined place-narratives and ultimately might acquire a sense of belonging’ (van Es & Reijnders, Citation2016).

Films such as A Knight’s Tale, The Da Vinci Code, the Harry Potter series, Alice in Wonderland, Pirates of the Caribbean and Brave have all increased visits to various HAs in the UK, including Rosslyn Chapel, Alnwick Castle, Antony House, the Old Royal Naval College and Dunnottar Castle. Busby and Klug (Citation2001) examined levels of film-induced tourism to places of historic and heritage significance and found greater levels of tourism at these sites after the film(s) release(s). Often some heritage sites become more popular among (film) tourists only because they had been featured in a film (Bąkiewicz et al., Citation2017). That said, it is important to highlight that not all films will serve as primary motivators to visit film locations and links need to be made between films and the location for a film to have an influence on visitation (Croy et al., Citation2018).

While there are many creative and meaningful modes in which such connections may be made at destinations in general (e.g. Hudson & Ritchie, Citation2006) and in the context of interpretation at HAs in particular, incorporation of imagery and footage from films within interpretation can also result in further dilemmas and practical issues, especially if the questions surrounding copyright permissions needed in such circumstances have not been considered in advance of the filming and need to be requested after the filming.

Film-induced tourism expectations and preferences for interpretation at HAs

Visitors’ engagement with interpretation, expectations, and their preferences for onsite interpretation, are of crucial significance within the overall visitation experience (Poria, Citation2010; Wilson et al., Citation2018). Interpretation tools are, therefore, an essential element in the effective management of HAs (Hughes et al., Citation2013; Leask, Citation2016). Visitors rely on interpretation for many different purposes, such as to learn about a site’s past and history (Light, Citation1995; Schaper et al., Citation2018); enhance the sense of place (Stewart et al., Citation1998; Timothy, Citation2018); experience nostalgia (Goulding, Citation2001); achieve emotional experiences in relation to their own heritage (Poria et al., Citation2009); and to enrich their knowledge (Biran et al., Citation2011).

However, visitors to HAs are not necessarily looking for a scientific interpretation of the site and its history, and an interest in history might not be a primary reason for their visit (Poria, Citation2010; Schouten, Citation1995). Visitors may, instead, be seeking a new symbolic experience of the site’s features and its past (Rahmani et al., Citation2019: Sheng & Chen, Citation2012). Easiness and fun, cultural entertainment, personal identifications, historical reminiscence, and escapism are increasingly sought by HA visitors (Sheng & Chen, Citation2012). This is especially visible at HAs where film-induced tourism has occurred alongside other types of tourism and visitation, which may create a new form of cultural landscape (Jewell & McKinnon, Citation2008) which include new narratives about the site that may go beyond its historical significance (Zimmermann & Reeves, Citation2009). As a result, the narratives within onsite interpretation are increasingly also being informed by content related to mass-media products such as films in which a HA has featured, contributing to the creation of a mediatised HA space. This phenomenon is directly related to visitors’ own expectations of interpretation (Buchmann et al., Citation2010; Connell, Citation2012; Ghisoiu et al., Citation2018; Jansson, Citation2006; Månsson, Citation2011; Mazierska & Walton, Citation2006) and their interest in interpretation, which includes both historical and in some cases fictional, or media-related, content as well as a desire to engage in individualised multidimensional experiences (Howard, Citation2003; Hughes et al., Citation2013; Poria et al., Citation2009).

Taxonomies of visitors at HAs

‘Taxonomic systems are empirically based and classify items using observable and measurable characteristics’ (McKercher, Citation2016, p. 197). The use of visitor taxonomies has, for example, also been used to develop a deeper understanding of visitors via classifying their characteristics and behaviours in creative tourism (Tan et al., Citation2014) and product development (McKercher, Citation2016). Taxonomy minimises complexity and allows us to see resemblances, dissimilarities as well as relationships between studied tourism phenomena (Nickerson et al., Citation2013). To date, only a relatively small number of studies have developed taxonomies of visitors at HAs.

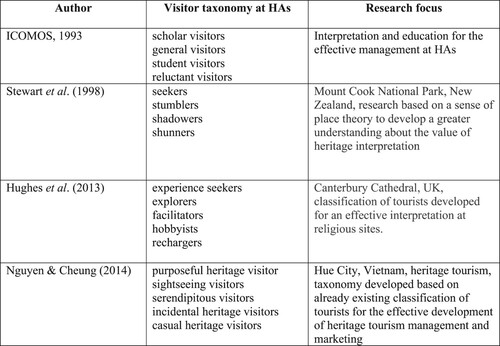

Stewart et al. (Citation1998) divided visitors into four categories in relation to their use of interpretation: ‘seekers,’ ‘stumblers,’ ‘shadowers,’ and ‘shunners.’ ‘Seekers,’ for example, were actively looking for information to learn more about the visited site so they appreciated various forms of interpretation which highlighted different aspects of the place. The ‘shunners’, on the other hand, did not want to engage in any form of interpretation so they either tried to avoid it or were passive and ignored it. Another taxonomy to improve the interpretation and educational experiences of visitors was proposed by ICOMOS (Citation1993). This particular taxonomy identified four types of visitors such as scholar visitors who are knowledgeable about the history of the visited heritage site; general visitors who have heard about the site but do not know much about it; student visitors; and, finally, reluctant visitors on a package tour who are not interested in the history of the site but are instead looking for entertainment.

