ABSTRACT

This paper scrutinizes the media coverage regarding Jahanabad Seated Buddhist statue, in Pakistan, considering both its destruction in 2007 and the subsequent restoration campaign, using content analysis of audio-visual and textual news. Based on 41 online news archives (broadcast on national, regional, and global news outlets), the findings unravel the marginalized narratives of the local community. Digitally mediated community activism appeared as a significant dimension amidst both the destruction and rebuilding periods. Concomitantly, antithetical to the grammar of violence disseminated by radicals, the grammar of compassion emerged. Also based on the content analysis, we found that the tourism value of this heritage asset contributed to its safeguarding and rebuilding. The interplay of these aspects promotes, in a certain way, Jahanabad Seated Buddhist statue as a second-chance tourism site, in in-situ and ex-situ forms. This study offers relevant theoretical, institutional, and managerial implications regarding the site under analysis and other threatened heritage sites.

Introduction

Heritage and terrorism have had turbulent encounters in the last two decades. Notably, vandalism and iconoclasm have been the driving forces behind terrorist attacks on heritage sites in recent years (Ahmed & Oumer, Citation2023). The surge in attacks altered international security politics and necessitated the implementation of a securitization mechanism for the protection of these sites (Christensen, Citation2022). Furthermore, to avoid future escalation among religious groups during cooperation initiatives for the safeguarding of heritage sites, the objectivity of heritage protection has been asserted as central (Isakhan & Akbar, Citation2022). Heritage diplomacy, which is a policy tool of the European Heritage Label (EHL), has been presented as an effective counter-terrorism policy to safeguard heritage assets from conflicts and extend support to non-EU countries as well (Mäkinen et al., Citation2023). Similarly, media sources played a pivotal role in informing and alarming the stakeholders of heritage to activate the resources for the sustainability of these assets and their successive handing over to next generations (Rubio-Tamayo et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2015). The relationship between heritage, terrorism, and the media has been twofold. Conscious of the universal value of heritage, terrorist groups have circulated their terror manifestos worldwide threatening to destroy heritage wonders through all the latest media sources available (Seabra & Paiva, Citation2020). Additionally, negative stereotypes of cultural and theological facets have also been overly associated with communities and religions, accusing them of stimulating, promulgating, and participating in these events.

In tourism, which greatly benefits from the value of heritage assets, acts of violence or vandalism can have differential effects (Groizard et al., Citation2022; Karimi et al., Citation2022; Pizam, Citation1999; Sun & Luo, Citation2022). On the one hand, heritage tourism has been noted as a major contributor to peace during and post-violence as well (Anson, Citation1999; Carbone, Citation2022). On the other hand, violent attempts on heritage assets with claimed embedded motives of religiosity, such as Islamic iconoclasm, i.e. the destruction of religious images as heretical (Clapperton et al., Citation2017; González Zarandona et al., Citation2018; Kabir, Citation2006; Shanna, Citation2020) or political conflicts, as the Arab Spring movement, result in a negative image of the countries. Amplified by the media, these incidents greatly influence the travel decisions of tourists, even with no direct attempts on tourists (Groizard et al., Citation2022). Accordingly, the impacts of crises on destinations have been characterized as macro level on destination development, meso level on tourism business operations, and micro level on tourists (Duan et al., Citation2022).

The activism of community and religious obligations for protecting the heritage of other religions has been less theorized in academic discourse. The media too has been quite biased and partial in disseminating the destruction and attempts at destruction in an increasingly sensationalist manner, while the community role in protecting the heritage and religious teachings in shielding these assets has only been marginally covered (Kearns et al., Citation2019).

Since time immemorial, cultural heritage resources have been subject to certain attempts by radical groups (Fernández, Citation2020). Insights of religiosity and communal dominancy can be seen to have been a factor in several attacks, and these groups have floated the message of religious victory and dominancy over the oppressors and weaker segment of society (Ahmed & Oumer, Citation2023; Barakat, Citation2021). Notable mentions include, but are not limited to, the incident at Babri Mosque – India (Shanna, Citation2020), Bamiyan Buddha – Afghanistan (Margottini, Citation2013), Palmyra – Syria (Kalaycioglu, Citation2020), Dessie – Ethiopia (Ahmed & Oumer, Citation2023); national and international media has covered such incidents in detail and broadcast several audio-visual clips and comprehensive documentaries about these attacks. Such destruction, besides the irreparable damage done, has stigmatized the religions to which these attackers’ groups were putatively affiliated to (Powell, Citation2011). The majority of these groups cite Islam as their primary inspiration, which has led to the stigma of a religion of terror (Kabir, Citation2006), Islamophobia (Al-Ansi et al., Citation2022), and stereotyping of Muslims as terrorists (Downing et al., Citation2022). In fact, the notion of terrorism has been permanently attached with this religion, even though several terrorist groups do affiliate themselves with other religions as well (Harmanşah, Citation2015). For instance, the infamous Christian-inspired atrocities against the Igbo traditional religion in Nigeria ensued in the destruction of numerous heritage sites (Nwashindu & Onu, Citation2022) and the terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch New Zealand resulted in the killing of 51 Muslims (Mortensen, Citation2022). Even so, in theoretical and political debates, allegations against Islam seem to be ever more visible (KhosraviNik & Amer, Citation2022). Such allegations have been continuously refuted by Muslim scholars, and the majority of followers of Islam attempted to demarcate these radical groups from the true teachings of Islam, which respects the rights of non-Muslims and their property as well. However, there have been multiple attempts at destruction of heritage assets, predominantly in the non-Islamic heritage areas in Muslim countries under the justification of Islamic Iconoclasm and religious domination (Atai, Citation2019; Clapperton et al., Citation2017). Several non-state actors, including Taliban and ISIS, have openly claimed the responsibility of such destruction attempts, while disseminating the message of Islamic Iconoclasm (Barakat, Citation2021; Clapperton et al., Citation2017; González Zarandona et al., Citation2018; Harmanşah, Citation2015; Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020; Shahab, Citation2021). Similarly, support has been equally taken from the modern media outlets and channels such as YouTube and TikTok, to spread the ideology of these radical groups quickly (Issa, Citation2021; KhosraviNik & Amer, Citation2022; Marthoz, Citation2017; McDonald, Citation2014). However, to curb widespread propaganda amid hostile circumstances, certain filtration and quantification approaches have been developed to assist the counter-terrorism agencies in the deradicalization process (Sofat & Bansal, Citation2022). Moreover, freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) has been highlighted as a strategy to build a universal consensus on cultural heritage protection in order to overcome the sacrilegious attitude that has contributed to the widespread destruction of heritage monuments worldwide (Thames & Scolaro, Citation2022).

Certain novel dimensions have been unearthed by academics working within theoretical areas pertinent to our inclusion of the subject of digital media iconoclasm (González Zarandona et al., Citation2018). Doing so has synthesized the media with the destruction attempts. In addition, such heritage destruction has been widely corroborated theoretically and covered digitally in the limited geographies of countries like Iraq, Syria, Libya, Egypt, and Afghanistan (Azzouz, Citation2020; Fabiani, Citation2018; Hammer et al., Citation2018; Kila, Citation2019; Matthews et al., Citation2020).

In the country of Pakistan, phases of militancy by Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a destruction drive has been carried out against the historical Buddha statue of Jahanabad, Swat. This campaign’s objectives have been questioned, and resultantly, certain societal and theological dimensions unveiled (Khan & De Nardi, Citation2022). However, the trilateral linkage between heritage destruction, media propagation, and tourism has been minimally contested. Embarking on the same, after four years of plausible restoration campaigns by the Italian Archaeological Mission, ancillary support by the Pakistani government and an active role of the local community, this has led to the successful restoration of this second most iconic Buddhist statue in South Asia after Bamiyan Buddha of Afghanistan.

From the reviewed literature and other sources, it is perceived that Bamiyan Buddha and other heritage destruction incidents have been equally covered in media and academia, while in the case of Jahanabad Buddha Swat, being the second largest in South Asia and equally important, this is partially addressed predominantly in the geopolitical and cultural context of Pakistan. This study thus proposes to analyse the news coverage by national and international media regarding Jahanabad Seated Buddha Swat through media content analysis. This makes it possible to examine the prevailing discourse in the written, audio-visual message of the print and media news reporting, highlighting and focusing on this grey area by analysing the news reporting of local and international media agencies before and after the destruction of Seated Buddha of Jahanabad, Manglor Swat.

