?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Gratitude and indebtedness facilitate cooperative relationships and prosocial behavior. Yet, studies are needed to assess whether indebtedness and gratitude have differential prosocial effects. Study 1 (N = 659; highly religious emerging adult sample) employed a 3 × 2 experimental design with six conditions; 1) gratitude-only to humans, 2) indebtedness-only to humans, 3) gratitude and indebtedness to humans, 4) gratitude-only to God, 5) indebtedness-only to God, and 6) gratitude and indebtedness to God. Study 2 (N = 1,081; nationally representative sample) was a replication of Study 1. People prompted to experience both gratitude and indebtedness had higher prosocial relational engagement (i.e. consistent effects for relationship proximity and direct reciprocity) than those who primarily experienced gratitude or indebtedness. Transcendent indebtedness (want to repay) was related to better prosocial outcomes than transactional indebtedness (have to repay). Secure attachment to God moderated the association between receiving a favor from God (versus human) and increased prosocial behavior.

Gratitude is a complex biopsychosocial and cultural mechanism that has many downstream effects, including the formation of moral virtues (Emmons, Citation2016), enhanced emotional well-being (Y. J. Wong et al., Citation2018), and improving the quality of relationships through reciprocal giving (Braun et al., Citation2018). Gratitude is theorized to bind people together through responsive giving (Algoe, Citation2012). Indeed, social scientists have observed that gratitude mediates the association between receiving help and prosocial behaviors (Bartlett & DeSteno, Citation2006), and a recent meta-analysis found a moderate link (r = .37) between gratitude and prosocial behavior (Ma et al., Citation2017). However, most research on gratitude does not distinguish between gratitude and a sense of indebtedness, reducing measurement accuracy (P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). Research has found this conflation is a conceptual and methodological error (Nelson et al., Citation2022; P. Watkins et al., Citation2006; Peng et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Gratitude and indebtedness work in tandem, but they likely have unique roles in relationship building and social exchange (Nelson et al., Citation2022; Oishi et al., Citation2019; P. Watkins et al., Citation2006).

Specifically, there is emerging evidence that gratitude promotes proximity seeking, which builds relationships (Algoe et al., Citation2008; Peng et al., Citation2018), and indebtedness promotes equity-seeking, which binds relationships (Peng et al., Citation2018). In other words, gratitude and indebtedness may work together to build and bind relationships. Gratitude and indebtedness are theorized to motivate prosocial behavior through reciprocity, which is the underpinning of cooperative relationships (Lawler & Thye, Citation2009). Reciprocity is present in even small children (Beeler Duden & Vaish, Citation2020; Vaish and Hepach, Citation2020), suggesting that reciprocity is part of an evolved cognitive system that promotes cooperative relationships and human thriving (Forster et al., Citation2017). For example, the ancient practice of gift-giving taps into the norm of reciprocity to promote goodwill and bind people together through reciprocal obligation (Mauss, Citation1966). Despite the importance of gratitude and indebtedness in developing prosociality, there has been a negative bias towards indebtedness in the scientific literature (Greenberg & Shapiro, Citation1971; Nelson et al., Citation2022; P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). Consequently, the positive contribution of indebtedness towards prosociality has not received adequate empirical attention.

Moreover, initial theory and research suggest that the interactive effects of gratitude and indebtedness may vary based on four factors: (1) the types of benefactors involved in receiving a gift, (2) the characteristics of the individual, (3) the quality of the relationship between benefactor and beneficiary, and (4) the nature of the gift (J. Tsang et al., Citation2021; Nelson et al., Citation2022). Until recently, all research on indebtedness focused on interpersonal human relationships. However, in addition to receiving benefits from distinctive human benefactors, many people attribute benefits in their lives to God. Initial research suggests gratitude and indebtedness to God may differ from gratitude and indebtedness experienced toward humans (Nelson et al., Citation2022; Nelson et al., Citation2023). However, no experimental studies have attempted to examine and isolate the differential effects of gratitude and indebtedness towards God versus humans in predicting prosocial behaviors.

Thus, we build on the conceptualization of gratitude and indebtedness as distinct responses to receiving benefits with different action readiness tendencies. We also recognize that they may be experienced differently when engaged toward God versus human benefactors. Therefore, the present work aims to experimentally test how gratitude and indebtedness toward God or humans are associated with prosociality and relationship building.

Feeling gratitude and expressing gratitude

To explain the association between gratitude and prosocial behavior, scholars have conceptualized gratitude as a moral emotion (e.g. Haidt, Citation2003; McCullough et al., Citation2001). Moral emotions link values to behavior (Tangney et al., Citation2007). Recent neuroimaging supports this view with evidence that gratitude is an emotion experienced in the reward system of the brain that makes the beneficiary feel closer to the benefactor (Yu et al., Citation2017). Because scientists have not sufficiently separated gratitude and indebtedness in examining social exchanges, researchers have aggregated the effects of the two under the umbrella of gratitude. However, a sense of indebtedness may be the actual underlying mechanism in social exchange that fosters reciprocal action (Peng et al., Citation2018). Indeed, some social scientists even posit that gratitude is not a virtue (i.e. a value in action) without a sense of indebtedness because, without indebtedness, gratitude is insufficient to promote reciprocity (J. Tudge & Freitas, Citation2018). In this view, gratitude without indebtedness is just appreciation (J. R. H. Tudge et al., Citation2015; Roberts & Telech, Citation2019), leaving only a shell of gratitude for self-presentation (Baumeister & Ilko, Citation1995). This type of gratitude is shallow because it is divorced from duty, obligation, and indebtedness (Emmons, Citation2016).

Therefore, gratitude without indebtedness might be more of what Batson (Citation2015) calls an end-state emotion – like happiness – that does not produce moral behavior in of itself. It is the combination of gratitude and indebtedness that constitutes moral gratitude, which motivates prosocial behavior and relational bonding (Roberts & Telech, Citation2019). In this theory, indebtedness bridges the gap between feeling gratitude and expressing gratitude. Gratitude is the reward or the signal to the brain after receiving an intentional benefit – making the receiver feel closer to the giver. Subsequently, the evaluation and awareness of the gift as valuable initiates a sense of indebtedness, activating the norm of reciprocity and motivating prosocial behavior.

