ABSTRACT

Cultural heritage still accounts as one of the main motivations for international tourists; recent research has observed an increasing interest in the living culture of a population as well as in minority, peripheral areas. Since UNESCO recognizes oral traditions and languages as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of a population, minority languages, i.e. local languages spoken by a minority of the population, have the potential to represent an added value, differentiate the destination, and attract tourists to the area. Using the approach of David and Han (2004) and Newbert (2007), this study aims at providing a systematic, transparent and replicable review of previous contributions regarding tourism and minority languages and identifying areas that need further research. Through a detailed coding and analysis of 52 contributions, a framework was identified. Minority languages are perceived as authentic by cultural tourists and are therefore used to differentiate the tourism experiences and promote the destination. The use of elements of the cultural heritage, like languages, as promotional material, can contribute to language preservation, thus enhancing an authentic use of the language. Tourism, on the other hand, could also lead to language endangerment, risking commodifying the use of the language in tourism experiences.

Introduction

UNWTO (Citation2018) considers cultural and heritage tourism as an important motivation for tourism consumption, accounting for approximately 40% of global tourism (Richards, Citation2018). Nonetheless, recent literature has highlighted some significant changes in the type of heritage that is being presented to and consumed by tourists. For instance, cultural tourism has experienced an increasing interest in the living heritage of a population or, in other words, the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Richards, Citation2018; UNWTO, Citation2018). Over the past few decades, growing demand for unique cultural experiences in peripheral regions has also been noticed, as well as increasing attention for Indigenous and minority groups (Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011; Richards, Citation2018).

According to UNESCO (Citation2003), the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) of a population includes oral traditions and languages, both as artifacts per se and as fundamental for cultural transmission. Thus, minority languages can potentially contribute to differentiating the destination and delivering unique cultural experiences to tourists (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005; Whitney-Squire, Citation2016). The term minority languages herein is commonly understood as different from the major and official language and is often spoken by the minority of a population (Bradley & Bradley, Citation2019; Council of Europe, Citation1992; Toso, Citation2008). The topic of minority languages and tourism has been studied since the 1970s with the seminal works by White (Citation1974), who looked at language change in Switzerland, and Butler (Citation1978), who analyzed the impact of tourism development on the residents of Sleat on the Isle of Skye (Scotland).

This paper will provide a systematic, transparent and replicable review of previous contributions with regard to minority languages and tourism, following the methodological framework suggested by David and Han (Citation2004) and Newbert (Citation2007). Since previous research has not provided an in-depth review of studies on minority languages and tourism, this paper will contribute to the understanding of this particular field of research, by summarizing what has been done to date, highlighting the strength of available literature, and identifying the gaps for future research.

In the following section, the theoretical background will be described, followed by a detailed explanation of the methodological approach used. The fourth section of the paper will present the main results of the literature review. Finally, the main conclusions of this study will be drawn, including limitations, implications for practice, and suggestions for further research.

Theoretical background

Recent research has highlighted that Intangible Cultural Heritage is currently receiving growing attention from cultural tourists, who want to experience the living heritage of a population (Seyfi et al., Citation2020; UNWTO, Citation2018). According to UNESCO (Citation2003), Intangible Cultural Heritage are ‘the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage’ (p. 5). This UNWTO convention also lists some of the domains where Intangible Cultural Heritage manifests, including inter alia oral expressions and languages, as a vehicle for transmission of cultural heritage from one generation to the next. Moreover, many linguists have stressed the symbiotic relationship between the culture and the language of a population, since common behaviors, identities, and values are reflected in words, grammar, sentence structure, and common sayings (Bradley & Bradley, Citation2019; Fishman, Citation1991).

In addition, tourists are also increasingly interested in minority communities, peripheral and multilingual regions. An important line of research stressed that minority cultures, traditions, and practices are attractive to many tourists, as they seek exotic experiences, which radically differ from their everyday life and from the homogeneity caused by globalization (Butler & Hinch, Citation2007; MacCannell, Citation1976; Urry, Citation1990; Yang, Citation2011). According to Cohen (Citation2002), remote and minority areas are gaining value among tourists because of their increasing rarity.

A proper definition of the term ‘minority’ would require an entire paper on its own, as it embraces various disciplines, like anthropology, sociology, political sciences, linguistics, history, etc. (Toso, Citation2008). Two main criteria can be useful for a brief attempt to categorize a minority language. A minority language differs from the major, official and national language (Toso, Citation2008) and it includes ‘situations in which either the language is spoken by persons who are not concentrated on a specific part of the territory of the State or it is spoken by a group of persons, which, though concentrated on a part of the territory of the State, is numerically smaller than the population in this region which speaks the majority language of the State’ (Council of Europe, Citation1992). For the purpose of this research, ‘new minorities’ – i.e. groups that have recently left their country of origin for economic and political reasons and emigrated to another country – were not considered (Medda-Windischer, Citation2017; Pechlaner et al., Citation2011).

