ABSTRACT

Three pre-registered experiments (N = 998) examined affective, cognitive, and environmental self-transcendent experiences aimed at eliciting general humility (GH) and intellectual humility (IH). In Study 1, self-transcendent positive emotions elicited IH and gratitude emerged as a noteworthy predictor. Self-transcendent emotions occur in response to stimuli that are difficult to grasp logically, which underscores one’s intellectual limitations. In Study 2, cognitive appraisals of sanctification – involving interpreting something as sacred – were predictive of greater IH. Phenomena that are considered sacred are often experienced as ineffable and unknowable, which likewise increases awareness of one’s intellectual limits. In Study 3, individuals walking in nature experienced higher levels of self-transcendent emotions, sanctification appraisals, and GH than individuals walking in other settings. Although much of the literature discusses GH and IH as traits, this research emphasizes that they also function as dynamic states that can shift in response to emotions, cognitions, and environmental contexts.

Vincent de Paul, a 17th Century French Catholic priest, has been quoted, ‘Humility is nothing but truth, and pride is nothing but lying’. Centuries later, psychologists’ definitions of humility converge on the concept of having a truth-based, accurate view of one’s flaws, weaknesses, and strengths (Van Tongeren et al., Citation2019). Humility is not only a conceptualization of self, but a conceptualization of self in relation to others via features such as being other-focused and egalitarian (Chancellor & Lyubomirsky, Citation2013; Tangney, Citation2000). A more recent construct of interest is humility in the domain of knowledge. Intellectual humility (IH) involves an awareness of personal intellectual limitations – understanding and accepting that what you know and believe could be inaccurate. As with general humility (GH), interpersonal features of IH have been identified, such as appreciating others’ intellectual strengths (Porter et al., Citation2022).

A reason the scientific study of humility was neglected for so long (Tangney, Citation2000) may be that the construct of humility challenges the paradigm of the centrality of the self, which is foundational in psychology. Now that many benefits to GH and IH have been established, underlying mechanisms need to be explored in more detail. GH and IH can be promoted through minimized self-focus and increased sense of connectedness to others, which are the defining features of self-transcendence. In this paper, we examine affective, cognitive, and environmental avenues to self-transcendence in relation to GH and IH.

The benefits of general and intellectual humility

The most robust benefits of humility are relational and result from the selflessness, compassion, and empathy conferred by humility, which are expressed through altruism, forgiveness, generosity, cooperation, and self-control (Worthington & Allison, Citation2018; Worthington et al., Citation2021). Though the evidence is less plentiful and robust than with relational benefits, humility is also associated with better psychological well-being and physical health (Tong et al., Citation2019; Worthington & Allison, Citation2018; Worthington et al., Citation2021). Humility motivates positive actions because an accurate understanding of self allows individuals to acknowledge their needs for self-improvement, be open to critical feedback, and pursue personal growth (Armenta et al., Citation2017).

Shifting to IH, awareness of one’s intellectual limitations offers benefits in the domain of reasoning and learning. IH is associated with less cognitive biases (Bowes et al., Citation2022; Cao & Li, Citation2023), finding value in opposing perspectives (Hodge et al., Citation2021), better judgment of the strength of persuasive arguments (Leary et al., Citation2017), and less unwarranted conspiracy beliefs (Bowes et al., Citation2021). IH is also associated with investing more effort in learning about a topic one failed to master in the past (Porter et al., Citation2020). Perhaps for these reasons, those higher in IH possess more knowledge and have more accurate perceptions of their knowledge (Deffler et al., Citation2016; Krumrei-Mancuso et al., Citation2020).

These qualities of IH also confer interpersonal benefits. Individuals higher in IH judge others less on the basis of their opinions (Leary et al., Citation2017) and poses more qualities such as empathy, gratitude, benevolence, and less power seeking (Krumrei-Mancuso, Citation2017). In the political domain, IH is associated with being less likely to derogate the intellectual capabilities or moral character of opponents and a greater willingness to befriend opponents (Stanley et al., Citation2020). Political IH is also associated with less favoritism of in-groups relative to outgroups (Bowes et al., Citation2020; Krumrei-Mancuso & Newman, Citation2020) and more political tolerance and less social dominance orientation (Krumrei-Mancuso & Newman, Citation2021). In the religious domain, IH also decreases the threat of ideological differences (Zhang et al., Citation2018) and is associated with being more likely to forgive someone following a religious conflict (Zhang et al., Citation2015, Citation2018).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, people like and want to interact with those who engage in GH and IH behaviors (Fetterman et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, humility is not easy to develop or practice in an individualistic culture (Worthington & Allison, Citation2018). Given the individual and interpersonal benefits of GH and IH, it is worth exploring how to elicit and bolster these qualities.

Self-transcendent experience as a mechanism for eliciting universality and humility

In the field of psychology, key figures such as William James, Viktor Frankl, Erik Erikson, and Abraham Maslow have emphasized the importance of self-transcendence. Historical work described self-transcendence in terms of motivations, beliefs, values, or traits. Recent empirical work has highlighted self-transcendent experience: transient mental states involving decreased self-salience and increased feelings of connectedness with others or one’s surroundings (Yaden et al., Citation2017). The decreased self-focus of self-transcendence might promote GH and IH via greater psychological objectivity and reduced emphasis on how a situation makes one feel about oneself, which promote a greater willingness to engage in self-discovery, a greater likelihood of noticing personal and intellectual limitations, and overall less defensive, more accurate views of self. The increased connectiveness of self-transcendence might promote universality, involving beliefs about the interconnection of all life that comes with a sense of shared responsibility for others. The increased connectiveness of self-transcendence might also promote GH and IH by offering individuals a new perspective of themselves as smaller parts situated within a larger whole of interrelationships, offering more modesty in self-concepts and appreciation for the limited scope of one’s own perspective. The current research examined three antecedents of self-transcendent experiences in relation to GH and IH: self-transcendent positive emotions, cognitive appraisals of sanctification, and encounters with nature.

Self-transcendent positive emotions in relation to universality and humility

We were interested in the role of self-transcendent emotions (STE) – as affective avenues to self-transcendent experience – in helping individuals gain more accurate concepts of self and intellect. STE are distinct from other emotions in that they do not primarily concern the self, self-enhancement, or personal goals (Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013). STE direct attention away from the self because they are elicited by external stimuli appraised as marvelous, admirable, vast, pure, beautiful, or sacred – stimuli that are, by definition, difficult for humans to comprehend (Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013). We focused specifically on self-transcendent positive emotions (STPE) – such as elevation, appreciation, admiration, inspiration, gratitude, love, and awe. We did so because positive emotions, in general, increase people’s ability to process and integrate negative self-relevant information (Raghunathan & Trope, Citation2002) and broaden people’s range of perceptions and ideas, resulting in new cognitive resources (Fredrickson et al., Citation2008). We believe these trends may be particularly relevant in the case of STPE. As STPE increase feelings of unity and connection to the outer world, other people, and humanity as a whole (Fredrickson, Citation2009; Johnson & Fredrickson, Citation2005; Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013), we believe they will be associated with universality, the belief that one is interconnected with others and one’s surroundings. Further, because STPE are stimulus-focused rather than self-focused and broaden thoughts beyond the self (Johnson & Fredrickson, Citation2005), we believe this offers a new, more accurate frame of reference for one’s self-concept and therefore greater GH. Finally, because STPE occur in response to complexities that are difficult to comprehend, they elicit curiosity, interest, exploration, and demonstrate a need to adjust or expand one’s existing mental structures (Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013), reinforcing a sense of IH.