This study is structured as follows. After the literature review, the employed methodology is described. Then, results of the content analysis are presented and discussed. The paper ends with theoretical and managerial implications, and future research directions.

Literature review

Heritage destruction and radicals’ manifestos

The frequency of terrorist attacks has grown exponentially in the last decades. Due to its random and unpredictable nature, terrorism is destabilizing safety and security globally threatening civilians’ daily life and all business sectors (Seabra, Citation2023). Tourism is one of the global industries most susceptible to risk factors, especially terrorism. Past research concluded the strong impact of terrorism in tourism demand (Araña & León, Citation2008; Chowdhury et al., Citation2017; Chowdhury & Raj, Citation2018; Pizam, Citation2002; Pizam & Fleischer, Citation2002; Polyzos, Citation2021; Seabra et al., Citation2014; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998). In fact, terrorist organizations are targeting tourism destinations, threatening the sustainable development of tourism businesses and destinations all over the world (Ahlfeldt et al., Citation2015; Baker, Citation2014; Bassil, Citation2014; Bassil et al., Citation2019; Drakos & Kutan, Citation2003; Feridun, Citation2011; Fletcher & Morakabati, Citation2008; Kubickova et al., Citation2019; Lanouar & Goaied, Citation2019; Lutz & Lutz, Citation2018; Masinde et al., Citation2016; McKercher & Hui, Citation2004; O'Connor et al., Citation2008; Radić et al., Citation2018; Teoman, Citation2017; Yaya, Citation2009). The media attention achieved by targeting tourists help terrorist organizations to reach global audiences, making terrorism even more frightening (Avraham, Citation2021; Avraham & Ketter, Citation2008; Barbe et al., Citation2018; Choudhary et al., Citation2020; Spilerman & Stecklov, Citation2009; Taylor, Citation2006; Ulqinaku & Sarial-Abi, Citation2021).

Terrorism has taken a new shift towards destroying heritage sites in order to reach the global audience, particularly in the ongoing universal milieu. Heritage sites are becoming the favoured targets for several terrorist groups operating globally (Seabra & Paiva, Citation2020). Primarily, with the attempts on heritage places having a heritage profile and touristic value, terrorists have been quite successful in gaining the desired publicity and attention since these attempts generate strong emotional impact (Seabra et al., Citation2012). Principally, in the last decade, the terrorists have successfully orchestrated destruction drives on renowned heritage sites and conveyed their message to the worldwide community regarding their embedded goals and objectives (Dib & Izquierdo, Citation2021; Garduño Freeman & González Zarandona, Citation2021; Issa, Citation2021; Rufián Fdez et al., Citation2021; Shahab, Citation2021). It appears that destroying such heritage has drawn a higher intensity of attention and concern of stakeholders of heritage and the international community as well as other interested parties (Spitz, Citation2021). In addition, the terrorists’ attempts on recognized heritage places reveal different aims and motives. Shahab and Isakhan (Citation2018) argued that through these attempts the radicals send a message of power to the outer global stage. Another term, ‘cultural cleansing’, has also been asserted by scholars as an activity causing the loss of identity and belonging of a community and that will culminate in social integration (Bokova, Citation2015).

In addition, the existence of Heritage Protection Laws set by the United Nations Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization (UNESCO) has also been vindictively superseded by means of destruction episodes of terrorist groups (Scovazzi, Citation2021). Through these drives and with the usage of media-oriented audio-visual streaming and textual narratives, the terrorist groups have challenged the global powers and UNESCO’s rhetoric of protecting the heritage assets (Meskell, Citation2002; Seabra & Paiva, Citation2020). It seems that the radical groups understood the potential role of mass communication in transmitting their message of terror to the global audiences in the early stages of the introduction of social media technology (Weimann, Citation2005). In fact, McDonald (Citation2014) commented that such destruction attempts on heritage places and their communication through media have changed the morphology of violence in the existing global milieu. Furthermore, on the side of the institutions, certain sets of legislative measures have also been taken to counter such attacks on heritage places (Fernández, Citation2020). Interestingly, theories have also been corroborated in academia regarding the reverse impact of giving value to the cultural heritage in the result of making it more vulnerable for terrorist attacks (Rosén, Citation2020). In the western context, heritage-preservationism has been argued as another dimension emerging from the notion of destruction and preservation, highlighting certain double standards of appreciation of heritage destruction in the past and denunciation of vandalism and iconoclasm in the ongoing milieu (Holtorf, Citation2006).

The Swat region as a heritage place and tourist destination

Swat, also known as ancient Udyana, is an administrative district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan (Sardar, Citation2012). With exceptional scenic beauty and dubbed the ‘Switzerland of the East’, the Swat valley is nestled at the base of the Hindu Kush mountains, equidistant from Pakistan’s capital city and the eastern border of Afghanistan. A cradle for several peoples and nations (Smith, Citation1924), given the availability of water, productive land, and viable climatic conditions, the Swat valley is one of the most famous archaeological sites of the Buddhist period, also guarding noteworthy remains from ancient Gandhara, Indo-Greek, Hindu-Shahis, and the early Islamic period (Tribulato & Olivieri, Citation2017). Its outstanding cultural heritage attracted both conservation bodies and tourists (Olivieri et al., Citation2019). Fortunately, a majority of excavated sites of aforementioned civilizations are under consistent conservation and sustainability of Directorate of Archaeology and Museums and the Italian Archaeological Mission (Tanweer, Citation2011).

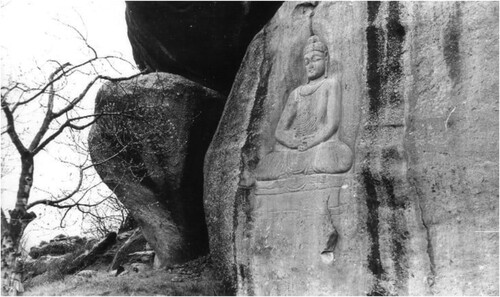

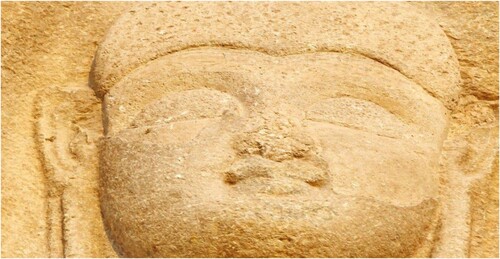

The focal site of this study, the Jahanabad Buddha, at the heart of Malam-jabba, a sub-valley of Swat, represents the Buddhist legacy comprised of Jahanabad Buddha, Nangrial and Tilgram rock carvings, and Malam-jabba stupa (Khan, Citation2011). The narration of Sir Marc Aurel Stein – Hungarian-born British archaeologist – is worthwhile reading in order to understand the significance of Jahanabad Seated Buddha:

Of all the Buddhist relievos found on the rocks near Manglawar and miles up the valley the colossal image of a seated Buddha some thirteen feet in height is certainly the most striking. It is carved on the vertical face of a high reddish rock, high above the narrow terrace at its foot, and is a well-executed piece of work. (Aurel Stein, Citation2014, p. 89)

To facilitate incoming tourists, the hospitality industry, hotels, restaurants, guest houses, camping sites, tour guides, souvenirs shops, and entertainment providers, has witnessed a great deal of development and contributed to the local and national economy. As for tourism demand, there is no official data available specific to the Swat region. However, in Pakistan, tourism had been growing until 2019, when tourism was heavily impacted by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. In 2000, 557,000 international tourists arrived in Pakistan, whereas in 2010, 907,000 international tourist arrivals had been registered, corresponding to an increase of 62.8% (The World Bank, Citation2022) The World Tourism Organization does not have data on international tourist arrivals to Pakistan since 2012, but in a governmental report, the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation mentions 3.580 million international tourist arrivals in 2019, before the precipitous decrease caused by the pandemic. This represents an increase of 295% compared to 2010 (PTDC, Citation2021). According to the World Bank (Citation2022), in 2000, Pakistan's international tourism receipts were 551 million USD; in 2010, they rose to 998 million USD, corresponding to an increase of 84.0%. In 2019, before the pandemic, international tourism receipts reached 992 million USD, a decrease of 2.2% compared to 2010, but still almost double compared to the beginning of the century.