The use of the intangible cultural heritage of a population in promotional and commercial contexts, like tourism, brings about issues of sustainability and authenticity. Sustainable tourism, similarly to sustainable development, is generally meant to meet the needs of the present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs and evolves around three pillars: economy, environment, and society (Brundtland, Citation1987). To achieve this objective, all stakeholders, i.e. anyone directly or indirectly involved, need to be involved in all stages of destination development, management, and promotion (Brundtland, Citation1987). Sustainable tourism also includes Intangible Cultural Heritage, which by its nature only survives, and is thus available to future generations, if practiced daily (Kim et al., Citation2019; Madden & Shipley, Citation2012). Of course, this also includes languages: the UNESCO’s Atlas of Endangered Languages (Moseley, Citation2010) has shown that almost one-half of the languages spoken worldwide today are threatened with extinction to different degrees, including most minority languages. This means that sustainable development and sustainable cultural tourism should be linked to the preservation of languages, as it enables the continuity of language transmission and, therefore, of cultural practice (Heller, Citation2003; Whitney-Gould et al., Citation2018). Previous studies proved that, if sustainably managed, tourism can contribute to the preservation of intangible cultural heritage, including languages (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005; Lonardi et al., Citation2020).

Authenticity has long been a matter of debate in tourism-related research. Ethnic tourism, in fact, promises experiences of an authentic, unspoiled, and exotic cultural heritage (Li et al., Citation2020; Yang, Citation2011). Ironically, however, tourism can destroy this promised authenticity as it often stages cultural experiences for tourists (MacCannell, Citation1976). The presence of tourists also encourages the minority community to package and simplify their cultural heritage, so that it becomes more attractive and interesting for the tourists (Cohen, Citation2002; MacCannell, Citation1976; Pitchford, Citation1995). This process has been called culture commodification, i.e. the use of elements of the living culture of a population as commodities in fields such as advertising and tourism (Cohen, Citation1988; Heller et al., Citation2014b). Cultural elements that have been commodified can gradually lose importance for the community. Nonetheless, other studies have highlighted how culture commodification (Cohen, Citation1988) can contribute to the maintenance of that living culture (Cohen, Citation1988; De Bernardi, Citation2019). Culture commodification has been seen as a means to promote minority culture, and improve their way of life through an increased sense of identity and pride in one’s cultural background, as well as the economic potential, including employment opportunities, offered by tourism (Cohen, Citation1988; De Bernardi, Citation2019).

Issues of authenticity and commodification have been extensively discussed in the linguistic literature as well (Heller, Citation2003; Heller et al., Citation2014a). Linguistic commodification means that languages are accorded different functions than the original ones (Heller et al., Citation2014b): from being primarily a means of communication and markers of identity, they become marketable commodities (Heller, Citation2003). In tourism, (minority) languages can be used to attract tourists by creating a sense of place, representing locality, building attractions, and making souvenirs (Heller, Citation2003; Heller et al., Citation2014).

Minority languages can be perceived as more localized, territorially-bound community languages (Barakos, Citation2016) and have, therefore, the potential to offer tourists a richer, more valuable experience (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005; Whitney-Squire, Citation2016). They represent an added value to the tourism product and a pull factor for destinations since they reflect the differences between the center and the periphery and have the potential to represent locality and living traditions (Brennan, Citation2018; Heller et al., Citation2014a). However, the necessity to meet the needs of tourists can result in simplifications for mass consumption and, thus, a lack of authenticity (Whitney-Gould et al., Citation2018).

This paper provides an overview of why and how minority languages are used in tourism-related contexts and the consequences, both positive and negative, that this inclusion can have on the communities. This paper seeks to review a selected sample of previous contributions and provide an in-depth analysis of key themes. Consequently, it will identify gaps in the literature and give suggestions for further research.

Methodology

Fink (Citation2005) defines a literature review as a ‘systematic, explicit and reproducible method for identifying, evaluating and synthesizing the existing body of completed and recorded work produced by researchers, scholars and practitioners’ (p. 6). This study will follow the systematic literature analysis approach suggested by David and Han (Citation2004) and Newbert (Citation2007), which provides a transparent, generalizable, and replicable way of summarizing previous knowledge around a certain topic, analyzing and categorizing it. According to David and Han (Citation2004), a systematic synthesis of previous evidence is a fundamental tool of knowledge that can be compared to conducting new research. A good synthesis of previous knowledge can provide complete and in-depth answers to a research question, identify gaps in the literature that needs to be addressed in future research and highlight the strength of available knowledge (Booth et al., Citation2016). This paper will provide in-depth and up-to-date insights into the field of tourism and minority languages. The process of data acquisition followed four main steps with strict selection criteria that are explained here and summarized in :

Books, book chapters, and peer-reviewed papers written in English were considered for analysis, which ensured a complete and detailed list of relevant publications that studied the use of minority language in tourism contexts (David & Han, Citation2004; Madden & Shipley, Citation2012). The software Scopus was used for data collection since it is a complete and comprehensive database of scientific contributions (Booth et al., Citation2016). This analysis considered not only peer-review papers but also books and book chapters to ensure the inclusion of all relevant works in all the disciplines regarding minority languages and tourism (Madden & Shipley, Citation2012). Unfortunately, even though the author is aware that this represents an important limitation, only papers written in English could be considered, mostly because of linguistic limitations of the author and, secondly, to keep the task manageable.

The observation period for this study was quite broad: from 1984 (chosen arbitrarily, as no relevant publication was found prior to that period) to September 2020 (research period). A systematic literature review requires the use of search terms (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). The primary keywords for this first step were ‘minority’, ‘language’, and ‘tourism’ (including their word roots).

