ABSTRACT

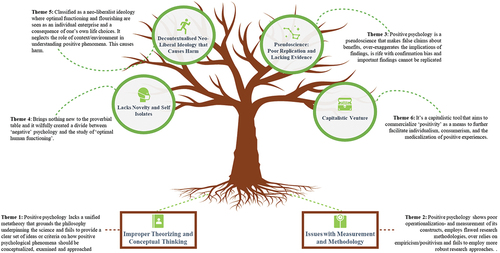

The purpose of this systematic literature review was to explore the current critiques and criticisms of positive psychology and to provide a consolidated view of the main challenges facing the third wave of research. The review identified 32 records that posed 117 unique criticisms and critiques of various areas of the discipline. These could be grouped into 21 categories through conventional content analysis, culminating in six overarching themes or ‘broad criticisms/critiques’. The findings suggested that positive psychology (a) lacked proper theorizing and conceptual thinking, (b) was problematic as far as measurement and methodologies were concerned, (c) was seen as a pseudoscience that lacked evidence and had poor replication, (d) lacked novelty and self-isolated itself from mainstream psychology, (e) was a decontextualized neoliberalist ideology that caused harm, and (f) was a capitalistic venture. We briefly reflect on the findings and highlight the opportunities these criticisms and critiques present.

Introduction

Psychology is in the midst of a crisis of confidence (Efendic & Van Zyl, Citation2019). The last decade has brought about fundamental challenges to the scientific integrity of the discipline, questions about its preferred methodologies, and concerns relating to the validity of its analytical methods (Camerer et al., Citation2018; Klein et al., Citation2018; Nosek et al., Citation2015). Failures to replicate the findings of formative works in psychology, the high profile incidence of academic fraud (e.g., the Diederik Stapel situation), and the increasing occurrence of questionable research practices have cast a shadow of doubt over the credibility of the discipline in a very public manner (Engber, Citation2017; Klein et al., Citation2018). The causes of the credibility crisis have been subjected to much debate, ranging from publication bias and a lack of transparency, to an overreliance on small, underpowered samples (Efendic & Van Zyl, Citation2019). Although these issues originally stemmed from cognitive and social psychology, criticisms and critiques of credibility have spread to every subdiscipline in psychology (Efendic & Van Zyl, Citation2019; Nuijten et al., Citation2016).

As one of the most rapidly expanding branches of the discipline, positive psychology (PP) is not immune to the credibility crisis (Van Zyl & Rothmann, Citation2022). Despite its rapid expansion during the last two decades, there is growing concern about its relevance, impact, and credibility as a science (Van Zyl & Rothmann, Citation2022). Specific criticisms and critiques have been posed of the distinctive contribution of the paradigm and the validity of the philosophy, theories, methodologies, and interventions on which it is built. Van Zyl and Rothmann (Citation2022) summarized some of the critiques of critics by highlighting that (a) positive psychology is built on poor metatheoretical assumptions, (b) that constructs within the discipline suffer from the jinglejangle fallacy, (c) that positive psychology favors poor methodologies and uses ‘quick and dirty’ assessment measures, (d) that it is culturally biased, (e) that it hides behind the complexity of statistical analysis to present complex solutions to simple problems, and (f) that its interventions do not show sustainable results. Although not all of these criticisms are unique to positive psychology, they have sparked debates on the future of the discipline and questions about how to strengthen its complexity (Lomas et al., Citation2021; Wong, Citation2011).

Drawing on these original criticisms, Lomas et al. (Citation2021) introduced the concept of waves or phases that positive psychological research had experienced, as it had grown more nuanced. Lomas and Ivtzan (Citation2016) describe how the first wave was an introduction of the field, with a somewhat simplified inclusion of more positive approaches to understanding flourishing and wellbeing. Lomas and Ivtzan (Citation2016) then posit that a second wave of positive psychology, what Wong (Citation2011) calls positive psychology 2.0, introduced a more dialectic view of flourishing that embraced the complex and dynamic nature of positive and negative experiences. They show how not all ‘positive’ approaches lead to positive outcomes (e.g., optimism) and not all ‘negative’ approaches lead to negative outcomes (e.g., posttraumatic growth). More recently, Lomas et al. (Citation2021) indicated that positive psychology had entered a third wave of research aimed at broadening beyond the individual to include systems, contexts, and cultures, using a wider range of methodologies and a more interdisciplinary approach. As is always the case with paradigmatic waves within a discipline, each succeeding wave represents a response to critiques of the preceding wave. This progression over time lends itself to a more nuanced, sophisticated, and better-informed literature. It may be a bit bold to say that positive psychology is on the front end of a revolution (Kuhn, Citation1970), but the increased complexity and scholarly sophistication – bred from critiques and criticisms of earlier waves – is arguably improving the field.

Therefore, there is value in reflecting on the criticisms and critiques of the field in order to facilitate its growth and development as a science. From these criticisms and critiques, new or unique opportunities might emerge, which could strengthen the scientific value proposition of the discipline and facilitate a new wave of revolutionary ideas. However, there is currently no consolidated view of the contemporary criticisms and critiques of positive psychology posed. A clear overview is needed to set the stage for the third wave of positive psychological research (Van Zyl & Salanova, Citation2022).

Purpose of the present review

The purpose of this systematic literature review was to identify, summarize, and explore current critiques and criticisms of positive psychology and provide a consolidated view of the main challenges facing what Lomas et al. (Citation2021) designated as the third wave of positive psychology. Recognizing that the number of individual critiques would likely be quite large, our goal was to summarize the critiques at the level of broad themes. Although summarizing our findings using themes introduces a level of abstraction, our purpose was to present a broad overview of the types of critiques that have been leveled against positive psychology within the literature. We alert readers to individual critiques, but a detailed discussion of each critique falls outside our scope. Furthermore, we aimed to capture the critiques without assigning weights to the critiques based on criteria like journal impact factor. In doing so, we anticipated that the critiques may vary in how fair, compelling, or applicable to the full body of positive psychology research they are. Our approach was to provide a descriptive overview of the critiques first, then respond with a discussion of each theme. Our view is that ultimately it is for the field to respond to the criticisms in the research that follows; our aim is to simply offer a consolidated sweep of the critiques that we hope serves as a touchpoint to guide and inform that work.

This paper is structured as follows. First, we describe in detail the methods that guided our review. Next, we present the criticisms and critiques identified in the review, clustered into overarching themes. Our aim within this section was to present the themes in a descriptive rather than evaluative manner. We close with a discussion of the themes, pointing to future directions for research that will serve to address the most salient criticisms and critiques.

Methodology

Research approach

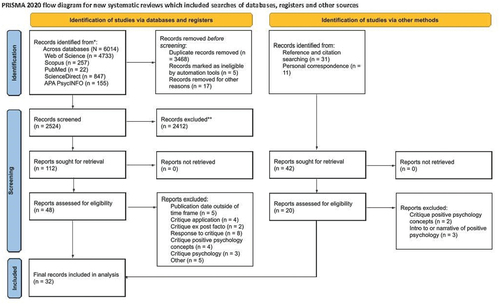

A systematic literature review was employed to explore the contemporary critiques and criticisms posed of positive psychology. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines were used to enhance the transparency, clarity, and credibility of the systematic review by providing a clear protocol or ‘checklist’ of the components to be reported (Page et al., Citation2021). Based on the guidelines, we developed and applied a clear data extraction and classification taxonomy that defined the extent of the search, the eligibility criteria, the data analytical framework, and how disagreements between researchers would be managed in our attempt to identify the criticisms and critiques of positive psychology.

