ABSTRACT

It is important to understand consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic because it may support organizations to recover. Risk perceptions are likely to play a role in influencing intentions to visit a cultural heritage destination. The goal of this study is to describe risk perceptions and to examine the influence of these perceptions on the revisit intentions to a cultural heritage location during the COVID-19 era in the Netherlands. In this quantitative study, a sample of 470 respondents is used. Our model was tested using structural equation modeling. The results show that the respondents take COVID-19 seriously and that part of the respondents do not feel comfortable taking domestic trips. Nevertheless, the respondents have faith in the hygiene measures taken by the location they have visited earlier, and they believe a revisit would still be satisfactory. Whilst the model shows a good fit with the data, contrary to expectations, there is no relationship between six risk perceptions and the revisit intention. The study stresses the importance of establishing relationships with existing visitors and building upon their trust.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has a had devastating impact on society in terms of physical health, psychological well-being, and economic prosperity. Worldwide, national authorities impose heavy restrictions, such as lockdowns and restricted mobility, which strongly affect leisure and tourism systems (Gössling et al., Citation2021). Heritage organizations had to close their doors, reopen, and close again. In certain periods, almost all museums worldwide had to close (ICOM, Citation2020a). Visitor numbers have decreased considerably, whereby the decrease in global tourism was a major factor (NEMO, Citation2021). UNESCO (Citation2021) states that on average museums worldwide had to close for more than 150 days in 2020. UNESCO (Citation2021) further reports that the majority of the museums faced a decrease in attendance of more than 60%, and a decline between 40% and 60% of museum revenues. The loss of income of cultural organizations resulted in downsizing temporary and permanent staff (ICOM, Citation2020b).

Besides the regulations mentioned above, it seems opportune and logical to consider risk perception as the main culprit for this change in behavior. However, risk perception has always played a role in the consumer decision making process. Services are heterogeneous and intangible, which implies that sometimes it is difficult for consumers to create a proper imagination of expected services (Zeithaml et al., Citation2009). Moreover, service delivery may not always be consistent. This means that consumers always take a certain level of risk. Studies into risk perceptions show that they have a significant effect on behavioral intentions, especially when a situation is perceived as dangerous (Chew & Jahari, Citation2014; Hasan et al., Citation2017). Risk perceptions have a different nature, varying from physical or health, satisfaction, equipment, terrorism, psychological, social, to time risks (Adam, Citation2015; Cheron & Ritchie, Citation1982; Floyd et al., Citation2004).

Although many studies have investigated the impact of risk perceptions on tourist decision-making processes, there seems to be little attention in examining the role of risk perceptions towards attending heritage sites or tourist attractions. In most studies into risk perceptions, the focus is on an international travel context. Studies are examining the role of risk perceptions of international travelers in the context of terrorism, health issues or specific market segments (Adam, Citation2015; Cossens & Gin, Citation1995; Floyd et al., Citation2004). Overall, studies investigating perceived health risks show that health issues are regarded as a serious concern by international travelers (Kozak et al., Citation2007; Moreira, Citation2008). However, the relationship between health risk perceptions and travel intentions is unclear. Some studies show that these risk perceptions influence travel intentions (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016; Ruan et al., Citation2020), while other studies show a marginal impact on destination choice or do not find a positive relationship between these variables (Cossens & Gin, Citation1995; Lee et al., Citation2012).

Understanding consumer tourism behavior in the COVID-19 era is crucial for tourism’s continued existence. Already, several studies have examined the impact of health risk perceptions on tourism and leisure behavior during the COVID-19 era (Neuburger & Egger, Citation2020; Parady et al., Citation2020; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2020). However, it seems there are not many studies into understanding consumer behavior of visitors of heritage sites in the COVID-19 era. The goal of this study is to describe risk perceptions in the COVID-19 era and to examine the influence of risk perceptions on revisit intentions in a cultural heritage context. The study contributes to the literature threefold: (1) it investigates the role of risk perceptions in visitors’ decision-making behavior attending cultural heritage, (2) it deepens the knowledge of the relationship between health-risk perceptions and visit intentions, and (3) it explores the role of six risk perceptions during a pandemic. This study includes perceptions related to three types of health risks, social risk, satisfaction risk and psychological risk on revisiting a cultural heritage site in the COVID-19 era shortly after a lockdown.

Literature review

Risk perceptions

Perceived risk is related to a potential loss and is an interplay of probability and consequences (Boksberger et al., Citation2007; Chew & Jahari, Citation2014; Jonas et al., Citation2011). Dowling and Staelin (Citation1994, p. 119) define risk perceptions as ‘the consumer's perceptions of the uncertainty and adverse consequences of buying a product (or service)’. Risk perceptions are beliefs based upon an evaluation of outcomes and the chance that these outcomes will happen (Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011). This means that risk perceptions contain two main uncertain components: the probability that adverse consequences occur and the magnitude of these consequences (Boksberger et al., Citation2007; Hasan et al., Citation2017). Floyd et al. (Citation2000) argue that the perception of severity and vulnerability influences the appraisal of the risk. Severity is the extent to which the consequences of the threat are taken seriously (e.g. perceptions of seriousness of an illness), and vulnerability (in some studies referred to as susceptibility) relates to a chance that a threat will occur (e.g. the perception of the probability of contracting a disease) (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016; Ruan et al., Citation2020). The assessment of risk perceptions is subjective and intuitive (Hasan et al., Citation2017; Moreira, Citation2008; Ruan et al., Citation2020). Dowling and Staelin (Citation1994) argue that risk perceptions may be related to a specific product category or to a specific brand or organization. Risk perceptions are influenced by knowledge about the risks, risk characteristics (such as immediate or delayed, controllable or not), trust, personal experience and personality traits (Godovykh et al., Citation2021; Moreira, Citation2008; Zielinski & Botero, Citation2020).

