ABSTRACT

In a volatile and ever-changing world, creativity and wellbeing are essential for learners to flourish. With lagging educational models and siloed thinking and practice surrounding wellbeing and creativity, a new model of creativity and wellbeing is needed. Creative-Being is offered as a dualistic systemic model that is grounded in a Systems Informed Positive Education perspective, encompassing negative emotion as a mechanism to promote both creativity and wellbeing, or creative flourishing. Designed to equip learners, Creative-Being offers fresh insights into the positive transforming power of negative emotion in the creative process, providing an important step forward in furthering positive education.

Introduction

Positive creative achievements are often born of negative emotions: a song inspired from heartbreak, an artwork created amidst frustration, a new idea after anguished failures. German composer Ludwig van Beethoven, for instance, wrote despairingly about his increasing deafness:

What humiliation when any one beside me heard a flute in the far distance, while I heard nothing, or when others heard a shepherd singing, and I still heard nothing! Such things brought me to the verge of desperation, and well nigh caused me to put an end to my life (Beethoven & Wallace, Citationn.d., p. 42)

Twenty-first century learners: the importance of wellbeing and creativity

With our world described as volatile and unpredictable (Tan, Citation2015), negative emotion is an unavoidable reality, and creativity is a necessity. The Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD, Citation2018) argued that creativity is essential for 21st century learners and formal education should nurture creativity to enable success. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence have shifted employment skills, emphasising innovation and flexible thinking (Amabile, Citation1997), which relate to creativity (OECD, Citation2018). As a complex phenomenon enabling economics, technology, and science, creativity refers to the manufacturing of novel and useful ideas or problem solutions (Amabile, Citation1983, Weisberg Citation1988). Creativity equips us to facilitate and cope with rapid change (Plucker, Beghetto, & Dow, Citation2004), and therefore is essential for learners to flourish.

Wellbeing is also essential for learners, with the United Nations (Citation2019) identifying wellbeing as a prioritised goal. A multi-dimensional construct, wellbeing has multiple elements and definitions (Oades & Mossman, Citation2017), with no consensus on a single definition or even spelling (Kern et al., Citation2020). The term wellbeing has been used interchangeably with positive mental health (World Health Organization, Citation2001), happiness (Forgeard et al., Citation2011), and flourishing (Seligman, Citation2011). It is sometimes referred to as Psychological Wellbeing (Ryff, Citation1989, Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995) or Subjective Wellbeing (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008). From a hedonic perspective, wellbeing encompasses the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain (hedonic wellbeing) (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). From a eudaimonic perspective, wellbeing represents the life well lived (Gale et al. Citation2013). For the purpose of the Creative-Being model, the eudaemonic wellbeing definition will be used due to its focus on meaning and its alignment with creativity research. Studies indicate creativity and eudaemonic wellbeing are related, with creativity promoting healthy psychological functioning, effective coping, loving relationships, meaning, and problem-solving (Livingston Citation1999, Lomas, Citation2016b, Terr, Citation1992). Creativity not only promotes wellbeing (Torrance, Citation1981), but is also promoted by wellbeing, such that a bi-directional relationship between the two exists (Huppert & So, Citation2013).

Lagging educational models

Education experts argue that most 21st century students are being educated by twentieth century teaching practices, in nineteenth century educational institutions (Schleicher, Citation2018). Standardised testing and grade-based assessment are frequent indicators of achievement (Kern & Wehmeyer, Citation2021). Some thrive within such practices, yet many languish. Student disengagement, mental health issues (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021), and teacher burnout (Thomson, Citation2020) indicate current educational practices are insufficient. Indeed, Robinson (Citation2006) suggests educational practices are killing creativity – the very quality required for success in a twenty-first century world.

Positive education addresses some of these issues yet is not always effective. Despite positive psychology research evolving to encompass a systems perspective (Kern & Wehmeyer, Citation2021), positive education practice is lagging. Many schools incorporate curricula, programs, and interventions without consideration of complex dynamic school environments (Allison et al., Citation2020, Kern & Taylor, Citation2021). Educational experts argue that contemporary education ‘must focus on nurturing the whole child’ (National Institute of Education, Citation2017, p. 2), yet positive education is often limited by irrelevance to rapidly changing systemic environments encompassing personality, personal history, and socio-cultural context (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021). Adopting a holistic systems perspective towards positive education and creativity, therefore, is both timely and necessary.

A systems perspective

Systems are collections of living or nonliving things with different components interacting to create a coherent whole (Meadows, Citation2008). Systems are connected simultaneously using inputs, processes, outputs with distinct boundaries, and feedback loops with system outputs returning as inputs. Systems informed positive psychology assumes that humans inter-dependently co-exist with themselves, others, and the environment in which they exist (Kern et al. Citation2020). Systems informed positive education (SIPE) acknowledges complexity, inter-relatedness, and the dynamic nature of the individual, school environment, society, and the world within which it is all embedded (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021). A systems perspective is relevant for our global climate, enabling a holistic picture of self, school, society, and the world. If we are to equip learners to thrive in our world, embedding a systems perspective into education and creativity is essential (Senge et al., Citation2012).

Creativity theory and the role of negative emotion

Creativity theory initially focused on individuals. Later theories highlighted creativity’s role in human development and personality, identifying different levels of individual creativity (Guilford, Citation1950). Kaufman and Beghetto (Citation2009) built on this layered perspective, arguing that genius level creativity cannot exist without everyday creativity, which suggests creative growth can be cultivated in everyone rather than existing within a gifted few. Such theories bring understanding to the creative process yet are restricted to an individual’s cognitive processes.