Varieties of responses to indebtedness

Indebtedness can be conceptualized as a discrete emotion. Like other emotions (Frijda, Citation2009), it not only activates a particular feeling state but also produces specific cognitive appraisals (e.g. appraisal that the organism owes something to others) and prepares the organism for action (e.g. action readiness for engaging in a prosocial manner). More specifically, indebtedness functions as what Batson calls a need-state emotion (Batson, Citation2015). Such emotions – like fear or guilt – are particularly suited to propel recipients into action (Batson, Citation2015). In other words, indebtedness acts as a tension-state, collecting potential energy for reciprocity; conversely, gratitude functions as an end-state emotion (Batson, Citation2015) that reinforces relationships through the neurological reward systems (Yu et al., Citation2017).

Like gratitude, whether indebtedness is activated depends on the appraisals associated with the characteristics of the benefactor, the nature of the benefit, beneficiary characteristics, and the relationship structure and quality between the beneficiary and benefactor (J. Tsang et al., Citation2021; Nelson et al., Citation2022). Likewise, these factors, alongside cultural and individual differences, influence the valence of indebtedness – whether it is experienced as a positive or negative state (Buchtel et al., Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2022). Indebtedness is similar to accountability, which can be positively or negatively valenced depending on the circumstances (Bradshaw et al., Citation2022; Evans, Citation2021; Torrance, Citation2021). Indeed, gratitude itself is not universally experienced positively; it tends to be negatively valenced for people with an autonomous interpersonal style (Parker et al., Citation2017). Even when indebtedness has a negative emotional valence, the human response to indebtedness is an evolved complex social motivator that drives reciprocity, generosity, and upstream altruism (Beeler Duden & Vaish, Citation2020; Gouldner, Citation1960; Peng et al., Citation2018). Given the lack of empirical understanding of the positive varieties of indebtedness alongside its social function, it deserves more empirical exploration.

Prior research has identified two different types of social indebtedness engaged between individuals: (1) transactional indebtedness, a ‘pay it off’ orientation, which often involves negative affect and low gratitude, and (2) transcendent indebtedness, a ‘pay it back’ and ‘pay it forward’ orientation, which involves positive affect and high gratitude (Nelson et al., Citation2022, p. 4). The negative affective pattern of transactional indebtedness is the type of interpersonal indebtedness most frequently discussed in the scientific literature (Algoe et al., Citation2008; Greenberg & Shapiro, Citation1971; P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). Initial work on interpersonal indebtedness focused solely on aversive responses to indebtedness because it was considered mutually exclusive from gratitude (Greenberg & Shapiro, Citation1971). This dichotomy has proven to be a conceptual and methodological misstep because indebtedness and gratitude can, and frequently do, co-occur (Layous et al., Citation2017), suggesting that gratitude and indebtedness are not mutually exclusive but may even be mutally enforcing.

Despite the enduring negative view of indebtedness in the literature, a more favorable view has emerged in recent years. A factor analysis of different responses to receiving benefits revealed that while owing and feeling beholden were components of indebtedness, feeling like a burden, regret, and uneasiness were associated with a different factor, which the researchers titled ‘regret for bothering’ (Naito & Sakata, Citation2010, p. 185). The discomfort associated with receiving is a separate phenomenon from indebtedness. Indeed, indebtedness is intentionally cultivated in some contexts. For example, Naikan Japanese therapy involves bringing clients to an awareness of their indebtedness by having them recall the benevolence they have received. This indebtedness practice reveals the interdependent nature of human existence (Naito & Sakata, Citation2010) and is effective for improving relationships, cultivating gratitude, and realizing social responsibilities (Fujisaki, Citation2020).

Gratitude and indebtedness to god

Research on interpersonal gratitude and indebtedness has created a framework for understanding how gratitude and indebtedness build and bind relationships, but many questions remain unanswered. Receiving a benefit can evoke many different responses, including (1) positive affect (warmth, joy, happiness, gratitude), (2) negative affect (unpleasantness, depression, annoyed, troubled), (3) burdensomeness (regret for bothering and causing a problem, uneasiness, feeling sorry), and (4) indebtedness (owing to the benefactor and feeling beholden; Naito & Sakata, Citation2010). What influences people to experience these contrasting responses to gift-giving scenarios? Moreover, in the case of indebtedness responses, what influences people to engage in a transactional versus transcendent orientation to indebtedness? As previously discussed, the characteristics of the benefactor and the relationship between the beneficiary and benefactor affect the response a person will have to receiving a gift (alongside the nature of the benefit and characteristics of the beneficiary; J. Tsang et al., Citation2021; Nelson et al., Citation2022). In particular, the human versus supernatural nature of the benefactor is a factor that may greatly affect whether a transactional or transcendent indebtedness is engaged.

In social exchange, individuals interact with countless benefactors across the lifespan in ways that can be positive, problematic, or indifferent. In a theistic exchange, religious individuals in the United States often portray God as a Benevolent Giver, and spiritual gifts from a monotheistic God include opportunities, privileges, atonement, and even life itself. Direct reciprocity (pay it back) is common in interpersonal social exchange, but direct reciprocity to God may be more difficult. For this reason, diffuse reciprocity (pay it forward) may be a more likely form of reciprocity when returning thanks to God. This may be especially true in Western monotheistic religions, where direct reciprocity practices are uncommon.Footnote1 Therefore, gratitude and indebtedness to God may have different prosocial consequences than interpersonal gratitude and indebtedness (to humans).

However, numerous research studies show that the psychological effects of activating God concepts depend on the security of the attachment people have with God. Like attachments to human caregivers, people have internal working models representing God as more or less responsive and available, indicating attachment security or insecurity (Beck & McDonald, Citation2004). People who are securely attached to God may be more likely to experience God as willing to give benefits even if those benefits cannot be repaid. In contrast, people with a more insecure attachment are more likely to view indebtedness in a more transactional manner because their insecure internal working model indicates that God cannot be counted on as a reliable benefactor, so they should avoid any dependence on God (i.e. avoidant dimension) or will need to engage in bids for acceptance and other behaviors to earn acceptance/attention (i.e. anxious dimension). Thus, we anticipate the positive effects of having God as a target of gratitude and indebtedness may only emerge for people with higher levels of secure attachment to God.