More recently, a study by Hughes et al. (Citation2013) revealed that a majority of visitors to built HAs were ‘experience seekers’, who visited because the site was famous; thus they considered it as an important destination to visit. Other types of visitors included ‘explorers,’ ‘facilitators,’ ‘hobbyists,’ and ‘rechargers’ (Hughes et al., Citation2013, p. 212). Facilitators, for example, differed from a hobbyist in that they were socially motivated, whereas hobbyist visitation to the site was related to their hobby or profession. Recharges, on the other hand, visited due to more spiritual reasons. Nguyen and Cheung (Citation2014) identified five categories of heritage visitors such as ‘purposeful heritage visitors,’ ‘sightseeing visitors,’ ‘serendipitous visitors,’ ‘incidental heritage visitors,’ and ‘casual heritage visitors.’ For the first category of visitors, heritage was the primary motivation to visit the site and similarly for the second category, however, the second type of visitors have not been as engaged in the site as the first type. Interestingly, although serendipitous visitors had a deep experience of the site, heritage was not a significant factor for them in their decision to visit. For incidental visitors, heritage was not an important factor to see the site. presents a Table with previously developed taxonomies of visitors at HAs.

Therefore, while a number of visitor taxonomies for HAs have already been developed, visitor taxonomies at HAs popular among film-tourists have not been sufficiently focused on, which in itself represents a challenge for the management of film-tourism at heritage sites which are further popularised through their inclusion in films and other media productions. The taxonomy developed in this paper thus sheds a new light on heritage interpretation, as in contrast to the previous mentioned studies, it examines the influence of popular media such as films on visitors’ expectations and preferences for an on-site interpretation at a very unique heritage site.

Rosslyn Chapel

Rosslyn Chapel, located seven miles outside Edinburgh, is a Category A listed building and Scheduled Ancient Monument (Rosslyn Chapel, 2014). It is a very unique HA as it is also a working church that had featured in The Da Vinci Code film thus Rosslyn Chapel, is known as The Da Vinci Chapel (Rosslyn Chapel, 2014). Rosslyn Chapel together with Temple church, are the only churches that had given a permission for The Da Vinci Code to be filmed at the actual site, and other heritage sites of religious importance had refused permission for filming. However, its formal name is the Collegiate Chapel of St Matthew. It is a fifteenth-century church in the village of Roslin, founded in 1446 by Sir William St. Clair. Rosslyn Chapel, due to its long history, unique carvings, the distinction of the St. Clair family and its possible connections with the Knights Templar, or Freemasonry, as well as other stories surrounding the church and the vault, has become a historical mystery (Walker & Trust, Citation2011).

There is endless speculation on what is beneath the Rosslyn Chapel’s underground chamber. This is mainly due to the theories about the Holy Grail, Mary Magdalena, and the gospels created in a plot in Dan Brown’s book and subsequently the identically titled film, The Da Vinci Code (Clewley, Citation2006). In the book and film, Rosslyn Chapel is identified as the place where the Holy Grail is hidden, prompting visitor numbers to increase significantly, and transforming the Chapel into a real pilgrimage site and a major factor in the massive increase of film tourism in Europe (UK Film Council Citation2007).

Methods

This study, underpinned by a constructivist paradigm, introduces a taxonomy of visitors based on their preferences for interpretation at Rosslyn Chapel. The taxonomy, as opposed to typology, is based on empirical data without prior conceptualisation (McKercher, Citation2016; Young et al., Citation2007), and the findings draw on twenty-three semi-structured interviews with Rosslyn Chapel visitors. The interview questions were informed by the wider research project, which focused on heritage interpretation and management challenges at HAs popular among film tourists, relevant academic literature on film-induced tourism, visitor expectations, engagement and preferences for heritage interpretation, as well as the nature of this particular HA.

Interviews with visitors to Roslyn Chapel were carefully designed, and a pilot study was also completed in order to assess the appropriateness of the initial themes and questions and to enhance the quality and efficiency of the subsequent study (Lancaster et al., Citation2004). The pilot study showed that while the vast majority of themes and questions were suitable, some minor adjustments were still needed. These included minor adjustments to ensure ample freedom in answering the questions was provided for interviewees during the actual interview and that suitable introductory and concluding themes were included.

The initial interviews were conducted on the grounds of Rosslyn Chapel during both weekdays and weekends over a three-week period in July and August 2013. The research participants were both UK and international visitors, and along with conducting interviews during different times of the day, this approach of interviewing both UK and international visitors allowed for a better understanding of visitors’ experience with heritage interpretation from a variety of visitors. While the majority of interviewed visitors were in their 40s, there were also 5 visitors in their 30s, as well as 5 in their 20s, 4 were in their 50s, and 1 was in his 60s. Most of the interviewed visitors were from the UK, with the international visitors who were interviewed being from Spain, India, Germany, Sweden, and USA. In terms of gender, 10 male and 13 female visitors were interviewed.

As a qualitative study may be unpredictable, and researchers can be uncertain what ‘twist and turns’ the research may take (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008, p. 146) it may be difficult for researchers to set a target sample size in advance. This being the case, the lead author conducted interviews with visitors until the theoretical saturation point was reached (Crang & Cook, Citation2007). In other words, the data were being gathered until the process had reached the point where new data did not add anything significant to the research. As per Corbin and Strauss’s (Citation2008) recommendation, each category and theme was explored in some depth, and various dimensions and properties were identified under different conditions prior to a decision on saturation being made.

The taxonomy was developed directly from the data by conducting inductive empirical to conceptual interpretative analysis (Nickerson et al., Citation2009). This allowed both immersion in the data and familiarity with the depth of the content (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) as well as identification of taxonomies from data rather than theory. The interviews were transcribed which allowed not only greater familiarisation with the data, but also active creation of meanings and ongoing development of themes and categories (Lapadat & Lindsay, Citation1999). All transcripts were imported to NVivo 9 for the process of coding. The coding process played an essential role in the analysis stage, as it allowed the identification of thoughts, concerns and issues of each research participant. As would be expected within a study that relies on the constructivist paradigm, in aiming to contextualise the findings, the discussions in the following section at times rely on direct quotes from the actual interviews.

