ABSTRACT

How do play and playfulness contribute to adult mental health? We evaluated empirical evidence from 20 psychological interventions through a lens emphasizing playfulness in participants and playing processes as a putative change agent. We found (1) preliminary evidence supporting play as a causal agent of positive changes in adult mental health, likely via two mechanisms—as a mediator and as a medium, and (2) limited, unclear evidence surrounding the moderating effect of participant playfulness on intervention effectiveness. Our findings highlight the need for more rigorous quantitative assessment of play-related processes and health outcomes, and a clearer trait-state distinction when examining playfulness as an intervention outcome. We call for greater theoretical integration and a more holistic, developmentally-sensitive approach, emphasizing understanding boundary-crossing change mechanisms to harness play’s transformative, therapeutic power for improving adult health and wellbeing.

Introduction

Adult play and playfulness have received increasing attention over the past half century. While the understanding of what drives and constitutes play continues to defy clear consensus (Sutton-Smith, Citation2009), cumulative empirical evidence supports the potential positive role of play and playfulness in promoting human health and wellbeing. Specifically, correlational studies have linked adult play or playfulness to higher levels of performances and functioning, including work productivity (Martocchio & Webster, Citation1992), creative performance (e.g., divergent thinking) and innovative behaviors (Bateson & Nettle, Citation2014; Felsman et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2021; Nisula & Kianto, Citation2018; Tegano, Citation1990), academic achievement (Proyer, Citation2011), ability to entertain the self (Shen et al., Citation2014b), flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1981, Citation2014), stress coping and resilience (Chang et al., Citation2016; Qian & Yarnal, Citation2011), and overall adaptability (Shen et al., Citation2017). Other studies have documented positive associations between adult playfulness and different aspects of health and wellbeing, including physical fitness (Proyer et al., Citation2018), positive emotions and affective wellbeing (Felsman et al., Citation2020; Fredrickson, Citation2003; Fredrickson & Branigan, Citation2005), job satisfaction (Yu et al., Citation2007), and overall wellbeing and life satisfaction (Erez et al., Citation2016; Proyer, Citation2011, Citation2013; Yue et al., Citation2016).

These findings emerged from data collected from moderately diverse study samples involving young adults (e.g., Magnuson & Barnett, Citation2013; Shen et al., Citation2017), older adults (e.g., Chang et al., Citation2016; Erez et al., Citation2016), healthy individuals (e.g., Proyer, Citation2013) and clinically diagnosed patients (e.g., Frey, Citation2014; Versluys, Citation2017). They spanned a range of contexts including workplace and organizational settings (e.g., Glynn & Webster, Citation1993; Yu et al., Citation2007), educational and training settings (e.g., Martocchio & Webster, Citation1992; Proyer, Citation2011), human-technology interactions (e.g., Moon & Kim, Citation2001), intimate relationships (e.g., Aune & Wong, Citation2002; Betcher, Citation1981; Proyer, Citation2014), clinical settings (e.g., Schreiber-Willnow & Seidler, Citation2013), and different cultures (e.g., Erez et al., Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2012, Pang & Proyer, Citation2018; Shen et al., Citation2021; Yue et al., Citation2016). Although the majority of these findings remained descriptive and relied on cross-sectional data, the emergent pattern supports the potential therapeutic and wellbeing-enhancing effects of play and playfulness as likely transformative agents for positive changes in adult-centered psychological interventions.

Resonating with several scholars’ call to empirically establish play and playfulness’ functions and consequences in adulthood through rigorous research designs and causal analyses (Shen, Citation2020; Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015), the recent decade has witnessed a growing number of psychological interventions that incorporated play and/or playfulness in nonclinical (e.g. Proyer et al., Citation2020; West et al., Citation2017) and clinical settings (e.g., Dobbins et al., Citation2020; Keisari et al., Citation2020) to improve adult mental health outcomes. The former largely aligns with the principles of positive psychology (Seligman et al., Citation2005) by focusing on how play and playfulness may promote positive psychological functioning and optimal wellbeing (e.g., creativity and happiness). The latter often falls under the general framework of psychotherapy by focusing on (1) the therapeutic effect of the playing process as a context for overcoming psychological challenges, and/or (2) the ability to play as a desirable therapy outcome in itself (Winnicott, Citation1971).

Given the growing applications of play and playfulness in health-related psychological interventions for adults and different theorization of the roles of play and playfulness across existing studies, there is a great need for an integrative review to assess the current knowledge about how play and playfulness have been treated in existing interventions and the potentially diverse roles that they may serve in influencing mental health. Notably, several selective reviews have discussed the applications of play and playfulness in specific contexts such as intimate relationships (Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015), workplace (Petelczyc et al., Citation2018), and psychiatry (Berger et al., Citation2018). There are also books on clinical strategies and techniques for incorporating play in adult therapy (Frey, Citation2014; Schaefer, Citation2003; Tonkin & Whitaker, Citation2016). While these sources contributed context-specific insights and the technical know-how of integrating play in counseling practices, a systematic understanding remains to be desired of the various roles of adult play and playfulness in psychological interventions broadly and the extent to which these roles are supported by empirical evidence.

The present paper provides a timely integrative review to (1) address the above knowledge gaps by consolidating existing empirical evidence across different theoretical frameworks and (2) reveal emerging patterns and opportunities for integration through elucidating connections among seemingly disparate research streams. Given the diverse and sometimes contrasting ways in which play and playfulness have been defined and studied in children and adults, we first clarify the conceptualization of play and playfulness and the need for a theoretical lens that would consider their developmental characteristics in adulthood. This is followed by a brief review of the theoretical underpinnings of the play/playfulness-mental health connections contributed by two primary psychological research frameworks—positive psychology and psychotherapy. The main part of this paper presents insights generated by the authors during a systematic review of empirical studies that explicitly examined the playful quality of the playing process or player in health-related psychological interventions (Shen et al., Citation2023). Derived but separate from that systematic review, this paper reports a distinct, theory-informed interpretation of the primary data with a focus on the emerging themes about how play or playfulness has been examined as indicated by their role in various analytical models (e.g., as a mediating process, a moderator, or an outcome) and corresponding empirical evidence. The paper concludes with discussions of implications and promising future research directions for advancing adult play/playfulness-related psychological interventions toward an empirically supported cumulative science.

Conceptualization of play and playfulness: distinguishing state and trait

Distinguishing play and playfulness on the conceptual level is critical because it not only clarifies terminology use (or misuse), but also establishes conceptual clarity necessary for discerning the often-implicit definitions or assumptions about play and/or playfulness embedded in various studies.

In his classic cultural analysis of play, Dutch historian Johan Huizinga (Citation1955) characterized play as a ‘free activity’ that stands outside of ‘ordinary life,’ is simultaneously ‘not serious’ and utterly ‘absorbing,’ and connects with no material interest while being bounded by its own fixed rules. Play has been defined diversely since, including as a behavior or activity (Ablon, Citation2001), a behavioral orientation or psychological approach (Schwartzman, Citation1978), a subjective state of mind (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975), and personal attribute or predisposition (Ferland, Citation1997). More recent works, particularly those in psychology, reflect growing conceptual clarity by distinguishing between play as a behavior or activity and playfulness as an individual attribute that predisposes one to engage in play (e.g., Petelczyc et al., Citation2018; Shen et al., Citation2014a; Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015). The connections between the two concepts are further crystallized via the distinction between the playful state and playful trait. The former emphasizes the manifest state of being playful (e.g., playful behavioral or affective expression) that often varies from context to context; the latter focuses on the latent attribute of the player that remains relatively stable across time and settings (Moon & Kim, Citation2001; Shen, Citation2010).