Eligibility criteria

To determine the eligibility of manuscripts to be included in the study, clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were set at the start of the project. To be included, manuscripts needed to be (a) specifically focused on critiquing or criticizing positive psychology as a discipline or field as a whole, (b) theoretical work, (c) published between 2010 and 2022,Footnote1 (d) in English, and (e) published in academic peer-reviewed journals or scientific books.

In contrast, manuscripts were excluded from further consideration for the following reasons: (a) if the purpose of the paper was not specifically focused on a critique or criticism of positive psychology, (b) if a critique or criticism was mentioned ex post facto or as a way to frame the paper, (c) if it was an ‘introduction’ or narrative paper, where critiques/criticisms were framed as part of a historical overview, or (d) if it was published in a non-English format. We also excluded manuscripts (e) that were grey literature or a non-peer-reviewed text (e.g., popular psychology or management books, practitioner-focused non-academic journals, or conference proceedings), (f) that were unpublished master’s or doctoral theses, or (g) that were textbooks, textbook chapters, or other books that had not undergone peer review, because we wanted to include only manuscripts that had been subjected to a rigorous peer review process. Furthermore, we excluded manuscripts (h) if the focus was on solutions to problems/critique/criticism rather than on the critiques/criticisms themselves, or (i) if it provided a response to a criticism/critique. These choices were made because coverage of identified criticisms and critiques were generally quite brief in these papers (presumably to provide sufficient space for the proposed solution or response), and also because manuscripts in these categories did not introduce unique critiques that were not already identified in the papers that were included. Finally, we excluded manuscripts (j) if the critique/criticism of positive psychology applied to a specific field (e.g., career development, organizations, or psychotherapy), or (k) if it was focused on a specific concept (e.g., happiness, strengths, or grit) or intervention, rather than positive psychology as a field. These choices were made because critiques of specific fields or concepts, while relevant, extend the scope of the paper beyond our desired focus on the discipline as a whole.

Search strategy

Between December 2021 and January 2022, a comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted in the following databases: Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, APA PSYCHInfo, and ScienceDirect. To identify the appropriate literature, a set of primary search terms (e.g., ‘positive psychology criticisms’, ‘positive psychology critiques’) and their variants were applied (cf. the supplementary material section for a full list of search terms). A subsequent search was conducted after that, where secondary search terms were first entered into the search query – ‘criticisms’, ‘critiques’ – followed by a series of tertiary terms. Using these search terms, 6 014 titles were identified from 2010 to 2021.

Selection process

Based on Mohamed Shaffril et al.’s (Citation2021) guidelines, the study selection process was divided into five distinct phases and actioned by the entire research team (cf. the supplementary material section for more details). First, based on the search terms, an initial search was conducted independently by two of the authors, and basic manuscript details were captured in Zotero (database, item type, publication year, author, title, publication title, doi, abstract, pages, issue, volume, and ISBN/ISSN). The two datasets were merged and subsequently screened and cleaned, and duplicates were removed. A total of 2 524 records were retained for further screening. Second, the titles and abstracts of the manuscripts were screened and tested against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria by four authors. In total, 2 412 records were subsequently excluded, resulting in 48 full records eligible for inclusion. Third, the full texts of those papers identified via title and abstract screening (n = 48) were then read and assessed against the eligibility criteria. Thirty-one records were excluded for the following reasons: publication date outside of time frame (n = 5), critique application (n = 4), critique ex post facto (n = 2), response to critique (n = 8), critique of positive psychology concepts (n = 4), critique psychology (n = 3), and other (n = 5) (historical overview or narrative of positive psychology, also in different domains). Fourth, backward (i.e., references of included papers) and forward (i.e., identifying studies that cited the included papers) searches were conducted to locate any additional papers that needed to be included. Nineteen additional records were identified for inclusion. Five of these 19 records were excluded for the following reasons: critique of positive psychology concepts (n = 2) and introduction to, or narrative of, positive psychology (n = 3). The authors met and discussed each manuscript in order to collate a final list of manuscripts. The final list consisted of 31 manuscripts. Fifth, the final list of included manuscripts (n = 31) was then collated and circulated to 10 prominent academics in the field of positive psychology to determine whether any important records had been missed and ought to be included. These academics each had at least 15 years of academic experience, served on the editorial boards of prominent positive psychology journals, had published at least 50 papers/chapters on positive psychology, and had a minimum h-index of 25. Eleven suggestions were received, but only one record was included. Ten manuscripts were excluded because these were not peer-reviewed (n = 4), focused on critiquing specific positive psychology concepts or theories (n = 3), focused on a general critique of psychology (n = 2), or were a direct response to previously published criticisms/critiques (n = 1). Following the entire selection protocol, a final list of 32 full texts was retained for analysis (cf., for the PRISMA flow chart).

Selection and reporting bias

Several strategies were employed to reduce selection bias in the review process. First, a clearly defined evaluation taxonomy was determined prior to conducting the research. This taxonomy was followed strictly throughout the process. Second, the initial search was done and replicated to ensure that no records had been missed (Mohamed Shaffril et al., Citation2021; Moher et al., Citation2009). Third, all records (titles, abstracts, and full texts) were screened and coded independently and in parallel by at least two researchers (Buscemi et al., Citation2006). On completion of each step of the study selection process, the researchers met to discuss and debate the inclusion/exclusion of records. The reasons for the inclusion/exclusion of a given record were recorded. Inter-rater reliability for including these records was also computed by means of Cohen’s kappa (McHugh, Citation2012). A kappa level of 0.61 or higher was considered acceptable (McHugh, Citation2012). The final list of included papers yielded a kappa of 0.71, indicating a high level of agreement among the raters. Fourth, backward and forward searches were conducted to ensure that all relevant search records were included and that none had been missed (Xiao & Watson, Citation2019). Fifth, the final list of papers was circulated to experts to ensure that no records had been missed (Mohamed Shaffril et al., Citation2021). Sixth, quality assessments were carried out on each final paper (e.g., the author’s h-index, the number of paper citations, and the impact factor of the journal; see, . Seventh, to increase credibility, trustworthiness, and transferability of the content analysis and coding process, the data were analyzed and coded by two researchers (both independently and in parallel). Disagreements in the coding were discussed until they had been resolved. Once the final analysis had taken place, a meeting was held with four researchers to discuss each code and to reflect on each agreement/disagreement. Miles and Huberman (Citation1994) indicate that the average level of agreement between raters should exceed 70%. Finally, all raw process data were retained for future scrutiny.

Table 1. Descriptive information about included records.

Data recording and analysis

Data from the final 32 records included were extracted and captured (verbatim) on a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet. Descriptive information about each record was also captured and tabulated for analysis. This included the author names, the title of the record, the journal of publication, and the findings. Data were subsequently analyzed through conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The process recommended by Saldaña (Citation2021), which is aligned with the best-practice guidelines of Miles and Huberman (Citation1994), was followed. First, all researchers read each of the final included records to get an overview of critiques/criticisms and make initial notes on possible coding. Second, two researchers independently worked through each paper and generated initial codes based on the features of the initial notes. Concept, descriptive, emotion, and values codes were inductively (i.e., data-driven) and deductively (i.e., theory-driven) created from the data. Third, codes were clustered into overarching categories (based on communalities) that consisted of several elements. In the fourth place, overarching themes (related to the criticisms and critiques of positive psychology) were constructed based on the similarity of these categories. The themes reflected the content and meaning of the data. Lastly, these themes were refined to ensure coherence between the different categories of which they consisted (Saldaña, Citation2021). All researchers participated in the refinement of the proposed themes.