In order to ensure a substantial relevance and keep the work manageable, papers that did not include any of the secondary keywords in the abstract or in the title were excluded from further consideration (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). The secondary keywords selected for this step were: ‘promotion’, ‘culture’, ‘indigenous’, ‘experience’, ‘revitalization’, ‘heritage’, ‘preservation’, ‘tradition’, ‘revival’, ‘authentic’ (and word roots), developed in accordance with previous literature (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005; Whitney-Squire, Citation2016). This restriction resulted in 472 contributions.

Thirdly, all remaining contributions were reassessed for fit by checking abstracts and titles. This step assured that contributions with a missing scope would not be considered in further analysis (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). Criteria for exclusions were mainly thematic: as this research aims to analyze the intersection of tourism and minority languages, contributions were excluded if they did not present an interdisciplinary study. Another criterion for exclusion was research that did not consider the language but analyzed other aspects of the living heritage of minority communities. Since this literature review only focuses on minority languages, those papers could not be considered. This step led to the selection of 85 contributions.

Then, the contributions were retrieved and read in their entirety (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). As for the previous step, irrelevant contributions were excluded from further analysis. A total of 49 contributions were selected in this step.

Finally, a parallel check using Google Scholar was conducted (observation period: from 1984 to June 2021). This resulted in an additional 3 contributions.

Table 1. Synthesis of selection criteria.

The final sample totaled 52 publications and consisted almost entirely of peer-reviewed papers, but also included two books. First, the following information was gathered for each contribution: year of publication, journal, location of the study, and methodology used (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). Then, the thematic analysis was drawn from an inductive scheme identified by Mayring (Citation2014). After common patterns regarding results and practical contributions were identified, the publications were organized into common categories (Booth et al., Citation2016; Madden & Shipley, Citation2012; Mayring, Citation2014). The categories or key themes were developed after the literature review and emerged from the inductive and iterative analysis: authenticity, promotion, sustainability, and endangerment. Papers were ascribed to one of the four different categories according to the theme they prioritized (Madden & Shipley, Citation2012). To support key statements, some direct quotes from the papers reviewed will be cited in the results section.

Results

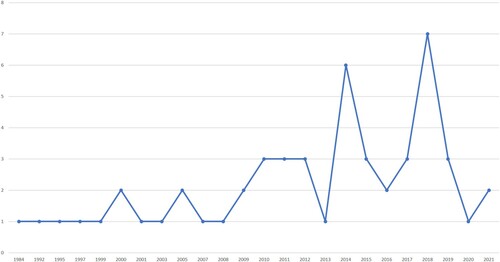

This section will present the key characteristics of the final sample, i.e. their year of publication, methodology, location of the study, and scientific field of the journal where they were published (David & Han, Citation2004; Newbert, Citation2007). The first contribution that focused on the relationship between minority languages and tourism was published in 1984 (Graburn, Citation1984). Not surprisingly, the 80s are characterized by growing awareness about Indigenous peoples, endangered languages and the need to ‘reverse the language shift’ (see Fishman, Citation1991): the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Population was established in 1982. As shows, in the following years, the trend fluctuates, showing changeable attention for this topic. Nonetheless, it might be said that there has been a growing interest in the last years, showing greater attention to minorities. Moreover, this is probably related to two important years: 2003, when the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage was held by UNESCO, and 2010 when the UNESCO’s Atlas of the World Languages in Danger was published. Publications related to minority languages and tourism experiences reached a maximum of 7 in 2018.

shows that the majority of the 52 papers within this review used a qualitative approach (n=34), whereas 10 papers used a quantitative methodology (n=10). It should be noted here that most of the contributions that conducted a qualitative approach used ethnographic research (n=21), whereas the quantitative approach was mainly conducted with the help of the Linguistic Landscape methodology (n=8), a methodology that aims at analyzing ‘visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs’ (Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997, p. 23). A closer examination of data (see ) showed that most studies have an empirical focus on minority communities in Europe (n=22), followed by nine contributions that considered minority communities in Asia (n=10). Africa is the continent that received less attention from the papers considered in this literature review (n=3). Finally, results were analyzed in light of the scientific field where the journal was published. Since the spectrum of journals included in this review was very broad, the author decided to highlight only the scientific field. As shown in , the majority of publications were published in a linguistic journal (n=22), followed by tourism research (n=12) and cultural/anthropological journals (n=10).

Table 2. Papers per location, methods, and scientific field of the journal.

Thematic analysis

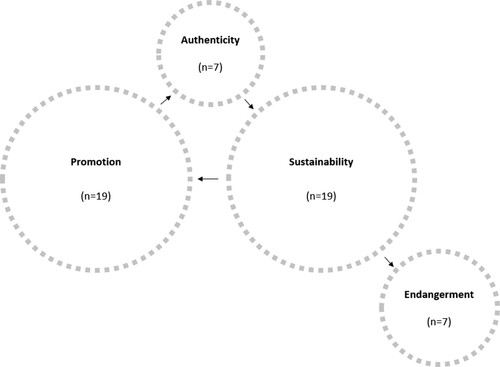

The thematic coding of the 52 contributions allowed for the development of key themes, derived after an in-depth analysis and coding of the content (Madden & Shipley, Citation2012; Mayring, Citation2014). The iterative analysis led to the identification of four key themes:

authenticity (n=7): minority language can be seen as a source of authenticity and localness by tourists. Moreover, many linguists agree that language and culture are related.

promotion (n=19): since languages are perceived as authentic, they are used to promote the destination, as they contribute to differentiating the destination, the products, and to delivering unique cultural experiences.

sustainability (n=19): this theme includes papers that highlight the positive consequences of the tourism industry on the maintenance of minority language.

endangerment (n=7): this theme includes those publications that focus on the negative impact of tourism on the vitality of the minority language.