Creativity is dynamic and systemic (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2008). For example, Amabile’s (Citation1983, Citation1996) Componential Model of Creativity illustrates the social influences on creative behaviour, integrating cognitive, personality, emotional, motivational, and social environmental domains (Amabile et al., Citation2005). Positive mood improves performance elements of creativity (Estrada et al., Citation1994, Isen, Citation1999, Isen & Daubman, Citation1984, Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, Citation1987), and positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and cognition (Fredrickson, Citation1998, Citation2001), increasing one’s propensity for creativity.

Such research indicates that creativity and positive emotions are interrelated, yet some theorists further highlight the role of negative emotion in creativity. Negative emotions are unpleasant feelings and are linked to mood disorders (Kashdan & Biswas-Diener, Citation2015). Yet negative emotion can also be positively transformative, intrinsically motivating personal change (Lomas, Citation2016a). Connections between emotion and creativity are complex, systemic, and dynamic. For example, Martin’ et al. (Citation1993) mood-as-input model suggests positive or negative emotion may influence motivation and persistence during creative tasks. Amabile (Citation1988, Citation1996) supports Martin et al’.s research, whereas Jamison (Citation1989) posits that changes from negative to positive emotion promote creativity. Such findings indicate negative emotions may play an important and often overlooked role in creativity.

The need for a new way of thinking about wellbeing and creativity

There is a parallel need for a systems perspective of education and a new way of thinking about wellbeing and creativity. Creativity research has traditionally centered around individuals and predominantly focused on positive emotion. While popular creativity systems models acknowledge the influence of social systems and emotion (e.g. Amabile et al., Citation2005, Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014), limitations include focusing on the person and process rather than upon the outcomes of creativity (Spiel & Von Korff, Citation1998). Creativity research indicates inter-relatedness between creativity and wellbeing (Livingston, Citation1999, Lomas, Citation2016b), yet existing models ignore wellbeing and creativity interactions, including potential systemic feedback (Kuo, Citation2011). Wellbeing frameworks are often limited by the decontextualisation of wellbeing from human and social systems (Kern et al., Citation2020). Yet bio-directional creativity and wellbeing are essential for future learners, with a dynamic global climate dominated by complex negative human experiences a pervading contextual reality. The third wave of positive psychology embraces such complexity (Lomas, et al., Citation2020). This recent evolution of positive psychology scholarship involves looking beyond the individual to examine the complex systems in which people exist. New holistic and systemic ways of thinking about wellbeing and creativity align with this third wave evolution. We suggest, therefore, that a new SIPE model acknowledging the inter-relatedness of creativity, wellbeing, and negative emotion may be beneficial in effectively equipping contemporary learners.

Concepts underpinning the creative-being model

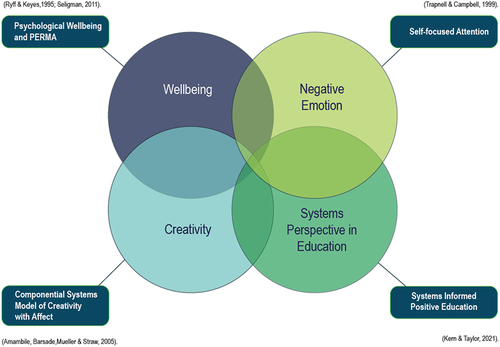

As illustrated in , Creative-Being is underpinned by four intersecting domains: systems perspectives in education, creativity, negative emotion, and wellbeing.

Systems perspective in education

Creative-Being is viewed through a holistic SIPE lens, which encourages us to embrace simplexity, where simple learning systems exist within complex school environments (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021). Creative-Being holistically embraces the complexity and interactions of human systems, cognitive, and emotional processes, which is necessary for real-world relevant learning (Goleman & Senge, Citation2014). A systems perspective prioritises real-world relevance, providing ‘the combination of social, emotional, and systemic understanding that offers the fullest preparation of students for life’s challenges’ (Goleman & Senge, Citation2014, p. 2). For example, learning surrounding creativity and wellbeing becomes process-driven rather than content-driven. Challenges of embedding SIPE include the complexity of a diverse number of stakeholders, including policymakers, parents, and teachers (Goleman & Senge, Citation2014). SIPE approaches, such as Creative-Being, are a step in the direction towards holistic real-world relevant future learning.

Creativity

Creative-Being builds upon the revised Componential Model of Creativity (Amabile, Citation1996, Amabile et al., Citation2005, Amabile & Pillemer, Citation2012). The Componential Model includes domain-relevant skills (e.g. talent, skill, expertise), creativity-relevant processes (e.g. personality traits such as persistence and curiosity), intrinsic motivation (internal motivation for tasks), affect (positive and negative emotion), and social context (e.g. the microsystem of the classroom) (Amabile & Pillemer, Citation2012). This model assumes components combine in a generative manner, with all components present if creativity is to be the result (Amabile & Pillemer, Citation2012). Within Creative-Being, domain-relevant skills and internal motivation components appear respectively through mechanisms within the wellbeing (accomplishment and engagement) and negative emotion domains (self-reflective rumination).

Field research has focused on organisations, but Amabile et al. (Citation2005) indicate that the model is a catalyst for broader applications. Qualitative analysis indicated some participants first experienced task-based frustration with creativity tasks, followed by positive emotions. Amabile et al. posit that the negative emotion of frustration could promote creative output and creative problem solving. The outcome of positive emotion in their results highlights the relationship between wellbeing and creativity, with others finding similar results (Du et al, Citation2021, Frijda, Citation1993, George & Zhou, Citation2002, Lazarus & Cohen-Charash, Citation2001). The Componential Model’s holistic and systemic nature, therefore, provides a relevant foundation for Creative-Being to build upon.

