ABSTRACT

Positive psychology has had an impressive first 25 years. However, it and related wellbeing sciences are at risk of being rendered futile at a time of staggering crises across psychological, social, political, and environmental domains. This paper is a call for a new science of wellbeing, a Regenerative Positive Psychology, that reorients the field toward protecting and expanding the growth and health of the life-sustaining systems necessary for our wellbeing. This paper asks whether life has improved significantly since the launch of positive psychology, appraises the field’s disproportionate emphasis on individual wellbeing, describes regenerative approaches in other fields, and proposes Three Pillars for a Regenerative Positive Psychology that is better equipped to take on the daunting challenges ahead. As fields rooted in strengths, hope, and purpose, positive psychology together with wellbeing sciences are ideally suited to take greater leadership in facing the world’s crises and building more positive futures for all.

In the 1998 Presidential Address to the American Psychological Association, Martin Seligman called for psychology to take a larger role in two areas. The first was ethnic conflicts and the second was positive psychology (PP), or ‘a reoriented science that emphasizes the understanding and building of the most positive qualities of an individual’ (The APA Citation1998 Annual Report, Citation1999). The strength of psychology’s response to ethnic conflict might be doubted, but the productivity and energy directed toward the ‘positive qualities of the individual’ has been impressive. We might deservedly celebrate the achievements of the first 25 years of PP’s reorientation of psychological science. However, this article presents an urgent call for positive psychology itself to be reoriented, joining others who have seen a pressing need for PP to transform (e.g. Kern et al., Citation2020, Wissing et al., Citation2022; Lomas, Citation2015; Lomas et al., Citation2021; Wissing, Citation2022). In ways that vitally matter, this time of ever-mounting crisis and confusion suggests that PP has fallen short. So far. Therefore, the goal of this paper is to argue that this young field focused on the excellent individual is inadequate in the face of realities and challenges confronting us, and without another reorientation any successes of PP risk irrelevance and futility.

The central claim of this paper is that we need a call for a new PP, perhaps a new psychology in general, that is responsive and helpful in the current context. I call this new evolution of our field, Regenerative Positive Psychology. I will argue that PP – inclusive of associated fields such as optimal functioning, flourishing, happiness, and wellbeing studies – is outmatched as currently construed. The scale of crises facing people, indeed life, across the globe, and the sheer magnitude and alacrity with which epochal transformations seemingly must be executed in response, threaten to make a mockery of all we have devoted our careers and efforts to. This article was written mainly with the climate and environmental crisis serving as an example, with particular awareness of the fact that our collective selves have both known about and done nothing about the need for change decade after decade. However, many other challenges exist that seem inclined to make the pursuit of individual happiness increasingly difficult and untenable. In fact, there are so many crises that simply listing a few of the most notable feels like a bullying rhetorical ploy. Nonetheless, in addition to our acute climate and environmental crisis we also confront such calamities as the accelerated rise of artificial intelligence, the specter of global pandemics, chemical and plastic pollution, the Anthropocene extinction, political upheaval and divisiveness, erosion of civil freedom and human rights, misinformation and propaganda campaigns transmitted both on macro and personal scales, and a global oligarchy flexing muscles swollen by mounting wealth disparities.

Instead of a psychology of individual human excellence and wellbeing, crises like these need a science of collective systemic wellbeing that prioritizes the aim of restoring and healing the systems – all the systems – that sustain and provide life.

In his initial address, Seligman alluded to a somewhat dystopic future should psychology fail to reorient to a science of human excellence: ‘Standing alone on the pinnacle of economic and political leadership, the United States can continue to increase its material wealth while ignoring the human needs of our people and of the people on the rest of the planet. Such a course is likely to lead to increasing selfishness, alienation between the more and the less fortunate, and eventually to chaos and despair’ (emphasis added; The APA Citation1998 Annual Report, Citation1999). Try reading that sentence again without thinking of your daily newsfeed. Has PP failed, then, to reorient psychology? I would argue that we have arrived at this grim, oft-foretold future not because PP failed to reorient the field, but because we now need a more robust reorientation that truly reflects the scope of ‘human needs’ beyond the merely psychological. This paper will aim to show that despite the impressive uptake and impact of PP so far, (a) those impacts have not necessarily extended beyond some metrics of individual wellbeing. I will argue that perhaps this is because (b) the field is marked by an overemphasis on individual wellbeing as the unit of analysis, (c) which should be reoriented to a broader-scoped Regenerative Positive Psychology (RPP). I will then (d) set the context for RPP and (e) propose an alternative three pillars for our field’s next stage.

The impact of positive psychology

Whether marked by numbers of bestselling books, university courses, journals, or research articles, attention to PP and its constellation of topics has skyrocketed. The fact that it is a field with terminal degrees and journals with respectable impact factors provides accompanying proof of scholarly impact. I would argue that another impact of PP is the formation of implicit social contract that by studying and disseminating tools for positivity, we would contribute to happier lives and a better world. Perhaps fueled by our field’s Aristotelian assumption that happiness (or your preferred construct of choice) is the highest good for human life, we signal a collective expertise in delivering the happier life that people seek, or at least happiness as a tool to obtain other outcomes we value more highly. We publish papers on how happiness, positive emotions, and other PP staples lead to desirable outcomes, such as success (Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005), wealth (DeNeve & Oswald, Citation2012), altruism/generosity (Boenigk & Mayr, Citation2016), and longevity (Diener & Chan, Citation2011), as well as good business outcomes (DiMaria et al., Citation2020). Research in PP and related wellbeing sciences frequently justify focusing on PP constructs with the precise argument that is a potentially transformative part of a better life for individuals and humanity. PP as a field, and those whose work might be said to fall within the umbrella of PP, may not uniformly or explicitly make such promises, but such promises seem to have been inferred by the broader populace. People do not look to experts in PP simply for basic scientific definitions and nomological networks among constructs, they also want research-based information on having a better life. Thus, in addition to gauging our impact in direct terms of whether people are happier now, two decades later, we might appraise whether any additional happiness has fulfilled the implicit social contract of secondary impacts such as better health, longevity, kindness, success, and environmental and economic improvements. In our research and practice of PP, we might hope we contributed to a better world. But did we?

The broader impact of positive psychology?

To suggest answers to these concerns, data will be presented spanning a period of time starting as near as possible to the founding of PP in 1998 and the present in 2023. For each of a range of wellbeing indicators, inputs, and outputs, I only focused on those for which there were multiple years and multiple continents represented. The figures presented below were generated through The World in DataFootnote1 and are not intended to provide definitive review of each topical area. They are presented simply to scrutinize the idea that PP – so far – has succeeded in its primary aims or its secondary implicit social contract. We will start with the low-hanging fruit for our field, happiness.

Are people happier? Indicators of happiness

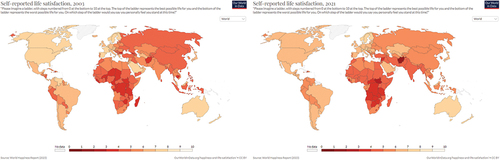

Large scale surveys frequently ask people to rate their life satisfaction or happiness. And while wellbeing is not simply the reverse of illbeing, I will supplement a portrayal of whether people are happier with global data on psychopathology, providing a complementary view. Below, we can see that life satisfaction is a mixed bag (), with some countries looking more satisfied and others less satisfied than they were in 2003.

In contrast, when asked about happiness, it looks like more of the world is happier than before ().

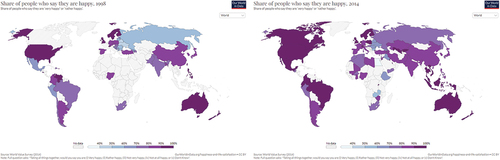

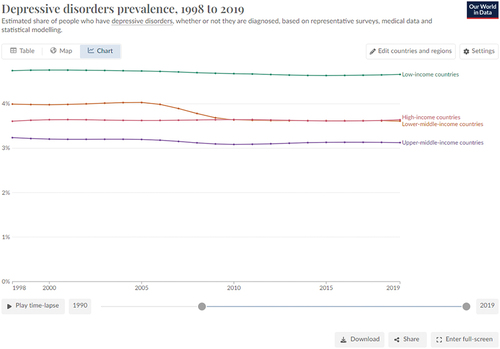

The world also looks slightly less depressed (), with this slight decline in depression prevalence in recent years primarily led by improvements reported by lower-middle-income countries.