Perceived risk in leisure and tourism

Many studies focus on international travel and tourism and less on local domestic recreational or cultural activities. Several studies investigate risk perceptions related to international travel intentions in general (Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998; Wong & Yeh, Citation2009). Other studies focus on international travel risk perceptions related to terrorism, such as intentions to take a pleasure trip shortly after a terrorist attack (Floyd et al., Citation2004), travel intentions related to terrorism and attending Olympic games (Choi et al., Citation2019), or terrorism and disease (Rittichainuwat & Chakraborty, Citation2009), or related to crime-safety (George, Citation2010). Many studies investigate health risks in international travel (Cossens & Gin, Citation1995; Jonas et al., Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2012; Neuburger & Egger, Citation2020; Ruan et al., Citation2020). Other studies focus on international travel and certain market segments such as backpackers (Adam, Citation2015), or airline travelers (Boksberger et al., Citation2007; Ringle et al., Citation2011), create tourist profiles based on risk perceptions (Floyd & Pennington-Gray, Citation2004), or compare first-time and repeat visitors (Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011). Only a few studies relate risk perceptions to leisure patterns and study either a range of different leisure activities (Cheron & Ritchie, Citation1982), or focus on shopping risk perceptions (Yüksel & Yüksel, Citation2007).

Risk perception is a multi-dimensional concept (Hasan et al., Citation2017; Roehl & Fesenmaier, Citation1992). Seven risk factors or dimensions can be identified: (1) physical or health risks, (2) financial or satisfaction risks, (3) equipment or functional risks, (4) risks related to political instability or terrorism, (5) psychological risks, (6) social risks, and (7) time loss (Adam, Citation2015; Choi et al., Citation2019; Floyd et al., Citation2004; Roehl & Fesenmaier, Citation1992; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998). Firstly, physical risks refer to the possibility of or injuries or physical dangers because of a service failure (Adam, Citation2015; Boksberger et al., Citation2007). In a tourism context it is often related to accidents, natural disasters, injuries due to participation in specific activities (Adam, Citation2015; Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011). However, physical risks can also be associated with health risks. Health risks deal with the possibility of becoming ill or getting certain diseases (Adam, Citation2015). Some studies examined the role of health risk perception in tourist decision making processes, without taking into account other perceived risks (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016; Cossens & Gin, Citation1995; Jonas et al., Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2012), while some studies incorporate other risk perceptions (Kozak et al., Citation2007; Moreira, Citation2008; Rittichainuwat & Chakraborty, Citation2009; Ruan et al., Citation2020). Secondly, some studies refer to financial risks or satisfaction risks as one type of risk. These risks are related to the perceived likelihood of having a dissatisfying experience or not receiving value for money (Adam, Citation2015; Boksberger et al., Citation2007; Chew & Jahari, Citation2014). Fuchs and Reichel (Citation2011) distinguish financial risks and service quality risks. Financial risks relate to unexpected expenses and service quality risks measure the dissatisfaction of services (Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011). Thirdly, equipment or functional risk is associated with the likelihood of failure of equipment, mechanical problems, service failure or organizational problems (Adam, Citation2015; Boksberger et al., Citation2007; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998). Fourthly, consumers may perceive terrorism risks because they are afraid of an attack in a country they want to visit (Choi et al., Citation2019). Other prospective tourists might perceive political instability, such as riots or revolutions, as a key factor of not visiting a country (Choi et al., Citation2019). George (Citation2010) investigates perceptions of crime-safety with respect to attending a national park in South-Africa. Fuchs and Reichel (Citation2011) apply the concept of human-induced risks, covering risks such as crime, political instability, and terror. Fifthly, psychological risk is related to various concepts and not clearly defined. Adam (Citation2015) refers to the likelihood that an experience is not congruent with an individual’s self-image. Boksberger et al. (Citation2007) relate psychological risks to the probability of embarrassment, negatively affecting an individual’s peace of mind, or a loss of self-esteem. Wong and Yeh (Citation2009) relate psychological risks to feelings of discomfort, nervousness or unsafety. Floyd et al. (Citation2004) frame these same feelings as travel risk and appear to be one of the three risk dimensions derived from factor analysis. Because psychological risk is not uniformly defined, there is a lack of consistency as to how to measure psychological risk. Sixthly, social risks are related to the possibility that reference groups have different standards or images and will disapprove individuals’ choices (Floyd et al., Citation2004; Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011). Some studies combine psychological risks with social risks into one component (Adam, Citation2015; Chew & Jahari, Citation2014). Seventhly, time loss risk is the chance that the service will be too time consuming or a waste of time (Cheron & Ritchie, Citation1982; Fuchs & Reichel, Citation2011; Roehl & Fesenmaier, Citation1992). Finally, Fuchs and Reichel (Citation2011) also include weather and food safety as a risk factor. However, it could be argued that these factors are part of the satisfaction risks and physical risks respectively.