Benefiting from increasing perceived safety, Pakistan was ranked the Best Holiday Destination for 2020 by Condé Nast Traveller (Citation2019). Previously, in 2018, the British Backpacker Society had ranked Pakistan as its top destination for adventure tourism (Jamal, Citation2018), confirming the tourist potential of the country.

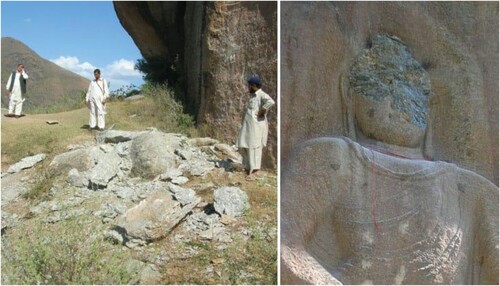

Destruction drive in Swat and Islamic teachings

Insurgency in the Swat from 2007–09, besides casualties, economic loss, social and psychological impacts, has also physically affected heritage places. Once a princely state of the Indian subcontinent, the Swat state has been merged into an administrative territory of Pakistan in 1969, resulting in the creation of certain legislative, judicial, and socio-cultural challenges for the populace (Rome, Citation2011; Sanaullah, Citation2021). Engrained social roots in the geography of Swat have a close connectivity with neighbouring Afghanistan and scores of Afghan refugees arrived in Swat, further worsening the economic conditions of locals. All these factors collectively contributed to the formation of TNSM (Tehreek-i- Nifaaz-i- Shariat-e- Muhammadi) in early 1990, demanding the Islamic Shariah System for the socio-economic balance of Swat. Later, in 2001, the followers of TNSM allied themselves with the Afghan Taliban in the struggle against the United States and coalition troops. The Swat chapter of TNSM has been transferred to Mullah Fazlullah, and in 2007, he established an updated version of TNSM in the form of TTP (Tehreek-e- Taliban Pakistan) (Sanaullah, Citation2021; Stringer, Citation2012). Soon after getting support from local religious groups, the TTP declared an open resistance against the state of Pakistan and initiated attacks against government assets and personnel (Yusuf, Citation2014). In addition, to gain public sympathy and grounded support, the destruction attempt on the Seated Jahanabad Buddha was also carried out in 2007 (De Nardi, Citation2017). Interestingly, the terrorist attempt to destroy the seated Buddha of Jahanabad entails a different message from the insurgents to the public at large and outside world across the borders. Here, the purpose was to achieve the sympathetic edge among Muslims that there will be no room for the remnants of non-Muslim heritage and Swat is a land of Muslims only with the legislative system of so-called ‘Sharia’. In fact, discourse analysis of teachings of Islam, in Holy Quran, Hadith, Sharia and books of Fuqaha, the rights of non-Muslims, their property, and protection rights of their holy worship places have been corroborated multiple times. Critics may be drawn on the bias factor of these above-mentioned citations and narratives. However, even non-Muslims authors have debated the holistic approach of Islam encompassing the non-believers, condemning any violation against the civil rights of non-Muslims as anti-Islamic (Michel, Citation1985). Teachings and practical implications suggest that in the true essence of Islam, there is no such compulsion or motivation to destroy the property or worship places of non-Muslims. Even so, the insurgents have used the destruction of Jahanabad Buddha as a source of earning a place in the hearts of a zealous public. Despite this hope, the reaction of the public has been fiercely opposing and condemnatory of this event. Certain events and clashes among and between the local people and insurgents do occur over the protection of cultural heritage.

Rebuilding Swat and community activism

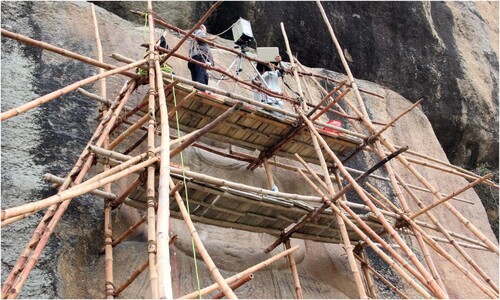

Soon after the military operation against the militants and radical groups in the Swat, there has been an active role played by the government sector, private sector, non-government organizations (NGOs) and Italian Archaeological Mission to rebuild the affected sites and infrastructure (De Nardi, Citation2017; Olivieri et al., Citation2019; Tanweer, Citation2011). It seems that the public at large in Swat has a strong affinity for these cultural assets, even if it belongs to a non-Muslim era and such affinity is beyond the sacrilegious ideology. Their opposition has been exhibited through active participation of restoration campaigns of this seated Buddha. Owing to the unprecedented work of the Italian Archaeological Mission, the state of Pakistan and local community, in 2016, the restoration phase has been completed and the statue of Buddha has again stood steady against all the odds (De Nardi, Citation2017; Lone, Citation2019).

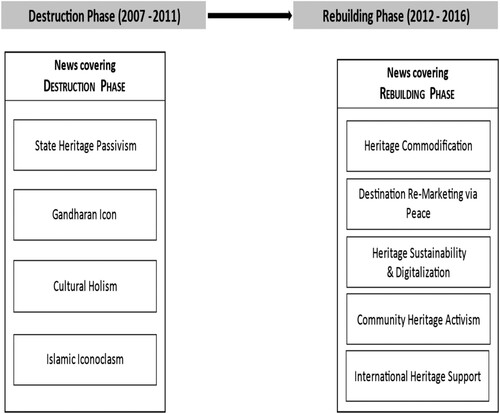

Amid a significant increase in terrorist attacks on heritage sites, particularly in the last two decades, heritage and terrorism have been corroborated extensively. This study furthers this existing body of literature, ascertains the narratives of media amid destruction and rebuilding drives at the JB, and provides the novel avenues leading toward the potential of second-chance tourism ().

Methodology

This exploratory study has investigated the audio-visual and textual material presented in the news about the destruction and restoration of Jahanabad Seated Buddha Swat. Considering the socio-political and cultural importance of the issue, a qualitative research line has been followed for a deeper understanding of the news content broadcast by national, regional, and international news agencies about the destruction and rebuilding of this significant seated Buddha statue in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Such content analysis of media or media content analysis has been frequently adopted as methodology in several studies while contending with such research issues (Ahmad et al., Citation2017). In a similar vein, this study has adopted media content analysis as the research analysis strategy. However, there has been deviation from conventional studies in such a manner that the data collection and data analysis has been divided into two separate segments – the destruction phase and the restoration phase. Audio-visual news in videos and textual summary in newspapers have been analysed in these two phases. Doing so has enabled the researchers to extract etic and emic viewpoints about the destruction and restoration of Jahanabad Buddha Manglor, Swat, answering the research question as to how the media has aired the destruction and restoration of Jahanabad Buddha Swat to the outer world and what has been the embedded message within the content of these news.

Data collection

Data collection for this study has been done in a systematic process of phases, distribution, filtration, and ultimate selection, suitably adopted in both the actions of destruction and restoration. The destruction of this magnificent Buddhist statue was carried out in 2007, and the media covered this incident to 2011, while 2012 is the landmarked year when the rebuilding of this statue has been started and this ended in 2016. Considering this timeline as most important in collecting, assorting, and analysing the news sources, we used the Google (www.Google.com) interface. Official news sources of national, regional, and international media agencies have been collected and analysed. The news sources included both the textual news and audio-visual news. However, in both the phases of destruction and rebuilding, additional filters have been placed to curtail the large number of sources available on Google and to be aligned with the subjectivity of the research issue.

Audio-visual and printed news of internationally and nationally reputed news agencies have been considered to have a wider perspective of the issue in hand. National, regional, and international news agencies which have broadcast the destruction and restoration news of the Jahanabad Seated Buddha Swat, including but not limited to: Aljazeera English, British Broadcasting Corporation BBC English, Agence France-Presse AFP, Arab News, Deutsche Welle DW, Voice of America VOA, Turkish Radio and Television TRT, World Is One News WION, South China Morning Post, while the national media involved; Associated Press of Pakistan APP, Express News, Geo News, Radio Pakistan, Dawn News, The Nation, Express Tribune and several others as well.