Much of what we know about STPE is based on the study of awe. Awe results in individuals experiencing themselves as small relative to something greater (Bai et al., Citation2017; Piff et al., Citation2015). Across collectivist and individualistic cultures, awe results in a sense of self-diminishment and decreased self-focus (Bai et al., Citation2017; Piff et al., Citation2015). Interestingly, awe brings people’s perceived self-size more in line with the perceived size of others in their social network, without diminishing people’s sense of status, rank, or self-esteem (Bai et al., Citation2017). This suggests awe promotes GH through opportunities for individuals to see themselves more accurately vis-à-vis having a false positive or false negative view of self. Indeed, awe-prone individuals are rated as being more humble by those who know them well and they self-report greater GH (Stellar et al., Citation2018). Awe-inductions also cause individuals to self-report more GH (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019, Study 1; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018) and sense of small self (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019, Study 2), and to express more GH by presenting a more balanced view of their strengths and weaknesses to others (Stellar et al., Citation2018).

Less literature has hinted at links between awe and IH. For example, dispositional awe-proneness is correlated with less need for cognitive closure, meaning individuals who frequently experience awe may be more likely to realize their existing knowledge is inadequate and, for this reason, are more open to continue information processing (Shiota et al., Citation2007). More directly, experimentally induced states of awe are associated with people reporting greater IH compared to an induced state of amusement or a control condition (Kim et al., Citation2023).

What clouds our current understanding of the relationship between self-transcendence and GH/IH is that the literature is dominated by the study of awe, often in comparison to emotions that are not self-transcendent in nature (non-STPE), such as happiness, amusement, or pride. However, it seems awe inductions result not only in awe, but in other STE, as well (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019; Saroglou et al., Citation2008). Further, Kim et al. (Citation2023) found a state of flow predicted IH more strongly than a state of awe. This suggest the benefits of awe documented in the literature, including increased humility, may be the result of self-transcendent emotions or experiences more generally. There is a need to examine and compare a broader range of STPE as well as other forms of self-transcendence in relation to GH and IH.

Cognitive appraisals of sanctification in relation to universality and humility

To expand the study of self-transcendence in relation to GH and IH, we examined a cognitive appraisal element of self-transcendence by exploring sanctification. There is a suggestion that sanctification appraisals and STPE have a reciprocal relationship in which they elicit one another (Preston & Shin, Citation2017; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013).

Sanctification is the cognitive process of interpreting something as a manifestation of sacredness, such as perceiving something as being miraculous or holy (Mahoney et al., Citation1999). This can involve theistic interpretations that something has divine character or significance or nontheistic interpretations that something is imbued with sacred qualities such as ultimacy or boundlessness. Sanctification has been studied in many aspects of life, including strivings, relationships, work, and the body and is consistently associated with better psychosocial adjustment (Mahoney et al., Citation2022 but to our knowledge, has not been examined in relation to GH or IH.

Sanctification appraisals elicit self-transcendence by placing a person in relation to a source of sacredness. This can facilitate a sense of connectedness to that which exists outside of the self, resulting in universality beliefs. The encounter with sacredness can also facilitate seeing oneself as a much smaller part of an intricate whole and can decrease self-salience in relation to something extraordinary. These processes can increase psychological objectivity to help people gain a more accurate perspective of themselves, resulting in greater GH. In addition, perceived sources of sacredness are typically mysterious and beyond understanding. The inability to cognitively grasp a sacred stimulus can help people grasp their cognitive fallibility. Sanctification may also elicit a sense of the infinite, which might emphasize humans’ intellectual finitude.

Nature in relation to self-transcendence and humility

Experiencing the grandeur of nature and the intricate interrelationships that make up natural environments can have self-diminishing effects, decrease self-focus, and might allow individuals to view themselves as one small part of a more complex whole. As such, nature exposure has been associated with the experience of self-transcendence (Ballew & Omoto, Citation2018; Castelo et al., Citation2021; Davis & Gatersleben, Citation2013; Neill et al., Citation2018; Williams & Harvey, Citation2001). This includes nature eliciting STPE, with a focus on awe dominating the literature (Ballew & Omoto, Citation2018; Joye & Bolderdijk, Citation2015; Piff et al., Citation2015; Shiota et al., Citation2007; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, Citation2012). Self-transcendence is most likely to occur in nature that is vast, overwhelming, unexpected, extraordinary, defies an individual’s understanding, and requires cognitive accommodation (Keltner & Haidt, Citation2003). Nature elicits STPE not only because it is beautiful (Van Cappellen, Citation2017; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013), but because it is a perceptually complex and information-rich stimulus (Shiota et al., Citation2007).

When nature elicits STPE, such as a sense of ineffability, awe, wonder, and reverence, this is often also associated with feelings of insignificance and humility (McDonald et al., Citation2009). Humility as a response to nature is not only an acknowledgement of the beauty witnessed, but also a response to the unseen and unknowable forces of nature (McDonald et al., Citation2009), which bridges into IH. The perceptual complexity of nature and its ability to necessitate cognitive accommodation has implications for people’s awareness of their intellectual limitations.

Nature also offers opportunities for people to experience sacred or spiritual dimensions (Naor & Mayseless, Citation2020). One literature review indicated a majority of visitors to park and wilderness areas seek spiritual outcomes (Heintzman, Citation2009). It is through sanctification appraisals that people experience aspects of nature as sacred, for example, by interpreting beauty, the sublime, or the enduring cycles of nature as representing spiritual realities (Johnson, Citation2002). The elements of such encounters that might promote GH and IH include reverence, wonder, awe, mystery, lack of total understanding, relation to something other and greater than the self, and a heightened sense of awareness beyond the everyday and corporeal world (Ashley, Citation2007).

Our conceptual model and the current research

Foundational to our work are previous findings that awe inductions result in greater humility via a sense of small self (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019) and appraisals of vastness and associated need for cognitive adaptation result in awe, which elicits humility via a sense of self-diminishment (Stellar et al., Citation2018). We expand this literature by examining sanctification appraisals, which have yet to be explored in relation to STPE or humility, and by contrasting inductions of a range of STPE to one another.

Mirroring previous STPE research (e.g. Stellar et al., Citation2018; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013), we draw on the appraisal tendency framework, which describes that a discrete set of cognitive dimensions differentiate particular emotional states and their effects (Lerner & Keltner, Citation2000). Cognitive appraisals, being the automatic evaluations people make about the personal significance of what they are encountering, elicit particular types of emotions. Particular emotions also give rise to specific cognitive and motivational processes and action tendencies. Thus, emotions arise from and give rise to implicit cognitive predispositions to appraise future events in line with the central appraisal patterns characterizing an emotion (Lerner & Keltner, Citation2000).

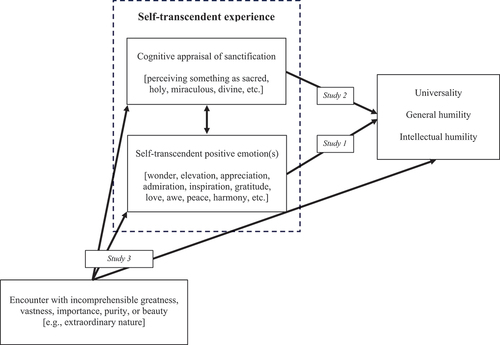

summarizes our conceptual model, for which we tested various component parts across three studies. When people encounter stimuli that are incomprehensively marvelous, admirable, pure, beautiful, vast, great, or important, this can result in both cognitive appraisals of sanctification and STPE. Based on the appraisal tendency framework and previous research, sanctification appraisals and STPE will have mutually reinforcing effects (Preston & Shin, Citation2017; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Van Cappelen & Rime, Citation2013). Cognitive appraisals of sanctification and STPE focus attention away from the self. They are self-disinterested, self-diminishing, and increase a sense of connection to people and things outside of the self. For these reasons, we expect them to elicit GH, IH, and beliefs in the interconnection of life, known as universality.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of cognitive appraisals of sanctification and self-transcendent emotions resulting in general and intellectual humility.