We designed two experimental studies to further investigate the role of indebtedness in predicting prosocial behaviors. We tested the first two hypotheses in Study 1. Study 2 was designed to replicate the findings from Study 1 and test two additional exploratory hypotheses (H3 and H4).

H1: Gratitude and Indebtedness Synergism.

First, people who experience a combination of gratitude to God (or humans) and indebtedness to God (or humans) will be higher on direct reciprocal prosocial behavior and proximity seeking than those who only experience one or the other of gratitude or indebtedness. In other words, the two in combination will have a more substantial impact on outcomes than each will separately.

H2: Diffuse Reciprocity.

Second, drawing on the lower accessibility of direct reciprocity to God, we hypothesized people who experience indebtedness (both types) to God would be more likely to engage in diffuse reciprocity than those who experience indebtedness (both types) to humans.

Exploratory H3: Indebtedness will predict high-cost versus low-cost diffuse reciprocity. We tested an additional exploratory hypothesis in Study 2 that people who experience high levels of indebtedness will be more likely to perform a high-cost helping behavior than a low-cost helping behavior as forms of diffuse reciprocity.

Exploratory H4: Secure attachment to God.

Finally, we hypothesized that secure attachment to God would moderate the conditional effects of receiving a gift from God when predicting prosocial outcomes (i.e. relationship proximity, direct and diffuse reciprocity).

Study 1

Study 1 methods

Participants

The sample for Study 1 consisted of psychology students attending a private religious university in the U.S. Power analysis for a six-group ANOVA based on a conservative estimate of effect size (d = .20; Buchtel et al., Citation2018; Peng et al., Citation2018) and 80% power, with significance criteria of p < . 05, suggested a total N = 501 (calculated using G*Power 3.1 software). Nevertheless, we aimed for at least 600 participants to hit our target sample size. Data collection took place spring and fall of 2021 and ceased once we reached 600 participants and the fall semester ended. The final sample size was N = 659, with around 108 participants in each condition (M age = 21, 61% female, 91% White, 1% Black, 2% Native American, 4% Asian, 1% Native American Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 5% Other [numbers do not add up to 100% because participants were allowed to check more than one option]). Participants were highly religious (99% were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; 94% attended church weekly or more; 82% reported having a life committed to God; 72% participated in private religious practices daily or more). Twelve participants who did not identify as religious were excluded from the experiment due to the aims of the study to understand religious phenomena. Four participants under the age of 18 and 30 participants who completed less than 10% of the survey or spent less than a minute on the survey were not included in the analytic dataset.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Brigham Young University granted approval for the study (IRB# X2020–491). Participant consent was obtained before beginning the survey. First, trait measures were administered in random order (with items in random order). Then, participants read four vignettes from their assigned condition. After each vignette, the state measures were administered to all the conditions. Finally, a measure of prosocial behavior was administered at the end of the study. Study materials and pre-registrationFootnote2 are available at: https://osf.io/bygrp.

Manipulations

To test our hypotheses, we created a 3 × 2 experimental design with conditions designed to (1) evoke gratitude only, indebtedness only, or both gratitude and indebtedness (2) to God or to humans. In alignment with theory, we hypothesized that conditions 3 and 6 (both high gratitude and indebtedness to humans or God) would evoke transcendent indebtedness and that conditions 2 and 5 (high indebtedness only to humans or God) would evoke high levels of transactional indebtedness. To create these conditions, we created four different vignettes and then altered them slightly using the four factors framework that predict indebtedness and gratitude responses to receiving (Nelson et al., Citation2022). Participants were randomly assigned to one of six conditions. Participants in all experimental conditions read the set of four vignettes, which asked them to imagine instances of receiving gifts that were the same across conditions but modified slightly to evoke different responses (e.g. you receive help finding employment, get needed medical procedure, receive a Christmas present, life saved in a car crash). The vignettes were presented in random order, and participants were asked to ‘please put yourself in the situation and imagine how you would respond’. In three of the conditions, God was presented as the benefactor, and in the other three, a human benefactor was presented. The content of the vignettes was manipulated to activate a particular response to the benefit (gratitude only vs. indebtedness only vs. both gratitude and indebtedness). The vignettes for all conditions can be found in the online supplemental materials.

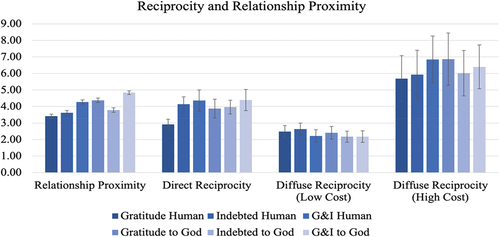

Figure 1. Means across conditions of prosocial behavior.

Gratitude levels were manipulated by slight alterations in the stories concerning variables associated with gratitude. For example, benevolent helper intention was modified to increase gratitude without affecting indebtedness (i.e. assigning a benevolent intention to the benefactor; J. -A. Tsang, Citation2006), and the expectation of reciprocity was manipulated to decrease gratitude (P. Watkins et al., Citation2006; Washizu & Naito, Citation2015). Indebtedness was manipulated similarly to gratitude but by including slight changes in variables associated with indebtedness. For example, indebtedness was induced by increasing the cost of the benefit received in the story (Greenberg et al., Citation1971) and adding benefactor expectations of reciprocity (P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). Variables associated with both gratitude and indebtedness were manipulated in the vignettes in conditions intended to activate both responses. For example, gratitude and indebtedness were manipulated by modifying the relationship quality between the benefactor and the beneficiary (Oishi et al., Citation2019) and modifying the valuation of the gift (Peng et al., Citation2018; Shiraki & Igarashi, Citation2016).