Wellbeing

Two wellbeing frameworks underpin Creative-Being: Ryff and Keyes’ (Citation1995) psychological wellbeing (PWB) and Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment). Research indicates that creativity promotes a sense of meaning, personal growth, life satisfaction, and positive relationships (Livingston, Citation1999, Lomas, Citation2016b, Terr, Citation1992, Torrance, Citation1981), aligning with the PWB components (environmental mastery, personal growth, self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, purpose in life). Jayawickreme et al. (Citation2012), in their Engine of Wellbeing, identify PWB an input into a larger system. Rusk’ et al. (Citation2017) research indicates that PWB may also be a process. Yet PWB fails to indicate the output of voluntary behaviours characteristic of wellbeing, which PERMA does (Rusk, Vella-Brodrick, & Waters, Citation2017). Therefore, both PWB and PERMA underpin Creative-Being due to their specific characteristics and mechanisms.

Negative emotion

As described above, negative emotion plays an important and often overlooked role in creativity. Similarly, negative emotion has become increasingly recognised as playing a role in wellbeing and PP scholarship. A consistent criticism of PP is that it has disregarded the existence and advantages of negative emotions and experiences within the wellbeing construct. However, over the past decade, a shift or second wave occurred within the PP movement that brought negative emotion to the forefront (Wong, Citation2011). Rather than seeing negative emotions as the enemy to wellbeing, the second wave of positive psychology (PP 2.0) aimed to highlight the essential tension and balance between positive and negative (Lomas & Ivtzan, Citation2016, Wong, Citation2011). PP 2.0 (Wong, Citation2011) supports the inclusion of the negative emotion domain within the Creative-Being model, as well as the following underpinning mechanisms that enable the processing of negative emotions.

Self-focused Attention (SFA) (Ingram, Citation1990) ‘represents the capacity of becoming the object of one’s own attention, where one actively identifies, processes, and stores information about the self’ (Morin, Citation2011, p. 807), and underpins the negative emotion domain of Creative-Being. Trapnell and Campbell (Citation1999) sub-categorise SFA as reflection and rumination, with different characteristics having different connections to creativity (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2005, Citation2014). Reflection has several stages: awareness of negative emotions or thoughts, critical analysis, and the evolution of a new perspective (Atkins & Murphy, Citation1993). Reflection includes gaining distance from negative emotions to enable perspective, and building momentum or initiating progress (Morin, Citation2011). Even if negative emotions are the catalyst, the mechanism of reflection involves deep thinking, enabling moving from a state of negative emotion to a desired positive state (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2005). Therefore, reflection is positively associated with problem solving, wellbeing, healthy psychological functioning, and intrinsic motivation (Takano & Tanno, Citation2009). In contrast, rumination is circular consisting of ‘anxious attention paid to the self’ (Morin, Citation2011, p. 809), involving repetitive thinking around loss and failure, and is associated with low self-worth (Takano & Tanno, Citation2009), anxiety, and depression (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2014).

While both mechanisms involve deep thinking and recognition of a desired goal, the effects differ. Rumination tends to be maladaptive, limiting individuals from adapting to different situations, whereas reflection is more adaptive, generating insight and motivation (Takano & Tanno, Citation2009). Such paradoxical qualities of self-reflective rumination highlight possible limitations; however, an acceptance of dualism aligns with a systems perspective. This dualistic nature of self-reflective rumination enhances creativity. Rumination without reflection may mean limited progression towards creativity (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2014). It is this dualism that appears to create a balancing pattern, where rumination and self-reflection dance together to enable creativity.

Creative-being

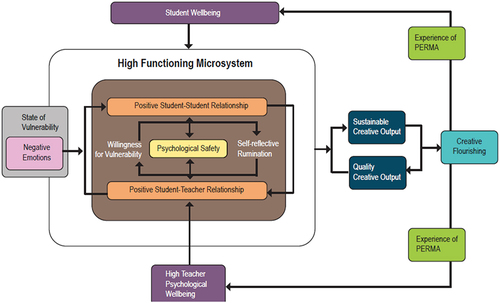

Building upon the four domains described above, Creative-Being () offers a holistic model of creativity and wellbeing. Creative-Being was born in the classroom. The first author, a creative-arts educator, singer-songwriter, entertainer, and wellbeing specialist, observed many experiencing negative emotions within a creative task. Through decades of reflection, analysis, and mentoring educators and artists, the Creative-Being model has evolved. Reflecting on her own creative journey, the first author acknowledges that many personal experiences with creative flourishing are born from negative emotion. For example, one of her most successful songs was written in the midst of deep grief over the death of her mother. Additionally, numerous students the first author taught often struggled in multiple classes displaying deviant behaviour, high levels of anxiety, low levels of learning engagement, and task refusal. Yet over time, these students often produced high-quality creative outputs, significant positive behaviour, and attitudinal changes within her creative education classroom. These behavioural and attitudinal changes even at times appeared to be an output that overflowed into other areas of learning. The need to articulate the process of how creativity appeared to have connections to wellbeing, often occurring even when negative emotions were present, developed from here. The second and third authors assisted in refining the Creative-Being model and its articulation during the first author’s Masters of Positive Psychology capstone project at the University of Melbourne.

While Creative-being’s origins lie in the creative-arts classroom, the desired output of the model is the dualistic construct of creative flourishing within any curriculum area and developmental stage. Creative flourishing is recognised as creative output within a specific culture that is of sustainable and high quantity, which promotes wellbeing. Creative-Being is designed to promote both wellbeing and creativity in future learners and acknowledges the reality of negative emotion as an input within the environment. Elements within this dynamic system interact and connect, relying on these interactions to fulfill its purpose.

System inputs

The model begins with three inputs: vulnerability, negative emotions, and student and teacher wellbeing.