Destruction phase

The process of videos and print news selection has been very simplistic. For the destruction phase, we used the search term of ‘Jahanabad Seated Buddha Destroyed in Swat Pakistan’ on the main interface of Google. To this end, Google has explored some 3,610 results, including 30 printed news sources, 45 news videos, and large number of images. In addition to a large number of images, these 75 news sources have been selected in the initial step. However, this number was also comprised of some individually designed documentaries and some repeated and irrelevant sources not falling under the scope of this study. In addition, for the sake of relevance, recognition, and subjectivity, only the relevant, recognized news videos, specifically about the destruction, have been considered. Moreover, period significance of the destruction phase (2007–2011) has further curtailed the number of news sources. This filtration process has curtailed the number of news sources to 14. These 14 sources represented the news sources of the destruction phase ().

Restoration phase

For the restoration phase, we carried out a similar process of news sources selection, however, the search term of ‘Jahanabad Seated Buddha Destroyed in Swat Pakistan’ has been replaced by ‘Jahanabad Seated Buddha Restored in Swat Pakistan’ on the Google search panel. Around 11,000 results have been searched out by Google, containing 44 news videos and 45 printed news and a large number of images. Again, the process of filtration – recognized, relevant, subjective, and falling under the mentioned time slot (2012 – ongoing), has been carried out on this total source of 89. Doing so niched down the sources to 27. In sum, we selected these 27 news sources on the coverage of restoration phases.

In both the phases of destruction and rebuilding, in the final stage, we selected 41 news sources (destruction phase: N = 14; restoration phase: N = 27). All these textual news and audio-visual clips belonged to globally recognized media agencies and reporting organizations (Web information and hyperlinks of these sources are attached in Table ) ().

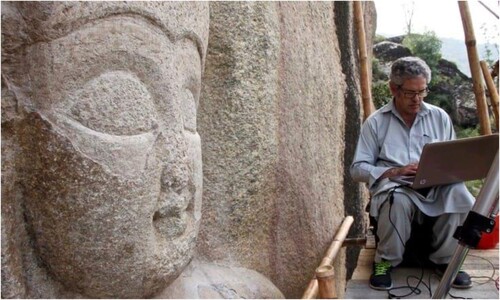

Figure 6. 3D imaging equipment was provided free by the University of Padua, Italy. Source: Dawn News.

Data analysis

Content analysis of the selected videos and print news has been carried out by using NVivo 12. Previous studies on the issue in hand have also been exhaustively consulted resulting in the unveiling of certain dimensions. These deductive dimensions include Community Heritage Activism (De Nardi, Citation2017), Islamic Iconoclasm (Clapperton et al., Citation2017; González Zarandona et al., Citation2018; Harmanşah, Citation2015; Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020), and Islamic Holism (Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020). Prior to themes generation, coding has also been carried out for the videos and texts, labelling the videos as V#1, V#2 … and textual news as N#1, N#2 … . Such labelling has enabled us to identify and elaborate the consulted sources in a more convenient manner. These labels have been extracted, keeping in view the dominant words and phrases repeatedly used in the audio-visual and textual news content. Words such as ‘peace’, ‘peaceful’, and ‘iconic’, and phrases including ‘Islamic militants destroyed’, ‘now restored’, and ‘draw more tourists/tourism’, were identified and highlighted. Doing so enabled the researchers to understand the central concept of the news content in a more thematic paradigm. Moreover, during the theme generation, similar themes have been grouped as well. The data in the videos and written news have been analysed under the preview of the above-mentioned dimensions, however, several new dimensions have emerged. The results section below describes these inductive and deductive dimensions that emerged eventually after the analysis of the news sources.

Results

The analysis of two different phases (destruction and rebuilding) has been divided into two periods. Firstly, the destruction phase ranged from 2007 to 2011, and secondly, the rebuilding phase ranged from 2012 to ongoing. It is noteworthy to mention that the first destruction attempt was initiated in 2007, and in the year of 2012, the first rebuilding campaign was started in a joint venture between Italian Archaeological Mission and the provincial chapter of Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Based on this categorization, the emerged dimensions and their categorization in themes are discussed under the two below headings:

Themes of destruction phase

State’s heritage passivism

News sources broadcast on the undesirable event of destruction have frequent mentions of the inactive role of state’s administrations in protecting this magnificent statue. Despite falling under the territorial jurisdiction of Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, no effective measures have been taken in securing this space from the imprints of militancy period. On top of that, there have been several attempts made by the militant groups to destroy this statue and still the state was unable to prevent this unwanted incident. The news contents on a number of occasions have highlighted the state’s passive approach towards the safety and security of archaeological assets:

Pakistan’s Turmoil Endangers its Archaeological Treasures. (N#1)

In the absence of proper security arrangements, a historic rock-carved image of Buddha has already been destroyed partially. (V#1)

Due to growing insecurity and lack of well-preserved strategy, some of these sites are fast losing its attraction for the foreign tourists coming from different countries. (V#2)

Iconic Gandharan representation

Narrations in textual news and audio-visual streams of video news covering the destruction incident have a compelling orientation towards presenting this statue as one of the most iconic in the country of Pakistan, only ranking second in importance to Bamiyan Buddha of Afghanistan. The historical and figurative significance of this statue has been mentioned in several news contents:

In a grim reminder of destruction of world-famous Buddha statues in Bamiyan by the Afghan Taliban, blasts in Swat’s Buthgarh Jehanabad historical site on Tuesday damaged rocks engraved with Buddha’s images. (N#2)

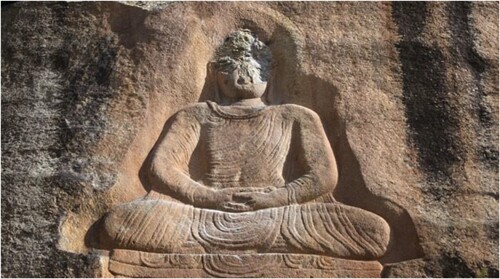

Dating from around the beginning of the Christian era and carved into a 130-foot-high rock, the seated image of the Buddha was second in importance in South Asia only to the Bamiyan Buddha. (N#3)

Now there is only one such statue left – the Buddha of Jehanabad. A beacon of Gandhara heritage, the Buddha of Jehanabad is the only remaining Buddha of its size and quality carved into the rock in the area. Standing at 23 feet, the 7th-century statue is considered the most important carving of its kind. It is unique, the most complete and priceless remains of Gandhara. (N#4)

Cultural holism

The drive of destruction has been encountered by grave condemnation by the local community. The analysis of pictorial and textual presentation reveals the fact that the populace has disproved of this attempt and considered it as culturally inapt and religiously intolerable. Despite having religious heterogeneity with this heritage site, the Muslim community has disliked this attempt and conveyed the tolerant perspective of residing community and strongly perceived this incident as an attack on the historical chronology of culture. The analysis of the news excerpts revealed such holistic stance of the religion of Islam:

Islam teaches us to respect other religions and faith, but unfortunately some elements are disturbing the peace in the Swat valley. (N#5)

Militants are the enemies of culture’, says Abdul Nasir Khan, curator of the museum at Taxila, one of the country’s premier archaeological sites and a former capital of the Gandhara civilization. ‘It is very clear that if the situation carries on like this, it will destroy our cultural heritage. (N#6)

There are many prophets who came before the Prophet Muhammad. Some people here believe Buddha was one of those. He speaks of equality between men, so does Islam. He speaks about love, so does Islam. (N#7)

What people of Pakistan has done with this place, we really admire, and we really thank you on behalf of all Buddhist of the world, says Mr. Phallop Thaiarry (Secretary-General) of The World Fellowship of Buddhists, Thailand. (V#3)

Islamic iconoclasm

Militancy in Swat has been based on the proclaimed philosophy of Islamic Shariah and it remained pivotal in supporting this movement. In the name of Islam, the militants have executed a number of attacks and raids. Similar intention and inclination towards religious affiliation has been narrated in the news sources and this statue has been quoted as non-Islamic. Heritage destruction in Muslim countries or by radicals Muslims has been mainly justified by Islamic iconoclasm (Clapperton et al., Citation2017; De Nardi, Citation2017; González Zarandona et al., Citation2018; Harmanşah, Citation2015; Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020). During the analysis phase, the news contents have repeatedly narrated the dimension of Islamic iconoclasm:

The area has seen a rise in attacks on ‘un-Islamic’ targets in the recent months. (N#8)

A group of armed men arrived in the village late Monday saying they were mujahedeen, or Islamic fighters, and told residents they wanted to blow up the 7-meter statue, said villager Amir Khan. (N#9)

Islamic militants tried to blow up a statue of the Buddha carved into a mountainside in north western Pakistan but did not damage the structure, officials and a witness said Wednesday. (N1#0)

Islamist militants in Pakistan have tried to blow up a seventh-century Buddhist rock carving in an attack reminiscent of the destruction of ancient Buddha statues in Afghanistan six years ago. (N#11)

The analysis of the content, while revealing the Islamic Iconoclasm, has a visible contradiction with the dimension of Cultural Holism. Moreover, the textual or visual, voluntary or involuntary, accusations on militants have resulted in defamation on the religion of Islam as an opposer to the non-Islamic ideology and premises.