These four key themes were identified because of common patterns they share. Each contribution was ascribed to one of the four key-themes according to which one they prioritized (Madden & Shipley, Citation2012). The following sections will provide an in-depth explanation of the four key themes.

Authenticity

Results show that minority languages are perceived as authentic by visitors (Bruner, Citation2001; Dlaske, Citation2014; Heller et al., Citation2014a; Moriarty, Citation2015; Pietikäinen, Citation2010; Pietikäinen, Citation2015) since language is seen as a fundamental part of the natural and historical environment (Moriarty, Citation2015):

[…] in their signs the choice of language used in the signs often adds to the authenticity of their product by using words such as handmade (lámhdhéanta), local artists (ealaíontóirí áitiúla) etc. (Moriarty, Citation2015, p. 206)

Nonetheless, authenticity is notoriously a controversial topic in tourism research (Cohen, Citation1988; Cohen, Citation2002; De Bernardi, Citation2019; MacCannell, Citation1976). This controversy is reflected in this literature review. Results confirm that minority languages often undergo the traditional tension between ‘pride and profit’ (Duchêne & Heller, Citation2012) also in tourism-related contexts (Duchêne & Heller, Citation2012; Heller et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b):

Language is involved in two major ways in the globalized new economy: as a source of symbolic added value, and as a mode of management of global networks. As the first, it is tied to the commodification of national identities, in the form of marketing of authenticity; on this terrain, the trope of ‘profit’ appropriates the trope of ‘pride’ in ways that are often rife with tension. (Duchêne & Heller, Citation2012, p. 10)

Promotion

In a globalized and connected world, ethnic attributes are an asset and value-added resource for tourists (Yang, Citation2011). Previous research, for instance, has shown that a significant proportion of tourists are drawn to peripheral areas by their minority cultures and languages (Pechlaner et al., Citation2011; Pitchford, Citation1995), which has been identified as one of the main motivations to visit minority and remote regions (Barakos, Citation2016; Medina, Citation2003). In this context, languages become an essential element to brand a peripheral destination as traditional, ‘other’, or exotic (Bacsi, Citation2017; Barakos, Citation2016; Brennan, Citation2018; Johnson, Citation2010; King & Wicks, Citation2009; Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011; Rapošová, Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2013). According to Barakos (Citation2016), the Welsh language is essential to build a distinctive and authentic ‘brand Wales’ (p. 378). Part of the attractiveness of minority languages is due to their perceived authenticity, as explained in the previous paragraph (Medina, Citation2003). Heller et al. (Citation2014b) argue that cultural or heritage tourism products, including language, derive their value from their ‘ability to index national authenticities’ (p. 553):

Ethnic minorities, with their customs and traditions, languages and architectural styles, can definitely offer added value for holidaymakers. Guests are interested in the cultural variety produced by the existence of minority populations. (Pechlaner et al., Citation2011, p. 60)

[…] positioning Irish as an attractive, differentiating unique selling point (USP) that would augment the appeal of each town as a distinctive and authentic destination for shoppers, local visitors, and international tourists. (Brennan, Citation2018, p. 162)

Some studies have shown that the use of local languages is appealing, not only to external visitors but also to the local population, as it creates a sincere and strong relationship with the local community (Barakos, Citation2016). Other research emphasizes how sometimes marketing campaigns that use elements of the Intangible Cultural Heritage are not appreciated in the homeland because of the stereotypes they strengthen (Pitchford, Citation1995). This aspect will be better discussed in the last key theme, ‘endangerment’.

Sustainability

Numerous prior studies noted that the tourism industry has a positive impact on the preservation of minority languages. As stated, Intangible Cultural Heritage, contrary to Tangible Cultural Heritage, requires constant practice to survive and be available for future generations (Kim et al., Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2003). The findings confirmed that tourism can be seen as a sustainable economic activity, as it plays an important role in giving minority people opportunities to continue speaking the language on a daily basis, maintain it and pass it on to future generations.

The emergence of a globalized economy led, in some cases, to the decline of traditional economic activities. This was the case, for instance, for reindeer herding for Sámi people in Northern Scandinavia and Russia (Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011). The tourism industry partially contributed to the maintenance of those traditional activities and the strengthening of the survival as a distinct cultural group, since it can give a renewed (economic) value to the historic traditions and practices (Carden, Citation2012; Carrier, Citation2011; Hiwasaki, Citation2000; Li et al., Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2018).

For instance, in research conducted by Beard-Moose (Citation2009), interviewees suggested that ‘tourism and tourists is what kept the Cherokees being Cherokees. Because [the tourists] were willing to pay and look for “authentic Indian stuff”’ (p. 4). Consequently, Cherokee people took the (economic) opportunity to preserve and revive many traditional aspects of their heritage, like arts, crafts, living traditions, and performances, as well as languages.