Conceptual model and hypotheses

In this section, we describe the conceptual model () and build hypotheses. The influence of risk perceptions on intentions is contextual and depends on the type of activity and consumers’ beliefs about the extent of controlling circumstances (Kim & Kang, Citation2021; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2020). Because risk perceptions are situation-specific, risk types need to be selected according to a specific, contextual setting (Chew & Jahari, Citation2014; Dowling & Staelin, Citation1994; Jonas et al., Citation2011; Roehl & Fesenmaier, Citation1992).

This study investigates risk perceptions of visitors of a cultural heritage site in the COVID-19 era. Therefore, health risk perceptions (severity and vulnerability) play a major role in this study. Severity relates to the consequences of the threat (e.g. perceptions of COVID-19 as a serious disease), and vulnerability is the probability that a threat will occur (e.g. is it likely to contract COVID-19) (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016; Ruan et al., Citation2020). The relationship between the perception of health risks and travel intentions is not clear. Some studies show that perceived travel risk and susceptibility are related to travel intentions (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016) or that severity and vulnerability are related to travel intentions (Ruan et al., Citation2020). Also, more recently, studies into risk perceptions related to COVID-19 show that these perceptions influence travel attitudes and intentions to undertake leisure trips (Abraham et al., Citation2020; Parady et al., Citation2020; Sánchez-Cañizares et al., Citation2020). However, other studies show that health risks influence the tourism destination choice of only around 15% of the respondents (Cossens & Gin, Citation1995), perception of the disease is not related to travel intentions (Lee et al., Citation2012), or that perceived severity is not related to travel intentions (Cahyanto et al., Citation2016). In line with the distinction between general and brand-specific risk perceptions made by Dowling and Staelin (Citation1994), in this study, a distinction is made between general vulnerability (risk perception on infection in general) and brand-related vulnerability (the chance of contracting the virus when visiting a specific location).

H1: Severity perception of COVID-19 has a negative influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

H2: General vulnerability perception of COVID-19 has a negative influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

H3: Brand-related vulnerability perception of COVID-19 has a negative influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

Although the literature is not really clear about the influence of satisfaction risk on intentions, we expect that visitors might perceive a satisfaction risk because of the COVID-19 precaution measures and social distancing.

H4: Satisfaction risk perception has a negative influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

The influence of social risk perception on intentions is clearly demonstrated in several studies (Floyd et al., Citation2004; Huy Tuu et al., Citation2011; Zhu et al., Citation2009).

H5: Social risk perception has a negative influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

In line with other studies, psychological risk is included to measure feelings of nervousness and comfort when traveling domestically (Floyd et al., Citation2004; Huy Tuu et al., Citation2011; Zhu et al., Citation2009). The studies of Floyd et al. (Citation2004) and Sönmez and Graefe (Citation1998) show there is no relationship between psychological risk and travel intentions.

H6: Psychological risk perception has no influence on revisit intentions whilst controlling for the effects of other variables.

Methods

Study design

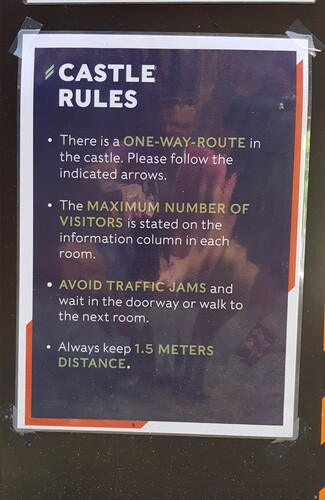

This study aims to test the relationship between risk perceptions and intention to revisit in the context of a cultural heritage site in the Netherlands, Loevestein Castle ( and ). This castle is a well-known medieval castle in one of the wetlands in the Netherlands, built between 1357 and 1397. Loevestein Castle used to be a state prison and was part of the Hollandic Water Line. Nowadays, the castle functions as a museum and attracted 73,054 paying visitors in 2019, 46,819 visitors in 2020, and 49,647 visitors in 2021 (R. de Graaff, personal communication, February 1, 2022).

The data were collected through online questionnaires using Qualtrics, an online tool to design and distribute surveys (Qualtrics, Citation2021). Our research population are former visitors of the cultural heritage site, who have visited the site before in the period from January 2018 to March 15th, 2020. These former visitors had left their contact details when booking tickets and gave consent to be contacted in future communications. Note that on the 15th of March 2020, 168 people were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Netherlands (Rijksoverheid, Citation2020e), and the first lockdown went into effect (Rijksoverheid, Citation2020a, Citation2020c). A convenience sample was taken. On the 17th of July 2020, an email was sent out to the complete database of 2,714 former visitors with an invitation to take part in the research. Of these 2,714 people, 740 opened the link to the online survey. It should be noted that from the 1st of June 2020 many restrictions were lifted, and cultural venues and heritage sites reopened (Langelaan, Citation2020; Rijksoverheid, Citation2020b). Furthermore, the daily infection rates were low in the first week of June 2020, between 0.5 and 1.4 infections per 100,000 inhabitants (Rijksoverheid, Citation2020d).