Although links between self-transcendence and GH have been observed a number of times in the literature (McDonald et al., Citation2018; Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018), links between self-transcendence and IH have only recently been noted (Kim et al., Citation2023). Interestingly, appraisal tendencies relate not only to the themes of people’s cognitive appraisals, but also to their depth of thought. Because appraisals of sanctification and STPE are based, in part, on the incomprehensibility of a stimulus, they may function similarly to uncertainty appraisals, which result in more complex and deep rather than simple and shallow cognitive processing (Tiedens & Linton, Citation2001). This offers additional support for exploring whether sanctification appraisals and STPE relate to IH, a form of meta-cognition correlated with reflective thinking (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., Citation2020; Leary et al., Citation2017).

The hypotheses, procedures, and analyses for the three studies reported in this paper were preregistered on the Open Science Framework: Studies 1 and 2 at https://osf.io/h3qrn and Study 3 at https://osf.io/u52qg.Footnote1 All three studies were approved by the Seaver Institutional Review Board at Pepperdine University Protocol #: 21-06-1606 and participants endorsed informed consent forms prior to participating.

Study 1: using self-transcendent positive emotions to elicit universality, general humility, and intellectual humility

Previous research has demonstrated links between awe and the self-loss (Bai et al., Citation2017; Piff et al., Citation2015) and inter-connectedness components of self-transcendence (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019; Shiota et al., Citation2007), GH (Nelson-Coffey et al., Citation2019; Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018), and IH (Kim et al., Citation2023). The current study expands this work by eliciting not only awe, but a variety of STPE. Based on our reviewed theory, we hypothesized STPE, as states of self-transcendence, would result in more universality, GH, and IH.

Method

Materials

Emotion induction

Participants were randomly assigned to think and write about a time they experienced one of 14 different positive emotions. Eight of these emotions were categorized as STPE: awe, wonder, grateful, love, admiration, elevation, peace, and harmony. Six of the emotions were categorized as non-STPE: satisfied, determined, amused, happy, excited, and enthusiastic. Previous research has successfully used similar paradigms to evoke emotions (e.g. Bai et al., Citation2017; Shiota et al., Citation2007; Stellar et al., Citation2018; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, Citation2012).

Universality

The 9-item Universality subscale of the Spiritual Transcendence Scale (Piedmont, Citation1999) was used to assess feelings and beliefs related to the connectedness aspect of self-transcendence, focusing on beliefs in the interconnection of all life and a sense of shared responsibility for others. Items were rated on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree and summed (α = .92).

Humility

The 6-item Brief State Humility Scale (Kruse et al., Citation2017) was used as a measure of state humility. Items were rated on a 7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Relevant items were reverse scored and then all items were summed (α = .78).

Intellectual humility

Two scales of IH were used to assess humility in the domain of knowledge. Items were edited slightly to reflect state IH. The 6-items of the Intellectual Humility Scale (Leary et al., Citation2017) were rated on a 5-point scale from not at all like me to very much like me and summed (α = .86). The 6-item Lack of Intellectual Overconfidence subscale of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale (CIHS; Krumrei-Mancuso & Rouse, Citation2016) were rated on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree and summed (α = .63).

Participants, design, and procedure

Participant characteristics are described in . Surveys were completed online via Qualtrics. Using simple randomization, participants were assigned to an emotion induction consisting of one of 14 emotion categories. A 15th category, proud, was deleted prior to analyses given its relation to the construct of humility. Participants were asked to spend one minute thinking about a time they felt their assigned emotion. Participants then wrote about the circumstances, details and feelings surrounding the time they experienced the emotion. Next, participants rated on a scale of 0 to 10 how much they felt the assigned emotion in the present moment. Finally, participants completed counterbalanced measures of universality, humility, and two measures of IH.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

We applied two procedures associated with better data reliability (Rouse, Citation2015): we deleted listwise participants who at the end of the survey indicated they had not been attentive or honest in their survey responses (n = 4) and participants who failed an attention check during the survey (n = 3). We also removed participants who were outliers on a variable of interest according to the outlier labeling rule using a 2.2. multiplier (n = 8).

Results

Comparison of self-transcendent and non-self-transcendent positive emotions

We used t-tests to examine whether participants assigned to a STPE induction (n = 235) would express higher levels of universality, GH, and IH than participants assigned to a non-STPE induction (n = 183). Homogeneity of variance between the groups was met in each case. Following the induction, the two groups did not differ significantly in universality, t(416) = 1.23, p (2-tailed) = .22, Cohen’s d = .12, or GH, t(416) = .74, p (2-tailed) = .46, Cohen’s d = .07. However, the two groups differed in IH on the basis of the Intellectual Humility Scale, t(416) = 2.16, p (2-tailed) = .031, Cohen’s d = .21, with those receiving a STPE induction (M = 30.57, SD = 3.93) reporting higher levels of IH than those receiving a non-STPE induction (M = 29.68, SD = 4.45). For the Lack of Intellectual Overconfidence subscale of the CIHS, the results were significant when using a 1-tailed comparison (p = .028), but the difference between groups only approached significance with a 2-tailed test: t(416) = 1.91, p (2-tailed) = .056, Cohen’s d = .19, with the pattern supporting higher IH for those receiving a STPE induction (M = 19.91, SD = 3.40) compared to a non-STPE induction (M = 19.27, SD = 3.36).

Comparison of emotion categories

We conducted pre-registered exploratory analyses to examine if particular STPE were more robust in eliciting universality, GH, or IH. An analysis of variance comparing all emotion categories to one another indicated that only lack of intellectual overconfidence (IH) differed between the groups, F(13, 404) = 2.08, p = .014. Multiple comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment indicated that the gratitude induction resulted in greater IH (n = 31, M = 21.42, SD = 3.04) than the happiness induction (n = 26, M = 18.19, SD = 3.45), p = .028.

When comparing only the STPE categories to one another, differences again emerged only for lack of intellectual overconfidence (IH), F(7, 227) = 2.12, p = .042. Multiple comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment indicated that the gratitude induction resulted in greater IH (n = 31, M = 21.42, SD = 3.04) than the harmony induction (n = 26, M = 18.54, SD = 3.56), p = .038.

Discussion

The vast majority of research on STPE in relation to humility has focused on awe. The current work aimed to expand this by examining and comparing other STPE. Consistent with our hypothesis, STPE elicited IH to a greater extent than non-STPE. This supports the path from STPE to IH (). Because STPE often occur in response to marvelous complexities that are difficult to comprehend, they are likely to result in greater realization of one’s intellectual limits. Our findings parallel previous work linking awe to IH (Kim et al., Citation2023) and advance research linking STPE to cognitive processing (Johnson & Fredrickson, Citation2005) and need for cognitive closure (Shiota et al., Citation2007).

In our exploratory analyses, gratitude stood out as a stronger predictor of IH than other emotions. This expands previous research observing correlational links between gratitude and IH (Krumrei-Mancuso, Citation2017). More work is needed to understand why gratitude results in greater IH. In prior research, viewing others as responsive to one’s needs was associated with indicators of IH (Reis et al., Citation2018). Since gratitude involves perceiving another person’s good intentions, it likely functions similarly to perceived social responsiveness.

We did not find support for our hypothesis that STPE would elicit universality to a greater extent than non-STPE. Universality taps into a trait reflecting beliefs about being interconnected with others and one’s surroundings. The current findings reinforce the distinctness of self-transcendent experiences, which involve transient mental states of increased feelings of connectedness with others, from self-transcendent beliefs, values, and traits (see Yaden et al., Citation2017). Given that we only evaluated the inter-connectedness aspect of self-transcendence in this study via our measure of universality, it would be valuable to assess the self-loss or decreased self-salience aspect of self-transcendence in relation to STPE in the future.

