ABSTRACT

This paper considers the social value of anonymity in online university student communities, through the presentation of research which tracked the final year of life of the social media application Yik Yak. Yik Yak was an anonymous, geosocial mobile application launched in 2013 which, at its peak in 2014, was used by around two million students in the US and UK. The research we report here is significant as a mixed method study tracing the final year of the life of this app in a large UK university between 2016 and 2017. The paper uses computational and ethnographic methods to understand what might be at stake in the loss of anonymity within university student communities in a datafied society. Countering the most common argument made against online anonymity – its association with hate speech and victimisation – the paper draws on recent conceptual work on the social value of anonymity to argue that anonymity online in this context had significant value for the communities that use it. This study of a now-lost social network constitutes a valuable portrait by which we might better understand our current predicament in relation to anonymity, its perceived value and its growing impossibility.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Introduction: the death of a network

Anonymity has been under attack as the internet age has unfolded. Losing sight of the value of anonymity – a value based in ‘the possibility of acting or participating while remaining out of reach’ (Nissenbaum Citation1999) – online activity has become organised around the interests of a data capitalism in which the extraction, profiling, personalisation and accumulation of data on individuals is privileged, while the value of anonymity, privacy, secrecy and ephemerality is reduced. This is so much the case that calls for the ‘banning’ of anonymity online have recently been made at government level in the UK (Ball Citation2018). This paper counters such calls by asking a key question within the context of educational social media: what might be at stake in the loss of anonymity within student communities in a datafied society? In answering this question it draws on theory emphasising the social value of anonymity in order to better understand and argue for its place on campus, and for a broader conversation within universities and the wider society around the value of anonymity.

The paper approaches this question of value by presenting research tracking the death of an anonymous social network (Yik Yak) which, for a short period, was an important element of the social media ecologies of many higher education students. It uses the empirical study of this decline to theorise the ways in which anonymity can be productively engaged within university networks, and argues for an opening-up of discussion within higher education of the potential social value of anonymity in university online communities. This social value is well summarised by Bachmann, Knecht, and Wittel (Citation2017) as residing in: anonymity as freedom from surveillance, accountability and social constraints; anonymity as a space apart from the ‘commodification of the social’; and anonymity as an egalitarian mode within which it is possible to experience ‘an unmaking of status inequality’ (244–245). It is the first two of these that are drawn on here as helping shape and theorise our analysis.

There is – despite what Bachmann et al. describe as a ‘small boom’ in anonymity studies across the disciplines (Bachmann, Knecht, and Wittel Citation2017, 242) relatively little research on anonymity and social networks in higher education. Research and commentary to date has tended to focus on the place and value of anonymity within assessment and evaluation practice (Li Citation2017; Raes, Vanderhoven, and Schellens Citation2015), peer review (Fresco-Santalla and Hernández-Pérez Citation2014; Bali Citation2015), research ethics (Moosa Citation2013; Kelly Citation2009), and sometimes on teaching methods (Bell Citation2001; Chester and Gwynne Citation1998), but rarely on online communities of students or its potential value for peer networks. While there is quite a significant body of literature looking at anonymity within computer-mediated communication and on social media (Scott and Orlikowski Citation2014; Ellison et al. Citation2016; Christopherson Citation2007), it is relatively rare to find such research specifically focusing on universities and student social networks. The general direction of anonymity studies in higher education has been to assume its value for some areas of activity (peer review, assessment and evaluation, research ethics, whistleblowing) while vilifying it for others (teaching, peer communication, social media). Such vilification is often on the basis of a commonly reported association with reduced social cues and ‘toxic’ disinhibition (Suler Citation2004) in anonymous online networks. However recent studies have emphasised the need to take a carefully nuanced approach to anonymity online in order to understand both its negative and positive effects (for example Kang, Brown, and Kiesler Citation2013; Correa et al. Citation2015; Christie and Dill Citation2016; Schlesinger et al. Citation2017; Wu and Atkin Citation2018), with some studies finding higher levels of toxicity and aggression from non-anonymous users when compared with those posting anonymously (Rost, Stahel, and Frey Citation2016).

Yik Yak was a social media application which was designed according to the three principles of anonymity, hyper-locality and community moderation, and focused specifically on user appeal on university campuses. Developed by two students (Brooks Buffington and Tyler Droll) at Furman University in the US, it launched toward the end of 2013 and quickly gained popularity across universities in the US and the UK. While firm usage figures are not available, by October 2014 it appears to have had around 2 million monthly active users (Constine Citation2016) almost entirely on-campus higher education students, and was the third most-downloaded iOS app in the US (McAlone Citation2016).

The app allowed students to use their smartphones to post short, anonymous messages to other users in close proximity (for example, our research showed it was used quite regularly as a back-channel in lecture theatres, and as a procrastination device in library study spaces). When the app was at its peak of popularity, its hyper-locality was more pronounced: users would see posts only within a 1.5 mile radius of their location. This would expand to a 10 mile radius if numbers of posts dropped (Stoler Citation2015). Importantly, the posts were community moderated: users could upvote or downvote other posts and if a post received four or more downvotes it was automatically deleted. Users could accumulate local social capital (‘Yakarma’) by receiving upvotes and by posting frequently. While user anonymity of a networked device is never total, anonymity as a principle was central to the design of the app when it was first launched: each message, or ‘yak’, would be accompanied by a temporary ‘handle’ which would persist only through a single thread of discussion and, for most of the life of the app, profiles, profile images and stable handles were neither enabled or required.