Shen (Citation2020) integrates the concepts of play and play–fulness under a unifying interactionist model that (1) incorporates a third component—the environment in the form of psychologically meaningful situations that interact with different aspects of the playful trait, and (2) advocates studying play in context as a result of player–environment interactions. This model provides a potentially useful organizing framework for delineating the different roles that play or playfulness serve in psychological interventions, including (1) playful behavior as a process variable that mediates the effect of environmental conditions, leading to immediate or long-term outcomes, (2) playfulness as a moderator that modifies the effect of experimental and control conditions, and (3) play behavior or playfulness itself as a desirable intervention outcome. It is unclear to what extent existing literature has examined the different roles of play and playfulness in health-related psychological interventions for adults and what empirical evidence exists.

In this review, we adopt the tenets of Shen’s (Citation2020) interactionist framework by differentiating between play as a behavior or process and playfulness as a latent predisposition. We examine both aspects to facilitate an integrative analysis of the various ways in which play and playfulness may affect mental health outcomes in adult-centered psychological interventions.

Developmental characteristics of play in adulthood: the need to focus on the playful experiential quality

Understanding the differences between adults' play and children’s play helps inform a developmentally sensitive approach to studying play-related interventions. Play has been widely accepted as a natural and enjoyable context for delivering interventions targeting children (Gibson et al., Citation2021; Youell, Citation2008). As such, play-based interventions have seen longstanding applications in children and, to a lesser degree, in adolescents (Jensen et al., Citation2017), demonstrating efficacy in promoting a variety of play skills (Kent et al., Citation2020; Kuhaneck et al., Citation2020) and non-play outcomes (Bratton et al., Citation2005; Jensen et al., Citation2017; Lelanc & Ritchie, Citation2001; Lin & Bratton, Citation2015; Ray et al., Citation2015).

By contrast, play and playfulness in adulthood have been considered less socially acceptable, partly due to the common lay belief of play being the antithesis of work and productivity (Lieberman, Citation1977; Sutton-Smith, Citation2008). Research on adult play and playfulness started to gain traction only in recent decades in response to the growing multidisciplinary evidence of their positive associations with various aspects of health and performances in adulthood. The confluent understanding about play and playfulness’ essential role in optimal adult functioning and wellbeing echoes the dominant theme of extensive research on child play as a key mechanism and medium for physical, cognitive, socio-emotional development (Bratton & Ray, Citation2000; Jensen et al., Citation2017). Nonetheless, adult play and playfulness differ from their child counterpart in important ways, and a developmentally sensitive approach is required to examine their manifestations, mechanisms, and implications in interventional applications targeting adults (Colarusso, Citation1993; Shen et al., Citation2014a).

Specifically, as people age, play and playfulness increasingly manifest in social-cognitive forms that contrast the prevalent sensorimotor play in early childhood (Lieberman, Citation1977). The fluid and varied characteristics of adult play necessitate expanding attention from overt forms—a focus of behavioral observations that dominate child play studies—to less observable experiential qualities when studying play in adulthood. Increased attention to the latter would also respond to the highly permeable characteristic of adult play, which often crosses conventionally defined boundaries (e.g., those between work and leisure). Consistent with the key notion of play as mind, not matter (Piaget, Citation1962), the emphasis on subjective experiences further aligns with the long-standing proposition of examining ‘playful play’ in the broader psychology literature (e.g., Millar, Citation1968) and recent interest in distinguishing playful and non-playful play in other fields (e.g., gaming, Stenros, Citation2015). It helps preclude conceptual ambiguities associated with the overly broad use of ‘play’ as an umbrella concept for various voluntary and pleasant activities that may or may not be carried out playfully (Weisler & MCall, Citation1976). Notably, existing empirical studies trying to delineate outcomes associated with specific forms of adult play have reported mixed findings (e.g., inconsistent effects of teasing and playing games on personal and relational wellbeing, Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015), further suggesting potential limitations and lack of generalizability of form-based analyses.

In the context of psychological interventions, the form and structure of play may shape the dynamics of the playing process to a large degree (e.g., improv play and clay play differ significantly in how they engage the player’s body and physical interactions with other players or play materials). These mechanical characteristics, however, are not necessarily the best predictor of how play is invested or experienced by individual participants (e.g., both improv and clay play can elicit inner creativity and spontaneous self-expression), yet the latter is clinically decisive for understanding the transformation that occurs during play. In this study we emphasize the playful experiential quality (i.e., the playfulness of a behavior or process) as the key to understanding the role of play as a change agent in adult-centered interventions. This conceptual emphasis dictates the use of playfulness as a unifying theoretical lens to guide our literature search and interpretation, a notion we elaborate on in a later section.

Theoretical considerations about the play/Playfulness-wellbeing link

Many researchers have attempted to explain the links between play/playfulness and wellbeing. Relevant to the focus of this review are theoretical insights from two main psychological research frameworks, positive psychology and psychotherapy, synthesized below.

Continuing the tradition of humanistic psychology, positive psychology focuses on studying human flourishing and what contributes to it (e.g., character strengths that enable happy, fulfilling lives, Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004). Although play and playfulness are rarely referred to in positive psychology literature, Peter Grey (Citation2015) argued that, when looking ‘beyond the word to the concept,’ positive psychology is ‘largely about play’ as it investigates activities that are intrinsically motivated, internally controlled, and often creative and imaginative. The same set of qualities have been used to define play and elaborated in prominent positive psychology theories such as flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975), self-determination theory (SDT, Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, Citation2001, Citation2006). The concept of flow (and its less-known companion ‘micro-flow’), in particular, was initially crystallized from extensive interview data on a subset of deeply involved play experiences characterized by well-matched skills and challenges that lead to engrossing and optimal body-mind synchronization (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975). As another example, Ryan and Deci (Citation2000) proposed that autonomy and intrinsic motivation, which typically drives play, led to improved relationships, psychological wellbeing, resilience, and better performances, particularly those related to creativity and mental flexibility. Fredrickson (Citation2001, Citation2006) zooms in on positive affect, a frequent concomitant of play, and proposes that it broadens a person’s thought-action repertoire, thus enables flexible and novel behaving and, over time, builds positive resources such as physical health and psychological wellbeing.

Psychotherapy, on the other hand, has focused on the therapeutic aspects of play. Initiated by Anna Freud (Citation1928) and extended by early psychologists such as Erik Erikson (Citation1963), Virginia Axline (Citation1969), Melanie Klein (Citation1932), and Donald Winnicott (Citation1953), this strand of research has primarily focused on child play as a context that allows a child to project and deal with emotional and behavioral dilemmas encountered in the real world. More recently, play therapy has expanded to include child-centered therapy, prescriptive therapy, filial/family play therapy and other versions (see Gitlin-Weiner, Citation2006 for a review). Notably, while Winnicott’s work primarily focused on child development, he held play as equally important in adulthood and his ideas about play have greatly influenced the understanding of play’s role in therapeutic treatment of adults. Winnicott (Citation1971) emphasized that the internal, experiential process of playing, as opposed to the manifest forms or static content of play, holds the potential for the transformative experience that confers play’s therapeutic effects. He suggested that the process of playing provides a transitional space between the inner psychic reality and the external reality—a safe and secure space where individuals can freely explore and express thoughts and emotions. This connects them with their inner creativity, leading to true self-discovery and personal growth.