We also did not find support for our hypothesis that STPE would elicit GH to a greater extent than non-STPE. This is surprising given that previous studies have found links between awe and GH (Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018). Although, findings have been inconsistent. For example, Nelson-Coffey et al. (Citation2019) found an awe induction elicited greater humility in one study (Study 1), but not another (Study 2). Further, research suggests some STPE (primarily awe) are associated with feeling small whereas others are not (e.g. love and gratitude; Campos et al., Citation2013). Perhaps for this reason, the composite of STPE was not associated with more GH. However, when conducting exploratory analyses, we also did not find that particular STPE predicted GH better than others.

In this study, we induced STPE to elicit GH and IH, however, it is worth noting the relationship may be bi-directional. For example, Keltner and Haidt (Citation2003) suggested that awe may be more likely to occur in individuals whose knowledge structures are less fixed. This suggests those higher in IH may be more likely to experience some forms of STPE. It would be worth examining bi-directional relationships between STPE and both GH and IH in future research.

Study 2: using cognitive appraisals of sanctification to elicit universality, general humility, and intellectual humility

In Study 1, we examined affective responses to appraising a stimulus as extraordinary. In Study 2, we directly examined a particular form of cognitive appraisal – sanctification— or the interpretation that something is a manifestation of sacredness. Based on our reviewed theory, we hypothesized sanctification appraisals would result in greater universality, GH, and IH than cognitive appraisals that contrast with sanctification.

Method

Materials

Cognitive appraisal induction

Participants were randomly assigned to think and write about either a time they sanctified something or a time they interpreted something as non-sacred. Participants were assigned to one of six sanctification appraisals (sacred, divine, miraculous, spiritual, holy, blessed) or one of five appraisals that contrast with sanctification (earthly, friendly, routine, temporary, ordinary).

Self-report scales

Study 2 made use of the self-report scales described in Study 1. The internal consistencies in Study 2 were as follows: α = .91 for Universality subscale of the Spiritual Transcendence Scale, α = .78for the Brief State Humility Scale, α = .81 for the Intellectual Humility Scale, and α = .78for the Lack of Intellectual Overconfidence subscale of the CIHS.

Participants, design, and procedure

Participant characteristics are described in . Surveys were completed online via Qualtrics. Using simple randomization, participants were assigned to one of 11 cognitive appraisals. Participants were asked to spend a few moments thinking about a time they experienced the assigned cognitive appraisal. Participants then wrote about the associated circumstances, details, and feelings. Next, participants rated on a scale of 0 to 10 how much they still believed what they described fit the assigned cognitive appraisal. Finally, participants completed counterbalanced measures of universality, GH, and two measures of IH.

As in Study 1, we deleted listwise participants who indicated they had not been attentive or honest in their survey responses (n = 9). No additional participants failed the attention check. We removed listwise participants who were outliers on a variable of interest according to the outlier labeling rule using a 2.2. multiplier (n = 2).

Results

Comparison of sanctification appraisals to contrasting appraisals

T-tests were used to examine whether participants assigned to a sanctification appraisal (n = 208) would express higher levels of universality, GH, and IH than participants assigned to a contrasting appraisal (n = 182). Homogeneity of variance between the groups was met in all cases except for GH. Following the induction, the two groups did not differ significantly in universality, t(388) = −.77, p (2-tailed) = .440, Cohen’s d = −.08, GH (equal variances not assumed), t(357.19) = .50, p (2-tailed) = .617, Cohen’s d = .05, or IH as assessed by the Intellectual Humility Scale, t(388) = .57, p (2-tailed) = .572, Cohen’s d = .06. However, the two groups differed in IH as assessed by the Lack of Intellectual Overconfidence subscale of the CIHS, t(388) = 2.13, p (2-tailed) = .034, Cohen’s d = .22, with those receiving a sanctification appraisal induction (M = 20.84, SD = 3.85) reporting higher levels of IH than those receiving a contrasting appraisal induction (M = 19.97, SD = 4.26).

Comparison of cognitive appraisals

We conducted pre-registered exploratory analyses to examine if particular sanctification appraisals (sacred, divine, miraculous, spiritual, holy, blessed) would elicit more universality, GH, or IH than other appraisals. Analyses of variance indicated no group differences between particular sanctification appraisals for universality, GH, or IH (p ranging from .13 to .96).

Discussion

Similar to Study 1, the most interesting findings of Study 2 relate to IH. Consistent with our hypotheses, sanctification appraisals elicited IH to a greater extent than contrasting appraisals. This supports the path from cognitive appraisals of sanctification to IH (). Our findings parallel theories about awe being a response to vastness, which requires cognitive accommodation of a stimulus that defies one’s existing mental frameworks. Similarly, phenomena that are considered sacred are experienced as ineffable and, to a certain extent, unknowable. Thus, encounters with sacredness might increase awareness that one’s mental capacity is limited in its ability to grasp something holy or pure. Further, focusing on something sacred may offer psychological distance from one’s more mundane concerns, which has been shown to facilitate IH (Grossmann et al., Citation2021). In addition, for those who experience a personal relationship with that which is perceived sacred, sanctification appraisals can offer a sense of relational safety, for example, by being reminded of the love or care of a deity, thereby creating a safe space in which to let down one’s defenses and acknowledge one’s intellectual limits (compare to Reis et al., Citation2018). For theists, this may look like the willingness to express an intellectual dependence on an all-knowing God (Hill, Citation2021).

However, inducing sanctification appraisals significantly predicted self-reported IH only for one of the two employed IH scales. Interestingly, the scale with significant links was the less robust outcome of the two IH scales in relation to STPE in Study 1. This highlights a recognized conundrum that within the 15 or more published scales of IH, there are variations in operational definitions (Porter et al., Citation2022). Although the two (sub)scales used in the current research were selected for their similarities to be able to replicate the findings across multiple measures, the scales still performed differently.

Contrary to hypotheses, sanctification appraisals were not predictive of universality or GH. Given that we only evaluated universality as the inter-connectedness aspect of self-transcendence, it would be valuable to assess the self-loss aspect of self-transcendence in relation to sanctification. We are not aware of previous empirical examinations of the links between sanctification appraisals and humility, however, we had a theoretical basis for expecting them to be related. It would be worth exploring this relationship further with alternative ways of assessing or inducting sanctification. In addition, similar hypotheses might be explored in religious samples, rather than the general population.

Study 3: using nature to elicit universality, general humility, and intellectual humility

In Studies 1 and 2, we induced STPE and sanctification appraisals to examine how this related to self-transcendent beliefs (universalism), GH, and IH. In Study 3, we examined if nature could be used to elicit STPE, sanctification appraisals, universalism, GH and IH. We also explored whether the degree to which people experienced GH and IH in nature might be dependent on the extent to which they experienced STPE, sanctification appraisals, and universalism.

The experience of these variables of interest in nature is not uniform, but depends on an interaction between characteristics of the nature setting, characteristics of the person, and the types of activities engaged in (Davis & Gatersleben, Citation2013; Heintzman, Citation2009; Williams & Harvey, Citation2001). Distinctions have been found between extraordinary nature (e.g. cliffs, waterfalls, mountains, canyons) and mundane or manicured nature (e.g. parks, gardens, waterfronts). Although both types of nature elicit self-transcendence, comparative studies have indicated that extraordinary nature elicits more awe and makes people feel smaller and more humble than mundane nature (Joye & Bolderdijk, Citation2015). Extraordinary nature also elicits more surprise than mundane nature or control images (Joye & Bolderdijk, Citation2015). Given that surprise occurs when an expectation has been violated, this may provide underpinnings for extraordinary nature to elicit IH. In addition, people’s tendency to form sanctification appraisals is predictive of self-transcendent experience in nature (Heintzman, Citation2009). The characteristics of extraordinary nature overlap with the features of nature that have been identified to elicit spiritual connotations for people (Ashley, Citation2007). Research has further indicated that foot travel in nature, particularly in solitude, contributes to spiritual meaning-making (Heintzman, Citation2009).