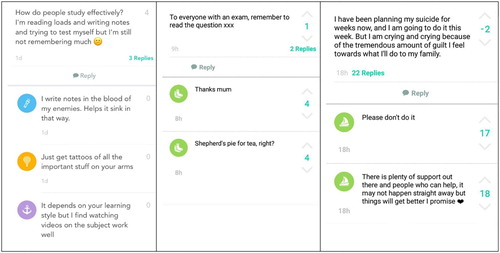

The figure below illustrates how yaks looked on user devices, with the orginal post at the top and the anonymous responses unfolding below, showing how each user is assigned a random, temporary avatar image by the app. Numbers of upvotes and downvotes are shown on the right of each yak. The content of the yaks in are generally illustrative of the kinds of yaks collected during this research, which tended to focus on issues surrounding campus life, peer support, mental health and the humour that was distinctive to this application in its heyday. These themes, their implications and the methodology used in the study are discussed in greater detail later in the paper.

The growth of the Yik Yak user base between early 2014 and 2015 was dramatic: figures reported by the company show an increase in numbers of upvotes and downvotes in the Los Angeles area, for example, as increasing by 822% between February 2014 and February 2015 (Shontell Citation2015). By that time 2.5% of all iPhone owners in the US were using Yik Yak on a regular basis, according to data published by Forbes (Olson Citation2015), outstripping other anonymous messaging apps popular at the time by a very considerable margin. Active marketing on university campuses brought the app to around 1600 US campuses by autumn 2014, with 50–80% of each student body using it (Shontell Citation2015). By early 2015 it was also being heavily used at UK universities: survey data from our own study suggests that at least 30% of undergraduates at our research site were active users of the app at that time. At the end of 2014, and after a $61 million injection of venture capital funding the app was valued as being worth between $300 and $400 million (Russell Citation2014).

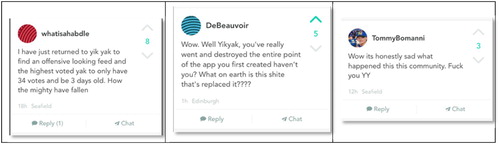

However, following adjustments made to the app which reduced its anonymity (discussed in full later in this paper), its decline was as dramatic as its rise. From 3rd most popular US iOS download in September 2014, it had dropped to 1067th by April 2016 (Constine Citation2016), and was widely reported as having lost its popularity and ‘cool’ on campus (McAlone Citation2016). Estimated numbers of active monthly users had dropped from a high of close to 2 million, to only 264,000 (Safronova Citation2017). In December 2016 Yik Yak laid off 60% of its staff (Soulas Citation2016) and the app finally closed in early May 2017. The research reported in this paper, which ran from July 2016 to May 2017, gathered data on student use at one large university over this period of decline and closure.

Methodology

Prior studies of Yik Yak focused on either qualitative or quantitative methods for analysing data sets captured solely from the app. For example West (Citation2017) and Byrne (Citation2017) developed analytic methods for understanding a Yik Yak dataset qualitatively, while Saveski, Chou, and Roy (Citation2016) and Black, Mezzina, and Thompson (Citation2016) described quantitative methods using topic modelling, sentiment analysis and content analysis. Our approach was one which interrogated the broader technosocial aspects of Yik Yak use within the context of a specific campus setting. For this reason, we wished to accompany analysis of data gathered from within the app with insights generated through ethnographic methods designed to understand its culture of use. The methodological mix we devised therefore incorporated ethnographic elements including participant observation, interview and survey, with computational methods including content analysis and topic modelling. We briefly describe these below.

The research site

Our research was conducted within a large, research-intensive university in the UK with close to 40,000 students. This is a university with campuses spread across the city, with wide variation in teaching methods and contact hours and large numbers of international students. It is also a university with competitive entry for most programmes, resulting in highly motivated students often uncomfortable with expressing concerns around academic or mental health issues that might have negative effects on ‘success’. Many students hold part-time jobs while studying. Our findings are therefore particular to this diverse, widely-spread, large community. It is likely that Yik Yak usage and experience would have been quite different in a smaller, more intimate institution with a single campus. We argue against the idea that app design determines behaviour, instead emphasising the importance of a critical, sociomaterial approach which accounts for such contextual factors.

Ethnographic methods

As Yik Yak was a social media application used primarily by undergraduates, we employed three undergraduate students to work with us as research assistants. These students conducted participant observation within the Yik Yak community, recording and coding posts to the app (‘yaks’) over four periods of seven days, between October 2016 and May 2017. Yaks were captured using smartphone screenshots, archived, transcribed and thematically coded according to a schema provided by the project team. The schema was refined between each round of data collection in discussion with the student research assistants who were mentored through the stages of analysis to ensure trustworthiness and robust documentation of data, including group sessions to refine the coding framework, and clear documentation of emergent and final themes and peer debriefing.

The research assistants wrote summary reflexive reports after each round of data collection, providing thick descriptive commentary and an overview of the data collected. We used findings from an annual social media survey conducted at the field site to gather baseline data on levels and type of social media usage among students. In 2016 this survey was sent to approximately 10,000 students, and had 578 responses. Toward the end of the data collection period, we tested our emergent findings via interviews with ten undergraduate students who had identified as Yik Yak users in this survey. These interviews were conducted by the project team and the undergraduate research assistants.

Computational methods

Yik Yak presented some challenges in terms of data collection from the app itself: no official API or other machine to machine interface existed, and direct mining of Yik Yak data in bulk proved impossible. The daily volume of yaks varied substantially over the period of the study, and the rapidity with which offensive yaks tended to be downvoted and therefore automatically deleted means that it is possible some of these were not counted.