Initially, 570 respondents were collected aged 18 and older. We removed 25 respondents due to respondents answering all 5-point Likert items with no variation. 53 respondents were removed because they had missing values on relevant variables. A further 22 observations were removed after controlling for multivariate outliers. The total number of respondents left after these procedures is 470 ( and ).

Respondents’ profile

shows the demographic profile of the respondents in this study. The respondents were all Dutch. The socio-demographic profile is slightly different from Dutch demographics because relatively more women participated in the survey and participants’ education level is higher. We think that the over representation of women could have been caused by the voluntary nature of our survey. Nield and Nordstrom (Citation2016) have empirically confirmed that convenience samples suffer from a gender bias because women are more inclined to answer surveys than men. The higher education level found in our sample is less likely a matter of a biased sample. The higher educated do tend to visit cultural heritage more often in the Netherlands than the lower educated (Van den Broek, Citation2021).

Table 1. Demographic profile of the respondents (N = 470).

Operationalization

The online questionnaire was developed in Dutch by adapting, translating and back-translating existing scales. The questionnaire consisted of four sections: risk perceptions, behavioral intentions, visitor motives (not included in this paper) and socio-demographics. The items are described in . Six types of risk perceptions were included in this study: three health risks (severity, general vulnerability and brand-related vulnerability), satisfaction risk, social risk and psychological risk perceptions. Severity and general vulnerability are measured by three items each, respectively based on Ruan et al. (Citation2020) and Gerhold (Citation2020). Brand-related vulnerability is measured by four items based on Ruan et al. (Citation2020) and Siongers et al. (Citation2020). Satisfaction risk is measured by four items based on Zhu and Deng (Citation2020), Huy Tuu et al. (Citation2011) and Roehl and Fesenmaier (Citation1992). Social risk is measured by four items based on Huy Tuu et al. (Citation2011) and Cunningham and Kwon (Citation2003). Finally, psychological risk is measured by six items based on Zhu and Deng (Citation2020), Huy Tuu et al. (Citation2011), Wong and Yeh (Citation2009), and Floyd and Pennington-Gray (Citation2004). Risk perceptions were all measured using 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the case of general vulnerability we again used a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). Lastly, revisit intentions were again measured, similar to risk perceptions, on a 5-point Likert scale. We used a single item based on Ruan et al. (Citation2020). All items have been adapted to the COVID-19 and cultural heritage context (see ).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of risk perceptions (RP) and revisit intention.

Methods of analyses

We follow Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) and adopt a two-step approach to fit our structural equation model. This involves first testing the measurement model and afterwards the structural model. The two-step procedure fits our goals as we want to confirm both the validity of the used constructs as well as the theoretically grounded implications on revisit intention. Particularly since we constructed the psychological risk perception scale based on different sources. Unidimensionality is what we are looking for when we are measuring the different types of risk perception used in this study. Unidimensionality is explained in Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1982) and stresses the importance of using indicators that measure only one single construct. To achieve unidimensionality of the measurement model, we use a cross validation technique which involves using both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Both techniques are used in two separate sets, which stem from a random split of the total dataset. An exploratory set for EFA (N = 150) and a confirmatory set for both CFA and SEM (N = 320).

In the exploratory set, where the EFA is used, our principle goal is unidimensionality. We use principal axis factoring (PAF) and oblimin rotation for the EFA. Oblimin rotation is used because we expect that the different risk perceptions are correlated. We analyze our results in R version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, Citation2021). The R package we use for EFA is psych version 2.1.3 (Revelle, Citation2021). The R package GPArotation version 2014.11-1 was used for oblimin rotation (Bernaards & Jennrich, Citation2005). When the conditions of unidimensionality have been found in the exploratory set, the resulting measurement model is analyzed in the confirmatory set using CFA. The R package we used for CFA (and later on SEM), is lavaan version 0.6-8.1595 (Rosseel, Citation2012). Because we make use of ordinal indicators, which on some occasions had to be collapsed to 3-point or 4-point scales due to skew, we used the WLSMV estimator. This is a means and variance adjusted diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator and suited for use with ordinal variables with fewer than four categories and/or observed variables that severely violate the normality assumption (Gana & Broc, Citation2019). The R package we used for identifying multivariate outliers based on the Mahalanobis Distance was MASS version 7.3-53.1 (Venables & Ripley, Citation2002).

In order to control for common method variance (CMV), variance introduced by the use of the measurement instrument rather than the respondents’ predispositions, ex-post, we have tried to use a method suggested by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) and include an unmeasured latent common methods factor in our model. This method, however, resulted in an error and we opted for a more common way to control for common method bias by using Harman’s single factor test. This method, which forces all variables to load to a single factor in a PAF analysis, is also discussed in Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003) and in our study the single factor explains 27 percent of the variance of all variables that intended to measure risk perception. This percentage is safely below the 50 percent criterion above which common method variance is expected to be present. Therefore, in the results section only one structural multivariate model is reported.