The manipulations were tested in a pilot study prior to launching Study 1 and 2. A MANOVA with conditions as the independent variable and (1) state gratitude, (2) obligated (have to repay) indebtedness, and (3) agentic (want to repay) indebtedness as the dependent variables revealed significant differences across conditions. The vignettes were found to be highly effective manipulations of gratitude and indebtedness with distinctions in state levels of gratitude and indebtedness across the conditions (η2 = 0.16, F(15, 849) = 10.45 p < .001). Gratitude was significantly different across conditions (η2 = 0.18, F(5, 283) = 12.25 p < .001), as was indebtedness (η2 = 0.24, F(5, 283) = 17.72 p < .001). In particular, post-hoc tests showed state gratitude was higher in conditions intended to evoke it, and state indebtedness was higher in conditions intended to evoke it. For more details about the pilot study and the results across the conditions, please refer to online supplemental materials.

Trait measures

Gratitude to god

The Gratitude to God Scale ( .93, 10 items, e.g. ‘Life is a wonderful gift from God’.; Watkins et al., Citation2018) was used to measure gratitude towards God. Responses were given on a scale of 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly agree’.

Transcendent indebtedness to god

The T-ITG scale ( .92, six items, e.g. ‘I owe God for my life’; Nelson et al., Citation2022) was used to measure transcendent indebtedness to God. Participants rated responses from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly agree’.

Secure attachment to god

The Attachment to God Inventory measured secure attachment to God ( .91, three items that measure secure attachment on the nine-item scale, e.g. ‘I have a warm relationship with God’; Beck & McDonald, Citation2004). Responses ranged from 1 ‘Strongly agree’ to 7 ‘Strongly disagree’.

Trait gratitude

Dimensions of dispositional gratitude ( .88, 16 items, e.g. ‘Life has been good to me’; P. C. Watkins et al., Citation2003) were measured with the GRAT-short scale. Items were rated from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘Strongly agree’.

State measures

Direct reciprocity

After the participants read each vignette, they were asked how likely they would be to repay their benefactor. Responses were rated on a scale from 1 ‘Not at all’ to 5 ‘Very Much’. Mean composite scores across the vignettes were created ( .85).

Relationship proximity

After the participants read each vignette, they were asked how much closer they felt to their benefactor. Responses were rated on a scale from 1 ‘Not at all’ to 5 ‘Very Much’. Mean composite scores across the vignettes were created ( .83).

Responses to receiving

Participants’ responses to receiving a benefit were measured with an extended version of Watkins’ affect scale (P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). After reading each vignette, participants were asked, ‘of the responses listed below, which did you experience while imaging the story? Please indicate the intensity of your response’, from 1 ‘Not at all’ to 5 ‘Very Much’. The following responses were listed: grateful, indebted (obligated to repay), indebted (desire to repay), resentful, glad, proud, guilty, irritated/annoyed, love, apathy (this item was an attention check), entitled, humbled, fortunate, and surprised. Composite scores of the response items across the four vignettes were created.

State gratitude and indebtedness

Gratitude and indebtedness responses were created from the emotional responses to receiving items listed previously. To measure the different types of indebtedness, participants were given two choices: ‘indebted: obligated to repay’ to measure obligated or transactional indebtedness and ‘indebted: desire to repay’ to measure agentic or transcendent indebtedness. Composite scores across the four vignettes were created by averaging scores for gratitude (.78), and the two indebtedness items collapse into an overall indebtedness score (

.84) as well as separate transactional (

.80) and transcendent (

.73) indebtedness.

Diffuse reciprocity: letter writing

Volunteering time to encourage strangers in need is a prosocial behavior that may reflect diffuse reciprocity (paying it forward). Diffuse reciprocity was measured with an opportunity for participants to write pediatric hospital patients small notes of encouragement. Participants were given five blank text boxes where they could write 0–5 letters. We created two continuous variables from the letter data (number of letters written and number of words used across letters). We also created a dichotomous variable (did they write a letter at all: yes/no). Word count was used in all analyses because the other variables did not have sufficient variability.

Analytic strategy

All analyses were performed using Stata SE 16 and SPSS statistical software. The analytic code that was used is available to view at the OSF. After running frequencies and tests of normality, we discovered some outliers in the word length variable of prosocial behavior. The variable was Winzorized (fenced to the 95% interquartile range) to deal with the extreme outliers. The hypotheses were tested first with MANOVA to test for conditional effects and then with regression to examine state-level variables. These secondary state-level analyses allowed us to accommodate for individual differences in gratitude and indebtedness responses to the manipulation, which prior research has found to significantly alter results (Naito & Sakata, Citation2010; Oishi et al., Citation2019; Peng et al., Citation2019). We repeated this method for nearly all the hypotheses to ensure that we tested for both conditional and individual differences.

Study 1 results

Results of the 3 × 2 factorial MANOVA predicting study outcomes are presented in . Means and descriptive statistics are provided in . Correlations between variables are provided in the online supplemental materials.

Table 1. 3×2 factorial results: study 1 and 2.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals for variables across conditions in Study 1.

Conditional effects

Manipulation check

Results of the MANOVA indicated significant effects of the induction factor (Gratitude Only vs. Indebtedness Only vs. Gratitude & Indebtedness) on state gratitude and state indebtedness (both transactional and transcendent). Post hoc contrasts revealed that participations induced to feel grateful had higher state gratitude than those induced to feel indebted, and participants induced to feel indebtedness had higher scores on both types of indebtedness than those induced to feel grateful. Further, those in the gratitude and indebtedness conditions experienced the highest levels of both gratitude and indebtedness. Additionally, participants induced to feel both gratitude and indebtedness had lower levels of transactional (have to repay) indebtedness compared to participants who received a gratitude or indebtedness manipulation in isolation. These results show that the induction factor was indeed successful at appropriately inducing gratitude and indebtedness as intended.

Hypothesis 1: Conditional Effects.

The MANOVA results revealed significant conditional effects of the induction factor on relationship proximity and direct reciprocity. Post-hoc contrasts revealed participants who were induced to feel both gratitude and indebtedness had higher levels of relationship proximity and direct reciprocity compared to participants who received only the indebtedness or only the gratitude inductions. Thus hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2: Conditional Effects.