Findings

This systematic review identified 32 records that met the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria (cf., ). The majority of the included records stemmed from scientific articles (68.75%) published in journals with an average impact factor of 3.39. Nine scientific book chapters and one peer-reviewed book were also included in the final selection. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology (12.5%) and The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology (15.63%) were the most frequently used outlets of these records. These 32 records garnered a total of 2 288 citations (averaging 73.81 citations per record). The majority of corresponding authors (CA) were based in WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) countries (96.88%), with an h-index ranging from 6 to 188.

Data were extracted from these 32 records and analyzed through conventional content analysis. The results showed that 117 specific criticisms/critiques could be extracted from the data. These criticisms/critiques could be grouped into 21 categories, which, in turn, could be collated into six overarching themes. These overarching themes suggested that positive psychology (a) lacked proper theorizing and conceptual thinking, (b) was problematic as far as its measurement and methodologies were concerned, (c) was seen as a pseudoscience that lacked evidence and had poor replication, (d) lacked novelty and self-isolated from mainstream psychology, (e) was a decontextualized neo-liberalist ideology that caused harm, and (f) was a capitalistic venture (cf., ). These themes are tabulated and discussed below.

Theme 1: Positive Psychology lacks proper theorizing and conceptual thinking

The first theme captures the sentiment that positive psychology lacks proper theorizing and conceptual thinking. Here, critics argue that there are fundamental problems with the philosophy underlying positive psychology and that it lacks a clear set of ideas on how positive phenomena should be conceptualized, researched, approached, and evaluated. provides a high-level summary of the nine categories informing this theme.

Table 2. Theme 1: positive psychology lacks proper theorizing and conceptual thinking.

First, the data showed that critics believed that positive psychology lacked a unifying metatheoretical perspective that underpinned the philosophy of its science. Several authors contend that positive psychology fails to provide a clear set of fundamental ideas on what constitutes a ‘positive’ psychology and how positive psychological phenomena should be thought about, researched, and approached (e.g., Cabanas, Citation2018; Brown et al., Citation2013; Robbins & Friedman, Citation2017; Sheldon, Citation2011; Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021). Positive psychology lacks a set of philosophical principles clarifying (a) the purpose of positive theories, (b) the types of theories/methods required to advance the positive psychological discipline, (c) defining criteria for theory development/evaluation, and (d) articulation of the broad paradigmatic problems facing general theory development (Robbins & Friedman, Citation2017). Critics, furthermore, argue that positive psychology has a convoluted view of human nature by adopting the ‘belief that humans are more good than bad’, which ‘could be a self-serving illusion or an ideological bias that clouds or completely blocks our view of half of human nature’ (Sheldon, Citation2011, p. 422). Finally, positive psychology lacks a holistic theory of human development (Joseph, Citation2021).

Second, several critics argue that virtues, a fundamental element underpinning the scientific philosophy of positive psychology, are poorly conceptualized. Inspired by Aristotelian virtue ethics, virtues are invoked as ‘foundational to the very meaning of the word positive [in positive psychology], yet the [positive psychological] literature has not yet sufficiently established a theoretical understanding of virtue’ (Bright et al., Citation2014, p. 457). Furthermore, Bright et al. (Citation2014) are of the opinion that positive psychology violates the tenets of the Aristotelian philosophy on which it is built. Positive psychologists ‘often operationalize virtue in ways that are problematic and perhaps inconsistent with an espoused foundation of virtue as character excellence’ (Bright et al., Citation2014, p. 449). Given its over reliance on empiricism, positive psychology has delineated virtues as merely a set of ‘preferred behaviors’ measured on a continuous scale, ‘indicating that the presence of the virtue may be low, moderate or high’ (Bright et al., Citation2014, p. 450). This has led to an action-focused view of human virtues, violating Aristotelian philosophy through the classification that ‘virtues are neutral, are neither inherently positive nor negative, but rather it is context that determines whether or not they create functional effects’ (Bright et al., Citation2014, p. 450). Virtues are, by definition, an indicator of excellence and cannot be assumed to equate to a set of preferred behaviors or being ‘neutral’. Therefore, assumptions about what constitutes virtue are not grounded in theory, but are rather shown to be prescriptive based on researchers’ sets of ideological beliefs (Banicki, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2012, Citation2013). Positive psychological researchers carelessly accept these poorly defined conceptualizations of virtues without scrutiny, which highlights a lack of self-reflection in research (Kristjánsson, Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2013). In further contrast to Aristotelian ethics, Kristjánsson (Citation2013) argues (a) that positive psychology’s prevailing theory of virtue (i.e., the Values-in-Action project [VIA]; Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004) lacks quintessential Aristotelian virtues such as self-respect, justified anger, pride, etc., as well as a moral integrator (i.e., what Aristotle referred to as ‘phronesis’); (b) that the theory also adds other ‘virtues’ that do not fit the Aristotelian virtues framework, such as transcendence, which is not tied to any specific spheres of human action/reaction; (c) that self-control or self-regulation, valorized within positive psychology, are in fact not indicators of virtue; and (d) that even though virtue and happiness are empirically linked, it is possible from a positive psychology perspective for an unvirtuous person to be a happy person. Finally, positive psychology lacks a framework for its own virtuous ethics (Kristjánsson, Citation2013).

Third, there are no clear definitions of ‘positive’ in positive psychology. The majority of the records highlighted that positive psychology had no clear or shared definition of what constituted ‘positive’ and that ‘positivity’ was defined merely by the absence of negative experiences. Kristjánsson (Citation2013) states that ‘if the idea is, as it was for Aristotle, that emotions are positive when they are good, and “good” means “morally appropriate”,’ then the claim that positive emotions are good is true, but only trivially so (‘It is appropriate to feel appropriate emotions’) – and the question remains, of course, when exactly emotions are felt appropriately. If the idea is, however, that positive emotions simply are pleasant emotions, then positive psychology seems to have collapsed into the very hedonistic theory that its leaders take such great pride in renouncing”. If there is no consensus on what exactly is meant by ‘positive’, it may result in (a) challenges in how to effectively measure positive psychological qualities, (b) differences in opinions on what may ‘count’ as positive characteristics, and (c) characterization of positive states/traits/behaviors as being context-dependent (Cabanas, Citation2018).

Fourth, there is an artificial divide between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ experiences or emotions in positive psychology. Positive psychology has created a dichotomous division between what it deems to be ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ experiences/emotions/behaviors. All emotional experiences or behaviors are, thus, classified as either positive (good/desirable) if they relate to pleasant experiences or negative (bad/undesirable) if they result in unpleasant experiences (Held, Citation2018; Pérez-Álvarez, Citation2013). This distinction between positive and negative is ‘made a priori, independent of circumstantial particularity, both intrapersonal and interpersonal’ (Held, Citation2018, p. 313). This results in a convoluted view of emotions, where positive psychology ignores conventional wisdom that ‘positive affect can be as negative as negative can be positive’ (Cabanas, Citation2018; Pérez-Álvarez, Citation2013). The function, purpose, and importance of ‘negative’ emotions are ignored outright in positive psychology (Coyne et al., Citation2010; Diener, Citation2012). Positive psychology assumes that ‘positive and negative thoughts and feelings cannot coexist, that they have symmetrical and opposite effects, and that positive thoughts and feelings are pleasant but trivial’ (Coyne et al., Citation2010, p. 37). Furthermore, this dichotomous classification fails to ‘appreciate the potential opportunities that may arise from reflecting on negative experiences and emotions, which may help avoid the trap of blind optimism or persisting with unattainable goals’ (McDonald et al., Citation2021, p. 17). Held (Citation2018) additionally argues that ‘the psychological characteristics that positive psychologists designate positive and negative do not meet their own criteria for what positivity and negativity are purported by them not only to be (constitutively) but also to do (in causally influencing adaptive and maladaptive functioning), then the very idea of a positive (or negative) psychology is bankrupt, or dubious at best’ (p. 315). Such a dichotomous classification between positive/negative is, therefore, neither useful nor functional for the process of living. Fernández-Ríos and Novo (Citation2012) support this by stating that ‘what is relevant for human beings is not for psychologists to artificially create dichotomies but for them to bring together, understand and explain people’s whole process of living. This process is a continuum that is materialized into a sociocultural context’ (p. 339).