The state of vulnerability

Brown (Citation2013) suggests vulnerability is the birthplace of creativity. Vulnerability (Grey in ) co-exists with emotions, and is defined as ‘uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure’ (Brown, Citation2013, p. 44). For example, a student who experiences fear regarding a problem-solving task is vulnerable. They may have thoughts such as ‘what if I get it wrong?’ Being vulnerable is frightening for people who fear rejection. Some may argue that promoting emotional vulnerability puts students at risk of experiencing exploitation, discrimination, or even abuse (Fineman, Citation2017). However, vulnerability is where risk-taking happens, and creativity and problem solving begins (Brown, Citation2013). A state of vulnerability is a necessary co-existing input with negative emotions within Creative-Being.

Negative emotion

Despite its unpleasant quality, negative emotion (pink in ) has the potential to positively influence task motivation and increase persistence in problem solving and task completion (Martin et al., Citation1993, Schwarz, Citation1990). For example, a student may have a negative experience during lunchtime, causing anxiety. When they enter the classroom, this emotion is an input into the learning environment (Martin et al., Citation1993). Studies illuminate negative emotion’s relationship with creativity and self-reflective rumination. For example, a study of Chinese college students found correlations between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and creativity (Du et al., Citation2021); the more participants were negatively affected by events surrounding COVID-19, the higher they scored on creativity. Negative emotions may promote creativity through enhanced perseverance (Baas et al., Citation2008). Self-reflective rumination also interacts with negative emotions, with several studies indicating an inter-relationship amongst loss, fear of failure, and rumination (Trapnell & Campbell, Citation1999, Verhaeghen et al., Citation2005, Citation2014). Some positive education practices encourage students to avoid negative emotions (White, Citation2016), yet studies indicate that learning can be enhanced by negative emotion (Rowe & Fitness, Citation2018).

Student and teacher wellbeing

Wellbeing (Purple in ) is an input that interacts with relationships and psychological safety. First, high teacher PWB as an input is strongly connected to teaching practice, which impacts learning outcomes (Turner & Thielking, Citation2019). This connection is evident through PWB’s element of positive relationships (Wanless, Citation2016). High teacher PWB prioritises positive relationships, providing a sense of belonging and trust (Liu et al., Citation2021, Turner & Thielking, Citation2019), fostering risk-taking with learning. In practice, high teacher wellbeing is indicated by quality time with students, calm teacher responses, positive student relationships, and increased student performance (Turner & Thielking Citation2019).

Student PWB is an additional input. A range of socio-ecological factors interact with student wellbeing, including teacher-student relationships (Cornelius-White, Citation2007), student-student relationships, and a sense of safety, trust, belonging, and connectedness (Allen et al., Citation2016). As positive education practice frequently fails to acknowledge the influence of the complex school environment and collective wellbeing (Allison et al., Citation2020), individual PWB may be problematic. However, individual PWB is an input into a complex system that acknowledges continuous interaction with contextual elements, as indicated by cyclical arrows. These dynamic interactions between individual wellbeing, positive relationships, and psychological safety are part of the enabling process of both individual and collective creative flourishing, and a high functioning microsystem.

System processes

Four system processes occur within the Creative-Being model: willingness to be vulnerable, self-reflective rumination, psychological safety and positive relationships, and a high functioning microsystem.

A willingness to be vulnerable

Research indicates vulnerability is the core of meaningful human experiences (Brown, Citation2013), yet it is frequently avoided. If a student is willing and motivated to be vulnerable with fear or frustration, negative emotions are often antecedents to self-reflection and problem solving (Takano & Tanno, Citation2009). It is not a static state, but dynamic (Brown, Citation2013), and is key to Creative-Being mechanisms by influencing task motivation, via dynamic cyclical interactions with self-reflective rumination and psychological safety (Amabile, et al., Citation2005). While society sends implicit messages that a willingness to be vulnerable is a sign of weakness, Brown (Citation2018, p. 13) argues that students ‘deserve one place where they can rumble with vulnerability and their hearts can exhale’. An environment where mistake making is embraced will promote such willingness. The classroom microsystem, therefore, ideally can enable students to process negative emotions in an environment of psychological safety within the creative process.

Self-reflective rumination

Self-reflective rumination (Brown in ) is inter-related to creativity and negative emotion, interacting with a willingness to be vulnerable. The willingness to explore negative emotion enables self-reflective rumination, promoting powerful reflective thought processes and motivating perseverance, which increases creative output (Baas et al., Citation2008, Kaufman & Baer, Citation2002, Verhaeghen et al., Citation2005). In one study, participants experienced both positive and negative emotion during a creative task, with negative emotions often associated with fear of failing (Amabile et al., Citation2005). Similarly, Smith and Alloy (Citation2009) argue that the cyclical process of rumination involves repetitive thoughts containing themes of failure. The cycle between self-reflective rumination and willingness to be vulnerable within Creative-Being aligns with the cyclical nature of rumination.

It may be risky to emphasise rumination, considering links to depression (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2014). However, when co-existing with self-reflection, rumination may increase creativity and wellbeing (Harrington & Loffredo, Citation2011). Negative emotions are a valuable part of being human, and can be positively transformative (Lomas, Citation2016b). Self- reflective rumination may enable this positive transformative process through the adaptive nature of reflection. Emphasising the dualistic process of reflection and rumination is therefore key to promoting creative behaviour. For example, a student experiencing a fear of failure, if willing to be vulnerable through rumination and reflection, may become more motivated to move forward through the creative process. Ryan (Citation2009) supports this, suggesting that both desire and motivation are required for change to happen, and self-reflection enables progress.