The fact that the language is part of this distinct cultural heritage that interests and attracts tourists (Brennan, Citation2018; Heller et al., Citation2014b; Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011; Pitchford, Citation1995), has been used as an excuse to continue using the language and preserve it (Jaffe, Citation2019; Medina, Citation2003). Some studies have already shown how, in some tourism destinations with minority communities, like Wales (Coupland, Citation2012), Ireland (Moriarty, Citation2015), and Sámiland (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2014), the status of minority languages has been enhanced by their inclusion in public spaces and tourism experiences. Castillo-Villar and Merlo-Simoni (Citation2021) argue that, even though the community does not think that tourism is a tool for language preservation, ‘it views it more as an additional tool for promoting Chipilo’s identity through its language and other intangible cultural elements (e.g. gastronomy).’ (p.11)

Tourism has helped to move beyond the commodified use of the language and create new innovative spaces for the language to emerge and extend the use of the language at home, in the schools, at work, in public spaces, as well as increase the prestige and status of the language (Brennan, Citation2018). In some destinations, or cultural institutions in those destinations, the mission statement also includes the objective of sustaining and promoting the culture and language (Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011). Museums have also been described as spaces where the same minority people can educate themselves about their heritage, their traditions, and their language (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2016; Whitney-Squire et al., Citation2018). Finally, the use of the minority language in contexts such as tourism spaces or tourism experiences can also be attractive and helpful for people who understand how important, fruitful and even profitable language preservation is and will try to repeat the same process in their own communities (Suleymanova, Citation2018).

Many of the studies, however, highlighted a still more important reason why the tourism field positively affected the lives of minority communities. Tourism in many of those areas has, either directly or indirectly, revitalized and strengthened the social and cultural structures of minority communities (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005), which resulted in a (re)newed pride in their traditional cultures and a sense of identity and belonging among minority people (Coupland, Citation2012; Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2014; Makihara, Citation2005; Pitchford, Citation1995; Serreli, Citation2019; Stronza, Citation2008; Whitney-Gould et al., Citation2018). This pride and sense of identity eventually also resulted in an increased motivation among community members to learn and improve their traditional languages or to reveal their linguistic competence (Stronza, Citation2008), as well as an actual effort in preserving those languages and transmitting them to future generations (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005):

The four indicators of renewed (or new) pride in Ese eja culture […] are: (1) heightened concern for cultural rescue and learning language, stories, and songs from elders; (2) interest in presenting various aspects of Ese eja culture to tourists, coupled with debates over intellectual property rights; (3) adoption of Ese eja identity by non-Ese eja members of the community; (4) discussions of dividing the community. (Stronza, Citation2008, p. 253)

Another guide recalled having little interest in Maya culture when he began a job as a guide […]. When tourists […] wanted to visit Xunantunich, he had hired someone else to guide them through the ruins. However, little by little he began to appreciate how tourists valued Mayan culture, and thus he also became interested. […], he enrolled in a three-day class taught by an archaeologist who was excavating at Xunantunich. He also began reading books on ancient Maya culture and cosmology […]. (Medina, Citation2003, p. 362)

This process of language preservation works better than an official language revitalization program because it is conceptualized in a framework of pride, which authenticates the process since it gives more power to the people (Beard-Moose, Citation2009; Jaffe, Citation2019). Tourism, in fact, can also contribute to the empowerment of minority people, as they become the owner of their cultural heritage (Stronza, Citation2008; Văduva et al., Citation2021). Local communities have, then, the opportunity to decide what to showcase to tourists and what to keep ‘private’ and to define their own identity, history and heritage, and present these to outsiders.

Endangerment

Nonetheless, it is important to note that few studies identified a negative relationship between tourism and minority languages and this is the reason why this last key theme was called endangerment. As a matter of fact, most of the languages that can be identified as minority languages are also categorized by the UNESCO’s Atlas of World’s Languages in Danger (Moseley, Citation2010) as being threatened to different degrees.

According to previous studies, through language commodification language becomes standardized, over-simplified, and souvenirized in order for tourists to experience and enjoy it (Kaomea, Citation2000; Wang, Citation2012). Moreover, in some contexts, the commodification of minority cultures, including their language, can lead to the strengthening of stereotypes with regards to a minority community, its heritage, its tradition, including also the language (Kaomea, Citation2000). Through commodification, the language can be assigned a different role and be fetishized to be used as a marketing gimmick (Wang, Citation2012). Some previous studies also argued that emphasizing the distinctive value of minority language as a commercial and promotional asset shifts the focus away from issues of cultural preservation or linguistic rights (Graburn, Citation1984). Moreover, in the context of linguistic endangerment and multilingualism, as these minority areas are, telling the story of the link between language and culture can only provide one part of the reality of everyday life (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2016).

Kelly-Holmes and Pietikäinen (Citation2016) argue, for instance, that it is not easy to represent the Intangible Cultural Heritage in tourism experiences, especially in museums, and it can therefore easily undergo a process of objectification. Therefore, museums can also lead to the reinforcement of both the global and the national language, because these are presented in primary positions and are necessary in order for the museum to be intelligible by visitors from outside the minority community as well. This can contribute to underlining the tension between two main and conflicting forces: internationalization and localization, which is frequent in tourism but through the tourism industry are sometimes conveyed to the relationship between minor and major languages as well (Amara, Citation2019; Bruyèl-Olmedo & Juan-Garau, Citation2015; Eagle, Citation1999). Similarly, employees in many service industries in tourism destinations need to be able to welcome guests in their own language, instead of one’s minority language (Heller et al., Citation2014b):

The primary language of tourism, at all levels, is English […]. English is used even with tourists who come from non-English speaking countries. […] Competence in English is a requirement for all jobs available in the tourist industry. (Eagle, Citation1999, p. 310)

A second reason […]: the lack of symbolic value of Catalan for mass tourists. […] Not being aware of the existence of a local language, tourists are unlikely to demand or accept its presence in the public space as part of their holiday experience. (Bruyèl-Olmedo & Juan-Garau, Citation2015, p. 16)

Conclusions, limitations, and further research

Findings of this study enable a better understanding of the main themes that were developed around research on minority languages and tourism. This review highlighted four themes: authenticity, promotion, sustainability, and endangerment.