Fifth, there are differences and inconsistencies in the construction of concepts and theories in positive psychology. For example, Banicki (Citation2014) contends that the VIA project is said to be rooted in virtue ethics stating and that the classification is built on two assumptions: ‘(1) the substantial interconnectedness of individual virtues, as expressed by the thesis of the unity of virtue, and (2) the constitutive character of the relationship between virtue and happiness. It turned out, in result, that the two above features are not only absent from but also contradicted by the VIA framework with the latter’s construal of individual virtues and character strengths as independent variables and official endorsement of the fact/value distinction’ (p. 31). There are also significant disagreements about conceptualizations of constructs such as well-being, happiness, and flourishing. These are functional concepts in positive psychology; yet no agreement exists as to how these should be defined (Held, Citation2018).

Sixth, positive psychology suffers from the ‘jingle-jangle fallacy’. The jingle fallacy occurs when different concepts such as ‘flourishing’ or ‘well-being’ are erroneously assumed to be the same because of the name they share. For example, three approaches to flourishing exist in the literature (Diener, Citation2012; Keyes, Citation2002; Seligman, Citation2011); yet the terms are used interchangeably. There are clear conceptual differences between these three approaches; yet researchers erroneously use arguments from the one to support the findings of the other. This is a result of poor or vaguely defined concepts. Furthermore, some constructs may also fall victim to the jangle fallacy, where different terms are used to describe the same construct, or old concepts are repacked to seem new or novel. For example, joy is seen as indistinguishable from other factors such as pleasure or positive affect or psychological capital, a combination of research on hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy.

Seventh, individual experiences are abstracted to organizational or societal levels and positive experiences abstracted to ‘well-being’. Limited attention is focused on clearly delineating team-, group-, organizational-, or societal-level ‘positive’ experiences. Instead, positive psychologists cascade the aggregate of collective experiences of a group of individuals to represent a team-/group-/organizational-level experience (Diener, Citation2012). For example, individual experiences of engagement are collated and used as an indicator of ‘group-level engagement’. Similarly, the level of abstraction also occurs where individual experiences of happiness are used as indicators of ‘well-being’ (Kristjánsson, Citation2012, Citation2013).

Eighth, there is fairly little theoretical grounding in the development of positive psychological interventions. Interventions do not incorporate clearly defined change models; nor are they built on validated positive psychological empirical findings or models. This leads to mixed results and small (or no) effects in intervention research.

Finally, little attention has been paid to conceptualizing positive institutions, despite these being a core aspect of the original definition of the positive psychological discipline. There has been a disproportionate focus on investigating ‘positive subjective experiences’ and ‘positive individual traits’, but limited focus on positive institutions (Diener, Citation2012). Diener (Citation2012) states that positive psychology ‘focuses too exclusively on the individual person, rather than considering the impact of neighborhoods, social groups, organizations, and governments in shaping positive behavior’ (p. 9). In line with the previous point, the discipline seems to incorporate a naive understanding of positive institutions as merely a function of individuals’ collective experiences, yet negates the importance of context or environments.

Theme 2: Issues with measurement and methodology

The second theme captures sentiments related to issues in the measurement of positive psychological constructs and the methodologies that it favors (cf., ). Here, critics argue that there are problems with how positive psychological constructs are operationalized and how these concepts are measured, that the methodologies employed are severely flawed, that there is an over reliance on empiricism and positivistic approaches, and that it fails to employ more robust research approaches (e.g., qualitative research/mixed-method designs).

Table 3. Theme 2: issues with measurement and methodology.

First, critics have posited that there are severe issues in operationalizing and measuring positive psychological constructs. They argue that the development of psychometric instruments is disorganized, leading to the development of multiple measures to measure the same psychological construct (Bright et al., Citation2014). This inevitably leads to conflicting findings between different studies (Cabanas, Citation2018; Coyne et al., Citation2010). Positive psychology also employs crude measures, which violate assumptions about psychological test construction and findings from other domains. For example, Coyne and Tennen (Citation2010) state that every post-traumatic growth scale asks participants to indicate how much change has taken place on each item of the scale as a result of the crisis they experienced. Thus, the participant should ‘(a) evaluate her/his current standing on the dimension described in the item, e.g., a sense of closeness to others; (b) recall her/his previous standing on the same dimension; (c) compare the current and previous standings; (d) assess the degree of change; and (e) determine how much of that change can be attributed to the stressful encounter’ (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010, p. 23). This is in contrast to the assumption in psychometric assessment research that ‘tells us that people cannot accurately generate or manipulate the information required to faithfully report trauma- or stress-related growth (or to report benefits) that results from threatening encounters’ (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010, p. 23). Violating these principles implies that these constructs cannot be measured accurately and that the inferences made about findings are questionable. Similarly, Christopher (Citation2014), Diener (Citation2012), and Qureshi and Evangelidou (Citation2018), and others argue that this recall bias and the overinflation of results are exacerbated by an over reliance on self-report and subjective assessment measures. A self-report measure ‘abstracts the concept in question away from real-world contexts that would ground the notion in culturally specific ways’ and provides a biased view of the self in a given moment (Christopher, Citation2014, p. 111; Qureshi & Evangelidou, Citation2018). There are, however, very few ‘objective’ measures of positive characteristics, and neurological assessments of such do not seem to corroborate mainstream positive psychological findings (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010; Coyne et al., Citation2010; Diener, Citation2012).

Critics, furthermore, are of the view that the discipline employs poorly developed psychometric instruments with questionable levels of validity and reliability. Wong and Roy (Citation2018) indicate that various popular psychometric instruments aimed at measuring positive characteristics produce different factorial structures, with widely varying levels of internal consistency, which results in poor predictive validity. This is because researchers tend to employ ‘quick and dirty’ approaches to the development and evaluation of new positive psychological assessment measures, such as only employing a single sample to validate an instrument or not including a wide range of concurrent and discriminant validity measures for validation purposes (Wong & Roy, Citation2018). Given that ‘positive’ constructs are also ‘positively’ phrased, there is a natural tendency for all factors to positively correlate with one another, resulting in high levels of multicollinearity (Thompson, Citation2018; Wong & Roy, Citation2018). Positive psychological assessment measures and techniques also show poor performance in terms of discriminant validity (Thompson, Citation2018), which highlights potential issues underlying the conceptualization and operationalization of the constructs in question. As mentioned in Theme 1, positive psychology measures individual experiences and abstracts them to team, organizational, or societal levels. There are, thus, no real measures to accurately capture true group-level experiences in positive psychology (Wong & Roy, Citation2018). Finally, positive psychological assessment measures are criticized for being culturally biased and for favoring those from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) contexts (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2012; Wong & Roy, Citation2018).Footnote2

Second, positive psychology overemphasizes the importance of empiricism and positivistic approaches. Critics argue that most empirically driven studies in positive psychology rely on positivist methodologies, emphasizing the importance of predefined, quantitative assessment measures (Bright et al., Citation2014; Wong & Roy, Citation2018). There is, thus, an overreliance on quantitative methodologies as the gold standard for scientific research. This overreliance reduces virtuous qualities to small, measurable quantities, while a reductionist way of thinking greatly simplifies complex psychological phenomena such as hedonism or eudaimonia into small measurable or atomized ‘chunks’ (Nelson & Slife, Citation2017). This atomization may be due to the difficulties in operationalizing the concepts, so that they can be studied using standardized, quantitative research approaches preferred in positive psychology (Diener, Citation2012; Nelson & Slife, Citation2017).