Psychological safety and positive relationships

Psychological safety (Yellow in ) is central to the vulnerability and self-reflective rumination cycle. Psychological safety is the ‘shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’ (Edmondson, Citation1999, p. 54). Within the classroom microsystem, psychological safety promotes an environment where self-reflective rumination can safely occur, thus promoting creative output. Positive relationships within the microsystem provide psychological safety through greater emotional carrying capacity (Dutton & Heaphy, Citation2003), buffering against negative spiraling of emotion from rumination (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2014). For example, a teacher may create a safe classroom where mistakes are acceptable, expressing anxieties is encouraged, and collaborative problem solving are the norm. The greater the capacity for the relationship to carry the full spectrum of emotions, the greater the psychological safety, with individuals recognising that negative emotions can be appropriately expressed without shame and rejection (Dutton & Heaphy, Citation2003). This dynamic relationship between psychological safety and positive relationships is an essential part of the self-reflective/vulnerability cycle in the Creative-Being process.

High functioning microsystem

An individual’s immediate microsystem influences both the creative process (Amabile et al., Citation2005, Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014) and wellbeing (Lomas et al, Citation2020, Kern et al. Citation2020). Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological systems model highlights how the intra-personal, environmental, behavioural, and political domains of the school environment impact both educators and learners. According to this theory, a classroom is a dynamic, non-linear human social microsystem in constant interaction (Allison et al., Citation2020). Microsystems exist in many institutions with varying levels of functioning. Bosworth and Judkins (Citation2014) suggest that high functioning classroom microsystems are characterized by a safe and caring climate, inclusive of all members. Furthermore, studies indicate that the functionality of a student’s microsystem influences performance (Campos-Gil et al., Citation2020, Maxwell, Citation2010, Citation2016).

The microsystem (White in ) interacts with other elements, including psychological safety, positive relationships, self-reflective rumination, creative flourishing, and teacher/student wellbeing. Psychological safety through positive relationships prevents potential negative spiraling from rumination (Verhaeghen et al., Citation2014). For example, a teacher may establish collaboration groups to brainstorm ideas, creating a space for dialogue during problem solving and feedback during the creative process. Psychological safety promotes a safe climate within which risk taking can take place (Higgins et al., Citation2020), linking with vulnerability, negative emotions, and self-reflective rumination processes. A high functioning microsystem, therefore, contains essential elements that interact to promote creative flourishing.

System outputs and feedback loops

There are two system outputs, with corresponding feedback loops: Creative flourishing and PERMA.

Creative flourishing

Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2014) argued that creativity needs to be contextualized within the culture and seen as valuable within that context. Creativity is therefore the output of interactions between creators and their audiences. For example, what is creatively valuable in one microsystem may vary in another, as microsystems are influenced by broader perspectives including political, social, and environmental influences (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). Creative flourishing (light blue in ) encompasses this phenomenon; it is creative output of high quality and sustainable quantity within the classroom microsystem context.

Flourishing, however, is the state created when we foster PERMA through the creativity processes including vulnerability, positive relationships, and self-reflective rumination within a psychological safe environment. These dynamic and interactive processes ultimately increase our positive emotions, engage us in learning, illuminate positive relationships, provide an opportunity for meaning, and achieve goals through applying strengths and talents in completing a creative task. Hence, this dualistic creative process that encompasses both creativity and wellbeing is encompassed within the construct of creative flourishing.

Perma

PERMA (Light green in ) emphasises behaviours characteristic of wellbeing as an endpoint (Rusk et al., Citation2017). PERMA is more than an endpoint; it feeds back as an input into the environmental context of the individuals. Universal evidence supports this bio-directionality, with studies highlighting a reciprocal relationship between creativity and wellbeing (Tan, et al., Citation2021). Another study found creative tasks promoted wellbeing (Vougioukalou et al., Citation2019). Studies indicate that higher states of wellbeing indicated by positive emotion and life satisfaction promote creativity, providing further indication that wellbeing plays a constructive role in creativity.

Discussion

The Creative-Being model offers a 21st century way of thinking about wellbeing and creativity. Designed to equip educators to enable creativity and wellbeing for learners, the empirically informed model is real-world relevant. The question is not whether creativity and wellbeing should be taught in schools, but what is the most relevant way of equipping students in creativity and wellbeing? As societies around the world emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic where individual and community innovation, health, and wellbeing have been under great duress, prioritising wellbeing and creativity in education seems crucial. Creative-Being has the potential to inform the narrative of shifting educational priorities, from siloed linear perspectives to dynamic holistic systems thinking and learning.

Practical implications

Creative-Being has implications for building on future SIPE research, as well as implications for Positive Education applications. A first implication is that the Creative-Being model challenges current educational models with its systems perspective, by providing an opportunity for a shift to occur in the role of the teacher, from expert in knowledge to facilitator of cognitive and emotional system processes. While learning environments applying a SIPE approach to learning, such as Newmark Primary School (Newmark Primary Schools, Citation2021) in Victoria, do exist, they are few and far between (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021). Thus, Creative Being extends existing systems-informed approaches to everyday learning environments.

In a classroom where Creative-Being is applied, teachers facilitate an environment that builds positive connections between students where emotional vulnerability within an emotionally safe environment is the norm. Learners feel safe to fail and safe to make mistakes because they are positively connected to their peers and teachers. The students feel willing to be vulnerable when attempting new tasks, expressing curiosity, and sharing new ideas. Teachers enable the self-reflective rumination process and model it in their everyday interactions with students. Here, teachers prioritise their own wellbeing, understanding the influence it has in the environment in which the learner co-exists with them.