This literature review is particularly important and timely not only for linguists but also for heritage tourism studies: it addresses two growing segments in tourism, i.e. increasing interest in intangible cultural heritage and in peripheral areas (Richards, Citation2018). The contributions particularly address tourism destinations where minority communities reside, through the consolidation of prior knowledge about the mutual relationship between a particular aspect of intangible cultural heritage, i.e. minority languages (UNESCO, Citation2003), and the tourism field. The literature review provides evidence that intangible cultural heritage, and specifically minority languages, are a distinctive, unique asset for heritage tourism, as they contribute to differentiate (Pechlaner et al., Citation2011) and authenticate some destinations (Moriarty, Citation2015; Pietikäinen, Citation2010), souvenirs (Pietikainen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2011), and commercial goods (Ferguson & Sidorova, Citation2018), as well as increase the quality of customer service, leading to customer loyalty, and creation of a competitive edge (Barakos, Citation2016). Members of minority language communities should also be aware that language commodification in many cases has enabled a change of perspective from the idea that minority languages are associated with backwardness and poverty towards a more positive value: a (re)newed sense of pride and identity (Carrier, Citation2011; Coupland, Citation2012; Stronza, Citation2008). In many destinations, this was related to willingness to learn more about their heritage, including their language (Medina, Citation2003) and desire to preserve the language (Greathouse-Amador, Citation2005). In this way, the authenticity of the language is preserved (Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2014), which enhances the virtuous circle of language preservation through the use of minority languages in the tourism field (Lonardi et al., Citation2020), thus contributing to maintaining the differentiating and unique value of the destination (see ).

This literature review emphasized some problematic issues related to the use of minority languages as a branding element in the service industry and marketing. Tourism can promote the necessity for tourism practitioners and employees to master the English or official language (Amara, Citation2019; Bruyèl-Olmedo & Juan-Garau, Citation2015), as well as an objectified, superficial use of the minority language (Kaomea, Citation2000; Kelly-Holmes & Pietikäinen, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2012). This has significant negative impacts on the vitality of the minority languages (see ), as they, like other elements of the intangible cultural heritage, are particularly precarious, because they need constant practice from the population (Kim et al., Citation2019).

This emphasizes the necessity for members of the minority communities to be actively involved in every step of tourism planning, management, and promoting (Brundtland, Citation1987) so that they can decide what and how to show minority languages to tourists and how to use the language. Otherwise, the virtuous circle of language preservation through language commodification will be broken, laying the foundations for linguistic standardization and language endangerment.

This literature review is not without limitations. Firstly, because of linguistic limitations of the author, all papers selected were written in English, which represents a significant problem when focusing on minority languages. Secondly, the thematic analysis is to a certain degree subjective to the researcher (Mayring, Citation2014). However, despite the above-mentioned limitations, this literature review represents a stepping stone and provides some significant suggestions for further research in the area.

A future research agenda in heritage tourism studies should carefully consider the four key themes found during this literature review, as well as its limitations.

Specifically, since languages are a fundamental aspect of the living heritage of a population and are, thus, perceived as authentic by tourists, researchers should conduct an in-depth study on how minority communities negotiate the authenticity of the language and its promotion to persons from outside the community.

Secondly, this study confirmed that minority languages are part of the tourism promotion. Therefore, future researchers in this field should analyze new ways to promote the language with tourists – e.g. through various digital tourism experiences or through virtual reality.

Although there is a growing understanding of the sustainable use of cultural resources in tourism and their consequences for society, the next studies should contribute to this understanding and provide a more in-depth understanding of the impacts of sustainable tourism in the maintenance of a minority language through a longitudinal study.

Moreover, future studies should remedy the main limitation of this study and include research published in other languages than English, as well as consider important works that cannot be found in the major search engines, like unpublished dissertations. This will be an opportunity to highlight studies written in minority languages.

Finally, available literature describes tourism situations and contexts from very diverse groups and areas that are not easily comparable, i.e. a statement about a group may not be the case for another. Moreover, some minority language communities have been neglected (see ): the majority of contributions analyzed a European context, leaving room for further research regarding other minorities in the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Serena Lonardi

Serena Lonardi is a Pre-Doc University Assistant at the Department of Strategic Management, Marketing and Tourism at the University of Innsbruck (Austria). Her main research interests are cultural tourism, sustainable tourism, and intangible heritage, especially minority languages, including language endangerment and language preservation.

References

- Amara, M. (2019). Arabisation, globalisation, and Hebraisation reflexes in shop names in the Palestinian Arab linguistic landscape in Israel. Language and Intercultural Communication, 19(3), 272–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2018.1556676

- Bacsi, Z. (2017). Tourism and diversity. Deturope (Online), 9(2), 25–57.