The value of Yik Yak lay both in its anonymity and in its geosociality: the community using the app was generally focused within a 1.5 mile radius, which mapped fairly well onto the central campus of our field site. However, when the volume of yaks being posted decreased, the radius expanded by several miles, making it difficult at times to be sure data was being generated within a single site. While several studies (West Citation2017; Saveski, Chou, and Roy Citation2016; Black, Mezzina, and Thompson Citation2016) have flagged these and similar issues, we are not aware of any other studies which have systematically addressed them by combining computational with ethnographic methods. Our approach enabled us to engage with rich data from the participant observation to contextualise and address some of the limitations of our computational data.

We adopted a convenience approach to this latter by manually gathering yaks from the central campus of our field site. The yaks were gathered from Mondays to Fridays between September 2016 to March 2017. In total we gathered 7497 original yaks and 39,140 replies over this period. These data were processed to extract the text of yaks along with their dates. Samples were merged and duplicates removed to produce the set used for topic modelling.

Topic modelling is a means to acquire a broad-brush overview of the content of large data collections and has been used to analyse Yik Yak data by Saveski, Chou, and Roy (Citation2016) and Koratana et al. (Citation2016) among others. We applied Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modelling to the yaks that we collected using the Mallet toolkit. LDA is a probabilistic method that models words and the documents in which they occur in order to cluster them into topics. Because topic modelling works better with longer documents we defined a document as an original yak concatenated with all of its replies.

In addition to topic modelling we explored our yak collection with other linguistic analysis tools. In order to assess the amount of offensive language in our data we followed Saveski, Chou, and Roy (Citation2016) in matching the yaks to a list of offensive words, using a combination of pre-existing datasets.Footnote1 Further, we developed a method aimed at uncovering name-calling by applying linguistic analysis and using regular expressions to pull out instances conforming to particular patterns. These methods revealed that usage of offensive language and name-calling were generally low across our field site, a finding discussed more fully below.

Ethical issues

Our approach to research ethics was one informed by the notion of ‘contextual integrity’ (Nissenbaum Citation2004) which emphasises that privacy violation occurs when ‘either contextual norms of appropriateness or norms of [information] flow have been breached’ and that ‘information revealed in a particular context is always tagged with that context and never “up for grabs”’ (125). Contextual factors in Yik Yak led us to conclude that the data collected through the app was largely percieved as public, and therefore ethically less sensitive than in some other social media contexts. User identity in Yik Yak was already anonymised at the level of the user interface. In addition, it was the norm for yaks to be gathered, aggregated and re-posted on other social media sites, by both the app developers and its users. Therefore while user expectations of privacy regarding their anonymity would have been very high, their expectations of privacy regarding the content of their posts would have been low (a conclusion also reached by Byrne (Citation2017)).

Further, Yik Yak was a volatile, ephemeral space in which constant disclosure of researcher presence would have been functionally extremely difficult, and also largely futile, making disclosure and consent from the user base impracticable. We addressed this problem by appointing active members of the Yik Yak community – undergraduate students – as our research associates, relying on these individuals as an ethical ‘check’ to help keep the project in line with what would be acceptable to the community more widely.

The wellbeing of the student researchers was an additional ethical issue for the project, in that there was a risk of them being exposed to negative or emotionally problematic content (for example there was one particularly difficult suicide-related thread during the period of the study). To address this, the undergraduate researchers were closely and responsively mentored by the project team, with regular de-briefs and clear responsibilities and guidelines set.

Ethical approval for the research was sought and confirmed by the relevant committee at the research site.

A history of the death of Yik Yak: hate and the social value of anonymity

We turn now to a discusion of our findings, presenting these within a wider analysis of the place of anonymity in the contemporary university. Why did Yik Yak fail? Perhaps the most commonly-cited cause in the popular media is that the app became a hotbed of hate speech, cyber-bullying and victimisation, making its demise not only inevitable but welcome. We suggest here that – while the controversy over hate and victimisation was one highly-publicised factor in its decline – there are others which are equally significant: the developers’ inability to recognise the value of anonymity to their users as evidenced by the design and development choices that were made toward the end of the life of the app, and their inability or unwillingness to ‘monetise’ the data the app collected and generated.

By analysis of these factors in relation to our field site, we attempt to answer our guiding question regarding what might be at stake in the loss of anonymity within student communities in a datafied society. In doing so we offer insight into the contemporary social and critical contexts of online anonymity within university communities, and lead into our concluding critical argument that the moral panic around anonymity evident in media responses to Yik Yak, and other similar apps, works not only as a failure to engage with these more intractable issues, but as a hegemonic moral blind for the normalisation of data extraction, profiling and the surveillance capitalism which depends on these.

Yik Yak and hate

There were several well-publicised incidents of hate and victimisation over the period of the life of Yik Yak. For example, in October 2014 a female student at Middlebury College in the United States published an open letter describing her distress following personal victimisation on the app (Seman Citation2014); in late 2015 there were reports that several arrests were made following threats posted at other US campuses including racist threats at The University of Missouri, mass shooting threats at Charlston Southern University, and terrorism threats at Emory University. On 5 May 2017 the New York Times reported that former students of the University of Mary Washington were bringing a federal complaint to court accusing the university of failing to protect its students from anti-feminist hate speech and threats of violence on Yik Yak. Commentators on these incidents were often quick to assume a strong causal link between these hateful incidents and the disinhibiting effects of online anonymity on Yik Yak (for example Li and Literat Citation2017). The campus arrests also prompted criticism around the limits to user anonymity that could be assured by the app (Xue et al. Citation2016).