In examination of the Target Factor (Human vs. God), participants induced to think about benefits from God scored higher on transcendent indebtedness (but not transactional indebtedness), relationship proximity, and direct reciprocity than participants induced to think about benefits from other humans. Although God as a Target induced more transcendent indebtedness, relationship proximity, and reciprocity toward God, it did not predict higher diffuse reciprocity in the form of letter writing to children. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not supported. Moreover, the interaction of Target*Induction was significant for state gratitude, state transcendent indebtedness (both transactional and transcendent), relationship proximity, and direct reciprocity. See . Gratitude only to humans led to the least relational engagement in the forms of proximity and direct reciprocity. In contrast, gratitude and indebtedness to God led to the highest proximity.

State-predictor regressions

We ran more in-depth analyses to provide insight into the efficacy of the manipulations in individuals by examining how state-level responses aligned with the predicted associations for the hypotheses. To do this, we ran a multivariate regression analysis with our three dependent variables, (1) relationship proximity, (2) direct reciprocity, and (3) diffuse reciprocity, predicted by state gratitude, state transcendent indebtedness, state transactional indebtedness, and the interaction of state gratitude and state transcendent indebtedness included in the regression. The results predicting relationship proximity revealed a positive association for state gratitude (β=.36, p < .001) and state transcendent indebtedness (β=.52, p < .001) but a negative association for state transactional indebtedness (β=-.11, p < .001). There was also a significant interaction effect of state gratitude and state transcendent indebtedness predicting relationship proximity (β=.57, p < .05) such that those high on both reported particularly high relationship proximity towards their benefactor.

For direct reciprocity, there was a positive effect for state transcendent indebtedness (β=.62, p < .001) and transactional indebtedness (β=.20, p < .001), but neither state gratitude nor the interaction term was significant. Finally, the state levels of gratitude, indebtedness, and their interaction were not significant predictors of diffuse reciprocity, as indicated by the word count in the letters. Thus, as anticipated, individual differences in response to the conditions predicted relationship proximity and direct reciprocity. Nevertheless, more diffuse reciprocity was not predicted by conditional or individual state gratitude or indebtedness, suggesting other factors were at play. Thus, diffuse, pay it forward reciprocity is not as reliably predicted by conditional gratitude or indebtedness as is direct reciprocity and relationship proximity.

Study 2: cloud research experiment

The purpose of Experiment 2 was to replicate Experiment 1 findings in a more diverse, nationally respresentative sample and investigate how gratitude and indebtedness relate to different types of prosocial behavior (low-cost letter writing and high-cost charitable donation). We review what was replicated and report new findings.

Study 2 results

Participants

The sample was collected using Qualtrics Research Cloud Services. Based on preliminary power analysis and results from Experiment 1, our target N sample size was 600 participants. The initial launch began in the fall of 2021. Data collection ceased once the sample reached 600. However, due to sampling errors from the cloud services, the sample was not representative of the U.S. gender and ethnicity. So, the survey was re-launched in the spring of 2022 to better reach gender and ethnicity distributions representative of the U.S. population. For this reason, we had a larger sample size than anticipated. The final sample was N = 1,081, with around 170 participants in each condition (Mage = 44, 52% female, 62% White, 12% Black, 2%, 17% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 5% Other [numbers do not add up to 100% because participants were allowed to check more than one option]). Participants who did not identify as religious were excluded from the experiment per pre-registered exemption criteria.

Procedure, manipulations, measures

Procedures and measures were the same as those in Study 1, with the exception of an additional measure of prosocial behavior included at the end of the survey.

Diffuse reciprocity: charitable donation

Because the participants were receiving monetary compensation for their participation (unlike Study 1, where participants received course credit), a charitable donation option was added to the survey. Participants were asked whether they would be willing to donate a portion of their compensation to a pediatric hospital (on a scale from 0 to 100% of earnings). Including this measure in Experiment 1 was not feasible because participants were given course credit. This measure allowed us to compare different types of diffuse reciprocity (letter writing and charitable donation). After the survey, participants were debriefed and given full compensation for their time, regardless of the amount of money they indicated they would donate. In addition, based on pilot feedback, we asked participants if they felt rushed taking the survey (rated from 1 ‘not at all’ to 3 ‘yes, a lot’) as a control variable.

Analytic strategy

For Hypotheses 1–2, we followed the same analytic strategy to replicate Study 1 with Study 2 data. Hypothesis 3 and 4 were tested with MANOVAs, and multiple regression controlling for demographic variables (age, sex, and income) and a measure of how rushed the participant felt while taking the survey (from ‘a lot’, ‘a little’, to ‘not at all’) because they were significant predictors of the dependent variables.

Study 2 results

Conditional effects

Manipulation check

Similar to Study 1, results of the MANOVA indicated significant effects of the induction factor (Gratitude Only vs. Indebtedness Only vs. Gratitude & Indebtedness) on state gratitude and state indebtedness (both transactional and transcendent). Post-hoc contrasts revealed participants who were induced to feel both gratitude and indebtedness had higher levels of transcendent (want to repay) indebtedness compared to participants who received only the indebtedness or only the gratitude inductions. Participants who were induced to feel both gratitude and indebtedness also felt more state transactional (have to repay) indebtedness compared to the gratitude only condition. Please see for a more detailed breakdown of the results. Participants in the indebtedness only condition reported higher levels of both types of indebtedness compared to the gratitude only condition. These results show that the induction factor was indeed successful at appropriately inducing indebtedness as intended, though there was not an elevated level of gratitude for the combined condition as evinced in Study 1.

Hypothesis 1: Conditional Effects.

The MANOVA results revealed significant effects of the induction factor (Gratitude Only vs. Indebtedness Only vs. Gratitude & Indebtedness) on relationship proximity and direct reciprocity. Post hoc contrasts revealed that participants who were induced to feel both gratitude and indebtedness only felt more relationship proximity than the indebtedness only condition. Again, there was support for Hypothesis 1; the combination of gratitude and indebtedness was superior for activating relationship proximity and direct reciprocity compared to the indebtedness and gratitude conditions, respectively.