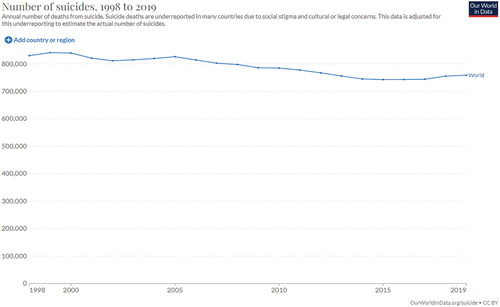

And global suicide rates around the world have decreased (). Proportionate to the world’s population in 1999 (~6 billion) and 2019 (more than 8 billion), this is more impressive on a per capita basis than the graph conveys.

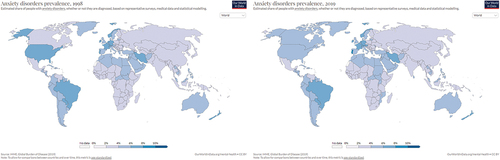

However, the world is slightly more anxious than it was ().

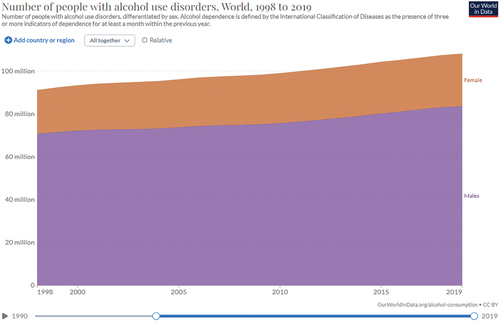

And rates of alcohol use disorders have climbed ().

The short answer to the question of whether people are happier since the start of PP is, ‘probably somewhat better, or maybe a little bit worse, depending on how you measure it’. We might feel that PP has perhaps impacted its primary aim of human happiness, though modestly so. This might stoke our optimism should we heed a call for a Regenerative Positive Psychology to directly tackle larger problems.

Are the sources of happiness increasing? Happiness inputs

In this section, we look at data that index some of the systemic factors linked to happiness around the world, such as living in stable, democratic, and free societies (e.g. Veenhoven, Citation2009) that can provide basic necessities.

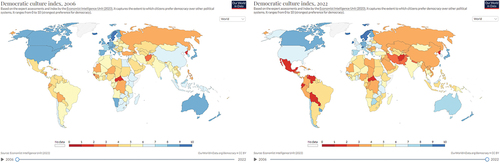

There are fewer countries showing a preference for democratic government now ().

Figure 7. Democratic culture index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit shows preference for various forms of government, 2006–2023. Dark blue denotes strong preference for democracy, dark red denotes strong preference for nondemocratic government.

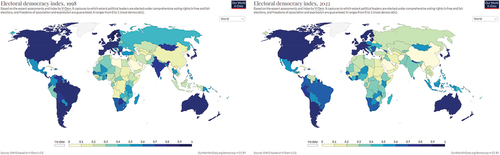

And high-quality democratic elections are rarer ().

Figure 8. Electoral democracy index by V-Dem in which darker colors denote free, fair elections conducted under comprehensive voting rights, 1998–2022.

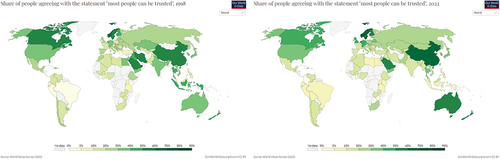

There are mixed results for agreement that most people can be trusted, with some countries feeling more trustful and others feeling less trustful ().

Figure 9. Darker colors denote greater percentage of people agreeing with statement ‘most people can be trusted’1998–2022.

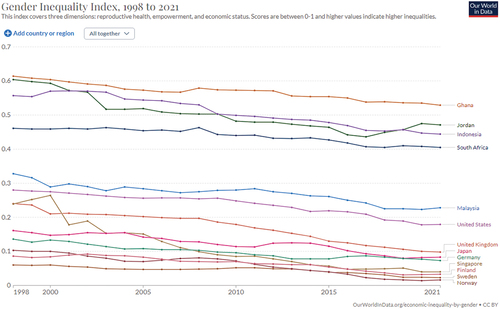

Perhaps existing increases in trust could be linked to widespread improvements to gender inequality, as illustrated in .

Figure 10. Gender inequality as indexed by reproductive health, empowerment, and economic status among available countries, 1998–2021. Lower values indicate less inequality.

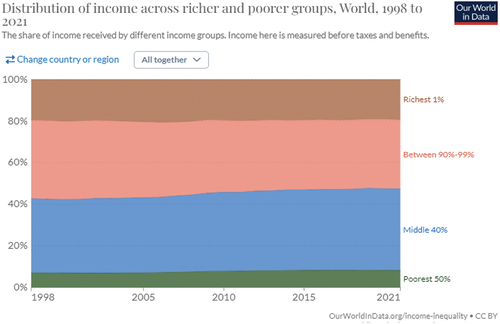

Wealth disparities around the world have seen modest improvements as the global middle class has grown, while the richest 10% still possess more than half of the world’s wealth. ().

Figure 11. Share of income received by the poorest 50%, middle 40%, next highest 9%, and highest 1% of wealthy aggregated for the entire world from 1998 to 2021.

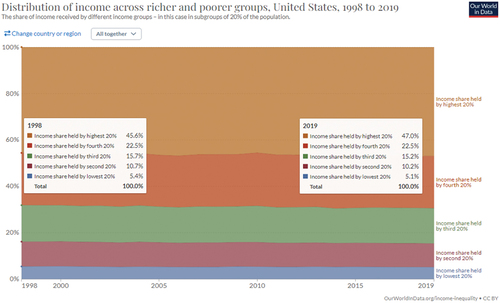

Global equalization was not seen in the United States, PP’s birthplace, where the richest 20% got a little richer and the bottom 60% got a little poorer ().

Figure 12. Share of income received by wealth quintiles in the United States of America from 1998 to 2019.

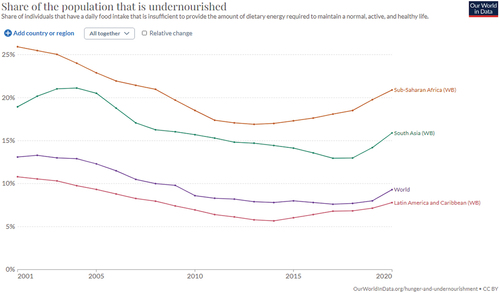

Finally, except for a reversal in the most recent years, malnourishment has declined during the time of PP ().

Figure 13. Percent of people who receive food intake that provides insufficient energy to maintain a healthy life from 2001–2020.

So, if stable, democratic, and free societies that provide basic necessities to their populace create more fertile conditions for happiness, there are both causes for trepidation (democracy) and optimism (gender inequality, malnourishment).

Is the world a better place? Happiness outputs

Positioning systemic variables as inputs or outputs is arbitrary. For example, wellbeing is negatively related to materialism (e.g. Dittmar et al., Citation2014) and positively related to nature relatedness (e.g. Nisbet et al., Citation2011), so it could be argued that wealth disparity is an output of happiness and environmental health is an input. Certainly, as ecological and climatological disasters proliferate, the environment seems likely to be an influential future driver of wellbeing. However in this section, the focus is on whether humans have altered their activities enough to benefit the environment. Without an environment that can sustain life, all other assumptions about the good life will be fundamentally senseless. A guiding assumption here is that a new reorientation of PP must step up to the challenge of remediating the huge problems in the world, such as climate and ecological crises.

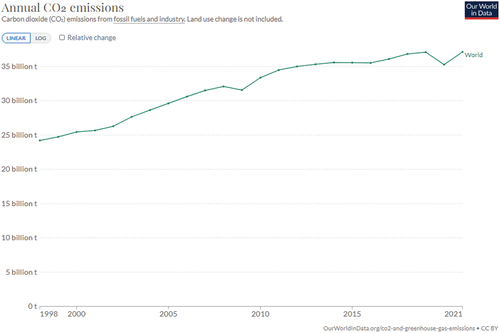

Unfortunately, carbon emissions from the fossil fuel industry continue to escalate ().

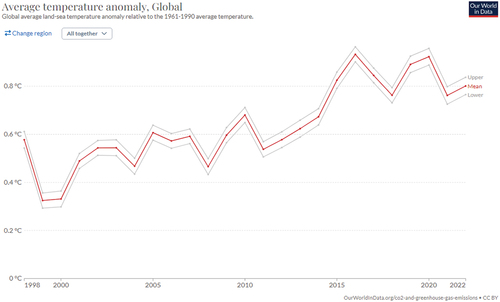

As do temperatures ().