In fact Yik Yak’s privacy and legal policies were quite clear that anonymity for users was not total: it could be breached in response to emergency or in order to ‘comply with the law, a judicial proceeding, court order, subpoena or other legal process’ (Cox Citation2015), with date and time stamps, IP addresses, GPS coordinates and handles retained to this end. As Bachmann, Knecht, and Wittel (Citation2017) remind us, ‘there is hardly ever total anonymity, neither temporally, nor socially, nor technically’ (249). Even without legal process, a certain level of hacker de-anonymisation of yaks was demonstrated as possible (for example Xue et al. (Citation2016) and Moskowitz (Citation2014)) ().

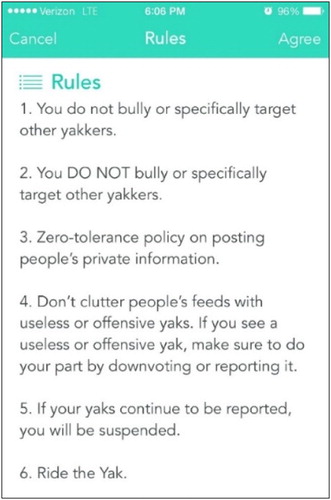

Yik Yak was arguably more responsive than other social media platforms when it came to limiting its capacity for toxicity and bullying: over the period of its existence the developers implemented word filtering and warnings for violent and discriminatory language, succinct rules for engagement () and geo-fencing protocols for high schools (a way of ‘locking out’ particular locations) to prevent routine uses of the app by teenagers at school. With this last, they shut out a large proportion of their user-base at the time (as one commentator asked, ‘What other social media company has attempted to physically block teenagers from using its product?’ (Hess Citation2015)).

Criticism in the literature that Yik Yak was at the same time too anonymous (enabling disinhibition and victimisation) and not anonymous enough (in technical and legal terms) perhaps illustrates some of the complexity around the question of anonymity that this research attempts to unpick. Certainly victimisation and cyberbulling on university campuses is real and devastating, carrying serious consequences for the mental health of both victims and perpetrators (Selkie et al. Citation2015). Gahagan, Mitchell Vaterlaus, and Frost (Citation2016) found that as many as 46% of higher education students have witnessed cyberbullying on social media, and Dishon and Ben-Porath (Citation2018) have made a strong argument for the need to re-think the concept of ‘civility’ in online educational contexts. The argument we put forward in this paper does not attempt to minimise the negative effects of cyberbullying and online disinhibition on the mental health and wellbeing of students, and it does not uncritically seek to decontextualise or champion anonymous social media per se. It does, however, suggest that our discussion of anonymous social media within universities and beyond needs to be wider and more open than it has been to date.

While there clearly were instances of hate and victimisation enabled and amplified by Yik Yak, we suggest a need to move away from assuming that this was somehow determined by the app design to take on board a sociomaterial analysis which brings the institutional culture and context within which the app was used into the analysis. If hate speech was prevalent in a university’s Yik Yak feed, this would likely indicate its parallel presence in clubs, bars, coffee shops and playing fields. It is important, as Bancroft and Scott Reid (Citation2017) have argued, not to reduce political questions to technical ones in understanding how anonymity works online. For example, the dominant mode on the campus we researched was one in which Yik Yak was most often used for peer support, empathy and community building, with very limited evidence of toxicity. As one of the project undergraduate researchers reported:

YikYak was a platform where students shared all aspects of their university life. Since it was a truly anonymous platform, I had a feeling that people were sharing all their genuine thoughts and feelings as there was a shared general feeling that most people read and respond to posts not with judgment but with empathy and understanding. I had seen posts from people being excited over achieving 1sts in their degrees to people feeling depressed or overwhelmed by university to people just merely sharing their dailyness.

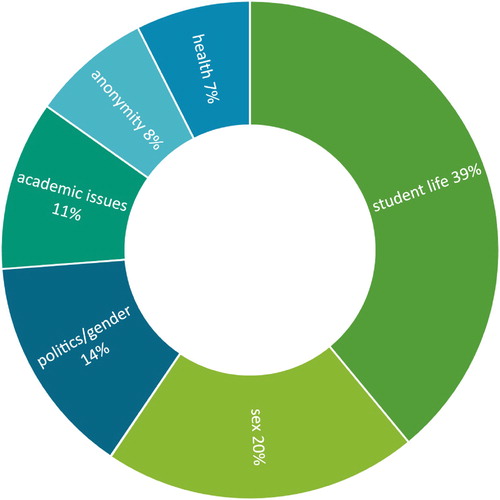

Findings from our research align well with those of previous studies: only 2% of our corpus of yaks contained offensive language – this using a wide definition of ‘offensive’ which included common everyday profanities often not considered taboo. Yaks which were directly abusive of other users were even less common. Of the 7497 conversations (yaks and replies) that we were able to categorise, the majority were general discussions and commentary on undergraduate student life (food, flatmates, clubs, TV, jobs, parents), with generally positive and supportive conversations about politics, sex and health making up the rest (). Politics-related talk was for the most part focused on current or recent events: Brexit, the election of Trump, racism and terror attacks. Conversations on the theme of anonymity itself were also notable, primarily because over the last year of its life Yik Yak made several experiments with this aspect of its functionality, discussed in more detail below ().

Table 1. Indicative conversations from the main topic groupings identified.