Hypothesis 2: Conditional Effects.

In examination of the Target Factor (Human vs. God), participants induced to think about benefits from God scored lower on state gratitude compared to those induced to think about benefits from humans. No other outcomes differed by Target, so Hypothesis 2 was not supported. Likewise, the interaction between Target and Induction was not significant.

State predictor regressions

As in Study 1, we ran multivariate regression analyses predicting prosocial outcomes with state gratitude and indebtedness (both types) scores. The results of the regression indicated that participants who felt more transcendent indebtedness (β=.33 p < .001) and gratitude (β=.56, p < .001) reported more relationship proximity, but no association was found between transactional indebtedness and relationship proximity. Participants who experienced more transcendent indebtedness (β=.46, p < .001) and gratitude (β=.29, p < .001) reported more direct reciprocity. In contrast, feeling more transactional indebtedness (β=-.19, p < .001) predicted less direct reciprocity. Further, participants exerted greater effort in letter writing when they reported higher levels of state gratitude (β=.19, p < .001) and state transcendent indebtedness (β=.16, p < .01). In contrast, those who reported more transactional indebtedness exerted less effort in the letter writing task (β=-.23, p < .001). In addition, we found an interaction effect for state gratitude and indebtedness predicting effort in letter writing (β=.23, p < .001), such that participants who experienced higher transcendent indebtedness paired with higher levels of gratitude were the highest on letter writing effort. Finally, regarding hypothesis 4, the results indicated that participants who reported more transcendent indebtedness and gratitude were not more likely to donate money. However, those who reported higher levels of transactional indebtedness were significantly more likely to donate money (β=.11, p < .05). Thus, we found partial support for hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 3: Secure Attachment to God Moderates Conditional Effects.

To test our hypothesis that attachment to God moderates the effects of the God Target on prosocial outcomes, we ran a MANOVA predicting prosocial outcomes (direct reciprocity, diffuse reciprocity: letter writing, diffuse reciprocity: monetary donation, and relationship proximity) using Target (God vs. Human), secure attachment to God, and an interaction variable (Target*God attachment) as independent variables. The results indicated that there was no main effect for the Target variable, but the interaction effect was significant η2 = 0.06, F(5, 874) = 10.65 p < .001. Specifically, secure attachment moderated the association between the God benefactor conditions and relationship proximity (η2 = 0.04, p < .001), direct reciprocity (η2 = 0.04, p < .001), and word count in the letters (η2 = 0.01, p < .01). In other words, those higher on secure attachment to God were more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors in the God conditions. The interaction effect was not significant for monetary donation.

Discussion

Virtue and gratitude scholars have long advocated for a portrait of gratitude that transcends episodic gratitude and includes moral action (Emmons & McCullough, Citation2004; Emmons, Citation2016; J. R. H. Tudge et al., Citation2015), but the key components necessary for specifying the moral mechanisms by which gratitude can induce prosociality have not been fully specified. We hypothesized that the link between feeling gratitude and expressing gratitude through prosocial action is transcendent indebtedness – an undervalued moral mechanism of reciprocal altruism (Ma et al., Citation2017; Nelson et al., Citation2022). Pioneering work on transcendent indebtedness to God as positive and paradigmatic suggests the field move away from a negative bias towards indebtedness, prompting researchers to explore the positive social and psychological functions of transcendent indebtedness (Nelson et al., Citation2022). Our findings support this new vision and valuation of indebtedness by showing that pairing gratitude with transcendent indebtedness magnifies the effect of gratitude on prosocial reciprocity. Specifically, we found individuals prompted to experience both gratitude and indebtedness had higher prosocial relational engagement (i.e. consistent effects for relationship proximity and direct reciprocity) than those who primarily experienced gratitude or indebtedness, but effects for diffuse reciprocity were less consistent.

In addition, we hypothesized that acknowledging God as a saliant and active benefactor in the lives of believers has the potential to bridge shallow gratitude with transcendent indebtedness, opening a viable path of self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. This hypothesis was supported with prosocial behaviors involving the social exchange dyad but was less easily induced in upstream altruism (i.e. diffuse reciprocity). In a more religious sample (Study 1), having God as a target of gratitude and indebtedness was associated with greater prosocial relational engagement (i.e. higher relationship proximity and direct reciprocity). However, in a less religious sample (Study 2), the effect of God as a target of gratitude in indebtedness was non-significant for all prosocial outcomes. However, moderation analyses with Study 2 data revealed having God as a target of gratitude and indebtedness did lead to greater relationship proximity, direct reciprocity, and diffuse reciprocity in the form of letter writing (but not monetary donation) for those who are securely attached to God. Overall, these experiments provide valuable insights into gratitude as a moral emotion and transcendent indebtedness as a moral mechanism.

Interpersonal gratitude comes with indebtedness

Our hypothesis testing demonstrated that we could successfully manipulate state gratitude and indebtedness to both God and humans in anticipated directions. Interestingly, gratitude and indebtedness were largely co-occurring, a finding supported by prior research and theory (Emmons & McCullough, Citation2004; Emmons, Citation2016; J. R. H. Tudge et al., Citation2015). These experimental results provide compelling evidence that gratitude and indebtedness are highly interconnected in social exchange. In other words, interpersonal gratitude is likely to involve at least some level of indebtedness. Therefore, we speculate that the effects of interpersonal gratitude interventions are likely to be attributable to mechanisms associated with both gratitude and indebtedness, and future work should attend to these distinctions.