This reductionist reasoning and overemphasis on empiricism lead to several unintended consequences such as running ‘the risk of essentializing truths about what it means to be positive in fixed, reductive, and prescriptive ways that could occlude the complexities of life and negate the possibility of alternative ways of understanding positive behavior’ (McDonald et al., Citation2021, p. 13). Moreover, this overreliance on quantitative research and scientism indicates that positive psychology is more concerned with describing phenomena, rather than explaining them. In other words, the extent to which two factors are related is deemed more important than the underlying reason why these concepts exist or how/why they are related (McDonald et al., Citation2021). For example, Kristjánsson (Citation2010) states that positive psychological researchers see that there is no point in questioning ‘what should logically come first, the cultivation of positive personal traits or the creation of positive institutions, [it] is a chicken-or-egg question. The important thing is not to waste time wondering where to start but rather to [just] start somewhere’ (p. 299). Finally, this infallible belief in the legitimacy of statistical analysis and the scientific method withholds positive psychological researchers from critiquing or scrutinizing empirical results.

Positive psychology is also criticized for being prescriptive in ways that oversimplify or perhaps assume too much about what constitutes positive behavior (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014; Held, Citation2018; Kristjánsson, Citation2013; Pérez-Álvarez, Citation2012, Citation2013) without sufficient regard for complex contextual influences (Cabanas, Citation2018; Qureshi & Evangelidou, Citation2018; Sheldon, Citation2011). To the extent that this is true, positive psychology is ‘essentializing truths about what it means to be positive in fixed, reductive, and prescriptive ways that could occlude the complexities of organizational life and negate the possibility of alternative ways of understanding positive behavior’ (McDonald et al., Citation2021, p. 13).

Third, our findings showed that critics believed that positive psychology employed poor research designs. Critics have argued that positive psychology relies virtually exclusively on cross-sectional studies employing correlational designs with self-report measures (Cabanas, Citation2018; Diener, Citation2012; Held, Citation2018; Kristjánsson, Citation2021). These correlational findings are then too often used to infer causality, rather than just highlight mere associations between factors (Kristjánsson, Citation2010). Positive psychological researchers are, thus, ‘too cavalier about the limitations of cross-sectional interindividual research’ (Kristjánsson, Citation2010) and employ ‘dubious interpretation[s] of empirical data’ to support over exaggerated claims about the relationships between factors (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016, p. 135). Despite these criticisms and limitations of research designs, ‘positive psychology continues to be applied […], paying scant regard to these’ (McDonald et al., Citation2021, p. 3). Given that positively constructed concepts are phrased positively, there will always be correlations between factors, with little or no theoretical reasoning for these, for this reason leading to the explanation ‘of obscure facts with confusing reasoning’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012, p. 341).

Finally, critics have argued that positive psychological research fails to employ more robust research approaches. Positive psychologists have a ‘narrow understanding of science [which] comprises solely of quantitative, empirical research’ (Kristjánsson, Citation2010, p. 298). The overemphasis on empiricism and quantification in positive psychology leads to the erroneous belief that only rigorous (quantitative) methods are required to advance scientific discovery. Positive psychology, thus, negates the importance of qualitative, mixed-method, and experimental research (Banicki, Citation2014; DeRobertis & Bland, Citation2021; Kristjánsson, Citation2010). Even within its overly quantified approach, positive psychology rarely employs robust quantitative designs such as longitudinal research approaches (Held, Citation2018; Kristjánsson, Citation2010).

Theme 3: Positive Psychology is a pseudoscience: poor replication and lacking evidence

Flowing from Theme 2, the next theme captures the sentiment that positive psychology is a pseudoscience that lacks evidence and has poor replicability (cf., ). This theme highlights how important findings in positive psychology cannot be replicated and that the field lacks empirical evidence to support its claims.

Table 4. Theme 3: positive psychology is a pseudoscience: poor replication and lacking evidence.

Regarding poor replication, critics have declared that popular positive psychological models, findings, and interventions cannot be replicated (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010; N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013; Wong & Roy, Citation2018). For example, the popular gratitude visit (which has been lauded as an exemplar of positive psychological interventions) has produced mixed results in various settings and has even decreased well-being (Kristjánsson, Citation2012). Similarly, given the mathematical estimation issues in the positivity ratio framework, these results could not be replicated in other studies (N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013). The results of studies have also seemed to contradict findings in other fields such as medicine (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010; Coyne et al., Citation2010). Coyne and Tennen (Citation2010), for example, state that ‘researchers have run well ahead and even counter to what we know [in medicine], have failed to check theory against evidence, and have been seemingly oblivious to the cumulative empirical base of the broader psychological and cancer literatures’ (p. 17). Specifically, they argue that positive psychology claims that positive interventions increase life expectancy and longevity of cancer patients; however, no biological effects based on ‘positive thinking’ have ever been shown to affect survival time in cancer patients. Moreover, single-sample (positive psychological) studies on the neurological correlates of positive emotions could not be replicated or verified in more robust medical experiments (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012).

Critics have also claimed that positive psychology is a pseudoscience that lacks evidence supporting its claims. Fernández-Ríos and Vilariño (Citation2016) and others have stated that there is ‘too much unfounded speculation, interpretative alchemy and linguistic secrecy [in positive psychology]. [Positive psychology] is more like a pseudoscience or an existential philosophy of the new age than an empirically-based knowledge. An added problem to this lack of empirical rigor, is generated by the current mode of disseminating scientific knowledge’ (p. 136). Critics maintain that the empirically substantiated truths of positive psychology are trivial at best and that the effects are small (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010). Positive psychology, therefore, aims to develop a socially constructed illusion that individuals should strive to be ‘happier than the rest’ through ‘buying emotions to live with [through] new experiences of positive thinking’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012, p. 340). Yet, positive psychology makes false claims about the benefits of positive psychological interventions, theories, and models (Coyne & Tennen, Citation2010; Coyne et al., Citation2010; Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). Theories such as the critical positivity ratio and the happiness pie make claims that are unsupported by empirical evidence, which culminates in intellectual dishonesty (N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013). Over and above that, critics state that the knowledge generated in positive psychology is allegedly evidence-based, but is ‘sustained upon tautological statements, superficial knowledge and obvious conclusions’ (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016, p. 134). All knowledge produced is tautological and superficial and draws obvious conclusions about common sense or traditional wisdom (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016).

In addition, it is argued that there is a substantial amount of confirmation bias in positive psychology (Coyne et al., Citation2010; Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016; Held, Citation2018; Qureshi & Evangelidou, Citation2018). Those who support positive psychology aim to search for evidence in their results to support their own beliefs or assumptions (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). There is, thus, a projection-of-knowledge argument to be made, where positive psychological researchers ‘project an interpretation of the data [that is] favourable to their beliefs’ (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016, p. 136). Consequently, positive psychology is not self-correcting, as unexpected results are vigorously defended rather than explored and theories updated (N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013). Fernández-Ríos and Vilariño (Citation2016) state that unexpected results or paradoxical cases are always considered confirmatory or positive in positive psychology. In other words, ‘when there are no clear results from [positive psychology] investigations, they must be interpreted in its favour’ (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016, p. 136).