Findings

The Da Vinci Code and its influence on visitors’ preferences for heritage interpretation

Visitors to Rosslyn Chapel were experiencing the site through different ‘lenses,’ including both the fictional and factual or historic aspects of the Chapel itself. Those visitors who had a significant interest in the history of the Chapel were mainly interested in the architecture and the meanings of the carvings – information related to history or conservation work. From conversations with visitors, however, it was evident that some visitors were still looking for narratives related to The Da Vinci Code. These visitors wanted to know which parts of the site were filmed inside the Chapel and some visitors even expected the guides to run them through what actually happened in the book and/or the film. Some visitors were also curious to know whether Tom Hanks was really at the Chapel and if the guides or someone from the management team had met him. Clearly, the site’s exposure in the film had, to some extent, built visitors’ expectations of what can, or should be, seen and experienced at Rosslyn Chapel, which further influenced their preferences for the content of interpretation available at the site and the way they engaged with them.

These findings highlight a clear link within relationships between the media products and visitors’ expectations of locations which featured in these media products (see for example: Croy, Citation2010). As Beeton (Citation2016) and Mazierska and Walton (Citation2006) argue, places represented in films might become detached from their initial meaning and historical significance. A place represented through the film or the book acquires new narratives which may indeed go beyond historical significance (Zimmermann & Reeves, Citation2009) as visitors influenced by the film or the book become keen to engage with these, in some cases fictional, narratives when visiting the site. What is more, these findings are consistent with those of Smørvik (Citation2021), who also confirmed that people visiting the religious sites do not necessarily come for religious reasons; thus, their interest in onsite interpretation will be based on their non-religious motives. This was also the case for Rosslyn Chapel, as illustrated in the discussion of taxonomies below, as some visitors to the Chapel were more interested in these fictional Da Vinci Code-related narratives, than the historical narratives which were rooted in the site’s past and its historical and religious significance.

Looking for The Da Vinci Code signs

The conversation with visitors revealed that some of the visitors actively looked for signs related to the book or the film. For those visitors, Rosslyn Chapel was a place where the action of The Da Vinci Code was set. This type of visitor was thus not concerned about the Chapel as a significant heritage site or as a church, but instead, they were interested in all aspects related to the associated fictional narratives from The Da Vinci Code. From the conversation with Tom, for example, it became apparent that during his visit he wanted to be reminded about the context in which Rosslyn Chapel was portrayed in the book. In Tom’s view, other similar attractions do not have the same ‘wow’ factor:

Tom (mid-thirties from New Jersey): You are at the place, the place associated with the book. When you visit similar places, you don’t really get the same wow factor. In here you look for signs depicted in the book like the Holy Grail, the pointer which shows you where Holy Grail is hidden. All of this makes the place very fascinating.

Juray (from Slovakia, living in Oxford, early-thirties): During the talk I was waiting for the part about The Da Vinci Code, you know, I was waiting for it because after the film everyone found out about it and before it was here maybe 30,000 people and after the film four times more.

Alano, for example, was another visitor who wanted to see The Da Vinci Code signs and even had an idea what he would have liked to have seen. He suggested providing an information board that would explain The Da Vinci Code association with the Chapel:

Alano (mid-twenties from Valencia): Well, I expected to see some information but not to a great extent just to fulfil the curiosity […] maybe an information board with pictures, explaining that they were filming here.

Thus, clearly, this type of visitors were actively looking for interpretation based on The Da Vinci Code, but not necessarily the one based on the site’s history. These visitors, during their visit, were trying to relate everything to the place that they had read about in the book and that they had been exposed to in the film. They were visiting Rosslyn Chapel because they simply could not experience the same association at other sites, as they had not featured in popular media products which they were aware of. These particular visitors were looking for additional information about the site which was directly related to The Da Vinci Code book and film. Their engagement with the site and interpretation methods was, to a large extent, mediated by the books and films. Given the particular behaviour of this group, these visitors can therefore be described as Vigorous Followers.

Significance of built heritage and history

There were also visitors who did not want the Chapel to be associated with the book or the film and who did not, therefore, want to see any signs or information boards in the Chapel that would include references to The Da Vinci Code. For them, the building itself had a distinct historical and religious significance, and they wanted it to be solely associated with the history of the Chapel and not with the book and the film narratives. Thus, for these visitors, the site was more about the history than the book or film. Interestingly, though, these visitors were not against such an association being made in the visitor centre, which they considered to be a place detached from the Chapel’s significance and history. Although their visit was not motivated by The Da Vinci Code, as some of them emphasised during the interview, some still expected to find some association at the site and believed that such a connection as Eric, one of the visitors stated, could be included in an overall interpretation of the Chapel. However, in the view of these visitors, such association should not appear inside the Chapel but rather at the visitor centre. For example, Eric (from Edinburgh, in his late fifties) said:

Eric (from Edinburgh, late-fifties): I didn’t expect to see anything like that, not in the Chapel for sure. Maybe in the visitor centre, yes, but not here at the Chapel. It would be maybe good to have something in a visitor centre just to sell it as a tourist attraction, well, you know, you are here at the place where the action has been set and then you start remembering the things from the book and film and that just brings the place to the life, it gives more meat to the bones. So, yes, it could be a good idea to have something related to the book to be reminded. I may even read Dan Brown now, although I don’t think he is a very good writer. The visit at the Chapel kind of persuades me to read it.

The historical side of the Chapel as ‘a place of history about historical moments’ seemed to be an important part of another visitor’s experience at the site. Similarly, to Eric, Ahmed (from India, lives in London, early thirties) did not want to see The Da Vinci Code connection in the Chapel. In addition, he thought the more fictional and imaginary narratives related to the site should only be seen in the visitor centre, so as not to affect the experience of visiting a fifteenth-century historic building:

Lead Author/Interviewer: You said you watched the movie and you enjoyed it so did you want to see some kind of association with The Da Vinci Code in here?

Ahmed (from India, lives in London, early thirties): I would have been disappointed if I had seen something like that in here. It is place of history about historical moments, not a movie set.