The social value of anonymity

While the negative media frenzy around Yik Yak as a poisonous platform of hate was certainly part of the story of its failure, we move on now to suggest two other reasons why – despite its rapid early growth – it declined and died. The first, strongly indicated in our data, was the failure of the app developers to understand the social value of online anonymity to students; the second, more speculative issue, was their failure to find a way of monetising the data generated by the platform. Our argument here is that rather than responding to anonymous social media solely in terms of its ‘morality’ and the debate around disinhibition and victimisation, we need to include discussion around the value of anonymity as a sensibility, and to see its marginalisation as implicated within a broader social and techno-political context which normalises surveillance capitalism and ‘personalisation’ through data extraction.

To return to the story of the decline of Yik Yak, after its popularity high point around the end of 2014 and a venture capital investment of $61 millionFootnote2 its growth halted and usage entered a decline (McAlone Citation2016). To try to address this, the developers introduced a series of app re-designs, focusing on incremental reductions in the feature which was in fact of most value to its users: anonymity. First they introduced optional ‘handles’ (stable user names) and then optional profiles. Finally, in a disastrous move in August 2016 they made handles and profiles compulsory for all users, justifying the move as working to enable better local community-building on campus, but likely driven by a need to build a more sustainable business model based on data extraction and personalisation. While users could still adopt pseudonyms if they wished, the sensibility of the app had radically shifted away from anonymous, hyper-local chat towards campus link-ups and persistent user identity. Verification via users’ mobile phone numbers was now required, and a ‘local yakkers’ function introduced to enable co-located students – for example in a library study area – to see who else was yakking nearby, making it far easier to identify who was posting at any given moment. The developers justified the change in the following terms:

Since day one, we were very focused on hyperlocal, and anonymity was just a mechanism we used to make the onboard easy. Right now we are focused on college campuses and really nailing what are these local interactions so we can power the best user experience. (Carson Citation2016)

A few weeks later our undergraduate research associates reported a dramatic drop in usage of the app within the local community:

The decline of Yik Yak was clearly evident in the lack of use compared to a year or two ago. The number of posts could be as low as 5 a day, therefore it was difficult to collect data from this social media platform as it wasn’t used. Posts were generally looking for interaction, asking questions or seeking relationships. The lack of response was notable, again with the same people tending to respond to all posts.

The introduction of a username and profile was a terrible decision by the app creators, it would be interesting to find out why they did this as the main appeal of Yik Yak was the anonymity it provided. The username made people less likely to post in general, repeat posts would be noticeable and any comments or responses would be clearly attributed to a profile.

I wonder how much yikyaks popularity dipped after completely changing the app …

Judging by the fact I can see last weeks post about a million people leave per day

50,000 people used to live here, now it’s a ghost town.

When they changed it I literally died. I live in hell now.

I knew it was going down hill as soon as they added usernames even when it was optional to post with it

Yeah no one used the usernames anyway.

Anonymity was what yik Yak was about. Shame the devs thought otherwise:/

Ah well all hood things come to an end

Good*

However, this reversal did not result in the regeneration of the community in the longer term: in December 2016 Yik Yak laid off 60% of its staff (Soulas Citation2016) and the app closed in early May 2017.

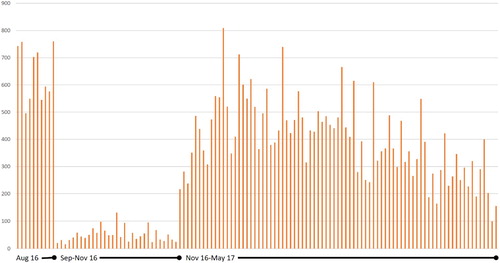

Figure 5. Volume of yaks posted at field site over the period of the study, showing significant drop over the period in which anonymity was being ‘designed out’ of the app. Usage picked up immediately on the reintroduction of anonymity before falling away again as the academic year drew to an end, and the imminent closure of Yik Yak was announced.

Conclusion: anonymity as a space apart

All our data – quantitative and topic analysis of yaks posted in our field site, content analysis of yak content, undergraduate researchers’ reflective reports and interviews – converges clearly on the finding that anonymity was a major source of value of the app to its users. Two of the characteristics of anonymity outlined by Bachmann, Knecht, and Wittel (Citation2017) in their special issue dedicated to the theme of the social value of anonymity are particularly relevant here: anonymity as freedom from surveillance, accountability and social constraints; and anonymity as a space apart from the ‘commodification of the social’ (244–245).

In her classic paper ‘The Meaning of Anonymity in an Information Age’, Helen Nissenbaum (Citation1999) argued that anonymity may encourage freedom of thought and expression by removing individuals from risk of ridicule, enable people to seek help particularly for ‘socially stigmatized problems’ such as sexual issues, suicidal thoughts or domestic violence, and provide space away from ‘commercial marketeers’ (142). These were all notable topics addressed in the yaks we gathered. Nissenbaum goes on to re-work the idea of anonymity in terms of the ability for individuals to be ‘unreachable’:

Being unreachable means that no one will come knocking on your door demanding explanations, apologies, answerability, punishment, or payment. Where society places high value on the types of expression and transaction that anonymity protects … , it must necessarily enable unreachability. (142)

If, as a society, we agree that what is importantly at stake in anonymity is the capacity to be unreachable in certain situations, then we must secure the means to achieve this. This will include a dramatic reversal of current trends in surveillance, as well as a relentless monitoring of the integrity of systems of opaque identifiers. Without at least these measures, even if we nominally secure a right to anonymity through norms and regulations, we will not have secured what is at stake in anonymity in a computerized world. (144)

If, as our research shows, unreachability holds significant social value for students, there is a need for higher education to learn to value it in broader terms than its use-value for peer review, anonymised assessment or teaching evaluation. There is a need to move away from the tendency to align anonymity within social media communities with deviance and secrecy, thinking in a more nuanced way about the social media ecologies of students and re-framing them in terms of what Haber (Citation2017) has called ‘the complex desire for diverse temporalities of interaction – different speeds of communication at varying levels of intimacy and exposure’ (no page). Schlesinger et al. (Citation2017) have helpfully described the social value of Yik Yak as lying in its bringing together of anonymity with ephemerality and hyper-locality, with the resulting ‘situated anonymity’ being key to its success and vibrancy as an online community.