Figure 15. Average global temperature measured in degrees above historical, normal temperatures, 1998–2022.

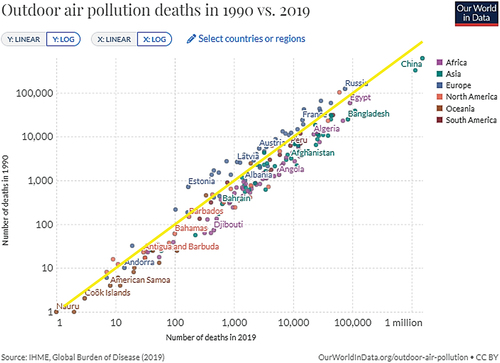

And most of the countries in the world have seen more people die of air pollution (below the diagonal) since the beginning of PP ().

Figure 16. Number of deaths due to air pollution in 1990 and 2019. Countries to the lower-right of the yellow diagonal have experienced more deaths in 2019 than in 1990.

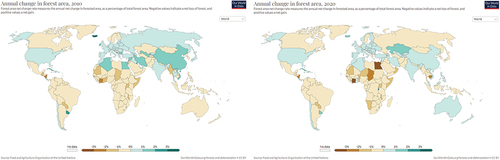

These next images show change in deforestation relative to the previous year (), with tan and brown being higher rates of deforestation than the previous year, and blue being lower rates of deforestation than the previous year. These charts are difficult to compare without each year included, but given the emphasis on forests as one of the great land-based bastions against global heating we should hope to see the entire map in green. It is discouraging to see even more countries with annually increased deforestation rates in 2020 than in 2010.

Figure 17. Annual change in forest area in 2010 (compared to 2009) and 2020 (compared to 2019). Deforestation is denoted in tan and darker brown, increase in forest area is denoted in light green.

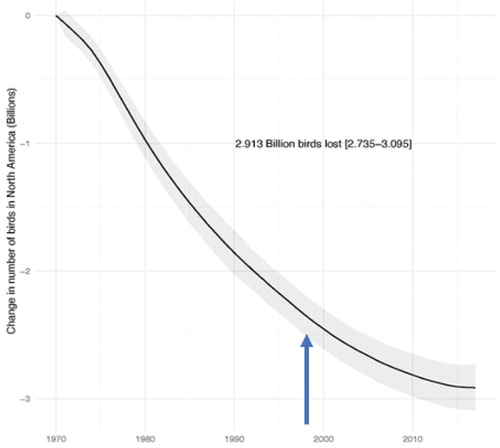

With loss of habitat and worsening atmospheric conditions, we should be saddened but not surprised to see astonishing losses in birds in North America ().

Figure 18. Decline in bird populations in North America from 1970–2018, blue arrow indicates 1998. Estimated 2.9 billion fewer birds alive today than in 1970, a loss of 29% (Rosenberg et al., Citation2019) Credit: Adam Smith.

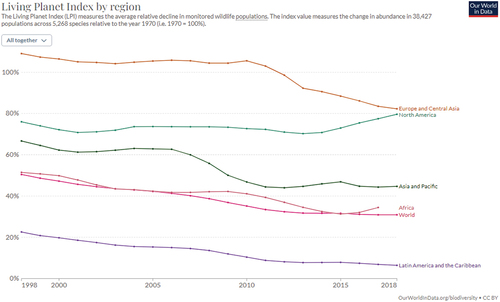

These depressing numbers are joined by deflating values since the beginning of PP on each continent for the Living Planet Index. As the graph falls, so too do the numbers of living wildlife on the planet (Figure 19).

To be clear, PP did not set out to secure healthy air, protect animals and forests, or reverse global heating. Positive psychology set out to better understand human wellbeing and disseminate that knowledge in ways that improve wellbeing via individual characteristics and practices and institutions. Not everything about the world is worse, and the world as a whole may be a little happier and less depressed than it was in 1998. However, there is little sustaining the idea that happier people make for a better world. At minimum, this conclusion challenges the utility of PP-as-usual much beyond helping people feel themselves to be happier. If happiness does little tangible good, why ought we work so hard to promote it? This interpretation may feel disappointing. It ought to prompt questions over whether we are really serving people and life around the world, and if not, why not?

Even if we keep to our current core competencies, the limitations of our field are apparent. Say we decide that it is not our field’s business to improve the world, are we up to the task of improving individual wellbeing in such a world? Have we generated a scientifically-based set of practices strong enough to overcome the negative impacts of even one of our many looming challenges? Do we feel that using strengths, engaging flow, or practicing mindfulness can pace with the ambient stress and harm that comes from political, economic, humanitarian, pollution, extinction, or climate crises?

Perhaps a thought experiment can illustrate these matters. Finland commonly is awarded the designation as happiest country in the world. Consider another European country that borders Russia. Can any of us imagine that happiness would persist unblemished if instead of Ukraine, Russia had invaded Finland? If, instead of Maldives and Palau sinking beneath rising seas, it was Finland? If, instead of illegal destruction of forests and displacement of indigenous peoples in Brazil skyrocketing since 2013 (Silva-Junior et al., Citation2023), it was Finland’s forests and the Sami lands? If, instead of democratic governance, an authoritarian takeover had begun? And if any or all of that happened, do we possess powerful enough evidence-based practices as a field to restore wellbeing to Finland? I feel we do not, and I suspect that most positive psychologists would doubt this, too.

The irony is that PP has attracted the energies and efforts of inspiring, hard-working, optimistic, passionate, and purposeful people around the world. It is a field focused on science, solutions, and dissemination. It ought to be the ideal field to lead a major shift toward understanding and working to nurture a broader idea of wellbeing that embraces both our individual human experience and the vitality of life-sustaining systems around us. Have we risen to that challenge of pursuing an expansive view of wellbeing or have we locked in on only one component?

Individual wellbeing as the unit of focus

The field of positive psychology at the subjective level is about valued subjective experiences: well-being, contentment, and satisfaction (in the past); hope and optimism (for the future); and flow and happiness (in the present). At the individual level, it is about positive individual traits: the capacity for love and vocation, courage, interpersonal skill, aesthetic sensibility, perseverance, forgiveness, originality, future mindedness, spirituality, high talent, and wisdom. At the group level, it is about the civic virtues and the institutions that move individuals toward better citizenship: responsibility, nurturance, altruism, civility, moderation, tolerance, and work ethic. (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2000, p. 5, emphasis added)

This extended quote marks PP’s public debut and gives us the three pillars of positive psychology. These are reprised toward the end of Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi’s seminal article as positive experience, positive personality, and positive communities and institutions. People’s contexts were explicitly acknowledged in the beginnings of PP. Yet, there has been a persistent tendency to focus on the isolated individual as the primary actor (Lomas, Citation2015). A review of PP research published from 1999–2013 identified 771 empirical articles (Donaldson et al., Citation2015). Of these 339 focused on wellbeing, followed by 70 on character strengths, 63 on hope, 41 on gratitude, 39 on resilience, 34 on growth, and 31 on individual performance. Even if we (probably erroneously) assumed that every other empirical article focused on group-level, collective, or contextual factors, no fewer than 617 of the empirical articles on PP, or 80%, focused on individual-level outcomes.

Even when the focus is broadened somewhat to consider contexts, the individual is still usually elevated. For example, positive relationships, positive work organizations, and acts of altruism and helping behaviors would each seem suited to working toward collective solutions. However, most research and interventions I am aware of are targeted at the individual’s reports on experiences or traits. Even when a nominally relational or contextual variable is in focus, the individual as actor or judge is elevated to primacy. Is an individual satisfied with a relationship? If yes, that is a positive relationship. Is an individual experiencing happiness or meaning at work? If yes, then that is a positive work organization. Is an individual reporting volunteering, making charitable contributions, or emitting observable helping behavior? If yes, then that is altruism and kindness. There are exceptions to this sweeping characterization of course, but the impression lingers that PP is mostly concerned with the individual. Quantification of this imbalance (e.g. through metaanalyses of various research domains, cf. Donaldson et al., Citation2015) is beyond the scope of this article, but to better support this claim, I will instead suggest a proxy: The most cited articles in the Journal of Positive Psychology (JOPP).