Lead Author/Interviewer: So you are satisfied with the lack of information related to the film?

Ahmed: Well, I think that in a visitor centre it would be fine because it’s outside and doesn’t affect the Chapel but once you enter here it’s different and I wouldn’t like to see anything associated with book or film. I wouldn’t mind if it was something like that in a visitor centre though.

Lead Author/Interviewer: Do you have any idea what would you like to see there in relation to the film?

Ahmed: Maybe a rolling film, you know, of the last scene that features the Chapel and some text going at the bottom just to give people the background. Not everyone remembers the film so something like that would give people something to talk about once they go back. They would say, ‘Oh, we were at the Chapel which was in that movie’.

In both Eric’s as well as Ahmed’s views any fictional and imaginary references to The Da Vinci Code film and book in the actual Chapel would negatively affect the experience of visiting a fifteenth-century historic building. Thus, these visitors would not expect to see the association with the book or the film in the Chapel but were not against such an association being made in the visitor centre. Interestingly, their visit also resulted in a willingness to learn more about The Da Vinci Code so that they could then tell friends and family that they had been not to any historic Chapel but to the particular Chapel that featured in The Da Vinci Code Hollywood film. That said, for these visitors, the historical side of the Chapel and the building itself was an important part of their experience (Hughes et al., Citation2013; Nguyen & Cheung, Citation2014)); however, they were also keen to learn more about The Da Vinci Code and thus this particular group of visitors could be described as Curious Investigators.

Amalgamation of history and fiction

Interestingly, for some visitors, the historical aspects of the Chapel were important, but they also perceived the fictional narratives from the book and the film to be of equal significance. For these visitors, the film was ‘part of its history now,’ so they felt it could be included in the overall interpretation of the site. Through their engagement with interpretation, these visitors sought a blend of references to both fictional and historical narratives of the site. Sonia from Dumfries in Scotland (in her early forties), for example, told about her reading of the book and watching the film. She knew about the Chapel before but only decided to visit after watching The Da Vinci Code film. For Sonia, the film clearly played a significant part of her experience; thus when visiting, she was looking for signs and images related to it. She did not think that such association would have been inappropriate or harmful for the Chapel. In her view, the managers should make that connection with the film’s story, as for her it became a part of its history now. She also pointed out though that this was not the only story and that other narratives should also feature in the overall interpretation of the site:

Sonia (early forties from Dumfries, Scotland): Well, I don’t think that it would do any harm if they had mentioned that it was a Hollywood film filmed here, because it is part of its history now, but I don’t think that it should be based on that story only.

It seemed that these visitors required a combination of history and fiction to help them fully enjoy the site. They also did not feel the need to make a distinction between the Chapel’s history and fictional narratives from the book and the film. Through their engagement with the interpretation at the site, these visitors were effectively looking for an amalgamation of both the history of the Chapel and its value as a heritage site and the fictional narratives from The Da Vinci Code film. This being the case, these visitors could be described as Versatile Explorers.

Connecting with the past, heritage, and history

A significant number of visitors, however, wished to explore only the Chapel’s history, to learn more about the carvings, and were seeking to get closer to the past, indicating that their engagement with the site would be based on interpretation related to historical aspects of the site only. Indeed, the historical aspects of the Chapel and ‘knowing the right things about it’ were significant parts of visitors’ expectations of the heritage interpretation offered at the site. Thus, a significant number of visitors did not want to see any connection made with The Da Vinci Code book and film and were interested solely in the historical aspects of the Chapel. This is what Jennifer from Glasgow said when asked whether she expected to see interpretation related to The Da Vinci Code:

Jennifer (early-forties, from Glasgow, lives in London): Not at all, no! I would prefer it didn’t have a connection with The Da Vinci Code. If I had come here and it was like a theme park I would have wanted to walk straight out and have my money back […] There is plenty of visitor attractions that are like the theme parks, unreal, this is something that has been real, it’s been run for hundreds of years. Something that happened over the last ten years shouldn’t take over the whole history which is involved in it.

Similarly, David a visitor from Shetland (in his mid-fifties), for example, was very emotional when talking about his visit at Rosslyn and said that when he was inside, he even described the enjoyment of experiencing the smells of the place. For him, the actual attraction is the feeling of being at the Chapel. As he in his own words describes it:

David (mid-fifties, from Shetland): I watched the film once but I do not think it influenced my expectations. When I was inside, I even enjoyed the smells of the place and the feeling of the place more than the intricacy of it. The legends and mysteries are very fascinating but just the feeling of being here, sitting here, that's what I appreciate you know.

Lead Author/Interviewer: What is so special about being here then?

David: It is the history of the place that makes you feel like that, you are here and start imagining people coming in and out through the centuries, and how little or how much had the building changed. It’s like a bigger picture so it's not just the site you know. You are going back in time for the whole of Scotland.

Lead Author/Interviewer: So you did not expect to see any relation to the book or film?

David: No I didn't, I wouldn’t have been interested anyway. You know the film is one thing, the site another. This place is not about the film, it is about the building and the history of the place, and the film is at the end of the list of things which should be said about that place. I can see that it would have applied to some people who like to follow trailers and looking for adventure but I am not that kind of person.

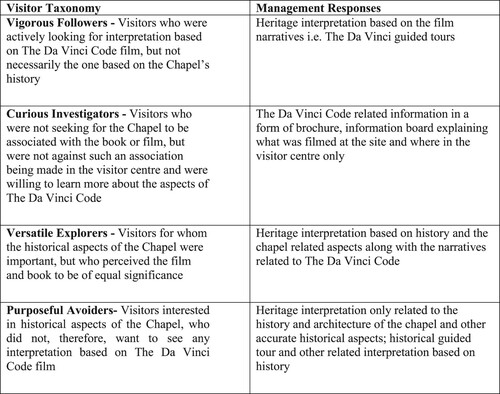

Visitor taxonomy at Rosslyn Chapel

As it became apparent, visitors’ engagement with the site and their preferences for heritage interpretation at Rosslyn Chapel were influenced by The Da Vinci Code, with a number of visitors interested in such a connection. These findings therefore indicate that the connection between the film and book narratives and the site inevitably influenced preferences for interpretation among visitors, which varied between on the one end of the spectrum of preferences for historically based interpretation (in the case of Purposeful Avoiders) and on the other for The Da Vinci Code based interpretation (in the case of Vigorous Followers). That said, the nature of Rosslyn Chapel as a religious heritage site and its associated historical significance was nonetheless given greater significance by the majority of interviewed visitors.