Results

A descriptive univariate analysis of risk perception and revisit intention for the various datasets used, can be found in .

The measurement model

EFA was used to determine whether the theoretical indicators would merge into the intended risk perception dimension. Where this was not the case, indicators were removed. This process continued until a unidimensional representation of the risk perception dimensions was found. shows the results of the EFA. The exploratory data set (N = 150) and correlation matrix of the variables that would be used for the EFA, had a middling (.79) KMO score according to Kaiser and Rice (Citation1974), making it suitable for analysis using EFA.

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis risk perception dimensions.

The procedure resulted in removal of indicators in three dimensions. We had to remove two social risk indicators: ‘Friends or family members would not think it is unusual when I would visit for example Slot Loevestein right now.’ and ‘Many friends or family members are now inclined to go on daytrips, such as for example Slot Loevestein.’, which happened to be the two reverse-scored indicators of this dimension. We also needed to remove four psychological risk perception indicators: ‘Going on a daytrip is risky right now.’, ‘Visiting a museum is a safe activity.’ (reverse-scored), ‘Safety is the most important aspect a leisure activity can offer.’, and ‘Safety is an important consideration when choosing a leisure activity.’. Lastly, we removed one severity risk perception indicator: ‘COVID-19 is harmful to human health.’. The other three dimensions were left untouched and were reproduced in the EFA. This means that three risk perception dimensions are measured by two indicators. Harvey et al. (Citation1985) argue that the minimum numbers of indicators should be four, however, Hardesty and Bearden (Citation2004) argue that it is more important to consider how broad or narrow the construct itself is.

The second analysis in this first-step involved the CFA on the risk perception dimensions, which showed the following fit indices: χ2(104, n = 320) = 155.811, p = .001; χ2/df = 1.5; CFI = .996; TLI = .995; RMSEA = .040, 90% C.I. (.026–.052), p = .916; SRMR = .040. Following the guidelines of Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), we conclude that the fit indices of the CFA are great (cf. Schreiber et al., Citation2006).

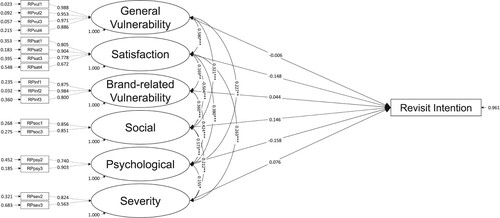

The structural model

The second step involves testing the structural model, which is a very straightforward multivariate model that aims to test whether our theoretical assumption that risk perception will have a negative influence on the revisit intention. shows the model and relevant parameters. The model has the following fit indices: χ2(115, n = 320) = 173.022, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.5; CFI = .996; TLI = .995; RMSEA = .040, 90% C.I. (.027–.052), p = .922; SRMR = .040, which are great (cf. Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Schreiber et al., Citation2006) ().

Hypotheses testing

None of the tested risk perceptions’ effects on revisit intention are significant, which means we reject hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Hypothesis 6 is accepted.

Conclusion and discussion

This study shows how previous visitors of a cultural heritage location perceive risks in the COVID-19 pandemic and how it influences their intentions to revisit the location. Most respondents are convinced that COVID-19 is harmful to human health, but it does not (fully) ruin their mood in daily life. They are confident that Loevestein Castle has taken the right control measures to prevent infection. Moreover, they expect that a visit to the castle would meet their expectations and that the control measures will not have a negative impact on their cultural heritage experience. They feel it is socially accepted if they would visit the castle despite the current pandemic. Despite the fact that the number of COVID-19 infections in the period the study was taken was particularly low, part of the respondents do not really feel comfortable traveling in their own country because they regard a daytrip as rather risky. It seems likely that the respondents have more faith in the cultural heritage location they have visited earlier.

Many previous studies incorporating risk perceptions and behavioral intentions are related to an international travel context. Previous studies show that the relationship between health risk and satisfaction risk perceptions with intentions are unclear; social risk perceptions show a clear negative relationship with intentions, while psychological risk perceptions have no influence on intentions. The context of this study is domestic in nature and related to revisiting a familiar cultural heritage location. None of the six risk perceptions that were included in this study have an effect on revisit intentions. The reason why there are no effects, is not because respondents do not take the effects of COVID-19 seriously enough. On the contrary, they seem to recognize the severe consequences of infection. It is likely that absence of a relationship between the risk perceptions and intentions stems from the fact that the respondents were acquainted with the castle because of previous visits. Although part of the respondents are insecure about traveling and having a day-trip in their own country, they believe that the specific cultural heritage location has taken the right preventive measures. This is in line with a study of Sofaer et al. (Citation2021), which shows that visitors feel more safe at a cultural heritage site than in other public areas during the COVID-19 era. A study of Tsironis et al. (Citation2021) also shows that respondents’ perception of COVID-19 safety measures of a religious cultural heritage location are rather positive. Furthermore, respondents in our study would expect to have a nice experience if they would visit the castle, despite all measures being taken. It seems that familiarity and trust play a crucial role here and it strengthens the importance of establishing relationships with customers. Familiarity is related to previous experiences. Studies show that experienced tourists perceive lower risk levels (Lepp & Gibson, Citation2003), and that familiarity is positively related to repurchase intentions (Gefen, Citation2000; Söderlund, Citation2002). This may be explained because visitors who are familiar with the service offerings, have a different frame of reference in decision-making processes (Söderlund, Citation2002). Trust is related to confidence in expectations often based upon previous experiences, and it leads to lower levels of perceived risks and higher repurchase intentions (Gefen, Citation2000). Overall, in line with other studies, this study suggests the relevance of trust, especially in a pandemic, (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Siegrist et al., Citation2021; Teeroovengadum et al., Citation2021) and the influence of past experiences on intentions (Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998). The role of trust is also confirmed in a study by Sofaer et al. (Citation2021) in a heritage context in the COVID-19 era. Trust in heritage locations may be explained by the idea that ‘the past is safer than the future and the present because it is perceived as fixed, known, and thus reliable’ (Sofaer et al., Citation2021, p. 1126).