It is unclear to what extent ideas offered by different theoretical frameworks such as those reviewed here have been tested or incorporated in studies of play- or playfulness-related interventions for adults. We believe an integrative review, unconstrained by a single theoretical approach, has the potential to shed light. This includes revealing connections between studies adopting different frameworks and generating useful insights that transcend theoretical boundaries.

Search strategy and sources of data

Literature search strategy

The balance of this paper presents an integrative synthesis of a body of literature identified through a systematic review project (Shen et al., Citation2023). As elaborated earlier, consistent with the tenets of the interactionist model for playfulness research (Shen, Citation2020), this review aims to provide a holistic understanding by considering both the personal attribute (i.e., the playfulness of participants or therapists) and behavioral aspect of play in psychological interventions for adults. With respect to the behavioral aspect, we believe playful engagement, or the playful experiential quality of the playing process holds the key to understanding play’s role as a change agent. Consistent with this vision, the literature search in Shen et al. (Citation2023) prioritized uncovering intervention studies that explicitly examined and discussed playfulness as a relevant individual attribute or aspect of participant experience. This is achieved by using ‘playful’ or ‘playfulness’, as opposed to ‘play’, as a key search term, supplemented by abstract and full-text screening to rule out studies that examined play but did not pay sufficient attention to its playful quality (indicated by intentional analysis and/or explicit discussions). Other search terms included psychological intervention, psychological treatment, or psychotherapy, excluding child, children, youth, and adolescent.

Importantly, the above strategy does not restrict the literature search to specific types of play. It allows including studies involving wide-ranging forms of play—some of which might not be labeled as play by the authors. Nonetheless, playful experience was part of the intervention and explicitly discussed in each paper. This is desirable because, as stated earlier, adult play is extremely varied and fluid, and may take specialized forms under different names (e.g., exergame, music therapy, leisure-time physical activity) . The search strategy also allows uncovering studies that did not include play as part of the intentional design but discussed playful experience as a naturally occurring component of the intervention. This is desirable too because it aligns with the viewpoint of psychotherapy as a form of playing between patient and therapist (Winnicott, Citation1971), regardless whether play activities are intentionally incorporated or not. In addition to explicit discussions of playfulness as a relevant individual attribute or aspect of participant experience, each study must also include a psychological treatment, at least one mental health outcome, and only adult participants (aged 18 and up). Only peer-reviewed empirical studies published in English were included.

In summary, playfulness provides a unifying theoretical lens with the potential to uncover and connect seemingly disparate bodies of work. The search strategy helped generate diverse studies that shared an attention to the playful quality of the intervention experience or participant—the putative therapeutic factor underlying wellbeing changes. Readers interested in defined forms of play, without a central concern on playfulness, can refer to other reviews, such as those on drama therapy (Feniger-Schaal & Orkibi, Citation2020), serious games (Lau et al., Citation2017), video games (Ceranoglu, Citation2010; Wilkinson et al., Citation2008), and recreation therapy (Flint et al., Citation2017).

Characteristics of primary studies

Following the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2015), the literature search included two waves conducted in December, 2020 and March 2022, respectively. Combined, the two searches identified 454 primary studies published in English peer-reviewed journals up to March 2022. After removing duplicates, title and abstract screening, and full-text assessment, 20 studies from 19 articles met the inclusion criteria and were retained. The included studies featured diverse research designs (e.g., randomized control trial or RCT, mixed-method cross-over design, non-randomized trials, single-group design, observations of naturalistic interventions, case study), participants (age = 19–91, healthy adults and patients experiencing different mental health issues), sample sizes (n = 1–631), settings (e.g., clinics, workplace and organizations, communities), and mental health out-comes (e.g., cognitive abilities, affective experiences, physiological and psychosis indicators, domain and overall wellbeing).

Notably, 40% of the interventions provided some type of psychotherapy. Mostly individual-based, these studies included (1) play as an intentional activity or naturally occurring element during therapy, (2) playfulness in clients or therapists as a predictor of intervention efficacy, or (3) client playfulness as an outcome itself. The remaining non-psychotherapy studies incorporated some type of playfulness-inducing activities, such as movement (e.g., physical activities, walking, exergames), art (e.g., clay/slip play), drama (e.g., improv, playback theater), or online positive psychology techniques (e.g., self-guided recall of playful episodes). All studies substantially discussed playfulness in behavior or persons as relevant to the intervention. Supplemental Table S1 briefly summarizes the research designs, participant characteristics, intervention activities, and mental health outcomes of primary studies. Readers can refer to Shen et al. (Citation2023) for more method details and findings, including a critical review of play/playfulness measurements used in these studies and an appraisal of methodological quality.

Findings

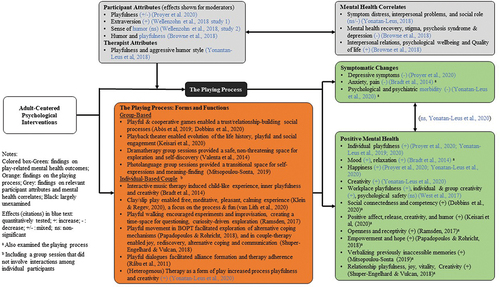

Three categories of evidence emerged from our review (), highlighting (1) the effects of play-related interventions on mental health outcomes (green box), (2) the characteristics of the playing process involved in intervention (orange box), and (3) the effect of trait playfulness and relevant personal attributes(grey box).

Figure 1. Integrative summary of findings on play and playfulness in adult-centered psychological interventions.

Causal effect on mental health outcomes: preliminary supportive evidence for play’s dual function

The first category includes 11 (55%) studies (green box in ) that contributed quantitative (n = 5, citations in blue text) and qualitative (n = 6, citations in regular black text) evidence on mental health outcomes as a result of play- or playfulness-related interventions.

Quantitative findings suggested interventions incorporating playful experiences, such as improv theater and music making, reduced depressive symptoms (small effect, Proyer et al., Citation2020), anxiety and pain (small-to-medium effect, Bradt et al., Citation2014). They also improved affects (large effect, Bradt et al., Citation2014), participant wellbeing and trait playfulness (small effect, Proyer et al., Citation2020), individual or team state playfulness and creativity in workplace (medium-to-large effect, West et al., Citation2017). Notably, two psychotherapy studies did not intentionally incorporate play activities. Instead, the therapy itself was considered a form of play between the therapist and client, wherein increased client playfulness was used as an indicator of improved mental health (Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Three studies did not examine the playing process (indicated by the black box, ). The effect sizes of mental health outcomes varied by intervention techniques and duration. Short, self-administered online interventions showed the smallest effects (e.g., Proyer et al., Citation2020). Larger effects were observed in studies targeting specific positive mental health outcomes (e.g., positive affect, creativity) as compared to those targeting broad markers of wellbeing (e.g., happiness) and symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety). However, these findings are based on a small number of studies, which precluded a meta-analysis and definitive, generalizable conclusions about effect size patterns.