Secondly, the application of the model is not content driven, but rather emphasises the process and mechanisms of wellbeing and creativity, regardless of curriculum area. This is a critical shift, from a siloed subject based approach to creativity and wellbeing, to an integrated and holistic approach. While future learners are the focus of the model, its systemic nature also highlights the role of educators in the process. Thus, this model enables not only future learners, but also future educators promoting classroom practice that aligns with SIPE research. While Creative-Being may play only a small role in this shift, it is an important one, especially if learning is to be real-world relevant for our current global climate.

Limitations and future directions

Negative spiraling from rumination remains an ethical risk, despite the protective mechanisms of psychological safety and self-reflection within the model. The effectiveness of self-reflective rumination and psychological safety relies on the skill and wellbeing of the educator. With each educator bringing their own experience, understanding, and perspectives of wellbeing and creativity, the risk of poor implementation is real. Harm could be done though the implementation of the model to the very ones it is designed to equip.

Creative-Being thus requires training to minimise risk, requiring large scale prioritisation of creativity, wellbeing, and understanding of negative emotion. This approach involves building understanding and shifting misconceptions around these three interactive constructs (Lomas & Ivtzan, Citation2016). White (Citation2016) highlights the hurdles to ensuring longevity and success of training and implementation in positive education, including prioritising funding, the perception that wellbeing (and creativity) is a marginal topic, maverick providers implementing sub-standard training, and that wellbeing is not central to successful educational governance. Creative-Being requires the systemic co-prioritisation of wellbeing and creativity, yet these appear absent from the agendas of policymakers at the systems level (Weare & Nind, Citation2014, White, Citation2013, Citation2014). Despite Australian curriculum prioritisation (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, Citation2017), creativity is neglected in practice, funding, and constrained by misconceptions (Benedeck et al., Citation2021).

Creative-Being, when applied in different cultural contexts, may operate differently, with a variety of moderating factors that need to be considered. Socio-economic status may moderate different elements in the model, for instance some students experiencing higher levels of negative emotion in some districts versus others, or varying levels of psychological safety occurring in the classroom environment. Occupation might also moderate the model. For example, changing the cultural context to the Police Force or the Army where high frequency of trauma is commonplace may mean the level of negative emotion as an input into the micro-system may be more extreme than that which occurs in a classroom. This would then influence the elements of vulnerability within the model and the level of psychological safety required to promote creative flourishing. Furthermore, some workplace cultures may have high levels of psychological safety already existing, whereas others may greatly lack. Other environmental factors could also influence the effectiveness of the model, with some organisations being influenced by global elements such as COVID-19 and the financial crisis more than others. These elements could impact the levels of wellbeing as inputs into the model, the nature of psychological safety within a micro-system and the level of vulnerability willing to be experienced. Thus, depending upon the environment in which the model is applied, greater focus on specific elements may be necessary to adjust for different vulnerabilities within the system.

Implementing a grassroots systemic creativity-wellbeing model within our standard current educational environments could be challenging (Davis, Citation2017). SIPE is an emerging area, with the embracing of complexity a potential barrier. Many schools continue embedding linear compartmentalised wellbeing educational models and siloed thinking around learning (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021) despite school environmental complexity. Embedding a holistic systems model may encounter resistance, misunderstanding, or poor implementation. Models like Creative-Being, however, provide frameworks to build upon.

Yet Creative-Being also presents ways forward. Future studies testing the model and possible pilot programs may provide means for evaluating model feasibility across cultural contexts and evaluating moderating factors. Testing this model in different sectors other than education will provide further clarification of its validity and reliability. Additionally, further research of the model’s application in different education systems across the globe would also be beneficial. Such research contributes to PP by acknowledging the cultural complexities within both the constructs of wellbeing and creativity, building on existing research around the importance of cultural contextualisation within the field (Joshanloo & Weijers Citation2014 , Pedrotti et al., Citation2009, Wong, Citation2011).

Creative-Being potentially contributes to emerging SIPE research by building on simplexity (Kern & Taylor, Citation2021, Kluger, Citation2008). Creative-Being is not a single quick fix addressing wellbeing or creativity within a particular curriculum area, but rather a model whose systemic nature transcends the boundaries of subjects or developmental stages. It is complex because human systems are complex. Yet it has simple outcomes: creativity and wellbeing. Its systemic integrated nature aligns with 21st century learning across complex integrated domains. Many wellbeing models focus on wellbeing alone. Creative-Being includes multiple aspects of wellbeing and creative outputs for both individuals and the collective microsystem. Thus, Creative-Being is an important step forward for positive education.

Creative-Being may also contribute to creativity research by adding wellbeing and negative emotions into the systemic understanding of creativity. While creativity research has touched on negative emotions, no models acknowledge its potential positive transforming power to this degree. Creative-Being also builds on an existing systems model of creativity (Amabile et al., Citation2005). By explicitly integrating wellbeing and negative emotions within the systemic creative process it offers new pathways for creative systems thinking.

Conclusion

Creative-Being is a dynamic systems model designed to mutually support both creativity and wellbeing for learners. The model reflects the complexity of the school environment and human systems, yet its outcomes are simple: wellbeing and creativity. It is designed to equip learners to navigate and thrive in a complex world. Perhaps this model unleashes the possibility for Beethoven’s story of creative flourishing to be the story of every learner. Creative-Being is, therefore, a small yet decisive step in shifting positive education towards the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, K., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

- Allison, L., Waters, L., & Kern, M. L. (2020). Flourishing classrooms: Applying a systems- informed approach to positive education. Contemporary School Psychology, 25(4), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00267-8

- Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). From individual creativity to organizational innovation. In K. Grønhaug & G. Kaufmann (Eds.), Innovation: A cross-disciplinary perspective (pp. 139–166). Norwegian University Press.