Most cited articles in the journal of positive psychology

The most cited articles from the JOPP as calculated by Web of Science provided a metric of what those who publish in academic journals are most frequently citing to build their own research articles. Thus, it can provide some indication of what researchers in the field are reading and using.

The top 50 most-cited articles in JOPP had 105 to 1,099 citations (as of 15 May 2023). Each article was appraised for the degree of individual-centeredness of the thematic variables, putative causal variables, or putative outcome variables, regardless of method used. Of the 50 articles, 100% minimally included the individual’s own experience as the focal point of either the thematic variable (e.g. meaning in life), the putative causal variable (e.g. humility), or the putative outcome variable (e.g. resilience). For 96%, the individual was the only focus. Two articles hinted at broader contextual factors. The first was a study of teacher grit and life satisfaction as causes of student academic gains (Duckworth et al., Citation2009). While student grades are an individual-level variable, it could be argued that the overall emphasis is on a collective success outcome, school quality. This article highlights one of the most contextual research traditions in PP, positive schools and organizations. In much the same way that Duckworth and colleagues hint at better-functioning schools vis-à-vis individual-level inputs and outputs that are aggregated, research on healthy workplaces also frequently builds arguments on individual-level variables (e.g. leadership, available resources, character strengths) to suggest at the quality of the collective entity (e.g. greater proportion of engaged workers, higher aggregated meaningful work scores). Still, even if every JOPP paper concerned the aggregation of individual-level variables to estimate the quality of organizations, we would not learn much about how PP faces up to broader contextual factors like climate change.

The second not-so-individualistic paper was explicitly directed at one such contextual disaster. It was a review paper providing what PP suggested about coping with the global COVID-19 pandemic (Waters, Algoe, et al., Citation2022). Here, the focus was on individual level outcomes, but at least a collective contextual factor was being considered (and a less-cited partner paper explicitly focused on the collective level, cf. Waters, Cameron, et al., Citation2022). There was no discernable emphasis on harnessing PP to reduce the likelihood of future pandemics or to ameliorate the social and political tensions that arose in many parts of the world during the COVID response. But, with some stretching of criteria, perhaps as many as 4% of the most-cited papers in JOPP included some collective or contextual framing.Footnote2

Sobering conclusions about positive psychology-as-usual

If PP originally was to have three pillars, it is disconcerting how imbalanced research attention has been toward the two individualistic pillars, subjective experiences and traits. This criticism has been raised by other scholars (Christopher & Hickinbottom, Citation2008; Lomas et al., Citation2021). My analysis presented here shows that PP is not spontaneously turning its methods, knowledge, and talents toward having anything to say about the broader context of crises and building disasters our world confronts.

Collectively, we get the sense that we are effective in our work to increase wellbeing, excellence, happiness, resilience, etc. Indeed, there are studies of coaching interventions (Grant et al., Citation2009) PP interventions (Seligman et al., Citation2005), and organizational interventions (e.g. Cameron et al., Citation2011) that show improvements among those who participate. Yet, the world is not resoundingly happier, life is not better for many, and the systems we draw from for our wellbeing are under ratcheting pressure. Even if we assume that our work has made people happier, and that those happier people are making a positive difference in solving the world’s crises, we must conclude that it has not been enough. It might be possible that our effects are too subtle, even among those we reach. Are we really creating meaningful transformation and growth in those we work with? Are we tangibly improving their mood, their spirit, their capacities to love and heal others, to become steady caretakers of society, civilization, and our planet? And, even if we are having this kind of impact on some people, are we impacting enough?

It is as if we are earnestly working beside each other in a sprawling garden, tending carefully to the small plots within reach, while wildfires, tornados, floods, and enraged mobs decimate acre after acre, hectare after hectare at the garden’s edges, ever approaching our isolated, fragile plants.

Everything else is an input, with infinite capacity

Part of the problem, I believe, is a corollary of the nearly monocular focus on individual-level wellbeing, and that is the tendency to treat everything else as infinitely abundant inputs to wellbeing. This is widespread, though not absolute. Three examples illustrate this point. At the beginning of PP, gratitude was one of a few dominant concepts, well represented in publications and interventions (e.g. three good things, Seligman et al., Citation2005). Now, 20 years later, the topics of awe, and nature connectedness or relatedness seem to be gaining popularity. Each of these is definitionally about some qualities of the external world.

In the case of gratitude, we point people toward the value of acknowledging with appreciation the perhaps undeserved benefits bestowed by some entity outside of ourselves (Emmons & McCullough, Citation2003). It might make sense to be more nurturing of that which people appreciate, but communication about gratitude is rarely accompanied by any such sense of responsibility. Instead, the pervasive guidance about gratitude appears to be that there are boons out there and we feel happier if we notice and like what they do for us. I think of a grateful parent sending a thank you note to their child’s teacher, who may receive this note while besieged by outrage over what and how they should teach, dwindling funding, and active shooter lockdown drills. That is, gratitude-as-usual is great for the person receiving benefits from some entity, but what does it do to safeguard or restore that entity?

Awe is defined as an emotion that occurs when we encounter a stimulus that impresses us with its vastness while also forcing us to cognitively accommodate to this extraordinary experience (Keltner & Haidt, Citation2003). Awe was highlighted as an interesting topic at the beginning of PP, but research has picked up in earnest only recently. Among the most common ways of researching awe is to present research participants with videos of the natural world (Graziosi & Yaden, Citation2019) – envision a timelapse movie of Yosemite National Park from gentle dawn to twinkling starlight. Generally, awe is seen as good for wellbeing (Rudd et al., Citation2012), and at least there is some research showing that awe might prompt people to be more prosocial (Piff & Moskowitz, Citation2018). However, despite depending on the external world, and often nature, there is scant accompanying consideration of preserving or restoring those awe-inspiring natural entities. Again, awe-as-usual is about a cool kind of noticing and appreciating things that makes us feel good, whether we allow the destruction of those things or not.

Finally, even in research most applicable to environmental concerns, nature connectedness or relatedness, we recognize this emphasis on external entities as mere inputs to the more highly revered individual wellbeing. Nature connectedness or relatedness refers to a person’s emotional, cognitive, and experiential relationship with the natural world (Nisbet et al., Citation2009). As with inter-human relationships, these perceived relationships with nature are good for our physical health and wellbeing (Nisbet et al., Citation2011). Although there are several studies, often from within environmental sciences, looking at how nature relatedness may provoke people toward more ecological behavior (e.g. Nisbet et al., Citation2009), a cursory scan of popular media coverage, PP textbooks, and even a count of chapters in the leading handbook of environmental psychology and quality of life (Fleury-Bahi et al., Citation2017) suggests an overabundance of emphasis on nature as an input to human wellbeing. Even nature relatedness-as-usual is at risk of boiling down to benefits extracted from nature without regard to its health or survival.

When we appreciate, feel in awe of, and perceive connection to the glories of the world around us, we feel happy. But what are we doing to preserve and restore these sources of wellbeing? It is hard to escape the sense that we are harvesting happiness from dwindling stocks, and when they are depleted, we will move on to the next source and exhaust that, too. I suppose then, we positive psychologists someday will help people savor what is still present rather than what has been lost, help people build resilience to a future of such losses, and perhaps in the worst case we will help people feel thankful, awed, and connected to videos of our lost world streamed to our survival bunkers. Is it possible that our focus on individual wellbeing has inadvertently caused us to neglect our potential role, and arguably our responsibility, to document, understand, and protect the entities and systems that fundamentally foster wellbeing?

Regenerative positive psychology

It is the contention of this paper that we cannot simply continue to minister to individuals as if our interventions and encouragements can withstand the shockwaves of global crises, nor can we work fast enough or with vast enough reach to aid the recovery of each individual damaged by crisis. If we acknowledge such a statement, then we must confront the idea that we are outmatched, that our profession as currently constituted is failing to compensate for a bigger flaw in how we collectively live our lives. Capitulation is not an option; not only because the alternative is bleak, but because we are intelligent and innovative, solution- and strength-focused, Our response must be to reorient our field and elevate its sights to make life better not just for individuals, but for everything. A Regenerative Positive Psychology is urgently needed.

To outline a Regenerative Positive Psychology, we might begin with the ancient thinkers, both hedonic (e.g. Epicurus) and eudaimonic (e.g. Aristotle), who argued that happiness flourishes in moderation. Has PP succeeded in promoting a view of happiness that balances hedonic reward with eudaimonic responsibility, virtue, and future-mindedness so that modern humans behave with moderation? Well, no. We show all signs of excess. Much has been made about how modern economic and technological traditions have improved life for unprecedented myriads of people (e.g. Pinker, Citation2012). But recently, such self-congratulations have been accompanied by growing realization of the costs of our uplift.