Qualitative findings reported positive changes in a wider range of outcomes. These included social connectedness and competency (Dobbins et al., Citation2020), openness and receptivity (Ramsden, Citation2017), empowerment and hope (Papadopoulos & Röhricht, Citation2018), and relationship vitality (Shuper-Engelhard & Vulcan, Citation2018), among others. This set of studies also provided insights about the characteristics of the playing process during interventions. These are summarized next with other studies that examined the playing process.

Overall, we observed a dominant focus on positive aspects of mental health. These covered cognitive functions or skills (e.g., creativity, openness and receptivity, awareness and self-expression), affective experiences (e.g., joy, mood, positive affect), social competency (e.g., social connectedness, relationship playfulness) and overall wellbeing (e.g., happiness, empowerment, hope). Less attention went to play’s effect on negative symptoms, though available evidence supported play’s potential to reduce depressive symptoms, anxiety, and pain. Notably, one study examined both aspects of mental health and found symptomatic and positive health changes were largely independent (Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2020). Combined, these results provided preliminary empirical support of play (in its broad sense wherein psychotherapy is viewed as a form of play) as a causal agent leading to wide-ranging positive mental health changes. The findings highlight play’s dual function in enhancing positive functioning or wellbeing and, to a lesser degree, alleviating mental illnesses in adults.

Forms and functions of the playing process: qualitative evidence on mechanisms

The second category of findings includes 11 qualitative studies (orange box, ) that examined the characteristics of the playing process embedded in interventions either by design or as a naturally occurring element. An integrative form-function analysis revealed prominent effects of playful experience on fostering connections, self-expression, and exploration.

Firstly, playful interactions were found to facilitate social engagement and relationship building in almost all group-based interventions (Abós et al., Citation2019, Dobbins et al., Citation2020; Keisari et al., Citation2020; Valenta et al., Citation2014). In individual therapy, playful dialogues between therapist and client facilitated alliance formation (Råbu et al., Citation2011). Secondly, playful, dynamic experiences elicited through physical (e.g., body movement), visual (e.g., photo-language), or audio (e.g., music making) forms of play encouraged verbal (Mitsopoulou-Sonta, Citation2019) or non-verbal expressions (Shuper-Engelhard & Vulcan, Citation2018), while activating inner creativity and playfulness (Bradt et al., Citation2014). Thirdly, exploration emerged as a common experience shared by drama-, art-, and movement-based play, which provided a safe, non-threatening space for exploring inner reality (Keisari et al., Citation2020; Mitsopoulou-Sonta, Citation2019; Valenta et al., Citation2014), surrounding physical environment (Ramsden, Citation2017), or alternative coping mechanisms (Papadopoulos & Röhricht, Citation2018). Additionally, two studies examined specific functions associated with the therapeutic properties of play material, and found that clay/slip-play induced meditative, calming experiences (Klein et al., Citation2020) and a focus on the process and fun (Van Lith et al., Citation2020).

An integrative synthesis of the above evidence revealed two distinct paths through which play may initiate, facilitate, or strengthen specific therapeutic factors involved in an intervention:

The playing process serves as a change agent in itself and directly causes desired changes. For example, playful interactions in cooperative games and psychotherapy facilitated trust–building (Abós et al., Citation2019; Dobbins et al., Citation2020) and/or alliance formation (Råbu et al., Citation2011), contributing to an increased sense of connection or better therapy outcomes. Additionally, the heightened playfulness, creativity, and positive emotions experienced during play (e.g., music making) also directly build resilience (e.g., Bradt et al., Citation2014).

The playing process serves as a medium or con-text that provides a safe and inviting space for other key processes to take place, which in turn lead to positive changes. Drama or theater-based play, for example, provided a non-threatening, 'as if' space that encouraged self exploration and meaning finding through ‘embodied expression’ (Valenta et al., Citation2014), which fostered increased self-awareness and evolved understanding of life events toward self-discovery (Keisari et al., Citation2020).

Importantly, the above two mechanisms often intertwined organically as multiple processes tended to occur simultaneously and interact symbiotically during the extremely fluid playing process. Playful walking, for example, integrated cues for performative interruptions and transformed an otherwise ordinary habitual activity into a time and space for questioning and exploration. Meanwhile, the walking itself became a practice of experimentation and improvisation prompted by the encountering of the strange and unfamiliar. This rich process amounted to a transformative intellectual, psychological, and emotional experience leading to heightened openness and increased receptivity to change in participants (Ramsden, Citation2017). Similarly, traditional psychotherapy that incorporated body movement invited participants into a play space where they could safely explore alternative ways to communicate and/or cope, all the while engaging them in playful movement that directly elicited positive effects as a resilience resource to enable empowerment, hope, or connectedness (Papadopoulos & Röhricht, Citation2018; Shuper-Engelhard & Vulcan, Citation2018). Combined, these findings contributed rich insights about play as a potentially integrative and holistic pathway to positive mental health.

The effect of trait playfulness as a moderator: limited and mixed evidence

The third and smallest category of findings includes five quantitative studies (grey box, ) that examined playfulness and related personal characteristics (e.g., extraversion, sense of humor) in participants or therapists as moderators of intervention effectiveness or, in main effect-only models, as predictors of intervention outcomes. Mixed or non-significant findings were reported on the moderating effect of participant playfulness (Proyer et al., Citation2020) and a related quality—sense of humor (Wellenzohn et al., Citation2018, study 2). Extroverts were found to benefit more from humor-based interventions than introverts (Wellenzohn et al., Citation2018, study 1).

Two studies conducted exploratory regression analyses and examined the extent to which non-play-based psychotherapy outcomes were predicted by playfulness and humor as a character strength in clients or therapists. Client humor and playfulness were found to positively correlate with 6-month symptomatic improvement, psychological wellbeing, and interpersonal relations (Browne et al., Citation2018). On the therapist side, only aggressive humor style, not playfulness, predicted therapy effectiveness (Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2018).

Overall, the evidence on the moderating effect of the playful trait was limited and unclear. This indicates (1) insufficient support of participant/therapist playfulness as a boundary condition of intervention efficacy and (2) the possibility that play-related psychological interventions lead to similar outcomes for participants of different playfulness levels, regardless of the playfulness of therapists, if involved. On the other hand, the positive associations between participant playfulness and short-term wellbeing seemed to affirm playfulness’s main effect as a character strength contributing to positive functioning and health outcomes. This supports the propositions of positive psychology and converging correlational evidence summarized in Introduction.

Discussion

The overarching goal of this review is to synthesize existing empirical evidence to advance a comprehensive understanding of the roles of play and playfulness in adult-centered psychological interventions for mental health. This was achieved by analyzing a diverse set of 20 studies across a wide range of research designs and two main theoretical frameworks, through the unifying lens of playfulness as a personal or behavioral/experiential quality that transcends the manifest forms of play. Although modest in volume, the existing diverse applications of play- and playfulness-related psychological interventions for adults are instrumental in laying the groundwork for more extensive and detailed future studies. The empirical evidence and insights contributed by these studies speak to the versatility of play as a change agent, substantiating the long-standing understanding of (1) the fluidity of adult play and (2) converging theoretical insights about its role in fostering positive mental health changes and alleviating psychological distress. Several important findings are highlighted below, as are implications for future research.