The results of this study can be related to stress and coping strategies. Most studies of coping are related to coping with events that occurred in the present or in the past. However, it is also interesting to study future-oriented proactive coping (Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2004; Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, Citation2009) or future-oriented preventive coping (Schwarzer & Knoll, Citation2003). Proactive coping reflects consumer decision-making behavior in the COVID-19 period. How do consumers deal with fear of contamination in making leisure choices? The perception of risks and the evaluation in terms of intentions can be regarded as a form of future-oriented pro-active coping. In leisure literature, stress is defined as subjective hassles occurring during leisure experiences (Schuster et al., Citation2006). In this COVID-19 period, stress may be regarded as the fear of getting contaminated and the hassles to prevent contamination. Because it might be a matter of life and death, this fear is different from regular hassles which have been studied in leisure settings before, such as crowding and stress induced by noise. Fear of contamination will influence consumers’ decision in making leisure choices and to re-attend leisure locations. These intentions will be influenced by several personal and situational factors. The perception of the situation is normative and related to expectations and preferences (Yoon et al., Citation2020). Two separate appraisal processes of stress perception are distinguished (Schuster et al., Citation2006). A primary appraisal reflects the extent to which the situation is stressful. Additional information is gathered for the secondary appraisal. We believe that in our study, as a primary appraisal, some respondents feel reluctant to travel and have day-trips to unknown locations. Because they visited the specific castle location before, they know what to expect and they have trust in the COVID-19 measures taken by the castle. They do not need to gather additional information as part of the secondary appraisal, because they are acquainted with the castle.

Management implications

It is not only important to implement the right hygiene measures to prevent contamination, but also to effectively communicate these measures beforehand, creating trust in the organization. Because leisure services are often intangible, the hygiene measures should become visible, in for example a video. The study further shows the relevance of connecting with previous visitors. It seems to be easier to attract previous visitors again, compared to consumers who are unfamiliar with the location, because they trust the organization in uncertain times. Therefore, it is important to collect customer details during online ticketing processes or (when visitors leave the location) by a digital information terminal. These details should be stored in a customer data platform. This enables the organization to start an interaction with their previous visitors, providing them with relevant information. Engaging visitors will increase the organization’s credibility and visitors’ intentions to revisit the location.

Limitations and future research

Zielinski and Botero (Citation2020) argue that risk perceptions of COVID-19 are related to the number of infected cases and virus deaths. Because our study took place during a period with a relatively low number of positive cases, this could have influenced the results, leading to a non-significant relationship between health risks and intentions. Repeating the study could help determine whether this is the case.

Trust seems to play an important role in how consumers perceive risks. Future studies could focus on trust and risk perceptions, including previous visitors and individuals who have not visited a specific location before. It would also be interesting to profile consumers based on their risk perceptions and compare different clusters to one another. This would provide insights into the size of these clusters and would allow for the creation of risk reduction strategies by both consumers and suppliers of experiences.

Because risk perceptions are situation-specific, it is difficult to make generalizations across different contexts (Roehl & Fesenmaier, Citation1992). This also implies that it is difficult to generalize our findings to another leisure or tourism context. Therefore, it would be interesting to replicate this study in different settings with varying expected levels of familiarity and revisit intentions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pieter de Rooij

Pieter de Rooij (Ph.D.) is a senior lecturer/researcher at Academy for Leisure and Events, Breda University of Applied Sciences (The Netherlands). His research interests are in the field of consumer behaviour, experience marketing, and customer relationship management in the cultural and tourism industry.

Adriaan van Liempt

Adriaan van Liempt (Ph.D.) is a senior lecturer/researcher sociology and research methodology at Academy for Leisure and Events, Breda University of Applied Sciences (The Netherlands). His research interests are in the field of consumer behaviour and social stratification.

Coen van Bendegom

Coen van Bendegom (MSc.) was a lecturer/researcher research methodology at Academy for Leisure and Events, Breda University of Applied Sciences (The Netherlands). His research interests are in the field of consumer behaviour and customer experiences.