These findings highlight that visitors to Rosslyn Chapel developed their connections to the site not necessarily only based on its close association with The Da Vinci Code but also because of the other aspects of the Chapel, including its rich history, admiration for the craftsmanship, their own personal interest in masonry, art or unusual architecture and carvings, as well its religious significance. Popular media in general, and film in particular, is therefore instrumental in the creation of people’s perceptions and expectations of the place visited, especially at sites associated with a film story. This connection creates an emotional experience, which is further linked with the location (Irimiás et al., Citation2020; Tooke & Baker, Citation1996; van Es & Reijnders, Citation2016). Different people will nonetheless have different preferences for interpretation (Poria et al., Citation2009) and this was also evident at Rosslyn Chapel – hence four different types of visitors were identified through a data-driven taxonomy according to their preferences for and engagement with existing heritage interpretation at the site:

Vigorous Followers – Visitors who were actively looking for interpretation based on The Da Vinci Code film, but not necessarily the one based on the Chapel’s history

Curious Investigators – Visitors who were not seeking for the Chapel to be associated with the book or film, but were not against such an association being made in the visitor centre and were willing to learn more about the aspects of The Da Vinci Code

Versatile Explorers – Visitors for whom the historical aspects of the Chapel were important, but who perceived the film and book to be of equal significance

Purposeful Avoiders – Visitors interested in historical aspects of the Chapel, who did not, therefore, want to see any interpretation based on The Da Vinci Code film

The significance of taxonomies is that they offer ‘research foundations in the form of a common domain language in which problems and their solutions can be defined and explored’ (Nickerson et al., Citation2009, p. 1138). This particular taxonomy of visitors at the Rosslyn Chapel provides a more holistic approach to knowledge development with regards to the literature on heritage tourism in general and visitors’ preferences for interpretation at film-induced tourism heritage attractions in particular. It helps managers gain an in-depth insight into heritage tourism in general and film-induced tourism at this heritage site in particular, thereby contributing to a greater understanding of the popular media products’ influence on visitor expectations. These are significant in that this knowledge can be relied on in the process of developing the offer of on-site interpretation following its further popularisation among film tourists. Therefore, a taxonomy of this kind can be an effective starting point in developing an ontology of a domain (McKercher, Citation2016) as it helps to better understand the structure as well as the elements of HAs featured in popular media products, which in turn further assists managers in developing a more effective strategy, policy and planning for the site, especially in as far as on-site interpretation is concerned.

Thus, HAs could rely on a taxonomy to rethink the current utility of the heritage interpretation and adapt it to manage new popular media or film-induced visitor expectations and use it to achieve the balance between the newly acquired, often fictional, meanings a site acquired through popular media or film exposure and their actual historical narratives and significance. The taxonomy in itself, as demonstrates, can enable managers to develop different angles of interpretation for each category of visitors. For example, for visitors who do not wish the site to be associated with the film, the book it was based on or other types of popular media through which it was further popularised, as, in the case of Purposeful Avoiders, the site could provide specific guided tours only on history.

Managers, however, should also think of visitors who are interested in both the history and fictional narratives and references to the film, the book it was based on or other types of popular media such as the Versatile Explorers and Curious Investigators discussed in this paper. This could be done through a development of guided tours similar to a guided tour already in place at Rosslyn Chapel, where guides incorporate elements of history with information on the film. In that way, the balance is achieved, and different types of visitors are satisfied.

The significance of a taxonomy such as the one developed in this paper therefore lies in furthering the knowledge not only with regards to film-induced tourism's influence on visitors’ expectations at a particular site but also the subjective multiplicity of the visitor’s experiences in relation to heritage interpretation. In addition, a taxonomy highlights the additional role of heritage interpretation at HAs, which is intended to be not only a medium that conveys the narratives related to the history of the place or a tool to manage negative impacts of tourism, but also a tool that can be central in providing exceptional holistic visitor experience.

Discussion

Previous studies have stated that media products such as films largely influence peoples’ behaviour in terms of where to go for holiday (Busby & Klug, Citation2001; Teng & Chen, Citation2020; Wen et al., Citation2018). These have also revealed the films’ influence on expectations of the visited location. (Connell, Citation2012; Månsson, Citation2011; Tzanelli, Citation2013). This study confirmed these findings while at the same time revealing that media products also have an impact on how visitors engage with the HA, and in particular, with on-site heritage interpretation.

This paper is also in line with the views of Urry and Larsen (Citation2011), as well as Gyimothy (Citation2010), who argue that the tourism spaces are mediatised and develops this thought further, demonstrating how visitors’ preferences amongst different types of interpretation were mediatised by media products, such as The Da Vinci Code book and film. The findings of this study are also consistent with the findings of Zimmermann and Reeves (Citation2009) as they suggest that media products can indeed create new narratives at HAs, though the findings also show that the media representations do not necessarily diminish its historical significance, as some studies argued in the past (Beeton, Citation2016; Mazierska & Walton, Citation2006). The findings of this paper also are in line with the findings of Smørvik (Citation2021), who suggested that visiting religious sites is not exclusively based on religious motives, but there are many other non-religious factors. This research, however, takes the discussion further by revealing the visitors’ preferences with interpretation available on-site at a very unique religious site that serves as a working church, important heritage attraction and film location.