To finish, we wish to focus on two ways in which universities might learn from the example of the failure of Yik Yak, and from the insight this failure gives us to the current state of anonymity, surveillance and community formation on university campuses. First, surveillance technologies which write out the possibility of anonymity, continue to be championed by corporate ‘ed-tech’ and its supporters in the education community. Adoption by universities of some of these has already become mainstream: plagiarism detection and lecture recording, for example. Others are still emergent: for example, facial and emotion recognition has already been posited as a means for measuring student attendance and engagement (D’Mello, Dieterle, and Duckworth Citation2017), sensor-based technologies are increasingly used for managing space and measuring movement around campus (Atif, Mathew, and Lakas Citation2015), and educational neurotechnologies are being developed aiming to scrape brain data from students in the interests of measuring and ‘enhancing’ student learning and engagement (Williamson Citation2018). The extent of this amplification of surveillant uses of individuals’ data has led human rights researchers to argue the need for new protections which go far beyond the protection of personal data: Ienca and Andorno (Citation2017) argue for the right to cognitive liberty, the right to mental privacy, the right to mental integrity and the right to psychological continuity. The solutionist promises of surveillance ed-tech need to be countered by programmes within universities which directly address and counter their likely long-term effects on trust, reciprocity and academic freedom on campus.

Second, to work against these potentially dystopic trajectories of surveillance technology, universities need to re-visit anonymity, and put into place principles and frameworks which respect its social value. As Bachmann, Knecht, and Wittel (Citation2017) have pointed out, the technical forces converging on the exclusion of anonymity have their base in some very muddy waters: in the politics of fear, in normative dreams of transparency, connectivity and justice-via-measurement, and in digital capitalism’s competition for more and more data (241). There is scope, as we move further into the data age, to normalise alternatives by recognising the value of the sensibilities of anonymity, ephemerality and unreachability.

Material examples of ephemeral community and anonymity as a ‘terrain of contestation’ (Rossiter and Zehle Citation2013) on campus are becoming alarmingly hard to find. Our research, which has interrogated the development, growth, decline and legacy of one such example, constitutes a valuable portrait by which we might better understand our current predicament in relation to anonymity, its perceived value and its growing impossibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Sian Bayne is Professor of Digital Education and Director of the Centre for Research in Digital Education at The University of Edinburgh. Her research is currently focused on higher education futures, interdisciplinary approaches to theorising and researching digital education and digital pedagogy.

Louise Connelly is based at The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh. Between 2012 and 2015 she was Head of Digital Education at the Institute for Academic Development, University of Edinburgh, and PI on a programme of research on student management of their digital footprint.

Claire Grover is Senior Research Fellow in the Language Technology Group in the School of Informatics at the University of Edinburgh. She is also part-time Turing Fellow at the Alan Turing Institute.

Nicola Osborne is Digital Education Manager and Project Manager at EDINA, a centre for digital expertise and online service delivery at the University of Edinburgh, leading on social media development across the university.

Richard Tobin is a researcher in the Language Technology Group at Edinburgh University with expertise in XML and its use in natural language processing.

Emily Beswick is a researcher at the Anne Rowling Clinic, and was an undergraduate research assistant on the Yik Yak project.

Lilinaz Rouhani is a MSc student in the School of Philsophy, Psychology and Language Science, and was an undergraduate research assistant on the Yik Yak project.

ORCID

Sian Bayne http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0133-7647

Louise Connelly http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6551-8148

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. https://www.noswearing.com/dictionary and https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~biglou/resources/bad-words.txt.

3. Available: https://www.facebook.com/yikyakapp/videos/1142915752424904/.

4. Convention on Yik Yak was to refer to specific users by naming the temporary avatar assigned to their post (in this case a picture of some socks).

References

- Atif, Y., S. Mathew, and A. Lakas. 2015. “Building a Smart Campus to Support Ubiquitous Learning.” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 6: 223. doi:10.1007/s12652-014-0226-y.

- Bachmann, G., M. Knecht, and A. Wittel. 2017. “The Social Productivity of Anonymity.” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 17 (2): 241–258. http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/social-productivity-anonymity.

- Bali, Maha. 2015. “A New Scholar’s Perspective on Open Peer Review.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (8): 857–863. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1085857.

- Ball, J. 2018. “Banning Anonymous Social Media Accounts Will Do More Harm Than Good.” Guardian, September 25. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/25/angela-rayner-social-media-online-abuse-labour-party.

- Bancroft, A., and P. Scott Reid. 2017. “Challenging the Techno-politics of Anonymity: The Case of Cryptomarket Users.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (4): 497–512. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1187643.

- Bell, M. 2001. “Online Role-play: Anonymity, Engagement and Risk.” Educational Media International 38 (4): 251–260. doi:10.1080/09523980110105141.