References

- Abraham, V., Bremser, K., Carreno, M., Crowley-Cyr, L., & Moreno, M. (2020). Exploring the consequences of COVID-19 on tourist behaviors: Perceived travel risk, animosity and intentions to travel. Tourism Review, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2020-0344

- Adam, I. (2015). Backpackers’ risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tourism Management, 49, 99–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.02.016

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1982). Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 453–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378201900407

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bernaards, C. A., & Jennrich, R. I. (2005). Gradient projection algorithms and software for arbitrary rotation criteria in factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(5), 676–696. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404272507

- Boksberger, P. E., Bieger, T., & Laesser, C. (2007). Multidimensional analysis of perceived risk in commercial air travel. Journal of Air Transport Management, 13(2), 90–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2006.10.003

- Cahyanto, I., Wiblishauser, M., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2016). The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the U.S. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 195–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.09.004

- Cheron, E. J., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1982). Leisure activities and perceived risk. Journal of Leisure Research, 14(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1982.11969511

- Chew, E. Y. T., & Jahari, S. A. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.008

- Choi, K. H., Kim, M., & Leopkey, B. (2019). Prospective tourists’ risk perceptions and intentions to travel to a mega-sporting event host country with apparent risk. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 23(2-3), 97–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2020.1715826

- Cossens, J., & Gin, S. (1995). Tourism and AIDS. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 3(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v03n04_01

- Cunningham, G. B., & Kwon, H. (2003). The theory of planned behaviour and intentions to attend a sport event. Sport Management Review, 6(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(03)70056-4

- Dowling, G. R., & Staelin, R. (1994). A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209386

- Floyd, D. L., Prentice-Dunn, S., & Rogers, R. W. (2000). A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 407–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x

- Floyd, M. F., Gibson, H., Pennington-Gray, L., & Thapa, B. (2004). The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2-3), 19–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v15n02_02

- Floyd, M. F., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2004). Profiling risk perceptions of tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 1051–1054. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.03.011

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 745–774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

- Fuchs, G., & Reichel, A. (2011). An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination. Tourism Management, 32(2), 266–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.01.012

- Gana, K., & Broc, G. (2019). Structural equation modeling with lavaan. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119579038

- Gefen, D. (2000). E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega, 28(6), 725–737. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0483(00)00021-9

- George, R. (2010). Visitor perceptions of crime-safety and attitudes towards risk: The case of Table Mountain National Park, Cape Town. Tourism Management, 31(6), 806–815. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.011

- Gerhold, L. (2020). COVID-19: Risk perception and coping strategies. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xmpk4

- Godovykh, M., Pizam, A., & Bahja, F. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2020-0257

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Greenglass, E. R., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: Testing for mediation using path analysis. European psychologist, 14(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29

- Hardesty, D., & Bearden, W. (2004). The use of expert judges in scale development: Implications for improving face validity of measures of unobservable constructs. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00295-8

- Harvey, R. J., Billings, R. S., & Nilan, K. J. (1985). Confirmatory factor analysis of the job diagnostic survey: Good news and bad news. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(3), 461–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.70.3.461

- Hasan, M. K., Ismail, A. R., & Islam, M. D. F. (2017). Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1412874. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1412874

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huy Tuu, H., Ottar Olsen, S., & Thi Thuy Linh, P. (2011). The moderator effects of perceived risk, objective knowledge and certainty in the satisfaction-loyalty relationship. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(5), 363–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111150017

- ICOM. (2020a). Museums, museum professionals and COVID-19. https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Report-Museums-and-COVID-19.pdf

- ICOM. (2020b). Museums, museum professionals and COVID-19. https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FINAL-EN_Follow-up-survey.pdf

- Jonas, A., Mansfeld, Y., Paz, S., & Potasman, I. (2011). Determinants of health risk perception among low-risk-taking tourists traveling to developing countries. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509355323

- Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 111–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447403400115

- Kim, Y.-J., & Kang, S.-W. (2021). Perceived crowding and risk perception according to leisure activity type during COVID-19 using spatial proximity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020457

- Kozak, M., Crotts, J. C., & Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 233–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.607

- Langelaan, L. (2020, May 20). Voorkom coronaverwarring en bekijk hier de versoepelingen die vanaf 1 juni gelden. Algemeen Dagblad. https://www.ad.nl/binnenland/voorkom-coronaverwarring-en-bekijk-hier-de-versoepelingen-die-vanaf-1-juni-gelden~a63d8afa

- Lee, C.-K., Song, H.-J., Bendle, L. J., Kim, M.-J., & Han, H. (2012). The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.006

- Lepp, A., & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0

- Moreira, P. (2008). Stealth risks and catastrophic risks. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2-4), 15–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n02_02

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

- NEMO. (2021). Follow-up survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on museums in Europe. https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/NEMO_documents/NEMO_COVID19_FollowUpReport_11.1.2021.pdf

- Neuburger, L., & Egger, R. (2020). Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807

- Nield, K., & Nordstrom, A. (2016). Response bias in voluntary surveys: An empirical analysis of the Canadian census. Carleton University, Department of Economics, 22. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/carcarecp/16-10.htm

- Parady, G., Taniguchi, A., & Takami, K. (2020). Travel behavior changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Analyzing the effects of risk perception and social influence on going-out self-restriction. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 7, 100181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100181