- Barakos, E. (2016). Language policy and governmentality in businesses in Wales: A continuum of empowerment and regulation. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 35(4), 361–391. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2015-0007

- Beard-Moose, C. T. (2009). Public Indians, private Cherokees. Tourism and tradition on tribal ground. University of Alabama Press (Contemporary American Indian studies).

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Bradley, M., & Bradley, D. (2019). Language endangerment. Cambridge University Press.

- Brennan, S. C. (2018). Advocating commodification: An ethnographic look at the policing of Irish as a commercial asset. Language Policy, 17(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-017-9438-2

- Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. United Nations Commission.

- Bruner, E. M. (2001). The Maasai and the Lion King: Authenticity, nationalism, and globalization in African tourism. American Ethnologist, 28(4), 881–908. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2001.28.4.881

- Bruyèl-Olmedo, A., & Juan-Garau, M. (2015). Minority languages in the linguistic landscape of tourism: The case of Catalan in Mallorca. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 36(6), 598–619. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.979832

- Bryce, D., Curran, R., O’Gorman, K., & Taheri, B. (2015). Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tourism Management (1982), 46, 571–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.012

- Butler, R., & Hinch, T. (Eds.). (2007). Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications. Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Butler, R. W. (1978). The impact of recreation on life styles of rural communities. A case study of Sleat, Isle of Skye. In: Studies in the geography of tourism and recreation. Wiener Geographische Schriften, Geographisches Institut der Wirtschaftsuniversitat, 51/52, 187–201.

- Carden, S. (2012). Making space for tourists with minority languages: The case of Belfast's Gaeltacht Quarter. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 10(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2011.653360

- Carrier, N. (2011). Reviving Yaaku: Identity and indigeneity in Northern Kenya. African Studies: Heritage, History and Memory: New Research from East and Southern Africa, 70(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2011.594632

- Castillo-Villar, F. R., & Merlo-Simoni, G. (2021). Locals’ perspectives on the role of tourism in the preservation of a diaspora language: The case of Veneto in Mexico. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2021.1937192

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

- Cohen, E. (2002). Authenticity, equity and sustainability in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(4), 267–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667167

- Council of Europe. (1992). Explanatory report to the European charter for regional or minority languages.

- Coupland, N. (2012). Bilingualism on display: The framing of Welsh and English in Welsh public spaces. Language in Society, 41(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404511000893

- David, R. J., & Han, S.-H. (2004). A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strategic Management Journal, 25(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.359

- De Bernardi, C. (2019). Authenticity as a compromise: A critical discourse analysis of Sámi tourism websites. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527844

- Dlaske, K. (2014). Semiotics of pride and profit: Interrogating commodification in indigenous handicraft production. Social Semiotics, 24(5), 582–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.943459

- Duchêne, A., & Heller, M. (2012). Language in late capitalism. Pride and profit. Routledge.

- Eagle, S. (1999). The language situation in Nepal. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 20(4-5), 272–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434639908666382

- Erőss, Á. (2017). Politics of street names and the reinvention of local heritage in the contested urban space of Oradea. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 66(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.66.4.6

- Ferguson, J., & Sidorova, L. (2018). What language advertises: Ethnographic branding in the linguistic landscape of Yakutsk. Language Policy, 17(1), 23–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-016-9420-4

- Fink, A. (2005). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper (2nd ed.). SAGE Publ.

- Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing language shift: Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages. Multilingual Matters (76).

- Graburn, N. H. (1984). The evolution of tourist arts. Annals of Tourism Research, 11(3), 393–419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(84)90029-X

- Greathouse-Amador, L. M. (2005). Tourism and policy in preserving minority languages and culture: The Cuetzalan experience. IReview of Policy Research, 22(1), 27–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2005.00117.x

- Heinrich, P. (2010). Language choices at Naha Airport. Japanese Studies, 30(3), 343–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2010.518599

- Heller, M. (2003). Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 473–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00238.x

- Heller, M., Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2014a). Introduction: Sociolinguistics and tourism - Mobilities, markets, multilingualism. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(4), 425–458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12091

- Heller, M., Pujolar, J., & Duchêne, A. (2014b). Linguistic commodification in tourism. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(4), 539–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12082

- Hiwasaki, L. (2000). Ethnic tourism in Hokkaido and the shaping of Ainu Identity. Pacific Affairs, 50(3), 393–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2672026

- Jaffe, A. (2019). Poeticizing the economy: The Corsican language in a nexus of pride and profit. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 38(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2018-0005

- Johnson, I. (2010). Tourism, transnationality and ethnolinguistic vitality: The Welsh in the Chubut Province. Argentina. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(6), 553–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2010.511228

- Kaomea, J. (2000). A curriculum of Aloha? Colonialism and tourism in Hawai‘i’s elementary textbooks. Curriculum Inquiry, 30(3), 319–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00168

- Kauppinen, K. (2014). Welcome to the end of the world! Resignifying periphery under the new economy: A nexus analytical view of a tourist website. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2013.831422

- Kelly-Holmes, H., & Pietikäinen, S. (2016). Language: A challenging resource in a museum of Sámi culture. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1058186

- Kelly-Holmes, H., & Pietikäinen, S. (2014). Commodifying Sámi culture in an indigenous tourism site. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(4), 518–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12092

- Kim, S., Whitford, M., & Arcodia, C. (2019). Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(5-6), 422–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1561703

- King, R., & Wicks, J. (2009). Aren’t we proud of our language? Journal of English Linguistics, 37(3), 262–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424209339924

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002

- Li, J., Xu, M., & Chen, J. (2020). A Bourdieusian analysis of the multilingualism in a poverty-stricken ethnic minority area: Can linguistic capital be transferred to economic capital? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1733585

- Lonardi, S., Martini, U., & Hull, J. S. (2020). Minority languages as sustainable tourism resources: From Indigenous groups in British Columbia (Canada) to Cimbrian people in Giazza (Italy). Annals of Tourism Research, 83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102859

- MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist. A new theory of the leisure class. Schocken.