Based om this literature, we exposed individuals to either extraordinary nature (a state park), limited mundane nature (an urban setting with manicured nature), or an indoor setting with no nature. To extend the amount of nature exposure and to incorporate a walking element, we had participants complete measures in their assigned setting and again after spending 20 minutes walking in the assigned setting. We hypothesized walking in extraordinary nature compared to walking in both other environments would result in more sanctification of one’s surroundings and sanctification of the walk itself as well as increases in STPE, universality, GH, and IH. We also hypothesized the differences in GH and IH between walking environments would be moderated by the extent to which participants sanctify nature and experienced STPE and universality during the walk. The moderation hypotheses are an undisplayed extension to the basic model in .

Method

Participants, design, and procedure

Participant characteristics are described in . Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions to spend time in extraordinary nature in a state park (n = 63), limited manicured (mundane) nature in an urban area (n = 66), or indoors (n = 59). Within their assigned environments, participants completed a battery of self-report measures described in this paper, as well as scales of cognition, affect, and body image that were of interest to other projects. After completing measures, participants walked with moderate effort for 20 minutes in their assigned environments without making them out of breath (a 12–13 on the Borg scale with the example of ‘walking through the grocery store or other activities that require some effort but not enough to speed up your breathing’).

Based on the rationale provided in Study 1, we deleted listwise participants who indicated they had not been attentive or honest in their survey responses (n = 4) and participants who failed an attention check during the survey (n = 12). We also removed one participant who was an outlier on a variable of interest according to the outlier labeling rule using a 2.2. multiplier.

Materials

Self-transcendent positive emotions

Participants rated on a 5-point scale from not at all or very slightly to extremely the extent to which they were experiencing seven STPE: in awe, sense of wonder, grateful, love, admiration, attentive, and elevated. Items were administered twice in each condition, once before and once after the walk and were summed for each time point (T1 α = .82; T2 α = .89).

Appraisals of sanctification

We assessed both theistic (God-centered) and non-theistic (not referring to a deity) ways in which people formed cognitive appraisals of sacredness. Prior to the walk, we used the Manifestation of God Scale (Mahoney et al., Citation1999) to assess the degree to which participants perceived nature to be a manifestation of God, e.g. ‘God is present in nature’ (9 items; α = .96). Following the walk, we used the same scale to assess the degree to which participant sanctified the walk (5 items; α = .97). A sample item is, ‘I sensed God’s presence during my walk’. Following the walk, we also made use of the Sacred Adjectives Scale (Mahoney et al., Citation2003) to assess non-theistic sanctification of the walk and their surroundings for which participants rated the extent to which they had experienced 11 sacred qualities, such as ‘holy’, ‘sacred’, ‘spiritual’, ‘blessed’, and ‘miraculous’ about the walk (α = .96) and their surroundings during the walk (α = .98).

Universality, general humility, and intellectual humility

Three scales described in Study 1 were administered twice in each condition, once before and once after the walk: the Universality subscale of the Spiritual Transcendence Scale (T1 α = .84; T2 α = .89), the Brief State Humility Scale (T1 α = .68; T2 α = .72), and the Lack of Intellectual Overconfidence subscale of the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale (T1 α = .69; T2 α = .80).

Results

Preliminary analyses

We conducted analyses to examine whether there were any systematic differences in demographics between the randomly assigned experimental groups. Chi Square analyses confirmed there were no differences between the groups in gender, X2 (4, N = 187) = 1.72, p = .79 or religious identification, X2 (18, N = 187) = 24.27, p = .15. Analyses of variance indicated there were also no differences between the groups in age, household income, levels of religiousness or spirituality, or frequency of public or private religious activities, with p-values ranging from .166 to .995.

Using nature to elicit self-transcendent positive emotions, universality, and humility

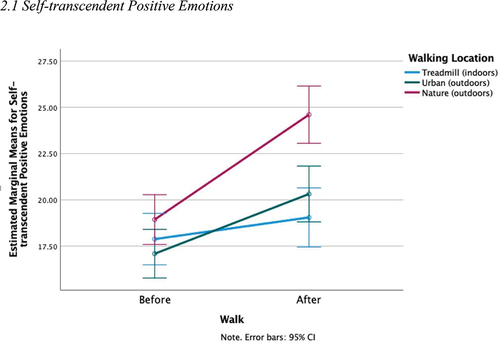

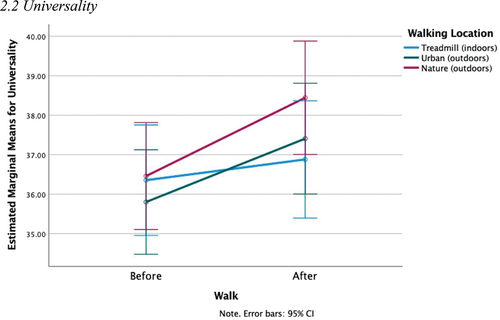

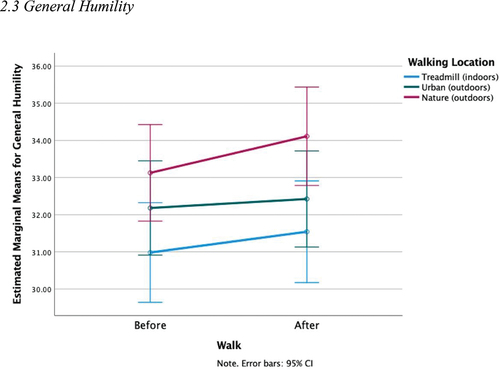

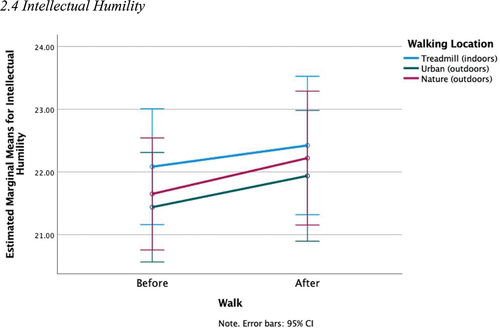

To examine whether the three study environments elicited differing levels of STPE, universality, GH, or IH initially or over the course of a 20-minute walk, we conducted 2 × repeated measures mixed ANOVAs with the between-subjects factor of environment (indoors, urban, and nature) and the within-subjects factor of time (before and after the walk). In all cases, we conducted post-hoc pairwise comparisons of the estimated marginal means and errors. We used Bonferroni to correct for multiple comparisons. To evaluate significant interactions, we offer a descriptive interpretation of the estimated marginal means and errors with 95% CIs. We consider groups to differ from one another when the 95% CI of the estimated marginal means overlap for less than 25% of the full CI length (Garofalo et al., Citation2022). To evaluate whether participants within each condition changed in the variables of interest from before to after the walk, we calculated 95% confidence intervals of the paired differences. The results are displayed in .

Table 2. Estimated marginal means of variables of interest (N = 188).

Self-transcendent positive emotions

For STPE, there was a significant main effect for environment, F(2, 185) = 7.49, p = .001, ηp2 = .075. Being in nature was associated with more STPE than being in an urban setting (p = .004) or indoors (p = .002). There was no difference in STPE between those in the urban outdoors and those indoors (p = 1.00). There was a significant main effect for walking, F(1, 185) = 94.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .338, with a higher estimated marginal mean for STPE following the walk than before the walk (p < .001). There was a significant interaction between environment and walking, F(2, 185) = 13.84, p < .001, ηp2 = .130. and illustrate that the groups in the three environments did not differ from each other in their levels of STPE at the initial assessment. Over the course of the walk, both those in nature and the urban setting increased in STPE, but only those who spent time walking in extraordinary nature experienced an increase in STPE substantial enough to differentiate their levels of STPE following the walk from those in the other two environments.