Given the over reliance of positive psychology on empiricism, positive psychological researchers hide unexpected results behind complex statistical analysis techniques and use these to justify the importance of their findings (N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013). Researchers engage in questionable research practices such as p-hacking, removing outliers, and the like as means of fabricating support for their hypotheses (N. J. L. Brown et al., Citation2013). Finally, critics argue that positive psychology actively engages in ‘circular reasoning (e.g., a goal of well-functioning individual must be to become goal-setting and goal-motivated), tautological (e.g., optimistic people need subjective sense of well-being to achieve optimism), drawing correlation where none are justified (e.g., success is achieved by happy people), and offering unjustified generalizations (e.g., specific positive interventions can turn any person into an optimistic, fulfilled, and successful individual)’ (Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021, p. 107).

Theme 4: Positive Psychology lacks novelty and self-isolates from mainstream psychology

The fourth theme pertains to sentiments that positive psychology lacks novelty and self-isolates from mainstream psychology. Critics contend that positive psychology brings nothing new to the proverbial table and has willfully created a divide between what it deems to be ‘negative’ psychology and the study of ‘optimal human functioning’ as a means to justify the reason for its existence (cf., ).

Table 5. Theme 4: positive psychology lacks novelty and self-isolates from mainstream psychology.

First, the critics argue that positive psychology lacks novelty and that its usefulness as a stand-alone domain is questionable. Some critics are of the opinion that the study of the ‘positive’ is a fundamental part of all psychological approaches, as the fundamental aim of psychology is to alleviate suffering and facilitate well-being (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Kristjánsson, Citation2013; Yen, Citation2010). Furthermore, the ‘positive’ aspects of human functioning such as motivation and happiness had already been studied ‘many decades ago’, and authors such as Abraham Maslow, Marie Jahoda, and Norman Bradburn had produced ‘valuable insights on what’s right about individuals’ (Diener, Citation2012, p. 10). Additionally, counseling psychology and social welfare training are deeply rooted in understanding and actualizing people’s interests and strengths and do not only focus on what is wrong (Diener, Citation2012; Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Kristjánsson, Citation2013; Yen, Citation2010). Therefore, the usefulness of positive psychology is questionable, as is the absence of the presentation of any new models, paradigms, innovative techniques, or methodologies for understanding. According to Fernández-Ríos and Novo (Citation2012), ‘nothing is innovative regarding the methodology used [in positive psychology]. Positive Psychology uses the same methodological resources employed in Psychology to conduct quantitative scientific research and the characteristic qualitative methodologies of social sciences such as narrative, ethnography or the study of everyday life … ’ (p. 336). Furthermore, positive psychology overlaps significantly with assumptions in cognitive behavioral therapy and humanistic psychology, but ‘is not an approach that is integrative or cross-theoretical [of these domains], as is often presented, but mirrors the values and practices of [these] specific orientations in psychology’ (Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021, p. 113). Therefore, positive psychology is nothing more than a fad, current trend, or modern zeitgeist rather than a means to generate significant progress in knowledge (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012).

Positive psychology researchers also exaggerate ‘the novelty of their views and findings’ to enhance the perceptive importance or impact of the discipline (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Peters & Tesar, Citation2019; Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021). Scholars in this discipline are acquiescent with regard to scientific findings, accepting these without question or without meaningful reflection. Coyne et al. (Citation2010) state that positive psychologists make over exaggerated claims about their findings and that ‘it is high time that there be wider acknowledgement of (a) the lack of evidence connecting positive psychological states to the biology of cancer, (b) acknowledgement of the consistent evidence that psychological interventions do not prolong survival, and (c) that any causal links remain to be established between the parameters of immune function studied in relation to positive psychological states and psychological interventions’ (p. 40). Positive psychology ‘as a new academic discipline, seems dispensable, and its discourse, exhausted’, and it ‘represents a confusing, uncertain and repetitive field of research-action’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012, p. 134).

In a similar vein, critics contend that positive psychology has isolated itself from other disciplines and lacks integration with mainstream psychological science. Critics argue that positive psychology purposefully positioned mainstream psychology as having a ‘negative bias’ and, thus, created a superficial positive-negative divide in the discipline (Sheldon, Citation2011). This was done in order to create its own proverbial market share in psychological science (Wong & Roy, Citation2018). It consciously distanced itself from what it deemed to be ‘negative psychology’ and refused to incorporate learning from other established fields such as medicine (Banicki, Citation2014; Coyne et al., Citation2010). Positive psychology provides shallow interpretations of reality and is unreflective regarding critiques/criticisms of it (Banicki, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2013; Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021). This, in turn, acts as a barrier to meaningful scientific discovery and exploration (Coyne et al., Citation2010). Finally, the majority of the critics also argue that positive psychology ignores the historical origins of the discipline and negates/ignores the importance of scientific discoveries in areas that preceded it. This is evident in the debates about the humanistic versus positive psychology divide (DeRobertis & Bland, Citation2021; Joseph, Citation2021).

Theme 5: Positive Psychology is a decontextualized neo-liberalist ideology that causes harm

The findings also showed that critics viewed positive psychology as a decontextualized, neo-liberalist ideology that caused harm (cf., ). Here, critics argue that positive psychology neglects the role of the context/environment in understanding positive characteristics through positioning itself as being ‘value neutral’. Furthermore, it is classified as a neo-liberalist ideology where optimal functioning and flourishing are seen as an individual enterprise and a consequence of one’s own life choices. Finally, this decontextualized neo-liberalist ideology facilitates cultural and gender biases and causes harm.

Table 6. Theme 5: positive psychology is a decontextualized neo-liberalist ideology that causes harm.

First, positive psychology is seen as a decontextualized intellectual endeavor that neglects the role and importance of context in facilitating positive states, traits, and behaviors. In contrast to how the discipline was originally conceptualized, critics contend that positive psychology is neither objective, nor universal, nor value neutral, but rather prescriptive and directive and ignores the role of context/social environments. Given the ideological importance of the self in positive psychology, critics have maintained that it is not surprising that it is a WEIRD enterprise (Banicki, Citation2014; Christopher, Citation2014; Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2010). This WEIRD enterprise positions Western or European values as being universally applicable to the entire human population, in contrast to conventional wisdom in cross-cultural psychology (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Positive psychology is positioned as an ‘indigenous psychology’ that is universally applicable and relevant; however, it neglects the importance of cultural, societal, and environmental factors required to facilitate positive experiences (Marecek & Cristopher, Citation2018; Yakushko & Blodgett, Citation2021). Meanings of positive psychological constructs (e.g., strengths/virtues) and experiences (e.g., flourishing) are, therefore, deeply rooted in Western ideologies centered on the independence of the self-concept; yet positive psychology ignores how Eastern cultures view these concepts from an interdependent perspective (Kristjánsson, Citation2013). This facilitates cultural biases in assessing and developing positive characteristics and experiences (Kristjánsson, Citation2013). Therefore, positive psychology is not only ignorant of, but also insensitive to, the perspectives of those outside of Western contexts (Christopher, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2013). Ironically, critics mention that when hypothesized findings in empirical research cannot be found, positive psychology researchers tend to blame contextual factors for this (Friedman & Brown, Citation2018).

Positive psychology also overlooks or dismisses real societal, structural, and lived realities by ignoring social and cultural factors in developing its theory (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). The overemphasis on the universality and objective nature of its findings implies that behavior is not strongly influenced by social factors such as gender, class, ethnicity, and the like. Therefore, positive psychology may be systematically biased toward some and against other genders, cultures, ethnicities, communities, and socio-economic classes (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Over and above that, positive psychology too often ignores the importance and influence of values and norms. When they are considered, values and norms are often framed in a decontextualized manner, only influencing constructs in extreme circumstances (Christopher, Citation2014; Kristjánsson, Citation2013; Thompson, Citation2018).