The role of play and playfulness in adult-centered psychological intervention

We found largely consistent and complementary quantitative and qualitative evidence that supported play’s role as a causal agent of positive changes in adult mental health. However, we consider this evidence preliminary due to the overall small number of intervention studies and limited rigorous quantitative testing. More extensive research integrating quantitative health outcome assessments and strong experimental designs is needed to further validate and consolidate the causal links between play and various aspects of mental health. Notably, we observed significant variability in outcome effect sizes across different intervention modalities, precluding generalization about the efficacy of specific intervention techniques and designs. This invites future systematic testing to isolate and evaluate the likely different effects of intervention modality factors such as techniques, duration, and settings.

Based predominantly on qualitative evidence, this review sheds light on two distinct yet often intertwined paths linking the playing process—as a mediator or as a medium—with health outcomes. This elucidates a more accurate and empirically supported understanding of the mechanisms through which play facilitates mental health changes. The findings of certain common functions (e.g., building connections, encouraging exploration) across different forms of play attest to the value placed on the playful experiential quality as a critical therapeutic factor transcending play techniques. Notably, Yonatan-Leus et al. (Citation2020) made an exceptional contribution by quantitatively assessing temporal changes in playfulness and mental health during the intervention. Their cross-lagged model suggested that behavioral playfulness (a state measure) served as a central process variable preceding both symptomatic and non-symptomatic changes. Future research should incorporate quantitative assessment of key process variables to verify the occurrences of pertinent the-rapeutic factors embedded in the playing process. This line of research has the potential to help profile specific therapeutic factors associated with different play techniques and outcomes. When paired with contextual information such as presenting issues, this knowledge can help guide practitioners in identifying the most effective outcome-oriented intervention strategy toward a prescriptive approach.

Proyer et al. (Citation2020) contributed the sole analysis examining the role of participant playfulness as a moderator and reported mixed effects across conditions and outcomes. This may appear somewhat surprising given views of playfulness predisposing individuals to frame or reframe situations as fun, amusing, or entertaining (Barnett, Citation2007; Schaefer & Greenberg, Citation1997). The interactionist model also suggests situation perceptions can be shaped by playfulness and other individual attributes (Shen, Citation2020). However, these propositions emphasize playfulness’ influence on perceiving or redefining situations, implying a mediating effect of psychological situations rather than a moderating effect of the playful trait. We encourage more research to (1) empirically validate playfulness’ role in shaping situation perceptions and (2) examine its possible moderating effect, or the lack thereof, on intervention effectiveness. The latter can generate insights into the person × intervention fit (Schueller, Citation2010, Citation2014) and help ascertain playfulness as a relevant (or irrelevant) boundary condition.

Distinguishing trait and state playfulness

While an explicit trait-state distinction was often absent, most qualitative studies unambiguously considered play as a process (i.e., at the state level) separate from the playful trait when examining playful experience during intervention. The conceptual distinction between the playful state and trait was less clear in quantitative studies assessing playfulness as an outcome or process variable (e.g., Proyer et al., Citation2020; West et al., Citation2017; Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). A closer look at the playfulness measures used in these studies reveals marked differences in the target construct, making interpretation of related findings challenging due to unclear construct validity in some measures. West et al. (Citation2017), for example, examined both trait playfulness using a global measure (SMAP, Proyer, Citation2012) and state playfulness using an ad hoc single item on perceived playfulness in workplace. Yonatan-Leus et al. (Citation2020) assessed playful behavioral tendencies, a trait component under the traditional trait framework, as a process variable via an ad hoc 9-item measure with an unclear factor structure (shortened from the four-dimensional Playfulness Scale for Adults by Schaefer & Greenberg, Citation1997; aggregated score used nonetheless). Proyer et al. (Citation2020) used the OLIW-S (Proyer et al., Citation2020) with four sub-scales lacking an overarching playfulness factor (Barnett, Citation2018).

Regardless of measurement differences, various effect sizes—from small to large—have been reported on changes in playfulness (or related qualities as assessed by measures of dubious validity) as a result of interventions. Larger effects were associated with state measures and longer interventions (e.g., West et al., Citation2017; Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2020). While the limited evidence does not allow reliable and firm conclusions about the adaptability of state vs. trait playfulness, it is reasonable to expect state playfulness to be more malleable than trait playfulness in response to psychological interventions. Incremental changes in trait playfulness through long-term treatment are likely. This would align with interactionist propositions (Shen, Citation2020) and longitudinal findings on personality changes (Damian et al., Citation2019).

Two practical implications follow: (1) care is warranted when selecting a trait or state playfulness measurement that is conceptually consistent and psychometrically sound. This is low-hanging fruit for future research given that conceptual and measurement tools endorsing the playful trait-state distinction have become available in recent years (e.g., Shen, Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b). (2) When resources are limited, researchers are more likely to achieve desirable outcomes by targeting changes in state or behavioral playfulness.

Bridging theoretical frameworks

Across different study clusters, we observed mixed levels of references to relevant theories. With few exceptions (e.g., Dobbins et al., Citation2020; Proyer et al., Citation2020; West et al., Citation2017), most studies lacked explicit discussions of the conception of play and/or playfulness. This may be partially reconciled by our inclusive search strategy, which uncovered studies treating play/playfulness as a salient but not central construct, including interventions that generated playful experiences naturally rather than by design. Regardless whether play and playfulness are key constructs or not, researchers are encouraged to incorporate rich insights from recent considerable conceptual and measurement development on adult play and playfulness (e.g., Barnett, Citation2007; Glynn & Webster, Citation1992; Guitard et al., Citation2005; Masek & Stenros, Citation2021; O’Connell et al., Citation2000; Proyer, Citation2012; Proyer & Brauer, Citation2017; Schaefer & Greenberg, Citation1997; Shen, Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2021; Van Vleet & Feeney, Citation2015; Yu et al., Citation2003).

Many interventions provided practical insights supporting propositions, such as those on the play/playfulness-wellbeing link, from existing theories without explicitly referencing these theories. Nonetheless, a handful of studies discussed positive psychology theories (e.g., SDT, the broaden-and-build theory) to inform research hypotheses or design (e.g., Browne et al., Citation2018; Proyer et al., Citation2020; Wellenzohn et al., Citation2018). Another set under the traditional psychotherapy framework considered therapy a form of playing between therapist and patient, and assessed clients' ability to play as an indicator of mental health (e.g., Mitsopoulou-Sonta, Citation2019; Råbu et al., Citation2011). This aligns with the theoretical proposition about play first articulated by Winnicott (Citation1971):

Psychotherapy takes place in the overlap of two areas of playing, that of the patient and that of the therapist. Psychotherapy has to do with two people playing together. The corollary of this is that where playing is not possible then the work done by the therapist is directed towards bringing the patient from a state of not being able to play into a state of being able to play.