- Madden, M., & Shipley, R. (2012). An analysis of the literature at the nexus of heritage, tourism, and local economic development. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 7(2), 103–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2011.632483

- Makihara, M. (2005). Being Rapa Nui, speaking Spanish. Anthropological Theory, 5(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499605053995

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt.

- Medda-Windischer, R. (2017). Old and new minorities: Diversity governance and social cohesion from the perspective of minority rights. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, European and Regional Studies, 11(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/auseur-2017-0002

- Medina, L. K. (2003). Commoditizing culture. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 353–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00099-3

- Moriarty, M. (2014). Contesting language ideologies in the linguistic landscape of an Irish tourist town. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(5), 464–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913484209

- Moriarty, M. (2015). Indexing authenticity: The linguistic landscape of an Irish tourist town. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2015(232), 195–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2014-0049

- Moseley, C. (Ed.). (2010). Atlas of the world's languages in danger (3rd ed.). UNESCO Publishing. Retrieved June 30, 2021 from http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/en/atlasmap.html

- Newbert, S. L. (2007). Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.573

- O'Rourke, B., & DePalma, R. (2017). Language-learning holidays: What motivates people to learn a minority language? International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(4), 332–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2016.1184667

- Pechlaner, H., Lange, S., & Raich, F. (2011). Enhancing tourism destinations through promoting the variety and uniqueness of attractions offered by minority populations: An exploratory study towards a new research field. Tourism Review, 66(4), 54–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/16605371111188740

- Pietikainen, S., & Kelly-Holmes, H. (2011). The local political economy of languages in a Sami tourism destination: Authenticity and mobility in the labelling of souvenirs. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15(3), 323–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2011.00489.x

- Pietikäinen, S. (2010). Sámi language mobility: Scales and discourses of multilingualism in a polycentric environment. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 202, 79–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/IJSL.2010.015

- Pietikäinen, S. (2015). Multilingual dynamics in Sámiland: Rhizomatic discourses on changing language. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913489199

- Pitchford, S. R. (1995). Ethnic tourism and nationalism in Wales. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00068-4

- Rapošová, I. (2019). ‘We can't just put any belly-dancer into the program': Cultural activism as boundary work in the city of Bratislava. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(11), 2100–2117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440543

- Rees, H. (1998). “Authenticity” and the foreign audience for traditional music in Southwest China. Journal of Musicological Research, 17(2), 135–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01411899808574744

- Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005

- Schedel, L. S., Muth, S., & Del Percio, A. (2018). Turning local bilingualism into a touristic experience. Language Policy, 17(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-017-9437-3

- Serreli, V. (2019). Globalization in the periphery: Arabization and the changing status of Siwi Berber in the oasis of Siwa. Sociolinguistic Studies, 12(2), 231–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.35565

- Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2020). Exploring memorable cultural tourism experiences. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1639717

- Stronza, A. (2008). Through a new mirror: Reflections on tourism and identity in the Amazon. In: Human Organization, 67(3), 244–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.67.3.a556044720353823

- Suleymanova, D. (2018). Creative cultural production and ethnocultural revitalization among minority groups in Russia. Cultural Studies, 32(5), 825–851. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2018.1429004

- Sun, J., Wang, X., & Ma, T. (2018). De-localization and re-localization of ethnic cultures: What is the role of tourism? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(11), 1034–1046. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1513947

- Toso, F. (2008). Le minoranze linguistiche in Italia. Il mulino.

- UNESCO. (2003). Basic texts of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage.

- UNWTO. (2018). Tourism and culture synergies. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. SAGE.

- Văduva, L., Petroman, C., Marin, D., & Petroman, I. (2021). Ethnic tourism: A niche form of sustainable tourism. Quaestus, 18, 258–270.

- Wang, M. (2012). The social life of scripts: Staging authenticity in China's ethno-tourism industry. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development, 41(2/3/4), 419–455.

- White, P. E. (1974). The social impact of tourism on host communities: A study of language change in Switzerland. University of Oxford School of Geography, 9.

- Whitney-Gould, K., Wright, P., Alsop, J., & Carr, A. (2018). Community assessment of Indigenous language-based tourism projects in Haida Gwaii (British Columbia, Canada). Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(11), 1909–1927. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1526292

- Whitney-Squire, K. (2016). Sustaining local language relationships through indigenous community-based tourism initiatives. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1156–1176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1091466

- Whitney-Squire, K., Wright, P., & Alsop, J. (2018). Improving Indigenous local language opportunities in community-based tourism initiatives in Haida Gwaii (British Columbia, Canada). Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1327535

- Yang, J., Ryan, C., & Zhang, L. (2013). Ethnic minority tourism in China – Han perspectives of Tuva figures in a landscape. Tourism Management, 36, 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.11.001

- Yang, L. (2011). Ethnic tourism and cultural representation. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 561–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.10.009