Varieties of gratitude and indebtedness

We were able to create conditions where (1) gratitude was high and indebtedness was low (shallow gratitude ‘gratitude-only’ conditions), (2) indebtedness was high and gratitude was low (transactional indebtedness ‘indebtedness-only’ conditions), and (3) both gratitude and indebtedness were high (transcendent indebtedness ‘gratitude and indebtedness’ conditions). These variations in gratitude and indebtedness levels led to distinctive conditions and state-level responses, which led to significantly different prosocial relational outcomes. This provides evidence that gratitude and indebtedness are co-occurring, multidimensional, and dynamic. Most interestingly, we induced participants to experience obligated, transactional indebtedness (have to repay) in the relative absence of gratitude (conditions 2 and 5), or they experienced agentic, transcendent indebtedness (want to repay) in the relative presence of gratitude (conditions 3 and 6). Those with agentic, transcendent forms of indebtedness accompanied by gratitude showed the highest prosociality. The exception to this was the finding that those who experienced higher levels of transactional indebtedness were more likely to donate money, perhaps because money aligns with transactional thinking. These results reinforce prior findings that ‘shoulds’ can be perceived as ‘wants’ (Janoff-Bulman & Leggatt, Citation2002; Kong & Belkin, Citation2019) when an end-state emotion (gratitude) accompanies a need-state emotion (indebtedness). This agentic orientation towards responsibilities may be especially common in individualistic societies (Buchtel et al., Citation2018), which has profound implications for motivating prosocial action.

When the benefactor is God

Gratitude and indebtedness to God seem to have similar cognitive and emotional appraisals as interpersonal indebtedness – with one remarkable exception. The prosocial benefits of gratitude and indebtedness to God are magnified in highly religious individuals, which aligns with prior research (Rosmarin et al., Citation2011). Moderation analyses provided evidence that prosocial outcomes are enhanced by interventions involving God as a benefactor when the individual has a secure attachment with God. These findings should be tested in a longitudinal intervention to see whether these differences have a lasting effect on outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting the findings of this project. First, our samples were from the United States. Thus, results might not generalize to populations from different cultures and geographical regions because prior work has demonstrated cultural variations in gratitude and indebtedness (Naito & Sakata, Citation2010; Oishi et al., Citation2019; Shiraki & Igarashi, Citation2016; Washizu & Naito, Citation2015). Second, although our measure of diffuse reciprocity was a behavioral measure, our other outcome variables were self-report measures, which have well-known limitations such as social desirability bias. Third, the measurement of state emotions was thin. However, other measures such as PANAS (Watson et al., Citation1988) have used this single-item structure before with considerable success.

Future directions and conclusion

Our results indicate that indebtedness is not inherently good or bad, as has previously been suggested (Algoe et al., Citation2008; Greenberg & Shapiro, Citation1971; P. Watkins et al., Citation2006). Rather, indebtedness can be either transactional or transcendent, depending on the four factors outlined in prior work (Nelson et al., Citation2022). Further, gratitude paired with indebtedness promoted the best prosocial and relationship outcomes. Therefore, we suggest (1) moving past dichotomized models of gratitude and indebtedness, (2) acknowledging that there are varieties of gratitude and indebtedness, and (3) improving the measurement accuracy of both constructs.

These findings have applied implications. First, understanding and cultivating the moral virtue of gratitude requires consideration of indebtedness. Gratitude and indebtedness seem similar to other virtues that are enhanced with virtue pairing, such as courage and patience (Ratchford et al., Citation2022) and love and loyalty (P. Wong & Wong, Citation2018). Future research should test whether traditional gratitude interventions might be enhanced by more explicitly attending to indebtedness.

In conclusion, the present findings expand current models of reciprocity and prosocial behavior that position gratitude as the central or lone figure. Instead, we present evidence for transcendent indebtedness as a misunderstood and undervalued player in prosocial interactions. Including God as a benefactor was also novel – providing cues that interpersonal and divine gratitude may have similar cognitive structures and appraisals but that gratitude and indebtedness to God have additional motivating power for the religiously devout.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/y9bqw/?view_only=a4ffdf123ea54885829c055d2c038cae.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/y9bqw/?view_only=a4ffdf123ea54885829c055d2c038cae.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful and indebted to our research assistant, Russ Amelang, for his contributions to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Pre-registration and data can be found at https://osf.io/bygrp.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2190926

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In contrast, in ancient polytheistic and pagan religions, where ritualistic sacrifices and offerings to gods are common, we might observe a different pattern of reciprocal behavior.

2. The present work presents a portion of a larger pre-registered project.

References

- Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x

- Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8(3), 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425

- Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior. Psychological Science (0956-7976), 17(4), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

- Batson, C. D. (2015). What’s wrong with morality?: A social-psychological perspective. In What’s wrong with morality?. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199355549.001.0001/acprof-9780199355549

- Baumeister, R. F., & Ilko, S. A. (1995). Shallow gratitude: Public and private acknowledgement of external help in accounts of success. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 16(1–2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1601&2_12

- Beck, R., & McDonald, A. (2004). Attachment to god: The attachment to god inventory, tests of working model correspondence, and an exploration of faith group differences. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 32(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710403200202

- Beeler Duden, S., & Vaish, A. (2020). Paying it forward: The development and underlying mechanisms of upstream reciprocity. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 192, 104785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104785

- Bradshaw, M., Kent, B. V., vanOyen Witvliet, C., Johnson, B., Jang, S. J., & Leman, J. (2022). Perceptions of accountability to god and psychological well-being among us adults. Journal of Religion and Health, 61(1), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01471-8

- Braun, T., Rohr, M. K., Wagner, J., & Kunzmann, U. (2018). Perceived reciprocity and relationship satisfaction: Age and relationship category matter. Psychology and Aging, 33(5), 713–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000267

- Buchtel, E. E., Ng, L. C. Y., Norenzayan, A., Heine, S. J., Biesanz, J. C., Chen, S. X., Bond, M. H., Peng, Q., & Su, Y. (2018). A sense of obligation: Cultural differences in the experience of obligation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(11), 1545–1566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218769610

- Emmons, R. A. (2016). Is gratitude the queen of virtues and ingratitude king of the vices? In D. Carr (Ed.), Perspectives on gratitude: An interdisciplinary approach. pp. 141–153. Routledge.