That said, the taxonomies discussed in this paper identify not only visitors’ preferences but also engagement for heritage interpretation. These taxonomies highlight the fact that different visitors wish to rely on different aspects of the content within heritage interpretation to facilitate their own unique experiences at HAs, which at Rosslyn Chapel include varying degrees of emphasis between The Da Vinci Code related and historical narratives of the site. These taxonomies also highlight the fact that visitors at Rosslyn Chapel are heterogeneous (see also Stewart et al., Citation1998), and that their visits are rooted in performative and interactive encounters (see also Selby, Citation2010), and, influenced by the site’s attributes and the individual’s own cultural background and perceptions (see also Poria et al., Citation2009). These findings are also consistent with those of Chronis (Citation2008), who stated that mediatised places provide signs which contribute to the anticipated consumption and to the construction of the actual experience.

These taxonomies and their emphasis on varying degrees of interest in The Da Vinci Code related and historical narratives, are also consistent with Poria (Citation2010), Prentice (Citation1993) and Sheng and Chen (Citation2012), all of whom argued that, although built heritage sites have become popular visitor attractions, the reasons for people visiting these are not exclusively related to their rich history and significance. Therefore, visitors at HAs including those with an interest in The Da Vinci Code related narratives and interpretative content do indeed seek, as Poria et al. (Citation2009) highlight, multidimensional experiences. These experiences, it is important to note, will differ from one individual visitor to another and will at least be partly determined by the range of possibilities, via interpretation, offered to visitors to actively create their own unique and personalised linkages to either the history or the popular media product which had further popularised the HA.

Since existing taxonomies had not taken into account the influence of popular media products on visitor preferences for interpretation at heritage sites, this research makes a distinctive contribution to the growing literature on film-induced tourism. The development of this taxonomy has implications for the greater understanding of the media products’ influence on visitors’ preferences for heritage interpretation offered at HAs where film-induced tourism occurred alongside other types of tourism and visitation. This contributes a new perspective to both heritage interpretation and film-induced tourism theory in terms of providing evidence of various forms of visitor engagement with heritage interpretation at Rosslyn Chapel. This is relevant due to the growing significance of heritage interpretation as an essential element of effective management practices at HAs, and especially at HAs which have become popular among film tourists whose expectations, as this paper has demonstrated, can differ from that of other visitors.

Conclusions

Given the importance of interpretation within effective management practices at HAs and the growing popularity of film-induced tourism at some of these sites, this paper has sought to address the gap in existing knowledge by highlighting the value of visitor taxonomies in understanding visitor preferences for interpretation at (film-induced) HAs and in so doing contributing to more effective management practices. As highlighted in this paper, although visitors’ preferences for heritage interpretation clearly change following the popularisation of a HA such as Rosslyn Chapel among film tourists, these preferences are not always necessarily reflected in the actual interpretation offered at the site. This has important implications for heritage interpretation, as there is a clear need to adopt new, more responsive approaches to heritage management at HAs, in general, and those involved in film-induced tourism in particular. In doing this and improving the visitors’ on-site experiences, HA managers could improve the overall effective management of the site through achieving their specific measures of effectiveness – visitor satisfaction, revenue generation or authenticity.

Further research could take these debates further to also include a greater understanding of the additional film-related activities visitors at HAs popular among film tourists undertake alongside their engagement with interpretation content to construct their experience. These film-related activities could include but are not limited to film-related photographic practices, re-enactments of film scenes, film-related walks around the site as well as reading, reflecting or talking about the film while visiting the site and other less common activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Justyna Bąkiewicz

Dr Justyna Bakiewicz is Lecturer in Tourism Management at Edinburgh Napier University, UK. She holds a PhD in Tourism Studies and her current research interests, publications as well as academic and industry conference presentations focus on heritage tourism management, heritage interpretation and film-induced tourism. Her most recent research project explored film-induced tourism implications for heritage attractions and the role of heritage interpretation as a valuable tool for effective heritage tourism management practices.

Anna Leask

Anna Leask (PhD) is a Professor of Tourism Management at Edinburgh Napier University, UK. Her teaching and research interests combine and lie principally in the areas of visitor attraction management and heritage tourism management. Recent research has focused on how visitor attractions and hotels can engage with Generation Y and Traditionalist visitors, with primary research being conducted in the UK and Hong Kong. She has co-edited several textbooks, including Managing Visitor Attractions (2022, forthcoming). She is on the Editorial Board for four international tourism journals and has published in Tourism Management, International Journal of Tourism Research, Current Issues in Tourism, in addition to publishing a range of case studies, book chapters, articles, and practitioner papers.

Paul Barron

Paul Barron (PhD) is a Professor of Hospitality and Tourism Management at Edinburgh Napier University, UK. His teaching responsibilities lie in the area of research methods and research philosophy and research interests are focussed on higher education new and emerging markets for the hospitality and tourism industry. He has authored over 50 articles in the fields of hospitality and tourism and served as Executive Editor of The Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management for six years. He is currently Hospitality Subject Editor for the Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education.

Tijana Rakić

Dr Tijana Rakić is a Principal Lecturer at the School of Business and Law at the University of Brighton, UK. She holds an interdisciplinary PhD in Tourism Studies, and her research interests and publications predominantly lie in visual research methods, tourism’s visual culture, narratives of travel and tourism, and the relationships between heritage, tourism, and national identity. She has co-edited several book-length publications, including An Introduction to Visual Research Methods in Tourism (with D. Chambers, 2012, Routledge), Narratives of Travel and Tourism (with J. Tivers, 2012, Ashgate), Travel, Tourism and Art (with J. – A. Lester, 2013, Ashgate), and Tourism Research Frontiers (with D. Chambers, 2015).