Themes of rebuilding phase

Heritage commodification

This section discusses the analysis of news sources containing the coverage of rebuilding phase (2012–2106) and post-rebuilding as well. Reporting of news channels has a dominated element of elaborating the touristic value of this site and the restoration of this statue as a passport to pull arrival of tourists and eventual revenue. To this end, hegemony of commercial value of the site has been visibly demonstrated by the locals, heritage stakeholders, and even the reporters:

The Buddha sits in Jehanabad, the epicentre of Swat's Buddhist heritage, a beautiful valley in the foothills of the Himalayas. There the Italian government has been helping to preserve hundreds of archaeological sites, working with local authorities who hope to turn it into a place of pilgrimage once more and pull in sorely needed tourist dollars. (N#12)

Now popular again locals for its natural beauty, officials are hoping to draw more tourists to its ancient sites and museum. (V#4)

The statue at one time drew a large number of tourists to the Swat valley, including Tibetan pilgrims and archaeology enthusiasts. It is now hoped the restored Buddha statue would once again be able to attract people from all over the world as well as from other parts of Pakistan. (N#13)

Now authorities are counting on the Buddha's recovered smile and iconic status to boost religious tourism from places such as China and Thailand. (N#14)

The Pakistan government is paying special attention to promotion of tourism and has taken a number of steps including easing visa restrictions for the tourists as well as foreign investors for boosting tourism as well as exports … (N#15)

Destination re-marketing through peace

Successful rebuilding of this statue has been corroborated in association with the discussion on the safe and secure conditions of this place. Comparison has also been made in news content between the hostility in the past and peace in the post-rebuilding time. This is to say that the peace has been utilized as a re-marketing tool for the motivation for the potential tourists:

The security situation here in Swat valley is very good and when we came here so the army assisted us everywhere and we feel safe here’, he said, adding that Pakistan had huge potential for tourists with diverse landscapes and rich culture heritage and people from across the world should visit it. (N#16)

The Pakistani army drove the Taliban out of the area, today its once again safe for visitors (V#5)

Now authorities are counting on the Buddha’s recovered smile and iconic status to boost religious tourism from places such as China and Thailand (N#17)

A peaceful environment in the presence of a safe and secure layout at a destination has remained a prior condition in the supply and demand sectors of tourism (Asongu et al., Citation2019; Farmaki, Citation2017). Destination re-marketing through peace seems to be a functional strategy, predominantly in those countries having a history of unrest and violent events. Having said that, the media source of YouTube has been conferred as a marketing tool while destination re-marketing. Peace as a rebranding strategy has been discussed in several studies (Andreas & Hession, Citation2018; Castillo-Villar, Citation2020; Okafor & Khalid, Citation2021). Beside the typological scenario of dark tourism, mostly the tourist destination choice hinges on the peaceful milieu. That is the reason why the reassurance of peace in the Swat has been corroborated to re-divert the attention of potential tourists.

Heritage sustainability and digitalization

In the existing global milieu, heritage sustainability has been supported through technological and digital applications. In addition, the UN Sustainable Development Goal SDG #11 says ‘Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ and its sub-target 11.4 exclaims ‘Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage’ and these have been major guidelines for the sustainability of heritage assets of a country. The analysis depicts the fact that there has been usage of advanced technology (3D-scanning) in the restoration of this seated Buddha image, resulting in the approximate replica. This digitalization has been mentioned a number of times in visual and textual narrations:

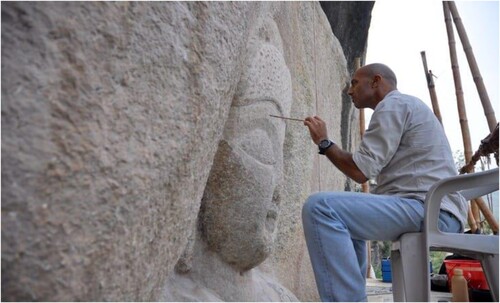

Rehabilitation of the site has not been easy, says Luca Maria Olivieri, an Italian archaeologist who oversaw the restoration of the Buddha. Carried out in phases, it began in 2012 with the application of a coating to protect the damaged part of the sculpture. The reconstruction of the face itself was first prepared virtually in 3D, using laser surveys and old photos. (N#18)

Some of the highly technical and experienced Italian experts worked in the conservation and restoration process using 3-D technology for which we are thankful to them. (N#19)

The reconstruction of the face itself was first prepared virtually in the laboratory, in 3D, using laser surveys and old photos. The last phase, the actual restoration, ended in 2016. Olivieri says the reconstruction is not identical, but that is deliberate, as ‘the idea of damage should remain visible’. (N#20)

Community’s heritage activism

It is quite evident to claim that a community’s heritage activism has been one of the most desirable essentials for the sustainability of heritage assets. Absenteeism of the community from the heritage sustainability campaigns and slogans has resulted in the hindrances for the objectives sets by national and international sustainability organizations. Moreover, the community’s heritage activism has been regarded as a viable panacea for the sustainable life of heritage and its adequate transfer to the next generations. Overall, the populace of Swat has conveyed the message of heritage activism in these news sources. They own the heritage sites, even though these belong to the different religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, and others. In acquiescence to heritage activism, the community has contributed an active voluntary role in the rebuilding of this Buddha statue, as evident in the news contents:

Maulana Shamsur Rehman, a leading Islamist politician in Swat, says the attack on the Buddha should never have happened. Islam preaches freedom and protection for followers of all religions, he told The Associated Press, and ‘in line with Islamic rules, nobody should have an objection to the repair work on the Buddha statue. (N#21)

As Pashtuns, we always welcome our guests’, Saad Khan, a 21-year-old local university student, said. Noting the Swat district's rich history and culture, he also said Buddha structures like the restored rock-carving should not be targeted again … (N#22)

Not a statue, not a statue of stone, this is my culture, they attacked on my culture, they attacked on my history … (N#23)

‘Buddhists believe Buddha visited Swat spiritually, so the region is of paramount importance for his followers’, said Suvastu Arts and Culture Association Chairman Usman Ulas Yar, who actively fought to preserve the archaeology of Swat valley during militant rule … (N#24)

For some, it was a wanton act of vandalism that struck at the heart of the area's unique history and identity. It felt ‘like they killed my father’, says Parvesh Shaheen, a 79-year-old expert on Buddhism in Swat … (N#25)

We don’t hate anybody, any religion — what is this nonsense to hate somebody? (N#26)

… surprised to see Hindu temples in Pakistan well-preserved, an impression that you do not from news media. My visit itself threw up more surprises. I found Pakistan quite different from what I had perceived it to be … (N#27)

International heritage support

Several times, there has been discussion on involvement of an international agency (Italian Archaeological Mission) and its contributing role in restoration of heritage sites in the Swat valley. The international archaeology experts have been framed in videos and written news while working meticulously on restoration of Jahanabad Seated Buddha. This international support for heritage restoration has been celebrated widely in the media news, pointing towards the dependency on international mutual collaboration for heritage sustainability:

Thanks to a team of Italian Archaeologists who carved the Buddha’s face to its original form, residents hope it will revive Swat’s historical legacy. (V#6)

An Italian laid restoration mission has been working here for than six decades … (V#7)

There the Italian government has been helping to preserve hundreds of archaeological sites, working with local authorities. (N#28)

Forced to leave in 2008, Professor Luca has returned to Pakistan to rebuilt Buddhist statue … (V#8)

The Italian Archaeological Mission holds a meritorious history on account of their archaeological expeditions and campaigns. On the unfortunate event of destruction of Jahanabad statue, the Italian government allocated sufficient funding to restore back this significant heritage assets. The news contents, primarily in the post-restoration period, applauded these efforts:

The Italian government invested €2.5 million ($2.9 million) in five years to preserve the cultural heritage and restore the six-meter-tall Buddha of Swat, depicted in a lotus position at the base of a granite cliff. (N#29)