Second, it has been asserted that positive psychology is a neo-liberalist ideology. Burr and Dick (Citation2021) argue that positive psychology is not a science, but rather an ideology where ‘virtually every social and individual achievement or problem can be traced back to a surplus or a lack of happiness’ (p. 156). Positive psychology posits that ‘individuals are positioned as consumers or agents whose successes in life is understood to be chiefly a consequence of their life choices, which are enabled by freedom from state control and facilitated by the myriad of available “ways of being [happy]” made possible by capitalism’ (Burr & Dick, Citation2021, p. 156). In other words, positive psychology views the individual as a unique, self-contained, self-defining, and independent unit that functions separately from society and the world the individual inhabits (Banicki, Citation2014). Positive psychology, thus, assumes that people can be taught or encouraged to develop the skills needed to enable them to overcome any difficulties with which life presents them, yet overlooks the issue that the conditions of life are not ‘ontologically distinguishable from how they are apprehended or evaluated’ (Burr & Dick, Citation2021, p. 157). Accordingly, positive psychology is an enterprise of self-fulfillment, which negates the influence or importance of social or environmental factors required to facilitate positive characteristics (Kristjánsson, Citation2010). In addition, Yakushko and Blodgett (Citation2021) state that this neo-liberalist ideology may ‘shift the blame of responsibility for self-fulfilment and happiness to individuals rather than institutions or cultures that systematically marginalize and oppress’ (p. 114). Overemphasizing individualism in the pursuit of personal happiness and fulfilment negates the importance of social contexts, as a result exonerating one from social responsibility (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012).

This neo-liberalist ideology, which positive psychology facilitates, is, thus, a political tool to facilitate control, power, and influence over individuals (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). Critics postulate that it is a discipline of ‘power and politics of truth that promotes a technology that instructs people in what they have to do to be happy. In reality, they end up imposing control and enforcement procedures in order to be happy in a certain way. The society of happiness and well-being indexes aims to provide citizens with pleasant care in a cultural climate that infantilizes them, and makes them become dependent and docile. Thus, [positive psychology] becomes a political weapon of psychological and ideological control, which does not provide liberating or emancipating empirical knowledge’ (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016, p. 137).

Another element central to the neo-liberalist ideology of positive psychology is that all thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are instrumental in nature. This instrumentality consists of manipulative or instrumental efforts implemented by the individual as a means to gain control over his/her natural or social world (Banicki, Citation2014). These instrumental efforts are centered on the pursuit of external goals, which constitutes a central agency model in positive psychology. This central view of instrumentality hampers scientific progress (Banicki, Citation2014).

Finally, positive psychological models, theories, and interventions can also lead to negative consequences and cause harm. Critics argue that positive psychology pathologizes the ‘normal’ social process of living (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014; Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). Normal experiences of stress or anxiety are replaced by a ‘supposed epidemic of depression and medicalization of shyness’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012). Positive psychology sets unrealistic expectations of what ‘the good life’ entails and claims ‘that people will never be able to enjoy a minimum of happiness if they do not have the help of a positive psychology practitioner’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012). Through this, positive psychology facilitates the notion that ‘all human beings can and must function above their possibilities’ to ‘achieve a happiness that human beings will never be sure to reach’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012). Consequently, there is an overemphasis on irrational optimism and the creation of unrealistic expectations in people (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012). The result is an irrational obsession with the illusion of happiness, which may cause significant harm in the long term through unsuccessful pursuits to lead one’s best possible life (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012; Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016; Thompson, Citation2018). This, in turn, subjects ordinary people to therapeutic interventions ‘for the sake of increasing a false longing of illusory happiness’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012). Positive psychology, therefore, facilitates the medicalization of positive experiences, which can lead to ‘the use of drugs and an unlimited search for new stimuli that will supposedly create positive affects’ (Fernández-Ríos & Novo, Citation2012).

Similarly, positive psychology classifies or ‘diagnoses’ mental health (and related concepts) in the same way that the disease model does with mental illnesses. Any diagnostic system inadvertently creates a distinction between groups of people (Thompson, Citation2018). Although the classification of psychological states, traits, and behaviors is normal and neutral, the labels for the categories of classification are not. These classification categories are socially constructed and hold social meanings, which have tangible consequences for people (Thompson, Citation2018). A diagnosis of positive states/traits/behaviors carries a powerful social signal that affects how people are thought about by others and how they think about themselves and highlights the resources they can or cannot access. It may be counter-intuitive to think that having a classification of ‘flourishing’ or ‘mentally healthy’ can have negative effects, but this classification labels people as ‘optimal’ or ‘ideal’, which, by implication, labels others who do not share the classification as ‘dysfunctional’. Thompson (Citation2018) states that ‘if we think about diagnostic labels – whether of illness or flourishing – as warranting certain forms of action, then we can see a clear commonality between the two cases. In both, there is a category of people who can be construed as “having something wrong with them,” and therefore for whom some form of intervention or treatment might be seen as appropriate’ (p. 75). The risk of describing positive mental health in categorical, diagnostic terms ‘has essentially the same effect as describing distress as illness. That is, it situates the “problem” within the individual, and therefore encourages explanations that downplay, or even ignore, the role of wider social and systemic factors’ (Thompson, Citation2018, p. 80). As such, a positive diagnosis may also lead to experiences of stigma (Thompson, Citation2018).

Positive psychology is not only culturally biased and insensitive to gender differences; it also facilitates and reinforces gender/cultural stereotypes. For example, Englar-Carlson and Smart (Citation2014) argue that ‘focusing on “positive” gendered traits (either “feminine” or “masculine”) […] essentializes those traits as belonging exclusively to a gender and reinforces stereotypes’. Positive psychology promotes essentialism through overemphasizing gender-specific traits (e.g., ‘positive masculinity’), thus limiting the deconstruction of gender roles, and hampers social change (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Critics, furthermore, contend that ‘it is erroneous to assume that there is only one perspective of a “positive trait” for different genders, as different cultures have varying ideas of what is “positive” for each respective gender’ (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Positive characteristics and experiences cannot be seen as universally positive. A magnitude of sociocultural factors may influence how these are perceived, performed, and experienced (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Yakushko and Blodgett (Citation2021) note that ‘positive psychology frequently denies or minimizes the role of social oppression or social violence while shaming individuals who are targeted by these forms of marginalization for not having internal attributions, self-control, and optimistic worldviews’.

Englar-Carlson and Smart (Citation2014) also argue that positive psychology pays little explicit attention to women’s gender in sociocultural or sociopolitical contexts. Although there are several studies focusing on, for example, the strengths of woman clients within specific interventions, there are no real references to gender in these studies and ‘no explicit examination of their sociocultural and sociopolitical contexts’ (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014). Therefore, positive psychology cannot make convincing arguments or present ‘accurate representations of the experience of women and ethnic minorities’ (Christopher, Citation2014). Thus, positive psychology perpetuates a one-sided view of positive states/traits/behaviors, which is ‘not only culturally specific but fails to account for the kinds of transformation and development that in many traditions defines the essence of the positive’. For this reason, positive psychology alienates and oppresses marginalized groups such as transgenders (Englar-Carlson & Smart, Citation2014) and ignores power imbalances within and between these groups as a means of maintaining the status quo (Qureshi & Evangelidou, Citation2018). As a result, positive psychology ignores implicit and explicit power imbalances between different cohorts of people and disregards aspects such as racism.

In a more practical sense, Wong and Roy (Citation2018) also highlight that positive psychological interventions do not yield universally beneficial or unconditionally positive results and that these can also cause harm. When developing and implementing positive psychological interventions, researchers/practitioners fail to anticipate or control for the potential negative consequences of these interventions. For example, gratitude interventions can lead to an increased experience of unhappiness and psychological distress characterized by increasing feelings of guilt, obligation, embarrassment, and indebtedness (Wong & Roy, Citation2018). Furthermore, ignoring or playing down negative experiences in therapy or psychological interventions is not only futile, but also potentially oppressive and destructive (Wong & Roy, Citation2018).