That is, to achieve gains in human health and wealth, each of us uses more of the resources available on our planet than can be replenished. Traditional approaches-as-usual use more land, more energy, more trees, more fish and animal bodies, more fresh water, more clean air, more minerals, more carbon, more arable soil, even more sand and more geostationary orbital space than can be made or cleaned up. We collectively overshoot the Earth’s carrying capacity by 171%. To sustain our current lifestyles, we would need 1.71 Planet Earths (Footprint Data Foundation, Citation2022). The celebrated consumption spree that uplifted so many billions has racked up debts that will press down many more generations of billions to come.

Sustainability

This is the concern that sustainability approaches have tried to address. Sustainability approaches seek balance between extraction and replenishment. That is, each of us only takes or spoils resources equal to what can be restored or cleaned so there hopefully will be enough for future people. To compare approaches-as-usual with sustainability approaches, the former continues accelerating whatever overdraft of existing resources already exists, the latter seeks to hold steady at current levels of consumption and not increase them.

The obvious problem is that sustaining current consumption levels means consuming 1.71 Earths worth of stuff, which would eventually deplete the Earth and render future living conditions unrecognizable. Sustainability is not sustainable. But should PP care about big problems like whether life on Earth is tenable, or should we keep trying to boost the happiness of individuals today? Put another way, should we maintain focus on individual wellbeing outcomes, or should we expand our view to also consider the viability of wellbeing inputs, such as a livable Earth?

A central assumption of this article is that in positive-psychology-as-usual we are systematically ignoring key drivers of wellbeing, and doing little to nothing to help preserve or regenerate them. In a sense, we, too, may be consuming 1.71 Earth’s worth of ‘wellbeing resources’ without acting to ensure those resources will persist (e.g. stable and safe societies, beautiful nature, drinkable water). PP is not accustomed to opining about global lifestyles in terms of resource consumption. We ought to change that, and we ought to do something positive about it.

Is positive psychology an approach-as-usual or sustainable?

It seems worth asking whether PP itself is sustainable, or whether it is an extractive, traditional venture. That is, as PP goes about its research, teaching, consulting, coaching, clinical and organizational work, and public dissemination, is it consuming more resources than it generates? Because our field so rarely addresses its impact on the world on a large scale, it may be impossible to answer such a question. Is the overall benefit to the world of PP more, less, or much less than the costs to the world of hosting it? We sometimes attempt to show that PP interventions increase grades or student wellbeing in specific schools, profitability and proportion of happy and unhappy workers in specific businesses, or misuse of the health care system among specific samples, but we rarely calculate the resource cost of those programs. Is it really so hard to conceptualize the cost of doing PP?

Consider trying to decide whether the benefits of a PP massive open online course (MOOC) outweighs the carbon footprint and creation of electronics waste required to build, operate, cool, and dispose of the servers streaming the course. One might answer that relative to other content that is streamed, a MOOC is much better, but is it better than no streaming at all? Positive-psychology-as-usual does not ask. ‘Sustainable positive psychology’ might encourage MOOC students to take fewer warm showers, download lessons to watch later rather than stream, get high efficiency lighting, or plant trees as a response. If that depiction of ‘sustainable PP’ sounds absurd, it suggests that whatever our collective impact, we operate in an ‘as-usual’ mindset and leave the hard calculations and balancing of our costs to others. A similar argument could be made for any given PP product relative to the sociopolitical perils furiously whirling across the globe. Despite knowing research showing the importance to wellbeing of stable, democratic, and free societies (e.g. Veenhoven, Citation2009), we neglect to measure whether PP boosts efforts toward stable, democratic, and free societies with anything approaching the dedication allotted to concepts like positive emotions, meaning, or flow. Because we have adopted the expedient path of focusing on individual definitions, individual customers, individual students, and individual foci of interventions, we are poorly positioned to make the case that we are a ‘sustainable PP’. It is almost as if characteristics become included in models of wellbeing primarily because they are characteristics of individuals, not contexts or systems.

It is difficult not to conclude that PP is an as-usual business, extracting what it wants and leaving others to cover the costs. But, even if we optimistically presumed our sustainability, that might not be enough. Other fields have recognized the problems with traditional approaches and the limits of sustainable ones. More vigorous approaches are needed.

Regenerative approaches

Regenerative approaches shift the focus away from increasingly destroying the life-sustaining systems we have, or even sustaining the potential depletion of life-sustaining resources. Instead, regenerative approaches focus on the imperative to increase the health and growth-generating capacity of these systems. The term ‘regenerative’ was initially applied to agricultural practices in the late 1970s and early 1980s in recognition that agricultural systems were too complex to be modeled with rudimentary input and output processes (Francis et al., Citation1986). Simply pushing more industrial inputs into agricultural land neglected the complex, interconnected natural systems that both assisted in and were impacted by the food production. Typically, regenerative approaches consider the urge to hold steady to be insufficient because they sustain inadequate controls on pollution, inadequate access to safe air and water, dangerous levels of climate disruption, disruptive rates of ocean and land surface heating, and threats to direly imperiled biodiversity (e.g. Giller et al., Citation2021). The as-usual state of affairs is viewed as broken and collapsing with accelerating speed. Seeking to merely sustain the current state locks in suffering and perhaps merely slows a spiral into calamity. As a countermeasure, regenerative approaches emphasize additive processes, or those that increase the carrying capacity of a system. ‘A regenerative system provides for continuous replacement, through its own functional processes, of the energy and materials used in its operation’ (Lyle, Citation1996, p. 10). Regenerative processes do not rely on ledger balancing (e.g. paying agencies to hopefully offset carbon emissions from air travel), instead they work to augment growth in the health of those systems as they are used. Systems are carefully designed such that use itself is regenerative. Regenerative approaches are emerging in many fields, such as design, architecture, and agriculture.

Regenerative agriculture provides an instructive analogy for psychology. Traditional, as-usual agriculture seeks to maximize yield from specific crops, often in monocultures that displace and suppress biodiversity (Dudley & Alexander, Citation2017). It is resource-intensive, requiring huge tracts of easily traversable land, seeds that are often patented and carry punitive use restrictions, reliance on chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and other poisons, and access to multiple mechanical implements. A quick internet search reveals the cost of a base combine-tractor with a tiller and harvester to range from US$695,000 to US$895,000. Enormous operating costs necessitate production at profitable scale, which itself creates a drive toward efficiency and mechanizations. The land is akin to a factory floor where materials are combined by machines. In this analogy, wellbeing could be understood to be the yield, or health, of the plants. Picture rows of corn. The farmer seeks for each corn plant to express wellbeing by bearing multiple, disease-free, ripe ears that can be efficiently and profitably brought to market. You can walk into these fields and see the corn towering overhead, shuck an ear, and view the healthy kernels inside. The corn is happy and healthy at an individual unit of analysis.

The problem with agriculture-as-usual is that to increase individual corn wellbeing, resources are extracted and not replenished. For example, tilling fields, sowing crop seeds laden with neurotoxic pesticides, and chronic application of chemicals deplete the soil of microbial and nutrient health, necessitating external resources, such as fertilizers. Planting crops in dead soil or hostile climates necessitates more irrigation, which may deplete surface water or underground aquifers. Traditional irrigation washes excess fertilizer, pesticides, and other chemicals into the water supply, depleting health there too. The corn’s wellbeing masks exhaustion and sickness right under its stalks. But traditional agriculture not only damages the health of sites where crops are grown, it damages surrounding land and waterways where fertilizers blow, flow, or leach, as well as pollinators and wild plants affected by haphazard applications of herbicide, fungicide, pesticide, antibiotics, and hormones (Horrigan et al., Citation2002; Kamalesh et al., Citation2024). The corn’s wellbeing costs neighboring systems their health. Even further afield, traditional agriculture also reduces resources in locations from which fertilizers are extracted (e.g. phosphorus) and where pesticides are manufactured. The wellbeing of corn demands costs from proximal, local and distal systems without reciprocating. To extend this analogy to PP, we might ask if our focus on individual wellbeing likewise depletes the health of proximal, local, and distal systems. And in a prescient parallel, unchecked patterns of land degradation harm both plant health and human health alike (3.2 billion people are adversely affected by land degradation; UNESCO, Citation2023).