References

- Araújo Vila Noelia, Brea, J. A. F., & de Carlos, P. (2021). Film tourism in Spain: Destination awareness and visit motivation as determinants to visit places seen in TV series. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(1), 100135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.100135

- Bakiewicz, J., Leask, A., Barron, P., & Rakić, T. (2015). Exploring film-induced tourism: Implications for on-site heritage interpretation. In M. Kozak, & N. Kozak (Eds.), Destination marketing: An international perspective (pp. 97-108). Routledge: Routledge Advances in Tourism.

- Bąkiewicz, J., Leask, A., Barron, P., & Rakić, T. (2017). Management challenges at film-induced tourism heritage attractions. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(4), 548–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1303540

- Beeton, S. (2016). Film-induced tourism. Channel View Publications.

- Biran, A., Poria, Y., & Oren, G. (2011). Sought experiences at (dark) heritage sites. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 820–841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.12.001

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buchmann, A., Moore, K., & Fisher, D. (2010). Experiencing film tourism: Authenticity & fellowship. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 229–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.09.005

- Busby, G., & Klug, J. (2001). Movie-induced tourism: The challenge of measurement and other issues. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7(4), 316–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670100700403

- Chen, C. Y. (2018). Influence of celebrity involvement on place attachment: Role of destination image in film tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1394888

- Chronis, A. (2008). Co-constructing the narrative experience: Staging and consuming the American Civil War at Gettysburg. Journal of Marketing Management, 24(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1362/026725708X273894

- Clewley, M. (2006). Film tourism: The ultimate tourism advertisement: The Da Vinci Code case study. VisitBritain.

- Connell, J. (2012). Film tourism – evolution, progress and prospects. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1007–1029. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.008

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Strategies for qualitative data analysis. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3.

- Crang, M., & Cook, I. (2007). Doing Ethnographies. Los Angeles, London: Sage.

- Croy, W. G. (2010). Planning for film tourism: Active destination image management. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530903522598

- Croy, W. G., Kersten, M., Mélinon, A., & Bowen, D. (2018). Film tourism stakeholders and impacts. In C. Lundberg & V. Ziakas (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of popular culture and tourism (pp. 391–403). Oxon: Routledge.

- Frost, W. (2006). Braveheart-ed Ned Kelly: Historic films, heritage tourism and destination image. Tourism Management, 27(2), 247–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.09.006

- Ghisoiu, M., Bolan, P., Gilmore, A., & Carruthers, C. (2018). Conservation” and co-creation through film tourism at heritage sites: An initial focus on Northern Ireland. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 1(27/28), 2125–2135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd.v1i27/28.10457

- Goulding, C. (2001). Romancing the past: Heritage visiting and the nostalgic consumer. Psychology & Marketing, 18(6), 565–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1021

- Guthrie, C., & Anderson, A. (2010). Visitor narratives: Researching and illuminating actual destination experience. Qualitative Market Research: an International Journal, 13(2), 110–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13522751011032575

- Gyimothy, S. (2010). Medier og Turisme. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 492–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.515412

- Heelan, C. A. (2004). Loved the book? Go there, literally, with a literary tour. [online]. Retrieved January 1, 2012, from http://www.frommers.com/articles/2523.html

- Hoppen, A., Brown, L., & Fyall, A. (2014). Literary tourism: Opportunities and challenges for the marketing and branding of destinations? Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.12.009

- Howard, P. (2003). Heritage: Management, interpretation, identity. Continuum.

- Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. (2006). Promoting destinations via film tourism: An empirical identification of supporting marketing initiatives. Journal of Travel Research, 44(4), 387–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506286720

- Hughes, K., Bond, N., & Ballantyne, R. (2013). Designing and managing interpretive experiences at religious sites: Visitors’ perceptions of Canterbury Cathedral. Tourism Management, 36, 210–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.022

- ICOMOS, & WTO. (1993). Cultural tourism – tourism at world heritage sites: The site manager’s handbook (2nd ed.). UN.

- Irimiás, A., Mitev, A., & Michalkó, G. (2020). The multidimensional realities of mediatized places: The transformative role of tour guides. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1748884

- Iwashita, C. (2006). Media representation of the UK as a destination for Japanese tourists: Popular culture and tourism. Tourist studies, 6(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797606071477

- Jansson, A. (2006). Specialized spaces: Touristic communication in the age of hyper-space-biased media. Aarhus Universitet.

- Jewell, B., & McKinnon, S. (2008). Movie tourism – A new form of cultural landscape? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 24(2-3), 153–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802092650

- Kim, S., Kim, S., & Han, H. (2019a). Effects of TV drama celebrities on national image and behavioral intention. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1557718

- Kim, S., Kim, S., & King, B. (2019b). Nostalgia film tourism and its potential for destination development. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(2), 236–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1527272

- Lancaster, G. A., Dodd, S., & Williamson, P. R. (2004). Design and analysis of pilot studies: Recommendations for good practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 10(2), 307–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x

- Lapadat, J. C., & Lindsay, A. C. (1999). Transcription in research and practice: From standardization of technique to interpretive positionings. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049900500104

- Leask, A. (2010). Progress in visitor attraction research: Towards more effective management. Tourism Management, 31(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.09.004

- Leask, A. (2016). Visitor attraction management: A critical review of research 2009–2014. Tourism Management, 57, 334–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.015

- Leotta, A. (2011). Touring the screen: Tourism and New Zealand film geographies. Intellect.

- Light, D. (1995). Visitors’ use of interpretive media at heritage sites. Leisure Studies, 14(2), 132–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02614369500390111

- Macionis, N. (2004). Understanding the film-induced tourist. In W. Frost, W. G. Croy, & S. Beeton (Eds.), Proceedings of the international tourism and media conference (pp. 86e97). Melbourne, Australia: Tourism Research Unit, Monash University.