- Black, E., K. Mezzina, and L. Thompson. 2016. “Anonymous Social Media – Understanding the Content and Context of Yik Yak.” Computers in Human Behavior 57: 17–22. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.043.

- Byrne, C. 2017. “Anonymous Social Media and Qualitative Inquiry: Methodological Considerations and Implications for Using Yik Yak as a Qualitative Data Source.” Qualitative Inquiry 23 (10): 799–807. doi: 10.1177/1077800417731081

- Carson, Biz. 2016. “The App that College Kids Once Were Crazy for has Realized that Anonymity isn’t Everything.” Business Insider UK, August 17. http://uk.businessinsider.com/yik-yak-doesnt-care-for-anonymous-anymore-2016-8.

- Chester, A., and G. Gwynne. 1998. “Online Teaching: Encouraging Collaboration Through Anonymity.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 4 (2). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1998.tb00096.x.

- Christie, C., and E. Dill. 2016. “Evaluating Peers in Cyberspace: The Impact of Anonymity.” Computers in Human Behavior 55A: 292–299. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.024.

- Christopherson, K. 2007. “The Positive and Negative Implications of Anonymity in Internet Social Interactions: ‘On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog’.” Computers in Human Behavior 23 (6): 3038–3056. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2006.09.001.

- Constine, J. 2016. “Yik Yak’s CTO Drops Out as the Hyped Anonymous App Stagnates.” TechCrunch, April 7. https://techcrunch.com/2016/04/06/yik-yuck/.

- Correa, D., L. Araujo Silva, M. Mondal, F. Benevenuto, and K. P. Gummadi. 2015. “The Many Shades of Anonymity: Characterizing Anonymous Social Media Content.” Social Computing Research@MPI-SWS. https://socialnetworks.mpi-sws.org/papers/anonymity_shades.pdf.

- Cox, G. 2015. “Yik Yak’s Privacy Policy May Not Be What You Think.” University Press, September 9. https://www.upressonline.com/2015/09/yik-yaks-privacy-policy-may-not-be-what-you-think/.

- Dishon, G., and S. Ben-Porath. 2018. “Don’t @ Me: Rethinking Digital Civility Online and in School.” Learning, Media and Technology. doi:10.1080/17439884.2018.1498353.

- D’Mello, S., E. Dieterle, and A. Duckworth. 2017. “Advanced, Analytic, Automated (AAA) Measurement of Engagement During Learning.” Educational Psychologist 52 (2): 104–123. doi:10.1080/00461520.2017.1281747.

- Ellison, N., L. Blackwell, C. Lampe, and P. Trieu. 2016. “‘The Question Exists, but You Don’t Exist with It’: Strategic Anonymity in the Social Lives of Adolescents.” Social Media + Society 2 (4). doi:10.1177/2056305116670673.

- Fresco-Santalla, A., and T. Hernández-Pérez. 2014. “Current and Evolving Models of Peer Review.” The Serials Librarian: From the Printed Page to the Digital Age 67 (4): 373–398. doi:10.1080/0361526X.2014.985415.

- Gahagan, K., J. Mitchell Vaterlaus, and L. Frost. 2016. “College Student Cyberbullying on Social Networking Sites: Conceptualization, Prevalence, and Perceived Bystander Responsibility.” Computers in Human Behavior 55 (part B): 1097–1105. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.019.

- Haber, B. 2017. “For the Moment.” Real Life. http://reallifemag.com/for-the-moment/.

- Hargittai, E., and A. Marwick. 2016. “What Can I Really Do? Explaining the Privacy Paradox with Online Apathy.” International Journal of Communication 10: 3737–3757. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4655.

- Hess, A. 2015. “Don’t Ban Yik Yak.” Slate, October 28. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/users/2015/10/yik_yak_is_good_for_university_students.html.

- Hyslop-Margison, E., and R. Rochester. 2016. “Assessment or Surveillance? Panopticism and Higher Education.” Philosophical Inquiry in Education 24 (1). https://journals.sfu.ca/pie/index.php/pie/article/view/921.

- Ienca, M., and R. Andorno. 2017. “Towards New Human Rights in the Age of Neuroscience and Neurotechnology.” Life Sciences, Society and Policy 13 (5). doi:10.1186/s40504-017-0050-1.

- Kang, R., S. Brown, and S. Kiesler. 2013. “Why Do People Seek Anonymity on the Internet? Informing Policy and Design.” Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference 2013, April 27–May 2, Paris, France. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2470654.2481368.

- Kelly, Anthony. 2009. “In defence of anonymity: rejoining the criticism.” British Educational Research Journal 35 (3): 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920802044438.

- Koratana, A., M. Dredze, M. Chisolm, M. Johnson, and M. J. Paul. 2016. “Studying Anonymous Health Issues and Substance Use on College Campuses with Yik Yak.” AAAI Workshop on the World Wide Web and Public Health Intelligence. https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/studying-anonymous-health-issues-and-substance-use-on-college-cam.

- Li, L. 2017. “The Role of Anonymity in Peer Assessment.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (4): 645–656. doi:10.1080/02602938.2016.1174766.

- Li, Q., and I. Literat. 2017. “Misuse or Misdesign? Yik Yak on College Campuses and the Moral Dimensions of Technology Design.” First Monday 22 (7). doi:10.5210/fm.v22i7.6947.

- McAlone, N. 2016. “College Students Have Totally Lost Interest in Yik Yak — and It Could Kill the App.” Business Insider UK, September 22. http://uk.businessinsider.com/yik-yak-losing-popularity-in-colleges-2016-9.