Regenerative agriculture seeks the health of crop-hosting ecosystems, rather than specific plants. It aims to cultivate compatible mixes of species with additional goals of eliminating the use of extraneous chemicals and increasing the health of the soil under crops (World Economic Forum, Citation2022). Crop yield is not the only metric or target for intervention. Regenerative agriculture seeks healthy crops, yes, but also support for non-crop plants and microbial ecosystems that add more to soil nutrient levels than they extract. They accept caretaking responsibilities for local water, plant, pollinator, and animal health, and protect distal systems by lessening reliance on extracting important external resources. In an ideal world, regenerative approaches would be used everywhere, improving the health and growth in capacity of proximal and local systems, and relieving stress on distal systems while regenerative approaches at those distal sites increase health there, too.

Regenerative positive psychology

RPP would seek to nurture proximal, local, and distal systems that are healthy for each other as well as the individuals within them. We might invest in any number of healthy overlapping human, social group, business, governmental, charitable, environmental, ecological, or planetary systems. We would learn to be as adept at understanding the strengths and wellbeing of these systems as we are at understanding the flourishing of individuals. Critically, by regenerating the health of life-giving systems we would benefit individual wellbeing.

I am calling for a Regenerative Positive Psychology because I believe we need a reorientation of our bedrock ideas. Among the most fundamental of these is a surge away from conceptual models and practices focused on individual wellbeing. The basic unit of analysis for RPP should not be individual perceptions of wellbeing, but rather perceptions of, or participation in, the growth or decline in life-supporting systems. We are not a climate science, or a political science, we are a psychological and social science, therefore human beings will inevitably be our focus. We can retain our strength of understanding people while still reorienting our field. Rather than repeatedly asking ‘do you feel X about yourself?’” or ‘do you have lots of experiences with Y in your life?’ we can start to ask ‘how have you used X to contribute to the wellbeing of your community?’ or ‘under what circumstances have you seen experiences with Y benefit nature or wildlife?’ At the very least, we would begin talking within the profession and outward to the broader society about what we hope to learn, why we think it is important to connect individual experiences to system-level outcomes, and how we hope to be able to contribute data and practices to the huge undertaking facing all disciplines.

A useful example comes from the study of social wellbeing (Keyes, Citation1998). Here we can understand the factors that support social integration or good relationships by asking individuals about their perceptions of or behaviors in relationships or social groups. It is not the same thing as studying ‘relationships’ or ‘social groups’ but it does generate useful information as a valid first step. It is not so daunting to imagine extending this perspective to other areas. For example, most of my career has been spent trying to understand people’s meaning in life. This body of research is massive now, but even with expansion in many different dimensions, the overwhelming majority of research in this area focuses on three, individually focused research questions: ‘How meaningful does your personal life seem?’ ‘When your personal life feels meaningful, do you also feel other nice, happy things?’ and ‘What kinds of things contribute to you feeling your personal life is meaningful?’ I do not intend to belittle this field. A case could be made that in a short time, meaning in life has become one of the most robustly researched concepts in PP. However, the field clearly is focused on the meaning one person sees in one life. This is despite many theories and accounts of meaning that expect that people with meaningful lives will be generous, self-transcending, and helpful for the world (e.g. Steger, Citation2023). We could be more explicit in seeking to evince such links. We could ask ‘How does the meaning in your life connect to the health and wellbeing of your political climate?’ or ‘When you skip an opportunity to be more helpful to the environment does that undermine how meaningful life seems to you?’

There already is a small literature showing that people whose lives are meaningful are more likely to engage in conservation behavior, but we should do even more. We could include ecological behaviors as outcomes for meaning in life interventions like psychotherapy. We could modify meaning interventions to encourage people to explore and reflect on how meaning in their lives would change if they were more helpful to their life-supporting systems, or, counterfactually, if they watched those systems collapse. We could guide people to consider models of meaning that are more reflective of our shared stakes in overlapping systems. For example, we could instigate meaning interventions to increase engagement in conservation, or in attending to community health, to justice projects, or to many other forms of active assistance and responsibility to the world around us. Certainly, this set of suggestions is naïve and clumsy; progress would require researchers and practitioners to step into issues that might feel overly prescription, moralistic, or even controversial. A counterargument is that we rarely notice the prescriptive and moralistic assumptions undergirding presumably uncontroversial topics. For example, ‘three good things’ style gratitude interventions are clearly prescriptive. They also promote the moral value of being grateful, adopt a moral stance of being grateful for both large and small things, and perhaps they may unintentionally endorse the propriety of reveling in received benefits without pondering any obligation to reciprocate or to ensure that such appreciated elements of life will persist. They value a kind of humility, but also what the system does for the individual, though not necessarily the system itself.

The three pillars of regenerative positive psychology

RPP would aim the field toward understanding wellbeing to include the health and vitality of life-sustaining systems, to recognizing the finitude of those systems’ capacity to provide the raw materials of wellbeing, and to illuminate responsible pathways for nurturing those systems. Just as positive psychology evolved to greater complexity than its initial founding indicated, so, too, RPP will hopefully advance far beyond the ideas in this article. To guide some initial steps in this critical reorientation, it seems prudent to adopt some of the architecture that made positive psychology so successful in the first place. Thus, three pillars for RPP are proposed. Suggesting pillars for a field of inquiry and application is a bit cheeky, but they can be useful for identifying starting parameters of work. In that sense, they can provide goalposts for gauging whether progress has been made toward targets that were thought initially important.

First pillar

Regenerative Positive Psychology seeks to understand and foster wellbeing that includes not only individuals and human contexts, but all living systems and systems that sustain life. These systems are not merely distal influences on individual or human wellbeing, they provide resources that may be fundamentally necessary for wellbeing. As a first step, we both shift away from the individual wellbeing focus and pivot toward viewing wellbeing as the health and growth in capacity of the systems that include the individual. Thus, rather than only reminding people that they exist in systems, or arguing that those systems are inputs to individual wellbeing, we instead double our efforts to view wellbeing as a property of the system that includes the individual.

One criticism I do not see often enough leveled at PP is its contribution to, or at least co-opting into, the market-facing, consumerist self-centeredness that drives global crises on the backs of over-consumption (although see van Zyl et al., Citation2023). Whether we ourselves are pushing consumers toward ‘happiness’ products and service consumption, many companies and hustlers busily market their products and services using the language and concepts of PP. Given the attention PP receives, perhaps we should be more thoughtful in how we tout new concepts and constructs. It may not be our fault, but as each new wave of books and podcasts trumpet new wellbeing constructs, it feeds a lingering message that people need to keep adding more and better happiness dimensions to their lives. Gratitude is not enough, you need grit, too. And next meaning, and mindfulness, and awe, and nature relatedness, and breathwork, and emotional intelligence, and on and on. It hardly leaves any room to articulate the highest purpose for all those wellbeing products, which, one would hope, would be to use them to make life better for as much of the world as possible. It raises the phantasmagorical possibility that our work on individual wellbeing variables has increased self-centeredness as it has increased happiness.

Even though I believe that few teachers, researchers, and practitioners of PP are out there spreading selfish consumerist messages, it is enough to note that others are doing so on our behalf. If we hope that continuing to publish on individually-rooted models of wellbeing will somehow overcome prevailing market forces, the battle already seems lost. How much longer will it be before we can move from teaching ‘positive psychology is about your flourishing’ to ‘positive psychology doesn’t mean you must be self-centered’ – then further to teaching that ‘positive psychology strongly implies you should do good for others, even beyond humans’? And how long from there to achieving a state in which PP has amassed an abundance of research evidence showing that wellbeing is maximized at all levels, whether individual or ecological, when people incorporate practices that seek to heal and regenerate the systems that give them life rather than pulping them up into toilet paper? If we are studying human excellence for the purposes of promoting thriving, we should not invest solely in trickle-down effects of an individual wellbeing-rooted PP. We should be seeking impact at the widest scope already. If people are not truly flourishing now, then our current methods are not sufficient to the goal. I am proposing RPP as one step toward more effectively meeting that goal.