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

- Amabile, T. M. (1997). Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review, 40(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165921

- Amabile, T. M., Barsade, S. G., Mueller, J. S., & Staw, B. M. (2005). Affect and creativity at work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 367–403. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.367

- Amabile, T. M., & Pillemer, J. (2012). Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.001

- Atkins, S., & Murphy, K. (1993). Reflection: A review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18(8), 1188–92. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18081188.x

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2017). General capabilities. https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). https://www.aihw.gov.au

- Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 779–806. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012815

- Beethoven, L., & Wallace, G. J. (n.d.). Beethoven’s letters (1790–1826). https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139940535.001

- Benedek, M., Karstendiek, M., Ceh, S. M., Grabner, R. H., Krammer, G., Lebuda, I., Silvia, P. J., Cotter, K. N., Li, Y., Hu, W., Martskvishvili, K., & Kaufman, J. C. (2021). Creativity myths: Prevalence and correlates of misconceptions on creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111068

- Bosworth, K., & Judkins, M. (2014). Tapping into the power of school climate to prevent bullying: One application of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947224

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Brown, B. (2013). How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and lead. Portfolio Penguin.

- Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead: Brave work, tough conversations, whole hearts. Random House.

- Campos-Gil, J. A., Ortega-Andeane, P., & Vargas, D. (2020). Children’s microsystems and their relationship to stress and executive functioning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 996. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00996

- Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The systems model of creativity: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Springer.

- Davis, S. (2017). Creativity in Australian schools suppressed by onerous testing regime and crushing teacher restrictions. EduResearch Matters. https://www.aare.edu.au/blog/?p=2266.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia and well-being: An introduction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902–006–9018–1

- Drake, M. E. (1994). Deafness, dysesthesia, depression, diarrhea, dropsy, and death: The case for sarcoidosis in Ludwig van Beethoven. Neurology, 44(3_part_1), 562–562. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.562

- Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high-quality connections. In K. Cameron & J. Dutton (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 262–278). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Du, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, X., Xie, C., Liu, C., Hu, W., & Li, Y. (2021). A positive role of negative mood on creativity: The opportunity in the crisis of the COVID-19 epidemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600837

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Estrada, C. A., Isen, A. M., & Young, M. J. (1994). Positive affect improves creative problem solving and influences reported source of practice satisfaction in physicians. Motivation and Emotion, 18(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02856470

- Fineman, M. A. (2017). Vulnerability and inevitable inequality. Oslo Law Review, 4(3), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2387-3299-2017-03-02

- Forgeard, M. J. C., Jayawickreme, E., Kern, M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v1i1.15

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.218

- Frijda, N. H. (1993). Moods, emotion episodes, and emotions. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 381–403). Guilford Press.

- Gale, C. R., Booth, T., Mõttus, R., Kuh, D., & Deary, I. J. (2013). Neuroticism and Extraversion in Youth Predict Mental Wellbeing and Life Satisfaction 40 Years Later. Journal of Personality, 47(6), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.06.005

- George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.687

- Goleman, D., & Senge, P. (2014). The triple focus: A new approach to education. More than Sound.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063487

- Harrington, R., & Loffredo, D. (2011). Insight, rumination, and self-reflection as predictors of well-being. The Journal of Psychology, 145(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.528072

- Higgins, M., Dobrow, S. R., Weiner, J. M., & Liu, H. (2020). When is psychological safety helpful? A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Discoveries, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2018.0242

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

- Ingram, R. E. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 156–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.156

- Isen, A. M. (1999). Positive affect. In T. Dalgleish & M. J. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 521–539). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013494.ch25

- Isen, A. M., & Daubman, K. A. (1984). The influence of affect on categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1206–1217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1206

- Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1122–1131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1122

- Jamison, K. R. (1989). Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry, 52(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1989.11024436

- Jayawickreme, E., Forgeard, M. J. C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). The engine of well-being. Review of General Psychology, 16(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027990

- Joshanloo, M., & Weijers, D. (2014). Aversion to happiness across cultures: A review of where and why people are averse to happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9

- Kashdan, T. B., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2015). The power of negative emotion: How anger, guilt and self-doubt are essential to success and fulfilment. Oneworld.

- Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2002). Could Steven Spielberg manage the Yankees? Creative thinking in different domains. Korean Journal of Thinking & Problem Solving, 12(2), 5–14.

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Creativity in the schools: A rapidly developing area of positive psychology. In R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, & M. J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 175–188). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kern, M. L., & Taylor, J. A. (2021). Systems informed positive education. In M. L. Kern & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 109–135). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_5

- Kern, M. L., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2021). Introduction and overview. In M. L. Kern & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 109–135). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3

- Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

- Kern, M. L. Williams, P. Spong, C. Colla, R. Sharma, K. Downie, A. Taylor, J. A. Sharp, S. Siokou, C. & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

- Kluger, J. (2008). Simplexity: The simple rules of a complex world. Hyperion Press.

- Kuo, H. (2011). Toward a synthesis framework for the study of creativity in education: An initial attempt. Educate, 11(1). http://www.educatejournal.org/index.php/educate/article/view/287

- Lazarus, R. S., & Cohen-Charash, Y. (2001). Discrete emotions in organizational life. In R. L. Payne & G. L. Cooper (Eds.), Emotions at work: Theory, research and applications for management (pp. 45–81). John Wiley & Sons.

- Liu, X., Gong, S.-Y., Zhang, H., Yu, Q., & Zhou, Z. (2021). Perceived teacher support and creative self-efficacy: The mediating roles of autonomous motivation and achievement emotions in Chinese junior high school students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 39, 100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100752

- Livingston, J. A. (1999). Something old and something new: Love, creativity, and the enduring relationship. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 63(1), 40–52.