- Macionis, N., & Sparks, B. (2009). Film-induced tourism: An incidental experience. Tourism Review International, 13(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/154427209789604598

- Martin-Jones, D. (2014). Film tourism as heritage tourism: Scotland, diaspora and The Da Vinci Code (2006). New Review of Film and Television Studies, 12(2), 156–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2014.880301

- Mazierska, E., & Walton, J. (2006). Tourism and the moving image. Tourist Studies, 6(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797606070583

- Månsson, M. (2010). Negotiating authenticity at Rosslyn Chapel. In B. TimmKnudsen & A. M. Waade (Eds.), Re-investing authenticity (pp. 169–180). Bristol: Channel View Publications.

- Månsson, M. (2011). Mediatized tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1634–1652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.02.008

- McKercher, B. (2016). Towards a taxonomy of tourism products. Tourism Management, 54, 196–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.008

- Nguyen, T. H. H., & Cheung, C. (2014). The classification of heritage tourists: A case of Hue city, Vietnam. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2013.818677

- Nickerson, R. C., Muntermann, J., Varshney, U., & Isaac, H. (2009). Proceedings of the European Conference in Information Systems, Verona, 1138–1149.

- Nickerson, R. C., Varshney, U., & Muntermann, J. (2013). A method for taxonomy development and its application in information systems. European Journal of Information Systems, 22(3), 336–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.26

- Pan, S., & Ryan, C. (2013). Film-induced heritage site conservation: The case of Echoes of the Rainbow. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 37(1), 125–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348011425497

- Poria, Y. (2010). The story behind the picture: Preferences for the visual display at heritage sites. In E. Waterton & S. Watson (Eds.), Culture, heritage and representation: Perspectives on visuality and the past (pp. 217–228). Ashgate.

- Poria, Y., Biran, A., & Reichel, A. (2009). Visitors’ preferences for interpretation at heritage sites. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328657

- Prentice, R. (1993). Tourism and heritage attractions. London; New York: Routledge.

- Rahmani, K., Gnoth, J., & Mather, D. (2019). A psycholinguistic view of tourists’ emotional experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 192–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517753072

- Riley, R., Baker, D., & Van Doren, C. S. V. (1998). Movie induced tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(4), 919–935. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00045-0

- Schaper, M. M., Santos, M., Malinverni, L., Berro, J. Z., & Pares, N. (2018). Learning about the past through situatedness, embodied exploration and digital augmentation of cultural heritage sites. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 114, 36–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.01.003

- Schofield, P. (1996). Cinematographic images of a city: Alternative heritage tourism in Manchester. Tourism Management, 17(5), 333–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(96)00033-7

- Schouten, F. (1995). Improving visitor care in heritage attractions. Tourism Management, 16(4), 259–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00014-F

- Selby, M. (2010). People-place-past: The visitor experience of cultural heritage. In E. Waterton & S. Watson (Eds.), Culture, heritage and representation: Perspectives on visuality and the past (pp. 39–55). Routledge.

- Sheng, C. W., & Chen, M. C. (2012). A study of experience expectations of museum visitors. Tourism Management, 33(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.023

- Smørvik, K. K. (2021). Why enter the church on holiday? Tourist encounters with the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16(3), 337–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1807557

- Staiff, R. (2016). Re-imagining heritage interpretation: Enchanting the past-future. Routledge.

- Stewart, E. J., Hayward, B. M., Devlin, P. J., & Kirby, V. G. (1998). The ‘place’ of interpretation: A new approach to the evaluation of interpretation. Tourism Management, 19(3), 257–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00015-6

- Tan, S. K., Luh, D., & Kung, S. (2014). A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tourism Management, 42, 248–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.008

- Teng, H. Y., & Chen, C. Y. (2020). Enhancing celebrity fan-destination relationship in film-induced tourism: The effect of authenticity. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100605

- Timothy, D. J. (2018). Making sense of heritage tourism: Research trends in a maturing field of study. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 177–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.018

- Tooke, N., & Baker, M. (1996). Seeing is believing: The effect of film on visitor numbers to screened locations. Tourism Management, 17(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00111-5

- Tzanelli, R. (2013). Heritage in the digital era: Cinematic tourism and the activist cause. Routledge.

- UK Film Council. (2007). How film and television programmes promote tourism in the UK: Stately attraction. London: Olsberg SPI.

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. SAGE Publications.

- van Es, N., & Reijnders, S. (2016). Chasing sleuths and unravelling the metropolis: Analyzing the tourist experience of Sherlock Holmes’ London, Philip Marlowe’s Los Angeles and Lisbeth Salander’s Stockholm. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 113–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.017

- Vila, N. A., Brea, J. A. F., & de Carlos, P. 2021. Film tourism in Spain: Destination awareness and visit motivation as determinants to visit places seen in TV series. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(1): 100135.

- Walker, J., & Trust, R. C. (2011). Rosslyn Chapel … a mystery through history. Rosslyn Chapel Educational Material, 1–29.

- Wen, H., Josiam, B. M., Spears, D. L., & Yang, Y. (2018). Influence of movies and television on Chinese tourists perception toward international tourism destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 211–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.09.006

- Wilson, P. F., Stott, J., Warnett, J. M., Attridge, A., Smith, M. P., Williams, M. A., W, W. M. G., & G, M. (2018). Museum visitor preference for the physical properties of 3D printed replicas. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 32, 176–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.02.002

- Winter, T. (2002). Angkor meets Tomb Raider: Setting the scene. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 8(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1352725022000037218

- Young, C. A., Corsun, D. L., & Baloglu, S. (2007). A taxonomy of hosts visiting friends and relatives. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 497–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.12.003

- Zhang, X., Ryan, C., & Cave, J. (2016). Residents, their use of a tourist facility and contribution to tourist ambience: Narratives from a film tourism site in Beijing. Tourism Management, 52, 416–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.006

- Zimmermann, S., & Reeves, T. (2009). Film tourism: Locations are the new stars. In R. Conrady & M. Buck (Eds.), Trends and issues in global tourism 2009 (pp. 155–162). Springer.