Second pillar

If we succeed with the first pillar, then we become more fluent in our capacity to conceptualize and communicate about understanding wellbeing to prioritize the health and growth in capacity of life-sustaining systems. Undoubtedly, our sophistication working with these systems and their interactions will grow beyond what can be suggested at present. However, it already is apparent that a second pillar of Regenerative Positive Psychology would be to encourage and inspire the production of research, interventions, educational programs, and organizational approaches that explicitly address the social, political, and environmental systems that sustain a good life, both for people and for the planet. Addressing such systems is expansive enough to encompass everything from (a) basic assessment and cataloguing of the systems humans draw on to achieve wellbeing to (b) intentional multidisciplinary partnership with experts in those systems and on to (c) developing and testing interventions to preserve the health of those systems and understand factors that can begin to restore their growth.

We will need focused research as well as collaboration to address this more systemic, collective set of approaches. It is unclear whether PP itself has developed any new collective wellbeing metrics. Even in the most systemic work we do, we borrow external metrics to benchmark returns on investment in wellbeing work. Despite this limitation, work on organizations provides an important template. For example, effective positive leadership could be studied as a tool to move individual work happiness scores, but research also has shown that it impacts well-developed metrics of organizational health and performance, such as profitability, productivity, innovation, and customer satisfaction (Cameron et al., Citation2011). This helps us communicate with other stakeholders, in addition to helping us understand the ability of an organization to persist as a potential source of wellbeing. Faltering companies being drained of resources cannot long provide happy or meaningful work.

At a more ambitious scale, we can be more intentional and consistent in learning from marginalized voices, such as indigenous communities with centuries of knowledge on coexisting within and nurturing vibrant ecosystems, those currently living on the front lines of the climate crisis, and those in under-resourced communities who have been missed by the double-edged sword of Western technological advances. We can use models and templates developed in other fields to integrate metrics of the health and wellbeing of the systems we currently neglect, exploit, or position as inert background factors. We can ask what makes a school healthy, and what students, parents, teachers, and politicians are doing to increase health in the school and its community. We can ask not just whether connecting with nature increases wellbeing but whether that nature is increasing in health, and whether forest-bathers are nurturing that resource. I know there are many people out there already doing this. We can formally elevate such work and learn how to make it more effective and scalable.

Others (e.g. Kern et al., Citation2020; Waters, Cameron, et al., Citation2022) raise similar aspirations for PP, thinking through ideas about socially embedding PP. These and other scholars have argued that the individual is by necessity best understood as part of social and political systems (e.g. Lomas, Citation2015). Their efforts to reorient the field have helped explain systems approaches, and have argued persuasively to expand beyond the initial surge of interest to third-wave PP (Lomas etal., Citation2020; Wissing etal., Citation2021), and even beyond (Wissing, Citation2022). Third-wave PP arguments clearly stated the need to broaden the scope beyond the individual, to embrace the multidirectional influence of individuals and systems, embrace of positive and negative aspects of psychological experience, a richer embrace of global cultures, and the need for interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research. These previous arguments are similar to the call I am making here. Further, some of these systems and third-wave propositions have sought to orient the field to beyond-human wellbeing, with Wissing (Citation2022) noting the need for attention to wellbeing for ecological systems and the human impact on those systems. Thus, there is considerable consilience and agreement among these earlier calls and the present one, and reading these sources is strongly recommended. The extension I am pushing is that we also must explicitly attend to the wellbeing of these systems, and further a framework to build a science of the regeneration of the systems as an embedded feature of Regenerative Positive Psychology. For example, in discussing the benefits of integrating PP into schools, a lurking caveat is usually addressed regarding how stretched-thin school time, resources, and people are. And this was before the explosion in local and regional governmental interjection in education, such as that seen in several states in the USA. Certainly, schools are great sites for PP principles, but what does it matter if schools are so strained they cannot implement them and if PP itself has scant answers to bolster and support school health and healing?

Third pillar

Thus, the third pillar of Regenerative Positive Psychology is to explicitly prioritize the development of research, education, and interventions to encourage and cultivate traits, attitudes, and behaviors that make each of us positive caretakers and benefactors of mutual and collective wellbeing, as well as the systems that support that wellbeing. The historic emphasis within PP on scientific study and responsible practice must be maintained. Such emphasis sometimes fosters a sense of moral-free or value-free conduct, a sense of the objective scientist or practitioner. In this approach scholars and practitioners follow the data to constructs of highest scientific validity, and help clients and end-users with goals that we strive not to influence. Setting aside the idea that we might simply run out of time for such hands-off approaches to preserve our environment, society, or communities, it could be argued that each of us is highly selective in what we dedicate our work to. We build expertise in an area, not because there is the most evidence for it, but because it is most interesting to us. In science and practice, forging new ground, innovation, and expertise are jointly valued. We pick a focus, often ahead of convincing data, because we believe it is important, helpful, or just personally captivating. So, I would suggest that choosing to prioritize ‘research, education, and interventions to encourage and cultivate traits, attitudes, and behaviors that make each of us positive caretakers and benefactors of the mutual and collective wellbeing, as well as the systems that support that wellbeing’ is not vastly different than choosing to devote our professional lives to meaning, gratitude, character strengths, or any other topic.

We still must base our work on evidence, but in order to have sufficient evidence to understand what is viable in the first place, we need to start gathering data now. For example, all research studies and practice programs might incorporate measurement of such characteristics, whether that is ecological behaviors, engagement in justice and fairness activism, volunteering and helping behaviors, civic and political engagement to reduce the most parasitic corporatism, etc. Fueled by the data and case studies coming from such work, RPP would expand to quickly innovate around methods of demonstrating contagious benefits and actual regeneration of psychological, social, political, and ecological resources. An additional advantage of moving on this third pillar is that our field has a proven track record of incorporating the best of other disciplines, to mutual benefit. Just as PP increased engagement with wellbeing concepts across fields, so RPP could lead to an expanded set of methods and perspectives that reflect pressing global concerns and demonstrate our greater courage as stewards of a shared habitat.

Pursuit of a Regenerative Positive Psychology could also help us break free of paralyzing dogmatisms. On the one hand, we have basic scientists who want to hold the line on academic freedom and a perceived right to study whatever they want without being restricted by whether outsiders think their research ‘helps’ or ‘is relevant’. On the other hand, we have entrenched interests in society that admonish applied scientists to ‘stay in their lane’ and avoid treading on pet industries or ideologies. Both dogmatisms make it harder to engage at the scope required to solve the systemic problems depressing wellbeing. If positive psychologists modeled a RPP, then their research would demonstrate a connection to crises that are gripping populations worldwide, and this research will begin to inform policies and models that try to be truly solution-seeking. We would be buttressed by data and theoretical mandate alike.

Table 1. Three Pillars of Regenerative Positive Psychology

Expand definitions of wellbeing. Wellbeing is understood not only as the thriving of the individual, but also as the health and growth in capacity of the systems that include the individual.

Build a science of wellbeing systems. It is vital to encourage and inspire the production of research, interventions, educational programs, and organizational approaches that explicitly address, at minimum, the environmental, social, and political systems that sustain a good life.

Generate knowledge of positive human caretaking. Priority is placed on research, education, and interventions that encourage and cultivate traits, attitudes, and behaviors that position individuals as positive caretakers and benefactors of mutual and collective wellbeing, as well as the systems that support that wellbeing.

Some next steps for expanding the scope of regenerative positive psychology

PP already spans a far-reaching scope of human experience (from gene expression to global happiness), with similarly broad scopes of attempted impact (from none to societal) and settings (from within one neuron to multinational corporations). Regenerative Positive Psychology should welcome similarly broad scopes.

Perhaps the narrowest scope would resemble existing research or practice focusing on individuals, but with an added element that is responsive or solution-seeking with regard to global issues or crises. For example, a neuroimaging study might investigate new categories of evocative tasks, such as images of climate disasters or the scars of wealth inequality among its noxious stimuli, or videos of people restoring streambeds or first-person accounts of successful initiatives to redress the plight of the unsheltered among its positive stimuli. Similarly, a coaching session or workshop on might include the counterfactual gratitude prompt focusing on the clean air, fair governance, or preserved cultural heritage and traditions we still can take for granted, or a guided mindfulness activity might extend lovingkindness meditations through intention-setting around living more simply and using our spare resources to assist life systems and people in need rather than getting another iced coffee in a disposable carry cup.