Nine years after its face was destroyed by Taliban militants, the famous Jahanabad Buddha has been restored. In six trips, each lasting a month, an Italian-led team of restorationists has given the Buddha its face back. (N#30)

Dr. Luca Maria Olivieri, head of the Italian Archaeologist Mission in Pakistan, says this region has many riches of antiquity and the authorities need to bring all the historical sites under their supervision. Luca has been working in the country’s Swat Valley for the past 30 years … (N#31)

Similarly, the consistent approach of Italians primarily in the aftermath of destruction through launch of physical restoration campaigns and financial stimulus packages has also been contemplated in the news contents:

An ancient rock carving of the Buddha that was blown up by the Taliban as militants overran Pakistan’s Swat valley a decade ago has been restored after an international effort … (N#32)

the result of repair work that began in 2012 and continued until last fall as part of a project financed through a Pakistani-Italian debt swap agreement … (N#33)

Discussion

In line with the timeline of destruction and rebuilding phases and subsequent selection of news sources, the below-mentioned resultant themes also depict variation in the state’s agenda and militant’s manifestos amid these events. On the part of the community as well, distinguished dimensions emerged as broadcast in the news. For instance, in the destruction phase (2007–11), the analysis of the news contents revealed the fact that administrative authorities remained inactive and passive to protect this Buddha statue from militancy. Moreover, mostly in the news sources, the iconic position of this statue has been mentioned as the second in ranking to the globally recognized Bamiyan Buddha of Afghanistan. Its religious and heritage association has also been contemplated in the contents of news. In addition, a holistic approach of the local community has been recorded, and they seemed to strongly condemn this attack and consider this statue as part of their ancestral legacy. Embarking on the same, the attack on this Buddha figure by the militants has been associated with Islamic Iconoclasm and militants’ motive behind this destruction has been justified by their narratives of declaring this statue as un-Islamic and against the philosophy of Islam. This is that, in news clips and textual narrations, destruction of Bamiyan Buddha has also been discussed to connect this event with that one.

While in the rebuilding phase (2012–2016), the analysis of news sources pointed that restoration of this statue has been foreseen to contribute commercial benefits. Apart from Universal Value of Heritage, this restoration has been quoted to ensure economic stability from tourism activities. Similarly, the eradication of militancy and resulted peace has also been contemplated as a passport for tourist’s arrival. Several quotes have been made to highlight the peaceful milieu of this valley with expectations to pull tourists arrival. In addition, the restoration campaign engrained the state of the art sustainable and digitalized gadgets. Doing so, has been in alignement with the SDG #11 ‘Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ and its sub-target 11.4 which exclaims ‘Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage’. Heritage activism of the local community has also been observed and broadcasted on a number of times and physical assistance and moral support has also been provided by the populace. Rebuilding of this statue has been supported by the community and volunteer participation has also been ensured. This moral consolidation and participation validates the community’s proactive understanding of heritage assets, even though it belongs to other religions and civilizations. Lastly, international support for heritage and involvement of cross-bordered experts has been emphasized as pivotal in the rebuilding of this historical statue. International assistance in monetary terms, physical expertise, and technological cooperation is pointing towards the fulfilment of SDG#17 ‘Partnership for Goals’. However, this support should be more focused towards empowering the community as they are permanent stewards of these heritage sites ().

Conclusions

The encounter of heritage and terrorism has left some of the most unforgettable physical and emotional damage to heritage, to the cost of all mankind. Despite having universal value, heritage assets were, have been, and are even now being relentlessly demolished and looted. Primarily, in the last two decades, radical groups have updated their strategy of communicating such destruction drives via media portals, to reach greater portion of global audiences (González Zarandona et al., Citation2018). In addition, attacks on renowned heritage sites have further energized the manifesto of these groups and credited it as dominant to national and international stakeholders of heritage. Assuredly, the media portals have allocated greater coverage and airtime highlighting such drives and the embedded philosophy of these groups. In the avenue of academia as well, these attacks have been exhaustively brainstormed to unravel the motives and philosophies of doers (Fabiani, Citation2018; Holtorf, Citation2006; Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2015). Despite a plethora of studies, such attempts and their broadcast, and its synergy with the socio-geographical context needed to be researched in a more in-depth manner. In addition, the narratives of local broadcasts in news contents in wake of attacks and in the rebuilding phase, in comparative context, are also required to be explored. This study in the general geography of Pakistan and focal locale of Swat – the heritage jewel of the country, has been selected and the attack on the second largest Buddha statue in South Asia and its rebuilding was the subject issue of probe. National, regional, and international media news in newspapers and audio-visual clips on the destruction and rebuilding of Jahanabad Seated Buddha were gathered and analysed critically in the software package of NVivo 12. Inductive and deductive themes were generated from primary and secondary sources of data. Findings revealed that heritage in Swat has been more prone to commercial value given by national stakeholders and the sustainability dimension was an overlooked dimension. Moreover, atypical to stereotypes of enlisting the heritage as non-Islamic, the local population demonstrated a cultural holistic approach during and after such attacks and publicly denounced the terrorists' moves and participated in the protection and restoration campaigns. This holistic motivation confronts the generic stigma of Islamic Iconoclasm behind such attacks (Clapperton et al., Citation2017; De Nardi, Citation2017; González Zarandona et al., Citation2018; Harmanşah, Citation2015; Rebat Al-kanany, Citation2020), and distinguishes the radical’s manifesto from the broader understanding and perception of the community regarding the importance and credibility of heritage sites. Tehreek-I – Taliban Pakistan TTP, the responsible terrorist’s movement has sought to gain the sympathy of the local community by using the Islamic Iconoclasm as a religious shield to justify this gruesome act. However, the community has refuted this narrative and demonstrated heritage activism. This active approach is in alignment with the tolerant teachings of the religion of Islam emphasizing the protection of heritage assets of non-Muslims in Islamic lands (Michel, Citation1985). On the same front, the militant’s message of power as described by Shahab and Isakhan (Citation2018) has also been challenged by this community’s rhetoric of respecting and sustaining the heritage assets. In a comparative fashion, this community heritage activism may be conceptualized as Digitally Mediated Activism of Community DMAC, which is a contradictory dimension to Digitally Mediated Iconoclasm (González Zarandona et al., Citation2018) and highlights the community perspective amid these attacks and in the rebuilding phase.

In addition to this, this study has also contradicted the grammar of violence as argued (McDonald, Citation2014) and substituted it with the Grammar of Compassion (community side). Concomitantly, another embedded dimension prevailed in the contents of news in the domain of administrative (state) authorities. Superficial appearance of this dimension has been connected to the commodification of heritage or heritage commercialization. However, considering the encompassing hostile milieu and long-run approach, this dimension may be regarded as Heritage’s Touristic Value (HTV). This dimension, besides the immense criticism by the stakeholders of heritage, has an interesting element of heritage shield formation. The more the HTV (state’s level) will be highlighted, additional focus and consideration will be given to the protection and sustainability of heritage site. In case of Jahanabad Buddha, this embedded dimension (HTV) has been observed, primarily in the post-rebuilding period.

Concluding the discussion on analysis and emerging themes (deductive and inductive) of this study, the findings establish a novel framework on the cross-roads of heritage and tourism that is mutually beneficial for the stake of heritage sites and commercial side of tourism as well. New dimensions of Digitally Mediated Activism of Community, Grammar of Compassion and Heritage’s Touristic Value dominate over the agenda of a terrorist’s organization. Similarly, these dimensions in a proactive context, pave the path for second-chance tourism (Bec et al., Citation2021), as this Buddha statue has witnessed some of the unexpected destruction attempts. Now restored back to a condition like before the attack, courtesy of the expertise of Italian Archaeological Mission and 3-D scanning, this site offers insight into the heritage tourism potential in in-situ and ex-situ (Bec et al., Citation2021) capacity.

Theoretical implications

For academia, this study stretches a scheme for further studies to unveil novel avenues. Emergence of novel themes in heritage destruction and rebuilding would expand the understanding of scholars working on this issue to consider the marginalized voices of community against the heritage destruction and active participation in rebuilding the heritage sites. In a similar context, this study demarcates between the radical approach of Islamic groups and a moderate version. This distinction is important to obliterate the religious dogma and stigma commonly designated to Islam. While unravelling the embedded perspectives of community, stakeholders, and third-party media agencies amidst the destruction and rebuilding phases, this study makes its academic position in an obvious way. Dimensions of cultural holism and community heritage activism may prove significant in future heritage research to understand the heritage destruction and rebuilding scenarios.