Theme 6: Positive Psychology is a capitalistic venture

The last theme created from the data was that positive psychology was a capitalistic venture, driving profits and capitalizing on impossible dreams (c.f. ). Critics argue that positive psychology is a capitalistic tool to promote positivity and further facilitate individualism, consumerism, and the commercialization of positive experiences (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). The discourse of positive psychology highlights the need for people to be ‘happy’ and maintains that ‘happiness’ is required for one to not fall into misfortune (Fernández-Ríos & Vilariño, Citation2016). Positive psychology has, thus, created a marketplace for happiness through capitalizing on the impossible dream to be 100%, 100% of the time. Therefore, positive psychology has successfully facilitated the medicalization of positive experiences and created a market for psychological assessment firms, consultants, self-help books, etc. to facilitate ‘happiness’ at a significant financial cost (Thompson, Citation2018).

Table 7. Theme 6: positive psychology is a capitalistic venture.

Discussion and future directions

This systematic literature review aimed to explore the contemporary critiques and criticisms posed of the discipline and to provide a consolidated view of the main challenges facing the third wave of positive psychology. The review identified 32 records that posed 117 unique criticisms and critiques of various areas of the discipline. These could be grouped into 21 categories through conventional content analysis, culminating in six overarching themes or ‘broad criticisms/critiques’. The findings discussed in the previous section suggested that positive psychology (a) lacked proper theorizing and conceptual thinking, (b) was problematic as far as measurement and methodologies were concerned, (c) was seen as a pseudoscience that lacked evidence and had poor replication, (d) lacked novelty and self-isolated from mainstream psychology, (e) was a decontextualized neo-liberalist ideology that caused harm, and (f) was a capitalistic venture (cf., ). We briefly reflect on the findings and highlight future directions in the discussion below.

Getting to the root(s) of the problem: improper theorizing and poor measurement/methods

Although the relative importance of the six broad criticisms/critiques was difficult to determine, each of the 32 records highlighted problems relating to improper theorizing and conceptual thinking within positive psychology and issues with its measurement and (research) methodologies. It can be argued that these two issues are the proverbial root cause of problems in positive psychology.

Our first finding showed that most critics believed that positive psychology lacked proper theorizing and conceptual thinking. According to them, positive psychology lacked a unified metatheory that grounded the philosophy underpinning the science and failed to provide a clear set of ideas or criteria regarding how positive psychological phenomena had to be conceptualized, examined, and approached. These criticisms and the limitations to theory development are neither new nor neglected by positive psychologists (Van Zyl & Rothmann, Citation2022; Wissing, Citation2021). Positive psychological scientists have had widespread debates on the epistemological, ontological, and axiological beliefs driving the discipline (cf., Diener, Citation2012; Lomas & Ivtzan, Citation2016; M. Seligman, Citation2018; Waterman, Citation2013; Wissing, Citation2021). These philosophical debates have aimed to create widespread consensus on the world views of positive psychology to determine the most appropriate methods, terminologies, and types of theories required to move the discipline forward (cf., Wissing, Citation2021). Over time, these philosophical debates about the view of positive psychology of human nature and the real world (ontology), beliefs regarding how knowledge is generated/validated (epistemology), and views of what it values or what is considered desirable/undesirable (axiology) have become more ‘tangible’ (Wissing, Citation2021). Recently, Ciarrochi et al. (Citation2022), Wissing (Citation2021), Lomas et al. (Citation2021), and M. Seligman (Citation2018), and others started to clarify the philosophical position of positive psychology, presented clearer guidelines for theory development, highlighted the methods/approaches required to advance the field, and set guidelines on how to address paradigmatic issues.

For example, Seligman’s (Citation2011, p. 13) PERMA framework of well-being (Positive emotions, Engagement, positive Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments) received widespread criticism from scholars. Critics argued that PERMA was not a theory of well-being, but rather just a listing of factors that had been shown to be related to well-being (Wong & Roy, Citation2018), that there was no theoretical justification for why these factors related/had to be included (Donaldson et al., Citation2022), that PERMA did not attribute any unique variance in general well-being frameworks, and that it was redundant (Goodman et al., Citation2018). In response, M. Seligman (Citation2018) contended that PERMA was not a framework of what well-being was, but rather a set of elements required to facilitate well-being. He, furthermore, indicated that PERMA was not an exhaustive framework and that it could be expanded. In line with the propositions of Kuhn (Citation1970) and Wallis (2000) on theory development, M. Seligman (Citation2018) proposed six criteria required for expanding the PERMA framework: (a) new elements had to directly relate to well-being, (b) an element had to be pursued in its own right and not as a means to pursue another, (c) new elements had to lead to developmental interventions, (d) all factors had to be parsimonious, (e) PERMA had to be open and flexible to new developments, and (f) each new element had to be independently defined and measured. M. Seligman’s (Citation2018) response and criteria, thus, provided a basis for scientific advancement, as they ‘addressed a number of the criteria underpinning the creation of robust theories: clarifying the purpose of the theory (through highlighting that it’s an approach to rather than of well-being), highlighting what additional types of approaches/elements are needed for its expansion, setting specific criteria for theory development and evaluation and inviting further theorizing’ (Donaldson et al., Citation2022, p. 5).

Similarly, Lomas et al. (Citation2021) presented more explicit criteria for the types of theories, methods, and approaches needed to facilitate scientific advancement in the third wave of positive psychology. They argued that positive psychology had to broaden its scope by developing more contextually relevant theories and employing more systems-informed and cultural/linguistic approaches to theory development (and creating ethical guidelines) and had to expand its methods by employing more qualitative/mixed-method methodologies, using implicit assessment tools, and using more advanced computational approaches to analyze data. Expanding on this narrative, Wissing (Citation2021) postulated the types of holistic perspectives that were required in positive psychology and how contextually specific approaches to positive phenomena had to be approached, as well as highlighting the value of interdisciplinary work. She also highlighted the importance of embedding the theories and methods of positive psychology within its meta-assumptions. Wissing (Citation2021), additionally, laid the foundation for creating more clarity in the world views of positive psychology (ontology, epistemology, and axiology), proposed criteria for expanding its empirical context, identified the types of measurements required, and highlighted the importance of investing in emerging focus domains. Similarly, Pawelski (Citation2016) attempted to provide a descriptive overview of what constituted ‘positive’ in positive psychology and highlighted the six discrete meanings underpinning this from prior research.

Taken together, it was clear that positive psychology researchers had taken heed of prior critiques and had made active attempts to clarify the metatheoretical assumptions of positive psychology. Despite the progress, there are still a number of matters requiring clarity. Positive psychology should attempt to clarify its metaphysical perspective of reality, present a consolidated view of ontological/epistemological/axiological beliefs, clarify and create consensus as to what is considered ‘positive’, address consistencies in and between theories, and develop its own theory of human development. Furthermore, the field should move beyond the positivist paradigm and the accompanying reductionist way of thinking. There is value in adopting either a postpositivist or constructive-interpretivist perspective when exploring/explaining positive psychological phenomena (Wong, Citation2011). Multiple realities exist, and researchers/practitioners cannot be entirely objective or void of bias. Therefore, acknowledging this limitation and appreciating the presence of multiple perspectives and how one’s own biases affect the interpretation of the world may lead to more robust theories and methods (Friedman & Brown, Citation2018). Moreover, specific attention needs to be given to creating ethical decision-making models that inform and evaluate judgements about the values and future priorities of the discipline (Friedman & Brown, Citation2018). Positive psychology should also refrain from reporting and exaggerating sensationalist claims and should acknowledge limitations of important findings (especially when communicated in the public domain).