Universality

For universality, there was no main effect for environment, F(2, 185) = .50, p = .608, ηp2 = .005. There was a significant effect for walking, F(1, 185) = 45.31, p < .001, ηp2 = .197, with a higher estimated marginal mean for universality following the walk than before the walk (p < .001). In addition, there was a significant interaction between environment and walking, F(2, 185) = 4.46, p = .013, ηp2 = .046. and illustrate both those in the nature and urban conditions increased in universality over the course of the walk, yet none of the three environments resulted in higher levels of universality compared to the other environments.

General humility

For GH, there was a significant main effect for environment, F(2, 185) = 3.49, p = .032, ηp2 = .036. Being in nature was associated with significantly more GH than being indoors (p = .028). However, being in nature was not associated with significantly different levels of humility than the urban outdoors (p = .396), nor did the urban outdoors differentiate from indoors (p = .724). There was also a significant main effect for walking, F(1, 185) = 4.85, p = .029, ηp2 = .026, with a slightly higher estimated marginal mean for GH following the walk than before (p = .029). There was no significant interaction between environment and walking, F(2, 185) = .65, p = .523, ηp2 = .007, see and .

Intellectual humility

For IH, there was only a main effect for walking, F(2, 185) = 6.72, p = .010, ηp2 = .035. IH was higher following the walk than before (p = .010). There was no main effect for environment, F(2, 185) = .35, p = .703, ηp2 = .004, nor an interaction between environment and walking, F(2, 185) = .139, p = .870, ηp2 = .002, see and .

Using nature to elicit cognitive appraisals of sanctification

To examine whether walking in nature elicited sanctification appraisals more so than walking in an urban setting or on an indoor treadmill, we conducted one-way analyses of variance to evaluate the effects of walking environment on sanctification of one’s surroundings during the walk and sanctification of the walk.

Sanctification of surroundings

There was a significant effect of walking environment on sanctification of one’s surroundings during the walk (assessed post-walk; see ). Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni adjustment indicated all three walking environments differed significantly from one another at p < .001. The highest level of sanctification of surroundings was observed among those walking in nature, followed by those walking in the urban outdoors, followed by those walking indoors.

Table 3. Cognitive appraisals of sanctification after walk by walking environment (N = 188).

Sanctification of walk

Sanctification of the walk was assessed following the walk with both theocentric and nontheistic measures. For both types of assessment, there was a significant effect of walking environment on sanctification of the walk (see ). Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni adjustment indicated that for both nontheistic sanctification (endorsing sacred qualities of the walk) and theistic sanctification (experiencing manifestations of God in the walk), all three walking environments differed significantly from one another (p-values ranging from .011 to < .001), with those walking in nature reporting the highest levels of sanctification of the walk, followed by those walking in the urban outdoors, followed by those walking indoors.

Sanctification of surroundings, self-transcendent positive emotions, and universality as moderators of links between walking environment and general and intellectual humility

We proposed models in which the extent to which individuals sanctify nature and experience STPE and universality might moderate links between nature in one’s environment and levels of GH and IH experienced following the walk. Given our repeated measures ANOVAs did not indicate links between environment and IH, we only examined potential moderation effects for GH. In addition, since there were no interactions between environment and time, we examined post-walk measures where possible, as participants had spent the most time in each environment following the walk. We conducted two hierarchical regressions with the use of orthogonal contrasts of the environments. In the first regression we examined the hypothesis that walking in extraordinary nature would be associated with higher levels of GH than the urban or treadmill environments (coded as nature = 2, urban = −1, and treadmill = −1). We also added a comparison between the urban and treadmill environments (coded as urban = 1, treadmill = −1, and nature = 0). In a separate regression, we included direct comparisons between nature and urban environments (coded as nature = 1, urban = −1 and treadmill = 0) and between nature and treadmill environments (coded as nature = 1, treadmill = −1, and urban = 0). In each regression, we entered the orthogonal contrasts of the study environments in Step 1, the extent to which participants sanctify nature (assessed pre-walk) in Step 2, levels of STPE reported after the walk in Step 3, levels of universality reported after the walk in Step 4, interaction terms between the environment contrasts and sanctification of nature in Step 5, interaction terms between the environment contrasts and STPE in Step 6, and interaction terms between the environment contrasts and universality in Step 7.

The variables in the hierarchical regressions accounted for a significant proportion of variation in participants’ levels of GH following the walk, F[11, 176] = 1.92, p = .039. Consistent with our repeated measures ANOVAs, walking in nature resulted in higher GH compared to the other walking environments (B = .71, SE = .27, 95% CI = .17, 1.25, β = .19, p = .011), specifically in relation to walking on the treadmill based on the one-on-one environment contrasts (B = 1.15, SE = .56, 95% CI = .05, 2.25, β = .17, p = .041). However, this difference was not moderated by the extent to which participants sanctified nature, the degree of STPE experienced, or participants levels of universality. Universality was predictive of greater GH, regardless of walking environment (B = .20, SE = .08, 95% CI = .03, .36, β = .21, p = .019). Finally, sanctification of nature moderated links between walking in an urban setting versus walking on a treadmill and GH (B = .10, SE = .05, 95% CI = .00, .21, β = .14, p = .001), but we did not probe this interaction given that it was not meaningful to our hypotheses.

Discussion

Study 3 supported that nature is an environment offering encounters that result in STPE, appraisals of sanctification, and GH (). Substantial research indicates various forms of nature exposure (images, videos, in vivo) are associated with increased levels of awe (Ballew & Omoto, Citation2018; Joye & Bolderdijk, Citation2015; Piff et al., Citation2015; Shiota et al., Citation2007; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, Citation2012). Our research adds to the smaller body of work finding links between nature exposure and a broader range of STPE (Neill et al., Citation2018). In addition, the current work offers insight into the activity of walking in nature, which, consistent with our hypotheses, resulted in greater increases in STPE than walking in comparison environments.

Links between nature exposure and self-transcendence are well established. A common understanding of self-transcendent experience is that it involves both decreased self-salience and increased feelings of connectedness with beings and things outside of oneself. In the current work, we assessed universality, which is most reflective of connectedness. In partial support of our hypotheses, walking outdoors, both in extraordinary nature and in the mundane nature of an urban area resulted in increased universality over the course of the walk, in contrast to walking indoors, which did not result in increased universality. However, levels of universality were still not different between the groups after the walk. Perhaps longer walks or more frequent nature exposure would result in differentiated levels of universality. It would also be useful to assess diminutive aspects of self-transcendence, as this tends to be elicited by extraordinary nature where there is little sense of belonging in the natural environment (Williams & Harvey, Citation2001). This would have been most consistent with our state park condition, which contained compelling elements such as vast views of mountains, areas of dense trees, and a water stream. Connectedness, which we assessed via universality, may be more likely elicited by absorption or deep flow transcendence, which occurs in natural environments that are more open, familiar, and facilitate feelings of belonging (Ballew & Omoto, Citation2018; Davis & Gatersleben, Citation2013; Williams & Harvey, Citation2001).

As hypothesized, those walking in nature formed sanctification appraisals about their surroundings and the walk to a greater extent than those walking in an urban setting or indoors. This held for both theistic and nontheistic forms of sanctification. Sometimes religion and spirituality are studied detached from everyday activities. In contrast, the study of sanctification helps us understand how individuals infuse everyday experiences (such as nature and walks) with a sense of sacredness.

Given our interest in IH, it would be fascinating to examine in future research whether sanctification of one’s intellect might moderate links between nature exposure and IH. We theorized that being immersed in the majesty of a natural environment can raise awareness about one’s limitations to grasp and understand the workings of the natural world. If individuals view their intellect as God-given or otherwise sacred, this may minimize defensiveness about cognitive limitations and errors (see also Hill, Citation2021).