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qualtrics. (2021). Qualtrics. In (Version March 2021) Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In (Version 4.0.5) R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Revelle, W. (2021). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. In (Version 2.1.9) Northwestern University. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Rijksoverheid. (2020a, June 16). Aanvullende maatregelen onderwijs, horeca, sport. Retrieved April 8, 2021 from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/15/aanvullende-maatregelen-onderwijs-horeca-sport

- Rijksoverheid. (2020b, May 19). Letterlijke tekst persconferentie minister-president Rutte en minister De Jonge na afloop van crisisberaad kabinet (19-5-2020). Retrieved April 9, 2021, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/mediateksten/2020/05/19/letterlijke-tekst-persconferentie-minister-president-rutte-en-minister-de-jonge-na-afloop-van-crisisberaad-kabinet

- Rijksoverheid. (2020c, June 16). Maart 2020: Maatregelen tegen verspreiding coronavirus, intelligente lockdown. Retrieved April 8, 2021, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/coronavirus-tijdlijn/maart-2020-maatregelen-tegen-verspreiding-coronavirus

- Rijksoverheid. (2020d, June). Positief geteste mensen | Coronadashboard | Rijksoverheid.nl. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://coronadashboard.rijksoverheid.nl/landelijk/positief-geteste-mensen

- Rijksoverheid. (2020e, March 16). Ziekenhuisopnames | Coronadashboard | Rijksoverheid.nl. Retrieved March 17, 2021, from https://coronadashboard.rijksoverheid.nl/landelijk/ziekenhuis-opnames

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Zimmermann, L. (2011). Customer satisfaction with commercial airlines: The role of perceived safety and purpose of travel. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190407

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30(3), 410–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001

- Roehl, W. S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (1992). Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 30(4), 17–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759203000403

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of statistical software, 48(2), 36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Ruan, W., Kang, S., & Song, H. (2020). Applying protection motivation theory to understand international tourists’ behavioural intentions under the threat of air pollution: A case of Beijing, China. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(16), 2027–2041. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1743242

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S. M., Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J., Muñoz-Fernández, G., & Fuentes-García, F. J. (2020). Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1829571

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

- Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2003). Positive coping: Mastering demands and searching for meaning. In S. J. Lopez & C.R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 393–409). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Schuster, R., Hammitt, W., & Moore, D. (2006). Stress appraisal and coping response to hassles experienced in outdoor recreation settings. Leisure Sciences, 28(2), 97–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400500483919

- Siegrist, M., Luchsinger, L., & Bearth, A. (2021). The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Analysis, 41(5), 787–800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13675

- Siongers, J., Verboven, N., Bastiaensen, F., Lievens, J., & Schramme, A. (2020). Cultuurparticipatie in coronatijden. publiq, museumPASSmusées, Kenniscentrum Cultuur- en Mediaparticipatie (UGent-VUB), & Kenniscentrum Cultuurmanagement en Cultuurbeleid (UAntwerpen). https://www.cultuurenmedia.be/images/Publicaties_2020/Cultuurparticipatie_in_coronatijden.pdf

- Söderlund, M. (2002). Customer familiarity and its effects on satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Psychology & Marketing, 19(10), 861–879. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10041

- Sofaer, J., Davenport, B., Sørensen, M. L. S., Gallou, E., & Uzzell, D. (2021). Heritage sites, value and wellbeing: Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic in England. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(11), 1117–1132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1955729

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 171–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803700209

- Teeroovengadum, V., Seetanah, B., Bindah, E., Pooloo, A., & Veerasawmy, I. (2021). Minimising perceived travel risk in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic to boost travel and tourism. Tourism Review, 76(4), 910–928. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2020-0195

- Tsironis, C. N., Sylaiou, S., & Stergiou, E. (2021). Risk, faith and religious tourism in second modernity: Visits to Mount Athos in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2021.2007252

- UNESCO. (2021). Museums around the world in the face of Covid-19. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000376729_eng

- Van den Broek, A. (2021). Wat hebben mensen met cultuur? Culturele betrokkenheid in de jaren tien. What do people have with culture? Cultural involvement in the second decade. SCP.

- Venables, W. N., & Ripley, B. D. (2002). Modern applied statistics with S. Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2

- Wong, J.-Y., & Yeh, C. (2009). Tourist hesitation in destination decision making. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.09.005

- Yoon, J., Kyle, G., Hsu, Y., & Absher, J. (2020). Coping with crowded recreation settings: a cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Leisure Research, 52(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1740630

- Yüksel, A., & Yüksel, F. (2007). Shopping risk perceptions: Effects on tourists’ emotions, satisfaction and expressed loyalty intentions. Tourism Management, 28(3), 703–713. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.025

- Zeithaml, V. A., Bitner, M. J., & Gremler, D. D. (2009). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Zhu, D. S., O’Neal, G. S., Lee, Z. C., & Chen, Y. H. (2009). 2009 International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (Vol. null).

- Zhu, H., & Deng, F. (2020). How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103514

- Zielinski, S., & Botero, C. M. (2020). Beach tourism in times of COVID-19 pandemic: Critical issues, knowledge gaps and research opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197288