- Moosa, D. 2013. “Challenges to Anonymity and Representation in Educational Qualitative Research in a Small Community: A Reflection on My Research Journey.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1080/03057925.2013.797733.

- Moskowitz, S. 2014. “Yik Hak: Smashing the Yak.” Silver Sky Labs. https://silverskylabs.github.io/yakhak/.

- Nissenbaum, H. 1999. “The Meaning of Anonymity in an Information Age.” The Information Society 15 (2): 141–144. doi:10.1080/019722499128592.

- Nissenbaum, H. 2004. “Privacy as Contextual Integrity.” Washington Law Review 79 (1): 119–158.

- Olson, P. 2015. “The Startling Rise Of YikYak in One Chart.” Forbes, February 12. https://www.forbes.com/sites/parmyolson/2015/02/12/yikyak-growth/#13bf536024b0.

- Raes, A., E. Vanderhoven, and T. Schellens. 2015. “Increasing Anonymity in Peer Assessment by Using Classroom Response Technology Within Face-to-face Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (1): 178–193. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.823930.

- Ross, J., and H. Macleod. 2018. “Surveillance, (dis)Trust and Teaching with Plagiarism Detection Technology.” In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Networked Learning 2018, edited by M. Bajić, N. B. Dohn, M. de Laat, P. Jandrić, and T. Ryberg. http://www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/abstracts/papers/ross_25.pdf.

- Rossiter, N., and S. Zehle. 2013. “Toward a Politics of Anonymity: Algorithmic Actors in the Constitution of Collective Agency.” In The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization, edited by Martin Parker, George Cheney, Valerie Fournier, and Chris Land, 151–161. New York: Routledge.

- Rost, K., L. Stahel, and B. Frey. 2016. “Digital Social Norm Enforcement: Online Firestorms in Social Media.” PLOS One. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155923.

- Russell, J. 2014. “Yik Yak’s New Funding Round Confirmed as Sequoia Leads $61M Investment.” TechCrunch, December 3, 2015. https://techcrunch.com/2014/12/02/yik-yaks-new-funding-round-confirmed-as-sequoia-leads-61m-investment/.

- Safronova, V. 2017. “The Rise and Fall of Yik Yak, the Anonymous Messaging App.” New York Times, May 27. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/27/style/yik-yak-bullying-mary-washington.html.

- Saveski, M., S. Chou, and D. Roy. 2016. “Tracking the Yak: An Empirical Study of Yik Yak.” ICWSM. https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/tracking-the-yak-an-empirical-study-of-yik-yak/.

- Schlesinger, A., E. Chandrasekharan, C. A. Masden, A. S. Bruckman, W. K. Edwards, and R. E. Grinter. 2017. “Situated Anonymity: Impacts of Anonymity, Ephemerality, and Hyper-locality on Social Media.” CHI ’17 Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, Colorado, USA, 6912–6924. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025682.

- Scott, S. V., and W. Orlikowski. 2014. “Entanglements in Practice: Performing Anonymity Through Social Media.” MIS Quarterly 38 (3): 873–893. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.3.11

- Selkie, E., K. Rajitha, Y. Chan, and M. Moreno. 2015. “Cyberbullying, Depression, and Problem Alcohol Use in Female College Students: A Multisite Study.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18 (2): 79–86. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0371.

- Seman, J. 2014. “A Letter on Yik Yak Harassment.” The Middlebury Campus, October 8. https://middleburycampus.com/27709/opinion/a-letter-on-yik-yak-harassment/.

- Shontell, A. 2015. “How 2 Georgia Fraternity Brothers Created Yik Yak, a Controversial App that Became a ∼$400 Million Business in 365 Days.” Business Insider UK, March 12. http://uk.businessinsider.com/the-inside-story-of-yik-yak-2015-3

- Soulas, T. 2016. “What We Can Learn from Yik Yak.” VentureBeat, December 12. https://venturebeat.com/2016/12/12/what-we-can-learn-from-yik-yak/.

- Srnicek, N. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- Stoler, E. 2015. Yik Yak - the rise of anonymous geo-social connectivity. JISC blog, May 20 2015. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/blog/yik-yak-the-rise-of-anonymous-geo-social-connectivity-20-may-2015

- Suler, J. 2004. “The Online Disinhibition Effect.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 7 (3): 321–326. doi:10.1089/1094931041291295.

- West, S. 2017. “Yik Yak and the Knowledge Community.” Communication Design Quarterly Review 4 (2b): 11–21. doi:10.1145/3068755.3068757.

- Williamson, B. 2018. “Brain Data: Scanning, Scraping and Sculpting the Plastic Learning Brain Through Neurotechnology.” Postdigital Science and Technology. doi:10.1007/s42438-018-0008-5.

- Wu, T-Y., and D. J. Atkin. 2018. “To Comment or Not to Comment: Examining the Influences of Anonymity and Social Support on One’s Willingness to Express in Online News Discussions.” New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444818776629.

- Xue, M., C. Ballard, K. Liu, C. Nemelka, Y. Wu, K. Ross, and H. Qian. 2016. “You Can Yak but You Can’t Hide: Localizing Anonymous Social Network Users.” IMC ‘16 Proceedings of the 2016 Internet Measurement Conference: 25–31. doi:10.1145/2987443.2987449.

- Zuboff, S. 2015. “Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization.” Journal of Information Technology 30: 75–89. doi:10.1057/jit.2015.5.