Institutional and managerial implications

This study entails implications deemed suitable for the institutions to consider. While allowing the institutional stakeholders to revisit the heritage protection strategies, this endeavour guides towards inculcating the community’s cultural and sentimental association with heritage sites in the heritage protection and promotion notions. For heritage custodianship, this study points towards the community’s inclusiveness in decision-making. Comparative to the state’s administrative authority to protect the heritage, a more realistic and sustainable heritage stewardship would be achieved while emphasizing on the cultural and sentimental liaison of the community with this heritage site. Primarily, amidst human-induced crises and natural disasters in developing countries having limited sources to protect and sustain every heritage site, this frontline shield may prove exemplary and effective.

For tourism stakeholders, this study underlays the cornerstones to simultaneously cope with the commercial and valuation aspect of heritage. The notion of commoditization of heritage may be proactively utilized to formulate a heritage protection shield. Avenues of heritage sustainability on the roadmap of SDGs have also been sketched out in this study. These avenues may be focused on the upcoming management plans and executions to mutually progress on the sustainability of heritage and its commercial potential – a proposed agenda of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015.

Limitations and future directions

This study contains contextual, theoretical, and methodological limitations. Future endeavours may build on these to unearth novel avenues. First, it is limited to the news sources broadcast on the destruction and rebuilding of this iconic statue. Further expansion may be made on contextual and methodological fronts through including other heritage sites and choosing a quantitative strategy. Second, this study has emphasized only the destruction and rebuilding phases. Further studies may stretch the analysis timeline to the pre-destruction period to cover historical understanding of the issue under consideration. Third, this study is constrained to the Buddhism heritage in an Islamic locale, making it quite complex to generalize to the other heritage places belonged to other religions and ethnicities. Fourthly, this study has considered the platforms of Google, News Blogs, and YouTube, and further studies incorporating other social media forums including Facebook, Twitter, Flicker, and Instagram are recommended ().

Table 1. Links to audio-visual and print news sources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Farhad Nazir

Farhad Nazir is a PhD student in Tourism, Heritage, and Territory at Department of Geography and Tourism, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Coimbra, Portugal. He is also a collaborative member of Centre of Studies on Geography and Spatial Planning CEGOT, University of Coimbra. His research interests gravitate around social media and destination branding, cultural tourism, tourism laws, and hospitality legislation. His writings appeared in Qualitative Market Research, International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, and Journal of Asian Civilization.

Ana Maria Caldeira

Ana Maria Caldeira is an Assistant Professor in the Tourism and Geography Department at Faculty of Arts and Humanities (University of Coimbra, Portugal) and a researcher at the Centre of Studies on Geography and Spatial Planning (CEGOT) research unit. She holds a degree in International Relations (ISCSP – University of Lisbon), a Master and a PhD in Tourism (University of Aveiro). Her research interests are cultural attractions, and consumer experience and behaviour in cultural and urban tourism contexts. She has published in journals such as International Journal of Hospitality Management, Tourism Geographies, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, and Journal of Vacation Marketing.

Cláudia Seabra

Cláudia Seabra is a Professor in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, where she coordinates the PhD in Tourism, Heritage, and Territory. She has published more than 100 titles, some of them in the Journal of Business Research, Tourism Management, Annals of Tourism Research, International Journal of Tourism Cities, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Management, ANATOLIA, and the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, among others. Also, she has edited two books for EMERALD Publishing about Risks and Safety in Tourism. She is affiliated with the CEGOT – Geography and Spatial Planning Research Centre. Her research interests are risk and safety in tourism.

References

- Abbott, O. (2020). From holism and individualism to a relational perspective on the sociology of morality. In O. Abbott (Ed.), The self, relational sociology, and morality in practice (pp. 83–111). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31822-2_4

- Ahlfeldt, G., Franke, B., & Maennig, W. (2015). Terrorism and international tourism: The case of Germany. Journal of Economics and Statistics, 235(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2015-0103

- Ahmad, U., Zahid, A., Shoaib, M., & AlAmri, A. (2017). Harvis: An integrated social media content analysis framework for YouTube platform. Information Systems, 69, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2016.10.004

- Ahmed, M. J., & Oumer, A. A. (2023). The impacts of armed conflicts on the heritage tourism of Dessie and its environs, Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 18(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2022.2145899

- Al-Ansi, A., Chua, B.-L., Kim, C.-S., Yoon, H., & Han, H. (2022). Islamophobia: Differences across Western and Eastern community residents toward welcoming Muslim tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 439–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.04.018

- Andreas, N., & Hession, G. J. (2018). Conceptualising the tourism–disaster–conflict nexus. In A. Neef & J. H. Grayman (Eds.), The tourism–disaster–conflict nexus (pp. 1–31). Emerald Publishing.

- Anson, C. (1999). Planning for peace: The role of tourism in the aftermath of violence. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800112

- Araña, J., & León, C. (2008). The impact of terrorism on tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.08.003

- Arensberg, C. (1981). Cultural holism through interactional systems. American Anthropologist, 83(3), 562–581. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1981.83.3.02a00040

- Asongu, S. A., Nnanna, J., Biekpe, N., & Acha-Anyi, P. N. (2019). Contemporary drivers of global tourism: Evidence from terrorism and peace factors. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1541778

- Atai, J. (2019). The destruction of Buddhas: Dissonant heritage, religious or political iconoclasm?. Tourism Culture and Communication, 19(4), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.3727/194341419X15554157596173

- Aurel Stein, M. (2014). On Alexander’s track to the Indus. Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.pt/books?id=lTTKBAAAQBAJ

- Avraham, E. (2021). Combating tourism crisis following terror attacks: Image repair strategies for European destinations since 2014. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(8), 1079–1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1764510

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2008). Will we be safe there? Analysing strategies for altering unsafe place images. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 4(3), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2008.10

- Azzouz, A. (2020). Re-imagining Syria. City, 24(5–6), 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1833536

- Baker, D. M. A. (2014). The effects of terrorism on the travel and tourism industry. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 2(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7VX3D

- Barakat, S. (2021). Necessary conditions for integrated approaches to the post-conflict recovery of cultural heritage in the Arab World. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(5), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1799061

- Barbe, D., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2018). Destinations’ response to terrorism on Twitter. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 4(4), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-04-2018-0027

- Bassil, C. (2014). The effect of terrorism on tourism demand in the Middle East. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 20(4), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2014-0032

- Bassil, C., Saleh, A., & Anwar, S. (2019). Terrorism and tourism demand: A case study of Lebanon, Turkey and Israel. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1397609

- Bec, A., Moyle, B., Schaffer, V., & Timms, K. (2021). Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tourism Management, 83, 104256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104256

- Behrendt, K. A. (2007). The art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Blumberg, B. S. (1964). Goiter in Gandhara: A representation in a second to third century AD Frieze. Journal of the American Medical Association, 189(13), 1008–1012. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1964.03070130028008

- Bokova, I. (2015). Culture on the front line of new wars. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 22(1), 289–296. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24591015

- Burgess, J. (1900). The Gandhara sculptures. The Journal of India Art and Industry, 8(1), 61–69. https://dspace.gipe.ac.in/xmlui/handle/10973/35130?show=full

- Carbone, F. (2022). ‘Don’t look back in anger’. War museums’ role in the post conflict tourism-peace nexus. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(2–3), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1901909

- Castillo-Villar, F. R. (2020). Destination image restoration through local gastronomy: The rise of Baja Med cuisine in Tijuana. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(4), 507–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-03-2019-0054

- Choudhary, S. A., Khan, M. A., Sheikh, A. Z., Jabor, M. K., bin Nordin, M. S., Nassani, A. A., Alotaibi, S. M., Abro, M. M., Vo, X. V., & Zaman, K. (2020). Role of information and communication technologies on the war against terrorism and on the development of tourism: Evidence from a panel of 28 countries. Technology in Society, 62, Article 101296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101296

- Chowdhury, A., & Raj, R. (2018). Risk of terrorism and crime on tourism industry. In M. Korstanje, R. Raj, & K. Griffin (Eds.), Risk and safety challenges for religious tourism and events (pp. 26–34). Cabi.

- Chowdhury, A., Razaq, R., Griffin, K. A., & Clarke, A. (2017). Terrorism, tourism and religious travellers. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 5(1), 1–19.