In partial support of our hypotheses, being in nature was associated with significantly more GH than being indoors, regardless of the timing (before or after the walk). This is consistent with previous findings that being exposed to potent, novel, and awe-inspiring nature results in feelings of insignificance and humility (Williams & Harvey, Citation2001). Contrary to our hypotheses, these links were not moderated by participants’ levels of STPE, universality, or sanctification of nature.

Also contrary to our hypotheses, being in nature did not elicit higher levels of IH. We had theorized that exposure to visually complex, information rich, and incomprehensible natural environments would result in greater IH. It is possible our study location did not sufficiently represent such natural elements. In addition, our participants resided in a high nature-access area, meaning they may not have experienced enough novelty during the nature exposure to raise awareness of their intellectual fallibility (see novelty as a suggested element for increased humility in exposure to forests, Williams & Harvey, Citation2001).

For IH, there was a main effect for walking, with IH being higher following the walk than before, regardless of environment. We cannot draw conclusions about this without a non-walking comparison. However, it is possible participants engaged in reflection during the walk, as they were tasked with walking without cellphones, music, or other regular distractions. It may be useful to examine in future research whether times of general reflection, meditation, or physical activity result in higher levels of IH.

Finally, we have noted that traits of the person are relevant to the person-environment transaction of transcendence in nature. It would be useful for future research to examine the role of other characteristics of participants, such as socio-demographic characteristics, personal history, and spiritual tradition or background.

General Discussion

Others have noted that excessive self-interest is, in fact, not in the interest of the self (Bauer & Wayment, Citation2008). The current work adds to findings about how individuals might transcend a focus on the self and how this relates to GH and IH. Given the personal, intellectual, and interpersonal benefits of GH and IH noted in the literature, there is reason to believe that finding ways to encourage these qualities has the potential to improve lives, relationships, and communities. Interventions to promote GH have been underway for some time and as insight into IH unfolds, there is budding research focused on developing strategies to promote IH. The current work adds to the small but growing body of research demonstrating self-transcendent experiences have relevance for increasing GH (e.g. Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018) and IH (Kim et al., Citation2023). The current work expands from the predominant previous focus on awe to include other STPE and shifts from a previous emphasis on the cognitive appraisal of vastness associated with awe to explore sanctification appraisals. As such, the current work examined both affective (STPE) and cognitive (sanctification appraisals) avenues to GH and IH and explored nature as a possible elicitor of these qualities of interest.

Although previous research has found links between awe and GH (Saroglou et al., Citation2008; Stellar et al., Citation2018), the current research did not observe links between a broader range of experimentally induced STPE and GH. However, we observed links between experimentally induced STPE and IH (Study 1), which is a new addition to the literature. This is consistent with the broaden aspect of the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, that positive emotions broaden people’s attention and increase people’s range of perceptions (Fredrickson et al., Citation2008). This is likely intensified in the case of STPE, where individuals may experience curiosity, interest, and a need to engage in cognitive accommodation and form new meaning to make sense of particular types of encounters. STPE occur in contexts in which individuals are exposed to instances of greatness, beauty, or sacredness that are foreign and difficult to comprehend. It seems exposure to the experiences that elicit STPE also raise awareness that one’s intellect is limited and that what one can understand about important topics is incomplete.

Given all the research attention devoted to awe, it is interesting that our comparison of STPEs indicated gratitude stood out as eliciting more IH than some other self-transcendent (harmony) and non-self-transcendent (happiness) emotions (Study 1). Pervious links have been observed between gratitude and both GH (Kruse et al., Citation2017) and IH (Krumrei-Mancuso, Citation2017). Gratitude promotes humility because it acknowledges the value and knowledge others offer and therefore puts one’s own strengths, contributions, and knowledge in perspective. It is not possible to be simultaneously grateful and take credit (Kruse et al., Citation2014).

To our knowledge, previous research has not examined links between experimentally induced sanctification and GH or IH. Like STPE, sanctification appraisals were associated with higher levels of IH but not higher levels of GH (Study 2). This elucidates how encounters with sacredness in everyday life might increase IH in previously unexplored ways. The current findings bring attention to sanctification appraisals functioning similarly to uncertainty appraisals, which have been shown to change people’s processes of thinking to be more thorough and complex (Tiedens & Linton, Citation2001). Aspects of life perceived as sacred are likely considered mysterious and incomprehensible. These elements might raise awareness of the limits to one’s knowledge and understanding, thereby promoting IH. To the extent that sacredness is simultaneously viewed as positive in various ways (e.g. beautiful, magnificent, loving), this is likely to promotes the ability to appropriately and non-defensively attend and respond to one’s intellectual limitations.

Given that experimentally induced STPE and sanctification appraisals resulted in higher levels of IH (Study 1 and 2, respectively), it was surprising that nature exposure, which resulted in both STPE and sanctification appraisals, was associated with greater GH, but not greater IH (Study 3).

Theoretically, we expect reinforcing effects between STPE and sanctification appraisals that extend beyond eliciting events, such as nature exposure, to future encounters in a person’s environment. Given the current findings, this might drive even greater GH over time following nature exposure.

By examining sanctification appraisals in everyday experiences and in relation to nature, the current work advances the study of embodied spirituality in contrast to the study of spiritual practices based on detachment from everyday experience (see also Naor & Mayseless, Citation2020).

Finally, although much of the literature discusses GH and IH as traits, the current research adds to recent studies emphasizing GH and IH also function as dynamic states that shift in response to emotions, cognitions, and environmental contexts (e.g. Kruse et al., Citation2017; Stellar et al., Citation2018; Zachry et al., Citation2018). In this work we examined momentary emotions and cognitions elicited by experimental inductions. However, appraisal tendency processes also apply to dispositional emotions. Therefore, it would be useful to further examine GH and IH among people dispositionally prone to experience self-transcendence. This line of work deserves more attention, given the recent discovery that self-transcendent states are associated with a greater willingness to improve one’s IH (Kim et al. (Citation2023). Thus, being able to cultivate self-transcendence may be key to addressing one of the bigger challenges to cultivating GH and IH – the issue of motivation.

Author contributions

EKM, JT, and JH designed the study and collected the data. EKM conceptualized the theoretical model, conducted analyses, and wrote the manuscript. JT and JH reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Geolocation information for Study 3 includes

Solstice Canyon State Park, CA, USA (34.037528°N, 118.747472°W), Calabasas, CA, USA (34.139210°N, 118.708009°W), and Pepperdine University in Malibu, CA, USA (34.039174°N, 118.708140°W).

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Materials and Preregistered. The materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.13190.

Disclosure statement

We have no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

The datasets that support the reported findings are freely available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Hypothesis 4 was cut from this paper due to space constraints.

References

- Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). Functions of positive emotions: Gratitude as a motivator of self-improvement and positive change. Emotion Review, 9(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916669596

- Ashley, P. (2007). Toward an understanding and definition of wilderness spirituality. Australian Geographer, 38(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180601175865

- Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., Chen, S., Gordon, A. M., Stellar, J. E., McNeil, G. D., Peng, K., & Keltner, D. (2017). Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: Universals and cultural variations in the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000087

- Ballew, M. T., & Omoto, A. M. (2018). Absorption: How nature experiences promote awe and other positive emotions. Ecopsychology, 10(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2017.0044

- Bauer, J. J., & Wayment, H. A. (2008). The psychology of the quiet ego. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending self-interest (pp. 7–19). APA Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/11771-001

- Bowes, S. M., Blanchard, M. C., Costello, T. H., Abramowitz, A. I., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Intellectual humility and between-party animus: Implications for affective polarization in two community samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 88, 103992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103992

- Bowes, S. M., Costello, T. H., Lee, C., McElroy-Heltzel, S., Davis, D. E., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2022). Stepping outside the echo chamber: Is intellectual humility associated with less political myside bias? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(1), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167221997619