- Emmons, R. A., ed, & McCullough, M. E. (Eds.). (2004). The psychology of gratitude. Oxford University Press. http://erl.lib.byu.edu/login/?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=egi&AN=69188294&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Evans, C. S. (2021). Accountability and the fear of the lord. Studies in Christian Ethics, 34(3), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/09539468211009756

- Forster, D. E., Pedersen, E. J., Smith, A., McCullough, M. E., & Lieberman, D. (2017). Benefit valuation predicts gratitude. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.06.003

- Frijda, N. H. (2009). Emotion experience and its varieties. Emotion Review, 1(3), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073909103595

- Fujisaki, C. (2020). A study evaluating mindfulness and naikan-based therapy: AEON-HO for attachment style, self-actualization, and depression. Psychological Reports, 123(2), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118811106

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Greenberg, M. S., Block, M. W., & Silverman, M. A. (1971). Determinants of helping behavior: Person’s rewards versus other’s costs. Journal of Personality, 39(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1971.tb00990.x

- Greenberg, M. S., & Shapiro, S. P. (1971). Indebtedness: An adverse aspect of asking for and receiving help. Sociometry, 34(2), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786418

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences 200907773044 (pp. 200907773044 (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

- Janoff-Bulman, R., & Leggatt, H. K. (2002). Culture and social obligation: When “shoulds” are perceived as “wants. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(3), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2001.2345

- Kong, D. T., & Belkin, L. Y. (2019). Because I want to share, not because I should: Prosocial implications of gratitude expression in repeated zero-sum resource allocation exchanges. Motivation and Emotion, 43(5), 824–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09764-y

- Lawler, E. J., & Thye, S. R. (2009). Altruism and prosocial behavior in groups. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://www.lib.byu.edu/cgi-bin/remoteauth.pl?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=512783&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Layous, K., Sweeny, K., Armenta, C., Na, S., Choi, I., Lyubomirsky, S., & Bastian, B. (2017). The proximal experience of gratitude. PLoS One, 12(7), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179123

- Ma, L. K., Tunney, R. J., & Ferguson, E. (2017). Does gratitude enhance prosociality?: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 601–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000103

- Mauss, M. (1966). The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. Cohen & West LTD.

- McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249

- Naito, T., & Sakata, Y. (2010). Gratitude, indebtedness, and regret on receiving a friend’s favor in Japan. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychological Sciences, 53(3), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.2117/psysoc.2010.179

- Nelson, J. M., Hardy, S. A., & Watkins, P. (2022). Transcendent indebtedness to god: A new construct in the psychology of religion and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 15(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000458

- Nelson, J. M., Hendricks, J. J., Cazier, J. C., Hardy, S. A., & Wingate, D. (2023). Religious exemplars’ experience of indebtedness to God: Employing innovative machine learning to explore a novel construct. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2190925

- Oishi, S., Koo, M., Lim, N., & Suh, E. M. (2019). When gratitude evokes indebtedness. Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being, 11(2), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12155

- Parker, S. C., Majid, H., Stewart, K. L., & Ahrens, A. H. (2017). No thanks! Autonomous interpersonal style is associated with less experience and valuing of gratitude. Cognition & Emotion, 31(8), 1627–1637. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1256274

- Peng, C., Malafosse, C., Nelissen, R. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2019). Gratitude, indebtedness, and reciprocity: An extended replication of Bartlett & DeSteno (2006). Social Influence, 15(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2019.1710248

- Peng, C., Nelissen, R. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2018). Reconsidering the roles of gratitude and indebtedness in social exchange. Cognition & Emotion, 32(4), 760–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1353484

- Ratchford, J. L., Cazzell, A., & Schnitker, S. A. (2022). The virtue counterbalancing circumplex model: An illustration with patience and courage [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Baylor University.

- Roberts, R., & Telech, D. (Eds.). (2019). The moral psychology of gratitude. https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781786606020/The-Moral-Psychology-of-Gratitude

- Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Cohen, A. B., Galler, Y., & Krumrei, E. J. (2011). Grateful to god or just plain grateful? A comparison of religious and general gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(5), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.596557

- Shiraki, Y., & Igarashi, T. (2016). What factors of prosocial behavior evoke recipients’ gratitude and indebtedness? An experimental examination. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 87(5), 474–484. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.87.15040

- Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

- Torrance, A. (2021). Accountability as a virtue. Studies in Christian Ethics, 34(3), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/09539468211009755

- Tsang, J. A. (2006). The effects of helper intention on gratitude and indebtedness. Motivation & Emotion, 30(3), 198–204.

- Tsang, J., Schnitker, S. A., Emmons, R. A., & Hill, P. C. (2021). Feeling the intangible: Antecedents of gratitude toward intangible benefactors. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1952480

- Tudge, J., & Freitas, L. B. D. L. (2018). Developing gratitude in children and adolescents. Cambridge University Press. https://www.lib.byu.edu/cgi-bin/remoteauth.pl?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1578719&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Tudge, J. R. H., Freitas, L. B. L., & O’brien, L. T. (2015). The virtue of gratitude: A developmental and cultural approach. Human Development, 58(4–5), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444308

- Vaish, A., & Hepach, R. (2020). The development of prosocial emotions. Emotion Review, 12(4), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919885014

- Washizu, N., & Naito, T. (2015). The emotions sumanai, gratitude, and indebtedness, and their relations to interpersonal orientation and psychological well-being among Japanese university students. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000037

- Watkins, P. (2018). Gratitude to God Scale [ Unpublished manuscript]. School of Psychology, Eastern Washington University.

- Watkins, P., Scheer, J., Ovnicek, M., & Kolts, R. (2006). The debt of gratitude: Dissociating gratitude and indebtedness. Cognition & Emotion, 20(2), 217–241.

- Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude resentment and appreciation test. PsycTESTS. https://doi.org/10.1037/t60955-000

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wong, Y. J., Owen, J., Gabana, N. T., Brown, J. W., McInnis, S., Toth, P., & Gilman, L. (2018). Does gratitude writing improve the mental health of psychotherapy clients? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1169332

- Wong, P., & Wong, L. (2018). The spiritual foundation for a healthy marriage and family. In Existential Elements of the Family. pp. 33–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1q26mt5.5

- Yu, H., Cai, Q., Shen, B., Gao, X., & Zhou, X. (2017). Neural substrates and social consequences of interpersonal gratitude: Intention matters. Emotion, 17(4), 589–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000258