- Christensen, M. E. B. (2022). The cross-sectoral linkage between cultural heritage and security: How cultural heritage has developed as a security issue? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(5), 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2054845

- Clapperton, M., Jones, D. M., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). Iconoclasm and strategic thought: Islamic State and cultural heritage in Iraq and Syria. International Affairs, 93(5), 1205–1231. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix168

- Clini, P., Quattrini, R., Nespeca, R., Angeloni, R., & Mammoli, R. (2020). Digital facsimiles of architectural heritage: New forms of fruition, management and enhancement. The exemplary case of the Ducal Palace at Urbino. In L. Agustín-Hernández, A. Vallespín Muniesa, & A. Fernández-Morales (Eds.), Graphical heritage (pp. 571–582). Springer International Publishing.

- Condé Nast Traveller. (2019, December 5). The 20 best holiday destinations for 2020 | Condé Nast Traveller [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d18T5ypYzgM

- De Nardi, S. (2017). Everyday heritage activism in Swat Valley: Ethnographic reflections on a politics of hope. Heritage & Society, 10(3), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2018.1556831

- Dib, A., & Izquierdo, M. A. R. (2021). Terrorism and the loss of cultural heritage: The case of ISIS in Iraq and Syria. In O. Niglio & E. Y. J. Lee (Eds.), Transcultural diplomacy and international law in heritage conservation: A dialogue between ethics, law, and culture (pp. 377–393). Springer Singapore.

- Donghui, C., Guanfa, L., Wensheng, Z., Qiyuan, L., Shuping, B., & Xiaokang, L. (2019). Virtual reality technology applied in digitalization of cultural heritage. Cluster Computing, 22(4), 10063–10074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-017-1071-5

- Downing, J., Gerwens, S., & Dron, R. (2022). Tweeting terrorism: Vernacular conceptions of Muslims and terror in the wake of the Manchester Bombing on Twitter. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 15(2), 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2021.2013450

- Drakos, K., & Kutan, A. (2003). Regional effects of terrorism on tourism: Evidence from three Mediterranean countries. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 47(5), 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002703258198

- Duan, J., Xie, C., & Morrison, A. M. (2022). Tourism crises and impacts on destinations: A systematic review of the tourism and hospitality literature. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(4), 667–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348021994194

- Dupeyron, A. (2020). The cultural turn in international aid: Impacts and challenges for heritage and the creative industries. Public Archaeology, 19(1–4), 73–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14655187.2020.1841510

- Fabiani, M. D. (2018). Disentangling strategic and opportunistic looting: The relationship between antiquities looting and armed conflict in Egypt. Arts, 7(2), https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7020022

- Farmaki, A. (2017). The tourism and peace nexus. Tourism Management, 59, 528–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.012

- Feridun, M. (2011). Impact of terrorism on tourism in Turkey: Empirical evidence from Turkey. Applied Economics, 43(24), 3349–3354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036841003636268

- Fernández, L. (2020). The impact of international terrorism on cultural heritage in Spain. PASOS: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 18(4), 559–569. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20203475411. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2020.18.040

- Fletcher, J., & Morakabati, Y. (2008). Tourism activity, terrorism and political instability within the Commonwealth: The cases of Fiji and Kenya. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(6), 537–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.699

- Garduño Freeman, C., & González Zarandona, J. A. (2021). Digital spectres: The Notre-Dame effect. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(12), 1264–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1950029

- Ghani-ur-Rahman, & Younas, S. (2018). Buddha’s miracles at Śrāvasti: Representation in Gandhara Sculpture, socio-religious background and iconographic symbolism. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 12(1), 203–226. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=132086516&lang=pt-pt&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- González Zarandona, J. A., Albarrán-Torres, C., & Isakhan, B. (2018). Digitally Mediated Iconoclasm: The Islamic State and the war on cultural heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(6), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1413675

- Groizard, J. L., Ismael, M., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2022). Political upheavals, tourism flight, and spillovers: The case of the Arab Spring. Journal of Travel Research, 61(4), 921–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211002652

- Hammer, E., Seifried, R., Franklin, K., & Lauricella, A. (2018). Remote assessments of the archaeological heritage situation in Afghanistan. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 33, 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.12.008

- Harmanşah, Ö. (2015). ISIS, heritage, and the spectacles of destruction in the global media. Near Eastern Archaeology, 78(3), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.5615/neareastarch.78.3.0170

- Holtorf, C. (2006). Can less be more? Heritage in the age of terrorism. Public Archaeology, 5(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1179/pua.2006.5.2.101

- Isakhan, B., & Akbar, A. (2022). Problematizing norms of heritage and peace: Militia mobilization and violence in Iraq. Cooperation and Conflict, 57(4), 516–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367221093161

- Issa, S. (2021). Picturing atrocity: Visual representations of ISIS in Arabic political cartoons. Visual Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2020.1866441

- Jamal, S. (2018, November 30). British adventurers back to explore Pakistan’s mountains. Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/british-adventurers-back-to-explore-pakistans-mountains-1.60605937

- Kabir, N. (2006). Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Australian media, 2001–2005. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 26(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360200060114128

- Kalaycioglu, E. (2020). Aesthetic elisions: The Ruins of Palmyra and the “good life” of liberal multiculturalism. International Political Sociology, 14(3), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa004

- Karimi, M. S., Khezri, M., & Razzaghi, S. (2022). Impacts of regional conflicts on tourism in Africa and the Middle East: A spatial panel data approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(10), 1649–1665. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1931054

- Kearns, E. M., Betus, A. E., & Lemieux, A. F. (2019). Why do some terrorist attacks receive more media attention than others?. Justice Quarterly, 36(6), 985–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1524507

- Khan, M. S., & De Nardi, S. (2022). The affectual-social ecology of cultural artefacts: Illegal markets and religious Vandalism in Swat Valley, Pakistan. Forum for Social Economics, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2022.2084440

- Khan, R. (2011). Visual iconicity along the ancient routes Buddhist heritage of the Malam-Jabba Valley (Swat). Journal of Asian Civilizations, 34(1), 203–215. https://www.proquest.com/openview/ddf8265e6a32a916eb66084d02f485b9/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=105703

- KhosraviNik, M., & Amer, M. (2022). Social media and terrorism discourse: The Islamic State’s (IS) social media discursive content and practices. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(2), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1835684

- Kila, J. D. (2019). Iconoclasm and cultural heritage destruction during contemporary armed conflicts. In S. Hufnagel & D. Chappell (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook on art crime (pp. 653–683). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54405-6_30

- Kitungulu, L. (2013). Collaborating to enliven heritage collections. Museum International, 65(1–4), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/muse.12043

- Kubickova, M., Kirimhan, D., & Li, H. (2019). The impact of crises on hotel rooms’ demand in developing economies: The case of terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the global financial crisis of 2008. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 38, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.10.002

- Lanouar, C., & Goaied, M. (2019). Tourism, terrorism and political violence in Tunisia: Evidence from Markov-switching models. Tourism Management, 70, 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.002

- Leeman, J., Rabin, L., & Román–Mendoza, E. (2011). Identity and activism in heritage language education. The Modern Language Journal, 95(4), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01237.x

- Lone, A. G. (2019). The scope of the Buddhist ‘workshops’ and artistic ‘centres’ in the Swat Valley, ancient Uḍḍiyāna, in Pakistan. In W. Rienjang & P. Stewart (Eds.), The geography of Gandhāran Art (pp. 107–120). Archaeopress Archaeology.

- Lutz, B., & Lutz, J. (2018). Terrorism and tourism in the Caribbean: A regional analysis. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 12(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2018.1518337

- Maior-Barron, D. (2019). Let them eat macarons? Dissonant heritage of Marie Antoinette at Petit Trianon. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(2), 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1475411

- Mäkinen, K., Lähdesmäki, T., Kaasik-Krogerus, S., Čeginskas, V. L. A., & Turunen, J. (2023). EU heritage diplomacy: Entangled external and internal cultural relations. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 29(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2022.2141722

- Margottini, C. (2013). After the destruction of giant Buddha statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO’s emergency activity for the recovering and rehabilitation of cliff and niches. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Marthoz, J. P. (2017). Terrorism and the media: A handbook for journalists. UNESCO Publishing.

- Masinde, B., Buigut, S., & Mung’atu, J. (2016). Modelling the temporal effect of terrorism on tourism in Kenya. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(12), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v8n12p10