Despite rare cross-referencing, a shared understanding emerged of playfulness as a positive aspect of adult functioning and a change agent in psychological interventions. Studies differed in targeted populations (e.g., clinical adults in psychotherapy or healthy adults in positive psychology interventions) and corresponding focus on play’s therapeutic power or wellbeing-enhancing effect. Notably, a small number of psychotherapy studies incorporated positive psychology principles by focusing on playfulness and other attributes (e.g., humor, honesty, creativity) as character strengths with the potential to increase intervention effectiveness (Yonatan-Leus et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). One study that generally aligned with the positive psychology framework also examined symptomatic changes (Proyer et al., Citation2020). We applaud these integrative applications and encourage more cross-pollination between sub-disciplines and fields to advance a more holistic approach emphasizing transformative mechanisms that span theoretical boundaries.

Strength and Caveat

We carefully avoid using “play(–based) intervention” or “play therapy” given that not all studies systematically used play models or techniques despite examining playful experience or attribute. Our theory-informed search strategy intentionally prioritized uncovering evidence on playfulness as a personal or behavioral characteristic. This generated diverse play- or playfulness-related interventions. While synthesizing considerable diversity proved challenging, on balance we view this aspect as a strength. The playfulness lens supported a developmentally sensitive approach by focusing on the playful experiential quality as a clinically decisive therapeutic factor in adult-centered psychological interventions. It also enabled connecting disparate clusters of studies that contributed relevant empirical evidence and practical insights to inform a holistic understanding of play and playfulness’ health influences ().

Additionally, we acknowledge inconsistent viewpoints and practices related to play and humor, with works treating them synonymously (Browne et al., Citation2018) or as separate phenomena (Proyer et al., Citation2018; Wellenzohn et al., Citation2018). Distinguishing these concepts falls outside this paper’s scope but warrants clarity in future works.

Conclusion

Understanding the roles of play and playfulness in adult-centered psychological interventions has become increasingly important given growing evidence of their associations with wellbeing in adulthood. Through a unifying playfulness lens, this review integrates diverse empirical studies across different disciplinary approaches and research designs, shedding light on whether and how play and playfulness contribute to adult mental health improvement. Key findings include:

Preliminary evidence supports play as an effective change agent for improving adult mental health, particularly positive mental health outcomes.

Play facilitates changes via two intertwined mechanisms—serving as a mediator or providing space for other health-promoting processes.

Limited and unclear evidence surrounds the moderating effect of participant playfulness on intervention effectiveness.

A clearer trait-state distinction is needed when examining playfulness as an intervention outcome.

Integrating these findings, we identified a compelling need for more quantitative assessment of playing processes and health outcomes. Most importantly, this review calls for a more holistic approach that recognizes adult play's fluidity and shifts attention from play forms to playful quality as the key change agent. Findings encourage capitalizing play’s transformative power as a mechanism and context for overcoming psychological challenges and realizing positive mental health changes through empirically-supported interventions for adults.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/defaults/xk81jt69q

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/defaults/xk81jt69q

Supplemental Material

Download (23.7 KB)Acknowledgment

The primary studies analyzed in this review were identified through a systematic review project. Special thanks are extended to all members of the systematic review team for their contribution to the literature search and screening.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2288955.

Data availability statement

References for the primary studies are provided in the reference list and can be accessed through publicly available databases.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xiangyou Shen

Dr. Xiangyou Shen leads the Health, Environment, and Leisure (HEAL) research lab at Oregon State University. Her research focuses on the assessment and activation of play and playfulness in adulthood, and their impacts on human wellbeing, creativity, and performance. She also studies leisure as a vital context for health and self-actualization across the lifespan.

Leland Masek

Leland Masek is a PhD student in Media, Communication, and Performance Arts at Tampere University. His research focuses on playfulness across disciplines and cultures as it relates to mental health. He has also studied experimental game design and childhood development through play.

References

- Ablon, S. L. (2001). Continuities of tongues: A developmental perspective on the role of play in child and adult psychoanalytic process. Journal of Clinical Psychoanalysis, 10(3), 354–365. https://pep-web.org/browse/document/jcp.010.0345a?page=P0345

- Abós, Á., Sevil-Serrano, J., Julián-Clemente, J. A., Generelo, E., & García-González, L. (2019). Improving teachers’ work-related outcomes through a group-based physical activity intervention during leisure-time. The Journal of Experimental Education, 89(2), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2019.1681349

- Aune, K. S., & Wong, N. C. H. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of adult play in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00019

- Axline, V. (1969). Play therapy. Ballantine Books.

- Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of play-fulness in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.018

- Barnett, L. A. (2018). Conceptual models of the playfulness construct: Additive, balanced, or synergistic? Archives of Psychology, 2(7), 36. https://doi.org/10.31296/aop.v2i7.79

- Bateson, P., & Nettle, D. (2014). Playfulness, ideas, and creativity: A survey. Creativity Research Journal, 26(2), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.901091

- Berger, P., Bitsch, F., Bröhl, H., & Falkenberg, I. (2018). Play and playfulness in psychiatry: A selective review. International Journal of Play, 7(2), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1383341

- Betcher, R. W. (1981). Intimate play and marital adaptation. Psychiatry, 44(1), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1981.11024088

- Bradt, J., Potvin, N., Kesslick, A., Shim, M., Radl, D., Schriver, E., Gracely, E. J., & Komarnicky-Kocher, L. T. (2014). The impact of music therapy versus music medicine on psychological outcomes and pain in cancer patients: A mixed methods study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(5), 1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2478-7

- Bratton, S., & Ray, D. (2000). What the research shows about play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 9(1), 47–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089440

- Bratton, S. C., Ray, D., Rhine, T., & Jones, L. (2005). The efficacy of play therapy with children: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcomes. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.4.376

- Browne, J., Estroff, S. E., Ludwig, K., Merritt, C., Meyer-Kalos, P., Mueser, K. T., Gottlieb, J. D., & Penn, D. L. (2018). Character strengths of individuals with first episode psychosis in individual resiliency training. Schizophrenia Research, 195, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.09.036

- Ceranoglu, T. A. (2010). Video games in psychotherapy. Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 14(2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019439

- Chang, P.-J., Yarnal, C., & Chick, G. (2016). The longitudinal Association between playfulness and resilience in older women engaged in the red hat Society. Journal of Leisure Research; Urbana, 48(3), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2016-v48-i3-6256

- Colarusso, C. A. (1993). Play in adulthood: A developmental consideration. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 48(1), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00797308.1993.11822386

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. Jossey-Bass.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1981). Some paradoxes in the definition of play. In A. T. Cheska (Ed.), Play as Context: 1979 proceedings of the Association for the Anthropological Study of Play (pp. 14–26). West Point, NY: Leisure Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Play and intrinsic rewards. In flow and the foundations of positive psychology. Springer.

- Damian, R. I., Spengler, M., Sutu, A., & Roberts, B. W. (2019). Sixteen going on sixty-six: A longitudinal study of personality stability and change across 50 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 674–695. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000210

- Dobbins, S., Hubbard, E., Flentje, A., Dawson-Rose, C., & Leutwyler, H. (2020). Play provides social connection for older adults with serious mental illness: A grounded theory analysis of a 10-week exergame intervention. Aging Mental Health, 24(4), 596–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1544218

- Erez, A. B.-H., Katz, N., & Waldman-Levi, A. (2016). Protective personality variables and their effect on well-being and participation in the elderly: A pilot study. Healthy Aging Research, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HXR.0000508388.87759.42

- Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). Norton.