- Lomas, T. (2016a). Positive art: Artistic expression and appreciation as an exemplary vehicle for flourishing. Review of General Psychology, 20(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000073

- Lomas, T. (2016b). The positive power of negative emotions: How harnessing your darker feelings can help you see a brighter dawn. Piatkus.

- Lomas, T., & Ivtzan, I. (2016). Second wave positive psychology: Exploring the positive–negative dialectics of wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1753–1768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9668-y

- Lomas, T., Waters, L., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Kern, M. L. (2020). Third wave positive psychology: Broadening towards complexity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(5), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501

- Martin, L. L., Ward, D. W., Achee, J. W., & Wyer, R. S. (1993). Mood as input: People have to interpret the motivational implications of their moods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.317

- Maxwell, L. E. (2010). Chaos outside the home: The school environment. In G. W. Evans & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Chaos and its influence on children’s development: An ecological perspective (pp. 83–95). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12057-006

- Maxwell, L. E. (2016). School building condition, social climate, student attendance and academic achievement: A mediation model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 46, 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.009

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Morin, A. (2011). Self-awareness part 1: Definition, measures, effects, functions, and antecedents. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(10), 807–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00387.x

- National Institute of Education. (2017). NIE teacher education model for the 21st century. https://www.nie.edu.sg/te21/index.html

- Oades, L., & Mossman, L. (2017). The science of wellbeing and positive psychology. In M. Slade, L. Oades, & A. Jarden (Eds.), Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (pp. 7–23). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339275.003

- OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- Pedrotti, J., Edwards, L., & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Positive psychology within a cultural context. College of Education Faculty Research and Publications, 429. https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/429

- Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_1

- Primary School, N. (2021, October 24). Marking education meaningful. https://www.newmark.vic.edu.au

- Robinson, K. (2006). Do schools kill creativity? http://www.Ted.Com/Talks/Ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity.

- Rowe, A. D., & Fitness, J. (2018). Understanding the role of negative emotions in adult learning and achievement: A social functional perspective. Behavioural Sciences, 8(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8020027

- Rusk, R., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2017). A complex dynamic systems approach to lasting positive change: The synergistic change model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1291853

- Ryan, P. (2009). Integrated theory of health behavior change: Background and intervention development. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 23(3), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Schleicher, A. (2018). Educating learners for their future, not our past. ECNU Review of Education, 1(1), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.30926/ecnuroe2018010104

- Schwarz, N. (1990). Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (Vol. 2, pp. 527–561). The Guilford Press.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well- being. Atria Paperback.

- Senge, P. M., Cambron McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., & Dutton, J. (2012). Schools that learn: A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. Currency.

- Smith, J., & Alloy, L. B. (2009). A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualization of this multifaceted construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 116–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.003

- Spiel, C., & von Korff, C. (1998). Implicit theories of creativity: The conceptions of politicians, scientists, artists and schoolteachers. High Ability Studies, 9(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359813980090104

- Takano, K., & Tanno, Y. (2009). Self-rumination, self-reflection, and depression: Self- rumination counteracts the adaptive effect of self-reflection. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.008

- Tan, O. S. (2015). Flourishing creativity: Education in an age of wonder. Asia Pacific Educational Review, 16(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9377-6

- Tan, C.-Y., Chuah, C.-Q., Lee, S.-T., & Tan, C.-S. (2021). Being creative makes you happier: The positive effect of creativity on subjective well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147244

- Terr, L. C. (1992). Mini-marathon groups: Psychological first aid following disasters. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 56, 76–86. 1

- Thomson, S. (2020, August) TALIS: Stress levels among Australian teachers. Teacher. https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/columnists/sue-thomson/talis-stress-levels-among-australian-teachers

- Torrance, E. P. (1981). Predicting the creativity of elementary school children (1958-80) —and the teacher who made a difference. Gifted Child Quarterly, 25(2), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/001698628102500203

- Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.284

- Turner, K., & Thielking, M. (2019). How Teachers Find Meaning in their Work and Effects on their Pedagogical Practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(9), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2019v44n9.5

- United Nations. (2019). Sustainable development goals. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html

- Verhaeghen, P., Joormann, J., & Aikman, S. N. (2014). Creativity, mood, and the examined life: Self-reflective rumination boosts creativity, brooding breeds dysphoria. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035594

- Verhaeghen, P., Joormann, J., & Khan, R. (2005). Why we sing the blues: The relation between self-reflective rumination, mood, and creativity. Emotion, 5(2), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.226

- Vougioukalou, S., Dow, R., Bradshaw, L., & Pallant, T. (2019). Wellbeing and integration through community music: The role of improvisation in a music group of refugees, asylum seekers and local community members. Contemporary Music Review, 38(5), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2019.1684075

- Wanless, S. B. (2016). The role of psychological safety in human development. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141283

- Weare, K., & Nind, M. (2014). Promoting mental health and well-being in schools. In F. Huppert & C. Cooper (Eds.), Interventions and policies to enhance well-being (Vol. VI, pp. 93–140). Wiley.

- Weisberg, R. W. (1988). Problem solving and creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives (pp. 148–176). Cambridge University Press.

- White, M. (2013). Positive education at geelong grammar school. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. Ayers (Eds.), The oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 657–670). Oxford University Press.

- White, M. (2014). An evidence-based whole school strategy to positive education. In H. Street & N. Porter (Eds.), Better than OK: Helping young people to flourish at school and beyond (pp. 194–198). Fremantle Press.

- White, M. A. (2016). Why won’t it stick? Positive psychology and positive education. Psychology of Well-Being, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-016-0039-1

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- World Health Organization. (2001). The world health report 2001: Mental health: New understanding, new hope.