- Bowes, S. M., Costello, T. H., Ma, W., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2021). Looking under the tinfoil hat: Clarifying the personological and psychopathological correlates of conspiracy beliefs. Journal of Personality, 89(3), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12588

- Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., Gonzaga, G. C., & Goetz, J. L. (2013). What is shared, what is different? Core relational themes and expressive displays of eight positive emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 27(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.683852

- Cao, Y., & Li, H. (2023). Everything has a limit: How intellectual humility lowers the preference for naturalness as reflected in drug choice. Social Science & Medicine, 317(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115625

- Castelo, N., White, K., & Goode, M. R. (2021). Nature promotes self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101639

- Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). Humble beginnings: Current trends, state perspectives, and humility hallmarks. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(11), 819–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12069

- Davis, N., & Gatersleben, B. (2013). Transcendent experiences in wild and manicured settings: The influence of the trait ‘connectedness to nature. Ecopsychology, 5(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2013.0016

- Deffler, S. A., Leary, M. R., & Hoyle, R. H. (2016). Knowing what you know: Intellectual humility and judgments of recognition memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.016

- Fetterman, A. K., Muscanell, N. L., Wu, D., & Sassenberg, K. (2022). When you are wrong on facebook, just admit it: Wrongness admission leads to better interpersonal impressions on social media. Social Psychology, 53(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000473

- Fredrickson, B. (2009). Positivity. Three Rivers Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262

- Garofalo, S., Giovagnoli, S., Orsoni, M., Starita, F., Benassi, M., & Evans, R. (2022). Interaction effect: Are you doing the right thing? PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0271668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271668

- Grossmann, I., Dorfman, A., Oakes, H., Santos, H. C., Vohs, K. D., & Scholer, A. A. (2021). Training for wisdom: The distanced-self-reflection diary method. Psychological Science, 32(3), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620969170

- Heintzman, P. (2009). Nature-based recreation and spirituality: A complex relationship. Leisure Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 32(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400903430897

- Hill, P. C. (2021). Intellectual humility in the psychology of religion and spirituality. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2021.1916242

- Hodge, A. S., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, D. E., & McElroy-Heltzel, S. E. (2021). Political humility: Engaging others with different political perspectives. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(4), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1752784

- Johnson, B. (2002). On the spiritual benefits of wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness, 8(3), 28–32. https://issuu.com/ijwilderness/docs/vol-08.no-3.dec-02

- Johnson, K. J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2005). ‘We all look the same to me’: Positive emotions eliminate the own-Race Bias in face recognition. Psychological Science, 16(11), 875 881. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01631.x

- Joye, Y., & Bolderdijk, J. W. (2015). An exploratory study into the effects of extraordinary nature on emotions, mood, and prosociality. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01577

- Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

- Kim, Y., Nusbaum, H. C., & Yang, F. (2023). Going beyond ourselves: The role of self transcendent experiences in wisdom. Cognition & Emotion, 37(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2149473

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. (2017). Intellectual humility and prosocial values: Direct and mediated effects. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1167938

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., Haggard, M. C., LaBouff, J. P., & Rowatt, W. C. (2020). Links between intellectual humility and acquiring knowledge. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1579359

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Newman, B. (2020). Intellectual humility in the sociopolitical domain. Self and Identity, 19(8), 989–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2020.1714711

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Newman, B. (2021). Sociopolitical intellectual humility as a predictor of political attitudes and behavioral intentions. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 9(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.5553

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2016). The development and validation of the Comprehensive intellectual humility scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1068174

- Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). State humility: Measurement, conceptual validation, and intrapersonal processes. Self and Identity, 16(4), 399–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1267662

- Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., Ruberton, P. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). An upward spiral between gratitude and humility. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(7), 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614534700

- Leary, M. R., Diebels, K. J., Davisson, E. K., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., Isherwood, J. C., Raimi, K. T., Deffler, S. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (2017). Cognitive and interpersonal features of intellectual humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(6), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217697695

- Lerner, J. S., & Keltner, D. (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402763

- Mahoney, A., Pargament, K. I., Jewell, T., Swank, A. B., Scott, E., Emery, E., & Rye, M. (1999). Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marital functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 13(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.321

- Mahoney, A., Wong, S., Pomerleau, J. M., & Pargament, K. I. (2022). Sanctification of diverse aspects of life and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of studies from 1999 to 2019. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 14(4), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000354

- McDonald, J. E., Olson, J. R., Goddard, H. W., & Marshall, J. P. (2018). Impact of self transcendent and self-enhancement values on compassion, humility, and positivity in marital relationships. Counseling and Values, 63(2), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12088

- McDonald, M., Wearing, S., & Ponting, J. (2009). The nature of peak experience in wilderness. The Humanistic Psychologist, 37(4), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873260701828912

- Naor, L., & Mayseless, O. (2020). The therapeutic value of experiencing spirituality in nature. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 7(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000204

- Neill, C., Gerard, J., & Arbuthnott, K. D. (2018). Nature contact and mood benefits: Contact duration and mood type. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(6), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1557242

- Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Ruberton, P. M., Chancellor, J., Cornick, J. E., Blascovich, J., Lyubomirsky, S., & Bastian, B. (2019). The proximal experience of awe. PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0216780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216780

- Piedmont, R. L. (1999). Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality, 67(6), 985–1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00080

- Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018

- Porter, T., Baldwin, C. R., Warren, M. T., Murray, E. D., Bronk, K. C., Forgeard, M. J. C., Snow, N. E., & Jayawickreme, E. (2022). Clarifying the content of intellectual humility: A systematic review and integrative framework. Journal of Personality Assessment, 104(5), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2021.1975725

- Porter, T., Schumann, K., Selmeczy, D., & Trzesniewski, K. (2020). Intellectual humility predicts mastery behaviors when learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 80, 101888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101888

- Preston, J. L., & Shin, F. (2017). Spiritual experiences evoke awe through the small self in both religious and non-religious individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.11.006

- Raghunathan, R., & Trope, Y. (2002). Walking the tightrope between feeling good and being accurate: Mood as a resource in processing persuasive messages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 510–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.510

- Reis, H. T., Lee, K. Y., O’Keefe, S. D., & Clark, M. S. (2018). Perceived partner responsiveness promotes intellectual humility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.05.006

- Rouse, S. V. (2015). A reliability analysis of mechanical Turk data. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.004

- Saroglou, V., Buxant, C., & Tilquin, J. (2008). Positive emotions as leading to religion and spirituality. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801998737

- Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & Mossman, A. (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668

- Stanley, M. L., Sinclair, A. H., & Seli, P. (2020). Intellectual humility and perceptions of political opponents. Journal of Personality, 88(6), 1196–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12566

- Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A., Anderson, C. L., Piff, P. K., McNeil, G. D., & Keltner, D. (2018). Awe and humility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000109

- Tangney, J. P. (2000). Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings and directions for future research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.70

- Tiedens, L. Z., & Linton, S. (2001). Judgment under emotional certainty and uncertainty: The effects of specific emotions on information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 973–988. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.973

- Tong, E. M. W., Lum, D. J. K., Sasaki, E., & Yu, Z. (2019). Concurrent and temporal relationships between humility and emotional and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 20(5), 1343–1358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0002-3

- Van Cappelen, P., & Rime, B. (2013). Positive emotions and self-transcendence. In V. Saroglou (Ed.), Religion, personality, and social behavior (pp. 123–145). Psychology Press.

- Van Cappellen, P. (2017). Rethinking self-transcendent positive emotions and religion: Insights from psychological and biblical research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(3), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000101

- Van Cappellen, P., & Saroglou, V. (2012). Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025986

- Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, D. E., Hook, J. N., & Witvliet, C. V. (2019). Humility. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(5), 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419850153

- Williams, K., & Harvey, D. (2001). Transcendent experience in forest environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0204

- Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Allison, S. T. (2018). Heroic humility: What the science of humility can say to people raised on self-focus. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000079-000