- Felsman, P., Gunawardena, S., & Seifert, C. M. (2020). Improv experience promotes divergent thinking, uncertainty tolerance, and affective well-being. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100632

- Feniger-Schaal, R., & Orkibi, H. (2020). Integrative systematic review of drama therapy intervention research. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 14(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000257

- Ferland, F. (1997). Play, children with physical disabilities and occupational therapy: The ludic model. University of Ottawa Press.

- Flint, S. W., Lam, M. H. S., Chow, B., Lee, K. Y., Li, W. H. C., Ho, E., Yang, L., & Yung, N. K. F. (2017). A systematic review of recreation therapy for depression in older adults. Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 7(2), ISSN 2161–0487. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0487.1000298

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions. American Scientist, 91(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1511/2003.26.330

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Unpacking positive emotions: Investigating the seeds of human flourishing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 57–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510981

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000238

- Freud, A. (1928). Introduction to the techniques of child analysis. Nervous & Mental Disease Publishing.

- Frey, D. (2014). Play therapy interventions with adults. In K. M. Clark (Ed.), Play therapy: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice (pp. 452–464). Guilford Press.

- Gibson, J. L., Pritchard, E., & de Lemos, C. (2021). Play-based interventions to support social and communication development in autistic children aged 2–8 years: A scoping review. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 6, 23969415211015840. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969415211015840

- Gitlin-Weiner, K. (2006). Clinical perspectives on play. In D. P. Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.), Play from birth to twelve: Contexts, perspectives, and meanings (2nd ed., pp. 353–368). Routledge.

- Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1992). The adult playfulness scale: An initial assessment. Psychological Reports, 71(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.1.83

- Glynn, M. A., & Webster, J. (1993). Refining the nomological net of the adult playfulness scale: Personality, motivational, and attitudinal correlates for highly intelligent adults. Psychological Reports, 72(3, Pt 1), 1023–1026. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.1023

- Grey, P. (2015). Studying play without calling it that: Humanistic and positive psychology. In J. E. Johnson, S. G. Eberle, T. S. Henricks, & D. Kuschner (Eds.), The handbook for the study of play (pp. 121–138). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Guitard, P., Ferland, F., & Dutil, É. (2005). Toward a better understanding of playfulness in adults. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 25(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944920502500103

- Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Jensen, S. A., Biesen, J. N., & Graham, E. R. (2017). A meta-analytic review of play therapy with emphasis on outcomes measures. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(5), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000148

- Keisari, S., Gesser-Edelsburg, A., Yaniv, D., Palgi, Y., & Vaingankar, J. A. (2020). Playback theatre in adult day centers: A creative group intervention for community-dwelling older adults. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0239812. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239812

- Kent, C., Cordier, R., Joosten, A., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Bundy, A., & Speyer, R. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to improve play skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00181-y

- Klein, M. (1932). The psycho-analysis of children. Hogarth Press.

- Klein, M., Regev, D., & Snir, S. (2020). Using the clay slip game in art therapy: A sensory intervention. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(2), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1713833

- Kuhaneck, H., Spitzer, S. L., & Bodison, S. C. (2020). A systematic review of interventions to improve the occupation of play in children with autism. OTJR: Occupation, Participation & Health, 40(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449219880531

- Lau, H. M., Smit, J. H., Fleming, T. M., & Riper, H. (2017). Serious games for mental health: Are they accessible, feasible, and effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00209

- Lee, A. Y.-P., Wang, Y.-H., & Yang, F.-R. (2021). Feeling exhausted? Let’s play – how play in work relates to experi enced burnout and innovation behaviors. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(2), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09794-1

- Lelanc, M., & Ritchie, M. (2001). A meta-analysis of play therapy outcomes. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 14(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070110059142

- Lieberman, J. N. (1977). Playfulness: Its relationship to imagination and creativity. Academic Press.

- Lin, Y. W., & Bratton, S. C. (2015). A meta-analytic review of child centered play-therapy approaches. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00180.x

- Liu, X., Li, L., Cui, X., Dong, L., Li, C., Chen, X., Zhao, Y., & Yuan, J. (2012). Daxuesheng wanxing yu chengjiu dongji de guanxi yanjiu [research on relationship between playfulness and achievement motivation in university students]. Zhong Guo Quan Ke Yi Xue [Chinese General Practice], 15(8), 2823–2825.

- Magnuson, C. D., & Barnett, L. A. (2013). The playful advantage: How playfulness enhances coping with stress. Leisure Sciences, 35(2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.761905

- Martocchio, J. J., & Webster, J. (1992). Effects of feedback and cognitive playfulness on performance in microcomputer software training. Personnel Psychology, 45(3), 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1992.tb00860.x

- Masek, L., & Stenros, J. (2021). The meaning of playfulness: A review of the contemporary definitions of the concept across disciplines. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 12(1), 13–37. https://doi.org/10.7557/23.6361

- Millar, S. (1968). The psychology of play. Penguin.

- Mitsopoulou-Sonta, L. (2019). Working in group therapy during a period of social trauma. Group Analysis, 52(2), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316419834728

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Review, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Moon, J. W., & Kim, Y. G. (2001). Extending the TAM for a world-wide-web context. Information & Management, 38(4), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(00)00061-6

- Nisula, A.-M., & Kianto, A. (2018). Stimulating organisational creativity with theatrical improvisation. Journal of Business Research, 85, 484–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.027

- O’Connell, K. A., Gerkovich, M. M., Bott, M., Cook, M. R., & Shiffman, S. (2000). Playfulness, arousal-seeking and rebelliousness during smoking sensation. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(4), 671–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00224-X

- Pang, D., & Proyer, R. T. (2018). An initial cross-cultural comparison of adult playfulness in Mainland China and German-Speaking Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00421

- Papadopoulos, N. L. R., & Röhricht, F. (2018). A single case report of body oriented psychological therapy for a patient with chronic conversion disorder. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 61, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2018.09.001

- Petelczyc, C. A., Capezio, A., Wang, L., Restubog, S. L. D., & Aquino, K. (2018). Play at work: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 44(1), 161–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317731519

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York, NY: WW Norton.

- Proyer, R. T. (2011). Being playful and smart? The relations of adult playfulness with psychometric and self-estimated intelligence and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(4), 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.02.003

- Proyer, R. T. (2012). Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness: The SMAP. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(8), 989–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.018

- Proyer, R. T. (2013). The well-being of playful adults: Adult playfulness, subjective well-being, physical well-being, and the pursuit of enjoyable activities. The European Journal of Humour Research, 1(1), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2013.1.1.proyer

- Proyer, R. T. (2014). To love and play: Testing the Association of adult playfulness with the relationship Personality and relationship satisfaction. Current Psychology, 33(4), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9225-6

- Proyer, R. T., & Brauer, K. (2017). A new structural model for the study of adult playfulness: Assessment and exploration of an understudied individual differences variable. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.011

- Proyer, R. T., Brauer, K., & Wolf, A. (2020). Assessing other-directed, lighthearted, intellectual, and whimsical playfulness in adults: Development and initial validation of the OLIW-S using self- and peer-ratings. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 36(4), 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000531

- Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Bertenshaw, E. J., & Brauer, K. (2018). The positive relationships of playfulness with indicators of health, activity, and physical fitness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01440

- Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Brauer, K., & Chick, G. (2020). Can playfulness be stimulated? A randomised placebo‐controlled online playfulness intervention study on effects on trait playfulness, well‐being, and depression. Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12220

- Qian, X. L., & Yarnal, C. (2011). The role of playfulness in the leisure stress-coping process among emerging adults: An SEM analysis. Leisure/loisir, 35(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.578398

- Råbu, M., Halvorsen, M. S., & Haavind, H. (2011). Early relationship struggles: A case study of alliance formation and reparation. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.546073

- Ramsden, H. (2017). Walking & talking: Making strange encounters within the familiar. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1174284

- Ray, D. C., Armstrong, S. A., Balkin, R. S., & Jayne, K. M. (2015). Child-centered play therapy in the schools: Review and meta-analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 52(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21798

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Schaefer, C. E. (Ed.). (2003). Play therapy with adults. John Wiley & Sons.