A slightly more ambitious scope would be to initiate collaborations outside of typical PP partners to include indigenous knowledge and practice experts, ecologists, health charities, virologists, conservation biologists, governmental ministry heads, civil rights organizations, venture capitalists, political scientists, or chemical engineers to pioneer new research areas and community projects. For example, recent advances in understanding echoes of colonialism in psychology (e.g. Utsey et al., Citation2015) and in learning from indigenous knowledge (Dudgeon et al., Citation2023; Kim & Park, Citation2006; Kim et al., Citation2006) indicate that the broader field has the potential to transform and grow radically to better embrace the vast wealth of perspectives and knowledge that have been neglected in favor of our current, narrow, cultural orientation (see van Zyl et al., Citation2023) Our field has quickly blossomed into public awareness, and we can both elevate the visibility of other fields working toward more positive global futures as well as learn new methods, gain the ears of new stakeholders, and intervene on different playing fields.

Another expansion of scope would be to dedicate our energies toward explicating and disseminating knowledge on new or neglected concepts and interventions that aim at collective or contextual regeneration. For example, in my field of meaning in life, many like me continue to work hard to understand the dimensions of personal meaning, but it might be time to heed calls to better understand how positive and regenerative collective meaning can be made, or to better understand which collective sources of meaning are most at risk and most in need of preservation and healing. Alternatively, it may be time for meaning researchers to devote their talents to understanding how toxic and malicious collective meanings are formed and spread, as in conspiracy theories or cruel ideologies.

Perhaps at the most ambitious scope, researchers and practitioners would insist that systems-levels interventions with schools, companies, governments, or nations include explicit resources for collective or contextual-level changes, along with pressing clients for follow-up commitments. Rather than conducting workshops focused on individual wellbeing or better human management approaches, regenerative positive psychologists could guide organizations to develop, commit to, and follow through on plans to reduce compensation inequality, restore wildlands, or bolster the rule of law and democratic elections. Admittedly, there is little cost to an organization for making and breaking empty promises, but if we were willing to walk away from organizations that broke their commitments, and if each subsequent consultant proposed a similar arrangement, the message might eventually penetrate the haze of quarterly performance nad profit reports.

Positive psychology should acknowledge that while seeking wellbeing is better for people than ill-being, that it is not enough. Great strides have been made in balancing the scales of what social science fields pay attention to. One might even say that we know enough about what happiness is from a Western perspective, or that at least we have a long enough menu of wellbeing concepts that charting more may fall prey to diminishing returns. What we actually need more of are the perspectives on wellbeing held by the majority of humanity who live outside the academically dominant Western cultures. We also need effective intervention approaches that have larger effects for more people. However, without appreciating how the foundations of a good life are deteriorating, we are missing the critical focus of interventions in the first place. How many strengths surveys does it take to intervene for someone whose home has burned, whose crops have failed, whose water is filled with plastics and forever chemicals, whose cemeteries and memorials have flooded away, and whose children are plagued with diseases? Perhaps we can indeed adapt to be happy in increasingly erosive contexts, but would we not be better trying to save and restore the best of what remains to us? Eventually, what does it matter which is the happiest of the burning nations?

A Regenerative Positive Psychology not only acknowledges the plight facing so many living creatures, landscapes, waterways, and people, but it also opens us to acknowledging the ways in which our actions may worsen that plight. At a rudimentary level, how are we to encourage authentic happiness if part of that happiness is ignoring the harm we participate in? What is authentic about that?

There is fiery debate about whether members of well-off societies should even acknowledge that morally reprehensible acts occurred in their countries, much less that systemic injustices and entrenched advantages might persistently benefit some over others. So, I would expect that asking PP to acknowledge that many of our members live in places and in a manner that causes ecological, economic, or social harm would be controversial, but I think it would be good if some of us did so regardless. If not, at minimum, a Regenerative Positive Psychology also encourages us to look bravely at the humanity-wide problems we are all facing. I believe this would further incentivize us to listen to stories, experiences, and proposed solutions from people who we have struggled to give voice to. The rootedness of PP in a wealthy, democratic, Western cultural milieu has frequently prompted sincere efforts for more commitment to learning of indigenous models of wellbeing, as one example. Anything that gets us to elevate models that have seen relatively less attention can only help us understand what it means to thrive. If PP reorients to regenerating the health of our beleaguered life-giving systems, we might turn our attention further afield from the metropolises of Europe, North America, and Oceana, and more deeply toward the human-nature interfaces at the farther edges of urban life, or in the hearts of rural life, or even in the remaining open spaces where humans are visitors, such as oceans, seas, ice continents, and wildernesses. We might ensure we consult with those displaced, incarcerated, exploited, persecuted, unhoused, and impoverished in their encounters with our social and political behemoths. We would not merely be testing the limits or generalizability of wellbeing variables, we would be seeking and testing solutions to the wellbeing challenges engulfing us all.

Conclusion

We positive psychologists are dreamers of a kind, who are nonetheless practiced in balancing wishful thinking with the reality of probabilistic statistics, cultural diversity, market realities,workshop outcomes, and many other factors. Far from trampling our idealistic bent, this call for a Regenerative Positive Psychology seeks to inspire it even further. If we let our imaginations run rampant, we might run idealistic scenarios through our minds in which the rampaging disasters of climate crisis, wealth inequalities, authoritarianism, and pollution were neutralized. We could then ask ourselves which interventions would have the greatest impact on the wellbeing and excellence of human beings. Which of the two following scenarios would elevate the greatest number of people and lift them the highest – (a) providing food and shelter security, confidence that one can remain in one’s homeland and not be forced to flee war or drought or famine, removing toxins from our air and water, securing sufficient income and wealth for all to feed and educate their children, sustaining biodiversity and thriving forests and oceans as a source of food and medicine and restoration, preserving cultural heritage and language and ways of knowing, and dissociating the need for a working wage from the hunger to engage in valued work, or (b) teaching every child and adult about character strengths, positive emotions, mindfulness, meaning in life, goal-setting, values, individual performance, curiosity, gratitude, grit, cognitive flexibility, awe, compassion, and appreciative inquiry? The point of this call is that we ought not choose! We can work toward both individual and systemwide levers of global uplift simultaneously. We can, and we should.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/) operates under a Creative Commons license allowing the use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium of visualizations and data.

2. Also were examined the invited program of the 2019 World Congress on Positive Psychology and Amazon’s top 100 book on happiness, both of which were similarly monocular. Analyses available upon request.

References

- The APA 1998 annual report (1999). American Psychologist, 54(8), 537–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.537

- Boenigk, S., & Mayr, M. L. (2016). The happiness of giving: Evidence from the German socioeconomic panel that happier people are more generous. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 1825–1846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9672-2

- Cameron, K. S., Mora, C., Leutscher, T., & Calarco, M. (2011). Effects of positive practices on organizational effectiveness. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(3), 266–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310395514

- Christopher, J. C., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396

- DeNeve, J., & Oswald, A. J. (2012). Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 19953–19958. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211437109

- Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well‐being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 3(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x

- DiMaria, C. H., Peroni, C., & Sarracino, F. (2020). Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00074-1

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409

- Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., & Rao, M. A. (2015). Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: Examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

- Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Seligman, M. E. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903157232

- Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., & Walker, R. (2023). Embracing the emerging indigenous psychology of flourishing. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(5), 259–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00176-x

- Dudley, N., & Alexander, S. (2017). Agriculture and biodiversity: a review. Biodiversity, 18(2–3), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2017.1351892

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

- Fleury-Bahi, G., Pol, E., & Navarro, O. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of environmental psychology and quality of life research. Springer International Publishing.

- Footprint Data Foundation. (2022). York University ecological footprint initiative, and global footprint network: National footprint and biocapacity accounts. https://data.footprintnetwork.org

- Francis, C. A., Harwood, R. R., & Parr, J. F. (1986). The potential for regenerative agriculture in the developing world. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 1(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300000904

- Giller, K. E., Hijbeek, R., Andersson, J. A., & Sumberg, J. (2021). Regenerative agriculture: An agronomic perspective. Outlook on Agriculture, 50(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727021998063

- Grant, A. M., Curtayne, L., & Burton, G. (2009). Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: A randomised controlled study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(5), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902992456

- Graziosi, M., & Yaden, D. (2019). Interpersonal awe: Exploring the social domain of awe elicitors. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(2), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1689422

- Horrigan, L., Lawrence, R. S., & Walker, P. (2002). How sustainable agriculture can address the environmental and human health harms of industrial agriculture. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(5), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110445

- Kamalesh, R., Karishma, S., & Saravanan, A. (2024). Progress in environmental monitoring and mitigation strategies for herbicides and insecticides: A comprehensive review. Chemosphere, 352, 141421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141421

- Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297