- Schaefer, C. E., & Greenberg, R. (1997). Measurement of playfulness: A neglected therapist variable. International Journal of Play Therapy, 6(2), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089406

- Schreiber-Willnow, K., & Seidler, K.-P. (2013). Therapy goals and treatment results in body psychotherapy: Experience with the concentrative movement therapy evaluation form. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 8(4), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2013.834847

- Schueller, S. M. (2010). Preferences for positive psychology exercises. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(3), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439761003790948

- Schueller, S. M. (2014). Person–activity fit in positive psychological interventions. In A. C. Parks & S. M. Schueller (Eds.), The wiley blackwell handbook of positive psychological interventions (pp. 385–402). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118315927.ch22

- Schwartzman, H. B. (1978). Transformations: The anthropology of children’s play. Plenum Press.

- Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

- Shen, X. (2010). Adult Playfulness as a Personality Trait: Its Conceptualization, Measurement, and Relationship to Psychological Well-Being. (Publication No. 3576769) [Doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Shen, X. (2020). Constructing an interactionist framework for playfulness research: Adding psychological situations and playful states. Journal of Leisure Research, 51(5), 536–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1748551

- Shen, X., Chick, G., & Pitas, N. (2017). From playful parents to adaptable children: A structural equation model of the relationships between playfulness and adaptability among young adults and their parents. International Journal of Play, 6(3), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1382983

- Shen, X., Chick, G., & Zinn, H. (2014a). Playfulness in adulthood as a personality trait: A reconceptualization and a new measurement. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(1), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950313

- Shen, X., Chick, G., & Zinn, H. (2014b). Validating the adult playfulness trait scale (APTS): An examination of the Personality, behavioral, attitudinal, and perceptual nomological network of playfulness. American Journal of Play, 6(3), 345–369. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1032064

- Shen, X., Liu, X., Masek, L. (2023). Play and Playfulness in psychological interventions for adults: An integrative systematic review. Manuscript in preparation.

- Shen, X., Liu, H., & Song, R. (2021). Toward a culture-sensitive approach to playfulness research: Development of the adult playfulness trait scale-chinese version and an alternative measurement model. Journal of Leisure Research, 52(4), 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1850193

- Shuper-Engelhard, E., & Vulcan, M. (2018). Introducing movement into couple therapy: Clients’ expectations and perceptions. Contemporary Family Therapy, 41(1), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-018-9474-x

- Stenros, J. (2015). Playfulness, play, and games: A constructionist ludology approach. Games and Culture, 10(3), 314–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014559978

- Sutton-Smith, B. (2008). Play theory: A personal journey and new thoughts. American Journal of Play, 1(1), 82–125. https://www.museumofplay.org/app/uploads/2022/01/1-1-article-sutton-smith-play-theory.pdf

- Sutton-Smith, B. (2009). The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press.

- Tegano, D. W. (1990). Relationship of tolerance of ambiguity and playfulness to creativity. Psychological Reports, 66(3), 1047–1056. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3.1047

- Tonkin, A., & Whitaker, J. (Eds.). (2016). Play in healthcare for adults: Using play to promote health and wellbeing across the adult lifespan. Routledge.

- Valenta, M., Lessner Listiakova, I., & Silarova, L. (2014). Evaluation of dramatherapy process with clients in addictions rehabilitation community. Clinical Psychology and Special Education, 3(3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280494845_Evaluation_of_Dramatherapy_Process_with_Clients_in_Addictions_Rehabilitation_Community

- Van Lith, T., Beerse, M., & Smalley, Q. (2020). A qualitative inquiry comparing mindfulness-based art therapy versus neutral clay tasks as a proactive mental health solution for college students. Journal of American College Health, 70(6), 1889–1897. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1841211

- Van Vleet, M., & Feeney, B. C. (2015). Play behavior and playfulness in adulthood: Play and playfulness. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(11), 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12205

- Versluys, B. (2017). Adults with an anxiety disorder or with an obsessive-compulsive disorder are less playful: A matched control comparison. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 56, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.06.003

- Weisler, A., & McCall, R. B. (1976). Exploration and play. The American Psychologist, 31(7), 492–508.

- Wellenzohn, S., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2018). Who benefits from humor-based positive psychology interventions? The moderating effects of personality traits and sense of humor. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 821. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00821

- West, S. E., Hoff, E., & Carlsson, I. (2017). Play and productivity: Enhancing the creative climate at workplace meetings with play cues. American Journal of Play, 9(1), 71–86. https://link-galegroup-com.ezproxy.proxy.library.oregonstate.edu/apps/doc/A492536717/AONE?sid=lms

- West, S., Hoff, E., & Carlsson, I. (2017). Enhancing team creativity with playful improvisation theater: A controlled intervention field study. International Journal of Play, 6(3), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1383000

- Wilkinson, N., Ang, R. P., & Goh, D. H. (2008). Online video game therapy for mental health concerns: A review. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54(4), 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008091659

- Winnicott, D. W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena; a study of the first not-me possession. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 34(2), 89–97.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Basic Books.

- Yonatan-Leus, R., Shefler, G., & Tishby, O. (2019). Changes in playfulness, creativity and honesty as possible outcomes of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(6), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1649733

- Yonatan-Leus, R., Shefler, G., & Tishby, O. (2020). Do positive features of mental health change together with symptoms and do they predict each other? Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 57(3), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000280. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 31999187.

- Yonatan-Leus, R., Tishby, O., Shefler, G., & Wiseman, H. (2018). Therapists’ honesty, humor styles, playfulness, and creativity as outcome predictors: A retrospective study of the therapist effect. Psychotherapy Research, 28(5), 793–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1292067

- Youell, B. (2008). The importance of play and playfulness. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 10(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642530802076193

- Yue, X. D., Leung, C. L., & Hiranandani, N. A. (2016). Adult playfulness, humorstyles, and subjective happiness. Psychological Reports, 119(3), 630–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116662842

- Yu, P., Wu, J. J., Chen, I. H., & Lin, Y. T. (2007). Is playfulness a benefit to work? Empirical evidence of professionals in Taiwan. International Journal of Technology Management, 39(3/4), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2007.013503

- Yu, P., Wu, J., Lin, W., & Yang, G. (2003). Development of adult playfulness and organizational playfulness climate scales. psychology Test, 50(1), 73–110. https://doi.org/10.7108/PT.200306.0073